Particular Social Groups (PSGs)

ELEMENTS

SEXUAL ORIENTATION

DOMESTIC VIOLENCE

FAMILY

• Immutable: cannot or should not be expected to change

• Particularity: defined and specific

• Socially distinct : recognized by society

• Targeted based on sexual orientation; look for threats or violence related to sexual orientation or appearance

– Immutable: cannot or should not be expected to change sexual orientation

– Particular : clear delineation of who is in LGBTQ+ group and who is not

– Socially Distinct : recognized by local community as distinct group

• Subjected to extreme control and violence by partner that escalates with resistance; treated as property of partner and partner will not allow woman to leave relationship

– Immutable: woman cannot change relationship status (i.e. cannot leave)

– Particular : defined terms (married/partnered + woman + unable to leave)

– Socially Distinct : social norms/culture of machismo create distinct group

• Targeted, often by gangs, based on familial relationship; typically results from gangs seeking leverage or revenge related to another family member

– Immutable: cannot change family relationship

– Particular : clear delineation of who is in family and who is not

– Socially Distinct : family is known/recognized within local community

• Targeted, often by gangs, based on former profession, skills, or knowledge (i.e. police, military, nurse, etc.)

– S ocially Distinct : group is visible within society FORMER POLICE (OR OTHER PROFESSION)

– I mmutable: cannot change former profession or the skills or knowledge learned in that profession – Particular : clearly defined group

WITNESS TO CRIME

OTHER

COGNIZABLE

• Targeted, often by gangs, for public cooperation with law enforcement in prosecution or investigation of criminal activity

– Immutable: cannot change status as witness

– Particular : witness is identifiable; must be some aspect of public participation – usually providing public testimony – in prosecution or investigation

– Socially Distinct : must show that witnesses are seen as distinct; existence of witness protection program or similar policies can demonstrate this

• This chart is not an exhaustive list.

–O ther potential PSGs may include, but are not limited to, people with disabilities, landowners, and ‘gang girlfriends.’

• G eneralized gang violence or criminal activity

• Intra-family violence or incest; interpersonal disputes

Past Persecution

Asylum/Withholding of Removal

• Are you afraid to return home?

• When did you leave your home country? Why did you leave on that date?

• Who caused you to consider leaving your home country?

• When did he/they start threatening/assaulting you?

• Threatened in your home country?

o With bodily harm?

o With death?

o With death of relative or loved one if you did not act or stop acting in a particular manner?

o To pay money?

• Were the threats for you to pay or for someone else in your family to pay?

• If threats to someone else to pay, were you threatened to make another family member pay?

• Refuse to pay? What happened then?

• Assaulted? Detail assaults.

o Verbally? What were the specific things the person (people) said?

o Physically? Seek medical attention? Are there records of your treatment? Do you have scars?

o Sexually? Seek medical attention? Are there records of your treatment? Did you become pregnant as a result?

• Detail threats/assaults, including content, timing, to whom, by whom (including whether they were a gang member, part of a colectivo, or a State Actor).

On Account Of/Nexus

• Why were you targeted for these threats/assaults? Detail language of threats and used during assaults to illuminate whether threats/assaults were “on account of” a protected ground.

o Was it based on your political opinions? Unwillingness to express a pro-State opinion? Because of your family’s political opinions?

• What were your political opinions? Expressed? When? Did the State take notice?

o Your sexual orientation?

o Membership in your family? What was it about your family that caused it to be targeted?

o Husband or partner viewed you as property? Did he exert extreme control over you? Does your family/community condone such treatment?

o Was it because you went to the police? Testified?

o Was it because you or someone in your family refused to join a gang? Or refused to be a gang member’s “girlfriend”? Refused to follow gang’s rules?

o Your race? Your nationality? Your religion? Your gender?

• How do you know (did they say it to you specifically)? Why do you believe so?

By State or By Entity State Is Unwilling/Unable to Control

• If by State (or State Actor), other State Actors or Departments who could control? Why not?

o Knowledge of State threats/assaults of others similarly situated to you? What happened to them?

o For Venezuelan colectivos, which one? How do you know?

• If non-State Entity, report threats or assaults report to the police?

o If yes, when? What did the police do or say with respect to the report? Did they investigate?

o If no, why not? Need anecdotal support showing State does not control in similar circumstances.

• For example: Had police refused to act previously? Do you know someone who reported and was then threatened/assaulted further because the report was made known?; Were you aware that the police did not do anything in response to the reports? (How do you know?); Do you know that the gangs had infiltrated or control the police? (How do you know?).

Internal Relocation

• Is there any other place in the country where you could move? Do you have family elsewhere?

o Would you be safe from the current threats/assaults? New dangers there?

o Any other reason you could not move?

• Did you move any time after the first threat/assault?

o Where, with whom, for how long?

o Were you safe? Could you be safe if you returned?

Future Persecution

• What do you believe will happen to you if you do return to your home country?

• Since you fled, has the person or group continued to look for you?

• Continued to make threats against you? Watched your house, or threatened your friends/family if they do not reveal your whereabouts? How do you know?

• Provide details of any ongoing threats. Corroboration

• Do you have any evidence of the threats?

o Notes, texts, voice messages, Facebook messages?

o Evidence of assaults? Contemporaneous pictures? Scars? Medical records?

o Police reports? Newspaper stories? Social media?

• Witnesses to the threats or assaults? Similarly threatened or assaulted? Whom you confided in contemporaneously?

Convention Against Torture

• Would you be tortured if you returned to your home country?

o Why do you believe you would? Tortured previously? Threats of torture made to you?

• By the State, including the police or military? Others tortured in similar circumstances?

• Or with State acquiescence?

o By whom? MS-13 or Barrio 18 in the Northern Triangle, Sandinistas (or Danielistas) in Nicaragua, Colectivos in Venezuela, the CDR (Committees for the Defense of the Revolution) in Cuba?

o How do you know the State would acquiesce? Provide details.

Evaluating a Claim for Relief under the Convention Against Torture (“CAT”)

Applicants for CAT relief must prove two elements: (1) they will likely suffer torture; and (2) such torture will be inflicted by or with the acquiescence of a public official (or other person acting in an official capacity). The questions below will help you identify which facts, if any, may help a migrant articulate a cognizable CAT claim.

• This is not an exhaustive list. Further follow-up questions are likely needed. Asking “how do you know?” can be helpful, especially after eliciting a salient fact.

• This is not a script. Rephrase, simplify, and deviate as needed.

State Actor: Was the person who harmed you a public official or a person acting in an official capacity?

• Determine whether the person who harmed the migrant was a public official.

o Did the person who harmed you work for the government, military, and/or police? If yes:

What is their title/rank?

What power do they have locally, regionally, and/or nationally?

What resources do they have access to?

How many subordinates do they command?

• Determine whether the person who harmed the migrant was acting under the color of law and/or in an official capacity when they harmed the migrant

o Did the person who harmed you mention their profession or position? When?

o Did they threaten to use the power of their position?

o Were they wearing a uniform when they harmed you?

Did the uniform have any writing/symbol/insignia?

o Did they have a badge?

o Did they drive a state vehicle?

Did the vehicle have any writing/symbol/insignia?

o Did they use state weapons and/or equipment?

o Did they use language common to their work?

“You are under arrest;” “I am detaining you;” etc.

o Were there others present?

Were they similarly identifiable?

• If not, what differentiated them?

Did they participate in the persecution?

Was there an apparent command hierarchy?

Did any of them order/command the others?

Did any of them receive commands or indicate as such?

• If the person who harmed the migrant was not a public official, explore whether they are a member of a paramilitary or organization paid/hired by the state such that they may be considered a state actor. Such groups work directly or indirectly for the government (though they can also work counter to the government) and can control regions as a quasi-state or state-sanctioned actors See Country Conditions tab for examples of paramilitary organizations

State Acquiescence: Did the public official or other person acting in an official capacity instigate, consent to, or acquiesce to the torture?

• Were government/military/police present during the persecution?

• Did any government/military/police assist the person who harmed you?

o Do the people who harmed you have ties to government, military, and/or police?

Friends/family in the government, military, and/or police?

Have you ever seen them with government/military/police?

o Did the person who harmed you influence or pay off the government/military/police?

o What is the profession of the person who harmed you?

Does their position relate to government/military/police?

Do they interact with government/military/police?

Is it a position of power, wealth, or influence?

• Did the police or any government or military officials know about the persecution?

o If so, did they do anything to try to prevent it? [willful blindness standard]

o Did they do anything to stop it from happening again?

• Did you report to the police or other authorities?

o If so, what was their reaction?

o Did they contact the person who harmed you?

o Did they take a report? Allow you to read it or give you a copy?

o Did they take any further action (protective order/arrests/other follow-up)?

Evaluating Domestic Violence Claims

Applicants for asylum or withholding of removal (“WOR”) must prove that a protected ground was at least one central reason they were or will be harmed. Many courts recognize a particular social group (“PSG”) for women who suffered domestic violence (“DV”). In proving a claim relying on a PSG of DV, courts typically require proof that a woman suffered sustained violence by a partner or spouse, that she could not leave the relationship, and that the violence was at least somewhat normalized by the local community. Remember to also explore whether any other protected grounds could be one central reason for the abuse. For example, consider whether a political opinion claim exists where the woman believed in gender equality and was harmed on account of that belief. In addition, particularly where the abuser was a government official, consider whether a CAT claim may be cognizable.

The questions below will help you identify facts that may support a claim for relief in a DV case.

• This is not an exhaustive list. Ask follow-up questions as needed.

• This is not a script. Rephrase, simplify, and deviate as needed.

I. ASYLUM/WOR: PSG CLAIM

Did the woman experience severe and sustained DV by a spouse or partner?

• Identify facts showing that the abuse occurred at the hands of spouse or partner.

o Were you married to your abuser?

If not, determine if in established partnership or common law marriage.

o Was your partner violent or threatening? How?

When did the abuse begin? How often did it occur?

• If abuse seems tied to alcohol or drug use, explore whether it also occurred while the abuser was sober or for other reasons.

Did the violence result in any injuries or medical treatment?

Did he harm or threaten others, such as your family or kids?

Could the woman change the relationship status (i.e. leave the relationship)?

• Determine whether the woman was able to leave the relationship and why or why not.

o Were you able to leave the relationship? If not, why?

o Did you ever successfully leave your partner (excluding traveling to the U.S.)? What happened?

• Determine what degree of control the partner had over the woman

o Did your partner prevent you from leaving the house or going to any place?

If so, explore. Where? Why? How?

o Did your partner control other aspects of your life? How?

Explore all aspects of her life that he controlled, such as dress, phone, relationships with friends/family, finances, reproductive decisions, etc.

o Did he force you to do anything against your will?

Did he force you to be physically intimate against your will? How often?

o Did you ever resist any of the ways he controlled you? What happened?

Did anyone refuse to assist the woman and/or did her community normalize the abuse?

• Determine whether and how the local community normalized the abuse.

o Did you seek help from local authorities or others?

If yes, what was the response?

If no, why not?

o Do you know of other women in similar situations? Did anyone assist them?

o Did the abuse escalate after you sought help in any of the above ways?

II. ASYLUM/WOR: OTHER POTENTIAL CLAIMS (POLITICAL – GENDER EQUALITY)

Explore whether the woman’s race, national origin, religion, or political opinion could be one central reason for the abuse she suffered. The questions below address political opinion claims based on a belief in gender equality. 1

Did the woman’s belief in gender equality constitute one central reason for the abuse?

• Do you believe that men and women are equal? For example, do you believe that women should have all the same rights and opportunities as men?

o Did you ever express that belief to your partner or others? How?

o If so, how did they respond?

• Did your partner believe that men and women are equal?

o If not, how do you know?

o Did he ever say anything how women aren’t as good as men or about how men should be in charge?

Did you ever disagree with him or oppose him when he did so? How did he respond?

Did your partner make these or similar statements when abusing you?

• Did you partner try to keep you from exercising rights or accessing opportunities? Refer back to questions about control. Explore whether you can link partner’s violence to her efforts to resist control and assert equality.

III. CAT CLAIM

In addition to the standard CAT questions about government acquiescence or abuse, explore the following.

• Did your partner work for the government (police, military, hold political office, etc.)?

o If so, were any of his coworkers aware of or involved in the abuse?

o Did he ever use his position in the government to harm you?

For example, if he was a police officer, did he threaten to have her family arrested or use his state-issued weapon to harm her? See the resource binder tab on evaluating a CAT claim for additional guidance.

1 In DV cases, the most common type of political opinion claim is one based on the woman’s belief in gender equality. But political opinion claims are not constrained to that particular political opinion. For example, although rare and subject to unsettled law, a political opinion claim may also exist if the woman was abused because of her refusal to undergo an abortion and that abuse terminated the pregnancy.

Immigration Law Terminology & Acronyms

Adjustment of Status: The act of changing one’s immigration status in the United States, most commonly used to refer to applying for and obtaining Lawful Permanent Resident Status in the U.S.

Admitted: Lawfully entering the United States after inspection and authorization by a US immigration official

A‐ Number: Alien Registration Number; unique nine digit number assigned by Department of Homeland Security to anyone who applies for an immigration benefit or who is detained by immigration authorities

Arriving Aliens: undocumented immigrants claiming asylum at a CBP border crossing

Asylum: A path to legal immigration status based on fear of persecution on a protected ground

BIA: Board of Immigration Appeals; the appellate tribunal under EOIR to which immigration judge decisions are appealed

CAT: Convention Against Torture, a UN Convention that forbids nations from removing people to any country where it is more likely than not they will be tortured with the acquiescence of their government

CBP: Customs & Border Protection; an agency which is part of the Department of Homeland Security and tasked with securing the nation’s borders. CBP is divided into the Border Patrol and the Office of Field Operations.

CFI: Credible Fear Interview; initial screening of arriving asylum seeker’s statement of fear of persecution for persons not previously removed or ordered removed in Expedited Removal Proceedings, conducted by an Asylum Officer to determine if the person merits a hearing before an Immigration Judge to seek asylum

Deportation: Forcible removal of a non‐citizen from the United States when the non‐citizen has been found removable for violating the immigration laws (commonly known as deportation but renamed "removal" in the law in 1996)

Derivative: A noncitizen who obtains or is eligible to obtain lawful status based on association of another beneficiary or applicant (e.g., through a spouse or parent)

EAD: Employment Authorization Document; approval for non‐citizen to work in the United States; application is on Form I‐765

EOIR: Executive Office for Immigration Review; under the Department of Justice and administers the nation's immigration court system including the Board of Immigration Appeals

EWI: Entry without Inspection; entering the United States without undergoing required inspection by government officials

Green Card holder: Colloquial term for Lawful Permanent Resident

Form I-589: The ICE form used to apply for asylum, withholding of removal, and/or protection under the Convention Against Torture

ICE: Immigration and Customs Enforcement, the agency within the Department of Homeland Security responsible for enforcing the detention and removal of non‐citizens within the United States

Inadmissible: Refers to a category of criminal or immigration violations that result in temporary or permanent restrictions on the non‐citizen’s ability to enter the United States or adjust status from within the United States

IJ: Immigration Judge; Judge in Immigration Court under EOIR

INA: Immigration and Nationality Act; main statutory basis of immigration law

Lawful Permanent Resident (LPR): A person granted status to work and live in the U.S. permanently (barring certain criminal or other misconduct) and who can apply to obtain U.S. citizenship through naturalization after a certain number of years in status

Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP): The policy, often referred to as “Remain in Mexico,” that required migrants to wait in Mexico for their U.S. immigration court hearings along the U.S.Mexico border. MPP under the Trump administration is referred to as “MPP 1.0”; the courtordered iteration under the Biden administration is known as “MPP 2.0.”

Naturalization: The process by which a Lawful Permanent Resident can apply to become a US citizen

NTA: Notice to Appear; document laying out immigration charges against a person in removal proceedings

Parole: Mechanism by which ICE may release from detention to an informal sponsor a non‐citizen who has arrived at a border or port of entry and is seeking asylum in the United States

Removal Proceedings: Proceeding to determine if a person who is in the US should be removed or if a person seeking to enter into the U.S. should be allowed to come into the country

RFI: Reasonable Fear Interview; initial screening of non‐citizen’s statement of fear of persecution for persons previously removed or non‐LPRs in certain Expedited Removal Proceedings, conducted by an Asylum Officer to determine if the person merits a hearing before an Immigration Judge to seek withholding of removal or CAT protection

Status: Classification of person under immigration law (e.g., LPR)

Title 42: A pandemic-era policy that relies on a provision of the U.S. health code to expel migrants along the southern border without providing them an opportunity to seek asylum.

T‐Visa: A visa for victims of severe forms of human trafficking

USCIS: United States Citizenship and Immigration Services; branch of the government responsible for immigration application processing

Visa: A document issued by a U.S. Consulate/Embassy authorizing a person to apply for admission/entry into the United States

U‐ Visa: A visa for certain victims of serious crime committed within the United States who have cooperated with law enforcement

Withholding of Removal: A defense to deportation that allows an individual to remain indefinitely within the United States but without permanent status if it is more likely than not they will be persecuted in country of origin on the basis of a protected ground

PRIMER ON GENDER-RELATED PERSECUTION

What is Gender-Related Persecution?

• Brief History: Under asylum law, gender is not an explicitly protected ground. Since 1985, gender was recognized as a possible “particular social group” thus becoming a qualifying ground for asylum protection under U.S. and international law. Enforcement against gender-related persecution is increasing in international tribunals and human rights bodies. However, from 2018-present, recognition of gender-related persecution under U.S. asylum law is in a time period of extreme fluctuation. Sexual orientation is currently strongest gender-related ground for asylum.

• Definition: Severe harm targeted against women, men, girls, boys, LGBTQ+, non-binary and gender non-conforming persons as punishment for transgressing “accepted forms of gender expression.”

• Accepted forms of gender expression: Social rules that dictate roles, behaviors, activities, or attributes. E.g., freedom of movement, reproductive options, gender acceptable to love and marry, opportunity to study and/or work, how to dress, etc.

• Examples of Severe Harm: Rape, enslavement, torture (including severe beatings), murder, etc.

• Gender narratives rationalize severe harm as an inevitable byproduct of the person’s action or a “deserved” punishment.

• Remember: Sexual violence is a form of gender-based violence, but gender-based violence more broadly encompasses harmful acts on the basis of gender.

Why is Understanding Gender-Related Persecution Important?

• In Latin America, as compared to other regions, gender-related persecution occurs at extremely high rates.

• Femicide (Female Homicide) Rates by Country (2022):

o El Salvador (#1)

o Venezuela (#4)

o Honduras (#7)

o Guatemala (#8)

o Mexico (#11)

o Colombia (#19)

Perpetrators of Gender-Related Persecution

• Government

• Armed Actor + Government Unable / Unwilling to Protect

• Private Actor + Government Unable / Unwilling to Protect. Unwilling most common due to gendernarratives thatharmwas “deserved.”

Types of Gender-Related Persecution At-A-Glance

• Sexual Violence as Symbolic Act of Power. Often used to humiliate, degrade, emphasize powerlessness of males perceived to be able to oppose armed groups. Often perpetrated

by men who fear they will be perceived as “weak” if their partner does not conform with gender narratives.

• Gender Regulation of Gender Non-Conforming and LGBTQ+ Individuals’ Behavior Often results in “corrective rape,” public beatings, or death.

• Gender Regulation of Women’s and Girls’ Behavior and Dress. Usually a narrative of “good girls” and “bad girls.” Governments, armed actors, and private persecutors may forbid women from wearing clothes, certain hairstyles, holding jobs, or leaving the house.

• Gender Regulation Through Reproductive Violence. Control reproductive actions and decisions, such as through forced abortions, forced pregnancies, and sexual slavery.

• Gender Regulation and Racism. Gender narratives that women of certain ethnicities are innately lustful and sexually deviant to rationalize focus of sexual violence. Narratives that all “good women” must fit an image may combine with racism, leading to use of coded racist language, such as telling a woman she is “small” or “dark” to insult her and justify physical abuse.

Common Examples of Gender-Related Persecution

• A woman is raped and beaten for working at a job not considered appropriate for women or because her clothing was deemed inappropriate. Police do not investigate or protect her because she “deserved it.”

• Woman suffers severe beating either for her belief in gender equality or her actions (imputed opinion) that imply she believes men and women are equal. Harm usually worsens as woman becomes more independent.

• A woman is raped by an armed group to humiliate and “emasculate” the man who is considered to be her “protector.”

• Woman is raped as gender-specific punishment for refusing to recognize the dominance of an armed group.

• Men or women are tortured because of suspected homosexual behavior.

• Teenage girls and boys are separated into two groups. Teenage girls are enslaved for sexual violence and forced household labor. Teenage boys are enslaved to fight in the armed group.

• Young men of a certain age are wrongfully imprisoned or forcibly disappeared as they are perceived to be “gang members” and therefore likely to be dangerous to the government.

Remember:

• Look for multiple protected grounds. Gender narratives often combine with other discriminatory narratives such as racism to reinforce persecution. People with marginalized identities (racial, ethnic or religious minorities, women, girls, LGBTQ+) are vulnerable to compounding harms.

• Intent and motive are different. The fact that perpetrators act to gratify a sexual motive or desire does not cancel or replace a discriminatory intent(s) to persecute the person.

* Note - The lists ofpotential persecutorsand marginalized indigenous groups are non-exhaustive.

History

BOLIVIA

• Has experienced significant political instability, frequent military coups, and corruption since gaining independence from Spain in 1825.

• Established democratic civilian rule in 1982.

• Indigenous groups make up a significant share of population and have faced discrimination and marginalization.

Recent Events

• 2023-2024: Faced a significant dollar shortage which has led to inflationary pressures and exacerbated tensions within the ruling MAS party. Anti- and proMorales protesters blocked main roads and caused fuel and food shortages.

• 2020: Election of President Luis Acre (Movement for Socialism party).

• 2019: Amidst allegations of electoral fraud in the October election and coup, President Morales resigned and fled to Mexico.

COLOMBIA

• State power and land is fracturing as the government struggles to maintain control against armed quasistate actors.

• Longest running armed conflict in the Western Hemisphere.

• Note that circumstances are evolving rapidly in Colombia and these conditions may not reflect the current status.

• 1/21/2025: President Petro declares state of emergency as guerrilla attacks kill dozens and force thousands to flee their homes.

Persecutors*

State Actors

• Police (Unidad Táctica de Operaciones Policiales)

• Military (Fuerzas Armadas de Bolivia)

Political Parties

• Movement for Socialism (MAS)

• Democrats (Social Democratic Movement)

• National Unity Front (UN)

• Civic Community (CC)

Political

Political, Paramilitary, Guerrilla, & Criminal Groups

• AUC (Autodefensas Unidas) - Paramilitary group perceived as an extension of Colombia’s armed forces which has been accused of delegating to AUC the task of murdering

Common Fact Patterns

• Supporters of political parties targeted due to government’s fragmented control. Forces deployed against protesters

• Targeting of journalists and whistleblowers who oppose government policies.

• Members of political parties targeting opposing groups (e.g., Pro Evo Morales supporters (PEM) and MAS supporters).

• Indigenous groups targeted for control of land and disputes regarding resource extraction (e.g., mining and deforestation).

Human Rights

• Excessive use of force by security, arbitrary detentions, and torture.

PSGs

• Gender-based violence particularly against Indigenous women

Marginalized Indigenous Groups*

• Quechua, Aymara, Chiquitano, Guaraní, and the Moxeño.

CAT

• Quasi-state guerrilla organizations kidnapping, killing, torturing, and displacing individuals as groups fight for control of territory, the cocaine trade, and other illicit economies. These groups may act with impunity in “red zones” where they have effectively ceded control from the Colombian government and become quasi states that tax, run state programs, and control police.

* Note - The lists ofpotential persecutorsand marginalized indigenous groups are non-exhaustive.

History

• On-going “red zones,” not under effective control of Colombian government.

• Experiencing an internal displacement crisis as millions of people flee conflict zones.

• Leftist President Petro has faced public opposition from the military as the top army commander resigned in protest of his election. Despite significant environmental achievements, Petro has recently seen approval ratings plummet as peace talks between the Colombian government and violent groups crumble.

• On-going land reform, reparations, and restitution for victims of conflict, particularly affecting AfroColombian and Indigenous groups.

Recent Events Persecutors*

• 2024: Between January and June 2024, the United Nations OHCHR reported 52 massacres.

• 2023: Fluctuating ceasefires with armed groups. On July 5, last active armed rebel group (ELN) agreed to truce, but splinter groups could form.

• 2023: Former leader of AUC, responsible for widespread disappearances, named as Peace Manager.

• 2022: President Petro is first former member of an armed political group to become president.

• Petro allegedly connected with current guerillas (political armed groups). Family arrested for narcotraffickers links.

• Military/police are right-wing. Oppose President Petro.

peasants and labor union leaders, amongst others suspected of supporting the rebel movements.

• ELN (National Liberation Army) - Radical MarxistLeninist guerrilla group with thousands of armed members. Peace talks suspended in January 2025 after multiple massacres.

• FARC - Marxist–Leninist guerrilla group with tens of thousands of members known for taxation, administration of regional resource production, and trafficking. Has had at least 10 former members elected to Congress.

• Autodefensas Gaitanistas (Gulf Clan) - Powerful crime syndicate with approx. 6000 armed members; recruits its members mainly from former right-wing paramilitaries.

• This is a non-exhaustive list. Each of these groups may have splinter groups working for/against them.

Political

Common Fact Patterns

• Supporters of political parties targeted due to government’s fragmented control. Law enforcement may target President’s party.

• Target family members to extort business owners to assert territorial control and fund armed conflict.

PSGs

• LGBTQ+ individuals sometimes targeted by socially conservative armed groups. Gender-based “codes of conduct” used to control and reinforce machismo ideals, pervasive in Colombian society. Recent peace efforts have intensified risk to women & LGBTQ+ leaders.

• Landowners: courts have recognized “landowners who refuse to cooperate with FARC” and “educated landowning class of cattle farmers” as cognizable PSGs

Race/Nationality

• Indigenous Peoples, Afro-descendants, and peasant communities are disproportionately affected by armed conflict.

Marginalized Indigenous Groups*

• Wayuu, Paéz (Nasa), Emberá, Zenú, and the Arhuaco.

* Note - The lists ofpotential persecutorsand marginalized indigenous groups are non-exhaustive.

History

CUBA

• Post-Spanish American War: U.S. maintained close relationship with Cuba.

• Batista regime: Widespread human rights abuses.

• 1959: Cuban Revolution with widespread killings and political repression resulted in multiple waves of people fleeing Cuba.

DOMINICAN REPUBLIC

• Mid-1900s: Brutal dictatorship (Trujillo). Caamaño Revolt in 1965 led to a Dominican civil war that ended with deployment of troops by the Organization of American States (OAS).

• Trujillo regime antagonistic towards women as equal political actors. Resistance to dictatorship culminated

Recent Events

• 2023: Cuban President Miguel Diaz-Canel wins second, fiveyear term.

• 2023: Demonstrations triggered by blackouts, shortages and deterioration of living conditions

• 2022: Referendum legalizing same-sex marriage approved.

• 2021: Country-wide prodemocracy protests were met with widespread repression. Hundreds still imprisoned.

• 2024: President Luis Abinader won a second term.

• 2013: Stripped citizenship from many people of Haitian descent. Increased targeting of anyone perceived to be Haitian.

• High rate of femicide and gender-based attacks, including acid attacks, and frequent attacks against LGBTQ+ persons.

Persecutors*

Political Parties

• Cuban Communist Party. Widespread use of “white torture,” which leaves no visible marks. Other common torture tactics include: “shakira,” “el potro,” and “cama turca,” all of which involve binding/cuffing hands and feet and limiting mobility of subjects for long periods of time.

Political

Common Fact Patterns

• Imputed: Failing to attend government rallies or hang appropriate government memorabilia will be seen as a political opinion.

• Other examples of political opinion including criticizing the government on social media or protesting peacefully.

• Women’s rights: Police opposed non-state programs that focus on gender violence and harass groups of women assembling to address and advance gender equality and women’s rights.

Race

• Afro-Cubans at particular risk of targeting by police/government forces

Human Rights

• Widespread torture and mistreatment of prisoners.

• Government security forces, particularly for those perceived as Haitian.

• Private individuals, particularly against young women and women with disabilities.

PSGs

• Prevalent societal view that women and girls of reproductive age (~12+) should exclusively be “wives-mothers.”

• High rate of child marriage despite ban on formal child marriages in 2021 due to belief that it is easier to force girls to occupy the wife/mother role.

Torture

• Killing and torture of civilians by government forces with impunity.

* Note - The lists ofpotential persecutorsand marginalized indigenous groups are non-exhaustive.

History

Recent Events Persecutors*

Common Fact Patterns in assassinations of several women activists.

• Mass killings, expulsions of Haitians and those of Haitian descent.

ECUADOR

• Long-standing structural problems related to widespread poverty and ineffective government, which struggles to meet citizens’ basic needs. Institutionalized impunity for discrimination against women, AfroEcuadorians, Montubio/Mestizo, and Indigenous groups.

• Nov. 2023: Daniel Nooba was sworn in as president.

• May 2023: President Lasso dissolved the legislature prior to impeachment vote. Lasso governed by decree for six months before new elections.

• Security forces’ deployed to quell women’s marches and widespread protests by Indigenous groups.

• Multiple assassinations of elected officials and candidates for elected office. Repeated states of emergencies due to intensifying violence surrounding competition between criminal groups for territorial control. Jails alternate between gang and military control.

Criminal groups

Regional and local gangs, potentially affiliated with Colombian guerilla group, the FARC, Mexican cartels (Sinaloa or Jalisco New Generation), and other multinational criminal groups.

• Los Choneros (recent assassination of head of Choneros)

• Los Tiguerones

• Los Lagartos

• Los Lobos

Criminal groups are often supported or protected by state officials.

Political

• Supporters of political parties targeted due to government’s fragmented control.

• Target family members to extort business owners for financial gain, to assert territorial control.

PSGs

• No government investigations of multiple deaths/disappearances of LGBTQ+ individuals.

• Gender-based violence particularly impacts teenage girls in school + Indigenous, Afro-Ecuadorian, and Montubio/Mestizo women.

• Restrictions on access to abortion.

• Lack of enforcement of Indigenous peoples’ rights.

Marginalized Indigenous Groups*

• Quichua, Huaorani (Waorani), Shuar, Achuar, and the Sápara.

* Note - The lists ofpotential persecutorsand marginalized indigenous groups are non-exhaustive.

History

Recent Events Persecutors*

• Recent runoff election, elections marred by violence, including the killing of journalist and former legislator Fernando Villavicencio who was running for president.

EL SALVADOR

• Civil war in 1980s characterized by widespread violence, massacres and sexual violence against civilian non-combatants.

• Slow progress toward peace accord; as state capacity has been slow to develop, criminal gangs have flourished and displaced the state in many communities as de facto governing authority.

• Among highest rates of femicide in world, arising out of historical context in which gender-based violence often used as tool for obtaining and maintaining power.

• Feb. 2024: El Salvador’s incarceration rate is now the highest in the world. The government has arrested and detained more than 76,000 people on the basis of alleged gang affiliation Prison system at 148% capacity.

• July 2023: 72,000+ people arrested without due process (the right to a fair trial or arrest warrant) for suspected gang affiliations. Mass trials on gang charges previewed by government as option for adjudicating criminal charges.

• Early 2022: President Nayib Bukele enacted a state of emergency due in response to gang violence. Creating the now-called “Bukelismo” model, government uses extreme anti-gang tactics, noted above. Extrajudicial

Criminal organizations

• MS-13 (Mara Salvatrucha)

• 18th Street Gang (Calle 18, Barrio 18, Mara 18, La 18)

• The Rebels 13 State actors

• Police/security services Other

• Spouses/Partners

Common Fact Patterns

PSGs

• Government targets people, usually young men, suspected of being gang members.

• Gang targets business owners seeking protection payments (often referred to as “la renta”) as well as principal’s family members to compel compliance.

• Gang targets individuals who live within gang’s territorial control and refuse to comply with gang dictates and directives, including demands to join or collaborate with the gang.

• Gangs target anti-gang police units.

• LGBTQ+ individuals targeted by criminal organizations and police.

• Women who are victims of domestic violence. May be considered “property” by domestic abuser or criminal gang. Gangs may pick out and identify vulnerable teenage girl as “property” of the gang or individual gang members and a “girlfriend,” irrespective of whether relationship is consensual (sexual enslavement).

• Women expected to accept violence for failure or refusal to conform with gendered roles, e.g., working, dressing “provocatively,” or objecting to domestic partner’s behavior.

Marginalized Indigenous Groups*

• Nahua- Pipil, Lenca, Cacaopera (Kakawira), and the Maya Chortí.

* Note - The lists ofpotential persecutorsand marginalized indigenous groups are non-exhaustive.

History

Recent Events Persecutors*

Common Fact Patterns killings, rape, torture, disappearances also increase.

• Government created “super prison” to hold 40,000 gang members and militarizes jails.

GUATEMALA

• Prolonged civil war known for mass human rights violations against Indigenous communities, particularly sexual violence against Indigenous women

• Among highest rates of femicide in Americas.

• 2024: Arevalo new president.

• 2023: Officials, lawyers, and judges fighting against corruption and impunity are targeted by government. Widespread unrest due to 2023 elections.

• June 2023: US opened temporary offices in Guatemala to assist with entering the US.NGOs and press harassed by government. Journalists jailed.

• 2022: Same-sex marriage ban passed (but not enacted).

Criminal organizations

• MS-13 (Mara Salvatrucha)

• 18th Street Gang (Calle 18, Barrio 18, Mara 18, La 18) State actors

• Police (often under control of a criminal organization)

Other

• Spouses/Partners

PSGs

• Family members targeted for extortion (“la renta”) by gangs.

• Gangs target anti-gang police units

• LGBTQ+ individuals targeted by criminal organizations and police

• Women who are victims of domestic violence. May be considered “property” by domestic abuser or criminal gang. Gangs may pick out and identify vulnerable teenage girl as “property” of the gang or individual gang members and a “girlfriend,” irrespective of whether relationship is consensual (sexual enslavement).

• Women expected to accept violence for failure or refusal to conform with gendered roles, e.g., working, dressing “provocatively,” or objecting to domestic partner’s behavior.

• Indigenous groups targeted by everyone else, including other Indigenous groups

• Land-owning farmers (targeted by both police and gangs).

Marginalized Indigenous Groups*

• Maya (Achi’, Ch’ortí, Itzá, Ixil, Kaq-chikel, K’iche, Mam, Mopan, Q’eqchí,) and the Garífuna.

HAITI

• Haiti transitioned to a democracy following • April 2024: After president’s assassination and prime minister resignation, a

Common Quasi-State Armed Groups (“Gangs”) - Gangs are de facto local authorities

Political Opinion

* Note - The lists ofpotential persecutorsand marginalized indigenous groups are non-exhaustive.

History

Recent Events Persecutors*

Common Fact Patterns the fall of the Duvalier dictatorship in 1986.

• Forced to pay “reparations” to France following independence leading to widespread poverty.

• It has experienced significant political instability, including numerous coups and frequent changes in leadership.

• Presently, nearly half the country’s population experiences acute food insecurity.

• Long history of nonstate armed groups being used by political actors.

• June 2023: Recent earthquake compounds other issues.

HONDURAS

• History of military control and military coups to prevent political change, including use of death

transitional presidential council was formed to govern until elections in February 2025.

• April 2024: Ariel Henry was former prime minister but was unable to return to Haiti due to gang attacks of the airport. Resigned in April.

• 2023: Essentially no government in place and now a failed state following President’s assassination.

• Political figures employ gangs that act on behalf of government or opposition figures.

• Gangs suppress political dissent through assassinations, kidnappings, massacres. Gangs foment protests and destroy polling stations in districts where candidates may lose. where state is nonfunctional, working with national politicians and making political demands.

• Geography can be conflated with gang or political affiliation –individuals report being targeted by a gang for living in an area under control of a rival gang, which may in turn be linked with a particular political party.

• July 2023: Military takes control of jails after a prison massacre and upsurge of violence, raising concerns given past military control.

• G9 and Allies (G9 An Fanmi), or “Revolutionary Forces.” Gang coalition created by former police, linked to ruling party.

• G-Pep. Gang coalition linked to opposition party.

• 400 Mawaozo. Allied with G-Pep

• Nearly 200 others Political Parties

• PHTK

• Prevalisme Movement

• Lavalas Movement

• Bwa Kale

• Zam Kale

Criminal organizations

• MS-13 (Mara Salvatrucha)

• 18th Street Gang (Calle 18, Barrio 18, Mara 18, La 18)

• Sexual violence particularly rape of girls, boys, women, and the elderly—a tactic used by state and criminal actors to instill fear in women and girls, to suppress dissent, and punish women and girls perceived as opposed to whichever faction holds sway in a particular area.

PSG

• Pervasive view that women are “objects” to be owned and controlled.

• Sexual enslavement of young women and girls in return for “protection.” Women in gang-controlled areas are seen as gang property. Sexual violence is used to terrorize the population and demonstrate control.

• LGBTQ+ individuals are singled out by the gang due to their sexual orientation and gender identity.

• LGBTQ+ individuals face widespread threats and harassment, often insulted, called derogatory names (e.g., “masisi”). Religious community leaders sometimes blame LGBTQ+ individuals for natural disasters.

Note: “Magic curses” may be indicative of persecution, reflecting an individual’s intent to harm or kill its target

PSGs

• Family members targeted for extortion (“la renta”) by gangs.

• Gangs target anti-gang police units.

• LGBTQ+ individuals targeted by criminal organizations and police.

* Note - The lists ofpotential persecutorsand marginalized indigenous groups are non-exhaustive.

History

Recent Events

Persecutors*

Common Fact Patterns squads, torture, disappearances.

• Among highest rates of femicide in Americas.

• 2022: Following El Salvador’s “Bukele” model, since of Dec. 6, 2022, ~half of country remains under state of emergency suspending constitutional rights; targeting supposed gang members.

• High crime rate: 3,661 murders in 2022, a homicide rate of 38 per 100,000 people. Honduras has the second highest homicide rate in Latin America and the Caribbean after Jamaica.

• 2021: Xiomara Castro (first female president) elected.

State actors

• Police (often under control of a criminal organization)

Other

• Spouses/Partners

• Women who are victims of domestic violence. May be considered “property” by domestic abuser or criminal gang. Gangs may pick out and identify vulnerable teenage girl as “property” of the gang or individual gang members and a “girlfriend,” irrespective of whether relationship is consensual (sexual enslavement).

• Women expected to accept violence for failure or refusal to conform with gendered roles, e.g., working, dressing “provocatively,” or objecting to domestic partner’s behavior.

• Ban on the sale and use of emergency contraception

Race & Political

• Indigenous groups and environmental activists targeted for control of resources and land.

Marginalized Indigenous Groups*

• Lenca, Miskito, Tolupan, Tawahka, and the Maya- Chortí. NICARAGUA

• Somoza dictatorship overthrown in 1979 by Sandinistas, led by Daniel Ortega, who served as president from 1985 - 1990.

• Ortega re-elected as president in 2007, leading to systemic dismantling of checks on presidential power.

• 2023: 200+ political prisoners expelled and stripped of statehood. Number has risen to 317 in 2024.

• Nov. 2021: Corrupt elections characterized by forced voting/voter intimidation, disappearances, arbitrary arrests.

• April/May 2018: Widespread protests, resulting in massacre of youth protestors by government

Paramilitary

• Sandinista, Sandinista Youth

State actors

• Police

• CPC (Citizen power councils), local groups that report “anti-government” activities to police.

• President Ortega and his wife, the Vice President, repress all forms of dissent in Nicaragua, they do this

Political

• Surveillance and imprisonment of election protestors by state

• Targeting of political opponents, including through new laws criminalizing political expression and via economic deprivation through requirement of a pro-government ID in order to work.

• Use of Sandinista paramilitary organizations to inflict violence and threats of violence against perceived political opponents of the Ortega regime.

Religion & Political

• Beatings, threats, and interfering with religious practices of Catholics and individuals affiliated with Catholic institutions, particularly in Matagalpa, due to Catholic Church’s anti-government position. Clergy targeted in particular.

* Note - The lists ofpotential persecutorsand marginalized indigenous groups are non-exhaustive.

History

PERU

• Civil war between government and Shining Path guerilla group, in which both parties committed violence against civilian noncombatants, including torture and sexual violence, particularly prevalent in lowincome, Indigenous communities in the Andes region

Recent Events

Persecutors*

Common Fact Patterns and paramilitary forces; many NGOs and universities closed or taken over by government. by dismantling civic space, closing media outlets, NGOs and universities, detaining government critics

• Mar. 2023: As of March 2023, 37 of 130 members of Congress were under criminal investigation for corruption/other offenses

• Dec. 2022: President Pedro Castillo removed from office and arrested. Replaced by Dina Boluarte, who received special legislative powers to deal with protests. Ongoing, widespread anti-gov’t protests calling for new elections.

• 130 seats in Congress are now divided into twelve factions

• Gov’t reacted to protests with extrajudicial killings and mass detention of protestors.

Criminal organizations

• Local gangs affiliated with and operating with the backing of multinational criminal organizations.

State actors

• Militant group: MPCP (Militarized Communist Party of Peru)

Political groups

• La Resistencia: a rightwing group that doxes, insults, harasses, and attacks journalists

PSGs

• Increasing femicide and sexual violence.

• LGBTQ+ individuals are viewed as “abnormal,” “ill,” or “deviant” and face violence from public and, sometimes, security forces.

Marginalized Indigenous Groups*

• Miskitu, Mayangna, and the Rama.

Political

• Force deployed against protestors, particularly regarding elections, large-scale development projects, or labor rights.

• Targeting of NGOs and Indigenous activists related to illegal extractive industries.

PSGs & Race

• History of gendered violence as tools of conflict and control, resulting in rising femicides and disappearances of girls and women with minimal government intervention.

• Particularly impacts Afro-Peruvian, Indigenous rural women, and the LGBTQ+ community.

• There is no simple administrative process for legal gender recognition for transgender people in Peru.

Marginalized Indigenous Groups*

• Aymara, Quechua, Asháninka, Matsés, Iskobákebu, Achuar, and the Shipibo.

* Note - The lists ofpotential persecutorsand marginalized indigenous groups are non-exhaustive.

History

VENEZUELA

• Debt crisis and IMF bailout resulted in austerity measures, curtailment of civil rights, and inequality.

• 2013: Former President Hugo Chavez’s death led to ascendance of a chief lieutenant, Nicolas Maduro.

• Close ties with Cuba. Emulation of Cuban socialist system.

• Government policies, severe hyperinflation led to shortages and starvation.

• 66 percent of Venezuela’s population needs humanitarian assistance and 65 percent have “irreversibly lost or exhausted their means of livelihood.”

Recent Events

• Aug. 2024: Post-Election Protests & Violence –Maduro government used state security forces and allied militias to crack down on demonstrators resulting in several deaths and thousands of arrests.

• Jul. 2024: Venezuela held a presidential election where incumbent Maduro claimed victory amid widespread allegations of electoral fraud. Opposition candidate, Edmundo González was reported to have won by a significant margin.

• June 2023: New opposition leader (Marina Corina Machado) barred from public office for 15 years.

• Dec. 2022: Guaido’s interim presidency dissolved. Leftwing political parties uniting for 2024 elections.

• Mass protests in 2014, 2017, and 2019 resulted in arbitrary arrests, torture, and extrajudicial killings.

Persecutors*

State actors

• SEBIN (intelligence agency)

• DGCIM (counterintelligence agency)

• FAES (special police forces)

Paramilitary

• Colectivos (progovernment paramilitary forces that kill, kidnap, extort Maduro regime’s real and perceived political opponents).

• Colombian guerrilla groups: ELN and Joint Eastern Command operate with Venezuelan forces. Criminal organizations

• Tren de Aragua: transnational criminal organization which has expanded throughout Latin America.

Other

• Spouses/Partners

Political

Common Fact Patterns

• Extrajudicial executions, forced disappearances, jailing, and torture of real or perceived political opponents often in collaboration with colectivos; torture often occurs at “El Heliocoide”.

• Targeting of human rights and humanitarian groups, including through arbitrary arrest and imprisonment, surveillance, raids. Use of Colectivos to harm and threaten harm to members of the political opposition.

• Use of justice system to criminalize expression of opposition to Maduro regime.

• Use of sexual and gender-based violence by DGCIM and SEBIN to torture detainees

• Same-sex conduct previously criminalized in military law overturned in 2023, allowing LGBTQ+ individuals to serve openly; reports of widespread discrimination in Venezuelan society against LGBTQ+ individuals.

Marginalized Indigenous Groups*

• Wayuu, Pemón, Warao, Yanomami, and the Añu.

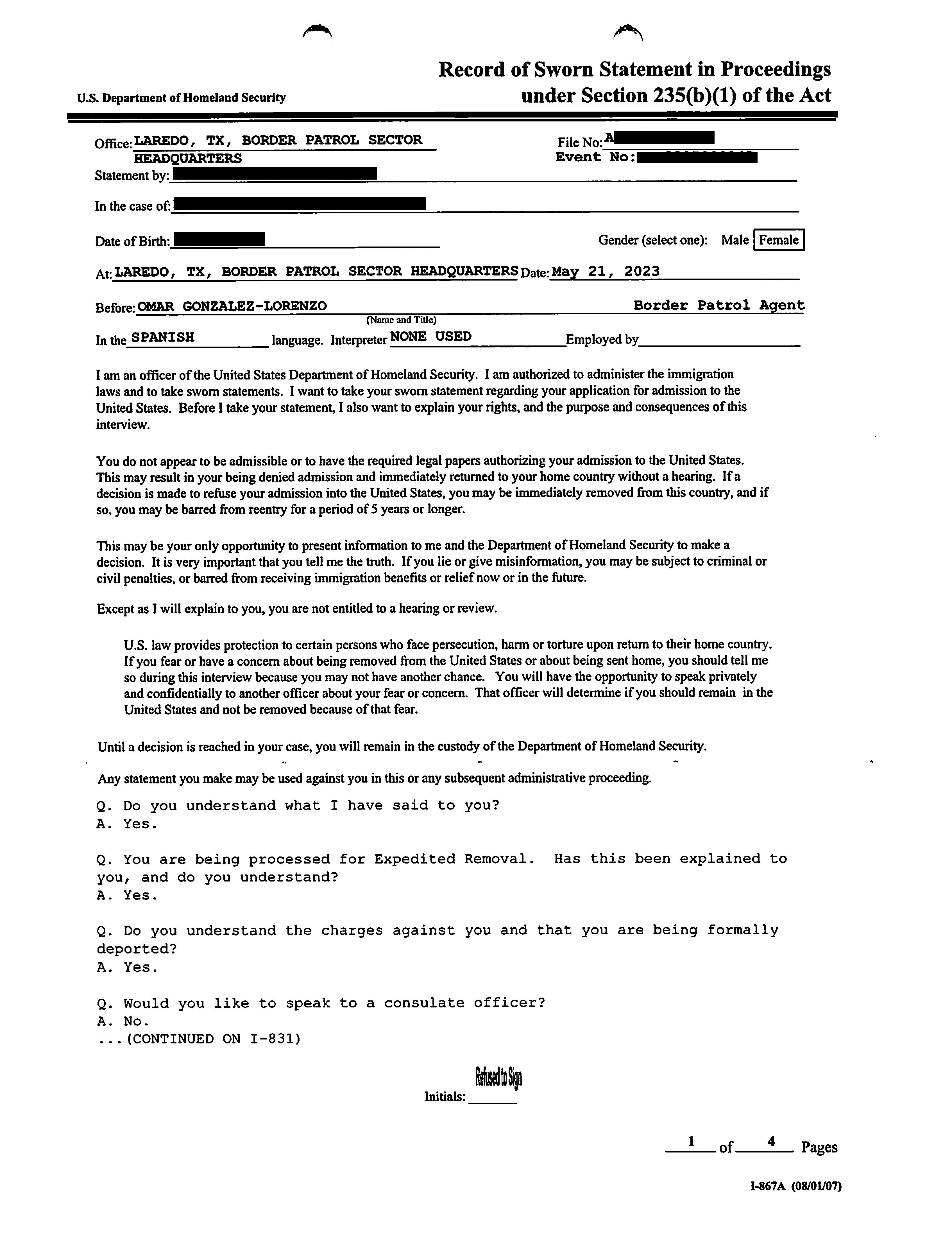

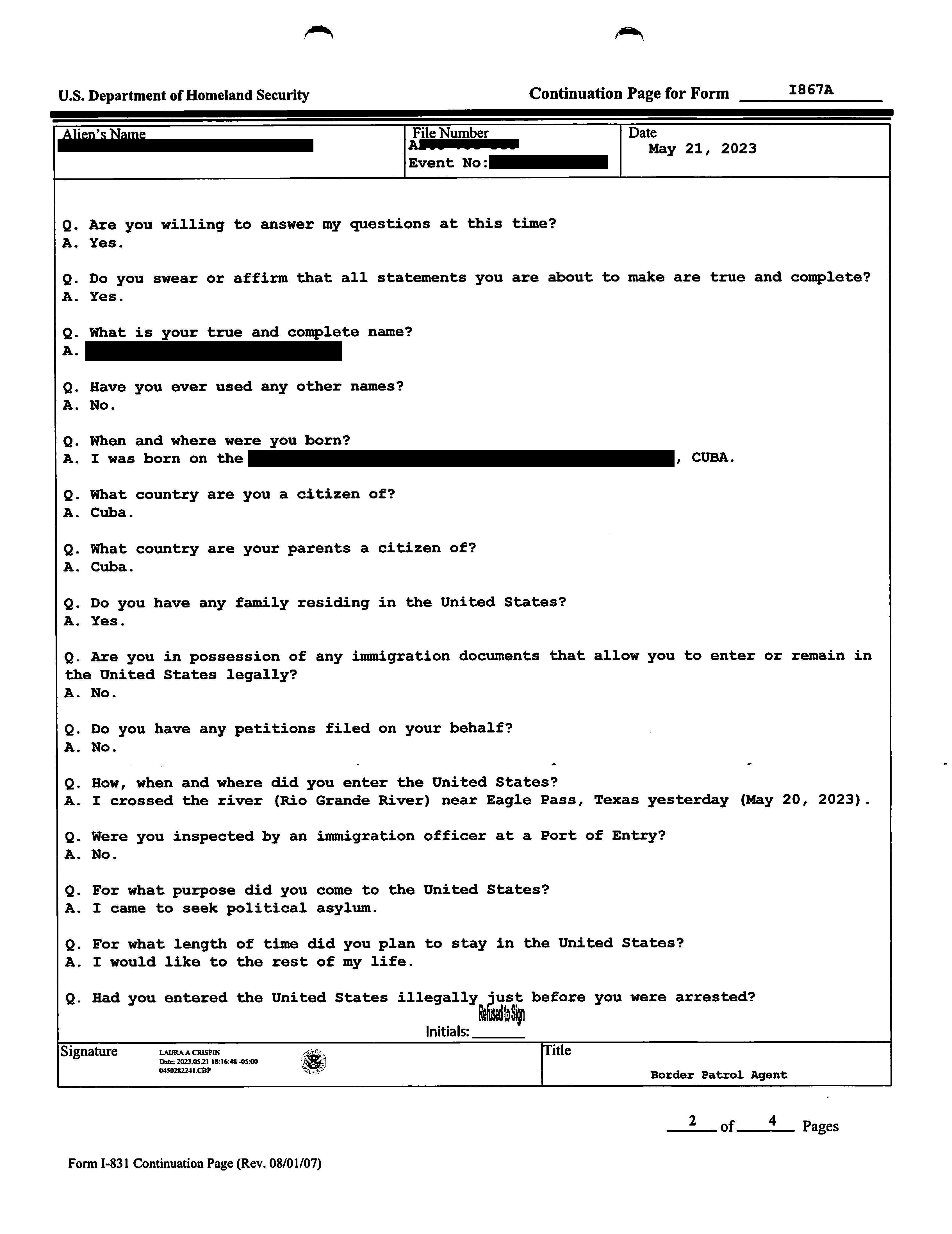

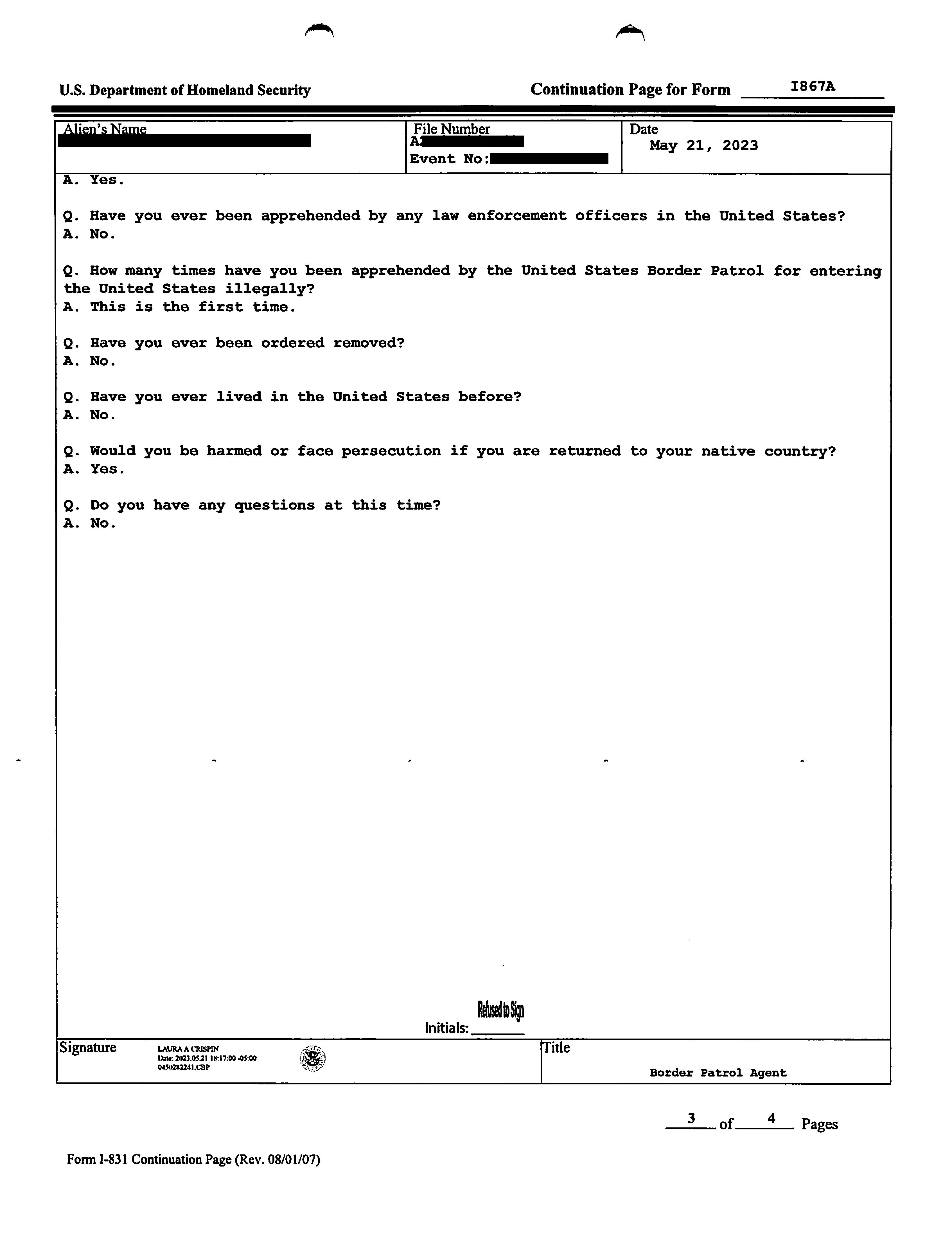

DHS document given to noncitizens to explain Credible Fear Process

Information About Credible Fear Interview

You have been placed in expedited removal proceedings because the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) believes that you may not have the right to stay in the United States. You have also indicated that you intend to apply for asylum, you fear persecution or torture, or you fear returning to your country of nationality or designated country of removal. This notice explains what will happen while the U.S. Government is considering your case, what rights you have, and what may happen to you as a result of statements you make.

PLEASE READ THIS NOTICE CAREFULLY

What is a Credible Fear Interview?

Before DHS can remove you, DHS must interview you to determine if you have a fear of persecution or torture that the U.S. Government needs to consider further. A specially trained USCIS asylum officer will interview you. The credible fear interview is not a formal asylum or withholding of removal hearing or interview. The credible fear interview is a screening to determine if you are eligible for a hearing before an immigration judge or an Asylum Merits Interview with a USCIS asylum officer

You may be detained both before and after the credible fear interview if DHS determines that it is appropriate. The interview will occur no earlier than 24-hours after you receive and acknowledge receipt of this form.

What Happens At Your Credible Fear Interview

At your credible fear interview, you will have an opportunity to discuss your background and experiences in your country and any other country where you fear harm and explain to the USCIS asylum officer the reasons you are pursuing an asylum claim. The officer will take written notes. This may be your only opportunity to provide information about your claim, so it is very important that you tell the USCIS asylum officer about any harm you may have suffered in the past and any harm you fear in the future. You also may be asked about conditions in your country. To demonstrate a credible fear of persecution or torture, you must show the officer that you have a credible fear of being persecuted because of your race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion, or a credible fear of being tortured in your country.

You may request a female or male USCIS asylum officer, if this would make it easier for you to speak about information that is very personal or difficult to discuss. You also have the right to speak with the USCIS asylum officer separately from your family.

It is very important that you:

• Tell the truth during your credible fear interview Your statements may be used in this or in any future immigration case.

• Tell the officer any reasons why you fear returning to your home country or designated country of removal. U.S. law has strict rules to prevent the government from telling others about what you say in your credible fear interview. For example, the U.S. Government will not disclose to your government any information that you provide, except in exceptional circumstances.

Possible Use for Asylum Application

It is also possible that the record from your credible fear interview may be considered your asylum application if you are found to have a credible fear of persecution or torture and are scheduled and appear for an Asylum Merits Interview with a USCIS asylum officer.

Page 1 of 4

DHS document given to noncitizens to explain Credible Fear Process

Whom You May Consult

While you wait for your credible fear interview, you may use this time to prepare and consult with a person of your choice as long as it does not unreasonably delay the interview process. The U.S. Government does not provide you with an attorney or representative, but you may choose to hire an attorney or representative at your expense. You may have a consultant of your choice with you at your interview or participate by telephone.

If you need additional time before your credible fear interview to contact someone, inform a DHS officer about your circumstances and explain the reason you need more time. In order to avoid unreasonably delaying the process, you will need to demonstrate that extraordinary circumstances necessitate that your credible fear interview be delayed or rescheduled. USCIS will decide whether your circumstances merit providing you with additional time. You may also request to have the interview earlier if you are prepared to discuss your case immediately.

A list of representatives who may be able to speak to you for free is attached to this notice. Representatives of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) also may be able to assist you with information regarding the credible fear process:

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees 1800 Massachusetts Avenue N.W., Suite 500, Washington, D.C. 20036 Telephone: 202-296-5191 Email : usawa@unhcr.org Web site: www.unhcr.org

You may call UNHCR toll-free by dialing #566 or 1-888-272-1913 on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays, 2 p.m. - 5 p.m. (Eastern Time).

If you want to call someone, ask a DHS officer for assistance. You may also use the telephone while you are in detention to call a relative, representative, attorney, or friend in the United States. You or the person you call must pay for the phone call, if charges apply.

Interpreters

If you do not speak English well or if you want to be interviewed in a language of your choosing, DHS will provide an interpreter for the interview. The interpreter will be sworn to keep the information you discuss confidential. You may:

• Request another interpreter if the interpreter is not interpreting correctly or you do not feel comfortable with the interpreter.

• Request a female or male interpreter, if this would make it easier for you to speak about information that is very personal or difficult to discuss. DHS will provide them if they are available.

Biographic and biometric checks

Applicants for asylum are subject to biographic and biometric checks of all appropriate records and other databases. USCIS may use your biometrics that were collected by DHS, including biometrics collected by U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) or U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), to check criminal history records, verify identity, determine eligibility, or any purpose authorized by the Immigration and Nationality Act. The privacy notices in this document provide information about the collection and use of this information.

After Your Credible Fear Interview

After your credible fear interview, the USCIS asylum officer will make a determination on your initial screening case. If the asylum officer determines that you have a credible fear of persecution or torture, you will either

Page 2 of 4

DHS document given to noncitizens to explain Credible Fear Process

receive a charging document for a hearing in immigration court or you will be scheduled for an Asylum Merits Interview with a USCIS asylum officer. At the immigration court hearing or USCIS Asylum Merits Interview, the immigration judge or asylum officer will determine whether to grant you asylum or whether you are eligible for other protection from removal. You will receive information about the date, time, and location of this hearing or interview.

If the USCIS asylum officer determines that you do not have a credible fear of persecution or torture, you may ask to have an immigration judge review the asylum officer’s negative determination. If you decline this review, you may be removed from the United States.

Immigration Judge Review of a Negative Credible Fear Determination

If you request that an immigration judge review the USCIS asylum officer’s negative credible fear determination, the immigration judge’s review will usually happen no later than 7 days from the date that you receive your negative credible fear determination. The review will be in person, by telephone, or by video connection. You may consult with a person of your choice before the review as long as it does not cause unreasonable delay. You will receive a copy of the USCIS asylum officer’s determination before the immigration judge review. If any of the information is incorrect, you should tell the immigration judge.

At the review, the immigration judge will decide either that:

• You do not have a credible fear of persecution or torture. You may then be removed from the United States. OR

• You have a credible fear of persecution or torture, and you are eligible for further proceedings in immigration court or an Asylum Merits Interview with an asylum officer where you can apply for asylum or other protection from removal. At any further proceedings in immigration court or during an Asylum Merits Interview, the immigration judge or USCIS asylum officer will determine whether to grant you asylum or whether you are eligible for other protection from removal. If you are ordered removed, you may not be allowed to reenter the United States for 5 years or longer.

After a Positive Credible Fear Determination by an Asylum Officer or Immigration Judge

If you receive a charging document for proceedings in immigration court and wish to apply for asylum, you must file Form I-589, Application for Asylum and for Withholding of Removal. The Form I-589 and instructions on where to file the Form can be found at www.uscis.gov/i-589. Failure to file Form I-589 within one year of arrival may bar you from eligibility to apply for asylum pursuant to INA § 208(a)(2)(B).

If you receive a document called “Information About Your Asylum Merits Interview,” you will receive a notice with the time, date, and location of the Asylum Merits Interview. You will not be required to file a Form I-589 if you are scheduled and appear for an Asylum Merits Interview with a USCIS asylum officer, as the record of the credible fear interview and your credible fear determination will be considered your asylum application.

DHS Privacy Notice

Authorities: The acquisition, preservation, and exchange of information in connection with a credible fear interview and any potential associated asylum adjudication is collected under the Immigration and Nationality Act sections 103, 208, 235 and 241(b)(3), and 8 CFR sections 103, 208, 235, and 1208.

Purpose: The primary purpose for providing the requested information is to determine eligibility for asylum in the United States or other protection from removal.

DHS document given to noncitizens to explain Credible Fear Process

Disclosure: The information you provide is voluntary. However, failure to provide the requested information, and any requested evidence, may delay a final decision or result in the denial of a benefit request.

Routine Uses: DHS may share the information you provide with other federal, state, local, and foreign government agencies and authorized organizations. DHS follows approved routine uses described in the associated published system of records notices [DHS/USCIS-001 – Alien File, Index, and National File Tracking, DHS/USCIS-010 – Asylum Information and Pre-Screening and DHS/USCIS-018 Immigration Biometric and Background Check] and the published privacy impact assessment [DHS/USCIS/PIA-027 USCIS Asylum Division which you can find at www.dhs.gov/ along with EOIR-001, Records Management Information System, 69 Fed. Reg 26, 179 (May 11, 2004) or its successors. DHS may also share the information as appropriate, for law enforcement purposes or in the interest of national security.

FBI Privacy Notice

USCIS may use your biometrics to check the criminal history records of the FBI, for identity verification, to determine eligibility, to create immigration documents (e.g., Green Card, Employment Authorization Document, etc.), or any purpose authorized by the Immigration and Nationality Act. You may obtain a copy of your own FBI record using the procedures outlined within Title 28 C.F.R., Section 16.32. For information, please visit: https://www.fbi.gov/services/cjis/identity-history-summary-checks. For Privacy Act information, please visit https://www.fbi.gov/services/cjis/compact-council/privacy-act-statement.

Noncitizen Acknowledgment of Receipt

I acknowledge that I have been given notice concerning my credible fear interview. I understand that I may consult with anyone I choose before the interview as long as it does not unreasonably delay the process and is at no expense to the U.S. Government.

Noncitizen Signature

Interpreter Certification

Date of Signature (mm/dd/yyyy)

Interpreter was placed under oath and read the form in entirety to the noncitizen in the ____________ language. The noncitizen confirmed that they understood every instruction on the form.

☐ Telephonic interpreter used _

Service/ID if available OR

Interpreter Signature

Date of Signature (mm/dd/yyyy)

4 of 4

Uploaded on: 5/24/2023 at 6:53:44 p.m. (Central Daylight Time) Base City: LRO

Document that initiates docketing with EOIR for an IJ Review after Negative Determination

Asylum Office Notice to EOIR that the Asylum Ban was applied and noncitizen failed "reasonable possibility" standard

Noncitizen requested IJ Review when informed of Negative Determination

Notice to noncitizen that they have been placed into Expedited Removal · because they have claimed fear, not a final order until Negative Determination affirmed by IJ or not appealed

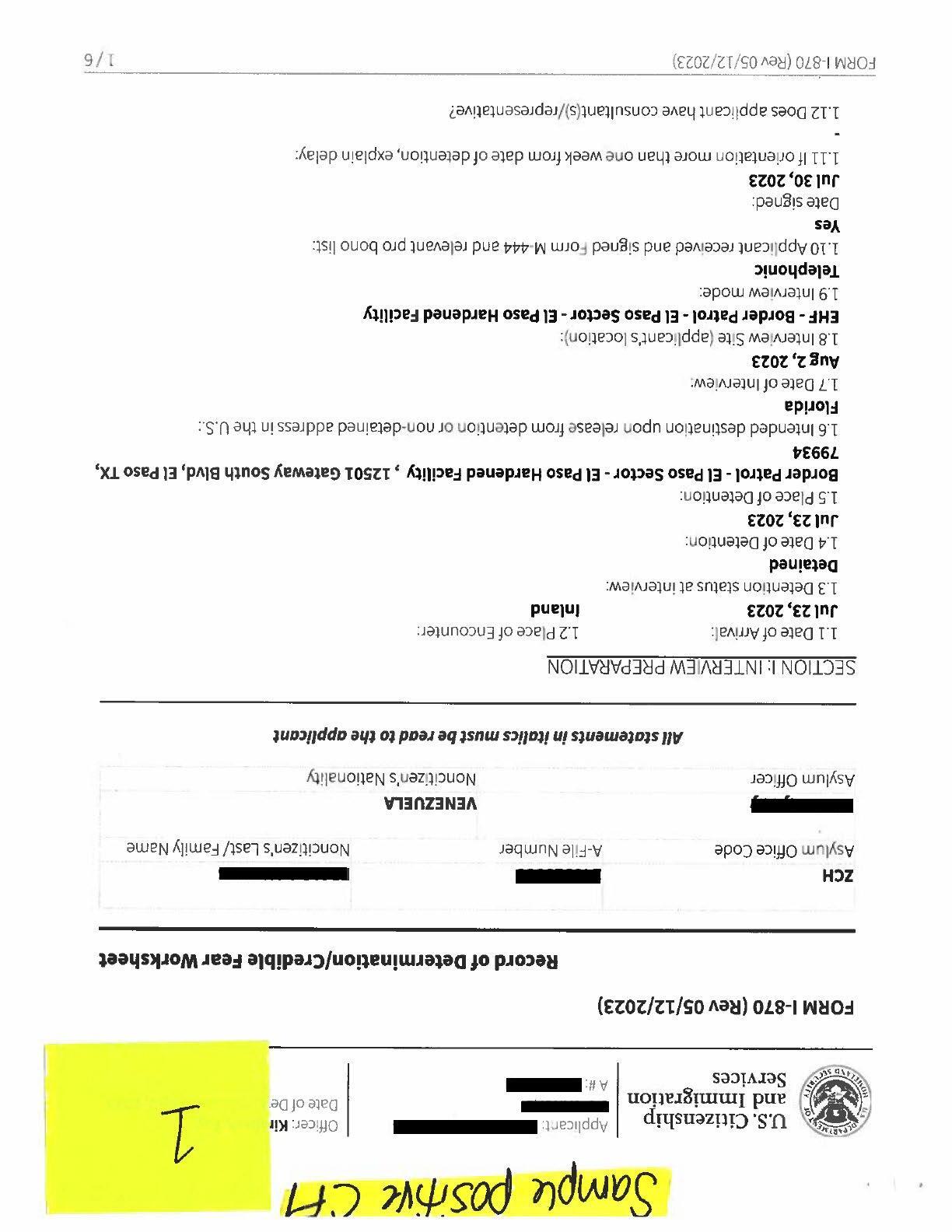

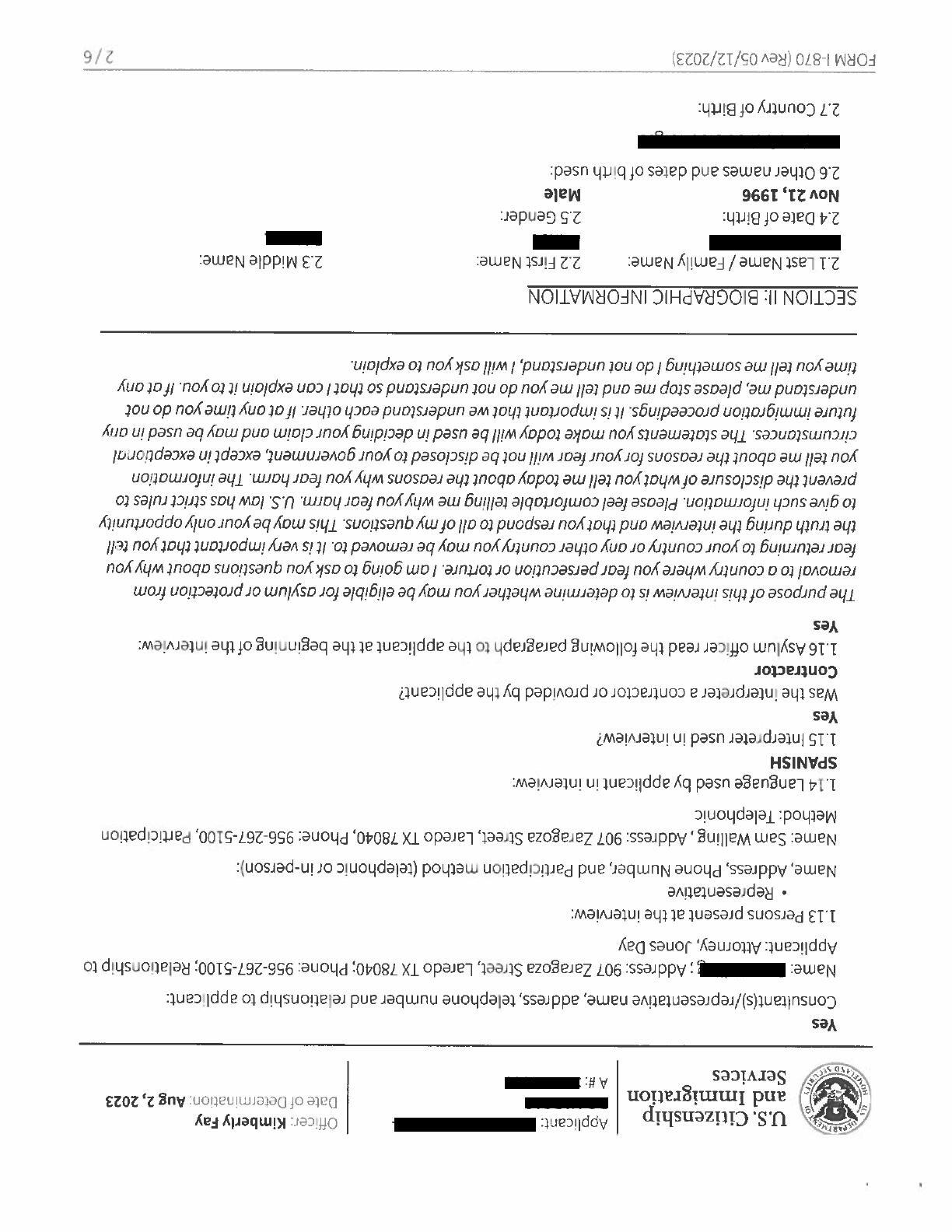

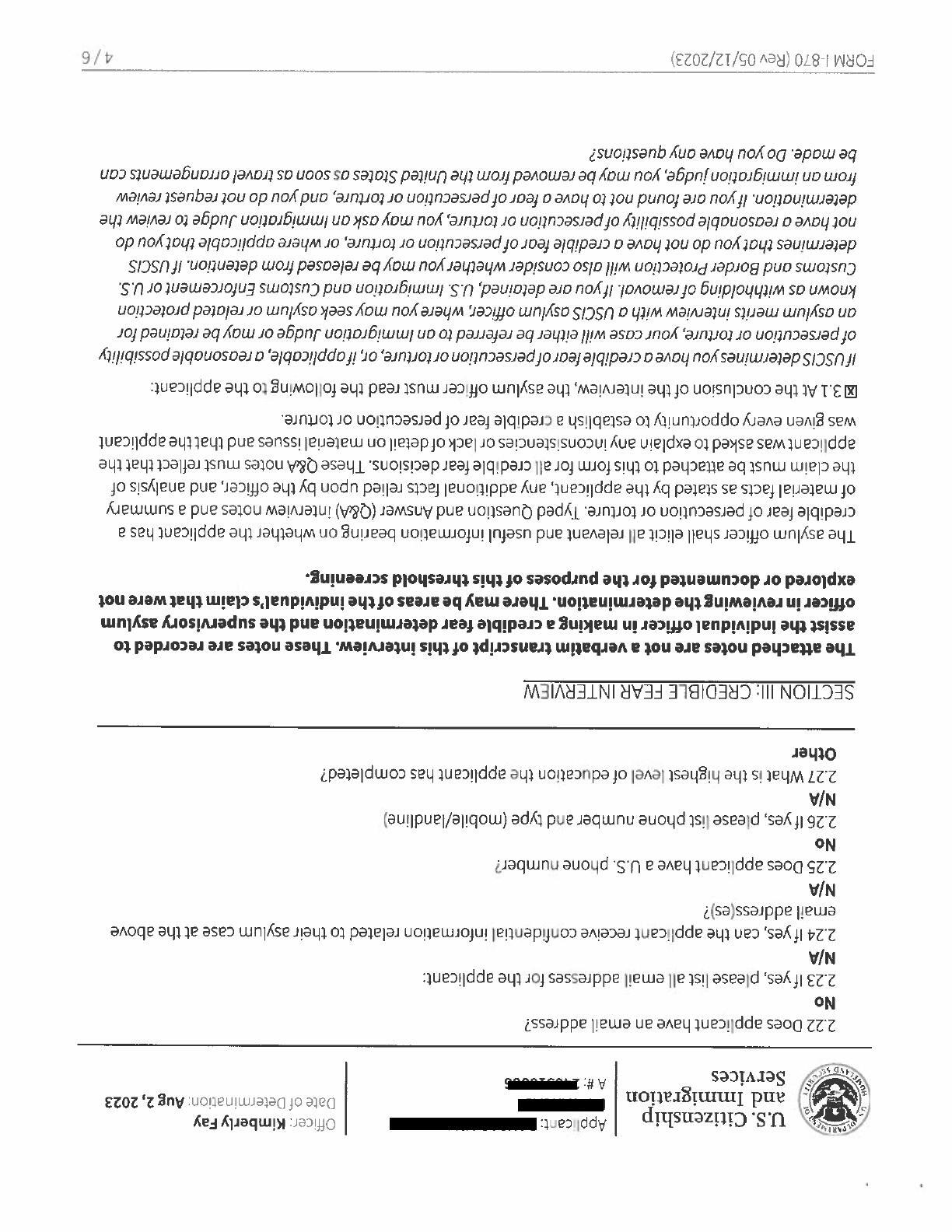

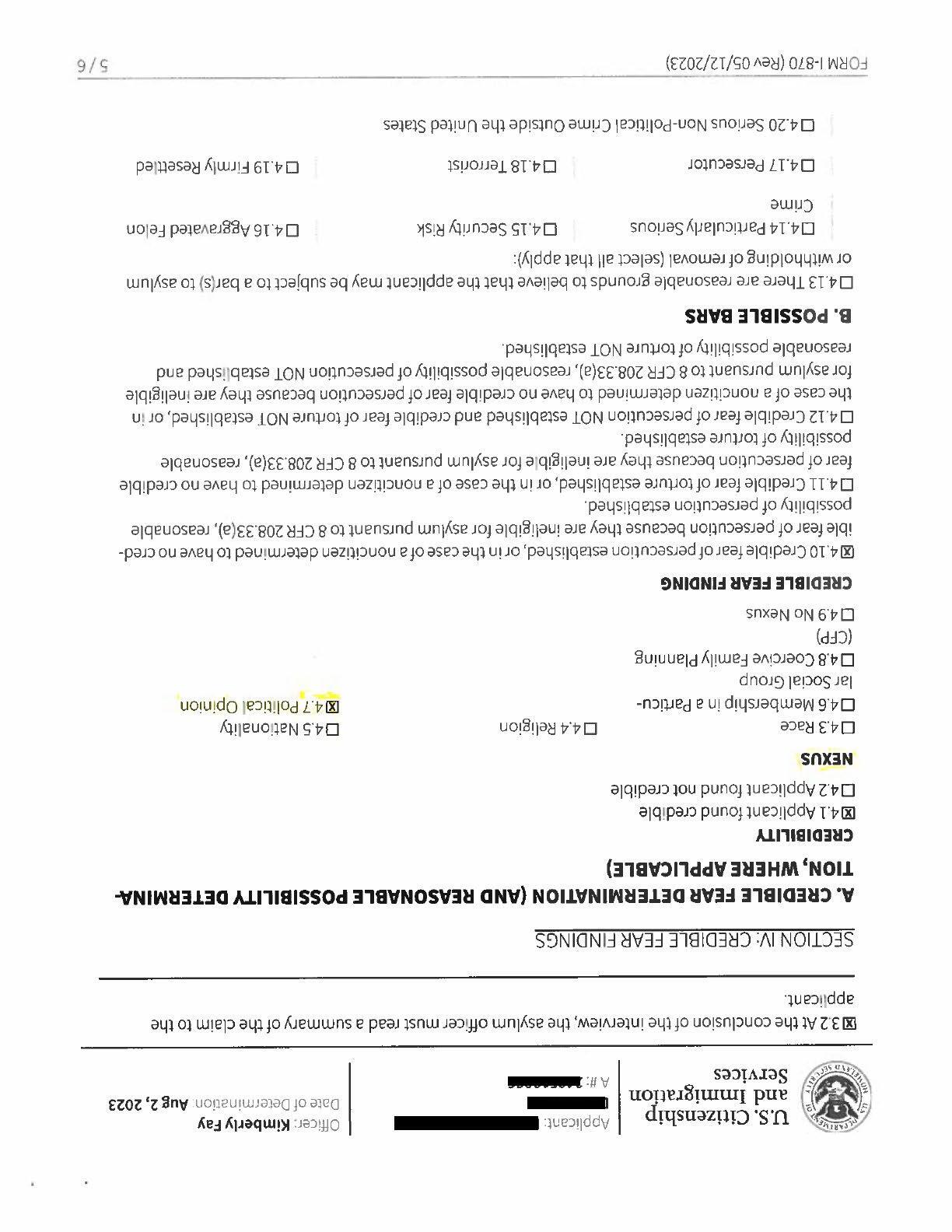

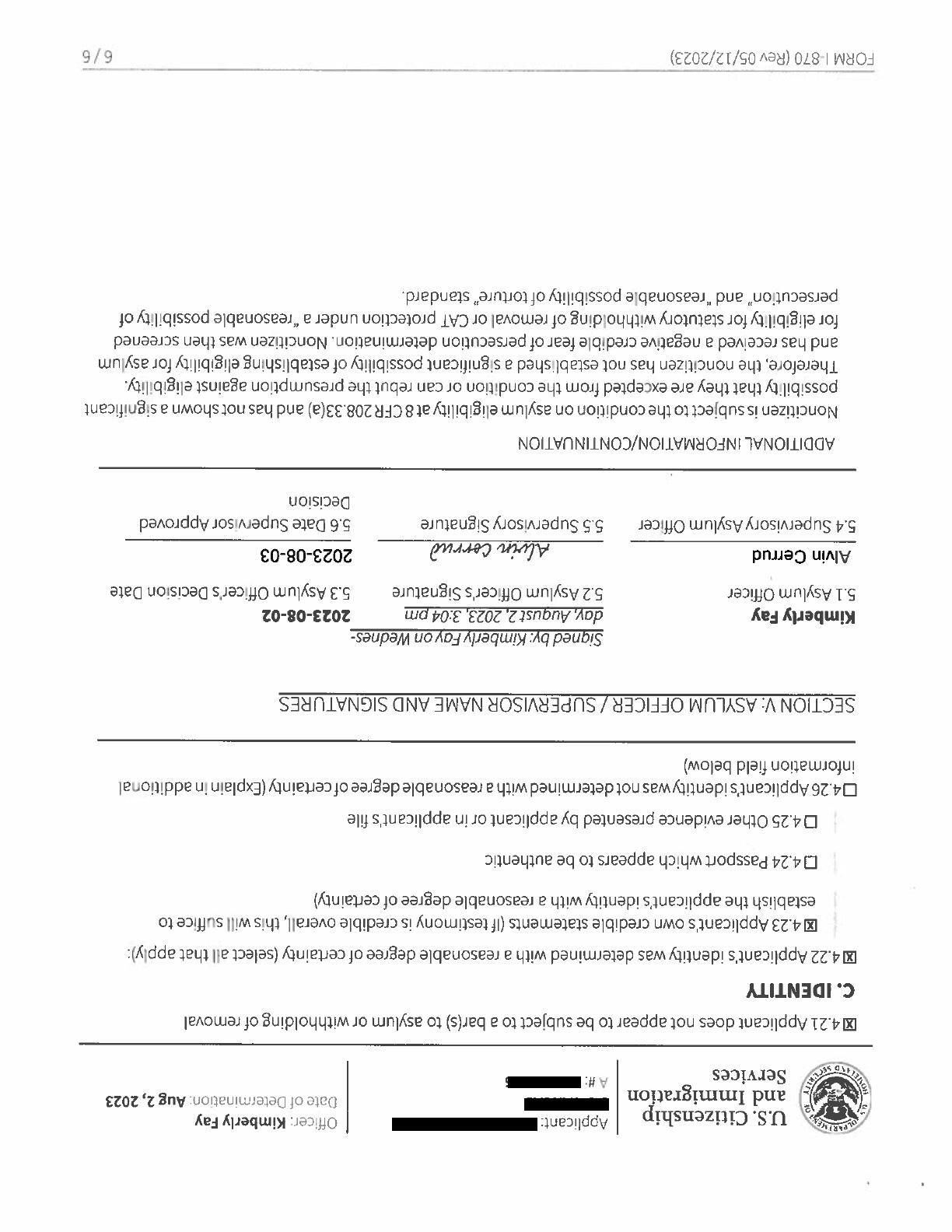

Asylum Office's Worksheet of CFI; including Positive or Negative Determination

Asylum Officer's summary re eligibility for and application of new Asylum Ban

Unclear what test is applied here; noncitizen has a story about threat to life or safety

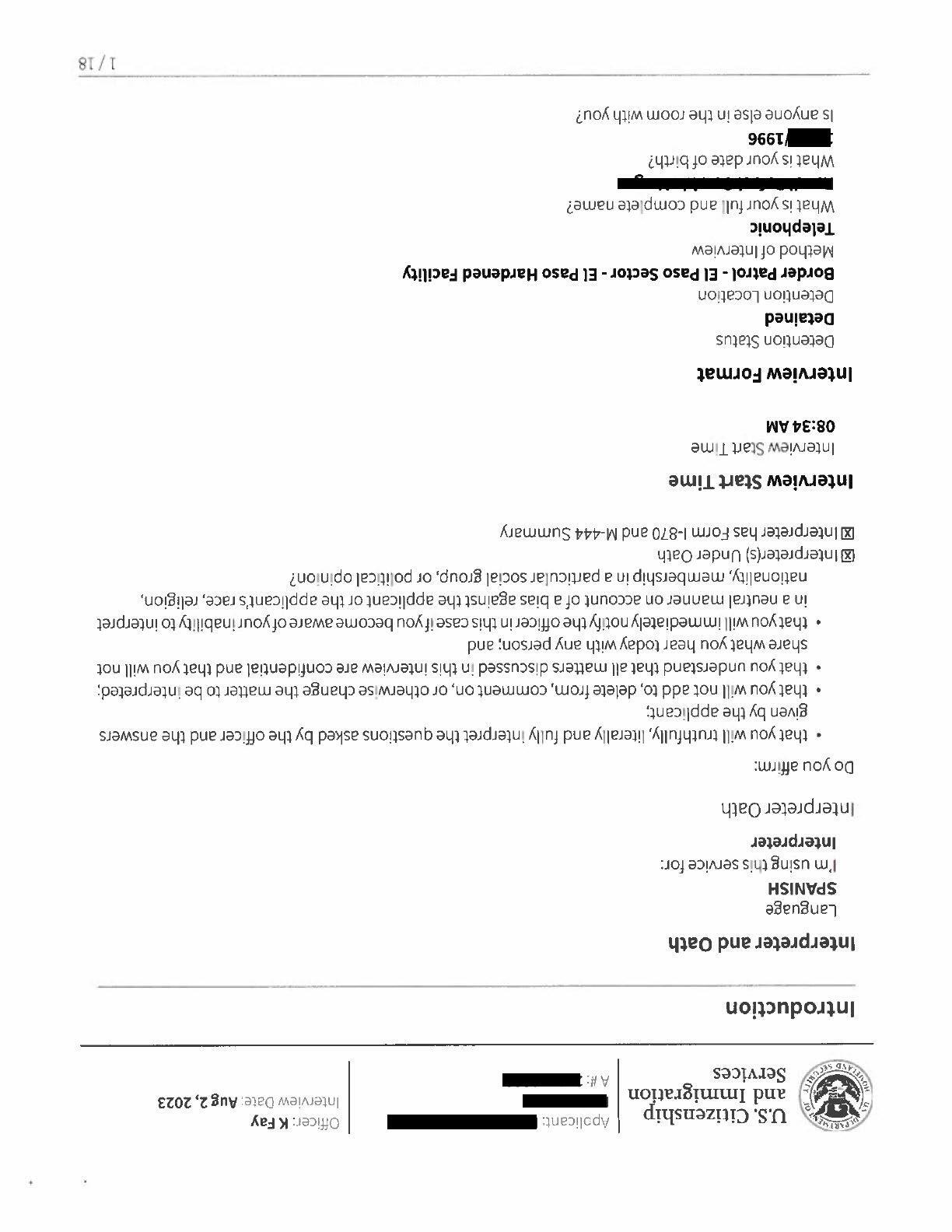

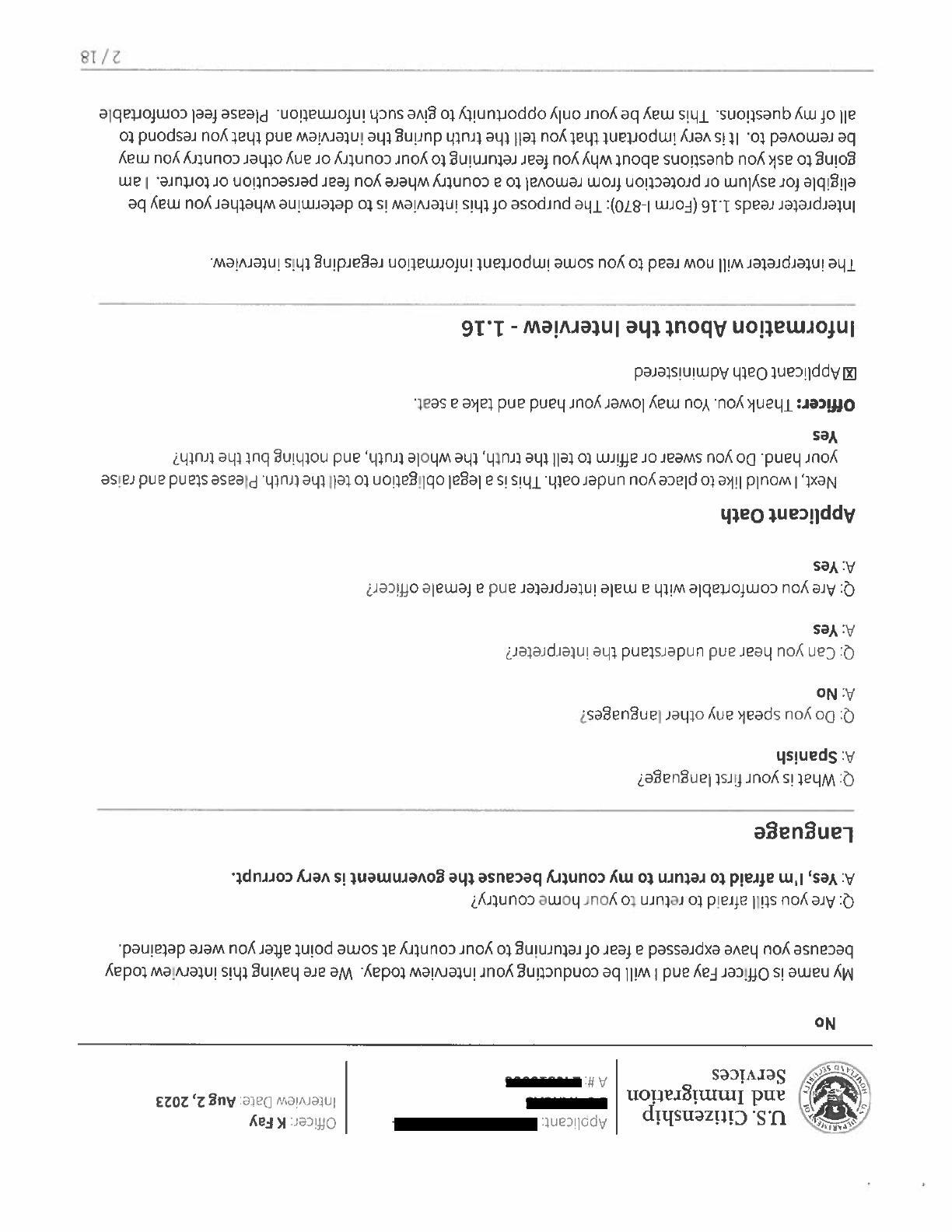

Asylum Officer's notes of CFI—not a transcript!

Offer to withdraw fear claim and agree to be returned to Mexico before the CFI starts

· avoids final order of removal (and 5-year-bar)

· unlikely to be eligible for sponsorship

· can attempt to make a CBP One app appointment

Screening for new Asylum Ban

Test for extreme threat to life or safety unclear

No analysis of how noncitizen failed to rebut

Having found that the new Asylum Ban applies, Asylum Officer renews offer for Voluntary Withdraw to Mexico

Because new Asylum Ban is being applied and noncitizen twice declined Voluntary Withdrawal, substantive interview about their fear commences under "reasonable possibility standard"

But because DHS has designated Mexico as the country of removal, noncitizen's fear of return to Cuba is irrelevant All questions are about Mexico, most of which were asked with regard to whether the new Asylum Ban would be applied

Asylum Officer's summary and last opportunity to correct and add key details

Asylum Officer's analysis of noncitizen's fear of returning to Mexico under "reasonable possibility" standard

Recent Change to United States’ Asylum Law

June 5, 2024: “Securing the Border” Final Rule1

Summary: After President Biden’s “Securing the Border” proclamation, federal agencies issued an IFR that went into effect on June 5, 2024, to “increase the consequences in place for noncitizens who cross irregularly. . . [and] decrease encounter rates at the southern border.”

Key Changes:

1. Noncitizens who enter the U.S. without inspection are presumptively ineligible to apply for asylum. 2 The vast majority of detained migrants are limited to relief (and a positive decision at the fear interview stage) under Withholding of Removal and/or protection under the Convention Against Torture except where the migrant meets one of the following exceptions: 3

a. Suffered an acute medical emergency forcing them to cross;

b. Experienced an imminent and extreme threat to life or safety; and/or

c. Was a victim of cross-border trafficking.

2. “Shout Test:” migrants will not receive a CFI/RFI unless they verbally or nonverbally “manifest” fear of returning to their country or intent to apply for asylum. 4

3. Affected migrants applying for WoR or CAT are subject to an increased CFI/RFI standard, from “significant possibility” to “reasonable probability” of future harm. 5

1 The June 5, 2024 Interim Final Rule became a final rule on October 7, 2024.

2 This rule is in effect when daily crossings over a 7-day period averages is 2,500+. It is withdrawn 14 days after crossings drop below 1,500 per day for a week. It will likely be in effect most of the time and has been since issuance.

3 Note that the IFR does not apply to noncitizens who were processed through the CBPOne App, unaccompanied children, lawful permanent residents, and individuals with a valid visa.

4 For nearly two decades prior, CBP policy was to affirmatively ask if a person was afraid of returning to their home country. CBP data indicates that the percentage of migrants referred for CFIs/RFIs fell nearly 75% in July 2024 Migrants who do not “manifest” fear will be removed through an expedited removal order (i.e., the same kind of order that is issued to a migrant who receives a negative decision at their CFI/RFI). Migrants can “manifest” fear at any time up until their removal.

5 The practical implications are unclear beyond the mere fact that is a higher standard of review at both the CFI/RFI and during merits adjudications. Previously, the burden was definitively higher during merits adjudications.

NAI-1541171367v4

Jones Day

HOW TO ACCESS AN OVER-THE-PHONE INTERPRETER

1. DIAL: 1-844-765-5840

3. INDICATE: the language you need

3. PROVIDE: your 12-digit CAM #

Document the interpreter language and ID number for your reference. Brief the interpreter and give any special instructions.

When dialing out to a client, call the interpreter first, brief them and let them know if you want them to leave a voicemail, then dial out to the client yourself.

Amharic

Arabic

Armenian

Bengali

Bosnian

Ja govorim bosanski

Bulgarian

Burmese

Cambodian

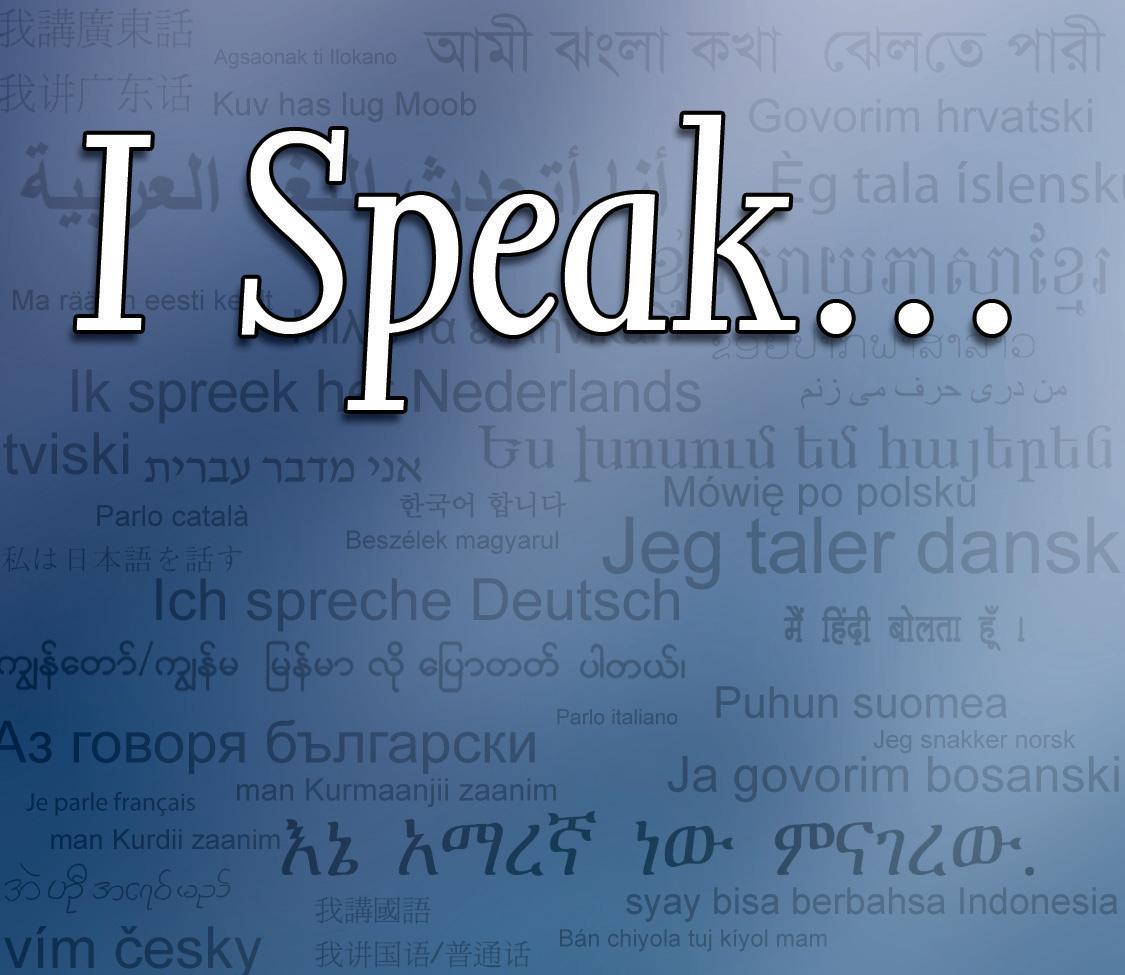

Language Identification Guide

Cantonese (Traditional) ( im li ed)

Catalan

Parlo català

Croatian Govorim hrvatski

Czech Mluvím esky

Danish Jeg taler dansk

Dari

Dutch

Ik spreek het Nederlands E

Estonian

Ma raagin eesti keelt F

Finnish

Puhun suomea

French

Je parle français

G

German

Ich spreche Deutsch

Greek

Icelandic Ég tala íslensku

Ilocano

Agsaonak ti Ilokano

Indonesian saya bisa berbahasa Indonesia

Italian Parlo italiano

Japanese

Kackchiquel

Quinchagüick áchábalruinrí

Korean

Kurdish man Kurdii zaanim

Kurmanci man Kurmaanjii zaanim

Laotian

Latvian Es runâju latviski

Lithuanian Að kalbu lietuviškai

Bán chiyola tuj kíyol mam

Qanjobal

Ayin tí chí wal q anjob al

Quiche

In kinch´aw k´uin ch´e quiche

Romanian

Serbian

ign Language

Slovak

Hovorím po slovensky

Slovenian

Govorim slovensko

Somali

Waxaan ku hadlaa af-Soomaali

Mandarin (Traditional) ( impli ed)

Mon

Norwegian Jeg snakker norsk

Persian

Polish

Mówi po polsku

Portuguese

Eu falo português do Brasil (for Brazil)

Eu falo português de Portugal (for Portugal)

Punjabi

Spanish Yo hablo español

Swahili

Ninaongea Kiswahili

Swedish Jag talar svenska

Tagalog

Marunong akong mag-Tagalog

Tamil

Thai

Turkish

Ukrainian Urdu

Vietnamese

Welsh Dwi’n siarad

Gujarati H

Haitian Creole

M pale kreyòl ayisyen

Hebrew

Hindi

Hmong

Kuv has lug Moob

Hungarian Beszélek magyarul

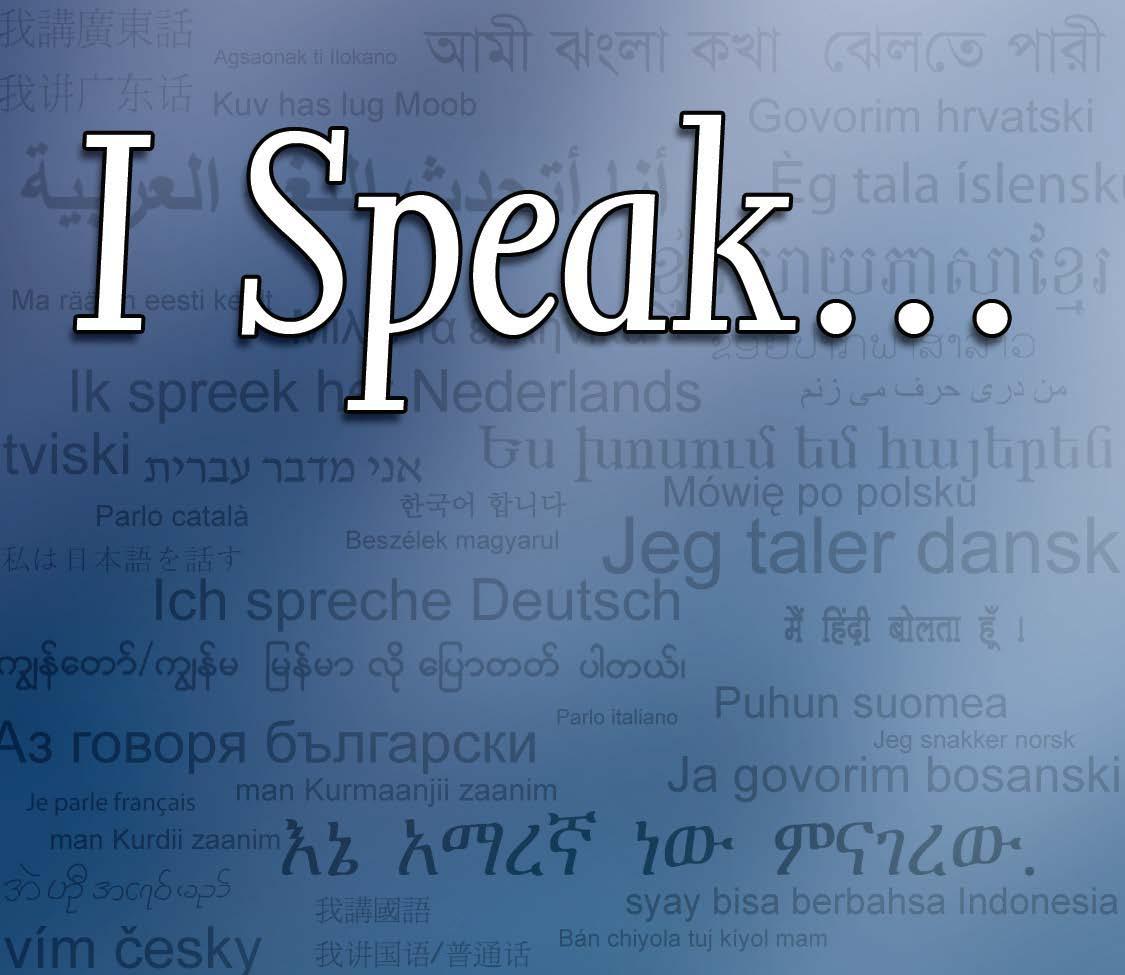

I Speak is provided by the Department of Homeland Security Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties (CRCL). Other resources at www.lep.gov

Contact the DHS Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties’ CRCL Institute at CRCLTraining@dhs.gov for digital copies of this poster or a “I Speak” booklet.

Download copies of the DHS LEP plan and guidance to recipients of financial assistance at www.dhs.gov/crcl

Xhosa

Ndithetha isiXhosa

Yiddish

Yoruba Mo nso Yooba

ulu

Ngiyasikhuluma isiZulu

IndigenousLanguageIdentificationPoster

¿Habla?

¿Habla K’iche? (Guatemala)

¿Habla Mam? (Guatemala)

¿Habla Awateko? (Guatemala)

¿Habla Q’eqchi? (Guatemala)

¿Habla Kakchikel? (Guatemala)

¿Habla PocoMam? (Guatemala)

¿Habla Q’anjob’al? (Guatemala)

¿Habla Achi? (Guatemala)

¿Habla Ixil? (Guatemala)

¿Habla Pocomchi? (Guatemala)

¿Habla Jakalteko (Popti)? (Guatemala)

¿Habla Chuj? (Guatemala)

¿Habla Akateko (Acateko)? (Guatemala)

¿Habla Garifuna?

(Honduras, Guatemala, Other)

¿Habla Cora? (Mexico)

¿Habla Zapotec? (Mexico)

¿Habla Chatino? (Mexico)

¿Habla Tepehuan? (Mexico)

¿Habla Quechua? (Peru, Ecuador, Others)

ThisposterassistsDHSpersonnelinidentifyingtheprimarylanguageofanindividualfromCentralor SouthAmericawhoisnotproficientinEnglishorSpanish. Thisposterisintendedtobeusedwithorin additiontoComponentprotocolsforidentifyingindigenouslanguagespeakers.

ISpeak

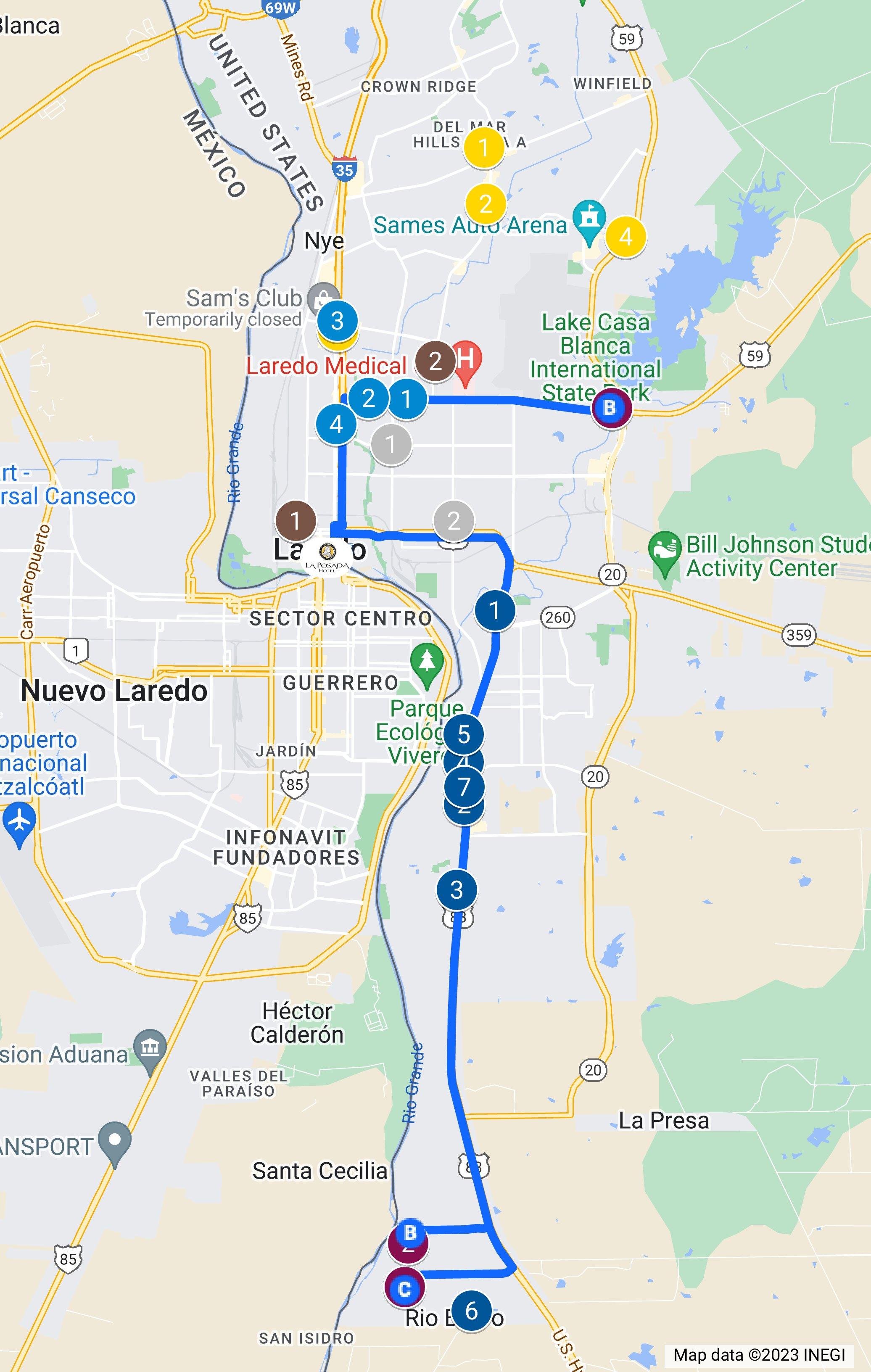

Laredo OTG Map (bp.legal/OTGMap)

Hotel/Office

La Posada Hotel

Jones Day Laredo

Detention Centers

Laredo Processing Center

Rio Grande Detention Center

Webb County Detention Center

Directions to LPC

Jones Day Laredo

Laredo Processing Center

Directions to Rio or Webb

Jones Day Laredo

Rio Grande Detention Center

Webb County Detention Center, US-83, Laredo, TX

Lunch near LPC

Bolillo's Cafe

Obregon's

Tacolare

Taquitos Ravi

Lunch near Rio/Webb

Hacienda Arandas

Paulita's

El Pollo Feliz

Taco Palenque

El Taco Tote

Taqueria Ke'Chilango

Whataburger

Dinner

Border Foundry

Lolitas Bistro

Palenque Grill

Tabernilla

Coffee

Café Radical 956

Organic Man Coffee Trike

Pharmacy

Walgreens

H-E-B (South)

Walgreens (South)