DETERMINING OPTIMAL PRICE REDUCTIONS

Mathematical optimisation supports Tesco’s pricing strategy

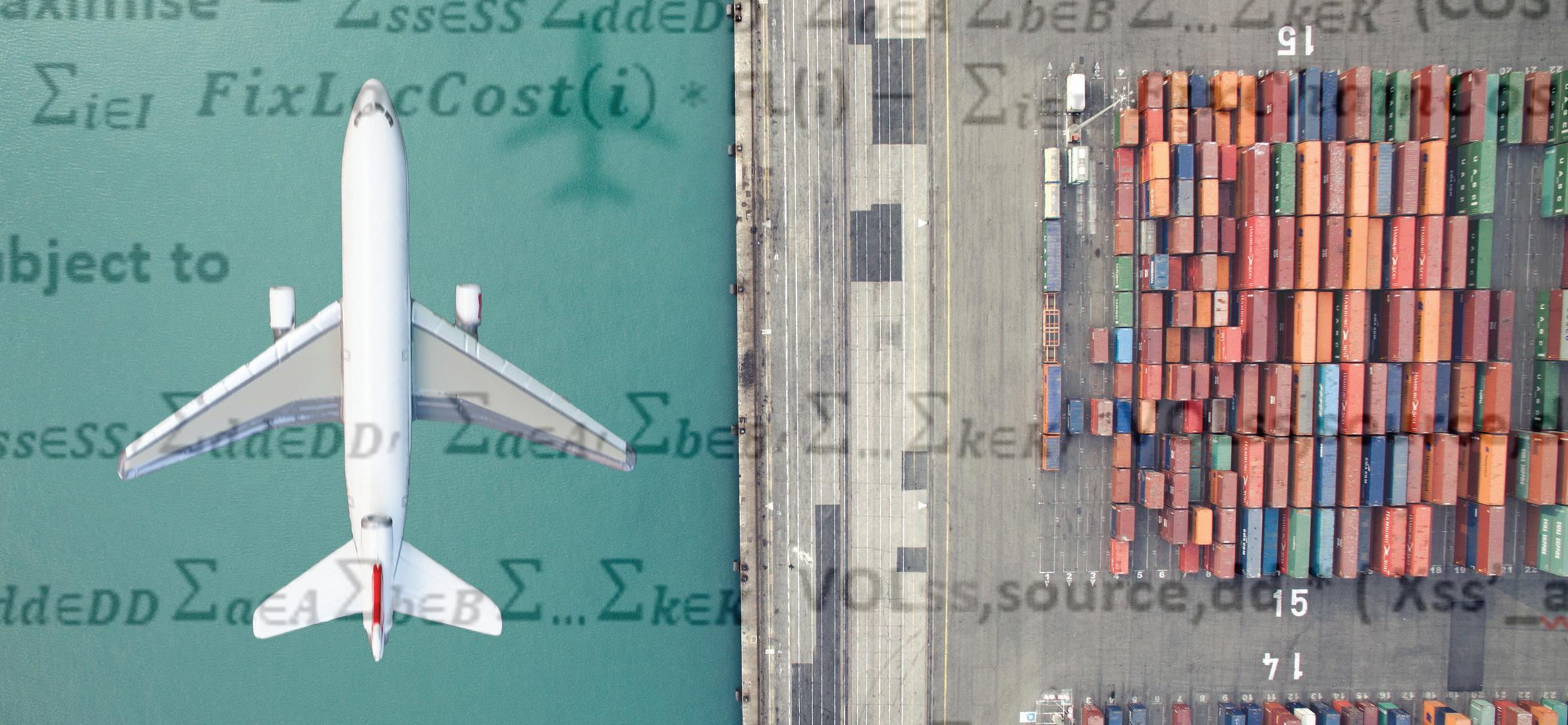

SUPPLY CHAIN DESIGN

Analytics gives cost and CO2 reductions and resilience

SIMULATION WORKS FOR CRIMESTOPPERS

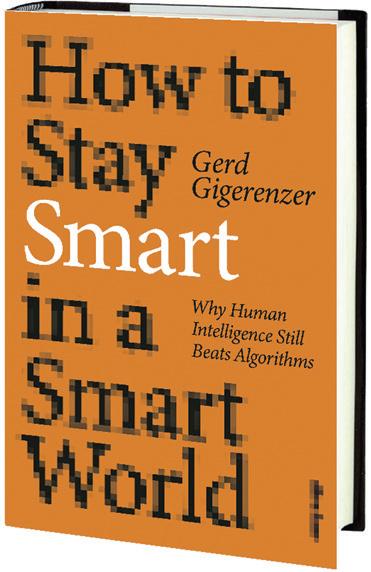

Staff wellbeing improved through better rotas

PHARMA FACTORIES

Analytics evaluates factory capacity requirements

SPRING 2023 DRIVING IMPROVEMENT WITH OPERATIONAL RESEARCH AND DECISION ANALYTICS ©

Tesco

EDITORIAL

Welcome to the seventeenth issue of Impact. Since 2015, our aim has remained the same: to show how effective O.R. can be for the benefit of organisations from the most diverse sectors (and for the ‘greater good’!). In this issue, you can read about how the not-for-profit organisation Crimestoppers has employed simulation to model their operations more realistically, better control staffing decisions and provide ongoing guidance to their management team on a daily basis.

The flavour of this issue is a ‘classic’ one: O.R. in logistics and supply chain management. Neil Robinson demonstrates how Vehicle Routing Problems remain very relevant to this day, whilst discussing key factors that differentiate ‘today’s VRPs from those of yesteryear’. Emile Naus analyses real world challenges in designing supply chains and Tesco’s article talks about how O.R. can help to take a closer look at the options available near the end of a product’s life.

Brian Clegg reports on some of the best practices (e.g. Knowledge Transfer Partnership projects) through which academia and industry can jointly exploit the potential of O.R. He illustrates this through the work done at the PARC Centre in Cardiff. GSK and Decision Lab also highlight the crucial role of crossorganisational collaboration in developing modelling and analysis methods that can quickly scale to a range of processes within the same industry (pharma).

On becoming the new editor, I cannot thank Graham Rand enough for bringing this title to life almost a decade ago, for his brilliant editorial work over the years, and, more personally, for his immense patience with me during the handover process. Thanks also to Carol McLaughlin at the O.R. Society and Katie Johnson at Taylor & Francis for the equally fantastic support during my ‘initiation’.

I hope you enjoy reading this issue.

Maurizio Tomasella

The OR Society is the trading name of the Operational Research Society, which is a registered charity and a company limited by guarantee.

Seymour House, 12 Edward Street, Birmingham, B1 2RX, UK

Tel: + 44 (0)121 233 9300, Fax: + 44 (0)121 233 0321

Email: email@theorsociety.com

Secretary and General Manager: Gavin Blackett

President: Gilbert Owusu

Editor: Maurizio Tomasella

Maurizio.Tomasella@ed.ac.uk

Associate Editor: James Bleach

Print ISSN: 2058-802X

Online ISSN: 2058-8038 www.tandfonline.com/timp

OPERATIONAL RESEARCH AND DECISION ANALYTICS

Operational Research (O.R.) is the discipline of applying appropriate analytical methods to help those who run organisations make better decisions. It’s a ‘real world’ discipline with a focus on improving the complex systems and processes that underpin everyone’s daily life – O.R. is an improvement science. For over 70 years, O.R. has focussed on supporting decision making in a wide range of organisations. It is a major contributor to the development of decision analytics, which has come to prominence because of the availability of big data. Work under the O.R. label continues, though some prefer names such as business analysis, decision analysis, analytics or management science. Whatever the name, O.R. analysts seek to work in partnership with managers and decision makers to achieve desirable outcomes that are informed and evidence-based. As the world has become more complex, problems tougher to solve using gut-feel alone, and computers become increasingly powerful, O.R. continues to develop new techniques to guide decision-making. The methods used are typically quantitative, tempered with problem structuring methods to resolve problems that have multiple stakeholders and conflicting objectives. Impact aims to encourage further use of O.R. by demonstrating the value of these techniques in every kind of organisation –large and small, private and public, for-profit and not-for-profit. To find out more about how decision analytics could help your organisation make more informed decisions see https://www.theorsociety.com/about-or/or-in-business/ O.R. is the home to the science + art of problem solving.

Taylor & Francis, an Informa business All Taylor and Francis Group journals are printed on paper from renewable sources by accredited partners.

Published by

CONTENTS

7 TESCO: REDUCED TO CLEAR

Aleksandar Kolev, Ross Hart and Ekaterina Arafailova report how Tesco’s Data Science Team developed an optimal pricing strategy for items about to be removed from shelves

15 REAL WORLD PROBLEMS IN DESIGNING SUPPLY CHAINS

Emile Naus explains that whilst designing supply chains is hard, the use of analytics enables results that are cost effective, more environmentally friendly and with the right balance of service and risks

19 THE ROAD TO BETTER OUTCOMES

Neil Robinson gives insight into how Güneş Erdoğan’s routing software is reducing costs for logistics companies

23 PLANNING GSK’S FACTORIES TO MEET THE GROWING DEMAND FOR MEDICATIONS

Giovanni Giorgio, Natasha Zheltovskaya, Peter Riley and Jacob Whyte tell us how Decision Lab used analytic modelling to help GSK plan factories in Italy and England

29 CHANGING THE ROLE OF LOGISTICS

Brian Clegg describes the involvement of Aris Syntetos’ Cardiff University team in supplying forecasting and inventory management support to companies

34 CRIMESTOPPERS IMPROVES STAFF WELLBEING WITH SIMULATION

Naoum Tsioptsias and Frances Sneddon show how simulation has helped improve staff morale whilst allowing good service to be maintained

4 Seen Elsewhere

Analytics making an impact

11 Operational Research Supporting Sport

Nicola Morrill explores the role O.R. plays in sport, with examples concerning tactics and strategy, scheduling, scenario planning and systems modelling

38 Universities making an impact

Brief report of a student project

39 I am not a robot

Geoff Royston discusses the impact of Artificial Intelligence, including ChatGPT, based on How to Stay Smart in a Smart World by Gerd Gigerenzer and Life 3.0 by Max Tegmark

DISCLAIMER

The Operational Research Society and our publisher Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group, make every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in our publications. However, the Operational Research Society and our publisher Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by the Operational Research Society or our publisher Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. The Operational Research Society and our publisher Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group, shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

Reusing Articles in this Magazine All content is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives License which permits noncommercial re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited, and is not altered, transformed, or built upon in any way.

SEEN ELSEWHERE

ROCK ART

Andrea Jalandoni, of Griffith University in Queensland, Australia, is making use of machine learning to analyse vast amounts of data, such as photos and tracings, collected at sites of millennia-old rock art in the Pacific, Southeast Asia and Australia. ‘Manual identification takes too much time, money and specialist knowledge’, Jalandoni says. She worked with Nayyar Zaidi, of Deakin University in Victoria, Australia to test machine learning to automate image detection using hundreds of photos from the Kakadu National Park in Australia’s Northern Territory, some of which showed painted rock art images and others with bare rock surfaces. The system found the art with an accuracy of 89%. Initial results were published last August –see https://bit.ly/RockArt2022.

The rock art is created from pigments made of iron-stained clays and iron-rich

is an essential aspect of contemporary indigenous cultures that connects them directly to ancestors and ancestral beings, cultural stories and landscapes’, Jalandoni says. ‘Rock art is not just data, it is part of Indigenous heritage and contributes to Indigenous wellbeing’.

‘High-tech companies, such as Google, defined as “analytical competitors,” use data science aggressively throughout their entire enterprise to sharpen operational performance and efficiency and improve customer experience in their retail and online search businesses, respectively. Companies like American Airlines pioneered the use of data and analytics in the field of revenue (yield) management in the 1980s to generate $400-$500 million in incremental revenue annually. UPS saves $300-$400 million annually with its On-Road Integrated Optimization and Navigation (ORION) application that guides their 55,000 delivery truck drivers every day. Walmart generates millions of dollars in value annually by applying predictive and prescriptive analytics to optimize its markdown pricing strategy’.

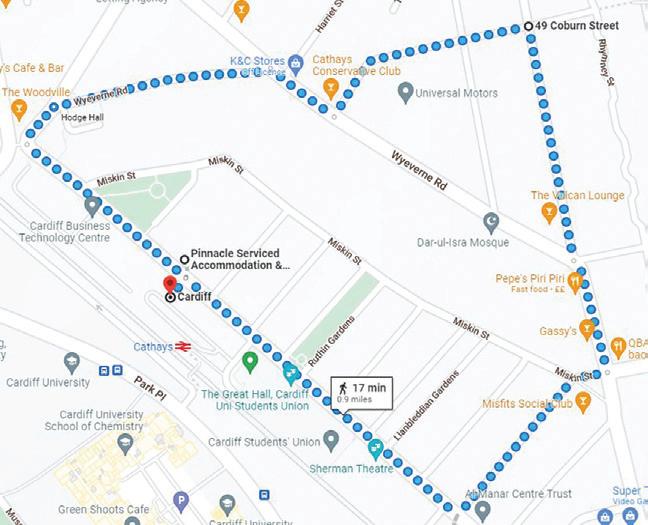

10000 STEPS, EXACTLY

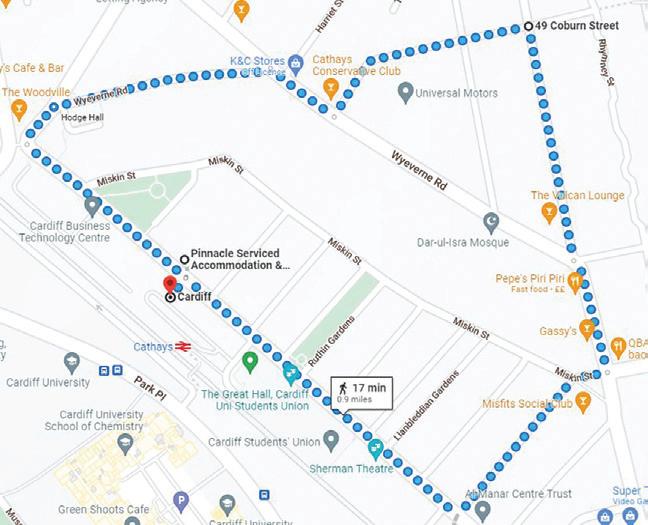

How would you like to create a route of a specific length? Rhyd Lewis and Padraig Corcoran of Cardiff University have developed a journey-mapping algorithm to allow you to do just that. Turned into scientific terms, their paper, published in the Journal of Heuristics, is entitled ‘Finding fixed-length circuits and cycles in undirected edge-weighted graphs: an application with street networks’. You can read it at https://bit.ly/Rhysand Corcoran2022 or maybe go for a walk.

But, despite these, and many others, success stories, ‘according to a study by Deloitte Analytics and Tom Davenport, only 20% of data science models built are actually deployed into a production system supporting a business process’. Why is this? Gray argues that ‘the problem is not with the mathematics and technology but rather with the actions of the people (practitioners and leaders) … and the processes employed to execute and manage data science projects’.

ores that were mixed with water and applied using tools made of human hair, reeds, feathers and chewed sticks. Some of the paintings in this region date back 20,000 years, making them among the oldest art in recorded history, only a fraction of the works in the park have been studied. ‘For First Nations people, rock art

SUCCESS AND FAILURE

In a first in a series of ten articles, Douglas A. Gray in INFORMS’ Analytics magazine (https://bit.ly/Gray2023) discusses successful Data Science projects and why they fail. He points out that

Gray’s remedy is twofold. First, begin with the end in mind: ‘You don’t want to just build a model; rather, you want to embed that model into a mission-critical system that supports a key business process such that greater economic efficiency (i.e. lower cost, greater revenue, improved customer experience) can be achieved on an ongoing basis in an

IMPACT © THE OR SOCIETY 4

© Andrea Jalandoni

© Rhyd Lewis

automated manner with little or no human intervention, creating a flywheel effect generating business value’. Secondly, sharpen the saw. By this he refers to appropriate education, so that ‘students, practitioners, leaders and executives “sharpen the saw” and fill in the knowledge gap in their training and education that heretofore was learned only through real-world work experience’.

PREDICTING ASSET HEALTH

An analytics engine created by Viking Analytics, using AI-based algorithms, that automatically detects unseen or pre-failure operational conditions for electrical equipment, makes it easier for operators to prevent costly failures, plan maintenance efficiently and maximise uptime. It will allow customers to predict anomalies before they become a risk to their operations. Rajet Krishnan, CEO of Viking Analytics commented: ‘Our company’s mission is to allow industrial specialists to easily extract insights and value from both process data and asset data through AI’. A strategic partnership with ABB allows Viking Analytics’ technology to complement the ABB Ability Asset Manager, and provide full remote visibility of asset and electricalsystem health status.

Sherif El-Meshad, of ABB: ‘With the pressure on to ensure uptime and prolong the lifecycle of electrical assets, the partnership with Viking Analytics allows us to develop analytics that will help customers maintain their

operations and cut costs. Customers will get the insights they need to make informed decisions about their electrical equipment fleet and take preventative actions to avoid costly failure’. Read more at https://bit.ly/VikingAnalytics.

redundancies, errors in data sets muddle the accuracy of data analysis.

Second, the Algorithms you’re using aren’t accurate enough. Most algorithms aren’t one hundred percent perfect; most of them have their fair share of flaws and simply don’t work the way you’d like them to every time you use them.

Third, the Models you’re using aren’t that good. ‘Algorithms can crunch data all day long, but if their output isn’t going through models that are designed to check the subsequent analysis, then you’re not going to have any usable or useful insights’.

CATCHING THE EYE

Inefficient management of resources and waiting lists for high-risk ophthalmology patients can contribute to sight loss. So, researchers at Cardiff University used O.R. to develop a decision support tool to determine an optimal patient schedule for ophthalmology patients. Available booking slots as well as patient-specific factors such as eyecare measure risk factors, referral-to-treatment times and targets, and their locations were taken into account. The model can be applied and implemented without the need for additional software, to generate an optimised patient schedule. Their published paper can be found at https:// bit.ly/CardiffEye2023.

THREE MISTAKES AND YOU ARE OUT

An article by Nahla Davies, https://bit.ly/ ThreeDataMistakes in Data Science highlights the top three mistakes that companies commonly make that affect the accuracy of their data analytics.

First, Data Cleaning Isn’t at the top of your to-do List. Most sets of data have their fair share of errors. Whether they’re typos, weird naming conventions, or

HUMANITARIAN AID

A report by the Geneva Centre of Humanitarian Studies (https://bit.ly/ ORandHumanitarianAid) argues that there is an increasing and critical need for O.R. in humanitarian settings, because time is invariably of the essence and problems and needs are often ill-defined. Practising O.R. in humanitarian settings is often challenging, but there is need for evidence-based decision-making by humanitarian organisations. O.R. can help in equipping decision-makers, at an individual programme and at the policy level, with the high-quality evidence that is needed. The Centre has gained extensive experience as a community of researchers and practitioners over the years on how to mitigate and adapt to many of the common challenges faced in humanitarian operations.

IMPACT | SPRING 2023 5

Photo by Jordan Whitfield on Unsplash © Tearfund

Photo by Emmanuel Ikwuegbu on Unsplash

TESCO: REDUCED TO CLEAR

TESCO IS THE UK’S LARGEST GROCER, operating over 2700 stores. As a business, we are committed to serving our customers, communities, and planet a little better every day, by offering the products that customers need while also reducing their impact on the planet. A key step in Tesco’s value chain is what happens at the end of a product’s lifecycle, when it is no longer displayed to customers. This is the last opportunity to sell an item to a customer or donate it to the community so that it doesn’t go to waste.

WHAT DO YOU DO WITH EXPIRING STOCK?

Tesco, like most large retailers, discounts items that are close to being

removed from shelves. This process is applied across Tesco’s product range, from general merchandise and clothing to fresh food. In particular, food items are reduced in price as they get closer to expiry to sell them before they go to waste. The question that every retailer must answer is: By how much should the price be reduced? Reduce too little and the item simply won’t sell but reduce too much and the sale might become a net loss for the retailer.

Finding the optimal pricing strategy was the task given to Tesco’s Data Science Team. To tackle this problem, we developed a novel multi-stage Clearance Pricing Optimisation system and deployed it across all Tesco stores in the UK where it is applied to 100,000s of unique products annually. The objectives

IMPACT © 2023 TESCO STORES LIMITED 7

ALEKSANDAR KOLEV, ROSS HART AND EKATERINA ARAFAILOVA

© Tesco

of this solution are to: (1) clear excess stock by a specific date (either expiry or new product roll-out date), (2) increase revenue by finding the optimal discounts, and (3) reduce operational costs and provide further insights of in-store processes. Our solution reduced the number of fresh food items going to waste by 5%, and increased the revenue generated by 1.5-13% across multiple food and non-food product lines.

Our solution reduced the number of fresh food items going to waste by 5%, and increased the revenue generated by 1.5-13% across multiple food and non-food product lines

THE PROBLEM AND ITS CHALLENGES

The challenge of expiring stock of both food and non-food items is something Tesco faces daily. The question we need to answer is: What clearance strategy should we use to increase revenue and, most importantly, decrease waste?

Tesco employs a product line specific, multi-phase reductions strategy to reduce waste and recover revenues from soon-to-expire stock. The time horizons involved vary depending on the business domain, for example:

• Fresh food items enter a pre-defined three-stage reduction process 24-48 hours before they reach their sell-by-date. Tens of thousands of unique products are reduced each year.

• Non-food items covering electronics, home & entertainment, and clothing enter an up to 4 stage reduction process, where each stage could last weeks. Tens of thousands of unique

products are reduced each year.

• Packaged food items with a long shelf life but highly seasonal demand (e.g. Christmas, Easter, Halloween etc. themed items) enter a pre-defined two-stage reduction process after their peak demand. Every seasonal event accounts for hundreds of unique product reductions across most stores.

Despite the differing time horizons, the high-level problem statement is the same: Calculate an optimal multi-phase pricing strategy, that at each phase further reduces the price of items as they approach their expiry date. The main challenges associated with this problem are:

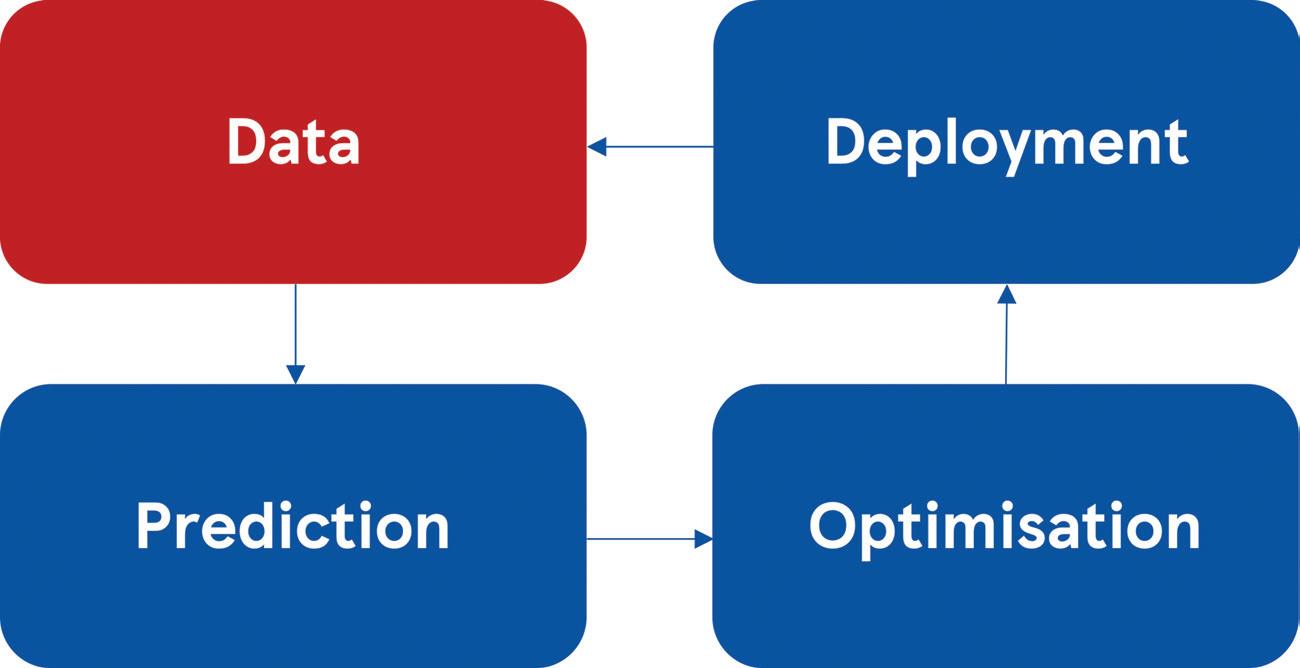

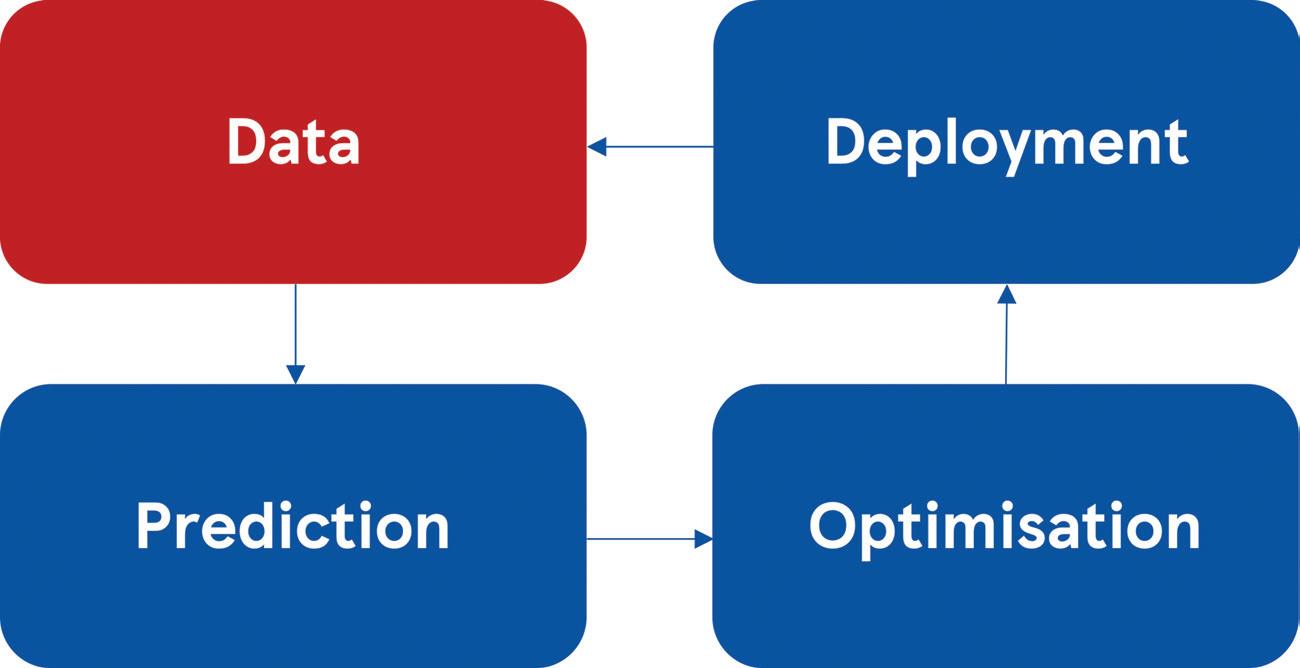

• It likely requires solving two sub-problems: prediction and then optimisation, which scientifically makes it hard and requires different types of expertise.

• Historic data is not always available to build robust prediction models.

• Given the scale of the problem, driven by number of products and stores, the optimisation problem is computationally intensive.

The next section describes our approach for tackling this problem and the associated challenges.

THE SOLUTION

The solution that we built leveraged the same three component technique to find an optimal pricing strategy in all business domains: (1) first we model how we expect demand to react if we were to set a specific reduction (prediction), (2) we then choose optimal reductions accordingly to optimise for revenue maximisation and waste reduction (optimisation), and (3) we pass the results to the business (deployment).

Prediction

The first problem we face is building appropriate elasticity demand models, which predict how many items will sell if we set a specific price point. The biggest problem posed here is the lack of diversity of past reduction data. Tesco has typically applied static reduction strategies in the past, meaning similar reductions are applied in similar circumstances. It is therefore difficult to model exactly how customers will react to new prices that have never been used in stores before.

IMPACT | SPRING 2023 8

FIGURE 1 SOLUTION LIFE CYCLE

Model selection was crucial to getting this right – our solution has focused on the use of machine learning models that consider domain expertise combined with strong assumptions about the relationship between features and targets to deliver predictions that are useful in the context of price optimisation. This allows pricing outside the regime of reductions that were previously observed. Figure 2 shows an example of predicted waste and revenue curves, where the red dotted line represents waste, and the blue line – sales.

Optimisation

The second part of the solution involved building an appropriate optimisation routine to select the optimal set of reductions. The optimisation problem was to decide an appropriate set of reductions to apply across multiple phases to (a) reduce waste and (b) maximise revenue.

The optimisation problem was to decide an appropriate set of reductions to apply across multiple phases to (a) reduce waste and (b) maximise revenue

From our demand elasticity models, we will be able to predict how many items we’d sell, and thus what the appropriate pricing strategy might be. Setting the price high leads to fewer sales, and setting the price at close to zero leads to high sales but next to no revenue – the optimal price is usually between these two extremes (Figure 2). Setting a lower price than the one which optimises revenue price leads to more items sold and less waste, but does this by sacrificing some revenue. The reduced to clear price optimisation is therefore always a trade-off between waste and revenue.

We use both exact and heuristic approaches for solving the optimisation part of the markdown problems arising in various business domains. The choice of the appropriate technique is driven by the business constraints, scale and complexity.

Deployment

The final problem to tackle was the deployment of the solution to the business. As was the case with the optimiser, the deployment technique has been crafted with each business use case in mind. For general merchandise, clothing, and seasonal packaged food items the problems are automatically triggered overnight. The optimiser then selects the best reduction strategies and suggests them to the merchandisers as a decision support tool. Fresh food reduction recommendations must be automatically suggested instantaneously: to deploy this solution, we pre-compute a wide range of product and trading scenarios we expect to see in store, which are then looked up by Tesco colleagues as a specific scenario occurs.

SUCCESS STORIES

The solution described in the previous section has been implemented and deployed in three business domains. Overall, we achieved improvement in both main KPIs, revenue and waste, with three observations below expanding more on the obtained results:

1. The largest impact of our algorithmic solution is present across fresh food items. We have reduced the number of expiring fresh food items going to waste by 5%, which prevents millions of fresh products from going to waste each year, yet also increases the revenue generated from reduced-to-clear fresh food items. By tuning the optimiser’s constraints, we were able to explicitly favour lower prices and waste

IMPACT | SPRING 2023 9

©

FIGURE 2 WASTE AND REVENUE CURVE FOR VARIOUS REDUCTION LEVELS

Tesco © Tesco

reduction over revenue in this trade-off.

2. The longest lasting solution delivered by our team is a human-in-the-loop decision support system for clothing and general merchandise, that in addition to optimising the reduction strategy for each line, provides human merchandisers with accurate forecasts of future revenue and stock. By investing effort to continuous scientific development and leveraging the feedback from live tests, we demonstrated the results that consistently outperform manual decisions making in terms of revenue.

3. Last but not least, we increased the revenue generated from reduced-toclear seasonal food (e.g. Easter eggs, chocolate Santa) without impacting waste.

We have reduced the number of expiring fresh food items going to waste by 5%, which prevents millions of fresh products from going to waste each year

SUMMARY

We were delighted to be awarded the OR Society’s President’s Medal in 2022 for this work.

Finding an optimal reduction strategy is a problem faced by every retail business. There are two conflicting objectives to not only increase revenue but also reduce waste and finding a solution that achieves both is a non-trivial task. At Tesco we have built and deployed a predictoptimise solution across multiple product areas that successfully reduced waste and our impact on the planet, and also increased revenue for the business.

Aleksandar Kolev is a Senior Data Scientist at Tesco. He has been working on the two projects related to food price reductions. Aleksandar, as a keen statistician and researcher, helped the team improve not only the scientific solution but also identify key research areas that enabled us build even better algorithms.

Ross Hart is a Data Science Manager at Tesco. He has a PhD in astrophysics, and now uses machine learning and optimisation techniques to solve both online and in-store Data Science problems.

Ekaterina Arafailova is a Lead Data Scientist at Tesco. Her background is in operational research, and at Tesco she focusses on optimisation problems arising in various business domains. Using operational research approaches, Ekaterina and her team have already delivered a significant value across the business, with more to come.

IMPACT | SPRING 2023 10

© Tesco

OPERATIONAL RESEARCH SUPPORTING SPORT

Nicola Morrill

Nicola Morrill

True optimization is the revolutionary contribution of modern research to decision processes.

George Dantzig

Given the recent round of large sporting events I thought in this article I would explore the role O.R. plays in sport. I hadn’t appreciated until I started looking just how vast the role is! So, while this article shares something of the use of O.R. in sport, offering an insight into the nature of questions that O.R. can help address – many of these are conceptually transferable beyond sport.

The goal of my columns is to share the discipline with users/potential users of O.R. by highlighting how the ‘business’ challenges they may be facing can be supported. In addition, they may also stimulate thinking in the O.R. community about possible areas O.R. could help in the area being considered.

O.R. AND SPORT

O.R. is used in a wide range of sports: cricket, rugby, football, tennis, darts, racing, and many more. There are variances in the nature of its use across different types of sport. An article by Wright (https://bit.ly/MBWright2008) discussing ‘50 years of O.R. in sport‘, identified the areas of support that O.R. tends to provide as tactics and strategy, scheduling, forecasting and other areas.

In line with Wright’s thoughts about future areas, sport is also making use of the large volumes of data collected and there is still more that could be done related to the use of behavioural O.R. Broadly speaking, the areas of coverage are operational, planning and also sport in a more strategic sense beyond an individual activity or team. In line with this, there are some examples of foresight and futures being used in the context of sport.

Given that I have come to learn that the use of O.R. in sports is an enormous area, this article will share some examples of O.R. supporting sport across the following areas: tactics and strategy, scheduling, scenario planning and systems modelling. It is by no means an exhaustive representation of the help the disciplne of O.R. provides to different sports across different areas.

TACTICS AND STRATEGY

A significant area of sport where O.R. helps is related to tactics and strategy. Examples include:

• Improving team and individual performance. An Impact article by Lade (https://bit.ly/Lade2019) shared how the use of an O.R. tool called INSIGHT by a variety of organisations, including England Rugby, Bath Rugby, the Football Association (FA), British Athletics, British Sailing, GB Snowsport, the Lawn Tennis Association (LTA) and Team Sky is helping improve individual and team

IMPACT © THE OR SOCIETY 11

© Graham Rand

performance. This has data analysis with the use of AI at its heart. A really interesting application area discussed is work on predicting player ranking over the duration of their career.

• Cricket team selection. A paper by Sharp et al. (https://bit.ly/Sharpeetal2011) explored how to select the optimal team for a 20/20 cricket match. The work focussed on whole team selection using an integer programming approach that can be extended to a multistage team selection game. This involved considering the mix of different skills, the requirement of the match and team circumstances. This approach has been used in fantasy league games, updating the team as more information becomes available.

The work built on that of others looking at cricket performance evaluations. An interesting modelling approach is that of Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA), which is used to look at the performance and benchmarking of different ‘decision-making units’ (DMUs).

• Finding inefficiencies. Bhat et al (https://bit.ly/ Bhatetal2019) provide an overview of the use of Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) in Baseball, Basketball, Cricket, Cycling, Football, Golf, Handball, Olympics, and Tennis. In the work presented, comparisons across the sports were between players, teams and nations at, for instance, the Olympics. In providing a measure of relative efficiency, DEA was able to identify strengths and weaknesses in the areas being considered. Most papers related to football club comparison concern English football and the authors believe this is because they were the first to be floated on the stock market.

• F1 pit stop tyre strategy. Maharwal et al. (https://bit.ly/ Maharwaletal2019) looked at the roles of O.R. in sports and gaming. One example provided is the use of game theory to support decisions around tyre change in Formula 1 racing. It considers a range of factors such as the optimum time to come in and change tyres and its relationship with when the driver rejoins the track – looking to re-enter at a time when being blocked by slower drivers is minimised.

IMPACT | SPRING 2023 12

© Phil Britt

• E-sports gaming centre optimal seating strategy. Kwag et al (https://bit.ly/Kwagetal2022) looked at how an e-sports gaming centre can best allocate its seats. The work undertook data analysis to look at the impact on revenue of different seat allocation strategies for large and smaller groups. There are differences in the nature of gaming centres compared with other areas, such as airlines, hotels and cinemas, which consider a similar question. The work showed that prioritising the seat allocation of larger groups does not always generate the largest revenue.

There are many more examples of O.R. supporting tactics and strategy at the operational and strategic levels.

SCHEDULING

A significant area where O.R. is used is in the scheduling of matches for large tournaments. An Impact article by Wright, (https://bit.ly/MBWright2018), provides a good lay person introduction to how O.R. is used to help with scheduling for sports and the type of questions that are required.

• Football and cricket tournament scheduling. O.R. is routinely used in cricket and football scheduling and the Marharwal et al. paper highlights different examples and methods used for this. In an Impact article, Durán et al. (https://bit.ly/Duran2017) discussed the optimisation work used to schedule football leagues in Chile being extended and used in the scheduling of football World Cup matches.

• Scheduling a sports conference. Nemhauser and Trick (https://bit.ly/NemhauserandTrick1998) discussed the problem of scheduling a major college basketball

conference and the analytical approach used in the real situation was in the end able to turn around schedules in a day. The exploratory work generated a possible 10 billion schedules!

CONSIDERING THE FUTURE

• Scenario planning and sports tourism. Darabi et al. (https://bit.ly/Darabi2020), described the use of scenario planning to explore the suitability of sports tourism to a particular area, Mashhad, Iran. The work identified that the area has great potential for attracting tourism in the future and identified a number of factors to be influenced to enable this, including: natural drivers, social-cultural drivers, managerial and programmatic drivers, economic drivers, advertising drivers, service drivers, and infrastructure drivers.

SYSTEMS MODELLING

There is some recent work looking at systems modelling in sports: an area perhaps where more could be done.

• Systems approach to sports injury. Hulme at al. (https:// bit.ly/Hulmeetal2019) explored the use of a complex systems approach to sports injuries. The work used agent-based modelling to model the occurrence of sports injuries, focussing on distance running related injuries. They considered changing running distances and the use of different runners ‘tools’. They showed it is possible for athletes to reach and surpass individual physical workload limits, for instance, building weekly running distances over time after injury. The authors concluded that simulation-based techniques have a role to play in the complex area of sports injury research.

• Modelling the sports entrepreneurship ecosystem. Darooghe et al. (https://bit.ly/Daroogheetal2022) investigated sports entrepreneurship within Iran and, given the complexity of the eco system, used system dynamics to do this. Their work was especially interested in understanding how to achieve sustainable development of entrepreneurship, highlighting the key role sports tourism plays in this. The modelling undertaken identified that as well as infrastructure, sports entrepreneurship also requires other elements, such as, cultural and social preparations, cooperation of educational systems, administrative and financial support.

IMPACT | SPRING 2023 13

© Graham Rand

• Screening attendees at a large sporting events. Holt, in an impact article (https://bit.ly/CHolt2016), discussed the role of simulation modelling and broader O.R. in helping to secure international sporting events. Specifically addressed were effective screening of spectators, athletes and workforce at the world’s three largest multi-sport events. The article discussed the broader strategies adopted in order to minimise queueing and disruption to people –essential to this was security screening not being treated as an isolated activity.

WANT TO LEARN MORE?

This article provided an insight into some uses of O.R. in sport and for those interested in learning more there are several papers in the Journal of the Operational Reseach Society There are also several books, including those edited by Wright (2015) and by Harrison and Bukstein (2016). For those interested in engaging more with community there is an INFORMS (The Institute for Operations Research and the Management Sciences) area (https://connect.informs.org/ sports/home) aimed at bringing folks together. The main

O.R. Society annual conference sometimes has an O.R. in sports stream. So lots of opporunity to learn more about this application area of O.R.

The OR Society runs training courses on much of the above if you want to bolster your in-house team. We are an active community and there are various events running through the year that may be of interest.

Nicola Morrill is a Fellow of the O.R. Society and currently volunteers as its board level Diversity Champion. She writes in a private capacity – all views expressed are her own and all examples are available in the open domain. You can contact her on Nicola.Morrill@googlemail.com

FOR FURTHER READING

Harrison, C.K. and S. Bukstein, eds. (2016). Sport Business Analytics. New York: Auerbach Publications. Wright, M., ed. (2015). Operational Research Applied to Sports. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

IMPACT | SPRING 2023 14

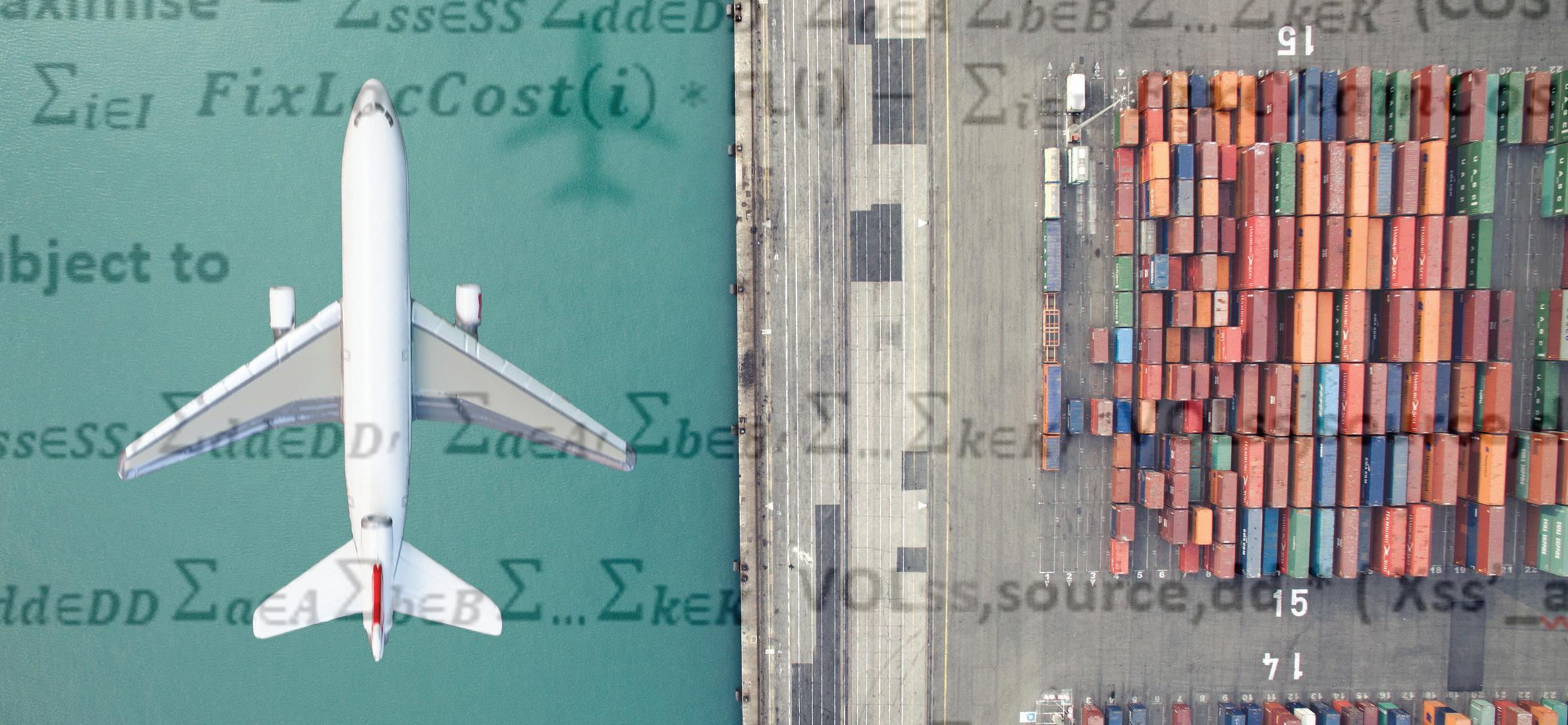

REAL WORLD PROBLEMS IN DESIGNING SUPPLY CHAINS

EMILE NAUS SUPPLY CHAINS HAVE TRADITIONALLY OPERATED IN THE BACKGROUND, but in the past few years they have become front page news. From a global shortage of electronic components to supermarket shelves without toilet rolls, flour or salad, a fastfood chain without food and a container ship stuck in the Suez Canal, the importance of supply chains to our global businesses and people are now clear.

These issues have highlighted the risks that are embedded in our supply chains. Major disruption happens, and more often than most people consider. But how do we go about designing supply chains, ideally without hitting the front page of the popular press?

Supply chains are a series of nodes that connect raw material suppliers via factories, warehouses and transport links to end consumers. That is a

relatively simple statement, but typically there is a lot of detail behind this. In the typical literature, it is often represented in a linear fashion, but the reality is often a spider’s web of interconnected supply chains.

The science of these supply chains, at a static level, is pretty well understood, such as optimisation models for network design and transportation routing and simulation models for stochastic problems in factories and warehouses. But models are based on data and assumptions, and the question very quickly becomes how well these reflect reality.

PRACTICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Let’s take network locations as an example. These are typically used to assess where to construct new

IMPACT © 2023 THE AUTHOR 15

© BearingPoint

warehouses and will take inputs such as customer and supplier locations, demand and transport distances. Since demand is often correlated against population, running these models for different businesses typically gives similar outputs, leading to a concentration of warehouses around the M1 between Northampton and Leicester. Figure 1 shows an example for Magna Park Lutterworth, with around 800,000 m2 of warehouses, but relatively limited access to a local labour pool.

The models typically ignore soft requirements (such as labour and skills), but also often don’t clarify the relatively sensitivity of location to the overall solution. At the same time, moving a location 40 miles north or south may not have a material effect on the solution, but a two-mile diversion from a major transport network can have a huge impact. For a major retailer, this ‘minor’ change would add nearly 750,000 lorry miles per annum.

Equally, it is easy to assume that data is widely available but getting timely and accurate data across a multi-tier supply chain is very hard. The reason is not that the data doesn’t exist, but that the data is

proprietary and different entities in the supply chain have different levels of visibility. And since most supply chains consist of businesses with interlinking commercial relationships, this data is sensitive.

As a consequence, whilst it seems easy to draw a supply chain map, it is much harder to extend this across multiple tiers. We saw this when the Rana Plaza building in Dhaka collapsed in 2013. Several retailers did not know that their products were produced in these factories, partially due to a long list of commercial contracting and subcontracting relationships. Whilst this may have initially resulted in a low-cost sourcing of products, the ultimate cost in human lives (and resulting brand damage to the retailers) was huge.

Long supply chains are typically not static. Businesses change suppliers, or relocate to a new facility, and transport providers change which nodes they use (especially relevant for rail, sea and air transport, where different terminals might be used). The models would need to keep track with the levels of change, and in particular sourcing options can change both frequently and potentially temporarily.

the length of supply chains, with large number of nodes, typically results in models that are mathematically and computationally challenging

Finally, the length of supply chains, with large number of nodes, typically results in models that are mathematically and computationally challenging. At BearingPoint we use Gurobi as our mathematical optimisation engine, which combines a best-in-class engine with the power of cloud computing. But we still hit limits to what is an acceptable model complexity and resulting run-time.

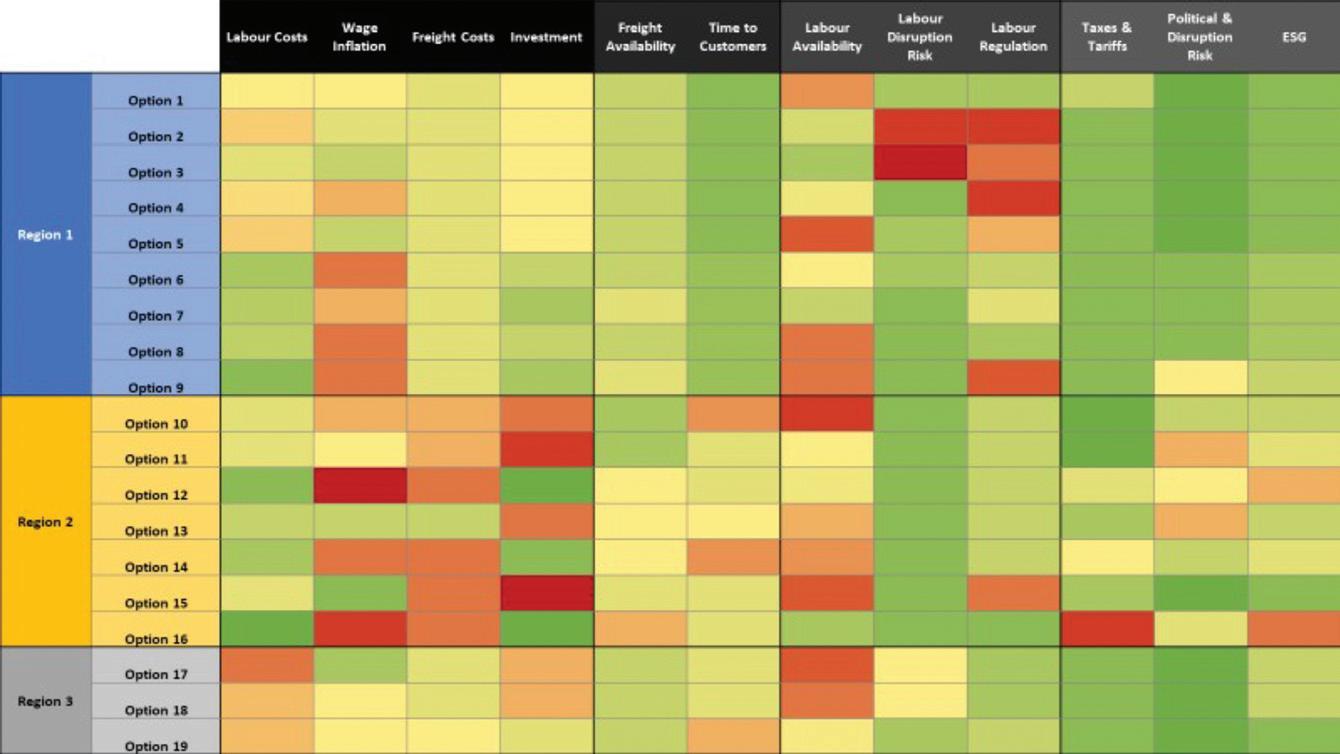

BALANCING DIFFERENT ELEMENTS

In order to model supply chains effectively, we therefore need to blend the rigour of the data and modelling with a practical application of those factors that are either unknown, changeable or difficult to model. That doesn’t mean that we can’t use data to assess some of these factors, it is just treated outside the core model.

As an example, we have recently completed the global network review for a business with a large product range and a relatively short order lead time. A key factor in the decision making was how we could balance cost, investment in inventory and infrastructure and service levels. This is a fairly typical application, where advanced models can support the decision making. “The power of combining the quantitative modelling with the qualitative assessments resulted in a series of workshops where the key stakeholders could discuss, using facts and data, what the best

IMPACT | SPRING 2023 16

FIGURE 1 AERIAL VIEW OF MAGNA PARK LUTTERWORTH (SOURCE: GOOGLE EARTH PRO)

Map data: Google

options are to balance cost, investment and risk for our future supply chains”: CEO, global distributor.

To start, we constructed a set of conceptual supply chain models. In simple terms, these were used to assess at a high level what a realistic set of options might look at. It very quickly became obvious that the inventory investment, based on the number of products, makes it very difficult to split the range over a large number of stock holding locations. This allowed us to constrain the model to a smaller number of options.

We then used segmentation analysis to split the range based on a series of characteristics, such as value, cube and weight, rate of sale and life cycle risk. This allowed us to further restrict the number of options into a more manageable set of options, again based on the criteria of cost, investment and service.

Finally, we ran the models to understand the optimum solution, balancing the costs and investment whilst meeting a minimum service requirement, then again with increasing service requirements to understand the

sensitivity. This resulted in a series of scenario outputs (each individually optimised), which could then be assessed against the overall scoring.

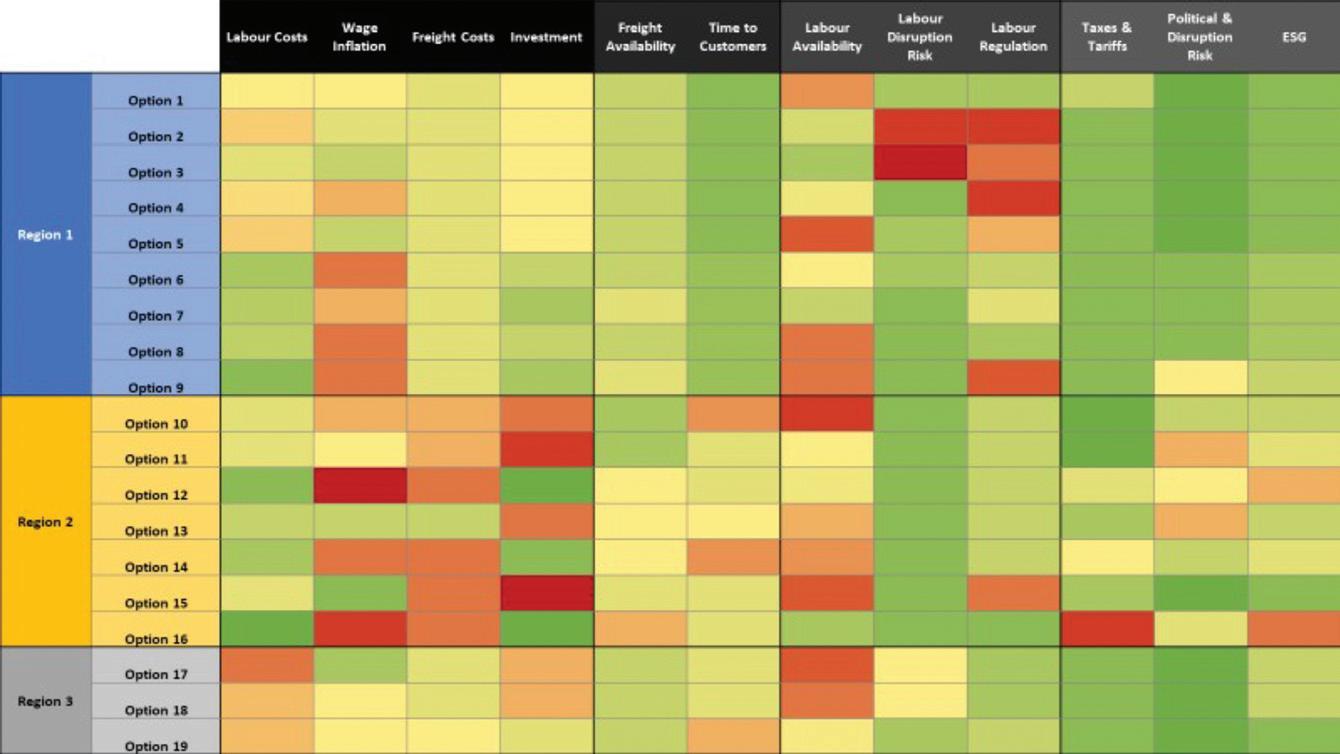

In parallel, we developed a series of ‘qualitative’ scoring areas, and then assessed each scenario on these. Some of these categories can take data driven inputs, such as taxes and tariffs and political and disruption risks. Others are more subjective, such as freight availability and some risk factors.

Figure 2 shows one of the elements of this evaluation, highlighting both quantitative and qualitative measures against a series of options.

Ultimately, it is important to recognise that there typically is not one optimum solution; different stakeholders will put a different focus on the different elements. It is therefore required to review both the analytical elements (where there may well be an optimum, but it depends on the inputs) and the softer or more qualitative elements.

BLENDING ART AND SCIENCE

The requirement to use non-numerical data does not mean that we should not use the optimisation models. Rather, it should remind us that these models can be very useful but need to be treated with a degree of caution: they are limited by their complexity, by the difficulty to get perfect data and by the fact that there are factors that are not in the model.

The key element is to take the models, ensure they represent the actual underlying problem and then to test the outputs, understand their sensitivity and to be very clear about other factors that are important decision criteria but may not be in the model.

Finally, it is also worth remembering that your competitors are running the same models. Sometimes, you can get a competitive advantage by doing something that may not be ‘optimum’ but allows you to differentiate yourself.

Designing supply chains is hard, but by combining the power of analytics with a real-world understanding of the limitations of the model, we can deliver results that are both cost effective, more environmentally friendly and with the right balance of service and risks.

Emile Naus is a Partner in BearingPoint. He has worked in supply chain across both operational roles and consultancy projects across the globe, with a background in analytics (https://www.linkedin.com/ in/emile-naus/). BearingPoint is a 5,000 strong consultancy with a focus on business and technology (www.bearingpoint.com).

IMPACT | SPRING 2023 17

it is important to recognise that there typically is not one optimum solution

FIGURE 2 EXAMPLE EVALUATION MATRIX

© BearingPoint

THE ROAD TO BETTER OUTCOMES

NEIL ROBINSON WELL OVER HALF A CENTURY HAS PASSED since an article in a management journal originally tackled what has come to be known as the vehicle routing problem. The world is a very different place today, which is why the challenges and impacts of addressing this increasingly complex issue have perhaps never been so significant.

Vehicle routing problems – otherwise known as VRPs – have been a focus of operational research for more than 60 years. They first appeared in an academic paper in 1959, when George Dantzig and John Ramser’s The Truck Dispatching Problem proposed an algorithm for organising fuel deliveries.

As Dantzig and Ramser noted, a VRP represents a generalisation of the travelling salesperson problem (TSP) – one of the most intensively studied puzzles in fields ranging from O.R. to theoretical computer science. As with the TSP, the challenge is essentially one of logistical optimisation.

Specifically, the aim is to maximise the efficiency of transportation operations for a fleet of vehicles based out of a designated hub. It was with this goal in mind that Dantzig and Ramser delineated what they called a ‘near-best solution’ for trucks moving between an oil terminal and a number of service stations.

IMPACT © THE OR SOCIETY 19

© Gorloff-KV/Shutterstock

It hardly need be said that much has changed since 1959. It is unlikely, for example, that the necessary calculations for successful responses to VRPs would now be ‘readily performed by hand’, as Dantzig and Ramser suggested. Ours is a much more complicated and interconnected world.

As a result, increasingly complex VRPs can now be found in numerous sectors –including distribution, travel, waste collection, tourism, healthcare and even humanitarian efforts. Moreover, they no longer revolve almost exclusively around cost considerations: environmental concerns must be taken into account as well.

Fortunately, O.R. has also come a long way. The work described here is a powerful illustration of how state-of-theart approaches to VRPs are now benefiting a wide array of stakeholders by enhancing the practices of businesses and organisations around the globe.

reasons why

A CHALLENGE DEMANDING TRUE EXPERTISE

More than a decade ago, following a request from a major charity, Güneş Erdoğan started working on what would become known as the VRP Spreadsheet Solver. Arising from a collaboration between five UK universities, the project recognised the growing difficulties facing real-world practitioners confronted by VRPs.

‘One of the reasons why VRPs fall within the academic domain of O.R. is that they’re extremely hard to solve,’ says Erdoğan, now a Professor of Management at the University of Bath. ‘Developing an algorithm for a VRP is a daunting undertaking and not for the faint-hearted.’

Among the principal hurdles is the dynamic retrieval of data from a geographic information system. The recurring costs of acquisition can be prohibitive, and even a

measure of in-house knowledge might be insufficient to draw on the consequent wealth of travel and distance data needed to visualise and compare potential solutions.

There are commercial software packages for VRPs, but these can present issues of their own. They must be integrated into existing software, and they are also likely to have a black-box component that protects their programmers’ intellectual property –that is, the algorithm that determines optimal routes.

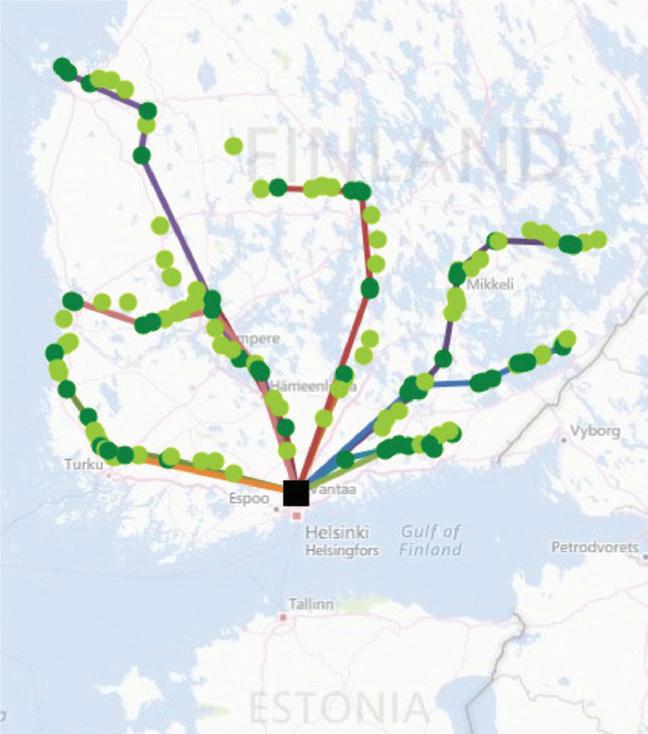

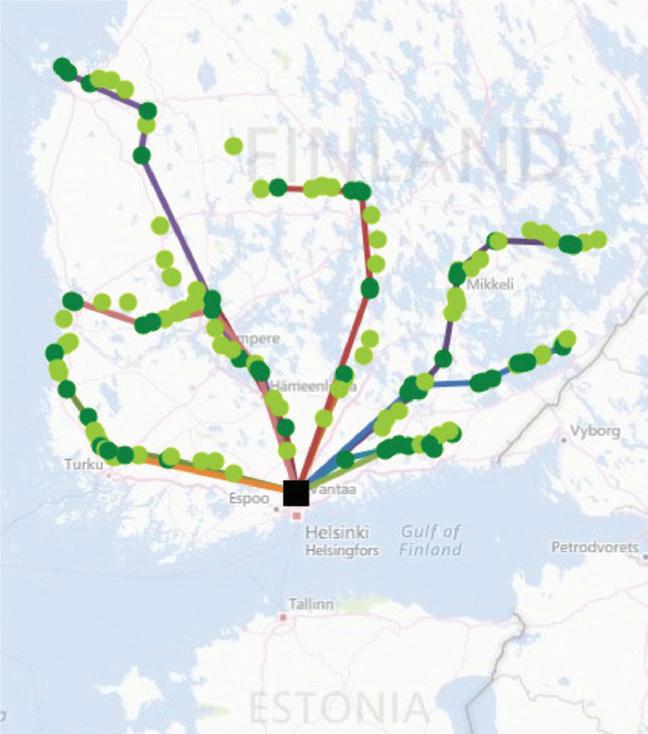

Erdoğan and the rest of the team sought to circumvent all these obstacles by making the VRP Spreadsheet Solver uniquely accessible, useable and flexible. The result: an open-source, easy-tounderstand-and-modify program with an interface in Microsoft Excel – arguably the standard software for small-to-mediumscale quantitative analysis the world over. An example of the output from the VRP Spreadsheet Solver for a tourism company based in Finland can be seen in Figure 1. Buses subcontracted by the company based in Helsinki pick up customers and return to the port.

The VRP Spreadsheet Solver was first released in a beta version in 2013. Its story was only just beginning. A year later, following his arrival at Bath, Erdoğan embarked on research that would eventually greatly expand its scope and functionality.

CYCLE OF IMPROVEMENT

In light of the general shift towards ‘greener’ urban transportation, one of the most common VRPs today is what is sometimes known as the Static Bicycle Rebalancing Problem. This refers to the challenge of how to most effectively redistribute the bikes used in a bike-sharing system.

Ideally, redistribution entails one or more centrally based vehicles picking up and delivering bikes in a way that ensures an optimum mix of bicycles and empty parking slots at every bike-sharing station in a town or city. Having accomplished this task, the vehicles then return to their depot.

‘There have been many initiatives to encourage users themselves to relocate bikes from areas of high supply and low demand to areas of low supply and high demand, but it’s still trucks that tend to do the job,’ says Erdoğan. ‘This can mean significant expense and a heavy CO2 footprint, which is why routing optimisation is acknowledged as key to reducing costs and mitigating environmental impact.’

In 2014, in collaboration with colleagues in the UK and abroad, Erdoğan set about developing an optimal algorithm for managing bike-sharing systems. Crucially, it encompassed those requiring several vehicles and station visits to achieve redistribution.

‘The demands of many large bikesharing systems simply can’t be satisfied by a single vehicle and a single visit,’ explains Erdoğan. ‘The involvement of multiple vehicles and multiple visits is much more representative of the real world, and it was important to reflect that.’

The algorithm was found to work for systems with up to 60 stations. Its success compelled Erdoğan to incorporate his new research into the design and operation of the VRP Spreadsheet Solver, which was duly transformed into a tool capable of generating substantial savings – sometimes amounting to hundreds of thousands of pounds – in a variety of sectors.

IMPACT | SPRING 2023 20

One of the

VRPs fall within the academic domain of O.R. is that they’re extremely hard to solve

FIGURE 1 THE VISUAL OUTPUT FOR A CASE STUDY IN THE TOURISM SECTOR (from Erdoğan, G. (2017): see below).

A GLOBAL SOLUTION FOR A GLOBAL PROBLEM

The updated version of the VRP Spreadsheet Solver was downloaded several thousand times after being made freely available on an academic website. Erdoğan now emails it directly to interested parties. To date, it has been used in countries including the US, Finland, Argentina, Turkey and Taiwan.

Its appeal may be especially manifest amid a post-pandemic commercial landscape in which concepts such as working from home, just-in-time logistics and all-round hyperconnectivity have become new normals. As Erdoğan points out, variants of the VRP are now emerging in any context where a pick-up or delivery service is performed.

Take, for instance, a non-profit organisation that provides at-home healthcare services in Istanbul. With three bases, around 90 vehicles and more than 3,000 patients, it has to visit around a thousand separate locations every day. In this case the VRP Spreadsheet Solver has helped address management concerns over the equal allocation of work.

The challenge for another corporate user was to optimise the distribution of food from its warehouses to its 45 supermarkets in central Taiwan. The VRP Spreadsheet

ENSURING FAMILIARITY AND FLOW

Familiarity and ease of use are among the VRP Spreadsheet Solver’s principal attractions from the perspective of businesses and organisations. The software’s Microsoft Excel underpinnings are key here.

For example, the program keeps data about the elements of a specific VRP in separate worksheets. These are then generated in sequence. The incremental flow of information between worksheets is shown in Figure 2, with the arrows signifying interdependencies.

Solver’s innate versatility and ease of use meant the company was able to adapt the program to perfectly suit its purposes.

One of the business’s senior managers later contacted Erdoğan, telling him: ‘Since you wrote your solver in Excel, its interface is familiar enough for nonprogrammers to use and change. We let real users modify your program to split large orders, match truck types to stores,

add multiple runs and generate reports.’ The feedback further highlighted distance savings of 30% and cost savings of up to 20% for perishable goods.

There has even been a throwback to the formative work of Dantzig and Ramser: like The Truck Dispatching Problem of 1959, the VRP Spreadsheet Solver has assisted the oil industry. A US-based firm reported savings of around $2 million between 2016 and 2020 after using the software to plot routes between wells for its fleet of 150 tankers.

THE BOTTOM LINE – AND BEYOND

‘The feedback we’ve received shows how widely and effectively this software can be applied,’ says Erdoğan. ‘On the strength of correspondence alone, we know the total savings made possible by the VRP Spreadsheet Solver so far run to millions of pounds. Maybe more so than ever, we also know VRPs are an issue for businesses and organisations all around the world.’

Data from Google Analytics underlines Erdoğan’s observations about the global

IMPACT | SPRING 2023 21

FIGURE 2 SPREADSHEET STRUCTURE OF VRP SPREADSHEET SOLVER (from Erdoğan, G. (2017): see below).

© ronstik/Shutterstock

A CLOSER LOOK AT THE VRP SPREADSHEET SOLVER CONSOLE

The first worksheet users encounter is known as the VRP Solver console. It stores information that is provided to the other worksheets.

As shown in Figure 3, the console is home to numerous parameters that define a VRP. These include the number of depots and customers, the number of vehicle types and the width of time windows. Users can also adjust settings around options such as the retrieval of data from a geographic information system and the time allowed to work on a problem.

Mindful of this truth, it is perhaps worth noting the final sentence of the abstract of Dantzig and Ramser’s trailblazing paper of 64 years ago. Having outlined their groundbreaking ‘near-optimal solution,’ the authors conceded: ‘No practical applications of the method have been made yet.’

It’s not just a question of producing better outcomes for companies and other organisations: it’s also a question of producing better outcomes for their stakeholders, including society as a whole

nature of modern-day VRPs. More than 25,000 people from 136 countries – the US, India, Turkey, Brazil, the UK, Colombia, Germany, Thailand, Canada and Indonesia foremost among them – viewed the VRP Spreadsheet Solver’s host page in the 40 months leading up to December 2020, while a YouTube tutorial video was watched over 70,000 times.

‘I think the bigger picture is vital here,’ says Erdoğan. ‘We’re living in an age when every business is seeking cost efficiencies and when corporate social responsibility and ESG – environmental, social and governance considerations – should be high on the agenda of any organisation. Together, these factors have brought VRPs into ever-sharper focus.’

It is the second of these concerns, particularly in the form of climate action, that really distinguishes the VRPs of today from those of yesteryear. So-called G-VRPs – Green Vehicle Routing Problems – have quickly become a cornerstone of research in this area, with a focus on minimising emissions, noise pollution and

accidents. Less distance and less duration frequently translate into benefits that extend far beyond the bottom line.

We’re living in an age when every business is seeking cost efficiencies and when corporate social responsibility and ESG –environmental, social and governance considerations – should be high on the agenda of any organisation

FOR FURTHER READING

The same could hardly be said of Erdoğan’s research. ‘We feel our work is genuinely making a difference in lots of ways,’ he says. ‘It’s not just a question of producing better outcomes for companies and other organisations: it’s also a question of producing better outcomes for their stakeholders, including society as a whole. For me, that goes to the heart of what O.R. should be all about in the 21st century.’

Neil Robinson is the managing editor of Bulletin, a communications consultancy that specialises in helping academic research have the greatest economic, cultural or social impact

Bulhões, T., A. Subramanian, G. Erdoğan and G. Laporte (2018). The static bike relocation problem with multiple vehicles and visits. European Journal of Operational Research 264: 508-523.

Dantzig, G. and J. Ramser (1959). The truck dispatching problem. Management Science 6: 80-91.

Erdoğan, G., M. Battarra and R. Wolfler Calvo (2015). An exact algorithm for the static rebalancing problem arising in bicycle-sharing systems. European Journal of Operational Research 245: 667-679.

Erdoğan, G. (2017). An open-source spreadsheet solver for vehicle routing problems. Computers and Operations Research 84: 62-72.

IMPACT | SPRING 2023 22

FIGURE 3 VRP SOLVER CONSOLE SPREADSHEET (from Erdoğan, G. (2017): see below).

PLANNING GSK’S FACTORIES TO MEET THE GROWING DEMAND FOR MEDICATIONS

GSK IS A GLOBAL BIOPHARMA COMPANY with a purpose to unite science, technology and talent to get ahead of diseases. GSK aims to positively impact the health of 2.5 billion people over the next 10 years. Its bold ambitions for patients are reflected in new commitments to growth and a step-change in performance.

GSK prioritises innovation in vaccines and specialty medicines,

maximising the increasing opportunities to prevent and treat disease. At the heart of this is its R&D focus on the science of the immune system, human genetics and advanced technologies, and its world-leading capabilities in vaccines and medicines development. It focuses on four therapeutic areas: infectious diseases, HIV, oncology, and immunology.

IMPACT © 2023 THE AUTHORS 23

GIOVANNI GIORGIO, NATASHA ZHELTOVSKAYA, PETER RILEY AND JACOB WHYTE

© GSK

THE FEED TEAM’S ROLE

GSK’s Global Capital Projects organisation looks after the worldwide company capital investment in the pharma supply chain (new manufacturing equipment and new facilities). Within this organisation the Front-End Engineering & Design (FEED) team focuses on the initial stages of design and business case. Projects usually go through three key phases: business analysis, feasibility and concept selection. In each phase we assess the strategic business requirements and propose a selection of engineering solutions to address the business need. By the end of the concept selection process a single solution gets endorsed by the business and progresses into the delivery phase.

Modelling and analytics activities often play a big role in the front-end phases of capital projects, as they help the business to understand what information is critical. Knowing how big the demand for a certain product is going to be affects what size the facility should be, the kind of equipment that should be used for the production and what the production cycle is going to be like. This requires lots of different scenarios being modelled in a highly sophisticated network of dependencies and calculation of their impact on the investments the company must make. The budgets of the potential capital projects can range from £10m to £500m and the timeline for the plans needs to be made for the next 5 to 15 years. The FEED team uses modelling and simulation to understand how to optimise such investments by phasing them while still minimising the risks.

THE CHALLENGE

In 2020, the GSK FEED team was faced with planning for a new

biopharma facility in Italy. To plan for such a large investment, the team had to carry out key work to support the business case, which involved developing the design concept and establishing the optimal level of resources to satisfy ten years of forecasted commercial demand. This meant that the team needed to calculate how many machines were needed and what the technology of the machines should be, which machines should be bought, and decide on their operational regime, because the type of the machine will dictate how they can be used operationally.

Product forecasting and demand fluctuations have always represented a big challenge for pharma companies, especially during the design of a new manufacturing line or plant. Most of the time the potential new products are still in development undergoing clinical trials and years ahead of the commercialisation launch. Getting the right product mix, coordination and optimisation of resources such as machines, operators, materials, etc. are some of the challenges that GSK face operationally. To address this, there was a need for a model that could be used to inform key aspects of the business case. It had to capture all the required complexity while being fast enough and flexible enough to answer the business question.

A SOLUTION THROUGH COLLABORATION

GSK asked Decision Lab to develop a decision-making tool to support the business case. Decision Lab is an award-winning tech company with a lot of experience in building highly complex models that aid decisionmaking in a range of sectors, including healthcare, aviation, infrastructure, logistics, and defence and security. GSK and Decision Lab have worked

on projects previously and knew that they could work across the two organisations in one unified effort, which would be necessary for this complicated project.

Decision Lab’s solution was to develop a simulation model for the planned new production line. If able to accurately represent the operations of the facility, this model would allow GSK to test the future production line virtually and investigate its boundaries by evaluating several “what if” scenarios. It would provide an understanding of the factors that impact production capacity and operating costs. It would also give specific answers to key questions: how many machines they should buy, what technology these machines will use, and what their operational regime (number of operators, shift patterns, etc.) should be?

The FEED Team used the model to generate hundreds of plausible scenarios and test many different demand forecasts, equipment technologies and size, quantity of key equipment and allow them to understand the true operational bottleneck

Decision Lab and GSK technical experts worked closely on this project, in a highly collaborative way. It was a cross-functional effort involving about thirty GSK contributors across several countries and disciplines. We needed to involve different specialist teams to guide us on aspects of the data input, and this expertise was embedded into the model. The fact that the model condensed the knowledge and the requirements of about 20 active contributors from different disciplines says a lot about the value the

IMPACT | SPRING 2023 24

development team gained in terms of engagement, knowledge transfer and decision support. The collaborative approach helped the design and production teams gain a holistic view of the capacity and operation as we uncovered the process logic and operational metrics. It also offered a high level of engagement within GSK, aided knowledge transfer and built confidence in the model and the insights it provides.

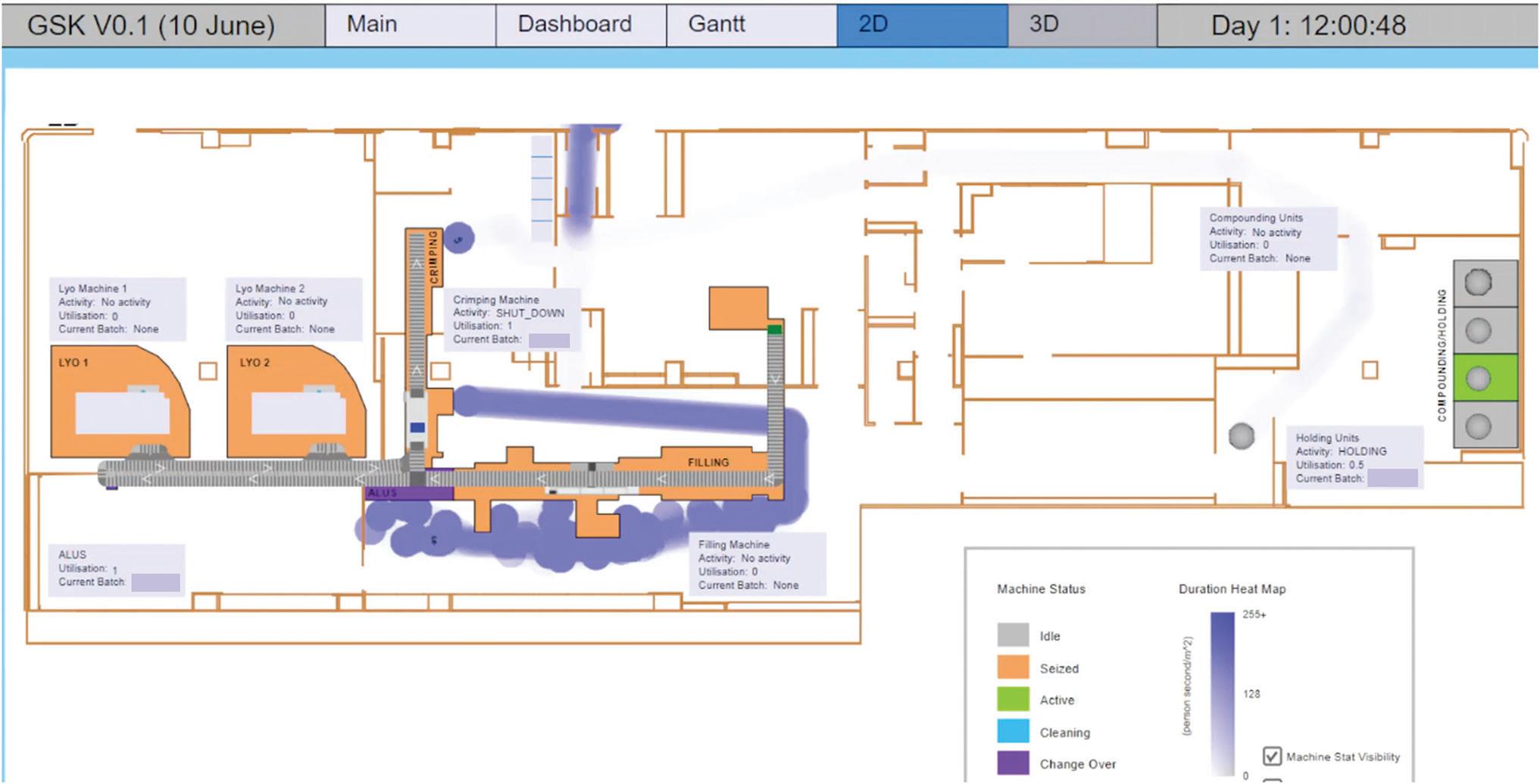

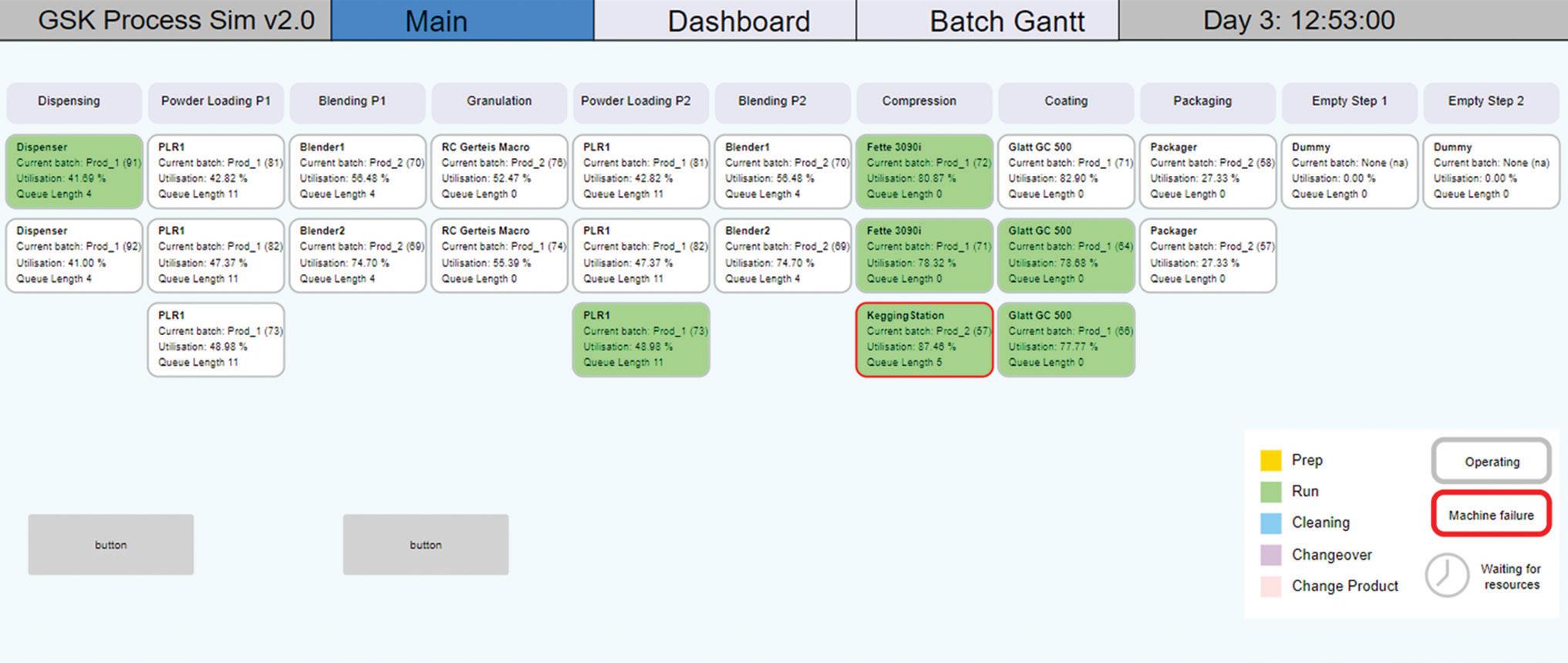

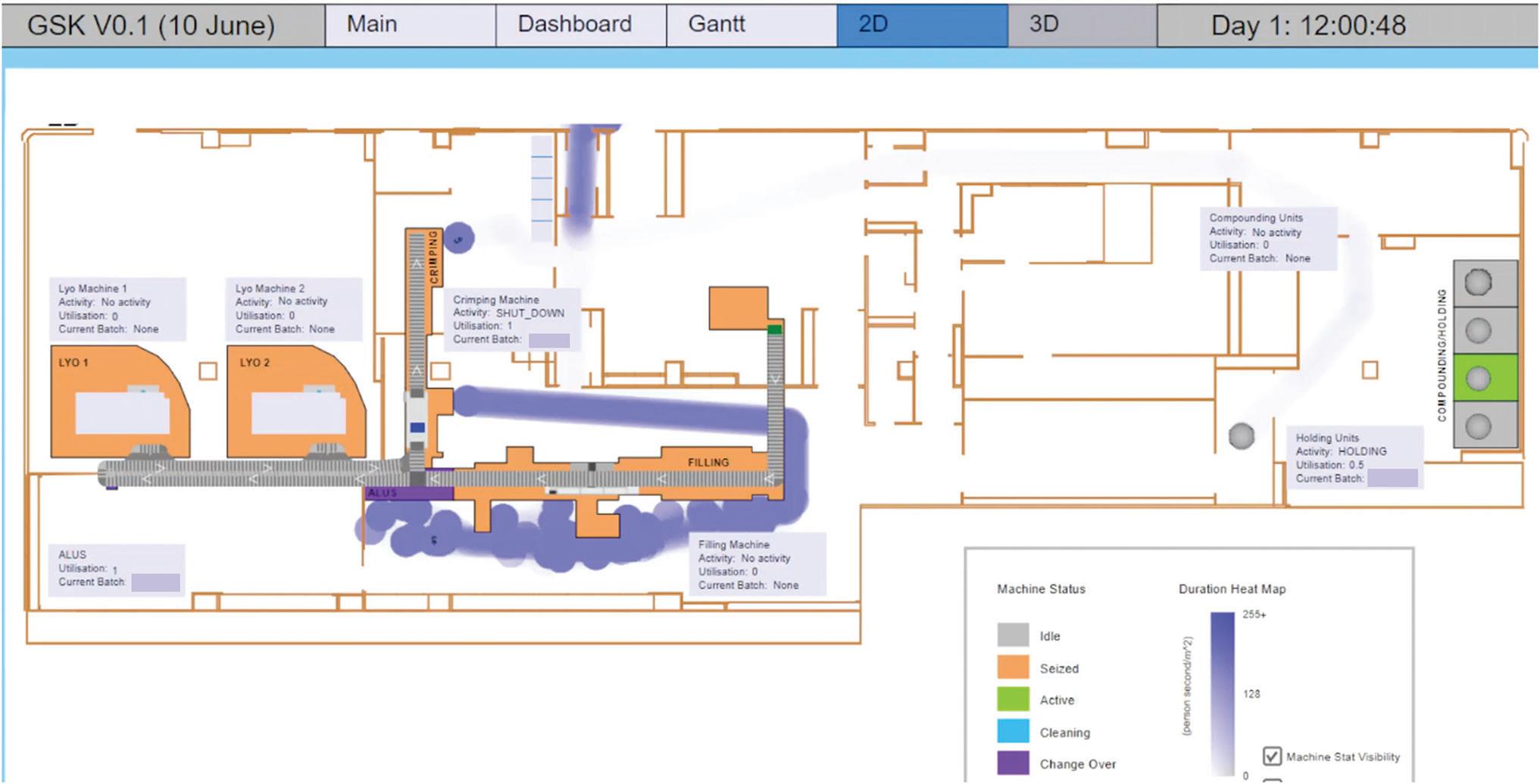

The model itself is a discrete event simulation where the user specifies the demand as a sequence of product batches and specifies a series of process steps that each batch may need to go through. For each process step the batch is assigned equipment that will perform the process. Equipment may have to be cleaned between batches. The model tries to process all the batches as quickly as possible and that the machines are utilised as equally as possible. Figure 1 shows the 2D view of the model, providing information on

each machine’s current batch, activity and utilisation, as well as worker movement. The model is flexible and allows the user to control many different variables such as maximum length of queues, frequency and length of equipment failures, the number of available resources etc. The model produces a comprehensive set of outputs which the user can use to infer where the processing bottleneck is and if the number of machines/resources they selected is optimal. Figure 2 shows the 3D view of the model, providing batches on the conveyor belt as they go through different machines and workers moving around the environment. “The model has been fundamental in defining the right sizing of the facility as well as exploring the different product mix taking into account several variables (batch size, product type, shutdowns, change overs) by running multiple scenarios and sensitivities analyses. It also offers scheduling optimisation opportunities

that can’t be achieved via traditional approach, leading to a more efficient use of the facility“: Site Strategy Lead (Italy).

The FEED Team used the model to generate hundreds of plausible scenarios and test many different demand forecasts, equipment technologies and size, quantity of key equipment and allow them to understand the true operational bottleneck. The model has been used in different stages of demand and this continues.

A SECOND APPLICATION: ORAL SOLID DOSE (OSD)

GSK has a well-established facility in the south of England and was considering whether to invest in updating to increase capacity at the site. The biopharma filling facility model had proved its utility for informing a business case, so GSK asked Decision Lab whether the model could be adapted. Decision Lab had

IMPACT | SPRING 2023 25

© Decision Lab

FIGURE 1 2D VIEW OF THE “ITALIAN” MODEL

intentionally developed the biopharma filling facility model in a flexible way, so that it could be applied more generally. This, in accordance with the FEED philosophy of reusing parts of design work on multiple projects (to accelerate the studies), meant that GSK could engage Decision Lab to adapt the model.

For the facility in England, we needed to carry out a study into how much new equipment was needed for the required increased capacity. This would involve running scenarios where we would consider different numbers of equipment and its performance to determine what the minimum number was to deliver the desired capacity. It's important to capture the key factors that influence the KPIs, including shift patterns, product mix, machine failures, etc. They will contribute to a more realistic solution – closing the simulation to real-world gap – and will enable the model to adapt to any future changes in business processes (which

won’t require an entirely new model). In the facility, the product is moved between the machines in containers, so we had to be able to calculate their number, also the space for these containers, and how much resources are needed to run the facility. Another question of interest was about budgetary efficiencies, e.g. if we don’t buy a certain machine, how much capacity can we deliver? Basically, we want the model to allow us to identify the breaking points in the system.

The model provided a great starting point for us in terms of rapidly developing a model from a proven capability. We could add the required features and functionality to a working model that would allow us to run the range of scenarios that were needed. It also gave us greater confidence in the output. When you’re unsure about a model’s reliability, you might add a buffer to account for errors – for example buying extra machines which may or may not be needed – but of

course using this safety buffer in the plan costs money. So, minimising this buffer by having a more accurate prediction can create a huge saving.

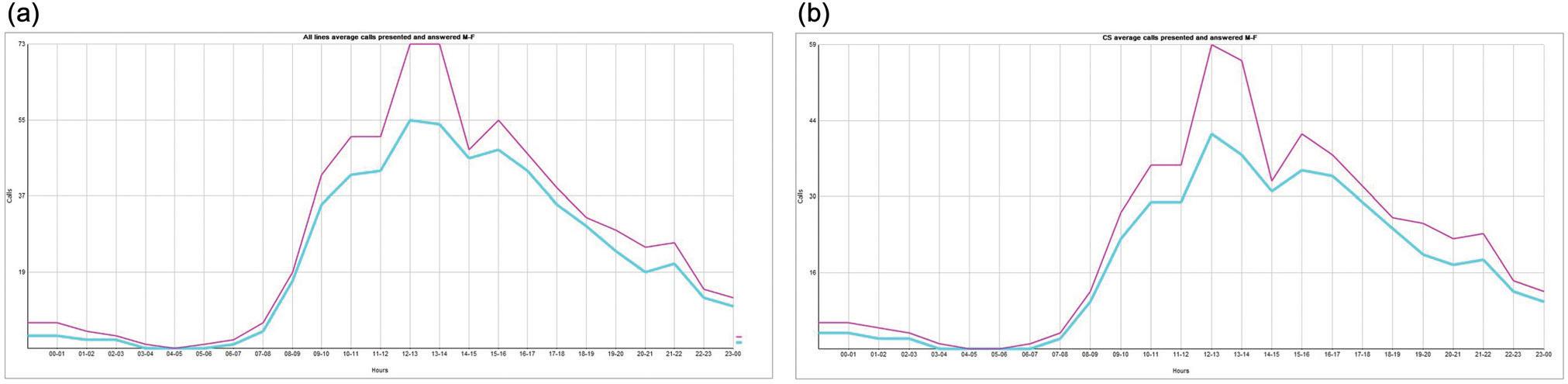

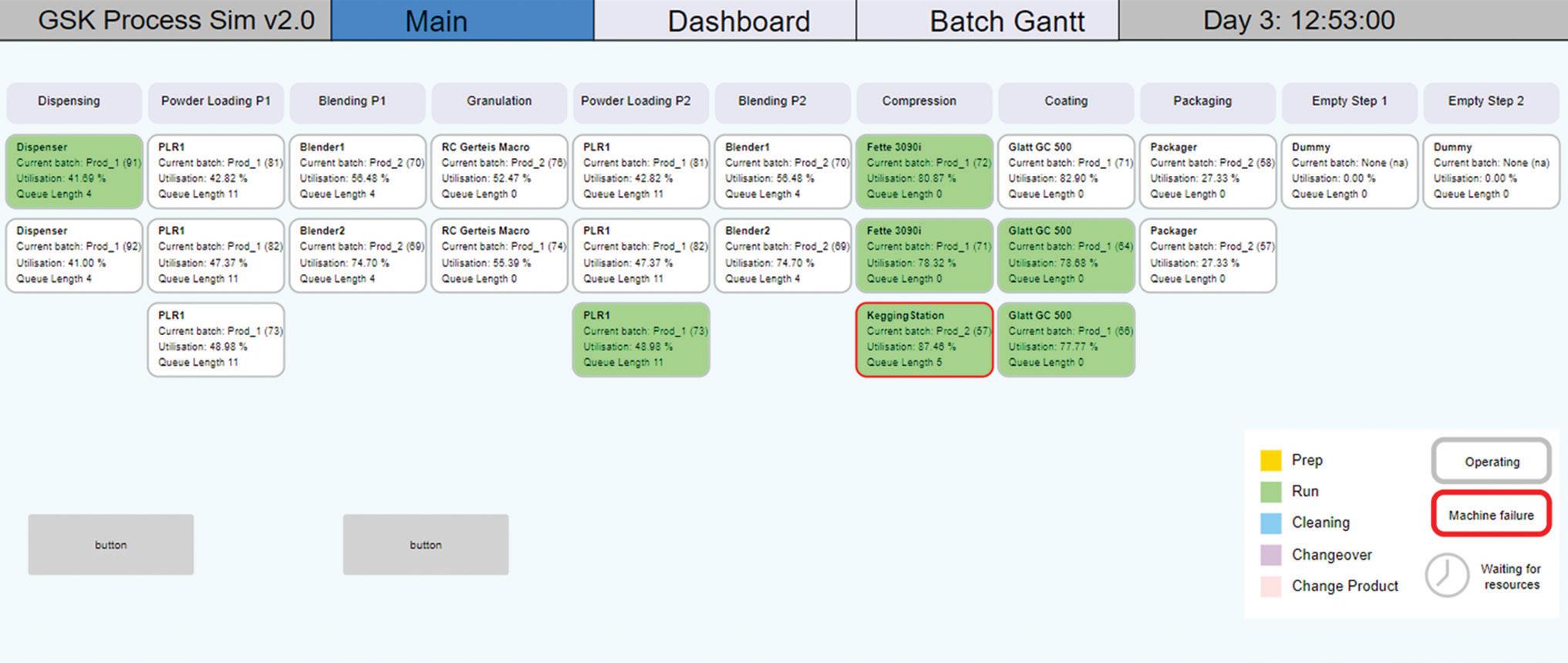

Figure 3 shows the main runtime visualisation of this model, providing information about each machine, which batch to which they are currently assigned, their utilisation and queue size. We also had the benefit of a preexisting Excel-based model for the site in England. We realised that this could not be used for the study because it could not handle the complexity involved with multiple SKUs, multiple ways to process the product between different machines, interdependencies between parameters, etc. However, it did provide useful insight into the current facility and processes, and a baseline for some model intercomparisons.

With the increasing pressures, our timelines often become shorter. In the past we could have had six months to run a study but now we only have two months. Therefore, time becomes a

IMPACT | SPRING 2023 26

© Decision Lab

FIGURE 2 3D VIEW OF THE “ITALIAN” MODEL

critical factor that often drives decisions about the tools that we put into action. Having a baseline model we can quickly adapt was crucial to this project, and we were well placed that we had developed the biopharma filling facility tool as a generic model that we can use for different projects and requirements.

The model for the OSD facility allows us to see how the change of different inputs influences how long it takes to process all the demand and how efficient the equipment and resource usage is. For example, with a particular configuration, what percentage of the demand for this drug are we going to meet or even if we have some spare capacity. Our focus was very much on capacity and the equipment required to deliver it, as this has major cost implications. However, in the future we can expand it to consider aspects such as figuring out the best space layout that would allow for the best operations.

The model for the OSD facility allows us to see how the change of different

inputs influences how long it takes to process all the demand and how efficient the equipment and resource usage is

There are also other ways in which we can develop it, and these reflect the stages of the site itself. To build the facility, we need to plan it first. This was why we developed the model to enable us to conduct the study to work out the design that allows the site to meet the demand as cost effectively as possible. While the site is being built, the model can be further adapted so that it can be used to refine the details of the plan or address detailed issues that come up, and this could be especially important if unexpected changes are required or there are demand fluctuations that could impact the solution.

Once the site is built, the model, with minor enhancements, can become an operational support tool. It could be used to help make decisions by providing modelling results to complex questions for specific situations that arise, and

some may even require optimisation solutions. Some examples are optimising batch production, predicting capacity over the next six months.

WHAT THE FUTURE MIGHT HOLD

Decision Lab and the FEED team have developed a modelling capability to support the business case for large scale investment in pharma production facilities, one in the facility in Italy, and one in the UK. As part of this process, GSK has assessed the top benefits of the modelling activity and identified that it:

• Results in a faster approval timeline –the trust in the modelling outputs has smoothed the stage gate approval of the concept and allowed faster moves into the next project phase.

• Provided depth and breadth in its analysis, with its ability to evaluate over 200 different business scenarios in a short amount of time.

• Provided a high level of confidence in the amount of equipment required

IMPACT | SPRING 2023 27

FIGURE 3 THE MAIN RUNTIME VISUALISATION OF THE “SOUTHERN ENGLAND” MODEL

© Decision Lab

for the new production line that ultimately led to capital expenditure reduction of 20%.

The collaboration made a material difference to the business and both the Italian facility and UK facility went to the construction phase. Our tool has the capability to deliver continued value to the project so that in the future it will be possible to further evaluate capacity requirements as function of the demand forecast variability. The model also has the capability to be extended to people and material flow for the final operational layout.

Together, the GSK FEED project team and Decision Lab have laid the foundation for the future. Over the years we developed a new methodology that now can be applied and scaled to most of the pharma processes and investments. This will deliver speed and efficiency in the FEED and a greater confidence for the decision makers in the business. The next challenge will be to further develop

such models so that they can be used by the operational team once the facility has been commissioned and handed over. That could lead to even greater benefit to the business, reducing cost of goods, inventory, and many other KPIs.

Over the years we developed a new methodology that now can be applied and scaled to most of the pharma processes and investments

Giovanni Giorgio is a Senior Digital Engineer at GSK. Giovanni is a Chemical Engineer with 15+ years of experience in the pharmaceutical industry (R&D and Global Manufacturing), with a strong background in API chemical & process engineering and with an intensive and diversified experience acquired in different business units. Giovanni is currently leading the modelling and analytic strategy in the Front-End Engineering and Design team in Global Capital Projects. He has developed an interest in applying

advanced modelling techniques to solve complex business problems.

Natasha Zheltovskaya is Decision Lab’s head of marketing. She has worked in marketing for more than 15 years, leading the brand development work for some of the world top brands in retail, fast moving consumer goods (FMCG) and technology.

Peter Riley is a Principal Consultant at Decision Lab where he is leading the simulation team. Peter has built agentbased, discrete event and system dynamics simulations for a wide range of industries, including pharmaceutical, retail and defence.

Jacob Whyte is a Simulation Consultant at Decision Lab. His background is in computer science. Jacob develops digital twins and simulation models for clients and is working on a major simulation model for creating synthetic data for AI model training.

IMPACT | SPRING 2023 28

CHANGING THE ROLE OF LOGISTICS

BRIAN CLEGG

THIRD-PARTY LOGISTICS (3PL) PROVIDERS specialise in handling inventory for other firms. But back in 2013, Panalpina World Transport took part in a meeting at Cardiff University that would result in taking a whole new look at the way that stock is handled. Panalpina later became part of the DSV group (at the time of writing, the third largest 3PL firm in the world, with over 60,000 employees), but the Knowledge Transfer Partnerships established with Cardiff have continued to provide fresh Operational Research insights for the business.

Heading up the Cardiff side of the partnership is Aris Syntetos, Distinguished Research Professor of Operational Research and Operations Management and holder of the DSV Chair of Manufacturing and Logistics. After a first degree in business administration at the University of Piraeus (at the time, the Graduate School of Industrial Studies) in Athens, Aris went on to take an MSc in quality management at Stirling University, where forecasting became a particular interest for him, then a PhD in Operational Research at Brunel

IMPACT © THE OR SOCIETY 29

© DSV

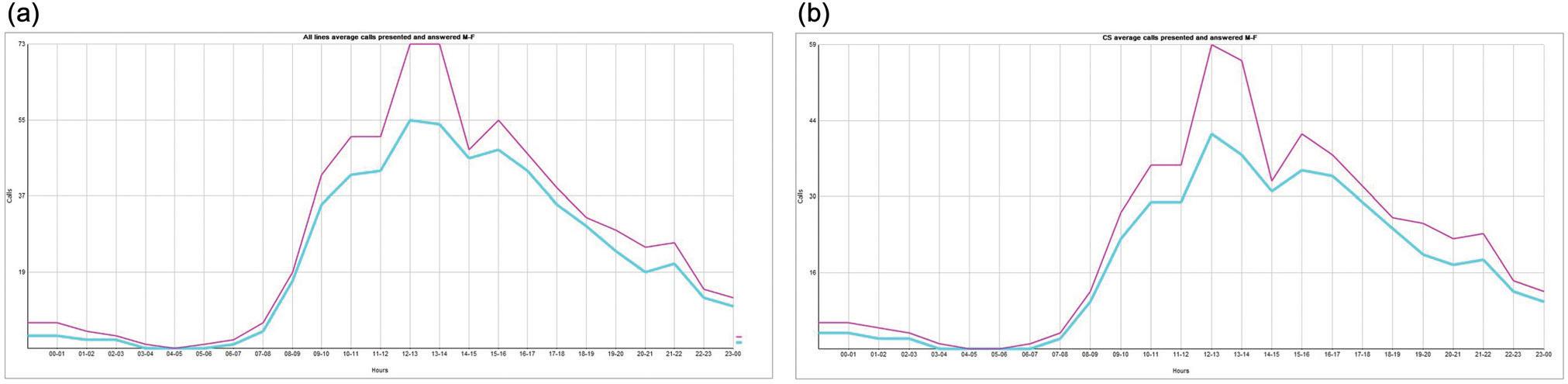

University. Now at Cardiff University, Aris heads up the PARC Institute of Manufacturing, Logistics and Inventory, based in the Cardiff Business School (CARBS) of Cardiff University. It was started with direct funding from Panalpina (hence the PAnalipina Research Centre) as a joint industryuniversity partnership. The initial interest was inventory forecasting.