FOR VCE

Source 1 The Victorian criminal justice system is made up of processes and institutions that investigate and determine the outcomes of criminal cases. The criminal justice system also includes the police, who have an important role in promoting a safe, secure and orderly society. In this chapter you will consider key principles in the Victorian criminal justice system, and the rights of an accused and of victims in a criminal case.

By the end of Unit 3 – Area of Study 1 (i.e. Chapters 3, 4 and 5), you should be able to explain the key principles of the criminal justice system, discuss the ability of sanctions to achieve their purposes and evaluate the ability of the criminal justice system to achieve the principles of justice during a criminal case.

In the chapter, you will learn about:

• the distinction between summary offences and indictable offences

• key principles of the criminal justice system, including the burden of proof, the standard of proof, and the presumption of innocence

• the rights of an accused, including the right to be tried without unreasonable delay, the right to silence, and the right to trial by jury

• the rights of victims, including the right to give evidence using alternative arrangements, the right to be informed about the proceedings, and the right to be informed of the likely release date of the offender.

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

• define and use legal terminology

• discuss, interpret and analyse legal principles and information

• explain the rights of an accused and of victims in the criminal justice system

• synthesise and apply legal principles and information to actual and/or hypothetical scenarios.

accused a person charged with a criminal offence alternative arrangements processes put in place by a court to protect vulnerable witnesses when they are giving evidence in cases of sexual offences or family violence

balance of probabilities the standard of proof in civil disputes. This requires the plaintiff to establish that it is more probable (i.e. likely) than not that their version of the facts is correct beyond reasonable doubt the standard of proof in criminal cases. This requires the prosecution to prove there is no reasonable doubt that the accused committed the offence

burden of proof the obligation (i.e. responsibility) of a party to prove a case. The burden of proof usually rests with the party who initiates the action (i.e. the plaintiff in a civil dispute and the prosecution in a criminal case)

Human Rights Charter the Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act 2006 (Vic). Its main purpose is to protect and promote human rights

imprisonment involuntary detention ordered by a court as punishment after an offender has been convicted of an offence indictable offence a serious offence generally heard before a judge and a jury in the County Court or Supreme Court of Victoria jury a panel of people (generally 12) assembled to hear the case against an accused and decide whether they are guilty offender a person who has been found guilty of a criminal offence by a court presumption of innocence the right of a person accused of a crime to be presumed not guilty unless proven otherwise prosecution the party prosecuting the case against an accused sanction a penalty (e.g. a fine or prison sentence) imposed by a court on a person guilty of a criminal offence standard of proof the degree or extent to which a case must be proved in court summary offence a minor offence generally heard in the Magistrates’ Court victim a person who has suffered directly or indirectly as a result of a crime

Victims’ Charter the Victims’ Charter Act 2006 (Vic), which recognises the impact of crime on victims and provides guidelines for the provision of information to victims

A list of key legal cases covered in this chapter is provided on page XX.

Extracts from the VCE Legal Studies Study Design (2024–2028) reproduced by permission, © VCAA.

Check your Student obook pro for these digital resources and more:

Warm up!

Check what you know about the Victorian criminal justice system before you start.

Test your knowledge of the key legal terms in this chapter by working individually or in teams.

criminal justice system a set of processes and institutions used to investigate and determine criminal cases accused a person charged with a criminal offence

sanction a penalty (e.g. a fine or prison sentence) imposed by a court on a person guilty of a criminal offence

imprisonment involuntary detention ordered by a court as punishment after an offender has been convicted of an offence

The criminal justice system is a set of processes and institutions used to enforce criminal laws and determine criminal cases. It involves the police, courts and prisons. Two of the key purposes of the criminal justice system are to:

• decide whether an accused is guilty of an offence

• impose a sanction in cases where an accused has been found or pleaded guilty to committing a n offence.

Source 1 shows the three main stages of a criminal case. Each stage involves multiple processes and bodies:

• the investigation stage includes the investigation of an offence and the charging of an accused

• the determination stage involves the courts deciding whether the accused is guilty and what sanction will be imposed

• the corrections stage involves overseeing any sanction imposed, such as imprisonment (the offender spending time in jail) as well as any post-sentencing procedures such as being monitored.

Australian Constitution a set of rules and principles that guide the way Australia is governed. Its formal title is Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act 1900 (UK) Commonwealth offences crimes that break a law passed by the Commonwealth Parliament statute a law made by parliament; a bill that has passed through parliament and has received royal assent (also known as legislation or an Act of Parliament)

There is no single, unified criminal justice system in Australia. This is because under the Australian Constitution, the Commonwealth Parliament does not have power to make laws about crime in general. This is left to the states, which have the power to legislate for the peace, order and good government of their own states, and the general power to maintain public order and protect individuals who reside within their state. Therefore, each state and territory has its own criminal justice system, as well as laws that establish:

• what is considered a crime

• the processes used to decide if someone is guilty

• the maximum penalty that can be imposed for each specific crime. Each state and territory also has its own police force, courts and prison system, although they are similar. Although the administration of criminal justice is a power held by the state, the Commonwealth Parliament has the power to make criminal laws if it relates to its own law-making powers in some way (such as avoiding customs duties, because customs is a Commonwealth power). These are known as Commonwealth offences. Commonwealth offences have expanded over time and there is now a great deal of overlap between Commonwealth and state crimes. Some crimes, such as some drug offences, could be either a state offence or a Commonwealth offence.

Many of the Commonwealth offences are set out in the Commonwealth Criminal Code, which is contained in a statute passed by the Commonwealth Parliament. The Code includes offences such as:

• engaging in a terrorist act

• people smuggling (where people help others to enter Australia illegally)

• espionage crimes (such as communicating information about national security to a foreign country).

In Victoria the main courts that hear and determine criminal cases are:

• the Magistrates’ Court

• the County Court

• the Supreme Court.

Victoria also has specialist courts, including a Children’s Court. This court hears criminal cases where a child (between the ages of 10 and 17 at the time of the offence) has been accused of committing a crime – except for certain serious crimes such as murder and arson causing death, which will be heard in the higher courts (i.e. the County Court or the Supreme Court).

A criminal case involves two parties:

• the prosecution (the party prosecuting the case against an accused, and generally representing the community)

• the accused (the person or organisation alleged to have committed a crime). The victim is not a party to a criminal case and does not bring the court action.

The term ‘prosecution’ is generally used to describe the party that presents the evidence in court on behalf of the state (or Commonwealth) against a person accused of committing the crime. The ‘prosecution’ includes the prosecutor, who occupies a special position in the prosecution as they have special duties and obligations. These are explored further in Chapter 4.

In Victoria the Office of Public Prosecutions (OPP) works with the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) and Crown Prosecutors to prosecute serious crime on behalf of the Crown in the County Court and the Supreme Court of Victoria. In less serious cases, Victoria Police officers will usually prosecute crimes in the Magistrates’ Court. Other organisations such as local councils, VicRoads and WorkSafe Victoria also have power to prosecute less serious offences.

As you have learnt, the person charged with a crime is known as the accused. There can be multiple accused persons in a criminal case, depending on the crime alleged to have been committed. Companies can also be charged with offences such as taxation fraud, offences relating to workplace health and safety, wage theft laws (see Chapter 2) and environmental offences.

At this stage, you only need to understand that each state has law-making powers in relation to criminal law, and therefore each state has its own criminal justice system. You will learn more about lawmaking powers in Unit 4 – Area of Study 1. It is a good idea to come back and review this chapter when you start Unit 4.

prosecution the party prosecuting the case against an accused

prosecutor the Crown in its role of bringing a criminal case to court (also called ‘the prosecution’)

Office of Public Prosecutions (OPP) the Victorian public prosecutions office that prepares and conducts criminal proceedings on behalf of the Director of Public Prosecutions

Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) the independent officer responsible for commencing, preparing and conducting prosecutions of indictable offences on behalf of the Crown

jury a panel of people (generally 12) who hear the case against an accused and decide whether they are guilty

Actual scenario

In the scenario below, the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions (CDPP) charged two people in relation to importing into Australia a commercial quantity of ephedrine, an ingredient used to manufacture the drug known as ‘ice’.

Section 307.11(1) of the Commonwealth Criminal Code makes it an offence for a person to import or export certain ‘precursors’ (chemicals that can be used to manufacture drugs) of a ‘commercial quantity’. The maximum penalty is 25 years in prison or 5000 penalty units, or both. One of these precursors is ephedrine. Ephedrine can be used to manufacture the drug methamphetamine (‘ice’), a dangerous drug that has had devastating effects on people’s health and lives, sometimes resulting in death.

In this case, two men were charged with importing more than 1000 kg of ephedrine, well above the commercial quantity of 1.2 kg. One of the men was alleged to have overseen the importation of the substance, and the other was alleged to be in charge of the finances and handling its sale in Australia. After a trial that ran for 17 days, the jury returned a verdict of guilty against each accused. They were both sentenced to more than 17 years in prison for their role in the crime. In sentencing the two men, the judge said the crime was in the worst category of its type, particularly given the size of the importation, the potential profits involved, and the roles played by the offenders. In his comments, the judge congratulated the police involved in the investigation, noting that the community had been saved from the ‘ravages’ of large volumes of the drug being distributed around the country.

CDPP v Chan & Chen [2022] VCC 1463

1 Define the term ‘criminal justice system’.

2 Is there one single unified criminal justice system in Australia? Explain

3 Distinguish between police prosecutors and the OPP.

Examine and apply

4 Construct a visual diagram that shows the three stages of a criminal case. Include as many bodies, people or processes as possible involved at each stage. You may need to conduct some further research.

5 Read the scenario ‘Two men jailed for importing a banned substance’.

a Identify the parties in the case.

b Describe the nature of the offence.

c Explain why a jury was required in this trial.

d Explain why this was a Commonwealth offence.

6 Visit the Australasian Legal Information Institute (AustLII) website (see weblink on your obook pro). Find the page with this year’s County Court judgments.

a Find a recent criminal judgment in which a sentence was handed down.

b Provide a summary of the parties to the case, the charges alleged against the accused, whether there was a jury trial, and the sentence.

c Write some questions for a classmate to answer based on your summary of the judgment.

Weblink Australasian legal Information InstituteIn this topic, you will learn about:

• key principles of the criminal justice system, including the burden of proof, the standard of proof and the presumption of innocence.

In this topic you will learn about three key principles of the Victorian criminal justice system:

• the burden of proof

• the standard of proof

• the presumption of innocence.

burden of proof

the obligation (i.e. responsibility) of a party to prove a case. The burden of proof usually rests with the party who initiates the action (i.e. the plaintiff in a civil dispute and the prosecution in a criminal case)

The burden of proof refers to which party has the responsibility to prove the facts of the case. The burden of proof lies with the person or party who is bringing the case. In a criminal case, this is the prosecution (i.e. the prosecution must prove that the accused is guilty).

One of the justifications for this is that if the prosecution is accusing a person of having committed a crime, then the responsibility should be on the prosecution to establish the facts.

In a few cases the burden of proof can be reversed – for example, if the accused is pleading a defence such as self-defence.

Section 5 of the Drugs, Poisons and Controlled Substances Act 1981 (Vic) is another example. It states that a person is presumed to possess a substance if:

• the substance is on their property (owned, rented, used or occupied), and

• the person cannot satisfy the court to the contrary. In this case the onus (responsibility) will be on the accused to prove the drug was not in their possession.

standard of proof

the degree or extent to which a case must be proved in court

beyond reasonable doubt

the standard of proof in criminal cases. This requires the prosecution to prove there is no reasonable doubt that the accused committed the offence

The standard of proof refers to the level of certainty or strength of evidence required to prove the case. In a criminal case, the prosecution must prove the case beyond reasonable doubt. Proving someone guilty beyond reasonable doubt does not mean that no doubt at all exists as to the accused’s guilt. It only means that no reasonable doubt is possible from the evidence presented. The judge or members of the jury may still be able to think of fanciful, imaginary or unreasonable doubts (i.e. doubts that are not realistic or based on the evidence), but these do not count. To prove guilt in a criminal case, what matters is that no other logical or reasonable conclusion can be reached (based on the facts) except that the accused is guilty.

In a criminal case involving indictable offences, the case is heard in the County or Supreme Court and a jury will be given instructions that it must be satisfied of guilt beyond reasonable doubt (Chapter 4 has more information about juries).

balance of probabilities the standard of proof in civil disputes. This requires the plaintiff to establish that it is more probable (i.e. likely) than not that their version of the facts is correct presumption of innocence the right of a person accused of a crime to be presumed not guilty unless proven otherwise common law law made by judges through decisions made in cases. Also known as case law or judge-made law (as opposed to statute law)

In a criminal case involving summary offences, the case is heard in the Magistrates’ Court and a magistrate (not a jury) will decide on guilt. If the burden of proof is on the accused (for example, the accused is relying on a certain defence), then the standard of proof is on the balance of probabilities

The presumption of innocence is one of the most important principles of our criminal justice system and of the rule of law. It means that if person is accused of committing a crime, they are considered innocent until proven otherwise. That is why a person is called an ‘accused’ before they are proven guilty.

The presumption of innocence is an old common law right. It is now also guaranteed by the Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act 2006 (Vic). This is a Victorian statute that protects certain human rights. You will learn more about this statute in the next topic.

One of the critical ways in which the presumption of innocence is upheld is by imposing a high standard on the prosecution to prove its case (that is, beyond reasonable doubt), and by imposing the burden of proof on the prosecution. That is, the prosecution must prove that the accused is guilty. Accused persons do not have to prove they are innocent.

The principle of the presumption of innocence is often discussed, including in relation to ‘innocence projects’ that have been established around the world to investigate claims of wrongful convictions.

Innocence projects seek to free innocent people who have been convicted for a crime that they did not commit. The projects are usually independent and not-for-profit, and they are often staffed or assisted by university professors and university students, such as students studying law.

For example, the University of Baltimore’s Innocence Project Clinic seeks to help clients who profess their innocence. One of its directors is Professor Erica j. Suter. l aw s tudents at the university work to free wrongly convicted prisoners,

including taking up cases where new Dn A te sting is available to help prove innocence.

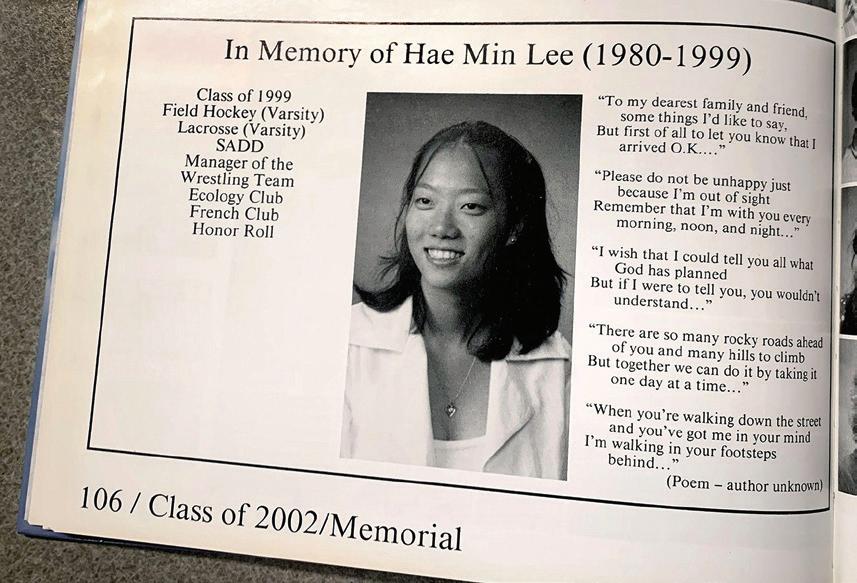

One of the more high-profile cases taken on by Professor Suter (and others) was in relation to Adnan Syed. Adnan Syed was sentenced to life in prison for the 1999 murder of his former high school girlfriend, hae Min lee he was found guilty by a jury in 2000 and sentenced to life in prison. he maintained his innocence. Adnan Syed’s case received worldwide interest after a podcast, ‘Serial’, was released about the case. The episodes were downloaded more than 68 million times. In October 2022, after Adnan had spent 23 years in prison, prosecutors dropped all charges against him and he was released from prison. his Dn A excluded him, as it did not match the Dn A recovered from the crime scene.

Questions remain about who killed hae Min lee her relatives have made emotional pleas, saying this has been a ‘never-ending nightmare’ for their family.

Closer to home, the Bridge of hope Innocence Initiative in Melbourne is a joint venture between rMIT University and The Bridge of hope Foundation. It investigates claims of wrongful conviction. l aw students can complete an internship at the Initiative as part of their studies.

A number of features of the criminal justice system uphold the presumption of innocence. For example:

• an accused has the right to silence, which means they do not need to answer any questions, and do not need to give evidence in court. A person’s silence is not to be taken as a sign of guilt. You will learn more about this right in the next topic

• police must reasonably believe a person has committed a crime before they can arrest that person

• for indictable offences, the prosecution must prove there is enough evidence to support a conviction before they can take a case to trial

• generally, a person’s prior convictions cannot be revealed until sentencing (after they have been found guilty)

• an offender has the right to appeal a wrongful conviction (such as where the judge applied the wrong law).

1 Who has the burden of proof in a criminal case?

What is the reason for this?

2 Define the term ‘the presumption of innocence’ and describe three ways it is upheld in a criminal case.

3 Describe a circumstance in which the accused will have the burden of proof in a criminal case, and identify the relevant standard of proof in that circumstance.

4 Two co-accused have been charged with the murder of a 23-year-old woman. A great deal of forensic evidence has been put to the jury during the trial. Evidence showed:

• the fingerprints of both co-accused were found on the murder weapon

• the woman’s blood was found in one of the co-accused’s cars

• neither of the accused had an alibi (i.e. proof they were somewhere else at the time).

a Imagine you are a member of the jury for this trial. Write down as many ‘fanciful, imaginary or unreasonable’ doubts as you can.

b Describe why each of the doubts you have listed might be considered fanciful, imaginary or unreasonable.

c Write down two or three reasonable doubts you may have based on the evidence provided.

5 In the 1760s, William Blackstone, an English judge, stated that ‘it is better that ten guilty persons escape

than that one innocent suffer’. Do you agree with this statement? Justify your answer.

6 Conduct some individual research on the role of the media and podcasts in investigating the innocence of convicted prisoners. You can use the Adnan Syed and Serial podcast to form your research, but you should also go broader than that.

a Once you have completed your research, come together as a class. Form a line and position yourselves where you land in relation to the following statement: `The media and podcasts should not play a role in deciding whether a person is innocent’. Students who strongly disagree with the statement should stand on one end of the line, and students who strongly agree should stand at the other end. Students who fall somewhere in between should position themselves along the line to represent their point of view.

b As a class, conduct a respectful and informed debate. Support your point of view using information from your research where possible.

c As you discuss and debate the issues:

i Be prepared to move up or down the line if you are persuaded by what someone else presents as a persuasive, credible argument. Also be prepared to move more than once during the discussion to demonstrate any changes in your thinking.

ii Be prepared to challenge any arguments put forward that are not substantiated by any evidence or data.

In this topic, you will learn about:

• the distinction between summary offences and indictable offences.

In Victoria, offences are often classified based on the nature of the offence. For example, there are crimes against the person (such as assault and attempted murder), and crimes against property (such as theft and arson).

Crimes are also classified in terms of their seriousness, that is, as either summary offences or indictable offences.

summary offences a minor offence generally heard in the Magistrates’ Court

Summary offences are minor crimes that are generally heard in the Magistrates’ Court. They are less serious types of crime, such as drink driving, disorderly conduct and minor assaults. The final hearing at which both parties will put their case before a magistrate is known as a hearing (as opposed to a trial in the County Court or Supreme Court). There is no right to a jury trial for summary offences.

Some summary offences are contained in the Summary Offences Act 1966 (Vic), but many are listed in various other Victorian statutes and regulations.

Most crimes that are committed in Victoria are summary offences. The number of criminal cases initiated or commenced and finalised in each of the main Victorian courts for the financial year 2021–22 is set out in Source 1 below. As shown, most criminal cases heard each year in Victoria – more than 95 per cent – are heard in the Magistrates’ Court, which hears summary offences.

Indictable offences a serious offence generally heard before a judge and a jury in the County Court or Supreme Court of’Victoria

Source: Annual reports of the Magistrates’ Court, County Court and Supreme Court, 2021–22.

Source 1 The number of criminal cases finalised in 2021–22 in the main Victorian courts

Indictable offences are serious crimes. Examples of indictable offences include homicide offences (such as murder or manslaughter), sexual offences, some theft crimes and drug trafficking.

As a general rule, offences in the Crimes Act 1958 (Vic) are indictable offences unless the offence is stated in the Act to be a summary offence. Indictable offences are heard in the County Court or Supreme Court of Victoria, and the final hearing is known as a trial. A jury is used to determine guilt if the accused pleads not guilty.

When an accused has been charged with an indictable offence and pleads not guilty, committal proceedings take place in the Magistrates’ Court. Committal proceedings involve several stages, including a final stage, called the committal hearing, at which the magistrate will decide whether there is evidence of sufficient weight to support a conviction at trial.

If the magistrate does find there is sufficient evidence, the accused is committed to stand trial and the case is then transferred to the higher court that will hear the case.

If the magistrate does not find there is sufficient evidence, the accused is discharged and allowed to go free. If further evidence is found in future, the accused can be brought before the court again, because the committal proceeding is not a trial, and no guilt has been decided.

The committal process has several important purposes, including:

• ensuring that cases where there is inadequate evidence do not go to trial

• finding out whether the accused plans to plead guilty or not guilty

• ensuring a fair trial by making sure the prosecution’s case is disclosed to the accused

• giving the accused the opportunity to put forward a case at an early stage and possibly crossexamine witnesses.

There are no committal proceedings for summary offences.

Some indictable offences are known as indictable offences heard and determined summarily

These are indictable (serious) offences, but they can be heard in the Magistrates’ Court as if they were summary (minor) offences. Whether an indictable offence can be dealt with as a summary offence is determined by statute. For example, Schedule 2 of the Criminal Procedure Act 2009 (Vic) lists a number of these offences, which includes theft if the property alleged to have been stolen is a motor vehicle.

The accused will usually choose to have an offence heard summarily, mainly because it is quicker and cheaper to have a case heard in the Magistrates’ Court, and the maximum penalty that can be handed down is less than if it were heard as an indictable offence. The Magistrates’ Court can only impose a maximum of two years’ imprisonment for a single offence, and a maximum of five years’ imprisonment for multiple offences. The court, however, must agree that the offence is appropriate to be heard summarily, and the accused must also agree.

committal proceeding the pre-trial hearings and processes held in the Magistrates’ Court for indictable offences committal hearing a court hearing that is held as part of the committal proceeding in the Magistrates’ Court. At a committal hearing, the magistrate will decide whether there is sufficient evidence to support a conviction for the offence charged indictable offence heard and determined summarily a serious offence that can be heard and determined as a summary offence if the court and the accused agree

SUMMARY OFFENCES

• minor crimes that are not heard before a judge and jury

• heard in the Magistrates’ Court

INDICTABLE OFFENCES

• some can be heard in the Magistrates’ Court as if they were summary offences

• these are called indictable offences heard and determined summarily

Magistrates’ Court

Source 2 The two types of offences: summary offences and indictable offences

• serious crimes heard before a judge and jury

County Court Supreme Court

The VCE Legal Studies

Study Design requires you to know how to distinguish between summary offences and indictable offences. That means you should be able to point out the differences between the two. Try to do more than just use words such as ‘whereas’, ‘on the other hand’ or ‘in contrast’ when explaining the types of offences. Within your answer, try to show how they are different.

The main differences between summary and indictable offences are set out in Source 3 below, which will help you distinguish between the two offences.

nature of offence

Courts that will generally hear the case

Minor crimes

Magistrates’ Court

Entitlement to a jury trial no

Serious crimes

County Court or Supreme Court

Yes (if the accused has pleaded not guilty)

Use of committal proceedings no Yes

name of final hearing hearing

Main statute(s) in which the offences are contained

how it can be heard

Examples

Summary Offences Act and other statutes and regulations

Can only be heard as a summary offence

Disorderly conduct, drinking offences, minor assaults

Source 3 Key differences between summary and indictable offences

3.3

Remember and understand

1 Using an example, define the term ‘summary offence’.

2 Identify the two courts in Victoria that hear and determine indictable offences.

Examine and apply

3 Explain how summary offences and indictable offences are heard and determined differently.

4 Using the Summary Offences Act 1966 (Vic), the Crimes Act 1958 (Vic) and Schedule 2 of the Criminal Procedure Act 2009 (Vic), classify each of the following crimes as summary offences, indictable offences, or indictable offences heard and determined summarily. Justify each response. (See weblinks to each of these Acts on your obook pro.)

a intentionally causing injury to an ambulance officer while the officer was on duty

Trial

Crimes Act

Some indictable offences can be heard summarily

homicide offences, fraud, drug trafficking, sexual offences

b writing obscene words on a public toilet block

c stealing $90 000

d carjacking

e flying a kite to the annoyance of another person.

5 For each of the following scenarios, state whether the person has been charged with an indictable offence or a summary offence. Give one reason for your answer.

a Uri has been charged with stalking and pleaded not guilty. A magistrate committed Uri to stand trial in February 2023.

b Andy has been charged with stealing $40 000 and was found guilty at a hearing in the Magistrates’ Court last week.

c Babak has been charged with intentionally causing serious injury. A jury trial will begin next week.

In this topic, you will learn about:

• the rights of an accused, including the right to be tried without unreasonable delay, the right to silence, and the right to trial by jury.

The protection and promotion of human rights is an important part of Australia’s social and democratic systems. A number of human rights are available to all Australians. These include:

• the right to freedom of political expression

• the right to freedom of movement within Australia

• the right for an individual to enjoy their own cultural and religious practices. Human rights in Australia also include rights available to people accused of crimes. One of these rights is the right to be presumed innocent until proven guilty, as described in the previous topic. In this topic we will examine three other rights available to people accused of crimes.

Human Rights Charter the Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act 2006 (Vic). Its main purpose is to protect and promote human rights international treaty a legally binding agreement between countries or intergovernmental organisations, in which they undertake to follow the obligations set out in the agreement and include them in their own local laws (also known as an international convention)

In the end-of-year examination, you may be expected to explain the three rights shown in Source 1. You should become familiar with, and be able to explain, each of these rights. You can learn other rights, but the three rights in Source 1 are the ones you must know.

In Victoria, many rights are protected by statute, including the Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act 2006 (Vic), otherwise known as the Human Rights Charter (or the Victorian Charter of Human Rights). The main purpose of the Human Rights Charter is to protect and promote human rights. It is designed to ensure that any statute passed by the Victorian Parliament is compatible (i.e. does not interfere) with the human rights set out in the Charter.

The rights protected by the Human Rights Charter are based on those in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1966). This is an international treaty to which Australia is a signatory. Many of the rights in the Human Rights Charter mirror those in the Covenant, but a number have been modified slightly to suit Australia’s existing laws.

Sections 23 to 27 of the Human Rights Charter contain rights that are available to an accused in criminal proceedings. They are only available to human beings (and not, for example, to companies).

In addition to the rights in the Human Rights Charter, there are rights available to an accused contained in other statutes. Three of the rights available to an accused are shown in Source 1, and are discussed further below.

Source 1 Three rights available to an accused in a criminal case

The Human Rights Charter states that a person charged with a criminal offence is entitled, without discrimination, to a guarantee that he or she will be tried without unreasonable delay.

This means that an accused is entitled to have their charges heard in a timely manner, and that delays should only occur if they are considered reasonable. This right is ‘without discrimination’. Every accused person is entitled to this right regardless of their prior convictions or personal characteristics.

their charges heard in a timely manner, and that delay should only occur if it is considered reasonable.

The right recognises that there may be a delay in the case, but that delay must not be unreasonable. The term ‘unreasonable delay’ is not defined, but the reasonableness of any delay will depend on factors such as the complexity of the case and the legal issues involved. For example, it would be reasonable for the prosecution to need more time to prepare for a case involving multiple crime scenes, multiple crimes and multiple accused people with few or no witnesses, as opposed to a case where there was a single incident with multiple witnesses.

This right is supported by Section 21(5) of the Human Rights Charter, which states that a person who is arrested or detained on a criminal charge has the right to be brought to trial without unreasonable delay. This is because, under the Charter, people have a basic right to liberty and security, and accused persons are presumed innocent until proven guilty. Therefore, people should not be held for an unreasonable amount of time while they are awaiting trial.

You do not need to know the section numbers for the rights given under the Charter, but they are provided so you can locate and read the sections for your own learning.

(5) A person who is arrested or detained on a criminal charge

(b) has the right to be brought to trial without unreasonable delay;

(2) A person charged with a criminal offence is entitled without discrimination to the following minimum guarantees:

(c) to be tried without unreasonable delay;

The Human Rights Charter also states that an accused child must be brought to trial as quickly as possible. A child is defined as a person under 18 years of age. Having a trial ‘as quickly as possible’ for an accused child, rather than a trial ‘without unreasonable delay’, which places a greater burden on the prosecution, is justified because of the impact that a trial may have on a child.

One of the cases that considered the right to be tried without unreasonable delay was Gray v DPP, as described in the scenario below.

The accused had been charged with several indictable offences that were alleged to have occurred in november 2007. he was remanded in custody. A co-accused was released on bail . Following the initial charges, additional charges had either been laid or were contemplated in relation to separate events alleged to have occurred before november 2007.

By january 2008, no date had been set for a committal hearing. It was also likely there would be delays before the matter would be finalised, with a potential trial in October or november in 2008. however, there was no certainty about that date.

The accused applied for bail. he ar gued that it was not appropriate for him to continue to be detained, pointing to the delays and uncertain trial date.

justice Bongiorno of the Supreme Court of Victoria referred to the human rights Charter and ordered that the accused be released on bail. In doing so, he noted that it was possible that by the time the trial was held, the accused may have served more time in custody than he was likely to serve in prison as a sanction. he noted that the only remedy the Court could provide to ensure that the accused’s rights under the Charter were met was to release him on bail. The accused was therefore released pending the next hearing.

Gray v DPP [2008] VSC 4 (16 j anuary 2008)

In addition to the right to be tried without unreasonable delay, the accused has a right to silence. The term ‘right to silence’ describes different types of protections given to an accused person to not have to say or do anything. These include:

• the accused has a right to refuse to answer any questions, and does not have to give any information as part of the investigation of a crime

• the accused cannot be forced to give evidence in a criminal trial or answer any questions, file any defence, or call a particular witness as part of a trial.

remand the situation where an accused is kept in custody until their criminal trial can take place bail the situation where an accused is free (not kept in custody) until their criminal trial can take place

The right to silence is protected by common law, which has established:

• an accused person has the right to remain silent

• no adverse inferences (negative conclusions) can be drawn (made) from the fact that a person has not answered any questions or given any evidence. This means it should not be assumed that a person is guilty simply because they have failed or refused to say or do anything in a criminal case.

The right to silence also extends to the following types of situations:

• where an accused later relies on a defence that was not raised earlier, no conclusions should be drawn that the new defence is a ‘new invention’ or is ‘suspicious’ because the accused only just raised it

• where the accused has answered some questions but not others (known as ‘selective silence’), an accused’s choice to answer only some questions cannot be used to conclude guilt.

Statute law now also protects the right to silence. For example, section 89 of the Evidence Act 2008 (Vic) states that unfavourable inferences (negative conclusions) cannot be drawn because a person has failed or refused to answer questions or respond to a matter put to them in an investigation.

When giving directions to a jury, a judge may direct the jury that the accused has a fundamental right to remain silent, and that they should not conclude that the accused is guilty because they did in fact remain silent. A judge must also not suggest to a jury that it can conclude the accused is guilty because the accused did not give evidence or call a particular witness.

There are some exceptions to the right to silence. For example, if the police believe that a person has committed or is about to commit a crime, or may be able to assist in the investigation of an indictable offence, the person must give their name and address if asked to do so.

It was not always the case in Victoria that a person could remain silent and that this would not be held against them. As described in the case below, previously a judge could instruct a jury that they could draw some conclusions if a person remained silent.

Actual scenario

In this 1993 case, Weissensteiner was charged with murdering his two companions while travelling on a boat. his companions disappeared and were never found. The accused remained silent during the investigations and throughout the trial. Upon instructing the jury, the trial judge stated that an inference of guilt ‘may be more safely drawn from the proven facts when an accused person elects not to give evidence of relevant facts that can be easily perceived must be within his knowledge’. To put this another way, the jury was instructed that they could assume guilt more safely when an accused person chooses not to give evidence about something that they could give evidence about. This was because Weissensteiner was the only person who was able to give evidence about what happened to the two people. The jury convicted Weissensteiner, who later appealed to the high Court. The high Court upheld the conviction.

The Jury Directions Act 2015 (Vic) abolished the principle that a judge may give a direction to the jury that an inference of guilt can be drawn when an accused person elects not to give evidence. Section 41 of the jur y Directions Act requires that, if the accused does not give evidence or call a particular witness, the judge may direct the jury about that, and must explain certain matters, including:

• the prosecution has the burden of proof

• the accused is not required to give evidence or call a witness

• the fact that the accused did not do so is not evidence against the accused.

Weissensteiner v The Queen (1993) 178 Clr 217

A trial by jury is where a person’s peers within the community decide the outcome of the case – in a criminal case, whether or not the accused is guilty. This right dates back to well before the Magna Carta in England, established in 1215, which said that no free man shall be imprisoned except by lawful judgment of his peers. The jury system provides the opportunity for community participation in the legal process, and for the law to be applied according to community standards.

The right to trial by jury is not protected by the Human Rights Charter, but rather protected in part by the statute law in Victoria (for state indictable offences), and in part by the Australian Constitution (for Commonwealth indictable offences).

The Magna Carta is a document agreed to by the King of England in june 1215. It contains several rights still considered important today. no one knows how many copies were distributed, but four copies still survive, all of which are in the United Kingdom.

For Victorian indictable criminal offences, the Juries Act 2000 (Vic) requires there to be a jury of 12. The Criminal Procedure Act 2009 (Vic) and the Juries Act also contain provisions about processes in relation to jury empanelment and directions to be given to juries. There is no right to trial by jury for summary offences.

Civil and criminal juries

(2) A criminal trial is to be tried by a jury of 12 or, if the court makes an order in accordance with section 23, by a jury of not more than 15.

While a criminal jury is made up of 12 jurors, the court can order the empanelment of up to three additional jurors, having regard to factors such as the length and nature of the trial (but only 12 jurors will ultimately deliberate on the accused’s guilt). This can help to avoid any disruptions in the trial if, for example, one or more of the jurors gets sick.

The jury will hear the case and will need to reach a verdict on whether the accused is guilty or not guilty. The jurors must make this decision beyond reasonable doubt. You will learn more about criminal jury trials in Chapter 4.

Section 80 of the Australian Constitution states that any person who is charged with a Commonwealth indictable offence is entitled to a trial by jury. In the past, the High Court has interpreted this as a right that cannot be refused by an accused. That is, an accused cannot choose to be tried by judge alone if they have been charged with a Commonwealth indictable offence. Commonwealth indictable offences are serious offences set out in Commonwealth law, and include those described in Chapter 2 (such as organ trafficking, terrorism and importation of illegal substances).

However, section 80 of the Australian Constitution provides only a limited right to trial by jury, because most indictable offences are crimes under state law, and this section only applies to Commonwealth offences. In addition, the Commonwealth Parliament can determine by statute which offences are ‘indictable’.

The trial on indictment of any offence against any law of the Commonwealth shall be by jury, and every such trial shall be held in the State where the offence was committed, and if the offence was not committed within any State the trial shall be held at such place or places as the Parliament prescribes.

A summary of the three rights of the accused described above is contained in the table below.

right to be tried without unreasonable delay

An accused is entitled to have their charges heard in a timely manner. Any delay should be reasonable. Whether a delay is reasonable will depend on the facts of the case and surrounding circumstances.

human rights Charter right to silence

An accused has the right to remain silent when questioned or when asked to give information in the investigation. They also have the right to stay silent in a criminal proceeding and not be required to give evidence or call a particular witness. As a general rule, the exercise of the right cannot be used against them.

Common law and statute law (including the Evidence Act)

right to trial by jury

A person charged with an indictable offence is entitled to be tried by their peers. The jury will be made up of 12 members of the community. The right does not extend to people charged with summary offences.

Source 6 A summary of three rights of an accused

Remember and understand

1 a Outline three rights available to an accused in a criminal proceeding.

b Describe any exemptions or exceptions that apply to each right.

2 Describe the role of parliament in upholding one of the rights of an accused.

3 Define the term ‘unreasonable delay’, and outline what delays may be considered ‘reasonable’.

Examine and apply

4 Your friend has been charged with drink driving, and believes she is entitled to a jury trial under the Australian Constitution. Is she correct?

Justify your answer.

5 In Gray v DPP, explain how Justice Bongiorno attempted to remedy the fact that there may not be a timely trial.

Juries Act (for state indictable offences) and Section 80 of the Australian Constitution (for Commonwealth indictable offences)

Reflect and evaluate

6 Conduct a debate or engage in a class discussion about one of the following two statements. When conducting the debate or discussion, ensure there is reference made to the principles of justice.

a All criminal trials and hearings should be determined by a jury.

b The jury should be entitled to conclude that an accused person is guilty if they are the only ones that know what happened in a crime, but refuse to say anything or give any evidence.

7 You have met several people who do not believe that an accused should have any rights. They refer to a number of criminals who have recently been convicted for violent crimes. Create a list of three arguments you might use to convince those people that rights are necessary for everyone.

victim a person who has suffered directly or indirectly as a result of a crime Victims’ Charter the Victims’ Charter Act 2006 (Vic), which recognises the impact of crime on victims and provides guidelines for the provision of information to victims

In this topic, you will learn about:

• the rights of victims, including the right to give evidence using alternative arrangements, the right to be informed about the proceedings, and the right to be informed of the likely release date of the offender.

Although the victim is not a party in a criminal case, there has been widespread recognition that not only should there be rights for an accused, but victims of crime should also be recognised and treated with respect and dignity and as participants during a criminal case.

Victims are recognised by several statutes in Victoria, including the Victims’ Charter Act 2006 (Vic), known as the Victims’ Charter. Some of the objectives or key principles of the Victims’ Charter are to:

• recognise the impact of crime on victims

• recognise that victims should be offered certain information during the investigation and prosecution process

• help reduce the likelihood of secondary victimisation that may be experienced by the victim as a result of their interaction with the criminal justice system.

The Victims’ Charter defines ‘victim’ broadly. Depending on the crime, a victim can include:

• a person who has suffered injury as a direct result of a criminal offence (often called the ‘primary victim’)

• a family member of a person who has died as a direct result of a criminal offence

• a family member of a person who is under 18 years of age or is incapable of managing his or her own affairs because of mental impairment, and that person has suffered injury as a direct result of a criminal offence

• a child under the age of 16 years who has been groomed for sexual conduct, as well as that child’s family.

In the end-of-year examination, you may be asked about the rights of victims listed in Source 1. You should be able to explain each of the rights. You can learn more than these three, but you must know the ones in Source 1.

The Victims’ Charter sets down principles such as respectful treatment of victims, respect for victims’ privacy, and ensuring victims are given information about any criminal case brought to court. However, a breach of those principles does not entitle the victim to take civil action to enforce them.

In addition to the principles contained in the Victims’ Charter, several other statutes provide some protections for victims.

Three of the rights given to victims are listed in Source 1. Each of these is discussed further below. RIGHTS

Source 1 Three rights available to a victim in a criminal case

AVAILABLE TO A VICTIM The right to give evidence using alternative arrangements The right to be informed about the proceeding

In some criminal cases, a victim may be a witness in the criminal case. If so, they may have to give evidence in support of the prosecution’s case against the accused.

A number of sections in the Criminal Procedure Act aim to protect certain witnesses in certain types of cases. In particular, the Criminal Procedure Act allows for alternative arrangements to be used for witnesses in certain cases; that is, different ways in which a witness can give evidence. These are described below.

The court can direct alternative arrangements to be made for any witness who gives evidence in criminal proceedings that relate to a charge for:

• a sexual offence

• a family violence offence

• an offence for obscene, indecent, threatening language or behaviour in public

• an offence for sexual exposure in a public place.

The arrangements can be made at any stage of the criminal proceeding, including any appeal or rehearing.

The types of alternative arrangements are as follows:

• The witness may give evidence from a place other than the courtroom by means of closedcircuit television (or other like facilities) to enable communication between that place and the courtroom. The evidence will be recorded.

• Screens may be used to remove the accused from the direct line of vision of the witness.

• A support person may be chosen by the witness to be beside the witness while the witness is giving evidence, so that they can provide emotional support. The court needs to approve the witness chosen.

• Only certain persons (specified by the court) may be allowed in court when the witness is giving evidence.

• Legal practitioners may be required not to be formally dressed in robes.

• Legal practitioners may be required to be seated while asking the witness questions. There are some situations when a court must direct the use of certain alternative arrangements. For example, if the witness is a complainant in a criminal proceeding that relates to a charge for a sexual offence or a family violence offence, the court must direct the use of closed-circuit television or other facilities unless the prosecution applies for the complainant to give evidence in the courtroom, the complainant is able and wishes to do so, and the complainant is aware of their right to give evidence in another place.

alternative arrangements processes put in place by a court to protect vulnerable witnesses when they are giving evidence in cases of sexual offences or family violence

complainant a person who makes a formal legal claim that another person has committed a criminal offence against them

The purpose of the use of alternative arrangements is to try to reduce the trauma, distress and intimidation that a witness may feel when giving evidence. This is particularly so in cases involving charges for sexual offences and family violence, where the trauma and injuries suffered may be significant, and witnesses are at greater risk of suffering secondary trauma because of giving evidence about what happened.

In the following scenario, alternative arrangements were put in place in relation to an ongoing, sensitive case in Victoria.

Actual scenario

In this case, a former principal was accused of sexually abusing three of their students nearly 20 years ago. At a committal hearing in 2021, the three complainants gave evidence in a closed court, which was described as now being standard practice for sexual assault cases in Victoria. The court remained closed for the rest of the day. The complainants also had a support person in the same room as they gave evidence. The court was opened later that week to the media and other parties when members other than the complainants gave evidence.

The accused was committed to stand trial, and pleaded not guilty on all counts when the hearing commenced in February 2023.

In April 2023, the accused was found guilty of 18 charges, including rape and indecent assault against two of the complaints. The accused was acquitted of nine charges, including all five charges relating to the third complainant.

The Victims’ Charter recognises that people adversely affected by crime should get certain information about the proceeding and about the criminal justice system.

The Victims’ Charter requires investigatory agencies, prosecuting agencies and victims’ services agencies (which includes police officers, the DPP and the Victims of Crime Commissioner) to provide clear, timely and consistent information about support services, possible compensation entitlements and the legal assistance available to persons adversely affected by crime.

Source 3 Fiona McCormack is the Victims of Crime Commissioner, whose job it is to be a voice for victims of crime.

In addition, the Victims’ Charter requires an investigatory agency (a body which conducts a criminal investigation, such as Victoria Police) to inform a victim, at reasonable intervals, about the progress of an investigation into a criminal offence. The information does not need to be given if it may put the investigation at risk, or if the victim chooses not to receive that information.

Once a prosecution has commenced, the Victims’ Charter requires the prosecution to give a victim the following information:

• details of the offences charged against the person

• if no offence is charged, the reason why

• how the victim can find out the date, time and place of the hearing of the charges

• the outcome of the criminal proceeding, including any sentence imposed

• details of any appeal.

The victim must also be told that they are entitled to attend any court hearings. These requirements recognise that victims may wish to be kept informed about a criminal case that has affected them. They may want to know what offences the accused has been charged with, the verdict, and the sanction imposed, as they want to see justice done.

A person who is a victim of a criminal act of violence may apply to be included on the Victims Register. The criminal acts of violence are identified in Source 4.

Victims Register a register (i.e. database) maintained by the state of Victoria set up to provide the victims of violent crimes with relevant information about adult prisoners while they are in prison (e.g. the prisoner’s earliest possible release date)

A person must apply to be included on the Victims Register. Once they are registered, the victim may receive certain information about an offender who has been imprisoned, including notification of the release of the prisoner on parole at least 14 days before the release.

Other rights are also available to a victim on the Victims Register, including the right to know the length of the sentence, the right to be told if the offender escapes from prison, and the right to make a submission if the imprisoned offender may be released on parole.

parole the supervised and conditional release of a prisoner after the minimum period of imprisonment has been served

A summary of the three rights of victims is shown in the table below.

right to give evidence using alternative arrangements

Victims who are witnesses in some cases, such as sexual offence and family violence cases, are able to give evidence using alternative arrangements. Those arrangements include:

• giving evidence used closed-circuit television or other like facilities

• the use of a screen between the accused and the witness

• the use of a support person for the witness

• only allowing certain people to be in the court while the witness is giving evidence

• requiring legal practitioners not to be formally dressed in robes

• requiring legal practitioners to be seated while asking the witness questions.

right to be informed about the proceedings

Victims are entitled to be informed at reasonable intervals about the progress of an investigation into a criminal case (unless they do not want that information, or that information may jeopardise the investigation). Once a prosecution has commenced, victims should be informed about the charges, hearing dates and times, outcomes, sentences and details of any appeal.

Victims’ Charter right to be informed of the likely release date of the accused

If a person is a victim of a criminal act of violence and are on the Victims register, they may receive information about the likely release date of the imprisoned offender.

1 Are all victims entitled to receive information about the likely release date of a prisoner? Explain your answer.

2 Will a victim always be entitled to information about an investigation? Justify your answer.

3 Create a poster or visual diagram that shows the alternative arrangements that may be available to a witness giving evidence in a sexual offence or family violence case. Try to think of a way to represent those arrangements that will help you remember them.

4 For each of the scenarios below, state whether each of the witnesses is entitled to the protections they seek.

a Darryl saw Yasmine disturbing a place of religious worship, which is a summary offence. Darryl has been called as a witness and he wants to give evidence by way of closed-circuit television.

b Maya is a witness for the prosecution in a proceeding where Kalani has been charged with singing an obscene song (the offence of using

Victims’ Charter and the Corrections Act 1986 (Vic)

obscene, indecent or threatening language or behaviour). Maya wants her mother by her side while she is giving evidence.

c Anis witnessed a murder, for which Dechen has been charged. Anis does not want any legal practitioners formally robed while he is giving evidence.

d Harriet is the complainant in a family violence case. She agrees to give evidence in the courtroom, but she doesn’t want to see the accused when she does so.

5 A breach of the Victims’ Charter does not entitle the victim to take civil action to enforce those rights. Do you think it should? Discuss with a classmate.

6 Access Chapter 8 of the Victorian Law Reform Commission’s (VLRC) report ‘The Role of Victims of Crime in the Criminal Trial Process’ (see weblink on your obook pro).

a Identify three problems or issues that the VLRC identified in relation to alternative arrangements.

b Discuss as a class.

1 Many rights are available to the accused and to victims, but make sure you know those three that are listed in the Study Design for the accused and for victims, and be able to explain each of them. You could be asked a specific question about each of those rights on the exam (there are six in total).

2 One of the most common errors students make is stating that a person has a right to a trial by jury under section 80 of the Australian Constitution. That is not entirely correct, and depending on the question, this could result in not getting full marks for a response. The right to trial by jury under the Australian Constitution is only for Commonwealth indictable offences. For state indictable offences, statute law provides the right to trial by jury.

3 One thing you need to avoid in legal Studies is writing ‘circular’ definitions; that is, using the same words to describe a phrase or right. For example, don’t describe ‘alternative arrangements’ as ‘arrangements to give evidence in alternative ways’. Instead, write something like ‘different methods or measures put in place to allow witnesses in certain types of cases to give evidence’.

The following questions have been arranged in order of difficulty, from low to high. It is important to practise a range of questions, as assessment tasks (including the exam) are composed of a variety of questions. A great way to identify the difficulty of the question is to look at the command term (or terms) used in the question and the mark allocation. Work through these questions to revise what you have learnt in this chapter.

Difficulty: low

1 Distinguish between an indictable offence and a summary offence.

Difficulty: medium

(3 marks)

2 Sometimes, limitations may need to be imposed on the rights of the victims’. With reference to one right of victims, explain what this statement means.

Difficulty: high

3 Discuss the extent to which there is a right to a trial by jury in Victoria.

(4 marks)

(6 marks)

Students should read the information at the beginning of the chapter relating to the learning outcome, key knowledge and key skills before attempting this assessment task.

Use stimulus material, where provided, to answer the questions in this section. It is not intended that this material will provide you with all the information to fully answer the questions.

Georgia, 23, is the victim of a sexual offence. Victoria Police has charged Simon, Georgia’s ex-boyfriend, with four counts of sexual assault. He has pleaded not guilty.

The DPP has three witnesses in its case against Simon: Georgia, Georgia’s friend Kostas, who was at the premises at the time of the sexual assault, and Georgia’s mother, Sally, who was the first person to see Georgia when she got home. Sally helped Georgia get to the local hospital.

All three witnesses have been provided with information about Simon’s upcoming trial, including the date and time, and Georgia has found staff members at the OPP to be helpful. Georgia is nervous about giving evidence and is not sure about the way she can give that evidence. She does not want to see Simon during the trial or have any direct communication with him. Sally is happy to be in the courtroom while giving her evidence, but she is nervous about the formalities that come with a trial. Kostas wants to have a group of friends with him while he gives evidence.

Simon wants a closed trial because he does not want his name publicised any further, and he wants the County Court trial to be heard quickly. He is already frustrated by all the delays that have occurred.

1 Identify the complainant, the prosecution and the accused in the above scenario.

(3 marks)

2 has Simon been charged with summary offences or indictable offences? justify your answer.

(3 marks)

3 Identify the party that has the burden of proof in this case, and describe the extent to which that party needs to prove the case.

(3 marks)

4 Simon believes he is entitled to a right to trial by jury because of the Australian Constitution. Is this true? justify your answer.

(4 marks)

5 Simon wants a quick trial that is closed to the public and does not want to give evidence. Explain whether he would be entitled to all those rights.

(6 marks)

6 Explain whether there are rights available to Sally, Kostas and Georgia to give evidence in a way that addresses their concerns.

(6 marks)

Total: 25 marks

Use the success criteria in the table below to rate how well you understand each concept as ‘Confidently’, ‘Mostly’, or ‘not really’. If you’re not feeling confident, use the revision links to revisit the concepts.

I can …

Confidently Mostly Not really revision link

• define and use key legal terminology. revise key terms using Quizlet for this chapter on your obook pro.

• explain the key principles of the criminal justice system, including the:

– burden of proof

– standard of proof – presumption of innocence.

Go back to topic 3.2.

• distinguish between summary offences and indictable offences. Go back to topic 3.3.

• explain the rights of an accused in the criminal justice system, including the:

– right to be tried without unreasonable delay – right to silence

– right to trial by jury.

• explain the rights of victims in the criminal justice system, including the:

– right to give evidence using alternative arrangements

– right to be informed about the proceedings

– right to be informed of the likely release date of the offender.

Go back to topic 3.4.

Go back to topic 3.5.

Northern Territory

Melissa Wearne

E: melissa.wearne@oup.com

M: 0447 557 931

Western Australia

Graeme Jordan

E: graeme.jordan@oup.com

M: 0417 308 540

South Australia

Renee Kennedy

E: renee.kennedy@oup.com

M: 0418 857 546

Victoria

Alicia Giaquinta

E: alicia.giaquinta@oup.com

M: 0411 759 611

Caitlin Hansford

E: caitlin.hansford@oup.com

M: 0411 759 659

Paul McCallum

E: paul.mccallum@oup.com

M: 0423 241 455

Tasmania

Caitlin Hansford

E: caitlin.hansford@oup.com

M: 0411 759 659

Queensland

Chris Lowcock

E: christopher.lowcock@oup.com

M: 0428 949 935

Melissa Wearne

E: melissa.wearne@oup.com

M: 0447 557 931

New South Wales

Caly James

E: caly.james@oup.com

M: 0413 745 855

Australian Capital Territory

Caly James

E: caly.james@oup.com

M: 0413 745 855