The generation that laid the foundations for the first 75 years of Pakistan is gone. It is time for the architects of the next 75 to step-up and show their mettle

In the next decade, something monumental will happen. Somewhere either in a noisy Lahore suburb, a quiet village in interior Sindh, or the walled city of Peshawar the last person that was a full-grown, legal, adult at the time of partition will breathe their last.

And with that, the generation that was to have built Pakistan will die out. Anyone that was at least 18 years old when Pakistan gained independence is currently 93. The young men and women we are talking about were to shape Pakistan. These were the first doctors, lawyers, civil servants, soldiers, farmers, businessmen, and political leaders that were native to Pakistan. Their efforts were to determine the course the fledgling nation would inevitably chart.

So let us, for a moment, take stock of the efforts of this near-extinct generation. In their very first mission it must be said that they have succeeded. Pakistan today is an undeniable reality and an inextricable part of the global world order. This longevity was not always guaranteed, and at least for the first decade the very existence of the world’s first independent Muslim state was doubtful.

Yet beyond this very obvious exercise in perseverance, there is little else to show for. Democracy has failed to take root, with military rulers exercising de facto and de jure rule for 32 years. More than half of the country was lost in 1971 with the independence of Bangladesh. Social turmoil, a bad relationship with debt, a boomand-bust economy, and a tired political system have all been part of the package.

In this time, there have been isolated moments of national and individual brilliance. Sporting achievements such as the 1992 cricket world cup and Pakistan’s dominance in the world of squash thanks to the three Khans comes to mind. Nobel Laureates such as Dr Abdus Salam and Malala Yousafzai have been sources of pride and inspiration. There have also been notable political victories, such as the passing of the 1973 constitution and the 18th amendment to that constitution in 2008. Yet for the large part, the highs have been few and far between while the lows have been abysmal and regular.

As we face the sobering reality of this lost generation, it is worth looking at what the future will look like. The men and women that laid the foundation of the first 75 years of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan are gone. We imagine very few

of them will be satisfied with where this country stands. Some of the problems they faced are the ones we continue to be saddled with. Others are unique global challenges such as climate change that those before us had the luxury of ignoring. It is now for this generation to make what they will of the next 75 years.

Pakistan’s Human Development Index value for 2021 is 0.544— which puts the country in the Low human development category—positioning it at 161 out of 191 countries and territories. Between 1990 and 2021, Pakistan’s HDI value changed from 0.400 to 0.544, a change of 36.0 percent. The great irony of this, of course, is the fact that this index on which Pakistan finds itself slipping fast was in fact developed by a Pakistani — Dr Mahbub ul Haq, who created HDI in 1990. The index was then used to measure the development of countries by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP).

Meanwhile, on the Gender Development Index (GDI), which measures gender gaps in achievements in three basic dimensions of human development: health, education, and standard of living, shows a massive gap. The 2021 female HDI value for Pakistan is 0.471 in contrast with 0.582 for males, resulting in a GDI value of 0.810, placing it into Group 5, making it part of an unenviable group of countries that includes Ethiopia, South Sudan, and Afghanistan. Meanwhile on the Gender Inequality Index, Pakistan ranks 135 out of 170 countries.

In 2021, the World Justice Project’s Rule of Law Index ranked Pakistan 130 out of 139 countries. Pakistan ranked second-last in South Asian countries behind the likes of Nepal, Sri Lanka, India, and Bangladesh. Only Afghanistan was ranked lower. In particular, the report showed Pakistan doing badly in the areas of corruption, fundamental rights, order and security and regulatory enforcement.

Just this year, Pakistan fell by 12 places on an index of media freedom. Pakistan was 145th on the 2021 index and fell to 157th on a list of 180 countries in 2022. The report noted that despite changes in political power, “a recurring theme is apparent: political parties in opposition support press freedom but are first to restrict it when in power”. The report also claimed that the “coverage of military and intelligence agency interference in politics has become off limits for journalists”.

On the economic front, matters have not been much better. Earlier this year, Pakistan’s inflation accelerated for a sixth straight month to hit a fresh record in August, with the deadly floods risk jolting prices further. Earlier this month, with

None of the indicators paint a pretty picture. Human development in Pakistan has taken beating after beating. Political turmoil has left the country without any stable government, making the government of Pakistan a dodgy business partner. Consistent security failures and the inability to protect our own citizens means that the possible potential of Pakistan as a tourist destination, something other South Asian countries like Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam, and Indonesia have done successfully, has been squandered.

And on top of all of this, Pakistan now faces the major crisis of climate change — which is perhaps the single most relevant and dangerous threat to our national well-being. According to the Center for Global Development, developed countries are responsible for 79% of historical carbon emissions. Yet studies have shown that residents in least developed countries have 10 times more chances of being affected by these climate disasters than those in wealthy countries. Further, critical views have it that it would take over a 100 years for lower income countries to attain the resiliency of developed countries. Unfortunately, the Global South is surrounded by a myriad of socio-economic and environmental factors limiting their fight against the climate crisis.

This has been illustrated in painful detail this year, when climate change resulted in a gargantuan increase in the amount of monsoon rainfall that Sindh and Balochistan have seen this year. The two provinces saw the highest amount of water fall from the skies in living memory, recording 522 and 469 per cent more than the normal downpour.

All in all, according to the latest report of the Post-Disaster Needs Assessment (PDNA), Pakistan needs at least $16.3 billion for post-flood rehabilitation and reconstruction. The PDNA report, released by the representatives of the government and the international development institutions, calculated the cost of floods at $30.1 billion – $14.9 billion in damages and $15.2 billion in losses.

Earlier this year, an event by the name of #TheNext75 was organised by the Engro Corporation under their new talks@engro platform. The platform is an interesting initiative from a corporation that is considered a responsible organisation. The platform aimed to bring thought leaders, changemakers, and futurists to share ideas and personal stories that may help to solve some of Pakistan’s most pressing issues.

During the #TheNext75, a host of speakers did exactly that. There was, of course, a great deal of hope. Engro’s CEO Ghias Khan for example claimed that Pakistan needs only look at its own past for some much needed inspiration — pointing towards the many successes that the country has had. Former finance minister Asad Umar made a point of saying Pakistan was a horse worth betting on. Yet at the same time, others like IBA’s executive director Dr S Akbar Zaidi were blunt in their assessment — that there is a pretty big mess that needs cleaning up.

This week’s issue of Profit looks directly at what 2097 will look like for Pakistan. Using the talks delivered at the #TheNext75 event, we look at Pakistan’s development in terms of gender equality, economic growth, success in sports, the arts, and many other issues. The reality is bleak.

The generation of Pakistanis that took the reins in 1947 had a rare shot at a clean-slate. The generation that will now take over for the next 75 is not so lucky. The baggage that comes with project Pakistan is excessive, and some of it will have to be shed. Concentrated efforts need to be made to enshrine democracy, to uplift disadvantaged groups, to promote education, and to protect and empower the only thing that has kept Pakistan alive — its people.

In these seven and a half decades, it has been the people of Pakistan that have given it its pride. Moments of unparalleled individual brilliance that have stitched and brought the nation together. The role of the state has regularly been that of an absentee (and at times abusive) parent. The dogged resilience of the people of Pakistan has kept us afloat. However, there is always a limit. As we look towards the next 75 years, we hope that this undue burden will be lifted.

Pakistan has come a long way in the past 75 years. It can go even further if we dare to dream

For

the future, we need only look at the past

What will Pakistan look like in 75 years? There is one version of events that, even if ambitious, can serve as an aspiration at the very least. A future in which Pakistan is in the “top 10 countries in the world” list for not just military strength and population growth, but also for economic prowess and social diversity. A Pakistan that may even be in the top three tourist destinations in the world. A Pakistan that is up high on the medals table at the 2096 Olympics.

This may sound like a utopia, but 75 years is a long time.

And as fantastical as this may sound, these visions of the future are not unprecedented. They are in fact strongly tied to the past and rooted in our history. We don’t have to look farther than home to find this inspiration. Pakistan has a history of economic success, social justice, and outstanding achievement in sports and the arts that should bolster the confidence in this dream.

After all, at this significant moment in our history, we are looking at what the next 75 years will be like. And what better place to take both inspiration and stock of how that will go than by going 75 years back.

affordable and accessible education. A prime example of this is Mushtaq Chhapra, the founder of The Citizens Foundation (TCF) — one of the largest, privately-owned networks of low-cost, formal schools in Pakistan, operating around 2000 school units.

There’s a longer history here.

In 1975, a woman decided to open a montessori at her house. Nasreen Kasuri is now the proud owner of the Beaconhouse School System — the largest and oldest private school system in the country, that has educated more than 300,000 students. While the healthcare system seems bleak, we also have the example of a commission agent who established the largest private ambulance network in the world. Indeed, Huffington Post celebrated Abdul Sattar Edhi as the greatest living humanitarian of our times. Another gentleman doctor, Dr. Adibul Hasan Rizvi went to England 40 years ago, got inspired by the NHS (National Health Service) there, and founded SIUT (Sindh Institute of Urology and Transplantation) in Pakistan. SIUT offers free and equal treatment to all its patients.

The column has been adapted from a talk delivered by Ghias Khan at the #TheNext75 event organised by the talks@ engro platform. Ghias Khan is the CEO of the Engro Corporation

The existence of the state of Pakistan itself is the product of lofty dreams. The country is the labour and product of unrealistic dreaming. Upon achieving statehood in 1947, Pakistan inherited a meagre 29 out of 900 industrial units that existed in the subcontinent. The economy was in an abysmal state. However, over the past 75 years Pakistan has emerged as the 24th largest economy in terms of purchasing power parity. Our minimal GDP is 44th in the world. On the back of nuclear advancement, our military is a force to be reckoned with. The economy has grown 125 fold and the average income per person 21 fold.

Pakistan also boasts one of the progressive legislations and promises a diverse society. This is exemplified by the recent bill passed by the parliament in the recognition of the Khwajah Sirah community. This fundamental human right is unacknowledged by most developed countries. Though there’s a long way to go in gender empowerment, Pakistan is also the first Muslim country to champion a female prime minister.

Furthermore, there is solid hope insofar as education and healthcare are concerned. Even though 24 million children in Pakistan don’t go to school, a lot of effort is being channelled into

Pakistan has a proud history in science and technology also, as depicted by Mohammad Abdus Salam’s breakthrough achievements. He was a young boy from Jhang who received a scholarship to study at Government College Lahore. At the age of 24, he received a scholarship from the University of Cambridge and completed his PhD there. He eventually won the Nobel Prize in Physics. He attended the ceremony dressed in a black sherwani, white turban and khussas.

Pakistan has a glorious history in sports and arts also. Under the leadership of Imran Khan in the 90s, the cricket team never lost a test series to the West Indies and stood unfazed even in the most challenging circumstances. It was this resolve that culminated in the destinies of the cornered tigers in Melbourne. These proud achievements extend in the field of arts also. The foremost example of this is the two time Oscar winner and director of Ms Marvel, Sharmeen Obaid Chinoy. Moreover, Maula Jatt, despite being made in limited budgets, is rapidly becoming a global hit.

As individuals, institutions and a nation, we can’t let the lack of resources or limitations in our ecosystem define or dictate our dreams. The need of the hour is to convert individual brilliance into institutional success. Again, this is not a novel claim This was echoed by Allama Iqbal decades ago: “Nehin Tera nasheman qas-re-sultani ke gumbad par Tu shaheen hai, basera kar paharon ki chahaton main”

There is much that Pakistan has going for it. But faith in it will be repaid

Pakistan was created under unique circumstances, without natural and ethnic boundaries and any concept of nationhood. It’s the only country in the world built on the back of democratic processes. The country faced dire conditions, and many experts predicted that it wouldn’t last more than six months. The collective literacy rate was 3% as the colonial education system was only designed for the elite. Pakistan had inherited no industry, barring a cement factory and a few textile units. Both East and West Pakistan had a combined total of 29 industrial units. The country that was never meant to survive now celebrates 75 years of existence and is flourishing.

INSEAD and Berkeley. I have yet to come across a talent pool the kind I find in Pakistan, or in the Subcontinent at large. This can be credited to the mixing of races which has created this exceptional talent pool, similar to the melting pot of cultures that we observe in the USA. The remarkable human talent along with institutional foundational blocks and natural endowments are all there to give another flourishing 75 years. Pakistan will indeed be a success story, it’s the best bet one would make. It will leapfrog from agricultural to post-industrial and knowledge-based society.

The column has been adapted from a talk delivered by Asad Umar at the #TheNext75 event organised by the talks@engro platform. Asad Umar is the former CEO of the Engro Corporation as well as a former finance minister.

Though there has been subsequent improvement in Pakistan’s commerce and economy, a nation’s success is not only limited to this. In the 21st century, the markers of a successful nation entail certain foundational blocks, such as democracy. In a multi-ethnic society such as that of Pakistan’s, democracy is the only way to maintain social cohesion. Pakistan clearly has the institutional provisions to grow and prosper further. Throughout its politically turbulent history, there had never been a successful civilian to civilian transfer of power. However, this finally changed two elections ago. Pakistan has finally devised strategies to raise consensus for national issues. The legal system, though fraught with controversies such as the Lawyer’s Movement, has birthed a judiciary that is substantively more independent compared to that of 20-25 years ago. Relations between citizen and state are underpinned by tensions, and the role of governance needs to be redefined. However, the institutional blocks are there to positively transform this.

Pakistan is also rich with natural endowments to sustain its population. There’s diversity of climate and plentiful rivers. Pakistan has the ability to generate its own food and power. This population is also an asset that can facilitate its development. I have worked with some of the best minds across the world, ranging from my tenure at the number one Fortune 500 company, ExxonMobil and the joint venture with Mitsubishi (again ranked number one on Fortune 500) to programs at Harvard, Oxford,

This can be attributed to the large human population and we can already detect signs of this. Pakistan is amongst the 5 big nations of the world working in the freelancing landscape and in the spheres of information and knowledge. Once we invest in the youth of Pakistan and provide them with a level playing field that is characterised by rule of law, mature democratic processes, and freedom of expression and speech, they will showcase the ability to compete with and win against the best in the world. It is also important to supplement this with a competition-based market system. Since Pakistan does not have a transparent democratic system, entrepreneurs face structural setbacks. Real estate has emerged as the most lucrative business as it’s not based on entrepreneurial and innovative skills, but networking and the ability to form connections. It is, therefore, imperative to make our institutional conditions ripe for entrepreneurship. Young entrepreneurs are rapidly emerging in the knowledge-based economy. 2021 was a phenomenal year for Pakistani startups, particularly tech startups. It raised more money from the global market and the world’s best investment companies than it had in the past six years combined. IT exports jumped to 47% in the initial 8-9 months, and continued to grow further by 32%. We were indeed at the tipping point.

When I was younger, more people sought to leave the country as Pakistan was struggling at the time. However, our nation has finally emerged and found its destiny and voice. Our modern generation will be the most successful. Those who bet on Pakistan will be richly rewarded.

If Pakistan is to progress, we must empower our women and make peace with who our neighbours are.

As an economist who looks at data, facts, numbers and trends, the news is bad. Pakistan will not be a superpower in the next 75 years. Two months ago, 30 million people were displaced in floods. Nobody talks about this. Pakistan represents a story of decline, and we have figures that are suggestive of this. Pakistan slipped in the human development index: from 154, it is now at 166-167 out of 189 countries. While countries are progressing, we are decaying and it’s imperative that we acknowledge that. In the 90s, we were considerably ahead of Bangladesh and Nepal in terms of human development but now we’re regressing. Pakistan has the lowest life expectancy and literacy rate in South Asia. It is only progressing in population growth, with the highest population growth rate. Bangladesh, the basket of the world in 1971 is today being talked about as the next China. Pakistan on the other hand is being perceived as the next Afghanistan, Sudan or some other country which people can’t even recognise on the map.

Pakistan has the most striking figure in gender parity, where it’s ranked as the second worst country in the world. What good can nuclear weapons achieve in a country where women are treated the way they are? Pakistan has some of the most accomplished women, such as the two-time Oscar winner, Sharmeen Obaid Chinoy and the young Nobel prize winner, Malala Yousafzai who’s not even allowed to enter the country. We as fathers, brothers, husbands and society as a collective are responsible for this.

The column has been adapted from a talk delivered by Dr S Akbar Zaidi at the #TheNext75 event organised by the talks@engro platform. Dr Zaidi is the executive director at IBA in Karachi.

We study ‘path dependence’ in economics, which means that one moves ahead from where they come from based on their resources. However, it’s important that we shift our gaze from the past to the future. In order to be on the map 75 years from now, the only solution is better treatment of women. Men alone are useless. Women are the future. The normative assumption is that women empowerment is a Western concept. However, we have the example of Muslim countries such as Bangladesh, Turkey, Indonesia and Malaysia, where women receive education, rights and protection. The more women are deterred, the more we regress as a nation. In fact, we won’t be able to progress further in the next 10 years, let alone 75 years without empowering our women.

Secondly, it is crucial that we befriend our neighbouring countries, India and Iran. Our neighbourhood can’t be changed — we’ve had this for 75 years and will continue to do so. It’s important to maintain cordial relations with India. It has the highest GDP growth rate and there is much to be learned from India. Integrating economic ties would be highly productive for Pakistan. China too remains highly dependent on a country that it doesn’t even recognise — Taiwan. It continues to trade with Taiwan and procures its electronic chips. A similar case can be made for Iran. Due to staggering debts, Saudi Arabia, USA and the IMF are able to exert pressure on Pakistan, as a result of which we can’t import oil from Iran. The extent of debts Pakistan is under is utterly shameful and questions Pakistan’s autonomy and independence as a nation . Regional economic integration is key. The European Union is a great example of this. Britain made a huge mistake by exiting the EU. This is not the time for jingoism and nationalism. It’s more important to think of where we are, maintain good economic relationships with our neighbours, and learn from them. To conclude, without women Pakistan has no future. It is necessary for men to step aside and promote women in all fields- arts, sports, science and technology, education, industry etc. Additionally, we can’t continuously snub our neighbours. We better get our act together as a country if we wish to survive the next 75 years.

By Abdullah Niazi

By Abdullah Niazi

More than 75 years ago, speaking at the Jinnah Islamia College in Lahore in 1940, Quaid e Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah made one of his most famous speeches. “I have always maintained that no nation can ever be worthy of its existence that cannot take with them their women. No struggle can ever succeed without women ever participating side by side with men”, he said, addressing a crowd of young, female, students.

In Jinnah’s speech, he presented the vision of a nation whose women would stand side-by-side with its mens as equals. It was this post-war generation that was to be emancipated. “You young ladies are more fortunate than your mothers. You are being emancipated. Men must be made to understand and made to feel that woman is his equal and that woman is his friend and comrade and they together can build up homes, families and the nation”.

The words of the Quaid seem radical-

ly progressive by today’s standard. That is because in the 75 years since Pakistan came into existence, the nation’s women have been ignored, sidelined, shamed, vilified, and disadvantaged beyond belief. This, in turn, has not just resulted in a rot setting into our social fabric but great economic disadvantage.

“The most striking figure which shocks and hurts me the most is that in gender parity we are the second worst country in the world. Who wants a nuclear weapon when our women are treated the way they are?” says Dr S Akbar Zaidi, executive director at IBA in Karachi, when he took the stage at the #Next75 event

organised by the talks@engro platform. “Without women being active participants, Pakistan has no future. They have to come first. And the most important thing we can do is promote them. For men to get out of the way.”

During his talk, Dr Zaidi attributed a lot of Pakistan’s problems to the great chasm of disparity that has appeared between men and women in Pakistan. It makes sense. When half of a country’s population is disadvantaged and taken out of the equation, the country will find it hard to progress. This was Jinnah’s point as well when he said no nation could progress without its women being active participants.

More than 75 years later, that is yet to be achieved. Will it be 75 years from now? We hope so. Because if it doesn’t, it will mean disaster.

he news is very bad. I’m not going to come here and tell you Pakistan will be a superpower in 75 years because I look at data, trends, facts — and the news isn’t good,” Dr Zaidi said during his session at the talks@ engro platform. “In the past few years, Pakistan has slipped from 154 on the Human Development Index to 167 out of 189 countries. Other countries have been progressing while we have been decaying. I don’t say we have been declining because this has been decaying. And the most striking figure has been the fact that Pakistan is second worst in the world in terms of gender parity”.

Dr Zaidi makes an important case. Just look at it this way. The data on Pakistani women’s rising economic power is staggering. The female labour force participation rate rose from under 16% in 1998 to a peak of 25% in 2015 before declining slightly once again to 22.8% by 2018. That means there are millions of women who are currently working who might not have been, had labour force participation rates for women stayed the same.

The total number of women in Pakistan’s labour force – earning a wage outside the home – rose from just 8.2 million women in 1998 to an estimated 23.7 million by 2020, according to Profit’s analysis of data from the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. That represents an average increase of 4.9% per year compared to an average of just a 2.4% per year increase in the total population. In short, the growth in the number of women entering the labour force is more than twice as high as the total rate of population increase.

All of those women now in the workforce have more purchasing power than ever before. Women have always had some measure of purchasing discretion for their households. But now, with their own incomes, they have more ability than ever before to make discretionary purchases for themselves, rather than just making decisions for their households. However, despite this increase in participation in the labour force and contribution to the economy, the development indicators for women in Pakistan keep falling. In the 75 years since partition, Pakistan has continued to regress. According to the UN’s data on women, at least 25% of vital legislation and legal frameworks that promote, enforce and monitor gender equality under the SDG indicator, with a focus on violence against women are not in place. The adolescent birth rate is 54 per 1,000

women aged 15-19 as of 2017, up from 46 per 1,000 in 2016. As of February 2021, only 20.2% of seats in parliament were held by women. In 2018, 16.2% of women aged 15-49 years reported that they had been subject to physical and/or sexual violence by a current or former intimate partner in the previous 12 months. Also, women and girls aged 10+ spend 18.8% of their time on unpaid care and domestic work, compared to 1.8% spent by men.

There is also a serious data crunch. As of December 2020, only 49.1% of indicators needed to monitor the SDGs from a gender perspective were available. In addition, many areas – such as gender and poverty, physical and sexual harassment, women’s access to assets (including land), and gender and the environment – lack comparable methodologies for regular monitoring. Closing these gender data gaps is essential for achieving gender-related SDG commitments in Pakistan.

This means that Pakistani women are in a situation where they are contributing to the economy, their participation in the labour force is at an all time high despite the many barriers to entry they face, and none of this effort has been reflected in the development of women themselves.

Just look at the data on financial inclusion. We have already mentioned how much the female participation in the labour market has increased and their purchasing power as well. One of the biggest issues in Pakistan’s economy, which has also been highlighted by the State Bank and others, has been financial inclusion. A vast majority of our population is

unbanked. This means that most Pakistanis do not have access to financial services, instruments, and are severely behind the curve.

In this, women are a major component of the unbanked population. When it comes to financial inclusivity, Pakistan ranks close to the lowest rung of the ladder as a majority of its population has no access to formal financial services, savings, credit, insurance or even the knowledge required to be able to make intelligent pecuniary choices. The country is part of a seven-nation group that is home to more than 50% of the world’s unbanked population.

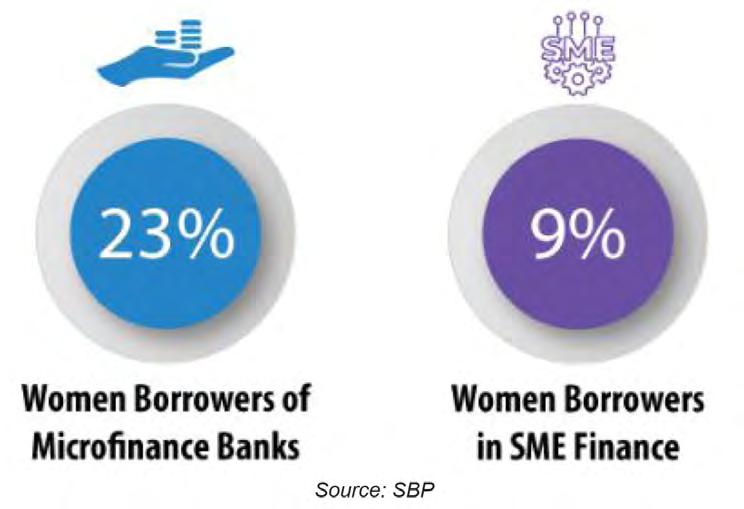

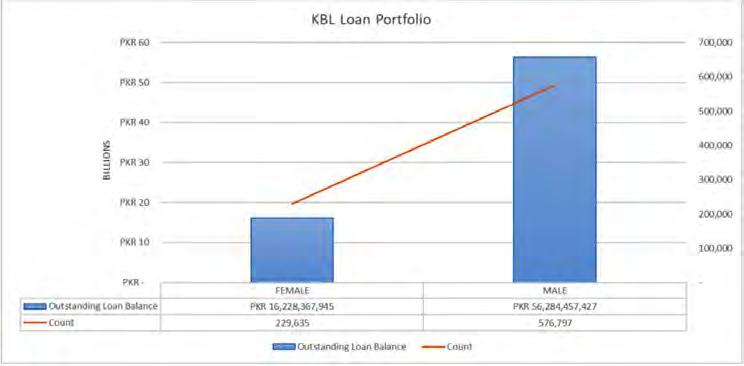

It is estimated that microfinance services currently only serve 11.5 percent of a potential market of 27 million people. Women in Pakistan have even greater barriers in accessing finance. Nationwide only seven percent of women hold a bank account. In 2019, only three percent of SME loans and nineteen percent of microfinance loans were distributed to women.

KMBL, the largest Microfinance Bank in the country, had a closing portfolio of around 72 billion in December 2021 out of which only 22% pertained to female lending. The figure is closer to 20-21% for Mobilink Bank, which claims to be the country’s largest digital bank. As per SBP, the industry average figure is around 23%.

The majority of unbanked adults continue to be women even in economies that have successfully increased account ownership and have a small share of unbanked adults. In Türkiye, for example, about a quarter of adults are unbanked, and yet 71 percent of those unbanked adults are women. Brazil, China, Kenya, Russia, and Thailand also have relatively high rates of account ownership, compared with their developing economy peers, and yet a majority of those who are still unbanked are women. Things are not much different in economies in which less than half the population is banked. For example, in Egypt, Guinea, and Pakistan women make up more than half of the unbanked population.

And the brunt of this is further faced by women in the rural areas. Access to finance remains very scarce in rural areas. Smallhold-

er farmers are particularly poorly served: 29 percent are entirely excluded and most of the remainder have only limited access to formal finance. Instead, farmers rely on traders and moneylenders to meet their credit needs, often tied to sale of inputs and with repayments tied to future sales of farmers’ produce. Commercial banks are hesitant or unable to provide financial services to less lucrative rural markets.

And this is despite the fact that women have proven themselves to be better at borrowing. According to the Women’s Financial Inclusion Data Partnership, there will be an

estimated 32% gender gap in access to formal financial services by 2030 in Pakistan, while the country’s ‘estimated annual financial services product revenue potential in women’s market’ is $652 million. This is partly because “women are paying back loans at greater rates than men and they are also great savers,” said Inez Murray, the CEO for the Financial Alliance for Women.

There is a simple answer to this: affirmative action. When a particular group of people have historically, as proven by hard data in this case, been disadvantaged and discriminated against for whatever reason they need to be uplifted to ensure an equitable society.

“Women are the future, and that means men need to make way for them. Bangladesh, Turkey, Indonesia have progressed because women get education, rights, protection. All women and the men standing with them need to move forward. This is what our future depends on. If we are unable to do this, then forget the next 75 years, we won’t even be able to make 10 years worth of progress,” Dr Zaidi said at the #Next75 event. n

Ramiz Raja’s comments at the talks@engro platform have reaffirmed a commitment to building systems and following processes. But will it succeed?

It’s been a tough year for Pakistan cricket. The team reached the finals of both the Asia Cup and the T20 World Cup only to be trounced in the finals is perhaps the strongest it has been in decades. Just go back a decade and put this team in its context.

In 2010, Pakistan cricket had been rocked. Already exiled from their home after the terror attacks on the Sri Lankan cricket team’s tour bus in 2009, they were now also ostracised as cheats. In many ways, the trio of Salman Butt, Muhammad Asif, and Muhammad Amir were a representation of Pakistan itself. Butt — the erudite middle-class prodigy that went to Beacon House and played his club cricket in Lahore’s Model Town instead of Iqbal Park. Asif — the country boy that had magic in his wrists. Amir — the wunderkind that was supposed to be the next Wasim Akram.

Three different brands of Pakistanis, three different stories, all corruptible. What followed was a slow, arduous, rebuilding period. In the twelve years since, Pakistan has gone on to win the ICC Test Mace, the Champions Trophy, launch the Pakistan Super League (PSL) and have Australia, England, and South African all tour Pakistan.

“What you see in this Pakistani cricket team is a small Pakistan. When we look at this team it has a lot of potential, and I think the most important thing is that it has remained upwardly mobile, and that’s why I’m hopeful for the next 75 years”, said PCB Chairman Ramiz Raja in his talk at the recently launched platform “talks@engro”.

That is, perhaps, the most important transformation in this time. But how did the Pakistan cricket team manage to pull this off? According to Ramiz Raja, it is a question of building systems and getting your processes right. “I think you can achieve greatness, and to achieve greatness, you need a strong thriving system and a clean environment”.

That is what the PCB has been trying to build. The quirk of human nature that brings out the best in people and communities during times of hardship has been at play this whole time. The important thing will be to stay the course.

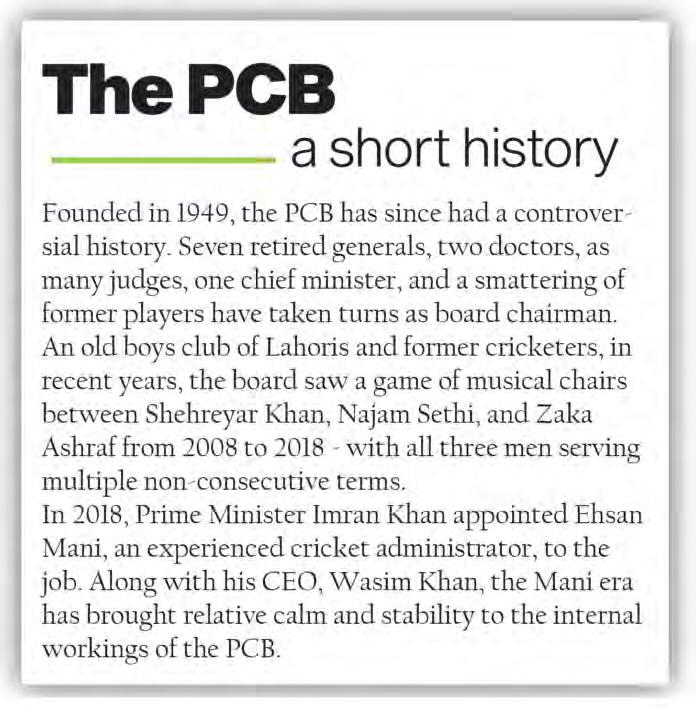

Mention the Pakistan Cricket Board (PCB) to a cricket fan and you are likely to get a snarl, a glare, and either a string of profanities unfit to publish, or if you are lucky, a brusque request to change the topic. If you

ask someone that does not follow cricket, you will most likely receive a shrug and a non-committal comment about hearing that the board is inefficient.

What you will not get, is an understanding of what exactly it is that the PCB does. Most people that pay attention to the cricket board are cricket fans, and the only reason they care is that the board is responsible for selecting teams, naming captains, choosing coaches, organising tours, and making the case for Pakistan cricket internationally. The part that usually gets overlooked is that the PCB is supposed to run and make money like a corporation.

The idea is that the PCB should make money so that they can then invest back into the game of cricket. So if in any given year the board makes a big profit, they then have more spending power to invest in facilities, salaries, foreign coaching staff, marketing and most importantly – the players.

In the years before, the PCB has been an organisation that has been symbolic of everything wrong with Pakistan – stubborn, rooted in all the wrong traditions, prone to political favouritism, sluggish, and in desperate need of reform and modernisation.

In 2020, the PCB declared an after tax profit of Rs 3.8 billion, and revenues of close to Rs 10 billion. Cricket in Pakistan is worth millions of dollars. After all, it is practically the only sport in the country with a massive television audience that has very little else to do in terms of entertainment. In 2021, the PCB’s expenditures increased significantly and its income fell but the PCB remained largely profitable. And a big part of that has been the board, and indeed Pakistan’s, insistence on surviving and figuring out how to thrive despite the extra challenges it faces. A massive part of that has been the PSL.

There are two main sources of income for a cricket board. The first is the International Cricket Council (ICC). The ICC hosts international tournaments like the Cricket World Cup and the T20 World Cup or the Champions Trophy, which attract cricket fans from around the world. From these tournaments, through gate receipts,

broadcasting rights, and sponsorship deals, the ICC makes billions. In the projections for ICC’s 2015-23 cycle, the council is supposed to make up to $3 billion, which is then distributed through the different cricket boards. Larger boards that bring in larger television audiences like India and Australia get larger shares. Currently, the ICC is giving around $16.5 million to Pakistan annually until 2023.

This leaves countries like Pakistan vulnerable to having no source of income other than what they get from the ICC. In Pakistan’s case, with very little home cricket being played, Pakistan was unable to capitalise on the money that is generated from home series. To fix the problem, they came up with the PSL.

“The PCB gets most of its money from the ICC handouts and from tours. The rest of it comes from PSL franchise fees, PSL ground branding, media rights within the territory, and global digital content exploitation both globally and in Pakistan,” says cricket historian and anchor Dr Nauman Niaz. “The PSL has now become a game changer and is the hallmark of the PCB”.

The PSL has possibly been one of the best business decisions that the Pakistan Cricket Board (PCB) has made in its history. The league provides the board with a steady revenue stream each year, it has reopened the doors of international cricket in Pakistan, and has allowed the PCB to form connections with and sign major deals with international broadcasters.

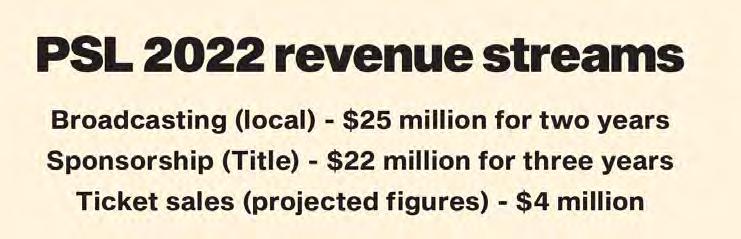

And it is worth some serious money. Every year the tournament brings home the bacon for the PCB by selling tickets, selling sponsorships, and selling the broadcasting rights to the matches. This year alone, the cricket board sold the local broadcasting rights for the tournament to a consortium of ARY and PTV for the hefty price of $25 million for a two year period. Similarly, the title sponsorship, which has belonged to HBL since the beginning of the tournament, was sold to them again until 2025 for nearly $22.5 million (and this is only the title sponsorship, which means the revenue from other sponsors has not been factored in.) And while the PCB does not have its earnings from this year’s ticket sales, they managed to rake in upwards of $2 million back in 2020.

The first time that it became apparent

What you see in this Pakistani cricket team is a small Pakistan. When we look at this team it has a lot of potential, and I think the most important thing is that it has remained upwardly mobile, and that’s why I’m hopeful for the next 75 years

that the PSL could be worth the big bucks was back in 2015, when the PCB sold the rights to five franchise teams that would play the tournament for $93 million for a 10 year period. The most expensive team to be sold was Karachi Kings for $26 million, followed by Lahore Qalandars for $25 million, Peshawar Zalmi for $16 million, Islamabad United for $15 million, and the Quetta Gladiators for $11 million. Since the teams were sold for a 10-year period, the total cost was payable over 10 years in the form of a yearly franchise fee equivalent to 10% of the team’s value.

The growth of the tournament can be measured by the case of Multan Sultans. The sixth team added to the PSL only two years after it started, the rights to this franchise were significantly more expensive. Late by just two years, the franchise was auctioned off for a whopping $41.6 million – and that too only for an eight year period to the Schon group. However, the $5.2 million franchise fee was too much for Asher Schon to keep up with, and after one year the PCB terminated the Schon group’s ownership of the Multan Sultans on good terms. Even this, however, did not stop the price of the team from rising even more. Initially sold for a $41.6 million price tag for eight years, the team was now sold for $45 million for seven years to Aalamgir and Ali Khan Tareen. That meant the Tareens would be paying an astonishing yearly franchise fee of $6.35 million each year to keep ownership of their team.

This, of course, is the bigger problem.

One of the major reasons that the PCB has had to find these innovative solutions to stay afloat has been the cold shoulder they have gotten from India. With a population of over a billion people, the Indian television audience is huge, and can make or break the income of cricket boards, all of whom are keen to have India tour them so that their vast population tunes in to watch their team play.

The latest snub has been when the BCCI’s secretary Jay Shah, also the son of India’s home minister and Prime Minister

Modi’s right-hand man Amit Shah, announced that India would not be travelling to Pakistan for the Asia Cup. But for Pakistan, this was nothing new.

India is the de-facto head honcho in world cricket, controlling the largest streams of revenue in the game, and providing the International Cricket Council (ICC) with an overwhelming majority of its cash-flow. Thanks to this financial muscle, almost every cricket board in the world, including other big fish like England, Australia, and South Africa, depend heavily on the rich spoils that they get from bilateral series with India. On top of this, the BCCI also controls the Indian Premier League (IPL), the tournament that put cricket on the map as a money making sport and

Pakistan has been living this reality since 2008, so it isn’t that big of a deal anymore. The way I’ve started looking at it is that Pakistan has shown there is a way to thrive without playing against India. Most boards think you aren’t making money if you aren’t playing India. We aren’t one of the biggest boards in the world, but we are easily the fourth biggest and that is without any bilateral ties with India

Sammiudin, senior editor at Cricinfo

India is not going anywhere. The highest growth rate in terms of GDP will be India. We can’t even play cricket with them. Ramiz Raja is sitting right here. I think even if we just play cricket there and get them to play cricket in Pakistan half our problems will be solved right there. We don’t play with them. Movies don’t come here. Countries aren’t going to move, people will and we need to learn to deal with them

which recently sold its media rights for the 2023-27 cycle for a jaw-dropping $6 billion.

Playing India is usually the most important part of any cricketing nation’s calendar. According to a recent report published in The Guardian, India’s 10-match tour of South Africa last winter, for instance, was worth £80m to the hosts. Similarly, when India pulled out of a test match in England last year, it left the England Cricket Board (ECB) with a gaping £40 million hole in their finances. Even Australia

depends on bilateral series with India, and the two countries play each other more often than any other two teams.

During the recent talks@engro event, even Dr S Akbar Zaidi, executive director of IBA, alluded to this reality. “India is not going anywhere. The highest growth rate in terms of GDP will be India. We can’t even play cricket with them. Ramiz Raja is sitting right here. I think even if we just play cricket there and get them to play cricket in Pakistan half our problems will be solved right there”, he said.

Some would argue that India has earned this position. Over the years, they have managed to utilise their massive television audience well to turn profitable. Their biggest stroke of genius was the IPL, which pumped large amounts of money into cricket in India and perhaps more importantly proved that cricket as a game could be, as legendary Indian batter Rahul Dravid would put it, a four letter word that begins with S and ends with Y.

{Editor’s note: At a press conference talking about the bowling of the Pakistan team, Dravid described it as “a four letter word beginning in S and ending in Y. The word he was thinking, of course, was sexy.}

And Pakistan has had to learn to live without these rich spoils. “Pakistan has been living this reality since 2008, so it isn’t that big of a deal anymore. The way I’ve started looking at it is that Pakistan has shown there is a way to thrive without playing against India. Most boards think you aren’t making money if you aren’t playing India. We aren’t one of the biggest boards in the world, but we are easily the fourth biggest and that is without any bilateral ties with India,” says Osman Sammiudin, senior editor at Cricinfo. “During this time the PCB built the PSL. The board makes money off of it, and for a while now Pakistan’s accounts have been showing a net profit. This is the status quo for Pakistan and they’ve made it work.”

Most of us won’t be around to see it. It is honestly a wonder what cricket will look like in that much time. What new formats, new kinds of balls, equipment, rules, and quirks the game will have picked up in all this time. What we do know is that if Pakistan is to have a role in that set-up, it will have to step up and keep up. “If you have the processes done right, and if you believe in yourself and if you’ve got clarity, I think you can achieve greatness,” said Ramiz Raja during his talk at talks@engro. n

The PCB gets most of its money from the ICC handouts and from tours. The rest of it comes from PSL franchise fees, PSL ground branding, media rights within the territory, and global digital content exploitation both globally and in Pakistan

Dr Nauman Niaz, cricket historian

Dr Nauman Niaz, cricket historian

By Profit

By Profit

There were two women that took the stage at the #Next75 event recently organised by talks@engro. Both have done firsts for Pakistan. Both belong to vastly different fields. And both talked about very similar themes in their discussions. The first was Pakistan’s Oscar-winning prodigy Sharmeen Obaid Chinoy. The second was international football star Karishma Ali.

Their talks, and in turn their stories, are telling of the state of their professions and the unique difficulties faced by women in these positions. All of these problems are emblematic of the issues that Pakistan has faced in its 75 years of existence. As we look towards the next 75, there is a long, difficult road ahead.

In 2010, Shermeen Obaid Chinoy won her first Emmy. It would not be until another two years that she would win her first Oscar award. Of course, that was not the only major milestone for Pakistan’s entertainment industry that year. This was also the year that Bollywood blockbuster 3 Idiots was released in Pakistan at almost the same time as its Indian release, going on to generate $1 million in revenue in Pakistan alone, then a record for a Bollywood movie (since then shattered by BajrangiBhaijan, which grossed approximately $3.5 million in Pakistan).

In the years that followed, Bollywood movies became the main offering of Pakistani cinema screens, accounting for the bulk of box

office receipts in the country, by most anecdotal evidence (there are no publicly listed cinema companies, so audited financials are not publicly available). How was this a major turning point for Pakistani cinema? Lollywood was revived because Bollywood made a comeback on Pakistani cinema screens.

The year 2010, which is when 3 Idiots took in most of its revenues, was arguably one of the worst in Pakistani cinema history, effectively the nadir that marked the end of several decades of almost consistent decline in virtually every metric of health for Pakistani cinema.

According to data from the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, the number of films released in any language across the country fell to 18, the lowest recorded number for at least the last three decades. The number of cinema screens nearly halved that year, from 203 to

This little girl in 2006 decided to sit and watch the FIFA Men’s World Cup with her father somewhere in a village in Chitral. But the most important part is of her father, who sat there explaining the football game to her, all the rules, naming the players, but one important thing that he never did was that he never mentioned that it was a men’s game, even though there was nothing about women’s sports being shown on TV

Footballer Karishma Ali speaking at the #Next75 event of talks@engro

So what might the distant future look like?

107, and would continue to fall to its all-time low of 80 through 2012. And the seating capacity of Pakistani cinemas fell to a multi-decade low of 37,650.

But once Indian moves began to make money for Pakistani cinema owners, the number of screens, the number of seats, and therefore the number of movies began to grow. And, unlike past film booms, this time, the revenue earned by movies began to skyrocket as well.

Since then, the Pakistani film industry has been seriously bolstered. And with Indian movies banned in Pakistan sporadically, it has given the industry a chance to produce more and better movies than ever before. But what could the future look like for the film industry? A look at this past year is telling.

The Legend of Maula Jatt has done a lot of unprecedented things: an ambitious concept, a massive budget, record-shattering revenues, and gripping execution. Maula Jatt, just for background, is a uber-masculine, testosterone-driven Punjabi action hero/anti-hero who first appeared on screen in 1979. The movie and its characters were based loosely on a novelette by Ahmed Nadeem Qasimi called “Gandaasa”, says critic and journalist Rafay Mahmood. So when word came out that Lashari was taking this on, expectations began to rise. It took 10 years for Jatt’s re-invention (it’s not a “remake” Lashari insists) to be completed and for the project to see the light of day, producers say.

Closer to the completion, it was clear that it was going to be big. Lashari says in interviews that he did nothing else during the shooting or production of the movie. Sources say it ended up costing between Rs 400 to 500 million and this doesn’t include the marketing budget. That means at the end of the day, there is a lot of money flowing into movies being made in Pakistan and audiences are responding.

This, of course, is popular entertainment. Filmmakers like Shermeen Obai Chinoy have very little to do with this side of things. She is a documentary filmmaker looking more for critical success than commercial success. However, what she does know and represent is the possibility of the arts thriving in

Pakistan. “The ugly parts of our society force me to ask questions”, Obaid-Chinoy said at the #Next75 event. “People don’t like women doing that. As a storyteller, I began to question every single thing there was. Holding up a mirror to society and making people uncomfortable is what I thrive on”.

That, of course, is what it is all about. Recently as well, the entire fiasco surrounding the release of and censorship of the movie Joyland has shown that there are many social barriers to the success of cinema in Pakistan. For a thriving industry, there must be freedom to explore and pursue art. Without it, there will be very little left.

In 2006, Karishma Ali watched the final of the FIFA World Cup with her father. Until that point, Karishma had only ever seen the sport at a distance, mostly boys in the valley that would play the game. However, watching the game with her father was a transformative experience. Mostly because her father explained all of the rules, named the players, and never once said that it was a boys sport.

Karishman went on to find great success as a football player first and then as a guide to young women looking to make the sport their own. However, her story is a rarity. Women’s sports are largely ignored in Pakistan. And how could they be given any attention when even mens sports outside of cricket have regularly not been given any attention.

Just look back to recent events. In August 2021, two Pakistani athletes made it close to the medals podium at the Tokyo Olympics. Talha Talib from Gujranwala and Arshad Nadeem from Mian Channu both finished in fifth place. Their close brush with bronze means Pakistan’s olympic medal drought has extended from 29 years to at least 32 – with the next chance at success coming in Rio 2024.

Since the games ended, there has been a fierce back and forth over who is responsible. Blame has naturally been directed towards the Pakistan Olympic Association (POA) and its longstanding chairman Lt Gen (r) Arif

Hasan. The POA has in turn responded and pointed out that they are simply responsible for promoting olympic values and player development falls squarely under the jurisdiction of the Pakistan Sports Board (PSB) run by the federal ministry of Interprovincial Coordination (IPC). The truth lies somewhere in between.

It seems that both the PSB and the POA are happy to point fingers at each other and let the whole matter die down in a whirlwind of confusion and accusations. However, both are to blame for different aspects of Pakistan’s Olympics woes. Much has been made of the squalid conditions in which athletes have to train in Pakistan and how they have to fund themselves to make it to the games.

Immediately there is a lot that must happen. Players with raw potential that have made it this far completely on their own like Taha Talib and Arshad Nadeem have to be given facilities and sponsored by private companies or corporate sponsorships if the government is not coming through for them. Both of them are young and with focused training that only steady money can provide, they are still young enough to give Pakistan a serious shot at the Rio Olympics in 2024.

On a larger scale, the perfect solution is to build up a sporting culture in schools and push for reforms. However, more urgent is the immediate restructuring of the PSB, and making sure that the ministry it falls under is held accountable for letting athletes languish. The Olympics and other such events are a great opportunity for diplomacy, as well as the obsessive need Pakistan seems to have to “portray a positive image.” If not for the sake of the men and women that dedicate their lives to attaining excellence in these pursuits and their futures, then at least for the silly aim of positivity.

In all of this, a significant aspect must be encouraging and supporting women’s sports. As with other fields, women have been regularly set-back and handicapped. The same is true for both the arts and sports. If Pakistan is to have any chance of being a great proponent of both sports and arts by 2097, women must be part of the journey. n

The ugly parts of our society force me to ask questions. People don’t like women doing that. As a storyteller, I began to question every single thing there was. Holding up a mirror to society and making people uncomfortable is what I thrive onShermeen Obaid-Chinoy speaking at the #Next75 event of talks@engro