Major companies such as Lucky Cement, JDW Sugar Mills, Bank Alfalah, Maple Leaf Cement, and ENGRO have announced buy-backs of their shares

By Muhammad Raafay KhanIt started in May when NetSol Technologies Limited (NETSOL) announced it was going to buy back two million of its outstanding shares. This was followed shortly after by Maple Leaf Cement Limited (MLCF) which announced it would buy back 25 million shares. From here on out there was no looking back.

The rest of the year saw Lucky Cement (LUCK), JDW Sugar Mills (JDWS), Bank Alfalah (BAFL), and most recently ENGRO in December announcing that they were going to buy back their shares.

Since the change in the government in April 2022 this year, the KSE100, which measures the performance of the top 100 stocks in the Pakistan Stock Exchange (PSX), has been on a declining trend. Macroeconomic factors such as political and economic instability have generally made stock market investors wary of the business confidence in the country.

With a lack of buyers for companies’ shares in the PSX, many listed companies have seen their share prices decline significantly. Given that many companies have also faced a dent in their net profits, the Earnings Per Share (EPS) of the companies have also gone down. The EPS is a measure of the net profit earned by one outstanding share, a popular metric to measure the performance of a company for investors.

Declining EPS and affordable share prices have prompted many companies to do something to make their companies look attractive in the eyes of the investors. For some companies, this has come in the form of share buybacks.

However, it is not only the economic instability that has prompted the share buybacks but the relaxation in buyback rules for the listed companies as well. The big debate about buybacks is whether or not they are good for the company, the investors, and the stock market in general.

Before we try to understand what is happening in the stock market, it’s important to understand what exactly are buybacks.

When companies buy their own shares from the stock market, that is a share buyback. Usually, we only see the corporate insiders such as the board of directors, their family members, or another associated company such as a subsidiary or a parent company, buying the shares of the company. But this is not a share buyback. This is only the occasional and sometimes frequent purchase of shares by corporate insiders.

However, if these purchases are taking place at a time of widespread share buybacks in the stock market, it takes renewed significance. The case of MCB is an example of this where the sponsors bought a 5.49% stake in their bank last month.

Share buybacks are different from trading

in the company’s shares by corporate insiders. For one thing, share buybacks are usually bigger than buybacks done by the insiders. Companies also have to fulfill a lot more legal requirements before engaging in buybacks. And while corporate insiders buy the shares from their own pocket money, when companies buy back their shares, they do it from the company’s cash (sometimes to the dismay of shareholders expecting dividends as will be discussed later).

The share buyback rules by listed companies on the stock market are written in the SECP Listed Companies (Buy-back of shares) Regulations 2019, which was most recently amended in September 2022.

In this part, we want to focus on three buyback regulations and compare how the rules of buybacks have changed over the years. This can also help us understand why so many big companies are engaging in share buybacks this year.

The three buyback rules are:

1. Listed Companies (buy-back of shares) Regulations, 2016

2. Listed Companies (buy-back of shares) Regulations, 2019

3. Amendments to Listed Companies (buyback of shares) Regulations, 2019 (Updated September 2022)

The first buyback rules we will consider are the 2016 rules, followed by the 2019 rules, which were most recently amended in September 2022. The buyback rules being followed currently are the 2019 rules which were amended in September of this year.

The share buy-back rules can be compared across five factors: 1) eligibility, 2) purchase procedure, 3) purchase period, 4) purchase price (through tender or exchange), and 5) buy-back restrictions.

The eligibility criteria for the companies to engage in buybacks, according to the 2019 rules, has mostly stayed the same as the 2016 regulations. Companies should be listed for at least three years, they should have minimum paid-up capital requirements after the buyback of shares is completed, they should have adequate funds to cover the buyback, and there should be no legal cases against the company or ongoing merger/acquisitions being undertaken by the company before the buy-back.

One notable change, however, is that according to the 2016 regulations companies were required to wait at least three months since the last purchase was disapproved by the members before the board could recommend another purchase. The 2019 rules elongated the waiting period for announcing a buyback after it was disapproved the last time to six months from three months.

2. Purchase Procedure:

After the companies are eligible for share

buybacks, the BOD makes a recommendation for purchase/buy-backs. This then needs to be approved through a special resolution in the company’s extraordinary general meeting (EGM) of shareholders. This general meeting needs to be held in 45 days (previously 35 days in 2016 regulations) from the date of recommendation by the BOD.

After the special resolution is passed in the general meeting and approval is given for the buy-backs, the public announcement for buybacks needs to be made in two working days. This is followed by the start of the purchase period within seven days from the date of public announcement which goes on for 180 days. Lastly, the company is supposed to make a public report on buybacks, share it with SECP and also announce it to the PSX.

The share purchasing period runs for a period of 180 days from the day the approval is given in the general meeting or whatever date when the buyback is completed, whichever is earlier. Previously, the purchase duration was for 90 days in the 2019 regulations but this was changed in the September 2022 amendment.

4.

In 2016 and 2019, companies could determine the share price for buy-backs either through tender or the spot/current market price. In 2016, the purchase price through tender offer was the price recommended by the BoD and approved through special resolutions, but it could not be less than the weighted average price of the last 30 days of the share. In 2019, the tender offer price was made much easier as it was not less than the average of the preceding 5 days. A previous article by Profit in 2019 made the case against companies determining their share price on their own.

But after the September 2022 amendments, companies cannot recommend or set a price itself for the buybacks so the share price through the tender option is gone. Now, the companies can only purchase back their shares at the spot / current market price which can be considered as an improvement in the laws.

5.

In the 2016 and even in the 2019 regulations, the buyback rules prohibited companies

from voluntarily delisting or voluntary wind up within 12 months after the buyback period was completed. But in the latest amendments, this time period has been increased to 2 years, which can again be considered as an improvement.

In the 2016 regulations, the corporate insiders were not allowed to trade in the shares of the company from the date of recommendation by BOD till the COMMENCEMENT of the purchase period. But in 2019, this was made more stringent as corporate insiders were not allowed to trade in the shares of their own company from the date of recommendation by BOD until the end of the purchasing period. This is another positive amendment.

A second buyback can’t happen for a year until the report of its buyback is sent to commission, but if free float is above 25% then the company can do another buyback in the 1 year after.

The following two previous restrictions were also lifted for the companies: 1) the purchasing company shall deposit the consideration payable in the designated clearing bank account at least one day before the settlement date, 2) In case of purchase through securities exchange, report to the securities exchange the number of shares purchased on daily basis for public dissemination.

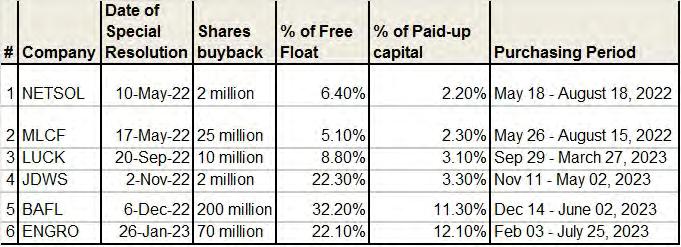

There have been six official buybacks (completed, ongoing, and announced) in the year. The table below shows the details of the buybacks announced by the six companies.

<Insert

All companies, with the exception of NETSOL, have said that they will cancel their shares after the buyback. The companies expect that these buybacks will eventually improve the EPS and dividends of the company.

We can also see from the table that the buybacks of NETSOL and MLCF are completed and were only there for a period of three months. This is because these buybacks happened before the September 2022 amendment to the buyback rules which increased the buyback purchasing period from three months to six months. For the remaining four compa-

nies, their buyback periods will go up till the second quarter of 2023.

Different metrics will indicate different companies as doing the biggest buyback. If we only consider the absolute value of the shares, then the biggest buy-back of the year is most probably going to be that of ENGRO with 70 million shares at an average price of 260 which comes down to approximately PKR 18.2 billion!

But perhaps what is more important to note than which buy-back is the biggest is to focus on the reasons behind these buy-backs and what they mean for not only the stock market in general but for the companies and investors in particular.

There is a big debate about whether or not buybacks are a good use of the company’s cash flow. Generally, when companies announce buybacks, they say that it will help improve the Earnings Per Share (EPS) of the company. Now, if EPS is considered as an important enough indicator in a market, the increase in EPS post-buyback can indicate that the stock is worth buying.

But where do the companies find the cash to fund such buybacks? They do it by using their free cash flow (FCF). The FCF is an excellent indicator signifying the actual cash available to the firm for distribution. It is calculated by subtracting the capital expenditures from the operating cash flow (which is the amount of actual cash earned by the company in a year). The FCF can then be used to either make capital investments, make other financial investments, or pay dividends to the shareholders.

More generally, as a previous Profit article explained, buy-backs are only one of the five ways that a company can utilize its free cash flow. The other four ways are:

1. Spending on capital expenditures

2. Buying other companies or investments

3. Saving it for a rainy day

4. Pay it out as dividends

Given that spending on capital expenditures or buying other companies are expansionary plans which can provide great returns in the future, the only reason these two options might not be a great idea at any time is if there are less investment opportunities available to the company. This might make the other three options more suitable for companies.

From the perspective of shareholders (especially minority shareholders), it is normally considered good if the company uses its excess cash to pay back high dividends to the shareholders for their investment in the company. In the case where the company does not have any investment opportunities available, paying high dividends to the existing shareholders can also generate increased public interest in the company. This can lead to more demand for the

company’s stock which can then increase the valuation of the company.

Ali Farid Khwaja, co-founder and chairman of Ktrade Securities, says, “Buyback means that companies don’t have any other opportunities to invest in, the return in buying back shares of a company rather than investing in its growth is more. Typically, if you’re going for growth, which means that the company want to raise money in the market and invest that in expanding the company. Buybacks are linked to maturity, because mature companies have little investment opportunities, so either their dividend will be high or they can use the cash to buyback. So the debate is if you have cash but don’t have investment opportunities, you can return the cash to investors.”

“Dividends are a better way of returning the cash so that the minority shareholders can decide themselves what to do with the cash. But when you buyback, you make the decision for minority shareholders too which might not be the minority shareholders want with that cash,” he continues.

“In Pakistan, buy-backs make sense from the company’s perspective because the economy is slowing down, companies don’t have investment opportunities and the valuations are cheap, they wouldn’t be buying back their shares if the valuations were high. But they’re also making a decision for the minority shareholders because they are not just using their own cash but also the cash of the minority shareholders to buy back the shares.”

In the short-term, it might not be good for minority shareholders if their companies are doing buybacks because they would prefer the dividends. But in the short-term, it offers a good deal to the companies who now have attractive valuations of their stocks. In the long-term, however, the decrease in outstanding shares after the buybacks can result in higher dividends for those shareholders who hold the company’s stocks because the supply of the company’s stock will decrease and company’s can give lesser total dividends while still giving a higher dividends per share.

Farooq Tirmizi, CEO of Elphinstone, also believes that buy-backs are not a good thing for the PSX in particular and for the country in general. “There should be no permission in the law for any buybacks. We are already in a situation where we have a miniscule free-float in Pakistani stocks, and the managements of large companies have clearly struggled to come up with ways to invest in their companies’ growth. Allowing for buybacks will both reduce the number of shares available for the general public to invest in, and it will incentivise CEOs to not come up with ways to expand the productive capacity of their companies - and by extension that of the country”, he says.

There is no doubt that in Pakistan the

majority of the listed companies have small free float and are mostly majority family-controlled businesses. Minority investors generally do not have a lot of say in the companies they have invested in (not that they should have too much voice because that can halt the everyday running of the businesses as well). Nevertheless, just because a company has a small free float and is majority controlled by families does not mean that the company does not take care of its minority investors. A healthy balance is necessary.

Generally, however, most companies which are engaging in buybacks believe that the share buybacks will help to raise the EPS of the company and the future dividends.

From the point of view of companies, the September 2022 amendments have made it easier for companies to buy back their own shares. As Mohammad Sohail, CEO of Topline Securities, says, “Recent changes in buy back rules are compelling for companies to buy their own stocks. Considering the attractive valuations, we think more companies will come to buy their own shares in the future.”

This suggests that the six buybacks so far in 2022 might not be the end of the buyback trend. We may see even more such buybacks in the near future, especially considering the political and economic instability in the country is expected to continue for a few more months.

022 has been the year of buybacks. The share prices of many profitable and established companies have taken a huge hit. This has made their valuations attractive in the eyes of investors. But due to a lack of institutional and foreign investors in the market, the sponsors of these companies have decided to take advantage of the decline in share prices and buy back their own companies’ shares.

The buybacks are being funded from the free cash flows of the company. These cash reserves can alternatively also be used by the company to pay back higher dividends or for more capital or financial investments. But given the lack of investment opportunities available in the country, the companies have decided to buy back their own shares. In the long-run, this move is expected to raise the share prices and EPS of the company. The relaxation in buyback rules after the September 2022 amendment have also made buybacks favorable to the listed companies.

With the ongoing political and economic instability expected for a few more months, the ENGRO buyback announcement might not be the last of it in the current buyback spree of the PSX. it might even be the case that the buybacks have only just started, and next year in 2023 we may see even more buybacks than the ones we saw in 2022. Time will tell. n

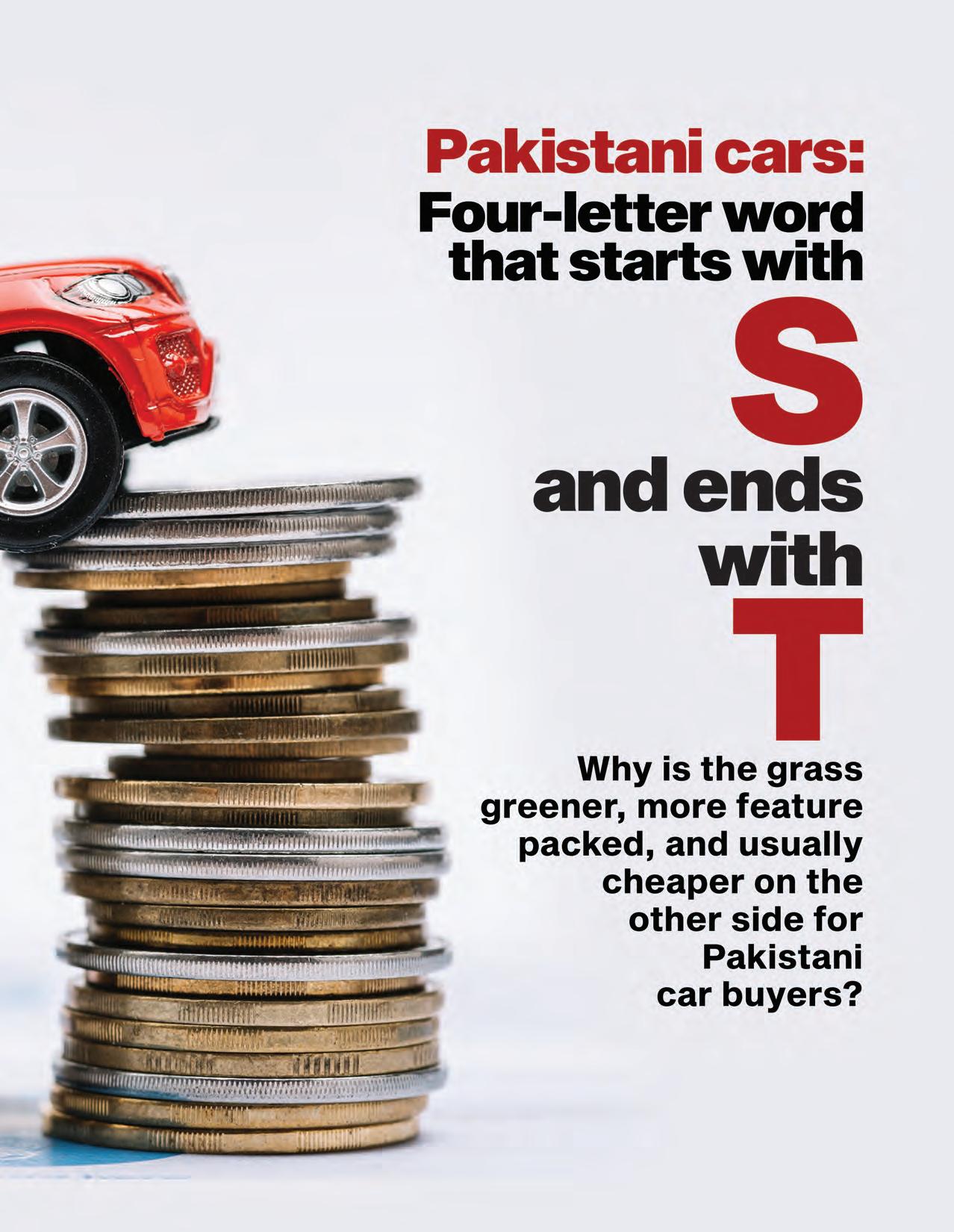

Let’s play a game. Profit wants you to look at any video of a new locally manufactured car, and count the number of times the reviewer presses down on the car, knocks on any of the panels, inspects places that none would ever really inspect, and says the words “They did not disappoint.” Most acquainted with the automotive space know why they’re doing this, but to the casual viewer it’s nothing short of circus gymnastics. So, why do they do this?

They do this because they’re trying to inspect whether a locally made car, known as a completely knocked-down (CKD) unit, is as good as its imported counterpart or rivals, known as a completely built-up (CBU) unit. Everyone at this point knows that Pakistani cars are not the best in terms of quality. Those who disagree are more than welcome to scroll through PakWheels or other comparable websites and try not to suffer in agony when they outline the premium that Pakistani buyers pay on average for the honour of getting fewer features, or an outdated design. Or all of the above in some instances.

Once you’ve recovered from the agony, you’ll see that the responses for why this is the case to be quite generic. They mostly boil down to: The industry is either still growing, it doesn’t have the scale like its rivals in those aforementioned social media posts, or our companies are just evil. However, as a customer this explains nothing. The more savvy amongst us will tell you to go and look at the customs codes, industrial policies, and productive capacities to make a fair comparison on the basis of total factor productivity. However, this makes no sense to most people and requires far too much effort than anyone’s willing to put in. Thankfully, Profit does have the answer to all these verbal gymnastics that people go through to explain the matter.

The answer to the question boils down to three factors: our market is simply not big enough; it is unlikely to become big enough anytime soon as it lacks the capability; our industrial policy incentivises and encourages this entire mess.

Now let’s get on with the more detailed answer.

Firstly, to have a good car, you have to ask what makes a good car company, and in our case an entire sector? Now this might sound rudimentary but it’s important, bear with us. “Having a successful car industry requires you to have scale. You will either need a large enough domestic market or be integrated into larger markets. You also need to have upstream industries such as metal or rubber that will feed into your industry,” says Dr. Ali Hasanain, Associate Professor at LUMS. Now the question is, where does Pakistan stand on these metrics? Furthermore, if we are comparing Pakistan with other countries, who are going to be these countries?

The countries that are used to benchmark the progress of Pakistan’s automobile industry are ”Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia, and India,” says Asim Ayaz, General Manager (Policy) at the Engineering Development Board (EDB).

So far so good.

Now, let’s start off with the most basic of things. It is almost impossible to compare the cost of producing a car in one part of the world with another because of the sheer opacity. A single car is made of tens of thousands of components that are sourced from different parts of the world. No one, other than a company itself can reveal the difference in the cost that they incur in manufacturing the same automobile in two different markets. You can try to conduct the exercise for yourself, but trust us when we say that it will take more than a while to do all of this. However, a relatively easier way to gauge the difference in cost would be to compare the prices in different regions as it is reflects in the final cost companies incur in different markets

Profit had previously inquired with industry sources about the ideal gross-profit

margin (GPM) that companies aim for. “We set our prices to achieve, on-average, a GPM of 15% above the cost of assembly and import for the CKD and CBU units respectively,” said one of them. Muhammad Faisal, President of the Automotive Division at Lucky Motors Corporation, says this 15% is “hefty”. So use this as an upper bound and backtrack, for whoever does want to get into the mathematics behind this. This is where the fun, and education, now starts.

Now as customers, Pakistanis probably pay the price in accordance with the upper limit of that GPM. We’ll explain why we say this later. However, more importantly in determining the price to features provided that a car company chooses to employ comes down to a macroeconomic variable: The number of cars it can theoretically sell.

Let’s get one thing straight, entering the automotive business is not for the faint of heart nor those with tight purse strings. Hyundai Nishat is estimated to have incurred a cost to the tune of $400-500 million in 2017 to set up shop. The day-to-day operations of managing your automotive plant are also expensive. How expensive? Well, let’s just say that companies in Pakistan shy away from revealing their actual costs, however, they do offer something else in return; the fact that they need a certain volume to sustain production.

Profit has documented the innumerable instances of companies that have declared non-production days on account of the lower volume they had this year. In simpler terms, they need a certain fixed amount of units to be able to actually be operational. Otherwise, it’s more expensive for them to keep the lights on. Herein lies the first of our aforementioned premises.

Volume is truly a magical word in the automotive world. “Volume is one factor. Taxes and duties are another factor,” says Ayaz when asked as to what are the main reasons for why Pakistanis cannot have nicer cars in comparison

Mansha Sb, Taba Sb, Sherazi Sb, Habib Sb, and the rest are good people. They are honourable people. None of them are tax thieves. They pay their taxes and truthfully conduct their businesses. They are not thieves nor are they anti-Pakistan. However, everyone reacts to their policy incentives. If you have issues with car companies then you should address the laws and regulations so that their incentives are corrected

to their regional counterparts. Thankfully for us, those aforementioned social media posts show prices exclusive of taxes. We’ll get to the duty part later. So, volume. Pakistan does not have much of it.

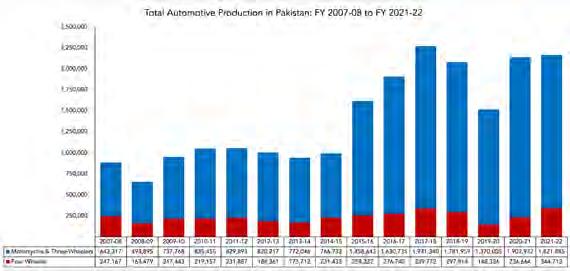

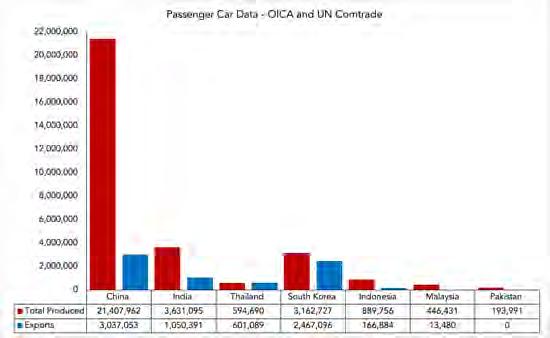

Remember the countries we identified? They produced an average of 1,390,493 cars in the calendar year 2021, based on data provided by the International Organization of Motor Vehicle Manufacturers (OICA). This was 7.17 times higher than the 193,991 cars that Pakistan produced over the same period. Similarly, more advanced automotive markets such as South Korea and China have produced 16.3 and 110.36 times more cars than Pakistan respectively over the same period. Ouch. But sit tight because it gets worse. Let us explain this double whammy.

The importance of volume is that companies have a hierarchy in their cost mechanisms. The fixed costs of setting up shop, i.e. that $500 million, take precedence. Now companies can either make 100 units in their plant or 1,000 but the fixed costs will remain the same. Therefore, companies like to opt for the latter to reduce their cost per unit. The more they make, the more it goes down, and the more units they can sell to recoup their investment. Economies of scale. Thus, the more the volume, the cheaper it is to add that auto-dimming mirror which car companies still categorise as a ‘feature’ in 2022. And vice versa.

So, Pakistan lacks domestic volume to

sustain a car industry in a similar capacity to the other aforementioned countries. That’s not an issue per se, because other countries also face this problem. It’s only China, and India to a lesser extent, who’s industries were driven by their domestic markets. Other developing countries that built their car industries did so through the second point Hasanain mentioned: Integrating into a larger market.

Exports from Mexico primarily target the US market under NAFTA whilst Thailand has become a location for supplying ASEAN. The Czech Republic, Hungary, Slovakia, Romania and Poland became locations for exporting to the EU. When common trade zones remove customs walls, competition for investment is guided by comparative advantages in production costs. Without membership of a large economic zone in which duty-free internal-market trade exists, no developing country has yet succeeded in entering export markets for cars on a significant level. So, how many has Pakistan exported? Pakistan has only exported one singular car, till date. Profit asked Danial Malik, CEO of Changan Master Motors, about their plans for exports after exporting Pakistan’s first car to which he has not responded yet. Needless to say the prospect does not look very promising at the moment.

Will we be able to export? That is a good question, and something that’s on the mind of everyone relevant to the industry. It’s unlikely.

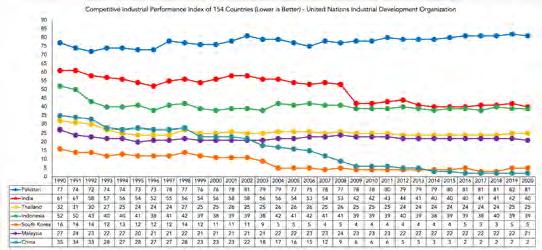

Now companies might critique the metric of comparing cars directly from different markets for some odd reason. It’s their child after all, and which parent wouldn’t? Another way to look at the export competitiveness of anything from Pakistan’s manufacturing sector would be to look at the United Nations Industrial Development Organization’s Competitive Industrial Performance Index.

The Competitive Industrial Performance Index benchmarks the ability of countries to produce and export manufactured goods competitively. It provides a graphical summary capturing the competitive performance of each of the 154 countries included in the 2020 CIP Index, relative to their performance in previous years and compared to that of the rest of the world. Pakistan ranks the worst across all of the aforementioned countries. It secured the 81st position in 2020, the last time the index was calculated, in comparison to India being 40th, Indonesia being 39th, Thailand being 25th, Malaysia being 21st, South Korea being 5th, and China being 2nd on the list. Pakistan’s also actually gotten worse over the years.

Furthermore, looking at Harvard’s Atlas Complexity, the new products that Pakistan has added to its export basket from 2005 to 2020 have nothing to do with the automotive sector to begin with.

The new products that Pakistan has added are attributable to the chemicals, metals,

minerals, and agricultural sectors. You could jump to the conclusion that these sectors are ancillary to the automotive industry. However, that would be incorrect. The Atlas includes the automotive sector, and subsequently encompasses any and all products even remotely associated with the sector.

What does this mean then? It means Pakistan not only has made ANY progress in the aforementioned fifteen years towards exporting anything from the automotive industry in any meaningful manner. But, its ability to do so relative to the rest of the world has actually diminished over time as well.

Put simply, if we can see those social media posts that indicate the world has better cars than we do then so can the world. Why would the world want to buy something from us that we would ideally like to not buy? But this is not a secret to anyone. The Auto Industry Development and Export Policy (AIDEP 2021-26) sought to fix this exact problem.

AIDEP sought to expand domestic capacity to 600,000 passenger vehicles, putting us right above Malaysia. Until it didn’t.

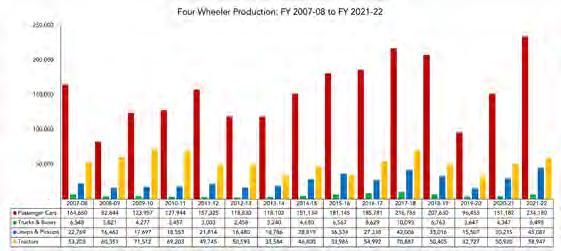

The Pakistan Automotive Manufacturers Association (PAMA) figures reveal that the domestic Pakistani market for automobiles has actually

grown over the past years. Total automotive production has increased at a compound annualised growth rate of 6.56% between FY 20078 and FY 2021-22 which saw total automotive production in Pakistan increase from 890,484 units to 2,166,597 units.

However, this is perhaps as good as it gets for a while to come. Why do we say this? Because FY 2021-22 levels alone were enough to bleed so much foreign exchange that the State Bank had to step in and put a halt to the industry entirely. Profit has already documented this matter in detail for those interested.

Read more: The SBP is controlling car imports

The tl;dr edition, and what’s relevant to us is that Pakistani companies rely HEAVILY on imported components in manufacturing cars. Now that too is fine, it’s normal for any industry that’s part of the global value chain. The only problem is that ours is in a state of perpetual limbo. It uses imported inputs for products that are not exported in the end. Our existing export volume of other goods also, evidently, cannot sustain this production method.

Before the bad news, how about some good news? Pakistan’s current balance of payment crisis is largely in part due to the rise in the global price of oil. Furthermore, all the new automotive companies that pushed up imports did so because they are still new and lack the local supply chains that the Big 3 of Toyota,

Honda, and Suzuki enjoy. The more they age, the more they will hopefully localise and thus not rely on imports. Theoretically, FY 2021-22 volumes can be beat.

Now the bad news. Those volumes are unlikely to be outdone exponentially. If for nothing else then because automotive companies’ localisation numbers are as good as monopoly money when it comes to actually fixing Pakistan’s economy. Profit has documented this too in detail.

Read more: How does Pakistan’s auto industry contribute to its balance of payment crisis?

More importantly than the problem with our deletion numbers is the actual process of achieving that deletion. This is where we go back to Hasanain’s last point: Upstream industries. Profit will actually expand upon his point by including ancillary industries that can support this endeavour. Why are we being liberal with his point? Just so that we can tell you how bleak the situation actually is.

One way to determine Pakistan’s ability to manufacture cars and look at the ancillary industries is by looking at the Atlas of Economic Complexity by Harvard University, again. It would be useful to actually explain it this time around.

The Atlas looks at a country’s economic complexity to determine its aptitude to produce other goods and services. Economic com-

Having a successful car industry requires you to have scale. You will either need a large enough domestic market or be integrated into larger markets. You also need to have upstream industries such as metal or rubber that will feed into your industry

Dr. Ali Hasanain, Associate Professor at LUMS

plexity of a country is calculated based on the diversity of exports a country produces and their ubiquity, or the number of the countries able to produce them (and those countries’ complexity).

Looking at Pakistan’s product space on the Atlas shows that it has no ancillary industries that can support large scale car manufacturing. Cars, in fact, are actually completely divorced from the entirety of Pakistan’s existing industrial base. Furthermore, the Atlas also determines how easy it would be for Pakistan to undertake the task of manufacturing automotives based on its existing base as well. So, how easy is it? Well, not at all actually.

The Atlas looks at the top 50 products that any country can ideally make based on their existing capabilities. Parts of motor vehicles rank at the very bottom at number 50 with motorcycles ranking at number 44. All other motor vehicle categories are not even on the list. Make what you must of that.

In essence it’s like a game of jenga. You need to have a base upon which you can add your fancy new Sino-Franco-Japanese-Korean car pieces.

So let’s catch-up. The automotive industry is an expensive business, and adding the latest features to a car is also very expensive. Companies keep their costs per feature they add by spreading it out over a greater number of units produced. Pakistan does not have a large enough domestic customer base which makes our companies inefficient, but they are also so inefficient that they can’t actually export the cars. AIDEP sought to increase Pakistan’s export competitiveness by creating a greater domestic market to facilitate economies of scale. However, Pakistan does not have the supporting industries to undertake this task which in turn led to the economy overheating, and forcing the Government to cut the sector down to size. This is a roundabout, really. No pun intended.

Continuing with our jenga reference, Profit would like to add the final piece because we, unlike the automotive sector, built a proper puzzle. The automotive companies, likely, do not care if anyone knows this.

The easiest solution to anyone wanting to rid themself of the ghum associated with those posts is to import the new Sportage rather than wait for it to be made locally at this point. However, the duties would probably make you want to buy a Fortuner instead. This is not accidental. If there’s anything the government loves more than curbing the local automotive industry to stem the flow of foreign exchange then it’s stemming the imported automotive industry.

“We have a lot of these assembly sites that have been set up around the country and they have been given incentives to do that. One major incentive that they are given is high tariffs. The high tariffs gives them the incentive to jump tariffs, come to Pakistan, invest in it, and avoid these tariffs,” explains Dr. Aadil Nakhoda, Assistant Professor at IBA.

Why is protectionism the route which Pakistan uses to attract companies? Well, that is another debate entirely. It is also beyond the scope of this article. However, this is the system that we do have, and the local companies are fully cognisant of this. This is why they are more likely than not to charge you that 15% GPM we talked about. This is also where the notion of tax and duties is negated, somewhat at least. “The tax and duties that can be passed on depend on the relative elasticities of supply and demand. They can pass on these as the demand is inelastic because there are no outside options,” Hasanain tells Profit

“What is the threat that Toyota, and its peers face? Second-hand automotives from Japan. So think about this, manufacturers in Pakistan are worried about competition from four year old second-hand cars that come into the Pakistani market,”

says Nakhoda. If you look at it like that, our cars are not quite bad when compared to four year old cars made for the Japanese market. And that is exactly the satisficing our companies need to do to continue their revenue streams.

In case you are in disbelief then let us convince you otherwise. The thing with tariffs is that there are two kinds of them: direct and indirect. Direct tariffs are additional levies on anything. They’re rather simple and are generally defined by automotive experts as brute force measures to mitigate imports. Indirect tariffs, however, come in different shapes and forms. One manifestation of indirect tariffs is technical non-tariff barriers.

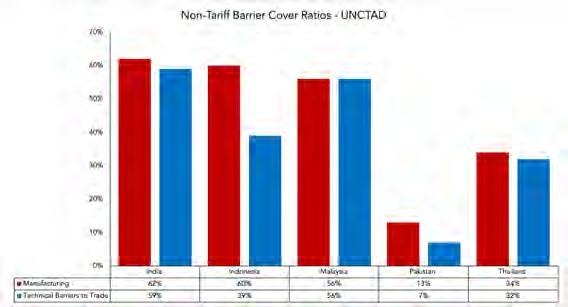

Looking at non-tariff barrier data provided by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, it is evident to see that Pakistan really doesn’t care much about why it’s stopping imports and rather just wants to stop them. The country ranked the lowest, amongst the aforementioned identified countries, in terms of cover for both its manufacturing industry and in terms of technical barriers to trade.

The former indicates that Pakistan’s only policy, relative to the identified peers, towards utilising tariffs in the manufacturing sector is to just price out imported substitutes. Similarly, the latter indicates that Pakistan does not really care about the quality of inputs that are imported into the country. Again, as with the former, the latter indicates the only aim is to price out foreign substitutes.

“We’re not protecting our industry technical measures, we’re utilising tariffs for

What is the threat that Toyota and its peers face? Second hand automotive from Japan. So think about this, manufacturers in Pakistan are worried about competition from four year old second-hand cars that come into the Pakistani market

Dr. Aadil Nakhoda, Assistant Professor at IBA

protectionism. What that basically means is that we don’t care about the quality of the cars that are running in Pakistan. If we don’t apply these to imports then we really don’t care about what’s going to happen in the local production processes,” says Nakhoda.

“Mansha Sb, Taba Sb, Sherazi Sb, Habib Sb, and the rest are good people. They are honourable people. None of them are tax thieves. They pay their taxes and truthfully conduct their businesses. They are not thieves nor are they anti-Pakistan. However, everyone reacts to their policy incentives. If you have issues with car companies then you should address the laws and regulations so that their incentives are corrected,” Dr. Miftah Ismail, former Finance Minister of Pakistan and one of the Architects of the 2016-21 Auto Policy, tells Profit when asked if the companies were gaming the system.

Not having auto-dimming mirrors is a travesty for anyone that’s driven ahead of a Honda Civic on the streets of Lahore. However, we’ve outlined why they’re unlikely to become standardised anytime soon. The question then is what would it take?

The easy answer would be to simply have a proper functioning economy, liberalise trade, and just import whatever car you want. However, at this point you are more likely to win the lottery than to be able to convince any Pakistani government to undertake this task successfully. Tariffs aren’t all bad. “Does Thailand not have tariff protection? Does India not have it? Does Malaysia not have it? They have also protected their sectors. They are perfectly intelligent countries so what is the harm in copying them? Our sector is less protected than theirs,” says Ayaz.

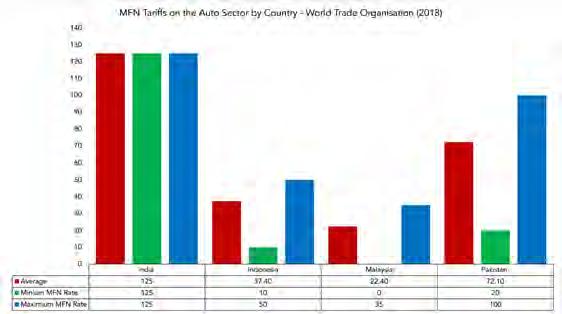

Looking at the tariff data provided by the World Trade Organisation, Pakistan’s automo-

tive sector is less protected than India’s based on most favoured nation (MFN) tariffs, and is actually comparable to Indonesia. MFN tariffs are the highest rates that countries can impose on trading partners that are members of the WTO. Comparison with other aforementioned countries could not be conducted because of the mismatch in data available, as Pakistan’s does not exceed 2018 and the others do not provide data as far back as 2018.

The aim should be to try to find a solution utilised by Thailand and Mexico, for example, and find a way to integrate into global value chains to achieve the desired capacity rather than continue down the India and China route. Unless, of course we find a way to fix the aforementioned issues highlighted that hinder us from emulating India and China. Creative solutions are of the utmost importance.

“If you were to suddenly open imports then all the new companies that did invest in Pakistan would suffer a huge loss. The solution to that is, unfortunately nothing in Pakistan happens like this and this is unlikely as well, you formulate a plan to pivot all those companies. You tell them that they can make as much money as you want for the next four to five years to recover your investments. However, you tell

them that you will taper off protectionism in the coming years, and eventually you will completely open the automotive market to imports in the tenth year,” explains Hasanain.

Is this a viable solution? Perhaps. “If you had used the word shampoo instead of car then it would have still been valid. We have protected the local shampoo industry as well, just maybe not as much. We have provided protectionism to every sector,” states Ismail.

“The notions on which our edifice of import substitutions were built are long standing. You cannot remove it immediately. If you want to manufacture a car in Pakistan and also levy duties on its imports then the current situation is a given. In my opinion, everyone stuck in this mess is stuck,” Ismail continues.

As much as Profit would like to tell you there’s hope, but there isn’t much to be honest. You may ask why we make cars at all to begin with then? That is a debate for another time, however, it is one that will pester us because the solution to getting as many airbags in all our cars as the ones in India is not one that will come anytime soon. Rest assured that social media will continue to bombard us all with those posts about how much better cars are the world over in the meantime. n

When you look deep into the abyss, the abyss looks back at you. Such is the nature of darkness. Similar analogies can be drawn for the state of Pakistan’s economy, and human development.

There is a political class oblivious to the problems of the country, and its populations. Even if this class is aware, it is looking the other way. There is a junta which refuses to let go of being the puppet master. It wants more of the pie, but isn’t smart enough to expand the pie. Ensuring it continues its role of being the master of puppets, it produces one puppet show after another, sometimes even repeating earlier shows, as if it’s groundhog day – A day which keeps on repeating till eternity.

Economic policymaking in Pakistan follows a similar trajectory. The policymakers who were at the helm three decades back are still around, and still using the same tools, and ideas that they used in the last century, and failed. Learning from failure isn’t really a virtue, so we prefer to keep making the same mistakes again and again, despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary.

A favourite mistake that we keep on repeating is the obsession with an arbitrary, or fixed exchange rate. There is sufficient evidence available that fixing an exchange rate in economies that are heavily dependent on imports is a recipe for disaster. There is evidence spanning decades and across geographies suggesting the same, but somehow our policymakers refuse to learn. The current government continues to maintain a pegged exchange rate, which is leading to demand-supply imbalances, as the inflow of foreign currency dries up.

Remittances are being routed through informal channels, while export-oriented businesses inch towards being more

uncompetitive in terms of pricing. A natural extension of any arbitrary ceiling is development of a parallel market, and the same has also happened in the case of US$ in Pakistan. A parallel market exists informally in which the US$ trades at a 10% to 12% premium to the central bank’s ‘managed’ price. The policymakers at the helm refuse to accept this as a problem while the economy races towards a complete disaster, if there wasn’t one already.

By keeping the PKR artificially inflated, the government in order to score some brownie points with its electorate (or the lack of) also reduced petroleum prices. The reduction in petroleum prices makes absolutely no sense, particularly given a perpetually growing deficit and an artificially propped up currency. As prices are downward sticky, which is an economist’s way of saying that once prices of goods increase, they often don’t come down (unless they are commodities), a reduction in petroleum prices does not necessarily result in downward revision in prices of other goods and services that are dependent on petroleum in one form or another.

However, once the peg to an arbitrary PKR-US$ value breaks, and the PKR depreciates, petroleum prices may also increase as they are predominantly imported. As petroleum prices increase again, we may see another round of inflation. Even though the intent of policymakers may be the exact opposite, the reality is different. Inability to learn simple concepts such as prices are sticky, or that arbitrary floors and ceilings lead to more inefficiencies and sub-optimal outcomes continue to push the country towards a disaster.

As we keep repeating the same mistakes time and again, the policymakers are not only failing the current population, but also the future generations. The country has a median age of 23, while the median age of men representing the population is close to 67. In such a scenario, the leadership is, if not completely oblivious, completely clueless.

The writer is an independent macroeconomist and energy analyst.

Human development Indicators in the country continue to deteriorate, whether that is the number of children that are out-of-school, or the number of children that are malnourished, or suffer from acute stunting. We continue to fail future generations, while refusing to learn any lessons. In a non-rigged scenario, natural selection would take care of those who don’t learn their lessons, but not in the case of policymakers who refuse to budge from tools, and strategies that haven’t worked in decades. The abyss is looking back at us. The boom-bust cycles cannot continue for long, as the duration between each boom, and subsequent bust shortens. The puppet master and the puppets may want to think about their legacy and what they will leave behind for future generations, unless of course their personal generations will be settled offshore, and not in the country they continue to destroy.

By Shahab Omer

By Shahab Omer

Just like every winter, the heart of Punjab is yet again blanketed under a heavy layer of smog, except this time anti-smog campaigners call for a necessary lifestyle. The response, somehow, has been to go after the City of Lahore’s restaurants.

An energy saving policy has been announced to limit consumption, travel and all other related capitalistic aspirations that directly leave carbon footprints in the environment. For the most part the general population agrees and seems to make implementation of the government’s much needed climate change policies possible. But there’s one area the governments will definitely struggle with: Curbing the Lahori desire to eat out.

The energy saving policy has limited the opening hours of the restaurants, and the industry is obviously not happy with it, nor are the consumers. In the survey conducted by Profit, it was observed that restaurants in most of the main places including Johar Town,

Faisal Town, Ichra provide dine-in facilities even till 12 o’clock at night.

Bringing these hours down to 10 pm, or 8 pm, and cutting down on peak hours will clearly not be the easiest task. But sometimes necessary actions are required for greater good, and Lahore’s authorities are ready for them.

The story starts from Lahore High Court (LHC). A week ago, a hearing was held in the LHC regarding the smog remedy, in which Justice Shahid Karim ordered the closure of all markets till 10 pm.

The court ordered the restaurants to be closed by 10 pm, and on Friday, Saturday and Sunday at 11 pm. The court order was apparently accepted willingly by the restaurant industry, but the district administration of Lahore could not fully implement it. According

to the data obtained by the district administration of Lahore, action has been taken against more than three hundred small and big category restaurants and hotels so far. This included Butler’s Cafe, KFC, Mouthful, Coco Cubano which were sealed by spraying water on burning stoves beyond the time limit.

The issue intensified a week later when Federal Minister of Defense Khawaja Asif announced various measures regarding energy saving and said that a policy related to austerity is being formulated under which restaurants, hotels and markets will be closed at 8 pm. Asif made this announcement during a press conference in which he also suggested that in view of the dire economic situation, the nation has to change its habits and spend within its own means. The policy was to be finalized by Thursday, December 22, but the government is still silent on this issue. As soon as Asif’s press conference was held, business organizations across Pakistan, restaurant associations and even unrelated business organizations kickstarted their resistance.

Cutting down peak hours and limiting restaurants to operate till 10 pm is a lifestyle change for Lahoris, but now it is necessary to adapt

Profit received a copy of a letter of the Lahore Restaurant Association (LRA) addressed to the Prime Minister of Pakistan.

The letter claimed that the restaurant sector is a major revenue generator for Pakistan and closing it at 10 o’clock could adversely affect the country’s economy. The LRA has written down more or less all the basic problems of the restaurant sector and the government policy, which may cause possible losses to the said sector.

“The Lahore Restaurant Association actively represents the interests of all the restaurants in Lahore. There are currently almost 400 members across Lahore. As you are aware, the Restaurant & Hospitality industry is a major revenue generator for the Government of Punjab and is also the second highest domestic employer in the province after construction, with the restaurants hiring 6 times the human resources versus ordinary retailers. The Restaurant Industry in Lahore faces seasonality in the sense that it performs better in winter than in summer, with the last two weeks of December being the peak season for most of the restaurants. This is primarily so as Lahore sees an influx of 600,000 additional tourists to the city in the form of non-resident Pakistanis that come back over the winter holiday with money to be spent at local restaurants. Most restaurants gear up for this season by hiring additional resources, while some such as those that focus on solely seafood operate only in winters. Thus, are a major channel that funnels this influx of foreign capital to the economy. Any decision to restrict restaurant operations for closure at 10PM would have a crippling effect on the overall industry and economy,” read the letter.

The letter also stated that restaurants do not only provide the second highest employment in the country, but also provide support to dozens of upstream and downstream businesses.

Interestingly, in the same letter the association took the chance to shed light and suggested another proposition - regarding tax. “The irony of such a decision would be that the actual enforcement of this restriction would be implemented by the local administration upon the well-known (tax-generating restaurants) whereas informal sector restaurants, like smaller dhabas ‘and outlets, who do not pay sales taxes and are not regulated or registered with any tax authority, would hardly be dealt with by lower administrative staff.

As such, the most logical decision would be to provide relaxation to sales tax paying restaurants only, to continue operating till 12AM on weekdays and 1AM for weekends. Restaurants, which are not registered with tax

authorities, should be subject to early closure, as per the cabinet decision. Such an approach would also provide incentive for businesses to be registered and start paying taxes,” it read.

Portraying a class case of not owning up to the damage, the letter further said, “The LRA truly believes that our member restaurants or restaurants in general are not the ones that can be categorized as wasteful energy consumers… Regardless, if restaurants are open or closed the energy consumption in the winter season will almost stay the same as the refrigerators are not switched off once the restaurants are closed. We request that you take our plight into consideration and that we work together to come up with a long term solution to the problems at hand,” they concluded.

The LRA has mixed up the court decision and government policy in its letter. It is important to note that the government is yet to implement a policy under which restaurants will be allowed to operate till 8 pm. As of now, there is implementation of only LHC’s order to close down restaurants by 10 pm to mitigate smog. However, in both cases, the business of the restaurant sector seems to be affected and the LRA is clearly ahead in its resistance.

Most restaurant sector administrators are reluctant to consider any new options and seem adamant that the government should not change its policies. Profit reached out to several restaurant owners in the industry and what they had to say:

Shahzad Khokhar, the owner of Cafe Zauq, believes that it is not possible to do business in these conditions. He thinks that this will lead to dine-in culture completely disappearing.

“After a long time since COVID-19 lockdown, the trend of people to dine-in has gained pace. But the industry still has not fully recovered since the outbreak of Covid-19. Restaurants still don’t have the capacity to hire as many employees as they did in 2018. The first thing to understand is that people never come to eat in restaurants at 4 pm and those who are deciding to close the restaurants at 8 pm themselves never dine in restaurants in the evening; rather, the activities and sales of restaurants increase late at night,” he said.

Similarly, Malik Muhammad Yasin, a partner of a restaurant located in Lahore’s DHA, said that the culture of restaurants is linked to dinner in Pakistan specially Lahore and Karachi. “In such a situation and environment, if the government closes the restaurants in the evening, the restaurants will remain closed. We

will be forced to lay off our staff,” he said.

When Yasin was asked if the restaurants really had no option in these circumstances, his reply was that there was definitely no other option but to close the business.

However, Malik Aftab, who runs a restaurant in Lahore Shahi Bawarchi Khana, believed that restaurant is a very wide scope business and if there is a need, the style of doing this business can be changed without moving towards closure.

“The government’s policy has not come out yet, but I am sure that the home delivery service will not be stopped. Right now, home kitchen operators are doing their business only through apps like Foodpanda. Even if restaurants close at 8pm or 10pm, takeaways or home deliveries keep our business alive. I have planned to work on the cloud kitchen idea also in Lahore. Yes, of course, there is a huge investment in this business and if I have to run my business through home deliveries and takeaways, I will definitely lay off more than fifty percent of my staff. Even when the wedding halls had to observe ten o’clock, there was a lot of noise from the catering businessmen and the owners of the wedding halls, but with the passage of time, people adjusted to these working hours,” he said.

Hasan Arshad, director of policy and communication at Foodpanda, informed Profit that there are concerns of the restaurant industry and stakeholders that need to be addressed urgently.

“Deliveries were also allowed in the lockdown of Covid-19 and these deliveries were the economic lifeline of restaurants. Even now we are asking the government to limit the timings for smog or energy saving, but don’t let the deliveries stop. If we talk about energy saving, the energy infrastructure of restaurants like fridges, freezers are still running even after the restaurant is closed. Yes, however, more expenses are incurred on dine-in and the business of restaurants that focus on dine-in can be greatly affected by such policies. If the restaurants are closed, what will we deliver? Even if restaurants have to close at 8 o’clock, people will shift their timeline but those who order deliveries between 9pm and 2am are also a large market that cannot be ignored or eradicated. We have introduced the concept of cloud kitchen in Pakistan and the restaurant industry should also shift to it,” he said.

The restaurant and hospitality industry faced a massive blow during COVID lockdown phases. The restrictions do seem very difficult for an industry which just regained its momentum this year. However, the restaurant business does not have an energy saving plan or path towards sustainable growth. Given the intensity of climate catastrophe, the future will truly be the survival of the fittest. n

By Ariba Shahid and Taimoor Hassan

By Ariba Shahid and Taimoor Hassan

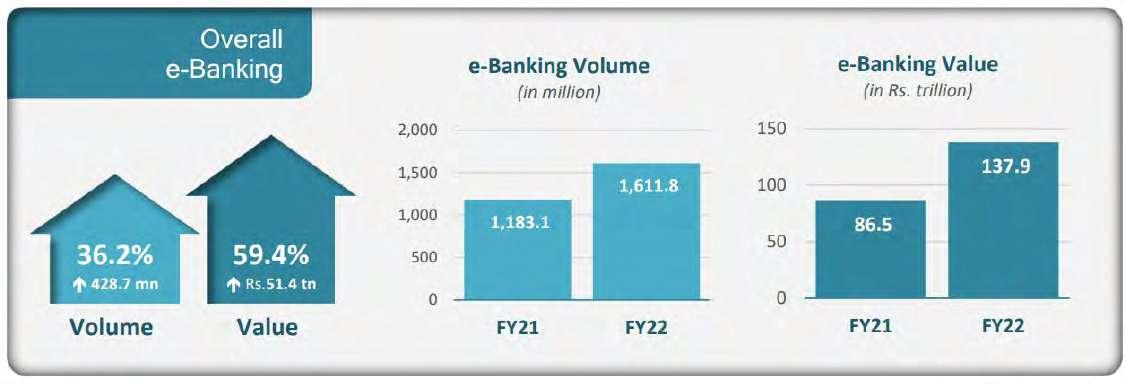

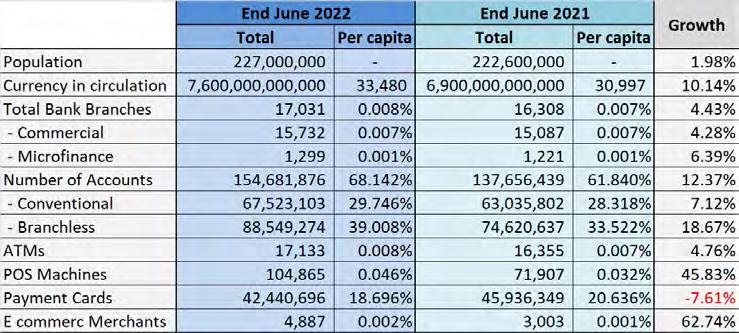

Ah, it’s that time of the year when you look back and reflect on performance and set targets for the future- resolutions. In a similar, but not so sentimental way, the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) released its Annual Payment Systems Review for 2021-22 looking back at the way payments were made in Pakistan during the fiscal year.

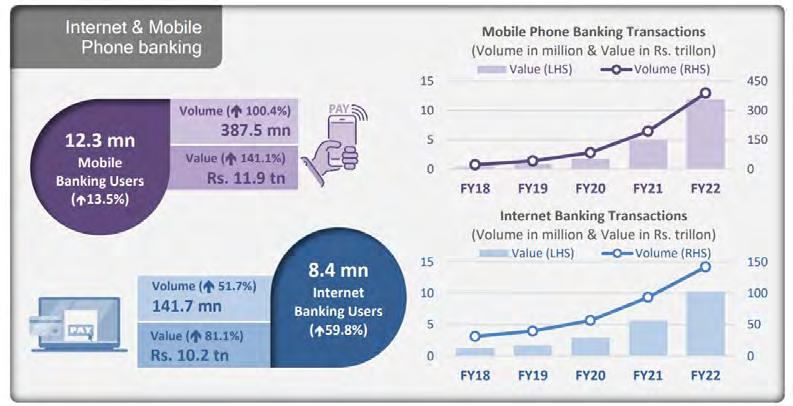

In a year where macroeconomic indicators haven't been the most positive omen, the Annual Payment Systems Review for the year has given some hope to Pakistan while it battles low financial inclusion; stating that mobile phone banking increased by a whopping 100.4% to 387.5 million, while internet banking grew significantly by 51.7% to 141.7 million during the year.

• By value, mobile phone banking and internet banking grew strongly by 141.1% and 81.1%, thus, reaching to Rs 11.9 trillion and Rs 10.2 trillion respectively. E-commerce transactions also witnessed similar trends as the volume grew by 107.4% to 45.5 million and the value

by 74.9% to Rs 106 billion.

• During FY22, a total of 32,958 Point of Sales (POS) machines were deployed in the country which led to an expansion of its network by 45.8% to 104,865. The total number of transactions through POS, 137.5 million, was 54.5% higher than the previous fiscal year with transaction value reaching Rs 0.7 trillion growing by 56.1%.

• E-commerce merchants registered with the banks increased to 4,887 in FY21-22, from 3,003 merchants during the previous year.

• In continuation of its efforts to promote and enhance the digital payment system in the country, SBP launched Raast Person-to-Person (P2P), which enabled payments among individuals, businesses, and other entities to settle transactions in real time. According to the report, as of June-22, there were 15 million registered P2P Raast users, carrying out 7.9 million transactions amounting to Rs 102.1 billion in value. Raast was launched in November last year.

• The number of large-value transactions through the Real-Time Gross Settlement (RTGS) system of Pakistan reached 4.37 million by FY22 amounting to Rs 681.6 trillion with an annual growth of 53.3% in value. During FY22, paper-based transactions declined by 1.0% in volume though its value grew to Rs 190.4 trillion, almost 25.6% higher than last year.

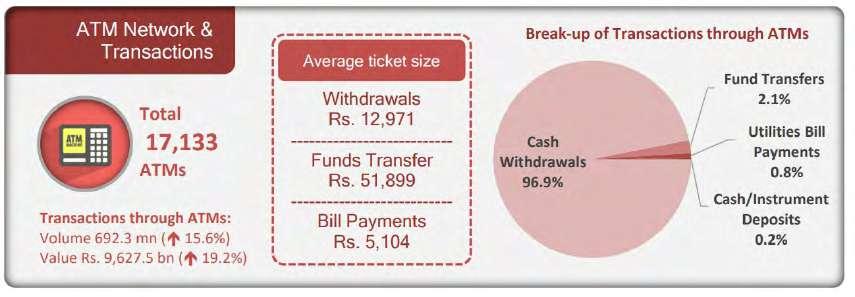

• The ATMs network in the country also grew by 4.8% during the year reaching 17,133 ATMs. A total of 692.3 million transactions were carried out through ATMs which amounted to Rs 9.6 trillion, 19.2% higher than FY21. Meanwhile, cash withdrawals from ATMs picked up from 577.3 million in volume

and Rs 7.29 trillion in value in 2020-21, to 670.6 million in volume and Rs 8.6 trillion in value. That’s a growth of 16.1% in volume and 18% in value over the previous year.

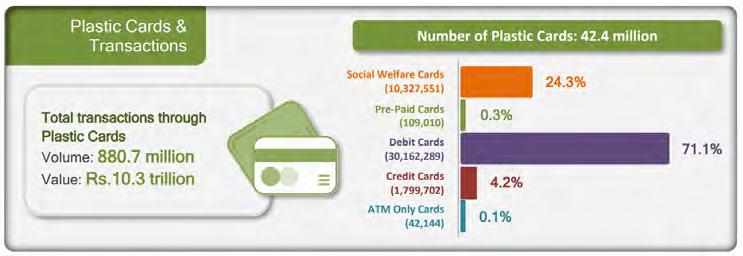

• There were 42.4 million payment cards in circulation in FY22 including 71.1% or 30.16 million debit cards; 24.3% or 10.3 million social welfare cards; 4.2% or 1.79 million credit cards and the rest were pre-paid and ATM-only cards. The overall number of payment cards, however, decreased during the year, from 45.9 million in 2020-21 to 42.4 million in 2021-22.

• According to the SBP’s Annual Payment Systems Review, the number of conventional bank account holders increased by 4.5 million, from 63 million account holders in 2021 to 67.5 million in 2022. On the other hand, branchless banking accounts increased from 74.6 million to 88.5 million, a growth of 18.6%.

While the report shows there has been a rapid pace of improvement in digital payments and financial inclusion. The pace is simply not enough.

While Pakistan needs aggressive growth in digital financial services for certain reasons. Pakistan’s struggles with financial inclusion are largely more elevated than peers and we

have the third-largest unbanked adult population globally. As per the World Bank, around 100 million adults across Pakistan do not have a bank account.

This is skewed to be worse for women in the country because they make up 82% of the unbanked population in Pakistan. The magnitude of barriers to financial inclusion can be gauged by the fact that 6% of the world’s unbanked population is attributed to Pakistan.

The issues of low financial inclusion aside; there may be more to the statistics than what meets the eye.

Pakistan’s macroeconomic indicators in the recent period have been nothing short of terrible. The country has had double-digit inflation and although the increase in the number of transactions is gratifying, the increase in the value of these transactions might very well be because of the rise in inflation. In real terms, the growth might not be that much as a result.

Similarly, ATM transactions show how strong the reliance on cash still is. Pakistan’s currency in circulation remains a staggering 20% of GDP. Nearly a decade ago, this statistic stood at 8% which means there is a strong growth in holding and transacting in cash.

During the year cash withdrawals from ATMs picked up from 577.3 million in volume and Rs 7.29 trillion in value in 2020-21, to 670.6 million in volume and Rs 8.6 trillion in value. This is a 16% growth in withdrawal transactions and a 17% growth in the value of those transactions.

Likewise, for some sectors, regulated margins have led to merchants not accepting card payments, or charging customers extra on cards, to recover their costs, incentivising cash transactions in the process. In September, some of the retail fuel stations stopped accepting card payments altogether or started charging customers extra to recover the MDR (merchant discount rate) charged to them by acquiring entities.

It seems like the governor wants to promote healthy competition and remind traditional banks that they’re only relevant as long as they are able to draw in customers.

Newly registered EMIs have reportedly worked on their user interface and kept charges competitive to draw in new customers.

According to the SBP’s annual report, the four fully licensed EMIs (electronic money institutions); Sadapay, Nayapay, Finja, and CMPECC, combined had 262,558 total active accounts and 514,961 payment cards issued to their customers. Last year’s numbers on EMIs were not available for a comparison of how these numbers have grown.

During his speech at the Institute of Banking Pakistan Annual Award Ceremony, Jameel Ahmad, Governor SBP stressed the need for banks to revisit their traditional approach to service delivery and adapt quickly as digitalisation shifts the balance of power from banks to tech-savvy entities, hinting at the growing trend in fintech.

The central banker also points out that while fintech has brought competition, it also presents the sector with an opportunity to create synergies and mutually beneficial partnerships.

“Banks and Fintechs can partner with each other to provide innovative products for customers that are otherwise not viable on a standalone basis. For banks, such partnerships can help with penetration in untapped segments like retail businesses and Micro and Small Medium Enterprises, yielding beneficial outcomes for all stakeholders,” he said.

Ahmed focused on the banking industry keeping up with global trends. He also pointed out that a number of factors already exist in Pakistan that can help drive digital financial innovation and the proliferation of a tech-based financial ecosystem. He pointed out that the nation has a fully functional digi-

tal ID system, the ubiquity of mobile devices, penetration of mobile and broadband services, availability of faster payment rails, a remote account opening process, and a facilitative regulatory environment for enabling the entry of non-bank entities into the financial arena.

But where it makes very little sense for banks to be is the digital banks' regulatory framework. Much to the chagrin of the young guns in the fintech scene, banks have been allowed to contest for a digital bank license, making them competitors.

While the move has received criticism from some quarters, former SBP governor Reza Baqir defended this saying, “There is no monopoly over ideas and that’s why we are open to entertaining applications from any and all investors even if they are already providing banking services in the country.”

But the move has been criticised because this can hinder the growth of fintech companies which are crucial for the quick growth of digital financial services. Banking bureaucracies are the reason why digital financial services were not able to pick up steam until the advent of fintech companies.

In a sense, this can promote healthy competition as well, giving banks a chance to do away with regressive bureaucracies if banks are really focused on enhancing digital financial services. But right now, with banks in the race along with the fintech companies for a digital bank license, chances are that the intentions of the banks are to just subvert competition rather than promote digital financial services. After all, there is nothing that financial institutions with full-banking licenses can not do under their current licenses.

The SBP is going to announce the first five digital bank licensees anytime now. The contenders include HBL, Bank Alfalah, JS Bank, DBank, JazzCash, EasyPaisa, Tyme Bank, HugoSave, Alif Bank, Mashreq Bank, and Pak Kuwait Investment Company.

While we are at it, the SBP’s own capacity issues also need to be highlighted. SBP has taken some monumental steps in promoting digital financial services. The EMI regulations were introduced in 2019 and the Digital Banks Regulatory Framework was introduced at the beginning of this year. The SBP is now responsible for regulating EMIs, PSO/PSP license holders, and now the digital banks. Moreover, the central bank is also running Raast operations itself.

With so many entities to regulate under different licenses, things could be moving slowly at the central bank. The announcement of the digital bank licenses was supposed to have happened by the beginning of December this year but we are almost into the new year now. If things move slowly at the central bank, this could affect digital financial services. The central bank should, therefore, also increase its own capacity with respect to regulating digital financial services. n

By Momina Ashraf

By Momina Ashraf

If there is one thing that’s hot in the cold of December, it is gold prices. Prices of the subcontinent’s favourite metal hit a record high of Rs 178,800 per tola, indicating an almost 11% increase since the start of December. This rise in prices has created a wave of hysteria and chaos for many Pakistanis. Desi families who traditionally give gold to their children at weddings are feeling helpless and don’t know how else to store their wealth. On the flipside, those who already have personal reserves for gold are finding silver lining in the situation. The Pakistani rupee is depreciating, but at least gold value is increasing!

But all that’s gold doesn’t necessarily glitter.

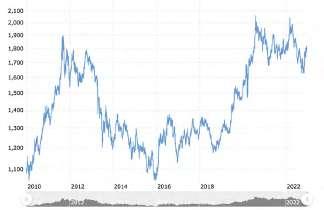

Contrary to popular belief, gold investments are not too great, and not as risk-free. Below is the chart of gold prices of the last hundred years. Because it’s a commodity against the US Dollar, its actual value is also determined by the US Dollar.

If you look at the graph closely, you’ll realise that if you bought gold almost a decade ago in 2011, you are sitting at a loss of $113 today! Forget 10 years ago, compare the prices of 2020 of $2,018 to today’s $1,780 and you

see a significant loss again. The graph shows exorbitant highs and lows just within a span of 10 years.

Gold is bought in dollars so every time a rupee depreciates against the dollar, gold prices also go up. Just like many other things in the

international market, gold is also affected by geopolitical tensions. Prices in the international market grew by 10% in March 2022 when the Russia-Ukraine conflict began. This indicates fear among the public which drives gold demand up as a means to wealth.

In Pakistan, there is an added factor - the gold mafias. Gold imports have been banned in Pakistan since 2007-08 (barring short periods of it being lifted) which means that all the gold transactions we see around us are essentially

recycled and repurposed gold available in the country. It is either that or gold inflows through smuggling. In either case, it means that the supply of gold is very limited.

On the other hand, demand is also actually not too high, but prices keep fluctuating. That’s because of the involvement of gold cartels and mafias. Haji Haroon Rasheed Chand, president of All Sindh Sarafa Jewellers Association (ASSJA) told Profit that demand for gold from the ordinary public has just been a meagre 25% since the last few years. The rest of the 75% demand comes from these cartels (who he didn’t wish to name). “Actually now these mafias comprise full 100% of the demand,” he mentioned. Ordinary people want to buy, but the price is increasing so rapidly that they are unable to, he added.

Mafias buy gold in huge quantities which makes the price fluctuate a lot. “Just within a day the price of 1 tola gold often goes up to Rs 5000-6000 because of huge demand,” Chand continued. He also mentioned that in Pakistan the price of gold is actually higher than what is rated in the international market because of the monopoly on demand. This is terrible for the market, he said. The purchasing power of the ordinary public is reducing and the price is artificially going up.

There is little to no way to protect the market either. Because gold is mainly smuggled in the country, there is no legal documentation of the transaction. This means that gold is not taxable. There is little to no control over who gets to buy what quantity of gold. “As the president of ASSJA, I basically had to threaten gold sellers to not sell gold to these mafias and brought back the price down by Rs 10,00012,000 just last month. Our people come first and the industry comes second,” Chand expressed emphatically.

As you might have figured out by now, not everything that glitters is gold. Pakistanis save a lot, just not in the right manner. Already written reports on Pakistan’s savings pattern suggest that about 16% of total savings are done in gold. This is something which doesn’t get accounted for in the formal financial system.

The graph above shows gold prices are extremely volatile. “It’s only the second most risky investment than cryptocurrency,” said Farooq Tirmizi, financial advisor and investment analyst.

Sure, the price in local currency increases, so one sees benefit in terms of rupees. But that’s where the problem lies. Your money may increase in rupees but in the larger scheme of things, your wealth reduces as rupee loses its value against other currencies, including, most importantly, the dollar. Here’s how:

You buy 10 tola gold to get rid of your rupees and keep it safe in a locker. You’ve essentially locked this value in gold instead of circulating rupees within the economy. But, there is currently more rupee supply in the economy and no productive services or labour against it, which means the value of the rupee is falling – reducing in value against other currencies, most importantly the dollar, which essentially has made imports, and most things you need and consume, more expensive. You may not be able to see the loss of your wealth in the short run but you’re actually losing value for money.

A good savings plan is one that gives you return, and makes you richer. “Investing in bonds and stocks puts the money in circulation for other businesses to grow and

produce,” explained Tirmizi. With money in circulation, the economy becomes better overall as there is cash available to produce and work more, instead of resorting to loans and printing more money. In addition, you get returns for the money you invested in currency and see how it multiplies yearly in real time.

In times of fiscal crisis, governments discourage spending and incentivise savings by offering a higher interest rate. This is what’s happening in Pakistan as well. As shown in the graph below, the interest rate in Pakistan grew by 77% in 2022. This is essentially the opportunity cost of storing wealth in gold rather than in a bank!

Gold, unlike other investments, does not account for value addition. “As a savings plan gold is often bought in pure gold bricks of 24 carats. Later, the same gold is used to make jewellery which reduces the gold value to at least 22 carats and adds value by giving it shape and style. However, if you wish to sell the piece of jewellery it will be sold at 22 carats with no account of the value addition,” said Habib-ur-Rehman, chairman of Pakistan Gems and Jewellery Traders and Export Association (PGJTEA).

In addition to that, gold bricks and jewellery are mostly kept in safe lockers at banks, which amounts to a charge of around Rs 3,700 to Rs 12,000 yearly depending on the size of the locker. Since a majority of Pakistanis follow the Islamic financial system, they pay zakat on their gold possessions too. In essence, one actually ends up paying for their gold savings rather than receiving returns out of it.

Despite all this, gold still remains a popular choice for savings in Pakistan. This may be due to religious reasons of avoiding interest or due to a lack of trust in the financial and banking systems - both highly plausible in Pakistan. But as we see our house collapsing, it is the perfect opportunity to build back better – stronger and more sustainable than before. This will mean revisiting spending and savings habits, and, above all else, discarding past financial practices - investment and otherwise - that caused the house to come down crashing in the first place. n

Just within a day the price of 1 tola gold often goes up to Rs 5000-6000 because of huge demand

Haji Haroon Rasheed Chand, president of All Sindh Sarafa Jewellers Association

The government has announced its national money-saving programme under which it has been decided that the Pakistan Stock Exchange will close by 12 pm.

Defence Minister Khawaja Asif addressed a press conference flanked by Federal Minister for Information Marriyum Aurangzeb and Adviser to the Prime Minister on Kashmir Affairs Qamar Zaman Kaira after a meeting of the federal cabinet.

Asif said the decision to close the stock market by noon has been taken keeping in mind that people actually need the money that they are going to end up spending in the market.

“Stock markets around the world are designed keeping in mind the purpose of saving. Unfortunately, our market will not be facilitating that particular concept in the near future,” said the minister.

“If 20% of the potential investors are sent back home without putting money in the stock market, it will save Rs56 billion,” said the minister.

Asif also shared that the federal government was recommending switching off National Savings schemes alternately which will save about Rs4 billion.

“The government is also introducing e-money which will phase out the need for actual money. The government is negotiating with the companies to introduce this kind of money, which will give people the feeling of possessing a version of money that does not require any actual money to purchase,” the minister added.

Saying that the envisioned money-saving programme is at a national scale, the minister said that the government is reaching out to all four provinces to inform them about the policy and take them on board.

“We need to change our habits if we want to live within our means,” said the defence minister.

“And means means going to any means so as to keep hold of the existing means or fabricate the illusion of nonexistent means. You get what I mean?”