08

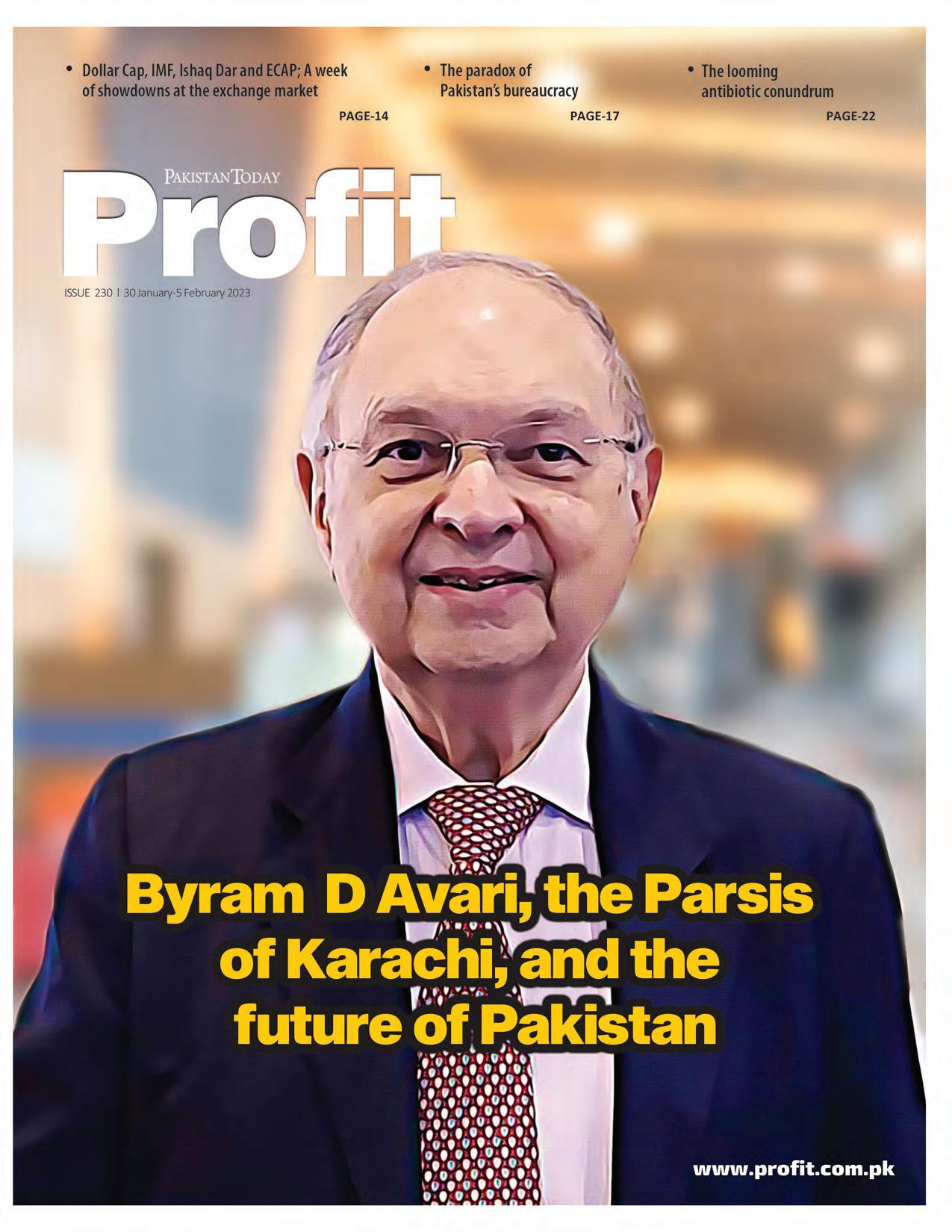

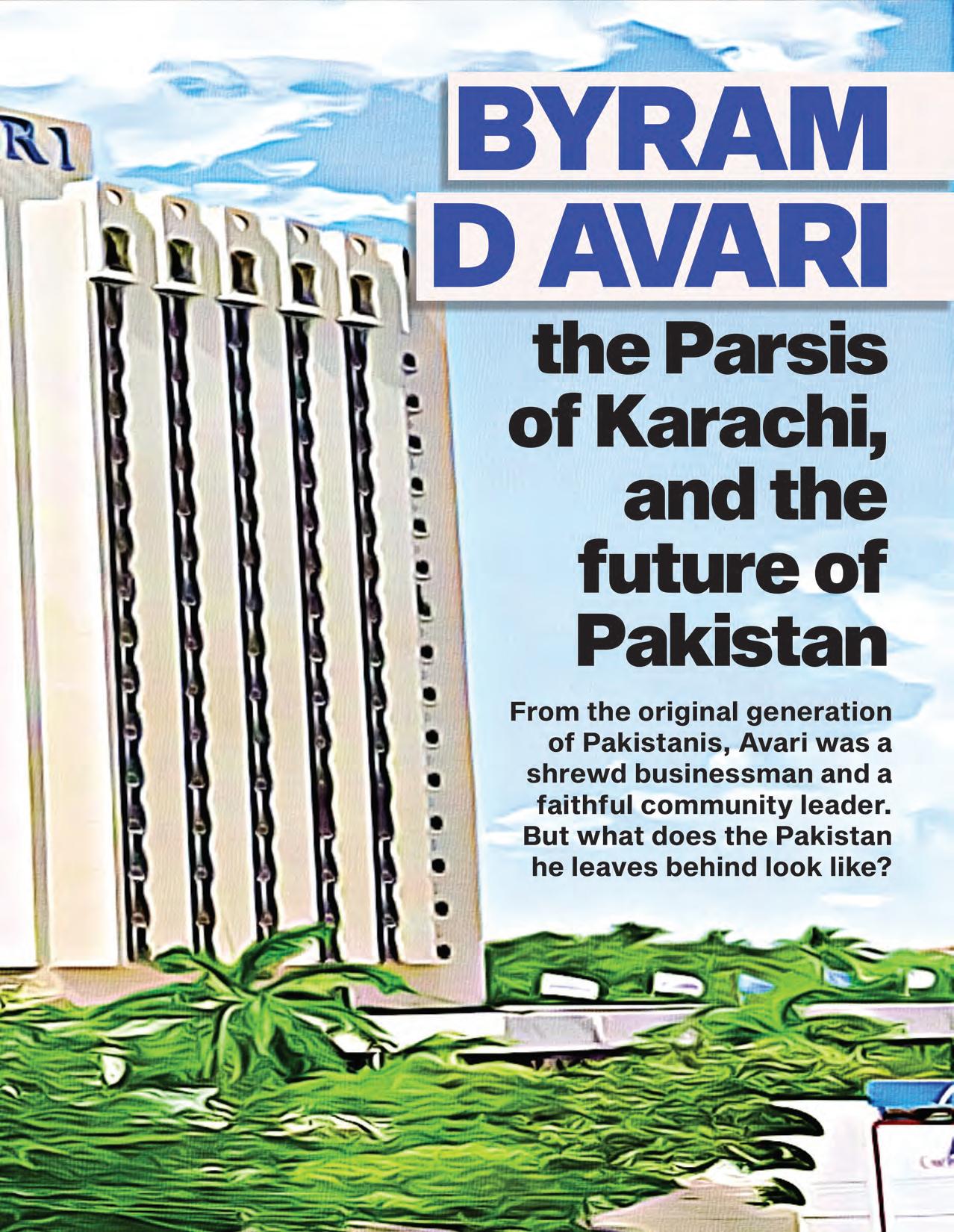

08 Byram D Avari, the Parsis of Karachi, and the future of Pakistan

14

14 Dollar Cap, IMF, Ishaq Dar and ECAP; A week of showdowns at the exchange market

14 Borrowing from the public Ammar

H Khan

18 The paradox of Pakistan’s bureaucracy

22

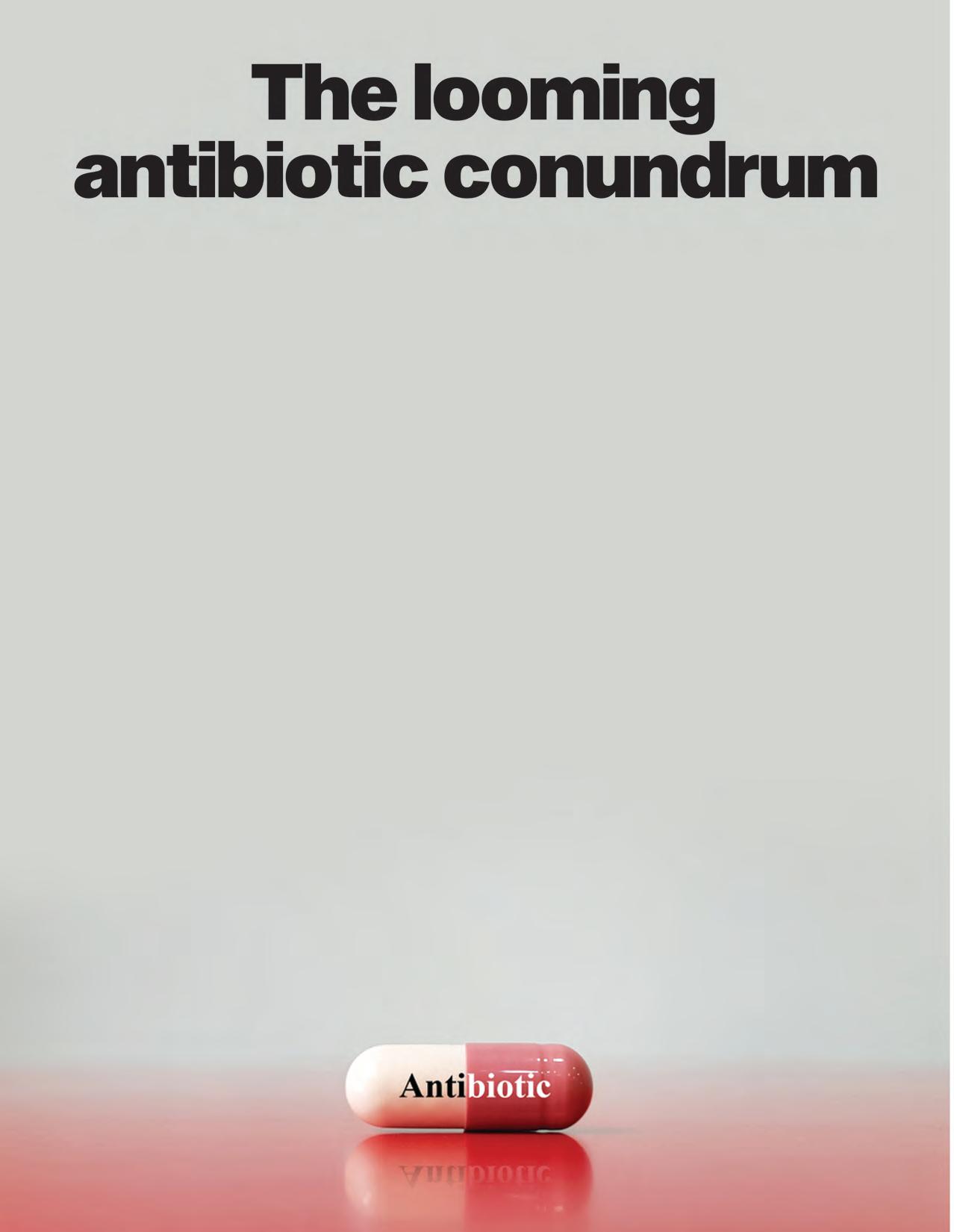

22 The looming antibiotic conundrum

25 Funding vs execution - lessons for Pakistan

Publishing Editor: Babar Nizami - Joint Editor: Yousaf Nizami

Senior Editors: Abdullah Niazi I Sabina Qazi

Chief of Staff & Product Manager: Muhammad Faran Bukhari I Assistant Editor: Momina Ashraf

Editor Multimedia: Umar Aziz - Video Editors: Talha Farooqi I Fawad Shakeel

Reporters: Ariba Shahid I Taimoor Hassan l Shahab Omer l Ghulam Abbass l Ahmad Ahmadani l Muhammad Raafay Khan

Shehzad Paracha l Aziz Buneri | Daniyal Ahmad | Ahtasam Ahmad | Asad Kamran l Shahnawaz Ali l Noor Bakht l Nisma Riaz

Regional Heads of Marketing: Mudassir Alam (Khi) | Zufiqar Butt (Lhe) | Malik Israr (Isb)

Business, Economic & Financial news by 'Pakistan Today'

Contact: profit@pakistantoday.com.pk

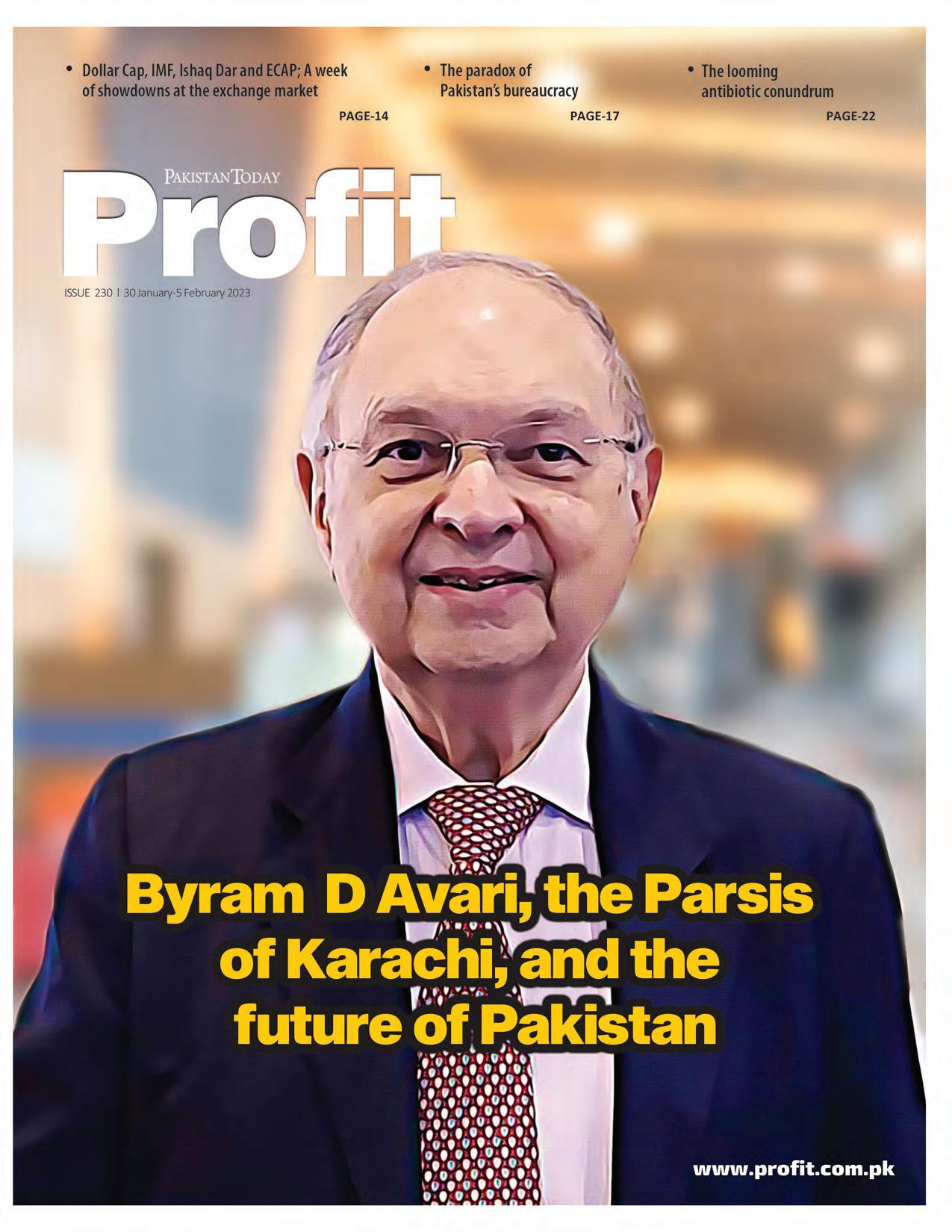

There is an air that surrounds the Indian subcontinent’s Parsi community. It is the sort of local fascination that the rest of the world could never understand. Found in small, close-knit, and affluent groups the Parsis of Bombay and Karachi in particular are famed custodians of the inextricable trinity of wealth, high-culture, and social capital.

In both these cities, they have their own neighbourhoods, their own community centres, their own customs, places of worship, and businesses. All of these aspects are stitched together to create the veil of mystique that hangs over them. It is also a community that is fast disappearing.

Karachi’s Parsi Colony, a clean, gated enclave, is dotted with enormous mansions and bungalows with sprawling lawns, shady trees and huge balconies. The colony is different from the rest of Karachi. For one it is not cramped. If a stranger to the city were to be blindfolded and enter the area, they would never believe that Karachi has a real estate or a population problem. In the middle of Pakistan’s embattled metropolitan, it is the remnant of a time gone by, of what an imagined past might look like. It is a place where one would expect polite evening teas, brisk walks early in the morning, pedigree dogs, big cars and all the other things that come with money.

Its other distinguishing feature is silence.

Over the past few decades in particular, there has been an exodus from the Parsi Colony. Houses are boarded up, businesses have sold out or shut shop, the streets are empty and most of Pakistan’s Zoroastrians have moved abroad in search of greener pastures. That is a story that is all too familiar. A country with baggage, a fraught political system, a boomand-bust economy, and appalling human development indicators is not a place anyone wants to live, do business, or raise their children. That is why, perhaps, Pakistan’s brain drain situation aggravated last year, as more than 750,000

educated young men and women chose to seek employment overseas mainly because of the uncertain economic and political situation.

As a small minority community, the Parsis have given the subcontinent a disproportionate number of household figures. Names like Cowasjee, Marker, Malbari, and Wadia are etched into the history of this region. Yet in Pakistan, perhaps no name holds as much weight or prominence as Avari.

Last week saw the passing of Byram D Avari, who died of a brief illness. A highly respected business figure in Pakistan, he was also a prolific swimmer, a gold-medalist in yachting, and perhaps, most significantly the quiet, genial figurehead of Pakistan’s dwindling Parsi community. He leaves behind two sons, Xexeres and Dinshaw, and a daughter, Zeena. He was 81.

As the Avari family grieves the loss of their illustrious patriarch, it is worth looking back at his life and taking stock. On the one hand, he was a famed business personality that grew and moulded his father’s legacy. On the other hand, he was perhaps one of the last men and women that represent a Pakistan that could have been — a generation that more than anything embodies and personifies a lost opportunity.

In the next decade, something monumental will happen. Somewhere either in a noisy Lahore suburb, a quiet village in interior Sindh, or the walled city of Peshawar the

last person that was a full-grown, legal, adult at the time of partition will breathe their last. And with that, the generation that was to have built Pakistan will die out. Anyone who was at least 18 years old when Pakistan gained independence is currently 93.

At the time of partition, Byram D Avari was five-years old. As a child still forming core memories, Pakistan was the first home Byram would ever know. He was part of this rare generation that had the distinction and opportunity to craft and build a nation. These were the first doctors, lawyers, civil servants, soldiers, farmers, businessmen, and political leaders that were native to Pakistan. Their efforts were to determine the course the fledgling nation would inevitably chart.

And among them, Byram had a unique position of privilege. His father, Dinshaw Avari, was an up-and-coming star. A truly self-made man, Dinshaw had been raised at an orphanage after losing his parents young. Educated and taken care of by the Parsi community, he managed to find a career in insurance for himself and made good money from this professional path. However, business was his true calling and he left a successful career to start his own line of hotels. After rigorous training, Dinshaw acquired the Bristol Hotel in Karachi in 1942 — the same year that his son Byram was born.

Built in 1904 for the Raj, The Bristol was known for its parties and good food but had been on the decline. By the time Dinshaw started running the place and brought it back to its previous glory, Pakistan was born. Over time, using the money he made from Bristol and other investments, Dinshaw went hotel shopping. He bought Beach Luxury Hotel in 1948, Nedous Hotel in 1961 laying the foundation for the family’s own ‘Avari’ hotel chain which would be formally inaugurated in 1978.

As a young man, Byram was close at his father’s heel as he learned the hotel business and absorbed the strong protestant work ethic that his father had built his fortune on. And at the same time, he was also a man about town. As the scion of a successful Parsi business family, Byram had ins with the who’s who of Karachi’s social and intellectual elite.

No one is quite sure when and how the Parsis of Karachi all so simultaneously man-

“During COVID, we took out a loan of about Rs 700 million to pay salaries so that no one would go hungry; we continued their medical allowance even though our hotels had closed down and they were sitting at home”

Dinshaw Avari, sonIn Karachi’s Parsi colony, the streets are growing increasingly quiet as members of the community go abroad to find greener pastures.

aged to make their fortunes. What we do know is that there was an exodus from the community from Bombay to Karachi somewhere in the early 19th century. From here the Parsis got into business of all kinds. In a country where minorities have not fared well, the Parsis are an anomaly. Not only do they, by now, come from old money, they are entrenched so deeply in the social fabrics of Karachi that their place has nearly become unquestionable.

It is worth imagining how Pakistan may have fared if minorities other than the Parsis had been allowed to thrive and contribute to this country. At the time of partition, Pakistan’s Hindu population stood at nearly 20%. In the time since, it has fallen to barely 1.5%. Similarly, the Ahmadiyya community has regularly been persecuted, with examples of their businesses (such as Shezan) being boycotted and attacked because of the faith of the owners.

Atrue Karachi-boy, one of his first loves was the sea where he spent countless hours yachting and sailing. While his father grew and expanded the family hotel business, Byram became an avid sailor. Back in those days, yachting as a sport was an expensive hobby maintained either by rich philanthropists or officers of the Pakistan Navy — essentially people with access to yachts.

As Byram’s passion grew, so did the seriousness with which he approached the sport. In 1976, the pair of Byram Avari and Munir Sadiq of the Pakistan Navy won the Enterprise Class gold medal in the 8th Asian Games held in Bangkok. Byram Avari again won gold in the same class at the 1982 Asian Games in India, this time with his wife Goship Avari as his yachting partner.

In 1978, the same year that his father officially inaugurated the Avari Hotel chain, Byram also began to serve as commodore of the Karachi Yacht Club. Yet even as his career in sports grew, Byram was the heir to his father’s legacy and fortune. Yachting may have been a lifelong passion, but in 1988 Dinshaw passed away and Byram succeeded him as chairman. Far from a muscle-head sportsman, Byram took the reins and grew the Avari empire with an eye on international expansion. In 1995, Avari Dubai was built and 2008 luxury Avari suites in Mall of Emirates in 2008. As of now, they operate the 200-room four-star hotel in Dubai, and manage the 200-room Ramada Inn in Toronto at Pearson Airport in Canada. In 2005, Avari Hotels received the internationally renowned World Travel award that marks excellence in all sectors of the tourism industry. The hotel chain became the only Pakistani enterprise to receive the award for eight consecutive years until 2013. In these years of success, there were obviously troubles. In an article published in 2008 in Fezana, a journal for Zoroastrian, Avari’s son Dinshaw (named after his grandfather) mentioned that the Avari Beach Luxury Hotel struggled a lot when Martial Law was imposed, alcohol and night clubs were banned. It halted the foreign tourism, a major clientele of the hotel. The business faced losses but no staff was retrenched.

This was an outlook that Byram carried

with him, and Avari’s HR policies have remained worker friendly. An academic study conducted by Namra Rehman and Dr Atif Hassan showed that Avari offered benefits to its employees which no other hotel does. This includes flexible working hours, health insurance to staff and their families, free meals during working hours, free transport to female staff, yearly appraisal and provident fund. This helped enhance the working culture of the hotel which translates into the overall performance of the hotels.

When Profit reached out to Beach Luxury Hotel’s staff, we learned similar things. His personal secretary, who sits at the Beach Luxury Hotel said that, “Mr. Byram looked after his employees really well. During covid lockdown, the hotel was shut for a while but he still did not terminate anyone.” In a conversation with Profit, his son, Dinshaw said, “During COVID, we took out a loan of about Rs 700 million to pay salaries so that no one would go hungry; we continued their medical allowance even though our hotels had closed down and they were sitting at home.”

“A lot has happened in this time, In the post 1971 era, there were a lot of non-Muslims that were driven out of the city and many recommended the Avari family to move out too, but our family preferred to stay because we were responsible for more than just our home, we had to take care of the hotel,” his son explains.

“My father managed every single situation. He said life goes on and we have to adapt and adjust to every single situation. His motto was ‘go with the flow’ and no matter wha happened, he never wanted to leave Pakistan,” says Zeena, Byram’s daughter. “He believed that he was what he was only because of the land he was from.”

Byram led a storied life. As a businessman, as a sports player, and as a leader of his community, he watched as Pakistan grew and turned into a shadow of what it was supposed to be. “He was a well connected man. All the politicians know him well. He was a community person and that’s

“My father managed every single situation. He said life goes on and we have to adapt and adjust to every single situation. His motto was ‘go with the flow’ and no matter wha happened, he never wanted to leave Pakistan”

Zeena Avari Aga, daughterAvari Hotel Lahore - still a go-to hotel for people visiting Lahore and regularly the hub of different gatherings and events vital to city life.

why Beach Luxury Hotel also hosts a lot of events from various age groups. Sometimes the events are charged at discounted price or even free of cost, such as the function held by the blind trust association,” his son tells us.

Much of the social capital at the disposal of Byram and the Avari family comes from their unique position as the leading Parsi family in Pakistan. As mentioned earlier, the Parsi community has not had the lot of other minorities in this country. Money, education, and a pretence towards art and culture have given them a special sort of immunity. But Byram was a man well aware of this, and used this very privileged position to be an ardent defender of minority rights in Pakistan.

Byram became a member of the parliament in 1988 as the representative of minority communities elected on a reserved seat. His constituency spanned from the Kalash tribe of Chitral, to Sikhs of Punjab to Baha’is of Thatta and Zoroastrians of Karachi. As a member of parliament, he helped overturn the law of teaching in Urdu in Parsi schools which was passed in the Zia-ul-Haq’s era to prevent the exodus of Zoroastrians from Pakistan. “My father tried to ensure every Zoroastrian, especially the newly weds, had a roof over their heads to build their family. He organised a health scheme with other Zoroastrian trusts, so that all members of our community are taken care of with hospitalisation. It’s an ageing population with 75% being over 70 years of age, that’s when the most medical complications take place.”

We can only help but wonder how Byram must have felt near the end of his life, watching the vibrant community he had grown up in look elsewhere for home. His life was spent building not just a business empire but also a community that was lucky enough to count a man of his stature among them. Within the community, he was a natural leader. When his father Dinshaw passed away in 1988, he was the social head of the Parsi community of Karachi. Byram succeeded him in this role and was unanimously elected chairman of the Karachi Parsi Anjuman Trust Fund (KPATF).

Yet the country Byram leaves behind is one in a shambles. Pakistan’s Human Development Index (HDI) value for 2021 is 0.544 - which puts the country in the Low human development category - positioning it at 161 out of 191 countries and territories. Between 1990 and 2021, Pakistan’s HDI value changed from 0.400 to 0.544, a change of 36.0%. The great irony of this, of course, is the fact that this index on which Pakistan finds itself slipping fast was in fact developed by a Pakistani — Dr Mahbub ul Haq, who created HDI in 1990. The index was then used to measure the development of countries by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP). Meanwhile, the Gender Development Index (GDI), which measures gender gaps in achievements in three basic dimensions of human development: Health, education, and standard of living, shows a massive gap. The 2021 female HDI value for Pakistan is 0.471 in contrast with 0.582 for males, resulting in a GDI value of 0.810, placing it into Group 5, making it part of an unenviable group of countries that includes Ethiopia, South Sudan, and Afghanistan. Meanwhile on the Gender

Inequality Index, Pakistan ranks 135 out of 170 countries.

In 2021, the World Justice Project’s Rule of Law Index ranked Pakistan 130 out of 139 countries. Pakistan ranked second-last in South Asian countries behind the likes of Nepal, Sri Lanka, India, and Bangladesh. Only Afghanistan was ranked lower. In particular, the report showed Pakistan doing badly in the areas of corruption, fundamental rights, order and security and regulatory enforcement.

This does raise the question, what does Pakistan have to offer? Democracy has failed to take root, more than half of the country was lost in 1971, social turmoil, a bad relationship with debt, a boom-and-bust economy, and a tired political system have all been part of the package. Men like Byram believed in Pakistan. They lived their lives here, grounded their business in Pakistan and embodied it as their home. And they witnessed it fail.

There were many men and women that fit this bill. Most of them will not be remembered in the history books or eulogised in newspapers and magazines. But all of them tried their best, only for the results to be painfully disappointing.

Byram’s life has come to an end. In his time he wore many hats and wore them all with poise, dignity, grace and distinction. He was a true Parsi gentleman of Karachi, and Pakistan is poorer for having lost him. As the Jamsheed Markers, Ardeshir Cowasjee, and Byram Avaris of Pakistan go the way of their maker, the question is, will we see more of them? Already the Parsi community has dwindled down to a shadow of its former self. Anyone with talent and opportunity in Pakistan is running for the hills. One can only hope for more such dedicated Pakistanis to come. n

As the Avari family grieves the loss of their illustrious patriarch, it is worth looking back at his life and taking stock. On the one hand, he was a famed business personality that grew and moulded his father’s legacy. On the other hand, he was perhaps one of the last men and women that represent a Pakistan that could have been — a generation that more than anything embodies and personifies a lost opportunityBristol Hotel Karachi - the first hotel owned by the Avari family

Nestled in an alternate reality of appreciation, pegged to the hopes of going below the 200-rupee mark against the dollar, not even the rupee knew what was about to hit it on the morning of January 23. The State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) had come to office and had casually decided to send a team to conduct mystery shopping at the exchange company outlets.

Now why did the SBP feel the need to do so? Maybe a little bird told the bank that the companies were not being diligent. Ever since the dollar was under a peg, some of the exchange companies’ outlets had indulged in malpractice of hoarding and shorting of the dollar. After having placed a cap on the price of the dollars, some of these outlets were not only refusing to sell at said price, but were also selling it at a 20-30 rupee surcharge. The excess profit was of course, off the books. Let’s first understand how this situation was made possible. And how did this lead to a 12% depre-

ciation within two days.

The fact that there was the opportunity for an arbitrage left in the dollar market leaves many confused. To understand that we need to understand the exchange rate. It is now an open secret that the SBP exchange rate was understated as compared to the market value. In a meeting

with the CEOs and exchange company heads, on October 30, 2022, Finance Minister Ishaq Dar assured the media that the price of the dollar against the rupee would be brought below the 200-rupee mark.

The meeting was held at the SBP. The representatives who attended that meeting were specifically reported for stating that the FM was “soft on the exchange companies”. Anyhow, ever since that meeting, these companies have followed a dollar-cap. This cap essentially means that the dollar would stay in a close vicinity of the interbank exchange rate. However, talking to Profit on January 24, Chairman Exchange Companies Association of Pakistan (ECAP), Malik Bostan stated that the government or the SBP did not set the rate

for exchange companies; the ECAP decided to put a dollar cap on its own accord.

As a result of this cap, there are three prices for the dollar in the market. The SBP’s interbank exchange rate, the exchange companies’ rate (the open market rate) and the actual market rate, which in these particular circumstances is also called the “black market rate” – because the actual market rate, at this point, became open to guesses. The interbank rate hovered around 220-230 rupees/USD. The exchange companies were buying and (hardly) selling within 10 rupees of the interbank rate.

As per the publishing editor of Profit and a senior analyst, Babar Nizami’s calculations, the real market rate of the dollar was at the 250 mark by the end of December. These calculations are based on the rupee’s value against any other un-pegged, free floating currency (in this case the GBP), and reconciling that value in dollars with that currency’s own exchange rate against the dollar. Right now, this method yields the rate of the US dollar close to 260 PKR, considering the GBP was traded upwards of 320 at the market’s closing on Friday.

In the background, the country’s foreign reserves were depleting on a linear basis and the SBP, through its “administrative measures” was controlling the provision of dollars to banks and importers. Not only does this provide all the sellers a perfect reason for not selling dollars but it also creates higher demand in the market.

This higher demand is not just because of the transaction demand. The dollar now becomes a store of value, making it, as former finance minister Miftah Ismail calls it, “a one way bet”. Anticipating a sure-shot depreciation of the rupee, people start to buy dollars and much like the former example, “dealers” erupt in every nook and cranny, looking to make pennies on the dollar. This increases the demand incrementally, creating ample room for the practice of Hawala and Hundi, which the state has no control over. This went on for a few months, remittances fell, export proceeds failed to make it back to the country in the quantity that they should have but the peg on the currency prevailed. Up until January 23.

On the morning of the 23rd, a team of the SBP caught 11 outlets of eight exchange companies for hoarding dollars. Mystery shopping is essentially a covert mission in which SBP officials dressed as common citizens go to these outlets and ask for dollars after ensuring they have dollars. If they still refuse to sell, the outlets are found guilty of hoarding.

The very next day, the ECAP announced

that they would remove the dollar cap. The step was taken in the greater interest of the country, as has always been the foremost business priority of exchange companies. The Secretary ECAP, Zafar Paracha told Profit that it was a mere coincidence that the decision to take off the dollar cap was announced after the closing down of branches. After announcing this the ECAP had to meet the SBP deputy governor, in the morning.

The next day, however, the exchange companies after removing the cap for a couple of hours, went back to trading at the capped rate. The only variable that changed within the two hours was the meeting with the deputy governor, however, upon enquiry, Paracha said that the subject of dollar-cap was not even discussed in the meeting. The magnitude of this claim is remarkable considering the circumstances under which the meeting was called. Hence, the ECAP episode could only be construed as a retaliation against the SBP. But what followed the next morning, surprised the entire country including the ECAP.

Within hours of trade on Thursday, the dollar rate touched its all time high at 255. Come Friday the rate went up to 262, marking the highest ever devaluation in the last two decades in two consecutive sessions. The day also marked the announcement of Pakistan’s lowest ever reserves in the last nine years. At $ 3.67 billion and debt repayments in front, Pakistan did what it should have done a long time ago. The announcement was ever so quickly followed by the IMF’s confirmation of sending their team to Pakistan for talks on the 9th review of the IMF EFF.

The SBP had done what it had held off from doing for the last three months. Ripped off the Dar-peg band aid, but only when push came to shove. And Dar’s entire reason for taking over the finance ministry from Ismail, collapsed in front of the nation.

Dar still has in front of him, however, the process of negotiations once the IMF team arrives. A job that he has a 25-year experience in, according to him. It’s time for the country to see how stern is his eye contact, which is, yet again, another one of his specialties while negotiating with the IMF.

As of now, the news is that the dollar is trading close to 269 in the open market. Most analysts think this will quench Pakistan’s long standing thirst for forex inflows, in remittances, export proceeds or otherwise. However, circumspect investors as Pakistanis are, the number of sellers in the market are yet to cross the number of buyers. n

The sovereign remains the biggest borrower in the country, making up more than 70 percent of all banking assets, either borrowing directly, or througg state-owned entities. As the state continues to run perpetual budget deficits, borrowing requirements continue to increase. Higher borrowing requirements generally means a greater demand of funds, and that leads to a higher interest rate, since the available of supply of funds has gradually moved outside the formal financial system. Currency in Circulation as a % of GDP remains close to it's all time high of 20 percent. As funds continue to stay outside the system, fueling a parallel economy, available of loanable funds within the system remains constrained, resulting in high interest rates.

When a depositor places money in a bank, a significant chunk of that is inadvertently lent out to the sovereign. The bank essentially makes a healthy profit by just being an arbitrator, or a conduit between depositors, and the sovereign. The bank isn't really taking any private sector credit risk, other than sovereign risk. This effectively keeps the return that depositors can get on their deposits suppressed, as banks carve out a substantial spread just to act as a conduit, rather than covering for any risk.

The holdings of sovereign borrowing instruments is also fairly narrow, as they are mostly held by banks, mutual funds, pension funds, insurance companies, and a handful of other institutions. As the base remains narrow, there exists a potential for collusion that can drive up interest rates without active market participation, either due to regulatory constraints, or other barriers to entry.

There exists a case for the sovereign to directly reach out to the population, and provide access to subscribe to sovereign debt with no barriers to entry. This will also enable the population to

get access to the risk free rate, rather than being made to pay high interest rate spreads to banks for holding their savings.

The technology required to accomplish the same already exists. The identity stack available with NADRA essentially has biometric data of all citizens with an identity card. Similarly, with more than 100 million mobile subscribers, it is entirely possible to make all of them savers in debt issues by the government while completely bypassing legacy financial institutions. Leveraging the capability of Raast, which is still being evolved by the Central Bank, it is possible for individuals to save in government issued debt instruments through even a text message, as Raast enables connectivity of a mobile number with a bank account, closing the loop, and ensuring greater financial inclusion

Enabling savings through such a mechanism can ensure that financial inclusions increases, in addition to increase in savings rates, and a potential reduction in currency in circulation. It may be noted here that Pakistan has one of the lowest savings rates in the world, which eventually leads to lower level of investments, higher interest rates, and non-availability of long-term capital that can be redeployed towards long-tailed infrastructure projects, or other projects of economic significance.

In order to prop up financial inclusion, it is also critical that radh mobile phone number that is biometrically verified automatically becomes an account number that can be linked to any bank. Using the same account number, the citizen should also have an option to subscribe to government issued debt instruments through a simple and intuitive interface. Currently, the process of investment in government issued debt instruments is extremely difficult, and definitely not intuitive. As banks are mostly responsible for enabling access to the same, they discourage existing and potential customers as that cannibalizes their existing income streams. It is time for the government to embrace technology and rollout issuance of debt thlo the public through utilization of existing technology infrastructure. This will not only enable penetration of financial instruments among the masses, but also make them savers without having to go through the cumbersome, and often bureaucratic route if a bank. There is an opportunity to rethink the way people save, and the way government borrows, and the same has never been easier given presence of payment and identity rails.

By Momina Ashraf

By Momina Ashraf

On January 11, 2023, a headline made it to the major news publications of Pakistan: Funds meant for low-income students ended up being used to purchase memberships for the elite Islamabad Club.

Two executive members of the National Endowment Scholarship for Talent (NEST) are dismissed for splurging at least Rs 25 million on the club’s membership. NEST is an autonomous programme for eligible and deserving students, headed by the Additional Secretary of the ministry of education.

According to a report by Dawn, in No-

vember 2021 the board of directors of NEST approved corporate membership in the club for the whole organisation and nominated the names of four top bureaucrats. The list included Athar Hussain Zaidi, Faysal Qasim, Qamar Safdar and Quratulain Talha; with monthly subscription charges to be paid by NEST.

Months later, the CFO forwarded this request to the then CEO Mohiyuddin Wani and the approval was granted accordingly. Mr Wani was later posted to Gilgit-Baltistan as the chief secretary. However, Wani’s successor Asim Iqbal, released the amount to Islamabad Club before being posted to Cabinet Division as Additional Secretary. This incident did not occur in isola-

tion. Time and again, senior bureaucrats land themselves in hot waters for similar reasons. Last year in May 2022, Irrigation Secretary Sohail Qureshi and former chief secretary Mumtaz Shah were charged for contempt of court related to non-payment of dues to private companies in a contract with the irrigation department.

Similarly, in November 2022, National Accountability Bureau (NAB) opened an embezzlement case of Rs 2 billion in the M-6 project against Deputy Commissioner (DC) Naushahro Feroze, Tashfeen Alam. However, Alam had flown out of Pakistan just a couple days earlier.

Postings, a long chain of hierarchy, access to easy international travel with a dash

Sweeping the dirt of financial discrepancies under the carpet of red tape is a money-making scheme as old as the bureaucracy itselfDr Mariam Chughtai, Director National Curriculum Council

of donor-funded projects is a quick recipe for fortune - or misfortune, on the few occasions that these high-flying bureaucrats are caught.

The problem does not even represent the tip of the iceberg. Bribes and corrupt practices in the bureaucracy of Pakistan is a widely discussed issue, a problem prevalent in other developing countries also. Pakistan lies abysmally low at 140 out of 180 in the Corruption Perception Index (CPI). The CPI countries and territories by their perceived levels of public sector corruption on a scale of zero (highly corrupt) to 100 (very clean). The CPI global average remains unchanged at 43.

To understand the root cause of the problem, Profit reached out to Ahsan Rana, a development professional, and an ex-civil servant, “Bureaucrats are part of the society. Because they hold so much discretion, it is easy for them to take up the opportunity and

make themselves rich. The system is complicated, with many layers of accountability such as the courts, NAB, Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI). This complicates the system, and ends up distorting the process of accountability,” said Rana. “First and foremost, government officials’ business and personal activities should not be classified information. There should be transparency in what they and their families do and transact on a daily basis,” he continued.

The education sector, particularly, falls vulnerable to corrupt practices. Since the 18th amendment the education sector has faced major administrative reforms also. “Previously the top officials were advisors, experts of the field.

But after the legislation, the education ministry has a joint secretary, deputy secretary who comes due to postings and lacks professional training in the particular field. Because they know they are going to be

shifted elsewhere within a couple of years, they are more likely to be involved in corrupt practices,” said a government official from the ministry of education, who wishes to stay anonymous.

In conversation with the same source, Profit learned that training such as National Management Course (NMC) and Middle-Management Class (MMC) does not involve financial management. This creates a lot of loopholes in auditing and a lot of times those officials get involved in embezzlement practices who don’t even know how and when their name was used. “The subordinates sign files due to the pressure from their seniors who get posted for a particular assignment. These people often get caught due to their lack of knowledge of the financial system. You know many times, a lot of government officials altogether avoid working on a new education project simply because they are afraid of what might catch them during the audit,” he explained.

The Auditor General of Pakistan (AGP), a government organisation that ensures public accountability and fiscal transparency reveals the discrepancies for district Rawalpindi’s education.

As shown in the chart, the biggest figure is in the irregularity related to employees. The AGP report explains, “officials were regularized but their pay was neither fixed on initial pay stage nor Social Security Benefit allowance was deducted. This resulted in overpayment of Rs10.155 million.”

Above is an example of the loopholes that usually occur in the payment of District Education Employees (DEA) employees since there is no set system of fixed pay for these officials.

In a conversation with Dr Mariam Chughtai, Director National

When international donor agencies send their funds, they also send a long list of conditions. For example, recently I signed a proposal to hire twenty consultants for a donor-funded project as per need. However, when the grant was released, the donor agencies pre-hired the twenty consultants who were not exactly experts in the relevant project. One of them was earning Rs 250,000 per day - the same amount which the highest paid government officer in my department earns in a month!Dr Ahsan Rana,

Curriculum Council (NCC), Profit learned that most of the time such irregularities are created by the junior level staff. In government offices, every payment invoice has to be signed by the department head. “Just recently the lock to our office door was broken. I received a document to sign the invoice of Rs 50,000 just for a new lock. You see now the staff members who generated that invoice, and those who circulated it to reach my desk were all aware of the financial discrepancy, no matter how big or small it is. But only I would be held responsible if I had signed it,” she said. Dr. Chughtai further elaborated that such discrepancies occur all the time in government offices, not just in the education sector. Given there’s not a proper transparent financial system, she has to take extra measures herself.

“There are three desks under me which are responsible for signing financial matters, so at least one of them catches the irregularity and contests the payments. I also keep the Ministry closely updated with relevant financial documents and processes to keep internal checks going. The Office of the Accountant General Pakistan Revenues (AGPR) thoroughly ensures that there is no financial discrepancy or missing documentation before payments are issued,” she elaborated.

NCC is although a fully government body under the ministry of education, it deals with private consultants and international donor agencies for some of their projects and

at LUMSis headed by a bureaucrat with experience in the field. This brings NCC under a somewhat different working culture than a typical government office, Dr. Chughtai confirmed. Therefore, the hiring is performance based and not on a permanent contract, which brings a sense of responsibility and accountability among the employees. “Even I can be fired if my performance is not up to the mark,” said Dr. Chughtai, who works as a bureaucrat under the Management Position Scale (MPS). In such a department, irregularities are not too often by the government-hired bureaucrats. But it deals with a multi-layered organisational structure. “Don’t be mistaken that financial discrepancies occur only in the government,” she remarked. “You know when international donor agencies send their funds, they also send a long list of conditions. For example, I work with many international development organisations. They can be truly helpful. But in another case, I was put in partnership with a donor agency which had committed to providing salaries for 20 experts as per the curriculum reforms project needs. However, when the grant was released, the donor agencies pre-hired the twenty consultants who were not exactly experts in the relevant project. One of them was earning Rs 250,000 per day - the same amount which the highest paid government officer in my department earns in a month!” she expressed, rather furiously. Upon asking about the criteria of

such hirings, she said there’s no transparency and no one knows who they will get to work with. These consultants will draw diagrams and deliver presentations, but are way too detached from the on-ground realities,” she continued.

Such a process slows down the project, doesn’t achieve the target and creates massive financial losses, Profit learned from the conversation.

This doesn’t end here. Although not always, many times these middle-persons are civil servants from the District Management Group (DMG) who take up the roles of advisors and consultants to lead and implement the donor-funded projects. Economist Dr Nadeem ul Haque, who has a vast experience of working as the IMF representative and deputy chairman of planning commission said that, “Donors come here for their foreign policy and lending needs. They don’t come here to help us. The donors recognise that everything goes through high-ranking civil servants so they cultivate them by giving scholarships, training abroad and long-term contracts which go on even after their retirement. Donors take very good care of government officials.”

It is not to say these heavy cheques are bribes, or any illegal means or earning. The position of bureaucracy puts certain cadres within the bureaucracy in positions of influence and power, which makes it possible for them to earn a lot more than what is set by the government salary.

Such selections, and projects, create inequality in a system which is theoretically linear and meant to serve the people with a set career paths and increment. “It’s not a justification, but when government officials see their batchmates earning a lot more because of being in different cadres and offices, it creates resentment and convinces them to go for institutionalised means,” said the source from the education ministry. n

“The subordinates sign files due to the pressure from their seniors who get posted for a particular assignment. These people often get caught due to their lack of knowledge of the financial system. You know many times, a lot of government officials altogether avoid working on a new education project simply because they are afraid of what might catch them during the audit,”

A member from the ministry of education, who wishes to stay anonymous

First and foremost, government officials’ business and personal activities should not be classified information. There should be transparency in what they and their families do and transact on a daily basis

former bureaucrat and professor

By Bakht Noor

By Bakht Noor

In Pakistan it is a common practice to self-diagnose and self-prescribe medicines, including antibiotics, for minor health problems like cold and flu. It’s quick and convenient. But it’s not inconsequential.

The overconsumption and misuse of antibiotics is leading to antibiotic resistance in humans and animals, posing a threat of food security, public health and development. Diseases related to bacterial infections such as tuberculosis, pneumonia and gonorrhoea are becoming harder to treat, as the antibiotics required to treat them have become less effective. Antibiotic resistance therefore leads to prolonged hospital stays, exorbitant medical costs and high mortality rate.

This, in turn, leads to a population that is unhealthy and cannot be helped with conventional medicines. The resultant effects on productivity and public health management could possibly be dire. So what is Pakistan doing to counter this fast creeping problem?

Very simply antibiotics are “medicines used to prevent and treat bacterial infections and antibiotic resistance occurs when bacteria change in response to the use of these medicines,” as defined by the World Health Organisation (WHO).

To understand the concept further, Profit reached out to Dr. Faisal Sultan, the former special assistant to Imran Khan for National Health Services. He said “a basic understanding of biology tells us that each time an organism such as a bacterium multiplies, it has the possibility of creating a mutation that may offer resistance against a chemical, such as an antibiotic in this case.”

Therefore, the development of antibiotic resistance is inevitable to a certain extent. “As there are virtually an uncountable number of bacteria, each time they divide and reproduce, they may end up having mutations that can provide possible resistance against antibiotics and enable them to survive. In fact, studies indicate that even bacteria that have never been exposed to human interaction or modern antibiotics can still contain resistance genes against modern antibiotics,” Dr. Sultan explained.

That being said, the reckless consumption of antibiotics has also massively aggravated the issue. Dr. Faisal Sultan adds, “the inappropriate and massive usage of antibiotics by humans and to a greater degree, animals has enormously contributed to the spread of antibiotic resistance.”

The bacteria, not humans or animals, becomes antibiotic resistant. This bacteria may infect humans and animals, and the resulting infections are difficult to treat compared to those caused by non-resistant bacteria. Consequently, patients face higher medical costs, excruciating hospital stays and risk of increased mortality.

This is not just a Pakistani problem. Antibiotic resistance is dangerously rising across the world. According to the WHO, “new resistance mechanisms are emerging and spreading globally, threatening our ability to treat common infectious diseases. A growing list of infections- such as pneumonia, tuberculosis, blood poisoning, gonorrhoea, and foodborne diseases- are becoming harder, and sometimes impossible, to treat as antibiotics become less effective.”

This problem is further pronounced in the developing world due to medical malpractice, such as the ubiquitous availability of antibiotics. According to Dr. Sultan, “in developing countries, the dispensing of antibiotics over the counter has created even more unnecessary usage and exposure. Many poultry and animal

industries use antibiotics and this then ends up in the food supply of humans, posing detrimental consequences for human health.”

Despite clear warning on the medicine’s packaging, antibiotics are readily sold over the counter without a doctor’s prescription. Additionally, without standard treatment guidelines, antibiotics are often overprescribed by veterinarians and health workers, leading to public overusage. Such consumer practices aggravate the emergence and spread of antibiotic resistant bacteria.

Dr. Nauman Ul Haq, a health economist, indicates various causes of the emergence and spread of antibiotic resistance. “Inappropriate prescription practices, inadequate patient education, limited diagnostic facilities, unauthorised sale of antimicrobials, a lack of appropriate functioning drug regulatory mechanisms, and non-human use of antimicrobials, such as in animal production, are some of the causes of high antibiotic resistance is developing countries.”

According to Dr. Faisal Sultan, “the most imminent threat of antibiotic resistance is the inability to combat diseases that are presently treatable. Modern medicine is contingent upon the efficacy and effectiveness of modern antibiotics. Several fields such as advanced surgery, neonatology, ICU care, cancer treatment and transplants are impossible to function without effective antibiotics. Estimates such that over a million people die directly due to infections caused by resistant organisms, and up to 5 million deaths result from indirect reasons.”

This inadvertently poses a global health crisis. “There are so many deaths directly attributable to the problem of antibiotic resistance. This is compounded by the fact that a very few

Global health is bracing for yet another crisis. This time it’s not a novel virus, but resistance against antibiotics. And countries like Pakistan are at the front-and-centre

new antibiotics are on the horizon.”

Though it’s a global problem, its effects are more acutely felt in the developing world. “Not only do we have greater resistance in certain kinds of bacteria, the access to modern antibiotics (especially the newest ones) is limited and they cost extremely high. This will have disastrous consequences. Many infections will become untreatable and people will die of previously treatable infections, as antibiotics from the past become increasingly ineffective,” Dr. Faisal Sultan details.

“Without urgent action, we are heading for a post-antibiotic era, in which common infections and minor injuries can once again kill,” warns the WHO.

This will inevitably wreak havoc for the local economy and public health management. “The cost of delivering healthcare especially in certain specialities will rise excessively, making it highly difficult to perform procedures such as cancer treatment, transplants, modern surgery, and so

on and so forth,” explains Dr Sultan. Similarly, Dr. Haq believes that “Antimicrobial resistance undoubtedly costs the health system more in terms of the number of patients to be treated per hour along with extended hospital stays. As resistant infections are more expensive to treat, the cost of health services are likely to be directly affected by antimicrobial resistance. Increased health expenditures may be felt in the cost of medicines, as more expensive antimicrobials are required, as well as more days spent in the hospital, more consultation time with providers, and increased demand for laboratory services.”

The World Bank models project a low burden of antimicrobial resistance could increase the global health costs by $330 billion; a high burden could increase health costs by $1.2 trillion.

Studies indicate that in the European Union alone, the additional burden of antibiotic resistance involves 25,000 deaths, 2.5 million hospital days and economic losses worth 1.5 billion euros, owing to the extra healthcare costs combined with decreased productivity.

Dr. Haq adds, “the growing demand for health-care services in developing countries puts additional strain on both public and private health-care spending, which, when combined with declining trade and livestock production, may result in a public deficit. Major chunk of health financing in low and middle income countries comes from out of pocket

(OOP) payments which are associated with catastrophic and impoverishing household spending.”

The impacts are particularly concerning in developing countries, where such economic costs can’t be sustained. A World Bank report suggests that in the context of high antibiotic resistance, an additional 24 million people will be plunged into dire poverty by 2030. Low-income countries will mostly face the brunt of this.

The WHO reports, “the world urgently needs to change the way it prescribes and uses antibiotics. Even if new medicines are developed, without behaviour change, antibiotic resistance will remain a major threat.” What is that behaviour change? Behaviour change means taking actions that reduce the spread of infections. This involves vaccination, handwashing and good food hygiene.

Apart from infection prevention and control, it’s also important to target the root cause of the problem, which is the overconsumption of antibiotics. There are measures that individuals, policy makers, healthcare professionals, healthcare industry and the agriculture sector can take to minimise antibiotic usage. “Both global and national efforts are required towards ensuring that the use of antimicrobials is appropriate and that there is what is called antimicrobial stewardship not only within hospitals and institutions but within the entire community,” says Dr Sultan.

“There is also the need to ensure that animal and veterinary use is properly regulated and the public understands the risks of the inappropriate use of using antibiotics for conditions that do not benefit from the use of antibiotics. This is a complicated topic and requires an in-depth approach which cuts across many sectors beyond just health. Pakistan has had a very comprehensive national action plan but as always it is the execution of the parts of the plan that is much more important than what is written on paper.”

“Inappropriate prescription practices, inadequate patient education, limited diagnostic facilities, unauthorised sale of antimicrobials, a lack of appropriate functioning drug regulatory mechanisms, and non-human use of antimicrobials, such as in animal production, are some of the causes of high antibiotic resistance is developing countries”

Dr Nauman ul Haq, health economist

“There are so many deaths directly attributable to the problem of antibiotic resistance. This is compounded by the fact that a very few new antibiotics are on the horizon”

Dr. Faisal Sultan, former special assistant to Imran Khan for National Health Services

By Luavut Zahid

By Luavut Zahid

Amidst a largely bleak period, a donor’s conference held in Geneva presented a rare bright spot for Pakistan where donors pledged close to $ 10 billion in funding over the next few years to help the country rebuild from devastating floods.

The funding is meant to not only just rebuild, but also to introduce climate resilient infrastructure and planning to mitigate such disasters in the future.

However, securing funding and using it effectively are two entirely different challenges. One such example, well before the catastrophic floods of 2022 across swathes of Pakistan, is the case of an internationally funded project that heralded new hope for the country’s largest city, Karachi.

In short, things have not panned out as they were meant to.

Back in 2020, when Pakistan was reeling from its first wave of Covid-19, the country’s largest city was hit by record rainfall that left most of the city underwater.

Karachi is no stranger to apocalyptic urban flooding. But the 2020 floods were something else – and injected new impetus into solving the city’s seemingly continuous flooding problems. A major problem was trash clogging the city’s nullahs – narrow channels that drain wastewater from the city to the sea.

Though it sounded simple enough, fixing this issue was going to be an expensive proposition in a country that spends most of its money on defence and debt. So when it was announced, the World Bank’s Solid Waste Emergency and Efficiency Project (Sweep) was seen as a lifeline that would help Karachi with its urban flooding nightmare.

The five-year project brought with it $ 100 million in funds, with the aim to “mitigate the impacts of flooding and COVID-19 emergencies, and to improve solid waste management services in Karachi.” Sweep was supposed to help solve the problem of trash clogging the nullahs, leading to stormwater

overflows, by improving solid waste management.

“In 2019, when the Sindh Government took the issue to the World Bank, we realised that there was a serious requirement to clean the nullahs once or twice a year,” Sweep director Zubair Channa, a Sindh government official, said.

After bad urban flooding in 2020, the Sindh government reached out to the World Bank to speed up the cleaning of nullahs. “We asked to be allowed to work and they agreed, so despite Sweep not having been signed yet work began, and we were to get the money back through retroactive funding,” Channa said.

The World Bank announced the decision to finance these efforts in December 2020, saying they would “improve solid waste management services in Karachi” and “upgrade critical solid waste infrastructure”. This would help to reduce floods “especially in vulnerable communities around drainage and waste collection sites.”

The reality on the ground was different.

Pakistan in 2023 secured billions in pledges to help recover from floods, but the case of a $100 million project from 2020 in Karachi is a stark reminder that a lot go wrong during execution

Two monsoon spells later, however, it seems the project has had little effect, with flooding upending the city in both 2021 and 2022. Two years into the project, there is no sign of progress and less than 3% of its $ 100-million budget has been spent – none of it on new infrastructure.

The people who were supposed to benefit from the efforts to stem urban flooding, and those who were most susceptible to its effects, have seen no benefits.

“We never know what kind of damage to expect when it rains,” said Razia Sunny, who lives by one of Karachi’s nullahs. “Residents here have gotten sick because of the waste flooding into our homes during urban flooding, we’ve even had people slip and fall [into the nullahs],” Imran Gill, another resident of the informal settlement, said.

One thing that did change for the millions of residents of slums along Karachi’s winding nullahs was that they came into the crosshairs of a Sindh government drive to clear settlements along the waterways. Provincial authorities took the promise of funding as a cue to demolish thousands of homes without, residents say, any consultation or plan to find them somewhere else to live.

For the purpose of this story, dozens

of official documents were reviewed, officials inside the projects were interviewed and sites affected by flooding were visited. In the sites near Karachi’s sewage infrastructure, there are several cases where residents of informal housing got injured or even died during extreme floods in 2020 and 2022.

When human rights organisations raised concerns about the demolitions, the World Bank distanced itself from the project. Government officials insist things are not going too badly. “We’re only delayed by three or four months,” Sweep director Channa said.

The World Bank seemingly agrees: Its project reports in March 2021 and November 2021 declared progress “satisfactory”, even though no work had been completed on the ground. This rating changed to “moderately satisfactory” for both the June 2022 and December 2022 reports, after further inaction.

In response to a request for comment, the World Bank defended the project and said the consultancy was “fairly advanced and expected to deliver their outputs soon”.

“Based on the current schedule, we expect the construction of the waste disposal facility and transfer stations to commence in early 2023,” said the bank’s press office.

This is a climate adaptation issue. Global heating “likely increased” the intensity of monsoon rains in 2022, when flooding hit 33 mil-

lion people across the country, an international group of scientists found. More extreme events are expected under a 2C warming scenario.

So what has happened to the promised funding? The money comes in the form of loans to the provincial government of Sindh.

Among a few feasibility studies and some operational costs, documents show the authorities have so far spent $ 91,891 (which at the time was converted to almost Rs 16 million) on furniture. An official source associated with Sweep, who asked not to be named, said the number was too high and seemed out of place.

“We’re a poor country; we can’t afford to spend like this on operational costs, not when that money will be paid back by citizens who already can’t afford it,” said architect and urban planner Dr Noman Ahmed, chairperson of Department of Architecture and Planning at the NED University Karachi.

The Sindh government’s procurement plan earmarks $ 8 million for equipment ranging from bins to waste collection vehicles. Another $ 30 million is destined for implementation “works”. This money has yet to be disbursed.

On all aspects of these expenses, bank oversight is meant to come once the project is

concluded. Yet related projects raise red flags. In November, the Sindh High Court barred the provincial government from awarding any more contracts under the World Bank’s Competitive and Liveable City of Karachi (Click) project, citing a lack of transparency over where the money was going.

Fahad Saeed, South Asia and Middle East lead at the policy NGO Climate Analytics, said: “Pakistan needs to do some introspection as to why they were unable to tap into the funds that were available. Was their own house in order to access these funds?”

In 2021, the world’s governments agreed at COP26 to double the amount of international adaptation finance by 2025, which stands at around $ 20 billion per year.

Instead of protecting the vulnerable, the provincial authorities started by bulldozing homes that had been built without planning permission. The World Bank denied responsibility. “There were meetings between civilians and WB officials, who claimed to us that they had never sanctioned any encroachment removal,” Zahid Farooq, senior manager at Karachi’s Urban Resource Centre, said.

The World Bank’s press office said their projects “will be prohibited from financing any future investments on the affected nullahs. Sweep will not retroactively or prospectively finance any nullah cleaning works, or any studies related to the nullahs.”

Then, in 2022, extreme flooding hit infor-

mal settlements the hardest, turning the water filled area around the nullahs into quicksand, according to resident Gill. “No one has ever died because of the nullahs before all this construction took place. And yet, the area has now seen several people lose their lives.”

Bhutta Masih died in flooding when the ground beneath his feet went out. He leaves behind five children and his widow, Parveen. His youngest son helped pull his father’s body out with ropes and has found it difficult to recover from the trauma. “He used to have a job but lost it. He hasn’t been okay mentally since that day. We can’t afford this,” Parveen said.

Owners of the broken homes are not permitted to rebuild what remains of their homes – even by hanging curtains. But some have nowhere else to go. Ruksana and Sadayat, a couple in their 80s who have lived most of their lives on the nullahs, used broken bricks they found to do some repair work. “We know they can break this down, but we have no other choice but to rebuild it. We can’t afford the rent [elsewhere], and when they come to tear it down, they will tear it down. What can we do?” Ruksana asked.

Despite all its troubles, Sweep director Channa said that Karachi’s flooding wasn’t as bad as previous years. Urban planning expert Ahmed said this was “completely untrue” and infrastructure under the World Bank’s Competitive and Livable City of Karachi

(Click) project had caused flooding to worsen. “They’ve done improvement projects, for example, the green belts, which themselves created bottlenecks,” he said. “It seems that this was nothing more than an emergency cleaning effort with no long-term thought process for solutions. When the WB is intervening with such a large portfolio, why aren’t they providing a plan to help the people who are being displaced?”

Lawyer and activist Abira Ashfaq has worked with the affected communities. She said the World Bank failed to use its influence on the Sindh government to help people living on the nullahs.

“We filed a complaint with the WB, and they deemed our case eligible. We held five meetings with WB officials and with the stakeholders,” she recalled. “Nevertheless, they distanced themselves and said their project was only meant to address waste disposal, and they eventually dismissed our complaints, claiming no responsibility,” she said.

The result of this interaction was that the nullah cleaning work was once again thrown back to the Sindh government, which has now handed it over to the Frontier Works Organization (FWO), the engineering wing of the Pakistan Army.

For now, residents can expect little more in the way of flood aid than tarpaulins from local NGOs to cover their damaged homes. They rely on each other and wait for the next flood. n A version of this article originally appeared in Climate Home News

Coming down harshly on finance minister Ishaq Dar, former finance minister Asad Umar has said that such a callous finance minister had caused rampant inflation only because of an absurd decision to delay getting into a loan program with the International Monetary Fund (IMF.)

“How incompetent is he,” said the former finance minister, speaking to reporters. “He nursed some weird delusions about being able to get the foreign exchange from

somewhere else, leading to a crisis, since we have to pay previous debt obligations and this has led to a serious balance of payments crisis.”

“Seriously, I think any finance minister that unnecessarily delays getting into an IMF program and messes it up for the rest of us, should be drawn and quartered.”

Former finance minister Asad Umar was then drawn and quartered.

The nation is currently under preparation for the upcoming default, it was duly informed on Monday.

The preparations have been underway for over a year, but efforts to acclimatise the nation for what lies ahead have intensified in recent weeks, it was further added.

“Yes, what you have been assuming for a while now, was never an assumption,” the nation was formally told on Monday.

“It has been coming for a while, and it is now about to happen. In this regard, we are now formally preparing you for default,” it was further added.

The official announcement came on Monday, as the day put an end to months-long speculation over whether or not the country was going to default.

The nation was further told that Monday was just the start, and the coming days will further reaffirm that we are collectively en route to default.

“But don’t you worry at all. The good thing is that you’ve been aware that this was going to happen for a long time. And now we’re preparing you for what lies ahead,” the nation was informed.

“Also, henceforth, make sure you always assume the worst,” it was added.

“That should be your default position.”