19 minute read

The paradox of Pakistan’s bureaucracy

vember 2021 the board of directors of NEST approved corporate membership in the club for the whole organisation and nominated the names of four top bureaucrats. The list included Athar Hussain Zaidi, Faysal Qasim, Qamar Safdar and Quratulain Talha; with monthly subscription charges to be paid by NEST.

Months later, the CFO forwarded this request to the then CEO Mohiyuddin Wani and the approval was granted accordingly. Mr Wani was later posted to Gilgit-Baltistan as the chief secretary. However, Wani’s successor Asim Iqbal, released the amount to Islamabad Club before being posted to Cabinet Division as Additional Secretary. This incident did not occur in isola- tion. Time and again, senior bureaucrats land themselves in hot waters for similar reasons. Last year in May 2022, Irrigation Secretary Sohail Qureshi and former chief secretary Mumtaz Shah were charged for contempt of court related to non-payment of dues to private companies in a contract with the irrigation department.

Advertisement

Similarly, in November 2022, National Accountability Bureau (NAB) opened an embezzlement case of Rs 2 billion in the M-6 project against Deputy Commissioner (DC) Naushahro Feroze, Tashfeen Alam. However, Alam had flown out of Pakistan just a couple days earlier.

Postings, a long chain of hierarchy, access to easy international travel with a dash

Dr Mariam Chughtai, Director National Curriculum Council

of donor-funded projects is a quick recipe for fortune - or misfortune, on the few occasions that these high-flying bureaucrats are caught.

A deep-rooted problem

The problem does not even represent the tip of the iceberg. Bribes and corrupt practices in the bureaucracy of Pakistan is a widely discussed issue, a problem prevalent in other developing countries also. Pakistan lies abysmally low at 140 out of 180 in the Corruption Perception Index (CPI). The CPI countries and territories by their perceived levels of public sector corruption on a scale of zero (highly corrupt) to 100 (very clean). The CPI global average remains unchanged at 43.

To understand the root cause of the problem, Profit reached out to Ahsan Rana, a development professional, and an ex-civil servant, “Bureaucrats are part of the society. Because they hold so much discretion, it is easy for them to take up the opportunity and make themselves rich. The system is complicated, with many layers of accountability such as the courts, NAB, Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI). This complicates the system, and ends up distorting the process of accountability,” said Rana. “First and foremost, government officials’ business and personal activities should not be classified information. There should be transparency in what they and their families do and transact on a daily basis,” he continued.

The education sector

The education sector, particularly, falls vulnerable to corrupt practices. Since the 18th amendment the education sector has faced major administrative reforms also. “Previously the top officials were advisors, experts of the field.

But after the legislation, the education ministry has a joint secretary, deputy secretary who comes due to postings and lacks professional training in the particular field. Because they know they are going to be shifted elsewhere within a couple of years, they are more likely to be involved in corrupt practices,” said a government official from the ministry of education, who wishes to stay anonymous.

In conversation with the same source, Profit learned that training such as National Management Course (NMC) and Middle-Management Class (MMC) does not involve financial management. This creates a lot of loopholes in auditing and a lot of times those officials get involved in embezzlement practices who don’t even know how and when their name was used. “The subordinates sign files due to the pressure from their seniors who get posted for a particular assignment. These people often get caught due to their lack of knowledge of the financial system. You know many times, a lot of government officials altogether avoid working on a new education project simply because they are afraid of what might catch them during the audit,” he explained.

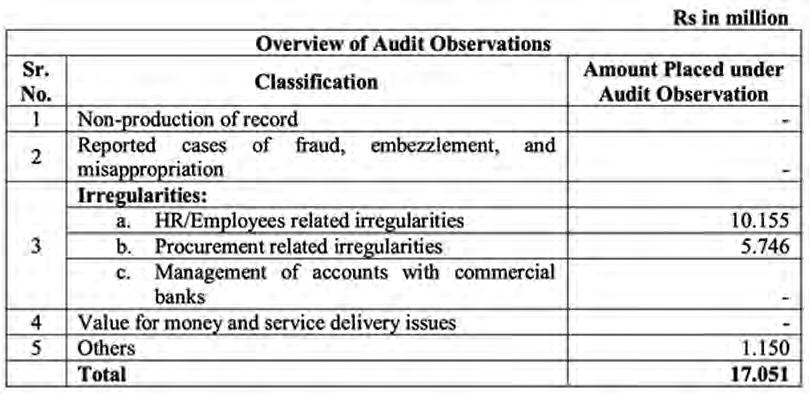

The Auditor General of Pakistan (AGP), a government organisation that ensures public accountability and fiscal transparency reveals the discrepancies for district Rawalpindi’s education.

As shown in the chart, the biggest figure is in the irregularity related to employees. The AGP report explains, “officials were regularized but their pay was neither fixed on initial pay stage nor Social Security Benefit allowance was deducted. This resulted in overpayment of Rs10.155 million.”

Above is an example of the loopholes that usually occur in the payment of District Education Employees (DEA) employees since there is no set system of fixed pay for these officials.

In a conversation with Dr Mariam Chughtai, Director National

Dr Ahsan Rana,

Curriculum Council (NCC), Profit learned that most of the time such irregularities are created by the junior level staff. In government offices, every payment invoice has to be signed by the department head. “Just recently the lock to our office door was broken. I received a document to sign the invoice of Rs 50,000 just for a new lock. You see now the staff members who generated that invoice, and those who circulated it to reach my desk were all aware of the financial discrepancy, no matter how big or small it is. But only I would be held responsible if I had signed it,” she said. Dr. Chughtai further elaborated that such discrepancies occur all the time in government offices, not just in the education sector. Given there’s not a proper transparent financial system, she has to take extra measures herself.

“There are three desks under me which are responsible for signing financial matters, so at least one of them catches the irregularity and contests the payments. I also keep the Ministry closely updated with relevant financial documents and processes to keep internal checks going. The Office of the Accountant General Pakistan Revenues (AGPR) thoroughly ensures that there is no financial discrepancy or missing documentation before payments are issued,” she elaborated.

NCC is although a fully government body under the ministry of education, it deals with private consultants and international donor agencies for some of their projects and

at LUMS

is headed by a bureaucrat with experience in the field. This brings NCC under a somewhat different working culture than a typical government office, Dr. Chughtai confirmed. Therefore, the hiring is performance based and not on a permanent contract, which brings a sense of responsibility and accountability among the employees. “Even I can be fired if my performance is not up to the mark,” said Dr. Chughtai, who works as a bureaucrat under the Management Position Scale (MPS). In such a department, irregularities are not too often by the government-hired bureaucrats. But it deals with a multi-layered organisational structure. “Don’t be mistaken that financial discrepancies occur only in the government,” she remarked. “You know when international donor agencies send their funds, they also send a long list of conditions. For example, I work with many international development organisations. They can be truly helpful. But in another case, I was put in partnership with a donor agency which had committed to providing salaries for 20 experts as per the curriculum reforms project needs. However, when the grant was released, the donor agencies pre-hired the twenty consultants who were not exactly experts in the relevant project. One of them was earning Rs 250,000 per day - the same amount which the highest paid government officer in my department earns in a month!” she expressed, rather furiously. Upon asking about the criteria of such hirings, she said there’s no transparency and no one knows who they will get to work with. These consultants will draw diagrams and deliver presentations, but are way too detached from the on-ground realities,” she continued.

Such a process slows down the project, doesn’t achieve the target and creates massive financial losses, Profit learned from the conversation.

Systemic inequality

This doesn’t end here. Although not always, many times these middle-persons are civil servants from the District Management Group (DMG) who take up the roles of advisors and consultants to lead and implement the donor-funded projects. Economist Dr Nadeem ul Haque, who has a vast experience of working as the IMF representative and deputy chairman of planning commission said that, “Donors come here for their foreign policy and lending needs. They don’t come here to help us. The donors recognise that everything goes through high-ranking civil servants so they cultivate them by giving scholarships, training abroad and long-term contracts which go on even after their retirement. Donors take very good care of government officials.”

It is not to say these heavy cheques are bribes, or any illegal means or earning. The position of bureaucracy puts certain cadres within the bureaucracy in positions of influence and power, which makes it possible for them to earn a lot more than what is set by the government salary.

Such selections, and projects, create inequality in a system which is theoretically linear and meant to serve the people with a set career paths and increment. “It’s not a justification, but when government officials see their batchmates earning a lot more because of being in different cadres and offices, it creates resentment and convinces them to go for institutionalised means,” said the source from the education ministry. n

By Bakht Noor

In Pakistan it is a common practice to self-diagnose and self-prescribe medicines, including antibiotics, for minor health problems like cold and flu. It’s quick and convenient. But it’s not inconsequential.

The overconsumption and misuse of antibiotics is leading to antibiotic resistance in humans and animals, posing a threat of food security, public health and development. Diseases related to bacterial infections such as tuberculosis, pneumonia and gonorrhoea are becoming harder to treat, as the antibiotics required to treat them have become less effective. Antibiotic resistance therefore leads to prolonged hospital stays, exorbitant medical costs and high mortality rate.

This, in turn, leads to a population that is unhealthy and cannot be helped with conventional medicines. The resultant effects on productivity and public health management could possibly be dire. So what is Pakistan doing to counter this fast creeping problem?

Antibiotics and antibiotic resistance

Very simply antibiotics are “medicines used to prevent and treat bacterial infections and antibiotic resistance occurs when bacteria change in response to the use of these medicines,” as defined by the World Health Organisation (WHO).

To understand the concept further, Profit reached out to Dr. Faisal Sultan, the former special assistant to Imran Khan for National Health Services. He said “a basic understanding of biology tells us that each time an organism such as a bacterium multiplies, it has the possibility of creating a mutation that may offer resistance against a chemical, such as an antibiotic in this case.”

Therefore, the development of antibiotic resistance is inevitable to a certain extent. “As there are virtually an uncountable number of bacteria, each time they divide and reproduce, they may end up having mutations that can provide possible resistance against antibiotics and enable them to survive. In fact, studies indicate that even bacteria that have never been exposed to human interaction or modern antibiotics can still contain resistance genes against modern antibiotics,” Dr. Sultan explained.

That being said, the reckless consumption of antibiotics has also massively aggravated the issue. Dr. Faisal Sultan adds, “the inappropriate and massive usage of antibiotics by humans and to a greater degree, animals has enormously contributed to the spread of antibiotic resistance.”

The bacteria, not humans or animals, becomes antibiotic resistant. This bacteria may infect humans and animals, and the resulting infections are difficult to treat compared to those caused by non-resistant bacteria. Consequently, patients face higher medical costs, excruciating hospital stays and risk of increased mortality.

Scope of the problem

This is not just a Pakistani problem. Antibiotic resistance is dangerously rising across the world. According to the WHO, “new resistance mechanisms are emerging and spreading globally, threatening our ability to treat common infectious diseases. A growing list of infections- such as pneumonia, tuberculosis, blood poisoning, gonorrhoea, and foodborne diseases- are becoming harder, and sometimes impossible, to treat as antibiotics become less effective.”

This problem is further pronounced in the developing world due to medical malpractice, such as the ubiquitous availability of antibiotics. According to Dr. Sultan, “in developing countries, the dispensing of antibiotics over the counter has created even more unnecessary usage and exposure. Many poultry and animal industries use antibiotics and this then ends up in the food supply of humans, posing detrimental consequences for human health.”

Despite clear warning on the medicine’s packaging, antibiotics are readily sold over the counter without a doctor’s prescription. Additionally, without standard treatment guidelines, antibiotics are often overprescribed by veterinarians and health workers, leading to public overusage. Such consumer practices aggravate the emergence and spread of antibiotic resistant bacteria.

Dr. Nauman Ul Haq, a health economist, indicates various causes of the emergence and spread of antibiotic resistance. “Inappropriate prescription practices, inadequate patient education, limited diagnostic facilities, unauthorised sale of antimicrobials, a lack of appropriate functioning drug regulatory mechanisms, and non-human use of antimicrobials, such as in animal production, are some of the causes of high antibiotic resistance is developing countries.”

What are the dangers of antibiotic resistance?

According to Dr. Faisal Sultan, “the most imminent threat of antibiotic resistance is the inability to combat diseases that are presently treatable. Modern medicine is contingent upon the efficacy and effectiveness of modern antibiotics. Several fields such as advanced surgery, neonatology, ICU care, cancer treatment and transplants are impossible to function without effective antibiotics. Estimates such that over a million people die directly due to infections caused by resistant organisms, and up to 5 million deaths result from indirect reasons.”

This inadvertently poses a global health crisis. “There are so many deaths directly attributable to the problem of antibiotic resistance. This is compounded by the fact that a very few new antibiotics are on the horizon.”

Though it’s a global problem, its effects are more acutely felt in the developing world. “Not only do we have greater resistance in certain kinds of bacteria, the access to modern antibiotics (especially the newest ones) is limited and they cost extremely high. This will have disastrous consequences. Many infections will become untreatable and people will die of previously treatable infections, as antibiotics from the past become increasingly ineffective,” Dr. Faisal Sultan details.

“Without urgent action, we are heading for a post-antibiotic era, in which common infections and minor injuries can once again kill,” warns the WHO.

Effects on the local economy and public health management

This will inevitably wreak havoc for the local economy and public health management. “The cost of delivering healthcare especially in certain specialities will rise excessively, making it highly difficult to perform procedures such as cancer treatment, transplants, modern surgery, and so on and so forth,” explains Dr Sultan. Similarly, Dr. Haq believes that “Antimicrobial resistance undoubtedly costs the health system more in terms of the number of patients to be treated per hour along with extended hospital stays. As resistant infections are more expensive to treat, the cost of health services are likely to be directly affected by antimicrobial resistance. Increased health expenditures may be felt in the cost of medicines, as more expensive antimicrobials are required, as well as more days spent in the hospital, more consultation time with providers, and increased demand for laboratory services.”

The World Bank models project a low burden of antimicrobial resistance could increase the global health costs by $330 billion; a high burden could increase health costs by $1.2 trillion.

Studies indicate that in the European Union alone, the additional burden of antibiotic resistance involves 25,000 deaths, 2.5 million hospital days and economic losses worth 1.5 billion euros, owing to the extra healthcare costs combined with decreased productivity.

Dr. Haq adds, “the growing demand for health-care services in developing countries puts additional strain on both public and private health-care spending, which, when combined with declining trade and livestock production, may result in a public deficit. Major chunk of health financing in low and middle income countries comes from out of pocket

(OOP) payments which are associated with catastrophic and impoverishing household spending.”

The impacts are particularly concerning in developing countries, where such economic costs can’t be sustained. A World Bank report suggests that in the context of high antibiotic resistance, an additional 24 million people will be plunged into dire poverty by 2030. Low-income countries will mostly face the brunt of this.

What can be done?

The WHO reports, “the world urgently needs to change the way it prescribes and uses antibiotics. Even if new medicines are developed, without behaviour change, antibiotic resistance will remain a major threat.” What is that behaviour change? Behaviour change means taking actions that reduce the spread of infections. This involves vaccination, handwashing and good food hygiene.

Apart from infection prevention and control, it’s also important to target the root cause of the problem, which is the overconsumption of antibiotics. There are measures that individuals, policy makers, healthcare professionals, healthcare industry and the agriculture sector can take to minimise antibiotic usage. “Both global and national efforts are required towards ensuring that the use of antimicrobials is appropriate and that there is what is called antimicrobial stewardship not only within hospitals and institutions but within the entire community,” says Dr Sultan.

“There is also the need to ensure that animal and veterinary use is properly regulated and the public understands the risks of the inappropriate use of using antibiotics for conditions that do not benefit from the use of antibiotics. This is a complicated topic and requires an in-depth approach which cuts across many sectors beyond just health. Pakistan has had a very comprehensive national action plan but as always it is the execution of the parts of the plan that is much more important than what is written on paper.”

By Luavut Zahid

Amidst a largely bleak period, a donor’s conference held in Geneva presented a rare bright spot for Pakistan where donors pledged close to $ 10 billion in funding over the next few years to help the country rebuild from devastating floods.

The funding is meant to not only just rebuild, but also to introduce climate resilient infrastructure and planning to mitigate such disasters in the future.

However, securing funding and using it effectively are two entirely different challenges. One such example, well before the catastrophic floods of 2022 across swathes of Pakistan, is the case of an internationally funded project that heralded new hope for the country’s largest city, Karachi.

In short, things have not panned out as they were meant to.

Back in 2020, when Pakistan was reeling from its first wave of Covid-19, the country’s largest city was hit by record rainfall that left most of the city underwater.

Climate Change

‘Saving’ Karachi

Karachi is no stranger to apocalyptic urban flooding. But the 2020 floods were something else – and injected new impetus into solving the city’s seemingly continuous flooding problems. A major problem was trash clogging the city’s nullahs – narrow channels that drain wastewater from the city to the sea.

Though it sounded simple enough, fixing this issue was going to be an expensive proposition in a country that spends most of its money on defence and debt. So when it was announced, the World Bank’s Solid Waste Emergency and Efficiency Project (Sweep) was seen as a lifeline that would help Karachi with its urban flooding nightmare.

The five-year project brought with it $ 100 million in funds, with the aim to “mitigate the impacts of flooding and COVID-19 emergencies, and to improve solid waste management services in Karachi.” Sweep was supposed to help solve the problem of trash clogging the nullahs, leading to stormwater overflows, by improving solid waste management.

“In 2019, when the Sindh Government took the issue to the World Bank, we realised that there was a serious requirement to clean the nullahs once or twice a year,” Sweep director Zubair Channa, a Sindh government official, said.

After bad urban flooding in 2020, the Sindh government reached out to the World Bank to speed up the cleaning of nullahs. “We asked to be allowed to work and they agreed, so despite Sweep not having been signed yet work began, and we were to get the money back through retroactive funding,” Channa said.

The World Bank announced the decision to finance these efforts in December 2020, saying they would “improve solid waste management services in Karachi” and “upgrade critical solid waste infrastructure”. This would help to reduce floods “especially in vulnerable communities around drainage and waste collection sites.”

The reality on the ground was different.

Ground realities

Two monsoon spells later, however, it seems the project has had little effect, with flooding upending the city in both 2021 and 2022. Two years into the project, there is no sign of progress and less than 3% of its $ 100-million budget has been spent – none of it on new infrastructure.

The people who were supposed to benefit from the efforts to stem urban flooding, and those who were most susceptible to its effects, have seen no benefits.

“We never know what kind of damage to expect when it rains,” said Razia Sunny, who lives by one of Karachi’s nullahs. “Residents here have gotten sick because of the waste flooding into our homes during urban flooding, we’ve even had people slip and fall [into the nullahs],” Imran Gill, another resident of the informal settlement, said.

One thing that did change for the millions of residents of slums along Karachi’s winding nullahs was that they came into the crosshairs of a Sindh government drive to clear settlements along the waterways. Provincial authorities took the promise of funding as a cue to demolish thousands of homes without, residents say, any consultation or plan to find them somewhere else to live.

For the purpose of this story, dozens of official documents were reviewed, officials inside the projects were interviewed and sites affected by flooding were visited. In the sites near Karachi’s sewage infrastructure, there are several cases where residents of informal housing got injured or even died during extreme floods in 2020 and 2022.

When human rights organisations raised concerns about the demolitions, the World Bank distanced itself from the project. Government officials insist things are not going too badly. “We’re only delayed by three or four months,” Sweep director Channa said.

The World Bank seemingly agrees: Its project reports in March 2021 and November 2021 declared progress “satisfactory”, even though no work had been completed on the ground. This rating changed to “moderately satisfactory” for both the June 2022 and December 2022 reports, after further inaction.

In response to a request for comment, the World Bank defended the project and said the consultancy was “fairly advanced and expected to deliver their outputs soon”.

“Based on the current schedule, we expect the construction of the waste disposal facility and transfer stations to commence in early 2023,” said the bank’s press office.

This is a climate adaptation issue. Global heating “likely increased” the intensity of monsoon rains in 2022, when flooding hit 33 mil- lion people across the country, an international group of scientists found. More extreme events are expected under a 2C warming scenario.

The money trail

So what has happened to the promised funding? The money comes in the form of loans to the provincial government of Sindh.

Among a few feasibility studies and some operational costs, documents show the authorities have so far spent $ 91,891 (which at the time was converted to almost Rs 16 million) on furniture. An official source associated with Sweep, who asked not to be named, said the number was too high and seemed out of place.

“We’re a poor country; we can’t afford to spend like this on operational costs, not when that money will be paid back by citizens who already can’t afford it,” said architect and urban planner Dr Noman Ahmed, chairperson of Department of Architecture and Planning at the NED University Karachi.

The Sindh government’s procurement plan earmarks $ 8 million for equipment ranging from bins to waste collection vehicles. Another $ 30 million is destined for implementation “works”. This money has yet to be disbursed.

On all aspects of these expenses, bank oversight is meant to come once the project is concluded. Yet related projects raise red flags. In November, the Sindh High Court barred the provincial government from awarding any more contracts under the World Bank’s Competitive and Liveable City of Karachi (Click) project, citing a lack of transparency over where the money was going.

Fahad Saeed, South Asia and Middle East lead at the policy NGO Climate Analytics, said: “Pakistan needs to do some introspection as to why they were unable to tap into the funds that were available. Was their own house in order to access these funds?”

In 2021, the world’s governments agreed at COP26 to double the amount of international adaptation finance by 2025, which stands at around $ 20 billion per year.

Destroyed homes

Instead of protecting the vulnerable, the provincial authorities started by bulldozing homes that had been built without planning permission. The World Bank denied responsibility. “There were meetings between civilians and WB officials, who claimed to us that they had never sanctioned any encroachment removal,” Zahid Farooq, senior manager at Karachi’s Urban Resource Centre, said.

The World Bank’s press office said their projects “will be prohibited from financing any future investments on the affected nullahs. Sweep will not retroactively or prospectively finance any nullah cleaning works, or any studies related to the nullahs.”

Then, in 2022, extreme flooding hit infor- mal settlements the hardest, turning the water filled area around the nullahs into quicksand, according to resident Gill. “No one has ever died because of the nullahs before all this construction took place. And yet, the area has now seen several people lose their lives.”

Bhutta Masih died in flooding when the ground beneath his feet went out. He leaves behind five children and his widow, Parveen. His youngest son helped pull his father’s body out with ropes and has found it difficult to recover from the trauma. “He used to have a job but lost it. He hasn’t been okay mentally since that day. We can’t afford this,” Parveen said.

Owners of the broken homes are not permitted to rebuild what remains of their homes – even by hanging curtains. But some have nowhere else to go. Ruksana and Sadayat, a couple in their 80s who have lived most of their lives on the nullahs, used broken bricks they found to do some repair work. “We know they can break this down, but we have no other choice but to rebuild it. We can’t afford the rent [elsewhere], and when they come to tear it down, they will tear it down. What can we do?” Ruksana asked.

Sweep’s future

Despite all its troubles, Sweep director Channa said that Karachi’s flooding wasn’t as bad as previous years. Urban planning expert Ahmed said this was “completely untrue” and infrastructure under the World Bank’s Competitive and Livable City of Karachi

(Click) project had caused flooding to worsen. “They’ve done improvement projects, for example, the green belts, which themselves created bottlenecks,” he said. “It seems that this was nothing more than an emergency cleaning effort with no long-term thought process for solutions. When the WB is intervening with such a large portfolio, why aren’t they providing a plan to help the people who are being displaced?”

Lawyer and activist Abira Ashfaq has worked with the affected communities. She said the World Bank failed to use its influence on the Sindh government to help people living on the nullahs.

“We filed a complaint with the WB, and they deemed our case eligible. We held five meetings with WB officials and with the stakeholders,” she recalled. “Nevertheless, they distanced themselves and said their project was only meant to address waste disposal, and they eventually dismissed our complaints, claiming no responsibility,” she said.

The result of this interaction was that the nullah cleaning work was once again thrown back to the Sindh government, which has now handed it over to the Frontier Works Organization (FWO), the engineering wing of the Pakistan Army.

For now, residents can expect little more in the way of flood aid than tarpaulins from local NGOs to cover their damaged homes. They rely on each other and wait for the next flood. n A version of this article originally appeared in Climate Home News