History Painting

November 7 – December 20, 2025

“I do not paint to explore history itself. History is merely a point of departure, a way for me to explore painting.”

Xin Wang

Let us boldly assert the following: historical discourse is never ‘born.’ It always recommences. And let us observe this: art history—the discipline which goes by that name—recommences each time.

GEORGES DIDI-HUBERMAN

In Li Songsong’s new series of paintings, titled History (2023–), legible visual references— historical or personal—have completely vanished. Treating each impasto mark as a unique character, he builds layers that stack, squeeze, and warp at their brims ever-tantalizingly away from the canvas. The pull of wide brushes creates lacerations across layers, exposing a porous mixture of color and texture. Where these formidable applications of paint used to mount to some recognizable imagery, a void emerges. This is paradoxical, unsettling even, as the series’s title—and the artist’s practice over the past 20 years— implies that a certain narrative haunts these otherwise abstract compositions. To be sure, Li is by no means pivoting to pure formalism, stating that he “simply let

the language extracted from painterly practice become the protagonist,” thus allowing “the formal qualities of ‘painting’ to form a historical metaphor.”²

But what exactly does he mean by that? In other words, how does he position himself to history, and how does that relationship implicate us?

A painting from the year Li first went “abstract” illuminates a few salient aspects of this trajectory. The Last Goodbye (2022; fig. 1) features a rather legible scene of a ballet: the famously synchronized choreography of “Dance of the Little Swans” from Swan Lake. The way the image fractures into varying depths, tones, textures, hence emotional tenor epitomizes Li’s distinct compositional logic. Here, it also reads like a glitch effect that bleeds—

ominously so in the legs and torsos. The impasto brushwork, another hallmark of Li’s style, literally drags against the movement it embodies and depicts. We are compelled, then, to be in suspense with the painting, grinding to a halt. The most fundamental yet elusive quality of Li’s work lies in his choice of imagery, which is often mediated, savored, sullied, and never a direct representation from life. When pushed to the threshold of legibility, these images are stripped of didactics; in their precise ambiguity, emotional resonance amplifies. In fact, any recognition of the subject barely commences our engagement with the work.

It would turn out that The Last Goodbye was informed by the final broadcast of Dozhd TV, Russia’s biggest

independent television channel that shut down in early 2022, when the country’s latest military aggression toward Ukraine began. The choice to broadcast Swan Lake was a potent provocation, as the ballet had repeatedly aired on state television during the deaths of Soviet leaders and, most famously, during the 1991 attempted coup against Mikhail Gorbachev (whom Li had also painted; the politician’s famous birthmark lends well to mark-making humor). Its association with political precarity and ends of regime—including that of the USSR itself—was not lost on the public. It is no coincidence, either, that the frame chosen by Li shows the dancers out of sync, relishing in the slow, subtle violence of it all.

The nuance with which the painting’s formal considerations entwine with the historical and political, as well as the roundabout way a viewer might recognize—if at all—the painting’s acute responsiveness to geopolitical events, are very much by design. Li is not interested in providing quick edification or commentary, though his training in a certain mode of realism (Chinese academicism by way of Soviet pedagogy) was well calibrated for that. Instead, he entrusts the painterly endeavor to a rich—and enriching—image, and its interpretation to the viewer’s own ways of knowing, feeling, and, indeed, forgetting within collective memory.

In a 2005 interview with fellow artist Ai Weiwei, Li explains that once he identifies a fitting image

as a work’s point of departure, he tries to “put the imagery out of mind… I would divide the painting into smaller segments, and while focusing on each area, I try to forget the whole; in fact I do strive to forget.”³ This strategy has offered more than opportunities for visual experimentation; it already functions as a metaphor for history: disjunctive, iterative, entropic. Already, a sense of detachment and withdrawal was operative in organizing both his paintings and, one suspects, his personal relationship to history. At the same time, what these references are clearly matters, whether they are derived from childhood memorabilia, public gatherings on a certain square (see fig. 2), Stalin on his deathbed, or known and unknown figures seen through the brutal theatrics

of politics. Sometimes the references can register too clearly to an individual despite all the painterly obscurations. In such cases, visceral reactions ensue: in 2022, when a Beijing visitor recognized a certain WWII image in one of Li’s paintings (on view in a rather innocuous summer group show), he filed a police report and further magnified his outrage online.

The curious incident speaks to an existential urge for moral clarity, from which Li himself has kept a cautious distance. In the same 2005 interview, he reflects that it is not his task to offer judgements toward history, nor does he feel adequately qualified for it: “I have my own opinions, but I don’t use my approach [to art] to say whether something is good or bad.”⁴ Li insists on escaping the grip of a narrow,

limited reading, as well as the tendency to attach those readings too steadfastly to visual information— a quiet resistance to the relentless, unspoken demand for artists to perform interpretative labor, especially when working in cross-cultural and political contexts. After all, where does one even begin with a context like China’s? While images of mass media can often be unreliable sources for truth, truthfulness may be gleaned from paying attention to the forms and mechanisms of mediation—an arguably universal experience. What appeals to Li is precisely this slipperiness of meaning and interpretation within the seemingly irrefutable visual residues of history.

History has always been a prime substance, if not subject, throughout Li’s practice; he works with

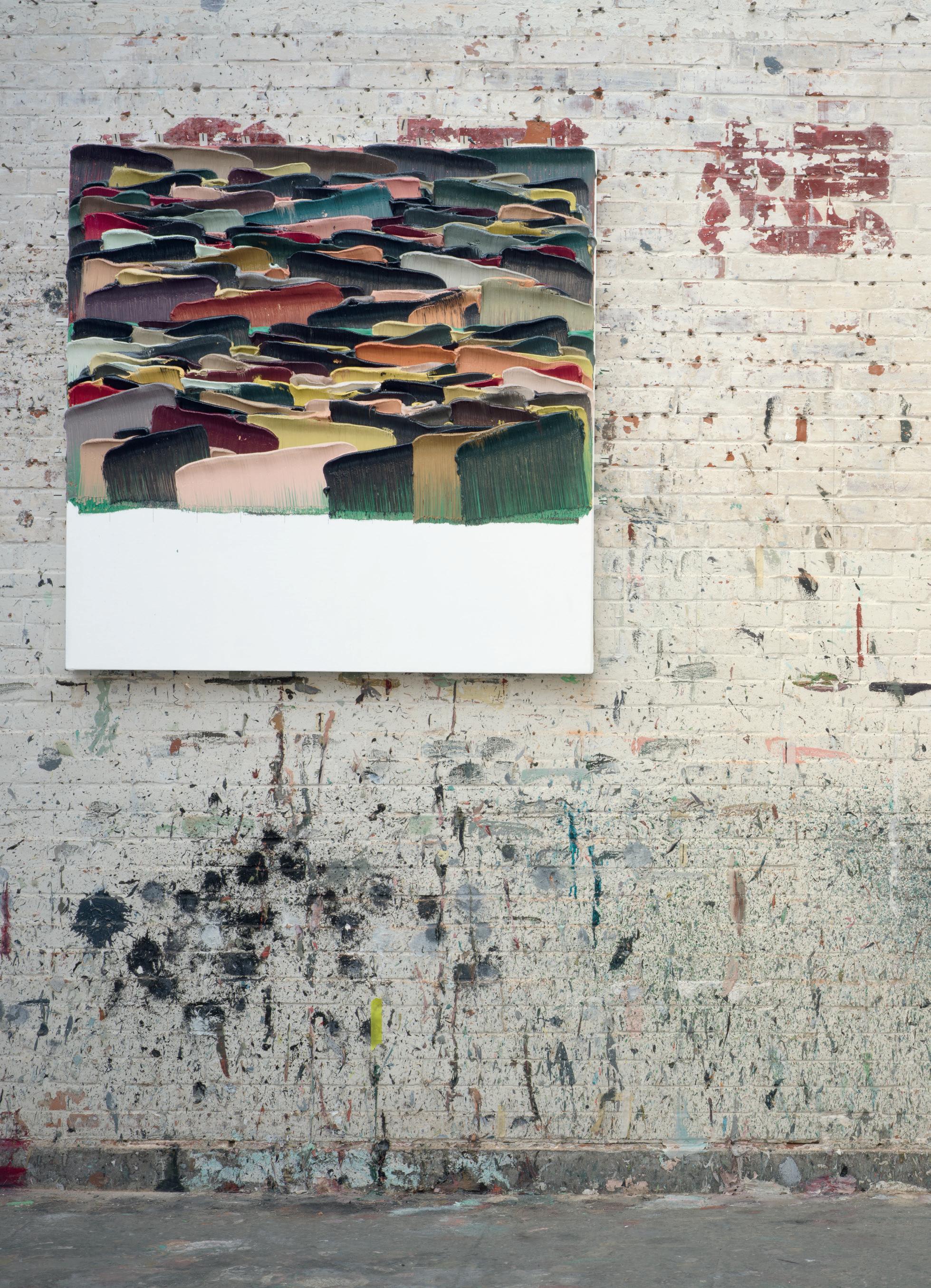

it not as evidence, but as symptom and pathos. It is not so jarring, then, that in his recent series explicitly titled The Past and History representational content has given way to the visceral and relational. Working from top to bottom with colors mixed fresh out of tube, Li does not touch or rework the layers that have already been laid on canvas, though accidents are often preserved. He sees agency in his brush strokes: “Every brush is complete, with its own character and fate; it’s as if each has a mission and responsibility.”⁵ The segments are still there, hidden from view but guiding the composition from underneath, much like the ideologically-charged features (faded Mao slogans on brick walls) in the Bauhaus-style studio where he has operated over the past 24 years

(see frontispiece). Echoing the paradoxical way that Li’s paintings simultaneously describe and obscure scenes, people, and the problematic evidence of history, this withdrawal from legibility is a gesture of resolve: to hold on, to ruminate, to pulp, to “give memory permanence”—as a new kind of history painting.⁶

1 Georges Didi-Huberman, The Surviving Image: Phantoms of Time and Time of Phantoms: Aby Warburg’s History of Art (Penn State University Press: 2002), 1.

2 Conversation between the artist and author in the artist’s Beijing studio, August 12, 2025.

3 Ai Weiwei, Feng Boyi, and Li Songsong, “Individual Expressions through the ‘Fragments’ of History,” Contemporary Artists, no. 1 (2005): 56.

4 Ibid.

5 Conversation between the artist and author.

6 Exhibition text for Li Songsong: The Past, Pace Gallery, 2024.

“In my work, every stroke takes on a clear role. I think of it as a drama. Each previous mark is pushed, altered, or covered by others with equal strength of will. Some remain in fragments; others are erased completely.”

“I have no preconception of what will appear on the canvas. Every new mark arrives with its own will, yet inevitably responds to what already exists, sometimes even defined by it. These decisions happen instantly, almost by chance. I watch things happen and try to keep that state.”

“I am the master of the painting, but not the one who arranges everything. The interaction of marks unfolds through time: they shift, clash, and collapse. At certain points, all the competing strokes may disappear, yet from the ruins a new order may appear.”

“These paintings are visual metaphors of history, like a form of simulation. Each stroke exists for the sake of existence itself. The process of accumulation follows a critical logic. Even what seems settled and comfortable may be overturned in the next moment.”

“Sometimes at the end of a day I feel satisfied, and the next morning I feel disappointed and doubt that feeling. I never set a goal. I only react to the reality before me when I am not satisfied, and proceed to change accordingly. Perhaps this cycle is based on my unwillingness to accept any instant sense of perfection.”

“If my earlier figurative works were a kind of deconstruction of history painting, my current work borrows its ‘shell’ while discarding the ‘crutch’ of imagery. Brush strokes are the only elements of the painting. Through their appearance and disappearance, they finally solidify into form, in the same way we capture history only through what has been seen.”

“As the one presiding over the painterly process, can I really stay detached and watch nonchalantly as things unfold? Of course not. I was responsible for every bit, good and bad. It reminds me of Mao’s words: make trouble, fail, make trouble again, fail again—that is the fate of the reactionaries.”

“Time is a threshold that cannot be crossed. It is universal and without privilege. Yet on the canvas it reveals a kind of unfairness, which belongs to the painter’s private mind. Sometimes much time is wasted. Sometimes something appears almost without effort. Later we may use words like ‘rhythm’ or ‘cadence’ to describe what was once awkward and confused. That is a kind of flattery.”

History VIII: Snake Year 2025

“When a person speaks or forms sentences, they might first convince themselves. My work is also a process of convincing myself, otherwise it cannot continue. At the opportune moment, one must compromise. This means all the previous struggles and mischief become part of the ongoing process. You are the first to accept all of this, including the moral question that comes with it.”

“The subtitles of the History series, when there are any, are always added after the work is completed. They have no role in the making of the painting. They may reflect the artist’s state of mind at a certain time, but they are independent from the work itself.”

“While wrestling with the History series, I began to conceive another painting that does not belong to it. Within the picture there exists a certain ‘subject.’ Therefore, I set boundaries and divided areas for it, and within this framework the brush strokes grew in an opportunistic way. Each movement of the brush must both acknowledge its responsibility to the vague ‘subject’ and exercise its own right to existence. This painting is Boundless Longevity.

Now that the painting is finished, it reminds me of the ‘scholar’s rocks’ venerated in Confucian culture. I once saw the largest one in the Summer Palace in Beijing. It was presented as a birthday tribute to the Empress Dowager. All the surrounding buildings bore plaques with auspicious inscriptions, and the most prominent among them read Boundless Longevity. I took that phrase as the title of my painting.”

History IV: Sacrifice

2024 oil on canvas

47 ¼ × 47 ¼" 120 × 120 cm

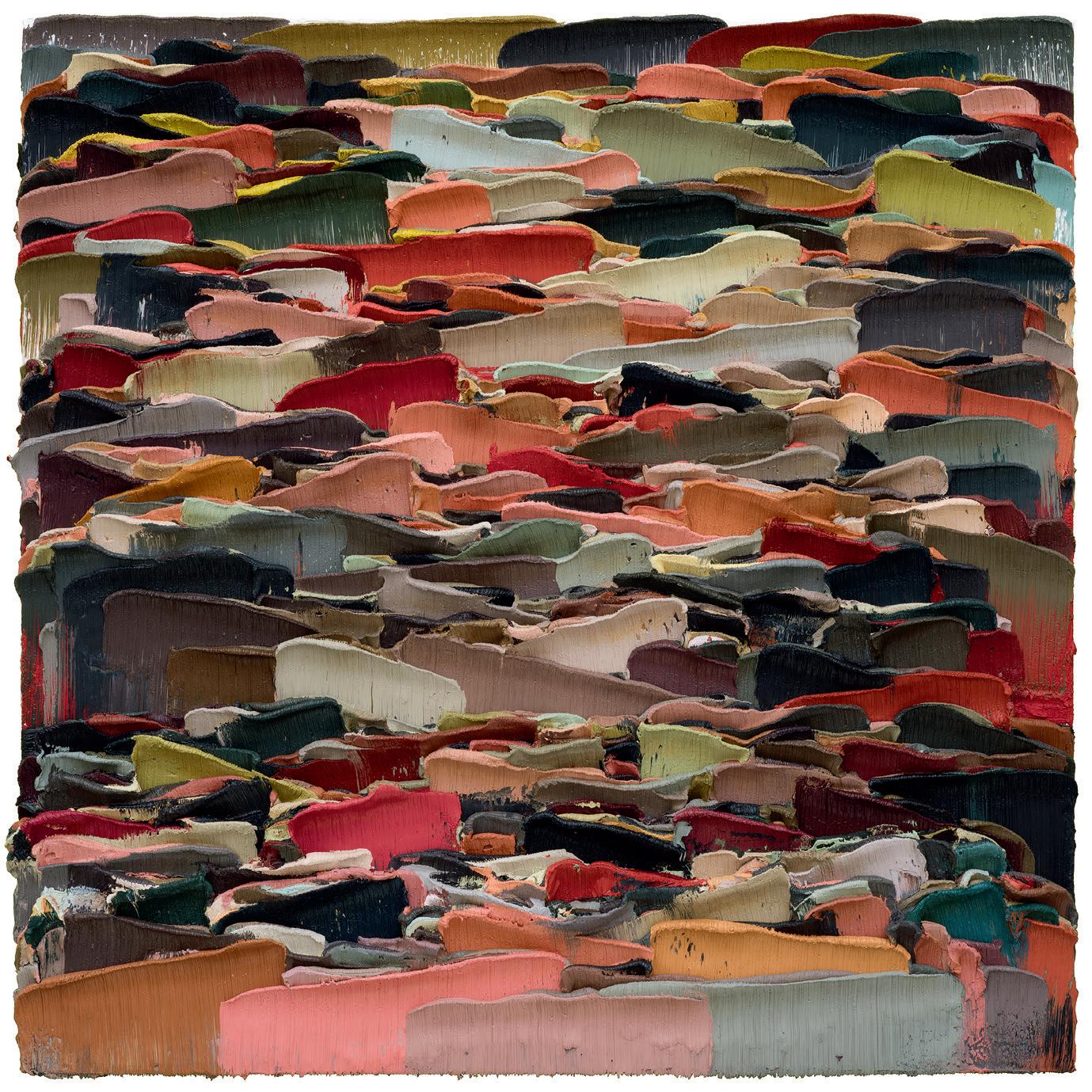

History V: Revolution 2025 oil on canvas

82 ⅝ × 82 ⅝" 210 × 210 cm

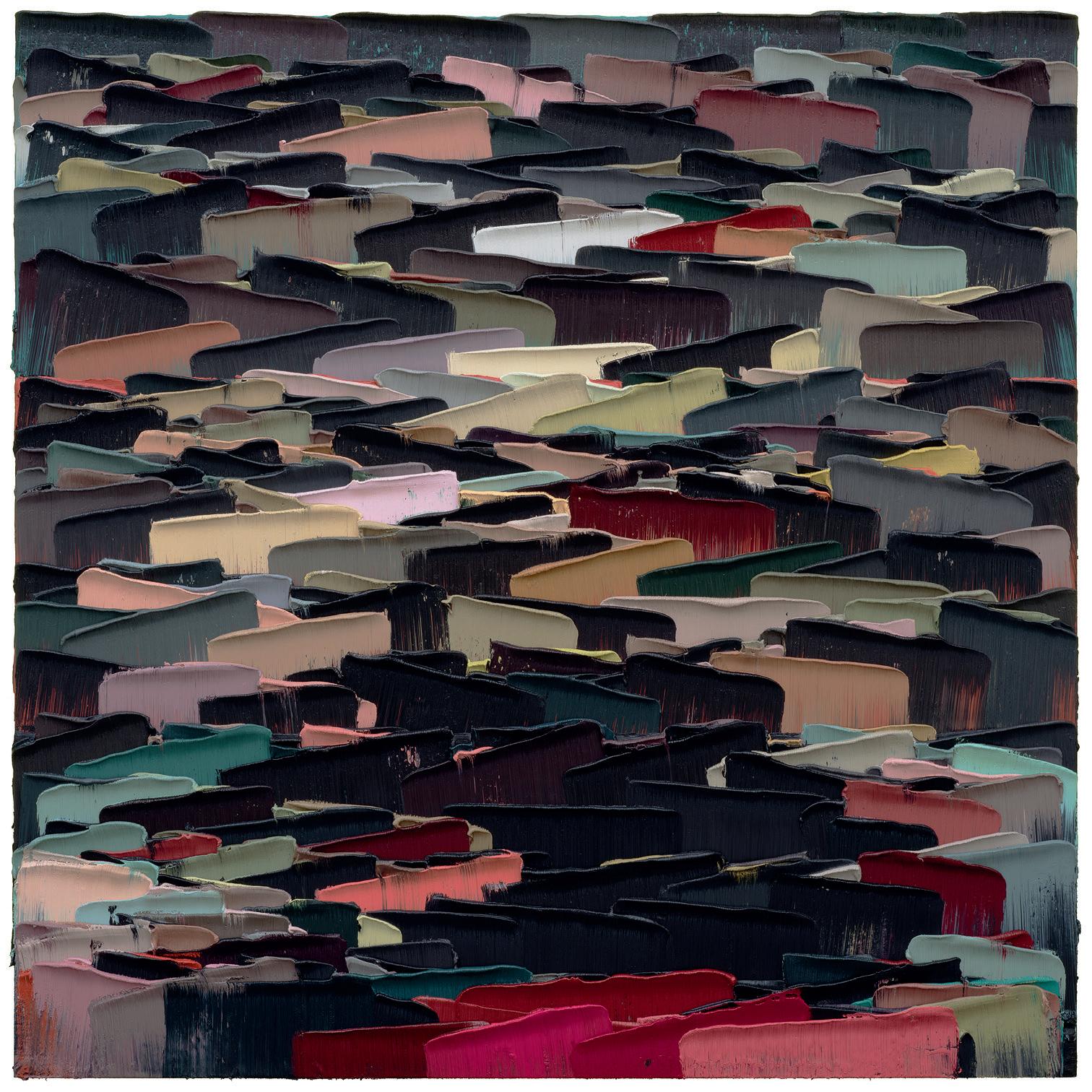

History X: Leviathan 2025 oil on canvas

82 ⅝ × 82 ⅝" 210 × 210 cm

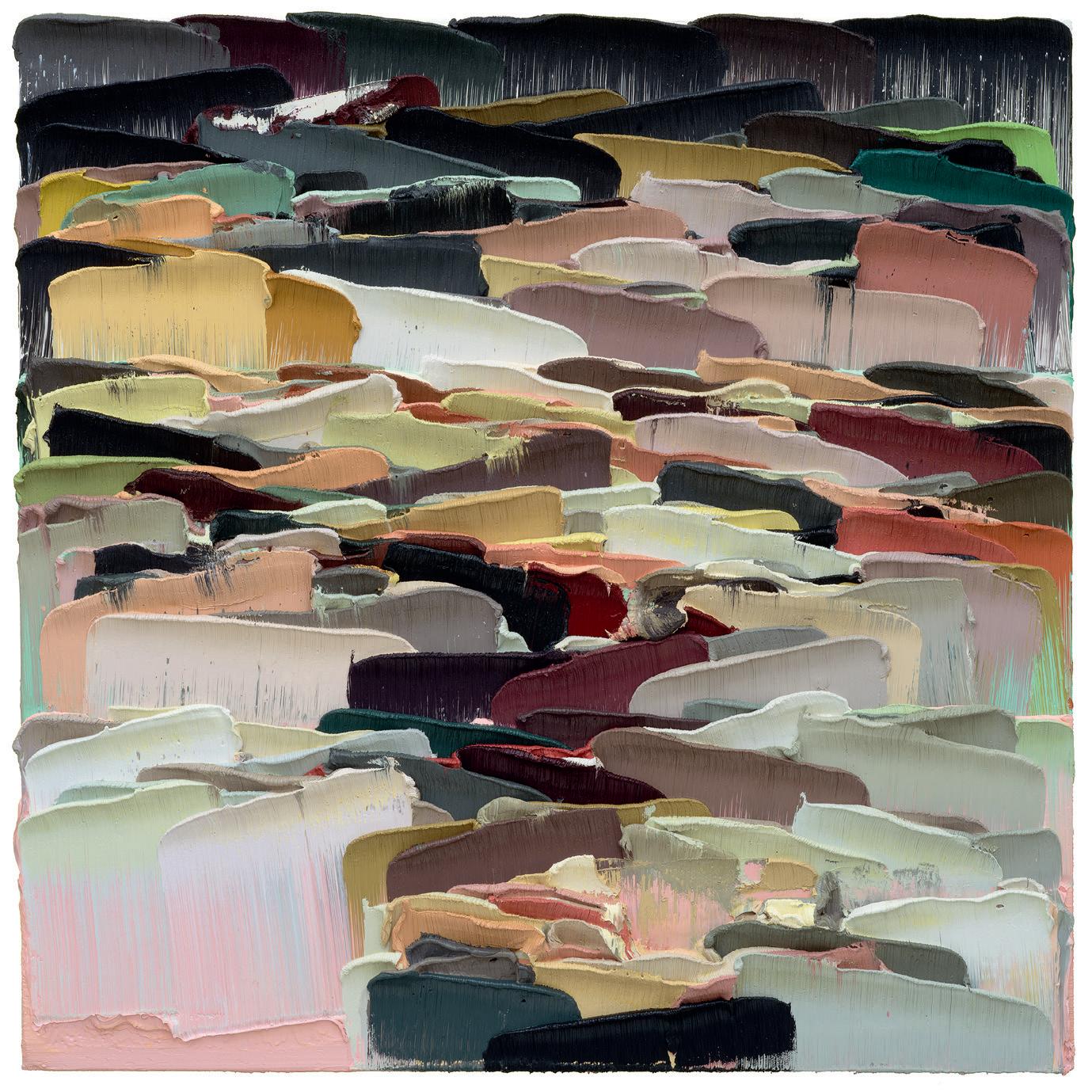

History VI: Appeasement 2025 oil on canvas

47 ¼ × 47 ¼" 120 × 120 cm

History VII: Pity

2025 oil on canvas

47 ¼ × 47 ¼" 120 × 120 cm

History VIII: Snake Year

2025 oil on canvas

47 ¼ × 47 ¼" 120 × 120 cm

History IX: Mercy

2025 oil on canvas

47 ¼ × 47 ¼" 120 × 120 cm

Boundless Longevity 2025 oil on canvas

82 ⅝ × 106 ¼" 210 × 270 cm

Published on the occasion of Li Songsong

History Painting

November 7 – December 20, 2025

Pace Gallery

540 West 25th Street

New York

Publication © 2025 Pace Publishing Artworks by Li Songsong © Li Songsong Quotations by Li Songsong throughout

Text by Xin Wang © 2025 Xin Wang

Text by Li Songsong © 2025 Li Songsong

Dust jacket: History V: Revolution, 2025 (detail)

pp. 2–3: Li Songsong’s studio

p. 46: History IX: Mercy, 2025, in Li’s studio (detail)

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Every reasonable effort has been made to identify owners of copyright. Errors or omissions will be corrected in subsequent editions.

Photography: All images courtesy the artist.

Creative Director: Tomo Makiura

Design Director: Tara Stewart

Design: Alexis Liebes

Production: Paul Pollard

Editor in Chief: Gillian Canavan

Editorial Manager: Madeline Gilmore

Rights & Reproductions: Vincent Wilcke

Printing: Meridian Printing, East Greenwich, Rhode Island

Typeset in Plantin

ISBN: 978-1-948701-84-6