PUBLISHED IN PARTNERSHIP WITH THE UNIVERSITY OF CENTRAL ARKANSAS A MAGAZINE OF THE SOUTH FALL 2022 CELEBRATING 30 YEARS

HOTEL KANSAS CITYTHE FABULOUS FOX THEATRE, SAINT LOUIS PERFORMING 2 HOTEL KANSAS CITYTHE FABULOUS FOX THEATRE, SAINT LOUIS ICONIC STAYS. THAT’S MY M-O.SHOWTIME.THAT’SMYM-O. ARTSPERFORMINGMO MOCULTURE

THERE’S A MO FOR EVERY M-O. FIND YOURS. 1860 SALOON, SAINT LOUIS LIVE MUSIC MO THERE’S A MO FOR EVERY M-O. FIND YOURS. 1860 SALOON, SAINT LOUIS SOULFUL SOLOS. THAT’S MY M-O. LIVE MUSIC MO

southernenvironment.org Petracca©LaurenWolfeLynne©Mary Bowery©Nate

We are the Southern Environmental Law Center, one of the nation’s most powerful defenders of the environment, rooted right here in the South. As lawyers, policy and issue experts, and community advocates and partners, we take on the toughest challenges to protect our air, water, land, wildlife and the people who live here. We can solve the most complex environmental challenges right here in the South.

Solutions start in the South.

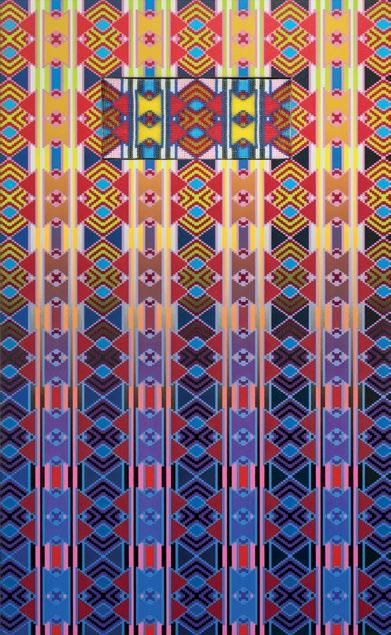

4 FALL 2022 Cover: THE FUTURE IS PRESENT, 2019. Digital print, silkscreen, collage, gloss varnish, custom color frame, by Jeffrey Gibson (Mississippi Band of Choctaw, Cherokee) © The artist. Courtesy Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York; Kavi Gupta Gallery, Chicago; Roberts Projects, Los Angeles; Stephen Friedman Gallery, London FEATURES 60 WHERE THE ANIMALS SLEEP AT NIGHT A story by Meghan Reed 66 UNDETERMINED CIRCUMSTANCES Disappearance and discovery in American waters by D. T. Lumpkin 74 EL COQUÍ SIEMPRE CANTA Listening for the ambient sounds of home by Maria Sherman 80 POEMS Diptychs by Mikey Swanberg and Erika Meitner 88 FIFTY-SEVEN DOLLARS An excerpt from Maybe We’ll Make It: A Memoir by Margo Price 92 RASHIDA A story by Elias Rodriques 102 EASTMAN, GA. 2022 A search for a Southern past by Farah Jasmine Griffin ART BY Jeffrey Gibson, Adrienne Elise Tarver, Yatika Starr Fields, Peter Fisher, Eliot Greenwald, Arghavan Khosravi, Bear Allison, Melanie Willhide, Margaret Curtis, Charlie Boss, Miranda Bruce, Pableaux Johnson, Luis Lazo, Rae Klein, Renee Hannis, WC Bevan, Curran Hatleberg, Rachel Boillot, Jewel Ham, Georgette Baker, Mahsa Merci, Elijah Gowin 08 Editor’s Letter: To The West by Danielle A. Jackson POINTS SOUTH 14 The Mustang, by Gwen Thompkins 18 Cavities and Debris, a story by Melody Moezzi 22 Stumbling Stone, by Benjamin Hedin 26 Marble City Mourning, by Mariah Rigg 32 Wednesday in Athens, by Patrick D. McDermott 36 The Spirit of the Bend, by Jarrett Van Meter 42 Sting Like a Bee, by Leslie Pariseau OMNIVORE 116 COMING UP FANCY The ever-expanding identity of a Southern gothic epic by Jewly Hight 124 HOPE AFTER “DOPESICK” An interview with Beth Macy Q&A by Carter Sickels 128 FROM THE WEB Stories by Mary Edwards and Osayi Endolyn AMERICANOXFORD FALL2022

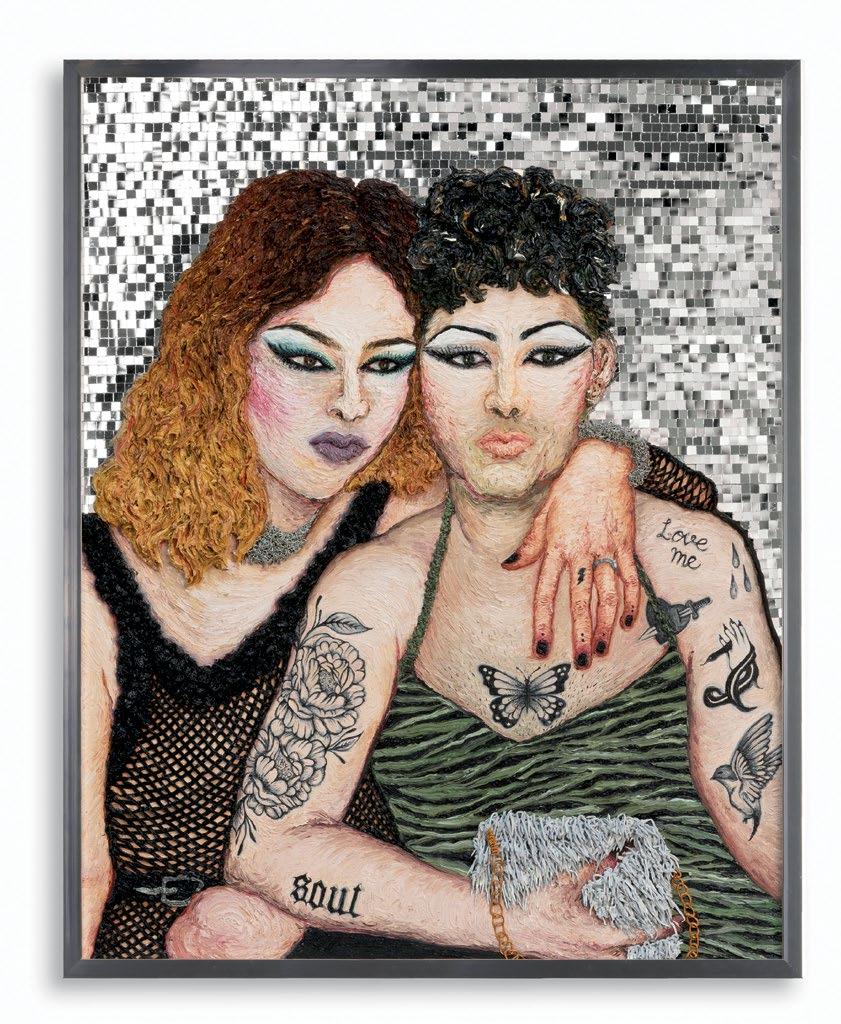

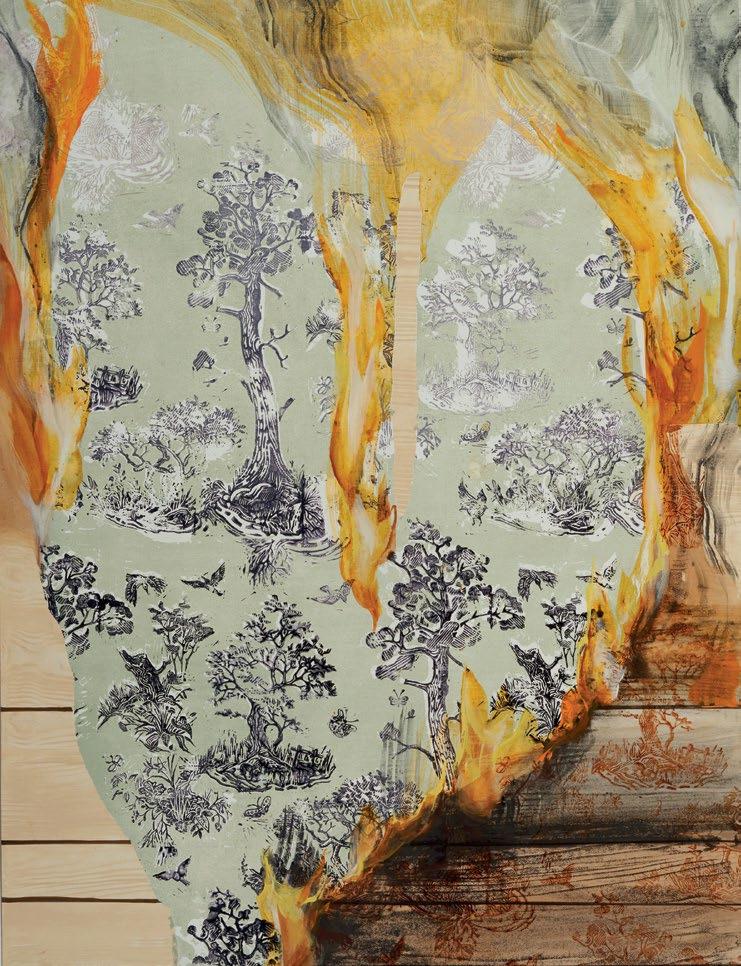

OXFORDAMERICAN.ORG 5 Copyright © 2022 The Oxford American Literary Project, Inc. All rights reserved. The Oxford American (ISSN 1074-4525, USPS# 023157) is published four times per year, Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter, by The Oxford American Literary Project, Inc., P.O. Box 3235, Little Rock, Arkansas 72203. Periodicals postage paid at Conway, AR Postmaster and at additional mailing offices. The annual subscription rate is $39 for U.S. orders, $49 for Canadian orders, and $59 for outside North America. (All funds must be U.S. dollars.) POSTMASTER: please send address changes to The Oxford American, P.O. Box 3000, Denville, NJ 07834-3000, or e-mail subscriptions@oxfordamerican.org, or telephone (800) 314-9051. For list rental inquiries, contact Kerry Fischette at (609) 580-2875 or kerry.fischette@alc.com. Advertising, editorial, and general business information can be obtained by calling (501) 374-0000. “Oxford” and “Oxford American English” are registered trademarks of Oxford University Press, which is not affiliated with The Oxford American Literary Project, Inc. We use the title with their permission. Printed in the USA Weary As I Can Be, 2021. Oil on canvas by Adrienne Elise Tarver. Courtesy the artist

LESLIE PARISEAU is a writer and editor in New Orleans. She is a co-founder and features editor at PUNCH, and has written for the New York Times, the Los An geles Times, GQ, the Ringer, the Intercept, and Jacobin, among others. Pariseau holds an MFA in fiction from Hunter College. MARGO PRICE is a Artist,edreleasedsinger-songwriter.Nashville-basedShehasthreeLPs,wasnominatforaGrammyforBestNewperformedon

CARTER SICKELS is the author of the novel The Prettiest Star (Hub City), winner of the 2021 Southern Book Prize and the Weatherford Award for Appa lachian Fiction. His debut novel, The Evening Hour, was adapted into a feature film that premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in 2020 and is now streaming. His writing appears in the Atlan tic, Poets & Writers, BuzzFeed, Guernica, Joyland, and Catapult. Sickels teaches at Eastern Ken tucky University.

Saturday Night Live, and is the first female musician to sit on the board of Farm Aid. MEGHAN REED is a proud Southern writer born and raised in Little Rock, Arkansas. She holds an MA from Mississippi State University, where she was associate editor of the national literary journal the Jabberwock Review. She is a mid dle-school teacher who instills in her students a love of travel and good Originallybooks. from Honolulu, Hawai‘i, MARIAH RIGG is a Samo an-Haole writer and educator. She has an MFA from the Univer sity of Oregon and is currently a PhD student at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville. Her work has been published or is forthcoming in the Cincinnati Review, Puerto del Sol, Joyland, and elsewhere. She is a fiction editor at TriQuarterly and the nonfiction editor at Grist, a Jour nal of the Literary Arts.

OXFORD AMERICAN 6 FALL 2022

ERIKA MEITNER is the author of six books of poems, including Holy Moly Carry Me, which was the winner of the 2018 National Jewish Book Award in poetry and a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award, and Useful Junk (BOA Editions, 2022). She is a professor of English at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

MARIA SHERMAN is a music and culture journalist living in

MELODY MOEZZI is an IranianAmerican Muslim activist, attorney, award-winning author, and visiting associate profes sor of creative writing at UNC Wilmington. Her latest book is The Rumi Prescription: How an Ancient Mystic Poet Changed My Modern Manic Life, which earned her a 2021 Wilbur Award. She is also the author of Haldol and Hyacinths: A Bipolar Life and War on Error: Real Stories of American Muslims. She lives in coastal North Carolina with her husband, Matthew, and their ungrateful cats, Keshmesh and Nazanin.

D. T. LUMPKIN recently returned to his home near Nashville, Tennessee, with his wife and two daughters after living for three years in London. His recent work has appeared in the Sun and Five Points. He is working toward his PhD in creative writing at the University of Georgia.

FARAH JASMINE GRIFFIN is the William B. Ransford Professor of English and Comparative Literature and African American Studies at Columbia University, where she also served as the inaugural chair of African American and African Diaspora Studies. Griffin received her BA in history and literature from Harvard and her PhD in American studies from Yale. She is the author or editor of eight books, including Read Until You Understand: The Profound Wisdom of Black Life and Literature (W.W. Norton, A2021).frequent contributor to the Oxford American , BENJAMIN HEDIN is the author, most recent ly, of a novel, Under the Spell. He also produced a forthcoming documentary about Indigenous reparations, Lakota Nation vs. United States Nashville-based critic and jour nalist JEWLY HIGHT is a frequent contributor to National Public Ra dio and NPR Music. Her work also appears in the New York Times and numerous other outlets. She was the inaugural winner of the Chet Flippo Award for Excellence in Country Music Journalism, and helped launched WNXP, the all-music public radio station in her city, as editorial director. She last wrote for the Oxford Ameri can in 2017.

ELIAS RODRIQUES is an assistant professor of African American Literature at Sarah Lawrence College and an assistant editor at n+1 . His writings have ap peared or are forthcoming in the Guardian, the Nation, The Best American Essays 2022, and other publications. His first novel is All the Water I’ve Seen Is Running

butorscontri-

PATRICK D. M c DERMOTT is a writer and editor whose work has ap peared in the Fader, Stereogum, and Nylon, among other places. He has an MFA in creative non fiction from the University of North Carolina Wilmington and is working on his first book.

GWEN THOMPKINS is a journalist, writer, and native of New Orleans. Since 2012, she has been the executive producer and host of the public radio program Music Inside Out, which showcases the unusually varied musical land scape of Louisiana. She is also the New Orleans correspondent for WXPN’s World Café. Thompkins was the longtime senior editor of NPR’s Weekend Edition with Scott Simon and later NPR’s East Africa bureau chief, based in Nairobi, Kenya. Currently, she is writing a book based on the Music Inside Out interviews. Find the full archive at: musicinsideout.org.

MIKEY SWANBERG is the author of On Earth as It Is (Vegetarian Alcoholic Press) and Good Grief (VAPress). He received his MFA from the University of Wisconsin–Madison, and he lives in Chicago.

JARRETT VAN METER is a writ er originally from Lexington, Kentucky. He currently lives in Asheville, North Carolina, and is enrolled in the University of Georgia’s narrative nonfiction MFA program. Brooklyn, New York. Her first book, LARGER THAN LIFE: A History of Boy Bands from NKOTB to BTS , out on Hachette imprint Black Dog & Leventhal, is currently being adapted into a docu mentary film by director Gia Coppola, Jason Bateman's Aggregate Films, and the Oscar-nominated studio XTR.

OXFORDAMERICAN.ORG 7

Diving Birds of Green Lake, 2016. A painting by Yatika Starr Fields. Courtesy the artist and Garth Green Gallery

EDITOR’S LETTER

BY DANIELLE A. JACKSON

To the West

n a fourth-grade class on Tennessee history, we learned about the state’s three grand divisions, so distinct one wanted to go its own way during the Civil War. We knew Memphis was westernmost. We were topograph ically unique: flatter, more swamp-like, with rainy seasons like the tropics. We were tethered to Mississippi, the state and the river, and to the eighteen counties of the Delta. Which meant we looked and ate and sounded more like Mississippi than most of Tennessee. We made barbecue, moonshine, Tina Turner, C. L. Franklin. A tambourine and a palm, a double-time piano, a worried line cooed over a bottom-heavy blues.

I

On a school trip to St. Louis, we learned the city calls itself the “gateway to the west.” Texas, we were told, is bifurcated by the ninety-eighth meridian, which signifies the start of the nation’s westward sprawl. Our part of the South and the West were geographic neighbors, energetic kin—kissing cousins, if you will, sharing land mass and waterways and a constant exchange of people. The borders between us are soft, elastic, permeable. Our generation played Oregon Trail on Apple IIes and read Willa Cather, whose childhood move from northern Virginia to the plains of Nebraska inspired My Ántonia, a novel I would come to love. My father lived in the Arkansas town where Howlin’ Wolf had been a radio jockey. Back then, the cities just across the river had a reputation. They were raucous, a kind of “wild, wild West” with gambling and fun, untamed parties. They courted an association with the Rhodafrontier.Bell,my great-grandmother, was born enslaved near Sel ma. She went west, to Mississippi, when freedom came. There were forests to clear, cotton to tend to, silt-rich soil in which to plant. When Thomas Moss, a postman and co-owner of People’s Grocery near Memphis, was pursued by a lynch mob, his final utterance, according to Ida B. Wells, was, “If you will kill us, turn our faces to the West.” Later, Wells told an audience: Hundreds left on foot to walk four hundred miles between Memphis and Oklahoma. A Baptist minister went to the territory, built a church, and took his entire congregation out in less than a month. Another minister sold his church and took his flock to California, and still another has settled in Kansas.

8 FALL 2022 nosimplewordfortime

During a speech at Brown, Ralph Ellison echoed Wells. “Freedom was…to be found in the West of the old Indian Territory,” he said. El lison was born in Oklahoma City to parents from South Carolina and Georgia. Maybe some found freedom, for a time: before the massacre in Tulsa? Storytelling about the West is often sentimental, sweeping, fanciful, a rosy impression only slightly connected to reality. Memphis became a city because the Chickasaw ceded their bluffs— four wooded, rugged hills formed by the meanders of the Mississippi that were dense with green and rich loess soil. Most of Middle and West Tennessee had been carved out of a series of treaties and land grabs by the American government, culminating in Congress’s In dian Removal Act of 1830. People who were Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole and made their homes east of the Mississippi were required to relocate, along with their black slaves, to unorganized territory west of Missouri. Over the next two de cades, more than sixty thousand former residents of the Southeast traveled treacherous routes west, through north Georgia, Alabama, middle and western Tennessee, southern Missouri, and almost all of Arkansas. While researching Democracy in America, Alexis de Tocqueville saw the scene in Memphis. “I saw them embark to pass , 2022. Screen print on Arches 88 mounted to mat board with inlaid panel of handwoven beadwork, by Jeffrey Gibson. Edition of 24; 24.5 x 15 inches. © Jeffrey Gibson, courtesy of Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York; Kavi Gupta Gallery, Chicago; Roberts Projects, Los Angeles; Stephen Friedman Gallery, London

OXFORDAMERICAN.ORG 9

DANIELLE A. JACKSON Editor Digital Editor VERONICA ANNE SALINAS Assistant Editors CHRISTIAN LEUS, ALLIE MARIANO, JULIA THOMAS Editor-at-Large ROSALIND BENTLEY Poetry Editor REBECCA GAYLE HOWELL Art Directors CARTER/REDDY • www.CarterReddy.com Art Researcher ALYSSA ORTEGA COPPELMAN Copyeditor ALI WELKY Editorial Interns ANDREW BRANNON, ALICE BERRY, GRACE CAPOOTH Contributing Editors LUCY ALIBAR, REBECCA BENGAL, ROY BLOUNT JR., WENDY BRENNER, KEVIN BROCKMEIER, BRONWEN DICKEY, LOLIS ERIC ELIE, BETH ANN FENNELLY, LESLIE JAMISON, HARRISON SCOTT KEY, KIESE LAYMON, JESSICA LYNNE, ALEX MAR, GREIL MARCUS, DUNCAN MURRELL, CHRIS OFFUTT, AMANDA PETRUSICH, PADGETT POWELL, JAMIE QUATRO, DAVID RAMSEY, DIANE ROBERTS, ZANDRIA F. ROBINSON The Oxford American Literary Project, Inc., Board of Directors Chairman SARA A. LEWIS RICHARD MASSEY, JENNY DAVIS, ENJOLIQUÉ A. LETT, DANIELLE A. JACKSON SARA A. LEWIS Executive Director Advertising Sales Director KEVIN BLECHMAN (678) 427-2074 • kblechman@oxfordamerican.org Senior Account Executive KATHLEEN KING (501) 944-5838 • kking@oxfordamerican.org Senior Account Executive CRISTEN HEMMINS (662) 801-5357 • cristenhemmins@gmail.com Senior Account Executive RAY WITTENBERG (501) 733-4164 • rwittenberg@oxfordamerican.org Marketing and Communications Manager KELSEY WHITE Accounting Manager SHAVON TAYLOR Development Coordinator AMANDA BOLDENOW Engagement Editor LAURA DALEY Creative Consultant RYAN HARRIS Fulfillment Coordinator SARAH GRAHAM The Oxford American Literary Project, Inc., receives support from THE NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE ARTS, THE NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE HUMANITIES, AMAZON LITERARY PARTNERSHIP, ARKANSAS ARTS COUNCIL, ARKANSAS HUMANITIES COUNCIL, AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORY COMMISSION, THE DEPARTMENT OF ARKANSAS HERITAGE, THE JULIA CHILD FOUNDATION FOR GASTRONOMY AND THE CULINARY ARTS, STELLA BOYLE SMITH TRUST, THE WINDGATE FOUNDATION, AND THE COMMUNITY OF LITERARY MAGAZINES AND PRESSES SUBSCRIPTIONS The quickest, greenest way to subscribe is to visit our website. A one-year subscription (4 quarterly issues) is $39. www.oxfordamerican.org/subscribe • (800) 314-9051 SUBMISSIONS We accept online submissions. Please visit our website for more information. ABOUT US The Oxford American is a nonprofit quarterly published by The Oxford American Literary Project, Inc., in alliance with the University of Central Arkansas (UCA). OFFICE ADDRESS P.O. Box 3235 / Little Rock, AR 72203-3235 Phone: (501) 374-0000 Business Staff: info@oxfordamerican.org Editorial Staff: editors@oxfordamerican.org the mighty river,” he wrote. “No cry, no sob was heard among the assembled crowd: all were silent.”

The 2020 Census reported growth among every non-white group of residents in the U.S., including Indigenous households.

The state parks’ association says Arkansas is “the only state that witnessed the removal of all five of the Southeastern tribes as they moved west.” Pinnacle Mountain, just west of Little Rock, was a key site along the Trail of Tears.

The balmy December I last saw my father alive, we drove past Pacaha burial mounds near the Hopefield Bend Revetment, a levee on the Mississippi’s Arkansas side. He told me a DNA test had revealed an Indigenous ancestor from the 1700s. He din writes, “So much of what is written about the Cherokees tends to emphasize removal.” We should remember that the American South has reams of Indigenous history, dead and alive, to recover, and honor, and connect with.

In this issue, frequent OA contributor Benjamin Hedin notes that Quatie Ross, wife of Chief John Ross, head of the Cher okee Nation at the time of removal, is buried in Little Rock’s Mount Holly Cemetery. The legends say she died nearby, on the Trail from Georgia, after giving up her sole blanket to keep a young fellow traveler warm. Hedin speaks to a descendant of Chief Ross and visits the headquarters of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, which sits on the western end of North Carolina. The story, about a soon-to-be published census of the Cherokee Nation before removal, speaks to loss, journeys, place-making, and also what, and who, remains.

Other stories in the issue similarly reflect on journeys, loss, and the resonant joy that can be found in Southern place-mak ing. Farah Jasmine Griffin travels to the town in middle Georgia where her grandmother grew up. With her immediate family, Ms. Willie Lee Carson had moved North, to Philadelphia, and was less than willing to speak at length about where she’d come from. Still, Griffin says, “the South, embodied in my grandmother, held us together.” Maria Sherman writes about the song of coquis as part of the living soundscape of Puerto Rico, her own ancestral home. Jarrett Van Meter, in his OA debut, travels to a part of Kentucky along the state’s border with Tennessee that is often, quite literally, left off from most maps of the state. He finds a close-knit cluster of families, a beautiful, expanding land mass, and the freshest, best-tasting catfish he’s ever encountered.

“The sun never knew how wonderful it was,” Louis Kahn once said, “until it shone on the wall of a building.”

The issue also features two pairs of poems, by Mikey Swan berg and Erika Meitner. I love what Meitner writes about space, place, and the human body: What does it mean to be almighty with joy of discovery? We can’t sense space without light.

We’re proud to present wise and delightful short fiction from Elias Rodriques, Melody Moezzi, and the debut of Meghan Reed of Little Rock. “Where the Animals Sleep at Night,” an enticing mélange of magical realism and traditional realism, caught our eye because of its beautiful sentences, its surreal moodiness, and what it had to say about home, adventure, exile, and the utter unknowability of other people.

Thank you for carrying us through thirty years and

Donations of any amount make a difference. We appreciate all of our readers, subscribers, and supporters. The names of every donor who makes a contribution by October 1st will be printed in the next issue. helping celebrate

the next thirty! NOWDONATETOSCAN $1000 • Membership in the OA Society • One-year subscriptiongift to the Oxford American • Texas Love Letter LP (while supplies last) • A lifetime subscription $250+ • Membership in the OA Society • One-year subscription to the Oxford American • One-year gift subscription to the Oxford American • Texas Love Letter LP (while supplies last) $100+ • Membership in the OA Society • One-year subscription to the Oxford American KEEP SOUTHERN MEDIA ALIVE & INDEPENDENT Do you want to hear a good story? Donating to the OA keeps independent media alive. Subscriptions only cover 12% of the cost to create the magazine you love. That means we need your support. Want to see the OA thriving for 30 more years? Then please donate today. Your support comes with great perks: LOVETEXASLETTER LP

OXFORDAMERICAN.ORG/DONATE When you give to the OA, you support Southern writers and artists who chronicle the vitality of our region and trouble harmful stereotypes. You also support one of the few nonprofit Southern literary organizations with queer women and women of color at the helm. Dr. Sara A. Lewis and Danielle A. Jackson have a vision for the OA’s next thirty years. What does this vision look like? It looks like reframing the narratives told by and about the South in the words of Southerners themselves, with a purposeful shift toward more stories by writers of color, queer writers, disabled writers, and writers historically excluded from the canon. In addition to amplifying more Southern voices, the OA is committed to broadening our readership by providing free copies of each issue to underserved communities, including students, rural reading groups, and incarcerated readers. Your contribution makes this work possible.

us

PUBLISHER’S CIRCLE Contributions of $5000 or more in the past year African American History Commission · Amazon Literary Project with the Community of Literary Magazines & Presses · Arkansas Arts Council · Arkansas Humanities Council · Ruth & Thomas Cross · Julia Child Foundation for Gastronomy & the Culinary Arts · Massey Family Charitable Foundation · National Endowment for the Arts · National Endowment for the Humanities · Poetry Foundation · Redwine Family Foundation, Inc. · Richard “Disceaux Dicki” Sheeren · Stella Boyle Smith Trust · The Watson-Brown Foundation · Windgate Charitable Foundation · University of Central Arkansas · Winthrop Rockefeller Foundation EDITOR’S CIRCLE Contributions of $1000 or more in the past year Anthony Arrigoti · Houston & Jenny Davis · William Isaacson · Connie & Samuel Pate · Keith Pryor · Matthew P Quilter · R&B Feder Charitable Foundation · Thomas & Janice Wilson LITERARY CHAMPIONS Contributions of $250 or more in the past year Sidney Ansbacher · Irwyn Applebaum · Colleen Bartlett · Charles Beach · Michael Berkshire · Xavier Beynon · Jeff Brothers · Alice Calhoun · Afton Cooper · David Coppe · Brad Dowler · Shane Estep · Michael W Feldser · Christian Ford · Robert Christian Ford · Peter Gartrell · John Goodwin · James Grube · Ryan Harris & Susan Barr · Natalia Hodge · Catherine Hughes · Sara Hurst · Keith Kelley · Katie Kimbrough · Atheil Lashley · Ina B Leonard · Robert & Nell Lyford · Ashley Matejka · Lisa Darnay Meadows · Randall Morley · Sallie Oliphant · Kevin Patterson · Jimmie G Purvis · Kim F Quillen · David Radulovich · Dudley C Reynolds · Kirk Reynolds · Bernie Rosman · Ashley Ross · Michael Sapeta · Daniel & Jennifer Smith · Ray Smith · Aaron & Anna Strong · Millie Ward OA BENEFACTORS & TRAILBLAZERS Contributions of $100 or more in the past year Virginia Simpson Aisner · Amber Albritton-Reiman · Patrick Anderson · Ryan-Ashley Anderson · Angela Arcese · Susan Arnold · John Aselage · Chris Barton · Jeanne Beatty · Richard Blanton · Steven Blevins · Kat Bogacz · Linda Booker · Eliza Borné & John Williams · Susan & Robin Borné · Treasia Bouton · Laura L Bradley · Carol Brantley · James Brinn · Chad D Browning · John Bunten Jr. · Rick Bybee · Anthony Cantor · John Carmody · Ted Cashion · Lauren Cerand · Robert TJ Childers · Scott Clackum · Edward T Claghorn · Joan & Bruce Coffey · G. Dale Cousins · Andrew Crispin · Gail B Crump · Kimberly Daggerhart · Fred & Sarah Beth Davis · John Dennis · Donna Thompson Douglas · Jon Edwards · Julie Enszer · Rebecca Evans · Robert Fallon · Ms. Richard Faszholz · Donna Ferron · Deborah Fisher · Ben Fountain · Linda Fowler · Slaton Fry · Tom Funderburk · Katherine Z Gailliot · John Paul Gairhan · Ron Gephart · Philip W Gibson · Rabbi Jeff Glickman · Melanie E Gray & David Rubin · Laura Green · Sarah Greenberg · Glenn Greisman · Michael Gresham · Ann Marshall Grisgby · Leonard Grinstead · Paul V Guagliardo · Helen And Alexander Haris · David Harrison · Robert Hart · Henry G Hartzog IV · Edward Hebson · James Henderson · Thomas G Hendricks · Barbara Herring · Marnie Heyn · Samuel Hinojosa · Mindy Hodges · Jack M Holland · Adele Holmes · Janet Holmes Uchendu · Amy Holt · Chad Hood · Joe Horton · Mark Hughey · Andrew Humphries · Laura Ingram · Samuel Jackson · Glenn Jacobs · Lee & Paula Johnson · Matt Jones · Michael Jones · Tim Jones · Steve Jones · Danny Kahn · Jane R Kell · Robert K Kettenmann · Kathleen King · Mal King · David King · Andy Knott · Mack Land · Katherine Landrum · Holly Lange · Jean Larson · Tracy Lea · Jessica Lee · Jerilyn Lewis · Howard Ligon · Jason Linetzky · Buz Livingston · Elizabeth Lynch · Michael Maloney · Stephen Manella · Steve Marston · Bryan Mathis · Patrick McCoy · Richard McGuire · Dwight McNeill · Frances M McSwain · John & Meg Menke · Chalmers Mikell · Gammy Miller · Rosanna Miller · Abigail Moore · Erik Moore · William M. Muller · Dean Neff · Mike Nichols · Christine Ohlman · Rod O'Mara · Rebecca O'Neil · Larry Ortega · Ann & Rick Owen · Elizabeth Owen · Cliff Oxford · Martha & David Pacini · Gene Paquette · Robert Parker · Joel Patterson · Dee Dee Perkins · Wade Perry · Patrick Payton · Rhonda Gail Phillips · James Powers · Jeanie Ramey · Georgia Raynor · George Redlinger · Robert Rettig · Alex R Rodriguez · George Rothert · Alan Rothschild · Jileen Russell · Robert Rychliki · Jeanette Saddler Taylor · Kelly Samek · Archie Schaffer III · Jeffrey P Schlatter · Chad Schrock · Howard Scott · Quin Segall · Milton W. Seiler, Jr. · Bill Semich · Adam Short · Ralph Simpson · Kate Small · Irvin Smith · Eric Steele · Christopher Strawn · Jane Tatum · Joe Thomas · Garland Thorn · Harrison Tome · Roger Trapp · Ben Van Dusen · David L VanLiew · Tim Walker · Christopher Walters · Doug Warren · James A Washburn · Ralph Webb · Randy Wilbourn · Reba Williams · Cary Wilson · George Wise · Vickie Wyatt · Randy Yauss · Randy Zielinski

WINDGATE CENTER ▶ Nearly 100,000 square feet of classroom, studio, rehearsal, design and performance spaces ▶ State-of-the-art technology ▶ 450-seat concert hall ▶ 175-seat black box theater ▶ Arts common and gallery CULTUREEXPRESSION.OFFORFINE&PERFORMINGARTS,OPENINGSPRING’23BUILDINGA CAPITAL CAMPAIGN

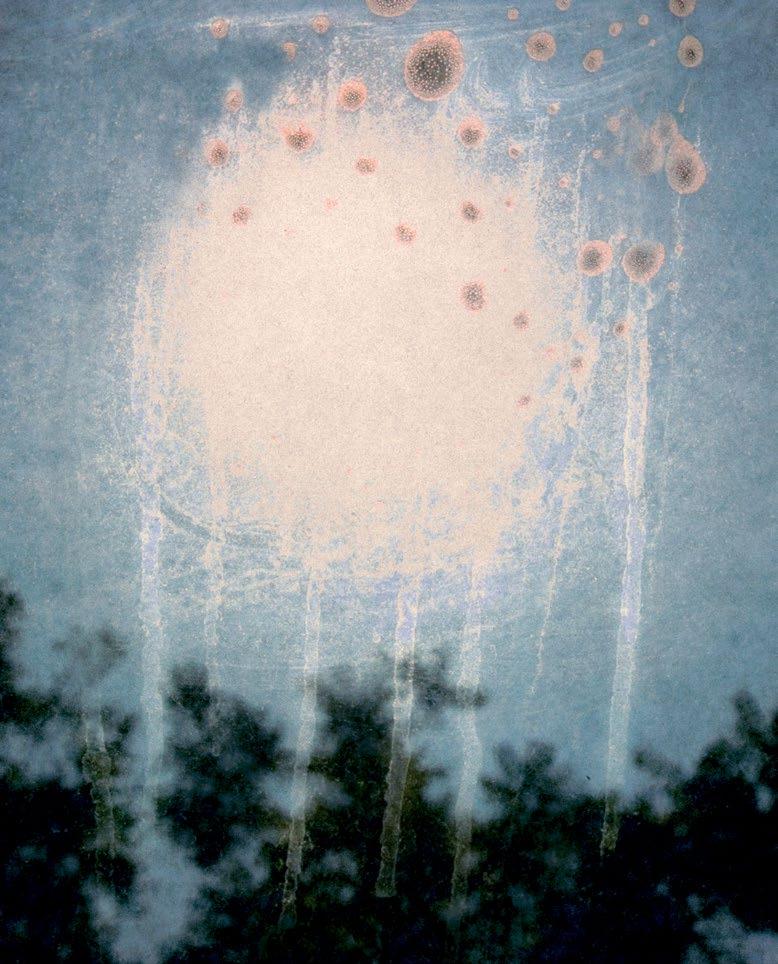

FALL 2022 POINTS SOUTHOXFORD AMERICAN 13 Photograph by Peter Fisher from his monograph At Least I Heard Your Bluebird Sing, published last year by Pomegranate Press. Courtesy the artist

Santa hadn’t asked when he was standing on that corner. Nor had the United Methodists who were handing out flyers for their car wash fundraiser. But the clown spoke as if he knew our family, waiting there at the red light. Momma was in the front passenger seat, and my sisters and I were in back—which, in a 1964-1/2 Ford Mustang, meant we were as close as three people could get, irrespective of their DNA. I was the youngest and heavier than the others—“husky” was the word I so dreaded—and sat on the end, directly behind Daddy, who was slim. We girls had quarreled over which of us would have to ride the hard middle of the Mustang’s bench seat all the way from New Orleans, up the Plank Road, and onto the loosely graveled lane where our grandpar ents lived, almost thirty miles north of Ba ton Rouge. We’d argued the way children do when they don’t want their parents to know—rolling our eyes and sucking our teeth, furiously whispering and careful not to let our arms or thighs touch in that tuna can of a car. Now, we focused on the adults. Their thighs weren’t touching at all. The clown wanted an answer. Our mother, a tall, fair-skinned beauty Sidney Poitier had once picked out of a crowd, blinked a few times. But she didn’t say anything. Daddy seemed startled. He looked left, di rectly at the clown’s face, and then turned his head slowly right and looked at our mother. He waited a beat. Then he turned back to the clown and, from the sliver of an angle I could see in his side mirror, he smiled the smile of a man who’s been caught in a tight spot. The clown handed him his card. I saw it all—the clown’s eyes, Momma’s blinks, Daddy. From behind, it looked as if he had made a quiet effort to shake his head no. Daddy was clever that way. Quick. He took the clown’s card and tapped it into his shirt pocket, behind the pencils that already were dulling the broadcloth. Momma never could brighten the fabric, no matter what she tried.

“What time is it?” our middle sis ter asked from the middle seat. “You need to be somewhere?” Daddy answered, glancing at her in the rearview mirror. Nobody said anything after that. Even our silent, sisterly grudge fell away. We settled into the backseat, thighs touching now, in quiet agree ment that something had spoiled. Momma turned her knees toward the passenger door. Daddy glanced at her again, then caught sight of the green light and accelerated, driving us straight through the intersection. I sucked my thumb and waited. As we merged onto Airline High way, it occurred to me that Mustangs must look strange when they’re stuffed with passengers inside. Not so the Volkswagen Beetle, which was already peculiar because the engine was in the back and the trunk was up front. It was funny to see how many people could squeeze in. A crowd of arms and legs dangling from the windows and under the hood looked a merry mess, as if the car was gobbling up pedestrians in a madcap, carnivorous frenzy. Our older brother had a red Beetle, and once a month he’d take our grand mother on her errands up and down the Plank Road, from the Clinton Bank and Trust south to Delmont Village, where the D. H. Holmes department store was. Everybody—even Big Mama—laughed when she’d back her six-foot frame into that car, wearing a tall wig, high heels, and a full-frame, hook-and-eye girdle. Sometimes, when I rode with them, she’d buy peppermint sticks at the Woolworth’s for the drive home. We’d have a ball, sucking and chatting about nothing and waving back at the people in their cars. But when the drivers on Airline Highway looked over at our bright white Mustang, counting five gloomy faces inside, they sped up or slowed down just enough to stay out of sight. Airline Highway is part of the Highway 61 that Bob Dylan writes about, the one that Governor Huey Long had wanted paved in the 1930s to slip down faster from the state capitol to the French Quarter. Highway 61

14 FALL 2022

Night Car (mountain/road triptych), 2021. Oil stick and acrylic on canvas by Eliot Greenwald, 48 x 75 x 2 inches. Courtesy the artist

W hen I was a child, a clown pushed his face into the driv er side window of our family car and asked my father, “Are you happy?”

BY GWEN THOMPKINS

The Mustang

Revisited likely meant nothing to our father, though he didn’t mind watching Dylan sing on television. Daddy cared for music more than he ever could describe and sometimes talked about seeing Count Basie and His Orchestra in Denver, where he’d lived as a bachelor after leaving the navy. He also saw Louis Jordan there, and he smiled one of his rare smiles when he spoke of Dinah Washington. Frowningly, he’d mention Billie Holiday drunk at a diner one weekend night. Even now, when I picture Ms. Holiday, she’s listing over a cup of coffee in a restaurant booth, someone slapping her awake. Something was wrong with the tire. We’d passed the Airline Drive-In and turned onto the Plank Road by then and the long succes sion of orange-and-blue, blue-white-and-red, and red-black-and-white filling stations had ceased, as had Highway 61’s many railroad crossings and traffic stops. The Plank Road was a smooth, two-lane state highway, giving rise to green pastures and brown-and-white cows. Small towns like Baker and Zacha ry had signs mentioning them along our way, though no signs marked Cheneyville or Schulingkamp or the other little places where our cousins were living. But they were there. We felt a wobble on the other end of the bench seat.

OXFORDAMERICAN.ORG 15

“And Gwinnie, you just as fat. You girls look some pretty in your clothes. Yes, indeed. Y’all want something? They got cold drinks in the Daddyicebox.”andBig Papa walked over to Big Papa’s acre of turnips and collard greens on the sunny side of the house and discussed them in far more detail than one might think possible.“Glory Dean, how you feelin’?” Big Mama asked“I’mMomma.fine,”Momma said, searching the house for her sisters. “Where are Lo’ and Dorothy?”“Theycomin’,” Big Mama said. “Is Ike stayin’?”“No,he’s going back to New Orleans,” MommaDaddysaid.walked to the gate. “Well, I’m going,” he told us. “You ain’t gon’ eat nothin’?” Big Mama called out from the porch. “No, I’d better get on the road,” Daddy said, still “Something’ssmiling.wrong with the tire,” Big Papa explained. “Oh, you gotta get that fixed,” Big Mama said. “Well, drive safe!” “Bye, Daddy!” Geselle said. “Bye, Daddy,” Gayle said. Momma and I just waved. Daddy turned the car around easily on the gravel. “Y’all be good,” he said out the window, slowly accelerating. I can’t remember if it was the last time we were all there together. Nor do I remember how long it was before Daddy left home for good, giving Momma the car, expanding his business, and taking care of us all remotely. But as the Mustang passed us, I noticed how wonderful it looked with only him inside. Sunlight made the white pop even brighter against the green brush pressing in from the forest, while the wheels kicked up a spray of caramel-colored dust. We could see straight through the back glass and over his shoulder to the open road. We could hear the wheels speeding over the rocks and the ebbing hum of the engine. That’s how Mustangs are when they’re running as they should. They move fast and free. We could see straight through the back glass and over his shoulder to the open road.

16 FALL 2022

“Why don’t you move to the seat on this end?” he said gently to our middle sister, the skinniest one, built like a dragonfly. He opened the door and we all squeezed out from behind Momma’s seat and then squeezed back in again. Daddy looked hard at Momma then and pressed his lips together until we couldn’t see them anymore. Our eldest sister, already five-foot-ten in the sixth grade, moved to my end, which landed me in the hard middle, the foam as stiff as a saddle. Momma folded her arms in her lap, saying nothing, and we took our cue from her. She was pretty enough not to be handy, or animated in public, and believed that men existed—often to the torment of women—because they were meant to fix things. And yet, more than likely, she was angry. It had taken her days behind closed doors to convince Daddy to drive us to her family in the country and he had announced our departure only that morning. He’d leave us there a week and then come back, because he almost never wanted to stay. In addition to his regular job as a construction company supervi sor, he’d take masonry work on the side, or refurbish old houses he’d buy to rent. That’s what weekends were for, not driv ing up to Clinton and back, no matter how smooth Huey Long’s asphalt was. Daddy changed the tire with us inside. He, too, was built like a dragonfly, but he was as strong as any man we’d seen, with hands like leathery oven mitts. Growing up on a farm in northern Florida, he had learned his punishing work ethic there—all seven days of the week, except Christmas, or why ever try? Even his mother had died in labor, bringing her eleventh child into the world. After that, when Daddy milked the cows in the morning, they’d mistake him for a calf. Or maybe they understood exactly who he was—a little boy without a mother. Either way, he remembered, “They’d lick me right on the “Moooooooo!”head.”

“Hey, Ike,” Big Mama called to Daddy as we climbed out of the car. She was standing on the porch in a house dress, with her fists high on her hips. Big Papa’s bloodhound stood up and walked slowly to the fence gate, while the Labrador puppy went wild, barking and twisting as if ticker tape was in the air.

I said, after we’d merged back onto the road, passing a blur of cattle.

“Y’all gettin’ so tall,” she said. “Gayle, how tall are “Five-ten,”you?” Gayle said, as a new country lilt in her voice lifted her smile. “You so skinny, Gazelle,” Big Mama told Geselle, instantly changing the soft “G” in her name, the way everybody did over here.

Daddy pulled to the shoulder and leapt out. As his door opened, the car cabin suddenly came to life with the whooshing air of passing traffic and the loud skirls of transmissions changing gears. A few shoves on the passen ger side rear tire confirmed what he’d been afraid of—a slow leak.

“Daddy, what kinds of cows are those?” “Not sure,” he said, nose up, his eyes dart ing back and forth from the road to the grassy fields behind barbed wire and creosote posts. “Maybe Jersey. Or…Brahman.” Daddy swiv eled his head again and leaned back toward the pastures behind Momma’s head, looking genuinely interested. “Are they cows or steers?” our middle sis ter on the end asked. “They’re cows,” I said. “They have…squeez ers.”Momma and the girls laughed. Then a mitt snaked from behind the driv er’s seat and hit me on the leg. “Don’t say that,” Daddy said. “That’s nasty.” I had no idea what he was talking about. But everybody stopped laughing and I put my thumb back into my mouth. We passed some Guernseys. Then, Daddy took his foot off the gas and braked slowly, turning into a small forest on a dirt road that I never saw coming.

“How are you?” Daddy said, smiling. “We fine,” Big Papa said, shaking Daddy’s hand. Everybody was tall on Momma’s side of the family and Daddy looked like the odd man out. He petted the Labrador. Momma’s thoughts mirrored the puppy’s. “Hey now!” she said to everybody, laughing. She grabbed her pocketbook, slammed the passenger door, and walked toward the house without looking back. “Get the bags,” she said to us as she swung through the gate and climbed the porch steps. “Y’all get the bags.” We got the bags. Then we held them as Big Mama smashed us, one by one, to her bosom.

CARLOS.EMORY.EDU Intaglio Gem Depicting Isis-Aphrodite Roman. Late 2nd–mid 3rd Century CE Crystalline quartz, var. amethyst. Gift of the Estate of Michael J. Shubin. 2008.031 108. Photo by Bruce M. White, This2021exhibition has been made possible through generous support from the Michael J. Shubin Endowment, the Evergreen Foundation, the Samuel H. Kress Foundation, Krista Lankswert, and New Roman Creative. EXPLORE EXHIBITIONTHE

I should’ve found a new dentist years ago. The fact that Dr. Patel has stopped giving me his signature scratch-and-sniff stick ers and started calling me “the Elder” might have been enough to force others out by now, but not me. We’ve been through too much together: dozens of cleanings, six fillings, two extractions after an unfortunate encounter with the bottom of a swimming pool, and one nitrous-fueled hallucination wherein the toucans on the ceiling flew down to greet me. And history aside, where else am I going to find a free Pac-Man machine in the waiting room? So much is my penchant for Pac-Man and my loathing for change that, at thirty, I am still seeing my pediatric dentist. But Dr. Patel didn’t meet me as a full-grown adult earning

Cavities and Debris

A STORY BY MELODY MOEZZI

18 FALL 2022

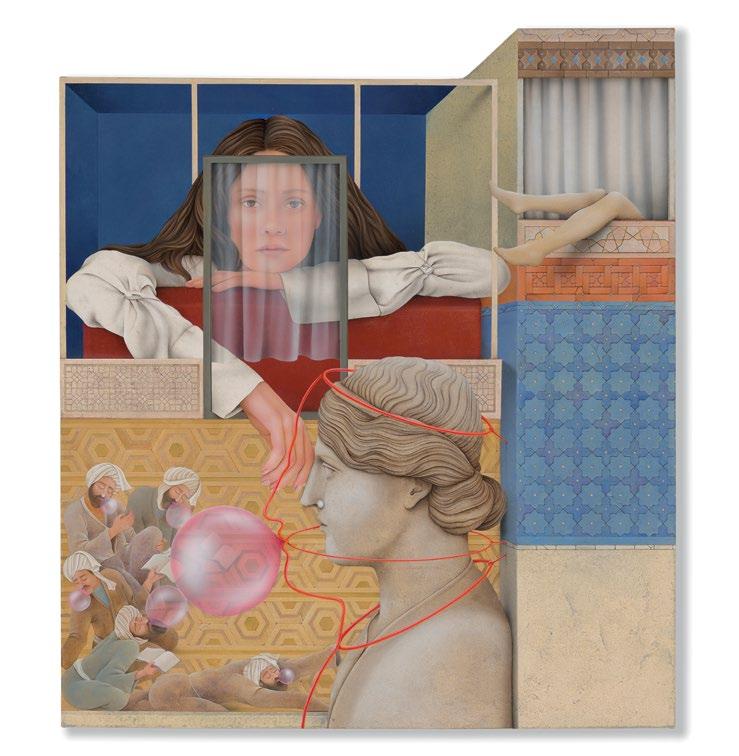

The Touch, 2019. Acrylic on canvas stretched wood panel, by Arghavan Khosravi. Courtesy the artist and Rachel Uffner Gallery, New York

DARBY DENTAL SUPPLY . Grow the fuck up QUALITY CERTIFIED Leave Dr. Patel PATIENT TOWELS . Finish my PhD al ready ECONOMY Move out of Macon BULK. Procure new employment that doesn’t involve torturing rodents

“Why’d“In“What’s“No,Spanish.”it’sArabic.”itmean?”thenameofGod.”yousayit?”“It’sjustaprayerIsay before starting something—like before I eat or leave the house or drive or take a test. Stuff like that.”

“She's real tired,” Katie explains. “Stephen says I make her tired, but that’s not really true. She’s sick. Not like she’s-gonna-die sick, but like when you’re always tired and fall asleep when you don’t want to. That kind of Isick.”tryto make eye contact with the two conscious mothers in the room, hoping they will sense my total lack of maternal instincts, pity me, and rush to scoop Katie

a doctorate in biochemistry. He met me as a miniature refugee fleeing the Iran-Iraq War and landing in the buckle of the Bible Belt. Only a week after we left Tehran, the aforementioned swimming pool face-plant suddenly made dental care a high priority for my family, and Dr. Patel was the only dentist in town who worked weekends. His was the first brown face I encountered in any position of authority in America. He bore a striking resemblance to my favorite uncle, who had just died in the war, and he didn’t care that we barely spoke English. So of course, it’s possible I grew a little too attached. It’s also possible I’m digging way too deep for ex cuses. Whatever the case, I feel embarrassed to be here, but I also feel reassured by the faded jungle-themed wallpaper peeling at the seams. Shouldn’t I be allowed to stay at least as long as the wallcoverings? Such is the mental flotsam whirling about my head as I level up at Dr. Patel’s ancient arcade table. Just then, from the television bolted to the ceiling, a giddy meteorologist interrupts Judge Judy to report tornado warnings. My eyes drift up to it for a second at most, but by the time they dart back down to the Pac-Man machine, it’s too late. Death is inescapable. Trapped in a corner between two ghosts, orange to my left and red below, I collide with the latter and disintegrate on contact. Sirens and Dr. Patel’s voice muffle the sound of my virtual demise as reality sets in: Several tornadoes have already touched down around us. We aren’t safe here.

“Bismi-what?”Startled,Iopen my eyes to find a little girl standing before me. Where seconds before there was nothing, just empty space between my body and the patient towels, now there is this pintsized human staring at me.

2 PLY PAPER. Quit dating assholes. 1 PLY POLY. Start painting again PLASTIC BACKED. Stop skipping breakfast. ABSOR BENT Hydrate STRONG Exercise SOFT Cease freeloading on my parents’ mobile plans 18" X 13" Learn to cook (45.7 CM X 33.0 CM). Do my own damn taxes 500/BOX Find a general dentist Stunned by this strange string of Dar by-Dental-Supply-inspired directives, I re solve to follow them all. To seal the deal, I close my eyes, take in a deep breath of bubble-gum-bleach, and exhale slowly, whis pering a prayer: bismillah.

“Bismi-what?” she repeats. “Bismi-llah,” I reply.

“Like ready, set, go?”

Her head is draped in a mop of tight red curls framing a face full of freckles, and her enormous green eyes bulge defiantly out of her skull. She wears a faded blue cotton dress with multicolored buttons in the shape of various farm animals running down the front. Her stomach protrudes just enough to give prominence to the purple cow. She is missing one of her shoes but doesn’t seem to mind. Stepping forward, she comes in close and looks me square in the eyes, the way only children have the nerve to do.

“Sure. Why not?” I reply. Desperate to exit this conversation, I lift my head above the boxes and scan the room for this kid’s mom.

“I don’t know that word.”

“Follow me,” says the sweet old man who should be a waning memory, a charming relic of my childhood graciously bequeathed to future generations. This whole scenario might make sense as a bizarre dream, with me playing the part of a living anachronism. But as an actuality, it’s absurd. Here is Dr. Patel, a fixture from my past dragged into the present courtesy of my epic indolence and misoneism. And here am I, a grown-ass woman following him, his staff, three children, and their moms into a basement I never knew existed. Small, oblong, and bare—with concrete floors, fluorescent overhead lights, white walls lined with brown cardboard boxes, and a solitary drain at the center—the basement reeks of bleach and bubble gum. Following Dr. Patel’s instructions, we push aside packages to make room for our bodies, sitting on the floor against opposing walls. I head to a far corner, maximizing the distance between me and the others, moving a carton labeled PATIENT TOWELS, and quickly taking its place against the wall. Behind this box and sandwiched between two others (SALIVA EJECTORS and ORAL EVACUATOR TIPS), I long to disappear.Eventhe most mundane small talk will likely force me to explain why I’m here. So I keep quiet and out of sight, sinking into my corner sanctuary, hugging my knees close and tight. Together, side by side, my patellae create a cradle for my chin. A fit so seamless it has me imagining all these bones fused at some point in fetal development, like conti nents once joined, yet destined to drift apart, a human Pangaea divorcing itself. Soon my chest fills with panic. Hoping to extinguish it, I try a trick a firefighter once taught me: shifting my focus away from the racing thoughts in my head (What if Brazil crashes back into West Africa? What if this tornado flattens all of central Georgia? What if we never get out of here?) and toward an object in my immediate vicinity (the patient towels). Fixating on the box, I read every thing on it. The words are as random as they are irrelevant to me, yet each one delivers more comfort than the last. And with that comfort comes clarity, a flood of revelations flanked by nonsense, the latter somehow bringing the former into focus:

“You don’t need to. It’s not English.” “Is it Spanish? I watch Dora, so I know some

“I’m Ziba,” I say as I shake her hand. “Where’s your mom?” “She’s over there,” Katie replies, pointing to the opposite corner of the room. I follow the direction of her pudgy finger with my eyes to a thin blond woman holding a stuffed Big Bird on her lap. She looks wan and weathered, her head cocked so far to the left that it seems on the brink of snapping. She is beyond sleep, mouth agape, harsh fluorescent light reflecting off a string of drool inching toward Big Bird’s beak.

“I’m Katie. What’s your name?” she asks, holding her hand out to shake mine like this is old hat to her, like she sneaks up on strang ers in basements every day with the express intent of staring them down and shaking their hands, like she is living in some Peanuts special where parents are irrelevant.

OXFORDAMERICAN.ORG 19

20 FALL 2022

So I begin reading, assuming she will quickly realize how tiresome and confusing it all is and make me stop. But she doesn’t. Until—nearly a third of the way through the article—I read the word Fallujah. She grabs my arm and looks up at me with her big emerald eyes. “Have you been there?”

up. No such luck. I’d have to move the box of saliva ejectors for the other moms to see us. But I’m so repulsed by that label alone— unable to imagine even speaking those two words in succession without gagging—that I can’t bring myself to handle the box. What if, at the exact moment I pick it up, a torna do crushes us all? My obituary could read “Graduate Student Crushed Beneath Box of Saliva Ejectors.” I can’t risk it. “Have you ever been sick?” Katie asks. I want to say I’m sick right now, but I say “yes”“Sure,”“Areinstead.youbetter?”Ireply.“It was never anything se rious: just colds and flus really—” “Can I see that?” she interrupts, bored by my trivial viruses. She is leaning out from behind the patient towels and pointing at a man across from us. “See what?” “The magazine that man is reading. Please ask him for it, Ziba!” “You ask him.” “You’re bigger. He’ll listen to you.” I lean over to get a better look. He isn’t part of Dr. Patel’s staff and doesn’t have a kid in tow, so I’m just as confused as someone else would be looking at me prior to Katie’s arrival. But he is at least fifty, and by Dr. Patel’s own chronic telling, I am his oldest patient. Just then, the man straightens his back against the wall, revealing a UPS logo above his left shirt pocket, and the mystery is solved. He looks affable enough and I’ve never had a bad experience with a UPS courier, so I get up and give in to Katie’s demands. She follows closely behind. “Excuse me, sir,” I say softly so as not to wake anyone up.

“Would you mind lending your magazine to my friend Katie here?” I ask. “Can’t you see that I’m reading it?” he snaps.“I’m sorry, Katie. The grown man won’t let you see his magazine,” I tell her, just loud enough for him to hear as we head back to our corner and sit down. He then gets up and walks toward us, the magazine (which I can now discern as Time) in hand.

Defeated, Gopher drops the magazine onto the floor next to us, rolls his eyes, and heads back to his side of the room. I’m baffled by how quickly she got him to cave. Growing up in Iran and even here, I’d never have spoken to an adult like that. To this day—bound by the endless intersections of Southern and Persian hospitality—I wouldn't dare. But Katie is brave and shameless. She proudly hands me the Time “I didn’t want this,” I say. “But I can’t read so good yet. You have to read for me. Pleeease, Ziba.”

The other two patients—tweens with the trials of impending adolescence airing brutal previews on their faces, the girl’s caked in glitter and the boy’s coated with cystic acne— are lying on their mothers’ laps. Both moms hold up their own heads with one hand and rest the other on the heads of their respective offspring. The secretary and hygienist sit serenely against the wall behind Dr. Patel, presumably asleep as well, muted shadows.

Katie’s mom has set the tone for this after noon without trying. Apart from Katie and me, the UPS guy, and Dr. Patel (who appears to be doing paperwork), everyone else is either fast asleep or well on their way. Most knees have been released, and despite the sirens, people seem oddly calm.

“But the name: Fa-lu-ja. It sounds so cool. Like a circus or a cartoon or something. Even if bad stuff happens there, it can’t be all bad.” She keeps repeating the only prayer she knows I andtoo—simple,knowselfless,sacred.

“I’m older than you, and as a person who has been on this planet for quite—”

“Could I pleeease see your magazine, sir? I’ll give it back,” she interrupts. He looks at me as if I am to blame for this. I feel a little sorry for him, crouched down on the con crete like an oversized gopher, now looking up at me with his beady blue eyes, but I’m not about to take the blame. I have no interest in his “Comeperiodical.on,”Katie continues. “Don’t be such a meanie. Didn’t they teach you that you’re supposed to share?”

“How old are you?” he asks Katie sternly, squatting down so they are face to face. I immediately stand up. It won’t be hard to throw him off his center of gravity if he tries to touch her, and I am ready to do it. Despite my general aversion to children, this one is growing on me. “Six and a half. How old are you?” she responds, unperturbed, reminding me of myself at that age. I’d already survived a revolution and was living in a warzone, so it took a lot to scare me back then. I was raised to never let anyone hurt or intimidate me—at least not without a fight. Political turmoil aside, Katie seems to be the product of a similar upbringing.

The magazine is several months old, but the world hasn’t changed much. I probably should decline Katie’s request based on the cover alone: a shirtless, hooded, emaciated prisoner, arms tied behind his back—presum ably one of the Abu Ghraib detainees—with the words “Special Report” and “IRAQ: HOW DID IT COME TO THIS?” printed above his head. But having no children of my own and zero desire to create any, I suck at discerning what is and isn’t appropriate for them. Both of my sisters have kids, and over the years, I have repeatedly gotten in trouble for exposing them to too much too soon, from Gray’s Anatomy to Public Enemy. Point being, I should know better by now, but I don’t. “You really want me to read you Time? It’s not like Dr. Seuss. It’s boring and depressing.”“Doyouhave Dr. Seuss?” Katie pleads. “No,” I concede. “Then Time! Please read it. Pretty please with a cherry and sprinkles on top?”“Fine. What do you want me to read?” Katie slides in close beside me and takes the magazine from my hands, flipping to a story with a photo of George W. Bush grinning like a maniac while shaking some general’s hand. On the opposite page is a bloodied soldier lying on the ground next to a Shetank.immediately points to it, nudging my elbow with hers: “This! Tell me what it says.”

“Um, no, Katie. It’s super dangerous. You don’t wanna go there.”

“I know,” she says, staring at her shoeless foot. “My brother Stephen died there.” Is she serious? I think to myself. Then: Of course she is serious. She’s six. What the hell were you thinking reading this to her? All I wanted was a filling, and now here I am stuck in a basement under a tornado, traumatizing a total stranger, a child, for no good reason. Unlike a filling—painful for a few minutes, but ultimately advancing us to victory in the battle against tooth decay— there is zero upside here. It’s far too late to get out of this mess now, and even if it weren’t, there is nowhere to go. Are you even supposed to tell kids that young when people die? And if so, are you supposed to tell them where and how? It just seems like Katie knows way too much already, but then again, I guess I did too at her age. I always found it strange how the same people who would tell us kids not to fight with one another would then go off to war to kill each other the second they were grown. I close the magazine and lay it on the floor facedown, re membering how tightly Uncle Hamid hugged me the last time I saw him, like his body knew he’d never return from the war even as his words tried to convince me otherwise.

OXFORDAMERICAN.ORG 21

“All the best art is a mess that gets the artist into trouble,” I say. “But I have a mom too, so I get it. Why don’t you wait here while I go pick up the pieces?” But before Katie can answer, the lights go out, and my mind regresses twenty years in an instant. At ten, in Tehran, tornadoes were nowhere on my radar. Back then, when the lights went out, it wasn’t wind we worried about. It was war. So I do what my parents trained me to do in the event of an aerial bombing: I find a basement—convenient given I’m already in one, albeit twenty years later and across the Atlantic. But trauma leaves no room for daft delineations around time and space. Here, reflex reigns. Just as my pupils take the darkness as a cue to dilate, my psyche takes it as a cue to negotiate. Thus, with neither thought nor effort, I proceed to step two of my childhood civilian military training: desperate devotions. Filled with a fervor only explosives can evoke, I pray with the passion of a pilgrim crawling to Karbala on Ashura. These aren’t the prayers I used to speed through five times a day like an annoyed auctioneer selling my soul for a few more minutes with a jump rope or a pogo stick. These are the prayers I extend and enun ciate like a dread-filled delinquent knowing this might be her last chance to repent for every prayer she has ever skipped or sped through. My loud, elongated Qur’anic verses fill the basement, waking everyone up but me. As our eyes slowly adjust to the dark, Dr. Patel and several others, including Katie’s mom, take turns asking me what’s wrong, attempting to comfort me, to coax me back into the present. But none of it registers, so I keepUnsurprisinglypraying. for Macon, there are no other Muslims in this basement. But there is Katie, and as of twenty minutes ago, she knows bismillah. As I stand, bend, kneel, and prostrate, she does the same, holding my hand in hers, our limbs connected like two electrons in a covalent bond. All the while, she keeps repeating the only prayer she knows I know too—simple, selfless, and sacred—over and over again. A tiny, acciden tal shaykha clearing out decades-old psychic debris, she fills the incandescent emptiness with a single word, spoken in succession and solidarity. Bismillah. Minutes later, when the lights return and the sirens cease, Katie’s zikr persists, carrying me back to the twenty-first century intact. Ready. Set. Go.

“No way, lady! That’s my magazine. It’s not from the waiting room. She said she would give it back. Now look what she’s done to it, what you’re letting her do to it.”

Standing behind Katie, Gopher can’t see her face. I’d like to think that if he could, he would shut up right quick and crawl back into the sad hole whence he came, but I doubt it. He saw me wipe her tears, so he must know something is wrong. Having obliterated the magazine in her lap, Katie gathers the pieces in her skirt, turns around, and empties the mess onto Gopher’s faded brown work boots. His face turns so red so quickly that it looks as if his blood might actually be boiling. Still, he mercifully says nothing as he wrings his hands and returns to his side of the room. But this time, through no act of his own, Gopher doesn’t walk back as just another trifling human. Rather, he does so—thanks to Katie—as a monument in motion, scraps of copy scattering across the concrete with his every step, dispersing devastation in all directions, disaster confetti. Were we in Man hattan, Katie could revive and direct this same scene nightly, call it performance art, and charge admission. But being in Macon, I know there will be no repeat performances, so I savor this one. “I feel better,” Katie says. “I didn’t want to be mean, but it felt good to tear something up. You “Sure.know?”Andlook at what you made,” I say as she sits back down beside me and we behold Gopher’s retreat. She has stopped crying and is resting her head on my arm. “You see those snippets of paper flying all over the place? It’s so pretty, like moving art.” “Art? It’s a mess though. When my mom wakes up, I’ll be in trouble. She’ll make me clean it up for sure.”

“I promise I’ll buy you another copy. Just please, give us a minute,” I tell Gopher as I wipe Katie’s cheeks with my thumbs, holding her head in my hands.

“I’m so sorry that happened to your broth er, Katie.” My immaturity and carelessness have no doubt further wounded this innocent girl, and I hate myself for it. But she doesn’t look sad or distraught. She just keeps staring at her unshod foot: her sock, that pale pink that sinks in when you accidentally throw in a red with whites. “Why? It’s not your fault,” Katie says calm ly, sliding a tiny turquoise crucifix back and forth along the silver chain around her neck. “Do you have a brother?” “No, just a couple sisters.” “I only had Stephen; now it’s just me and Mom. She’s okay, but since he died, she doesn’t play with me as much—and she sold our trampoline. Do you have a trampoline?” “No. I’ve actually never been on one.” “Oh, Ziba, they’re so much fun. You’ve gotta try it,” she gushes.

Katie has somehow managed to jump from her dead brother to trampolines in mere seconds. I’m grateful though, as I’ve now exceeded my max quota for blood and gore for the day; trampolines I can tolerate. But Katie is already bored with them by the time I come to this conclusion.

“Of course. I’m sure it’s nice normally, but right now it’s a huge mess. There’s a war going on. It’s not safe.”

Grabbing the magazine in front of us, she stands up, turns around, and then sits back down to face me, lotus style, her back against the patient towels. Without a word, she calm ly and deliberately proceeds to tear the Time to shreds. Gopher soon notices from across the room and jets back to us. “Tell her to stop!” he whisper-yells at me. Tears are now streaming down Katie’s face, but she is silent and still. Not a single sniffle or even a chin quiver. Just a flood of tears.

LostontheTrail, 2013. Photograph on canvas and wood by Bear Allison. Courtesy the artist

StumblingStone

At the time of removal, the term for Andrew Jackson’s policy of wiping the In digenous presence from lands east of the Mississippi, there were between fourteen and fifteen thousand Cherokees living in the Southeast. Four thousand households, roughly, and Saunt has an entry in his sys tem for each one. Personal possessions like the ones owned by Chewey are only a small part of the tabulation. Working off of twohundred-year-old surveys and assessments,

BY BENJAMIN HEDIN T hey are filed away in boxes in the Na tional Archives, books and ledgers full of blotchy, ornate handwriting. A sheet inside of one, dated June 19, 1838, lists a fiddle and shot pouch horn, four chairs, and some bedding. Anoth er gives the price for a spinning wheel and plough. Turning forward, you find mention of bee stands, cotton cards, pails, and chisels. And while they seem nothing more than a catalog of the most ordinary possessions, the pages delineate a tragedy of immeasurable scope, for they are the records of what a people lost when they were evicted from their ancestral lands, forced to give up everything they“It’sowned.really quite astonishing,” said Claudio Saunt, a professor of history at the University of Georgia who found these lists one day while doing some research. “The govern ment produces thousands of documents in the process of deporting Cherokees. It’s not much of an exaggeration to say we know more about the Cherokees than any other people in the world.” The cover of the book Saunt was showing me had a label: returns of property left by the indians and sold by agents. Most of the entries in it were from the summer or fall of 1838, in the days after the U.S. Army began sending the Cherokee people who were living in Georgia, North Carolina, Ten nessee, and Alabama to the stockades that were the point of origin for the Trail of Tears. The pages record not only the property that was owned but also the name of the white person who acquired it. From the page dated June 19, 1838, for instance, we learn that a Mr. Sloan purchased the fiddle that only days before belonged to a Cherokee man named Chewey. His loom went to Colonel Neely, who also bought, for around a dollar, Chewey’s table, bed, and piss pot.

Saunt, the author of Unworthy Republic, an award-winning study of the expulsion of the Cherokee and other Southeastern tribes, has been collecting and digitizing records such as these for more than a year. In 2023 he expects to publish an interactive, virtual census of the Cherokee Nation as it existed two centuries ago. Even in the offline, ges tational stage in which I was able to view it, the archive is startling and remarkably de tailed, and raises important questions about the kind of action historical memory can or should inspire.

22 FALL 2022

receipts, trial records, and bills of credit, Saunt has established how much land be longed to each household, the number of cabins on the property, and their square footage; he has mapped each location as well, creating what is in effect an atlas of dispossession. Looking at the screen, one sees thousands of pins, each representing a Cherokee person or family, arrayed across a territory stretching from the Great Smoky Mountains of Tennessee and North Carolina in the north to the Atlanta suburbs in the south, and west to Muscle Shoals.

OXFORDAMERICAN.ORG 23

“It’s all about a presence on the landscape that was erased and then forgotten,” Saunt said of the mapping component of his proj ect. “For me it’s a challenge to try and restore thatFrompresence.”myhome in Atlanta I can drive to a number of these sites within an hour. The Chattahoochee River on the city’s north boundary was once the cordon separating the United States and the Cherokee Nation. Not far from Truist Park, the stadium where fans of the Atlanta Braves pretend to be Indi an by waving foam tomahawks and chanting a parody of a war cry, the 285 beltway cuts across land that belonged to a Cherokee family named Lynch, who cultivated a vast orchard on this side of the Chattahoochee, with more than two hundred peach trees. While the Trail of Tears is a familiar sto ry, Cherokees were being driven off this

property before then. “All I ask in this cre ation,” sang men in the earliest days of the nineteenth century, “is a pretty little wife and a big plantation / Way up yonder in the Cherokee Nation.” The State of Georgia did all it could to accommodate this request. If you were white and had eighteen dollars to your name, you could purchase a ticket to one of Georgia’s land lotteries and stand a chance at winning a homestead in excess of a hundred acres. Though the Cherokees’ right to the land had been affirmed by the U.S. Supreme Court, the lottery results were enforced by the Georgia Guard, a paramil itary outfit acting at the behest of the state. No one was exempt from such theft, no matter how powerful or wealthy. John Ross, the first elected Principal Chief of the Cher okee Nation, came home one day in 1835 to discover someone else living on his land. Ross had been in Washington, D.C., meeting with lawmakers, and in his absence his barn, stable, and furniture were confiscated. There was no sign of his wife, Quatie, or their children. Before setting off to find them Ross had to pay for a night’s rent in his own house. Eventually the town of Rome, Geor gia, would be built on this spot, at the confluence of the Oostanaula and Etowah Rivers. According to Saunt’s database, Ross’s property was valued at $17,797.25, equal to half a million dollars“Theytoday.took everything,” said Allen Buck, a fifth-great-grandson of Ross, who is named for one of the Principal Chief’s brothers. An ordained Meth odist minister, Buck presides over the Great Spirit Church in Portland, Oregon. He grew up in Oklahoma, not on the reservation set aside for Cherokees after removal but in the college town of Norman, and while they are separated by seven generations, Buck likes to joke that when he looks in the mirror he thinks of a photograph taken of Ross when the chief was approximately the same age Buck is now. “I have his big old fat earlobes, and crazy hairs growing out of my eyebrows,” he said. “I’m afraid I sort of look like him.”

“I didn’t,” he said, “but I will tell you, I have always had these recurring dreams where I’m being accused of something that I didn’t do. It’s some form of I didn’t do this, this isn’t my fault, why can’t anyone hear me, why can’t anyone see me, why are they putting my family in jeopardy, why are they taking these things from me?

N orth of the town of Rome one enters Tennessee, which is a Cherokee word, of course, as are so many place names in this southernmost realm of Appalachia. Nantaha

“Maybe everyone has those dreams that are part of the collective human unconscious, but I think it comes from further back. It’s baked in, the grief and the sorrow and the trauma of what happened.”

The Trail did not extinguish the Cherokees’ language, the traditions of their culture, or their claims as a sovereign nation.

When he was young Buck did not hear much about his family’s Cherokee past. He was raised by his mother, a white woman, and he told me that in school, “I was taught the American mythology about the Trail of Tears. They celebrate the pioneers, the people who took the land. Boomers and Sooners.” It was only at family reunions that Buck would pick up other types of stories, finding out that Quatie Ross died on the Trail of Tears, for instance, her final resting place in Little Rock,“I’mArkansas.stilllearning how to be Cherokee,” Buck said, “how to be traditional Cherokee, what that means. There’s a lifetime of work to do.” He spoke in particular of adhering to the principle of gadugi, a Cherokee word that translates loosely as working together, in the spirit of the collective, and he also said he was passing on rites such as going to water, a traditional Cherokee healing practice, to his children. “Our ceremonies,” he told me, “bind us to the past, the present, and the future.”Later, as we looked at a survey of Ross’s property, one made in the months before it was given away by lottery, I asked whether, at any of those family reunions, Buck learned about the time Ross was suddenly turned out of his home.

la. Cullowhee. Hiwassee. When we say these words we recognize, knowingly or not, the title the first known inhabitants inscribed on the region, and it is sometimes forgotten that there are still thousands of Cherokees who live in this part of the United States. In 1838, in the midst of removal, a handful of Cherokees fled into the mountains and hid from the army. When the roundup was over they came out and joined another group who had been given permission from the United States government to stay in the East, based on treaties signed in 1817 and 1819. Later this remnant became known as the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, a federally recognized tribe.The headquarters of the Eastern Band is in Cherokee, North Carolina. The town is a few miles from Kituwah, an archaeological site lo cated in the floodplain of the Tuckasegee Riv er. A small rise in the center of the field indicates the remains of an ancient council house, said to be the source of the fire from which all the settlements in the old Nation were lit. Though it has largely vanished, Kituwah, “the mother town,” as Cherokees call it, still has the power to inspire. Cherokees the world over come to sprinkle dirt on the mound, in the hope of raising it to its former dimensions, and on the morning I drove by, the cellist Yo-Yo Ma was seated near the river performing for a class of schoolchildren, a thin mist scudding across the low ridges and mountains that encircle the field.

The Principal Chief of the Eastern Band is Richard Sneed. He moved to Cherokee in the 1980s—he lived in New Jer sey until he was fourteen—and is serving his third term as Principal Chief. In many ways, little about the job has changed since the days of Ross. Sneed is constantly engaged in negotiations with the federal government, pressing it to uphold pacts made with the Cherokees. Before our interview he was on the phone about Tellico Lake, a federal proj ect of the 1970s that dammed the Little Ten nessee River and flooded acres of Cherokee burial grounds in the process. The Eastern Band was promised this land would be taken into trust, and “we’re still fighting that fight to this day,” Sneed said. Over the years Sneed has done a fair amount of research on his genealogy. His family tree is exhaustive, dating back gen erations, to the earliest known Cherokee records. “This is not our story,” he told me

24 FALL 2022

“We have value systems that predate this country by thousands of years,” Sneed said to me, “and we have to be deliberate about identifying what those values are, and delib erately go back to those things and deliber ately teach those things and, more important, be deliberate in living it out.”

“What happened in Wallowa,” said Buck, “is an inspiring thing and gives me hope. Does it make anything right? I don’t think so. But there’s some healing there.”

I f removal does not define the Cherokees, that leaves another question: How much does it define Georgia? In the end, so much about this state, its property lines, the make up and patterns of its population—for it was slaves who worked the land that was cleared of Indigenous people—comes back to the decision to expel the Cherokees. And even if it can’t be settled with any degree of finality, it is still important that we ask this question, since it signals a willingness to confront the facts of history.

when our conversation touched on the re moval period. On the pages in front of us was a name, Sololah, that can be found in Saunt’s archive. A relative of Sneed’s father, Sololah lived on two acres, in a cabin of twenty-four square feet, near Robbinsville, a short drive along Highway 28 from where Sneed and I were speaking now. I understood his point. So much of what is written about the Cherokees tends to empha size removal, whereas the Eastern Band has maintained an unbroken connection with a piece of their homeland for centuries. And yet even though he was talking about the Eastern Band, I was reminded of something DeLanna Studi said after walking the Trail of Tears with her father. Studi, an actress and playwright from Liberty, Oklahoma, re traced the route west in the summer of 2015, nine hundred miles beginning at Fort Butler, near Murphy, North Carolina, where one of Studi’s ancestors had been held prisoner in 1838. Though it was painful, she said, “to see how much we lost,” what Studi came to real ize was that removal “doesn’t define us as a people,” since the Trail did not extinguish the Cherokees’ language, the traditions of their culture, or their claims as a sovereign nation.

After he moved to Portland and took over the pastorate of Great Spirit, Buck began giving parcels of land that were in Methodist ownership to Indigenous nations. In 2021 he transferred a lot in Idaho’s Wallowa Valley to the Nimi’puu. The size of the property was not large, but it gave the Nimi’puu a presence in the Valley, their sacred homeland, for the first time since they were sent out of it in the 1870s, at the end of Chief Joseph’s war.

While Saunt thinks of stumbling stones as a way, as he put it, of restoring a presence on the landscape that was erased, he does not believe an exact equivalent can be installed in the territory of removal. “Those are in urban areas, on sidewalks,” he said. “You can’t do the same with the Cherokee Nation. It’s very rural.”

OXFORDAMERICAN.ORG 25

“Acknowledgment is only the entry point,” Buck said to me when I asked if it was time to move beyond commemoration and think of broader acts of restitution—a monetary reparation, perhaps, to the heirs of those who lost their holdings, or returning the country’s national parks, tracts that in most cases were illegally taken, to tribal hands.

Saunt is not of Indigenous descent. He was born in San Francisco, and though he has been teaching at the University of Georgia since 1998, it was only recently that he turned his attention to the removal of the Eastern tribes. A few years ago, Saunt read some letters written by his grandfather, a Jewish engineer who escaped from Hungary and settled in Ohio during World War II. “That got me thinking about deportation and the story of where we live,” he said, adding that the ex pulsion of the Cherokees prefigured pogroms that occurred later in countries like Algeria and Russia. “State administrators looked to the United States as a model for what you do with populations you don’t want.”

So much inheres in the land that cere monies like this have more than a symbolic power. Sneed told me it was “a dangerous precedent to rewrite history. What’s done is done.” But he had experienced firsthand what Buck was talking about. For generations Kituwah belonged to a white family, until the Eastern Band purchased the site in the 1990s. Reclaiming Kituwah, Sneed said, set off a “renaissance of our arts and crafts, our language. Getting it back was very healing.”

Much of it is rural, true, yet it would be easy to place a stumbling stone in Rome, Georgia, on land that belonged to John Ross. There is in Rome a footbridge named after Ross, but no mention of land lotteries, of expulsion or dispossession. It has all been consigned to the past, that remote era where America has kept removal for so long, deter mined to see it as just another bloodless his torical force, a sin of our fathers, beyond the reach of culpability. And yet as anyone who visits Rome can attest, watching shoppers drift in and out of the Blue Sky Outfitter, or golf carts moving through the Coosa Country Club, the theft of land is still paying out.

“Decolonization always involves giving back.”

In essence, this was the vision articulated by Buck, who also referred to intentionality as an important part of Cherokee identity, the conscious seeking-out of language and custom. He and Sneed both became citizens of a tribe by virtue of their ancestry, one in the Cherokee Nation, one in the Eastern Band, yet they believed being Cherokee was not something you could simply inherit. It had to be daily striven for, daily renewed.

On the day we met in his office at the Uni versity of Georgia, Saunt showed me the picture of a stumbling stone. These are the memorials, conceived by the German artist Gunter Demnig, found on sidewalks in cities across Europe, small stones inlaid with a brass plaque that bears the name of someone who lost their house or business and was deported during the Holocaust. Walking the streets of Berlin, or Budapest, one cannot avoid them. The stones enact a pause, a fig urative stumbling, interrupting one’s daily routine to occasion, in their gentle way, a kind of Whilereckoning.heplansto publish the archive next year, and recently received a Guggenheim Fellowship to continue his work, Saunt knows publication and completion are not neces sarily the same thing. Records can be linked indefinitely, and Saunt intends, one day, to show the chain-of-title for each property in the system, as well as the census data for people like Colonel Neely, who took home so many of Chewey’s possessions on that day in June of 1838. In this way, some Georgians will be surprised to learn the source of their cherished heirlooms.

To acknowledge removal in ways we have not yet done, finally, be it in the form of stum bling stones, land return, or something else, might add meaning to our country’s image of itself, to our parades and ritual genuflections. Without practiced equality or justice, after all, flag-waving and protecting statues be comes little more than performance art. “The hard part,” said Buck, “is getting institutions to really let go. It has to start with people in power and in privilege telling the truth about what happened.” That, he said, is the value of Saunt’s archive, the way it might push us toward recognizing not only the truths of the past, but also that there is a healing whose benefit might extend to us all.

26 FALL 2022 The New Loss Is Not Like the Old Loss, 2022. Duraclear and archival pigment print on LED lightbox, 44 x 38 inches by Melanie Willhide. Courtesy the artist and Von Lintel Gallery, Los Angeles