164 minute read

Sting Like a Bee, by Leslie Pariseau

Sting Like a Bee

BY LESLIE PARISEAU

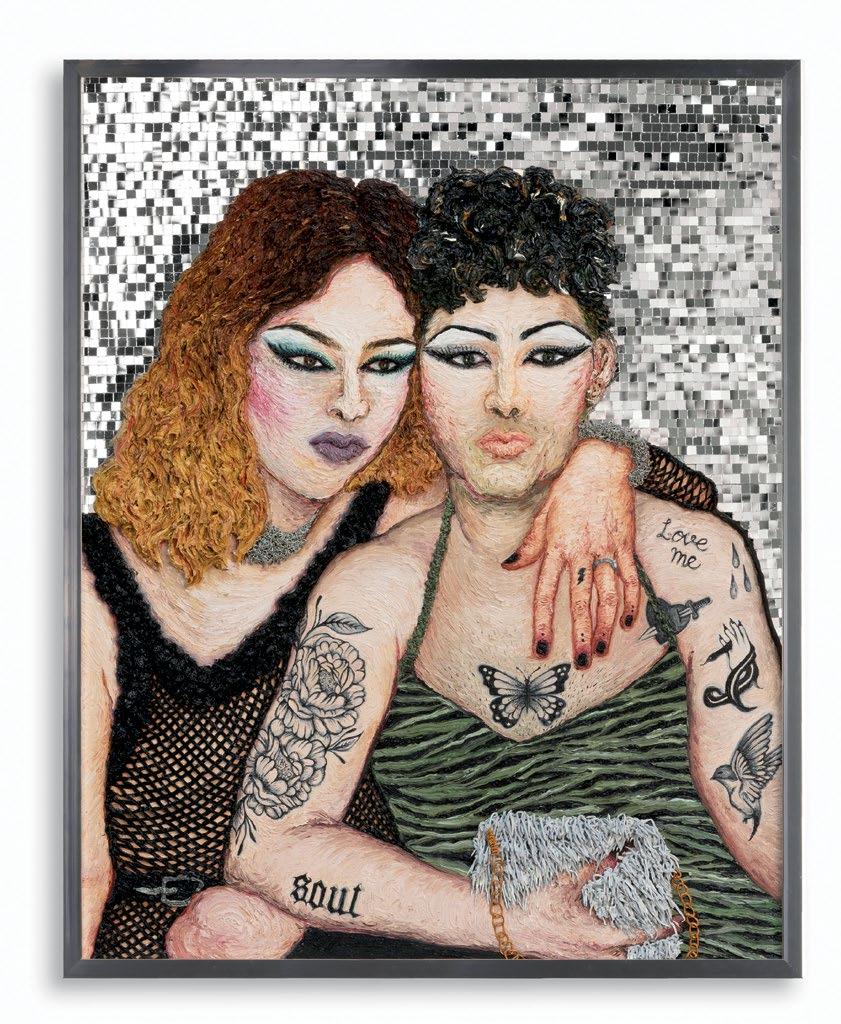

Resa “Cinnamon Black” Bazile is seemingly everywhere, and yet difficult to track down. After some digging, I found Bazile on a Tuesday afternoon in February at the desk of the New Orleans Historic Voodoo Museum, chatting with tourists who had wandered in off Dumaine Street in the French Quarter. She wore a matching cerulean blue skirt and head wrap, and a ruffled African print top. Faux eyelashes, beaded hoops, and a stack of necklaces and onyx rings completed the look. When Bazile learned that it was one visitor’s birthday, she insisted on performing a candle-lighting ceremony to bring good luck, asking the woman’s partner to film while we all sang “Happy Birthday” several times over until she blew out the candle. Bazile works two days a week at the museum. She had started there back in 1980 after winning a Marie Laveau lookalike contest, and so, when I couldn’t find her anywhere else, I’d call the front desk and talk to her there. (Bazile has a cell phone. It just proved to not be the most effective tool for getting in touch.)

As people came in and out of the ramshackle lobby, she answered the phone, ribbed guests, and helped them pick out voodoo dolls and other trinkets. She showed off the neck patch she was sewing for her Indian suit: rows of cowrie shells and faux pearls were nestled amid gold rickrack. Though she preps for Mardi Gras throughout the year, it picks up in the weeks following Twelfth Night, and she said her hands have been busy sewing in a race to finish. “You can take a photo,” she said, holding up the intricate piece, “but you can’t show anyone.” The power of an Indian’s suit lies in her reveal in the battle for “pretty.”

That day, Bazile was a voodoo priestess, but she lives a number of different lives that take her all over the city. She’s also a baby doll and a Black masking Indian queen, and she appears in films and productions, often as a priestess. These branching paths, she said, have taken over her house: “One room is voodoo, one room is baby dolls, one room is Indians.” Of course, these titles have little context or meaning beyond New Orleans, and Bazile’s place in the universe is inextricably bound to a world that doesn’t always abide by time or technology. Which is a long way of telling you that I often had a hard time hunting her down.

The next time I found her was on Florida Avenue along the canal in the Lower Ninth Ward, a week and change before Mardi Gras. Parked outside of an abandoned community center, I called her wondering if I had the wrong address. She begrudgingly reoriented me, and couldn’t promise that she had much time to talk. She was at Victor Harris’s house, the big chief of the Spirit of Fi Yi Yi and the Mandingo Warriors, where the tribe was sewing against the clock. She greeted me out front alongside spy boy—the person who keeps watch for the big chief—Albert Polite, who stood sentry at the door. He informed me that I was not to talk to Chief Victor Harris. Bazile led me down a set of stairs while Polite called out, “Fire in the hole!” to indicate our entrance. At a work table sat Jack Robertson, the Warriors’ designer. He was mulling over a swatch of African print and a row of feath-

ers, which would become a headpiece for one of the tribe’s young warriors. The suits are spiritual, and Harris’s designs come to him in visions. For many Indians, they take the entire year to make, the construction undertaken in secret so that no other tribe will know what’s in store. Bazile settled onto a stool, dreads swinging around her shoulders, looped through with gold rings. It was the rare moment when she appeared not in costume, unguarded, not performing.

That day, Bazile was an Indian. If you don’t live here, it’s possible you’ve never heard of Black Indians or Mardi Gras Indians—terms that vary depending on which tribe or member you ask—but they are one of America’s most majestic and dramatic examples of extremely local, longstanding folk tradition. On Mardi Gras day, dozens of tribes emerge on the streets of their respective neighborhoods, dressed in suits made of intricate beadwork and layers of feathers. They’re often described as three-dimensional, sculptural in their grandiosity of scale. Some suits can weigh over 150 pounds and tower four feet above their wearer’s head. (In one photo I unearthed in the Historic New Orleans Collection from 1984, a wildman’s bonnet contained an enclosure housing a live parakeet.) But the Indians also come out on St. Joseph’s night, which was historically an evening of violent battles between the tribes; since Big Chief Allison “Tootie” Montana of the Yellow Pocahontas called for peace in the 1960s, the battles have become more symbolic, with chiefs parading to see who is the prettiest. The Indians also come out on Super Sunday in the most epic of New Orleans’s Second Line parades. Bazile explained that the suits they’d been working on all year would be worn on all three occasions. Her suit, a mass of white feathers and black and gold fringe, was made up of dozens of patches (patches are the individual pieces that compose a suit) and had taken her months to sew.

The tradition of African Americans masking in the iconography of Native American people has been around since the mid-nineteenth century, derived from a gumbo of origins, including Wild West shows that passed through the city in the 1880s, the mutual aid that Blacks and native people provided one another before and after the Civil War, and the ancient ritual of masking in West and Central African cultures. The tribes are organized in a male-dominated hierarchy that flows downward from a big chief—spy boy, flag boy, wildman—with the queen often seen as a kind of atmospheric accessory to the chief. It’s a role that’s evolving in some tribes with more codified responsibilities, and in Bazile’s case was forged by the queen that came before her, Kim “Cutie” Boutte.

When Boutte, at age fifty-five, died in 2020, killed by a stray bullet in a retaliative shooting, Bazile, who had been second queen, became the big queen. It’s clear the tribe is still devastated by this loss, and several times throughout our conversations, Bazile expressed missing dancing next to Boutte in the streets. “That’s my big queen,” she would say, in present tense, as if Boutte had simply transubstantiated. “She was remarkable. She took care of all the children. She was small but she sting like a bee,” said Bazile. Boutte became a little queen when she was five, ascending to big queen and eventually became recognized all over the city as one of her era’s culture bearers.

“You don’t pick the tribe. The tribe picks you,” said Bazile, who has been in the Spirit of Fi Yi Yi for over twenty years. “You have to be invited into it. You have to be a part of a family, a part of the bloodline. You can’t just put on the suit or you’re fake. Like a fake Gucci.” Some members are born into the tribe, like Bazile’s grandchildren, while others are invited based on kinship and understanding.

While Bazile spoke, Big Chief Victor Harris appeared in the sewing den, wearing a red skull cap. He arranged some of his patches on the table, and when Bazile disappeared upstairs for a moment, began talking about his suit, his calling to the tribe, what it feels like when the Spirit takes over, and the meaning of a queen to the Warriors. “A big queen should be beside the chief at all times,” Harris said. “Not behind, beside.”

When Bazile reappeared, she brought prepared plates of fried fish, stuffed crab, and egg rolls for Robertson and Harris. “What does a queen do? What I’m doing right now,” she said laughing. “It’s like a support system; you make sure the tribe has what they need. You look after the children, work with the children so they know what to do.” Her own grandchildren are part of the tribe, the boys looking up to the big chief, playing Indian as soon as they can run.

The next time I tracked Bazile down was on Mardi Gras morning, at Kermit’s Tremé Mother-in-Law Lounge, a New Orleans institution founded by Ernie K-Doe back in 1994. The music club was taken over by local legend trumpet player Kermit Ruffins in 2014, and presides as a mainstay of community and gathering in the Tremé. Donning a white, ruffled dress, smocked with silver sequins, and matching bonnet, Bazile stood outside, posing for photos with her group, the Tremé Million Dollar Baby Dolls, awaiting a local news crew’s lenses. She twirled a lacy white parasol, and a Black doll dangled from her shoulder. This morning, she was a baby doll, the most elusive of the city’s maskers.

“It used to be that the baby dolls only came out once, maybe twice a year. It used to be so special,” Bazile said some weeks later over coffee. “But now it’s once a month or so.” Though still a lesser-known tradition, the baby dolls are ever more visible around the city, with groups emerging at Second Lines and neighborhood festivals. The New York Times recently featured a short documentary by filmmaker Vashni Korin on the dolls called You Can’t Stop Spirit. “Like with any folk culture, these things are not recorded and put in archives,” said Kim Vaz-Deville, professor at Xavier University and author of The “Baby Dolls”: Breaking the Race and Gender Barriers of the New Orleans Mardi Gras Tradition.

Of course, the origins of dolls are manifold, with one story tracing the tradition back to a group of friends and family in the Tremé neighborhood in the early twentieth century who were influenced by the fashions of vaudeville and began dressing in satin dresses and bloomers to evoke the look of a child’s baby doll. Another story pins the origins to Storyville’s red light district sex workers who satirized the idea of dressing like a little girl, wearing garter belts and throwing money at male onlookers as they paraded through the streets. (Apart from New Orleans, in Trinidad, there is record of women dressing as dolls and/or carrying dolls and shaming men into giving them money.) Regardless of origin, dressing as a baby doll and dancing through the streets, above all, provided agency to Black women who were historically disallowed from participating formally in Mardi Gras; up until the 1960s, official parading, for the most part, was the territory of wealthy, white Uptown men whose exclusive krewes dominated the mainstream depiction of the holiday. Dressing as a baby doll provided visibility on a holiday where women, let alone Black women, were relegated to the literal sidelines.

Bazile recalls the first time she saw a baby doll. She was six or seven with her grandmother in the Calliope Projects and saw the

dolls coming down the street toward Rose Tavern. They were buckjumping (the rapid, rhythmic dance step associated with New Orleans Second Lines) and pulling feather boas between their legs. Her grandmother grabbed her and tried to cover her eyes, but the image was etched into Bazile’s consciousness; she wanted to be a doll. Around the age of twelve, she and her friends started their own doll group under the guise of Cabbage Patch Dolls, so her grandmother couldn’t read her real intentions. Years later, as a young mother, she was hanging around with some of the Tremé’s older women—including Lois Andrews (Trombone Shorty’s mother), Merline Kimble, and Antoinette K-Doe—listening to their stories, when the topic of baby dolls came up. Maybe it was time to bring them back. The tradition had died out, which Vaz-Deville explained was, in part, a product of the civil rights movement, when the importance of dignity—in profession, appearance, and public behavior—became paramount in pushing integration. “Folk cultures weren’t seen as respectable,” said Vaz-Deville.

When Bazile heard the Tremé women talking about the dolls, she perked up. They called upon Mariam Batiste Reed in the Sixth Ward to hear about her mother Alma, who had masked as a baby doll, and eventually the Gold Digger Baby Dolls and the Ernie K-Doe Baby Dolls were born. Bazile joined the former, but would run a renegade—join other groups—when she could. After Hurricane Katrina, she started her own group, the Tremé Million Dollar Baby Dolls, an homage to the Million Dollar Baby Dolls, one of the earliest known groups from the 1910s.

Bazile’s aim in helping revive the dolls, of which there are about seventy-five today by Vaz-Deville’s estimation, is intertwined with the idea of women as a representative of a culture and a community. She acknowledges the role’s historic association with sex work, but disavows it as a contemporary thread. Today, the role is one of embodiment and power, rebutting the negative stigma of legend. “When you are a baby doll, you’re doing a reenactment. They are women who have their own cars, women who have their own jobs. Women who are mothers, who are caretakers of the elderly, women who people seek out to ask questions,” she said. Whereas some modern-day dolls will appear in short shorts and bustiers, the dolls that Bazile claims are dressed in ruffled skirts and bonnets, carrying parasols, baby bottles, and pacifiers. They do the dance of the jazz. “You don’t show your breasts, you don’t wear high heels because you don’t miss that with a baby.” Their style of dance may change depending on the audience; Mardi Gras day is a lively two-step on account of being a family event, while other parades and appearances might allow for more provocation.

On Mardi Gras morning, she led the dolls out under the Claiborne Underpass with a brass band following behind, echoing off of concrete and cars. A small crowd followed, and as they moved through the Tremé, people stopped to watch. At one intersection, the Cheyenne Hunters tribe, dressed in peachy pink feathers, began to trail behind, entranced by the jovial women in satin, swinging parasols and shuffling along.

At last the dolls reached the temporary home of the Backstreet Cultural Museum, a hub started by the late Sylvester Francis, dedicated to preserving Indian culture. The Mandingo Warriors waited there for Bazile, who would quickly change suits and join them as queen.

But the transition didn’t go as planned. In an unexpected turn, the Warriors left without her and she had to catch up a couple of blocks away, where they were facing off with Black Feather, a tribe from the Tremé. When I sat down with Bazile some weeks later, she told me it was a test. “The men want us to believe we don’t have power, but we do,” she said. The power, as she explained, is in caretaking, guiding the children into their understanding of the culture, and supporting the chief in his work, a role that seems, in some ways, counter to the autonomy portrayed in the culture of the dolls.

When I ask Bazile what it’s like transitioning from a tradition that is entirely about women forging a path of visibility and power to one that is dictated by male energy, often performed as a show of strength, she doesn’t hesitate to explain its symbolism: “It’s another lesson to be learned: how to be in a male-dominated society when you’re a powerful woman,” she said, leaving it at that. Bazile has considered that it might be time to transition away from the dolls to keep up with her duties as a queen. But in seeing the thrall she holds over people, in her white ruffles and bejeweled boots, it’s difficult to imagine that she could ever fully let this life go.

The final time I see Bazile is on Esplanade on a brilliant April day the week of Jazz Fest. She’s just come from a performance and is dressed in black and brown tribal print, ceremonial white paint dashed and dotted around her eyebrows and down the bridge of her nose. Again, she’s a voodoo priestess, neck swathed in cowrie shells and beads, fingers jangling with silver rings. She orders a decadent praline-flavored iced coffee topped with a mountain of whipped cream. She commands the attention of everyone she walks past. One woman stops her, says she recognizes her as the host of a live TV show from back in the 1980s in which Kermit Ruffins was her house band.

She tells me about how she got her stage name, Cinnamon Black, from the late Charles Gandolfo, who founded the New Orleans Historic Voodoo Museum. She was a twin, she tells me, but her sister died at birth. She talks about the idea of the Marassa Jumeaux, the divine twins of voodoo, and how her name “Resa” echoes the term. We talk about the nature of transition, the fact that it’s inevitable. “Everything must change. Nothing stays the same,” she said, a chorus she’s sung in conversations before. I ask if she’s considered what she said about leaving the dolls. “Baby dolls are always going to be a part of my spirit and my soul, but now that I’ve accepted this big responsibility it’s going to require more of my time and a hundred percent of my attention.” But she also talks about her first days in the dolls, dancing through the streets past porches where older women who remembered the dolls from decades before would stand up and wave at them, bewitched by their return.

“My dream has come true. My dream is to see baby dolls all over. There are so many baby dolls I can’t even count them anymore,” she said. “When I leave, I’d like to leave them with a story. Everything in life has instructions. Some of us come with them inside of us and some of us don’t. Birds came with instructions how to fly. Trees came with instructions how to grow leaves.”

As the sun wanes on the avenue, I pull up a few photos that my friend the photographer Pableaux Johnson has taken of her over the years. The final one shows Bazile walking the route on Super Sunday, her Indian suit glittering. She is magnificent, carrying the weight of her creation through the streets. When she sees it, she is full of delight, “Oh! Who is she? I would like to know her. Can I meet her?” Bazile, in this moment, is not a priestess or an Indian or a baby doll, but a child again, stunned at the wonder that such a creature could exist.

UniquelySouthern. Distinctly Mississippi.

For true fans of Southern culture, Mississippi is a place unlike any other. Many of the South's literary, musical, and artistic traditions are rooted here, offering travelers a unique opportunity to deepen their understanding and appreciation of Southern creativity and its cultural impact.

JIMMY "DUCK" HOLMES, BLUE FRONT CAFÉ, BENTONIA

The Delta

The Delta, in the northwest part of Mississippi, is the “Birthplace of the Blues” and has also been called “The Most Southern Place on Earth.” Here, according to legend, Robert Johnson sold his soul to the devil at the Crossroads of Highways 49 and 61 to become a masterful blues performer. While the Crossroads story has no real basis in fact, there’s no disputing the wealth of musical talent that the region produced, from pioneers like Muddy Waters, John Lee Hooker, and B.B. King to present-day luminaries such as recent GRAMMY® winners Bobby Rush, Christone “Kingfish” Ingram, and Cedric Burnside.

The Mississippi Delta is home to three museums dedicated to its musical heritage: GRAMMY Museum® Mississippi (Cleveland), the B.B. King Museum and Delta Interpretive Center (Indianola), and the Delta Blues Museum (Clarksdale). Beyond the blues, the Delta is emerging as a destination for food travelers. The city of Greenwood, in particular, has elevated Southern culinary tradition to new heights. Local favorites include Fan & Johnny’s, which offers creative takes on Deep South and international cuisine, and the Crystal Grill, known for serving up cream pies topped with “mile-high” mountains of meringue.

THE CROSSROADS, CLARKSDALE

ELVIS PRESLEY HOMECOMING STATUE, TUPELO

The Hills

The Hills Region of northeast Mississippi encompass the lush, rugged woodlands, clear lakes, and bubbling streams of the Appalachian foothills. Oxford is home to the University of Mississippi and one of its most influential students (and likely its most successful drop-out), William Faulkner. Faulkner’s home, Rowan Oak, is open for tours, and visitors can view his office and the vintage Underwood typewriter he used to compose many of his works. Visitors to the University can also see a civil rights monument and statue commemorating the courage and determination of James Meredith, a hero of the civil rights movement and the first African-American student to integrate Ole Miss in 1962.

Tupelo, a city just one hour to the east of Oxford, is the birthplace of Elvis Presley. Before he became the world’s most popular entertainer, Elvis lived in a humble tworoom shotgun shack, now a small museum located within the city’s 15-acre Elvis Presley Birthplace Museum. Tupelo boasts three statues, several murals, and numerous sites dedicated to the “King of Rock ‘n’ Roll.”

WILLIAM FAULKNER'S OFFICE, ROWAN OAK, OXFORD

In Meridian, the Mississippi Arts and Entertainment Experience (The MAX) showcases the lives and works of Mississippi’s greatest writers, artists, and performers – including Jimmie Rodgers – through a variety of interactive experiences and exhibits. Be sure to check out The MAX’s calendar for concerts and other special events before you visit.

THE MAX, MERIDIAN

THE MAX, MERIDIAN

BIG APPLE INN, JACKSON

Capital/ River Region

Jackson is Mississipp’s capital city, and it’s where you’ll find several of the state’s premier cultural attractions, including the Mississippi Museum of Art, the Museum of Mississippi History, and the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum. The “City of Soul” and its surrounding metro area boast a vibrant restaurant scene, offering everything from elegant “tasting menu” experiences (at Elvie’s and Southern Soigne) to the iconic pig ear sandwiches of the Big Apple Inn. The Big Apple Inn is located on Farish Street, which was once a bustling center of African-American commerce. Their building was a frequent meeting spot for civil rights activists and leaders during the civil rights era.

Vicksburg, located 45 minutes to the west of Jackson, is a must-see for American history buffs. Visitors come from around the world for an opportunity to take an immersive walk through one of the Civil War’s most pivotal military campaigns, the siege and battle to claim the city.

OHR-O'KEEFE MUSEUM OF ART, BILOXI

Coastal Mississippi

While Coastal Mississippi is perhaps most famous as a casino destination, the cities lining Mississippi’s 26 miles of beaches have an important cultural heritage, as well. Ocean Springs is home to the Walter Anderson Museum of Art which celebrates the art and legacy of the naturalist, visual artist, and printmaker. Nearby, in Biloxi, the Ohr-O’Keefe Museum of Art showcases the works and history of the “Mad Potter of Biloxi,” George Ohr. The region is also home to the University of Southern Mississippi’s diverse campuses - 300 acres in Hattiesburg and 52-acres beachfront in Long Beach.

Mississippi’s coast is also the perfect place to sample fresh Gulf seafood. One of Mississippi’s most famous restaurants, Mary Mahoney’s Old French House, has served guests, including U.S. presidents, dignitaries, and celebrities, for three generations. The restaurant is appropriately named as it is indeed located in an old French house that was built in 1737 when Mississippi’s coast was claimed as a French territory.

MARY MAHONEY'S OLD FRENCH HOUSE, BILOXI

Come Wander With Us

My five-year-old told me he was a Buddhist monk in his past life.

I didn’t think much of it at the time. Kids, you know. He went into detail about his monastery in the mountains of Tibet, about his best friend, Akar, and the process of making tsampa and yak butter tea. When he told me this, we were eating breakfast. He shared a mantra with me over his oatmeal, Sanskrit floating off his tongue as he pushed away his tiny, tiger-shaped plastic bowl.

I asked him: “Excuse me, where does your bowl belong?” I wasn’t about to let him know I was terrified of him. His father had already gone to work so I had no backup; I knew the odds were stacked against me. What’s worse is for the past few months my son has been having sleeping problems. We’ve tried everything: sound machine, sleep sack, bedtime routine, sleep study, prayers of supplication to every god we could think of. This slip in reality could be related to his sleep deprivation. His mind was now going wild at the age of five—and so my mind was going wild at the age of thirty-seven. They don’t tell you about these things when you’re pregnant. They don’t tell you that your child can be a terror and you can’t send them back and ask for another one.

I have never really connected with my son the way a mother and child should. We have a strict business relationship—I make sure he stays alive, and he slowly wears me down year after year by revealing all my faults and innermost fears. It’s his father who’s the better mother—he’s the one who should have been pregnant with him. Oh, he would have melted every time Leif jabbed his side with his powerful baby fists and woke him up at all hours of the night. In all honesty, I just didn’t know what to do with Leif—he was so foreign to me. I didn’t understand him, even though he was my own flesh.

I wasn’t the one who particularly wanted children, that was Owen. He wanted three—we compromised on one, as it was me who was putting in the heavy lifting. I hemorrhaged during Leif’s birth and nearly died. The first time I saw my son he had already been in the world for two days. Two days of bonding with everyone else except me. Two days of touching other hands, seeing other faces. I sometimes wonder if I’d had that first contact with him, would we have the bond that we should? Like those women who pull their own babies from their bodies, and in all their wetness and dripping fluid, hold them to their bare chests crying and laughing, forgetting all the pain and labor, letting the umbilical cord transfer all the needed nutrients, latching their babies to their breasts and feeding them what nature intended—colostrum. Colostrum, which I had to pump out and dump down the drain. I felt like a fake, the shocking scar across my belly to prove it. I no longer wore bikinis or exercised in only sports bras. Motherhood had taken that from me—had taken my body.

Iwas tying Leif’s shoelaces for school in the morning after another night of trying to soothe him back to sleep—it was my turn last night—when he told me of his other past life as a deer.

“I felt a hurt here,” he pointed to his chest, “in front of my two babies. I tried to run away from it, but the pain made me fall down and then everything went black and now I’m Leif.”

It was odd to hear him embody a deer and describe feeling a gunshot. I was sure we never told him anything about hunting and killing animals. I assumed he’d picked it up from some D-bag kid at school whose father goes out every weekend to destroy nature and bathe in the blood of his victims.

“Leif, we don’t talk about killing.”

I knew kids could have big imaginations, but up until this point, he’d been a pretty dull kid. No imaginary friends, no pretending he was a unicorn or anything.

Leif announced at dinner that he was not going to eat meat anymore by screaming the moment I put a piece of chicken to my lips.

“We don’t eat animals. We are animals,” he yelled and started crying over his cut-up chicken.

“Buddy, you’ve always eaten meat,” I said.

“I didn’t know what meat was. Marshall told me it’s dead animals.”

I always hated that little punk.

“You don’t have to eat it if you don’t want to,” Owen said, taking the pieces of chicken from Leif’s plate. I gave him a look, which he understood, and he gave me a look back. Parenting is just a bunch of looks sometimes. I didn’t think we should be the parents that let our kid run all over us—he didn’t think we should run all over our kid.

“We have to give him a proper burial,” Leif said.

“Of course, bud. We can do that.” God love him, Owen gathered the chicken from our plates and picked up the carcass. “What should we do?”

“Backyard.” We proceeded to the yard, Owen carrying the sacrifice. I wasn’t about to waste a whole rotisserie chicken on the raccoons. I sped up to Owen.

“I’ll distract him and you go hide it in the refrigerator,” I whispered.

“No way, he’d know.” He’s such a good dad, damn him. So, Owen dug a hole while Leif picked flowers from the garden and arranged them around the dissected chicken carcass. Once they were covered over, Leif began muttering in Sanskrit while spreading flower petals on the grave. He took his hands to prayer position at his heart, brought them to the middle of his forehead, and bowed.

“Namaste,” he said. Owen and I looked at each other. “We can go inside now.” He turned and ran inside, putting on the TV, dirty knees and running nose, and monk voice. Owen and I stayed outside.

“Vegetarianism, Owen? Why encourage that?”

“Why not? I think it’s cool that he’s socially conscious at such a young age.”

“But we can agree that he needs to see someone at least, right? I mean, a Buddhist monk, a deer?” He looked at his feet, pushing a stick with his shoe.

“When I get to the office in the morning, I’ll ask Rodney who his daughter sees.”

“I think it would be beneficial if you all went vegetarian with him, you know, show him that you’re supportive. He’s a serious little guy.” We were sitting in the therapist’s office after Leif’s first session.

“But what about the reincarnation monk stuff, and the deer—that’s unsettling right?” I said. Owen nudged my shoulder. The therapist gave an annoyingly cryptic therapist smile that probably meant she thought we were bad parents.

“Children often develop vast imaginations and stories as part of a coping mechanism when things change or they feel that they need something to make them secure.”

“You’re saying he doesn’t feel safe with us?” I said. Owen put his head in his hands. I didn’t get it apparently—I never do.

“Not really, but in a way. It could be something that happened at school. The big thing that you all need to show him is your support—he needs to know that you are there for him and he can talk to you if he needs to.” She paused. “Show an interest in the things he has started focusing on, like the monk and the deer. You may find it a bonding experience.”

So, I started asking him questions about his monk and deer selves. The therapist said we should encourage this, as it is a natural part of his development. I decided to leave work early and pick him up from school to take him for ice cream. Usually it was Owen who did these things, but I was determined to make a connection with him.

His mouth was full of chocolate ice cream; it ran down his chin and dripped onto his polo shirt, but I didn’t say anything about it. I just let him eat. The shop was local, organic, and had vegan options in case he wanted them. It was nice out, the rain had finally stopped, so we sat outside at the black iron table and watched the people walking and riding by with dogs and babies.

“So, what did you like most about being a monk and a deer?” I looked up from my bowl of untouched vanilla. He thought for a moment then put his spoon down and clasped his sticky hands together.

“I liked to ring the gong and see the mountains. The gong made me feel like my body was full of bees. Being a deer was more fun because I got to do anything I wanted. I miss it.” He resumed eating his ice cream and kicking his legs back and forth. I became curious.

“Do you wish you were still a deer?”

“Yeah, guess so.” He shrugged, then scratched his nose.

After this, he only really talked about being a deer; he spoke of dewy mornings in the hills and forests, of fog and sunlight and the darkest nights; he spoke of fear, but also the contentment of simply existing on earth, of leaping over tall fences meant to keep him out.

I started researching reincarnation, specifically stories about children who talked about their past lives. I was surprised to find that there were a growing number of accounts. Some people believed them, some didn’t—same story as with everything. I was shocked, however, by the accuracy of some of these accounts. Children describing the intricate details of their life as a Samurai without having previous knowledge of such things. Many of these accounts were posted on personal blogs. Some entire blogs were even dedicated to their children’s stories of their past lives. On Naomi the Elephant Girl, a blog by someone named Adriana L., I asked what she did when her girl started telling her about her past life.

She answered immediately: “We started asking a lot of questions, and above all, we didn’t treat it like a joke. Now I can 100% say that my wife and I believe her.” Reincarnation was not something I had spent much time thinking about before Leif’s stories. For whatever reason, I latched on to it.

A year after Leif was born, I was diagnosed with postpartum depression. My work at my consulting firm took such a hit that I had to step down from my executive role to focus on my recovery. I suppose I always blamed Leif for that—it wouldn’t have happened to a man—in fact, it didn’t happen to Owen; he didn’t have to give up his work in real estate. No, it happened to me. I was angry as I watched my male coworkers with children advance beyond me. At home with Leif, I stared at him for hours and wished he would disappear. Spending money on daycare felt ridiculous, since I was technically able to care for him, but I wished my life could go back to how it was before.

I fought to get back to where I was in my job, but there was something missing in me. Sometimes when I looked at Leif, I got a sense that I could see in him the thing that had gone missing in me. I wanted it back so much sometimes that I had the urge to claw it out of him, but I wouldn’t know where to look. But perhaps deep down I feared that part of myself was not meant to be found in this lifetime.

Igot a call from the school saying Leif had pooped on the playground. I asked them if it looked “deerish.”

“Define ‘deerish,’” they said. I quickly looked up photos of deer poop on my phone.

“You know, like pellets,” I said.

“I’ll ask Diane; she saw it.” A pause. “Diane says, yes, it was deerish poop.” I told them he had digestion issues, which they didn’t seem to care about. They told me to come down right away and get him. Apparently, they drew the line at feces. “And actually, we need to talk about some other incidents that have been happening.”

I sat in the waiting room of the principal’s office and felt that familiar pit of dread in my stomach, as if I were a child, about to be punished for mouthing off to the teacher, again. I was a little punk, I won’t lie. Up until now, I thought Leif was the opposite of me—docile.

The concentrated smell of crayons overwhelmed my senses. The students’ artwork hung along the walls, not an inch of blank space left without a shitty giraffe with three legs, or a dog that just looked like a blob with a rogue eye coming out of one ear. Kids don’t get anatomy; none of these creatures would even be able to walk if they were real. I didn’t get the appeal and decided that kids are pretty bad artists for the most part. A smiling man poked his head out from behind the desk and told me I could go in to see the principal.

“We have a bit of a problem, Ms. Evans.” The principal looked concerned as I sat down in front of her desk. Her office was crowded, stacks of papers and boxes. She wore a pantsuit, but she had dark circles under her eyes.

“And what’s that?”

“Leif has been involved in multiple incidents, and we didn’t think it was serious until today when he used the playground as, well, a toilet.”

“Can I have specifics, please?” In response, the principal took out a file.

“He seems to have no regard for proper social and school rules. For instance, two weeks ago he started eating a classmate’s worksheet in class. A day after that, he was collecting and eating acorns on

the playground, where he got other children to do the same. One classmate actually got sick.” She flipped the page, sighing. “Last week he was telling the teacher he didn’t have to listen to her; then just about every day, I’m told he scratches himself very disruptively and says he has fleas. The teachers tell me he even uses the table and other students as scratching posts, and now this.”

I wasn’t angry, just intrigued. When he got into the car, he looked out the window the whole way home and I wondered what he was thinking.

Back at home, he wanted to go out to the backyard. Our yard is forested, the type of yard I wished I’d had as a kid growing up. It’s unfenced, and the back portion is wild and overgrown and leads into the woods. There was an autumn chill in the air, and spiderwebs were popping up on every corner between every walkway, so that we had to bat them away or stoop under to avoid them. My father told me years ago that you know fall is coming when you start seeing spiderwebs everywhere.

I got a jacket and joined Leif in the backyard. He went straight for the forested section, and I saw him put something into his mouth. Getting closer I saw he was eating acorns and the leafy parts of some plants. I followed him and let him do his thing. Maybe I was a bad mother for letting him eat acorns, but it looked like he knew what he was doing, and there were some plants he avoided entirely. I just wanted to understand him.

“How do you know which ones to eat and which ones not to?”

“My deer mother taught me when I was a baby.”

I started to wonder about what my past life would have been.

“Leif, who do you think I used to be?” At this, he left his foraging with a fist full of green acorns and leaves and walked over to where I was kneeling in the grass and pine needles. He put his free hand on my face and looked into my eyes.

“I think you were someone really sad and lonely, and it was so big that it followed you here.” Jesus, maybe he had been a monk. He stood there, and I put my arms around him and hugged him to my body—needing to feel something living close to me. He rested there only a few seconds before squirming out of my grip and running off into the trees.

No one told me about postpartum depression. I didn’t have anyone to reassure me that I was not broken. I still felt as though I had no one to tell me these things. There was part of me that believed I would never find my missing pieces—that they had been scattered across the globe and nothing short of a Tolkien-like journey could bring them back to me. I was rebuilding, but from what? I had tried all the medications. Nothing helped.

And then there was the part of me that Leif had cracked open, the part that believed I had always been doomed. I felt like something I had done in a past life had karmically cursed me in my subsequent lives. I was at the point where I’d believe anything.

Owen called and said he was driving home. I told him Leif had pooped on the playground and was currently eating acorns.

“You don’t seem mad.”

“Not mad, more curious than anything.”

“Hang in there, we’ll get through to him. Love you.”

“Love you. Hey, Owen—do you think I’m a sad person?”

“Rachel.” He paused. “We’ve always known you weren’t the happy peppy type.” Iswear, when I woke Leif up for breakfast, there was a different essence about his face, a primitiveness that wasn’t there when I put him to bed. I couldn’t explain it.

“Do you have friends at school?” I asked him while he played with blocks in the living room.

“Not really, I just play by myself.” He knocked down the tower he’d built and started cleaning up the rubble.

“Are the other kids mean to you?”

“Sometimes they call me weird. My teacher thinks I’m weird too.”

“Well, I like your type of weird, buddy.” I smiled and ran my hand through his fine hair.

Later, I picked up a picture book about deer at the store. That night after I had given him a bath, Owen and I lay in his bed and read the book to him. It was rare that we did this, lying there as a family. It was rare that I felt good doing this; I felt more like a mother with my son lying against me and reading about the different types of deer and my husband behind us, me leaning against his weight, him encircling us with his bigness. We were a family. Leif laughed at every page. I’d never seen him so engaged with a book before.

“Oh, Mom, look at that. One day, I’ll have points like him.” He pointed to the antlers on the buck on the next page. Owen laughed.

“I wonder if antlers can do this.” As he reached over and tickled Leif’s sides, Leif screamed, put his arms around me, and squeezed tight.

“Save me, Mom!” he yelled. I hugged him back, protecting his body and laying kisses on his head, soaking up the feeling of being a mother.

I smiled at Owen and wished I could relive this moment in all my future lives. I wished that in all my lives there would be love like this—that my son and I would meet as different people in different bodies at different times, and each time we’d learn to love each other better; each time we’d realize our cosmic connection sooner. I hoped that we would recognize each other and that those moments would transcend lifetimes and starve away the sadness within me.

It was midnight when we were awakened by the downstairs door sensor beeping. Owen and I went downstairs to find the back door

wide open and Leif asleep in a heap on the ground wrapped in his blanket. Owen picked him up and carried him back into the house, but Leif woke and started crying, begging to go outside. We stayed with him and read the deer book until he finally fell asleep again. We were all on the couch; Owen and Leif slept, but I was wide awake with Leif stretched across my chest. I moved my hand in circles on his small back, the weight and heat of his body soothing me. The birds had yet to start chirping, and in the quiet of our living room, as I held my son, it occurred to me that maybe we were part of each other, and maybe my missing pieces were not missing after all.

In my research on reincarnation and karma, I learned that the Buddhist life cycle is called Samsara. Life, Death, and Rebirth all connect to the karma you produce from each life. If you live a good life, your karma is good, bad and your karma is bad. Your karma determines what or who you will be reborn as. I thought about my life; my karma was surely bad until this point. Not murderer bad, but I definitely wasn’t Mother Teresa. Karma reminded me of the Catholic teachings I grew up with: Do good so that you will get something good in return. I just didn’t see the purity in doing good just to get into heaven. On the opposite side, maybe humans are so messed up that they need threats to be good people.

I wondered if it was too late to change my karma. Was it already my fate to be miserable in my next life? The thought made me want to give up. I was so tired of being miserable. Was it bad karma to be sad about nothing in particular—to be sad about having too much and feeling like it was all nothing, useless—that I was useless? Could depression get me reborn into a toad? No, that wasn’t it—but I wanted to believe that depression made my life more sacred. To be latched to a burden—to struggle just to live—was my own good deed to the world, to take this weight and bear it myself—to fight to see the light that others didn’t notice. Perhaps this awareness of the dark was what purified me. I lived in the dark so others could thrive in the light.

His ears started changing. They looked bigger than before, ever so slightly curved. His nose was noticeably wider. He seemed happier than he had in a while and spent the entire day outside. When I called for him to come in for his dinner, completely vegetarian now, he came running up.

“Can I sleep outside?” he said.

“No. We sleep in beds.”

“There are beds outside. I like outside. I feel better there. I used to sleep outside. Why can’t I now?”

“Well, now you don’t sleep outside—you have a bed inside.”

He started growing a thin, fawn-colored fuzz on his body. I dressed him in a beanie, long sleeves and long pants. He didn’t want to go to school, but I told him if he was brave, we could go camping over the weekend and he could sleep outside.

I was in a meeting with my new clients when my assistant rang in to say that the school couldn’t find Leif. Even last month I would have been mad at him for messing up my meeting, but I wasn’t mad this time—I was only worried about him. I handed the meeting over to my coworker and rushed to the school to find the police and Owen already there. Apparently after morning recess, he didn’t come back in with the other students. They thought he’d slipped through a gap in the fence.

“I’m so sorry,” said the principal. “The recess teacher on duty had to break up a biting fight, and we think that’s when he ran away. We checked the whole building.”

The officer cleared his throat.

“Most likely he tried to run home, or he’s nearby the school. We’ll have a couple officers looking here and I suggest we go look around your neighborhood and all possible routes to your house.”

He glanced at Owen and me. “We really need to find him before the sun goes down and the temperature drops.”

We looked all afternoon, circling around our neighborhood, calling for him, driving all the routes we took to school. It started to get dark, and I could feel the cold in my lungs, the crisp air like a death sentence. Owen began to break down, and I wanted to as well. We were sitting on the back of the fire truck drinking coffee in Styrofoam cups.

“What if…” he started to say, tears in the corners of his eyes.

“Don’t even think that. We’ll find him.”

It was midnight when we went back to our house, hoping that this time, he would run around the corner into our arms. We couldn’t sleep. The police were searching the city and our neighborhood, and they had posted an officer out front overnight and put out a missing child alert. We’d called everyone we knew to help look, and they were out scouring the neighborhood. I felt like it was wrong of me to take a break, to sit down when my child was still out there. I put on my winter hat, gloves, a warm jacket.

“Where are you going to look?”

“Out back again; he’s been obsessed lately.”

“I’m coming too.” We called his name, tramped through the overgrown brush, the thorny vines capturing our feet, leaves crunching beneath us. We could see our breath in the beams of our flashlights.

It was another hour before we found him huddled under the bushes and brambles in the woods behind our house. He’d wedged himself so deep in the branches, we could barely make out the reflective dinosaur jacket I’d put on him that morning. Owen gently pulled him out from under the bushes. He was breathing—warm even—gangly body, spindly legs, and too-big ears. He was fast asleep, looking like he was sleeping better than he had in months.

As Owen laid out the cushions from the patio furniture in the grass and took some blankets from the couch, I made sure the police and everyone else knew that we’d found him. We settled down on the makeshift bed and put Leif between us. Owen took my hand across our son’s small body, and our gaze met over the rise and fall of his fawn-spotted coat. Leif turned and nuzzled close to me. I rested my head on his, breathing in his soft wild smell. I held my family in my arms, knowing I was not strong enough to keep them, and closed my eyes to all the noises of the animals at night.

Oh! ye whose dead lay buried beneath the green grass; who standing among flowers can say—here, here lies my beloved; ye know not the desolation that broods in bosoms like these.

—Herman Melville, Moby-Dick

t was a late spring morning when I set out driving to the small unnamed creek in southeast Alabama where Kyle Clinkscales had been found. I wanted to decide for myself what seemed more likely: that he’d crashed his car and died, or, as most people in the area believed, had been killed and put there. The creek was in Chambers County, about a fivehour drive from my home near Nashville. Back in December of 2021, someone had spotted the hatchback of his 1974 Pinto Roundabout sticking above the muddy water and reported it to the police. Later that day, after removing the car from the creek, police found human remains inside, along with Clinkscales’s ID. He’d been missing for forty-five years.

There hadn’t been any updates since the discovery. My route to the creek was similar to the one I would’ve taken to visit my father: south on I-65, east on I-20, exit onto Highway 431 through the Talladega National Forest. My father still lives in the same place where I grew up—an unincorporated community in east Alabama called Delta. Now I’m forty-two, though, and I don’t visit as often as I once did. After leaving the National Forest, I watched the passing scenery, once so familiar, with an outsider’s gaze. A junkyard. A lonesome gas station. Kudzu. I’d just moved back to Nashville after living three years in London and wondered how these scenes would strike the friends I’d made there.

Around noon I pulled off the side of the road to take a picture of the Dixie General Store, which sells Confederate flags and MAGA memorabilia and so on, and sent it to a friend who shares my loathing of such things. I was in too much of a hurry to stop at the Haunted Chickenhouse, with its display of stacked and overturned antique hearses, then came within ten minutes of my father’s house but kept heading south, then crossed the Tallapoosa River—the same river where my mother had crashed and died when I was fourteen.

It was because of my mother’s death that I was so drawn to the Clinkscales case. She’d become a missing person back in 1994 and stayed missing for two years. During that time I never once stopped believing she was alive and would one day return home or be found. But then, late summer of 1996, a scuba diver who was inspecting the supports at Foster Bridge came across her car. Some of her remains were inside. The rest had washed out into the Tallapoosa.

South of LaFayette the dirt roads and embankments become a garish red, heavy with oxidized iron. The sight of red dirt always makes me melancholy. I spent the first fifteen years of my life in the Piedmont region of the state and have always thought of it as a transition zone from the mountains to the coastal plains, a place people drive through without noticing much except poverty and red dirt.

It was mid-afternoon when I passed Cusseta without realizing it. I met several logging trucks loaded with timber, then saw the sprawling cutover where the logs were coming from. Past the cutover, I crossed a small bridge over a muddy creek. A couple of miles later, when I reached Interstate 85, it hit me: that must have been the creek. I’d looked at it on Google Earth. I knew the creek was small, but this one hadn’t seemed anywhere near big enough to conceal a car for forty-five years.

I turned around and headed back. The prospect of seeing the spot where a kid had vanished made me feel a little sick. It reminded me of the agony of not knowing where someone you love has gone and why they won’t come back.

One June afternoon in 1994, my mother told my father and me she was going to the Piggly Wiggly about six miles away in Lineville. I had just turned fourteen. When the store closed at nine o’clock that night, she still hadn’t returned. Around an hour later, my father and I went looking for her. When we returned home, we called the hospital, then the police, then every other person we could think of.

A county investigator visited early the next morning to tell us that my mother had been scheduled the day before to come in for an interview about some money that had disappeared from a neighbor’s trailer. My father had no idea about this. The investigator told us he believed my mother was now hiding to avoid prosecution for this theft.

During the next two years I believed all kinds of stories about my mother—stories that served to explain how the mother I thought I knew could leave me and stay hidden without even letting me know she was okay. I believed the police when they said that she would eventually get tired of hiding and come home, that she was probably staying in California with some distant relatives, that one day somebody would spot her and pick up the phone, or a police officer would pull her over and run her tag, or someone would crack and tell us where she was. Then, when she was found dead, I didn’t know what to believe. Mostly I just went numb.

Fast-forward twenty-four years: I was doing my best to homeschool my two daughters through the first London lockdown and sneaking lots of quick YouTube breaks to decompress, when a video about scuba divers finding a car popped up in my suggestion list. I clicked it. The algorithms took notice. Over the next few months, I watched dozens of similar videos about scuba divers finding people who’d been missing for years, sometimes decades. Apparently, using scuba gear and high-end sonar technology to search for missing people underwater had become a hobby of sorts, and some of its devotees had their own YouTube channels. I’d never known that so many cars were scattered throughout America’s waterways—creeks, rivers, reservoirs, even retention ponds—with so many unmourned bodies inside them. I found it a little comforting to learn that what had happened to my family wasn’t as rare as I’d always thought.

By the summer of 2021, when I moved back to the Nashville area, I’d grown bored watching these videos, but some of them still appeared in my suggestions. In December, when the video about Kyle Clinkscales appeared, I only clicked it because he was from LaGrange, where my father and I had often gone fishing at West Point Lake, and because the creek where he’d been found was only an hour south of Foster Bridge, where my mother had died.

Kyle Clinkscales had last been seen on January 27, 1976, at the Moose Club in LaGrange, Georgia, where he worked part-time as a bartender when he wasn’t attending classes at Auburn University. When his shift ended at 11 P.M., he left, supposedly heading back to his apartment in Auburn, about forty miles away. His parents were expecting to see him again on Friday, but they didn’t think too much of it when he didn’t arrive. They figured he’d gotten tickets to a basketball game in Gainesville he’d mentioned wanting to watch. But by Tuesday they’d grown worried enough to notify the police.

Forty-five years, ten months, and twelve days after he left the Moose Club, Kyle Clinkscales’s remains were found. Maybe the water level in the creek had lowered over the years. Or maybe the metal latch on the hatchback had rusted and finally gave way, allowing the hatchback to pop open and rise above the water. The people who needed to know most that Kyle had been found—his parents—were both dead. His father John had died of a heart attack in 2007. His mother Louise had died in January of 2021, less than one year before her son was finally found.

After watching a couple of news stories about the case and reading every article I could find online, I dialed up my father. “It’s just a little creek,” I said. “I don’t even think it has a name.”

“Oh well.”

“Forty-five years. Can you imagine?”

“I don’t guess.” My father has a few short stock responses he rotates through when people talk to him. The phrases themselves mean little; it’s his tone that conveys his meaning. That day on the phone, his tone told me he was as intrigued by the case as I was.

“They both died without knowing,” I said. It was this detail that had most drawn me to the story.

“All-rightie then,” he said.

We talked about it awhile longer and then hung up without mentioning my mother once. I rarely mentioned my mother to him. It made me uncomfortable to say “Mommy,” which is what I’d still called her when she disappeared. And to say “my mother” felt like I was telling a stranger about her. So I just told him about Kyle Clinkscales, confident he knew what I wanted to convey: that, as bad as it had been for us, it could’ve been so much worse.

On the way back to the creek, I pulled into the empty gravel parking lot of a country restaurant called The Front Porch to see if anyone could confirm it was indeed the spot where Clinkscales’s car had been found. As I climbed the steps to the porch, I noticed the antique plates someone had placed in the flowerbeds as decoration. Some of the plates were broken. Inside I found two middle-aged women prepping for the evening shift. Before asking them any questions about Clinkscales, I complimented their restaurant. I was sincere, too. I’ve always liked the kind of family restaurant you sometimes find miles from the nearest town.

Then I told them that my mother had been a missing person back in the ’90s and that I was interested in writing a story about the disappearance of Kyle Clinkscales, though I made sure to add I wasn’t “from the media.”

“Who?” one woman said.

“The kid they found in that creek,” the other said.

“Ohhhhh. Yeah.”

“I’m trying to find the creek where they found him,” I said.

The two women discussed it for a while until one of them decided to call a man who lived nearby. “He knows all about it.” While we waited, we chatted. One woman said that after the car was found, “everybody on Facebook was talking about it. People were saying they’d seen the car before but just thought someone had dumped it there.”

I asked whether someone going from LaGrange to Auburn would drive this way.

“No,” the other woman said.

“Well,” the first said, “it depends on what part of Auburn they was headed to.”

“What if someone wanted to avoid main roads?” I said. “Like somebody who’d maybe been drinking?”

“Maybe.”

I wanted it to be so. I’d driven to Cusseta hoping to convince myself

that Kyle’s death was accidental. I didn’t want to believe the rumor that most people in the area, even the authorities involved with the case, seemed to hold as fact: that Ray Hyde, a local man known to meddle in stolen cars and drugs, had killed him.

In Kyle’s Story: Friday Never Came—a long-out-of-print volume published in 1981—Kyle’s father John Clinkscales tells the story of the few years after his son went missing. It’s not so much a memoir as something akin to self-help—a guide of sorts for people whose loved ones have disappeared. It opens with a series of case studies. For a second while reading it I got nervous: What if he mentions my mother? I was relieved to remember the book had been written over a decade before she died.

Finally, about halfway through the book, Clinkscales gets around to a detailed chronology of Kyle’s story. John and his wife Louise did many of the same things my father and I had done after my mother disappeared. They handed out Missing Person flyers. Begged newspapers and TV networks to talk about the case. Chased down leads, no matter how absurd. Researched religious cults. Invented stories to explain why Kyle might’ve wanted to disappear.

At first, according to the book, John Clinkscales “thought the odds to be about nine to one” that Kyle was alive, even though his son had never struck him as the sort to just up and run off. As the weeks passed, his confidence actually grew: “I felt that if something had happened to him, the fact would soon surface. Each day that went by was an indication that nothing had happened.”

Yet the years wore John Clinkscales down. By the time he got around to writing his book, he felt there was “no more than a fifty-fifty chance” of ever seeing his son alive. And apparently this percentage continued to drop. In his obituary it is written that he was “preceded in death by his son.”

I wonder, if my mother were still missing to this day, would I have given up hope like John Clinkscales had? Would the stories I told myself have continued to evolve in her absence? Would they have

turned darker, serving to suppress hope rather than bolster it? During the next two years I I think so. I’m glad I didn’t have the chance to find out. believed all kinds of stories about John and Louise Clinkscales both died convinced that Ray Hyde had my mother—stories that served murdered their son. Hyde had been a member of the Moose Club where Kyle tended bar. Maybe Kyle to explain how the mother I had seen or heard something at the Moose Club—a drug deal in the parking lot, or some loose talk about hot thought I knew could leave me cars—that Ray Hyde didn’t want him to know about. and stay hidden without even The January 27, 1996, edition of the LaGrange Daily News reads, “Just recently, Sheriff Donny Turner and his letting me know she was okay. investigators received information that Kyle was killed the night he disappeared from the Moose Club and his body was dumped in a hole behind a county home. His car was reportedly pushed into a lake in the southeast part of the county.” A judge signed a warrant for investigators to search Ray Hyde’s junkyard and drain a nearby pond. They found nothing, but still arrested Hyde for possession of a firearm as a felon. Later, Hyde told a reporter that, if he needed to get rid of a body, he wouldn’t dump it in a pond less than a mile from his house. “I’d dump it off the Georgia coast, weighted down with a couple of electrical transformers where the sharks could eat it.” When he died in 2001, most of the county assumed he’d gotten away with Kyle’s murder. Four years following Hyde’s death, a man phoned the Clinkscales residence and said he knew what had happened to their son. When he was seven, he said, he watched two men put Kyle in a lake. Kyle’s body had been stuffed into a fifty-five-gallon drum and covered with concrete. When investigators drained the lake, they found no human remains, but they did find an indention that could have once held a barrel. Based on other information from this caller, police arrested Jimmy Earl Jones and charged him with several crimes, including concealing a murder. Jones pled guilty to the lesser of the charges: giving false statements. His testimony in court would turn out to be the closest thing to an answer the Clinkscales would get. According to Jones, after leaving the Moose Club, Kyle stopped by Hyde’s place to drop off some money he owed. Jones, who claims he was present at Hyde’s, said he “heard two shots, and I—when I turned around, I was in shock. And we carried him and put him in the shop.” Later Hyde told Jones that he’d put Kyle in the lake but that he’d eventually gone back and moved him to a place where he thought no one would ever find him.

I’d been standing in The Front Porch for about ten minutes, talking to the two women who worked there, when the man they’d called on the phone—who supposedly knew insider details of the Clinkscales case—finally walked in. The restaurant interior was dark and cool, and when the man opened the door I felt a rush of afternoon heat. He closed the door behind him and gave me a quick look and a nod.

He didn’t smile or make any friendly gestures. One of the women told him I was looking for “the creek where that boy was found.”

“What boy?” he said.

“You know—story of the month.”

“Oh.” He looked me over again in a way that seemed subtly disapproving. I was wearing a Penguin shirt and tapered pants and bright-colored sneakers—probably unusual attire for a white man in Chambers County, Alabama. He was wearing jeans and low-top boots. “It’s about a mile up the road,” he said. “If you hit the railroad tracks you went too far.”

I asked him which side of the road the car had been found on.

“The right side,” he said. He pointed north and said, “Going thataway.”

“I’m trying to figure out,” I said, “if the kid was driving from LaGrange to Auburn, how would the car have gone into the creek?”

“It didn’t go into the creek at all.”

I thought about what he’d said. “Oh. You mean someone put him there.”

“Yup.”

“What makes you think someone killed him?” I asked the man, hoping I didn’t sound confrontational.

“I don’t think,” he said. “I know it. Everybody knows.”

“But—” I said. I hate it when people think they know things they really don’t. I’m not sure if the South has a disproportionate number of such people. I just know that, growing up, I was surrounded by them. “How do you know?” I said, making sure to put emphasis on the how and not the you.

“I was in law enforcement. I got contacts. They know what happened.”

I find nothing less persuasive than the I-got-a-buddy-who-told-me argument. I tried to imagine it: retrieving the barrel from the pond, separating the decomposing remains from the concrete, placing the remains back in the car, hauling the car thirty miles to a creek across the state line (presumably in the middle of the night), lifting the bed of the rollback so the Pinto rolled off the bridge and landed in just the right position for it to disappear for forty-five years.

“You know, my mother disappeared back when I was fourteen,” I said (the man’s eyes widened), “and the police told me and my father she’d stolen some money from a neighbor and then ran off to avoid getting in trouble for it. I mean, they acted like they knew it, too. But they were wrong. She was finally found in the river where she’d just crashed. She’d been dead the entire time.”

It felt damn good to see in the man’s face that I’d made him second-guess himself.

Of course, I hadn’t been entirely honest when I told the man my mother had just crashed. It’s possible she drove herself into the river on purpose.

For two years, my father and I thought she was avoiding prosecution for theft. We even came to believe she was hiding in California. The details that led us to believe this are too numerous and convoluted to list here. They were enough to convince a grand jury to indict her for felony flight, though. Yet the instant my father learned of her death, he let go of all the stories. She’d died in a car crash. Simple. Happens all the time. Take a long drive through the rural South and count the crosses. The evidence of my mother’s guilt was all “circumstantial,” as my father puts it, “and after the fact.”

My mother’s death certificate showed less certainty. It lists the date of her death as August 26, 1996, but following the typed date, the medical examiner wrote in the word found. A bureaucratic anomaly: the d in the word spills over into the next prompt. There wasn’t enough space on the form to say all that needed saying.

There are no forms or files to account for how bad one person’s luck can run—how, of all the places, she crashed in a river, her car flipping upside down as it settled in the shadow of the bridge, shielding the white paint from the sun’s revealing rays. There are no forms stating whether she stole the money or not, or why she was driving across Foster Bridge at all. She’d told us she was going to the Piggly Wiggly; the police told us she was supposed to be coming to see them. Foster Bridge isn’t on the route to either place. Prompt 49 on the certificate asks for the manner of death. The answer: Undetermined Circumstances.

Ileft the restaurant and pulled off the side of Chambers County Road 83 right before the bridge. There wasn’t a house in sight. The sun was just beginning to drift low, but not low enough to cool the day. I stepped away from the road and cringed as a pulpwood truck roared past. Did the driver wonder why I’d stopped? Did he know what had been found in this creek? The asphalt emanated tendrils of heat. The forest beside the road was thick and raucous with insects, birds, squirrels. As I crossed the bridge, I gazed down at the yellow water where the Pinto had been submerged. The creek seemed hardly wide enough to hold a car. I went to the place where, based on photos, the Pinto had been pulled out. In these photos, the front of the car is pointing south—the direction Kyle would’ve been driving if he’d decided, for whatever reason, to take this back road to Auburn. Then again, if the winch had been hooked to the bumper, the car would have ended up pointing this direction regardless of its position in the water. I thought back to how certain the man in the restaurant had seemed. God, I wanted him to be wrong.

The creek flowed over a flat concrete spillway and fell a few inches into an almost stagnant pool. The water was far too murky to see through. All that hideous red dirt probably kept it stained. Above the bridge the creek was small, and below the pool it narrowed again, but here it widened and seemed deep. It was an unusual feature. I

thought about probing it with a branch to determine its depth but decided against it.

I’d stood below the bridge where my mother died, too, and talked to my father about whether she might’ve committed suicide. He says she didn’t, of course, and I don’t try to persuade him. If anything, I want him to convince me. I tell myself it shouldn’t matter how someone dies, only that they’re dead. I tell myself I’m strong enough to accept the unknowable. But these are lies.

Another pulpwood truck thundered over the bridge, its wind ruffling the leaves. I’d driven five hours to look at this creek. Now what? I pulled out my phone and took a picture, thinking, It sure is an ugly damn creek. A horrible place to disappear.

I walked back to my car and took another picture of the bridge. Then I climbed in and turned the ignition and plugged in my phone. As I headed north, the lecture I’d been listening to automatically picked up where I’d left off. It was Alan Watts, the popular ’60s philosopher, sharing the insights of Zen Buddhism with a crowd of California hippies. The title of the talk: “Not What Should Be.”

After visiting the bridge in Cusseta, I headed toward Delta to stay the night in my old bedroom. My father and I were planning to go fishing the following morning. On the way, I stopped at a grocery store and bought some ribeyes, charcoal, and beer. Then I ignored Google Maps and took a slightly longer route to Delta: County Road 82, which crosses Foster Bridge.

There used to be a cross here, but it rotted away and my father hadn’t replaced it. The water was almost the same green as the steep hills lining the river—a much prettier spot than Kyle Clinkscales’s creek. Two and a half decades earlier, when the Alabama Marine Police and Sheriff’s Department had winched my mother’s car from the river, soda cans and shreds of upholstery poured from the shattered windshield. At one point, the men standing at the bridge’s edge looked down to watch a white tennis shoe bob atop the ripples and begin drifting slowly south.

An image in the August 29, 1996, edition of the Clay Times-Journal shows the car still half-submerged, the back bumper connected to a steel cable. Two men on a boat observe the progress. The man who discovered the car is wearing his diving gear. He stands on the bow, balancing himself with one hand on a pylon. Overhead I count nine faces peering down from the railing. In another photo, titled, Almost Over the Top, the car’s front tires have gotten hung on the bottom of the bridge. The weight has lifted the wrecker onto its rear wheels. The men seem ill-suited for the task. They are improvising, at risk of fouling everything up.

“The small flock of ducks in the foreground,” reads the caption beneath a third photo, “is oblivious to the tragic scene unfolding behind them.” Over a decade later, in a workshop at Ohio State, I would write a short story about a murderer who uses a rollback to drop his victim’s car from a bridge. When he looks down from the bridge railing, he notices a couple of ducks floating cheerfully past. When I wrote this scene, I wasn’t consciously thinking of my mother. I’d forgotten all about the newspaper photo with the ducks. I just thought it was a cool image—something innocent to contrast the sinister man on the bridge. I kept driving toward Delta without stopping at the bridge. I didn’t even know for sure why I’d decided to come this way. Some people visit cemeteries. Once every few years I drive across Foster Bridge.

Ifound my father seated on his front porch. He lit a cigarette as I pulled into the red clay driveway. As soon as I climbed out, I saw some of the broken arrowheads I’d started dropping in the driveway back during college once I’d gotten tired of collecting them in boxes. I stooped down to examine a few of them. I liked noticing how, over the years, they moved from place to place. I guess it was the wind and rain that moved them.

I set my bags on the edge of the porch and took a Miller Lite from the box. “Hand me one of those,” said my father.

It was late enough now that we could sit outside without sweating. I drank and looked around at the yard. The woods came right up to the house. He’d recently cut a few trees that had gotten so large they would’ve destroyed the house had they fallen.

“Well,” I said, “I hate to say it, but I think somebody put that car there.”

He sounded disappointed when he said, “You think somebody killed him?” I was surprised he hadn’t used one of his stock responses.

I told him the whole story of Ray Hyde, of the man who’d called the Clinkscaleses in 2005 claiming he knew what had happened, and of Jimmy Earl Jones, who’d spent several years in jail for lying to police. I’d already told him most of these details over the phone, but now I was all but convinced of their veracity. “I don’t know, just looking at this creek—it’s a hole—it looks deep. Deep enough to hold some big catfish.” I pulled up the picture of the creek on my phone and handed it to him. “It’s the kind of place a person might know about, especially if they like to fish. I’m just thinking, if the man wanted to hide a car, it’s almost an ideal spot. You’d never think to look there.”

“But how’d he get the car there?”

“He had a rollback.”

“Oh.”

I walked over to my father’s bass boat and opened the rod locker and took out a few reels that needed new line. The rod handles had mildewed, so I went to my car and grabbed some disinfectant wipes and returned to my beer on the porch to clean them.

“But—” said my father. “It still don’t make sense. You’re telling me, this man—he killed this kid, buried him in the bottom of a pond, then went back and dug him out and hauled his car off to this creek and dumped it. Can you imagine someone doing something like that? ’Cause I can’t.”

“I can’t imagine killing someone over money in the first place,” I said. “So it’s irrelevant whether I can imagine doing all that other stuff.”

“I mean, this creek isn’t big enough to hide a car. You’d have to set everything up just right to dump a car there and have it disappear.”

“But that’s exactly what happened, whether someone did it on purpose or not. It went into that creek and stayed disappeared for forty-five years.”

At the sound of a carpenter bee, he jumped up and grabbed a tennis racket. The bee escaped before he had a chance to swing. He sat back down and said, “I bet I’ve killed a hundred of them things this year.” He wasn’t being cruel. They were burrowing into the rafters. “Still,” he said, “there’s West Point Lake right there outside LaGrange. The man could’ve rolled the car off a boat ramp. I don’t buy it. The kid just crashed and everybody made up a story to explain why they couldn’t find him.”

That’s when it hit me: We were having the same disagreement about Kyle Clinkscales that we’d had dozens of times about my mother. And just like in those previous conversations, I was rooting for him to be right, even as I found his version of events just short of persuasive.

Several weeks after I’d made the drive to the bridge where Kyle had been found, I decided I could no longer put off calling Sheriff James Woodruff of Troup County, Georgia. He hadn’t been directly involved with the investigation of Ray Hyde or Jimmy Earl Jones. But he was the man in charge now. I’d been putting off the call out of fear, I guess—a habitual fear of talking to cops. I worried he’d be rude to me, or tell me something I didn’t want to hear, such as that they’d found a bullet hole in a fragment of skull.

But he was friendly as could be—much friendlier than the “expert” I’d met in that Cusseta restaurant. He started out by asking about my mother. I’d mentioned in an email what had happened to her so he wouldn’t think I was just some busy-body looking for good gossip. I also told him I’d been to West Point Lake many times with my father. (We’d competed there in the West Georgia Bass Club.) He said he’d just recently been talking to someone about West Point Lake, saying how so many people would travel to their county to enjoy a body of water that the people who lived there just took for granted. Probably ten minutes passed before we got around to talking about Kyle Clinkscales.

I hadn’t expected the sheriff to tell me much I didn’t already know. I’d assumed he would say he couldn’t comment on an ongoing investigation. I was wrong again. He told me they’d found bones in the car but that they were waiting on a lab in Atlanta to return the DNA test results. He doubted whether they’d ever determine a cause of death. Then, even though I hadn’t yet asked about it, he told me some people do use this route to go to Auburn, even if it’s not the most obvious course. “So,” he said, “there’s that possibility.”

“You mean it’s possible he just crashed there?”

He said he didn’t see why someone who’d killed and hidden him and gotten away with it for so long would then take the risk of digging him back up and moving him. “I think that would be stupid. If you got something hid so well, digging it up would not be a smart move.”

I once learned in a magazine-writing course that, while conducting an interview, it’s best to use silence to your advantage. Let it linger. Perhaps the pressure of it will push your subject to reveal something. But on the phone with the sheriff, I just couldn’t wait to get to the question that mattered most—a question my father had specifically told me to ask: “Was the car in drive or neutral?”

I heard someone talking in the background and realized the sheriff had me on speaker phone. The sheriff said something, but I wasn’t sure if it was directed at me or at this other voice. After a few seconds of silence, I said, “I’m sorry, I couldn’t quite hear what you said.”

“It was in fourth gear,” he said. “Ignition was on.”

A few minutes later we hung up. Immediately I called my father.

“Can you hear me?” he said.

“Yeah.”

“I’m driving and got you on Bluetooth so I got to shout at the roof.”

I told him Kyle Clinkscales’s car was in fourth gear.

“All-rightie then,” he said with a tone of relief and maybe a little satisfaction. “Going highway speed on a back road.”