The new French generation

Mirecourt, cradle of French lutherie

Pierre-Alexandre Bellest

Simon Burgun

Bastien Burlot

Thomas Dauge

Bertrand Ligier

N° 21 - Spring 2023

English edition

The new French generation

Mirecourt, cradle of French lutherie

Pierre-Alexandre Bellest

Simon Burgun

Bastien Burlot

Thomas Dauge

Bertrand Ligier

N° 21 - Spring 2023

English edition

Santos

Hernández is undoubtedly Spain’s most creative and most important guitar luthier from the first half of the 20

It was Santos who in 1912, while working as a foreman at Manuel Ramírez’s workshop, built the famous guitar that would travel the world with Andrés Segovia for years to come. Santos’ instruments were also adopted by other great guitarists of his day, like Regino Sainz de la Maza, Luise Walker, Sabicas, Ramón Montoya, Niño Ricardo, Celedonio Romero, Abel Carlevaro… Through his loving hands, the beautiful sound attained by Antonio de Torres was brought into the 20

Founder and Publisher: Alberto Martinez

Art Director: Hervé Ollitraut-Bernard – Publishing assistant: Clémentine Jouffroy

French-Spanish translation: Maria Smith-Parmegiani – French-English translation: Meegan Davis

Website: www.orfeomagazine.fr – Contact: orfeo@orfeomagazine.fr

Over the course of my travels, I am often asked whether there is such a thing as a French style of lutherie, along the lines of the Madrid or the Viennese schools of lutherie. How to answer this question, given the disparities among guitars made by Robert Bouchet, Daniel Friederich and Dominique Field?

And yet… despite their strong individualities, all three luthiers share certain characteristics that are only seldom found in other schools: highest quality workmanship, artistic flair and homogeneity across all of the guitar’s details. All three luthiers satisfy these exacting standards.

In the new generation of French luthiers, those same characteristics come to the fore: they are all very disparate, with luthiers each following their own individual path, but they are all drawn to that same search for perfection and elegance, often upon the advice and encouragement of Dominique Field.

By way of introduction, I invite you to visit the town of Mirecourt, the cradle of French lutherie, and its marvellous museum. Enjoy.

Alberto Martinez

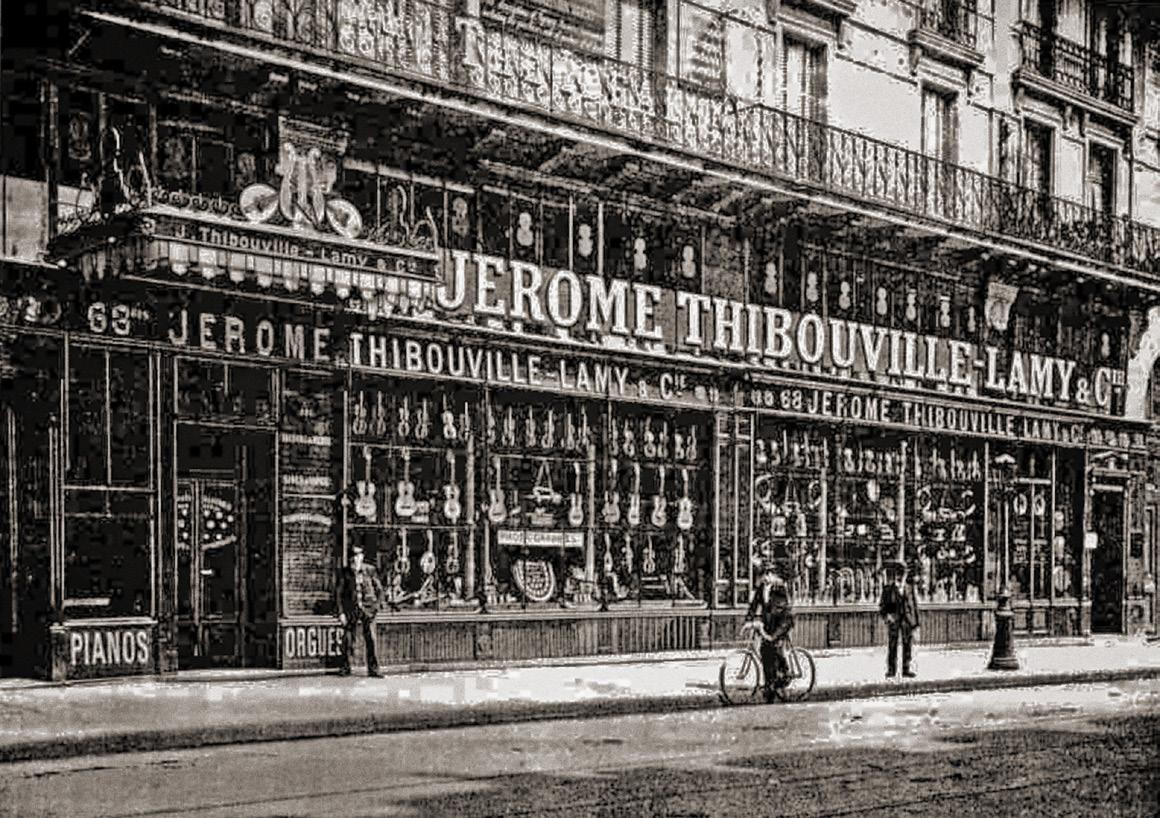

Whenever the name Mirecourt is uttered, whether in France or abroad, it immediately conjures the image of lutherie and, more specifically, of its most iconic instrument: the violin.

Mirecourt, a town that nowadays boasts a population of five thousand, is located in the heart of the Vosges plain. Already an established hub of craft and trade as of the twelfth century, lutherie and lace-making became the dominant occupations in the late seventeenth century. While there is mention of ‘violin-makers’ as early as 1606 in Mirecourt, it was in the late seventeenth century that musical instrument manufacture truly boomed. Official recognition of instru -

ment manufacturers as a “trade” at the behest of the Duchess of Lorraine, Élisabeth Charlotte, was validated by the charter signed on 15 May 1732. Since lutherie was now esteemed as a fully-fledged profession, complete with rules for transmission, its own policy and atypical commercial model, instrument-making in Mirecourt soared to new heights in the eighteenth century. Mirecourt’s luthiers honed their expertise by incorporating influences from Italian and German schools of lutherie.

In the mid-eighteenth century, bow-making became a separate profession from lutherie

The influence of Mirecourt’s lutherie – its instruments and its makers – started to spread well beyond the confines of the Lorraine region.1 It was from this time that Mirecurtien luthiers would

settle in Paris, or head abroad: initially to Belgium, the Netherlands, Italy and Spain, and then toward the end of the century, to England and Russia. In the nineteenth century, two of France’s master luthiers who both hailed from Mirecourt, Nicolas Lupot and Jean-Baptiste Vuillaume, established the French school of lutherie. The great bowmakers in France, including Pajeot, Pecatte, Voirin, Sartory, Fétique, Bazin and Ouchard, were all from Mirecourt.

From the early nineteenth century, the workshops in Mirecourt grew, accommodating more intensive and diversified production; not only catering for quartet lutherie, but also, among other instruments, guitars and hurdy-gurdies.

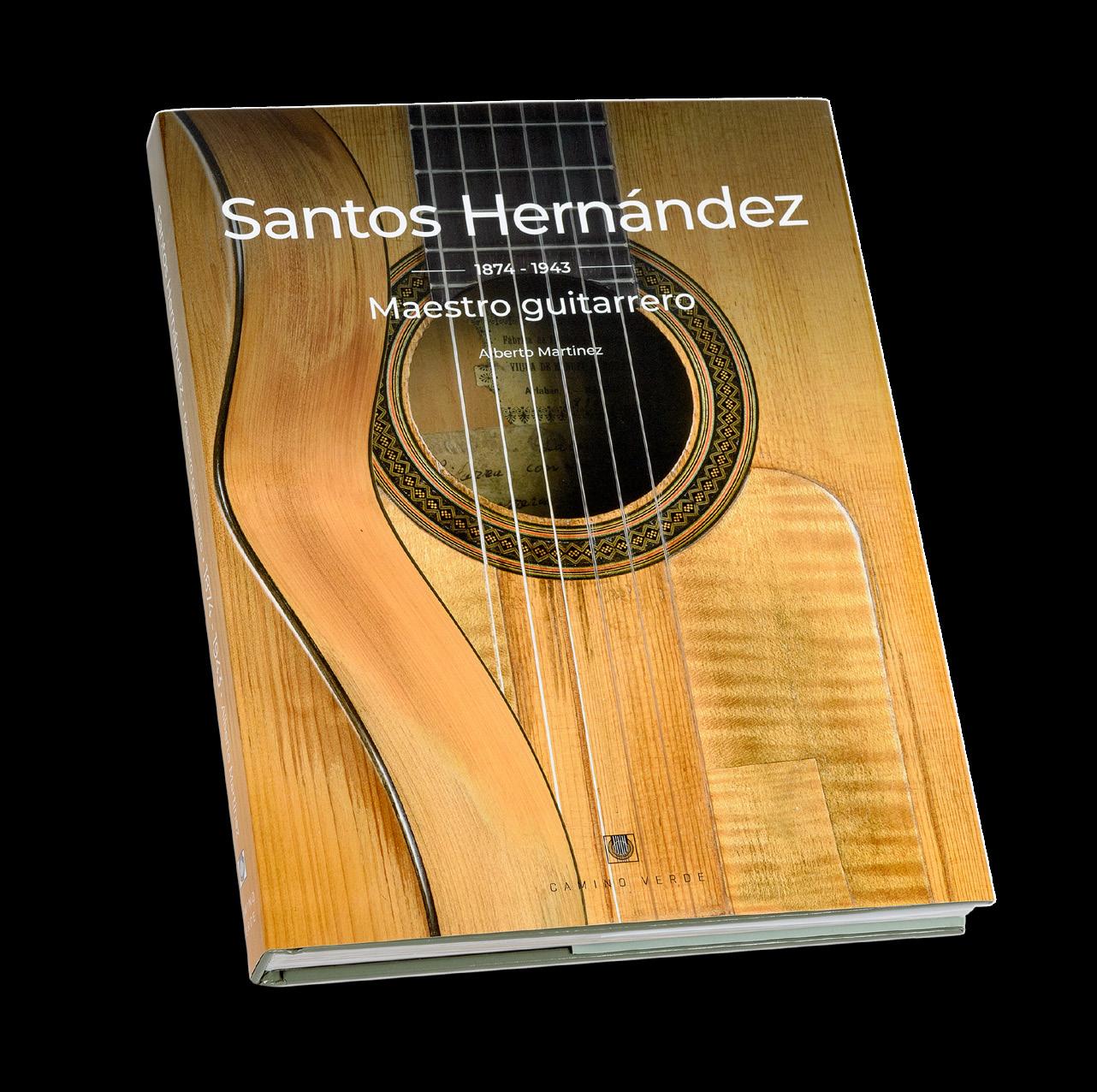

Rationalised production and the creation of instrument factories, such as Remy, Laberte and Thibouville-Lamy, heralded a major economic turning point for the town. These firms, which employed hundreds of workers, were able to produce both bowed and plucked string instruments, as well as, in some cases, wind instruments, pianos, mechanical musical instruments and spare parts.

Artisan luthiers, bow-makers and a range of related professions in and around the town made up the industrial lutherie ecosystem: crafting instrument cases, making tools and small mechanical parts, timber splitting, wood turning, sculpting headstocks, varnishing, crafting bridges, preparing horse hair, etc. This system of production continued uninterrupted until 1914.

Although Mirecourt remained important as a learning hub for aspiring luthiers from France and

Museum display case featuring Romantic guitars and the painting “Young Man playing the Guitar” by François Navez, 1836.

Arranged around a giant violin in the museum’s main hall, the items on display are explained through descriptions, commentaries, videos, music to which visitors can listen, as well as instruments that can be touched and even played…

The museum has conserved intact, on the opposite river bank, the former Gérôme workshop, whose luthiers were specialised in making guitars and mandolins.

elsewhere, the World War from 1914 to 1918 and the post-1929 depression triggered a decline across all of its activities.

The Second World War, Parisian outsourcing and foreign competition further exacerbated the crisis, culminating in the three main production firms of the twentieth century going into liquidation in the 1960s: Thibouville, Couesnon and Laberte.

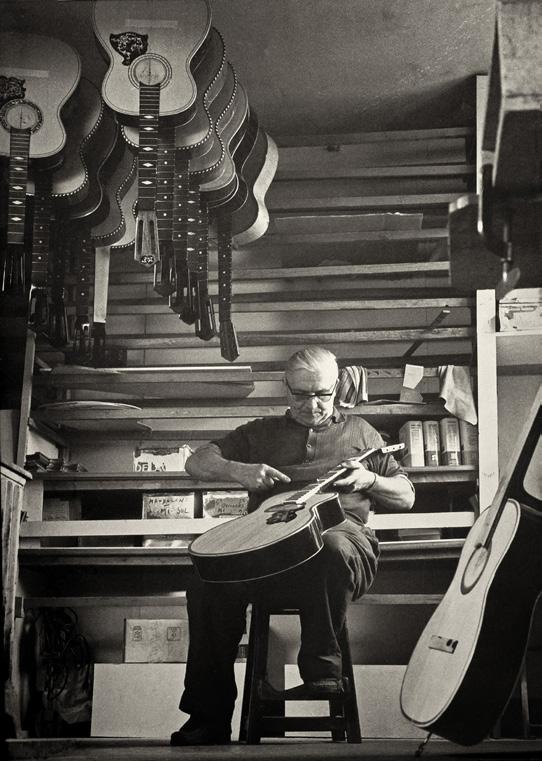

In 1970, in order to safeguard the transmission of lutherie and bow-making, the École Nationale de Lutherie school was founded and in 1973, the Museum of Mirecourt.

Today, there are some twenty artisans and artist-makers still producing bows, accessories and stringed instruments – both bowed and plucked – and performing vintage instrument repairs and restorations.

Valérie Klein Curator, Museum of Lutherie, Mirecourt

His guitars reflect his experience as a cabinetmaker: the homogeneity of his work, the elegance of his rosettes, the bevel-edged headstock… so many qualities that all point to a creditable representative of French lutherie.

How would you describe your path to lutherie?

Bertrand Ligier – My interest in wood began in Brittany, on family holidays, when I would go and watch the shipwrights working on the wooden boats. Since I had started learning to play the guitar and enjoyed it immensely, I thought that I would try to learn lutherie. There were no lutherie schools where I lived, so I enrolled to study cabinetmaking at the applied arts and technical school. With a qualification to my name, I worked for two years for a cabinetmaking workshop. In parallel, I made my first classical guitars: just me, at home, in the evenings, working it out by myself. One day, I showed them to my

teacher and to some local luthiers, who encouraged me to keep it up. My subsequent meeting with Dominique Field made all the difference. He helped me develop the construction technique and aesthetics of my guitars and rosettes. Dominique pushed me toward fine lutherie. My rosettes follow in the tradition laid down by Robert Bouchet and Dominique Field: understated and yet very sophisticated. I have yet to find my very own rosette, an all-time signature style, like Daniel Friederich’s rosettes. With my temperament, I change design every five or six guitars. I don’t vary them greatly, but I do like blending the same ingredients in different ways, much like musical variations on a theme.

B. L. – My early bracing was in the Torres style, using seven struts, albeit with reinforcement under the bridge. I later added a second harmonic bar, slightly sloped; then I re-

duced the fan to five struts. In the meantime, I met Dominique Field, who was using a similar bracing, and he confirmed that it was a good bracing design for reasons of balance.

Since then, I have kept using this type of bracing, as well as seven-strut fans, but they have evolved a great deal over time. Today, the fan’s closing bars stretch right out to the linings and I reinforce the central area with additional little supports. This bracing works well with tops made of light spruce, up to 400 kg/m 3 maximum. But weight alone cannot tell the whole story; I also measure the soundboard’s transverse and longitudinal flex before gluing the bracing and I strive to keep the values roughly the same. When the values differ too wildly from the usual readings, I modify either the bracing or the soundboard thickness. In guitar-

Achieving a beautiful varnish requires three to four weeks.

His bracing is designed to strengthen the area under the bridge.

A satinwood guitar, in the tradition of Lacote and Simplicio.

making, there are many parameters that come into play and we have to make rather complex decisions!

The two harmonic bars do a good job controlling the longitudinal and transverse flex; but if the soundboard is too floppy cross-wise, a fivestrut fan would not suffice, as it would leave too much open space, and so I opt for a seven-strut fan or bolster the centre using additional, slim supports.

Why are the backs composed of several pieces?

B. L. – It all depends on the wood. Very often, it enables me to use the optimal parts of the timber, but sometimes it is also a good solution when seeking a more stable back: the more seam strips, the stiffer the back.

I always aim to make a rigid body, so as to focus my work on the soundboard and its bracing. The risk is that if the body ends up being too unyielding, it can create a “cathedral” effect, with far too many harmonics. Yet another kind of balance to find when building guitars!

A simple back, coupled with light construction, offers Torres-style sounds, with beautiful basses and a very clear fundamental, but middling power; a reinforced back helps lengthen the sustain, enrich the harmonics and increase power.

The other problem that I have encountered is that the guitar tends to become heavier with multiple reinforcements, whereas I like the idea of making a comfortable instrument, natural for the player. The

“I love spruce.

The work in the rosette stands out much more against it than on cedar.”

Understated rosettes that display enormous sophistication.

challenge lies in making it stiff but not too weighty; around 1.6 kg. I have made significant weight distribution changes.

B. L. – I try to use wood with a density of 0.4 or 0.45, nothing too heavy, so as to maintain the instrument’s balance. That is what makes guitar construction so complex and so enthralling at the same time: any changes in rigidity, weight or balance, make an irreversible difference and define the instrument’s character.

I am not keen on making replicas of guitars by the great Spanish masters, nor am I motivated by modern, lattice-type guitars. I am seeking a compromise that would situate me somewhere between the two, using truly French lutherie: a guitar of modern construction, powerful and with a relatively neutral sound so as to offer the musician maximal latitude.

I think that “traditional” guitars still harbour many possibilities for improving the acoustics, such as laminated ribs, to take but one example. I had started doing it with cypress or cedar, but now I line them with spruce and the outcome is better.

I also fortify the area in front of the bridge because I always worry that the bridge will tip forward over time. The arch in the soundboard also plays an important role. It prevents the bridge tilting too far while simultaneously allowing the use of a very thin top. The dome in my soundboards measures 3.5 mm.

B. L. – For the soundboards, I love spruce, as much for its sound as for the visual contrast with the rest of the guitar. The work in the rosette stands out much more against spruce than on cedar. Depending on how flexible it is, I use five or seven braces in the fan.

For the backs, I use mostly rosewoods: Indian, Madagascar or Brazilian.

Rosewood is difficult to varnish because of its pores. You need to start with an extremely smooth surface, fill the pores, varnish, sand and then revarnish. It takes a long time to achieve a mirror effect; I spend between three and four weeks on it to obtain a beautiful finish.

One of my most recent guitars was made of satinwood and I was really pleased with how it turned out. Satinwood has a lovely sound and is pleasant to work with, apart from all the cross-grains, which make planing hard work. It’s a wood that is widely used in cabinet making; a noble and very elegant wood. Furthermore, it varnishes very nicely. My dream would be to find a piece of quilted Cuban mahogany and make a guitar in the tradition of Lacote or Simplicio.

B. L. – Yes, for purely aesthetic reasons, I position the twelfth fret slightly off the body, which enables me to have a nineteenth fret composed of two rather broad parts without quite covering the opening of the sound hole. I like to add a uniquely artisanal touch to my guitars. At the moment, I am making

an inlay on a tie-block. It’s a tribute to Simplicio, whose work I very much admire. I wanted to add a refined detail without repeating the mosaic. There are also features that stem from the French tradition of cabinet making, such as the bevel on the head, which outlines its shape with light, or the ornamentation in the rosettes, with its somewhat austere yet finely wrought motifs, with woods in natural, undyed colours, so that time won’t fade them. When I need a 1.2 mm width strip of purfling, I’ll tend to use four strips of 0.3 mm instead of one single wider one, in order to create vibrations of colour and light.

The flawless construction of guitar N° 99 in spruce and Madagascar rosewood.

Despite being a very high-level guitarist, he abandoned his career out of shyness to become instead a luthier out of passion. He has made guitars with alternative sound hole locations, bodies made of bamboo, rosettes inspired by cathedrals and the innovations look set to continue flowing.

Bastien Burlot – My trajectory as a classical guitarist was quite conventional. I firstly earned my gold medal from the Lille Conservatory and then studied at the CNSM in Paris ( Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique ). It was there that I started to realise that I did not actually enjoy performing on stage, in front of an audience. My interest turned, instead, to the manufacture of the instrument and, with advice

from some luthiers, I built my first guitars in the living room of my flat. There was dust everywhere and my guitars were dreadful! But, as a perfectionist and someone who is always determined to keep going on any project that I start, I kept on making simple guitars which, although they could never become concert models, nonetheless helped me improve my technique. I found the work really fulfilling, in

contrast to the discomfort that I had experienced on stage. I then taught guitar in conservatories in northern France for seven years. At the age of 27, some thirty guitars later and when they started showing more potential, I felt that I was ready to strike out as a luthier and drop guitar teaching.

You were already making guitars with the sound hole on the side; why?

B. B. – That stretches back to my friendship with Roland Dyens, who was my teacher at the CNSM. In his compositions he added percussion on the guitar, and he found the location of the sound hole inconvenient. So I built him a guitar with the sound hole in the upper rib. The idea had come to me when studying acoustics. There was of course already a precedent – the Carlevaro guitar – but I suspected that the opening all around the soundboard was rather ineffective because it could not have sufficiently compressed the air. The day that I had this epiphany, I took a concert guitar that I had just finished, taped over the sound hole and sawed a big opening in the side. Bingo! The guitar was completely transformed: it had a great voice, better projection, more power and its

sound was more “all-encompassing”, which was very pleasant for the person playing. I immediately started building a prototype with a rosette-free top and sound hole in the rib. Roland Dyens played for a long time with one of these guitars. The problem with this system was the imbalance between what the audience hears and what the guitarist hears. For the guitarist, there was a kind of “loudspeaker” effect that made the basses sound louder and thus prompted the player to make changes accordingly. I therefore went to work for a year and a half with the Châlons-en-Champagne acoustic laboratory and I ended up modifying the instrument so as to ensure that the guitarist perceived exactly the same sound as the one being projected. This culminated in the model that I call the Maestro HF (high-fidelity), which has two openings, in two different places. I maintained the same sound hole surface area, but divided it into two openings, approximately 1/3 and 2/3 the size of the original: a small sound hole on the upper rib and a large one on the lower rib. It was amazing; you could walk all around the guitar being played and enjoy identical perception of its sound from any given spot. It gave the listener the impression of being “in” the sound.

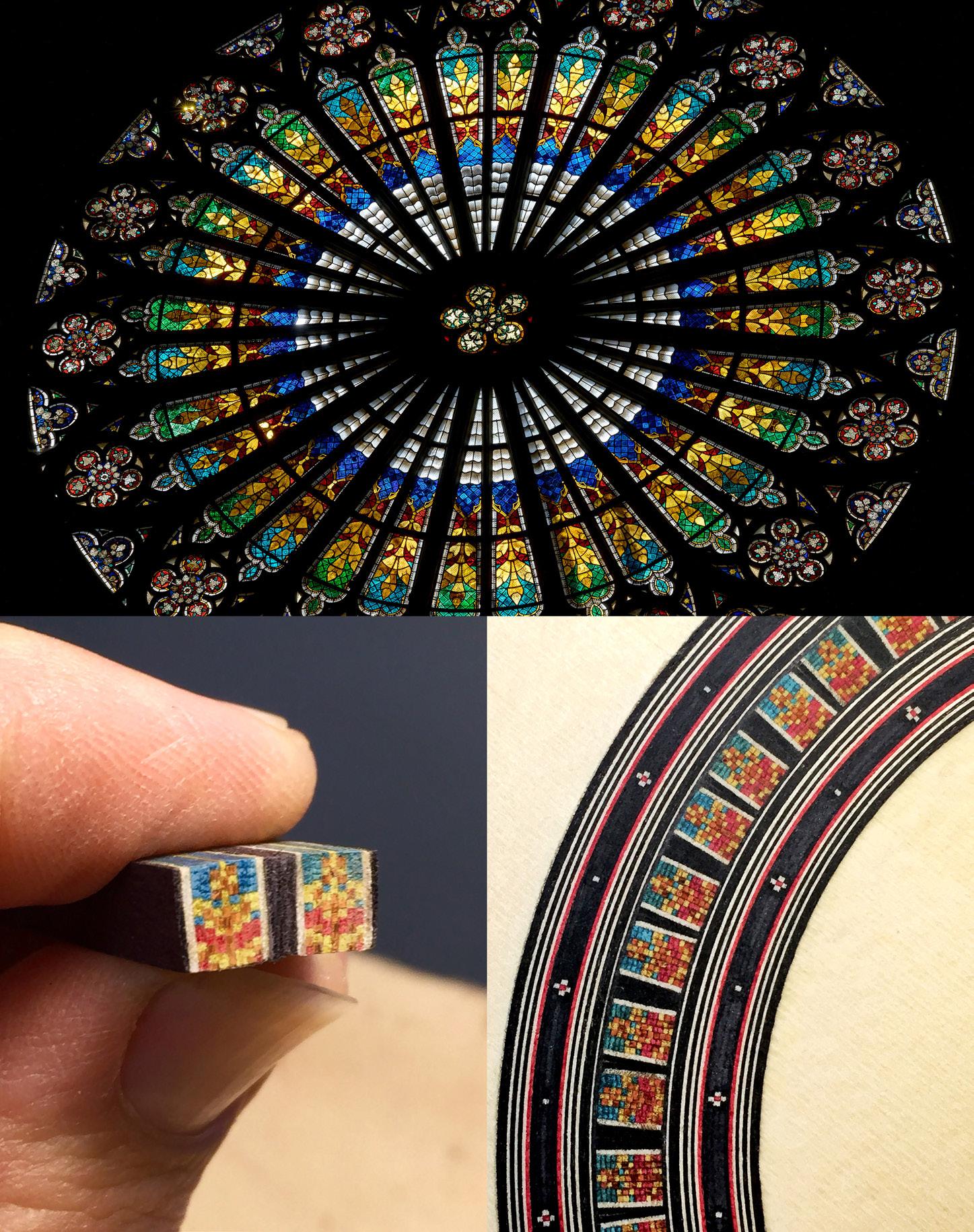

The Strasbourg cathedral’s stained glass inspired him to make the rosette for one of his guitars.

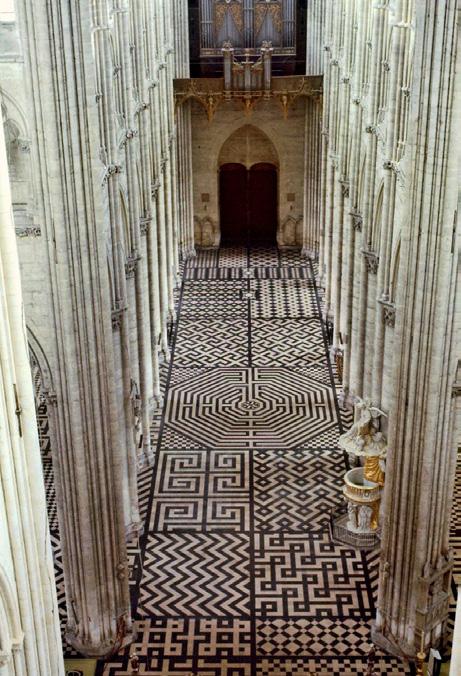

For the Alkemia model, Bastien Burlot chose patterns from the flooring of the Amiens cathedral.

For the Alkemia model, Bastien Burlot chose patterns from the flooring of the Amiens cathedral.

A cedar Alkemia model, with a rosette inspired by the Notre-Dame de Paris cathedral.

A cedar Alkemia model, with a rosette inspired by the Notre-Dame de Paris cathedral.

His usual bracing, highly complex, on a soundboard made of pine from a fifteenthcentury German cathedral.

And why make guitars out of bamboo?

B. B. – I have always had this creative instinct and, in view of our planet’s ever-diminishing resources, I started looking for possible alternatives. The idea of using bamboo came through Jean-Yves Alquier, a fellow luthier who was already working with this material. I had to learn how to work with it; it is brittle and hard to bend. I stayed with the construction of the Maestro HF model and I have christened it MaestrO2, in reference to oxygen. Orders started coming in remarkably quickly, especially from customers in… Asia! They are more familiar with bamboo and understand its mechanical qualities. But here in Europe, if you go upsetting conventional codes and aesthetics, you find yourself coming hard up against a wall of guitarist reluctance…

And you came to a more traditional look…

B. B. – Yes, for me, the shift toward the traditional guitar constituted an enormous challenge: I had never made a rosette or done French polishing. I convinced myself to strive for the likes of Dominique Field, of Jean-Noël Rohé, or of Bertrand Ligier; the dizzying heights of excellence. I had to adapt my bracing because, in order to create a traditional model, there was a new parameter with which to contend: the sound hole on the top. When working out the proportions for this

new bracing, I took my inspiration from the building plans of Chartres Cathedral, which had been designed in accordance with harmonic frequencies. It’s a somewhat mystical, spiritual approach. I called this new model Alkemia. Then I was moved to work on something timeless, making rosettes featuring motifs inspired by French cathedrals: Chartres, Amiens, Strasbourg and Paris were the first ones; the next rosette is to be based on the cathedral in Reims. With Alkemia, I was able to obtain a good stretch of vibrating surface by moving the harmonic bar as high as possible, right up to the rim of the sound hole. It is almost like a Fleta bracing, more open, better ventilated, with openings all over the place. The aim is to give the top as much freedom as possible, adjusting the vibratory modes through different thicknesses and the profiles of the fan’s braces. One subtle – yet invisible – detail is that the three central struts are forced into their glued position in such a way as to arch the soundboard and better withstand any warping pressure from the bridge. In addition, my soundboards and ribs are quite thick, around 2.5 mm.

B. B. – There are two guitars that have left indelible marks on me. The first is a Dominique Field guitar that I heard played by Eduardo Isaac in

concert when I was very young. It displayed exquisite balance. The other is the Daniel Friederich that belonged to my guitar teacher in Lille. He lent it to me when I was going for my gold medal and I played very well on that guitar; it gave me wings, it was magical. My ideal sound would be a combination of those two guitars.

Any new projects?

B. B. – Yes, it is called “Flamme” (Flame) and it is an acoustic fourteen-frets-to-the-body guitar with steel strings and a narrow neck. I didn’t want to head toward the style of a Martin; I was looking for a guitar with amplitude, a big sound. I took the Maestro HF classical as a starting point, with its two openings; I lowered the neck-body junction slightly in order to obtain fourteen frets, bolstered the bracing a little so as to better withstand the pull of the steel strings and added a truss rod. Since I dislike the idea of penetrating the soundboard so as to attach the strings with pegs, I made a bridge to which the strings attach, on the rear face of the tie-block, on a small bone plate.

For the Flamme I have again used the open headstock of the Maestro and reshaped the teardrop decoration to represent a flame. The top can be made of either spruce or cedar. This model offers me greater aesthetic freedom to create, for example, a fingerboard using figured ebony or a black-dyed guitar with a maple bridge… Going forward, I am only going to produce two models: Alkemia for classical and Flamme for acoustic.

Flamme: an unconventional acoustic guitar.

Above, dyed black, with bridge and head of maple, ordered by the French singer and guitarist “-M-”.

In France there is a competition dating back to 1925 that honours artisans who are highly respected in their trade: Meilleur Ouvrier de France (Top Artisan in France).

This competitive exam is held every three years and competing candidates must produce a masterpiece that displays their outstanding expertise and pursuit of perfection.

The winners in their respective categories receive medals and certificates at an award ceremony attended by the French President. This year, Simon Burgun has been crowned Meilleur Ouvrier de France , as were his fellow luthiers, Olivier Fanton d’Andon in 1986 and

Jean-Noël Rohé in 2004, among others. For twenty years as of 1991, it was Daniel Friederich who headed the judging panel in the contest for the guitar lutherie category.

Simon Burgun – I have always loved working with my hands and by dint of repairing my friends’ guitars, I wound up wanting to make one myself. So I found a training course run by a luthier who was going to teach how to build a replica of the Romantic guitar by Grobert in the Paris Museum; the one with the soundboard signed by Paganini and Berlioz. Since I thoroughly enjoyed that course, I immediately set out to look for a school where I could complete my training. I visited the school of lutherie in Puurs, Belgium, and met with Walter Verreydt and Karel Dedain, which was a real turning point: I dropped everything in Strasbourg, where I was living, moved to Puurs, and ended up living there for two years while studying lutherie. It was fantastic, it offered everything that I loved: a bit of theory and lots of hands-on practice in the workshop!

The Rabot d’Or (golden plane) certificate that I was awarded by the CMB in Puurs gave me the confidence to set myself up as a luthier when I returned to Strasbourg in 2013.

The guitar offers such a mind-boggling array of variants, from Romantic guitars to contemporary

“I loved working with my hands and by dint of repairing my friends’ guitars, I wound up wanting to make one myself.”Replica of the 1830 Grobert (pictured on the right) that belonged to Paganini and Berlioz.

He won the prestigious “Meilleur Ouvrier de France”

2023 title with this copy of a René Lacote guitar.

Replica in the style of the 1845 Panormo in the St Cecilia Museum, Edinburgh.

instruments, with electrics, archtops, acoustics, classicals, etc. You could spend a lifetime making every different kind of guitar!

And which types of guitar do you make today?

S. B . – I have five models, including four Romantic guitars. One is a replica of an 1830 Grobert; another of an 1820 Petitjean; an 1845 Panormo; and one that is based on Stauffer’s Legnani model. For my classicals, I make a model inspired by Torres. The copies of Romantic guitars are very popular with music schools and conservatories. Since they are wary of having their students play on antique guitars, they prefer to purchase reproductions. The Romantic guitar is from a period when the guitar already had six strings and tuners: a guitar already heading toward the guitar as we know it today. On French Romantic guitars it is possible to make everything except the strings and frets, and I like to do everything by hand, without machines, using traditional tools. On the Stauffer and Panormo models, however, you need tuning machines.

Since I have been making predominantly replicas for about ten years, I am now working on a more personal model, a very French one… a truly beautiful guitar, a guitar with which I can take my time and do everything just as I please, paying attention to every detail.

I am also very conscious about the longevity of the instrument: I never varnish the inside, for example,

because the varnish would make it impossible to glue in any cleats in case of subsequent repair work. I like to think that my guitars are built to last two hundred years, like the Romantic guitars that I love so much.

Which direction are your classical guitars taking?

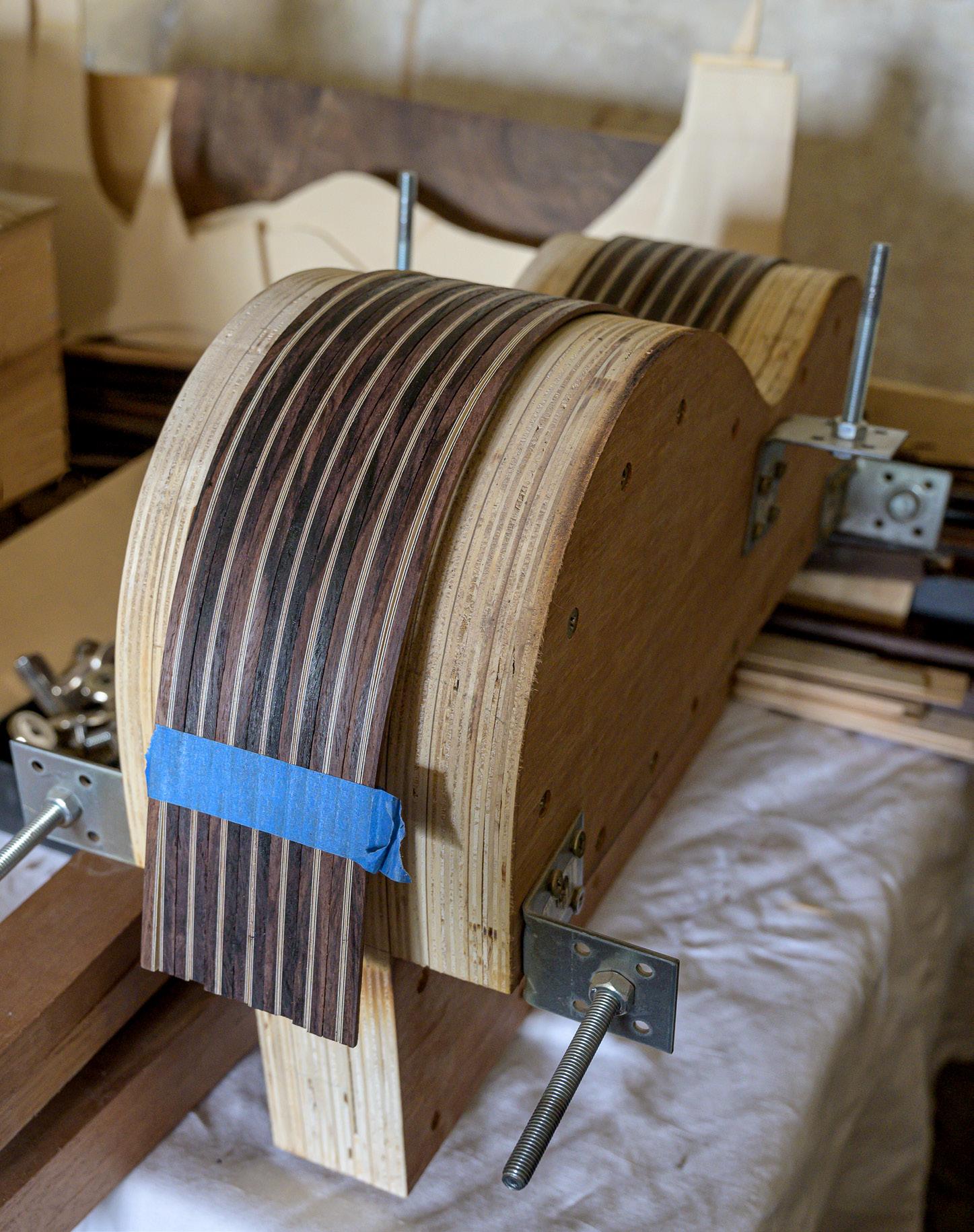

S. B. – I want to shift toward a more modern guitar construction, a bit like my colleague and neighbour Jean-Noël Rohé, and in particular with laminated ribs, as per Daniel Friederich. I know how to do it, since Romantic guitars often have, say, a rosewood back, for example, lined on the inside with spruce. What is more, I really do enjoy making different templates, moulds and casting moulds!

What advantages do you think the Romantic luthiers saw in laminating the backs?

S. B. – I think that there are several reasons

“The copies of Romantic guitars are very popular with music schools and conservatories.”It has a scale length of 634 mm.

behind it and that there is a hierarchy to those reasons. The primary reason is technical: it enables you to include woods that, while very beautiful to the eye, are nonetheless difficult to work, while maintaining stability. When working with woods like burr elm, for example, it is highly likely that there will be some warping over time; laminating the back is thus the obvious solution. The second reason is that the nineteenth century was the time of the industrial revolution and for the first time, there were machines capable of producing veneers as thin as 1 mm.

Lastly, it also reduced costs, since luthiers could use spruces of lower quality. When you look inside these guitars you can see that there are defects on the inner laminate, but there is no harm done in using a cheaper wood. For me, the main thing is to have the body rigid enough to enable me to focus my work and finetuning on the soundboard.

Which other aspects are you trying to develop?

S. B. – I like to make both linings of moulded spruce, the way that guitars from Mirecourt are made, rather than of sawn mahogany as per the Spanish style. I don’t find “peones” particularly elegant. The other thing is that I am thinking of dropping the Spanish method of building, and instead start working with the neck and body separately. It would enable me to make a model with an adjustable neck, like the Viennese guitars; along the same lines as Gary Southwell’s work. I think that it is really clever and will settle the string height conundrum.

You have just been awarded the title of Meilleur Ouvrier de France 2023 based on your René Lacote replica. Why Lacote?

S. B. – A bit like Robert Bouchet, the two luthiers that fascinate me the most are Lacote and Torres. Lacote inspired Bouchet to introduce his nodal bar. Lacote has always been a key reference in France. He never made mediocre guitars; his work is the epitome of handsome craftsmanship, of elegance and is a symbol of excellence.

“I like to think that my guitars are built to last two hundred years or more.”

This self-taught luthier, passionate about his craft, started out building guitars for flamenco before focusing on classical models and the quest for his own sound inspired by French master luthiers.

Thomas Dauge – As a youngster, I taught myself to play the guitar and then I took flamenco classes at Concha Castillo’s academy for four years, as well as several flamenco masterclasses. I came to lutherie in much the same way as so many of us: I was short on money but quite good at working with my hands, and so I wanted to build my own guitar. My first instrument was a flamenco guitar, with a walnut body and cedar top because they were the most affordable woods at the time. It is funny, but I have always had this penchant to keep making flamenco guitars with cedar tops: I find the sound quite beautiful, less aggressive than spruce, and the guitar is more versatile. It sounds just a good for flamenco as for South American music or bossa nova. Initially, on top of flamenco guitars, I was also playing Manouche jazz, and so I made two Selmer-style guitars. It was great because it gave me an introduction to another construction technique: flamenco guitars were made the Spanish way using a solera, while the Manouche was built with the body on one side and the neck on the other. Today, I prefer the Spanish method of construction; the idea of adding pieces to the core somehow seems

more logical to me and gives me the impression of maintaining more control over the whole. I also get the feeling that this type of construction influences the sound because the neck and body are locked together right from the outset.

T. D. – One of the first concert guitars that I ever heard was a Friederich. It happened when I was visiting a neighbouring luthier to show him one of my flamenco guitars, and he showed it to me; I was astounded by its musicality; the guitar just naturally sang. I said to myself: that’s what I want to learn to make! So from 1998 to 2007 I taught myself lutherie, using as a base the work of Daniel Friederich as well as Émile Leipp, from the Musical Acoustics Laboratory in Paris. That gave me greater insights into how the guitar actually works. Four or five years later, still self-taught, I set myself up as a luthier. In the early years, my output was split between flamenco and classical guitars, all of which were largely inspired by Spanish

He uses a home-made tool to calibrate the thickness of his veneer strips.

Here we see his usual bracing for spruce soundboards on classical guitars. The ribs, reinforced with strips of mahogany, are fitted into the neck with little wedges.

The slightly forward-set bridge means that the twelfth fret can be slightly off the body and the nineteenth fret is full-width.

“I taught myself lutherie, using the work of Friederich and Leipp, from the Musical Acoustics Laboratory in Paris, as a base.”

guitars: French lutherie seemed unattainable. Little by little, I began inching my way towards it, starting with Bouchet’s nodal bar, or Friederich’s laminated sides. Very quickly, I understood that merely copying the construction was never going to achieve the sound that I was seeking; it was first important to grasp the luthier’s philosophy and choices. These French bracing styles, for example, were suited to a given type construction and a given type of wood: they were not at all universal; they were very personal. For Bouchet-style construction, selecting wood that was too stiff for the soundboard or for the nodal bar would lead to disaster. For Friederich, it gets even worse: choosing the wrong wood or the wrong thicknesses would mean that the resultant disaster would be further amplified by the laminated sides. In 2007, I established my first workshop in Libourne, my home town, and in 2009 moved to Bordeaux. Around 2012, I began to truly understand this lutherie and my guitars started to develop, both in terms of proportions and construction.

And now?

T. D. – My current bracing comprises seven struts, in quite an open formation, which converge rather high up on the neck. This affords me greater transverse flexibility, freeing up the top more and resulting in a mellow sound. I add a closing brace on the treble side. These days, for both red cedar and spruce-top guitars, I reinforce the sides with small strips of mahogany, as if in the manner of Dominique Field, but with less rigid strips that are wedged into the linings.

Another detail is the assembly of the ribs into the neck, with small wedges, because I find that this set-up provides excellent strength. The back has two vertical braces as well as the central back seam reinforcement and three horizontals. The back braces and linings are made of cedro. My template is my own; I changed it four times before settling on the current one. Everything has evolved, the overall shape, the domes. Lutherie boils down to an unceasing search…

What is more, I brought the bridge slightly further forward in order to have the twelfth fret marginally higher than the body and a fullwidth nineteenth fret, as Friederich did, and I’m pleased with the results: the guitar’s balance and musicality improved.

Therosette is made up of natural, undyed woods.

Very stiff back, with its broad seam cover and two additional vertical braces.

T. D. – Above all, rosewood, be it Indian or Brazilian. For the tops I prefer spruce, although it is getting harder to source high quality spruce. I prefer it to be light – between 380 and 400 kg/m3 – which I tend to find in the French-Swiss Jura mountains. I cannot trust a wood that is too light, however, as it generally comes from trees that have shot up too fast and is riddled with cross-grain. I use very little machinery; I love working my soundboards by hand, keeping that contact with the wood. I still make numerous measurements of the density and flex, but now I am increasingly trusting the experience that I have gained with wood and listening to my hands.

T. D. – I make my own model chiefly, by I’ll occasionally turn out a Torres replica, a Bouchet copy or a Friederich copy. I make the copies because I sometimes receive orders for them, but also for the enjoyment of it. I like getting closer to those master luthiers, to try to see through their eyes; I am lost in admiration for their work. My model brings together many of the things that I have learned from others. The only reason that I was able to forge my own identity and improve my craft is thanks to observing those superb instruments. My hope is to find my place in this French lutherie that seeks aesthetic consistency and excellence of workmanship. Without being flashy or gimmicky, what we appreciate is quiet elegance and refined taste.

“I am now increasingly trusting my woodworking experience and listening to my hands.”

He makes flamenco guitars with tops of either spruce or cedar.

Much like the journeymen of yesteryear, who apprenticed by travelling workshop to workshop and country to country, PierreAlexandre studied lutherie in England, then in Italy, before finally settling in the area where he was born in France.

Pierre-Alexandre. Bellest – I learned guitar from the age of eight to eighteen but ultimately came to realise that giving concerts and performing in public was not my calling. Teaching guitar was never going to be my vocation either, but since I really enjoyed working with my hands, I started developing an interest in building guitars. In 2006, my first step was to go to England and take a course under Stephen Hill. I’ll never forget the excitement of building my first ever guitar; it motivated me to take courses at Newark

College, also in England. By the end of these studies, I had made three guitars: one with Hill and two at Newark but, since I wanted to delve deeper, I set off to Milan, to pursue my studies at the Civica Scuola di Liuteria.

The teaching in Italy was incredible, firstly because they were teaching us how to build more than just classical guitars; they covered all plucked string instruments. Secondly, we had classes on chemistry, organology, restoration, technical drawing and guitar playing, too, which were mandatory for those who did not know how to play. We also took classes with external professionals, who were not teachers at the school. The teaching was holistic and most interesting. During the restoration course, for example, we learned the different approaches to restoring a vintage instrument, depending on whether it would be put on display or actually played. For display-only models, all the original parts can be kept, whereas if the restored instrument is destined to be played, we need to strengthen or replace any parts that have become too fragile. This meant that I was even able to work on several violins.

The backs are strongly reinforced and are generally made of Indian rosewood.

And when did you set up your own workshop?

P.-A. B. – When I came back from Italy, I created a small workshop at my parents’ house and started working.

I had the opportunity to meet Dominique Field through a guitarist friend of mine, Aurélien Colas, and to show him one of my guitars; it was number 20 or 21, I think. He liked the sound, but nothing else. He therefore gave me lots of pointers, explaining to me where improvements could be made, both on the technical side and in terms of aesthetics. He really encouraged me to strive for more perfection and greater elegance. The shape of my earliest guitars was similar to that of Hauser and their construction followed Torres, with a seven-strut fan, closed at the lower end. I started by doing away with the closing bars, replacing the plate under the bridge with two small supports so as to strengthen that area and, finally, reducing the seven struts to five. My Italian training nudged me toward a light spruce, such as the kind that comes from Val di Fiemme.

He shows us his template, which facilitates the operation of fitting the ribs into the neck.

For each guitar, he notes down the characteristics of its wood on the circular off-cuts.

The decorative veneer strips for the soundboard are moulded under heat.

Later, when Dominique Field saw the type of light spruce that I was using, he advised me to put stronger bracing on the upper lobe and the outcome was good: the notes were clearer and everything more balanced.

I leave the central part of the soundboard about 2.4 or 2.5 mm thick and taper it off to 2.1 or 2.2 near the outer edge. Naturally, it varies in accordance with the density and stiffness of the wood. My current bracing is very close to that of Field, but I do leave the fan open, without the little closing bars arranged in a V.

P.-A. B. – I was initially happy with the results that I achieved from tops made of cedar, but these days, after having built ninety guitars using both woods, I have to say that I prefer spruce after all. The overall shape of my guitars is quite similar to those of Hauser but the construction is inspired by Dominique Field’s guitars. For the body, I love Indian rosewood because it is so very reliable. I always find beautiful pieces at Rivolta, in Italy. Moreover, I am not planning to make a variety of models.

P.-A. B. – I do not laminate my guitar sides; I prefer the sound that I obtain by using little pillars

“I do not laminate my guitar sides; I prefer the sound that I obtain by using little pillars of cedar.”

“I have a greater affinity with spruce than with cedar.”

of cedar. Another construction detail is that I slot the ribs directly into the neck, with no need for wedges thanks to a slit carefully measured to the exact size. I created a template for myself so as to avoid any mistakes with the angles. I add a slight twist to the fingerboard, offering a little more room under the bass strings which means that the saddle can sit straight, set at equal height all the way across. I also carve small notches into the saddle in order to modify the point of contact depending on the string. For example, I make a deeper notch into the edge of the saddle under the G string so as to give it a longer scale length. This is an issue in particular with nylon strings, and especially the G string, which has a greater diameter than the others. There are two funny little tricks that I learnt in Italy and which come from violin lutherie. When using animal glue, if you want to slow down the drying process, you can do one of two things: the first is to add a few drops of vinegar to the glue. The drawback is that it alters the glue over time and so it cannot be stored; you have to discard it when you have finished gluing. The second option is to add a clove of garlic to the glue and heat it for an hour or two. Unbelievable though it may seem, this prolongs the drying time without altering the glue. The problem is the smell… fortunately, it goes away once the glue is dry!

Rather than laminating the guitar sides, he bolsters them by using little pillars of cedar.

The fingerboard has a slight twist to it, leaving more space under the bass strings.

“I always find beautiful Indian rosewoods at Rivolta, in Italy.”

Paris, June 2023

Website: www.orfeomagazine.fr

Contact: orfeo@orfeomagazine.fr