A robust cloud infrastructure would serve as the cornerstone of digital Pakistan

By Ahtasam Ahmad & Taimoor Hassanis the new oil’ , is a term first coined by British mathematician Clive Humby in 2006. The expression has aged well, so much so that it is now part of corporate and tech “lingo” along with other variations being in popular use, for example, “Data is the new gold”.

The ever increasing reliance on data has helped conceive a whole new ecosystem built around the fundamentals of storing and ana lysing data. An important component of this ecosystem is cloud computing, and as Pakistan moves towards digitising its economy, the role of cloud technology is further elevated.

However, according to experts, the current infrastructure for management of data in the country is fragmented and outdated in most cases as in-house IT departments don’t have the adequate competencies to keep up with technological advancements. This leads to a lack of flexibility in data management.

Further highlighting the need to develop the cloud ecosystem, as quickly as possible, is the fact that Pakistan failed to make it into the Association of Cloud Computing Asia’s cloud readiness index. Countries such as India, Indone sia and Vietnam are all present in the rankings.

Attempts to work on this, however, remain underway. In a recent development, Daraz Pakistan and Alibaba Cloud signed an MOU on September 17, ‘22 for the provision of cloud services in Pakistan.

Alibaba, which acquired Daraz in 2018, is one of the biggest cloud service providers in the world, and counted among the top five Cloud Service Providers (CSP).

The signing of Daraz’s MOU with Alibaba was witnessed by Rukhsana Afzaal, High Commissioner for Pakistan in the presence of Daraz founder and CEO, Bjarke Mikkelsen and Alibaba Cloud Intelligence General Manager of South Asia and Singapore, Dr Derek Wang.

A little bit about Daraz before we go on. The company was founded in 2015, and is one of the most well-known eCommerce brands in Pakistan. It boasts more than 40 million active monthly users and over 100,000 active sellers. In addition to this, Daraz University, Daraz’s online learning centre, offers personalised and localised courses covering all areas of the e-commerce ecosystem. “We are glad to part ner with Daraz to bring digitalisation opportu nities to Pakistan, and by offering our proven cloud computing services, we are confident to support Daraz in building up Pakistan’s digital momentum to benefit the wider ecosystem,” said Wang on the partnership, providing much-needed hope. .

Such partnerships enable local companies

such as Daraz, Telenor and so on to market the services of established CSPs and earn a margin of anywhere between 10 percent to 20 percent. Furthermore, by venturing into cloud services through this route, these companies save the cost of investing in their own infrastructure.

pretty obvious by now we’re not talk ing about the fluffy white things in the sky that sometimes turn grey and shower rain upon us. Except for the fact that our cloud is, perhaps, as intangible, what we are referring to couldn’t be more different. This one is a wireless ‘cloud’ system of data storage. The National Institute of Standards and Technology, US Department of Commerce says, “Cloud computing is a model for enabling convenient, on-demand network access to a shared pool of configurable computing resources (e.g., networks, servers, storage, applications and services) that can be rapidly provisioned and released with minimal management effort or service provider interaction.”

What this basically means is that cloud computing is based on the infrastructure that facilitates the delivery of multiple services and applications directly through the internet. These services include networking, database, softwares and data storage. In business terms, think of it as rationing your supplies at a third party warehouse. In this case, the third

party will sort and package them also. To put it in even simpler terms, cloud provides an infrastructure that can replace local storage (computer hard drives in most cases).

Solocal storage — anything that is saved on-site, on a flash drive or local file server—has served us well over the years but cloud is a game changer. It is more efficient, offers huge cost savings, has much better data management and protection, and the processing capacity is higher than that what most local storage systems can offer. Furthermore, it facilitates user mobility as data is accessible from anywhere in the world.

According to experts in the indus try, the current infrastructure for management of data in the country is fragmented and outdated in

most cases. In-house IT departments don’t have adequate competencies to keep up with technological advancements. This then leads to a lack of flexibility in data management, a major reason why many websites crash when subjected to high user traffic.

Cybernet’s RapidCompute, Multinet, PTCL, Jazz’s Garaj are the only significant local providers, whereas Telenor has part nerships in place to offer Alibaba’s cloud services. The range of offerings could be different in both partnerships. International providers such as Amazon Web Services and Huawei Cloud have also ventured into the Pakistani Market.

“Around 70% of the IT budget for big organisations is spent on just maintaining the infrastructure while around 30% is left for innovation. Once they shift to cloud, the tables are turned and you have a higher amount spared to invest into scaling businesses and on top of it there are value add enterprise services that CSPs can provide to further assist businesses,” said Ovais Khan, Head of Delivery, MENAP at Systems Limited when talking to Profit.

While sharing a use case for cloud in the financial services sector, Khan added, “In the lending side of things, we are trying

to automate the whole process of assessing customer creditworthiness and KYC which is a major delay factor in the timely disburse ment of loans. An enabled cloud system in this situation will serve as a central point for not just acquiring the data but also running analytics and other procedures.”

Basically, a centralised data server breaks down the silos that are otherwise present between departments of large organisations which maintain their in-house data storage. Next, an effective third party cloud system is equipped with advanced analytics tools, such as machine learning and powerful servers that can increase the accuracy and speed of data processing.

The situation at present is that the use of cloud services in the country’s public sector is comparatively low, and the bulk of data centres are designed to serve the needs of a single enterprise. This lack of centralised cloud infrastructure remains a major impedi ment to the perks of cloud computing.

Integration of all government databases to cloud platforms will enable the govern ment to better analyse the data which will ultimately lead to quality enhancement of E-Government services. An important point of note is that a cloud infrastructure will help reduce the burden on the national treasury of operating separate data centres for federal entities and departments. It will also increase the level of data security, critical for those public and private organisations that are subjected to regular cyber-attacks.

Ali Naseer, Chief Business Officer Jazz, in an article for a private publication, discussed that a local cloud infrastructure provides a standardised security framework which is much more secure than what other less ‘Tech-Savvy’ entities can develop inhouse. Additionally, network disruptions due to technical faults can also be minimised if a centralised and certified service is used. (Most of the local data centres are Tier-3 certified)

“A local cloud infrastructure, like Garaj powered by Jazz, provides a better experience through localisation. Besides keeping Pakistani data in Pakistan, It includes features like 24/7 support in both Urdu and English, flexibility to pay in Pak Rupees and customised offerings. Local customers really appreciate such flexibilities that usually offshore cloud service providers do not offer”

Ali Naseer, Chief Business Officer Jazz

The SME crowd is also a market for cloud technology given that the business case is very strong for them. Especially, export oriented service businesses like those operating in the IT sector are increasingly adopting the technology as cost efficiency is critical in a market where they’re competing on pricing to the final consumer.

From a consumer perspective, if we compare local vs foreign CSPs, the first point of consideration would be the cost. In reality, there is no comparison as costs of cloud packages vary from customer to customer.

It is different if we have to make a baseline comparison because foreign CSPs such as AWS will be cheaper when it comes to basic storage services. But, if we add other features to the offering, for example backup recovery and customer support then the packaged deal provided by local operators such as Jazz’s Garaj would cost far less.

“A local cloud infrastructure, like Garaj

powered by Jazz, provides a better experience through localisation. Besides keeping Pakistani data in Pakistan, It includes features like 24/7 support in both Urdu and English, flexibility to pay in Pak Rupees and customised offerings. Local customers really appreciate such flexibilities that usually offshore Cloud Service Providers do not offer. Currently, our state-of-the-art cloud platform is serving around 50 enterprises in banking, financial services, startups and public sectors,” explained Naseer.

However, according to Khan of Systems Limited, products of foreign service providers are much more resilient in terms of data storage, disaster recovery/continuity of services and security of that data/assets/systems living in the cloud. This would enable users to leverage Web 3.0 technologies such as blockchain for decentralised processing and storage.

one of the strongest and most convincing arguments of building a cloud infrastructure within the coun try comes from a data security point of view. In the recent past, cyber attacks directed on public as well as private organisations have resulted in loss of sensitive data. Also, the government has concerns over data of Pakistani companies being stored in other territories.

As per SECP’s draft Cloud Adoption Guidelines for Incorporated Companies /Business Entities, issued in August 2021, “All business entities, while selecting Cloud Service Providers, must ensure that the selected service provider does not offer services through their data centres located in any hostile country (i.e. India, Israel, etc.).”

Naseer added more to these concerns; the fact that a major consumer base is current ly using the services of foreign CSPs such as Amazon and Microsoft results not only in an outflow of the revenue generated but is also a missed opportunity for the government in terms of taxation.

An efficient cloud computing ecosystem, therefore, appears to be the only way forward. Besides serving as a bedrock for the introduction of next generation technologies such as In ternet of things (IoT), it would also help public and private sector users to leverage economies of scale and conserve financial resources.

“The products of foreign service providers are much more resilient in terms of data storage, disaster recovery/continuity of services and security of that data/assets/systems living in the cloud. This would enable users to leverage Web 3.0 technologies such as blockchain for decentralised processing and storage”

Ovais Khan Head of Delivery, MENAP at Systems Limited

By Ariba Shahid

By Ariba Shahid

{Editor’s note: There are no women banking CEOs on this list. Unfortunately, there is a conspicuous lack of female bankers in top roles. Currently, UBL is the bank paying their CEO the most. The current CEO’s predecessor was a woman, Sima Kamil, who was not paid nearly as much as the bank is paying their CEO now. In fact, when she joined UBL Sima was paid Rs137 million per year, which was significantly reduced to Rs 94 million in 2019. Banks talk a big game about financial inclusion, a big part of which is bringing women into the fold of banking. Howev er, it is disappointing to see that the barriers to entry for female executives continue to be high and mighty.}

Howmuch does the highest paid banking professional in Paki stan take home every year? The figure comes out to Rs 34 crores 86 lakhs and 60 thousand. That is a salary of nearly Rs 3 crores a month. In that money you could reasonably (or actually very unreasonably) buy roughly 49 PTA approved iPhone 14 Pro Max 128 GBs in a month. Or you could instead buy a 1 kanal plot in DHA Phase 6 Lahore every month, or two Toyota Fortuners a month.

Yet the position of top-dog in Pakistan’s banking industry is a lonely one. The banking mountain is made out of 31 banks — five of which are public sector banks, 22 are pri vate commercial banks, and four are foreign banks. Heading these banks are 31 CEOS or Presidents. All men. All professional bankers. All ridiculously well paid. And all constantly trying to edge each other out.

What some outside the industry may not know is that banking is one of those professions where being a ‘company-man’ is not a point of professional pride nor a good career move. After bankers hit a certain level in one organisation, they regularly shift around, bouncing from one financial institution to another. In fact, most bankers aspire to head not one bank that they’ve worked at their entire lives but to have been part of multiple big banks and hopefully reach the top-slot in at least a couple.

But while the big-boys of banking splash around in the big-bucks that they are making, there are two big questions? How much money do all of these bank bosses make, and do they deliver the bang for the back that their employ ers spend on them? To determine this, Profit has ranked banking CEOs and Presidents in order of how much money they make but with a caveat — what is the return on investment that these high salaries give to the bank? That is why along with every Bank CEO’s salary, we have calculated the returns they generatenamely the return on assets and the return on average equity.

Return On Assets (ROA) is a profit ability ratio that illustrates how much profit

a company can generate from its assets. This ratio measures how efficient a company's management is in earning profit from the economic resources or assets they have on their balance sheet. The higher the number, the more efficiently the assets are used by the management to generate profits. And spoiler alert, the CEOs getting paid the highest are not necessarily giving banks the most bang for their buck.

is no one way to measure which CEO delivers the most substance for the amount of money they are paid.

For starters, this is a very subjective matter. No reasonable value of money can be paid on leadership for example. Then there is the fact that the key-performance-indicators (KPIs) that these CEOs are hired on the basis off are rarely public knowledge. For example, a CEO could be paid a lot because they are taking over a bank that is in trouble precisely to fix that bank’s workings. A CEO that has a stint for five years at a bank could see their work come to fruition years after they have left under the stewardship of a different CEO.

However there are some ways to rank them. The first one is the simple — who gets paid the most. That is the order in which we have listed these CEOs. Without taking into account travel, bonuses, and other such extravagances we have ranked them on the basis of their annual salary. After this, we have

also included two other categories — return on average assets (ROA) and return on average equity (ROEE).

Return On Assets (ROA) is a profit ability ratio that illustrates how much profit a company can generate from its assets. This ratio measures how efficient a company's man agement is in earning profit from the economic resources or assets they have on their balance sheet. The higher the number, the more efficiently the assets are used by the management to generate profits.

Return on Average Equity (ROAE), is a profitability ratio that measures the amount of net income compared to the average sharehold ers’ equity of a company. The formula is used to assess the performance of the company based on how well it uses its shareholder’s invest ment to make a profit. We are not using the return on equity because ROAE offers a more accurate outlook on the general profitability of the business as there are changes in the percentage of owner’s equity throughout the year. This helps take into account any sharp changes in the equity and gives a fair review. Net income is divided by the average share holder’s equity. The average equity is calculated by dividing the sum of beginning equity and ending equity by 2.

On all of these scales, the banking CEOs are ranked differently. To determine a final tally we have averaged out the ranks on both of these scales and compared them to how high the CEO in question is placed on the

salary scale. So for example, if a bank CEO is ranked 4th on ROA and 2nd on ROAE their average rank comes out to 3rd. And if they are, for example, fourth on the list of highest paid CEOs it means they are possibly underpaid. This final calculation is not hard maths, but it is a bit of indulgence just to put things into perspective. There are also other limitations in this methodology, particularly since the size of the bank often skews the calculations. That is why the priority has been given to the ranking of who gets paid the most, and that is the order in which the names appear.

The final analysis of whether a bank CEO has been worth the money can only prop erly be determined after their tenure ends. But without further ado, these are the highest paid banking CEOs in Pakistan.

United Bank Limited (UBL)

Yearly salary: Rs 340.86 million

ROA Rank: 5

ROAE Rank: 10

Average Rank: 7

The highest paid banking CEO in 2021, he is currently the president and CEO of UBL. At the helm for the past two years, Dada took over the reins of UBL from Sima Kamil and joined the back with a significantly better

package than his predecessor had. This is also not Dada’s first stint as CEO of a bank, but it is his first time heading a local bank.

Before this, Dada served Standard Chartered Bank as CEO for over five years, and as CEO and Managing Director of Barclays Bank in Pakistan before that. He has also remained a director at Deutsche Bank. Dada is a graduate of the Wharton School of University of Pennsylvania.

Yearly salary:

Rs 306.18 million

ROA Rank: 1

ROAE Rank: 2

Average Rank: 1

Siddiqui is the founding president and CEO of Meezan Bank. He is also a member of the Information Technology Committee and of IFRS 9 Implementation Oversight Commit tee of the board. He has held several senior management positions including chief executive officer at Al Meezan Investment Bank Limited, general manager at Pakistan Kuwait Investment Company, advisor to the managing director at Kuwait Investment Authority, manager finance and operation at Abu Dhabi Investment Company, and senior business analyst at Exxon Chemical (Pakistan) Ltd. He has also served as the president of the Overseas Investors Chamber of Commerce and Industry.

HBL

Yearly salary:

Rs 265.66 million

ROA Rank: 13

ROAE Rank: 13

Average Rank: 14

You would think the HBL CEO would be the highest paid but he actually comes in at number three. Aurangzeb joined HBL in 2018 as the President & CEO. Prior to this responsibility at HBL, he was the CEO of JP Morgan’s Global Corporate Bank based in Asia, with experience in international bank ing spanning over 30 years in other senior management roles at ABN AMRO and RBS based in Amsterdam and Singapore. He is the only Pakistani to be invited to the exclusive membership of the Global CEO Council organised by the WSJ/DowJones group. He is also chairman of the Pakistan Banks Association, chairman of the Pakistan Business Council, and council member at the Institute of Bankers Pakistan.

A seasoned professional, Aurangzeb probably has one of the toughest jobs in Pakistan’s banking industry. Most banks have legacy which comes with both prestige and baggage, but none more so than HBL. For one of the toughest gigs in the industry, holding firm in it is testament to his skill.

MCB Bank

Yearly salary:

Rs 233.52 million

ROA Rank: 3

ROAE Rank: 8

Average Rank: 5

This is one of those rare cases where a banker has been a company man for almost his entire career. Mumtaz has been affiliated with MCB Bank for the last 30 years during which he has worked in diversified roles including branch banking, credit risk and corporate finance. Mumtaz has served as the head of various divisions at MCB Bank and served as country head for MCB Bank in the UAR for five years. In January this year, he was appointed as the CEO and president of MCB Bank. Prior to being appointed as the CEO, he was group head, corporate finance and international banking.

Yearly salary:

Rs 187.26 million

ROA Rank: 12

ROAE Rank: 9

Average Rank: 11

Bajwa is a veteran banker and his job at Bank Alfalah is not his first time as CEO, nor his first time being the CEO at Alfalah. He was the president of the bank for over five years before he resigned in 2017 for personal reasons. He has also previously worked as the president and CEO of MCB Bank and Soneri Bank. He was also the country manager for ABN Amro Bank and the chairman of the Pakistan Business Council.

Prior to rejoining Bank Alfalah in February 2020, Bajwa was appointed the president and CEO of the Bank of Punjab. He, however, excused himself from the position. He has long been a stalwart of the banking industry and is a favoured man for owners when they want to get their bank out of trouble.

Standard Chartered Pakistan

Yearly salary:

Rs 184.61 million

ROA Rank: 1

ROAE Rank: 7

Average Rank: 3

On the top of our ROA calculations, Rehan Sheikh is one of the highest ranked CEOs on our list. With a career spanning over 38 years in banking, Sheikh has been serving as CEO of Standard Chartered Bank (SCB) in Pakistan since August 2020. Prior to joining, he was the CEO of SCB’s Islamic Banking Group, a position he held for over

four years. Sheikh has previously been a senior vice president at Dubai Islamic Bank, head of corporate and institutional banking at SCB, and senior director and corporate banking head at American Express. Throughout his career, he has held positions in diversified roles including in corporate relationship management, risk management, remedial management, international trade finance and branch management.

Yearly salary: Rs 144.53 million

ROA Rank: 4

ROAE Rank: 5

Average Rank: 4

Nathani is a seasoned corporate banker with more than two decades of experience and has been the CEO of Habib Metro Bank for the past four years. He started his career at CitiBank where he worked as a relationship manager for their corporate clients. He then spent the next seven years at ABN Amro working as Head of Asian Syndicated Loans business and Head of structured finance Asia. Nathani then went back to CitiBank and served as the regional head of Corporate Banking - Middle East. Here he served as CEO of Islamic Banking too. From CitiBank, Nathani moved to Barclays where he was country head and managing director for Pakistan. He then made his way to Standard Chartered as CEO where he served for five years.

Yearly salary: Rs 137.86 million

ROA Rank: 7

ROAE Rank: 12

Average Rank: 9

Hussain was appointed as the CEO and president of Faysal Bank in 2017. He has been with Faysal Bank Limited since August 2008. Hussain has over 22 years of multifaceted experience with prime local and multinational organisations, including multiple senior mana gerial and leadership positions within business and more recently within risk management function, primarily at ABN AMRO Bank and Faysal Bank Limited. His experience also includes a senior role with Samba Bank as the country head, global transaction services busi ness and earlier assignments with Mashreq Bank and Mobilink.

Yearly salary: Rs 134.43 million

ROA Rank: 8

ROAE Rank: 3

Average Rank: 6

The miracle man that survived a plane crash, Masood has not just defied odds in life but also been a lean, mean, banker that has hovered around the top of his industry. In May, 2020, Masood was approved by the Punjab government to head Bank of Punjab as its president. Masood's career spans over 27 years during which he served at top positions for multinational banks in Pakistan and abroad. Masood has served as regional managing director and CEO for Barclays Bank Southern Africa. He has worked at senior positions at Citibank, Amer ican Express Bank and Dubai Islamic Bank. Masood was also appointed as the director general of National Savings by the Ministry of Finance, and he has been CEO (interim) of InfraZamin Pakistan - a DfID, UK driven initiative.

Yearly salary: Rs 128.53 million

ROA Rank: 6

ROAE Rank: 2

Average Rank: 2

Despite being the 10th highest paid CEO in Pakistan, Mansoor Ali Khan got some of the highest performance marks in our ranking coming in at an overall second place on the bang-for-buck scale. was appointed Chief Executive of the Bank on November 1, 2016. He had been with the Bank since 1994 in various positions, including Zonal Head, Group Head, and Chief Operating Officer. He is a nominee director on the Board of Habib

Asset Management Limited and also serves as a Chairman/member of various Internal Committees of the Bank. Earlier, he served at various positions in Bank of Credit & Commerce Inter national (Pakistan, Dubai-UAE, Yemen), from January 1985 to March 1992. Mr. Mansoor is a member of the Council of the Institute of Bankers Pakistan. He has attended many courses/trainings including Directors’ Training Program from the Institute of Business Administration (IBA), in January 2016. He holds a Master’s Degree in Business Administration (Banking & Finance) and has a vast experience in commercial banking.

Sowhat does any of this mean? We started our ranking based on the abso lute salary. Our winner is United Bank Limited’s (UBL) very own Shazad Dada. In 2021, Dada received Rs340.863 million in a year. The second highest-paid CEO is Irfan Siddiqui of Meezan Bank. This makes him the highest-paid CEO in the Islamic banking space in Pakistan. He makes Rs306.181 million which is roughly Rs25.515 million a month.

HBL’s CEO, Muhammad Aurangzeb is the third highest paid CEO in Pakistan raking in Rs265.663 million in 2021. With a monthly income of Rs22.138 million. As the size of the bank goes smaller, so does the CEO's sala ry. The least paid CEO on the list is Bank of

Khyber’s Muhammad Ali Gulfaraz who makes Rs33.616 million a year, and Rs2.8 million a month. But the bank’s legacy issues, deposit size, and coverage are also prime reasons. Since this is his first year at the bank and his first time as a bank CEO, it is likely that he will experience a rise in remuneration.

After all, once you’re on this list, you keep switching bank after bank until it is time for retirement; or you end up at the State Bank of Pakistan (looking at you Sima Kamil). However, looking at the salary as a standalone is simply not enough.Now that we’ve banked these individuals based on their incomes, we’re going to rank the banks based on the returns they generate - namely the return on assets and the return on average equity.

While Dada ranked number one in his salary, UBL’s ROA in 2021 was ranked number 5, Meezan at number 2, just like their CEO; and HBL at number 13. Standard Chartered Bank had the best ROA of 1.8%. This might also have to do with Standard Chartered cut ting back on its physical presence in terms of branches and also its niche of clientele.

Based on Return on Equity (ROE), Meezan Bank clocks in at number 1, Bank Al Habib at number 2, and surprisingly, Bank of Punjab at number 3. In order to further our efforts at ranking the CEOs based on their performance, we’ve taken an average of the ROE ranking and the ROA ranking. The lower the ranking, the better the performance of the

bank, and as a result of the CEO too.

Siddiqui of Meezan Bank ranks number one in terms of his score, followed by Mansoor Ali Khan of Bank Al Habib, and Rehan Shaikh of Standard Chartered at number 3. JS bank’s Basir Shamsie scores the lowest average score of 18 because JS Bank scored 18 in both its ROA and ROAE ranking across banks. Pakistan’s highest paid CEO, Dada, Ranks at number 7 with an average score of 7.5, scoring the 5th rank in ROA, and the 10th in ROAE. However, to understand whether the average score rank is better if you’re paid better, we’ve looked at the differences in rank between the salary ranking and the score ranking.

are the bankers that are not in our top 10 in terms of annual salary. They are still all making a pretty penny, and their respective ranks on scales have been given in the attached graphs, but they are not in the top slots.

Allied Bank Limited (ABL) Gill was promoted from Chief Risk Officer at ABL to the bank’s CEO. He joined ABL in 2005 as regional corporate head where he also worked as head of commercial assets, group head of liabilities, head of commercial and retail risk, and head of operational risk. He was promoted to the position of CRO in 2017 and then finally CEO in 2021.

Askari Bank

Bokhari is not new to the banking space or the CEO position. His career which spans 32 long years began at the Bank of America in Pakistan. Later he moved to

HBL as Head of Corporate and Investment Banking. In 2004, Bokhari got his big break and joined the CEO club by taking charge of the President and CEO position at UBL where he stayed till 2014. He then served as President and CEO of NIB Bank which is a wholly-owned subsidiary of Fullerton Financial Holdings in Singapore. Bokhari then served as Minister of State and Chairman of the Board of Investment at the prime minister’s office in 2021. He then joined Askari Bank.

Shamsie joined JSCL in 1994 as Director and Head of Fixed Income where he looked at the treasury and investment banking department, primarily debt capital markets. He then moved to JS bank as the Senior Executive Vice President and group head for treasury, investment banking, and financial institutions. In 2017 he was promot ed and made deputy CEO. In 2018, he was appointed president and CEO of the bank.

Khan joined Summit Bank in 2021 as the president and CEO. Prior to this, he was a director at Emaan Islamic Banking at Silk Bank. He has also served as group head distribution for the Middle Markets and SMEs at Dubai Islamic Bank

Gulfaraz is a recent addition to the Pakistani bank CEOs joining in August 2021. He has banking experience of 25 years in global corporate and in vestment banking. He started his career with Bank of America in Pakistan and later moved to Bank of America, London. He then joined

Mizuho Corporate Bank in London and rose to the position of Managing Director-Head of Corporate & Investment Banking for UK, Ireland & Nordic countries. Before joining the Bank of Khyber, he remained associated with Fauji Foundation as Member, Board of Directors.

National Bank of Pakistan (NBP)

Hasni is currently serving as the acting president of the NBP, a position he assumed five months ago after Arif Usmani’s tenure ended. Hasni will continue in his position until the Government of Pakistan appoints someone else as the president of the bank after cabinet’s approval. Hasni has been affiliated with NBP for the last 12 years and has served as its senior executive vice president and group chief of various divisions. Before NBP, Hasni was the chairman of Pakistan Mortgage Refinance Company (PMRC), non-executive chairman of First Credit Investment Bank Limited, executive vice president and head of corporate finance at IGI Investment Bank Limited and chief operating officer of Lahore Stock Exchange. He has also served as board member of various organisations.

SAMBA Bank

Sattar joined SAMBA Bank in 2013 and is currently its president and CEO. With experience in retail banking, consumer finance, branch banking, cash

management, remittance business and corpo rate and Islamic banking, Sattar’s career spans over 40 years. Prior to joining SAMBA in 2013, he worked at UBL where he headed various divisions. He has earlier worked at MCB Bank and CitiBank, with a stint at BCCI. Sattar has held directorships including at PICIC Asset Management, MNET Services Pvt Ltd, Bank Al-Bilad Investment Co and UBL Asset Management.

Ali was appointed as the president and CEO of Bank Islami in October 2018. Before moving to Bank Islami, Ali headed the corporate and investment group of Meezan Bank. His expertise is in the fields of treasury, finance and investment and corporate banking. Besides affiliation with Meezan Bank and Bank Islami, Ali has worked at AF Ferguson Co as well as Shell. Muhtashim Ahmad Ashai - Soneri Bank Ashai joined Soneri Bank as its president and CEO on April 1, 2020. Before Soneri, he was the president and CEO of MCB Islamic Bank Ltd. Ashai has a diversified experience in banking with a career spanning 27 years working at domestic and international financial institutions. He started his career at Fidelity Investment Bank, followed by working at ABN Amro Bank, working in Pakistan, Japan and China for ABN Amro. He later joined MCB Bank where he was group head corporate and international banking for more than 11 years

Muhtashim Ahmad Ashai Soneri Bank Ashai joined Soneri Bank as its president and CEO on April 1, 2020. Before Soneri, he was the president and CEO of MCB Islamic Bank Ltd. Ashai

has a diversified experience in banking with a career spanning 27 years working at domestic and international financial institutions. He started his career at Fidelity Investment Bank, followed by working at ABN Amro Bank, working in Pakistan, Japan and China for ABN Amro. He later joined MCB Bank where he was group head corporate and international banking for more than 11 years. . n

Ina television interview a few days ago, Pakistan’s cur rent finance minister boasted that he has been dealing with the IMF for 25 years. This claim was meant to assuage concerns and reinforce trust that he is the right man for the job. The comment, and the failure of the host to push back on the finance minister, sums up all that ails Pakistan, its politics, and by extension its economy.

Most countries in the world do not need to go to the IMF on any given day. Bangladesh, a success story in the Indian subcontinent over the last few years, has recently got ten in line, as it seeks to preemptively stabilise its economy from a rapidly deteriorating global economic environment. While quite a few countries have ended up in the IMF’s pro verbial intensive care unit over the years – even the United Kingdom recently faced the IMF’s ire recently – none more so than the likes of Pakistan, Argentina, and Egypt.

This then begs the question: Why does Pakistan keep going back to the IMF? A lot of ink has been used to explain the reasons why, which fundamentally have to deal with the inability of Pakistan’s ruling class to change their habits and restructure the economy.

But the more important question that we must all think about and ponder over is this: Why is it that a particular cohort of individuals, Mr Dar included, are proud to have learnt how to deal with the IMF and secure one bailout after another?

The answer to this question, perhaps, has less to do with economic or political analysis, and more to do with human psy chology. Pakistan’s ruling class – and the current finance minister is as much of an insider of this ruling class as one can be – has become used to feeding off the rents provided to it not only by the country’s citizens, but also the global community. From the early days of Ayub Khan, when the geopolitical rents related to the Cold War began flowing in, to the last spurt of rents under the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), geopolitical rents have provided the financial resources and space to “grow” the economy.

That this growth has been unsustainable, unequal, and unproductive is an established fact. Over the years, the ruling class has not only become comfortable but proud of the fact that they know “how to manage” institutions such as the IMF, World Bank, and the ADB. Of course, these institutions and their backers have played along, mainly because geopolitical necessities demanded it. But as the world has changed, it has become increasingly difficult in recent years to receive the kind of financial support Pakistan needs to stabilise its economy.

But the ruling elite have a mechanism to even deal with the downturn in geopolitical rents: Making the argument that Paki stan is too big to fail. This argument has been the last pushback this author has received during a recent visit to Pakistan. Pressed hard on the downward trajectory of the economy and the financial logjam the economy is in, members of the upper echelons of society fall back on the argument that the world cannot let us fail. They argue that this is a country of over 230 million people with nuclear weapons, and if there is an economic meltdown, then all bets are off.

In short, Pakistan is holding a gun to its own head, and if the world does not help, it will have to clean up the mess once the gun goes off.

The writer is Director of the Pakistan Initiative at the Atlantic Council, a Washington D.C.-based think tank, and host of the podcast Pakistonomy. He tweets @uzairyounus.

This is the psychology of “I have been dealing with the IMF for the last twenty-five years.” And it is this psychology that has brought Pakistan to the brink. The ruling class wants to maintain the status quo and the bet is that the global community, with all the issues it is facing today, would rather spend a few more billion maintaining the status quo, because the last thing it wants is another crisis.

The tragedy of this approach is that there is literally no incentive to reform, to alter the status quo, and to create opportunity for the many, not just the few in the Islamic Republic. The median age in Pakistan is 24 years, meaning that Dar has been dealing with the IMF before the majority of Pakistanis were even born. Readers can determine whether this is something to be proud of. n

The temperature in Lahore has not dropped below 30°C yet, but the ugly grey sheets of smog that the city’s inhabitants have become accustomed to have once again descended in all their overwhelming gloominess. There was a time not too long ago that the winter months were the pride of Lahore. In the course of the past decades, they have become its most dangerous and unattractive feature.

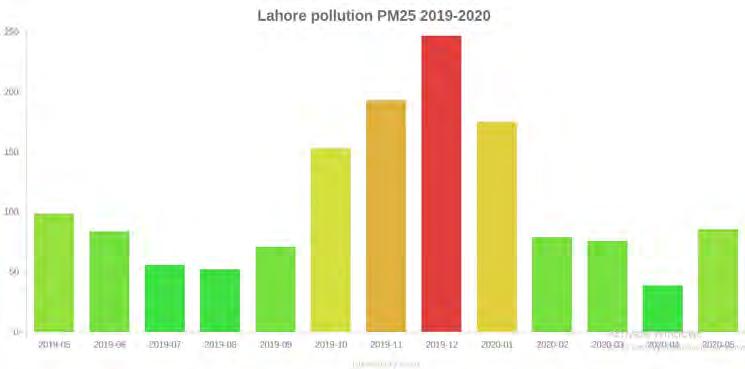

Normally, in most cities affected by smog, unhealthy levels of air quality persist during the winter months. In Lahore it now seems that it does not need to be cold for there to be smog but rather it simply needs to be not insanely hot. That is the scale of the problem we face. On Friday with temperatures still hovering above 30°C the average AQI in Lahore was 157. In more than one area it was over the 250 mark. By the evening, when all vestiges of the sun had given way to night, the average AQI in the city had risen to 176.

The figures may not faze an average Lahori. After all, for years the people of this city have been witness to the worst air quality anywhere in the world. According to the AQI scale, anything over 150 is unhealthy, anything between 200-301 is very unhealthy, and anything over that is straight up hazardous. Lahore has regularly seen AQI rating above 600 — double the amount at which it is hazardous.

To understand this, the air quality index is calculated based on averages of all pollutant concentrations measured in a full hour, a full eight hours, or a full day. The final calculation is made by averaging at least 90 measured data points of pollution concentration from a full hour. For Lahore to regularly measure well above hazardous is shocking, and the governmental and institutional apathy in response is criminal. To put things into perspective, in September 2020 the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality and Lane Regional Air Protection Agency released data that showed historical record-breaking air quality across the state following massive forest fires that left the state engulfed in ash and soot. The resulting AQI calculations that caused alarm and shock? Just under 500. Three months later, in December 2020, Lahore regularly capped this rating with no forest fires in the vicinity.

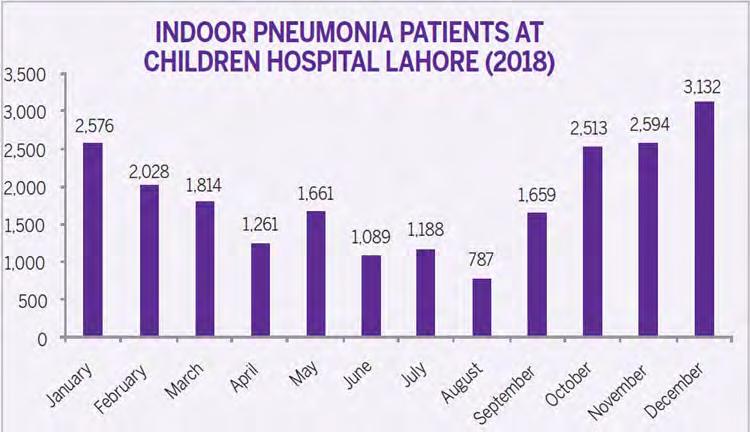

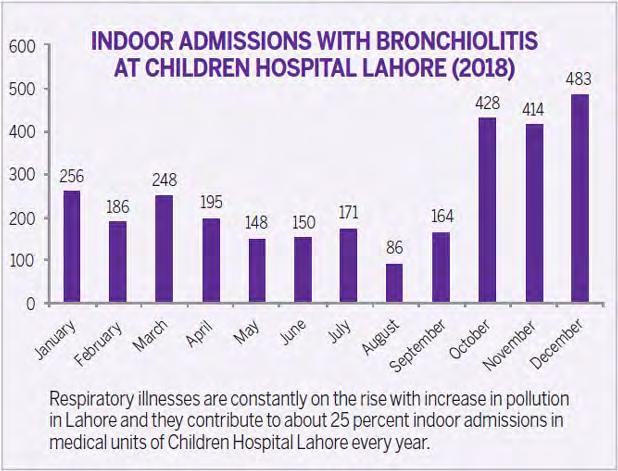

The scale of the problem is massive and its con sequences will be dire in the years to come. Prolonged or heavy exposure to hazardous air causes varied health complications, including asthma, lung damage, bronchial infections, strokes, heart problems, and shortened life expectancy. A report in Dawn from back in 2019 points out how a 2019 analysis by the Air Quality Life Index produced by the Energy Policy Institute of the University of Chicago showed that long-term exposure to particulate matter air pollution was reducing the average Pakistani’s life by “more than two years.” And a 2018 study commissioned by Air Quality Asia, and carried out by Dr Junaid Rashid and Dr Shazia Manzur of Lahore’s Children’s Hospital, shows a spike in admissions for lung-related ailments during the smog season.

The ‘Global Alliance on Health and Pollution’ estimated in 2019 that 128,000 Pakistanis die annually due to air pollution-related illnesses. What is more alarming is that the statistics for the long-term damage that these prolonged years of smog will have on the health and lifespan of the city’s population are yet to even materialise.

The writer is assistant editor at Profit. He also writes for The Dependent. He can be reached at abdullah.niazi@ pakistantody.com.pk

Themajor issue that cities like Lahore face is photochemical smog. In the winter months, smog occurs mainly when there is an excess of particulate matter and sulphur dioxide. Essentially, the amount of pollutants in a city’s air is pretty much at steady rates throughout the year. Emissions from cars and factories are the same in both the summer and the winter months.

In Lahore, for example, the only significant difference between the summer and winter months is that crops are burnt in the October-November period which contribute to smog.

We are not condemned to live in this hell forever. Measures can and must be taken

What happens in the winter, however, is that the air turns cold which means it also turns denser and is slower to rise above. Essentially, the entire city loses its ventilation. Think of it this way, if there are 10 people in a small room smoking with the exhaust fan on, the smoke is still harming the passive smokers but it is not hanging in the air constantly. Turn the fan off and you will have a hot-box that will be much worse for you. That is what happens to Lahore. Since the air becomes denser and heavier, it no longer takes the pollutant particles up with it causing them to hang around the entire city in sheets of smog.

Now, the question is where are these pollutants coming from and what have we done about it as of yet? “The smog in Lahore is caused by a confluence of metrological and anthropogenic factors,” said Saleem Ali, a member of the United Nations’ International Resource Panel. Namely, temperature inversion traps pollution in the atmosphere, which — alongside seasonal crop burning on the Indian-Pakistani border — combines with other sources of year-round pollution and fog to cause a spike in pollution and winter smog.

The reasons why air quality has been steadily declining in cities like Lahore are numerous. Vehicular emissions, industrial pollu tion, fossil fuel-fired power plants, the burning of waste materials, and coal being burned by

thousands of brick kilns spattered across the province are all part of the problem.

Even these reasons, however, have been politicised. Many government ministers during the administration of different parties have claimed that a big reason for the Lahore smog is Indian farmers burning crops across the border. The reality is that crop burning seasons take place from late October to early November while the smog hits its peak in December and January.

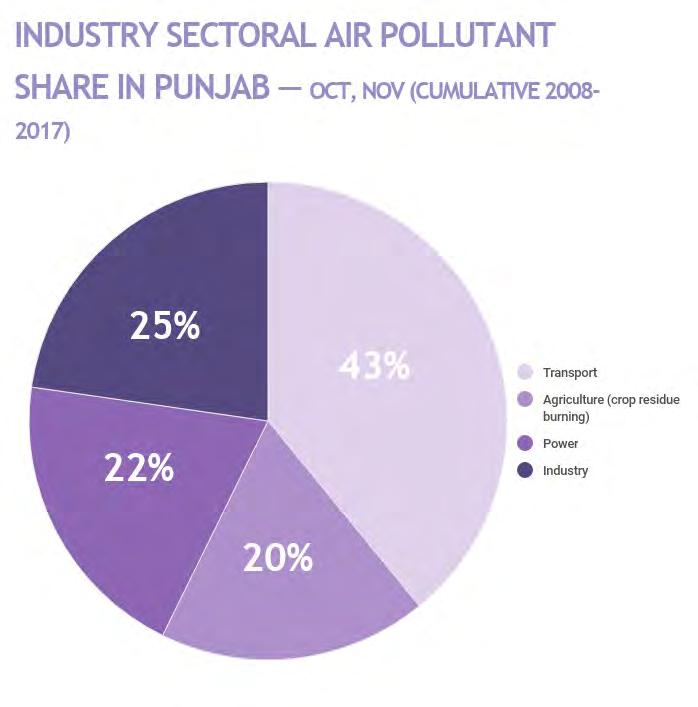

The real reasons are the emissions from vehicles and industries. In fact, agriculture related crop burning only accounts for around 20% of all pollutants while transport accounts for around 43% — with the rest coming from power and industry. Not only is Lahore a sprawling mess with no walkability and an insane de pendence on cars and bikes for mobility, these vehicles use cheap fuel that does not comply with international standards and is horrible for air.

The lack of vehicular fitness and emis-

sions testing, alongside use of poor-quality fuel, have compounded the city’s air pollution problem. Federal plans to switch to Euro 5-compliant fuel have faltered due to lingering economic troubles, including rising inflation.

reality of the situation is that we know what the root cause of the problem is. The city is filled with cars that have deadly emissions. It is close to unregulated industrial zones and perhaps worst of all it has been a problem that is consistently ignored because it goes away in the summer. There are two ways to go about solving this problem. To start off there are short term measures that must be taken to provide immediate relief.

Until a larger plan of action can be implemented, there are some things that the government can do. In a lot of European countries, restrictions of parking, reductions in speed limits, and pulling half the vehicles off

the roads have been some of the more drastic measures.

Most cities justify these schemes on the basis that traffic is a major source of air pollu tion, and any action must help. Independent scientific evaluations are mainly restricted to the biggest cities. For example, data from Madrid and Paris shows that banning the most polluting vehicles can reduce traffic pollution by about 15-20%.

While these measures may seem unthinkable, there is merit to them working out. Last year, the Punjab government also passed an order instructing companies to tell their employees to work remotely to reduce traffic. Schools were also shut down. More such actions should be taken.

The only problem is that such short-term fixes will provide some relief, particularly to those with pulmonary vulnerabilities, they will largely be inconvenient and ineffective. In the longer run, better strategies need to be adopted. This means discouraging crop burning. This means reducing brick kilns. This means improving the quality of the fuel we use and finally shifting to Euro-5. It also means en couraging alternative sources of energy such as solar. However, the most important factor will be redesigning the city in a way that makes all of this possible.

A drastic revamp of the public transport, afforestation in dense urban areas, higher taxes on cars, distancing industrial zones, and plans to try and turn Lahore into a more walkable city will be vital to making Lahore liveable again. And that is what we must remember — it is possible.

This year, with the problem rearing its ugly, sulfuric head early even by its own hellish standards, it is worth looking at what can be done to address it both in the short and the long run. Because here’s the thing: this does not have to be our fate and it can be reversed. In many European countries, smog was a crippling problem that was fought off.

Thick smog used to frequently blanket the UK capital in the 19th and 20th centuries, when people burned coal to warm homes and heavy industry in the city centre pumped chemicals into the air. Referred to as "pea-soupers", the most famous of these events was the socalled Great Smog of London in 1952, famously

shown in the Netflix show The Crown. As a result, the Clean Air Act was passed in 1956, regulated both industrial and domestic smoke, imposing "smoke control areas" in towns and cities where only smokeless fuels could be burned and offering subsidies to households to convert to cleaner fuels.

Beijing is another example of a city successfully fighting back smog. China's rapid industrialisation brought a huge rise in air pollution. Coal-burning power stations and a boom in car ownership from the 1980s onwards filled Beijing's air with hazardous chemicals. What was the solution? Years of hard work. A UN report this year shows that in the space of just four years, between 2013 and 2017, fine particle levels in Beijing dropped by 35%, while levels in surrounding regions dropped by 25%. "No other city or region on the planet has achieved such a feat," the report says. But this was because of measures introduced and refined over the course of two decades, beginning in 1998.

This is the most critical part of the equation. Up until now, the smog is sue has been taken for granted. It has been written off as a phenomenon, or a new reality, or some kind of act of God. The government has responded with ad hoc actions to firefight the problem on a temporary rather than a sustainable basis. The utter failure of the administration to take durable measures to improve the air quality has inflicted severe, long-term harm on public health, putting peo ple at greater risk for heart and lung diseases.

The truth is it is entirely created by our own irresponsibility. While larger goals like shifting to clean energy are important, in the meantime we must at least revamp Lahore and other cities to make them friendlier to the environment. Because as things stand, the consequences of this in the future will be dire. n

By Daniyal Ahmad and Ariba Shahid

By Daniyal Ahmad and Ariba Shahid

Army-doctor-driven. Bumperto-bumper genuine. No dent, no paint. If you’ve ever been sludging through the muck of the used-car market in Paki stan trying to find your next ride, these are some of the first things you will find proudly displayed in ads. Not whether the engine is in good condition or if any major mechanical or electrical work has been done on the car, but instead a strange obsession with how many little scratches and touch-ups a car has undergone in its lifetime.

It is a belief that stems from a long-held conception that in Pakistani society after God, family, and real estate there is only the automobile. Automobiles have long been considered a good store of value — even though they are a hedge against inflation. There is a long, twisty, history behind where this conception comes from. Put very briefly, it is because cars are imported in Pakistan and their prices fluctuate with the dollar. Which is why when you buy a car in Pakistan, one of the first questions you ask is what the resale value is going to be like in five years, and which is also the reason that when you’re selling that very car people on the second-hand market want it to be as close to ‘genuine’ as

possible. Bumper-to-bumper of course.

It is a fact as sure as eggs are eggs. When you walk into a Toyota, Honda, or Suzuki dealership the salesperson will give you the same pitch each time “Sir yai gaari kabhi loss nahi de gi apko.” The only problem is that unlike Pakistan’s other investment obsessions, a car is neither a DHA plot, nor a brick of gold. It is a commodity, the ownership of which is deeply personal. If you ever talk to them about their own car after excitedly enumerating their favourite features they will first discuss keh petrol kum khaati hai, and then its resale value, and what a good and smart and intelligent investment they have made.

Yousee, in Pakistan cars are considered to be an asset class. When a salesper son checks the car you’re about to sell him, his “bumper-to-bumper genuine” inspection is basically him looking to see if the asset has any impurities; almost akin to a gemologist peering through his microscope to check the purity of a gem.

But this is nothing new. Cars being treated as assets is as old as the automotive industry in Pakistan. While you are in the pro cess of reading this, hundreds of cars will have changed hands on Lahore’s Davis Road. All the buyers and sellers will have patted themselves on the back for having bought an asset in these stressful times.

But what if we told you that this popular belief is trash? What if Profit told you that a car is, in fact, not an asset? Owning your first car is a milestone but to be able to buy one of your

choice is a right of passage. Knowing what to look for, being able to make a decision based on factors that are important to you, is freeing, cathartic almost. But while it is all this, the decision is more often than not, also practical.

For example, one common denominator amongst all buyers is the resale value. It is understandable that everyone would want a return on their investment, but cars ‘normally’ fall under the category of consumer prod ucts. At least when you open a normal school textbook.

The world over when you buy a car, it depreciates. It loses its value year-on-year (YoY) and the value at which someone finally sells their used car, at i.e. disposable value, is usually lower than the price they bought it for. By a hefty amount in most cases as well. It is like any other thing you would buy, for example an iPhone.

It is not the same in Pakistan.

Here you can buy an old car, drive it, keep it for a few years, let it depreciate and still sell it for a higher price than what you

bought it for. How is this possible? The gist of the matter pertains to the components used to assemble cars in Pakistan, and the volatility of the Pakistani Rupee. How much of an aberra tion are we looking at here then?

Profit looked at a Toyota Corolla Grande from 2015 to do the maths – It’s selling price at launch (2015) compared to its price in subsequent years till 2022. The price was obtained through market research in collaboration with automotive showrooms based in Lahore.

The Corolla Grande was found to be retailing between Rs 2.8 million to 3.1 million above its theoretical net-book value (NBV), depending on the method of depreciation (more on this later) used, in the second-hand market in 2022. What does Profit mean by this? Well, depending on which depreciation method is used, the Corolla Grande should only fetch a price between Rs 125,096 and Rs 434,000. In reality the car is currently being sold for a price of Rs 3.3 million.

The real question is, are there gains to be made? If someone had bought the Corolla Grande in 2015 and were to sell it right now, they would have made a return of 52.1% for a total of Rs 1.13 million in absolute terms. To put that into context, Rs 1.130 million is equal to more than half of what they would have paid for the car to begin with.

The Corolla Grande is able to achieve this feat as it has seen a price increase in six of the seven years following 2015. Depending on when someone picked up the Corolla Grande between 2015 and 2021 to sell it in 2022, they would have been able achieve a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) upward of 5% throughout the time period.

Appraising a car using these parameters makes it sound like such an enticing deal. You get a fantastic return on your investment. You get to fully enjoy your investment. But Profit is going to tell you that you ought to focus on the second aspect rather than the first because the Corolla Grande wouldn’t have beaten inflation or depreciation in any of the years we’re looking at.

In effect, you would have been worse

Customers buy cars and try to sell them for a gain but then find out that the new car is four times more expensive because you have become worse off in US Dollar termsMuhammad Iftikhar Javed, Business Head of Secured Lending at Bank Alfalah

off in real terms despite your gains in absolute terms. If this is sounding confusing, let us be gin by looking at something people often miss when thinking about investments.

Toexplain the matter, Profit has cre ated a price index for the aforementioned Corolla Grande and compared it with inflation and the Rupee’s devaluation.

The index has been created because of its utility in expressing data time series and comparing/contrasting information. Indices provide a simple way of representing changes over time. An index number is a figure reflecting price or quantity compared with a base value. The base value always has an index number of 100. The index number is then expressed as 100 times the ratio to the base value. Note that index numbers have no units, example Rs or $.

Inflation and the Rupee’s depreciation was acquired from the Pakistan Bureau of

Statistics (PBS) and the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) respectively.

Why the Corolla Grande in particular, you ask? Well, beyond the cult status that it’s amassed, a Toyota Corolla is, perhaps, one of the most liquid cars/assets anyone can possess. The Corolla also had by far the highest sales numbers in 2015 when looking at the sales data provided by the Pakistan Automotive Manufacturers Association (PAMA). Using the Grande variant is just the frosting on the cake.

For depreciation, Profit utilised both reducing balance (RB) and straight line (SL) methods. RB is an accelerated depreciation system that results in declining depreciation expenses with each accounting period. In other words, more depreciation is charged at the beginning of an asset’s lifetime and less is charged towards the end. Whereas SL is a consistent depreciation system where there is an equal depreciation amount recorded throughout the life of the asset, as the cost of the asset is spread evenly for each year that it is used.

RB is most useful when an asset has higher utility or productivity at the start of its

useful life. The depreciation expenses reflect the assets’ functionality. RB works for cars as its wear and tear, and maintenance costs increase at an exponential rate with the distance it covers in terms of travel. SL is most useful when an asset has equal productivity throughout the entirety of its life. Profit used this alongside RB as not all vehicle drivers are the same. Some travel far less frequently than others, and therefore the exponential increase would not be applicable to them. A mix of RB and SL allows Profit to capture drivers who fall under each category.

Cars in the Pakistani market tend to oscillate between both definitions so Profit utilised them for added measure and set an annual RB depreciation at 30% and SL depre ciation at 10%. Finally, in terms of evaluating the return on the car, Profit utilised the CAGR, (CAGR is the average annual growth rate of an investment over a specified period of time longer than one year) because it takes into ac count the effects of compounding, and thereby incorporates the earnings/loss that arose in the preceding period as well.

With growth rate, you’re simply looking at the percentage change in an investment’s value over a specific period of time and not incorporating the preceding period to the principal amount. With CAGR, you’re looking at the investment’s average annual growth rate over a specific period of time. This is a more accurate way to compare investments because it smooths out the effects of short-term fluctuations.

Looking at the inflation adjusted return for the Corolla Grande for the entire period using the index, the Corolla Grande had increased by 52 basis points whereas inflation had increased by 77 basis points for a net loss of 75 basis points. The story is exactly the same for the entirety of the duration. The price of the Corolla Grande actually fell from 2016 to 2018 whereas inflation arose. It increased from 2019 till 2022, but inflation outpaced it every year during the period. Inflation on average beat the Corolla Grande by 12.5% year-on-year (YoY) from 2016 to 2022.

This question is something different. It is an asset but not in a view of return on investment. After 2012, car prices increased and never dropped below the invoiced value so yes- people feel secure while having a car but it has never been adopted as a factor of investment or return

Adjusting for depreciation, the Corolla Grande fairs even worse. Looking at the entire period, the returns on the Corolla Grande had increased by 52 basis points whereas depre ciation had risen by 200 basis points. As with inflation, it lost to depreciation YoY as well in terms of basis points. However, the difference between these two metrics is more stark than between inflation and the Corolla Grande. On average the car lagged by 36% in terms of basis points to depreciation from 2016 to 2021.

In simpler terms, if you wanted to beat inflation then the Corolla Grande is not something you should have bought. The same is the situation with depreciation. Buying the US Dollar rather than investing in the Corolla Grande would have been a better hedge against depreciation. Profit would like to highlight that depreciation particularly beat the Corolla Grande in 2022 because of the macroeconomic situation. A return to Daronomics may reduce the standard deviation from the rest of the years.

Now let us look back at the resale value of the Corolla Grande. If someone did want to know what the best year was to sell their Corolla Grande then according to Profit’s estimates it would have been 2018. There is no doubt that 2022 provides the best return in ab solute terms as the Corolla Grande would have increased by a total of 52 basis points since 2015, but as of right now, the seller would have been the worse off in relative terms. In

relative terms, inflation and depreciation are at the lowest edge in 2016 in comparison to the Corolla Grande.

You would have been worse off in any year but you would have been the least worse off having made the sale in 2016. This probably also answers the question as to whether the Corolla Grande was ever an investment. Nope. It wasn’t.

The question then is, should you have bought a Corolla Grande as an investment to begin with? Before we answer this question, let us discuss why we’re even looking at cars from an investment perspective to begin with.

we’ve all heard about how cars are a good store of value. Right? Sales personnel will repeat the line till you walk out of the showroom.

“Toyota pai aap kabhi loss nahi banatay” said a salesperson when Profit was deciding which car to use as the base for our story. However, for the uninitiated, who are wondering why this is a common perception to begin with, Profit has documented the entire matter in an earlier piece.

Read more: The lopsided market struc ture of the automobile industry

However, the tl;dr edition relevant to our study goes back to the nature of the inputs for cars and the nature of the macroeconomy. Irrespective of automotive assemblers’ claims of localisation, all cars in Pakistan rely on imported inputs in some capacity for several reasons. Cars in Pakistan are, thus a net, imported commodity, and their price is linked to the US Dollar. Subsequently, whenever the Rupee depreciates, which is a guarantee based on the past few years, the price of cars rises. Cars are, thus, hedges against inflation.

Furthermore, until recently, Pakistan has had very few players in the automotive space.

Even now, for a country with a population that is in excess of 207 million, the number of players still pales in comparison to other comparable nations. Pakistan’s protectionist regime only compounds this by reducing competition. What all of this does is reduce the overall number of cars available in the country. This relative scarcity adds to the value of cars that do exist and therefore, limits the degree to which their value is eroded, relative to other competitive markets.

Such a market also makes it conducive for automotive manufacturers to factor resale value in their vehicle’s marketing plans. Au tomotive manufacturers thus proactively take steps to ensure that, at least in absolute terms, their vehicles do not fall prey to rapid devalua tion in any manner. Profit has documented how companies and vehicles that forgo this aspect are then treated unfavourably by the market.

Read more: The KIA Sorento 101 – How not to price a car

Evidently, the snake-oils salesman of the auto industry never factored in relative returns that you would make when selling your car. This is likely not a result of any failing of his own, but customers simply just not asking him for the relative gains to be made from the sale of the car.

“This question is something different. It is an asset but not in a view of return on investment.” said Muhammad Iftikhar Javed, Business Head of Secured Lending at Bank Alfalah, when Profit asked if cars were assets to begin with and whether banks advise their clients to consider them as such.

“In larger scope of concept it is a “No” except for a certain part of the customer base who consider the car as a means of “forced savings’ ‘ to create an asset that they can later sell whenever they need the money.. These custom ers are mostly from small enterprises located in trading markets i.e. Shahalami, Azam Cloth,” he said. “Post 2012, the car prices increased and never dropped below the invoiced value so yes, people feel secure while having a car but it has never been adopted as a factor of investment or

return,” he concluded.

Javed stated that his statement is lim ited to cars bought via auto financing. Profit believes that his explanation can be extended to customers who buy their cars primarily through cash. Auto-financing is by all means a method to bridge the gap between a customer’s available finance and the price of their desired vehicle. The reasons for why customers are buying a car to begin with are endogenous, and likely exogenous of the financial methods used to procure a car for the majority of customers.

It’s unlikely that salespeople will change their pitch to customers whether they buy the car through financing or cash. Both customer segments are equally likely to believe that they have acquired an asset that will be a store of value for them.

“It is an asset in Pak Rupees (absolute terms) but in real terms it is not, particularly not in terms of the US Dollar (depreciation),” says Suneel Munj, founder of PakWheels. It is important to remember that while we pay for cars in rupees, we in reality do so in dollars since they are largely imports. “Customers buy cars and try to sell them for a gain but then find out that the new car is four times more expensive because you have become worse off in US Dollar terms,” explains Munj. That, of course, brings us back to the original question

Westarted the piece by saying that you ought to enjoy your purchase because it is a car after all. Profit stands by it. Everyone who bought the car with the notion that it would be a good store of value, did benefit from its utility. Unless, of course you are part of the group of people that solely bought it with the intent to sell and locked it up in storage for a period greater than one year.

Unlike other ‘asset classes’ it’s not something that is locked away in a vault, a promise for a piece of land in an area you may never get, or a weirdly named security that your broker found for you. It is a car. Despite the fact that you are losing out on value, you have mobility, and that too in a vehicle of your choice. While you cannot place a price on that, practically speaking there is a price to it. This is because depreciation methods do exist and because automotive companies have set a price on it.

But you can’t put a price on the happiness you will personally get, right? BMW’s already managed to monetise their heated seats after you purchase the car so maybe, at least not for the next few years. n

we asked; should you buy it then?