SEXUAL HEALTH AND EMPOWERMENT [SHE]

SEXUAL HEALTH AND EMPOWERMENT [SHE]

SHE is undertaken with the financial support of the Government of Canada provided through Global Affairs Canada

Sexual Health and Empowerment (SHE) Final Report

Implementer: Oxfam Canada

November 2024

Contact: Kimberly Quach, Program Officer kimberly.quach@oxfam.org

Cover: An Oxfam Pilipinas staff member walking in Brgy Bulawan, Prieto-Diaz, Sorsogon during one of the SHE Project’s community visits. Oxfam Pilipinas has partnered with the Mayon Integrated Development and Alternative Services (MIDAS) to reach communities in the Bicol Region. (credit: Neal Igan Roxas)

Oxfam Canada

39 McArthur Avenue, Ottawa, ON K1L 8L7

1-800-466-9326

www.oxfam.ca

oxfamcanada

SHE is funded by the Government of Canada through Global Affairs Canada

First and foremost, we extend our heartfelt gratitude to Oxfam Canada for placing their trust in Progress Inc. to conduct this evaluation.

A special thank you goes to Pushpita and Kimberly for their unwavering support throughout all phases of the evaluation. We would also like to thank Oxfam Philippines, Jhpiego, and all associated team members (especially Michelle and Jeremiah) for their continuous support and guidance, which contributed to the smooth execution of the evaluation. Your coordination efforts and the information you shared were instrumental in shaping this evaluation. The weekly meetings with you provided invaluable guidance and illuminated our path at every turn.

We extend a sincere thank you to all participants, including those from CSO partners, WROs, and CSOs (both under Pillar 1 and Pillar 2), for their willingness to engage in conversations and share their invaluable insights. We are also grateful to all survey and interview participants, as well as those who took part in discussions. Your cooperation has been indispensable in documenting the findings and gaining a deeper understanding of the project.

We also wish to express our appreciation to the field researchers from all regions for their unwavering commitment to delivering quality work within a tight timeframe. Your dedication has been instrumental in the success of this evaluation.

A special thank you to Maya and Pia for coordinating all the work smoothly throughout; your hard work has not gone unnoticed. We also thank Dr. Joselito for your continuous check-ins and support in advocating for sustainability. Your attention to detail in data comparison was very helpful. Lastly, thank you to Sue for providing an SRHR and gender perspective, which prompted us to explore new ways forward and delve deeper into the issues.

Pooja Koirala Founder/Director Progress Inc.

August, 2024

Progress Inc. prepared this report for Oxfam Canada as part of the external evaluation of the SHE project. A combination of quantitative and qualitative data collection methods was employed to derive the findings. Primary data collection for this evaluation took place in June, July, and August 2024. The viewpoints presented in the evaluation reflect those of the evaluation team.

For any inquiries regarding the evaluation, please feel free to contact Progress Inc. using the information below:

Pooja Koirala (Author)

Email: poojak@progressinccompany.com contact@progressinccompany.com

Team Members:

Pooja Koirala – Team Leader

Sue Newport - SRHR Expert (Consultant)

Dr. Joselito Vital - SRHR Expert (Consultant)

Maya Vicencio – Field Coordinator (Consultant)

This report presents an evaluation of the Sexual Health and Empowerment (SHE) project, a seven-year initiative funded by Global Affairs Canada (GAC) in partnership with Oxfam Canada (OCA), Oxfam Pilipinas(OPH), Jhpiego, and eleven local women’s rights organizations (WROs) and civil society organizations (CSOs) in the Philippines. The project aims to empower women and girls in six disadvantaged and conflict-affected regions of the country to secure their Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights (SRHR).

The evaluation focuses on the following objectives:

• Assess whether the project has met its targets as outlined in the Performance Measurement Framework (PMF).

• Evaluate the validity of the project’s assumptions based on its Theory of Change, considering contextual shifts and the project’s adaptability over time.

• Identify challenges or limitations in the project’s theory of change and programming, and propose improvements for future SRHR programs in the Philippines.

• Highlight lessons learned and best practices in SRHR from project partners.

• Facilitate cross-organizational exchange of experiences and learnings.

The evaluation employed a mixed-methods approach, combining both qualitative and quantitative techniques, guided by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development- Development Assistance Committee (OECD/DAC) criteria. A concurrent embedded design was used, with qualitative methods as the primary focus and quantitative data supporting these findings. The evaluation was both summative—assessing the achievement of project objectives—and formative, identifying lessons learned and the effectiveness of strategies. Key areas assessed included relevance, efficiency, effectiveness, impact, and sustainability., with an outcome harvesting method used to trace achievements and causal pathways.

The evaluation covered six regions in the Philippines: Bicol, Eastern Visayas, BARMM, Zamboanga Peninsula, Northern Mindanao, and Caraga. The sample included 13 of the 21 municipalities supported by the project. A total of 52 barangays were selected using stratified sampling.

A comprehensive review of baseline, midterm, and pulse survey data was conducted, alongside an analysis of annual reports, learning documents, and outcome harvesting reports. For the quantitative survey, a sample size of 1710 was reached, including boys and girls (aged 15-20) and women and men (aged 20-50). 60 Focus Group Discussions (FGDs_ were held with diverse groups, including adult women, men, adolescents, peer educators, and Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, asexual plus (LGBTQIA+) participants. Moreover, 53 Key Informant Interviews (KIIs) and 8 In-Depth Interviews (IDIs) were conducted with stakeholders, including Rural Health Units (RHU) representatives, Women Right Organizations (WROs), Local Government Units (LGUs), and project partners, to assess the availability, accessibility, and effectiveness of Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights (SRHR) services.

The project was structured around two major pillars, with the first pillar focused on engaging rights holders, community members, and healthcare practitioners to support gender-responsive and youth-friendly sexual and reproductive health information and services. The evaluation revealed improvements across all outcomelevel indicators envisioned by the project, particularly in addressing the unmet need for Family Planning (FP).

The unmet need for FP among women decreased from 32.2% at baseline to 22% at the endline, and among girls, it dropped from 13.3% to 4%. The target was set at 25% for women and 4% for girls, indicating the target being achieved. Qualitative findings suggest that the decrease in unmet FP needs can be attributed to the project’s support in demand creation through outreach and awareness initiatives, as well as the strengthening of supply-side parameters by enhancing human resource capacity.

Another positive outcome was a reduction in the teenage pregnancy rate. The total count of teenage pregnancies decreased from 2,281 in 2020 to 1,598 in 2023. The average teenage pregnancy rate (10-19 years) across all project sites in 2023 was 18.51 reported by the Field Health Service Information System (FHSIS) data from 2023 This is a reduction of 5.92 from 2022. However, the 2023 TPR appears to be higher by 8.67 compared to 2019 due to differences in the source of projected teenage population (TPR denominator) across the years. A proxy indicator used during the survey showed that only 2.9% of teenagers reported being pregnant at the time of the endline survey compared to the target of 3.2%. This is a notable decline from the 7.4% reported at baseline. Enhanced awareness among adolescents about the negative implications of teenage pregnancy, including its consequences on mental and physical health, is one of the factors that led to the decrease. This improvement is largely due to the awareness sessions conducted at the community and school levels.

The project also sought to assess the community’s perception of SRHR. This was measured using composite indexes of reproductive autonomy, sexual autonomy, and economic autonomy. The endline results indicated improvements: 68% of girls, 62% of women, 62% of boys, and 63% of men demonstrated positive attitudes toward SRHR, compared to 48% of girls, 50% of women, 47% of boys, and 46% of men at baseline. This indicator has also met the target that was set at 57% for girls, 60% for women, 58% for boys and 60% for men. The project has effectively fostered attitudinal change within the community. Through awareness sessions and dialogues, it has worked to shift gender dynamics by emphasizing the importance of equality and shared household responsibilities. As a result, women and girls have gained confidence in their bodies and decisions, leading to a shift in overall perceptions. The project’s engagement of men, boys, women, and girls is commendable and has been pivotal in changing attitudes.

At the intermediate outcome level, there was an increase in new FP acceptors by the end of the project, with 24,787 new acceptors reported over the period between 2019-2024. The project surpassed its Year 6 endline target of 5,209 by 31%, reaching 6,824. A survey proxy indicator showed a decline in FP usage from baseline to endline: girls (87% to 79%), women (68% to 65%), boys (40% to 32%), and men (69% to 32%). Both FHISIS and survey data report showed mixed trends in FP acceptors. BARMM and Sta. Margarita in Region 8 saw increases due to PSI services and outreach, while declines occurred in Ganassi, Mobo, and Region 9 due to low FP prioritization, limited training, and stockouts. Region 10 had mixed results, with Ozamiz excelling from PSI training, and Region 13 declined after reaching its target population.

The number of women accessing quality and genderresponsive reproductive health services reached 65,994 by Year 5, surpassing the target of 62,342 by approximately 5.9%. However, the number of men who accessed these services, 2,266, was below the target of 2,509 by about 9.7%. Modern contraceptives like oral pills (36%-38%), injectables (20%-24%), and PSI (17%) remained most popular, while permanent methods had low uptake, limited to medical missions. COVID-19 efforts, including PSI distribution and provider training, boosted usage.

Immediate outcomes also showed a progress. The survey data revealed that 87.9% of the targeted population knew where to access SRHR services, including contraceptive commodities, an improvement from the baseline. Specifically, 87.8% of girls, 93.8% of women, 81.6% of boys, and 87.7% of men were aware of where to access these services, compared to targets of 54.3% for girls, 77.4% for women, 64.1% for boys and 81.5% for men. Furthermore, the percentage of females able to make reproductive health choices independently increased to 68.5% at the endline, with 60.7% of girls and 75.2% of women reporting autonomy in their reproductive health decisions, a significant rise from the baseline, and exceeding the target set at 43.1% for girls and 66.7% for women.

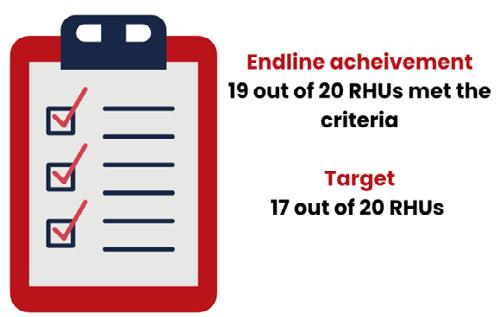

The perception of reproductive autonomy also improved, with the overall reproductive autonomy index at endline reaching 72%, with women at 71%, girls at 78%, men at 68%, and boys at 71%, all showing marked improvements from baseline levels. The targets set has also been achieved. Public declarations and actions in support of SRHR exceeded expectations, with 75 declarations made against a target of 42. Additionally, all 19 RHUs met the 80% benchmark for providing gender-responsive SRHR services as of March 2024.

Lastly, the availability of modern contraceptives in RHUs fell a little short of expectations, with 16 RHUs having at least three modern contraceptives available on the day of the visit, opposed to target set at 17.

Pillar 2 of the project was dedicated to building knowledge and strengthening the capacity of WROs, institutions, and alliances to influence and advance the full implementation of SRHR-related laws, policies, and programs. By the end of the reporting period, there were 21 documented cases of inter-agency collaborations, meeting the target of 21, which is expected to be increased until Year 7 quarter 2 (end of activities). One key indicator measured the autonomy and awareness of organizations in their performance. According to the CAT4ARHR data reported in the PMF at the endline, all 10 partners and WROs expressed confidence in their ability to deliver effective programs on SRHR and GBV prevention, meeting the target of 10. In terms of partners and WROs being on track with their action plans to increase capacity, the target of 10 was also achieved by the endline as all 10 SHE implementing partners received grants to implement their institutional strengthening action plans, with all showing significant progress in completing their planned activities. Additionally, regarding the development of learning agendas, 18 learning agendas were created by the end of the project, representing an 180% accomplishment of the indicator. Another important indicator measured the capacity of WROs and networks to engage the public and policymakers in advocacy and influencing campaigns. The PMF reported a total of 47 advocacy and public engagement activities conducted, significantly surpassing the target of 10. Lastly, the indicator on WROs and networks reporting improved influencing skills showed that all organizations reported to have improved their influencing skills, exceeding the target was set at 20.

The evaluation highlights the project’s success in transforming attitudes, increasing knowledge, and boosting demand for FP services through community outreach, Usapan sessions, and school engagement. Key achievements include a significant reduction in unmet FP needs among both girls and women, attributed to peer educators, school sensitization, and improved service provision. The project has also contributed to a decrease in teenage pregnancy rates and a positive shift in attitudes toward SRHR. Notable outcomes include enhanced reproductive autonomy among women and girls, a shift in community attitudes facilitated by engagement with influencers and religious leaders, and increased openness to discussing SRHR. The involvement of men and boys has been crucial in influencing attitudes and fostering positive social norms.

Regarding HIV/AIDS awareness, 93.1% of respondents had heard of HIV/AIDS, with awareness rates of 90.1% among boys, 95.8% among girls, 92.2% among men, and 93.6% among women.

Sexual experience was reported by 48% of respondents: 20.5% of boys, 22.2% of girls, 69.1% of men, and 77.1% of women.

Most respondents (77%) recognized condoms as effective for preventing pregnancy, and 80% disagreed with reusing condoms. Condoms were viewed as more suitable for casual relationships (57%) than steady ones (45%). About 75% agreed that either partner can suggest condom use, though 44% found purchasing condoms embarrassing, indicating social stigma. Additionally, 31% were uncertain about condom use in steady relationships, highlighting the need for further education.

Over half of the respondents (54.3%) reported making their own reproductive decisions, with consistent responses across boys (52.7%), girls (50.4%), men (53.9%), and women (59.4%).

A strong engagement with formal healthcare services was evident, as 65.3% of respondents reported visiting a hospital, clinic, or doctor.

All respondents were aware of at least one FP method, with 100% knowing about male condoms, 84.9% about pills, and 54.4% about implants. Among all respondents, 28.9% had used a FP method at some point, including 9.6% of boys, 13% of girls, 33.6% of men, and 56.4% of women. At the time of the survey, 13.9% were currently using a method.

A high proportion of respondents (87.9%) knew where to access FP services, with the highest awareness among women (93.8%). Barangay Health Centres (72.2%) and RHUs (14.6%) were the most common locations for accessing services.

In assessing attitudes towards domestic violence, over 90% of respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed with justifications for a husband beating his wife, while less than 5% agreed with these justifications.

Regarding intimate partner violence, 80% of respondents reported not engaging in violent behaviours. However, 29.7% admitted to yelling, cursing, or insulting their partner. Other violent actions included slapping or spanking (2.3%), throwing objects or pushing (1.2%), restricting work or earnings (1.4%), and controlling money (1.2%).

In terms of experiences, over 70% of respondents had not encountered violence. The most common form was verbal abuse, with 4.4% experiencing it frequently. Slapping or spanking was reported by 2.1% as occurring often. More than 50% of reported violence cases involved a one-time occurrence.

Efforts to address GBV have strengthened through the reestablishment of Multi-Disciplinary Teams (MDTs) and effective community awareness initiatives. Additionally, capacity-building for healthcare providers, including training on gender transformation and adolescent care, has improved service delivery. Overall, the project’s comprehensive approach has led to substantial improvements in FP uptake, SRHR attitudes, and GBV response.

The project employed several successful strategies to promote SRHR and gender equality. Engaging youth through adolescent peer educators proved highly effective in creating a comfortable environment for open discussions, fostering trust, and disseminating information, leading to a ripple effect in communities. Engaging male members was crucial for promoting women’s reproductive autonomy, with gender sensitivity training enhancing men’s understanding and support. Practical skills training for peer educators, aligning SRHR education with religious perspectives, and engaging religious leaders in Muslim-majority areas like BARMM further strengthened community acceptance. Family conversations and tailored group sessions for men, women, and youth addressed specific needs, while leveraging existing community programs like the Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program (4Ps)1 ensured broader reach and impact without additional resources. These strategies collectively contributed to the project’s success in changing mindsets and enhancing SRHR awareness in the target communities.

The SHE project effectively aligned with national and local policies, such as GAD planning guidelines and family planning programs, ensuring relevance and complementarity with existing health and development initiatives. By tailoring activities to regional needs, such as in BARMM and Eastern Visayas, the project addressed resistance and fostered crucial discussions on SRHR and GBV. Its alignment with broader national health goals and SDGs facilitated the integration of SRHR services into local policies and health systems.

The SHE project’s design aligns well with the SocioEcological Model, addressing SRHR challenges at individual, community, and societal levels through its two-pillar approach. Pillar 1 focuses on empowering individuals and communities, while Pillar 2 targets systemic change by engaging WROs and CSOs in advocacy and policy work. A key strength of the SHE project is its inclusive design, incorporating input from local partners and stakeholders. The project was tailored to address context-specific challenges in the Philippines, such as GBV, poor access to health services, and cultural norms.

The SHE project incorporated several effective sustainability elements that should be continued. A key factor was the investment in local government units (LGUs) and health service providers, such as midwives and barangay health workers. This approach has ensured that health providers are well-equipped and knowledgeable, supporting the continuation of SRHR services beyond the project’s lifespan. Community education and training have also had a lasting impact, empowering individuals with the knowledge and skills to sustain the project’s objectives. Adolescent healthfriendly centres, established within communities, will continue to serve the population, supported by the enhanced capacity of health workers. LGU engagement varied across regions, with some areas showing strong support and even advancing policies, while others rely more on external funding.

• Future programs should focus specifically on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex and Asexual Plus (LGBTIQ+) communities, moving beyond general inclusion to address their unique needs. This includes targeted outreach and messaging to combat stigma around HIV testing and family planning services.

1 4Ps is a conditional cash transfer program of the Department of Social Welfare and Development in the Philippines.

• Future programming should normalize discussions on women’s sexual rights through culturally sensitive messaging and media campaigns. Strengthening couple counseling and relationship sessions will foster mutual respect, emphasizing women’s legal rights to bodily autonomy.

• Strategies to engage religious and faith-based leaders should be developed, including mapping key community influencers and providing capacitybuilding workshops on SRH and GBV to align their messaging with public health goals.

• Programs should specifically address the needs of adolescents aged 10-19, expanding beyond the current focus (15-19). Targeted interventions should tackle stigma surrounding SRH services and build trust through reliable communication, enhancing adolescent engagement in family planning and sexual health.

• Engaging parents is crucial for supporting their children’s decision-making in sexual and reproductive health. Future initiatives should empower parents to create a supportive environment, helping young people navigate issues like early marriage and educational pursuits.

• Schools should be utilized as stigma-free spaces for SRHR education. Future programming should expand training for teachers on gender transformation and coordinate with school administrations for regular access to SRHR information.

• A strong push for integrating CSE into school curricula is essential, as its full implementation is lacking. This should be a priority advocacy agenda to equip students with necessary knowledge for informed decision-making regarding their sexual health.

• Continued advocacy is needed for the stalled Adolescent Pregnancy Prevention Bill. Successful passage of this legislation could significantly improve adolescent health outcomes and support prevention measures. Reinforcing advocacy strategies will be crucial to advance this critical bill.

• Future program designs should ensure alignment between Pillar 1 and Pillar 2 outcomes to achieve overall project goals. While Pillar 2’s organizational strengthening efforts, like CAT4SRHR, have effectively supported Pillar 1 partners, there was a lack of clear synergies in knowledge generation and advocacy. To enhance integration, involve both pillars in the design phase, co-design the Theory of Change, and establish regular communication and joint planning mechanisms. This will help ensure that knowledge and advocacy efforts from Pillar 2 effectively support and build capacity in Pillar 1 partners.

• Future programs should balance breadth (reach) with depth to maximize impact. While broad reach is important, deep, sustained engagement is crucial for addressing complex issues like SRHR and GBV. Focus on fostering repeated, in-depth interactions and long-term involvement to create lasting change in social norms and behaviours.

• Implement a robust coordination mechanism between core partners like Jhpiego and OPH, including regular joint planning sessions, an integrated reporting system, feedback loops, and a stakeholder engagement plan to ensure alignment and effective collaboration.

• Design future projects with built-in flexibility to adapt to changing circumstances. Include provisions for revising timelines, adjustment of targets and indicators, reallocating resources, and implementing a tiered approach to service delivery. Establish clear protocols for rapid response and contingency planning.

• Start the project with a clear MEAL plan to align all partners and avoid confusion. Establish robust tracking, define M&E guidelines, and prevent overlapping activities through clear communication.

• When managing a project with core partners like Jhpiego and OPH, a strong coordination mechanism is essential. A formal meeting involving all partners and the OCA would ensure alignment, prompt information sharing, and effective collaboration. This approach would prevent isolated efforts, enhance joint analysis in reporting, and improve understanding of how each partner’s outcomes affect the other.

4Ps Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program

ABR Adolescent Birth Rate

ADA Adolescent Job Aid

ASRH Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health

BARMM Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao.

BTL Bilateral Tubal Ligation

CEDAW Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women

CEFM Child, Early, and Forced Marriage

CSE Comprehensive Sexuality Education

CSO Civil Society Organization

FGDs Focus Group Discussions

FP FP

GAC Global Affairs Canada

GAD Gender and Development

GBV Gender-based Violence

GTH Gender Transformation for Health

KII Key Informant Interviews

LGU local government unit

MDT Multi-Disciplinary Team

NSV No-scalpel Vasectomy

NYA Nortehanon Youth Advocates

OCA Oxfam Canada

OH Outcome Harvesting

OPH Oxfam Pilipinas

PCW Philippine Commission on Women

PMF Performance Measurement Framework

PSI Progestin-only Subdermal Implants

RHAN Reproductive Health Advocacy Network

RHU Rural Health Unit

SHE Sexual Health and Empowerment

SK Sangguniang Kabataan

SRHR Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights

ToT Training of Trainers

TPR Teenage Pregnancy Rate

UPR Universal Periodic Review

VAW Violence against Women

WRA Women of Reproductive Age

WROs Women’s Rights Organizations

A healthcare worker in Dangcagan, Bukidnon discusses family planning outreach activities at her Rural Health Unit.

The Sexual Health and Empowerment (SHE) project is a seven-year initiative funded by Global Affairs Canada (GAC) in collaboration with Oxfam Canada (OCA) and Oxfam Pilipinas(OPH), alongside Jhpiego and eleven local women’s rights organizations (WROs) and civil society organizations (CSOs) in the Philippines. This project is designed to empower women and girls in six disadvantaged and conflict-affected regions of the country to secure their Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights (SRHR). It has three main objectives:

a. to increase awareness and knowledge of SRHR, particularly among women and girls, including measures to prevent gender-based violence (GBV);

b. to enhance health systems and community structures to deliver comprehensive, rights-based Sexual and Reproductive Health (SRH) information and services; and

c. to strengthen the effectiveness and capacity of WROs and women’s movements to promote SRHR and prevent GBV.

The project operates through two interconnected pillars, based on an integrated socio-economic approach outlined in its Theory of Change.

This pillar aims to involve rights holders, community members, and healthcare practitioners in promoting genderresponsive and youth-friendly SRH information and services. It seeks to foster positive norms around gender and sexuality, improving health-seeking behaviors within the target population. The project works with seven local partner organizations—AMWA, FP Organization of the Philippines (FPOP), Mayon Integrated Development Alternatives and Services (MIDAS) Inc., Pambansang Koalisyon ng Kababaihan sa Kanayunan (PKKK), Sibog Katawhan Alang sa Paglambo (SIKAP) Inc., and United Youth of the Philippine-Women, Inc. (UnYPhil Women)—and one international partner, Jhpiego, to implement activities in the targeted provinces and municipalities. These partners ensure SRH services are accessible and tailored to the needs of women, girls, men and boys, creating an environment where they can freely and safely exercise their SRHR.

This pillar focuses on enhancing the knowledge and capacity of WROs, institutions, and alliances to influence and advance the implementation of SRHR-related laws, policies, and programs. It collaborates with four local partner organizations and networks— Davao Medical School Foundation Inc (DMSFI), Friendly Care Foundation, University of the Philippines Centre for Women’s and Gender Studies (UPCWGS), and Women’s Global Network for Reproductive Rights (WGNRR)—to undertake advocacy and capacity-building activities. These efforts aim to empower women’s organizations to lead SRHR advocacy and policy implementation. The goal is to foster an environment at multiple

levels—individual, community, institutional, and societal—where SRHR policies and laws are effectively enforced and promoted.

The specific objectives of the evaluation were:

• Determine whether the project has achieved its targets for outcomes as outlined in the Performance Measurement Framework (PMF).

• Evaluate the project’s assumptions as per the Theory of Change over time, determining their validity, exploring contextual shifts, and assessing the project’s adaptability, while examining the process of change if assumptions held true and identifying potential limitations if they did not.

• Identify challenges or limitations in the project’s theory of change and programming that hindered changes or improvements over time, and propose improvements for future SRHR programs in the Philippines.

• Identify lessons learned and exemplary best practices in SRHR from project partners.

• Facilitate cross-organizational exchange of experiences and learnings.

The evaluation employed a mixed-methods approach, incorporating both quantitative and qualitative techniques, and adhered to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development’s Development Assistance Committee (OECD/ DAC) criteria. It utilized a concurrent embedded design, prioritizing qualitative methods while embedding quantitative aspects within these findings. The evaluation was both summative, assessing whether the project’s objectives and outcomes were achieved, and formative, focusing on lessons learned and the effectiveness of strategies.

Key aspects of the evaluation included:

• Relevance: Examined how well the Theory of Change aligned with the diverse needs of women and girls in various regions of the Philippines, considering gender-specific needs and the involvement of local WROs and institutions.

• Coherence: Evaluate the compatibility of the project’s activities with national and local policies, other SRHR programs, and broader development goals.

• Efficiency: Evaluated the cost-effectiveness of the project, including whether activities were appropriately costed and identifying any efficiencies or inefficiencies.

• Effectiveness: Measured how well the project achieved its intended outcomes, including increased SRHR awareness and gender equality, and analysed factors influencing success or limitations.

• Impact: Assessed the overall effects of the project, including any unintended positive or negative outcomes, and evaluated its contribution to long-term goals and local capacities.

• Sustainability: Determined the extent to which the project’s approaches were adopted and supported at national or district levels, and evaluated the ongoing capacity of WROs and institutions.

The evaluation incorporated a feminist approach, focusing on gender equality and social justice throughout the process. It prioritized the voices of women and marginalized groups, employed inclusive and intersectional methodologies, and positioned evaluators as facilitators to empower participants. The approach emphasized safe, ethical practices, non-discriminatory methods, and cultural sensitivity to ensure respectful and meaningful engagement.

Outcome harvesting was also used to align with the project’s objectives and Theory of Change. This approach involved collecting diverse outcomes, such as enhanced SRHR knowledge and improved health system capacity, and analysing them to trace achievements and causal pathways. The process included engaging partners, identifying major outcomes, analysing them, and gathering community feedback to ensure the evaluation’s validity and effectiveness.

The evaluation of the SHE project was conducted across six regions: Bicol, Eastern Visayas, Zamboanga Peninsula, Northern Mindanao, Caraga, and BARMM. The focus was on assessing the project’s impact on SRHR knowledge, health system strengthening, and WRO capacity building.

A sample was drawn from the 21 municipalities supported by the project. The endline survey targeted 13 municipalities, over two-thirds of the total. Within each selected municipality, 4 barangays were chosen, resulting in 52 barangays for the evaluation. Municipalities were selected randomly, and barangays were chosen through stratified sampling. Details of the sampling process were outlined in the sampling section.

The evaluation was carried out in three phases: Foundation, Discovery, and Synthesis and Reporting.

In the Foundation Phase, the process began with a contract and kick-off meeting where the study team consulted with Oxfam to collect all necessary program documentation and discuss project details, challenges, and expectations. Following this, a preliminary meeting with the project implementing partners was organized to communicate the evaluation objectives and coordinate logistics. A comprehensive desk review of secondary data and project documents was conducted to develop data collection guidelines and adapt tools from previous phases. The team prepared a detailed inception report outlining methodologies and finalized data collection tools, which were then translated into the local language and digitized. Additionally, a Training of Trainers (ToT) program was implemented to ensure high-quality data collection. This training, conducted in Bicol (Bulusan, Sorsogon) included an orientation for enumerators and field piloting.

During the Discovery Phase, data collection occurred in the sampled municipalities across six regions. The core team, alongside local researchers, gathered qualitative data through Key Informant Interviews (KIIs) and Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) with key stakeholders. Quantitative data was collected using SurveyCTO, and an outcome harvesting exercise was integrated into the sessions with partners. Two teams of qualitative researchers were mobilized, each covering different regions, and data collection was carried out concurrently with qualitative and quantitative methods.

In the Synthesis and Reporting Phase, the collected data was analysed, with preliminary findings synthesized into a draft report. This report was reviewed by Oxfam, and feedback was incorporated to finalize the report. A PowerPoint presentation was prepared to outline the findings, and a sharing session was conducted with Oxfam and project partners to validate and clarify results. The final study report was then submitted, adjusted as necessary based on the feedback received.

The management team comprised a Team Leader, an SRHR expert, an in-country Senior Consultant, and an in-country Coordination Consultant. To prepare for data collection, Training of Trainers sessions were organized to train local enumerators. These three-day training sessions, conducted at different times in June and July, included a day of piloting to provide enumerators with real-time practice. The tools were translated into local languages to ensure clarity. Prior to data collection, coordination calls were made with barangay officers to streamline the process. In each municipality, 2-3 enumerators were assigned, with data collection taking 10-15 days per team. Quantitative data collection began simultaneously with the mobilization of the qualitative team. The survey was completed by the first week of August, and qualitative data collection concluded in the second week of August.

For secondary data collection, a comprehensive review of various documents was conducted. This review primarily involved analysing baseline, midterm evaluation, and pulse survey data to assess the project’s progression over its tenure. These reports were meticulously examined to identify changes in trends, understand the factors contributing to these changes, and pinpoint persistent challenges. Additionally, annual and semi-annual reports were reviewed to gain insights into how project activities were implemented and to identify any operational challenges noted during these periods.

A careful review was also undertaken of annual reports, learning documents, outcome harvesting reports, and other impact stories to extract valuable lessons learned. Furthermore, the RHU assessment tool used by the project was reviewed to inform parameters from the PMF. This standardized tool provided data on various standards implemented by the project, and this data was utilized to show trends in the endline. Monitoring data was also relied upon to inform certain indicators. For example, data on contraceptive prevalence rates and teenage pregnancy rates reported by health facilities was validated during site visits. Certain aspects of these indicators were integrated into survey questions, even if they were not directly reported.

A comprehensive survey was conducted with women, men, girls, and boys of all age groups to gather data on various aspects of SRHR. The survey addressed several key areas, including unmet need for FP, the extent of teenage pregnancy, perspectives on positive attitudes promoting SRHR and GBV prevention, knowledge and access to SRHR services, and reproductive health-related decision-making. The survey used indicators such as the proportion of women reporting an unmet need for FP, the prevalence of teenage pregnancies among respondents, and the percentage of women aware of SRHR service locations.

Focus Group Discussions were conducted to gather qualitative data on perspectives, knowledge, and practices related to SRHR and GBV prevention. These discussions provided in-depth insights and complemented survey data. FGDs were organized with adult women, adolescent and teenage girls and boys, adult men, peer educators, and community-level influencers. Participatory exercises within FGDs included service mapping, decision-making roleplays, and barrier identification charts to elicit deeper insights from participants.

Key Informant Interviews were conducted with RHU representatives, WROs, LGUs, facilitators, barangay health workers, GBV watch groups, project implementing partners, and the GAC. These interviews explored critical areas such as the availability and accessibility of SRHR services, the effectiveness of interventions, and the impact of the SHE project. Interviews with WROs and partners assessed their capacity, support received from the SHE project, and their successes and challenges. LGU interviews focused on their perceptions of SRHR and GBV issues, while facilitator and barangay health worker interviews examined their experiences and roles. The GBV watch group interview covered their management structure and experiences in handling GBV cases, and interviews with project implementing partners and GAC explored project effectiveness and recommendations.

Impact story analysis identified four key areas for focus, delving into the experiences of LGBTQIA+ groups and other individuals in accessing SRHR services, as well as the overall effectiveness of gender-responsive and adolescentfriendly services for community adults and youth. It also explored the role of the GBV Watch Group in PKKK and its efforts to address gender-based violence, alongside the evaluation of coordination with LGUs to enhance service delivery and community engagement.

Sampling for survey

The sample size was based on the population (total 86,386nos. with 57,878 female and 28,508 male population) of direct project participants provided in the Terms of Reference and calculated using the formula,

x = Z(c/100)2r(100-r)

n = N x/((N-1) E2 + x)

E = Sqrt [(N - n) x/n(N-1)]

where N is the population size, r is the fraction of responses that you are interested in, and Z(c/100) is the critical value for the confidence level c. Here, N=86,386, r= 0.5, Z= 1.96 Using the formula above for confidence interval

of 95% and 5 % margin of error, a sample size of 383 nos. shall be a significant sample to represent the population. However, the study team proposed a more rigorous and stratified simple random sampling based on the geographical regions of program analysis, and disaggregate the samples proportionately into male and female, using 90% confidence interval, 5 % margin of error in the above formula and also add a 5% non-response rate. The proposed sample was attempted to be equally distributed among four categories: adult women (20-49 years), adult male (20-49 years), adolescent girls (15-19 years old), and adolescent boys (15-19 years old).

A total of 1,710 surveys were administered across six regions in the Philippines. In each region, respondents were evenly distributed. Two municipalities were selected as representative samples from each province where the project was implemented. These municipalities were chosen at random. Additionally, within each municipality, four barangays were randomly selected. However, in the BARMM region, three municipalities were chosen to represent the three provinces involved in the project. The table below outlines the provinces and municipalities that were randomly selected for the survey.

In conducting qualitative research, the sampling for KIIs and IDIs was purposive, aiming to include diverse groups supported by the project. Participants were selected to facilitate a thorough assessment and comparison of outcomes among various categories. The sampling process followed the principle of saturation, with the sample size determined by the point at which no new information emerged from additional interviews or discussions. Initially, a set number of interviews and FGDs were conducted to reach saturation. If new findings persisted beyond the planned sample size, additional participants were included to ensure comprehensive coverage of the research objectives.

Stakeholder Group

Adolescent/teenage

Peer-educators (adolescent)

Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex and Asexual Plus (LGBTIQ+ group)

• There were several limitations encountered during the operationalization of data collection. Initially, the planned ToT in Bicol faced issues due to recruitment issues of the hired Training of Trainers (ToT) representatives. Consequently, the initial training sessions had to be discarded, and new trainers were hired from universities, including professors and teachers with research experience. These revised ToT sessions were provided remotely.

• Another challenge was the difficulty in finding female enumerators in certain regions. Many qualified candidates were already peer educators, leading to conflicts of interest. This necessitated additional time to identify suitable enumerators, causing delays in the data collection process, though this did not impact the final deadline or timeline.

• Weather conditions also posed challenges, particularly in BARMM, affecting field mobilization for the qualitative team and requiring rescheduling.

• Additionally, there were limitations in data analysis, particularly regarding the calculation of SRHR indexes. The evaluation team followed the reference guide provided by Oxfam, which aligned with baseline calculations, but discrepancies arose in midline and pulse surveys due to varied approaches not clearly stated in the report. Furthermore, there was confusion regarding the calculation of the indicator on the percentage of girls and women (WRA) able to make reproductive health choices alone or with partner support. The baseline, midline, and pulse surveys, as well as the reference guide, suggested considering subsets of users of FP. However, it was unclear how this was applied in calculations. For simplicity, the evaluation used a direct question to assess whether reproductive decisions were made alone, which was included in the analysis.

Nurse Dhay Jay inserts a PSI during a training in Bliss barangay, Buug, Zamboanga Sibugay, CREDIT: RACHAELA

These key findings are informed by comparative assessment against previous data collection (particularly the baseline survey and mid-term review) and against the anticipated targets for each indicator as outlined it the PMF. The design of the evaluation included the collection of both quantitative and qualitative data to allow for triangulation of findings and an increased level of confidence in the contribution made by the SHE project to the results presented. The following sections initially consider the measurable quantified changes under each pillar in comparison to the previous data, followed by discussion and verification of the findings using insights and additional evidence from the qualitative data collected.

3.1.1 Achievements under Pillar 1

1000.A: % AND NUMBER OF WOMEN WITH UNMET NEED FOR FP INCLUDING MODERN METHODS, DISAGGREGATED BY AGE GROUP

Data from survey results show that among the 344 sexually active individuals, 86 are girls and 258 are women, including those who are single (with partners), married, or cohabiting. Out of the 86 girls, 25 reported that they either want to delay childbirth or do not want a baby in the near future. Of these, only 1 girl was not using contraceptives, indicating an unmet FP need of 4%. Similarly, among the 248 women, 127 expressed a desire to delay childbirth or avoid having a child altogether. Of these women, 28 were not using contraceptives, resulting in an unmet FP need of 22.0%.

Table 3: Unmet FP need (endline)

The target was set at 25% for women and 5% for girls. By the endline, the unmet need was recorded at 22% for women and 4% for girls, indicating that the target for this indicator has been achieved. Comparing various data points, the baseline data shows that 32.3% of women and 13.3% of girls had unmet FP needs. By the endline, there was a significant improvement. This trend aligns with the Pulse Survey 2023 results, where 4% of girls and 22.79% of women reported having unmet FP needs.

% of women with unmet need for FP including modern methods

Among those who are sexually active, some report wanting to delay childbirth but are not using modern contraceptives . Have considered currently pregnant ones as well

Findings from the endline survey reveal that 48% of respondents reported having experienced sexual intercourse (single and married/cohabitating), with 37.1% indicating they were currently sexually active. Among the sexually active, 55.1% were women, 51.7% were men, 21% were girls, and 18.6% were boys. A significant proportion (42.9%) of the sexually active individuals (single and married/cohabitating) were not using any contraceptive methods at the time of the survey. While 55.2% of the ones who were sexually active were using contraceptives. Among those not currently pregnant, 37.2% have expressed a desire to avoid having more children, indicating a clear preference for FP options that can support their reproductive goals. Additionally, 25.3% of respondents wish to delay their next pregnancy.

Even among respondents who are currently pregnant, the data shows that 23% are considering expanding their families, while 19.2% prefer not to have more children. This diversity in FP desires, with 50% still undecided, highlights the crucial role that FP services play in providing individuals and couples with the choices they need to plan their families according to their unique circumstances and aspirations.

The survey results reveal a strong foundation of awareness and engagement with FP among respondents, reflecting the positive impact of ongoing reproductive health initiatives. All respondents were familiar with at least one modern method of FP, with universal knowledge of male condoms (100%), followed by a high awareness of pills (84.9%) and sub-dermal implants (54.4%).

Among the total respondents, 28.9% (495 individuals) reported having used a FP method at some point. This includes 9.6% of boys, 13% of girls, 33.6% of men, and 56.4% of women. At the time of the survey, 239 respondents were currently using a method, with 9 boys, 39 girls, 37 men, and 154 women. The most commonly used methods were pills (51.5%), followed by condoms (30.3%). Among those currently using FP, 50.6% were using pills, 13.4% were using condoms, 27.2% were using sub-dermal implants, 13% were using injectables, and 4.6% were using Intrauterine Device (IUDs).

According to the Philippine Department of Health’s Field Health Services Information System (FHSIS 2024) data, the average Contraceptive Prevalence Rate (CPR) in 2023 was 31.2%, with 36% of women being current users. From 2019 to 2023, oral pills consistently had the highest usage among FP methods, representing 36%-38% of users, followed by injectables at 20%-24%. Progestin Subdermal Implants (PSI) accounted for 17% of users in 2023. These findings align with the endline survey, where pills were the most used FP method, implants ranked second, and injectables third. FHSIS data showed implants as the third most used method, with injectables second. Permanent FP methods, such as Bilateral Tubal Ligation (BTL) and Non-Scalpel Vasectomy (NSV), remained low, at 4-5% and 0%, respectively, consistent with endline trends.

Table 5: Knowledge about, and use of contraceptives

Notably, the vast majority (95.8%) of respondents who had used or were currently using FP methods reported discussing their choice with their partner/spouse. This marks an increase from the 2020 Pulse Survey, where 85% of respondents reported such discussions, and aligns closely with the 2023 Pulse Survey, which showed a similar rate of 95%.

Corroborating the survey results, the qualitative data collection methods also highlighted positive outcomes linked to the project’s impact on unmet FP needs. Two key outcomes were the increased health-seeking behaviour of among adults regarding family planning measures.

The SHE project has also significantly contributed to the improvement of health-seeking behaviours related to FP across various communities among adults. This positive outcome has been observed and validated by participants in FGDs and KIIs, particularly with representatives from RHUs. The general improvement in the community’s knowledge and attitudes towards SRHR was also noted by the FGD participants from Eastern Visayas, who observed, “Most of the youth and even married women are now knowledgeable about FP. Compared to before, where couples would have 11 to 12 children, now the numbers are becoming fewer.” The increase in awareness about SRHR has led to a noticeable rise in the number of clients accessing services and information from RHUs. This trend has been consistent across different regions, including areas with traditionally lower engagement, such as Muslim communities.

“It has improved in the sense that many community members are now accessing services from the RHU. People are empowered about their health rights compared to before, when only a few accessed these services. In fact, we are always running out of supplies because a lot of people now visit the clinic. Unlike before, when we had to reach out to the community and educate them—often facing resistance, especially regarding SRHR information—now, they come to us on their own.”

The project has played a crucial role in normalizing the use of contraceptives and encouraging open discussions about SRH. In regions, like the Zamboanga Peninsula, women have reported improvements in communication with their male partners regarding FP, leading to more intentional and balanced FP decisions. This shift is also reflected in Eastern Visayas, where there is an increasing adoption of Long-acting reversible contraceptive, indicating a growing confidence in and commitment to sustainable FP. This trend of increased contraceptive use and proactive healthseeking behaviours is also seen in Bicol, underscoring the project’s impact on enhancing knowledge and access to SRH services. Moreover, the project has significantly reduced the stigma around seeking SRH services. In Ganassi, for example, women shared they now feel comfortable visiting clinics and asking for contraception, which was previously considered shameful.

“At

present, the pills are running out in the barangay unlike before when they would just expire, which is one of the tangible outcomes of the SHE Project.”

Additionally, the SHE Project’s impact on expanding community knowledge about FP practices is evident. A community leader from Bicol noted, “Previously, children were born one after another due to incorrect FP practices. At present, there has been a decrease in the number of pregnant women in our community because they have been educated.”

The positive shift in health-seeking behaviour among adults can be attributed to outreach activities that raised awareness and promoted FP. Peer educators and community facilitators played a key role by conducting tailored sessions for women, adolescents, and men, helping to change mindsets. On the supply side, enhanced provider capacity and gender-responsive services further encouraged visits to health centres, with community members validating that improved services have increased their use of FP services. The information supporting the findings on contraceptive knowledge is provided in the Annex II

The data on teenage pregnancies across various regions shows a general decrease over the years from 2019 to 2023. The total count of teenage pregnancies decreased from 2,281 in 2019 to 1,598 in 2023. This decline reflects a broader trend and is supported by the survey data.

A noteworthy observation is that while the flow of clients seeking SRHR services has increased, it remains higher among females and young girls compared to men . This disparity is attributed to cultural factors and the composition of service providers . The RHU representative from Eastern Visayas suggested that the presence of more female service providers might make men feel shy or embarrassed to seek services, particularly for FP . This issue is even more pronounced in Muslim areas, such as BARMM, where traditional views on masculinity play a significant role . The RHU representative from Ganassi explained,

“One of the reasons why men are not seeking services is because they feel shy and might think it is quietly insulting to ask for FP services. Many men think that FP is about stopping birth altogether, and they feel insulted by that.”

The average Teenage Pregnancy Rate (TPR) for all project sites was 18.51 in 2023, a reduction of 5.92 from 2022. However, the 2023 TPR appears to be higher by 8.67 compared to 2019 due to differences in the source of projected teenage population (TPR denominator) across the years.3 The average TPR for project sites in 2023 is lower than the national Adolescent Birth Rate (ABR) from 2019-2022. The TPR is decreasing but still remains higher than desired in some regions.

The survey data shows a similar trend. To substantiate the value of the TRP, a proxy indicator was set, asking adolescents in the survey if they were pregnant at the time of data collection. Of the surveyed teenagers, 16.8% (66 individuals) reported having been pregnant at some point. Out of the 66 teenagers who reported past pregnancies, only 12 (2.9% of total adolescents) were pregnant at the time of the survey, and 5.6% (23 individuals) had given birth in the past 12 months.

The target for the endline was set at 3.2% for girls reported to be pregnant during the survey, with the actual endline result achieving 2.9%. This surpasses the target, and the decrease in the reported pregnancy rate can be considered a positive outcome.

Comparison of data points

Are you currently pregnant? (Applicable to age group 15-19 girls)

Corroborating the survey findings, the qualitative data revealed a positive change in adolescents’ health-seeking behaviour.

The impact of the SHE project on adolescents’ access to SRHR services has been notably positive, though the trend varies across different regions. In most areas, except for the BARMM, there has been a significant shift in how adolescents seek information and services related to SRHR. Adolescents have traditionally relied on close peers and family for SRHR information. However, there is a growing trend of adolescents accessing information and services through teen centres and Adolescent Friendly Health Facilities (AFHF) established by the SHE project.

“Despite facilities being available in the RHU for adolescents, none of them are accessing the services. This is likely due to the community’s negative perception when unmarried boys and girls go to the clinic, even just for counselling.”

– RHU REPRESENTATIVE, BARMM

A representative from the RHU in Clarin emphasized the importance of privacy in these facilities, stating, “The availability of private rooms within these facilities allows for open and confidential communication.” This sentiment was echoed by an RHU representative from Sta. Margarita, who noted, “Adolescents are very comfortable visiting the RHU because they are assured of their privacy. You need to empathize with the adolescent to gain their trust.” In contrast, the situation in BARMM, specifically in Ganassi, remains challenging. Adolescents in this region continue to rely on peers and parents rather than utilizing the available AFHF centres. This reluctance is largely due to the negative perception within the community regarding unmarried adolescents accessing SRHR services.

The improved service-seeking behaviours among adolescents in other regions can be largely attributed to awareness symposiums in schools and sessions facilitated by peer educators. In the event that the peer educators are unable to address any queries, the RHU staff would be consulted. These efforts have contributed to adolescents’ comfort in accessing information and services. The success of the SHE project is also evident in specific cases where adolescents have benefited directly from the SRHR services. A powerful example comes from Clarin, where an RHU representative shared, “One young woman who became pregnant at a young age is now accessing the FP program thanks to SRHR services. This access allows her to continue her education while planning her future.” This story exemplifies the positive impact the program has had on young people’s lives.

Despite challenges like stigma and shyness, adolescents expressed positive views on accessing SRHR services, appreciating respectful treatment, privacy, and confidentiality from RHU staff. In Caraga, Eastern Visayas, and Northern Mindanao, youth highlighted improvements like private consultation rooms and attentive care. While barriers remain in regions like BARMM, overall feedback underscores the importance of respectful interactions in encouraging youth access to SRHR services.

1000.c: Perspectives on positive attitudes that promote SRHR and GBV prevention among target population

CALCULATION METHOD: Based on the SHE project indicator reference guide measuring changes in perspectives uses a set of statements for participants to respond to ranking from “strongly disagree” through to “strongly agree”. For each statement, the percentage of negative attitudes (disagree and strongly disagree) is subtracted from the percentage of positive attitudes (agree and strongly agree). The result is expressed as a percentage of the total respondents for that statement. Next, the simple average of all statements is calculated for each indicator. Responses of “neither agree nor disagree” and those who preferred not to answer are not included in the calculation.

This index approach was utilized to calculate the overall average across three key areas: reproductive autonomy, sexual autonomy, and economic autonomy. The specific methodologies for measurement and the findings for each of these areas is discussed further below. In combination the three provide an index for overall attitudes that promote SRHR and GBV prevention. It is important to note that direct comparisons with mid-term data on these parameters are not feasible due to differences in calculation methods. The endline report has adhered to the baseline approach, where negative attitudes are subtracted from positive attitudes, with neutral responses being excluded. The index reveals that, on average across the three areas, perceptions of positive attitudes towards promoting SRHR are 0.62 for boys, 0.68 for girls, 0.63 for men, and 0.62 for women. The highest index value is observed among girls

The SRHR index was calculated using sub-indexes for reproductive autonomy, sexual autonomy, and economic autonomy only. However, statements intended to inform the implementation of the SRHR index were not taken into account in the calculation of the overall composite score4. While these statements were included in the evaluation, as they were in the baseline survey, they were not factored into the calculation of this dimension.

Additionally, the statements used for measuring economic autonomy in the baseline differed from those used in the endline. This change occurred because Oxfam determined that the baseline statements related to women’s economic autonomy did not have a direct linkage with SRHR. As a result, a new set of statements was developed for the endline. It is important to note that the calculation method used in the endline is similar to that of the baseline. However, the approach to calculating the overall attitude score in the mid-term and pulse surveys was different.

4 The findings for implementation of SRHR policies are presented in the Annex.

The target has been exceeded for all four groups. The target set was 60% for women, 57% for girls, 60% for men and 58% for boys. Compared to the baseline, there has been an increase in the index value in the endline for all women, girls, men, and boys. The values show that in the baseline, the index score was 50% for women, increasing to 62% in the endline. For girls, the baseline score was 48%, which rose to 68% in the endline. For men, the score improved from 46% in the baseline to 63% in the endline, and for boys, it went from 47% in the baseline to 62% in the endline.

Perspective on positive attitudes that promote SRHR and GBV prevention among target population

Girls:

Boys:

Girls: 61%

Women: 64%

Boys: 61% Men: 60%

Girls: 68%

Women: 62%

Boys: 62%

Men: 63%

Calculation of the three indexes –reproductive, sexual and economic autonomy among girls and women

Please note that the index score is not simply the percentage of positive responses received; rather, it is calculated as the positive responses on attitude minus the negative responses on attitude.

Three indicators were used to measure reproductive autonomy. The first indicator, access to information and services, had an overall index score of 84%, with a score of 84% for boys, girls, and women, and 83% for men.

The second indicator, decision on whether and when to practice contraception, had an average index score of 77%, with scores of 75% for boys, 83% for girls, 76% for men, and 75% for women. Girls showed the highest agreement regarding their ability to choose and use contraceptives, though this agreement was slightly lower when considering

adults’ perspectives. The third indicator, decision on whether and when to have a baby, scored 56% overall. This lower score was influenced by the low support for the right to terminate an unplanned pregnancy, which had an index score of only 32%, with girls scoring highest at 45% and boys at 32%.

Overall, the reproductive autonomy index at endline was 72%, an increase from the baseline value of 61%.

Please note that the index score is not simply the percentage of positive responses received; rather, it is calculated as the positive responses on attitude minus the negative responses on attitude. Since the index calculation is based on positive attitudes minus negative attitudes, the value can sometimes be negative. A negative index value indicates that the proportion of respondents with undesirable attitudes is higher than those with positive attitudes.

The Sexual Autonomy Index is based on two indicators: decision on sexual initiation and sexual negotiation and communication. For decision on sexual initiation, the index score was notably low at -27%, with particularly negative scores for girls initiating sexual relationships -42% and girls enjoying sexual relations -31%. This suggests that perceptions from adult men and women are less supportive compared to the views of girls and boys themselves. On the other hand, the indicator for sexual negotiation and communication scored higher at 62%, with similar values across all groups—boys, girls, men, and women. Additionally, the perception of the need for accessible counselling services scored 80%, indicating broad agreement across all groups. The overall Sexual Autonomy Index stands at 38%, reflecting a generally low level of sexual autonomy, especially in terms of initiation, while showing more support for sexual negotiation and access to counselling services. This represents an improvement from the baseline value of 23%.

Assessing various statements, it was observed that people’s perceptions regarding decisions on sexual initiation were mostly negative. The data suggests a low value in terms of girls and women initiating and enjoying sexual relationships, indicating that the community views sexual enjoyment as more of a man’s role. Moreover, the perception becomes even more negative when girls initiate and enjoy sexual relationships. The community tends to believe that unmarried girls should practice abstinence rather than engage in sexual initiation and enjoyment. This negatively influenced the index value. Another important factor is the perception of how much girls and women can negotiate sexual experiences and communicate with their partners about when to have sex or refuse sex. Although there was generally a positive attitude, when it came to the question of whether a partner or husband having sex with others was acceptable, the index value was only 50%. This indicates a significant split, with only half of the community disapproving of sexual relations outside of marriage. Additionally, there was a noticeable community acceptance of girls and women obliging to have sex even when a partner or husband refuses to use a condom.

Please note that the index score is not simply the percentage of positive responses received; rather, it is calculated as the positive responses on attitude minus the negative responses on attitude.

Economic autonomy was assessed using six statements as part of a single indicator. The overall score for economic autonomy was 80%, with scores of 78% for boys, 85% for girls, 81% for men, and 77% for women. The high agreement among respondents that women and girls can and should prioritize career and financial stability before having children highlights a progressive understanding of economic influences on SRHR. This perspective underscores the importance of providing women and girls with the resources and support needed to make informed decisions about their reproductive health, free from economic pressures.

It is acceptable for GIRLS AND WOMEN to avoid having more children because they cannot adequately provide the financial support it requires

Having control over financial resources allows GIRLS AND WOMEN to make better decisions about their sexual and reproductive health

Economic stability influences girls’ and women’s decision to use contraceptives

It is acceptable for GIRLS AND WOMEN to delay having children to focus on her education

More reproductive autonomy enables women to be more economically stable

Substantiating the survey findings, the community expressed positive attitudes toward SRHR during the FGDs and KIIs. The qualitative data presented below reflects the community’s general perspectives on SRHR, highlighting their attitudes and views on related topics.

As evident from the qualitative data, one of the project’s core achievements was enhancing women’s awareness of their autonomy, both reproductive and sexual. By educating women about their right to autonomy and their ability to make decisions about their bodies, the project significantly influenced their health-seeking behaviour. Many women began making informed choices about when to have a baby and how to space their pregnancies, leading to increased utilization of RHU services. This empowerment was evident across all project areas and stands out as a major success. Through sessions discussing their bodies and their rights, women gained the confidence to exercise their autonomy. Community members shared that previously reproductive decisions were solely directed by male family members or parents. With the project’s support, women can now make their own decisions regarding the number of children they wish to have and the timing of having another baby.

In some areas like Zamboanga Peninsula and Northern Mindanao, the representatives from the partner organization explained that narratives emerged of women initiating sexual relationships with their spouses, challenging the misconception that they could not refuse their husband’s advances. In Northern Mindanao, women have experienced a significant shift towards sexual autonomy, reflecting a growing sense of empowerment and confidence in their relationships.

“I

thought before that only men can ask us for sex; now, I learned that I can also ask my husband to have sex with me if I want to.”

– WOMAN FROM NORTHERN MINDANAO

Furthermore, the women emphasized that they have learned a lot about empowerment, with one noting, “We should not shy ourselves when it comes to these matters.” One woman from Ganassi, BARMM also explained, “Understanding my right to decide when to have children allowed me to space out my pregnancies, improve my health, and provide better care for my children. I feel more confident and see the positive impact on my family’s well-being, which I believe would not have been possible without this knowledge.”

The project led to a more balanced approach to decision-making within families. Previously, there was a prevailing belief that family members should only follow the husband’s directives, which was a significant concern regarding sexual and reproductive health rights. One male participant in the FGD in Bicol highlighted, “If only the man’s wishes are followed, he might force his wife to have sex even if she doesn’t want to. This leads to abuse, not only affecting the wife but also the children.”

One of the other achievements of the project is the engagement of youth and their positive reception of the SRHR concept. The project reached young boys and girls in schools through peer educators and successfully changed their mindset.

There is a noticeable increase in knowledge about sexual and reproductive rights, which is evident in their refusal of early marriages and their willingness to discuss ASRH issues with peer educators and in Usapan sessions. Though the impact is not immediate, it is anticipated that when these young individuals become adults, they will make conscious decisions about using FP. Project partners credit the project’s activities for bringing about this change, particularly among young boys. In terms of the increase in knowledge about SRHR, different aspects of SRHR stood out more for adolescent boys and girls. Some of the aspects were HIV/AIDS and teenage pregnancy.

HIV awareness: One of the key learnings for both boys and girls during the Usapan sessions was about HIV, particularly its impact and prevention. This learning was evident across all regions, with boys from Eastern Visayas especially noting the importance of the HIV awareness activities. These sessions were highly effective, with one participant emphasizing that they led to an increase in HIV testing among peers, though adolescents noted that despite the rising number of HIV cases in the municipality, many still hesitate to seek help. They suggested that comfort levels might improve if individuals knew someone at the RHU who could assist them. Participants also observed that, while Filipino families are generally conservative, encouraging peers to use condoms is slowly becoming normalized within the community, though this acceptance is still less common among younger adolescents. Participants from Northern Mindanao noted the impact of these sessions, with one adolescent boy stating, “Through the sessions, we learned not to engage in sexual activities to avoid unexpected pregnancies. We also learned about safe sex and using condoms.” Another boy from the same region emphasized, “I learned about HIV and STIs that can be acquired through sexual intercourse, so it is important to use condoms.” In Bicol, a girl highlighted the value of the sessions, noting, “HIV/AIDS Awareness was particularly valuable …Personally, it also taught me about safe and unsafe sexual practices.” The focus on HIV prevention was also beneficial for LGBTQIA+ communities, as observed in Eastern Visayas during FGDs. An adolescent boy shared, “Sessions focused on HIV prevention and safe sex have been crucial in raising awareness among our peers, especially given the high vulnerability of LGBTQIA+ groups to such health issues.”

The survey results support these findings, showing that 93.1% of respondents were aware of HIV/AIDS. Additionally, 55.7% of participants reported that HIV/AIDS can be treated and cured, while 78.6% knew that a simple test can determine if someone has AIDS. Although there is some confusion about whether AIDS is curable, it is encouraging that over three-quarters of respondents understand that testing can identify the presence of AIDS.

Teenage pregnancy: The program’s focus on teenage pregnancy and early marriage was another area of success. Participants reported a greater understanding of the social and cultural factors that contribute to these issues, with many expressing a newfound empathy for those affected. The discussions on child, early, and forced marriage (CEFM) served as an eye-opener, particularly for adolescent boys, highlighting the severe consequences of such practices and the importance of respecting individual rights and choices. In this regard, an adolescent boy from Bicol noted, “The discussion on CEFM was an eye-opener to the social realities affecting adolescents like me in other parts of the country and the world.” Adolescent girls from all regions unanimously agreed that teenage pregnancy is not normal and were sensitized to the physical and mental health consequences it can have on young girls. They emphasized that early pregnancy is a significant issue, where girls noted that it causes problems for society and is met with judgment and negative reactions from the community. While they acknowledged that various factors, including unfortunate circumstances like rape and abuse, can lead to teenage pregnancies, they stressed that the blame should not solely fall on the young girls involved. Instead, they highlighted the importance of understanding SRH among the youth.

The SHE Project has also significantly transformed attitudes towards gender, sexuality, and reproductive health, fostering a more open and mature dialogue around these topics. Participants have moved from feeling uncomfortable and dismissive to embracing these discussions with greater seriousness and openness. As one female participant from Bicol reflected, “I no longer feel awkward talking about reproductive health. Before, I considered people who discussed these topics as too vulgar. Now, I am much more open.” Another woman from Caraga shared, “Initially, I found the topics inappropriate and immodest. But now, I am open and more mature in discussing such matters.”

“The Parent-Teen Talks have deepened the relationship between parents and teens, fostering greater empathy and understanding. It’s clear that these discussions are helping both sides gain a better grasp of each other’s perspectives.”

– COMMUNITY INFLUENCER, EASTERN VISAYAS

There has been a positive shift in the community’s attitude towards youth and adolescent SRHR. In Eastern Visayas, the discussions around SRHR, particularly during Parent-Teen Talks, have significantly enhanced the openness between parents and their children. While parental conversations traditionally centred more on issues like early marriage rather than contraceptive use, the recent initiatives have broadened this scope. Community leaders from Eastern Visayas acknowledged that although not all parents are fully informed about SRHR, efforts like the ParentTeen Talks have helped bridge this gap. Moreover, there is a noticeable openness among community influencers regarding youth access to SRHR services. Leaders are supportive of adolescent girls and boys utilizing contraceptives and other SRH resources. This progressive stance reflects a growing recognition of the importance of providing youth with the means to make informed health decisions. Traditionally, there was a significant amount of judgment and shock when high school students sought contraceptive pills. However, through the SHE Project, some community members have gained a better understanding of individuals’ rights to access these services.

In community FGDs held in Caraga, Zamboanga Peninsula, and Bicol, there was a notably positive attitude towards unmarried couples accessing contraceptives. Adult participants in these regions recognized the importance of contraception for preventing unplanned pregnancies and ensuring a better future for women. One male participant from Caraga remarked, “It’s okay because if a child becomes pregnant unprepared, she will suffer.”