HUMANS of IMPACT

FREE WINTER 2023

EXPLORING LIFE, LAND AND CULTURE FROM THE HEART OF THE YELLOWSTONE REGION

SPECIAL EDITION

When science, innovation, technology and creativity collide with a common goal of creating something unlike anything else, you get Peak Skis by Bode Miller. Not just a new ski. A radically better ski. For every part of the mountain. But only available at PeakSkis.com

GENERAL CONTRACTING FOR LUXURY REMODELING & NEW CONSTRUCTION pjourney@jandsmt.com | 406.209.0991 | www.jandsmt.com WE CARE ABOUT EVERYTHING WE DO

REDEFINING

PARADISE

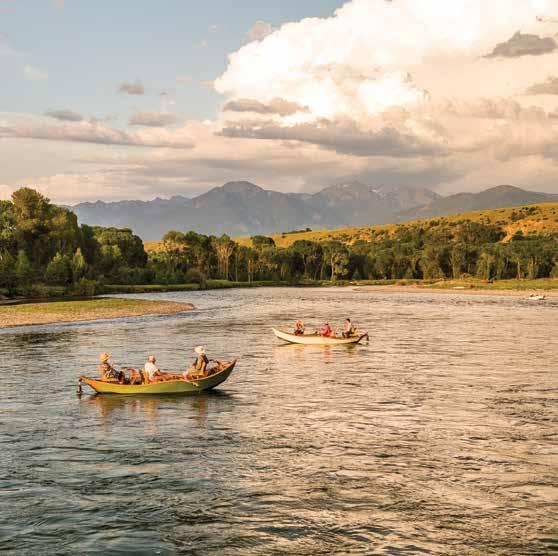

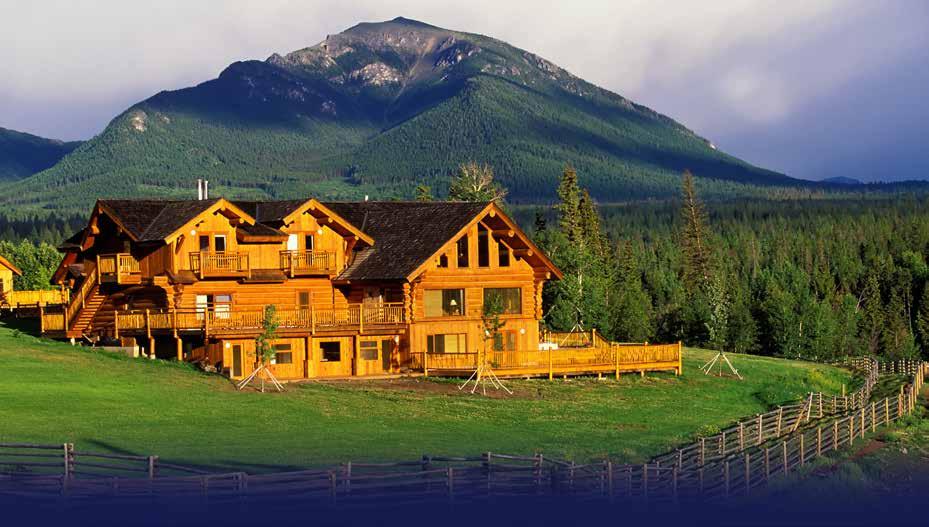

We’re not sure a more perfect combination exists – adventures by day across Paradise Valley, followed by the comforts of Sage Lodge by night. With Sage Lodge as your basecamp, you can enjoy fly fishing on the Yellowstone River, private spring creeks, or in nearby Yellowstone National Park. And while Paradise Valley is known for its abundant, blue-ribbon waters, there’s also more to enjoy at Sage Lodge. Grab a hearty Montana-inspired meal in the Fireside Room or The Grill, pamper yourself at The Spa, and kick back with a cocktail on the patio while taking in breathtaking views of Emigrant Peak.

VISIT SAGELODGE.COM OR CALL 855.400.0505.

59065

55 Sage Lodge Drive, Pray, MT

Svalinn breeds, raises and trains world class protection dogs. Choose a Svalinn dog and you’ll be getting real peace of mind in the package of a loyal, loving companion for you and your family.

svalinn.com 406.539.9029 Livingston, MT

Are you ready to Svalinn love?

TABLE OF CONTENTS THE ACTION

19 Swift

20 Fluid

21 Graceful

OUTBOUND

26 Our

ENVIRONMENT 36 Kaitlyn

42 Charlie

45 Matt

54 Steven

60

67

INDUSTRY 74 Chris

80

84 David

94

102

112

CULTURE 118

128

134

140

148

FEATURED

156

8 MOUNTAIN MTOUTLAW.COM

ISSUE UPDATES

Water: Protecting Montana’s treasured rivers

Landscape: Creating passageways for Montana wildlife

Passage: Preventing salmon extinction

GALLERY

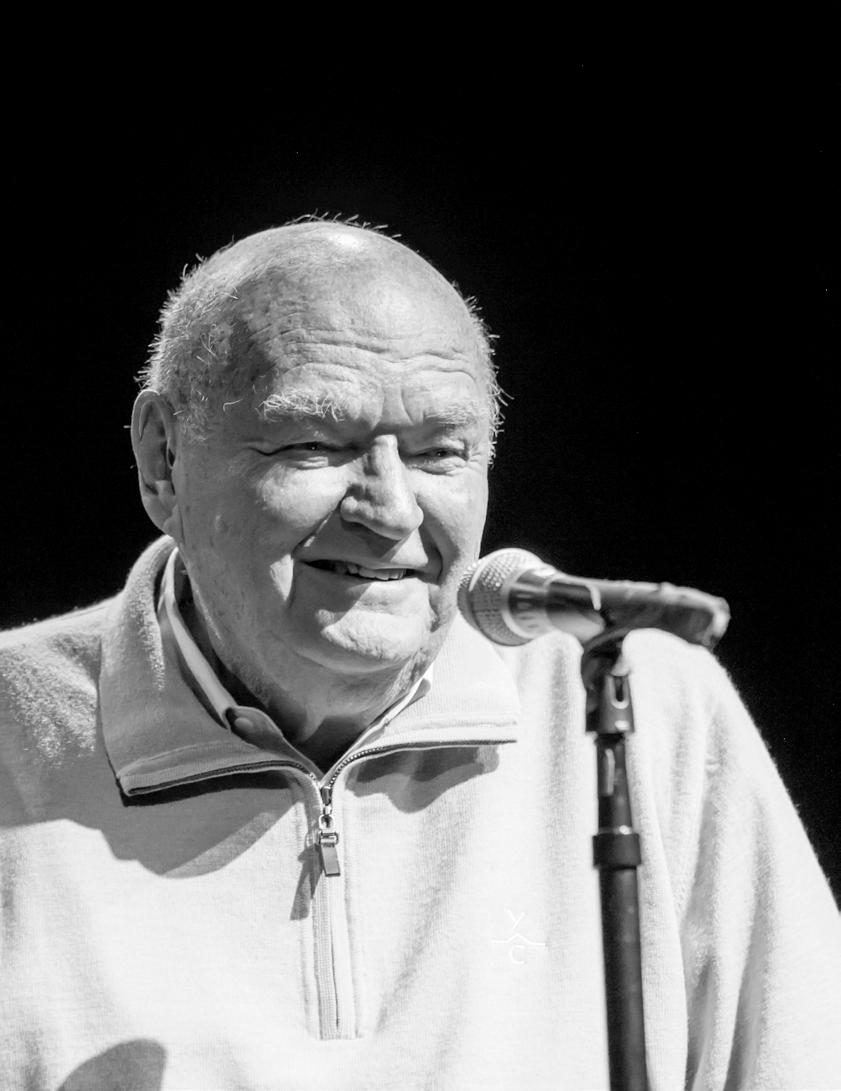

Neighbor, Warren Miller

Farrington: Protecting our winters

Gaillard: Prioritizing sustainability in cannabis growth

Skoglund: Ranching for a new land ethic

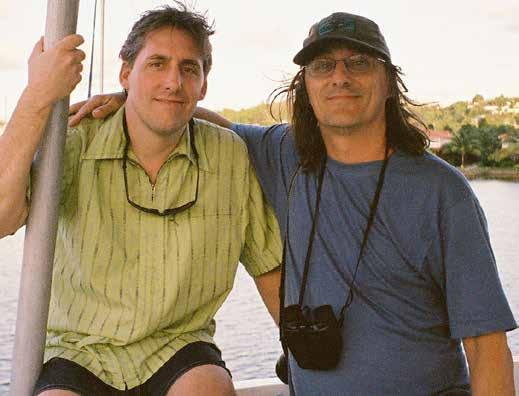

Amstrup and Daniel J. Cox: Connecting Bozeman’s conservation community with the Arctic

Jonathan Marquis: A mission to visit and draw all of Montana’s glaciers

Brett Jenks: Q&A with Rare CEO on initiating change for a healthier earth

Walch: Sparking a DEI movement in the ski industry

Kris Inman: A quest to empower women in STEM

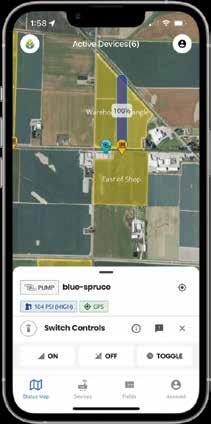

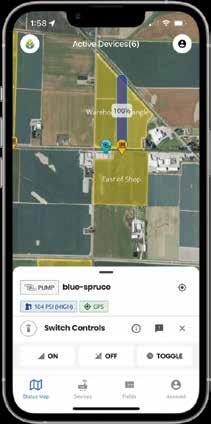

and Connor Wallace: Tech to save water and simplify farming

Bode Miller and Andy Wirth: Shaking up the ski industry

Waded Cruzado and Leon Costello: ‘Year of the Bobcat’

Yarrow Kraner: Everyone’s inner superhero

Gov. Doug Burgum: Preserving Theodore Roosevelt’s legacy

Hilaree Nelson: Honoring the life of one of the greatest mountaineers

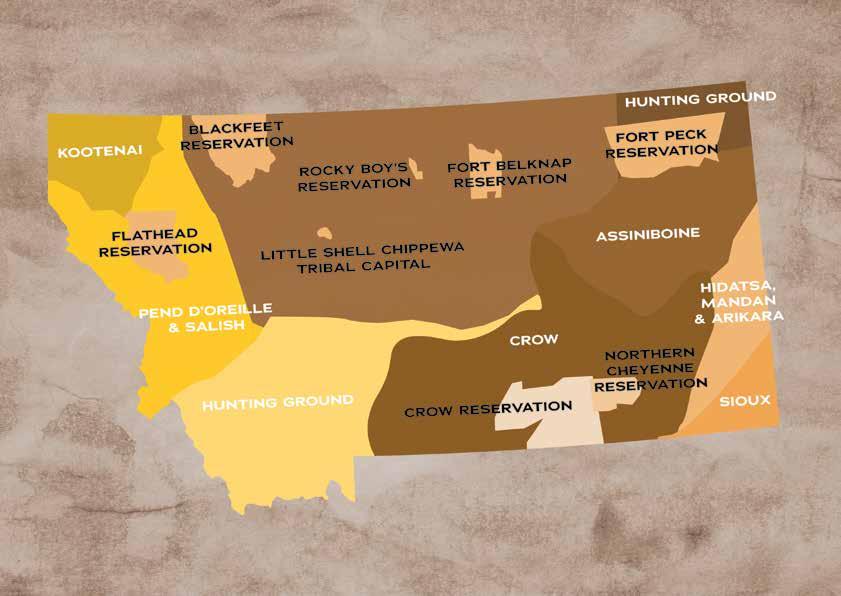

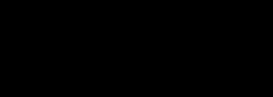

Kqyn Kuka: Montana’s first FWP tribal liaison

Scott Carney: Crafting stories as a tool of impact

Kadie Neuharth: The impact of one heart on another

OUTLAW

Tom Skerritt: A lifetime relationship with free-flowing waters

The Milky Way shines over Big Sky’s Lone Mountain.

The Milky Way shines over Big Sky’s Lone Mountain.

9

PHOTO BY ETHAN SCHUMACHER

MOUNTAIN MTOUTLAW.COM

OUTBOUND GALLERY

WARREN MILLER

Wise advice from the world's original ski bum p.26

ENVIRONMENT

KAITLYN FARRINGTON

Protecting our winters p. 36

CHARLIE GAILLARD

Prioritizing sustainability in cannabis growth p. 42

MATT SKOGLUND

Ranching for a new land ethic p. 45

STEVEN AMSTRUP AND DANIEL J. COX

Connecting Bozeman’s conservation community with the Arctic p. 54

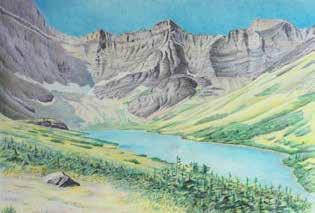

JONATHAN MARQUIS

A mission to visit and draw all of Montana’s glaciers p. 60

BRETT JENKS

Q&A with Rare CEO on initiating change for a healthier earth p. 67

INDUSTRY

CHRIS WALCH

Sparking a DEI movement in the ski industry p. 74

KRIS INMAN

A quest to empower women in STEM p. 80

DAVID AND CONNOR WALLACE

Tech to save water and simplify farming p. 84

BODE MILLER AND ANDY WIRTH Shaking up the ski industry p. 94

WADED CRUZADO AND LEON COSTELLO

‘Year of the Bobcat’ p. 102

YARROW KRANER

Everyone’s inner superhero p. 112

10 MOUNTAIN MTOUTLAW.COM

CULTURE FEATURED OUTLAW

GOV. DOUG BURGUM

Preserving Theodore Roosevelt’s legacy p. 118

HILAREE NELSON

Honoring the life of one of the greatest mountaineers p. 128

KQYN KUKA

Montana’s first FWP tribal liaison p. 134

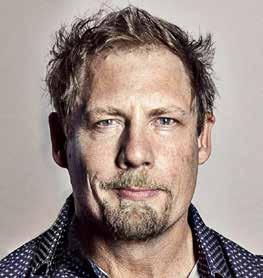

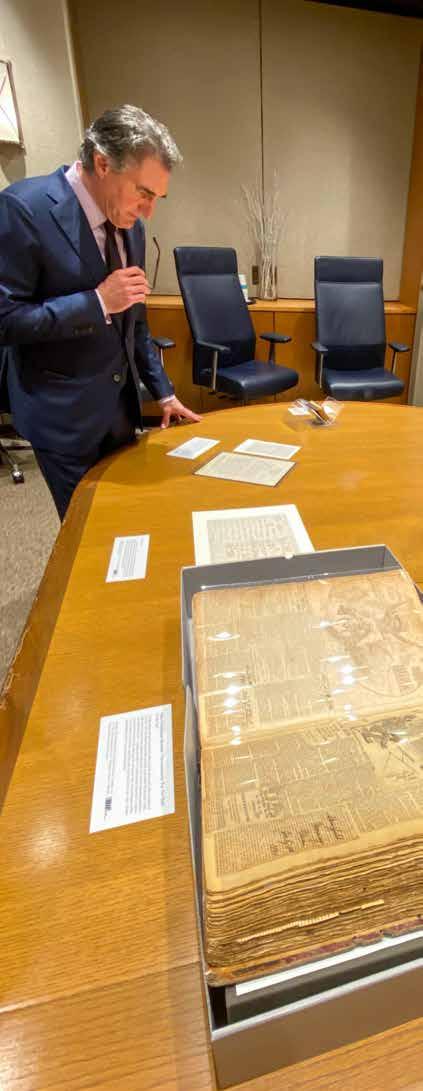

SCOTT CARNEY

Crafting stories as a tool of impact p. 140

KADIE

NEUHARTH

The impact of one heart on another p. 148

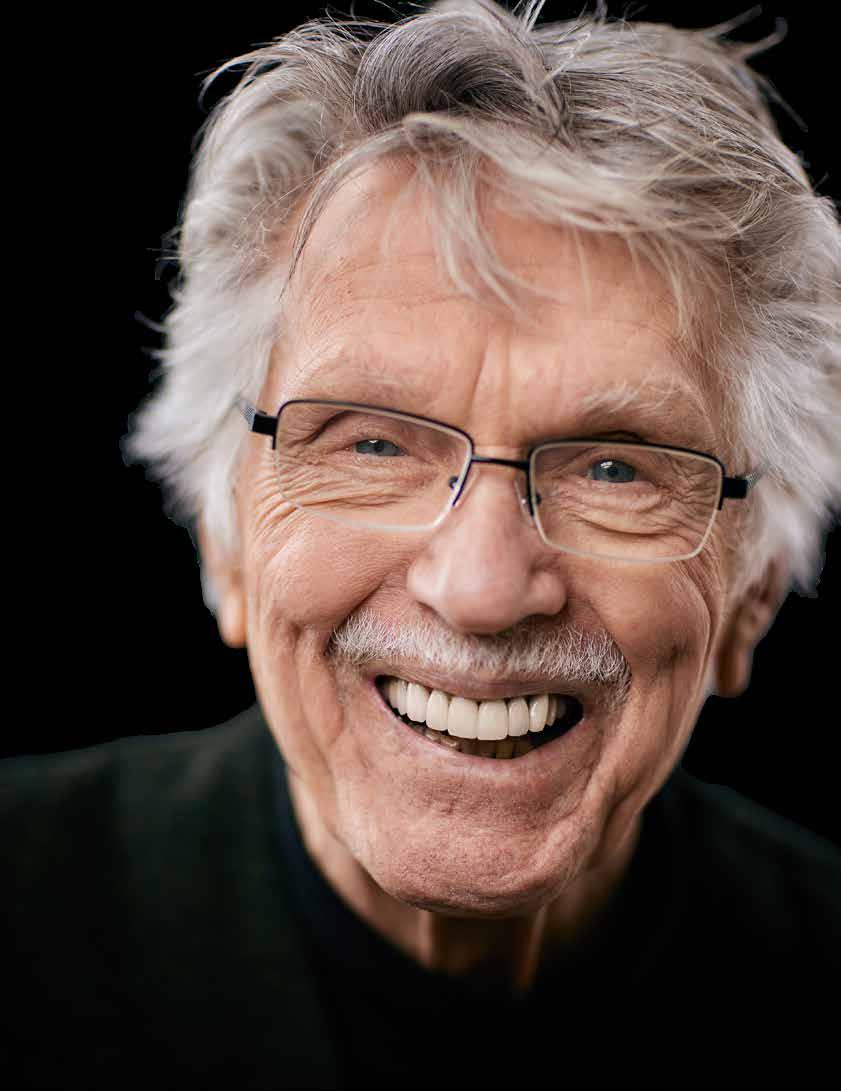

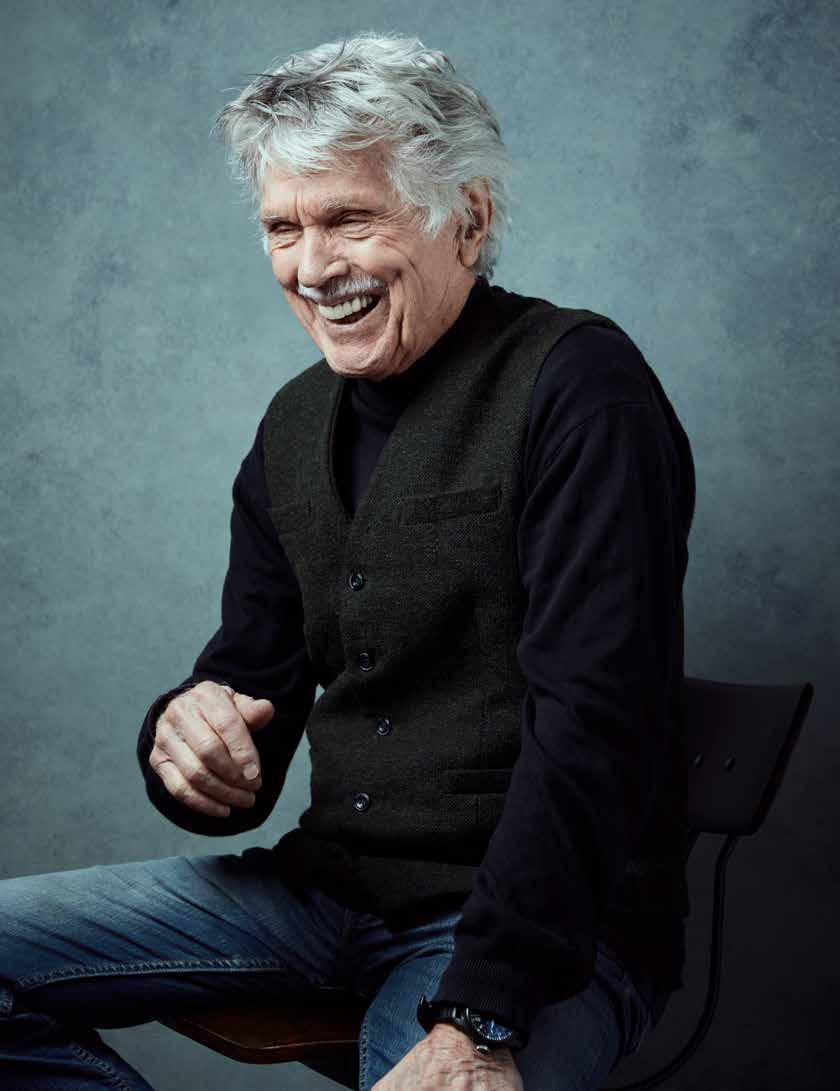

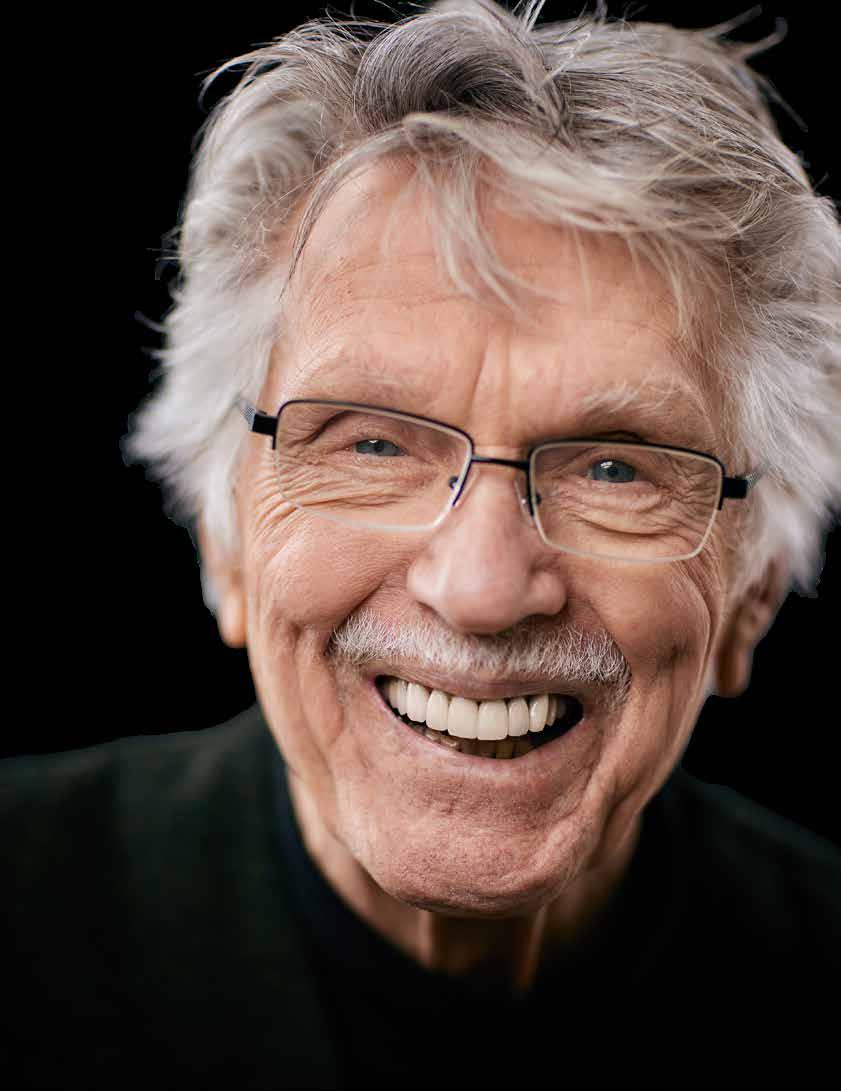

TOM SKERRITT

A lifetime relationship with free-flowing waters p. 156

Big Sky local Holden Samuels flies over the cornice on Dictator Chutes at Big Sky Resort. PHOTO BY ETHAN SCHUMACHER

Big Sky local Holden Samuels flies over the cornice on Dictator Chutes at Big Sky Resort. PHOTO BY ETHAN SCHUMACHER

11 MOUNTAIN MTOUTLAW.COM

FEATURED CONTRIBUTORS

Owned and published in Big Sky, Montana.

PUBLISHER

Eric Ladd

Eric Ladd

MANAGING EDITOR

WEB & DIGITAL

Hiller Higman

Julia Barton

Butler PRODUCER

Bella

Mira Brody

ASSISTANT EDITORS

Tucker Harris

Leslie Kilgore

Jason Bacaj

Jack Reaney

Carter Walker

GRAPHIC DESIGN & ART

PRODUCTION

Travis LaRiviere

ME Brown

Trista Hillman

Brooke Benson

Corey Ellbogen Beans

Michael Ruebusch

SALES & ADVERTISING

E.J. Daws

Ersin Ozer

Patrick Mahoney

Sophia Breyfogle

ACCOUNTING

Sara Sipe Taylor Erickson

CEO Megan Paulson

COO, VP FINANCE Treston Wold

DISTRIBUTION MANAGER Ennion Williams

Visit outlaw.partners to meet the entire Outlaw team.

BRIAN LADD

RICHARD FORBES

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

Sierra Cistone, Matt Crossman, Richard Forbes, Gabrielle Gasser, Brian Ladd, Clarise Larson, Alex Miller, Joseph O’Connor, Bay Stephens, Sophie Tsairis

CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS/ARTISTS

Tom Attwater, Perry Brown, Sierra Cistone, Daniel J. Cox, Hazel Cramer, Seth Dahl, Chris Douglas, Kelsey Dzintars, Richard Forbes, Gabrielle Gasser, Joshua R. Gatley, Ben Girardi, Adrian Sanchez-Gonzalez, Kelly Gorham, Jackie Jensen, Nick Kalisz, John Kelly, Steve Korn, Ken Lund, Fredrik Marmsater, Micheli Oliver, Dave Pecunies, Colter Peterson, Holly Pippel, Kathy Quigley, Micah Robin, Ethan Schumacher, Kim Spectre, Kene Sperry, Chris Wellhausen

Subscribe now at mtoutlaw.com/subscriptions.

Mountain Outlaw magazine is distributed to subscribers in all 50 states, including contracted placement in resorts and hotels across the West. Core distribution in the Northern Rockies includes Big Sky and Bozeman, Montana, as well as Jackson, Wyoming, and the four corners ofYellowstone National Park.

To advertise, contact Ersin Ozer at ersin@theoutlawpartners.com.

OUTLAW PARTNERS & Mountain Outlaw P.O. Box 160250, Big Sky, MT 59716 (406) 995-2055 • media@outlaw.partners

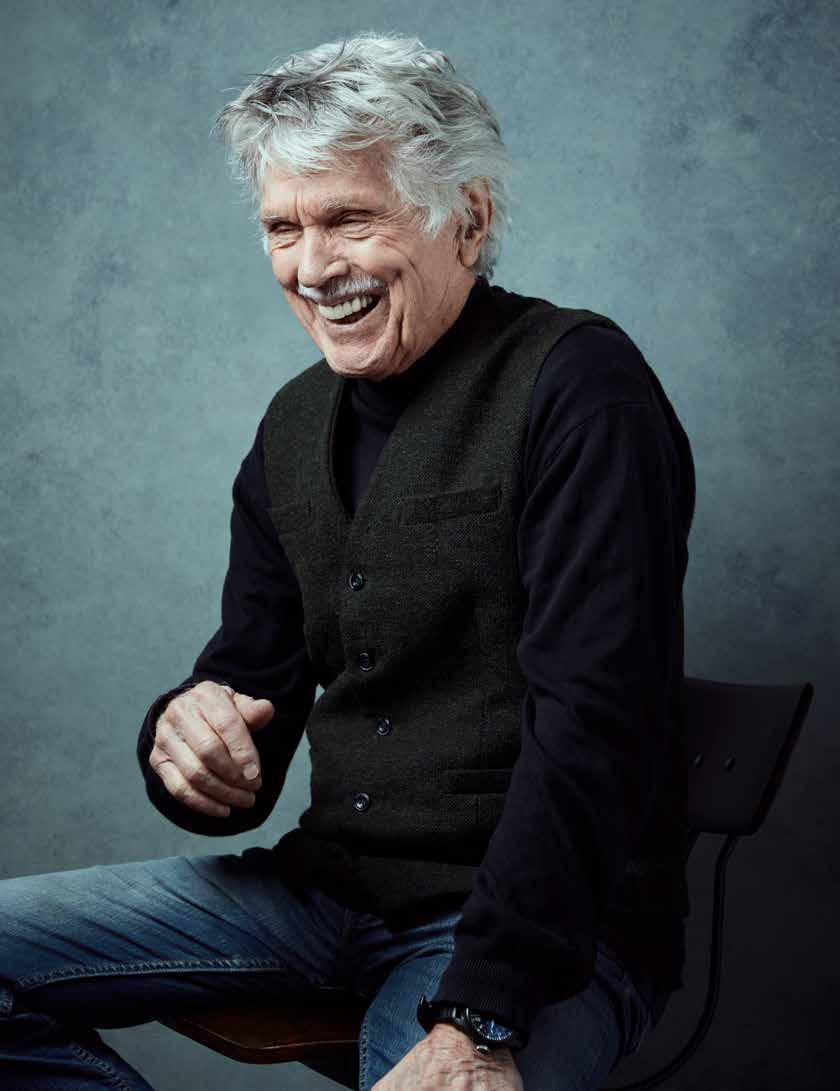

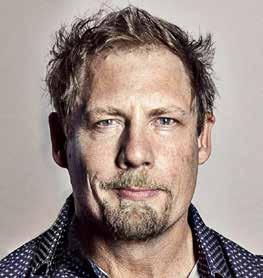

ON THE COVER: Actor Tom Skerritt is famous for many timeless roles, among them the Rev. Maclean in Robert Redford’s ARiverRunsThroughIt But now at 89 years old, he’s turning toward a new role—that of a conservationist. Read about Skerritt’s lifelong love for rivers and why he believes they deserve our engagement on p. 156. PHOTO BY STEVE KORN

While balancing the demands of raising his three children and running a team of real estate agents in Oregon, Brian Ladd is always looking to refuel with outside adventures. At Ladd's wedding, Eric showed a clip of A River Runs Through It, and the circle was completed when Ladd had the opportunity to sit down with Tom Skerritt for this issue’s feature article. The Rhythm of the River: Tom Skerritt reflects on a lifetime relationship with free-flowing waters, p. 156

Richard Forbes is a Montana-based outdoor guide and environmental journalist telling stories about the intersection between identity, the outdoors, mental health and climate change. He's currently working on a long-term project about the relationship between humans and the glaciers of Glacier National Park. When he remembers to slow down, he writes poetry and sits next to rivers. Witness: Jonathan Marquis draws connection between Montana’s glacial and human communities, p. 60

SOPHIE TSAIRIS

Sophie Tsairis is a freelance writer with a master’s in Environmental Science Journalism. Storytelling is her way of sharing the human experience and keeping curiosity alive. Nearly always in motion, writing and reading have always been an anchor for her hungry and restless spirit. Matt Skoglund’s Bison Ranch Pipe Dream: First-generation Montana ranchers write a new land ethic, p. 45

STEVE KORN

Steve Korn is a Seattle-based photographer who specializes in photographing interesting people from all walks of life. He is fascinated by what drives each of us and tries to convey those emotions and ideals in his work. Korn met Tom Skerritt in 2019 and photographed the portraits featured in this edition of Mountain Outlaw in spring of 2022. The Rhythm of the River: Tom Skerritt reflects on a lifetime relationship with free-flowing waters, p. 156

CHECK OUT THESE OTHER OUTLAW PUBLICATIONS: explorebigsky.com

© 2023 Mountain Outlaw Unauthorized reproduction prohibited

12 MOUNTAIN MTOUTLAW.COM

DESTINY IS A RIVER

This past summer I had the privilege of joining a Boundary Expeditions trip down the Middle Fork of the Salmon River for a story I wrote about New York Times bestselling author Scott Carney (p. 142). At our third night’s camp, I sat on the bank of the wild, free-flowing river and let the water rush over my feet. I considered the river as a metaphor for the journey we each take in life.

“We sit on the edge of the river and watch it carry all the things our lives can be,” I wrote in my journal. “As it tumbles over rocks and spills into channels, our potential fates will dwindle down to one destiny that waits for us at the end.”

Months later, Mountain Outlaw contributor Brian Ladd interviewed actor and conservationist Tom Skerritt, most famous for his role as the Reverand Maclean in the 1992 film A River Runs Through It (p. 156). Skerritt told Ladd when you dangle your feet in the river and let the water rush by, you feel the past, present and future. He said at age 89, he finally feels like he truly understands the famous line from A River Runs Through It: “Eventually all things merge into one and the river runs through it.” In the end, he suggests, everything that our lives are and everything they’ve been come together, and we all feed into the ocean.

In this special edition of Mountain Outlaw, we’re celebrating Humans of Impact by telling stories of individuals that have used their lives and their work to influence environment, industry and culture. These stories are a chance to roll up your pants and dangle your feet in the river; to experience the pasts,

presents and futures of these profound people and to feel how they’re connected. Eventually all things merge into one, and our fates bleed together for a collective impact on our communities and our world as a whole.

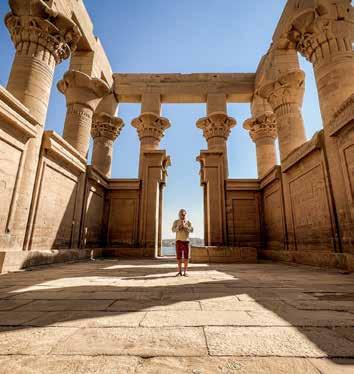

This magazine will take you from a ranch in the North Bridger Mountains in Montana, where a former Chicago lawyer is committing his life to promoting natural symbiosis on a bison ranch, to the depths of the Arctic, where a photographer and scientist are applying Bozeman, Montana’s conservation values to endangered polar bears. You’ll meet Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks’ first tribal liaison, who is rewriting a centuries-old story of tension and wildlife mismanagement. You’ll journey back in time with North Dakota Gov. Doug Burgum to Theodore Roosevelt’s Western rebirth. Just to name a few.

These stories are how we’ve chosen to fill the 25th edition of Mountain Outlaw. In every edition we’ve written, designed and printed, the common thread is connection, and people have always been at the heart of that. We live in a time of jarring divisiveness. I’m writing this letter on the heels of another election year, where candidates spent millions of dollars demonizing one another. We spend more time fighting each other than understanding each other.

Our hope is that by celebrating these Humans of Impact, we can be inspired by our neighbors. Let these stories cast ripples in your own river. Our lives can create impact for the whole system, because “eventually all things merge into one.”

Bella Butler Managing Editor

13 MOUNTAIN MTOUTLAW.COM

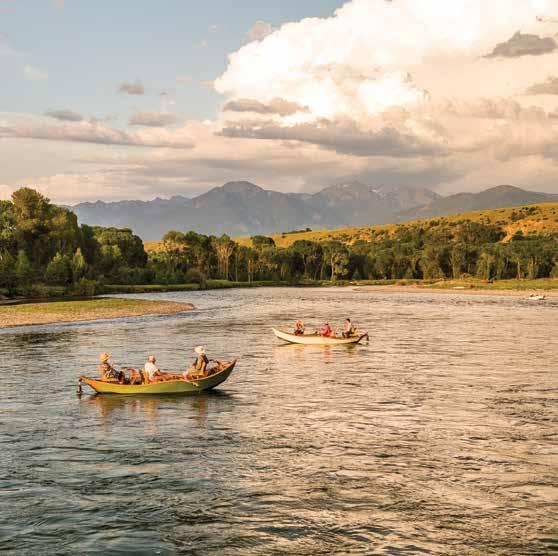

Fay Ranches has over 30 years of experience brokering the finest land assets from coast to coast. Through our dedication to family, investment value, sporting pursuits, and conservation, we have built a network of relationships that offer unparalleled reach and direct contact with the most qualified landowners and investors. If you are thinking of selling, buying, or just want to get our thoughts on the current real estate market, contact a member from our Bozeman office at your convenience.

WWW.FAYRANCHES.COM | 800.238.8616 | INFO@FAYRANCHES.COM DEEP CREEK RANCH | Livingston, MT $5,900,000 | 238 ± acres RIVERS EDGE RANCH | Melrose, MT $7,845,000 | 32 ± acres DEEP CREEK WILDLIFE SANCTUARY | Townsend, MT $7,995,000 | 968 ± acres ARROW RANCH | Wisdom, MT $38,514,500 | 14,982 ± acres

With views of all six surrounding mountain ranges, Six Range is a modern housing community that brings a Scandinavian design aesthetic to Bozeman.

Own your own home within Montana’s newest design-forward, outdoors-oriented neighborhood.

THE MOUNTAIN LIFESTYLE, REDESIGNED SIXRANGE.COM 406.577.8301 A PAINE GROUP DEVELOPMENT UNITS AVAILABLE NOW MOVE-IN-READY 2024

Teton Valley Rewards the Curious

There is so much to explore and enjoy in Teton Valley this winter.

Our remote, rural valley may take a little extra effort to navigate, but the rewards are great.

Winter is a celebrated and popular time of year in Teton Valley. Here are a few tips for navigating the snowy season,while being a great visitor:

• Be early, for everything. Whether it’s hitting the slopes at the resort or going out to eat, get there early and you’ll be amply rewarded.

• Be self-sufficient. Carry water, snacks, extra warm clothing, and first aid supplies on your adventures.

• Be prepared. Start at the Geo Center, Forest Service office, and local outdoor shops and load up on local intel for your winter adventure.

• Be patient, kind, and respectful of the people, animals, and ecosystem.

• Drive slowly. As we like to say, you didn’t come here to be in a hurry.

• Seek out local goods and be generous to the hardworking staff.

Enjoy your

visit.

Book your stay now!

CAMRIN DENGEL

Taking ACTION

Updates on issues facing the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem

In the summer of 2022, Mountain Outlaw published its first special edition, The Action Issue. In 172 pages, our troupe of writers and photographers told stories of adversity, action and actors from across the West, ending each piece with a call to action for our readers to engage with the issues and solutions of our region. Several months later, we’re bringing you updates from three of the stories as a reminder to stay engaged. The challenges our communities and environment face don’t disappear when the news cycle turns over. Stay active.

-The Editors

Sun sets over the upper Gallatin River near Big Sky, Montana. PHOTO BY MICAH ROBIN

18 MOUNTAIN MTOUTLAW.COM

Above: The cover of The Action Issue Mountain Outlaw summer 2022 edition featured a monarch butterfly. Like the “butterfly effect,” even the smallest action can have a massive impact. ILLUSTRATION BY KELSEY DZINTARS

SWIFT WATER

FIGHTING TO PROTECT MONTANA’S TREASURED RIVERS

Last summer, Mountain Outlaw contributor and Northern Rockies Director for American Rivers Scott Bosse personified the Gallatin River—first known by native tribes as the Cut-tuh-o'gwa, meaning “swift water”—in a piece by the same name, with a call to action to preserve the iconic Missouri River tributary.

Bosse asked readers to help protect the Gallatin and 19 other Montana rivers by reaching out to Montana Sen. Steve Daines and Rep. Matt Rosendale and requesting they support the Montana Headwaters Legacy Act. The proposed bill would protect 385 stream miles of 20 rivers by adding them to the National Wild and Scenic Rivers register. The proposed legislation is “truly made in Montana,” according to Bosse.

On June 7, 2022, one day before the The Action Issue hit stands, Daines spoke against the bill at a U.S. Senate hearing, citing letters of opposition from 170 residents and other Montana groups.

Bosse said he never heard Daines oppose the bill before that moment. Despite public support from 80 percent of Montanans, according to Bosse, the bill failed to reach a Senate Energy and National Resources Committee vote.

Bosse and Kristin Gardner,

chief executive and science officer of the Gallatin River Task Force, have held weekly strategy meetings since June with a group called Montanans for Healthy Rivers. The group has spoken with many stakeholders opposed to the bill, engaging in productive dialogue to reduce misinformation. Gardner told Mountain Outlaw that she sees broad, bipartisan support and it's hard to believe it won’t pass in the next congressional session. But without Daines’ support for the bill, it cannot reach a committee vote.

“A small handful of special interest groups have Sen. Daines’ ear on this issue, and that’s very disconcerting for us,” Bosse said. “We’ve done everything we can to build tremendous public support. The fate of this bill is in Sen. Daines' hands.”

As the 2022 election season will likely push the bill into 2023, Bosse stresses his original call to action: contact the office of Sen. Steve Daines at contact@stevedaines.com.

“When a senator can’t hear what Montanans are saying, Montanans need to speak up a little louder,” Bosse said.

-Jack Reaney

19 MOUNTAIN MTOUTLAW.COM

FLUID LANDSCAPE

CREATING SAFE PASSAGEWAYS FOR SOUTHWEST MONTANA WILDLIFE

Wildlife cannot and does not live exclusively within national parks, wrote Mountain Outlaw contributor Brigid Mander in her Action Issue story “Fluid Landscape,” but many visitors don’t understand just how much land wild animals need. Different herds of different species each need summer range, winter range and a navigable migration corridor between them. Yet in a time of sprawling regional development, human infrastructure such as roads, railroads and fences often pose as deathly barriers to these corridors.

Twenty-four percent of reported accidents on the Montana section of U.S. Highway 191 between Bozeman and West Yellowstone involve wildlife and many more animal collisions go unreported, according to a 2020 Montana Department of Transportation study. In her story, Mander wrote that migrationoriented solutions including overpasses and underpasses can lower roadkill events by 90 percent.

The Center for Large Landscape Conservation is working to plan for safer passageways. In her piece, Mander asked readers to become citizen scientists by

recording observations of wildlife, both alive and roadkill. With enough data points, the CLLC has more information it can use to affect change.

In a recent reflection with Mountain Outlaw, Mander said that upgrading migration-friendly roadway infrastructure is a slow-moving, “glacial” process. She sees more urgency for human needs such as bike lanes. That being said, she’s seeing change near Jackson, Wyoming.

“There's more awareness, and highway departments are slowly but surely responding,” she said.

As this awareness spreads, Mander hopes more realtors and developers will sell the importance of minimizing human impact on wildlife, steering buyers away from private fences and encouraging native sagebrush instead of turf landscaping.

“We have proven solutions. It’s just about putting them in play,” Mander said.

The very citizen science Mander asked readers to engage in is also helping protect wildlife crossing the highly dangerous Montana Highway 64 and U.S. Highway 191 near Big Sky. The CLLC launched a wildlife reporting app

in spring 2021.

“It was slow to start,” said CLLC road ecologist Elizabeth Fairbank. “But it’s getting more traction. We are super thankful for all the citizens that contributed to that dataset.”

In October of 2022, Fairbank and the CLLC formed a committee including Montana State University’s Western Transportation Institute; a biologist; a Montana Department of Transportation engineer; a transportation liaison with Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks; the U.S. Forest Service; and the National Park Service.

With hundreds of citizen reports and other animal data including aquatic life, the committee is creating recommendations for this pair of Montana highways, which intersect the fluid landscape of Yellowstone migration corridors.

The full report will be available in early 2023, and Fairbank said it might be the first time such a holistic dataset has been used to inform a traffic study the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. To learn more and get involved, visit largelandscapes.org.

Reaney

-Jack

In November of 2022, a series of elk and deer collisions on U.S. Highway 191 prompted public outcry. The stretch of road sees a high volume of commuters between Bozeman and Big Sky and is a major migratory corridor for wildlife.

20 MOUNTAIN MTOUTLAW.COM

PHOTO BY HOLLY PIPPEL

In the Action Issue story “Graceful Endurance,” Mountain Outlaw

Steven Hawley wrote that wild Chinook salmon are circling the extinction drain. A salmon’s natural pilgrimage to the ocean used to take two weeks, but now due to barriers including a 500-mile-long series of dams and reservoirs, their migration takes two months as they navigate the Columbia River Basin across Idaho, Washington and Oregon where the Salmon River meets the Snake River. During that extended time, fish are vulnerable to predators and expend more energy without natural river flow.

“There is no economic activity that involves a dammed river that cannot be accomplished another way,” Hawley wrote. “Wild Chinook salmon in the Middle Fork, by contrast, have only one way.” He called for readers to send an email with comments to the White House Council on Environmental Quality. Since March 2022, the council has held a dedicated inbox for comments on the Columbia River Basin.

Kyle Smith, Snake River director with American Rivers, spoke with Mountain Outlaw about an August 2022 report

released by Washington Gov. Jay Inslee and Washington Sen. Patty Murray.

The Murray-Inslee Report laid out an estimated cost between $10.7 billion and $33 billion to remove dams from the lower Snake River and replace the services they provide. The report does in fact recommend removing dams including Ice Harbor, Lower Monumental, Little Goose and Lower Granite, but only if the benefits of those dams—including hydroelectric energy and irrigation supply—can be replaced.

“[$10.7 to $33 billion] is a lot, but there’s also a lot of money spent maintaining the dams,” Smith said, pointing to nearly $20 billion spent on a 40-year salmon recovery program which has not made significant progress on recovering Snake River Basin populations.

Hawley spoke with Mountain Outlaw in November of 2022 and commented on the Murray-Inslee Report.

“That report can’t really be characterized by anything other than a disappointment,” Hawley said. “It did what politicians in the region have been doing for 40 years, by saying, ‘we have to figure this out—but not right now.’”

Hawley believes the report is shy for

political reasons; the only way to motivate action, he suggests, is for voters in Washington, Idaho and Oregon to demonstrate overwhelming support for dam removal, which “provides cover” for politicians against the risk of taking action that could hurt their favorability, according to Hawley.

The Snake River makes up roughly one-third of the total water of the Columbia River Basin but represents about half of the fish due to “incredible habitat quality,” Smith said. He added the Snake River provides the best chance for salmon recovery in the lower 48.

If the dams are not removed, though, Smith expects to see only two more generations of wild salmon, lasting five years each. To recover population, four young salmon need to return from their migration to the ocean for every spawning adult. The current smolt-to-adult ratio is less than one, a stat that points to a predicted salmon extinction around 2030.

To get involved, contact the Idaho State Legislature at legislature.idaho.gov/ senate.

-Jack Reaney

GRACEFUL ENDURANCE POLITICAL HESITATION BEHIND FIGHTING SALMON EXTINCTION The Middle Fork of the Salmon River sits in the remote and rugged mountains and rivers of Central Idaho. The river’s Chinook salmon population is one of only a few remaining populations in the United States that have not been genetically altered by hatchery fish. OUTLAW PARTNERS PHOTO 21 MOUNTAIN MTOUTLAW.COM

JOIN US THIS SUMM ER FOR BIG SKY’S BIGGEST WEEK, JULY 14 - 22 RODEO | STREET DANCE | MUTTON BUSTIN’ | BINGO | PBR GOLF TOURNAMENT T I C K E T S O N S A L E MARCH 1 BIGSKYPBR.COM july 20-22 2023

Building and supporting communities

SCANTOLEARN M OREANDDONAT E

Donating to the Khumbu Climbing Center supports the local community and trains sherpas in first aid, rescue, and modern mountaineering.

“We are proud of our involvement in building the KCC in the mountains of Nepal, below Mount Everest. It was a monumental, multi year effort by many people to bring the school to fruition. Its remote location, 100 miles from the nearest road, in the village of Phortse at 12,500’ in elevation, made for some unique challenges. Its quite the school!”

- Chris Lohss FOUNDER AND CEO OF LOHSS CONSTRUCTION

we care about.

HEYBEAR.COM IS YOUR RESOURCE • Access Bear Education Safety Tips • Give Back to Support Bear Habitat • Shop Apparel & Gear

406-599-1990 CortneyAndersen.com

26 MOUNTAIN / MTOUTLAW.COM

MTOUTLAW.COM

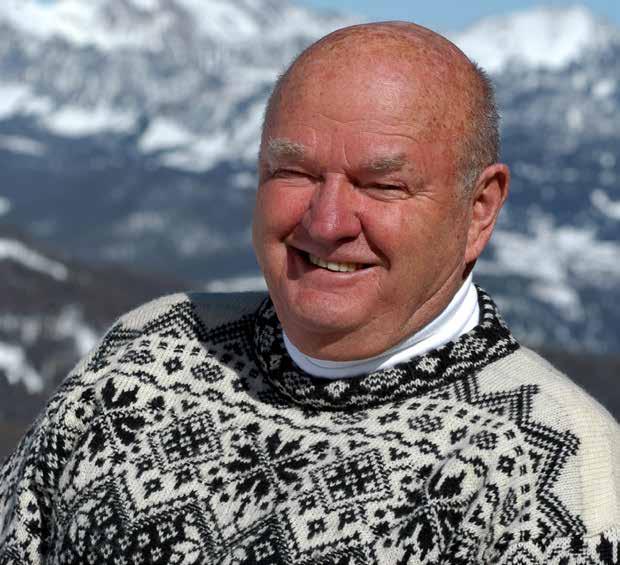

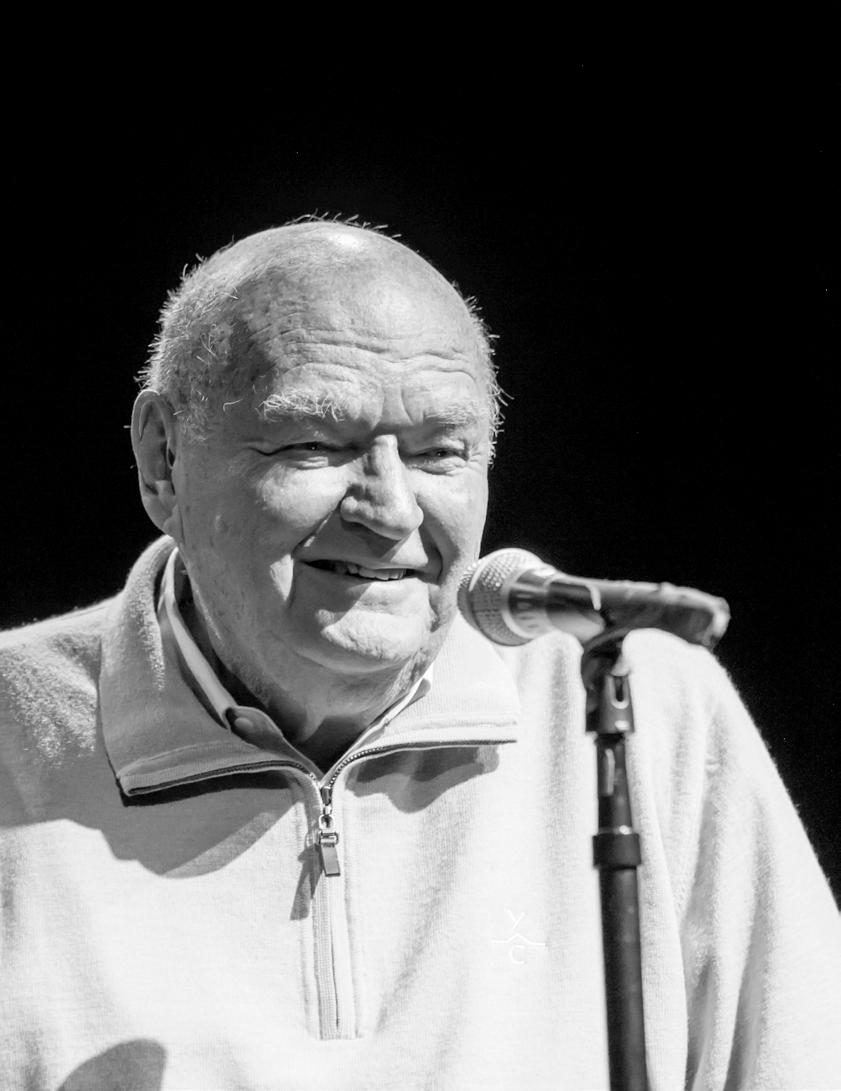

Photos Courtesy of Travis Anderson

ith more than 500 films that spanned a 50-year career, Miller influenced generations to follow their dreams and live their best life on the mountain. But Miller leaves behind another legacy, one that arguably transcends the impact of any film. In the resort town of Big Sky, Montana, Miller was a community member. He was our neighbor.

Miller and his wife, Laurie, spent half of each year in Big Sky, and Miller served as the director of skiing for the Yellowstone Club. His name cements his local legacy at the Yellowstone Club’s Warren Miller Lodge, as well as at the community’s renowned Warren Miller Performing Arts Center.

More than this, many in the community recounted Miller as a friend. This gallery was compiled in honor of our neighbor, Warren Miller, so that we might so be inspired to contribute our best selves to our communities by living our own lives to the fullest. For we ought not forget his famously recounted wisdom:

Left/Cover: All smiles for Warren Miller while filming in Montana.

Top: Miller with extreme skiing pioneer Dan Egan. Middle: Pro skier Scot Schmidt, Miller and GoPro founder Nick Woodman at the Yellowstone Club. PHOTO COURTESY OF SCOT SCHMIDT

Left/Cover: All smiles for Warren Miller while filming in Montana.

Top: Miller with extreme skiing pioneer Dan Egan. Middle: Pro skier Scot Schmidt, Miller and GoPro founder Nick Woodman at the Yellowstone Club. PHOTO COURTESY OF SCOT SCHMIDT

MOUNTAIN MTOUTLAW.COM

Bottom: Miller directing, filming and skiing with friends and colleagues at the Yellowstone Club,

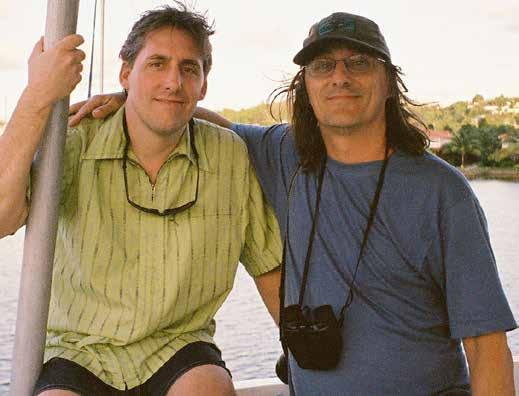

Above: Photographer Travis Anderson poses with Miller in Miller’s Big Sky home.

Above: Photographer Travis Anderson poses with Miller in Miller’s Big Sky home.

28 MOUNTAIN MTOUTLAW.COM

Right: Miller getting some Montana powder turns.

29 MOUNTAIN MTOUTLAW.COM

Top Right: Miller films with Gary Nate in Big Sky on a bluebird day with Sphinx Mountain in the background.

Left Bottom: Miller and Scot Schmidt enjoying some good conversation in between turns at the Yellowstone Club.

Bottom Right: Filming at the Yellowstone Club, with Outlaw Partners' Eric Ladd.

Opposite: With more than 500 films that spanned a 50-year career, Miller influenced generations to follow their dreams and live their best life on the mountain.

30 MOUNTAIN MTOUTLAW.COM

31 MOUNTAIN MTOUTLAW.COM

Top: Filming, skiing and corduroy snow with Miller and friends in Big Sky, Montana.

Right: The Warren Miller Performing Arts Center helps Miller’s legacy and artistic values live on in perpetuity within the Big Sky community. OUTLAW PARTNERS PHOTO

Opposite Page: Miller shares insights and stories at the Warren Miller Performing Arts Center. PHOTO BY KENE SPERRY, COURTESY OF WARREN MILLER PERFORMING ARTS CENTER

32 MOUNTAIN MTOUTLAW.COM

33 MOUNTAIN MTOUTLAW.COM

A Specialist Approach to Risk

We See Risk Through Your Lens

When you’re facing the most pressing business challenges, maximizing your success starts with the right partner.

As a top national specialty insurance broker, with tailored services and experts in over 30 practices, we see risk through your lens. By understanding your industry, business goals and market trends, we deliver personalized, comprehensive risk advice to prepare for today and plan for tomorrow.

Face the future with confidence.

Yale Rosen | Risk Advisor yrosen@risk-strategies.com

Tom Beattie | Managing Partner tbeattie@ibeattie.com

R is k Strategies . A S p ecia list A pp roa ch to R is k . Prope r t y & C asualt y | Employe e B e nefit s | Private Clie nt Se r vices

risk-strategies.com/about

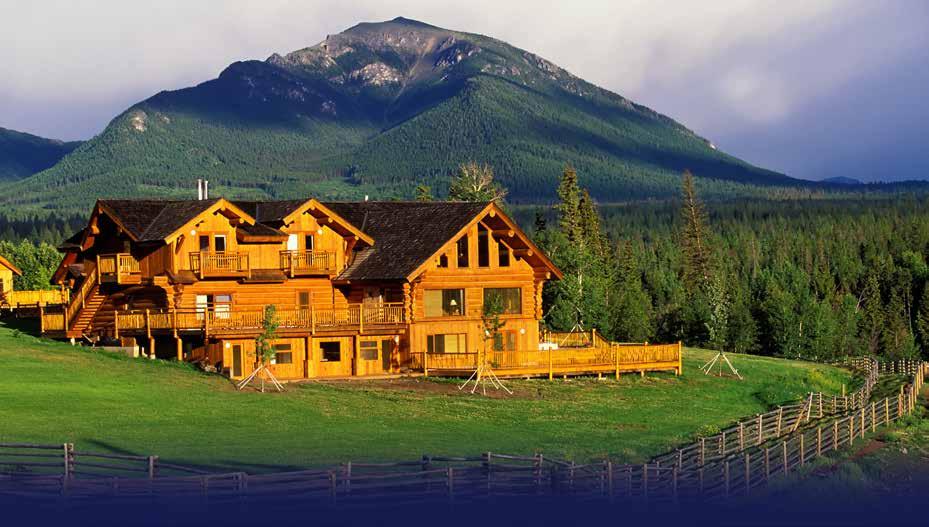

YOU DREAM. WE BUILD.

Inspired by the dynamic landscape of the Rocky Mountain West, we bring the visions of owners, architects and craftsmen together to create exceptional handcrafted custom homes. Teton Heritage Builders integrates the quintessential elements of the regional palette –stone, timber, log, glass and steel – to craft high-quality homes that reflect the character of their distinctive surroundings. At the intersection of rugged wilderness, rustic aesthetics and timeless elegance, building unique homes with a deep connection to place is our passion.

BIG SKY | JACKSON

Visit tetonheritagebuilders.com to start building your dream.

36 MOUNTAIN MTOUTLAW.COM

Former Olympian Kaitlyn Farrington carves a line in Argentina. PHOTO BY BEN GIRARDI

BY BELLA BUTLER

aitlyn Farrington picks up a rock and flings it into the Whitefish River. A smile cracks on her face as the stone skips, wrinkling the reflection of golden cottonwoods and willows on the water. She’s on a walk in Riverside Park in Whitefish, Montana, her home for five years now. She stands at the very edge of the river, where several feet of dry beach reveal the high-water mark from a dramatic early-season flood.

“It’s crazy how low the water is,” she observes, picking up another rock.

Dressed in Vans sneakers and a black T-shirt, skipping rocks on the beach, it’s easy to forget that Farrington became a household name across the U.S. when she unexpectedly won gold in the 2014 Sochi Olympics in the women’s halfpipe snowboarding event.

In many ways, her life now is worlds away from what it looked like then. Farrington lives a few blocks from downtown Whitefish in a little yellow house she owns with her partner, professional skier Chris Logan. She has a garden where she grows tomatoes and squash, and a garage where she sometimes makes candles—one of her newer hobbies. Sometimes she and a few of her girlfriends will ride their motor scooters to the nearby state park (they call themselves the meepmeep crew) to swim in the lake.

Not long after her success in Sochi, Farrington suffered an injury that revealed a lifelong spinal condition and ended her competing career. She still snowboards, guiding even in Argentina during part of the Montana summer, but she’s what she and her doctors call a “grounded snowboarder,” meaning the athlete that made a name for herself throwing recordbreaking flips and spins can’t leave the ground on her board.

Even in this new chapter, scraps of Farrington’s accoladed history stick to the page: the ample stock of snowboards from her longtime sponsor, Gnu, stored in the garage rafters; a collection of international pins traded with other athletes during the Sochi Olympics resting on a side table in her house; her gold medal, tucked between piles of clothes in her bedroom closet.

With these vestiges as a reminder, this athlete begins the next part of her story—a fight for the planet.

Farrington is one of more than 200 professional athletes that make up the athlete alliance for Protect Our Winters, a nonprofit founded in 2007 by pro snowboarder Jeremy Jones with a mission of mobilizing the outdoor community to act against climate change.

When discussing climate change herself, Farrington speaks in anecdotes.

“I always go back to my halfpipe days; when I feel like I first saw it was the [2010] Vancouver Olympics,” she said. “They put hay bales to make a halfpipe. And the snow was really bad in Vancouver that year because it was so warm, and they had tubing coming down through the center of the pipe to drain the water because the snow was melting so fast.” Fast-forward two years to a test event in Sochi, Russia, and Farrington remembers most of the events being canceled when there wasn’t enough snow.

These first-hand accounts of climate change are part of what make the athlete alliance an effective tool in POW’s work, according to Jones. When the mountains are the stage for your career, you get an intimate look at how quickly winters are changing.

“Real, tangible stories I think are important to bring vibrance to the issue,” Jones said.

In recent years, POW’s focus has been heavily anchored in politics. In 2022, for example, the organization ran several campaigns to inspire voter turnout, including a touring film festival called Stoke the Vote, and a Run to Vote campaign in partnership with exercise tracking app Strava that drove more than 25,000 people to run or cycle to the polls.

POW has also established somewhat of a lobbyist role for itself in Washington D.C. Jones has testified before Congress numerous times on behalf of legislation dedicated to climate action, and the nonprofit frequently sends representatives from its athlete alliance to Capitol Hill to advocate on a more personal level with senators and representatives. Farrington has traveled to D.C. on two such trips with POW.

Most recently, she joined a cohort of Olympians from POW’s crew on a lobbying mission to advocate for the Inflation Reduction Act, a more-than $700 billion federal investment that makes combating climate change a top line item with $369 billion designated for clean energy, clean transportation and green technology. President Joe Biden signed the bill into law on Aug. 16, 2022.

Farrington said these trips to D.C. are an opportunity to connect with politicians through storytelling. As a mountain athlete, she’s borne witness to climate change; this is her chance to testify.

Although her name is an asset in getting politicians’ attention, Farrington has found that she’s made the biggest strides in some of these meetings by identifying with them as everyday people. POW doesn’t work in an echo chamber, Far-

>> 37 MOUNTAIN MTOUTLAW.COM

rington said. While many of the people with whom she’s met were on the fence, or even averse to the legislation she was advocating for, the hope is that they find common ground over their shared love for the outdoors. That love is a powerful catalyst for conversation.

Farrington lives in Montana now and Utah before that, but she grew up on a cattle ranch south of Sun Valley, Idaho, in a little town called Bellevue— or as Farrington calls it, “the boonies.” Despite their remoteness, skiing was a huge part of the Farrington family—she describes her parents as “ski bums,” who got her and her sister into the sport at a young age.

“They both worked on the ski hill for the winters just so we could get family passes and be able to afford to be skiing every weekend,” she said.

Farrington switched to snowboarding when she was around 12 and started

competing at 14.

“To pay for my snowboarding, we'd load a cow up on, I think, Wednesdays and take it to the cattle sale, and that cow’s profit was my way of traveling to these different contests [on the weekends] and kind of funding my snowboarding,” she said.

Even though Sun Valley didn’t have a halfpipe or terrain park, Farrington started competing in slope style and halfpipe, taking all the practice she could get at other venues. And she got good.

The U.S. Olympic team picked Farrington up as a rookie when she was 17.

“That was kind of my first moment of realizing that I could make this a career,” Farrington said. And she did.

Farrington moved to Salt Lake City in 2008 and followed winter elsewhere throughout the year to train. After coming up short of qualifying for the 2010 Olympics in Vancouver, Farrington qualified for the 2014 Olympics in Sochi. She wasn’t expected to win, but the young rookie from rural Idaho was on fire.

“We always say as an athlete you have your on and off days, and that day happened to be one of my best days and

board. And they did—Farrington received a score of 91.75, beating the former women’s halfpipe gold medalist by a quarter of a point.

When she pulls her medal out now from the shelf in her closet, it’s slightly tarnished, but its weight still carries the grandeur of that moment for Farrington, and for the country she was representing. It’s a stature that she’s still reminded of when she dons the medal on Capitol Hill and tells the story of that winning run.

“I like to think of my Olympic time as my past life,” she said. “And so it's kind of funny when I have to talk about it again, because it's not something I talk about that often. And so going to D.C., it's like going back in time and reliving that surreal day, and to be able to share my story and then talk about something bigger that I'm passionate about now kind of makes it's another surreal feeling.”

While her rural Idaho upbringing and love for fishing helps level her with politicians, it’s her athletic clout that earns her a seat at the table. Jones said next to their stories, the athlete’s platforms are the power of the athlete alliance.

I was on that day,” she said. Farrington cruised through her winning run with apparent ease and the confidence of a 24-year-old who knew she might’ve just made history.

“I will be shocked if the judges don’t put her into the lead by virtue of that nonstop insanity,” one NBC announcer said as Farrington clicked out of her

“Those gold medals just unlock the doors to Congress like nothing else does,” he said. “And we’ve seen it time and again because she's an American hero and our lawmakers totally react to that. And nobody's more powerful than these people that represent our country on the global stage and succeed. And so yes, they unlock doors for us that we otherwise couldn't know.”

Farrington’s success has also afforded her a platform with perhaps more weight than even a gold medal: a robust social media audience. Farrington has nearly 20,000 followers on Twitter and another nearly 42,000 followers on Instagram. POW launched before most

Farrington meets with Sen. Michael Bennett on a trip to Washington, D.C. to advocate for climate legislation in April 2022.

PHOTO BY MICHELI OLIVER

/ PROTECT OUR WINTERS

38 MOUNTAIN MTOUTLAW.COM

“Those gold medals just unlock the doors to Congress like nothing else. And we’ve seen it time and again because [Farrington is] an American hero and our lawmakers really react to that.” - Jeremy Jones

social media even existed, Jones said, but POW’s athletes’ accounts have allowed the organization to begin quantifying its impact. With so many big names on their alliance—some with hundreds of thousands of followers—their reach is extensive. Farrington said she’s proud to be a part of that.

Though her Olympic days are behind her, Farrington has continued to stoke her love affair with snowboarding, and by proxy, with winter. For 10 years, from age 17 until she moved to Montana, she chased snow year-round, living in a perpetual season of white.

“I don't think I could not have winter as … a part of my life,” she said. “… I love snowboarding, I like powder, and so it just comes with the territory.”

Back on the banks of the Whitefish, she skips another rock and turns on her heels to leave the park. Dry leaves crunch beneath her feet, a hint that winter is coming. The season she

tethered so much of her life to plays a different role for her now; no longer the foundation for her career, but perhaps something even bigger. The POW logo on her black t-shirt is a reminder that while no longer riding for the U.S., she’s playing for a different team now: that she’s devoting her story and her honors to protecting our winters.

Bella Butler is the managing editor for Mountain Outlaw.

Top: Farrington won gold at the 2014 Sochi Olympics after receiving a score of 91.75, beating the former women’s halfpipe gold medalist by a quarter of a point.

PHOTO BY CHRIS WELLHAUSEN

Left: The retired competitive border-turned-climate advocate smiles for a portrait in her home of Whitefish, Montana. PHOTO BY HAZEL CRAMER

39 MOUNTAIN MTOUTLAW.COM

“I don’t think I could not have winter as … a part of my life … I love snowboarding, I like powder, and so it just comes with the territory.” - Kaitlyn Farrington

to

12 luxury residences located in Bozeman’s vibrant and historic Northeast neighborhood, only four blocks from downtown and 10 minutes from BZN Yellowstone International Airport.

BESPOKE LIVING IN DOWNTOWN BOZEMAN Scanhere

learnmore!

MEDICINE GROWING the

LPC focuses on sustainable and organic partnerships

By Tucker Harris

In late October, Lone Peak Cannabis Co. Owner Charlie Gaillard walks through rows of healthy cannabis plants at Collective Elevation’s grow facility outside of Bozeman. He stops to gaze at the forming flower buds inside the large, sun-filled greenhouse.

Adam Arnold, co-owner of Collective Elevation, leads the way, explaining the process of overseeing their state-of-the-art facility and living soil growing processes over the roar of fans and the buzz of LED light fixtures, all hard at work perfectly maintaining the temperature, humidity and sunlight needed for his flowers to grow.

Collective Elevation is Montana’s largest living soil cannabis grow facility and uses top-tier technology alongside classic and natural growing methods. LPC, Big Sky’s local cannabis provider, partners with brands like Collective Elective because they believe in their mission, strategy and methods.

“The effects of cannabis grown in a sustainable, organic way is two-fold: better for the environment and better for the consumer, period,” Gaillard says. “That’s our goal: supply the consumer with the best products available and the rest will take care of itself.”

LPC got its start back in 2010 as a medicinal cannabis company.

“I really looked at it as an adventure of coming to Montana,

Sponsored content

Owner of Lone Peak Cannabis Co. Charlie Gaillard stands in the rows of cannabis plants on a tour of Collective Elevation’s grow facility.

PHOTO BY TUCKER HARRIS

42 MOUNTAIN MTOUTLAW.COM

in addition to an exciting new venture of doing something I really love to do, which is grow marijuana,” he says. “It was an opportunity I could not pass up.”

Starting as a medical-only company is what prompted LPC to get into living soil and try to grow the plant in an all-natural environment. For Gaillard, sustainable growing practices are key.

Using living soil and sunlight means developing a complete bio-integration. Collective Elevation cultivates massive colonies of microbes, worms and beneficial insects along with cover crops like native clover, marigolds, onions and other herbs.

“The alternative, these bottle nutes that people use, it produces a fine product, but it's not as good as plants grown in living soil,” he says. “The best medicine comes from the plant producing its compounds through a natural selective method.”

Almost 14 years later, LPC, under the leadership of Gaillard, has expanded from the small ski town of Big Sky to three additional locations in Bozeman, Ennis and West Yellowstone.

Now, LPC’s goal is to establish itself as a top cannabis company in the industry by carrying vendors whose products focus on organic and sustainable growing practices. Gaillard wants his consumers to have the absolute best selection of products all in one place, he says.

“We're still going to produce our brand of marijuana, but we're very much interested in carrying folks like Collective Elevation.” Gaillard says. “We're constantly searching the marketplace to find companies that are focused on living soil and focused on growing the best plant you can find.”

Today LPC has strong relationships with the top growers and suppliers of edibles in the state, carrying vendor products from: MT Kush, Collective Elevation, Sacred Sun, In the Trees, Silverleaf, Triggers Relief, Cold Smoke Organics, Groove Solventless, High Road Edibles, WANA, The Clear, Sinful Beverages, Huckleberry Farms and Dancing Goat Gardens.

Gaillard looks to continue to develop relationships with these vendors as well as personally seek out additional partners who are focused on the environment and producing the best possible product. He believes this selective partnership choice is one of the main factors that sets LPC apart from competition.

"It’s our commitment to provide the consumer with a truly all-natural,

organic product, from the flower grown in living soil to the edibles made with a full-spectrum oil,” he says. “In my opinion, the effect the consumer gets is superior, more complex and an overall better feeling than any other products on the market.”

Gaillard’s adventure to Montana back in 2010 has enabled him to continue cultivating his passion in the cannabis industry. He respects the work others in the industry are doing to create top-of-the line products that he can share with his customers.

“LPC is now a company that has established itself as one of the go-to companies in the cannabis industry,” he says. “We supply the best products from the top producers of organic products in the state.”

Browse and order online LPC’s selection of organic, sustainable and top-of-the line products at lonepeakcannabiscompany.com/.

Tucker Harris is the marketing and events coordinator at Outlaw Partners and assistant editor for Mountain Outlaw magazine.

NACS T O VISITTHE WEBSITE

43 MOUNTAIN MTOUTLAW.COM

LPC partners with Collective Elevation because of their sustainable, organic practices. Collective Elevation is the largest living soil cannabis grow facility in the state of Montana. PHOTO BY TUCKER HARRIS

Order Online Pick Up At Your Favorite Location: Big Sky | Bozeman | West Yellowstone | Ennis Delivery Now Available In Big Sky LONEPEAKCANNABISCOMPANY.COM M o n t a n a ’ s f i n e s t p r o d u c t s u n d e r o n e r

f Order o n l i ne here!

o o

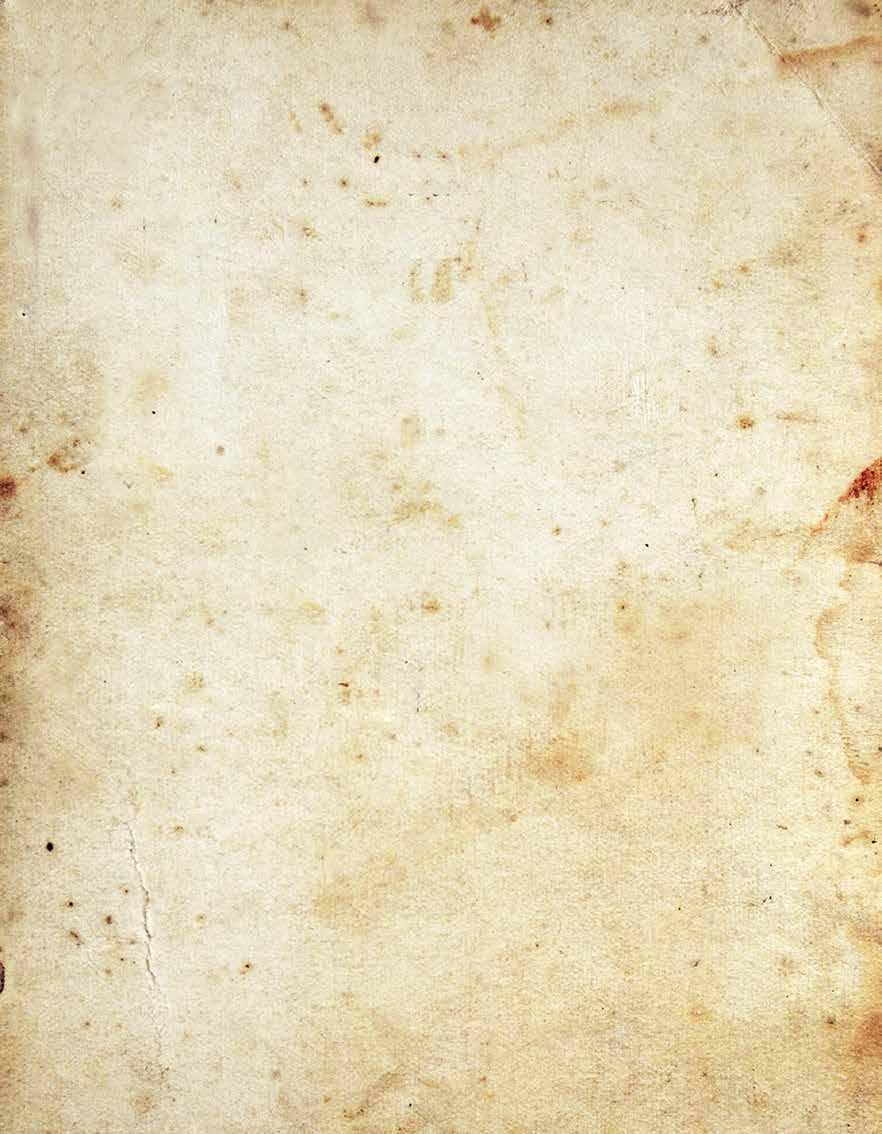

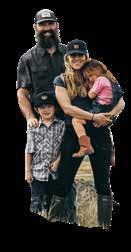

hecking on his bison herd as he does most days in one way or another, Matt Skoglund crunches through frozen snow and mud from this season's first winter storm. The sun will soften the wet ground into a slick clay in a few short hours, making it difficult to maneuver on foot or by truck. The aroma of sagebrush hangs in the air, and the bison are fully immersed in grazing fresh pasture, unphased by the layer of frost sheeting their backs, nor by Matt's presence. They acknowledge him with a snort and a disinterested glance before lowering their heads. Something spooks the herd in the distance, and in an instant, the stillness is shattered; the earth shakes as the hooves of one-ton masses of muscle trample the ground.

On the western edge of the Shields Valley, cradled between the Crazy Mountains and the Bridger Range, these bison roam 1,270 acres of biodiverse grasses, forbs, and sagebrush—a combination of the land owned by the Skoglunds, and pastures leased from their neighbors.

They breed on their own, calve on their own, and need no outside protection from predators. Pre-dating the Ice Age, they are built to endure Montana's often inclement and volatile climate.

First-generation ranchers with no previous experience in agriculture, Matt and Sarah Skoglund started North Bridger Bison in 2018, raising, field-harvesting and selling bison meat directly to consumers. Matt's coarse, weathered beard is a constant reminder that he traded a suit, tie and clean-shaven face for a life of unrelenting weather, a steep learning curve and occasionally getting too close for comfort to one of the greatest icons of the West. He wouldn't take any of it back, nor will he shave his beard. All the big risks and hard work have led to this: 150 head of bison and 791 acres of healthy, biodiverse, prime wildlife habitat—protected from development in perpetuity.

The couple moved to Montana from Chicago in 2008. In their previous lives, Matt was a lawyer, spend-

>> 45 MOUNTAIN MTOUTLAW.COM

North Bridger Bison owners Matt and Sarah Skoglund pose with their children, Otto and Greta. North Bridger Bison is a bison ranch located in Wilsall, Montana. PHOTO BY CHRIS DOUGLAS

Matt, a former lawyer from Chicago, first got attached to the idea of ranching bison while focusing on Yellowstone’s bison as an employee for the Natural Resources Defense Council.

Matt, a former lawyer from Chicago, first got attached to the idea of ranching bison while focusing on Yellowstone’s bison as an employee for the Natural Resources Defense Council.

46 MOUNTAIN MTOUTLAW.COM

PHOTO BY MICHAEL RUEBUSCH

ing most of his days seated behind a desk, while Sarah worked as an interior designer. They left Chicago the month after they were married, seeking adventure, a connection to place and a community that aligned with those values. They found it in Bozeman. Matt spent a decade working in environmental policy for the Natural Resources Defense Council, while Sarah worked at the Cancer Support Center and earned a graduate degree in social work. They started a family and rooted themselves in the Gallatin County community.

"Having lived here for a long time, and through my environmental conservation work with NRDC and my outdoor adventures, I fell madly in love with this region, the landscape and the people," Matt said. "I had this entrepreneurial itch; I wanted a change and a challenge, and I knew very clearly that I wanted it to be deeply rooted in the greater Bozeman community."

At some point, Matt began daydreaming about starting a bison ranch. He had been focused on Yellowstone bison policy at NRDC but wanted to do something more tangible and food-based on the land. He then read "Buffalo for the Broken Heart," by Dan O'Brien in the fall of 2017, a story about bison ranching and pioneering the modernday method of field harvesting, and it's then that Matt got serious. After reading O'Brien's book, he attended a multi-day holistic management workshop. When he returned home, he started looking for land to purchase within a 50-mile radius of Bozeman with no luck. At the same time, he went into what he calls "sponge mode," researching and learning everything he could about what he started calling his bison ranch pipe dream, a destiny he feared was better fated for someone with a ranching background.

In late winter of 2018, he fell upon a few parcels of land off Montana Highway 86 while deep down a Google-search rabbit hole of properties for sale. It was the first and only piece of land the Skoglunds looked at in person; it was perfect for what they wanted to do. "Until then, the bison ranch had felt about as possible as flying a plane to Pluto," Matt said. The property brought his dream into focus.

"When we first came out to this piece of land, I just felt like we belonged here," Sarah said. "The land became my anchor point—it just felt like everything started aligning. We both are very conscious that life is short and that perspective has been a major North Star in this process. Matt had been

talking endlessly about his passion for tangible land conservation, of doing something good for the planet. Eventually, the risk of not doing this became greater than the risk of trying and failing."

The bison arrived by truck from Choteau, Montana, in late January 2019. So much had gone into preparing for that day: research, meetings, mentoring, ranch tours, loan approvals, not to mention a great deal of financial and emotional risk for the Skoglund family.

"That was a surreal day," Sarah said. "It was breathtaking to see the animals come off the truck, run onto this land that was finally ours and settle immediately—as though they belonged here. I distinctly remember thinking at that moment that everything would change—that we were doing something so wild and important and that it was all finally happening."

That night, Matt, a self-proclaimed romantic, slept huddled in a sleeping bag on the ground on the other side of the fence from the herd. "I woke up that morning, made coffee on a camping stove, and stood watching the bison in the pasture," he said. "There was an overwhelming feeling of calm and contentment. I thought, 'they're here, and this is real.'"

Matt runs the ranch using regenerative agriculture principles. The philosophy behind this type of management is that the animals are part of a more extensive system that benefits the land and leaves it healthier than before. The bison are raised in sync with nature, with a focus on soil health, land health and increased biodiversity. The Skoglunds also manage their bison with as little human intervention and stressors as possible.

"There is certainly a lot of green-washing and misleading messaging around the term regenerative these days," Matt said. "There are also plenty of people, like our neighbors, who

>> 47 MOUNTAIN MTOUTLAW.COM

have been ranching for a long time and doing it regeneratively, but they never put a word to it. And—I'm not the right person to speak on it—but the idea that regenerative agriculture is new is untrue—indigenous cultures have been producing food and doing it regeneratively for millennia."

He says that while the conversation around food, carbon and climate is incredibly important, there's not enough focus on biodiversity. He believes the science is clear that raising animals can be the most effective way to grow food in balance with nature. He also thinks cattle have been unfairly vilified and that pushing plant-based eating as the healthy choice for both people and the planet is misguided. Matt likes to quote a well-used term in regenerative ranching: "It's not the cow; it's the how."

"Many of these plant-based foods are highly processed and come from ecologically destructive, industrial, monoculture crop farms," he said. "That land is losing topsoil every year, using all sorts of pesticides and other chemicals, poisoning rivers and destroying wildlife habitat. Contrast that with a regenerative approach to ranching that builds topsoil, sucks carbon out of the atmosphere and provides amazing wildlife habitat and healthy meat. It all comes back to management practices. You tell me which system you think is better for your body and for the planet."

This philosophy is why the mission behind North Bridger Bison continues to be simple:

to raise bison as well and as in sync with nature as possible and to provide customers with amazing meat.

Matt puts a lot of thought into each order that he fills, including a tasteful before and after photograph of the herd and the harvested bison to help make the process of field-to-food more transparent. Customers choose between purchasing a whole bison, half or quarter, and between a few different cut options.

Matt field harvests each bison himself. That means driving out into the herd, shooting a perfect headshot from 15-20 yards, and loading the animal onto his truck. He then either field dresses the bison himself and takes it to Amsterdam Meat Shop in Manhattan, or he works with two of their team members on the ranch using his mobile processing truck. The job is challenging, labor-intensive and filled with emotion and a deep sense of responsibility.

His first field harvest was in the spring of 2019. It was one of those days when it's sunny and then rainy, snowy and windy—a classic Montana day. "I remember being really nervous because I so desperately wanted, and needed, everything to go well," Matt said.

Leading up to the task, he wondered if there would be any symbolic action connecting him with the harvest. He later realized that the ritual he sought was ultimately the intense focus he brings to each field harvest.

"I take it very seriously, becoming hyperfocused through the adrenaline and nerves;

>> 48 MOUNTAIN MTOUTLAW.COM

The Skoglund’s herd consists of approximately 150 head of bison.

The Skoglund’s herd consists of approximately 150 head of bison.

49

PHOTO BY MICHAEL RUEBUSCH

MOUNTAIN MTOUTLAW.COM

I lose myself in the process of preparing, driving into the pasture, and executing the perfect shot," he said. Because of this, Matt was very protective of his field harvest days for a long time. He still prefers to field harvest alone but on occasion brings others out with him. "I'm passionate about what we do, and I love showing people the whole process—but I still prefer it when I'm by myself. It's never lost on me that I'm going to kill a bison. If I'm ever driving out to shoot a bison and I feel nothing, there's a problem."

Matt makes a point of clarifying that field harvesting is not hunting. "I love to hunt, and if I'm going elk hunting, I very rarely get one. More often than not, I'm just going out and having a great day in the mountains," he said. "Field harvesting is completely different. When you open that gate, you know you're going to kill something, and there's a gravity to that."

As an avid user and supporter of public land, Matt now better understands the role private land can play in conserving the wild places he loves. "There's such a strong push for protecting public lands, and rightfully so," he said. "Since starting the ranch and becoming a rancher, I've also begun to appreciate now more than ever the conservation benefits and responsibility that come with ranching and private land ownership more than I ever had. I look at our ranch and neighbors' ranches and see this open space,

amazing biodiversity, incredible wildlife habitat, and pollinators everywhere. And, the cherry on top is that it also provides delicious, healthy food."

This past April, they finalized something they'd been dreaming about since starting North Bridger Bison when they signed a conservation easement with the Gallatin Valley Land Trust. The easement will forever keep their 791 acres from being subdivided or developed.

Matt wrote his “note," similar to a thesis, on conservation easements during law school and fell in love with their conservation benefits. Still, the process for enrolling property in an easement and working out the details is a long one. The North Bridger Bison easement, in particular, took about three and a half years, so when Matt and Sarah finally closed on the easement they were thrilled. "When I returned to the ranch later that day, it just felt different looking out onto the land and knowing that it will be protected forever; it just felt different," Matt said.

That night they sat down at the dinner table with their two children, Otto (9) and Greta (5), and shared the news. "I got emotional explaining to them what we had done that day," Matt said. "It was a really special and powerful moment for our family."

Brendan Weiner, conservation director at GVLT, sees endless benefits to putting a property like the Skoglunds'

Top Right: Matt explains the layout of the 791 acres of land he owns, which are scenically sandwiched between the Crazy Mountains and the Bridger Range. PHOTO BY MICHAEL RUEBUSCH

50 MOUNTAIN MTOUTLAW.COM

Bottom Right: The Crazy Mountains backdrop Matt on his Wilsall ranch. PHOTO BY MICHAEL RUEBUSCH

into an easement. "Matt and Sarah are young and new to ranching, but they're capable and interested in continuing this generation of young ranchers," Weiner said. "They bring new energy and new ideas to our local agricultural economy and our culture—their success is important to this community on many levels."

The easement is a clear message that the Skoglunds are serious about North Bridger Bison, conservation ranching and

their growing community.

The Skoglunds moved out to the small ranch house on the property in June 2021 and started work on an addition, consciously designed to blend into the landscape they love so deeply as much as possible. The foundation and heart of the addition is a giant mudroom to accommodate the perma-mud from four-plus pairs of boots and the four paws of their 8-month-old german shepherd, Sally—a constant reminder of how the land permeates every aspect of their lives.

"We're new at this," Matt said. "We're different, and we know we're different. We're not pretending to be something we're not. We're first-generation, raise bison, and weren't born and raised in Montana. But we have a fierce love for this place, and ranching is not a game or a hobby to us—we are here, passionate about ranching and what we do, and committed to regenerative agriculture and taking care of this land."

Sophie Brett Tsairis is a Bozeman-based freelance writer with a master’s in Environmental Science Journalism. Storytelling is her way of sharing the human experience and keeping curiosity alive.

51 MOUNTAIN MTOUTLAW.COM

Montana | Colorado | Utah | CENTRESKY.COM | 406.995.7572 Montana | Colorado | Utah | CENTRESKY.COM | 406.995.7572

Chasing billfish in Costa Rica or Cabo or relaxing along the Emerald Coast of Florida, Jimmy Azzolini, Big Sky resident, is your authority on yacht ownership. Jimmy has been with Galati Yacht Sales, the largest family-owned yacht brokerage firm worldwide, since 2000. During this time, Jimmy has helped countless families match the right yacht to their lifestyles. Find out more about yacht ownership and how Jimmy and Galati Yacht Sales can help you create new memories.

FIND

JIMMY AZZOLINI LICENSED + BONDED YACHT BROKER 850.259.3246 SCAN HERE TO LEARN MORE FL | AL | TX | CA | WA | MX | CR WWW.GALATI YACHTS .COM

Bozeman’s White Bears

BY MIRA BRODY PHOTOS BY DANIEL J. COX

Polar Bears are one species who’s habitat is greatly impacted by a changing climate.

BY MIRA BRODY PHOTOS BY DANIEL J. COX

Polar Bears are one species who’s habitat is greatly impacted by a changing climate.

A photographer and an academic team up to extend Bozeman’s conservation community to the Arctic 54 MOUNTAIN MTOUTLAW.COM

J. Cox has traveled to Churchill, Manitoba,

1989

in Canada’s Hudson Bay—

International, located 2,000 miles from Manitoba in Bozeman, Montana.

Originally a modest, volunteer-driven organization called Polar Bears Alive founded in 1994, PBI graduated into what is now the largest climate change resource and polar bear advocacy group in the world. Cox became involved when he met founder Dan Guravich and convinced the group to settle in the quiet southwest Montana ski town where it could draw on the talents of professionals committed to wildlife conservation while coordinating field projects around the world. Today, the photographer and conservation group share an office on the town’s northeast side.

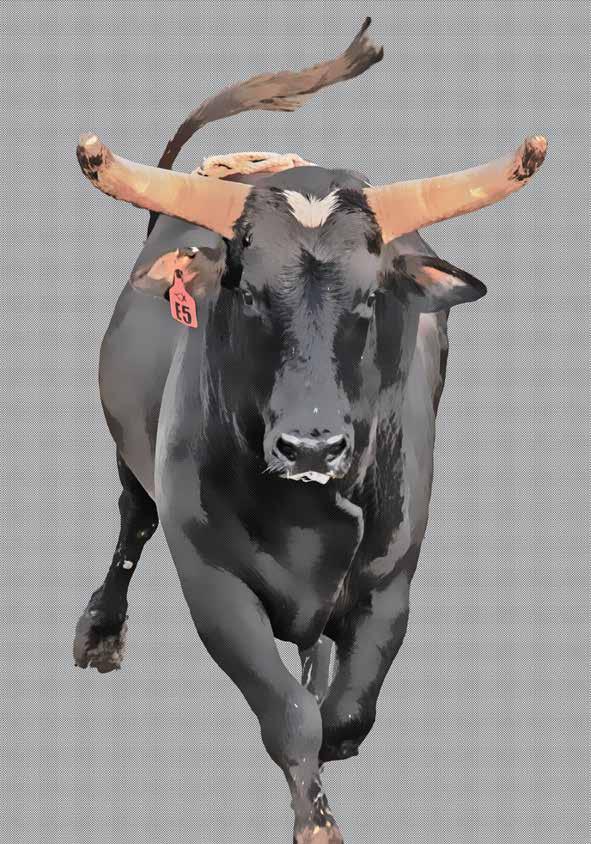

“Polar bears are incredible creatures,” said Steven Amstrup, PBI’s chief scientist and one of the world’s top polar bear experts. “And now they have taken on so much more importance because they are the symbol of the dangers of the constantly warming climate. We have this incredible, charismatic species that I think everyone has an appreciation for that is also sending us a really important message.”

And what’s that message? We all share a single planet that is changing dramatically. And while many of us live far from polar bears and will likely never see one, what we do dramatically influences their habitat.

Amstrup is an adjunct professor at the University of Wyoming in Laramie and currently resides in Kettle Falls, Washington. He says his love for bears began when he was 5 years old, a passion that evolved into his studies and later, his profession. His University of Idaho master’s thesis focused on black bears. Shortly after, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service asked him to lead polar bear research in the Alaskan Beaufort Sea

>> 55 MOUNTAIN MTOUTLAW.COM

Daniel

each year since

to document polar bears

one of the lowest latitudinal locations on Earth they can be seen in their natural habitat. For the past 30-plus years, the natural history and wildlife photojournalist has been providing these images to the nonprofit Polar Bears

for the Polar Bear Research Project from 1980 until 2010. He began volunteering with PBI in 2001 and his storied relationship with these Arctic bears has spanned decades, continents and groundbreaking research, including a study published in the peer-reviewed journal Nature Climate Change on projected ice loss and polar bear population decline.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Polar Bear Specialist Group lists the polar bear as a “vulnerable” species, meaning they are threatened by extinction unless circumstances drastically change. The union estimates that about 26,000 of these ivory bruins exist worldwide. Sea ice loss coupled with increased commercial activities, conflicts with people, pollution and disease are greatly threatening the bears and their habitat. In the time since Amstrup and Cox have studied these creatures, their population in Canada’s Northern Hudson Bay alone has dropped by 30 percent.

Both men have observed these habitat changes firsthand.

On Cox’s first trip to Churchill in November of 1989, he watched bears gather on an ice shelf in Hudson Bay to hunt seals. Today, the ice shelf isn’t large enough for bears to hunt until early December, depriving the bears of precious weeks. Part of Cox’s work with PBI includes a partnership called the Arctic Documentary Project, which he launched in 2005 to channel what he calls his important work: photographs that fuel a movement.

Steven Amstrup captures a Polar Bear.

A ship takes a trip through scattered ice in the Arctic.

Steven Amstrup captures a Polar Bear.

A ship takes a trip through scattered ice in the Arctic.

“Conservation is not just about game wardens and [U.S.] Fish and Wildlife employees … It’s really about how the rest of us live and recognizing our responsibility for caring for all life on Earth.”

56 MOUNTAIN MTOUTLAW.COM

- Steven Armstrup

“When I first started in this business in 1981—and before that as just a kid who liked to take pictures—I had this hope that these pictures would show people that we need to be considerate of these animals and that we need to protect them,” Cox said.

Amstrup recalls standing on the north coast of Alaska in 1981, staring at the Arctic Ocean and seeing sea ice even in the summer months. Today, that ice is out of sight, beyond the curvature of the Earth.

“Every species has a need for various ecosystem services: the ability to catch food, get water and a habitat that is undisturbed,” Amstrup said. “If you think about the habitat that polar bears live in, it’s a very different one than any other place that animals live … but their habitat is critical to their existence.”

Amstrup explained that while the impacts on polar bears may be more obvious because their habitat visibly melts, every species–including those we love here in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, are feeling the same peril. We all live in one shared atmosphere.

There’s something about polar bears that draws people’s attention. Despite their apex stature, they appear fuzzy and cuddly, pure and white, and thrive in a cold, harsh landscape unreachable to most of humanity. It’s this collective love for these bears and for conservation work, Cox and Amstrup agree, that carries hope for PBI’s efforts playing out thousands of miles south of where the bears live.

“The important thing is that saving polar bears is about teamwork,” Amstrup said. “I think that PBI has been really good at getting the word out that this is what we need to do. Conservation is not just about game wardens and [U.S.] Fish and Wildlife employees … It’s really about how the rest of us live and recognizing our responsibility for caring for all life on Earth.”

Mira Brody is content marketing strategist at Outlaw Partners and producer of Mountain Outlaw magazine.

57 MOUNTAIN MTOUTLAW.COM

Amstrup is the top Polar Bear scientist in the world and has observed the species for most of his life.

of Clothing at voormi.com EXPERIENCE THE DIFFERENCE BOZEMAN, MT | PAGOSA SPRINGS, CO

The Future

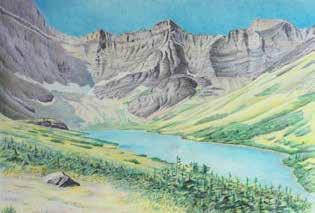

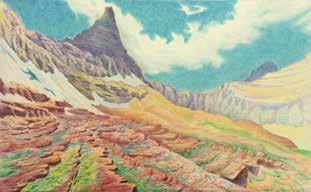

Jonathan Marquis draws Vulture Glacier in Glacier National Park. "Every time I put a pencil to paper, it's always a discovery. That's my style. I don't know what I'm doing, let me try," said Marquis.

Jonathan Marquis draws Vulture Glacier in Glacier National Park. "Every time I put a pencil to paper, it's always a discovery. That's my style. I don't know what I'm doing, let me try," said Marquis.

60 MOUNTAIN MTOUTLAW.COM

PHOTO BY RICHARD FORBES

Jonathan Marquis draws connection between Montana’s glacial and human communities

BY RICHARD FORBES

BY RICHARD FORBES

Jonathan Marquis puts pencil to paper, shaping the glacier as it claws the mountain before us. Lost in quiet exchange, he doesn’t seem to notice the bellowing grizzlies 1,000 feet away, their roars reverberating throughout the basin. The Vulture Glacier, wrinkled with melt lines and patterned blue ice, is perched opposite him above the lake-lined valley it carved long ago. Marquis sits cross-legged on the rocks, his body hunched, embedding himself in the landscape. The glacier is a lifeworld and Marquis is bearing witness.

Over the last nine years, as part of a lifelong journey to see and share how climate change is affecting his chosen community, Marquis has visited and drawn nearly 50 of Montana’s glaciers. By the end of summer 2022, the artist only had seven left to visit.

When Marquis talks about his drawing project, people always tell him he better hurry up, because he doesn't have long. Indeed, temperatures in Montana and the Intermountain West are rising faster than the global average. These rising temperatures, coupled with decreasing snowfall, are melting

glaciers ever more quickly. For years now, glaciologists, climate activists and journalists have tied glaciers to the climate movement, using stories of the glaciers’ degradation as an emotional catalyst to spur people into action. But that's only a small part of the story of glaciers. Marquis believes a singular narrative centered on loss does glaciers and the animal, plant and human communities that surround them an immense disservice, and may imply that there’s almost no hope left.

Here's Marquis’ take: What if, instead of scaring people into addressing our fraught relationship with the planet, he used his art to show what the glaciers look like, right now? What if his drawings could show that glaciers aren't chunks of ice, they're beings, and therefore members of our global community of humans, plants, animals and elements, each worthy of life? By offering a different way to imagine glaciers—as their own rich lifeworlds in need of caretaking— Marquis believes he can be part of a broad network of people inspiring a healthier relationship with our world.

Marquis never meant to become a landscape artist. Study-

>> 61 MOUNTAIN MTOUTLAW.COM

ing at Ball State, and later at the University of Montana, he became a process artist, subscribing to an artistic movement in which the process of making art is as important as the final product. At that time, he was exploring pop art, abstract expressionism and collage. He was also pursuing his own mindfulness practice, spending days wandering around the mountains near Missoula, slowing down and drawing whatever he saw. Marquis sought a long-term project in which to lose himself.

In 2013, Marquis attended a presentation by Doug Peacock, a writer and conservationist whom he’d long admired. During the Q&A, Marquis asked Peacock what a young artist could do to continue the conservationist’s work. "Bear witness to your own backyard," Peacock said.

At first, Marquis wasn't sure what exactly he should bear witness to, but at the time, glacial melt in Glacier National Park was all over the news. With some research, he learned there were at least as many glaciers in Montana outside the national park as inside, some only 30 miles from home. He remembers thinking, "Holy shit, there's a fuck-

ton of wilderness glaciers in Montana, and no one's talking about those. What's going on in there?" Marquis and his friends had spent more than a decade mountaineering throughout the state and he knew he had the skills to at least get started. He figured the project would take him six or seven years at most.

Nine years later in early June of

from Tucson, where he lives most of the year teaching art at the University of Arizona and a local community college. When the spring semester ends, he drives to Montana for the summer. I’d learned about his project a few months earlier, and after an hour talking mountains, I mustered up the courage to ask if I could visit glaciers with him.

He leaned forward, his eyes narrowing. "What story are you trying to tell about glaciers?"

I wasn’t sure how to answer, so I said what I knew: I wanted to tell stories about the relationship between people and glaciers and see what I found. That was good enough for him.

It is extremely difficult to reach most glaciers in Montana. Few have trails and most are deep in the backcountry, plastered to protective cliffs and guarded by miles of dense vegetation and scree. While the West is full of peakbaggers chasing summits, few other than scientists set their sights on glaciers, and even they rarely have the funding, time or skillset to visit the most remote glaciers.

Visiting all the glaciers in Montana is a bold goal, one I can find no record of anyone achieving. To pull it off, you need to be a few things: absurdly stubborn; comfortable enough in the backcountry to know you can handle whatever you find; and willing to go in blind, as Montana is famous for its tightlipped outdoors community. In

I once asked Marquis to describe a glacier for someone who'd never seen one. He said watching a glacier as it tears the land is raw, everything around it upturned and fresh. Glaciers are so present, he said. It’s impossible to look away. They are sublime, wondrous, frightening, rugged, exhilarating.

2022, I met Marquis for a beer in Missoula. He’s thin and angular with a cockeyed smile. His eyes are expressive, and when he’s thinking hard—which is often—he squints. Even then his eyes are always twinkling with a joke, making him seem younger than his 41 years.

Marquis had just arrived in Missoula

California and Colorado, there are endless forums devoted to unraveling the mountains. In Montana, as soon as you leave the beaten path, you’re on your own. Big adventures require hours poring over maps and building trust with the small communities who know how the landscape fits together. Even when

After sneaking past a pair of grizzlies in Glacier National Park, Marquis leaps over a gap on the way back to camp. PHOTO BY RICHARD FORBES

62 MOUNTAIN MTOUTLAW.COM

you think you understand the terrain, you’ll never know what conditions you’ll find. Each trip is founded in faith, tenuous tips and the unknown.

In early August, we got a chance at our first glacier together. Forty miles and three days into the trailless depths of Glacier National Park, we found ourselves at Vulture Glacier. Vulture was the third of five glaciers we’d hoped to visit this trip, but the terrain was rougher than we’d expected and we realized we might only have a chance at one more. Marquis started a few drawings and packed them up to finish later in the studio.

I lagged as we pressed toward the next glacier, careful not to disturb a grizzly sow and her cub foraging for larvae, wrestling and bellowing at one another. Only a few years earlier, one of Marquis' friends had been attacked by a grizzly a few miles away. To give them

space, we found a new route creeping across a steep snowfield and slogging our way up fields of loose scree. At every step, the park’s infamous rotten rock crumbled underfoot and sloughed down the mountain.

From the summit, we could see at least seven glaciers, one of which Marquis hadn't yet visited. The day was beginning to fade, so Marquis took photos to draw from later. We skidded headlong down the loose rock back to the basin and the squabbling grizzlies. We tiptoed past them, shielded by a rock rib, holding our breath, before safely emerging into a different valley. As the sun set, we walked by glaciallycarved slabs and fields of wildflowers to camp. The next day we arrived back at the car with four glaciers, 60 miles and 20,000 feet of elevation gain behind us. Glaciers are defined as masses of ice flowing downhill under their own