President: Christopher Collins

Edited by William Gough

President: Christopher Collins

Edited by William Gough

“What is dead may never die, but rises again harder and stronger” -Religious saying of the Ironborn

It is with great pleasure that I welcome you to the Hilary 2025 edition of Blueprint! For those who don’t know, Blueprint is OUCA’s magazine, featuring some of the best articles from the term. Unfortunately, it has been several terms since one has been published, so consider this a ‘bumper’ edition, also including articles from Hilary, Trinity and Michaelmas 2024.

2024 was also the centenary year of OUCA’s existence, so I have decided to give this edition a loose theme. Almost all of the articles involve looking back at the Conservative Party’s past or looking forward to the future of the Party. It is no secret that the Conservatives are at a crossroads after the disastrous July result. However, a magazine such as this is the perfect outlet for expressing ideas, both retrospective and prospective. The emphasis on history is also why I have decided to style this edition as if it were a series of old archived files.

Finally, I would like to give my thanks to several people who helped make this Blueprint edition possible. My immediate predecessors (Mitchell Palmer, Edmund Smith, George Kenrick), as well as Charlie Chadwick (the last Publications Editor to have an edition published to the website), have all provided me with invaluable resources and advice, for which I am truly grateful. I would also like to thank everyone who contributed to this edition of Blueprint, in particular the Rt Hon. Laura Trott MBE MP, who has written a fascinating piece on Conservative education policy.

William Gough, St Hilda’s College

The Publications Editor

Dear Member,

I am absolutely thrilled to welcome you to the unparalleled literary experience that is Blueprint, the Oxford University Conservative Association’s official propaganda magazine. OUCA is the principal forum for Conservative thought at the University of Oxford, and, as we enter our second century, our commitment to spread the word and make the case for free markets, free speech, and free people has never been more important.

As we recover from a uniquely challenging General Election result, now is the time for us to have the exciting and interesting conversations about the future of our party and our country. Victory in 2029 will require purpose and precision: we must be clear about what we believe and be determined to deliver it. There is no better place to debate these ideas than Oxford, the greatest university in the whole history of the world.

At OUCA, we are proud to provide a home for Conservatives of all stripes. Whether you are on the right or whether you are, quite simply, on the wrong, we believe in encouraging all (intelligent) opinions to be expressed. As you indulge in this delectable buffet of sound opinions, I hope that you will find something to please your palate.

I would like to thank William, our Publications Editor, for compiling this special edition, and all those who contributed to it. Most importantly, thank you so much for reading it.

With warmest wishes, and bon voyage,

Chris Collins, Corpus Christi College

The President

By the Rt Hon. Laura Trott MBE MP, Pembroke College

The UK is home to some of the best universities in the world, and for hundreds of years, they have been instrumental in promoting our traditions and our values. They have played a role in fostering debate, sharing ideas – even if contentious – and they have advanced society in the process.

As a proud alumna of Oxford, I look back with fond memories of my time at Pembroke College. ‘ Those three years changed my life. However, I am deeply concerned about the future of our universities, and the experience of students, under the current Labour Government.

Since taking office in July, Labour’s approach to higher education has been nothing short of chaotic. Instead of building on the progress made under the Conservatives - expanding opportunities, improving quality, and cracking down on low-value degrees - Labour is pushing an agenda that will leave young people worse off, saddled with more debt, and facing fewer opportunities.

Let’s start with tuition fees.

In opposition, Starmer promised to abolish them altogether, making

it a central plank of his leadership bid. In July last year, at the time of the King’s Speech, the Secretary of State said that she had “no plans” to increase tuition fees. And, the Chancellor repeatedly claimed after her Budget in October that there was “no need to increase taxes further.”

However, just one month later the Labour Party came to the House of Commons and announced an increase in tuition fees for the first time in eight years - a hike in the effective tax that graduates have to pay.

The Government ignored the warnings from universities and student groups that higher fees will do nothing to improve student outcomes, and instead piled additional financial pressure on young people already facing a cost-of-living crisis.

While the impact of this is felt by all, I am particularly worried about what this will mean for the most disadvantaged pupils. I was the first in my family to go to university, and we must ensure that increased fees do not deter those from poorer backgrounds.

And the irony is that this fee hike will not help with the funding pressures universities face. The increase in employer National Insurance contributions has added a massive £372 million to the sector’s pay bill—wiping out almost all the additional funding universities gained from tuition fee rises. Instead of supporting institutions to improve research, teaching, and student experience, extra revenue is now swallowed up by national insurance hikes. National insurance hikes which the now Chancellor and Prime Minister pledged throughout the election campaign, were not needed.

When we were in government, the Conservatives invested nearly £490 million in skills training and infrastructure to upgrade universities and colleges across the country. We strengthened our International Education Strategy to attract more students from ‘

around the world, boosting the UK’s reputation as a global leader in higher education. And we introduced degree apprenticeships, giving students from all backgrounds the opportunity to gain valuable skills and workplace experience without being burdened by traditional tuition fees.

But it is not just around funding that Labour is making mistakes. Another worrying development has been around free speech.

During our time in government, the Conservatives introduced The Higher Education (Freedom of Speech) Act 2023, which was passed by Parliament prior to the election. The Act ensured our universities remained places of open debate, where challenging views could be heard and discussed. By the end of the Act’s passage through both Houses, the Labour party had agreed in principle with the need for it. However, immediately after the election, Government sources said the Act was a Tory “hate speech charter” and paused its implementation. It should have been obvious from the outset that this was a mistake. But this government once again doubled down, rolling out tired tropes about "hate speech" while ignoring the real damage being done to academic freedoms.

For gender-critical academics and others targeted for their views, Labour’s inaction has been devastating. Many have faced harassment, professional blacklisting, and financial ruin simply for expressing lawful opinions. Some have even had to remortgage their homes to cover legal fees—burdens they would never have had to bear had the Act been enforced.

Last month the Government finally confirmed plans to reintroduce a piece of legislation aimed at protecting free speech on university campuses, but it removed provisions allowing individuals to sue ‘

universities directly and has exempted student unions from the duty to uphold and promote freedom of speech and academic expression. Key questions therefore remain; what consequences will universities face if they do not protect free speech, and what is happening to regulate overseas funding?

Labour’s handling of this has been a disaster from start to finish. Instead of defending free expression, they caved to activist pressure. Instead of ensuring universities remain spaces for open debate, they emboldened cancel culture. Instead of listening to world-leading academics, they ignored them - until public embarrassment forced them to act.

Free speech is a fundamental principle of liberal democracy and the Labour party’s willingness to abandon it for political convenience should concern us all.

As the Shadow Education Secretary, I will work every day to scrutinise the decisions this Government is taking to ensure they do not fail our next generation. Education holds a vital role in the Conservative mission to encourage and reward aspiration. Getting the right skills and good qualifications can make all the difference in helping people to climb the ladder of opportunity and we must ensure our universities remain a critical part of this journey.

By Mitchell Palmer, New College

In the 1970s, Margaret Thatcher sought to restore the Conservative Party’s faith in free enterprise after years of Butskellist complacency which had allowed the state to expand and the individual to shrink, while the Tory Party stood by passively. With a copy of F. A. Hayek’s Constitution of Liberty (1960) in hand, she told the Conservative Research Department that “this is what we believe”. And yet, as a postscript to the same book, Hayek had written an essay entitled ‘Why I am Not a Conservative’.

So, is it possible to be both a Conservative (with a capital C) and a [Hayekian] liberal (with a small l)? Despite the title of Hayek’s essay, Mrs Thatcher clearly thought so. To an American, this would be an absurd question: their corruption of our shared language has placed these two concepts in fundamental opposition. To others, it might seem like a pointless dispute: a terminological debate only interesting to fedora-wearing Redditors and political philosophers with little else to do. But it has a crucial bearing on the identity of our party: despite our nominal attachment to free enterprise and individual liberty, the most recent Conservative government collected a bigger portion of Britain’s national income in taxation than any government since ‘

Attlee’s. The same Conservative government proposed a rolling prohibition on smoking. Conservative MPs regularly campaign against property owners’ rights to build on their own land. Even if liberalism and Conservatism are compatible, they are not currently synonymous. It remains for us liberal Conservatives to make the case for a freedom-enhancing, state-shrinking Conservatism.

Before making the case for returning the Conservative Party to Hayekian liberalism, it is worth understanding why - or indeed, whether - he rejected conservatism. Professor Hayek did not, for instance, reject tradition. He argued for spontaneous order and slowly evolved institutions like the English common law, which he adored. Although he did argue for European federalism, he saw it as a necessary constraint on state action, rather than cheering for a new super‘ ‘

state. Hayek’s problem with conservatism was that, ‘by its very nature[,] it cannot offer an alternative to the direction in which we are moving”. Conservatism, defined only as an opposition to drastic change, is just a brake – not a steering wheel. For advocates of personal liberty faced with the threat of aggressive collectivism, conservatism alone cannot be the answer, because it has “invariably been the fate of conservatism to be dragged along a path not of its own choosing”.

Unfortunately, under the last Conservative government, Hayek was proven right. Even when it espoused liberalism, it did so ineffectively. Ministers deployed invective against the progress of woke-ism and statism in the newspapers and yet offered little alternative. Conservatives complained about the creeping burden of taxation, but refused to stand for the spending cuts needed to reverse course. ‘

We grumble about Blairite vandalism of the constitution and yet the only constitutional change repealed by the most recent Tory government was one introduced with our consent by our erstwhile coalition partners (the Fixed Term Parliaments Act).

Mrs Thatcher rejected this defeatism: she sought to reverse - and indeed change - course. A better Britain was possible, but only if we applied the old values of familial responsibility and individual liberty to a new world with new vigour. That is the synthesis of conservatism and liberalism that the Conservative Party ought to stand for. Only then can Britain’s national decline be reversed.

However, anyone making the case for radical liberal conservatism today must deal with the Truss problem. The former Prime Minister, the Rt. Hon. Liz Truss MP, espoused very similar ideas to those in this essay. In her victory speech after winning the Tory leadership, Ms Truss highlighted ‘freedom, ... the ability to control your own life, ... low taxes, ...[and] personal responsibility’ as the beliefs of the Conservative Party. Unfortunately, her ham-fisted implementation of these ideas may have seriously damaged their credibility for some time. However, we should not abandon the ideas: Ms Truss simply followed the wrong recipe for the right dish.

Liberal conservatism means acknowledging the constraints imposed by reality. That is what distinguishes mature Conservative reform from naïve utopianism. In particular, Ms Truss failed to realize that the borrowing constraints on the British government are a lot tighter than those which faced President Reagan during the 1980s, when he tried a similar recipe of deficit-increasing tax cuts. Sadly, sterling is no longer the world’s reserve currency. Thus, British governments cannot rely on foreign investors with a seemingly insatiable demand for safe reserve assets to soak up their irresponsible borrowing. That vulnerability was compounded by the Bank of England’s simultaneous programme of quantitative tightening, which flooded ‘

the market with British government bonds, as well as a hidden vulnerability of the pension sector to rapid interest rate rises.

But the problem wasn’t Ms Truss’s tax cuts per se: instead, it was the gargantuan, unfunded, and irresponsible combination of tax cuts and energy subsidies. Indeed, more than half of the extra £80 billion the Truss administration planned to borrow in year 1 of their minibudget was to go towards extra spending. Ms Truss has raised problems with the costings of those subsidies, but that is quibbling. These were untargeted subsidies that created terrible incentives for energy use and huge fiscal risks for the Crown accounts. The German government’s scheme of capped subsidies based on 80% of previous energy usage, rather than current consumption, would have been a much better approach.

A comparison with Mrs Thatcher is instructive. Few would accuse her of excessive pragmatism, but her earliest budgets actually increased taxes. She recognized that a government deficit was not an artificial accounting conceit (contra Truss who called balancing the budget “abacus economics”), which could be ignored with high enough growth. A government deficit mortgages the future to pay for current frivolities; it crowds out private sector borrowing and investment; it pours fuel on the inflationary fire. She knew that getting the debt and deficit under control was the first task of a reformist Tory government. Moreover, she prioritized supply-side reform, like destroying inefficient norms of patronage and privilege the City of London and crushing the recalcitrant trade unions, to ensure that the economy would be flexible enough to absorb the newly-unleashed energy of the private sector.

If Ms Truss had instead adopted a more Thatcherite policy, that prioritized spending restraint and freeing up the market to build new power stations and houses, we might still have a free market Conservative as our Prime Minister. As it happened, her rush to prove ‘

herself to the electorate with a sugar-hit of high spending and low taxes may have doomed the entire liberal conservative project for some time. We can only hope that our chance will come again soon.

Congratulations to Lord Hague (the ex-President, Magdalen College) on becoming Oxford University’s 160th Chancellor!

By George Kenrick, Christ Church

“Having been for a century the natural party of Government, with occasional periods of progressive alternative, we could be in a position where we have long periods of Labour with occasional periods of Conservative Government” - The Lord Finkelstein in preparation of what would be the cataclysmic 1997 General Election.

The Conservative Party has been the party of governance, consistently dominating throughout the late 19th and 20th centuries. It is one of the oldest political movements in the world: a bastion of British parliamentary politics, guiding us through both the highs and lows of modern British history. Some may be fearful for the future of the Conservatives after the disastrous 2024 General Election, but the Party has frequently been tried and tested throughout its history. To understand the Conservative Party in its current state, what it stands for, and what is hoped to be achieved in (hopefully) a brief stint of opposition, we have to go back and consider the rich and varied history of the Conservative Party

The Party’s origins are disputed. Some historians consider the Party to be an offshoot of the Tories, a political faction formed after the 1679 exclusion crisis, where they opposed efforts to exclude James, Duke of York from the succession on the grounds of his Catholicism. ‘

This grouping dissipated after the succession of George I in 1714, though later re-emerged in 1783 under William Pitt the Younger and the Earl of Liverpool. The Tories and the ‘Independent Whigs’ who supported these governments have been seen as a ‘proto’ Conservative Party. After the Representation of the People Act of 1832, however, the Tory ‘party’ was reduced to 175 MPs.

Nonetheless, the pivotal moment for the creation of the Conservative Party came only a couple years later under Robert Peel with the creation of the Tamworth Manifesto in 1834. In it, the modern Conservative Party was conceived as an evolution of the Tory and Independent Whig groupings in parliament. The name ‘conservative’ grew in popularity and was formally adopted under the Tamworth Manifesto. Furthermore, the Tamworth Manifesto accepted the Reform Act of 1832 and promised to preserve the tenets of Protestantism. Peel also pledged a review of civil and ecclesiastical institutions and the correction of grievances. In other words, the Conservatives would reform to survive, with the acceptance of the widening franchise being essential for the Conservatives to remain a credible force within politics.

The additional widenings of the franchise in the late 19th Century ensured further changes in tactics for the Party. The Conservatives oversaw an expansion of the franchise in 1867 under the Earl of Derby and Benjamin Disraeli, but later opposed William Gladstone’s 1884 Reform Act. However, they eventually conceded in its passage. In 1886, a further change in the Party occurred, as it entered into coalition with the Duke of Devonshire and Joseph Chamberlain’s Liberal Unionist Party. This ushered in a period of Conservative and Unionist dominance under the Marquess of Salisbury and Arthur Balfour. They held power for all but three of the nearly two decades between 1886 and 1905, before a split over free trade ensured the Party’s defeat in the 1906 election. In 1912 the Party formally merged with the Liberal Unionists, resulting in the official creation of the Conservative and Unionist Party. ‘

During the First World War, the governing Liberal Party imploded, ushering in another period of Conservative and Unionist dominance, cemented by a landslide victory in 1918. The Labour Party went on to replace the Liberals as the Conservatives’ main opponent, leading to a growing distaste for socialism within the Party. With the exception of a few years where the Labour Party governed under Ramsay MacDonald, the Conservatives were the dominant party in the interwar years. In 1940, a National Government was formed under Winston Churchill, and in 1945, the Party was firmly ousted from power by Labour under Clement Attlee.

The 1945 election defeat caused another reshaping of Conservative doctrine, leading to the post war consensus, which emphasised a mixed economy and labour rights. This came to some avail as in 1951 Churchill was back, albeit with a slim majority. The Conservative governments of the 1950s accepted the creation of the welfare state under Attlee and were conciliatory towards trade unions. The Party governed for 13 years until 1964. The first formal leadership election was held in opposition in 1965 and was won by Edward Heath. Heath later won a general election and was in government from 1970-74, ‘

though due to a failure to control the trade unions in this period and a poorly timed snap election, he was ousted from power.

In 1975, a revolution in the Party occurred: Margaret Thatcher was elected to the leadership of the Party. Her audacious plan to reject the post-war consensus and promote the free market, small government and social tradition ensured her hegemony from 19791990. She privatised industry left, right and centre, changing the face of Britain, turning it from a failing industrial economy to a booming tertiary sector powerhouse. Mrs Thatcher’s greatest faux pas was the proposal of a poll tax in 1989 which, combined with party divisions, led to a leadership challenge by Michael Heseltine and her resignation in 1990. John Major won this election, and he was able to just about retain his parliamentary majority in 1992. However, not long after this, the suspension of British membership of the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) caused a severe recession known as Black Wednesday. Additionally, the Party of the 1990s was internally divided and constantly infighting. Complemented by bouts of sleaze, this created a recipe for disaster. In 1997, the Conservatives suffered their worst defeat since the 1906 election.

The interregnum period of Conservative governments from 19972010 have been seen as the ‘wild’ years of the Party, with it changing leaders every couple of years. After Major resigned, the Party would go through three more leaders (William Hague, Iain Duncan Smith, and Michael Howard), before settling on David Cameron. Cameron’s leadership saw another shift in ideology, with the adoption of a more socially liberal form of Conservativism (which manifested in the form of gay marriage and reforms to education) and the promise to enact austerity measures in the wake of the 2008 Financial Crash. Cameron won in 2010 and the Conservative Party was finally back in government. ‘

Famously, in 2016, Cameron called for a referendum on Britain’s membership within the EU, as had been promised in the 2015 Manifesto. Britain voted to leave 52-48%, which led to Cameron’s resignation. Theresa May then took the helm, but failed to successfully pass an EU withdrawal deal which would appease all members of the Party. Brexit continued to dominate the British political sphere until the election of Boris Johnson to premiership in 2019. He held an early election and won the largest Conservative victory since 1987. Johnson took Britain out of the EU and was doing very well in office, until the Covid fiasco of 2020, where Johnson allegedly broke his own covid rules. He was prompted to resign in 2022. Liz Truss was then chosen to lead: a catastrophe for the Conservative Party as she resigned after only 49 days. Rishi Sunak took over after Truss and led the Party and the country until 2024.

The Conservative Party has long been characterised by change; it is a malleable party which has always adapted to its political environment. Doomsayers will argue that the next few years will spell the end of the Party, but the ability to adapt to the times is intrinsic to the Party’s history. I have hope that despite the projections and the polls, the Party will continue to exist in the coming years. It has endured for nearly two centuries; may it continue for two more!

By Maya Kapila, Christ Church

Then the Ordinary Member, now the Communications

Director

Women have long been instrumental in shaping and supporting the Conservative Party, playing a vital role in its evolution and success. This article will take a look at the ever changing role women have played in the history of the Party, from the early days of the women’s suffrage movement to the Party’s future under Kemi Badenoch.

Between 1880 and 1928, the Conservative Party had a complex relationship with the question of women’s suffrage. On the one hand, every single Conservative leader since Disraeli had expressed at least some sympathy for granting women the vote, and on 14 occasions, party conferences at different levels had indicated support for women’s suffrage. The Conservative and Unionist Women's Franchise Review made the pragmatic political case for Conservative backing of the cause, arguing that the enfranchisement of propertied women would prove electorally advantageous to the party (particularly in the light of growing calls for the franchise to be extended to all adult men). Indeed, women’s support for the Conservatives had already proved an effective and powerful force: ahead of the 1885 election, the Primrose League (a Conservative campaigning organisation) had relied heavily on the canvassing and ‘

campaigning efforts of several thousand female campaigners. On the other hand, the Conservatives were - unsurprisingly - reluctant to drastically reshape the electorate while in power in the late Victorian and early Edwardian periods; as the governing party, they had very little incentive to disrupt the status quo by enfranchising the female population.

Regardless, women over 30 (who met certain property requirements) were granted the right to vote by the 1918 Representation of the People Act, and ten years later, it was a Conservative government which - on the basis that most women would tend to vote Conservative - extended the franchise to all women over 21, with the Equal Franchise Act. Their prediction was correct: between 1945 and 1979, women were indeed significantly more likely to vote for the Conservatives - and had women not had the right to vote during that period, Labour would have remained in office for the entire duration.

Almost immediately after women were enfranchised, both the Conservative and Liberal parties were devising a wide range of policies designed to attract female voters, from the Sex Discrimination (Removal) Act of 1919 to the 1925 Widows and Orphans Act. It was also during this period that Nancy Astor - a Conservative - became the first female Member of Parliament to ake her seat in the House of Commons. She described how when she ‘stood up and asked questions affecting women and ‘ ‘ children, social and moral questions’, she would be ‘shouted at for 5 or 10 minutes at a time’, and viewed as a ‘freak, a voice crying in the ‘ss

wilderness’. Nonetheless, she held her seat for 26 years, during which time she continued to stand up for the rights of women and children. At the National Union conference in 1921, she moved a resolution that - given that Labour and the Liberals were working to recruit more female candidates for Parliament - ‘it is extremely desirable that the Unionist Association should not be behindhand in this respect’, arguing that more women in Parliament were needed to help her make the case for women’s rights. Although the motion passed, prejudice against female candidates inevitably endured: most of the first female MPs (including Lady Astor herself) took over seats vacated by their husbands — claiming legitimacy as political figures based on their roles as wives of former MPs. With Selection Committees and the electorate often deeply hostile to women, female entry into Parliament was a slow process; even by the 1980s, the proportion of female MPs was still only 3.9%.

As the number of women in Parliament continued to grow (albeit slowly), female MPs also began to take on frontbench roles in government. In 1951, Florence Horsburgh was appointed Minister of Education; in 1953, the role acquired the status of Cabinet minister, making her the first female Conservative Cabinet minister. The second such minister - holding the same post Baroness Horsburgh had occupied twenty or so years earlier - was Margaret Thatcher, who served as Education Secretary from 1970 until 1974. In 1975, of course, she became the first female leader of the Conservative Party, and in 1979, she became the first female prime minister of the UK. Despite her famous proclamation that she “owe[d] nothing to women’s lib”, and her reluctance to promote women to senior positions in government (of only eight female ministerial appointments, just one rose beyond junior level), she was indisputably a trailblazing female leader, defying convention to embrace a determined, unyielding public persona and leadership style. Her rise to power challenged gender norms and proved that women were capable of attaining the highest political office in the UK. ‘

After Thatcher, the 1990s saw a gradual increase in the number of women appointed to senior office - and with it, a degree of solidarity and mutual support. For example, Gillian Shephard and Virginia Bottomley were both appointed to John Major’s Cabinet in 1992; according to Shephard, knowing that the press were “looking for an excuse to write about Cabinet catfights”, the two promised privately that they “would never ever give anybody the chance to say that [they] were criticising [each] other”. However, support for the Conservatives was beginning to dwindle amongst female voters: the party’s share of the female vote stood at just 32% at the time of the 2005 general election. To combat this decline in women’s support, the new Conservative leader David Cameron unveiled plans to attract more female candidates, including panel selection rather than ‘testosterone-fuelled’ selection speeches, a (50% female) centralised shortlist of potential MPs, from which target seats were asked to select their candidates, and mentoring and training for female MPs. Another key initiative was the establishment of Women2Win, an organisation which - as attendees of the excellent Women’s Social in Michaelmas 2024 will be aware - supports female Conservative candidates running for Parliament. The following years saw an increased number of Conservative women in high political office: Theresa May became Home Secretary in 2010 and prime minister in 2016; Liz Truss became prime minister in 2022.

Today - while Labour have never elected a female party leader - the Conservatives have our fourth, after the election of Kemi Badenoch in November 2024. Though change has been gradual and there is still significant progress to be made, the history of women in the Conservative Party is filled with inspiring and impressive women who have made immense contributions to the country, party, and the cause of equality between the sexes.

By George Emms, Merton College

Committee Member

While not at the forefront of every voter’s mind compared to more pressing issues such as immigration, the NHS and the cost of living crisis, housing is nonetheless of great importance, especially for the younger generation. It seems that housing also offers a crucial opportunity for the Conservative Party to attract votes and instil a feeling of confidence and trust amongst first-time buyers. In the 2024 election, Rishi Sunak promised to build 320,000 homes per annum, however his failure to deliver on his previous promise of 300,000 houses annually meant that the electorate’s trust in him had already broken down. Labour have set the target of building 1.5 million new homes over the next five years; this translates to 16 local authorities being given new targets which are 400% more than what they have recently delivered. Is such a policy feasible and how can the Conservative Party best act in order to establish confidence among voters? This article examines the causes of this crisis, before outlining the possible paths that the Conservatives can take to solve this.

In West Lancashire - a Labour-run authority - annual housing targets have jumped from 166 new dwellings to 605 dwellings. Such a target is surely unattainable. A report issued by the Centre for Cities blames Britain’s estimated shortfall of 4.3 million homes on strict planning restrictions and calls for the government to introduce

zoning systems which automatically grant planning permission. An article written by the Confederation of British Industry cited that in 2022 planning delays slowed down the provision of an estimated 70,000 affordable homes. It is essential that in order to appeal to a broader voter base, planning restrictions must be eased to remove impediments for affordable housing. It is also essential that planning authorities are supported in an encouraging way. A survey of 108 local planning authorities indicated that 80% have reported a shortage of officers to address their workload. A clearer and more universal planning framework, which would facilitate a more automatic process, would remove obstacles which currently stand in the way of developers. A second cause of the crisis, which is arguably much more difficult to solve, is NIMBYism. Concerns about increased traffic, noise, congestion and a lower quality of life cause communities, often those in villages or small towns, to have a more defensive mindset. This presents an obvious paradox as the need to ease planning restrictions and incentivise developers is incompatible with individuals who are reluctant to encourage housing developments in their own communities; it is clear that a solution which promotes fewer planning restrictions must be coupled with a system which includes the voices of communities, even if this is challenging balance to strike.

How can home-building be incentivised? There is a persuasive case for the review of Green Belt policy. The Green Belt currently surrounds 15 urban areas and covers over 16,000km2 (which translates to about 12.6% of the UK’s land). A Carter Jonas investigation into the impact of Green Belt policy in York revealed that the city has not had a local plan in place for nearly 70 years. This extremity has led to a local revision of Green Belt boundaries, which will hopefully facilitate the construction of 7,000 homes. The Green Belt is thus evidently a restriction on UK land supply, and local authorities have recently had to introduce ‘leapfrog’ settlements outside the outer ring of Green Belt land. It is essential to note that ‘

environmental considerations should be taken into account. While, in the case study of York, a revision of Green Belt boundaries was a useful way of alleviating a local crisis, it may be a slow and arduous process to initiate a series of local revisions on a national scale, and this would not provide the swift effect currently necessary to relieve the crisis.

One solution, and a particularly conservative one too, would be to address the issue of vacant homes. At the moment, there are currently 676,000 vacant homes across the country. The prioritisation of brownfield development could have two significant effects. Firstly, this would avoid the risk of provoking environmental activists and NIMBYs and creating further aggravation of ‘ rural communities. Secondly, the relative ease and immediacy could inspire a greater sense of confidence among voters in an age where the electorate has increasingly fickle opinions, which require swift responses for demands to be satisfied. While I am not trying to generalise or simplify the task of turning these vacant properties into desirable dwellings, this task has the advantage of an added head-start, rather than building houses from scratch in accordance with the environmental complexities of development restrictions. Finally, the Conservatives must revive homeownership. One of the greatest problems is the ever-increasing affordability ratio of ‘

houses compared to earnings; currently the affordability ratio is a multiple of over eight. While average earnings have stagnated at £33,000 per annum, the average house price currently sits at £275,000. Through reverse-engineering the problem to make homeownership more accessible, an increased demand will incentivise developments. Rishi Sunak’s policy of lowering stamp duty was a great example of this and is also conducive to traditional conservative values of the homeownership: an element of the conservatism which Margaret Thatcher championed in the 1980s. Similarly, George Osborne’s introduction of the Help to Buy scheme, which made home-ownership more accessible with just 5% deposits, should be continued. To encourage housing development, homeownership must be made more accessible, so that development companies can have assurance in undertaking a wider range of house building projects.

To conclude, it is evident that the housing crisis cannot be fixed overnight. The complexities of planning restrictions, environmental considerations, NIMBYism, bureaucracy and an increasing affordability ratio are all contributing factors to the failure to meet various housing targets. Nonetheless, the revision of Green Belt policies, a focus on brownfield development and an encouragement of home ownership would all be conservative solutions to relieving the housing crisis and restoring confidence amongst the electorate in regards to housing. While very challenging to solve, the housing crisis should not be overlooked and could significantly contribute to the success of the Conservatives in the next general election

By Lydia Dicicco, St Catherine’s College

The Committee Member

Whilst visiting a friend at Somerville college last year, I stumbled across a small poster showcasing their eminent alumni. With the Margaret Thatcher Centre looming in the distance, I was surprised to see that the top spot was taken by the HR manager for Innocent Drinks. The one and only Iron Lady ranked a mere six out of ten. This is not to say that the HR manager hasn’t done very well for himself, but I was dismayed to see how little people seem to care ‘ about the first female British Prime Minister. 2025 marks 100 years since Margaret Thatcher was born, and 50 years since she became Conservative Party Leader. Let us reflect on her life, achievements, and impact that continues to be felt in British society today.

Margaret Hilda Roberts was born in Grantham, famously the daughter of a grocer. In 1943, she commenced her degree at Somerville College, Oxford, reading Chemistry. Whilst at the ‘

university, she would hold the position of President of the Oxford University Conservative Association for one term (already off to a great start!). She then went on to read for the bar and become a Barrister. After a few unsuccessful attempts to get into parliament, she was elected for the constituency of Finchley in north London in 1959. In 1971, early in her career as Education secretary, she earned the nickname of "Thatcher the milk snatcher" for taking away milk from school children. She then unexpectedly defeated Edward Heath in the 1975 Conservative Leadership Election, unfortunately not starting smoothly as Conservative Leader. However, the Winter of Discontent in 1978/79 led to a general feeling that “Labour isn’t working” (which the Conservatives would employ as a billboard election advert), and Thatcher’s victory over James Callaghan in the May 1979 general election.

After her victory, she famously quoted St Francis of Assisi: "where there is despair, let me bring hope...". Alas, her first few years in government delivered anything but! She instigated economic policies attempting to reduce inflation and help Britain out of the incoming recession, but things had to get worse before they could get better; there was mass unemployment in the early 1980s and riots in Brixton and Toxteth. This is when, UB40, a Birmingham pop group, (a “UB40” being the form to claim unemployment benefits) released a single: "I am the 1 in 10" which highlighted the despair of the 3 million unemployed. Thatcher could easily have been a one-term Prime Minister if it weren’t for what happened on the 2nd April 1982: the Argentine Junta invaded the Falklands Islands, a British Overseas Territory. She was determined to get the islands back and dispatched a taskforce to do just that. The British victory in the war vastly improved the government's ratings and so they were re-elected in June 1983.

Thatcher famously earned the title of the ‘Iron Lady’ for standing up to the Soviet Union. In partnership with President Reagan, she was ‘

instrumental in winning the Cold War for the West. She also stood firm against the militancy of the National Union of Miners, led by Arthur Scargill. This, and a booming economy in the mid 1980s led to a third General Election victory in 1987. Unfortunately, discontent with her somewhat abrasive style, and the introduction of the Poll Tax in 1990, led to her being replaced as leader by John Major.

So, what can we conclude about Thatcher’s legacy?

Early in Hilary term, the Conservative Environment Network held a talk for OUCA, in which they showed us a video of Thatcher in 1989, pleading with the United Nations to do something about climate change. Even then, she was more than aware of the threat of overpopulation and pollution, explaining that the threat of “more and more people and their activities”, would lead to more intensive cultivation of land, the cutting down of forests, and the polluting of seas and rivers with the burning of fossil fuels. She even called for a “framework convention on climate change, a sort of good conduct guide for all nations”. Perhaps if people had taken more heed to her words, our climate problem would be less severe than it is today. It is also interesting to think about how different the opinion of Somerville College goers would be if they knew this fact about her. Perhaps she would even have made the top five!

It is certainly true that not all of the decisions Thatcher made that still affect us today have been successful. Thatcher tried to help home ownership with her “Right to Buy” scheme, allowing those living in social housing to buy the house after living there for a certain amount of time. Of course, this had the unintended consequence of a shortage of council houses and flats, which has truly become a problem with the increasing number of people in need. It could be argued, however, that this was not the fault of the scheme itself, which provided home ownership for many people who would have struggled to achieve it otherwise. Instead, fault could be attributed to ‘

local authorities and the government of the day for not reinvesting the proceeds from the sale into new social housing.

Truly, her most notable legacy is the political division still felt in the UK today. Described as a “marmite” figure, there is a polarisation of thought surrounding Thatcher and her policies. There is some feeling of regional and class divides which still persist, especially in attitudes towards government intervention and economic policy. Her noble emphasis on the individual unfortunately had unintended consequences, by creating an “us and them” attitude in politics. Her famously saying “There is no such thing as a society” was used by her opponents to accuse her of creating a selfish “I’m alright Jack” society. It seems to me that this is not a fair assumption, as from her own humble beginnings, Thatcher wanted to provide opportunity for all. In future years, history might take a more positive view of her legacy, in trying to improve the country that she most obviously loved. Personally, despite not being alive during her premiership, I still appreciate how she tried to rescue Britain from the economic basketcase it had become under the Labour governments of the 1970s. I hope that one day my friends at Somerville might also appreciate this.

By Harriet Dolby, Lady Margaret Hall

The Committee Member

Student politics attracts and cultivates a particular breed of people. Ambition, determination and wit are three key components of a successful ‘hack’, the much-loathed sub-section of university students. Student political societies such as OUCA offer training grounds for future politicians - testing their public speaking abilities and teaching people how to win votes and hopefully keep them. Yet these shadowy groups provide something even more important: free speech. As the Oxford Union likes to remind us, they are celebrating over 200 years of free speech, acting as an opportunity for debate and discussion on controversial and divisive topics. However, OUCA is the true bastion of free speech, hosting the weekly ‘Port and Policy’ which enables drunken speeches to be confidently made without the fear of being filmed or recorded. OUCA and the Union alike though are the academies from which many famous politicians have emerged - with this article exploring the origin stories of Jacob ReesMogg, William Hague and Boris Johnson.

To start off, we have our Honorary President, Jacob Rees-Mogg, who is emblematic of the traditional old-money Tory. Today he espouses ‘

his further-right views, such as controversially claiming that abortion should not be legal in any circumstances, and that the green-energy movement is a threat to the UK. Yet this philosophy had also been present in his university days, with his presidency of OUCA marked by his clear commitment to traditional conservative values. These opinions, however, originated from his academic life, found when studying History at Trinity college, by reading the works of figures like Edmund Burke, whose ideas on tradition and social order resonated deeply with Rees-Mogg throughout his career. Emblematically British, Rees-Mogg’s leadership style was distinguished by his intellectualism and his ability to articulate conservative ideas in a way that appealed to a broad range of OUCA members, and indeed the Conservative party. Such eloquence in raising his views were fostered in the Oxford Union too, with his speeches in debates being marked by his formal deliberate manner, a trait which we still witness on GB news or indeed not too long ago in the House of Commons.

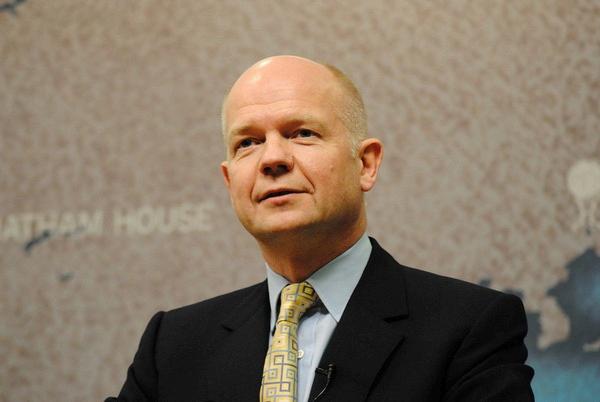

Another individual also still relevant to our university, William Hague, was a fellow OUCA president just 10 years before Jacob Rees-Mogg. Whilst they may share conservative principles and the same former position, Hague’s background was vastly different from Rees-Mogg’s. Indeed, Hague came from a working-class background in Yorkshire, with OUCA enabling him to break into the upper echelons of British politics. Through raising the prestige of OUCA, Hague gained much respect within the Conservatives, making a name for ‘

himself as a rising star in the Party. Not long afterwards, in 1989, he became the MP for Richmond at the age of just 28.

Clearly his rapid rise within the Party was a direct result of his leadership in Oxford’s political circles. Philosophically though, Hague was also shaped by his academic studies, reading PPE. Through this classic politician’s course, he developed a strong grounding in his conservative ideology and economic theory. This conservative ideology was rooted in a belief in individual liberty, free-market capitalism and limited government - principles that would later define his political stances as both party leader and shadow foreign secretary. These views unsurprisingly led him to be a strong advocate for Thatcherism during his time at Oxford, and Hague remains a strong advocate for conservative principles to this day.

Lastly, the always effervescent and bumbling Boris Johnson was an infamously significant player in the Oxford student political scene. Known, as he is today, for his flamboyant style and witty sense of humour, Johnson was an incredibly effective hack - maybe we should learn from him. It was in the Oxford Union in which he created for himself a legacy of unseriousness - further worsened through his membership of the Bullingdon Club. He became first Secretary and then President of the society. Oxford, for Boris, was an excellent opportunity to meet other ambitious, dynamic students, who would later be his political accomplices or rivals. This network of fellow Conservatives included most notably David Cameron and Michael Gove, proving how the people we meet here could prove useful in a few years time. I wonder who you’re thinking of?

OUCA and the Oxford Union have proved themselves to be the training camps for politicians: providing opportunities for espousing controversial, or rather ‘honest’ views. These societies have not been without their controversies, yet clearly those who we meet here are the leaders of tomorrow. Student political societies have shifted ‘

though; the political landscape has changed. Whilst OUCA may not have been always popular, it feels as if our university reputation is unfairly poor, especially if you are outside the Tory triangle of Christ Church, Corpus Christi and Oriel, as I have faced at Lady Margaret Hall. The woke rhetoric is at an all-time high, with many jumping on the bandwagon of left-libertarian movements for fear of being cancelled themselves. That is why organisations like OUCA are so important. We facilitate a broad range of people across the political spectrum, from Charles Amos to the Labour Club ‘imposters’, who we of course love to see at P&P. While there has long been a diversity in political views, it is encouraging to see so many more women being involved in the association, refuting the accusations of OUCA being a male association. OUCA is clearly the start of the path to success for many politicians, teaching them the lessons of back-stabbing and PR from an early age. As OUCA is the future, to quote Michael Gove, ‘We can shape our destiny. It is in our hands to save the nation’.

If you enjoyed reading this edition of Blueprint, consider having a look at the blog on our website, where articles are posted to regularly.

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/0/0a/Official portrai t_of_Laura_Trott_MP.jpg

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/7f/Friedrich_Hayek portrait.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:William Hague, UK Foreign Secretary_%285574078073%29.jpg

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/1e/Clement_Attlee.j pg https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/3/37/Winston_Churc hill.jpg https://timelessmoon.getarchive.net/amp/media/nancy-astorviscountess-astor-a7bd55

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/20/The_Metropolit an_Green_Belt_among_the_green_belts_of_England.svg

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/3/32/Margaret_That cher 01 %28cropped%29.jpg

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/8c/Official portrait _of_Mr_Jacob_Rees-Mogg.jpg

All images obtained under creative commons licensing.