“

Philosophy is a tool that essential to finding truth, and nothing but the truth ”

Welcome to the 3rd edition of the Philosophy Society’s Seasonal Issue. We must recognize how impactful discussions have been since our first release It is inevitable that one critically analyses whatever they read Who wrote it, and what may have been the reason for writing?

We are in search for new and interested in thinking members Be part of discussing your thoughts They are invaluable

Send an e-mail to:

o ibragimov@cdl ch

Today, we ask ourselves a question about the reasonability of justice Are justice systems as fair as we envisage them to be? Many conspiracy theories may distort our understanding, and hence the manipulative function of this belief will drive us away from the objective reality Justice is truly an elastic term with various definitions that aren’t necessarily the same. Nevertheless, this edition focused on addressing the complex nature of justice with an example of such a process.

In this edition, you may encounter interpretations of historical events that have a multifaceted approach to raise more questions and, at last, come up with reasonable conclusions These conclusions incorporate works of prominent philosophers and not only are they put into context, but also criticised to a certain extent in order not to distance ourselves from the line of realism

We very much thank you for taking the time to read and follow our seasonal issues. We value the feedback and the diversity of perspectives Most importantly, we hope you find something relevant to your area of expertise and maybe this way equip the essential tool of philosophy.

In today's society, it's easy to point fingers and assign blame when things don't go according to plan. However, ‘blame’ is a very broad term which’s diversity is manifest. The foundation for portraits of blame is our imagination. In philosophy, there is no strict definition of this phenomenon, as it revolves around basic features of human morals, beliefs, and needs. Mainly, that may be the case for ‘accusative blame’, in which it may simply be: that blame is the belief that someone is to be punished for an act that is against your/one’s interest.

In the realm of culinary adventures, recipes often adhere to familiar ingredients and traditional methods passed down through generations. Yet, there are moments of delightful deviation when chefs dare to experiment with unconventional combinations and unexpected twists Similarly, in the realm of literature, while many novels may centre around common themes like love, loss, or coming-of-age, there are instances where authors diverge from the norm and explore unique narratives and unconventional subject matters Take, for example, a novel that doesn't revolve around typical human experiences but instead delves into the inner workings of an ant colony, exploring the complexities of insect society and the struggles of its inhabitants to survive in a hostile world. While such a narrative may seem unconventional, it offers a fresh perspective on the intricacies of life and the universal themes of struggle, cooperation, and survival

Similarly, just as a chef might incorporate unexpected ingredients like chocolate and chilli peppers into a savoury dish, a novelist might blend elements of science fiction and fantasy into a historical drama, creating a rich tapestry of genres that challenges readers' expectations and expands the boundaries of storytelling. And that’s how Michelin stars are born...

The proposed paradigm of blame presented in this case is “Blame,” which may be simply defined as the act of expressing fault or wrongdoing in direct and immediate interpersonal interaction. In this form of blame, when one person wrongs another, the aggrieved one communicates their sense of fault to the accused one.

Blame doesn't necessarily have to be verbal; it can also be conveyed through gestures or behavioural cues For instance, the guilty person might pointedly fall silent or leave the room in response to the perceived wrongdoing But is silence a key to working on problems? Personally, I hate it What distinguishes blame from other emotional responses to an error, such as hurt or sorrow, is that it explicitly accuses the ‘guilty’ of fault This fault can pertain to actions, omissions, motives, attitudes, dispositions, or beliefs, even if those inner aspects aren't explicitly manifested in behaviour

The spectrum of moral fault that can be addressed through blame is broad and includes various dimensions of human behaviour For example, in the context of racism, individuals can be blamed not only for their discriminatory actions but also for the underlying beliefs or motivations driving those actions

To illustrate, consider the scenario where you return home from a weekend trip to find that your neighbours failed to fulfil their promise to walk your dog while you were away In response, you may communicate blame to them, either explicitly or implicitly. This blame could take various forms, ranging from a straightforward accusation to a more subtle expression of disappointment or disapproval. Blame serves as a means for individuals to hold others accountable for their actions or omissions, addressing not only the external behaviour but also the underlying moral dimensions of fault. Through this form of interpersonal communication, individuals seek to uphold moral standards and maintain accountability within social relationships.

Nietzsche, a trailblazing German philosopher of the 19th century, was a staunch advocate for individualism and self-mastery. Central to his philosophy was the idea that true liberation comes from embracing personal responsibility and taking ownership of one's life In his view, blaming external factors or other people for our failures is an act of self-deception that robs us of power

At the core of Nietzsche's argument is the notion that our destinies are largely shaped by our own actions and decisions By relinquishing responsibility and attributing our shortcomings to external forces, we relinquish control over our lives and surrender to a sense of victimhood. However, Nietzsche challenges us to break free from this mindset and instead embrace the challenges and adversities that come our way as opportunities for growth and self-discovery. This guides us in the case of the dog example, where understanding of ‘blame’ from Nietzsche’s perspective is part of societal ‘power’ implications. It’s a system of imposing guilt and the means of accountability, which therefore restricts the reflexivity process, in which we are able to learn, develop, and differentiate between ‘good’ and ‘bad’. As simple as it may seem, ‘blame’ is for the weak. The idea of blame directly contradicts Nietzsche's ambition for self-development. Especially with his famous quote “death of God”, he exemplifies how religion may also be part of a development barrier For the two examples, you may visualize a painting with two

plaques: (1) “Death of God – Nietzsche”, and (2) “Death of Nietzsche – God”. Ultimately, this is a painting that raises the significance and nature of belief. Even today, some ideas of Nietzsche are regarded as controversial and complex, whereas his goal was to move people to accept what they know and what they don’t It may appear easier to blame someone for one’s mistakes and miscalculations, however, it moves us away from objective reality Moreover, Nietzsche believed that adversity is an essential part of the human experience and that it is through facing challenges head-on that we develop resilience and strength of character Rather than wallowing in bitterness or resentment, Nietzsche encourages us to confront our struggles with courage and determination, viewing them as stepping stones on the path to self-actualization.

By adopting Nietzsche's philosophy of personal responsibility, we empower ourselves to transcend the limitations of blame and victimhood. Instead of dwelling on what went wrong or who is at fault, we focus our energy on learning from our experiences and striving towards our goals. In doing so, we reclaim agency over our lives and pave the way for genuine growth and success. Nietzsche's perspective on personal responsibility offers invaluable insights into how we can unlock our full potential as individuals. By rejecting the blame game and embracing responsibility for our actions, we not only empower ourselves to overcome obstacles but also work on aspects necessary to thrive in an ever-changing world Ultimately, it is through embracing personal responsibility that we embark on a journey towards self-discovery, fulfilment, and true development Therefore, we should always reflect on our own ‘blame’

As an essential part of philosophy, we must highlight how subjective the ‘blame’ may be The subjective part may be the very reason for the persistence of hypocrisy. Sometimes, when we point fingers at others, we intend to help them recognize their mistakes and encourage them to change their behaviour for our understanding of ‘better’. However, this approach can backfire if we are guilty of the same or similar wrongdoing. The person who blames others while ignoring their own faults is often seen as hypocritical, which undermines the effectiveness of their criticism. This is not just about whether the blame achieves its intended purpose; even if it did, the problem runs deeper. Imagine getting feedback from an English teacher with a nice collection of grammatical mistakes. How reliable do you see it?

Any path of ‘blame’ remains open Whether it’s demand, accusation, accountability, or punishment, it directly refers to the morals which I am afraid alarmingly indicate ‘hypocrisy”

In

As we know, law enforcement is flawed This is not a phrase of a disappointed person, but one of the main problems of mankind, which it has been trying to solve for centuries

Law enforcement was created to deliver justice, but no country in the world can still say that it always manages to deliver justice to its citizens. American journalist Jesse Signal in 2021 analyzed the reasons for the increase in the U.S. homicide rate in 2020. Besides the obvious problems caused by the pandemic, he cited people's dissatisfaction with how justice is delivered as the root cause: " they want their fair share of resources, including police resources, but they want the police to treat them with the dignity, fairness and respect they deserve " The philosophical treatment of this issue shows that this increasing contradiction in social relations related to the realization of the principle of justice does not happen by chance, it is due to deep and different reasons

The point is that no sufficiently reliable mechanism for ensuring fairness has been constructed so far. Therefore, in this article, we set out to examine the foundations of fairness and to find out whether a principled solution to this problem is possible. In addition, we are also interested in the trends that exist in this field. Of course, we will not be talking about specific solutions of particular law enforcement agencies. The philosophical nature of this exploration requires us to consider the most general aspects of this problem. Nevertheless, it is important for every particular person who has encountered the law enforcement system to know to what extent it provides the principles of justice, in other words, to what extent he or she is protected from arbitrariness At the philosophical level, this problem can be formulated as the problem of the foundations of justice and their practical effectiveness

Now justice, according to the majority, is "a secondary normative idea, an idea that can be applied even in cases of serious immorality" Justice devoid of moral content is a frightening thing, so they try to fill it with political, ideological, sociological or psychological content, something not naturally objective either But all these attempts fail to produce a reliable result. The problem of providing justice with solid foundations remains unsolved. This leads to the unclear basis of legal 'norms'.

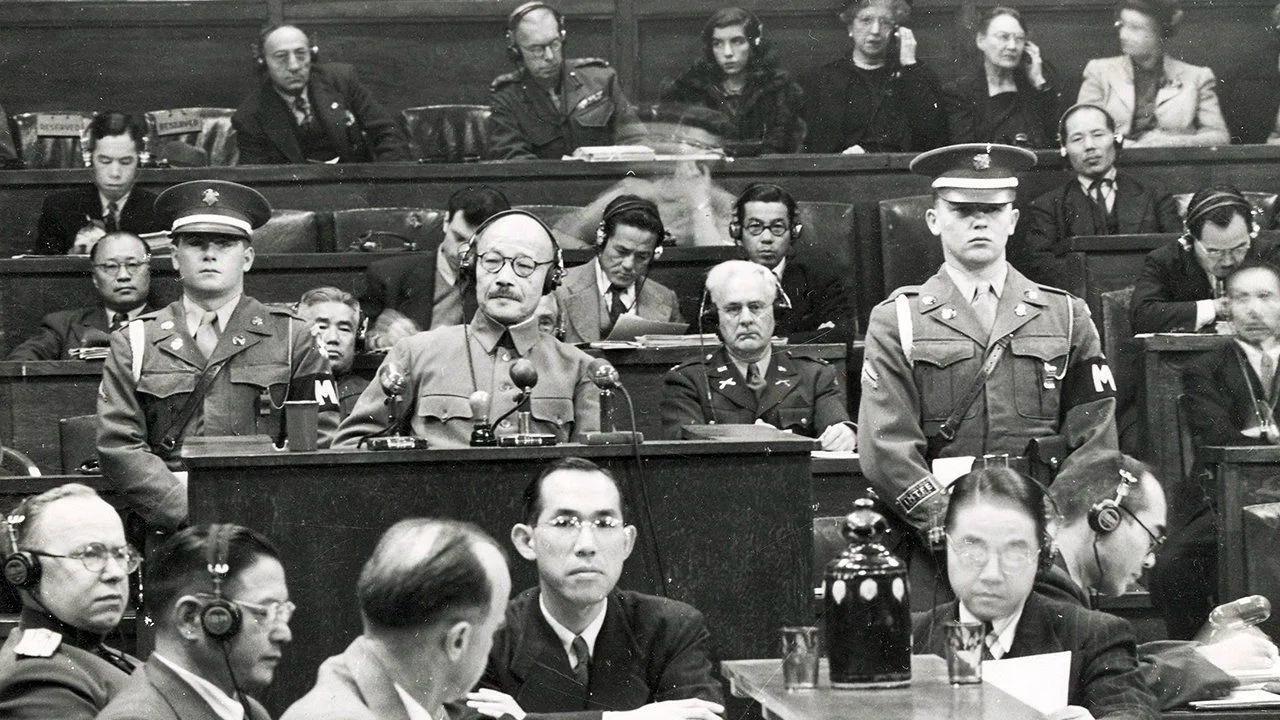

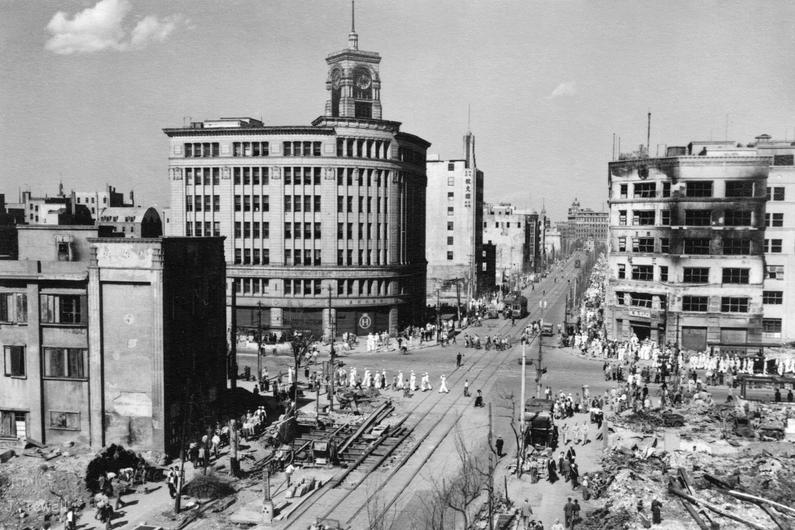

From known examples, we can cite the Tokyo case as an example. The trial by the International Military Tribunal of Japanese war criminals after the Japanese surrender act in 1945 is one of the most striking examples of the 'elasticity' of the law. Many other circumstances made the work of the prosecution on the American side very difficult. How could the Japanese be accused of the inhumane bombing of Pearl Harbor when outside the courtroom windows lay Tokyo, which was 93 percent erased to the ground by the American air force, and to the south of it the Hiroshima and Nagasaki, where a quarter of a million civilians were incinerated in the blink of an eye? How can the Japanese be accused of inhuman treatment of prisoners, when in the U S itself 120,000 innocent citizens were repressed and subjected to extremely cruel treatment, just because they were of Japanese descent? There were many such questions: on the rules of warfare, and mutual violations of its norms.

Despite various disagreements and protests from the Japanese Cabinet, the tribunal took place. It is here that two different approaches to the 'just' method of reasoning can be identified. One is the 'spiritual' approach, which defines the essence of law and becomes a tool for realizing justice in cases where the foundation of the case itself is unclear. The second is the 'formal' approach, which expresses the term 'justice' by a set of rules.

Thus, the accused were tried, including for crimes that were not qualified at the time of their commission, i e based on the non-legal principle of "ex post facto" The prosecution was based on the concept of "conspiracy", borrowed from Anglo-Saxon law and not recognized internationally at that time But the tilt towards the prosecution was certainly present, especially when the tribunal consisted of judges representing the victorious countries Despite such a politicized process, it should be noted that the importance of the verdict of the accused not only focused on Japan's war crimes but also on recognizing the morality of their actions in China or any other Eastern Asian country.

The philosophical reasoning of the Tokyo Process is not aimed at achieving a finding of innocence on one side On the contrary, it objectively examines the systematics of decision-making and the identity of the very institution that is engaged in the 'process'. It is impossible not to recognize Japan's counter-accusations as irrelevant; they certainly helped to mitigate the charges and achieved the imprisonment of the eighteen defendants. But when considering the cultures and backgrounds of the tribunal members themselves, it is impossible not to say that a political motive may have dominated the process, especially in the aftermath of grievous historical events.

Indeed, the use of the two methods of understanding the foundations of justice discussed above can occur not only at the societal level but also at the personal level. At the level of a person's social life, there are always too many factors that seek to impose certain patterns of behaviour and decision-making The emergence of these patterns is usually due to political reasons, and changes in the political situation cause changes in the patterns of behaviour These patterns cannot serve as a basis for justice because they represent a distorted perception of reality

But philosophy has shown that the constructive variant of solving the problem lies in the activity of man as a being both material and spiritual. Only man himself can find a balance between the norms of law and the morality of actions. This conclusion is used independently of the criticism of 'subjectivity' and 'difference' in interpretations of the law.

philosophy reflects a commitment

values of human dignity, equality solidarity, and advancing the global agenda for sustainable development and peacebuilding.

The understanding of law is a very complex process. Using an encyclopaedia to define this term may appear challenging. A lawyer may have a definition of their own, but it’s not universal and is mostly dependent on morality or its absence This case may be similar to Hammurabi’s code of law, which involved definitions of crimes and punishments that follow It was mostly a prediction of law: “Doing certain crimes will have certain consequences” However uncertain that sounds

No matter how the ‘adoption’ of laws passed by the legislature proceeds, we can only assume that the enforcement of those laws is specific. Not really, no. Laws are broad and are always subject to interpretation. The problem is that the interpretation is dependent on the perspectives of the person in charge of a legal process. Are those people (let’s call them justices) programmed to skim through the huge archive of laws and therefore make their decisions ‘just’? Certain laws may appear in books and official documents, but they never have the nature of being constantly referred to. Simply: laws may be written, but it’s not guaranteed to be enforced in any of the life situations. Does that mean that the text defining the law is still a ‘law’?

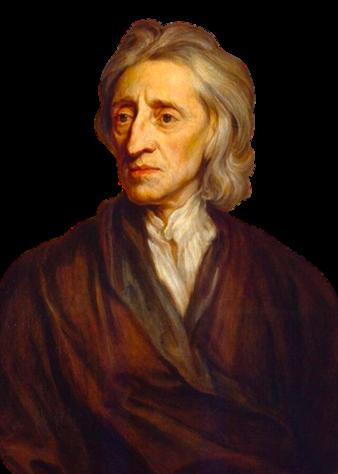

As one of the most influential English philosophers, John Locke defined: right as the fundamental moral fact, rather than any duty individuals have to a law or to each other So the morality of a fact will entirely depend on one’s beliefs and perspectives Laws are elastic and are bespoke, but they set the frames for the complex nature of justice in a society that is built on “war of all against all”, which indicates people’s self-interest and motivation to unite when aware of an enemy’s presence However abstract, the enemy appears.

“ There is a moral law that is (1) discoverable by the combined work of reason and sense experience, and (2) binding on human beings in virtue of being decreed by God. ”

Emperor Hammurabi – Babylon by Getty Images

Emperor Hammurabi – Babylon by Getty Images

This of course raises an important question that affects the justice system as a whole, and people that are ought to obey the law If morality was to navigate the legal process, then who would navigate morality? To avoid overly optimistic conclusions about people’s rationality and how righteous their morals are Creating a body responsible for using the ‘dry’ law principle with morals impacting its interpretations is rather risky

Take Rosa Parks as an example, who was back then not allowed to sit at the front of the bus just because she was a woman of colour. She sat in the front, knowing that it was illegal. Her decision was an act of protest, as she considered laws that set frames to behavioural traits or natural rights of people of colour, something ridiculous. She was arrested for such an act of protest, but was it morally right?

Hobbes would argue that she was taking part in civil disobedience. This strictly means that she was causing chaos by going against the system with a solid judicial foundation, however unfair it may seem to modern global citizens. Yes, it may have caused further mass protests, which potentially would increase the harm done to the African American community But maybe Hobbes assumed that the judicial system is run by people who are ‘rational’ Maybe he was overly optimistic about laws and bodies that enforce and create laws

With results from the Tokyo Process, we may only see the pattern of how morality navigated the tribunal past the official and legal set of defined laws back in the time when the Japanese were committing ‘war crimes’ But it however shouldn’t constitute ‘unaccountable’ which was the case

Dead Souls

Nikolai Gogol

Available in the library

Oscar Wilde

Not available in the library

John Locke

Not available in the library