ORO Editions

Publishers of Architecture, Art, and Design

Gordon Goff: Publisher www.oroeditions.com info@oroeditions.com

Published by ORO Editions.

Copyright © 2023 Frank Jacobus, Brian M. Kelly, and ORO Editions.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including electronic, mechanical, photocopying of microfilming, recording, or otherwise (except that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the US Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press) without written permission from the publisher.

You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Editors: Frank Jacobus and Brian M. Kelly

Book Design: Brian M. Kelly

Project Manager: Jake Anderson

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 First Edition

ISBN: 978-1-957183-68-8

Color Separations and Printing: ORO Group Inc.

Printed in China

ORO Editions makes a continuous effort to minimize the overall carbon footprint of its publications. As part of this goal, ORO, in association with Global ReLeaf, arranges to plant trees to replace those used in the manufacturing of the paper produced for its books. Global ReLeaf is an international campaign run by American Forests, one of the world’s oldest nonprofit conservation organizations. Global ReLeaf is American Forests’ education and action program that helps individuals, organizations, agencies, and corporations improve the local and global environment by planting and caring for trees.

ARTIFICIAL. INTELLIGENT. ARCHITECTURE.

Edited by Frank Jacobus and Brian M. Kelly

05

INTRODUCTION

Frank Jacobus and Brian M. Kelly

13 CONVERSATION WITH ANDREW KUDLESS

Frank Jacobus and Brian M. Kelly

29 UNACCEPTABLE AGGREGATIONS

Matt Baran

43 PARAMETRICISM IN THE AGE OF AI

Tim Fu

55 ETHEREAL DIMENSIONS IN NATURE

Sara Asif

69 IMAGE LAUNDERING: ODD FACADES

Brian M. Kelly

163 ERROR TO INNOVATION

Kevin P . McClellan

175 GETTING WHAT YOU ASK FOR

Joshua Ver million

187 LESS THAN PERFECT

Jean Jaminet

201 POLYMORPHOUS PLAY

Frank Jacobus

213 SENSATIONAL CONCEPTS

Randall Teal

227 SLIPPING ARCHITECTURE

Kaveh Najafian

241 BESTIA EX MACHINA

Jason Vigneri-Beane

255 POST INDUSTRIAL RENAISSANCE

Adrian L. Keytton

269 GOTHIC SPOLIARE

Dustin White

281 ROBOT HISTORIAN ON KELLEYS ISLAND

Karl Daubmann

297 IN CONCLUSION: CHAT WITH CHATGPT

Frank Jacobus and Brian M. Kelly

Ria Bravo

81 THE ARTIFICIAL SKETCHBOOK

DEEP LEARNING IN URBAN HEALTH

ARTIFICIAL IDEALS: POETIC ITERATION

David Alf 95 LOOKING FOR THE PERFECT IMAGE Stéphane Bauche 109

David Newton 121

Andrew Clarkson

THE OTHER SIDE

133 HELLO FROM

Michael Chapman

OF

147 PATTERNS

INTERIORITY

Image by Frank Jacobus

Frank Jacobus and Brian M. Kelly

Image by Frank Jacobus

Frank Jacobus and Brian M. Kelly

The design world is undergoing profound changes. At the time of this writing, a little over a year ago we were introduced to a group of visualization tools that give us a glimpse into the future. This view is revelatory, and yet creates more questions than answers. What happens when ideas can be enacted with near immediacy? What happens when tools are fluid, when they feel natural, when they are not an impediment to design thinking? What happens to design if we can produce work one-hundred times faster than we can today? What happens to our aesthetic palettes when we experience a continuous exaggeration of new forms? This feels like a paradigm shift, a transformation of how we will act in the world.

We have heard the fears, sensed the discomfort, and we empathize. We believe Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools, those presented in this book as well as AI more broadly, will affect your daily life radically. But likely their effects will be gradual. We are already having debates about where, how, and when these tools should be used; there will be many more. As the debates continue so will algorithmic and computing advancement that increases AI’s effectiveness. Tool after tool will be injected with AI components. Eventually, AI will be so pervasive, so omnipresent, that the argument won’t be about AI, it will be about nuanced characteristics within AI that haven’t yet been invented or named. For years there will also be debates about how these tools are changing society. Many will argue that our past selves are much better than our present ones, as they lament a world they see slipping away. Eventually AI will be so pervasive it will be silly to call it AI; it will simply be the way the world operates.

Introduction

5

Just like those who long for the past, the first-generation users of AI visualization tools presented in this book will also likely long for the tool as it was, rather than what it becomes. Are we all guilty of this to some extent? We live in a rapidly advancing technological age that is always in a state of becoming. Our grandparents experienced a radically different world as youngsters than they did in old age. The airplane was an infant when our grandparents were born; sliced bread and car radios didn’t exist at all. As Kim Stanley Robinson famously stated, we are the primitives of an unknown civilization. Instead of clamoring for the past, one could claim these tools as an inevitability and therefore focus on ethical use, on use toward the betterment of society. As primitives of the next civilization, we can become energetic builders of the future’s foundation.

This book represents an early look at work being done with AI visualization tools and how that work might predict future use scenarios. One might read the chapters in this book as horizon scanning, loose predictions of how the tools might evolve. The book begins in conversation with Andrew Kudless, a leading design voice and early adopter of AI visualization. Interestingly, perhaps even comically, the book closes in conversation with OpenAI’s ChatGPT, wherein we ask some of the same questions we asked Andrew. We see this as a litmus test of AI’s current capacity and perhaps also as a time capsule, like a Polaroid picture now being partly interesting for its own sake regardless of pictorial content.

Between these interviews we have a series of chapters written by a diverse group of authors. These chapters are treated as diptychs supported through a theory and application framework about a specific topic of interest in AI production. The theoretical outline in each chapter acts as a provocation evolving from and evident through the author’s work. The intention here was for the authors to be as reactive as they were reflective. We have faith in the intuitive, instinctive judgments that arise from this space.

The book is loosely divided into five themes: Prompt Craft, Process, Happy Accidents, Form and Sensation, and History’s Future. These are based on natural ideas we saw emerge through the editorial process rather than anything scripted or requested from the authors. A brief summary of the chapters and author ideas is as follows:

6

Prompt-Craft

In Unacceptable Aggregations, Matt Baran discusses the taboos and boundaries that many AI engines put in place to control how the tools is being used. Baran goes on to circumvent these rules through the careful stitching together of words that bypass the firewalls, and through the intentional co-opting of work by other artists, challenging long-held architectural conventions. All this with the noble hope of giving voice to that which often lurks in the silence and saving us from the boogeyman.

In Parametricism in the Age of AI, Tim Fu uses the work of Zaha Hadid Architects (ZHA) to address style within the sphere of AI text prompting. Fu discusses the nature of prompt craft and the necessary specificity involved in moving beyond the name of specific designers when trying to capture their precise stylish identities when using AI tools. Fu then goes on to discuss his work, which uses a hybrid parametric to AI workflow to achieve stunning results.

Sarah Asif explains how one can core into nuanced language within specific domains to advance prompt craft and achieve beautiful visual results in Ethereal Dimensions in Nature. The forms that Asif generates makes one wonder about the future use of AI tools in the field of biomimicry.

In Image Laundering: Odd Facades, Brian Kelly discusses copyright law and intellectual property issues with respect to AI visualization tools. He compares the use of these tools to Hip Hop sampling and collage, questioning the legal issues that may eventually arise as a result of their global explosion. Viewing his own work through this lens, he experiments with sampling exercises using canonical examples, considering the practice a type of co-authoring.

Process

The next section of the book tackles several process issues that arise with the use of AI tools. In The Artificial Sketchbook, David Alf walks the reader through several craft issues with respect to Midjourney (MJ) as a design tool. Alf discusses how he uses the tool as a digital sketchbook that he can always carry with him. Alf discusses the pleasures of quick ideation and what it means for design futures that ideas can become so rapidly visualized.

7

In Looking for the Perfect Image, Stéphane Bauche discusses her introduction to MJ, explaining how it has transformed the way she works and thinks. Bauche explains how we might never find the specific image we are looking for, how errors within the tool often yield incredible results, and how curation plays an enormous role within AI visualization tools.

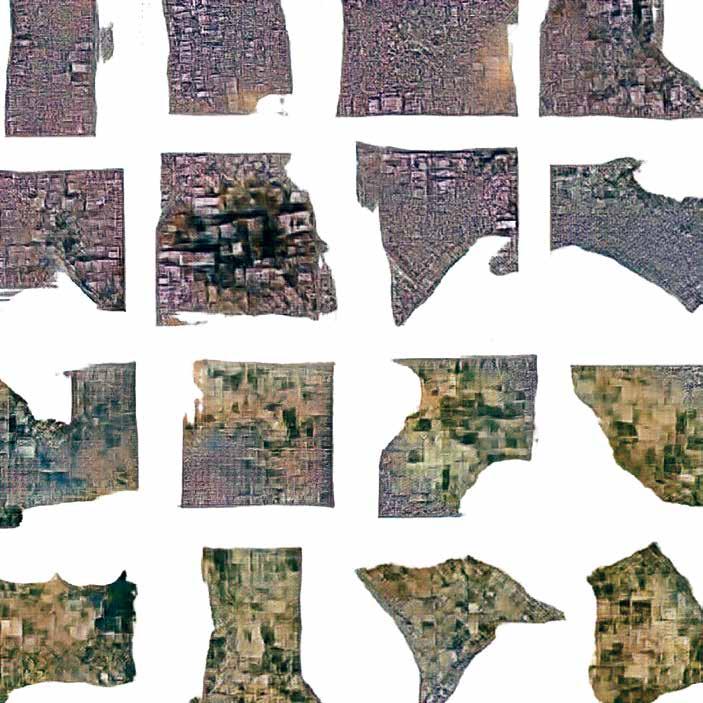

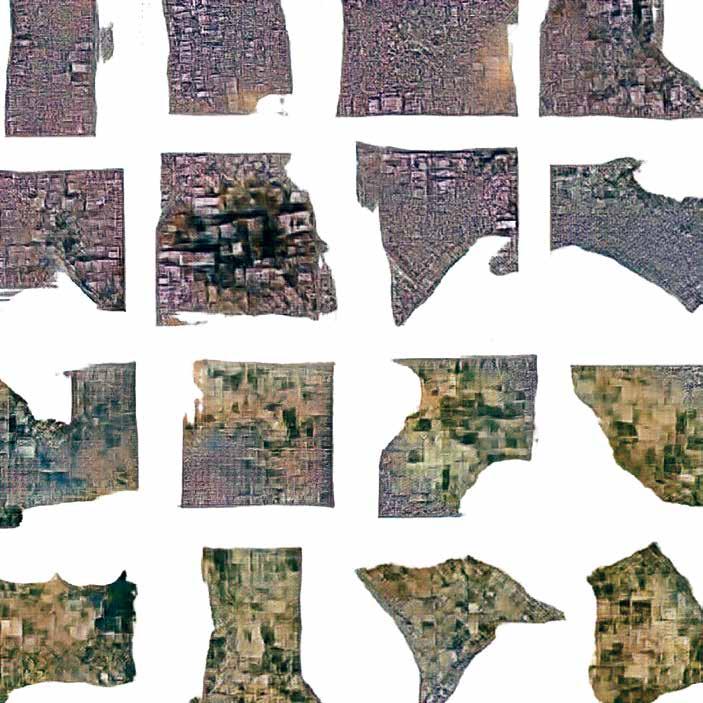

In Deep Learning in Urban Health, David Newton discusses the use of AI visualization as a way of positively affecting urban health issues. Newton explores big data, Generative Deep Learning (GDL), and other approaches digging into their analytical and computing abilities. He goes on to give examples as to how GDL, especially diffusion-based models, could be used to alter our understanding of the city, urbanism, and its effect on human health.

In Artificial Details: Poetic Iteration, Andrew Clarkson compares AI visualization tools to the Sumerian alphabet. Just as the alphabet transformed human relations and technological advancement, Clarkson makes the claim that AI tools will similarly have profound impact on architectural process and production.

In Hello from the Other Side, Michael Chapman discusses how AI visualization tools have open up access to troves of architectural precedent for designers to mine at will. He examines the history of architectural drawing and traditional design approaches. He goes on to describe his process, which attempts to find a collaboration between traditional drawing and AI production.

Happy Accidents

The next section of the book tackles the idea of the accident. Those who we have spoken to who have used AI visualization tools have generally enjoyed the tool doing the unexpected. There is a pleasurable subversion of self-consciousness that occurs when using these tools.

In Patterns of Interiority, Ria Bravo discusses the limitations of the known in traditional design processes and how AI engines overcome this with a kind of accidental ambiguity. Bravo cites AI’s misunderstanding, its tendency to misalign form and content, as one of its greatest assets. Bravo relates the process of working with AI engines to Surrealist automatic processes, which

8

allow us to tap into the subconscious mind, to explore ideas we haven’t fully worked out. She positions AI as a door to the land of fantasy and dream.

In Error to Innovation, Kevin McClellan discusses the rise of AI visualization tools as a natural evolution of the modernist technological ethos. He questions the tool in its current state and speculates on how it may best evolve in the years to come. McClellan examines the nature of error in these systems, both encoded error and that which arises from the tool’s use.

In Getting What You Ask For, Joshua Vermilion discusses the oracle like wisdom of AI visualization tools who interpret, or often misinterpret our words to great effect. Vermillion is interested in the chance discoveries made by these tools. To this end, he examines prompt-crafting and the relinquishing of design control within AI environments.

In Poorly Trained Models, Jean Jaminet examines the motel and its characterized artificiality. He cites a strange alignment between contemporary built environment perception and machinelearning processes. He provides the above as context for the need for what he terms poorly trained models, which amplify the tensions between the artificial and the real.

Form and Sensation

In the fourth section of the book the authors focus on form and sensation. The rise of AI visualization tools signal an exaggeration of form and a need for new theory related to this change. In Polymorphous Play, Frank Jacobus leads this section by defining form and discussing how it hasn’t been properly theorized in a contemporary context. He provides a theory of form and a way of viewing AI tools as instruments of play that will transform the way we design.

In his chapter Sensational Concepts, Randall Teal discusses AI image production in relation to Deleuze’s notion of concept. Teal indicates how AI can quickly be used to create expressive images that garner empathetic connections for the viewer. As a part of this argument Teal cites how the AI visualization outputs deal directly in sensation, bypassing the need for more literal translations of effect.

9

In Slipping Architecture, Kaveh Najafian discusses automation, creative authorship, AI visualization best practices, and the potential evolution of AI tools generally. Najafian questions the nature of what he calls impossible structures, constructs so outlandish they become beautiful dreams but impossible realities. Najafian also discusses the potential dissolution of style due to the exaggeration of forms prompted with the use of AI visualization tools. Finally, he speculates about the nature of architecture as a discipline and how that might change due to the use of these tools.

In Bestia Ex Machina, Jason Vigneri-Beane explores the idea of the emergence of hybrid tectonic creatures that create vast troves of digital genealogies. In Vigneri-Beane’s AI outputs these creatures live between categories of being, signaling mysterious futures grown from the past, yet still unpredictable.

History’s Future

The fifth and final section of the book involves a topic we call history’s future. Within this section are authors who speculate about future uses of AI tools, or filter histories through AI tools to imagine new futures. In Post-Industrial Renaissance, Adrian Keytton imagines the future of AI and discusses how AI-aided design has the potential to unlock creativity and innovation at unprecedented levels. Keytton imagines how AI tools will enable the development of more humanistic and sustainable designs. In addition, he discusses how the speed of AI tools will allow space for dialogue where tighter time constraints may have prevented that in more traditional design approaches.

In Gothic Spoliare, Dustin White compares the process of using AI visualization tools to the use of spolia in Roman cities of the late empire. Spolia are repurposed stones extracted from ancient buildings and used in newer ones. AI diffusion models are trained on what he thinks of as digital spolia, existing digital content pillaged for new needs. He then goes on to describe how he uses digital spolia to reinvent neo-Gothic constructs.

10

In Robot Historian on Kelleys Island, Karl Daubmann tells the story of the future condition of a present place, Kelleys Island, wherein a robot historian explores the now abandoned island and visually documents the findings. This chapter beautifully conveys how AI visualization engines can be used to quickly imagine whole worlds. The project that Daubmann takes on seems to perfectly fit the use of the AI visualization engine in its current state.

AI visualization tools signal great change for the design industry. We are already seeing them being used with incredible dexterity and creativity. Because tools such as Midjourney, DALL-E, and Stable Diffusion are text-based, they have become a democratizing agent in design, universally accessible to all. Users who may have been excluded from certain design domains, like parametricism for instance, due to the time-consuming nature and inherent complexity of these tools, are now included and producing wonderful work as a result. This is undoubtedly the beginning of a new era in design. This book represents a first look at AI’s potential impact on architectural practice and production. As mentioned earlier, we think of the book as a window into this world, but also as a litmus test. We will be looking back in ten to fifteen years, anxious to examine the ideas of our past selves, still wondering what the future might hold.

11

Frank Jacobus and Brian Kelly, spring 2023

Image by Frank Jacobus

Image by Frank Jacobus

CONVERSATION WITH ANDREW KUDLESS

Frank Jacobus and Brian M. Kelly

This interview was taken from a recording done on January 20, 2023. The written transcript has been edited from the original for ease of reading.

Brian Kelly: With the introduction of Artificial Intelligence [AI] platforms such as Midjourney (MJ), Stable Diffusion, DALL-E, etc., the accessibility of working in AI space has been high in the past nine months and has seen significant growth recently. There seems to be a wave of participation analogous to the parametric wave of the early 2000s, albeit with higher participation perhaps due to less training required for involvement. Parametricism took a lot more training to enter that domain and, therefore, to be a leader in the field who was pushing its agenda. I’m curious about your thoughts regarding this comparison?

Andrew Kudless: I think it’s an interesting question. I was just talking about this today to someone. [We’ve gone through an evolution of] learning how to draft in the nineties, to struggling with drafting and not being very good at it, and then into parametricism, etc. My career has basically been about learning these new systems as they came about. It kind of mirrors the transition that the discipline has gone through from analog to digital. I think what’s interesting in relation to AI right now is that the whole trajectory up to now has mostly been about making more and more complex interfaces. On one hand, certain things made complex interfaces more accessible, like Grasshopper made parametric design more accessible. But the thinking behind it was still complex. On a conceptual level, to understand what to do in Grasshopper or in Revit, e.g., you must have a pretty good understanding of what you want to do. What’s the design? What’s the

Image by Matthew Baran

Image by Matthew Baran

Unacceptable Aggregations

Matt Baran Baran Studio Architecture Instagram: @baranstudioarchitecture

Unacceptable Aggregations

In a recent interview with Forbes magazine, Sam Altman, the CEO and one of the founders of OpenAI, asserts, “of all the things I’m proud of OpenAI for, one of the biggest is that we have been able to push the Overton Window on AGI in a way that I think is healthy and important, even if it is sometimes uncomfortable.”1

AGI, or artificial general intelligence, is now an acceptable subject for discussion, albeit with a large amount of fear and trepidation. However, the actual deployment of AI and the subsequent content of its work product are still highly limited. To truly discover what AI is capable of and discover new models of architecture and architecture process, we will need to break through the existing taboos.

The Boogeymen

To begin with, AI embodies the taboo of theft. Whether text or image generation, the available subject matter is work that has been produced by others. While this is on the one hand limiting (if we rely completely on AI in its current form, no new content will be generated, only the recycling of previous content) and on the other hand endless (there is virtually no limit to new configurations of old content), the ethics of taking intellectual property and reverse engineering it in the first place are still being contested.2

36

Figure 2

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 3

37

Figure 6

38

Figure 7

Figure 9

Figure 10

Figure 8

Figure 9

Figure 10

Figure 8

39

Figure 11

40

Figure 12

Figure 14

Figure 15

Figure 13

Figure 14

Figure 15

Figure 13

41

Figure 16

Figure 10

Figure 8

Figure 9

Figure 10

Figure 8

Figure 9

62

Figure 7

Figure

Figure

11

63

Figure 7: Focusing on materiality - Fur juxtaposed with organic facade / Figure 8: Inspired by the the form of marine creatures / Figure 9: prompt crafting inspired by vines and creeper networks / Figure 10: Inspired by blooming flowers / Figure 11: Plumage inspired form study (images courtesy Sarah Asif)

64

Figure 12

Figure 13

Figure 13

65

Figure 12: Inspired by Mycelium networks / Figure 13: Inspired by lichen networks (image courtesy Sarah Asif)

106

Figure 17

Figure 18

Figure 18

107

Figure 17: Glass Dwellings / Figure 18: Cantilever Dwellings (images courtesy S. Bauche)

Deep Learning in Urban Health

David William Newton University of Nebraska

Introduction

The built environment has played a significant role in human health throughout history. The spatial regimes of cities, neighborhoods, and buildings have played an especially significant role during pandemics. The strategy of social distancing to prevent the spread of disease is first and foremost a spatial strategy. The emergence of the global pandemic caused by corona virus disease 19 (COVID-19) has further underscored this link, while also bringing new urgency to the problem of developing a more complete picture of the relationships that the built environment may have with human health. How can the disciplines of urban planning and design develop insight into how the built environment impacts health? How can these disciplines develop improved generative models for the design of the built environment that can improve health?

A Deluge of Data

Every day a vast network of remote sensing platforms (e.g., satellites and aircraft) document Earth’s changing morphology, weather patterns, chemical flows, and the ever-expanding footprint of the built environment. Remote sensing image data from these platforms in the form of photographs, light detection and ranging (LIDAR) images, radio detection and ranging (RADAR) images, hyperspectral images, and thermal images document change across Earth’s surface over days, months, years, hours, and seconds—generating terabytes of data daily. The size of these datasets makes their analysis difficult and labor intensive if done manually. Advances in automated pattern recognition in the field of machine learning, however, are allowing these image-based datasets to be efficiently processed and analyzed—providing insight into a

158

Figure

14

Figure 15

Figure 15

159

Figure 14-15: Endless virtual interior space inspired by Peter Cook’s city landscapes (images courtesy Ria Bravo)

Figure 19

Figure 17

Figure 18

Figure 16

Figure 19

Figure 17

Figure 18

Figure 16

160

Figures 16-19: Inflated interiors: investigating how engorged enclosures are occupied and activated by the body and through augmentation of bodily uses; representational reference: Jean-Paul Jungmann’s Dyodon Pneumatic House (images courtesy Ria Bravo)

Figure 21

Figure 22

Figure 20

Figure 23

Figure 21

Figure 22

Figure 20

Figure 23

161

Figure 20-23: Inflated interiors: investigating how engorged enclosures are occupied and activated by the body and through augmentation of bodily uses; representational reference: Jean-Paul Jungmann’s Dyodon Pneumatic House (images courtesy Ria Bravo)

Image by Kaveh Najafian

Image by Kaveh Najafian

Slipping Architecture

Kaveh Najafian Contingency Plans Instagram: @contingency_plans

It has been more than two decades since AI has become the undisputed champion in chess. Multiple engines, as AI is called in chess, have the game under their dominance with big enough advantage that no grandmaster even bothers to challenge them anymore. Although, with different methods, all chess engines aim for one goal: hunting for the next best move in the game in order to inflict maximum damage. They are the ultimate tactical players with zero psychological involvement with the opponent, nor with the conditions in which the game happens.

However, with the rise of AI in chess, the game has not lost its appeal, but it has actually thrived since then. Chess engines are being used as tools for teaching, game analysis, and inventing chess variants. New tactics and variations have been added to all stages of the game and many moves that were counted as futile and pointless before the engines are now an essential part of every grandmaster’s repertoire of moves, in a way that it has become almost impossible to advance in chess without learning from the engines.

On the other hand measures have been taken in order to safeguard games against cheating by having a computer referee. In both on-board and online tournaments, cheaters get banned based on a consensus among the community of the players on how to regulate the use of AI in chess.

In creative industries like architecture and design the presence of AI essentially means automation in two different aspects: The first is the automation of the workflow in development and realization of a building or a product. AI can considerably improve BIM models, it can help

create more organic connection between the development of 2D documents and 3D models, or greatly optimize the way we represent a building or product via rendering and animation. This is the aspect that sits very well in line with the role that computers played since the beginning of their utilization in both disciplines. Everybody who is involved in architecture or design is well aware of this aspect and is expecting to see more automation as technology evolves.

But then comes the disruption. The second aspect involves the automation of developing ideas and concepts for a project. Here the presence of AI technically affects a very small crowd, but it poses a challenge to what is central to both disciplines’ character: creative authorship.

Text to image AI applications are currently at the forefront of AI involvement in producing potential concepts for architecture and design projects. As someone might expect, what they can provide at their current stage of development is not particularly useful for developing real life projects. The images are noisy, too detached from reality, and somehow very limited in aesthetics. Also, there seems to be in an unbreakable consistancy with the rest of the pool of images generated by the same software in terms of visual characteristics, regardless of the content and structure of the prompt.

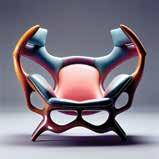

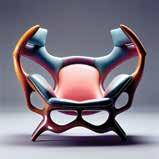

Nevertheless, AI-generated images can still be an unrivaled source of inspiration. The overall unpredictability of the AI approach toward the use of geometry and material and its total lack of subjectivity toward design in general results in some of the most ingeniously crafted images that have ever existed. The abundance of ideas that can be obtained through an unlimited number of iterations can be very helpful to design. As an example, I produced more than 4,000 images of mostly wooden lounge chairs based on two separate prompts in Midjourney in the span of almost three weeks. Then I sifted through that trove of iterative variations and up-scaled around 800 images, only based on design potentials; and in the end extracted around 100 images that could be counted as very well-conceived renderings of loosely functional chair designs. That’s impossible to achieve with any human capacity. In the example above, almost all aspects in which AI challenges creative authorship are traceable.

228

AI vs. the Visionary

Visionary proposals are the means for architects to challenge conventions in design and construction, align themselves and the discipline toward the future and break free from the constraints of the mundane. They challenge our notions about the nature of reality itself and encourage us to imagine new possibilities beyond the confines of our everyday experience.

AI, however, has pushed the concept of impossible structures into a void. AI technology used in applications such as Midjourney is often based on neural networks that are trained to recognize patterns and generate new content based on those patterns. Like a young child who is still learning about the world and hasn’t yet developed a full understanding of how things “should” look, the AI constantly generates images that are unexpected or unconventional. Imagine a painting by a super-talented four-year-old. It is impossible to say if that painting is real or not, not because of poor technique or its lack of accuracy, but simply because most of the time it is not intended to be real as we understand the reality. By removing the intention behind the creation, it becomes impossible to refer to what has been generated to real life examples. In the world of AI-assisted art and design, everything by default can be everything, everything is possible but all in an impossible latent world in which subjectivity does not exist.

If the impossibility of a design or architecture to be realized could by itself be a source of inspiration for us, by the advent of AI, impossible structures are going to be the new norm with no meaningful connection to the physical world.

AI vs. Style

Developing a distinctive visual style is a key to prominence in architecture. To achieve that, architects need to identify their core values and design principles that differentiate their work from others in order to create a consistent aesthetics that runs through all their projects. Moreover, they need to adapt and modify the style according to the specific needs of each project, which requires a high level of versatility, resourcefulness, and creativity.

229

Successful styles often gain followers who are inspired by the original designer or architect’s work and who want to create designs that incorporate similar design principles, aesthetics, and techniques. As these followers adapt and evolve the original style, they carry it through time and give it a chance to take on new forms and develop in different directions. The process of adapting and evolving a design style is often influenced by changes in technology, cultural trends, and social attitudes. As these factors change over time, the style can also evolve to incorporate new materials, techniques, and forms that reflect the current cultural landscape.

In AI-assisted imagery though, style is a magic spell to cast at will. AI applications like Midjourney dissolve the hierarchical structure that defines different styles in relation to each other, in favor of a horizontal undifferentiated landscape of mere ingredients that can be called for by the users of the software applications via prompting. One can ask for a skyscraper made of the great wave of Kanagawa, Mark Rothko style; software picks up all the ingredients and generates a series of images in a soup of a style, which is effectively the product of training variables and biases.

If prior to AI, creating a piece of architecture or design in a certain style had any sort of implication, it does not anymore, and as a result it cannot be the link that once connected generations of architects through similarities in their work. On the other hand, AI style lacks the uniqueness and individuality that were the hallmarks of traditional styles, as it is generated by algorithms, without any real intention behind it.

AI vs. Disciplines

AI-assisted software applications have the potential to dissolve the borders between different fields of the creative industry, which on one hand enables new forms of collaboration and creativity and on the other hand would result in many job titles to be removed all together. The writer of children’s book stories can use a text-to-image AI tool to generate the illustrations or at least reference images of the book by themselves. A senior copywriter can use a text-to text AI tool to generate a pile of concise-enough copies for an account without relying on a team of junior copywriters. Or an architect with a very small background in furniture design can produce thousands of viable options for a simple wooden lounge chair with no help. Of course the change

230

would first come to non-collaborative fields like writing or painting, but more interdisciplinary fields like architecture or film making are going to be affected in the same way.

Based on changes on the job market, university majors are also going to be subject to drastic changes. AI can help students to replace focusing on one field of study and spending years in order to learn necessary skills to join the market, with an opportunity for them to cultivate their ideas across multiple disciplines without being bogged down by hassles of learning about specific details and technicalities in each discipline. Also in the future, the graduates of computer sciences would form an even larger portion of the work force in creative industries, which is inherently a step toward more homogeneity in design approaches.

These three factors would permanently change the face of architecture and design as we know them. AI is going to cast a very long shadow over human creative authorship. It is muddying the water by becoming the go-to-tool for generating a litany of sophisticated visionary but rather irrelevant and out of context depictions of architecture and design, which in practice would most probably mean losing even more ground to mere standard buildings and products. I am not claiming that AI is going to replace creative designers, at least not in the short run, but it clearly has the capacity to undermine the principles upon which genuine ideas used to be born. Therefore, we need to find new ways of thinking outside the box and to redefine the box itself with new ways to express our ideas through architecture and design. In the meantime, it is going to be a total loss for whoever sits out during this transition period.

231

Figure 2

Figure 2

232

Figure 1

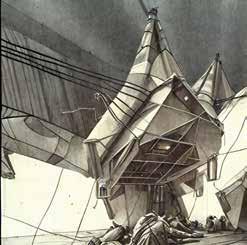

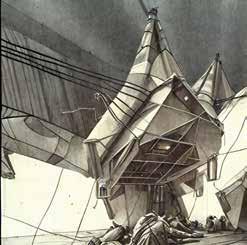

Figure 1-4: Images from Flying Versailles series generated by Midjourney. As an epitome of decorative architecture in Europe and the peak of the French baroque, Versailles palace counts as a “natural habitat” for Midjourney.

(images courtesy Kaveh Najafian)

Figure 4

Figure 1-4: Images from Flying Versailles series generated by Midjourney. As an epitome of decorative architecture in Europe and the peak of the French baroque, Versailles palace counts as a “natural habitat” for Midjourney.

(images courtesy Kaveh Najafian)

Figure 4

233

Figure 3

234

Figure 5

Figure

Building facade transformations. In the world of AI-assisted art and design, everything by default can be everything, everything is possible but all in an impossible latent world, in which subjectivity does not exist.

(images courtesy Kaveh Najafian)

5-6:

5-6:

235

Figure 6

236

Figure 7

understanding of how things

look, the AI constantly generates images that are unexpected or unconventional. (images courtesy Kaveh Najafian)

Figure 7-8: Images from Louhi Lounge Chair series. Like a young child who is still learning about the world and hasn’t yet developed a full

“should”

Figure 7-8: Images from Louhi Lounge Chair series. Like a young child who is still learning about the world and hasn’t yet developed a full

“should”

237

Figure 8

Author Biographies

Frank Jacobus, AIA, Frank Jacobus, AIA, is a licensed architect in the State of Texas and a professor at Penn State University. Over the course of his academic career he has taught studios at all levels of the curriculum ranging from design thinking in the introductory core, integrated design, and fifth-year options. Frank’s research focus involves form and empathy, perception, design thinking, and theory of the made object. His previous book projects include The Making of Things, The Visual Biography of Color, and Archi-Graphic: An Infographic Look at Architecture

Brian M. Kelly, AIA, is an NCARB-certified, licensed architect in the State of Nebraska and an associate professor of architecture at the University of Nebraska. He teaches studios at all levels of the curriculum ranging from design thinking in the introductory core to design research studios in the Master’s program. Brian’s research focus is broadly investigating the agency of authorship in the design process, specifically interrogating copyright and appropriation within software applications.

303

Image by Frank Jacobus

Frank Jacobus and Brian M. Kelly

Image by Frank Jacobus

Frank Jacobus and Brian M. Kelly

Image by Frank Jacobus

Image by Frank Jacobus

Image by Matthew Baran

Image by Matthew Baran

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 3

Figure 9

Figure 10

Figure 8

Figure 9

Figure 10

Figure 8

Figure 14

Figure 15

Figure 13

Figure 14

Figure 15

Figure 13

Figure 10

Figure 8

Figure 9

Figure 10

Figure 8

Figure 9

Figure

Figure

Figure 13

Figure 13

Figure 18

Figure 18

Figure 15

Figure 15

Figure 19

Figure 17

Figure 18

Figure 16

Figure 19

Figure 17

Figure 18

Figure 16

Figure 21

Figure 22

Figure 20

Figure 23

Figure 21

Figure 22

Figure 20

Figure 23

Image by Kaveh Najafian

Image by Kaveh Najafian

Figure 2

Figure 2

Figure 1-4: Images from Flying Versailles series generated by Midjourney. As an epitome of decorative architecture in Europe and the peak of the French baroque, Versailles palace counts as a “natural habitat” for Midjourney.

(images courtesy Kaveh Najafian)

Figure 4

Figure 1-4: Images from Flying Versailles series generated by Midjourney. As an epitome of decorative architecture in Europe and the peak of the French baroque, Versailles palace counts as a “natural habitat” for Midjourney.

(images courtesy Kaveh Najafian)

Figure 4

5-6:

5-6:

Figure 7-8: Images from Louhi Lounge Chair series. Like a young child who is still learning about the world and hasn’t yet developed a full

“should”

Figure 7-8: Images from Louhi Lounge Chair series. Like a young child who is still learning about the world and hasn’t yet developed a full

“should”