OPEN SPACES

Quarterly Newsletter

Ojai Valley Land Conservancy

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Stefanie Coeler President

Martha Groszewski Treasurer

Sarah Sheshunoff Secretary

Annie Nyborg

Bret Bradigan

Dave Comfort

Fiona Hutton

Jerry Maryniuk

Jim Finch

Lizzy Chouinard

Lu Setnicka

Tim Rhone

STAFF

Tom Maloney Executive Director

Tania Parker Deputy Director

Brendan Taylor Director of Field Programs

Vivon Sedgwick Restoration Program Director

Adam Morrison Development Manager

Nathan Wickstrum Communications & Outreach Manager

Rhett Walker Grants Manager

Ethan Van Dusen Office Manager

Carrie Drevenstedt Development Database Coordinator

Christine Gau Land Protection Specialist

Linda Wilkin Preserve Manager

Keith Brooks Land Steward

Sophie McLean Native Plant Specialist & Nursery Manager

Claire Woolson Rewild Ojai & Volunteer Coordinator

Martin Schenker Restoration Field Crew Manager

Madison Moore Nursery Assistant

Caden Crawford Restoration Field Crew

Kiandra Kormos Restoration Field Crew

Emma Gibson Restoration Field Crew

Celeste Ayala Nursery Intern

Lilac Feliciano Nursery Intern

Mission:

To protect and restore the natural landscapes of the Ojai Valley forever.

STAY CONNECTED WITH OVLC: OVLC.ORG

FIND US ON FACEBOOK & INSTAGRAM

BOARD & STAFF CHANGES

FAREWELL TO BOARD MEMBER SANDY BUECHLEY

We extend our heartfelt thanks to Sandy as she concludes her long and dedicated service on the OVLC Board of Directors. A lifelong advocate for the outdoors and community stewardship, Sandy has been a guiding force in our mission to protect Ojai’s natural landscapes. Her thoughtful leadership, generosity, and deep-rooted love for this valley have left a lasting legacy. We’re so grateful for all she’s done for our community.

WELCOME KIANDRA KORMOS & EMMA GIBSON RESTORATION FIELD CREW

One too many winters in Upstate New York led Kiandra to pursue her BS in Zoology from UCSB. Although she quickly realized her interests lie in flora rather than fauna. Specifically, her fixation is on the role of plants in big picture ecosystem functioning. She is eager to apply her knowledge and curiosity to OVLC and aspires to make a positive impact on our understanding of the natural world.

Born and raised in Santa Barbara, Emma’s early connection to the coastline, canyons, and chaparral shaped a lifelong appreciation for California’s natural beauty. With an associate degree in Environmental Science, years of experience in organic farming, and a strong background in native landscaping, she brings both practical knowledge and deep-rooted passion to her work. Now in Ojai, she’s excited to learn the local ecology while contributing to restoration.

Cover photo by Nathan Wickstrum

FROM THE DIRECTOR

OVLC recently had the opportunity for an educational field trip to the Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing over US-101 in Agoura Hills. That impressive project serves as an inspirational reminder of the importance of thoughtful planning for the needs of wildlife and biodiversity.

In thinking about the landscape context for wildlife in and around the Ojai Valley, it’s safe to say that we are blessed to live in an area with abundant connectivity (despite the recent roadkill of a mountain lion along Santa Ana Road!). In fact, in protecting Rancho Cañada Larga, we are creating the southwestern “anchor” of a linkage of potentially continental proportions. A deer, bear, or lion can move out of Rancho Cañada Larga along the largely private but undeveloped north-facing slopes of Sulphur Mountain, across Highway 150, and up into the vast Los Padres National Forest.

From the national forest, a wandering mammal has many options to the north and east until it hits Interstate 5, which clearly presents an all-too-often lethal barrier to wildlife movement. As with the Annenberg Crossing, there will need to be some enhanced passageways across or under Interstate 5. Once those are in, Tejon Ranch and The Nature Conservancy’s Randall

Preserve to the East of Tejon provide largely intact protected habitat into the Southern Sierra and the vast holdings of federal land all the way to the Great Basin and the Cascades.

Thanks to persistent private lands conservation efforts, the situation on either side of Interstate 5 in the Tehachapis is vastly different from the linkage being created across the 101. The Annenberg Crossing is where it is due to the fact that it was the only 1,600 feet of highway north of LA with conserved habitat on both sides of the highway. Luckily, thanks to good planning at the Ventura County and Ojai City levels, our wildlife species are not nearly as restricted in their movements.

Around the world folks are realizing that connectivity matters for the long-term support of biodiversity. The protection of Rancho Cañada Larga creates a strong footing to protect the free movement of our wildlife today and into our shared future. As you learn more about the protection of this historic ranch throughout this newsletter, I hope that you will consider making an end of year gift to our Land + Legacy Campaign to secure this future.

Tom Maloney, Executive Director

LAND +

Ojai Valley Land Conservancy’s campaign is both about saving and restoring the historic Rancho Cañada Larga and ensuring the organization has the capacity to steward it—protecting this once-in-a-generation opportunity while growing the organization to meet the challenge of maintaining our exemplary level of stewardship across all our preserves and more than tripling OVLC’s land holdings.

LEGACY

Rancho Cañada Larga

As you drive into the Ojai Valley from Ventura and Highway 33 narrows just before Casitas Springs, you’ve likely noticed the large “For Sale” sign that has stood for years on the property known as Rancho Cañada Larga.

This 6,500-acre ranch stretches from the valley floor all the way to Sulphur Mountain Road, encompassing both sides of the first three miles of the Sulphur Mountain Trail. Beyond the highway, you’ll find cattle grazing on rolling grasslands, hillsides blanketed with coastal sage scrub, deer taking refuge in shady oak woodlands, and birds and wildlife drawn to the creeks that wind down from rugged ridgelines.

This historic rangeland in Western Ventura County is virtually untouched since the 1800s. The expansive landscape—one of the last large, near-coastal open spaces in Southern California—supports vital habitats for mountain lion, California Condor, and other wildlife.

With over 800 acres within a key wildlife corridor, the ranch provides the southern anchor to an extensive network of wildlife corridors. Protecting Rancho Cañada Larga ensures its beauty and ecological value are preserved for future generations.

California Condorwithtworavens

EXPANDING CAPACITY

Acquiring the 6,500 acre Rancho Cañada Larga is the start of a generational opportunity to restore the ecology and heal the land. This acquisition more than triples OVLC’s current land holdings, and provides the opportunity for OVLC to do even more in securing our collective future through science-based restoration, stewardship and recreational programs. To meet this responsibility, our campaign includes critical investments in OVLC’s long-term capacity including additional staff and expertise, and the resources to ensure this landscape is protected, restored, and cared for in perpetuity.

AN ANCHOR FOR CONSERVATION & RESTORATION

Rancho Cañada Larga offers a rare opportunity to secure vital wildlife habitat and advance climate resilience. Its expansive landscape serves as a natural refuge, with north- and northeast-facing slopes providing sanctuary from the hotter, drier conditions on the south-facing slopes. This heightens the importance of science-based land management that prioritizes habitats and climate resilience.

The ranch’s size enhances efforts to create a critical wildlife corridor, connecting Ventura to the Topatopa, Tehachapi, and Southern Sierra ranges. This connectivity is vital for sustaining large mammals like mule deer, cougar, and the California Condor.

A KEY PIECE IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA’S CONSERVATION PUZZLE

Protecting Rancho Cañada Larga is about more than one landscape—it’s about securing the future of a region. Located within the Transverse Ranges, the ranch represents the southern anchor to the Sierra Madre-Castaic Linkage, a vital wildlife corridor connecting major mountain ranges.

The Transverse Ranges span 5.4 million acres and support nearly 500 threatened species. These lands stabilize ecosystems, mitigate wildfires, and ensure clean air and water for millions. With 19 million people living within an hour’s drive, conserving these lands is essential not just for the environment, but for public health, equity, and climate resilience.

More locally, it strengthens important wildlife corridors. Nearly adjoining Ventura Land Trust’s Harmon Canyon and Ventura Hills Nature Preserve, this land extends connectivity into Sulphur Mountain, linking directly to our valley and tying into three of OVLC’s river corridor preserves. By securing this piece, we’re stitching together a continuous landscape that supports wildlife movement, climate resilience, and the health of our communities.

CONNECTING COMMUNITIES TO NATURE & EXPANDING ACCESS TO CALIFORNIA’S GREAT OUTDOORS

Protecting and restoring Rancho Cañada Larga expands outdoor access, strengthens community resilience, and preserves vital landscapes for future generations. The ranch offers Ventura’s Westside and surrounding communities a vital connection to nature, supporting recreation, health, and well-being. This conservation effort ensures that everyone has access to the benefits of nature.

The ranch offers green space for hiking, biking, birdwatching, and family recreation. Research shows that access to nature improves physical and mental health, builds social connections, and supports local economies through sustainable recreation.

OVLC’s Stewardship staff are outstanding in their field. Stewardship means both caring for the land and providing singular recreation opportunities. The ranch is already home to a threemile segment of the Sulphur Mountain Trail, with panoramic views of the Pacific Ocean and Ojai Valley. Its network of dirt roads can be transformed into trails that link to the Ojai Valley/

Ventura River Trail, connecting communities from Ventura to Ojai. By protecting Rancho Cañada Larga, we can create new outdoor experiences that enhance the health, well-being, and connections of our community.

While getting to know the land and recreation planning will take time, our first priority is stewardship—keeping the land clear of dumping, trespass and encroachments, and other threats, and building a deep knowledge of the property, just as we do on all our preserves.

Today, OVLC manages more than 27 miles of trails on 2,600 acres. Adding Rancho Cañada Larga more than triples that responsibility. We plan to integrate opportunities for hiking, biking, horseback riding, and nature-based activities in the future—but this year, this campaign gives us the capacity to meet this challenge and keep delivering the stewardship across all our lands that our community expects.

A MOVEMENT YOU CAN BE PART OF

BUILDING A VISION FOR RESTORATION

Protecting Rancho Cañada Larga is just the first step. As long-term stewards, OVLC will implement a comprehensive restoration strategy to transform the landscape into a thriving, resilient ecosystem. The ranch provides critical habitat for over 20 special-status species, including the California red-legged frog and southern steelhead trout.

Our initial focus will be restoring riparian areas and wetlands—vital habitats that support native species, improve water quality, reduce runoff pollution, and recharge groundwater supplies. Managed grazing will also control invasive species and foster native plant recovery, allowing wildlife to return and ecosystems to thrive.

And OVLC knows how to deliver. In just the past five years our restoration team has launched a comprehensive program to restore Ojai Valley’s creeks and rivers—including the necessary projects for our vision of an arundo-free watershed. This fall, we started three arundo-removal projects in San Antonio Creek. Every dollar you give to our campaign is multiplied many times over in restoration funding and impact across our valley.

With 25+ years of restoration experience, OVLC is ready to ensure this landscape, and landscapes across our valley, remain a vital resource for wildlife and people alike, now and for future generations.

COMMUNITY PARTNERSHIPS

Protecting Rancho Cañada Larga is a collaborative effort led by Trust for Public Land, Patagonia’s Holdfast Collective, and the Ojai Valley Land Conservancy. We’re working with partners like the Barbareño-Ventureño Band of Mission Indians, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, and other stakeholders to protect this vital landscape for all Californians.

Together, we can ensure that Rancho Cañada Larga remains protected and continues to benefit future generations.

This effort is led by Trust for Public Land, Patagonia’s Holdfast Collective, and the Ojai Valley Land Conservancy, but we need your support. Community involvement has always been vital to California’s conservation success. By joining this movement, you’ll stand with thousands who believe in a future where nature is protected and accessible to all.

Our goal is to raise $7.5 million in start-up, endowment, and capacity building funds from private donations to ensure the longterm stewardship of Rancho Cañada Larga and all of our preserves. And we are almost there!

Now is our chance to shape the future. Will you donate today to help us reach our goal?

Ranching at Cañada Larga

As people start talking about the future of Rancho Cañada Larga, one question is on many minds: what will happen with the cattle?

It’s a fair question. These hills have supported cattle for generations, and grazing remains part of the landscape’s identity. Conservation practitioners have learned the hard way that one has to be very thoughtful and deliberate when altering land management practices that have been around since before statehood. Cattle will continue to be part of the picture as the Ojai Valley Land Conservancy studies how best to care for and restore the property’s diverse habitats. To better understand the current operation, OVLC staff sat down with Kim Perkins and his daughter, Sarah Perkins, who have worked cattle here, on and off, for decades. Their story offers a look at the practical work behind grazing and how it might evolve alongside conservation goals in the years ahead.

Kim Perkins’s connection to California ranching stretches back three generations. His grandfather once owned the Alisal Ranch near Solvang before the family moved inland to the Santa Ynez Valley. Kim bought his first place near Cachuma Creek in 1969 and began building his ranching career by leasing small pastures across the Central Coast. Over the years, he managed herds on large ranches such as Rancho San Julian and, eventually, here at Rancho Cañada Larga.

By the mid-1980s, Kim had learned the rhythm of Ventura County’s Mediterranean climate, from cool, wet and green winters to long, hot and dry summers. He has weathered them all with quiet persistence and a working patience that has become

second nature. “It’s a tough ranch,” Kim said, looking toward the hills. “But it’s good country when you take it year by year. Every season asks something different of you.”

Sarah Perkins brings both education and heart to the operation. After graduating from the Thacher School she earned a Bachelor’s degree in Fruit Science with a concentration in Water Science and Water Law from Cal Poly San Luis Obispo, followed by graduate work in animal science and genetics through a joint Cal Poly and UC Davis program. Her studies combined water systems, soil management, and animal physiology; knowledge that now shapes how she approaches the ranch. “I thought I’d get away from animals,” Sarah said with a laugh. “I tried studying water and soils and everything that supports life from the ground up, but I missed the animals too much. I realized I loved seeing how everything connects: the land, the water, the cattle, and how each decision you make ripples through the system.”

That perspective drives her management style. Sarah embraces state of the art animal husbandry such as genetic monitoring and careful recordkeeping to build a herd suited to both the cold, irrigated pastures of Modoc County and the rugged hills of Ventura. Her focus on calm, healthy cattle means less stress on the herd and fewer impacts on the land.

Each year, the Perkins family moves their cattle between their irrigated ranch to the north in Modoc County to the winter range here at Rancho Cañada Larga. Calving usually happens in the early winter in Ventura, where the climate is mild and the grass germinates earlier. In April/May when the landscape begins to

Photo by Sarah Perkins

dry out here, the herd trucks north to the irrigated meadows in Surprise Valley in Modoc County. That seasonal rhythm, Kim says, is what keeps both landscapes healthy. “Our whole plan is based on what the land tells us,” he explained. “You can’t force it. Some years we leave early. Some years we wait. You adjust.” “Flexibility is everything,” Sarah added. “Ranching teaches you to pivot. You can’t know what next year will bring.” Rather than rigid schedules, they rely on observation: resting pastures after grazing, watching how grasses recover, and maintaining enough cover to protect young plants and hold soil moisture through summer.

Ranching in the foothills comes with constant challenges, and much of the Perkins family’s approach is shaped by what the land can support in a given season. One area where OVLC’s restoration goals align with their longstanding management practices is in improving how water is distributed across the ranch. Kim explained that previous work with Natural Resource CS brought a new water line up into the higher country, which has made it easier to rotate cattle and rest different areas of ground. Reliable upland water points help cattle spread out naturally, reducing concentrated use along creeks and giving the pastures time to recover. It’s a practical example of how ranch operations and habitat restoration can move in the same direction.

Roads tell a similar story. Floods and heavy rains can blow out roads and cut off access to remote pastures for weeks. After major storms, Kim and Sarah sometimes take on the road repairs themselves just to move cattle safely. “It’s the part people don’t see,” Kim said. “You can’t care for the land if you can’t reach it.” Both Kim and Sarah pointed to practical improvements such as relocating corrals to more functional sites and continuing targeted weed management for plants like artichoke thistle and castor bean, which have taken hold in some areas due to past disturbance and roadside dumping. Addressing these non-native species supports better forage conditions and a more resilient grassland system overall. “You see how the land responds,” Sarah said. “Small changes can shape what comes back and how the cattle use the landscape.”

In a place as dynamic as Rancho Cañada Larga, the landscape itself is always shifting. Kim has watched creek channels scour clean in big winters, hillslopes slump, oaks seed new groves in unexpected places, and wildlife return after fire and drought. “Every ten years or so, the creek just resets itself,” he said. “That’s the nature of it here: steep country, big water, constant change.” Kim and Sarah’s lived observations are vital as OVLC and its partners begin studying the ecological conditions of the ranch. Understanding how the land and natural communities respond to weather, grazing, and time will help guide future restoration planning.

Rancho Cañada Larga has been a working ranch for a very long time, and as conversations continue about its future, questions about grazing are expected. Some wonder whether the cattle will stay; others want to know how grazing and restoration can coexist. Sarah says she often hears those questions firsthand. “People stop along the road to watch the calves in spring,” she said. “They’ll ask what’s happening, and I tell them the cattle move north in summer when the grass dries up and come back once the green feed returns. It’s just part of the seasonal cycle here.” That willingness to talk about what they do, and why, helps demystify ranching for visitors and neighbors alike. OVLC’s Executive Director, Tom Maloney, says that curiosity is a good sign. “It shows how much people care about this landscape,” he said. “As we look ahead, the goal is to listen and learn how the land functions, how it responds, and how management decisions can support its recovery and resilience.”

OVLC’s mission is to protect and restore Ojai’s natural landscapes forever. That includes open space, wildlife habitat, and, at times, lands that remain active and productive. As discussions about Rancho Cañada Larga continue, OVLC will take time to observe before making any major management changes. Grazing will remain one of several tools used to manage nonnative grasses and reduce wildfire risk, but its role will be guided by ecological study and adaptive management. Kim and Sarah understand the need for the long view. They have seen the land change with weather, drought, and flood, and they continue to adapt with care and intention. “You just keep trying to do right by the ground,” Kim said quietly. “That’s all any of us can do.”

The future of Rancho Cañada Larga will unfold with care, patience, and continued attention to what the land itself reveals.

Sarah Perkins and her father Kim, longtime cattle managers at Rancho Cañada Larga

THE PLANTS THAT CARRY FALL FORWARD

As fall settles over Ojai, the landscape begins to slow. Plants and animals alike prepare for dormancy as the days grow shorter and cooler. Most blooms fade away, saving their energy for spring’s return—but as we near winter, a few hardy native plants continue to thrive. Ragweed, coyote brush, manzanita, and mistletoe to name a few, all of which mammals and pollinators depend on to get them through the season.

If you find yourself in a grassland with an open canopy, where sun strikes dirt among dormant bunchgrass, or dodging between mulefat thickets in cobble-ridden riverbottoms, you will often encounter our friend the western ragweed ( Ambrosia psilostachya). This lovely member of the Asteraceae (sunflower) family blooms in late summer through fall, where gentle gusts guide its pollen across the valley. This unassuming plant, being wind-pollinated, is often overlooked for its habitat value. As temperatures drop in early winter and willows have shed their leaves, ground-foraging birds such as the California quail (Callipepla californica) rely on the mature seeds of western ragweed as a primary source of food to sustain them until spring. Rich in protein and fat, this seed provides a critical energy source during times when other sources of nourishment, like insects, are more difficult to find.

Coyote brush (Baccharis pilularis) is another abundant native plant that serves as an important late-season source of nectar in the Ojai Valley. It flowers from August to December, beginning to bloom just as summer starts to wind down. Its clusters of cream-colored flowers resemble a winter frost and seep the sweet scent of honeysuckle. Its branches covered in fluffy white seeds are reminiscent of snowfall, until the wind sweeps them away. The timing of coyote bush blooms lines up exactly with the migration of one of America’s favorite pollinators. The southbound migration of monarch butterflies (Danaus plexippus) brings them through the Ojai Valley as they search for sites to overwinter. Baccharis pilularis blooms prove to be a key source of nectar for them as they refuel for the rest of their journey. Coyote brush’s reach doesn’t end with monarchs; field observations have documented dozens of insect species visiting a single stand for a late-season nectar feast.

Another species you might come across in our valley is the bigberry manzanita ( Arctostaphylos glauca). From late winter into early spring, this hardy and beautiful shrub begins to produce supple, bell-shaped flowers perfectly suited to the slender beaks of hummingbirds. In our area, both Anna’s and Allen’s hummingbirds are common. You may have heard one whizzing by on a trail walk or chirping high in a sycamore canopy. Because these tiny birds lose body heat quickly, their hearts beat an astonishing 1,200 times per minute to maintain healthy oxygen levels. This rapid heartbeat burns through energy fast, requiring hummingbirds to consume 1.5 to 3 times their body weight in food each day. A single bird may visit hundreds of flowers daily to keep up with its incredible metabolism.

One manzanita shrub can produce several thousand flowers per season, making it a living buffet. The blossoms may also shelter tiny insects that offer an extra, protein-rich snack. With their long, spindly branches, manzanitas also provide ideal perches where hummingbirds can rest before taking flight again. These birds are an integral part of our ecosystem—so the next time you spot one while out on the trail, take a moment to pause and appreciate their swift, brilliant beauty.

Bigberry manzanita ( Arctostaphylos glauca)

Mistletoe (Phoradendron macrophyllum)

Coyote brush (Baccharis pilularis)

Western ragweed ( Ambrosia psilostachya)

Beyond the shrubs, there’s another native species that’s easy to miss. When the trees drop their leaves and the branches go bare, something strange is sometimes left behind. High up in the canopy, tangled green clusters of mistle toe (Phoradendron macrophyllum) cling to the limbs of black walnuts, willows, and cot tonwoods. Mistletoe gets a bad rap because it’s a parasitic plant, pulling water and nutrients from its host, but it also plays an important role during the colder months. The plant produces thousands of small white berries, filled with sugar, which ripen in winter and provide a crucial food source for local wildlife, like the mysterious phainopepla. These sleek, sharp-crested birds have deep red eyes. The males are a glossy black, the females a soft gray, and both rely almost entirely on mistletoe berries to get through the winter. A single bird can eat up to 1,000 berries a day if they are abundant enough. As they feed, they simultaneously help spread the plant by wiping the sticky seeds onto nearby branches and trees. Though mistletoe carries centuries of myth and holiday lore, out here it’s happiest doing what it does best—feeding the birds.

The relationships between native plants and wildlife don’t pause for winter. They shift and adapt, just like the land itself. Whether its quail rummaging for ragweed seeds, monarchs stopping at coyote brush, hummingbirds feeding on manzanita, or phainopeplas munching on mistletoe, these seasonal moments are happening all around us. As you explore the valley this season, keep an eye out for the birds, insects, and blooms that make this time of year special in their own way. The more we notice, the more we understand how to care for what’s here.

Phainopepla (Phainopepla nitens)

WHY 2025

IS AN ESPECIALLY MEANINGFUL YEAR TO GIVE

As we approach the end of the year, many people are thinking about the timing of their charitable gifts, and this year timing truly matters. Starting in 2026 for taxpayers who itemize, there will be new floors on donations and reduction in the tax benefits for those in the top marginal tax rate — meaning gifts made before December 31, 2025 may offer greater tax benefits than the same gifts made next year. These shifts could make charitable giving less advantageous in the years ahead, which is why making your gift before the end of the year may be more beneficial.

In simple terms: a donation made this year may offer greater tax benefits than the same gift made next year.

Here are a few examples of how you can plan ahead and make the most of the current rules:

• Make your annual gift before December 31 so it qualifies under the more favorable 2025 deductions.

• Bundle multiple years of giving into a single 2025 gift

if that fits your plans; savvy donors choose to do this periodically to maximize tax savings.

• Consider giving appreciated assets , like stocks, which may help reduce capital gains taxes while supporting the causes you care about.

• Check in with your financial and tax advisors , even briefly, to see how a year-end gift can fit into your overall planning.

If you’ve been thinking about making a larger gift, renewing your support early, or adding an extra contribution this year, 2025 is a uniquely strong moment to do so. Your generosity has a direct impact on the landscapes and community you love, and making your gift now may also be the most advantageous for you under the current tax laws.

A gift made before December 31 can make a meaningful difference—for you, for your values, and for the future of the Ojai Valley.

Anna’s Hummingbird (Calypte anna)

Caden Crawford, Emma Gibson, Kiandra Kormos, & Martin Schenker

HOW TO MOVE A BEHEMOTH

STONE AGE SKILLS FOR MODERN TRAIL BUILDERS

A rock-solid crew at Valley View Preserve celebrates progress on the new retaining wall along John’s Fox Canyon Trail.

At first, moving rocks feels like being a Stone Age human: no words, just grunting and groaning as you jab your rock bar aimlessly at the burdensome behemoth before you, trying to get it to budge. But slowly, an understanding dawns on you, and you realize that your exhaustingly heavy steel bar is a kind of seesaw plank, with you on one end and the behemoth on the other. This revelation gets you talking with your rock-rolling partners, guessing back and forth about where to wedge the bar beneath the behemoth, whether to lever up with a fulcrum, or which corner to row the rock with—and on and on. You blabber through it, struggling to find the right words to make this demanding task a little less impossible. But as the rock begins to roll, precision increases. Movements become easier to predict, placement and leverage more accurate. Before long, you’re back to barely speaking—because now you and your partners are in sync, turning the behemoth as if it were a wheel: the rock the hub, your bars the spokes, and you the force turning it round and round.

Now you’ve rolled the rock to its destination and plopped it into the hole you dug. But this rock is no smooth monolith—it’s knobby, ridged, divoted, and rounded in all the wrong places. The behemoth wobbles inscrutably, and you’re back to groaning. Try an Irish jig on its surface—really get it rocking— and see if you can sense the knobby thimble it’s improbably teetering on. Once you pinpoint the offending spot, it’s time for a soliloquy: a plea for the rock to just sit still. To shim is a shame, so you can’t just toss smaller pebbles under your behemoth like napkins under a short table leg.

Back to talking it out, then—finding the right words to describe what you can no longer see: the rock’s underside and how it sits in its hollow. Maybe if you could just rock it like a baby—scoop the bottom up while tilting the top back—it might settle down?

Of course, in the hills of Ojai, it’s mostly coldwater sandstone, weighing about 150 pounds per cubic foot, so simply yanking it out is easier said than done. Alas, you’ll have to wiggle it around in the hole, being extra careful not to collapse the dirt walls and turn your tidy pit into a crater that can’t catch the rock at all. Groaning once more, you use surprisingly soft, delicate maneuvers to coax this hard rock into just the right spot.

Lo and behold—after much exasperation—you find just the right fulcrum: flat enough to fit the narrow void between your wall and the rock, but not so thin that it disintegrates under pressure. The rock catches without any roll! That only took

Photos by Anthony Avildsen and OVLC Staff

a couple of hours for one rock—not bad! Now do it dozens and dozens of times...

That’s the challenge our volunteers face this fall. Across the valley, they’re building rock structures on trails. At the Ojai Meadows Preserve, volunteers are constructing steps through the pond drainage; on the Valley View Preserve, they’ve begun a large retaining wall to shore up John’s Fox Canyon Trail. Preserve users have been thrilled—those new steps at Ojai Meadows Preserve might be the most popular trail feature we’ve ever built. After the mid-October rains, hikers got to test them out, and many were astonished by how much work goes into moving each stone. So were a few of our volunteers—especially the new ones.

as we move through that bell curve of communication—from grunting, to fumbling for the right words, to finally working in seamless rhythm where only “Got it” and “Free” are needed. Creativity flourishes as we figure out how to move behemoths with nothing but hand tools and slings. Craftsmanship sharpens too, since we use dry-stone masonry—no cement, just precision and care.

It might take only seconds to walk past a retaining wall or climb a flight of stone steps, but it’ll take our volunteer program until the end of the year to finish these projects. That’s perfectly fine—doing this work by hand isn’t just necessary (especially on the steep slopes of Valley View); it’s rewarding. Confidence grows

Despite the time and frustration, these structures are durable. The sandstone is about 40 million years old, give or take, so we can reasonably expect a few decades out of our handiwork. Best of all, the rock belongs here—it looks right at home on our trails. At first, working with rock might seem daunting, but it’s an adventure. So even if you’ve never volunteered on trails before but want to evolve your skills, sign up at ovlc.org/volunteer and join us this winter!

Brendan Taylor, Director of Field Programs

At Ojai Meadows Preserve, volunteers build new stone steps through the pond drainage—creating a durable and natural path for hikers after the rains.

WHEN THE ARUNDO IS THIS TALL, WHO ARE YOU GOING TO CALL? OVLC!

RIPARIAN RESILIENCE

FOR THE VENTURA RIVER WATERSHED

We kicked off Arundo removal season in September and are on track to make great progress this year. We have about 20 contractor crew members and four biological monitors working on Arundo and other invasive species treatments across Lion Creek, San Antonio Creek, and the mainstem Ventura River (alongside OVLC restoration staff). We started with re-treatments of sites we’ve been working on over the past few years, and are working our way downstream each reach, with the goal of treating 40 acres of Arundo and many other invasive species across 200 acres through January 2026.

We’re not just removing Arundo, we’re taking a comprehensive approach to actively restore these riparian corridors that are so critical to our environment and our community. With support from CAL FIRE’s Forest Health Program and the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, we’re going to be planting thousands of native plants and trees in areas where we remove Arundo, which will enable us to improve shade, reduce erosion, improve water quality, and promote biodiversity.

This year is the first time we are operating three Arundo removal sites simultaneously, a symphony of harmonious noxious weed treatment conducted by our restoration team. However, we can’t achieve this dream alone. R.A. Atmore & Sons contribute their passion for invasive species treatment daily, and it has been so

inspiring to be alongside the crews that enjoy the complexity and challenges of the field. Working as a team in unison, they make Arundo removal look easy, which it absolutely is not.

Arundo stalks can reach up to 30ft tall, have razor sharp leaves and grow in dense stands, becoming a matrix of old stalks woven together with new growth, acting like a net that accumulates rocks, sediment, and debris from stream flows. Add to that the challenging access from steep creek banks, poison oak, and walls of Arundo that stretch for acres. We are also grateful for the expertise brought to this restoration work by Lawrence Hunt, a biologist who has been working to restore riparian habitat in the watershed since 2007 and provides invaluable insight to the project. We’ve also teamed up with Safe Passage Youth Foundation’s Puma Crew. The Puma Crew is a mentoring program for at-promise youth that helps them stay out of gangs and succeed by developing real-world skills, including habitat restoration! For two days, the Puma Crew worked in San Antonio Creek, cutting and hauling Arundo stalks and learning about the riparian ecosystem and what we can do to protect and enhance it. This is restoration work at its most extreme, and we are grateful for those who work with us to make it possible.

Vivon Sedgwick, Restoration Program Director

Site visit with our CAL FIRE Southern Region Forester & Forest Health Grant Manager

ORCHARDS TO OAKS

The restoration team was weeding between plantings, focusing on our target species. Mustards and thistles occupied our minds and hands. It is a low grasp, at the base of the weed where the shoot becomes root, and then a slow pull. If it is too quick, the root snaps and the plant grows back—somehow with even more vengeful vigor. If it is too slow, the site never shifts to native canopy. So, the weed’s roots unravel from soil, and the index fingers callus. I grabbed and pulled, combing through a thick section of young plants, until I found an unusual plant. At first thought, this was a prostrate knotweed. It was not. The low growing plant was a few inches long, with cupped, delicate, bindweed flowers. It was a sweet plant, and one I had not seen before. As it lay in my hand, I realized I’d found a small-flowered morning glory—one of the few with such a limited range.

Though the site was covered in avocado trees and some bald patches of weeds, this plant, and other locally significant plants, speckled between rows. Witchgrass spritely laughed in the language of wide whimsical inflorescences. Prostrate amaranth crawled and carpeted the clay wet ground. Small oaks stitched the rows together. All of this whispered of a story. These plants wait, stunted in individual growth or population size. These living things, shadowed by shivering avocado leaves, are small solutions to big problems. We know the story of climate change, the context and cycle that it has created. Microclimates shift, water rates increase, biodiversity is lost, fires run hotter, longer, more frequent, and the floods are of biblical proportion. Not to be alarming, this causes three distinct issues in our valley—ecological type conversion, agricultural land conversion, and communal existential dread. This means the native plant communities shift to nonnatives, agricultural crops become unviable in new climates, and we, together, are anxious. These symptoms are felt deeply, and they ripple through the landscapes of the ecological, agricultural, and mind landscapes.

With this, I must remind you, dear reader, of a solution. This is not THE solution, but a string in the web that fetters these dreadful feedback loops. Habitat restoration is the act of repairing degraded ecosystems to native habitat—typically using the yin and yang of native plant installation and invasive plant removal. For habitat restoration to work, we must observe the land and cultivate the skills, relationships, and commitments that turn restoration from an idea into a lived practice.

Ojai Valley Land Conservancy (OVLC) has been doing restoration for decades now, informed by many consultants, ecologists, land managers, and community members. In our

Photo by Emily Ayala

Small-flowered morning glory

WHAT RESTORATION CAN BE

From vacant fields to declining orchards, OVLC’s Private Lands Restoration program transforms degraded landscapes into thriving habitat for native plants and wildlife.

This image illustrates that transformation over time. On the left, during the project’s first year, irrigation to the orchard is reduced while native plants are installed and natural recruitment is encouraged. As the trees gradually decline over the following two to five years, native species begin to take hold and rise in their place.

On the right, after five to fifteen years, the land is well on its way back to a natural state— providing refuge for wildlife, supporting native flora, and reconnecting fragmented habitats. Restoration is a powerful solution to the ecological challenges we face today. Even the conversion of small parcels of land builds hope for a more beautiful, climate-resilient, and biodiverse future.

Interested in restoring your land? Email us today to set up an initial site visit: rewild@ovlc.org

records, we watch the photo points and transects turn back to native cover. On our field days, we see roadrunners protect their land, bobcats pass through greenways, and birds migrate atop coyote brush and toyon. In the community, the shared memory is held in daily walks and hikes. However, we know there is so much more than OVLC land. We know that nature (seeds, wind, and skunks alike) does not often stop at property lines.

Led by many long discussions, mapped minds on whiteboards, stitched together interviews, questions, and data, OVLC offers Private Lands Restoration under the program of Rewild Ojai. It is distinct from Rewild Ojai certified gardens, as it is active restoration occurring typically on highly denuded or transitioning agricultural lands. These areas stitch together habitat across the Wildland Urban Interface. When land is at risk for productive or ecological decline, whether that be on the crop borders, sections of orchards, or whole swaths of land, restoration offers land

owners a practical path forward. OVLC assists with restoration planning and implementation, tailoring the plans to the land’s nuances. The next step is restorative work for all things. The nursery stock must be grown, observations made, cultural shifts shared, and knowledge exchanged. This ecological literacy will be nurtured and watered by participation, education, and care.

These moments of learning to move in rhythm with nature’s cycles ask us not only to act, but to notice small indicators across the land that whisper stories, guide our hands, and shape the restoration we undertake. Just as a single morning glory surprises among thistles, every deliberate act of care, observation, and planting becomes part of the web of resilience.

Sophie McLean, Native Plant Specialist & Nursery Manager

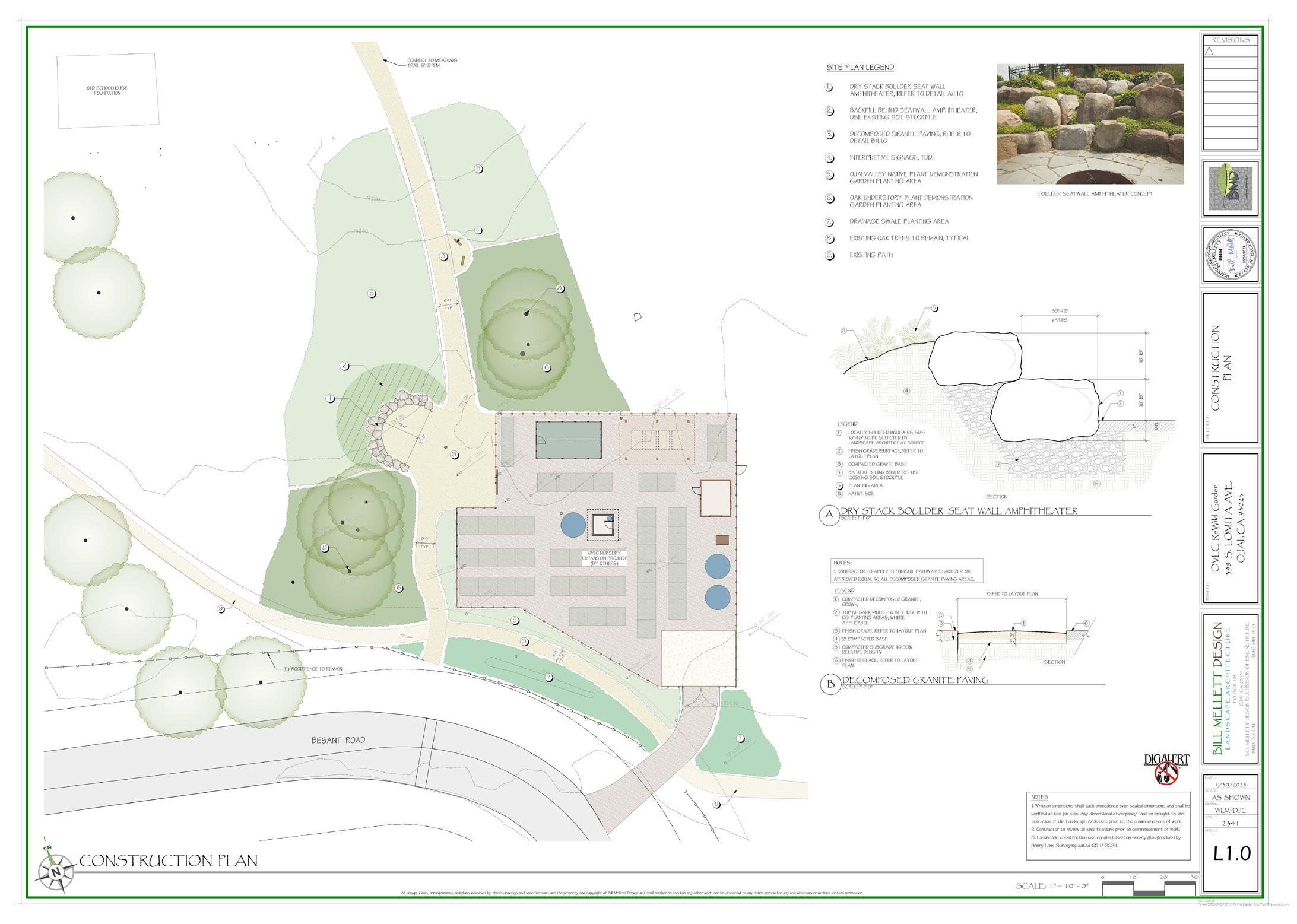

We are thrilled to announce that our OVLC Nursery is undergoing a major expansion to better serve the Ojai Valley and the Ventura River Watershed. As climate change intensifies and native habitats continue to be fragmented or lost, the need for regionally adapted native plants has never been more urgent. Native plants grown from locally sourced genetics are critical for ecological restoration. Many commercial nurseries offer native species that, although look similar, have been genetically cultivated or sourced from distant and unknown regions. When our goal is to restore ecosystems and preserve healthy populations, planting these unknown genetics can disrupt local gene pools and can result in plant populations that lack the localized adaptations necessary for survival in our watershed.

Collecting diverse populations of wild seed and propagules from OVLC preserves across the valley allows us to engage in ethical and responsible sourcing, encouraging long-term ecosystem health and more resilient restoration projects. Through this process we are preserving genetic traits that have evolved over thousands of years to be adapted to the specific soils, climate, and biological interactions of our local ecosystems. The plants sown and grown in our nursery directly support the wildlife that rely on local plant species for survival, stability, and longevity.

Our nursery located at the Ojai Meadows Preserve is far greater than a production site. The nursery is a community-driven center where plant sales, volunteer projects, and high school interns are rapidly growing local knowledge and capacity. Through the nursery expansion project, we are investing in more space and new infrastructure to support our growing role in regional restoration, seed conservation, and community resilience efforts.

It’s an exciting time as the long-anticipated nursery improvement construction has begun and will continue into December and possibly January. This will include a significant expansion of the nursery’s size; a new, centralized irrigation system; solar array shade structure; storage solutions; and sanitation improvements to ensure healthy and phytophthora free stock. Alongside the nursery expansion, we will also be creating a native plant demonstration garden, filled to the brim with the local diversity of our plant species. Bulbs, grasses, sagescrub, woodland species, and wildflowers will establish a garden mosaic. This will not only provide important propagules for nursery production but will be a space to learn and gather in a shared community space. So, stay tuned for updates, plant sales, planting days, and our grand reopening. We’re grateful to be working with talented, local contractors to bring this vision to life. Special thanks to

Nick DeYoung, Nick Wingate, Dan Colbeck, and Bill Millet for their expertise, dedication, and in-kind donations! We also wish to acknowledge the grant-funding that makes this expansion possible. Funding for this project provided by the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection’s Business and Workforce Development Grants and Forest Health Program as part of the California Climate Investments Program. Thank you to the Rotary Club Ojai West, Rotary Club of Ojai, Ojai Valley Garden Club, and Athletic Brewing Company for contributing to the nursery expansion as well.

Together we are building a healthier and more resilient future, one locally grown plant at a time!

WELCOME NEW DONORS!

Amanda Ravenhill

Andrew Leicht

Anibal Lopez

Ann Hester

Anthony Baker

Anthony Benedetti & Melissa Crews

Ascent Wellness

Ben Thorne & Eliza Howard-Thorne

Bruce Lairson

Candice Alexander

Christopher & Beth Burke

Christopher Lawson

Cody McMillan

Corinne Berryman

D Allen

Dan Hershman

David & Nancy Hill

Deepa Vasudevan

Dee Zinke

Della Addison

DJ Moore

Dustin Waller

Emily Hirsch

Emmy Aras &

Jamie Emerson

Erica McLoughlin

Erin Smith

Frank Gallegos

George Moll

Guido Hunziker

Heidi Frochtzwajg

Ivan Kauffman

Jamie Boyce

Jennifer Lawlor

Jessica & Jason Striker

Jessica Dunne

Joel Snyder

John Hill

Jon Solorzano & Kelly Lack

Jorge Quezada

Katie Spencer

Kellie Swift

Kellye Patterson

Kerstin Kuhn

Kevin Keating

Krish Hernandez

Kristina Jones

Larry Wanamaker

Lee Ann Harris

Leigh Adele Merrihew

Liana Harp

Lori Steinhauer

Maegen Anderson

Phaneuf

Margaret Winter

Marisa Garcia

Matthew Couch

Mauricio Gomez

Megan DeZur

Melody Morgan

Mike Adelmann

Mike Callaghan

Molly Allison

Monica Wiesblott

Nicole Ferro

Pamela Starnes

Patrick & Lauren Snyder

Raven Waterfall

Renate Cuff

Richard Roos-Collins

Ronnie Glassman

Roxana Llano

Ruby Li

Sarah Cotner

Sarah Thomas

Sawyer Downey

Sophie Ward Koren

Suvi & Nick Niles

Sydney & John Paul Jones

Tassy Burkle

Tina Johnson

Yen Glassman

Zack Haskell

Zoe Lumiere From: 8/12/25-11/5/2025

Madison Moore, Nursery Assistant

OJAI MEADOWS SPONSORS

STEELHEAD SPONSORS

SAN ANTONIO CREEK SPONSORS

PARKWAY SPONSORS

IN-KIND SPONSORS

SPECIAL ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

IN MEMORY OF

Betsy Vanleit

from Jessica Mann and Arthur & Judy Vander

Betty Andersen

I can see Mom sitting by the pond in the meadows of Ojai watching the birds and aquatic life and enjoying the breezes. from Judy Piazza

Christopher Bates from Sandra Torres

Dale Bard from Chuck Journey

Donna Freiermuth from Jean Kilmurray MacCalla

Elisabeth Gallagher from Anna Khaja

Gerald Goldman

We have great memories of the hikes the four of us enjoyed together. from Bill Norris & Judith Hale Norris

Hugo Ekback from Linda & Boris Chaloupsky

Janelle Sharp

For all the moments she spent on the trails feeding her spirit. from Debora Kirkland

John Brooks

In loving memory of Johnny from Judy Robertson

Kerry Madden from Erin Smith

Master Douglas McKinley Shively

In honor of all your father has done. from Henry Lane

Otis & JoAnn Wickenhaeuser from John Wickenhaeuser

Pamela J. Windsor from Jay Windsor

Pamela West from Brandon West

Ralph Dorrian Finner You would love it here from Charmian Schreiner

Stan & Marianne Paul & Joanna from Lesley Letofsky

Thomas MacCalla from Jean Kilmurray MacCalla

Tom & Dot Horton from Jean Meckauer

IN HONOR OF

Adam Morrison from Tom Maloney & Andrea Jones

Al Earle With love and cacti! from Catherine Meek

Ann & Harry Oppenheimer from Anonymous

Besant Hill School from Heidi Molbak

Charlie Clarke

Happy birthday, Charlie! from Elizabeth Clarke

Claudia Makeyev from Steven Hooper Jr

David Harralson from Brad Wieners

Derek & Ilana Oliver I love you! from Ilana Satnick

Hazel Stillman from Allison Stillman

Judy & Arthur Vander Happy 70th Anniversary from Ann & Harry Oppenheimer

Kenneth & Louanne Fay from Eileen Laber

Maddy & Dean Hazard Happiest Anniversary from Cheryl Sills

Tom Lowe from Chuck Journey

Tom Treadwell from Meredith & Tom Treadwell

Zayd & Zoey from Crystal Davis & Brad Meiners

Acknowledgments: 8/12/25-11/5/2025