AND

KASHRUT

JACOBS CENTER

AND

KASHRUT

OU DIRECTOR OF ANGLO ENGAGEMENT

DIRECTOR, OU KOSHER ISRAEL DEPARTMENT

DIRECTOR, THE GUSTAVE AND CAROL JACOBS CENTER FOR KASHRUT EDUCATION/ DEPUTY RABBINIC DIRECTOR OU KOSHER ISRAEL DEPARTMENT

OU ISRAEL GUIDE TO PESACH

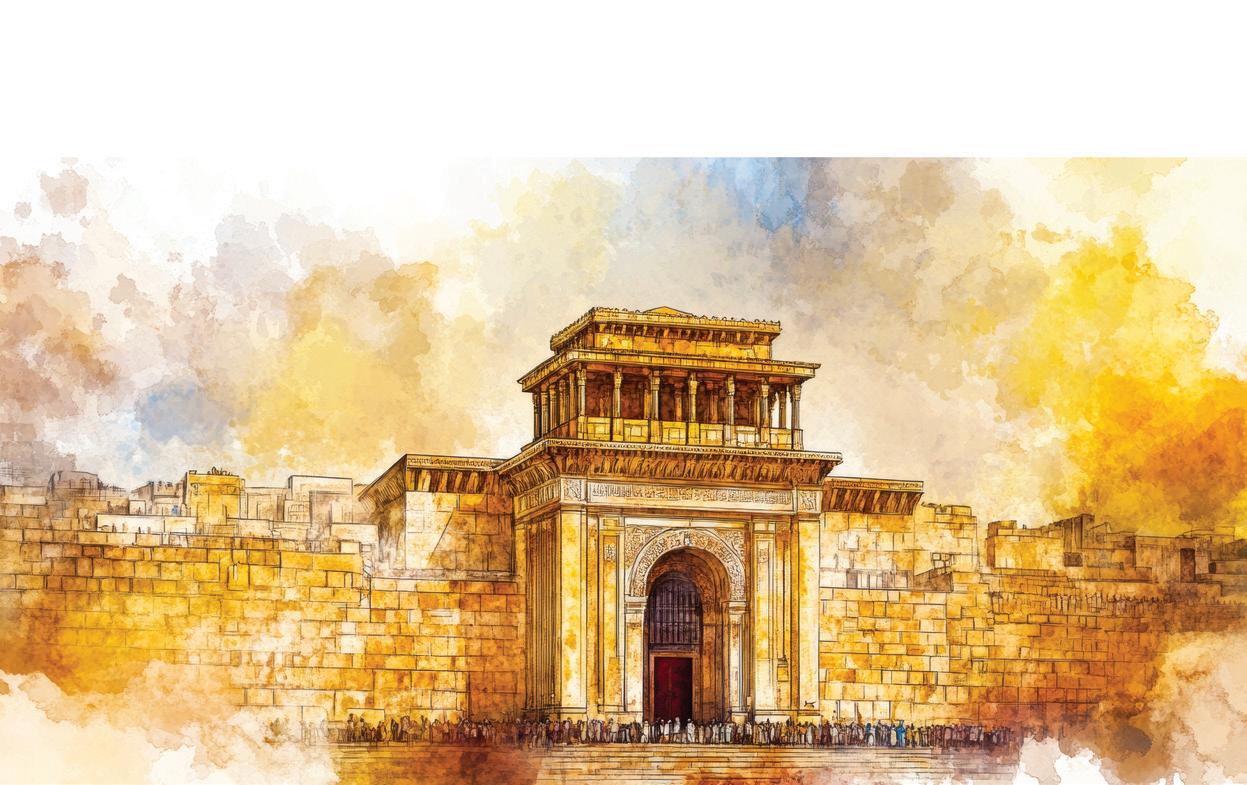

The central mitzvah of the Passover holiday, after which the festival is named, is the korban Pesach--the Paschal sacrifice. Brought during Temple times, the korban is both an individual offering, which every Jew is obligated to participate in, as well as a communal offering (bekinufya), i.e., it is offered individually by the entire community together. This dual nature is symbolic to the essence of the Yom Tov.

Pesach is the time of our redemption. An individual Jew by himself is not guaranteed redemption, for the promise of redemption belongs only to Klal Yisrael as a whole, which will inevitably be redeemed. Hence, each individual’s redemption depends on his participation in the community; if he is part of the community, he too merits salvation and redemption.

This may explain, as well, the reason the korban Pesach is eaten in a chaburah (group)—a requirement not found regarding other sacrifices. It may be precisely so that individuals join together in fulfilling the requirement to bring the korban Pesach. Because the korban Pesach has a communal dimension, it is not fitting that one person alone bring it as a purely private offering.

The korban Pesach thus represents the redemptive power of the Jewish people standing together in unity. By joining together, individuals attach themselves to the redemption that is promised to the nation as a whole.

The OU is an organization through which the efforts of its devoted individual staff members contribute to the strength of the entire community. This year, once again, OU Kosher presents our widely-read Passover Guide, just one example of the herculean efforts of our dedicated staff to not just administer and supervise tens of thousands of factories around the globe, but also to provide resources and information for kosher consumers and enable the proper observance of Passover throughout Klal Yisrael. Wishing all a chag kasher vesame’ach, and next year in Jerusalem!

Rabbi Menachem Genack CEO OU Kosher

The holiday of Pesach represents the birth of the Jewish nation. Most Jewish holidays include food as a component, however the special kosher for Pesach foods are at the very center of this Yom Tov celebration. This signals the fundamental place that kashrut plays in the establishment, preservation and advancement of our people.

In one of the final dialogues that Pharaoh shares with Moshe, and following seven difficult plagues, the Egyptian monarch finally accedes to the demand that he permit the children of Israel to worship its Creator in the desert. “Who from amongst you are those that you will take with you on this pilgrimage,” asks Pharaoh.

Moshe responds: ““With our youth and with our elders we will go, with our sons and with our daughters, for it is a holiday of Hashem for us.” Jewish holidays are inclusive family events, nowhere more pronounced than at the Pesach Seder. For all our internal differences as a people, kosher food can be a great unifier. It can bring us together and bridge the ideological, partisan and generational divisions that sometimes separate us.

Even after one hundred years, OU Kosher remains the global leader in kosher certification. While this is clearly the case in a quantitative matrix - qualitatively OU is also at the forefront as the cutting-edge leader of the world of kashrut. With more than fifty rabbinic coordinators in our NY headquarters and many hundreds of rabbinic field representatives around the world, our vast collective experience and expertise help us to serve not just as the purveyor of kosher certified products worldwide, but also the ultimate resource to the entire world of kosher.

We thank you for the trust that you have placed in OU Kosher and look forward to continuing serving all of Klal Yisrael in providing it the highest levels of kashrus that are both reliable and reasonable.

Chag Kasher v’Sameach

Rabbi Moshe Elefant

COO OU Kosher

Welcome Everyone,

As I write this letter, we are still grappling with the immediate aftermath of October 7th. So many of our loved ones are fighting for the safety of Jews in Israel and around the world.

While baruch Hashem many of our brothers and sisters that were taken hostage by our enemies have been returned, way too many are still preparing for the festival of freedom in captivity. We daven from the depths of our hearts for all of the hostages to return, and bezrat Hashem by the time you read this they will be home. We daven from the depths of our hearts that those injured, displaced from their homes and suffering in other ways from this war be blessed with freedom from their suffering. We pray for geulah on a personal level and on a national level for Am Yisrael. We also thank Hashem for all of the hidden and obvious miracles the Jewish people are experiencing every single day.

Many of you reading this Pesach Guide live in Israel and many of you are visiting. Whichever group you are a part of, I want to take this opportunity to say thank you. Thank you to those of you who are serving and who sent your spouses or children to serve in the IDF. Thank you for all of the volunteering and checking in on your relatives and friends. Thank you to everyone who intensified your Torah learning and tefilot for the success of Am Yisrael this year. Thank you for coming this Pesach in a show of solidarity standing up for the Jewish people. “B’chol dor v’dor omdim aleinu le’chalotanu v’HaKadosh Baruch Hu matzilenu mi’yadam,” in every generation there are enemies that arise to destroy us, but Hashem saves us from their hands.

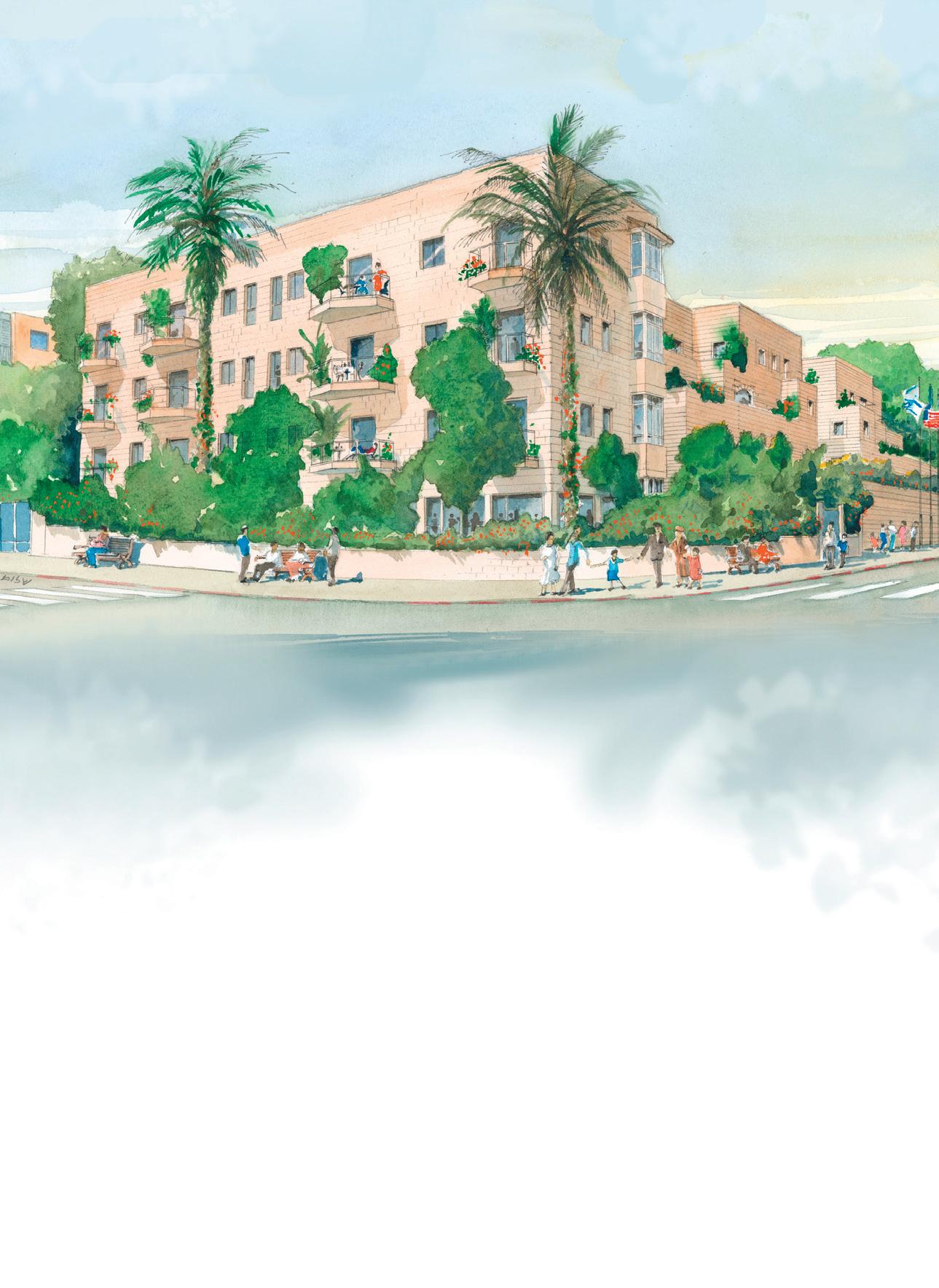

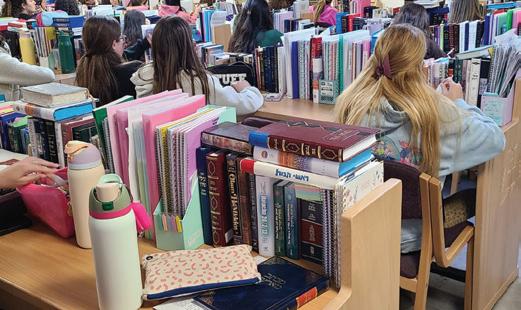

This Pesach Guide was published due to the tremendous efforts of Rabbi Ezra Friedman and Rabbi Yissachar Dov Krakowski who run OU Kashrut here in Israel. We are pleased to once again be presenting this guide in response to the many requests we’ve received to provide a guide that will instruct people on how to overcome the challenges they encounter here in Israel in keeping the level of kashrut that they are accustomed to and desire. This guide is one of the many initiatives of OU Israel’s Gustave & Carol Jacobs Center for Kashrut Education which helps people better understand and keep kosher in Israel. Other resources include kashrut shiurim, articles in Torah Tidbits, educational videos, a hotline and more.

OU in Israel provides programs for the English-speaking population all across the country—including shiuirm, holiday programing, tiyulim, Torah Tidbits, NCSY, Yachad, and JLIC—as well as the work we are doing with 10,000 at-risk from Kiryat Shmona in the north to Dimona in the south. I hope you get a chance to see the incredible impact that the OU is having here both on a program level and a kashrut level.

We at OU Israel wish all of you an uplifting and incredible Pesach. May this month Nissan usher in the geulah sheleima

Chag kasher ve’sameach!

Rabbi Avi Berman

Each week, we add 10+ high caliber shiurim to our OU Israel Shiurim YouTube and Instagram pages. Search OU Israel Shiurim to learn Torat Eretz Yisrael anytime from anywhere.

The Gustave and Carol Jacobs Center for Kashrut Education was established in the fall of 2019, in loving memory of Gustave and Carol Jacobs z”l, by their loving children Aviva and Joseph Hoch, and Judy and Mark Frankel. Gustave and Carol were active lay leaders of the Orthodox Union and numerous other Jewish organizations for many decades. Working with the OU, they became pioneers of kashrut in North America, ensuring that for generations to come Jews in America, and subsequently around the world, would have easy access to quality kosher food. The goal of the Gustave and Carol Jacobs Center for Kashrut Education is to help English-speaking olim and tourists understand the complexities of

kashrut in Israel. Directed by Rabbi Ezra Friedman a close disciple of Rav Zalman Nechemia Goldberg, and Rav Emeritus of the Musar Avicha Shul in Maale Adumim, the Gustave and Carol Jacobs Center for Kashrut Education educates tens of thousands of people weekly about kashrut observance through:

Shiurim all over Israel engaging videos weekly column in the Torah

Tidbits leaflet

kashrut guides

kashrut hotline Kashrut hotline

(including over 16 WhatsApp groups!) workshops

other educational initiatives

In addition to the Gustave and

Carol Jacobs Center for Kashrut Education, the OU has a very active Kosher Israel Division. Our 180 kosher-certified companies in Israel include Osem, Strauss-Elite, Tenuva, and many more. We have numerous mashgichim providing guidance and service for factories, hotels, and restaurants. Current initiatives include partnership with the Army Chief Rabbinate, a large kashrut portfolio with Israeli importers and expanding our certification into the Israeli local market. All this is done in close coordination with global OU Kashrut. We are here to provide our communities with kashrut education, in addition to the highest standards of kosher food. We take great pride in our work with educational institutions and communities.

We are here to provide our communities with kashrut education, in addition to the highest standards of kosher food. We take great pride in our work with educational institutions and communities.

INTERESTED IN LEARNING MORE?

We are happy to arrange shiurim and hands-on workshops for yeshivot, seminaries, kollelim, schools, and shuls.

We can be contacted here in Israel at 02-560-9122 or efriedman@ouisrael.org.

Among Passover’s different names, the moniker Zman Cheiruteinu, the Time of Our Freedom, seems paradoxical, considering the extensive energy, planning and physical work invested in preparing for the holiday. And yet, these incredible efforts help us to truly appreciate what it means to be free; when we finally sit down for the first Seder with family and friends after cleaning, cooking, toiveling, and running errands, we can at last enjoy the fruits of our labor to their fullest.

The following overview serves as a handy refresher about the mitzvot and customs related to Pesach. For any questions about Pesach observance, please consult an Orthodox rabbi.

When is Passover this year, and when is the latest I can eat chametz?

Passover takes place from the 15th through the 21st of the Hebrew month of Nisan.

This year, Pesach 2025 falls on Motzei Shabbat, Saturday night, April 12, and lasts through Saturday, April 19.

It is forbidden to eat chametz as of Shabbat morning, April 12.

See page 4 for the corresponding zmanim (times).

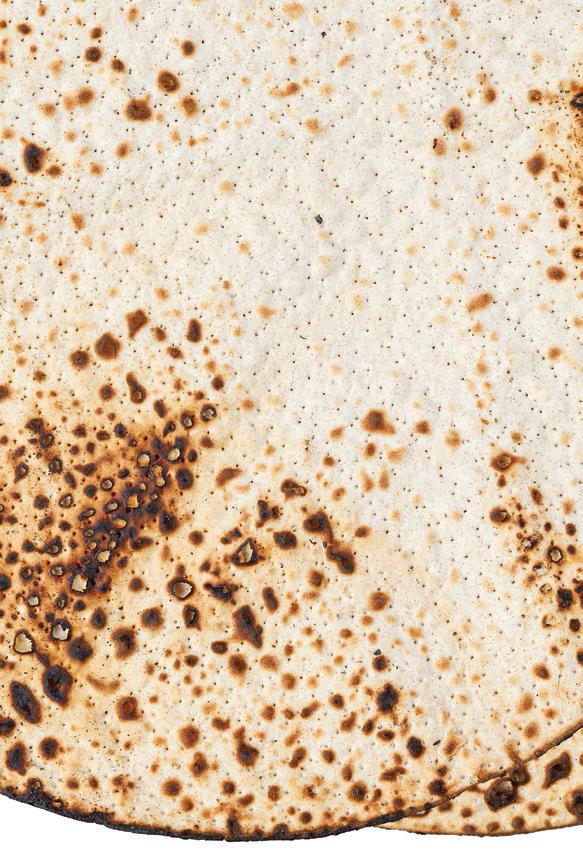

What exactly is chametz?

Chametz, often referred to as “leaven,” is any food created by allowing grain (specifically wheat, oat, spelt, rye or barley) and water to ferment and rise. Common examples of chametz include bread, crackers, cookies, pretzels and pasta.

Even foods with minute amounts of chametz ingredients, or foods processed with utensils or machinery that are used for chametz, are not permissible for Pesach use. Practically speaking, any processed food not certified as kosher for Passover may include chametz ingredients and should not be eaten on Pesach.

Is my home kosher for Passover?

Keeping a year-round kosher home is not the same as a “kosher for Passover” home.

On Passover, eating chametz, or having chametz in your possession, is forbidden. This mitzvah takes up the bulk of our Pesach preparations, as we clean and search our homes, cars and offices to remove all remnants of edible chametz

Before Pesach, it is customary to give Maot Chitim (literally, money for wheat) to the needy to help them to purchase matzot and other food for Pesach. OU’s Maot Chitim campaign efforts enable families affected by poverty to celebrate the holiday with dignity. Visit ou.org/passover-donate to participate in this meaningful mitzvah.

One’s entire home and car (and office, if you do not sell your chametz there) must be cleaned of all edible chametz. Check and clean out any place that may have come into contact with chametz during the year. (If you have kids at home, this might mean under beds and in closets, and in knapsacks.) Either clean all toys or set aside designated clean toys.

Rather than disposing of all of one’s chametz, it is customary to sell it to a non-Jew. Place chametz in a specially marked and sealed place, e.g.: a room or closet. That storage space can then be leased to a non-Jew for the duration of the holiday. Ask your Orthodox rabbi to help you arrange this. For guidelines on what can and should be sold, as well as tips for those whose custom is to not sell chametz, see page 36.

Year-round cooking and eating utensils should not be used, and separate utensils should be purchased exclusively for Pesach use. (In some cases, year-round utensils may be kashered for Pesach, in consultation with a rabbi.)

Ta’anit Bechorot - The Fast of the Firstborns

This year, Thursday, April 10, is a fast day for firstborn males. During the tenth plague, all the firstborns males in Egypt died. G-d passed over the homes of the Jews and spared their firstborns. To commemorate this, firstborns fast on Erev Pesach.

Many congregations conduct a siyum. (The conclusion of a portion of Torah learning is a celebratory occasion that allows for a seudat mitzvah, a ritual feast). A siyum exempts firstborn males from fasting altogether.

Bedikat Chametz – the search for chametz

Using a candle or flashlight, we inspect our homes for any chametz that we might have overlooked. This year, Bedikat Chametz will take place on Thursday evening, April 10, after dark. Kol chamirah should be recited. Any chametz found should be set aside to be burned the next morning and the chametz that one plans to eat on Shabbat is also set aside.

Biur Chametz - burning the chametz

Most years, we burn the chametz on the morning of Erev Pesach. Since Erev Pesach falls on Shabbat this year, we will burn the chametz on the morning of Friday, April 11. Kol chamirah is not recited and rather will be said on Shabbat Morning.

Have you combed through every inch of your home for chametz, covered what may seem like every inch of your kitchen with aluminum foil, and searched every corner? You’re ready for the next step: Not all the days of Passover are the same or have the same laws.

The first day and last day of Pesach.

The first day (sundown, Saturday night April 12th through nightfall Sunday April 13 th ) and the last day (sundown, Friday night April 18 th through nightfall Saturday night, April 19 th ) are observed with Shabbat restrictions on work and creative activity.

The intermediate days of Pesach (Monday night, April 14 – Friday, April 18) are considered “semi-festive.” Although they are the “weekdays” of the holiday, not all work, activities and crafts are permitted. The laws of Chol Hamoed are nuanced. An Orthodox rabbi will be able to give you detailed guidance. For more on the laws of Chol Hamoed, please visit oukosher.org/ cholhamoed

The Mitzvot of the Seder

There are two Torah obligations and five rabbinical obligations to perform during the Seder.

Torah-based Mitzvot:

1. Relating the story of the Exodus (Maggid—reading from the Haggadah).

2. Eating matzah.

The Seder Plate

The Seder plate is arranged with symbolic foods that follow the order of the Haggadah. The prepared plate is placed in front of the leader of the Seder, who gives out the various foods to each participant.

What do we put on the Seder plate?

Charoset: a mixture of apples, nuts, wine, and cinnamon, symbolizing the bricks and mortar of ancient Egypt

Karpas: a vegetable (customarily parsley, radish, potato, or celery)

Maror: bitter herbs (may consist of romaine lettuce, endives, or pure horseradish)

Beitzah: a roasted egg

Zeroa: a piece of roasted or meat or poultry. There should be a kezayit of meat on the bone

Salt water: Place a bowl of salt water for dipping the karpas near the Seder plate.

Matzah

Three whole matzot are placed next to the Seder plate. We are commanded to eat matzah three times during the Seder:

1. At the start of the Seder meal (with a special bracha)

2. For korech (Hillel sandwich) together with the maror

3. For the afikomen (at the end of the meal)

Rabbinical Mitzvot:

1. Arbah Kosot: Drinking four cups of wine.

2. Maror: Eating bitter herbs.

3. Hallel: Reciting psalms of praise.

4. Afikoman: Eating an extra piece of matzah for dessert as a reminder of the Pesach offering.

5. Demonstrating acts of freedom like sitting with a pillow and leaning to the left when eating matzah and drinking wine.

Maror — Bitter herbs

Everyone is obligated to eat bitter herbs twice at each Seder:

1. A kezayit of maror, dipped in charoset

2. A second amount inside the matzah sandwich (korech)

Maror must be raw and unpreserved. Therefore, commercially prepared grated horseradish, which is packed in vinegar, may not be used for the mitzvah. For details on the specific amounts and requirements see “Sizing Up the Seder” on page 18.

This year, one should prepare ground maror before Shabbat and keep it in a sealed jar until the Seder to preserve the strength of the maror. If one is using romaine lettuce, it should be checked and dried before Shabbat. If it was not done before Shabbat, please see “When Shabbat is Erev Pesach” on page 20.

Telling the story of the Exodus and singing Hallel

We encourage young children to participate in the Seder to the best of their abilities. It is customary for the youngest person at the Seder to ask Ma Nishtana, the Four Questions.

We close the Seder with Hallel, which praises G-d and His special relationship with the people of Israel. The Seder traditionally concludes with singing (and dancing to) several lively songs that celebrate our treasured relationship with G-d.

All dietary laws and restrictions remain in effect until nightfall after the eighth day of Pesach.

Chametz that was properly sold may only be eaten once the resale is confirmed by your rabbi (agent). Chametz that was in the possession of a Jew during Pesach is forbidden for consumption by any Jew, even after Pesach.

u Torah Initiatives

Hundreds of inspirational Shiurim by world renowned Torah personalities in over a dozen locations

u Women’s Division

u The Bais in memory of Mrs. Charlotte Brachfeld a”hEvening Beit Midrash program for Men

u Gustave & Carol Jacobs Center for Kashrut Education

u Torah Tidbits is the largest week ly English language Torah publication in Israel

For 45 years, OU Israel has helped ensure English-speaking olim and visitors acclimate to Israeli society, feel at home and contribute to the State of Israel.

u Mother-Daughter holiday & Bat Mitzvah programs

u NCSY Israel for English-speak ing teens

u Yachad Israel for families with children who have special needs

u Camp Dror for campers entering 5th-11th grades

u ATID for lone olot in their 20s

u NextGen for young women (single & married) in their 20s-40s

u Young Professionals net work for single olim

u JLIC builds vibrant communities for students & young olim across 10 cities

u Leil Yom HaA ztmaut musical Tefila

u Yom Yerushalayim musical Shacharit

u Community Torah Summits

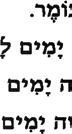

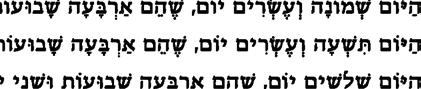

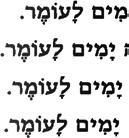

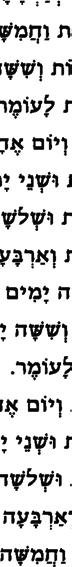

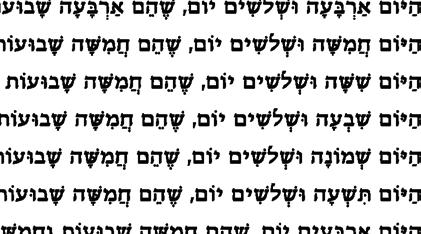

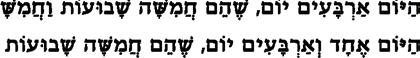

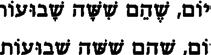

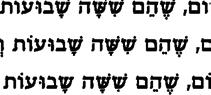

TALMUDIC MEASURE OF VOLUME

RAV CHAIM NOEH

RAV MOSHE FEINSTEIN

CHAZON ISH

K’ZAYIT

29 CUBIC CM (1 FL. OZ.)

43.2 CC (1.5 FL. OZ.)

50 CC (1.7 FL. OZ.)

K’ZAYIT 19.3 CC (.7 FL. OZ.) 32 CC (1.1 FL. OZ.) 33.3 CC (1.1 FL. OZ.)

RIVI’IT**

3 FLUID OUNCES

3.3 FLUID OUNCES

5.07 FLUID OUNCES

* These measurements are approximate amounts since matzot vary in thickness. Handmade matzot can be considerably thicker than machine-made matzot, or vice versa

** For the first three cups, one must drink more than half the rivi’it. One should drink the entire fourth cup so as to be able to recite a bracha achrona

(1 oz. by weight)

(Leaves: 1 oz. by weight)

IF GROUND HORSERADISH:

volume of 1.1 oz./32 grams.If this is difficult one can use .7 oz./19 grams.

IF ROMAINE STALKS

(.75 oz. by weight)

Enough to fill 3” x 5” area

KORECH 4” X 7” (.64 oz. by weight)

By Rabbi Moshe Zywica

This year, erev Pesach falls on Shabbat.

No need to panic. With proper planning, you’ll have the opportunity to come to the Seder well rested, relaxed, and to fulfill the mitzvot of the evening with more feeling and greater enthusiasm. Here are some of the important things to know about the day.

It is permitted to eat chametz Shabbat Morning until the proper halachic time noted on page 4, yet we still burn the chametz searched for on Thursday evening (April 10) early on Friday morning (April 11). This is done to avoid confusion in years when erev Pesach does not fall on Shabbat. Yet, Kol Chamira (a statement of nullification of chametz in our possession), which is normally said while actually burning the chametz, is not said on Friday, but rather on Shabbat morning (April 12) before the end of the fifth halachic hour of the day. (For your local time, see Halachic Times for Pesach on page 4).

Remember, not all chametz will be burned on Friday morning. We will need, and are allowed to consume, chametz (challah) on Shabbat.

Other erev Pesach restrictions, such as omitting Mizmor l’Todah and Laminatzai’ach from shacharit; refraining from doing laundry and taking haircuts after chatzot (midday); and koshering pots and pans after chatzot are all still allowed since Friday is not erev Pesach.

This year the custom is for firstborn males to fast on Thursday. We move the fast from Friday to Thursday to avoid starting Shabbat while fasting. Bedikat Chametz (the search for chametz), as mentioned above, is performed Thursday evening with a beracha. If it is too difficult to fast until after Bedikat Chametz, it is permissible to snack before beginning the bedikah.

As in any other year, firstborn males may participate in a siyum on Thursday, which would exempt them from fasting altogether. According to the Yalkut Yosef Moadim, (in the section on Taanit Bechorot 19), the rule for Sephardim is that this year a father is not required to

attend a siyum on behalf of his firstborn son if the son is still a minor.

It is preferable that Seder preparations (the shank bone, charoset, maror, roasted egg, saltwater and checking the romaine lettuce) be completed on Friday, since it is prohibited to prepare on Shabbat for the next day (hachana). Even a nap on Shabbat might be considered hachana if one verbalizes that it is being taken with the intention of remaining alert and awake for the Seder. While it would be permitted to prepare some Seder items on Saturday night, that would undoubtedly delay the start of the Seder. Since so much of the Seder focuses on

educating children and their experience of the Seder with their families, it is important to start the Seder as soon as possible before children fall asleep.

According to the Vilna Gaon, horseradish should be grated immediately before the Seder so that it will be sharp. Others say it should be grated before Shabbat and stored in a sealed jar to maintain the sharpness as much as possible.

If you forgot to prepare horseradish before Shabbat and would need to grate on yom tov, the grating should preferably be done with a shinui (deviation, such as grating on a paper towel or turning the grater upside down). Romaine lettuce that requires checking for infestation should be checked before Shabbat, since it is a process that shouldn’t be rushed. It is important to drain and/or dry the lettuce very well, since water might accumulate in the storage container, and any parts of the lettuce that soak in water for more than twenty-four hours may not be used for maror. If a person needs to check lettuce on yom tov, the thrip cloth method should be

avoided due to various halachic considerations regarding yom tov

If salt water was not prepared in advance, it can be made on yom tov, though some recommend using a shinui by putting the water in the vessel before the salt. If charoset needs to be prepared before the Seder, the fruit may be diced on yom tov, but the nuts should be ground with a shinui such as crushing in a bag. No deviation is needed when adding the wine.

The shank bone and egg roasted on yom tov offer a unique set of restrictions. If roasted on yom tov, they must be eaten on that day of yom tov; and, since we refrain from eating roasted meat or chicken at the Seder, the shank bone that was prepared Saturday night must then be eaten at the Sunday daytime meal. While the egg can be eaten at the seder. In general, we may not prepare food on the first day of yom tov if the intention is to consume it on the second day or after yom tov; therefore, all Seder foods should either be prepared before Shabbat or on each Seder night and consumed that night or, for the shank bone, at the following luncheon meal.

It is permitted and expected that challah and possibly chametz foods will be eaten both on Friday night and at the early start of the Shabbat day meal. Most will prepare kosher for Pesach foods and eat on Pesach dishware with the challah being the outstanding chametz

The challah should be cut and eaten over disposable napkins or paper towels to separate it from the Pesach food and dishes. It is recommended to wash your hands and rinse your mouth after eating the challah and commencing with the meal on Pesach dishes. Crumbs from the challah, dishes, table, or floor should be swept up and flushed down the toilet before the end of the fifth hour on Shabbat morning.

Remember to clean the broom of crumbs afterward. Sephardic communities traditionally recite haMotzi on water challah throughout the year, which can result in significant crumbs. Therefore, Sephardic poskim recommend using pita bread on Shabbat to avoid this issue.

Larger pieces of chametz may be broken into smaller pieces and flushed as well. Alternatively, large pieces of chametz may be placed in outdoor garbage pails, provided there is an eruv, but the chametz must be rendered inedible by pouring bleach or ammonia over the entire surface of the chametz. These fluids must be designated for that use before Shabbat. Otherwise, they would be muktzah.

It is permitted to brush your teeth with a dry toothbrush that was designated for Shabbat use to rid your mouth of chametz.

If you are hesitant to introduce challah into your kosher for Pesach home, you can use kosher for Pesach egg

matzah for lechem mishnah. Ordinarily, the bracha for egg matzah is Borei minei mezonot. However, Rav Moshe Feinstein, zt”l, writes (Igros Moshe) that if egg matzah is used for lechem mishnah for a Shabbat meal, the bracha is hamotzi

It’s important to eat at least a k’baitza (a little more than two ounces) of egg matzah, in addition to other foods that will be served at the meal, to substantiate the meal and justify the hamotzi. However, for Ashkenazim, the egg matzah—like challah—can only be eaten during the time frame that chametz can be consumed. According to the opinion of the Chazon Ovadia (Laws of Erev Pesach that falls on Shabbat, footnote 11), the rule for Sephardim is that you would be required to consume four baitzim (approximately six ounces) in order to say hamotzi However, due to the difficulty of this requirement, it is not recommended.

Now that we’ve covered the before, and most of the during, of this most unique Shabbat, how do we end it? Can we eat a proper seuda shelishit? If so, how?

Most Poskim say that seuda shelishit should be eaten throughout the year after midday, and some maintain that bread must be eaten at the meal.

Under normal circumstances, on a regular Shabbat, we can eat seuda shelishit on Shabbat afternoon following mincha using lechem mishnah bread, as we do at the other meals on Shabbat. That fulfills the mitzvah of Shabbat’s third meal in the best possible way – satisfying both requirements of eating bread and eating it after chatzot (midday). Alas, this is not possible when Shabbat occurs on erev Pesach when we; 1) are not permitted to eat chametz — bread or egg matzah beyond four hours into the day, and 2) cannot eat regular matzah at all the entire day.

To fulfill the requirement for the seuda shelishit meal this year, one should eat fish, meat, or cooked fruits and vegetables.

Since there are opinions that seuda shelishit can be fulfilled earlier in the day, many will also divide the morning meal into two parts. We can recite Kiddush and haMotzi, eat one course and then recite Birkat Hamazon. After a break of one-half hour, we can wash again, say haMotzi, eat the rest of the meal and then recite Birkat Hamazon. Once again being mindful that the challah or egg matzah that would be used for lechem mishnah is consumed before the fourth hour.

Sephardic customs provided by Rabbi Rachamim Churba, Rabbi of Homecrest Congregation.

If

you are hesitant to introduce challah into your kosher for Passover home, you can use kosher for Passover egg matzah for lechem mishnah. Ordinarily, the bracha for egg matzah is Borei minei mezonot. However, Rav Moshe Feinstein, zt”l, writes

(Igros Moshe) that if egg matzah is used for lechem mishnah for a Shabbat meal, the bracha is hamotzi.

By Rabbi Eli Gersten

The Haggadah’s final chapter, Nirtza, is comprised of a series of poems. Some are written in Aramaic and are enigmatic and mystical in nature. In the spirit of the Seder, I present four questions and answers that may help us to better understand this part of the Haggadah:

1What does Nirtza mean?

The word Nirtza means pleasing. In this context, we recite it as a prayer that Hashem will find our Seder service pleasing, which we emphasize in Nirtza’s opening paragraph, “Chasal Siddur Pesach K’hilchato”; We have completed the order of the Pesach according to its laws, and Hashem should therefore bless us with the ability to serve Him fully with our return from Exile.

2

How did Nirtza get its name?

In many early editions of the Haggadah, before “Chasal Siddur Pesach” there is a preceding statement: “Hashem will surely find your actions ‘pleasing’ if you have followed this order.” It seems that this statement was added as an explanation for the word Nirtza. The term Nirtza, pleasing, does not refer to the poetry within the chapter, rather, it refers to our wish that Hashem find all the chapters recited during the entire Seder pleasing.

3

What is Nirtza’s connection to the story of Yetziat Mitzrayim, and the main structure of the Haggadah?

The original text of the Haggadah ended with Hallel, and did not include the piyyutim of Nirtza. The Rambam, for example, ends his explanation of the Seder with Hallel and its accompanying cups of wine. However, the tradition has been to conclude the Haggadah with “Chasal Siddur Pesach” and other piyyutim, each according to their tradition. Commentators maintain that one should not change the piyyutim that one’s family customarily recites, for they are considered a minhag, which is binding. However, if one is not well, or has difficulty staying up beyond Hallel, one may go to sleep after Hallel. The Chasam Sofer’s wife would go to sleep after Hallel, and

certain communities today do not recite any piyyutim following it.

The opening paragraph of Nirtza, “Chasal Siddur Pesach”, was adapted from a piyyut written by Rav Yosef Tov Olam in the 11th century. The original piyyut was intended to be recited on Shabbat Hagadol. Its original meaning was that in the merit of having completed our preparations for the Seder, we should be able to fulfill all the mitzvot of Seder night.

Some commentators, including the Maharal MiPrague, believe that Nirtza is not an independent section of the Haggadah, since it does not seem to fulfill a specific obligation like the other chapters. They explain that Nirtza is a continuation of the praises of Hallel. According to this view, we can understand that the purpose of Nirtza’s poetry is to offer further praises to Hashem. The piyyutim, such as “Adir Bi’melucha” (Mighty in His Kingship), and “Adir Hu” (Mighty is He), which enumerate the praises of Hashem, clearly follow this approach.

However, other commentators, including the Chayei Adam, count Nirtza as a separate section which continues the fulfillment of the obligation to discuss Yetziat Mitzrayim the entire night until one is overtaken by sleep. This includes the recitation of Shir HaShirim (The Song of Songs), which is printed at the end of many Haggadahs. The piyyutim, such as “Vayehi B’chatzi Ha’lyla” (And it was at Midnight), “Zevach Pesach,” which recount the numerous times throughout the generations that Hashem has redeemed us, as well as Shir HaShirim, which speaks of our exile and redemption, seem to follow this approach.

The last two piyyutim commonly recited at the Seder are “Echad Mi Yodeya” and “Chad Gadya.” The Chida writes very harshly against those who might trivialize or disparage these piyyutim, which have inspired a multitude of interpretations from some of the greatest rabbis.

According to the Chida, one great Kabbalist wrote 10 mystical

explanations for “Chad Gadya.” The Vilna Gaon also wrote a famous interpretation of “Chad Gadya,” which traces Jewish history from the purchase of the birthright (symbolized by the goat) by our forefather Yaakov (the father), to our descent into Egypt (the dog), to our redemption via Moshe’s staff (the stick), until our ultimate redemption by Hashem.

4Why

does Nirtza officially mark the Seder’s end?

Nirtza should not be understood as the end of the Seder, but rather a transitional step. With the completion of Hallel, we have finished reading the scripted praises and narratives of the Haggadah. Now is our opportunity to offer our own insights into Yetziyas Mitzrayim, and to praise Hashem with songs, especially Shir HaShirim, for as long as we can, until we are overtaken by sleep.

May our service be found pleasing.

You packed bags for soldiers, you wrote your senators, you attended rallies, you picked vegetables, you davened...

Your vote for OIC-Mizrachi ensures that Torah values and observance and devotion to the State of Israel are given a strong voice in Israel’s powerful and influential National Institutions, inspiring connection, generating kiddush Hashem, and meaningfully impacting Israel and the Jewish world.

By Rabbi David Bistricer

Beyond the conventional methods of growing vegetables in an open field with soil, new technologies are enhancing the agricultural industry. For example, innovations have been designed to produce higher-quality products with greater consistency, and a longer shelf-life. While these advancements have created agricultural revolutions that are much to the consumers’ benefit, they also have their own set of kashrus implications. Here, we will explore the use of indoor-farmed lettuce, to fulfill the mitzvah of maror.

Over time, farms have incorporated new agricultural methods in line with technological advancements. Indoor farming, for example, has become an increasingly popular industry trend. This technique consists of growing plants

indoors in greenhouses, under controlled conditions. Greenhouses are enclosed, transparent structures typically constructed from glass or plastic. Their ability to absorb heat from the sun, while protecting plants from outside elements, has proven to yield more consistent and higherquality products year-round. Although greenhouses are becoming increasingly popular, they’ve existed in some form for centuries.

Indoor vertical farming is a much more recent innovation. This technique typically centers on the use of verticallystacked layers of trays found in both warehouses and greenhouses.

Indoor farming employs multiple technologies: Hydroponics involves growing plants using a water-based nutrient solution, often with an additional growing medium other than soil, such as peat moss or coconut coir, a fiber. Aeroponics is a method of growing plants by suspending roots in the air which are irrigated with a nutrient-dense mist.

Vegetables grown via hydroponics or aeroponics present an interesting question around the appropriate blessing (beracha rishonah) to recite prior to consumption. On one hand, vegetables typically fall into a category of something that is grown in the ground.

It seems, then, that the proper blessing on any vegetable should be borei pri ha’adamah

However, these vegetables are not grown in the ground, but rather through specialized technology with a water-based medium. Therefore, perhaps the proper blessing should be shehakol

This question has been discussed by contemporary halachic authorities, who take different positions on the issue. Some rule

There are numerous halachic authorities that permit using hydroponically grown lettuce for maror at the Passover seder. However, since there is an opinion that appears to suggest otherwise, Rav Yisroel Belsky zt”l maintained that it is proper to use conventionally grown lettuce from soil for the Passover seder.

Consumers should be aware that indoor-grown vegetables may still be exposed to insects, even under controlled conditions. There is OUP certified lettuce for Passover, but those packages that do not have certification should be washed and checked before use.

that the proper blessing should be borei pri ha’adamah 1. The simple reasoning is that the blessing is intended for all vegetables as part of one category and the growing medium should not be a factor. However, others disagree, and suggest that the proper blessing is shehakol 2. Hydroponically grown vegetables in this sense may be compared to mushrooms, which are also not grown in the ground and require a blessing of shehakol 3 . There are numerous halachic authorities that permit using hydroponically grown lettuce for maror at the Pesach seder.4 However, since there is an opinion that appears to suggest otherwise 5, Rav Yisroel Belsky zt”l maintained that it is proper to use conventionally grown lettuce from soil for the Pesach seder.

Romaine lettuce is commonly used for maror. Below are step–by-step recommendations on how to properly check romaine lettuce for insects. The basic instructions apply to any kind of romaine lettuce, no matter how it grows:

1. Cut off the lettuce base and separate the leaves from one another.

[1] Shut Shevet HaLevi 1:205) and Teshuvos VeHanhagos 2:149

[2] Chayei Adom (51:17) and Yechaveh

Da’as 6:12

[3] Tractate Berachos 40b

[4] Keren Orah Menachos (70a), Chazon Ish Kelaim 13:16, Mikraei Kodesh, Pesach 2:12, Halichos Shlomo (7:20), Ashrei Haish p. 408

[5] Nishmas Adom Hilchos Lulav 152

2. Soak the leaves in a solution of cold water and soap. The proper amount of soap has been added when some bubbles are observed in the water.

3. Agitate the lettuce leaves in the soapy solution.

4. Spread each leaf, taking care to expose all its curls and crevices. Using a heavy stream of water or sink hose, remove all foreign matter and soap from both sides of each leaf. Alternatively, a vegetable brush may be used on both sides of the leaf.

5. Leaves should be checked over a light box or against strong overhead lighting to verify that the washing procedure has been effective. Pay careful attention to the folds and crevices in the leaf where insects have been known to hold tightly through several washings.

Occasionally, worms may be found in burrows within the body of a leaf. Look for a narrow translucent burrow, speckled with black dots that break up the deep green color of the leaf. These burrows will often trap the worm within the leaf. To rid the leaf of these worms, carefully slit the bumpy part within the burrow with a sharp knife and remove the worm. It is important to note that many of these varieties feature curly leaves with many folds in which the insects tend to hide. It is therefore recommended that they be washed and checked with extreme caution.

An alternative method of checking lettuce that has become increasingly popular involves the use of a mesh cloth. The basic method consists of agitating and soaking leafy produce for a few minutes in cold water containing soap or vegetable wash, and draining the water through a mesh cloth placed between two large strainers. After draining the water, the mesh cloth is placed on a light box to inspect for any possible insects that were dislodged from the produce into the water.

By Rabbi Dov Schreier

After their exodus from Egypt, Am Yisrael enjoyed miraculous manna from heaven for 40 years in the desert. Today, when we celebrate Pesach away from home, we often have access to fresh, frozen, or shelf-stable kosher food of the highest standards, with unprecedented ease. Much planning, effort and logistical know-how on the part of kosher food manufacturers and consumers make that possible.

Airlines, trains and even hotels frequently accommodate travelers’ requests for pre-ordered kosher meals. These meals are often produced at great distances and shipped far in advance. This is often true regarding meals for those who, unfortunately, will need to be in the hospital over Pesach.

While consumers should be especially cautious year-round when ordering, heating, and consuming these prepared meals, extra precautions are necessary during Pesach.

In the kosher foodservice business, as the Chanukah holiday concludes, many turn their attention to preparing food for the other eight-day holiday in the spring -- Pesach. OU Kosher meals are prepared in dedicated warehouses under full-time Rabbinic supervision. Before preparing OU Kosher for Passover meals, facilities undergo koshering procedures. These entail a shutdown of the sites, and the cleaning and sterilizing of equipment by specially trained individuals.

Certain pieces of equipment (i.e. commercial fryers, sheet pans) that cannot be properly koshered, are substituted with dedicated Passover replacements. Following these procedures, the premises remain “Passover-dedicated” for a number of weeks, or even months. Manufacturers often choose a slow season, such as mid-winter, to produce Kosher for Passover food products. Oftentimes, these warehouses revert back to nonPassover foodservice well before the holiday.

Kosher for Passover prepared meals must be clearly distinguishable from the non-Passover fare. As with all packaged products, to avoid consumer confusion, the Kosher for Passover marking must be obvious to both the vendor and the final consumer. Whereas consumers decide which products to purchase for Pesach based on their recognition of products’ kosher for Passover status, in the case of prepared meals, it is often an airline, hospital or hotel middleman who purchases and provides the meal to you.

The consumer is therefore at the mercy of the middleman’s discretion. Accordingly, greater lead time and the ability to make specific requests as far in advance as possible increase the likelihood that a kosher for Passover meal will be obtained by the middleman. Remember that prepared meals (both regular and kosher for

Passover) are often stored in freezers and pulled randomly without much thought given to Pesach’s strict halachic guidelines.

Note that while the packaging of prepared kosher meals is intended to be tamper-proof, packages are not bulletproof. As such, if, during handling, a hot tray becomes punctured, the puncture can materially affect the meal’s kosher status. This is all-themore sensitive on Pesach, when the rules of nullification (bitul 1:60) do not apply.

Even with all of our good intentions and pre-planning, mistakes in obtaining kosher for Passover meals can happen. It’s always a good idea to anticipate this possibility and bring along provisions from home in the event that things do not go as planned.

By Rabbi Gavriel Price

Acommon method of relinquishing ownership of chametz is to sell it, typically through an agent (a rabbi) to a nonJew. The chametz remains in the house, in a closed-off area (e.g. a closet) that has been rented to its new owner. After Pesach, the rental period ends and the agent purchases the chametz back on behalf of the original owner.

This option is time-honored and halachically acceptable. Some, however, do not want to rely on such a sale for chametz that, on a Torah level, we are required to remove from our possession.

The Torah prohibition against owning chametz applies not only to obvious chametz such as bread, pretzels or cookies, but to any product that contains a chametz ingredient that constitutes a k’zayit within that product. Licorice, for example, which

contains a significant amount of flour in its dough, would not be sold according to this position but should, instead, be eaten before Pesach, burned, or otherwise destroyed. Such products are considered chametz gamur — “real” chametz.

If the food is only safek chametz (that is, there is some doubt as to whether it is chametz at all), it may be included in the sale even according to those individuals who avoid the sale of chametz gamur

The foods listed in the chart on page 39 are identified either as chametz gamur and, according to the stringent position, should not be included in a sale, or “not chametz gamur,” and may be included in a sale.

Many people who avoid selling chametz gamur nonetheless have a family custom to sell their whiskey.

The Torah prohibition against owning chametz applies not only to obvious chametz such as bread, pretzels or cookies, but to any product that contains a chametz ingredient that constitutes a k’zayit within that product.

Because of global variations in raw material sourcing, this chart ONLY APPLIES TO PRODUCTS MANUFACTURED IN THE USA

PRODUCT STATUS

Baker’s Yeast Not Chametz Gamur

Baking Powder Not Chametz Gamur

Baking Soda Not Chametz Gamur

Barley (Pearled) Not Chametz Gamur 1

Beer Chametz Gamur

Bourbon Chametz Gamur 2

Brewer’s Yeast Chametz Gamur

Cereals in which wheat, barley, oats, rye, or spelt are primary ingredients Chametz Gamur

Cereals in which wheat, barley, oats, rye, or spelt are secondary ingredients Chametz Gamur

Chocolate (provided there is no wafer or flour as an ingredient) Not Chametz Gamur

Corn Flakes Not Chametz Gamur 3

Cosmetics Not Chametz Gamur

Duck Sauce Not Chametz Gamur

Farfel Chametz Gamur

Flour Not Chametz Gamur 4

Flour, Whole Wheat Not Chametz Gamur 5

Flour, Bleached Not Chametz Gamur 6

Flour, Rye Not Chametz Gamur 7

Flour, Spelt Not Chametz Gamur 8

Flour (as an ingredient in processed food) Chametz Gamur 9

Gefilte Fish Chametz Gamur

Gluten Free Specialty Foods (when containing oats, oat flour, or wheat starch) Chametz Gamur

Ice Cream (with the exception of Cookies & Cream) Not Chametz Gamur

Ices Not Chametz Gamur

Ketchup Not Chametz Gamur

Licorice Chametz Gamur

Maltodextrin Not Chametz Gamur

Maltodextrin (non-GMO) Chametz Gamur 10

Matzah (not for Pesach) Chametz Gamur

Mayonnaise Not Chametz Gamur

Medications

(Capsules, Pills, Tablets) Not Chametz Gamur

Mouthwash Not Chametz Gamur

Mustard Not Chametz Gamur

Nutritional Yeast Not Chametz Gamur

Oats: Instant, Rolled Chametz Gamur

Oatmeal Chametz Gamur

PRODUCT STATUS

Onion Ring Snacks (when containing wheat as an ingredient) Chametz Gamur

Pasta Sauce Not Chametz Gamur

Popcorn Not Chametz Gamur

Potato Chips Not Chametz Gamur

Pickles Not Chametz Gamur

Probiotics Not Chametz Gamur

Rice Krispies Not Chametz Gamur 3

Rum Not Chametz Gamur

Salad Dressing Not Chametz Gamur

Scotch Chametz Gamur 2

Soy Sauce Chametz Gamur 11

Starch (also referred to as food starch) Not Chametz Gamur

Starch (non-GMO) Chametz Gamur 10

Tequila Not Chametz Gamur

Toothpaste Not Chametz Gamur

Vanilla Extract Not Chametz Gamur

Vinegar Not Chametz Gamur

Wheat Germ Not Chametz Gamur 12

Whip Toppings Not Chametz Gamur

1. The processing of pearled barley is mechanical and does not require the use of water.

2. Follow family custom.

3. Although malt in corn flakes and crispy rice products is present at more than one-sixtieth of the product, in standard packaging the malt is less than one k’zayit of the package.

4. Contemporary milling production consists of a tempering process that renders flour only safek chametz and flour can therefore be included in a sale.

5. Whole wheat flour has the status of standard flour and undergoes a process that renders it safek chametz.

6. Bleached flour has the same status as standard flour (the actual bleaching does not render flour chametz gamur)

7. Rye flour does not undergo the tempering process that renders standard flour safek chametz.

8. Spelt flour does not undergo the tempering process that renders standard flour safek chametz

9. Flour as an ingredient in processed food is typically exposed to some form of moisture and should be assumed to be chametz

10. Typically, non-GMO starch and starch derivatives (like maltodextrin) are sourced from Europe, and should be assumed to be chametz

11. Wheat is used in traditional soy sauce production.

12. Wheat germ is a byproduct of the milling process; see footnote 4.

By Deena Friedman

Hosting and making Pesach is a unique challenge because it does not allow for much advance preparation. Typically before a holiday we cook and freeze, often doubling our recipes, thereby taking the load off the immediate holiday preparation. While similar advance preparation can’t be done to the same extent for Pesach, there are ways to prepare for Pesach without a Pesach kitchen, that will help make the holiday a little bit easier.

As a busy mom with five kids who also hosts her extended family for Pesach, I began thinking of ways to prepare some dishes in advance of the kitchen turnover in order to make my Pesach preparation more manageable. Doing even a few things ahead of time and checking them off the list helped to put me at ease and feel that I could get it all done!

The first step to advance Pesach preparations before the kitchen is turned over, is to find the right spot

at which to work, such as a large island or kitchen table with enough space. Fully cover the workspace with a disposable tablecloth. This will be your kosher for Pesach workstation. To ensure that every inch of space is covered, use a large surface rather than a small spot. Making dishes that can be prepped in an aluminum tin or using other disposable items makes it possible to make a Pesach dish without any Pesach supplies.

The Following are two recipes I make annually and freeze before baking or cooking other dishes. As the holiday gets closer, I use the same techniques but kasher one of my ovens for Pesach and can make and freeze even more ahead of time. Even without a double oven, and even if your oven isn’t Pesach-ready, these dishes may be frozen in advance. Videos of these dishes being prepped are available on my Instagram account @fun.in.the.bc.

Blintz souffle is a delicious dairy delight that is semi-homemade and comes together in minutes. Premade

kosher for Pesach blintzes can be found in the frozen section of most kosher markets. Everything will be prepped in an aluminum 9x13 pan, using either disposable measuring cups or even a standard plastic cup, as measurements don’t have to be exact. A plastic spoon will work in place of a tablespoon.

Meatballs are the perfect family-friendly and Seder-friendly dish that I serve at just about every holiday. Prepping the meatballs in advance allows for a main dish to be checked off!

The most tedious part of making meatballs is preparing the meat and rolling it into balls. As the busy days before Pesach approach, rolling meatballs is the last thing I want to be doing! I therefore prepare the meatballs and freeze them raw, so they are ready to go into a supersimple sweet and sour sauce on the stove, once the kitchen is kashered.

Purchase kosher for Pesach chopped meat which can typically be found weeks in advance of Pesach.

2 boxes kosher for Pesach blintzes

1 cup sour cream

¼ cup sugar

¼ cup orange juice

4 eggs

2 tbsp oil

2 tsp vanilla

⅛ tsp salt

Use either disposable measuring cups or even a standard plastic cup, as measurements don’t have to be exact. A plastic spoon will work in place of a tablespoon.

Note: All ingredients must be kosher for Passover.

In an aluminum 9X13 tin, combine the sour cream, sugar, orange juice, eggs, oil, vanilla,and salt.

Add in 2 boxes frozen blintzes; I like to alternate a fruit blintz and cheese blintz. Push the blintzes down into the mixture and use a spoon to put some over the top.

Sprinkle sugar and cinnamon over the top. Cover tightly and label, “Needs to be baked” before freezing, as a reminder to bake this dish once your oven is kosher for Pesach! I At that point, thaw the blintz souffle, bring it to room temperature, and bake it at 350° for 45 minutes until puffed and golden.

1 pound kosher for Pesach chopped meat 1 cup kosher for Pesach breadcrumbs

In a disposable aluminum 9 x13 pan, on a completely covered surface, prepare the meat mixture. 1

1 onion, finely diced

Roll the meat mixture into balls and place them on a second disposable aluminum baking sheet. Put the meatballs into the freezer on the baking sheet. Once frozen, transfer them to a Ziploc bag. Once the stove is kashered, the meatballs can be cooked frozen directly in the sauce. I will even prepare the meatballs in the sauce and if not needed until the end of the chag, the meatballs can be frozen in the sauce and will still taste great once defrosted.

1 egg

Salt and garlic powder

2 jars marinara sauce 1 can cranberry sauce

Pour the marinara sauce into a pot and melt the cranberry sauce in it. Place frozen meatballs into the sauce and bring to a boil. Once boiling, lower heat to a simmer, cover the pot, and cook for an hour.

Making Pesach more manageable takes a little extra thought and organization but can help make Pesach a lot less overwhelming. Thinking outside the box and getting creative can ensure a holiday preparation that is doable and even enjoyable. Chag sameach!

By Rabbi Eli Gersten

One of the most daunting preparations we make for Pesach is kashering, a process to prepare chametz utensils for Pesach use. As with all areas of halachah, those who are unsure of how to apply the rules of kashering to their situation should consult an Orthodox rabbi.

The Torah (Bamidbar 31:23) requires kashering utensils acquired from a non-Jew, as they are presumed to have been used in non-kosher cooking (and will have absorbed non-kosher flavor). Since chametz on Pesach is also forbidden, the Talmud applies the laws of kashering to chametz as well. There are four basic methods of kashering. The prescribed method depends on the utensil and how it was used.

Kashering Involves High Heat!

Utensils used directly in the fire (e.g. BBQ grate), must be kashered by placing them into fire. This process has the effect of burning away any absorbed taste. To qualify as a complete libun, metal must be heated until it glows. A self-clean cycle of an oven (approx. 850°F) also qualifies as libun. There is no need to wait 24 hours before libun, though it is advised. There is no need to scrub the utensil before performing libun, since the fire will burn off residue, but some cleaning is advised.

Utensils that were used to cook nonkosher liquid can be kashered with hagalah (boiling in water). To prepare the utensil for hagalah, the utensil must be thoroughly cleaned. Only utensils that can be scrubbed clean should be kashered. Items that have

narrow cracks, crevices, deep scratches or other areas that cannot be cleaned, cannot be kashered for Pesach. The following, for example, cannot be kashered for Pesach: pots with rolled lips, bottles with narrow necks, filters, colanders, knives (or other utensils) where food can get trapped between the blade and handle. After cleaning, the utensils should then be left idle for 24 hours. To kasher, every part of the utensil must make contact with boiling water. This process can be done in parts. For example, a large spoon can be immersed into a pot of boiling water for 10 seconds, turned over and then the remainder immersed. When the utensil is removed from the boiling water, it should be rinsed off in cold water. While strictly speaking these utensils may be kashered in a clean non-Pesach pot that was not used for 24 hours, the minhag, however, is to kasher the pot first, by boiling water in the pot and discarding.

If the utensil only came in contact with hot liquid being poured on it (iruy), it can be kashered in the same manner. If the utensil came in contact with hot chametz solids, then one should kasher by pouring boiling water accompanied by an even melubenet, a heated stone. For example, if hot pasta fell into a sink, stones should be heated on the stove, and moved around the surface of the sink while boiling water is poured over them. In this way, the water will remain boiling on the surface of the sink. The stones may need to be reheated several times, since they cool down quickly. In all other aspects the process is identical to hagalah.

In certain cases, libun kal is sufficient. This can be accomplished by heating in an oven at 550° F for one hour. This method of kashering can be used in place of hagalah. It is also used when the need for libun is only an added stringency.

Ceramic, such as china, and enamel coated pots cannot be kashered. It is the custom of Ashkenazim not to kasher glass as well. Some poskim do not permit kashering plastic or other synthetic materials for Pesach; however, the opinion of the OU rabbanim is that it may be kashered, if there is a need. Ask your rabbi for guidance. Composite stone (e.g. quartz counters) which is made mostly of stone, but is held together with resin, can be kashered. As a rule, materials such as metal, wood, stone, natural rubber, and fabric can be kashered.

It is recommended that one not wait until erev yom tov to run the self-cleaning cycle to kasher an oven, as this is known to be hard on the oven and repairs may be required.

Some newer self-cleaning ovens employ Aqualift technology that cleans at low heat; they should be considered like nonself-cleaning ovens.

Please note that kashering may discolor oven racks and stovetop burners. If racks have rubber wheels, the wheels may melt. Replacement racks for Pesach should be ordered well in advance of the holiday.

Surface must be heated to a dry temperature of approximately 850°F (i.e. self-cleaning oven) or until it begins to glow.

Surface should be completely cleaned with hot water and unused for 24 hours.

Surface should be completely clean and dry.

The utensil should be completely submerged in a pot of boiling water.

Cold water should be poured over surface.

Surface should be completely cleaned with hot water and unused for 24 hours.

Surface should be completely clean and dry.

Boiling water should be poured directly over all surfaces followed by cold water poured over the entire surface.

Surface should be completely cleaned with hot water and unused for 24 hours.

Surface should be completely clean and dry.

Surface should be heated to a dry temperature of 550° F (i.e. oven) for a minimum of one hour.

GLOSSARY

LIBUN GAMUR - Burning

HAGALAH - Boiling

IRUY KLI RISHON - Poured Boiling Water

EVEN MELUBENET - Heated Stone

7

SELF-CLEANING OVENS

LIBUN (burning) Remove any visible food. Complete self-cleaning cycle with racks in place.

NON-SELF-CLEANING OVEN

LIBUN (burning) Clean all surfaces (walls, floor, doors and racks) thoroughly with a caustic cleanser (e.g. Easy Off). Pay special attention to thermostat, oven window, and edges of the oven chamber. Black discoloration that is flush with the metal need not be removed. Oven should not be used for 24 hours. Place racks in the oven and turn the oven to broil (highest heat) for 60 minutes. A broiler pan that comes in direct contact with food should not be used.

Note: The method of kashering described above is based on the ruling of Rav Aharon Kotler zt”l. However, Rav Moshe Feinstein zt”l ruled that the oven must either be kashered with a blow torch, or an insert should be placed in the oven. Consult your rabbi for guidance

1

REFRIGERATORS, FREEZERS, FOOD SHELVES & PANTRIES

CLEAN & COVER

These areas should be thoroughly cleaned, paying special attention to the edges where crumbs may get trapped. The surfaces should be lined with paper or plastic.

Note: Refrigerators and freezers will operate more efficiently if holes are poked in the lining to allow air flow.

2

DISHWASHERS

HAGALAH (boiling in water) Kashering of dishwashers is a complicated process and should only be done in consultation with a halachic authority.

8

WARMING DRAWERS LIBUN (burning) Typically warming drawers do not get to libun kal temperature. Therefore, unless one is experienced in kashering with a torch, warming drawers are not recommended for use on Pesach.

9

MICROWAVES

HAGALAH (boiling in water) (for those who kasher plastic) The microwave must be cleaned well and not used for 24 hours. Glass turntable should be removed and replaced with new kosher-for- Passover surface. A styrofoam cup should be filled with water and boiled in the microwave for 10 minutes. The cup should be refilled and moved to another spot and the process repeated for 10 more minutes. Cardboard or contact paper should be taped over the glass window pane for the duration of Pesach.

10

METAL TEA KETTLE HAGALAH (boiling in water)

The same treatment for pots applies here. Although it is uncommon for anything but water to be put into a tea kettle, nevertheless it must be kashered. Tea kettles often sit on the stove, and it is common for them to get spritzed with hot food.

11

ELECTRIC MIXER NOT RECOMMENDED

Because of the difficulty in cleaning out the housing of the mixer from fine particles of flour, one should not use their year-round mixer on Pesach. The mixer blades, though, can be cleaned and kashered with hagalah

STAINLESS STEEL SINK

IRUY (pouring boiling water)

Remove drain. [It is recommended that the drain be replaced. If this is difficult, it may be used if the drain has large holes that can be completely scrubbed clean]. It is preferable to kasher a sink by pouring boiling water in conjunction with an even melubenet (a heated stone). In lieu of kashering with a heated stone, some will place a rack on the bottom of the sink, or use a sink insert.

CERAMIC SINK

CANNOT BE KASHERED AND MUST BE COVERED

The sink should not be used with hot water for 24 hours. The sink should be completely clean and dry. The sink should be covered with layers of contact paper or foil; it is best to purchase a sink insert.

12

SILVERWARE, POTS & OTHER SMALL ITEMS

HAGALAH (boiling in water)

Rolled lips, seams or cracks that cannot be cleaned will require torching of those areas. Utensils should be immersed one at a time into a pot of boiling water that is on the fire. Water should be allowed to return to a boil before the next item is placed in the pot. The pot can be non-Passover, provided it is clean, has not been used for 24 hours, and water is first boiled in the pot and discarded. Larger items can be submerged in the water one part at a time. Utensils should then be rinsed in cold water.

13

KEURIG COFFEE MAKER

HAGALAH OR IRUY (pouring boiling water) (for those who kasher plastic) The coffee maker must be cleaned well and not used for 24 hours. Remove K-cup holder and perform hagalah or iruy on K-cup holder. Run a Kosher-for-Passover K-cup in the machine (this will kasher the top pin).

4

THE SINK FAUCET (including instant hot)

IRUY (pouring boiling water)

Detach any filters or nozzles.

5

STAINLESS STEEL, GRANITE, COMPOSITE STONE (E.G. QUARTZ) OR FORMICA

COUNTERTOPS

IRUY (pouring boiling water) OR COVERING

It is preferable to kasher a countertop by pouring boiling water in conjunction with an even melubenet There are different opinions as to whether formica (or plastic) countertops can be kashered for Pesach.

CERAMIC TILE COUNTERTOPS

CANNOT BE KASHERED & MUST BE COVERED

The counter should be covered with a waterresistant covering.

6

GAS STOVETOP

LIBUN (burning) & COVER The stovetop surface and grates should be cleaned well and not used for 24 hours.

The stovetop surface should be covered with foil. The stovetop grates can be replaced or they should be burned out in the oven at 550° F for one hour.

ELECTRIC STOVETOP

LIBUN (burning) & COVER The stovetop surface should be cleaned well and covered with foil. The burners should be turned on until they glow red.

GLASS STOVETOP

CANNOT BE KASHERED & MUST BE COVERED*

The stovetop surface should be cleaned well and not used for 24 hours.

During Pesach, pots should not be placed directly on the stove surface, but rather an aluminum (or other metal) disk should be placed directly under the pot.

*The entire glass top surface should not be covered as this might cause it to overheat and crack.

14

HOT WATER URN, WATER COOLER

IRUY (pouring boiling water)

Urn only used for heating water: Run hot water through the water tap for 10 seconds, while pouring boiling water from a kettle over the water tap. Urn also used to warm food (e.g. to warm challah): Not recommended. Must be put away for the holiday.

Water Cooler In addition to pouring boiling water over tap, replace water bottle.

15

BABY HIGH CHAIR

COVERED

The tray should be covered with contact paper. The seat, legs and bars should be wiped down with a soapy rag.

16

TABLECLOTHS, KITCHEN GLOVES, APRONS & OTHER FABRIC ITEMS

WASH Fabric items can be kashered by washing them with detergent in a washing machine set on “hot.” Items should be checked to make sure no pieces of food remain attached.

17

TABLES

COVERED Although wooden tables can be kashered, the common custom is to clean tables well and then cover them.

Cooking for Pesach is no simple task, particularly when we don’t have many of our pantry staples available for use. To give you a hand, we’ve provided an ingredient substitution guide. Happy cooking and baking!

1 tbls. chili powder (SEE RECIPE ABOVE)

SAUT E GARLIC IN OIL. ADD REMAINING INGREDIENTS. SIMMER UNTIL DESIRED CONSISTENCY IS REACHED.

COMBINE FIRST 6 INGREDIENTS IN SAUCEPAN TO BOIL. SIMMER FOR 15 MINUTES. *CAN USE PARVE BEEF OR CHICKEN STOCK FLAVOR CUBE IN WATER 2 tbls. paprika 1 tsp. cayenne pepper

It’s a half-hour to Chatzos. The korban Pesach has been eaten, and Menashe’s wife and daughters are clearing up from the Seder. Menashe scans the room, taking a count of his family members. From midnight and on, everyone must remain indoors to be protected from the Malach Hamaves. Their home, marked with the blood of the korban Pesach on its doorpost, will be a safe place when Makkas Bechoros happens.

Menashe starts with the youngest sextuplets, aged 18 months. They are all sleeping in their cribs. The four other sets of sextuplets are scattered around the house, and it takes time to make sure each child is accounted for.

It’s 10 minutes to Chatzos, and there is still one child that Menashe has not found.

“Has anyone seen seen Ovadia?!” Menashe cries out urgently. The entire family searches frantically as the time ticks closer to Chatzos.

By Rabbi Ezra Friedman

Imports of kosher food to the Israeli market have increased greatly over the past twenty years. Studies show that over fifty percent of food sold in Israeli supermarkets is imported, and that number continues to climb each year.

The Chief Rabbinate of Israel certifies thousands of facilities around Israel and uses substantial manpower in order to provide this service. The Rabbinate never intended to certify products and facilities outside of Israel, as its purpose is to certify kosher food for the local Israeli market.

The term “B’ishur HaRabbanut Harashit” (authorized by the Chief Rabbinate of Israel) appears on every kosher imported product that passes through the Rabbinate system. As opposed to the certification of local products, the Rabbinate has neither the manpower nor the finances to check and certify factories worldwide. This being the case, a number of years ago (when the import market was much smaller than it is now), the Rabbinate decided it would permit kosher products with foreign certifications to be imported, as long as the standards of the imported products more or less coincided with the standards of the Chief Rabbinate. The Rabbinate has no system to confirm the standards of foreign hechsherim and relies on written testimony only.

Unfortunately, there are many irregularities in the realm of kashrut supervision, particularly when huge numbers of products are being manufactured abroad and then imported to Israel. Some kashrut agencies are making

use of extreme leniencies, based on minority opinions that have been rejected by virtually all poskim over the generations. We are not referring merely to issues of, for example, Chalav Stam or Chadash. There have been documented cases of lenient kashrut organizations granting certification by phone/fax, without kashering any equipment or even showing up in person to supervise. In addition, there were cases in which ingredients were not checked properly and no regular visits took place. In other cases, specific products were labeled “Chalav Yisrael” or “Kosher for Pesach” when in fact the halachic standards of these categories were not met in the factories. One should note, however, that even if bediavad (ex post facto) these products might not “treif” one’s dishes, one should choose to avoid relying on weak, flimsy leniencies.

Unreliable hechsherim are particularly widespread in the house brands of Israeli supermarkets as well as with large Israeli food companies marketing imported items under their own labels. Unfortunately consumers mistakenly assume that B’ishur HaRabbanut Harashit on the label signifies that the Rabbanut has properly checked the product and approves its supervision.

Pesach can add additional stress in terms of imported foods. Badatzim in Israel have distanced from mass produced pesach products for decades. There was a time when mehadrin certifications in Israel would only approve products for pesach that had five ingredients or less. This phenomenon has affected Pesach certification

in Israel in a sometimes negative fashion. Meaning, Israel has a large population that consumes Kitniyot and Shruya (Gebrocht). In addition, there are numerous products that can be produced kosher for Pesach with all halachic requirments yet certain certifications stay away from the concern of looking more “lenient”. OU kosher has a symbol for those who consume kitniyot and feels responsibility to certify products that can be consumed on Pesach. Pesach products in Israel might have certifications that are not recommend and one should be very careful especially on Pesach. However, at the same time many of these products might be OU or actually be completely acceptable for Pesach. Feel free to reach out to the OU Israel Gustave and Carol Jacobs Center for Kashrut Education Hotline for guidance on these issues

The OU Israeli office has made great strides in the last few years regarding imported products. We have built a strong connection with the import division of the Chief Rabbinate, and importers have taken interest in OU products.

For the consumer’s part, when choosing imported products, one should always confirm that there is a reliable certification (a hechsher that you would trust if you were living overseas). This policy is familiar to kosher consumers living abroad, but less so in Israel. Upon seeing an unfamiliar hechsher, one should ask a rabbi who is knowledgeable in modern kashrut (and preferably involved with kashrut certification overseas). If stores and importers were to realize that reliable and

genuine kashrut is a priority for so many consumers, they would be more inclined to change their policies. We must strive as kosher consumers to demand products with reliable certification, both in Israel and around the world, and to reject products of questionable status. When we do this, we gain merit not only for our own good deeds, but in addition, we are doing a true chesed (helpful deed) for the kosher consumer in Israel. By improving the kashrut standards of imported foods, we help those in Israeli society who truly want to keep kosher.

By Rabbi Ezra Friedman

Eretz Yisrael, our homeland, is a place where a Jew can experience tremendous spiritual growth. Many of us send our children to learn here. We spend Yomim Tovim in Israel, quite often we vacation, and many have merited to settle here in the holy land. And, as in all aspects of life, with great potential comes great challenges. This is especially true regarding the topic of kosher food in Israel. There is no question that there is an abundance of kosher food in Israel, something we could only dream of in the Diaspora. Items we had to steer clear of overseas are suddenly kosher with strict supervision here in Israel. Yet at the same time, the challenges of the Israeli kosher market are in some respects more difficult than we are used to overseas. There is such a wide array of certifications, there are additional concerns due to the mitzvot hateluyot ba’aretz, and unfortunately, politics can also complicate matters and obscure the actual issues of kashrut. All these factors combined can make us feel we are groping in the dark when trying to choose products we can rely on.

Let’s try to shed some light on the issues and establish a degree of clarity here. Although it would be impossible to explain all aspects of the Israeli kosher food system in a single, brief article, we will try to outline the imperative factors, the most common misconceptions, and the general underpinnings of the system, in order to provide the reader with a more enlightened ability to decide which certifications they will choose to rely on.

Whenever a product is being sold or marketed, a company or service must ask itself, who is the target consumer? This fundamental question is especially important for the kosher food market in Israel. For the past 75 years, Jews overseas have faced many challenges in keeping kosher. Communities were built around making sure there was a kosher butcher, bakery and food services. Even today, with so many kosher products and establishments available, keeping kosher can still be a challenge at times. Any Jew who keeps kosher in the diaspora is making a conscience choice to do so. They are choosing to shop only from a limited selection of products and to spend more to purchase certified food in a country where

non-kosher food is much more common and usually more affordable as well. Since such a lifestyle demands very obvious sacrifices, the profile of the consumer who consistently keeps kosher is either Orthodox or extremely traditional.

In Israel, the reality is quite different. On the one hand the kosher opportunities in Israel are almost endless: hotels with full kosher certification, malls with entire kosher food sections, and of course supermarkets where every single product must be kosher, period. Yet this reality, for all its seeming ease and abundance, comes with a serious challenge. Studies have shown that over 75 percent of Israelis are interested in keeping kosher at some level or another; this, however, is in no way an indication of their religious observance. On the contrary, out of this large percentage, a majority do not consider themselves religious, but rather see keeping kosher as a cultural tradition they wish to hold onto. In fact, since they don’t identify as “religious,” many of the Israel’s kosher consumers will eat non-kosher when traveling outside Israel.

This situation, with the market for kosher food in Israel consisting largely of not-fully-observant Jews, greatly affects the way certifications are given. Since the average kosher consumer is interested in having access to as many products as possible, standards are much more fluid. Often, the non-religious kosher consumer has little or no knowledge of the different certifications, and in fact, as long as someone claims that their product or establishment is kosher, even with no certification whatsoever, a majority of kosher consumers in Israel will eat regardless of standards, supervision or reliability. For example, many European brand-named snacks and chocolates are not certified and are not consumed by the religious community in Europe, yet it is quite common to find these snacks certified in Israel as kosher with a symbol on a sticker and no apparent certification on the original label. Because the Israeli public wants to eat this product, and since supermarkets that would like kosher certification are required by the Chief Rabbinate to have all products certified, Israeli importers will go to great lengths to get the product certified. In most cases the importer pays for some type of certification, while the facility changes nothing in their production or ingredients. This demand from the Israeli kosher consumer makes it hard for higher-standard certifications to meet their needs. The consumer wants a worldwide

selection of all types of food, yet at the same time insists on some type of kosher certification, which naturally leads to a lowering of standards, sometimes to a drastic extent.

Of course, the religious kosher consumer takes a much different approach. Many certifications in Israel adhere to some of the highest standards. These certifications are often under the auspices of a “Badatz”— an abbreviation for beit din tzedek, a board of supervising rabbis.