13 minute read

Chicken and affordable protein

The price of broiler chicken has increased to more than Rs 400 per kg lately, largely due to supply chain constraints, and a complete breakdown in the supply of animal feed, that eventually leads to production of chicken, and eggs – whichever comes first remains up for debate.

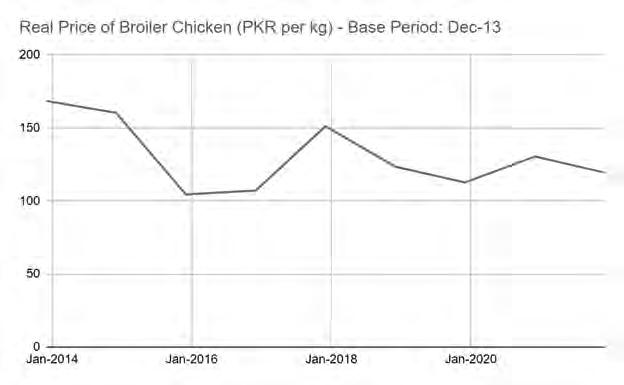

Adjusting for seasonal, and supply-shock related spikes, the price of broiler chicken has consistently remained in the range of Rs 150 to Rs 200 per kg over the last 10 years, as it became the affordable, and sought-after animal protein given increase in prices of other animal proteins. After adjusting for inflation, and in real terms, the price of broiler chicken has also stayed within a range, and as of December 2022, it remains lower than December 2013, despite elevated supply shock driven price levels.

Advertisement

Even though a significant proportion of animal feed for the poultry industry is imported, in a competitive market, little influence of government in setting arbitrary prices, lower barriers to entry and exit has led to creation of a thriving market for poultry. Although the industry remains susceptible to external shocks, such as diseases that may wipe out flocks across the board, the supply continues to increase in-line with increasing demand. Furthermore, the ability to scale up production has allowed market participants to benefit from economies of scale, eventually resulting in lower prices for the final product for the consumer.

Despite significant broad-based and food inflation across the board during the last 10 years, the increase in price of broiler chicken remains considerably lower than other items. It may also be noted here that in the case of other animal protein, such as mutton or beef, the price has continued to increase, and real prices have moved upwards, whereas for chicken, the real prices have either declined, or remained stable adjusting for any supply shocks. Beef and mutton supply is scattered, and cannot leverage any economies of scale.

Due to absence of any disease free zones, and lack of information regarding vaccination, beef and mutton never really scaled up, due to which they could not benefit from any potential gains in productivity, and efficiency. Before the depreciation of the Pak Rupee, the beef and mutton produced locally was not even competitive, while also not meeting base level quality requirements for export markets. There exists a case to enhance efficiency in production of animal protein, such that the country can start exporting the same, while also reducing prices of other animal protein in real terms.

The country’s population will continue to grow, and so will demand for protein as increasing income levels will increase demand for protein, as it becomes a greater part of the nutrition pie. The productivity and efficiency gains in chicken that have led to stable prices in real terms can also be replicated for other proteins, while also opening potential avenues for export. There exists a strong case for indigenising animal feed sources as much as possible to enhance competitiveness for the final product.

There also exists a case for development of more resilient supply chains, whether that is through development of disease-free zones, or through enabling tracking of proteins, and setting and enforcing vaccination, and other phytosanitary standards. A resilient supply chain is not just restricted to infrastructure, but also to the resilience of financial infrastructure, as can be seen in prevailing circumstances where inability of market participants to import basic inputs led to a ripple effect in supply chains, eventually leading to higher protein prices for the consumer.

There needs to be a deeper focus on how food security needs to be ensured, and through what levers. Food security should not be just about ensuring availability of product, but also its affordability, and the productivity gains that can be unlocked. If we want to feed our population, we need to rethink food supply chains, and productivity – without which we will be forcing the population towards a more intense sustenance and nutrition crisis in the times to come.

What is luxury? And who gets to enjoy it in a regime of controlled markets?

By Shahnawaz Ali

hat do you think of when someone says the word luxury? Is it silk robes, satin gowns and marble floors befitting a Roman Emperor? Or is it finely cut Italian boots, long cars with leather seats and a serving of albino caviars on a cruise yacht?

The word itself has a problem — there are no set limits to what is and what isn’t luxury. In Pakistan, for example, the definition of luxury may be a Toyota Fortuner, lamb chops,

Imports

and throwing away gold coins at a wedding. Yet when the government gets involved, the definition of luxury becomes very important for one major reason: imports.

WAs Pakistan’s reserves have withered away and the economy has entered dire straits, the government has been trying everything other than concrete measures to plug the gap. One of these measures has been restricting imports. The only problem is, while stopping Baskin Robbins ice cream, cars, or Happy Cow cheese from entering Pakistan to save dollars is well and good, how many dollars is this really saving us? And more importantly, are there possibly crucial items that are imported in Pa- kistan and cannot be categorised as a luxury?

Look at it this way: The import component in a meal of daal fry with roti and a cup of chai is upwards of 85%. It is important to note that the aforementioned meal is the simplest meal any Pakistani has grown up thinking of. This is not luxury and how Pakistan got to a point where we became so insecure in our staples is a whole different yet relevant question. Items as basic as feminine hygiene products, medicines, wheat, daal, and petrol. Pakistan was able to shrink its current account deficit for the first half of the fiscal year, by 60%, in December 2022. This figure was achieved by first banning luxury imports and

Dr. Aqdas Afzal, Professor of Economics, Habib University

then later monitoring the import of goods, case by case. Having achieved a low figure of current account deficit, has Pakistan really achieved the goals of economic austerity? And what do banned imports mean for a free market economy?

But more importantly, who gets to define what luxury imports are? What is the mechanism that is followed in categorising luxurious imports? What portion of our imports can in fact, be categorised as luxurious? How does a ban spill-over into the market, at large? And is this really the solution to the problem(s) that is faced by Pakistan?

What is the problem with importing?

Acountry requires foreign exchange to import stuff. To put it simply, a country, much like a household, has a current account. Wherein, what it buys, has to be justified by what it earns. These earnings are shown in the terms of that foreign exchange, or in this case dollars. Pakistan earns this foreign exchange by either exporting goods and services, and receiving dollars in return, or through deposits and remittances.

When a country spends more than it earns, it runs a Current Account Deficit (CAD). Contrary to popular belief, running a current account deficit is not the problem, the problem is how big that differential is and how it is going to be sponsored. If a country cannot readily afford to run a CAD, it generally falls in a Balance of Payments crisis.

Pakistan has been running a current account deficit for the last few years. And it has increasingly become difficult to fund that deficit. There are two ways to reduce this deficit. One is that you start exporting more and start receiving more in remittances. And another way to reduce this gap is to reduce imports.

Much like a household, whenever a higher CAD is run, the people often get lectured by the higher ups to bring moderation in their spending habits. A minister of state went on record to tell people that their tea drinking habits might actually be responsible for the country’s economic woes. Now imposing restrictions on your own kids might be easier, but treating a population in excess of 220 million as children is a different ball game. Regardless, in the greater interest of the country, the government decided to impose these restrictions. But this gives rise to another, more fundamental question. One that was asked at the beginning of this article, what is luxury? What started off as a ban on some “luxury” goods in May, later turned into more and more bans. To the point where everyone importing anything had to get an approval of necessity, from the central bank. Semantically, what is not necessary could effectively be deemed as a luxury.

How are imports categorised?

In Pakistan, goods are categorised under the Pakistan Imports and Exports Control Act, 1950. This is a “Harmonised Commodity Description and Coding System” (H.S Codes), known as Pakistan Custom Tariff/ PCT codes. These goods are clubbed together with their individual codes under hundreds of groups of commodities from a customs clearance perspective. The nature of the division is such that most of the codes don’t differentiate between high ticket and low ticket items. For example, the Custom PCT code number 02.01, “Meat of bovine animals” has 3 subcategories, Carcasses and Half Carcasses, Other Cuts with bone, and Boneless. The distinction is based on size and bone presence, not on the basis of, say, wagyu meat and a common cut of beef.

In April 2022, at the onset of the new government, Pakistan adopted a new imports policy where Import Policy Order 2022 was imposed. It was later amended to be much more strict on the 19th of May. The SRO 598, issued on the 19th of May, prohibited the import of different products under 85 groups of commodity description as per the PCT codes. Some of the prominent members were. Mineral Waters, Auto CBUs, Carpets, Chandeliers, Chocolates, Sanitary and Washroom products, and Pet foods etc. Within days, the government realised that what they had done was going to have impacts beyond their current account goals.

Eleven days later the ministry issued another SRO, announcing that any raw materials in the earlier order were exempt from the ban. A month and a half later, another SRO stated that any imports that had already reached the ports would be cleared, imposing a 5-15% surcharge on the clearance. On the 23rd August, all CBUs and machinery were also allowed to clear subject to a 100% surcharge (these imports are being processed over time).

In October, Pakistan’s foreign reserves dropped to dangerously low levels. This resulted in an even tighter control on imports by the State Bank itself. But before that, by the looks of it any sizable import was allowed through (at a cost) and the ones left behind were the items not as desirable. Which begs the question, whether the impact these items create is big enough to reduce Pakistan’s imports? And was it this “categorization of luxury” that led Pakistan to an even bigger liquidity crisis?

How big is luxury consumption: Food’s share of the pie

Apopular group that was hit by the import bans is food. Be it Pastas, confectionery , fish, chocolate, processed meat, fruits and dry fruits. But here is where it gets tricky. When we look at Pakistan’s import payment receipts, the largest portion of food imports does not go to kit kats and salmon rolls. It goes to palm oil, wheat, pulses and soybean oil.

As appropriately pointed out by an economist Ammar Habib Khan in a tweet, the import component in a meal of daal fry with roti and a cup of chai is upwards of 85%. It is important to note that the aforementioned meal is the simplest meal any Pakistani has grown up thinking of. This is not luxury and how Pakistan got to a point where we became so insecure in our staples is a whole different yet relevant question.

To make matters simpler, we look at the import payment receipts by the state bank, these commodities are divided into 8 groups. The 8 groups are Food, Machinery, Transport, Petroleum, Textile, Agriculture, Metal, and Miscellaneous. For the last one year, an average 9% of our imports every month have been pulses. Similarly, 40% as Palm oil, and 6% as Tea have been consistent whereas wheat, sugar, vegetables, spices and even dried fruits make guest appearances every other month based on the newest agricultural crisis. The combined proportion of all the other foods that have been imported in Pakistan in the last 1 year is close to 20%. It is important to remember that all these other food imports have a total of at least 100 groups in the PCT codes, each one of which has further categories. Banning 10 of these groups raises serious questions in impact evaluation.

Despite the many administrative measures, the import payments for food between Jun-Sep 2022 ($2,647,013,000) was almost identical to the previous year’s Jun-Sep bill ($2,659,280,000), a 0.4% decrease.

The reason for that was that any reduction that could have been observed was eaten up by wheat, soybean, and sugar. The real impact is seen afterwards, since the scrutiny on the release of Letters of Credits was increased by the State Bank in October. Only necessary imports were cleared and unnecessary ones were stopped, despite all the categorization done earlier. This helped achieve the num-

23,696,958 bers for reduced imports but also reduced the export number. This caused supply chain disruptions, causing industries to shut down and producers to withdraw.

Another thing with food is the age-old law of averages. This gets clearer when you look at the pricing of buffet menus. When it comes to food, there is only so much a group can consume, both in terms of quantity and nutrition requirements. After a certain upper cap is reached, adding or subtracting dishes does not make a difference in the total price of the buffet, because whatever a person might miss out on in one dish, he will wake up for, in another.

That is something that can also be observed in food in general, specifically in the case of diversified PCT codes of “All other food imports”. With a growing population, this food bill is bound to grow. If cut down from one side, the impact will become visible in another item. A packet of Italian cheese may be an expensive import, but is the alternative food completely homegrown? So while aiming for high ticket value might be the best myopic solution, food will always be a problem as long as we import components of all the food that we eat. A more pertinent way to look at this problem could be by decreasing the imported percentage of the most highly consumed food, or simply by disincentivizing the consumption of imported staples. And this is where the question of political popularity with the masses pops up. A deal-breaker.

Non-Food Imports

The argument for non-food luxury sounds saner in comparison. That is, if the person who makes it, also stands by it. Most of the Auto

23,490,002

CBU imports, up until August have been cleared under legal guise, the processing of which is being done over time. The only victim was the consumer or in this particular case the Auto industry.

Similarly, machinery imports were reduced during the same period, by almost 29%. But the LSMI during the Jul-Nov period in 2022 has also been down by almost 4% YoY, wherein, November alone saw a hit of 5%. The data for December onwards has not been released yet, which would be drastic considering the major industries closed after that.

Despite imposing bans on luxury on the 19th of May, Pakistan imported its biggest consignment of petroleum fuel worth $2.8 billion, in June 2022. To jog our memory, a subsidy on fuel had yet to be completely taken off throughout the month of June. The reasonable explanation of this import decision is as unreasonable as political gains.

Although there was a huge decrease in the transport group and the machinery group, that effect was totally subsided by the imports of staples like petroleum, wheat and pulses. This was to an extent that the difference between the total imports of both the periods in their respective financial years was 0.87%.

The non-luxurious impacts of banning luxury

When the government intervenes to an extent this great in a market, there are bound to be problems. This ban started

Total Change after import ban: 0.87% decrease from a child’s unfulfilled wish to consume a Milky Way bar, but has now come to our ability to afford Chicken and daal. A simple case of soybean containers is a prime example of how intervention causes havoc across the industry. And there is more than one cost to be borne when restricting imports. It can range from reducing competition to disturbing supply chains. Even if we ignore the impact of the problems caused by monitoring of the LCs, in the last 3 months. The banning of some imports alone, results in lack of productivity in the current markets. With decreased competition and protection available, the local producer will always target the lowest common denominator of quality. This phenomenon can be observed in large scale manufacturing already and is all set to trickle down into small businesses.

It is also extremely detrimental to investor confidence in any market, “No investor would want to invest in a country that doesn’t even provide them with the basic freedom to import raw material. This creates yet another hurdle in the way of incoming FDI”, says Dr. Ikramul Haq, Advisory Board Member PIDE and Visiting Faculty Member at LUMS.

Total change: 0.4% decrease

Conclusion

There is a subjectivity that surrounds categorization of goods as luxury or non-luxury, one that was referenced in the start. Cat feed becomes a luxury when your vantage point is a 4-canal bungalow in Gulberg, but a rural shelter might still need some of that feed for its under-nourished cats. Pasta looks like a luxury when eaten at an expensive restaurant, but not when you eat sawaiyan at home on Eid.

A leading group of people are of the opinion that a ban is something that Pakistan has had to do as a last resort. Dr. Aqdas Afzal, an economist at the Habib University, told Profit that, “Since the exports are not going up in the short-run, it seemed necessary for the government to keep the exchange rate stable by running a break-even current account so that prices remain in check. But it is not something that can be done as a medium to long term strategy. Even high ticket items like cars, when stopped manufacturing, cause massive unemployment”.

And no country wants to paralyse its industry. There is a lot of weight in the arguments for controlling imports, as of January 2023. But was this the case 4 months ago? Political war-mongers will get away by quoting a reduced CAD figure. But as of now, the industry, which is our only hope out of the BoP crisis, is choked for production.

There is a long standing consensus on the issue of imports and that is import substitution. Almost all the political leaders, and experts agree that this problem can only be solved if substituted, but that cannot be done without providing breathing space. Because what other option does the government have? Do we change how and what the people eat? What do they wear? Do we change our consumption habits overnight? As wishful as it sounds, even if the people stop consuming one thing, in a failed state, the then adapted substitute will also have to be imported eventually. There is room to come out of simplistic notions and strawman arguments. If Pakistan is to look towards a long term solution the short term solutions should not be cutting the very branch that we are hanging from. n