13 minute read

VRG is seeking Rs1bn to capture the unbanked. What makes it tick?

VRG

is seeking Rs1bn to capture the unbanked. What makes it tick?

Advertisement

Backed by PathFinder, the fintech company wants to bank the unbanked. How are they any different?

By Taimoor Hassan

If you are an investor, would you place your bet on a fintech company that has based its business case on what the banks have actively tried to avoid? Lets flip the question to make it more easily comprehensible: would you place your bet on financial inclusion? The popular belief, that Pakistan has a hugely unbanked population therefore the opportunity to provide financial services therefore create a great business is massive, comes with a caveat: the financially excluded are poor and there is not enough money that can be made off of them. This argument is enough for the banks to rest their case of not banking the unbanked or serving the underbanked. Unless these segments do not have money, it does not make sense for the banks to chase them. The flag bearers of financial inclusion, fintech companies JazzCash and EasyPaisa, have done phenomenally well in banking the unbanked up until Covid-19. Without spreading physical brick-and-mortar branches like banks, both these fintech companies built a sprawling infrastructure of branchless banking agents to provide financial services to the segments untouched by the banks because it did not make a commercial case for them.

The abilities of these fintech companies, however, were severed seriously when the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) slashed IBFT charges during the pandemic, and kept most of the transactions free later as well, dampening

the prospects of making money for these financial institutions. The bulk of the money that these fintech companies make is by charging customers an IBFT fee each time they send money to someone through a branchless banking agent. The SBP completely waived these charges for consumers during the pandemic, restoring the charges later on transactions of over Rs25,000. According to the central bank, 80% of the IBFT transactions are below Rs25,000. This has hit them hard. Both EasyPaisa and JazzCash are now rethinking their model of branchless banking, now that less money can be made on financial inclusion.

So ask the banks and they will tell you that financial inclusion is not seductive. Ask the branchless banking companies and they will tell you that financial inclusion is not seductive anymore. Would you, then, want to invest in financial inclusion?

Your answer would probably be yes, if the company you are investing in is Virtual Remittance Gateway (VRG), a Pathfinder Groupbacked fintech company that was launched in 2018 by Ikram Saigol - a war veteran, diplomat, commentator and a businessman who frequently represents Pakistan at the World Economic Forum (WEF). Saigol’s fintech company, VRG, is uniquely positioned to push Pakistan’s financial inclusion numbers though it has some challenges to overcome. The company boasts impressive performance, raking in 4 million accounts under Asaan Mobile Account (AMA) scheme and billions processed on these accounts since its soft launch earlier this year. The company is passively helped by the central bank which has to increase financial inclusion numbers and reach 65 million new accounts by 2024, and is now raising Rs1.05 billion to scale the fintech platform for financial inclusion.

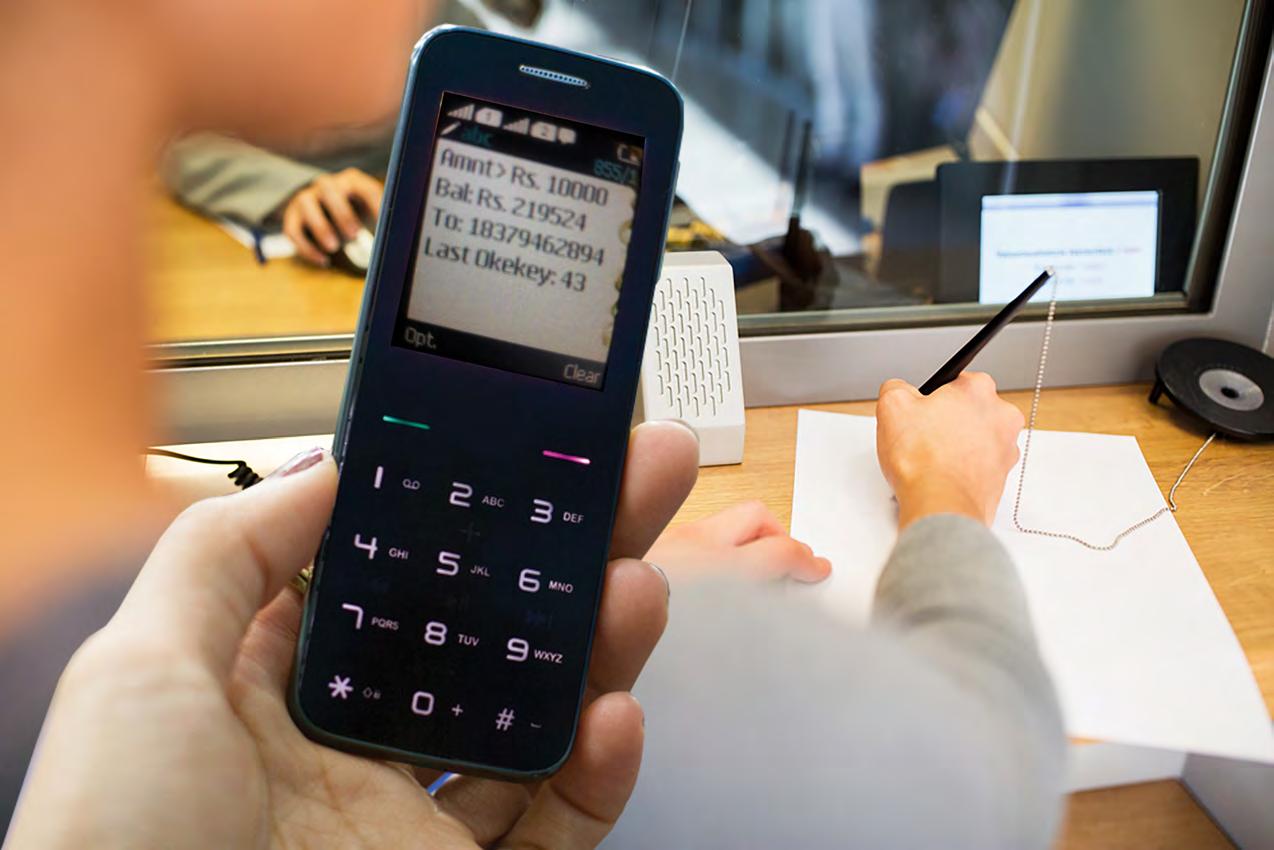

VRG has been extensively covered by Profit earlier and works on the principle of infrastructure sharing between banks and the telcos under a many-to-many model to power the Asaan Mobile Scheme of the central bank. Through partnership with banks and telcos, VRG has created that interoperability whereby users of any telecom operator can open an AMA account with any of the partner banks to carry out banking transactions on a USSDbased channel. (USSD channel allows operating a bank account on feature phones without the need of an active internet connection: think *111# to check your account balance on a Jazz sim). The interoperability is further amplified by the availability of the network of branchless banking agents of branchless banking players for cash-in and cash-out, and assisted banking services. This is a solid and inventive arrangement made possible by the third-party service provider (TPSP) regulations of the central bank. The bulk of the masses that are financially excluded either have a feature phone or don’t have an active internet connection which prevents them from getting formal financial services. Since all the telcos are involved, the outreach can increase massively to virtually anyone who has a cellphone, and multiple partner banks makes this arrangement the melting pot of financial inclusion.

VRG, being at the centre of creating the interoperability, makes money by charging telcos and banks for each transaction that is processed on the VRG platform. The company boasts about 4 million AMA accounts opened so far, and over 32 million transactions worth Rs31.9 billion processed on these accounts. These numbers have been achieved even before the commercial launch of the project.

For the first few years until January 2022, VRG was bearing all the costs on its own. Since the soft launch which allowed VRG to start charging partner banks and telcos, the CEO of the company, Salman Ali says that VRG has been able to successfully hit breakeven each month since, validating the success of their business model.

What makes VRG tick?

Aproactive central bank can work really well in your favour, but then it is working well in everyone else’s favour too. The SBP has been very aggressively pushing financial inclusion measures and has introduced numerous regulations for fintech players to enter and serve the unserved and underserved segments of the population. EMI regulations were introduced in 2019 for the same purpose and this year, the central bank announced the digital banks regulatory framework.

Both EMIs and digital banks would be out there to capture the unbanked and the underbanked. So if EMIs and digital banks would be out there to do what VRG would be out there to do as well, is there scope for VRG’s offering? Further, VRG’s case is based on the assumption that most of the financially excluded people use feature phones and have lack of access to the internet. What happens in case the number of smartphones increases?

Salman Ali allays these concerns saying that VRG will actually be a facilitator for EMIs as well as digital banks who want to have an outreach to the masses. “VRG’s offering is that it has the transactions acquired. We acquire the transaction and give it to any financial institution. So I am like a highway for them.”

RAAST is the highway on which fintech companies can build their offerings and what Salman means to say is that VRG would be a RAAST on top of RAAST for these fintech companies. The way VRG works is that an EMI like SadaPay or NayaPay can operate solo to offer financial services to say people in Lahore where more people are considered to have smartphones and better internet connectivity, and then partner with VRG for offering of financial services to people who don’t have better internet and smartphones, to increase their own users. VRGs users will instinctively increase when such partnerships consummate. “In Pakistan today, even on the motorway, there are areas where there is no internet. But AMA is working there. All these fintech companies operate in metro cities and have internet limitations for financial inclusion. So if any of these new entrants really want to reach out to the bulk of the unbanked, VRG can help them do that because the bulk of the unbanked can only be reached on the USSD channel,” Salman says.

As far as the number of smartphones increasing than feature phones, Salman says this does not, at all, limit the scope for VRG because then VRG will have an app itself which will be operational on smartphones. It’s just that this app will still be using the USSD technology instead of an active internet connection. So someone in a village moving to a smartphone but no internet connection, would still be able to operate an AMA account on his SadaPay app on that smartphone, which would be using VRG’s USSD technology to replace the internet.

Another proactive measure of the central bank that goes in VRGs favour is the introduction of RAAST. While RAAST makes transfers more instantaneous than the archaic IBFT system, the State Bank has mandated zero charges for consumers on RAAST. One of the reasons why less people have bank accounts is that banking is expensive. So if funds transfers are free under RAAST, the unbanked are more likely to be banked than if there is a fee on such transactions.

“RAAST is the biggest game changer. RAAST system was built to serve the masses. The fee is waived for these masses which cannot be tapped without a USSD based system.” So RAAST appears to be one of the positive measures by the SBP that helps increase financial inclusion and helps VRG’s chances of success because the financially excluded need free transfers and USSD based banking.

But the biggest threat, and what is perhaps going to be a poisonous sting which can give a death knell to VRGs business and the broader plans for financial inclusion, is exactly what is required to improve financial inclusion: no charges on RAAST and IBFTs.

Branchless banking agents of EasyPaisa and JazzCash are key for the TPSP arrangement, which created the VRG business model. People that use services of branchless banking agents use them for either one of the two reasons: cash-in and cash-out, or assisted banking services. The financially excluded are poor and not well educated, which is why they can not operate JazzCash and EasyPaisa wallets

on their phones and need services of branchless banking agents for funds transfers. These agents charge commission to users for these services. So if RAAST is free and IBFTs are also free for the majority of the transactions, branchless banking players would not be able to keep up these networks.

The growth in the network of branchless banking players is expected to slow down because of the reduction in IBFT charges. According to our conversation with branchless banking players, they are very interested in keeping the agent network intact. Branchless banking financial institutions provide liquidity to these agents and pay them commissions, and used to recover the costs and get some earnings from IBFT charges. In the absence of IBFT charges and zero-cost RAAST, branchless banking players are bleeding money to keep the agent network intact.

The numbers haven’t yet decreased but if money isn’t earned and burn rate is high, a decrease in agent network might be on the cards which will adversely impact the prospects of VRG as well. The branchless banking agents are the mainstay of these arrangements which replace bank branches that banks would not open in areas because it is a bad business case. If branchless banking agents also start decreasing in number, users would need to go to bank branches to open accounts and carry out transactions, because most of them would not be literate enough to operate bank accounts like AMA on their mobiles.

There is hope too, however. Covid-19 pushed the adoption of digital payments and according to Salman Ali, digital payments via the USSD channel also witnessed an uptake which means that people were forced to learn about digital payments during the pandemic which, by some quantum, would reduce the need for branchless banking agents for assisted banking services. Salman also asserts that even in case of a decrease in the number of branchless banking agents, the interoperability created by VRG increases the utility of a branchless banking agent and less number of agents would be able to handle more financial transactions, compared to a higher number of agents without interoperability. Add to that VRG is the only company that is creating this interoperability means it has the space all for itself to claim, though it needs the central bank to act generously for that to happen.

In January 2022, all banks were verbally informed of soft launch, and that there would be a commercial launch of the AMA scheme. While the soft launch has allowed VRG to charge banks and telcos after bearing the costs for years on its own, commercial launch will come with a SBP endorsed and backed marketing campaign which VRG believes is what they need to really take off the AMA scheme.

“The marketing campaign that is going to be run for 6 months is going to give AMA the real uptake. When it is launched successfully, AMA will propagate all over Pakistan,” says Salman.

Launching the marketing campaign for AMA can help the central bank attain its own goals of achieving financial inclusion quickly. The central bank has a goal of increasing, till 2024, 65 million new bank accounts - a target set under sustainable development goals. From a VRG perspective, if it has 4 million accounts right now, the marketing campaign will help it reach 20 million accounts fairly quickly than without a marketing campaign. And if this number is achieved because the central bank launched this campaign quickly, VRG would be better off, the central bank would be better off and the country would be better off.

This marketing campaign, estimated to have cost billions of rupees, will run TV ads propagating the AMA scheme. Since the AMA scheme is owned by the central bank itself, the marketing expenditures would be borne by the SBP too along with participation from commercial banks.

While VRG is set on its strategy to achieve its goals even if the marketing campaign hits a wall, its business goals would be achieved faster if the central bank goes ahead with the campaign. The quicker, the better. For instance, VRG has been testing the aforementioned application for smartphone users but wants to hold it from launching until there is some clarity on the marketing campaign. VRG believes, and rightly so, that if they are to introduce new features, they would be better off if there is better awareness of the AMA scheme which would be created by SBP marketing.

How would the funds be utilised?

The sponsors of the company have invested heavily to get VRG across through the hurdles, which not only include setting up the technology infrastructure and licensing, but also putting up with lobbying and court cases which delayed the launch and increased the costs. Now that the business is finally up and running, fundraising is part of the natural course of the business. Three years down now, VRG plans to raise Rs1.05 billion (approximately $5.5 million) from private equity investors against an equity giveaway of upto 10%.

The idea of raising VC funding was not shunned completely but a stable Pathfinder-group backed VRG perhaps did not fit the VC investors’ criteria of backing unstable companies to help them attain stability. The company, solely owned by Ikram Saigol, is majorly equity financed, with debt forming a very small portion, details of which were not disclosed to us.

“We are hosting aggregation of 13 banks and four telcos so our infrastructure needs to be robust to perform transactions in fraction of seconds. If transactions get lost, it is revenue lost for all the parties,” Salman says about the utilisation of funds. “At this stage, we have 4 million accounts and we are looking to expand our infrastructure in terms of computing, in terms of storage, in terms of capacity and with respect to human resources.”

While Salman laid out a few technicalities, he summed up why the investment was required: “I would say we need the new funding for growth capital where my infrastructure growth is required. This comes along with more licensing requirements.”

The company says that funds have been planned to be utilised for a period of 1-1.5 years, after which a new round could be considered. But the SBPs kindness with regards to helping with the uptake of AMA could help them achieve profitability sooner in which case a new fundraising might not be a consideration. While Salman appeared confident that raising these funds shouldn’t be a problem for the company, in case the push comes to shove, they would seek funds from other categories of investors, or lenders to go ahead and lead the company to achieve its targets. n