12

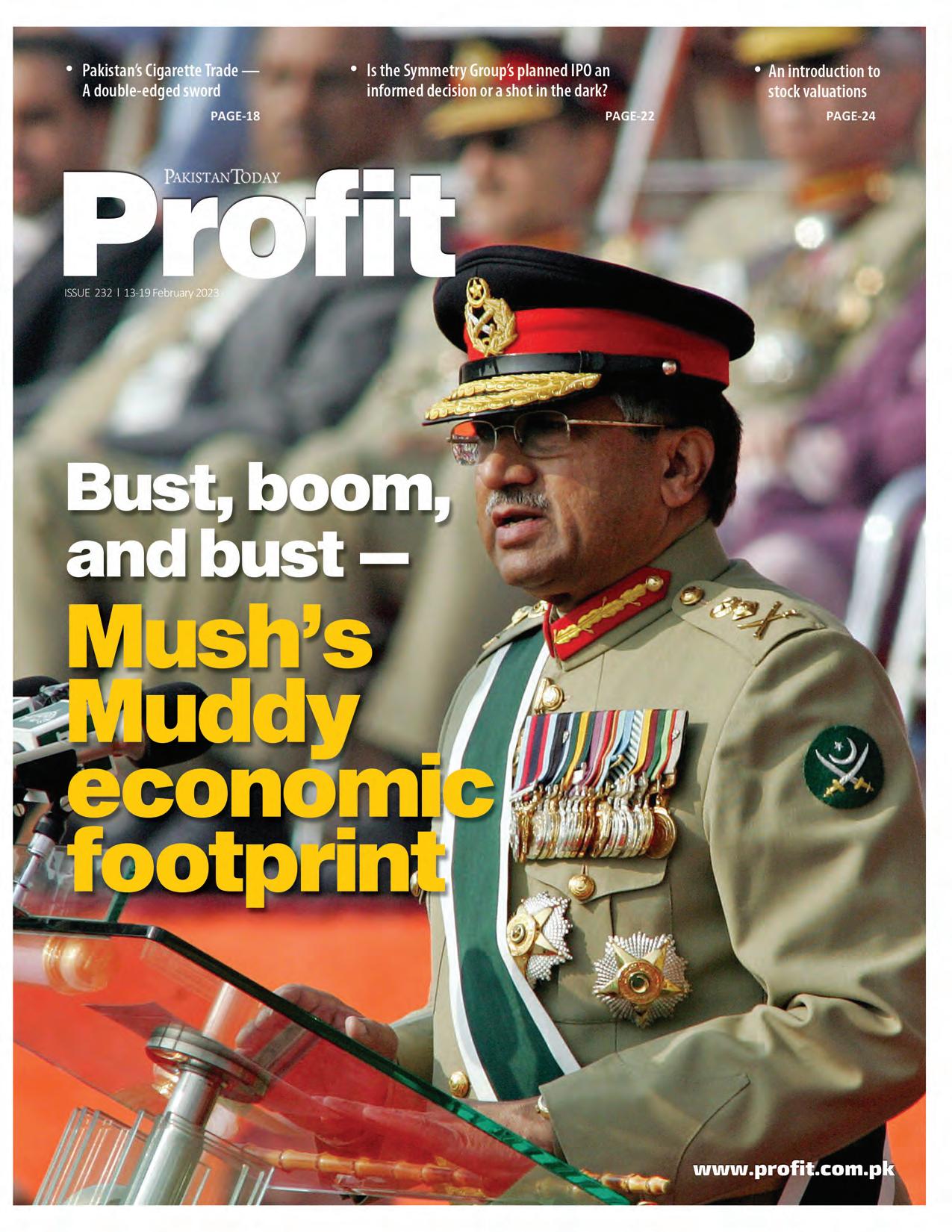

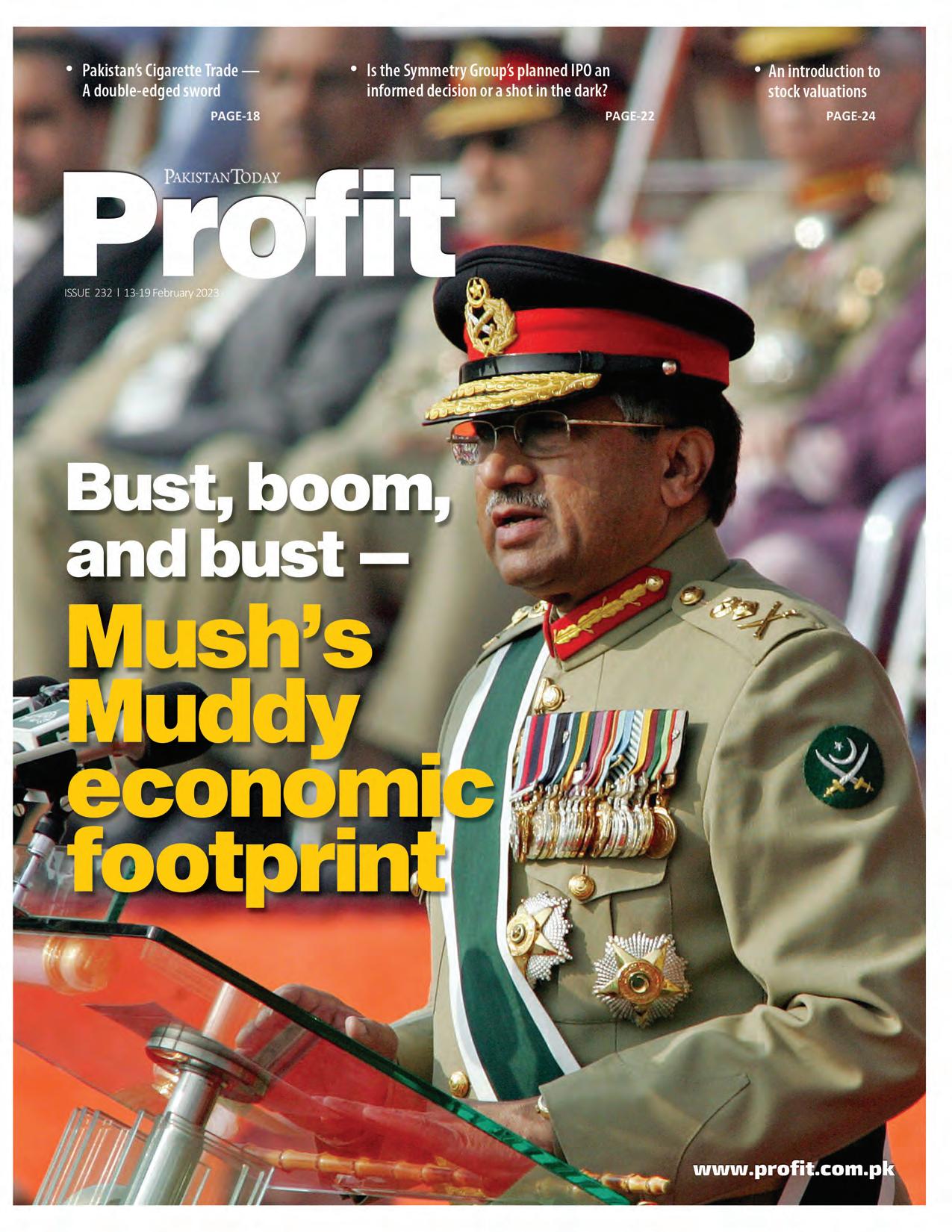

12 Bust, boom, and bust — Mush’s Muddy economic footprint

18

18 Pakistan’s Cigarette Trade — A double-edged sword

22 Is the Symmetry Group’s planned IPO an informed decision or a shot in the dark?

24

24 An introduction to stock valuations

27 Framing policies for a digital economy Ishrat Hussain

Publishing Editor: Babar Nizami - Joint Editor: Yousaf Nizami

Senior Editors: Abdullah Niazi I Sabina Qazi

Chief of Staff & Product Manager: Muhammad Faran Bukhari I Assistant Editor: Momina Ashraf

Editor Multimedia: Umar Aziz - Video Editors: Talha Farooqi I Fawad Shakeel

Reporters: Ariba Shahid I Taimoor Hassan l Shahab Omer l Ghulam Abbass l Ahmad Ahmadani l Muhammad Raafay Khan

Shehzad Paracha l Aziz Buneri | Daniyal Ahmad | Ahtasam Ahmad | Asad Kamran l Shahnawaz Ali l Noor Bakht l Nisma Riaz

Regional Heads of Marketing: Mudassir Alam (Khi) | Zufiqar Butt (Lhe) | Malik Israr (Isb)

Business, Economic & Financial news by 'Pakistan Today'

Contact: profit@pakistantoday.com.pk

We need to talk about denial, Pakistan. And we need to talk about it in the context of the death of former military ruler Pervez Musharraf, who was buried last week in Pakistan with full honours.

By now, you would have read and watched more than your fair share of opinions and coverage of the former military strongman’s life and times. Many said he was the worst; few said he was the best. This is not so much about that as it is about what happened once he had died.

Musharraf’s body was flown into Pakistan on Monday, February 6th, a day after he died in a Dubai hospital. He was buried on Tuesday in his hometown, Karachi. It was not televised, barely acknowledged by state television, and save a short press release from the military, not many acknowledged their presence at the event.

The truth, however, is that he was buried with full military protocol, and his funeral attended by top former and serving military leaders, civilian leaders, businessmen, and even some foreign dignitaries. This was the funeral of a man that we in Pakistan say was disgraced, disowned, and pushed out. He broke the Constitution - twicestrong-armed his critics and crushed dissent, sometimes brutally.

And therein lies the denial. The fact of the matter is there are more in Pakistan than we care to admit that actually saw Musharraf in a positive light, and, at the very least, saw in him a hope for change. Those views may be misplaced, but reality is seldom good or bad. It’s just reality. Perhaps one of the biggest talking points for those that see Musharraf in a positive light are the ones saying his era was one that saw great economic prosperity.

This is what our cover story this week focuses on. Our findings are quite definitive

— the late General (R) Pervez Musharraf ruled over Pakistan at one of the easiest times to be an economic manager and still managed to leave the country a mess at the end of his reign.

We have been told, endlessly, that Musharraf was a dictator who deserved nothing but disgrace and criticism. But, the reality is that he wasn’t disgraced – no matter how much we try to tell ourselves that. Even a court verdict that ordered a rather macabre death penalty for his extra constitutional acts was overturned without much fuss. And we never spoke about it again.

The reality of the matter is that Musharraf’s coup happened in a certain context that afforded him sympathy despite his clear transgressions. Consider that, in 1999, when Musharraf took over, Pakistan had just been through its ‘decade of democracy’ that saw four government changes in 11 years, with Nawaz Sharif and Benazir both getting two shots at premiership that were cut short by praetorian designs.

It was chaotic and unstable. In fact, 1993 saw five (yes, five) prime ministers, three presidents and two army chiefs. Despite what we are told, the reality is that his takeover wasn’t exactly met with widespread protests. The criticism of later years, taken as an established and unchallengeable truth now, was nowhere to be seen back then. In fact, if they’re honest, most of his critics will admit they were supporters at one point – for his liberal reforms, for his economic stability, through the opening of the media, or just the fact that they didn’t have to put up with political bickering and frequent upheaval. Musharraf represented, for better or worse, a chance of stability. And he gave that for a bit – mostly through unsustainable means and often through patently illegal and dictatorial measures. How many reactions have there been from industry leaders who

have been critical of Musharraf, only to be followed by a ‘but…’ That’s not because people can’t criticise him. That would be a lie. It’s because there is a level of sympathy for him.

He wasn’t an anomaly. Consider the reign of another military dictator, Ayub Khan. When he took over, there had been seven prime ministers in 11 years, each removed through petty political wrangling. He too is remembered in fond words despite his extra constitutional measures and dictatorial policies. And much of that fondness does also have to do with the perceived economic prosperity Ayub brought.

One of the famous stories about Ayub Khan is back from 1970. When Pakistan entered a war with India over East Pakistan, Ayub went to the military command and offered himself up for enlistment as a foot soldier. He was widely hailed for this. No mention was made of his time in power that he gained extra-constitutionally. With such acts of machismo and fawning looks back, the legacy of military dictators in this country has been regularly whitewashed.

If we don’t admit this, and choose to deny it – which we are – we do so at our own peril, and at a time that political wrangling is once again at a high. By elections, Punjab government changes, provincial dissolutions, provincial elections before general elections – all amidst a near-unprecedented economic crisis.

The bells are ringing. And we are standing with our fingers in our ears speaking about how he got what he deserved. He didn’t. Because all people want certainty, and will always have a soft spot for anyone who says they are trying to bring it – by any means necessary. That’s not good or bad. It ‘s just a reality that isn’t fashionable to admit. Denial is not just a river in Egypt. It’s a river in Pakistan, too.

In 1999, Pervez Musharraf commandeered control of a country that was in economic and political peril. By the time he was forced out of office in 2007, he was leaving the country at the beginning of another major crisis. In the years between, Pakistan saw an unprecedented boom and record levels of growth.

More than anything else, it is the dissonance between the prosperous middle years of the Musharraf era and the disastrous end that blurs the economic legacy of his administration. The reality is that between 2002-06 General Musharraf had the good fortune of being at the helm of a country that had found the favour of the United States and other western powers.

Pakistan’s role in the war on terror meant that the dollars were flowing freely and there was a rare opportunity to fix the structural ills that plagued our economy and build lasting institutions. With virtually no political opposition to his rule, this was a golden opportunity. And Musharraf fumbled it.

Off the back of an easy IMF programme, foreign aid to the tune of $10 billion, debt relief from the Paris Club, Pakistan’s economy grew and grew like never before. Musharraf’s time in power saw the establishment of some institutions and the implementation of certain policies that have been good for the economy in the long-run. The privatisation and liberalisation of the banking sector laid the foundation for financial inclusion in the country, the establishment of institutions like NADRA, and the development of the telecommunication sector and automobile industry are all hallmarks of this time.

Yet this growth was unsustainable. Rather than focus on any structural reforms, the Musharraf era oversaw Pakistan spending beyond its means and the economy growing chiefly through consumption. Imports continued to skyrocket, exports shrunk compared to the GDP, and by 2008 Pakistan was on the brink of a major economic collapse. At the same time, the energy policies of this era left Pakistan plagued with a serious load-shedding problem which eventually resulted in the decline of major industries such as textiles and agriculture. The legacy he leaves behind is of an overheated economy where hubris and short-sightedness meant the right decisions were not taken at the right time.

To understand better the shadow of the Musharraf years hanging over us today, Profit spoke to a number of people including former central bank governor Dr Ishrat Husain, journalist Khurram Husain, academic Dr Ali Hasnain, former commerce minister Humayun Akhtar Khan and others to try and understand

the legacy of 1999-2007.

Where do we begin to measure the economic footprint of the military strongman that claimed to be the harbinger of enlightened moderation and democracy in Pakistan? At the beginning.

The initial years (1999-2002)

Musharraf took over an ailing economy. After Pakistan’s successful nuclear tests the country had been blacklisted on the international stage and was stuck in a rut. Both the PPP and PML-N governments were seen as corrupt by foreign powers and by international NGOs such as Transparency International, which consistently ranked Pakistan among the top three most corrupt countries in the world during the 1990s.

Political instability following a military coup did not do any favours to the economy. When Husain took over, the economy was stagnant, external debt payment difficulties were pervasive, and financial indicators were concerning. Two thirds of the state’s revenues were going towards debt servicing. With exports worth $7 billion and debt servicing costs of around $5 billion, Pakistan was on the brink of default — much like it is today.

And in the first few years, the economy took time to pick up. Musharraf’s economic team consisted of a number of staunch bankers and development economists that believed strongly in industry and the free market. Husain was brought in from the World Bank to take over the SBP and Citi Banker Shaukat Aziz, who would eventually become prime minister, was Musharraf’s man in Q-block. At this point in Pakistan’s history, inflation was not really a major concern. However, this came at the cost of having low growth and high unemployment. The Musharraf administration’s policy was that the economy should be pumped with activity, and business should be promoted to stir it from its slumber. Because of this, a hardline approach was taken which involved a very loose monetary policy, and record low-interest rates.

In the initial years, things continued to be slow. But then came the boom post 9/11. Suddenly, Musharraf was a crucial ally to Bush’s war on terror in Afghanistan and Pakistan found itself on the receiving end of an avalanche of dollar inflows. “After the twin towers fell two things happened,” says Hasnain, a professor of economics at the Lahore University of Management Sciences

(LUMS). “There was an increase in inflows through the Paris Club and there was a massive increase in remittances, and secondly the US was starting to tighten its regulations.”

“Hundi markets that worked before to bring forex into the hands of individuals shrunk. Dollars started coming in through formal banking channels which meant that the money then comes into the SBP which then releases rupees to the market. Pakistan’s forex reserves went up by $4 billion in one year. Thinking about the size of the economy that would be around $12 billion in today’s money since the economy was much smaller back then.”

And between 2002 to 2007, Pakistan also started receiving a lot of dollar inflows. At this point, the government’s policies of low interest rates also kicked in. The plan was simple. If interest rates were low, more people would borrow and spend on investment and business, which would mean employment for more people and the economy growing. At the time these decisions were being taken, money supply was high, global growth led to high fuel prices, and crop failure was leading to high prices of items such as palm oil — more eerily similar situations to today.

As a result of the low-interest rate and borrowing conditions being easier, the number of borrowers in the country went up from 1.1 million people to 5.5 million. The goal at this point was very much to increase purchasing power. As a result, private sector borrowers took up the unused capacity in the economy galvanising different industries. The outcomes were better agriculture, better production, better outputs, and better exports. As a result, the growth rate climbed to 8%.

This was one of the biggest booms Pakistan’s economy had ever seen. Pakistan’s tax base and government revenue collection more than doubled from about Rs 500 billion to over Rs 1 trillion. Pakistan’s GDP more than doubled to $144 billion since 1999. The strong consumer demand in Pakistan drove large investments in real estate, construction, communications, automobile manufacturing, banking and various consumer goods. The Karachi stock market surged tenfold from 2001 to 2007. Pakistan positioned itself as one of the four fastest growing economies in the Asian region during 2000-07 with its growth averaging 7.0% per year for most of this period. Yet this entire period of growth was dotted by the problem that it was all consumption based and not growth based.

“After the initial slowness, the growth rate did get to 8%”, says Hasnain. “This was actually one of the highest growth rates in the world at that time and the economy was well on its way up. However this increase was not because of productivity it was because of con-

sumption, and that meant that the economy was fast overheating. What they were doing was financing consumption using monetary policy and allowing a large current account deficit. Inflation adjusted interest rates were negative.”

This was the painful reality of the boom from 2002-05. A significant share of the investment that financed growth spurts came from the influx of foreign capital that augmented the low level of domestic savings, most of it from the United States. External finance became available to compensate the country for the strategic help it provided America. Much like during the 1960s and then again during the 1980s, both eras of dictators (Ayub and Zia), Pakistan had done the same. The reward was much the same as Pakistan was recruited to join America’s war on terror and for its support was given an estimated $10 billion of assistance over the six-year period from 2001 to 2007. In other words, the country did little to generate high rates of economic growth by using its own resources. It also did not improve the quality of governance or ensure continuity in policymaking. These factors have been identified by economists as important contributors to growth.

The party naturally did not last. In around 2005, it was time for the chickens to come home to roost. “The monetary policy decisions of the SBP meant that inflation was knocking at the doors and was about to become the most talked about point in politics. The general consensus seemed to be that in 1999, the economy was in desperate need of a kickstart, however, it needed to be done so in a sustainable manner. Instead, we might have launched into a boomand-bust cycle”, says Khurram Husain, an economic journalist that closely followed the Musharraf era.

Over the same period, poverty levels increased again. There was some decline in the

poverty rates from 1999-2005, but the unprecedented rise in food prices since 2004, along with the shortage of wheat flour and a slowing economy, eliminated any gains that had been made. Also, there was evidence that labour absorption was limited despite rapid economic growth in the 2002-07 timeframe. Structural problems constraining long-term growth came dramatically to the forefront in the first half of 2008 with major power shortages and large scale load shedding. In addition, the erosion of the competitiveness of the country’s dominant exports, textiles, and clothing, and a sharp slow down in export growth since 2006-07 led to a large increase in the trade imbalance and limited the prospects for growth in labour- intensive manufacturing.

Back then, economists such as the World Bank’s policy manager for South Asia, Ijaz Nabi, said that SBP may have overshot its mark. “It is very important to be very vigilant when you have that kind of expansion. It is very easy to go over the point where you’re just supplying enough credit given the supply of goods. It is very difficult to overshoot and we overshot. That is when inflationary pressures build up.”

“It was a policy choice. Low inflation with low growth and high unemployment is of no use to me,” he said in an interview back in 2007 after his term had ended and the inflation rate had continued to hike. “If they had wanted a different method to solve the problems of the economy we had back then, they should have chosen someone other than a development economist,” claims Hussain, who was the governor of the State Bank during the Musharraf era.

The only problem was that the inflationary pressure did build up, and the SBP overshot its mark. “What should have happened at this time was that the government should have taken action to stop the overheating. But the budget that year was expansionary. The impact was that the SBP as usual failed to stop the economy from overheating,”explains Hasnain. “After this your vulnerabilities increased and

there was an oil shock. The current account deficit increased and ultimately we went into the 2008 crisis.”

And that is the reality of how macroeconomic management took place during the Musharraf era. After a period of strong economic expansion, relative macroeconomic stability, and increased foreign investor confidence during the years 2003-06, Pakistan was once again at a critical juncture in 2008. Pakistan attracted over $5 billion in foreign direct investment in the 2006-07 fiscal year, 10 times the figure of 2000-01. The government’s debt fell from 68% of GDP in 2003-04 to less than 55% in 2006-07, and its foreign-exchange reserves reached $16.4 billion.

However, because the economy was overheating inflationary pressure managed to lay waste to the gains of the preceding years. Macroeconomic indicators deteriorated very sharply, inflation touched record levels in the first nine months of 2008 following three previous years of high single-digit increases in the level of prices. This is despite the fact that the sharp increases in international oil prices during most of 2008 were not fully passed on to consumers and the price of wheat for urban consumers was subsidised. The burden of high prices, especially of basic food items, became intolerable for poor households. One of the primary causes of inflation since 2004 may have been monetary in character, but in 2008 they acquired a structural nature, given the high dependence on imported energy.

“The way to judge this era is simple. By the time he left power the economy was in crisis. Very few structural issues were addressed and the growth was coming through aid based consumption” says Hasnain. “How do you judge the economic legacy of Pervez Musharraf? Just look at what he did”, says Khurram Husain. “There was a crisis when he took over and a worse crisis by the time he left. The years in between there was a boom but the final result was pretty bad. Make of that what you will.”

The monetary policy decisions of the SBP meant that inflation was knocking at the doors and was about to become the most talked about point in politics. The general consensus seemed to be that in 1999, the economy was in desperate need of a kickstart, however, it needed to be done so in a sustainable manner. Instead, we might have launched into a boom-and-bust cycle

Khurram Husain, economic journalist

This has been the story of how the economy played out from 1999-2008. Very briefly put, Pakistan prospered after 9/11 due to an influx of money and a supportive geo-political situation, but the Musharraf administration failed to implement any structural reforms or make necessary decisions to halt the economy from overheating. As a result, by the time the next government came in, inflation was rife and an energy crisis was brewing. Despite this, there were attempts in this era to increase the tax base, to promote business, and end the energy crisis. But most of these policies were disastrous.

Perhaps one that haunts us to this day is that Musharraf continued to try and artificially maintain the rate of the rupee at Rs 60 against the dollar.

“Musharraf practised Daronomics before Dar, holding the dollar at 60. Just as with 2013-18 Dar, this would have disastrous effects on our trade. Exports (% of GDP) were never below 16.1% in 8 years preceding Musharraf’s takeover. They would never return to those levels,” says Hasnain. “Folks who defend his era point to the rapid growth in inflows after 9/11. It is for Macroeconomists to judge whether these inflows were dealt with properly, but what do the numbers show? It is worth thinking of the Musharraf era in two phases: 1999 to 2003, and 2004 to 2008.”

“Reserves, measured in months of import

cover, went from critical levels to a reasonably healthy eight months by 2003, before collapsing again before his exit. The Current Account famously showed a surplus for three years, before crashing to levels worse than what he had inherited. And FDI blipped similarly briefly. This was consumption-led growth, and for a few years, imports were cheap and urban Pakistan partied. Musharraf managed to make ����’s debt substantially more manageable (as a % of GDP), but without improving the rate at which debt accrued (fiscal deficits remained steady).”

This, perhaps, was one of the bigger changes of the Musharraf era that may have been for the greater good. Banks had been nationalised and re-

HBL was the major denationalisation project that took place in the Musharaff era, otherwise these were policies that we had introduced before. India had also begun the deregulation process in the 90s but the difference was that they stuck with it and we haven’t managed to do the same

Humayun Akhtar Khan, former commerce minister

organised in the 1970s into five major banking organisations. In December 1999 public sector banks had more than 80% of the market share and almost all of them were on budgetary support. On top of that, their operations were hindered by bureaucratic inefficiencies since they were government owned.

“By the mid 1990s the banking sector was on its knees. The World Bank and IMF were both saying massive reforms were needed but the government was not catching on. When Dr Ishrat came in, many of the large national banks were insolvent. He took a fresh look at the entire picture and took a proactive approach in the reforms of the banking sector. He took up a full comprehensive review and addressed the issue really well,” says Zakir Mehmood, former CEO and President of Habib Bank Limited.

In Musharraf’s administration, Husain became the leading lightbearer for the denationalisation of the banking sector, after which the private sector got a great boost. But this too was one reform that had already been underway and was just helped along by Musharraf’s regime. “Denationalisation and deregulation were started back in the 1990s for the first time under Nawaz Sharif and Sartaj Aziz in his first stint as finance minister in 1993.

HBL was the major denationalisation project that took place in the Musharaff era, otherwise these were policies that we had introduced before. India had also begun the deregulation process in the 90s but the difference was that they stuck with it and we haven’t managed to do the same,” says Khan, the former commerce minister, in a conversation with Profit.

“The initiatives soon came to fruition. Public sector banks were restructured, privatised, and built into competitive institutions, which provided quality services. Lending rates came down to 3-4% from 16-17% which led to a boost in private credit. Non-performing loans were reduced from 26% to 11% and the financial sector became a major contributor to the revival of the economy,” he adds.

This is also one of those elements on which Musharraf has a mixed legacy. On the one hand, Musharraf’s era sowed the seeds for some of the worst crises Pakistan is still dealing with to this day. Take for example, real estate. There was an explosion of housing societies in this era. Bahria Town was launched in this era as well. You see, taxes were not raised on property during this time because of which a lot of money started flowing into real estate. As a result, investment was drawn away from other

avenues and money was parked in real estate. The resultant over-expansion of the sector has nearly crippled the country. On the telcos front, there were some serious strides made. Take for example the policy introduced where the person calling was the one who would be billed. Today, calls and messaging in Pakistan are next to free.

However, on other fronts things were significantly worse. In the 1980s, the government began setting up oil-fired power plants, but the vast majority of Pakistan’s electricity came from water until at least the early 1990s. At that point, with international financing difficult to procure owing to Pakistan’s poor relations with the United States, the government instituted a policy that allowed for more private sector players to set up independent power plants (IPPs) that were reliant mainly on oil. Over the next decade, this increased Pakistan’s reliance on imported oil as a fuel for its electricity generation.

In the early 2000s, the Musharraf Administration decided to convert at least some of that thermal power generation capacity from imported oil to domestic natural gas, under the assumption that Pakistan had abundant domestic reserves. (This, as has been pointed out in this publication on many previous occasions, was a very faulty assumption.)

As of 2005, the height of the Musharrafera economic boom, Pakistan derived more than 84% of its electricity generation from entirely domestic fuel sources, according to Profit’s analysis of data from the National Electric Power Regulatory Authority (NEPRA).

That meant that even as the Iraq War of 2003 drove up global oil prices, Pakistani consumers of electricity remained largely unaffected. Unfortunately, there was a limit to just how much natural gas was available in Pakistan and around the end of the Musharraf years, Pakistan went from being a gas-surplus country to having a shortage. That shortage, in turn, meant that the thermal power plants that could run on either natural gas or furnace oil ended up having to run on oil almost all of the time as the government scrambled – and failed – to keep the lights on.

The sharp rise in reliance on oil coincid-

at the Lahore University of Management Sciencesed with a dramatic rise in oil prices themselves (late 2007 and again in early 2009). Oh, and the rupee’s value collapsed at the same time, which created a perfect storm for the incoming Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) led government, which tried to keep consumers insulated by increasing government subsidies, but the government did not have the money to do so.

The whole energy industry entered a massive financial crunch as the government’s failure to pay subsidies meant that power companies could not pay the oil importing companies which in turn could not pay their international suppliers, which meant that the country frequently ran out of enough oil to keep the power plants running. The PPP-led government was utterly inept at trying to resolve the problem that resulted in 12-hour daily power outages even in major cities, and longer in rural areas.

This is what it all comes down to. In his near decade in power, the late General oversaw, perhaps, what was the easiest time for economic governance in Pakistan. In some senses, his administration made valuable contributions to the economy. But these were the anomalies. Largely, it was an era of excessive money and short-term thinking. Most economists agree on this. The state he left the country in was one of excessive inflation, political turmoil, and wasted opportunities.

In the middle of this, of course, there were a few years (2002-05) where the economy saw major growth. Off the back of this, urban Pakistan thrived. That is where the romanticised memories of those days come from. In the long-term, Musharraf practised Darnomics before Dar did from 2013-18. The results are clear as day for all to see. In addition to this, as a military dictator with no political opposition, the Musharraf administration has no excuse for how they left the economy in a shambles at the end of their time. That is what the legacy of Pervez Musharraf is in Pakistan’s economic history, questions of democracy and constitutional abrogation not considered. n

“After the twin towers fell two things happened. There was an increase in inflows through the Paris Club and there was a massive increase in remittances, and secondly the US was starting to tighten its regulations”

Dr Ali Hasnain, professor of economics

(LUMS)

Pakistan exports plummet from $14.38m to $12.06m worth of cigarette to the Middle East in FY 21-22

By Nisma RiazIt is no secret that Pakistan is a major exporter of tobacco (raw materials), with its export portfolio having over 43 countries and generating around $65 million. However, in the last fiscal year, the country’s newly diversified tobacco exports, with finished tobacco products (cigarettes), enabled Pakistan to generate over $12 million from exports to Middle Eastern countries. What does that say about/mean for the tobacco industry of Pakistan?

Tobacco trade from the subcontinent can be traced back to the Imperial Tobacco Company of British India, which became operational in South

Asia in 1905. This trade was taken over by Pakistan Tobacco Company (PTC), as a subsidiary of the British American Tobacco (BAT), in 1947, right after Pakistan’s independence. Now the tobacco industry comprises two multinational cigarette manufacturers, namely Pakistan Tobacco Company Limited (PAKL) and Philip Morris Pakistan Ltd (PMPK), that control nearly 60% of the country’s tobacco consumption market share, while the rest is split between more than 50 smaller local companies. It can be safely asserted that Pakistan has been a prominent exporter, as well as consumer of tobacco since the country came into existence. However, the growth of tobacco in the region has a different story entirely.

The importance of the tobacco industry is reflected in the fact that from no tobacco production at all in 1947, Pakistan accelerated to becoming a self-sustinent producer of tobacco by 1968. How did we get here? Long story short, efforts to grow tobacco began in 1948, with an experimental 20 acre farm, which soon

uncovered Pakistan’s high potential for growing tobacco, especially Khyber Pakhtunkhwa’s (KP) ideal land and climate. Fast forward to 1968, Pakistan was no longer a net-importer of tobacco.

Yet the quality of tobacco being grown was not satisfactory enough for production by major companies, therefore was mostly utilised by much smaller local cigarette companies. To mitigate this issue the Pakistani government was urged to take serious steps in 1968, to support, improve, and develop the country’s tobacco industry. This is how the Pakistan Tobacco Board (Ali et al. 2015) came into existence. The formation of the Pakistan Tobacco Board (PTB) was the first step towards promoting and developing tobacco production and export. Since the establishment of the PTB, the board has been protecting the rights of tobacco growers, buyers, manufacturers of tobacco products, and traders engaged in tobacco processing. This accelerated the industry’s growth exponentially. So much so that tobacco is now

grown in all four provinces of Pakistan, with KP being the most prominent one.

With more than 80% of KP’s population living in rural areas and agriculture accounting for over 30% of its provincial GDP, the tobacco industry remains a major catalyst for economic growth for the province. It is a major part of the local agrarian economy of KP, whereby its provincial economy is pegged majorly to the growth of tobacco. Of over 50,800 hectares of tobacco crops grown across the country, KP alone houses nearly 30,000 of these hectares.

Unlike other agricultural products of Pakistan, tobacco production has surprisingly been uncharacteristically well-performing. Pakistani land that is dedicated to growing tobacco exceeds over 50,000 hectares, with a yield per hectare of nearly 2.3 tonnes, adding up to a total production of 113.6 million kilograms of tobacco. The yield per hectare of 2.3 tonnes per hectare beats the world average production for tobacco, which is a mere 1.84 tonnes per hectare. Meanwhile in 2021, KP produced 71.38 million kilograms on 28,089 hectares of land, reaching an average yield of 2.5 tonnes per hectare — a 66% rise on the global average. But how did we get here?

This performance can be attributed to the unignorable attention that tobacco has received in Pakistan. The Pakistan Tobacco Board (PTB) not only promotes the interests of tobacco production, but also acts as a research arm. Adding to that, the existence of multinational players in the market translates into distinguished infrastructural and institutional support to tobacco production, something that other crops greatly lack. This directly counters one of the largest problems of agriculture in Pakistan— poor research, which consequently results in substandard quality of produce, dated farming techniques, and non-resistant seeds. The tobacco crop, on the other hand, does not only have serious backing, but an entire lobby that became the catalyst for Pakistan’s admirable agricultural production of tobacco. Owing to these factors, now Pakistan is one of the largest tobacco producers in the world, with some of the highest per-hectare yield.

The abundant production of tobacco in Pakistan indicates that Pakistani tobacco has great potential to be a major exportable crop. Moreover, the rapidly growing demand for tobacco from South Asia over the past few years has added to this potential. The million dollar question now is whether this potential is rightly exploited?

Despite Pakistan having some of the highest yield and being one of the overall largest producers of tobacco, it is way below on the list of countries that have the most area under cultivation for tobacco. Research conducted by the Abdul Wali Khan University in Mardan shows that the area under tobacco cultivation in Pakistan was 43,134 hectares in 1980–1981, increasing to 50,800 hectares by 2019–2020. This indicates that the area under tobacco cultivation expanded over time due to its profitable nature. The same study highlighted that tobacco production in KP increased from 43,408 tonnes in 1980–1981 to 71,410 tonnes in 2019–2020, while the area under cultivation only rose by around 4,000 hectares during the same time. Whereas, the area under

cultivation grew by around 16%, the total production rose by a comparative 65%. These figures indicate that during this time much efforts were expended to improve production techniques in the province, resulting in the significantly higher yields.

Why then has the area under yield not increased? Well, a major reason is that existing farms have been favoured by tobacco companies, thereby profiting from this relationship. The area under yield remains stagnant because the farm-profitability of tobacco is not as high as it should be, considering the yield numbers. The reason for this is that farmers do not process the leaves into the substance that is rolled into cigarettes directly or favour much from the overall profitability of tobacco. In fact, tobacco companies buy green leaves from the farmers and then process them into smokeable tobacco, an important value addition that attracts most profits. These tobacco leaves are purchased at absurdly low rates, even though tobacco farming requires a lot of expensive inputs, such as fertilisers, labour, mechanical power, pesticides etc., which discourages existing exploited farms from expanding and new farmers from planting the crop.

So, despite the great potential of the tobacco industry, tobacco production itself is not very lucrative at the farm level. Increasing the price of green tobacco leaves would significantly increase the demand for farm inputs, such as fertilisers, labour, mechanical power, pesticides, and farmyard manure as well. The increasing input prices will in turn have adverse consequences for tobacco production. Moreover, there has been a constant demand among tobacco farmers in KP to give tobacco ‘crop status’ which would protect it in many ways, as well as giving it a greater share of cess from the federal capital.

Such unfavourable economic conditions, coupled with multinational companies

monopolising the industry not only hinder the true potential of tobacco production, but also exploit local farmers and tobacco companies. Despite these conditions, Pakistan has continued to be a major exporter of tobacco.

Despite being one of the major global suppliers of tobacco, Pakistan has not always been a big player in the global cigarette trade. According to international sources, such as the Atlas of Harvard Economic Complexity, Pakistan exported cigarettes worth just $2000 to the US in 1997. Fast forward a decade, Pakistan exported $793,000 worth of cigarettes to 10 countries, with Saudi Arabia being the biggest importer, taking 40.7% of Pakistan’s total cigarette exports in calendar year 2017. Even though the number of countries importing cigarettes from Pakistan dipped from ten to six in calendar year 2019, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Thailand, UAE, UK and Libya collectively imported $3.66 million worth of cigarettes from Pakistan. This forward looking trend in cigarette imports continued in calendar year 2020, whereby Pakistan generated $31.1 million, marking an 88.2% rise in revenues from cigarette imports in just one year.

As we have established, Pakistan started exporting finished tobacco products, in the form of cigarettes, fairly recently. Local regulatory bodies have also been recording the developments in Pakistan’s cigarette exports. According to the statistics reported by the Pakistan Tobacco Board (PTB), the export of cigarettes, or at least notable export of cigarettes, started in the financial year 2019-20, with $7.89 million worth of sticks.

During the past 11 months, Pakistan collectively exported 22.39 million kilograms of tobacco worth over $65.2 million. The total export of tobacco and its products were $77.3 million in 2021-22. This marks the legible share of Pakistan in the global trade of tobacco, which is worth over $80 billion.

According to sources, from the total tobacco produced in the country, Pakistan has been exporting at least 30% of it in the form of raw material and finished tobacco products. The rest of the commodity is consumed in making cigarettes and other products for the domestic market.

Apart from the cigarette exports to the Middle East, Pakistan’s major tobacco export destinations included South Korea, Malaysia, Switzerland, Indonesia, Netherlands, UAE,

Paraguay, Saudi Arabia, Germany, Kazakhstan, Myanmar, UK, Kuwait, Poland, Australia, USA, Singapore, Canada, Ukraine, Philippines, Bangladesh, Belgium, Afghanistan, Italy, Russia, Yemen and Bulgaria.

The export of finished tobacco products is a positive development for raw tobacco exporting countries, such as Pakistan. However, the export of cigarettes could not be accelerated as per expectations.

In the last fiscal year 2021-22, the country registered $12.1 million from cigarette exports to Middle Eastern countries. Even though Pakistan continued to export cigarettes to specific countries, the revenues generated from cigarette exports to the Gulf in the last fiscal year observed a dip of over $2 million, compared to the $14.38 million registered during FY 2020-21.

Gulf countries had earlier placed import orders of cigarettes worth $50 million in Pakistan. Currently, Pakistan exports cigarettes to Qatar, Saudi Arabia, UAE and Bahrain. Whereas the raw material for cigarettes is being exported to over 43 countries across the world, including the ones mentioned in the previous section.

Saudi Arabia has been a major destination of Pakistani cigarettes, with 800.76 million sticks worth $5.1 million. On the other hand, Bahrain imported 604.6 million sticks worth $ 4.5 million, Qatar imported 212.9 million sticks worth $ 1.4 million, and UAE imported 119 million sticks of cigarettes worth $ 0.92 during the FY 2021-22.

According to sources, the revenue of $7.89 million during July-June FY20 was the country’s first-ever major earning from the

export of value-added tobacco products to the Middle East.

Although Pakistan exports tobacco to various countries, this was the first time that the country exported finished products in such large quantities. Experts believe that this was a step in the right direction and can potentially help the country capture more markets, as well as earn better returns in the future.

It is pertinent to mention that in 2020 Pakistan Tobacco Company (PTC) received an import order of cigarettes from Gulf countries, notably from Saudi Arabia.

What potentially seemed like a major development in Pakistan’s tobacco exports took a bleak turn last year, with a $2 million dip in revenues compared to the previous year. What could have caused it?

“The importing country, after placing the order, had changed its standards for cigarettes, which ultimately caused a delay in the export of the product from Pakistan,” a PTB official told Profit. They added that PTC had later started exporting cigarettes after meeting the new standards of the Arab country.

According to the official, “Many cigarette manufacturing plants in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa were established in 1960s’ and 70s’, following which the importers had asked us to upgrade the quality of tobacco, paper, filters, packaging etc. These requirements had met successfully, paving the way to export of cigarettes to Middle Eastern countries in large volume and number.”

Regardless of last year’s setbacks, Pakistan remains a major exporter of tobacco, and now its value added products, across the world. n

Tell us about your journey in Pakistan, from your first job to ending up at foodpanda, what have these years of extensive experience taught you?

Muntaqa Peracha: After graduating in Computer Science from Georgia Tech in 2004, I began my professional journey with Digital Insight (later acquired by Intuit) in Atlanta. Coincidentally, there was a massive tech and telco boom in Pakistan during this time and with my previous experience with Verizon Wireless in the US, I decided it was the right time to come back and work locally serving the telecom and technology industry. Since then, I’ve worked for DWP Technologies, IBM, Inbox Business Technologies, Dun & Bradstreet and TPL Corp. Finally, I ended up at foodpanda as the Commercial Director - which really helped me gear up for my current role as the CEO of foodpanda, Pakistan. All of these experiences have taught me innumerable lessons, both in my professional and personal life. But, the most important learning of all has been that change is the only constant, and learning never really stops. After years of resilience, patience and proactively pursuing my goals, I find myself looking ahead with great promise.

Over the years, we’ve seen foodpanda transform itself from a restaurant delivery app to a one-stop-shop platform in Pakistan, from food to grocery, medicines, cosmetics to expanding its verticals. How did this transformation happen?

MP: Since its inception, foodpanda has remained focused on filling a massive gap by offering consumers a convenience based platform to order food from the comfort of their homes. However, it was covid-19 pandemic that paved the way for foodpanda to turn the global calamity into an unprecedented opportunity for individuals from all walks of life. Diversifying its business, but at the same time offering customers the convenience and choice they so deserved. Among our many initiatives, we launched services like pandamart to deliver essential items and groceries, homechefs initiative was started to support entrepreneurship in difficult times, we launched pandago to help last mile delivery logistics in the country and the list goes on.

For young organisations operating in a competitive sector, what impact does marketing have? Please share

your experience.

MP: Today’s young business leaders must invest time and effort in understanding their customers really well - if you have the fundamentals right and cater to the right segment the product or service will sell itself. Today’s consumers have become highly sophisticated and wary of polished promotional campaigns. Instead of starting with the product and then trying to sell it, businesses should begin with the audience at the centre of design strategy. Irrespective of the group of people it’s meant to reach, good marketing has to inspire meaningful change.

If you look at the situation globally, there’s a lot of uncertainty due to the global recession, several tech giants have been laying off thousands of employees all around the world. Would you call this the end of the big-tech era? What plans does foodpanda have in case a situation like this emerges?

MP: Layoffs in companies like Meta, Twitter and Shopify etc. were inevitable, and the trend had local reverberations for some portion of Pakistan’s labour force as well. While no business is fully immune to continued macro and political uncertainty, foodpanda’s parent company Delivery Hero (publicly listed company in Germany) has strong underlying financials, is well funded and committed to Pakistan as a growth market. We are the largest market in terms of population for Delivery Hero, and they are deeply invested in growing here; the kind of opportunity and potential that Pakistan’s young population offers is fundamental for foreign investors, going forward. These factors, holistically, have enabled us to operate with an enduring sense of security, even in difficult times and we are hopeful that once the macroeconomic situation improves, we will be well positioned to target numerous growth opportunities the country has to offer.

What role do you think gig work has played in improving people’s livelihoods, especially in recent years?

MP: Gig work has seen a massive boost around the world and in Pakistan in recent years, and for a very good reason. People are increasingly quitting permanent positions to take up gig work, as it transforms their livelihoods because of its flexibility, convenience and transparency. Currently, it feeds almost two percent of Pakistan’s labour force and the model is the backbone of our delivery services, to provide economic opportunity to independent contrac-

tors (also known as gig workers). We are proud of the opportunity and flexibility we offer to our riders, whom we refer to as ‘Heroes’, along with the many benefits we continue to offer including health coverage, accidental insurance, access to assets etc.

With our country’s massive unemployment rate of 6.2% and a 64% under-30 population, the gig economy offers the perfect solution.

Where do you see foodpanda in the next 5-10 years?

MP: If you had asked me this question three years ago, I certainly would never have predicted a global pandemic boosting our business to unparalleled success, or that foodpanda would empower homechefs to fulfil their dreams of owning multiple restaurants. I couldn’t have foreseen any of the challenges that we had to transform into opportunities, not just for ourselves, but for hardworking, everyday Pakistanis as well.

In the next five years, I envision foodpanda as the ultimate, one-stop-shop for all things food, grocery and affiliated services. As we invest in more ways to empower individuals and lead the overall restaurant industry’s transformation, we are also significantly increasing the selection of services available to customers. This includes building new technology to help small and medium businesses reach greater heights than ever with foodpanda, and applying a data-driven approach to last mile delivery.

Our goal is not to hit the 100-city mark, but to ensure that there is no compromise on management and efficiency of our operations in the existing 35 plus cities - plus with dedicated focus on customer experience. We are also very focused on sustainability, working on the right product for the right city, and the right product for the right neighbourhood. Our goal is to improve operations from bottom up; to go down into the trenches and develop holistic solutions. n

This content has been published in partnership with foodpanda

Pakistan’s Symmetry Group Limited (SGL), a technology oriented company which provides digital transformation, digital marketing and advertising services, is planning to complete its initial public offering (IPO) by the mid of March this year, targeting a raise of Rs 430 million.

According to the company, it plans to list on the main board of the PSX, with the total issue size of up to 72.2 million shares, about 31% of the post-IPO paid up capital, priced at Rs 5.50 per share.

The company has been on an impressive growth trajectory, with its profit after tax posting 112% growth in 2020, 60% in 2021 and 24% growth in 2022, and the company’s net margins have been clocking in at 20% or more for the last two years. Revenue on the other hand grew from Rs232 million in 2020 to Rs286million in 2021 and Rs341.5 million in 2022.

After the new raise, Symmetry aims to continue to take the trajectory of growth. The situation, however, might not look conducive to a listing on the stock market, since the overall macroeconomic doom and a surge in global inflation has hit tech valuations locally and globally. As a result, the listed tech companies on the Pakistan Stock Exchange (PSX) are also witnessing a downward spiral of their stock value.

But because it is going to be listed in the tech category of the exchange, the company has the opportunity to hit the bullseye on getting the desired valuation. Because despite the drop in stocks, tech companies are still getting beefed up multiples. This presents itself as an opportunity as well as a risk. Because for long, Symmetry has been identified as a digital marketing firm and not a tech firm, like Systems or Netsol. Would the market be willing to give

them the valuation befitting of a tech company? And how have they hedged themselves?

In 2003, Symmetry Group Limited was founded with an initial investment of Rs150,000 as a digital marketing company, roping in Telenor as its first client and the ran the campaign of Telenor’s famous mobile phone plan DJuice.

on marketing tech and digitalization of marketing, sales and other consumer facing functions of organizations. In 2009, Sarocsh Ahmed and Adil Ahmed formed a new company, Symmetry Digital Pvt Ltd, which acquired Symmetry Group at a cost of Rs42.7 million. In 2010, in order to increase the market share, the board of Symmetry Digital decided to form a new company as a wholly owned subsidiary of Symmetry Digital. This new company was called Creative Jin Pvt Ltd. In 2012, the Symmetry Digital Private Limited, decided to establish the second wholly owned subsidiary under the name of Iris Digital Pvt Limited. At the same time, another entity under the name of Symmetry Group Pvt Limited was also incorporated which then became the holding company of Creative Jin, Iris Digital and Symmetry Digital. In 2017, Symmetry Group Limited was converted into a public unlisted company. In 2021, Symmetry Group Limited decided to close Creative Jin and transfer its business into Symmetry Group. Today, there are three operating companies within the group; Symmetry Group Limited as the parent company, Symmetry Digital which is a majority owned subsidiary of the company, and Iris Digital the second majority owned subsidiary of Symmetry Group.

From a digital marketing company in 2003, Symmetry Group now says it has now

moved on to become a company that is focused on marketing technology and digitalisation of marketing, sales and other consumer facing functions. Its clients now include the biggest telco in Pakistan, Jazz, for whom they are exclusive partners running their digital campaigns.

For the most part, Symmetry has been known for its work in the digital marketing side of business but now claims that digital transformation, which involves application of data sciences to create actionable insights, digital strategy, web, software & application development, loT devices and consultancy services have taken over as the other dominant part of the business. What this means is that Symmetry is now essentially a digital technology and experiences company with a focus on the transformation and digitalization of marketing, sales and other consumer centric functions of organizations.

Digital transformation is a booming business that fundamentally transforms how a business or an organisation is run. One of the best IPOs in Pakistan was done by a digital transformation company Octopus Digital, whose initial public offering was oversubscribed by over 27 times.

Symmetry’s clients range from working exclusively with Jazz to big FMCG companies such as P&G, Unilever, Colgate-Palmolive and Gillette. In the banking and fintech space, Symmetry has clients such as HBL, MCB, Faysal Bank and JazzCash; as well as other clients such as Philip Morris International and Khaadi.

Normally, a company the size of Symmetry should be considering listing on the GEM Board of the exchange, launched in 2019. It is

important to note that Symmetry is not a big company, it is a growth company, and the GEM Board listing fits the profile with lower costs and regulatory requirements of the listing.

Perhaps, the rationale behind not taking the GEM route is that listing on the GEM Board might be a fruitless and risky endeavour, since there have been flops on the board. According to officials familiar with the workings of the GEM Board, there aren’t many active investors on the board whereas, on the main board of PSX, retail investors are abundant, presenting a better shot at a successful IPO.

“Symmetry is actually slotted to be the first company to be listed on the SME Board of the PSX. However, the company went through a round of private equity funding at that time because of which the listing was put on the backburner,” says Omar Salah, head of corporate finance and advisory at Topline Securities, the advisor to Symmetry on the IPO.

The company has earlier given a successful exit, a profitable one, to a private equity investor. In 2017, Pakistan’s marketing and advertising firm BullsEye Communications invested in and acquired 51% stake in Symmetry Group at a share price of Rs7.5. The investor, BullsEye, eventually took an exit in 2022, transferring its stake in the company to private equity firm Himmah Capital Ltd. The co-founder of Himmah Capital, Syed Asim Zafar occupies a seat at the SGL Board. The exit transaction saw the shares sold at Rs3.3 per share, a price that was lower because the initial investment by BullsEye was followed by at least three rounds of capitalisation resulting in a lower share price but a profitable sale, according to Adil Ahmed.

That is when the idea for the IPO was also conceived to meet company’s growth targets. At the same time, Symmetry has shunned venture capital investment. Sarocsh Ahmad, the other co-founder and CEO of the company said that Symmetry is past the startup stage, and has become a stable business, generating its own profits, henceforth no longer befitting the profile of a VC investor.

It is now instead poised to make the company public at the main board. According to its Information Memorandum (IM), the Symmetry Group plans to expend Rs307 million from the total raise for the development and launch of five independent intellectual properties (IPs). These IPs will provide SaaS platforms for consumer insights, visualisation of key performance indicators, and other critical information to aid businesses in their decision making process. In short, with the IPO raise, the company plans to increase focus on the digital transformation component of the business.

“The company’s aggressive local and global growth plans require capital investment and our IPO will facilitate this. The capital injection from the IPO will boost the Company’s financial standing and enable it to develop & launch state of the art, innovative & future-tech based products and IPs where AI and data science will be at the heart of everything. In the next 2 to 3 years, all of this is expected to boost share of company’s export earnings to 45%-50% of its total revenues,” Adil Ahmad, founder and executive director at SGL told Profit.

Following the investment, the company projects that its revenue will grow by 38%, reaching Rs 469.9 million in 2023, Rs 642.6 million in 2024 and crossing the billion rupee mark in 2025.

“Digital marketing, which encompasses all media pertaining to Meta, Youtube, Google, TikTok and SnapChat, as well as variations of influencer marketing, the combined spend on these mediums is $175 million in Pakistan, providing Symmetry a great opportunity to grow,” said an expert.

They added that “The digital transformation coming in the country also presents a great opportunity for growth of the company’s transformation division.”

The only question that remains unanswered is whether the IPO would be able to get the right traction and if the target of the raise would be accomplished, keeping in mind the current state of the economy.

The situation of currently listed tech companies is far from well, with some of the best performing tech companies experiencing a markdown in their market valuation. Systems Limited, for instance, has lost about half the value of its stock on the PSX since March 2022, when Imran Khan’s government was ousted and political upheaval translated into economic uncertainty. Avanceon has lost slightly less than half of its value on the PSX, falling from over Rs100 per share in the beginning of March last year to Rs 68 per share by February 9, 2023. Netsol is more or less in its usual territory, with a slight drop in share price, whereas TRG remains the only company that has somehow maintained an upwards trajectory in the last few months. Conversely, TRG is also considered one of the most unpredictable stocks on the PSX and is counted as one that is considerd manipulated, as well.

At the same time, the performance of these tech companies has been better than the other sectors, and in these turbulent times, the PE (price to earnings) multiples of tech sector has been 17x. Furthermore, Octopus Digital had one of the best IPOs for a digital transformation business. So if Symmetry Digital is positioning itself as a business with a

significant digital transformation business on the marketing side of things, chances are that it will also be able to gain significant traction.

Because according to a CEO of one of the prominent marketing and advertising firms, digital transformation is the way to go for the industry. That is what Symmetry now claims it is focused on.

Because of the significantly better performance of the tech stocks, Symmetry’s valuation is discounted to account for turbulent times. “The public offering is being conducted at a significant discount to fair value of the company, based on the business plan.”

At Rs5.50 per share, based on annual earnings for trailing twelve months (TTM), translates to a trailing price to earnings (P/E) multiple of 15.20 times, as compared to industry weighted average of 16.85 times offering a discount of 10% from the industry. At Rs5.5 per share, the price to earnings multiple for Symmetry based on estimates for 2023 comes out to 12.23x post IPO, according to the company prospectus.

“If you look at the historical financials, the company has shown very sturdy growth patterns which are expected to continue in future. Hence, the price of Rs5.5 per share is fairly justified and offers significant upside to incoming investors,” Adil said.

“The stock market has remained rangebound over the past few years and during this time, several IPO transactions have also been concluded. Symmetry Group has growth plans and the capital is required to be injected to successfully implementing these plans,” Adil said, rationalising the company’s decision to go for an IPO during an overall macroeconomic downturn.

“We could have taken the offer for a book build but we decided, keeping in mind the market situation, to offer fixed price so that the company gets the investment and the investor also gets an upside. Hence, it was priced at Rs 5.50 per share,” Omar Salah said.

“Brokers and market participants usually complain that our investors don’t increase. This being a Rs 5.50 per share offering. We’ve priced it as such so that even in conditions like the present, it will attract retail investors. Secondly, and more importantly, there are very attractive valuations in the technology space. It all depends on the products that the company wants to make.”

“Symmetry is also uniquely placed because they have a 20/80 mix of foreign and local. We see that increasing to 50/50 over the next few years,” says Salah.

While the macroeconomic crisis persists, Symmetry remains optimistic. All we can do is wait and see how the company’s ambitious plans with their bold decision to seek an IPO will turn out to be. n

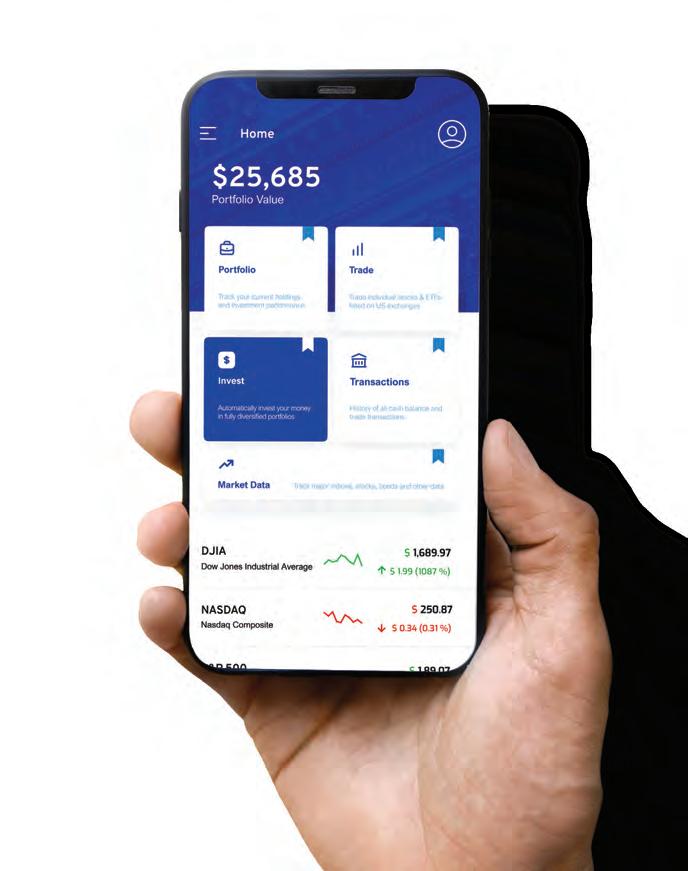

By Muhammad Raafay KhanHave you ever wondered how companies determine the value of their stocks, or how investors decide whether a stock is a good investment?

Stock market valuations play a crucial role in answering these questions and determining the value of a company’s stock.

In the world of finance, stock market valuations are like a detective story, where financial analysts and investors use a variety of methods and models to determine a stock’s worth. From traditional methods like the book value of a stock and the dividend discount model, to more complex models like the discounted cash flow model (don’t worry, we’ll explain these terms in a while), stock market valuations is an art as much as it is a science .

Whether you’re a seasoned investor or just starting to learn about the stock market, understanding stock market valuations is a valuable tool for making informed investment decisions.

So how do we determine the value of a company’s stock in the first place? This is where the art of stock market valuation comes into play. Stock market valuations are an attempt to determine what a company’s stock is worth based on its expected future performance. It’s a way of taking the current and future prospects of a company and putting a price tag on them.

There are many different methods of stock market valuation, each with its own strengths and weaknesses. Some methods, such as the dividend discount model, focus on the expected future dividends that a company will pay to its shareholders. Others, such as the discounted cash flow model, take a more comprehensive

approach and look at the company’s expected future cash flows. Today, we will consider four methods of stock valuations: the price-to-earnings ratio, the price to book ratio, the dividend discount model (DDM), and the discounted cash flow model (DCF). We can’t say for certain which method is the best but a combination of these methods are a good starting point to determine the value of a stock.

This is the most commonly used valuation metric and is calculated as the market price of the stock divided by its earnings per share (EPS). It gives investors an idea of how much they’re paying for each rupee of the company’s earnings. A P/E ratio below 1 suggests that the stock is undervalued while a value above 1 means that the stock is overvalued.

Company stocks usually trade near or above their EPS so the P/E ratio is usually above 1. Let’s take an example of a stock from the Pakistan Stock Exchange (PSX) to better understand this.

Consider the stock of Pakistan State Oil Company Limited (PSO). Currently it has an EPS of Rs 160 while its stock price is around Rs 133. Simply dividing the stock price by the EPS gives us the P/E ratio of Rs 0.83. This means that the stock is undervalued by at least 17% relative to its earnings. The P/E ratio of PSO suggests that an investor looking to make a profit on this stock should buy PSO. However, P/E is only one such factor of stock valuations and it is usually a mistake to base your investment decision on a single point. Which is why let us move to

another method.

This metric is calculated as the stock price divided by the book value per share. It gives investors an idea of how much they’re paying for each rupee of the company’s assets.

The book value of a stock, also known as the net asset value or shareholder’s equity, is a measure of a company’s net assets. It represents the amount that would be left over for shareholders if the company were to liquidate all of its assets and pay off all of its liabilities.

The book value of a stock is calculated by subtracting total liabilities from total assets. The formula for book value per share is: Book Value per Share = (Total Shareholders’ Equity - Preferred Stock Dividends) / Number of Outstanding Common Shares

It’s important to note that the book value of a stock is not always an accurate representation of its true value. The reason for this is that the book value only takes into account a company’s historical costs, not its current market value. For example, a company’s assets may have appreciated significantly in value, but their book value will still reflect their original cost.

In addition, some assets, such as goodwill, may not have a corresponding book value, but still contribute to a company’s overall value. Conversely, some assets may be recorded at a higher value on a company’s balance sheet than their market value, leading to an overestimation of the company’s book value.

For these reasons, the book value is often seen as a useful but limited tool for stock valuation. It’s important to consider other factors,

such as a company’s earnings, revenue growth, and market conditions, when evaluating the true value of a stock.

Continuing with our example of PSO, the total shareholders’ equity according to the latest quarterly report ended September 30th 2022 is Rs 227,343.289 million, which when divided by the total outstanding shares of 469,473,300 give us approximately a book value of Rs 484. Given that the current market price of PSO’s stock is Rs 133 and its book value is Rs 484, we can say that the stock is undervalued by over 73% according to its book value.

However, a word of caution, the book value should be judged with suspicion unless otherwise indicated. So many stocks on the PSX are traded at ridiculously high or low P/B ratios, which means that in many cases, the market forces of supply and demand do not agree with the underlying book value of the stock. It might be helpful to look at the P/B ratio of a stock historically to get a better idea of how close the stock price is to the book value of the stock.

In the case of POL, investors should also look at the details of the net assets held by the firm to get a better idea whether the book values of the assets are being fairly reported. Nevertheless, sometimes a company’s share does trade far above or below its book value.

This model values a stock based on the present value of its expected future dividends. Dividends are basically income that you get from owning a stock which companies can pay every quarter to once a year.

The Dividend Discount Model (DDM) is a method for valuing a stock based on the present value of its expected future dividends. It assumes that the stock’s value is equal to the sum of its expected future dividends, discounted back to their present value.

Here is how the DDM is calculated, step by step:

1. Determine the expected future dividends: This involves forecasting the dividends that the company is expected to pay out in the future.

2. Determine the discount rate: The discount rate represents the opportunity cost of investing in the stock, taking into account factors such as inflation and the risk associated with the investment.

3. Calculate the present value of the expected future dividends: This involves discounting each expected future dividend back to its present value using the discount rate. The formula for this is: Present Value = Future Dividend / (1 + Discount Rate)^n

where n is the number of years into the future that the dividend is expected to be paid.

Sum the present values of all expected future dividends: The sum of the present values of all expected future dividends represents the stock’s current value according to the DDM.

It’s important to note that the DDM is a simplified model and that many factors can affect a stock’s actual value. For example, the model assumes that dividends will continue to be paid at the same rate into the future, which may not be the case. Additionally, the model does not take into account changes in the company’s financial condition or the growth potential of its business.

For these reasons, the DDM is often used as a starting point for stock valuation, but it’s important to consider other factors and use additional methods of valuation to get a more complete picture of a stock’s true value.

This model is similar to the DDM in that it values a stock based on the present value of its expected future cash flows. The basic idea is that the stock’s value is equal to the sum of its expected future cash flows, discounted back to their present value. The step by step process of making a DCF model is as follows:

1. Forecast future cash flows: This involves projecting the cash flows that the company is expected to generate in the future, taking into account factors such as revenue growth, operating expenses, and capital expenditures.

2. Determine the discount rate: The discount rate represents the opportunity cost of investing in the stock, taking into account factors such as inflation and the risk associated with the investment.

3. Calculate the present value of the expected future cash flows: This involves discounting each expected future cash flow back to its present value using the discount rate. The formula for this is:

Present Value = Future Cash Flow / (1 + Discount Rate)^n where n is the number of years into the future that the cash flow is expected to occur. The formulas for both the DDM and DCF models are basically the same except that one uses future dividend while the other uses future cash flow Sum the present values of all expected future cash flows: The sum of the present values of all expected future cash flows represents the stock’s current value according to the DCF model.

It’s important to note that the DCF model is a complex and time-intensive method of valuation, and it requires a high degree of accuracy in the forecasted cash flows and discount rate. Additionally, the model may not always reflect the market’s perception of a company’s value, which can be influenced by a wide range

of factors, including the company’s financial condition, growth potential, and overall market conditions.

These are some of the most widely used stock valuation methods, but there are others as well. It’s important to remember that no single valuation method is perfect and that a combination of methods is often used to get a more accurate picture of a stock’s true value.

Warren Buffett, widely considered one of the greatest investors of all time, has a well-known and successful approach to stock market valuations. His approach is based on a long-term investment philosophy that focuses on finding undervalued companies with strong growth potential and a durable competitive advantage.

Here are some key elements of Buffett’s approach to stock valuations:

1. Focus on intrinsic value: Buffett believes that the value of a stock should be based on the underlying value of the company, rather than on short-term market trends or speculation. He calculates the intrinsic value of a stock by looking at the company’s financials, including its earnings, revenue growth, and balance sheet.

2. Look for companies with a durable competitive advantage: Buffett looks for companies that have a sustainable competitive advantage, such as a strong brand, a loyal customer base, or a valuable intellectual property portfolio. These companies are more likely to perform well over the long term, even if the market experiences short-term fluctuations.

3. Consider the quality of management: Buffett places a great deal of importance on the quality of a company’s management team, and he looks for managers who are honest, competent, and focused on long-term value creation.

4. Avoid overpaying: Despite his focus on long-term investments, Buffett is very mindful of the price he pays for a stock. He will not buy a stock that he believes is overvalued, even if he thinks the company has a strong growth potential.

5. Focus on simplicity: Buffett has a preference for simple and straightforward investments, such as well-established companies with a clear and understandable business model. He believes that these types of investments are less likely to be impacted by market volatility and are easier to understand and evaluate.

These are some of the key elements of Buffett’s approach to stock market valuations. While his approach is not the only way to value stocks, it has proven to be extremely successful over the years, and many investors look to him as a role model for long-term investing success. n

We are starting a new chapter in banking reforms. I want to praise the recent developments and the future evolution of digital banking in the larger context of digital Pakistan strategy and the financial sector reforms, which does not end. Digital banking and eCommerce are ingredients of overall digital strategy. I would like to limit my remarks on the financial sector and how digital banking fits into that. We should not forget the purpose for which the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) is promoting digital banking. And that is it is an effective tool for strengthening intermediation and financial inclusion in the country in the pursuit of larger, equitable and sustainable development of Pakistan.

We should not barely focus on a small piece but contextualise what is the actual purpose of digital banking.

Let me add a caveat: the banking sector’s performance can not be isolated from the overall macroeconomic environment. When the environment is stable and the track record in management and governance is sustainable, the banking sector does wel l. Under the present fragile, fluid and uncertain environment, it w ill be unfair to expect from the banks and other financial sector in stitutions to do well. But that is context for the present. What w e are talking about is the future and I don’t think the present situa tion will persist.

It is important to highlight the evolution in banking centre

reforms. The first generation of reforms started in the 1990s and got an accelerated momentum in early 2000s and it focused on liberalisation of the financial system, privatisation of nationalised commercial banks, autonomy and capacity building of the State Bank, pricing of financial products and evolution of direct credit ceilings and reliance on markets mechanism for allocation of credit. Recovery of non performing loans was stepped up by forming a corporate and industrial restructuring corporation.

A code of corporate governance was enacted and forced through a three or four tier structure. Appointments of CEOs were made on a predefined fit and proper criteria so that charlatans can not come and occupy this space. A number of banks were asked to either wind up businesses or merge, and delinquent boards were suspended or dismissed, creating a deterring effect to malpractices. Other reforms were also undertaken.

As a consequence of the first generation reforms, 80% of the banks became private banking assets. Instead of subsidies from the exchequer, banks have become profitable and last year they contributed Rs 200 billion in the form of corporate taxes. Quality of human resources inducted became high and technology started to seep up in the operations. Financial performance indicators went upwards to meet the and non performing loans shrunk to single digit.

Despite these achievements, I am not very satisfied with the progress. There is a lot of fluidity as far as the banking sector is concerned. A large number of issues and problems have surfaced since the completion of the first generation reforms that need to be resolved.

The outreach of the newly privatised banks, earning huge profits, remains limited to corporates, big names and high net worth individuals, trade financing and fee based activities. They did not make any efforts to extend credit to underserved sectors such as the SMEs, small and medium farmers, low cost housing, personal and consumer financing. Their network in underdeveloped areas was confined to deposit mobilisation rather than lending. Prudential regulations were amended to enable the banks to lend to these sectors. To broaden the acces s to new modes of banking institutions that were introduced were firstly, the ones that shunned b anking due to their faith were given the opportunity to choose Islamic banking which offered Shariah compliant products. The other set of institutions was microfinance banks.

We took pride in becoming the first central bank in the world to regulate microfinance banks. We were advised against it but now, most of the central banks a round the world are regulating microfinance banks. That is what we had done in order to cater t o the people at the lower end of the spectrum who never had access to finance.

We moved into microfinance to serve women entrepreneurs but the progress has not been great and they are still confined to big cities and have not gon e into small towns or the rural areas.