The Next Fire Generation

A growing grassroots effort to transform wildfire policy and our relationship with fire.

A growing grassroots effort to transform wildfire policy and our relationship with fire.

his edition taught me that Ethos is a team, and Ethos can show up anywhere.

This term was unconventional, with editors (including me!) getting back to their roots and contributing as writers, photographers and illustrators. On the opposite end, a writer new to our team wowed us all and earned a cover slot with his very first story.

This edition includes a first-person narrative and a photo story, and truly represents the diversity and creativity of our staff. Its stories also travel the world.

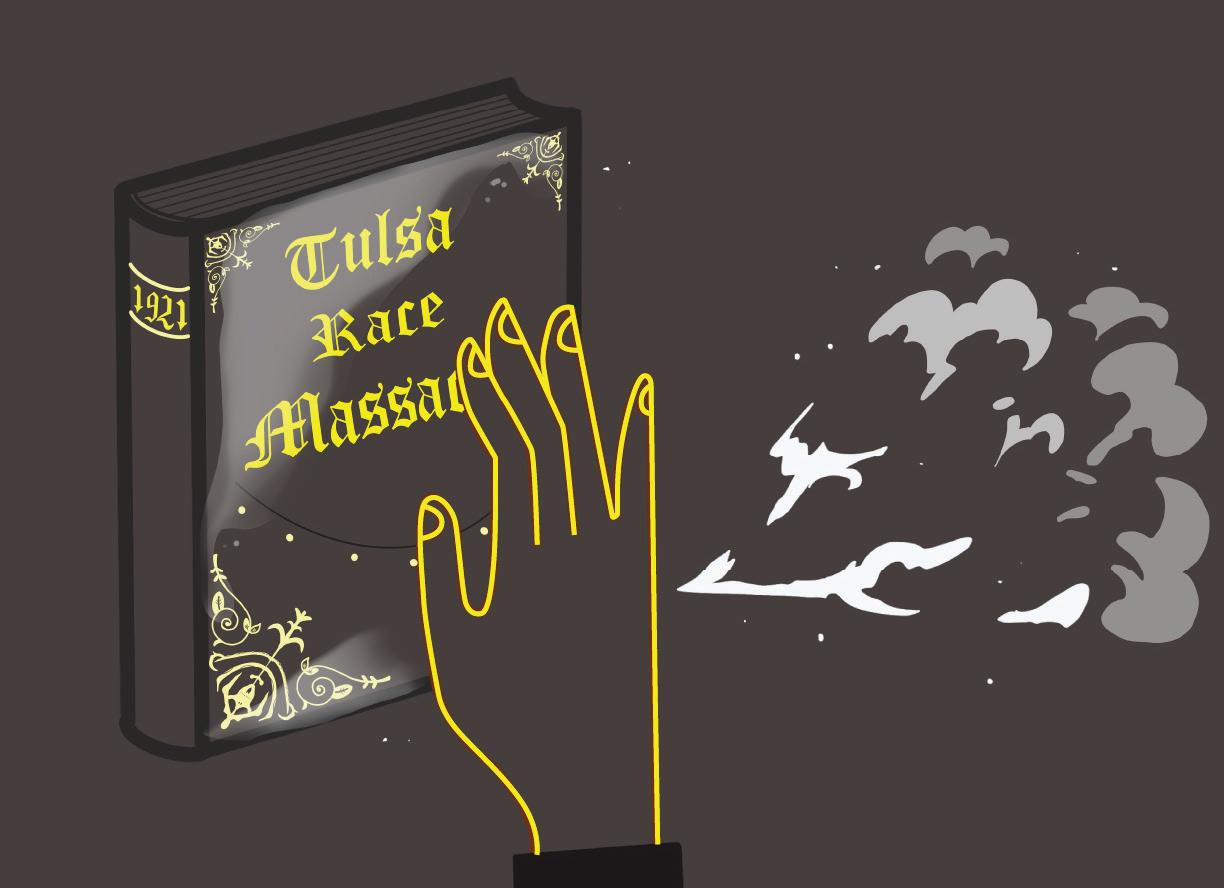

“To be Seen and Heard,” written by yours truly with photographs from our fact-checking editor Bentley Freeman and archival photos curated by Ayla Rivera, brings us to Tulsa, Oklahoma, the site of the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921.

The Massacre brought death and destruction to an area colloquially called Black Wall Street at the hands of a white mob. Its history deeply affects Oklahoma today, but I met Bennie Jordan, a descendant of a victim of the massacre, right here on the University of Oregon campus. He kindly shared his family history and his conflicting feelings about reparations. The question of the efficacy of reparations can bring this story anywhere, and talking to Bennie about it was a true joy.

“It’s Not Therapy; It’s Unity,” written by Emerson Brady, photographed by Liam Sherry, and illustrated by Maya Merrill, shares the story of UO veterans and military family members who, though many university students and instructors cannot understand their experience, find a community together.

The story brings us to Iraq, Mali and South Korea — some of the places Jacob Pixler and Katie Roles served — but centers around veterans’ and military family members’ experiences right here in Eugene.

“The Next Fire Generation,” written by Nate Wilson, photographed by Violet Turner and Paris Snider, and illustrated by Miles Imai, brings us to Washington D.C., where UO junior Kyle Trefny traveled to advocate for marginalized communities in fire policy.

These stories bring us around the world, but don’t worry, the Daisy Ducks will always welcome you home. “Daisies in Bloom,” written by Daniel Friis, photographed by Sammy Karambelas and illustrated by Kaitlyn Cafarelli, shows us how far the booster organization has come since its founding in 1972. Wherever you are in the world, there is always a spot for you in Ethos. Thank you for reading. I hope you see yourself in this edition.

Abby Sourwine

Abby Sourwine

Email editor@ethosmagonline.com with comments, questions

and story ideas. You can find our past issues at issuu.com/ethosmag

and more stories, including multimedia content, at ethosmagonline.com.

Our Misson:

Ethos is a nationally recognized, award-winning independent student publication. Our mission is to elevate the voices of marginalized people who are underrepresented in the media landscape and to write in-depth, human-focused stories about the issues affecting them. We also strive to support our diverse student staff and to help them find future success.

Ethos is part of Emerald Media Group, a non-profit organization that’s fully independent of the University of Oregon. Students maintain complete editorial control over Ethos and work tirelessly to produce the magazine.

The descendents of victims of traumatic racist events, like the Tulsa Race Massacre, are still working through the impacts 100 years later.

How a historic volunteer group connected to the University of Oregon Athletic Department has evolved and remained relevant over time.

A growing grassroots effort to transform wildfire policy and our relationship with fire.

By Us forUO Bike Program’s Femme, Trans, Womyn Identifying Folk Bike School creates an inclusive space for students to learn and connect.

Stories of the people who make the Veterans Center a home.

How a Bend hostel is prioritizing community, affordability and the Dirtbag lifestyle.

Editorial

Editor-in-Chief

Abby Sourwine

Managing Editor

Ella Hutcherson

Writing

Associate Editors

Maris Toalson

Kendall Porter

Writers

Megan McEntee

Emerson Brady

Daniel Friis

Nate Wilson

Illustration

Art Director

Maya Merrill

Illustrators

Kaitlyn Cafarelli

Miles Imai

Soon Lee

Photography

Photo Editors

Ilka Sankari

Wesley Lapointe

Photographers

Violet Turner

Samantha Karambelas

Ayla Rivera

Liam Sherry

Paris Snider

Design

Design Editor

Savannah Zerbel

Designers

Lynette Slape

Esther Szeto

Kaia Mikulka

Kayla Chang

Miles Imai

Social Media Manager

Whitney Conaghan

Social Media Specialist

Maggie Delaney

Fact-Checking Editor

Bentley Freeman

Fact Checkers

Ryan Connors

Nate Wilson

The descendents of victims of traumatic racist events, like the Tulsa Race Massacre, are still working through the impacts 100 years later.

Written by Abby Sourwine | Photographed

Written by Abby Sourwine | Photographed

by Bentley Freeman

| Historicalphotos courtesy of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture | Curated by Ayla Rivera | lllustrated by Soon Lee

Image courtesy of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. “Homes, businesses, and community structures including schools, churches, a hospital, and the library were looted and burned or otherwise destroyed.” 5 | ETHOS | SPRING 2023

Image courtesy of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. “Homes, businesses, and community structures including schools, churches, a hospital, and the library were looted and burned or otherwise destroyed.” 5 | ETHOS | SPRING 2023

Bennie Jordan, clad in a Golden State Warriors beanie and a blue puffer jacket, sat at a table nestled between bike racks outside of the Student Rec Center, inviting people to “SIGN HERE if the cost of living is TOO DAMN HIGH.”

It was a rainy afternoon in mid-January, and Jordan was visiting the University of Oregon as part of his job as a petition promoter. But despite being there for work, he was quick to share other, more personal details about himself.

“My story’s deep,” he says.

Bennie is 66 years old, born in 1956, and has a family history intertwined with centuries of racism in America. His grandmother, Josie Jordan, was born enslaved. His grandfather, James Jordan, was killed in the Tulsa Race Massacre on June 1, 1921, when 35 city blocks of the affluent Black community known as the Greenwood District were left looted, charred and destroyed by white rioters in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Three hundred people were murdered, thousands were left homeless and almost $100 million in property was burned.

James had property on Black Wall Street. He died when his building was bombed by the white mob that took to the streets that day.

Bennie Jordan is now older than his grandfather ever was.

The Massacre “definitely affected generations of people, including myself,” Bennie says.

He thinks his parents were traumatized by the experience of the Massacre. Bennie says his older relatives made a point not to talk about the brutal nature of James’ death, and they shut down questions about it from Bennie and his cousins. They believed “children should be seen and not heard,” Bennie says.

Though Bennie is based in Stockton, California, he travels all over the country for his work collecting signatures for petitions. He is happy to share his story with anybody who cares to listen, and in a way, is sowing the seeds of information across America.

The events of the Tulsa Race Massacre were not taught in Oklahoma schools for decades, but are currently part of the statewide curriculum and are

included on statewide tests. Officials assure that this will not change with Oklahoma House Bill 1775, but opponents argue it will cast this teaching in a new light.

In May 2021, Kevin Stitt, the Republican Governor of Oklahoma, signed the bill into law. HB 1775 essentially prohibits teaching critical race theory — which explores racism’s impact on society — in Oklahoma schools, and restricts lessons that “an individual, by virtue of his or her race or sex, is inherently racist, sexist or oppressive.”

Some proponents of the bill in the Oklahoma House of Representatives and in the education system cited the importance of keeping leftist teaching out of schools.

Those opposed, including the Tulsa Race Massacre Centennial Commission, said it could oversimplify lessons on complicated history. A clause in the bill states that teachers cannot include lessons that suggest “an individual, by virtue of their race or sex, bears responsibility for actions committed in the past by other members of the same race or sex.” Teachers are encouraged to teach events in a historical sense, but opponents say this will minimize the effects of the Massacre that people still feel today in favor of white students’ comfort.

“American and Oklahoma history is uncomfortable; and reconciliation requires truth and processing that is not comfortable,” Phil Armstrong, project director for Greenwood Rising History Center, wrote in a letter to Stitt. “Our entire mission and work is centered in this necessary discomfort.”

The timing of the bill was also a problem for opponents, who said passing a bill limiting teachers’ discretion on their lessons about racist history nearing the 100-year anniversary of the Massacre sets a bad precedent.

2021 not only marked 100 years since the Massacre, but it also marked a time where a concentrated focus was on racism in America. Following the murder of George Floyd in May 2020, Bennie says he noticed a big shift in Americans’ willingness to discuss the Massacre and other traumatic events for Black Americans.

“There’s been so much dirt hidden under the carpet,” Bennie says. “It shouldn’t have taken this long to talk about it.”

The organization Justice for Greenwood was founded in 2020. It aims to share information and advocate for those affected by the Massacre. It’s a nonprofit organization based in Tulsa that states its mission with three R’s: Respect, Reparations and Repair for the Greenwood community.

Reparations programs acknowledge that human rights violations in the past have caused lasting harm and attempt to provide money and other resources to people experiencing those harms in the present. These programs have been effective at increasing faith in the government, providing closure and emotional relief and alleviating economic hardships for Japanese Americans who survived World War II internment camps, according to a study by University of Michigan professors Donna Nagata and Yuzuru Takeshita.

Justice for Greenwood put resources toward a lawsuit filed by 11 people affected by the Massacre, including the last three known living survivors of the attack, against the City of Tulsa and other Tulsa organizations demanding accountability and restitution for the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre and 100 years of continued harm, according to the organization’s website.

Bennie says he started receiving emails from Justice for Greenwood shortly after the murder of George Floyd and the eruption of Black Lives Matter activism. These emails come almost daily and have persisted over the years. Before Justice for Greenwood, Bennie says nobody tried to contact him about his connection nearly as adamantly.

DJ Mercer, a lawyer on the plaintiff’s side of the case, contacted Bennie and many others with family history connected to the Massacre. The testimonies of people like Bennie helped Mercer make the case for reparations.

The case was dismissed in July 2022, but Justice for Greenwood is still fighting.

While Justice For Greenwood was fighting for reparations and the state of Oklahoma passed limitations on education about the Tulsa Race Massacre, Oregon made its own attempt at providing reparations.

In 2021, the Oregon Senate passed Senate Joint Memorial 4, which acknowledged the racist history of the state and the nation and stated “that we, the members of the Eighty-first Legislative Assembly, recognize the need to pursue avenues to implement reparations for the descendants of African slaves in the United States.” It urged those in national power, including the US Congress and the President, to take steps towards establishing reparations programs.

This bill came in response to Oregon’s deep history of anti-Blackness. Oregon passed its first exclusionary law in 1844, when it was still a territory and not yet

a state. While the law banned slavery, it also excluded Black people from living in Oregon territory for more than three years, with violent consequences for violation.

In 1849, Oregon passed another law stating that no Black Americans not already living in Oregon territory could enter.

When Oregon became a state in 1859, its state constitution continued this precedent. It enshrined that no Black people “shall come, reside or be within this state or hold any real estate, or make any contracts, or maintain any suit therein,” according to section 35 of the Oregon state constitution’s bill of rights.

These laws were repealed in the early 1900s, but the presence of white supremacy remained strong. In 1923, the KKK claimed 35,000 active members, representing about 4% of the state’s population at the time. In contrast, according to the 1920 Oregon census, 14,243 Oregon residents were Black, representing less than 2% of the population.

Racist language was removed from Oregon’s constitution just over 20 years ago, in 2002, and to this day Oregon remains primarily white. According to the 2020 census, 74.8% of the state is “white alone” and 84.8% is “white alone or in combination.” Only 3.2% of the population is “Black or African American alone or in combination.”

Oregon tried to take the next steps on reparations in 2021 with Oregon Senate Bill 619. SB 619 states that “The Department of Revenue shall establish a program to pay reparations to Black Oregonians who can demonstrate heritage in slavery and who submit an application

to the department,” and “the department shall pay to each eligible applicant the amount of $123,000 in the form of an annuity payable annually for the life of the applicant.”

SB 619 attempted to begin the process of providing reparations for those negatively affected by racism written into law, but in 2022, the bill stalled in the Senate. Like the effort from Justice for Greenwood, the bill was propelled by the events of 2020 but ultimately failed.

Oregon’s legislature will try again to establish a task force on reparations with Senate Bill 776, which was referred to the Ways and Means committee on March 24, 2023.

Regardless of where Bennie travels to share his story, there is some history of racism and harm that remains unaccounted for. Examples of reparations programs in America are few and far between, while examples of stories like Justice for Greenwood’s lawsuit and SB 619 are much more common.

Bennie is not confident that the efforts to provide restitution will affect his life meaningfully. It’s been over 100 years, and he’s not sure what restitution would look like. He is 66, and his life is already established, and he likes it. He is more hopeful for his daughter, who is younger and grew up with much more information than Bennie did about the Jordan family’s past.

“You have to share information,” he says, or it just might get lost.

When Jim Mann walked into his first Daisy Ducks meeting several years ago, he remembers his exact feeling.

“Thankfully I had my wife there to hold my hand, since I was one of the only guys,” Mann says.

When the Daisy Ducks were formed 50 years ago in Eugene, having a man serve as a Daisy may have been a preposterous idea. Over the years, however, this historic organization has evolved with the ever-changing world.

“I didn’t view that as making me stand out or not fitting in,” says Mann. “It made me realize I was in a special position, and I got heavily involved within the group.”

The Daisies are a volunteer organization made up mostly of retired women in their 70s, 80s and 90s. They contribute to the University of Oregon Athletic Department in countless ways, through funding, mentoring and caring. Most Daisies share strong connections to the UO community in some way. The group is made up of 190 people with 90 volunteer positions including Board Members, Bingo Cards and Team Chairs for each of the 16 athletic teams on campus.

As a division of the Oregon Booster Association, a nonprofit group that raises money and provides support for extracurricular activities, the Daisies meet weekly to talk about the latest in Oregon sports and how they can help. Some of their efforts include providing snacks for all athletes, cheerleaders and band members during games, selling bingo tickets at men’s basketball games to raise funds for athletic scholarships and small yet thoughtful tasks like sending personalized birthday cards to athletes or providing extra volunteer hands during game days.

Founded in 1972, the Daisy Ducks started as a luncheon meeting at the Eugene Hotel, where Oregon head football coach, Dick Enright, said he’d be in attendance to explain the game of football to women who were interested. Sure enough, 350 people showed up. From there, the Daisy Ducks were born.

What bonded these hundreds of women together back then was their love for the Ducks community and its athletes, a love that continues on today. That, and the need in their heart to support these athletes and make their transition and lives away from home much easier. Later in 1972, the Daisy Ducks’ weekly meetings became a consistent Tuesday affair. Each meeting con-

sisted of a different coach, athlete or administrator serving as a public speaker to inform the women about their sport and what they do.

“Every meeting is so stimulating,” says Sandy Karsten, the current president of the Daisies. “It’s remarkable how rich the history is.”

Soon after, as a way to show support, the Daisy Ducks began baking for Oregon athletes. Starting in 1983, a yearly potluck open to athletes of each and every sport was hosted by the Daisies.

Then came the cookies.

What first started as a casual treat laid across the training table quickly became a goodie bag for each and every one of the hundreds of athletes during or before a game. White treat bags wrap around four cookies, stickers and, on occasion, an encouraging note.

Each year, the Daisy Ducks baked and delivered over 25,000 cookies, and, starting in 2007, the Daisies added homemade Rice Krispies Treats to the dessert roster. They made about 5,000 each football season for the players.

“Their baking is amazing,” says Gabby Cleveland, a junior on the women’s lacrosse team. “It just reminds me of home.”

Baking has been and remains one of the Daisies’ most iconic traditions. The football team still receives Rice Krispies Treats, the track and field teams get banana muffins and volleyball players are gifted chocolate chip cookies.

“Don’t mess with their chocolate chip cookies,” jokes Barb Morgan, a two-time past president of the Daisies in 2015 and 2021.

Like so many members of the group, Morgan shares a rich history with the UO community. Her son attended and graduated from Oregon and was part of the marching band. Ever since he started in 2010, Morgan has been the chair of the marching band through the Daisies as a way to show her support.

13 years later, Morgan is one of the the only Daisies to ever serve twice as president. The president facilitates weekly meetings, maintains organization across all sports the Daisies help with and represents the Daisies during booster meetings. With the start of the university’s fiscal year on July 1, a Daisy begins their year-long term of presidency after serving a mandatory year of vice presidency.

How a historic volunteer group connected to the University of Oregon Athletic Department has evolved and remained relevant over time.

At the women’s lacrosse game, the Daisy Ducks gathered at mid-field to be recognized. With smiles on their faces, the Daisy Ducks celebrate 50 years as an organization.

Morgan took over the presidential reins in 2021, during a time of pandemic-related uncertainty, after no Daisy wanted to step up to fill the shoes of Kay Thompson, the president in 2020. Thompson herself was grateful.

“I didn’t want to be the last president of Daisy Ducks. We’d just been through too much as a group,” says Thompson. “Someone had to come forward. Thankfully, Barb came through.”

A member since 2000, when she’d attend the weekly meetings during her lunch breaks, no one has seen the Daisies change first-hand like Morgan.

“Through the years, the NCAA rules and regulations have really changed,” Morgan says. “When we started, we were able to do more things, but now we don’t want to step on any toes or get the university in trouble. Plus, the athletic department has gotten so good that they don’t need our help like that.”

Then, of course, several other men, like Mann, have joined the group.

“The organization has evolved with the rest of the world,” says Karsten. “We include all genders. Some of us are also more aware of the buzzwords that people use now that help understand what we’ve been doing all along, which is tending to the mental health of the athlete. We’ve never used those words in the old days. We were just very open-hearted.”

Karsten graduated from the UO with her graduate’s degree in 1973 and her master’s in 1991. She’d managed Meals on Wheels in Lane County for Senior & Disability Services before, which required hundreds of volunteers.

Upon Karsten’s retirement in 2019, she was searching for meaningful things to do with her free time. That fall, at a UO football game, she overheard a woman a few rows in front of her talking about the Daisies. That woman was Lynda Hadeen, the president at the time, and a current member. Hadeen has been a mentor and great friend of Karsten ever since.

“In order for the Daisies to live on, it needs to perpetuate amongst new people,” says Hadeen.

Much like Hadeen ignited the spark for Karsten to join, Morgan was a big reason Hadeen joined. Morgan’s husband had served as her accountant, and she heard about the Daisies through him. When it was time to end her 30-year career working at the campus Duck Store, Hadeen decided to join the Daisies, too.

There’s a classic story that floats around the Daisies about a past member who taught a student athlete how to use a washing machine and dryer by taking them back to their home and demonstrating many years ago. The story is seen as a humorous legend within the Daisies now, but it doesn’t stop them from reflecting on its meaning.

“When we first started, we saw ourselves as moms and grandmas to the athletes,” says Karsten. “We try to see them more as whole people and less as a product. I sometimes think in college sports that it’s a product now. This product is made up of real people who are at a vulnerable stage in their lives.”

Much like the Daisies were forced to adapt to current times, they were also forced to adapt to COVID-19.

When the pandemic hit the United States in March 2020, the Daisies didn’t meet until two school years later, in September 2021. Members had to wear a mask and be up to date with all their shots in order to attend meetings. Goodie bags weren’t brought back until October 2022. The yearly potluck for student athletes has yet to return.

But all is far from lost. The Daisies still bake for the student athletes at a plentiful rate. Volunteers are back at Matthew Knight Arena during every men’s basketball game, hoping to sell bingo cards that’ll raise money for athletic scholarships. They currently have one scholarship endowment for $150,000, and are hoping to add a second in the future. The group still leads each meeting with the fight song and invites new guest speakers to their weekly Tuesday affair at Roaring Rapid Pizza Company in Eugene.

“What a fun, caring, connected, spirited, resourceful group of Duck fan doers they are,” says Garry Weber, an operating partner of Roaring Rapids Pizza Company.

As the Daisies have helped UO athletics for decades, the appreciation has gone both ways.

As president of the Daisies, one may attend an away Oregon game with the trip fully funded. Hadeen and her husband

Ioenescu, Ruthy Hebard and more. Morgan went to Tucson, Arizona, in 2016 to see Oregon snap Arizona’s 49-game home winning streak in men’s basketball. Thompson once got to see Oregon play at the Seattle Seahawks field in Seattle, Washington, when the University of Washington’s football field wasn’t playable.

“We’re the only organization of its type in the United States and the NCAA,” says Hadeen. “There’s no organization like it. It’s a heartfelt organization that loves the student athletes and loves Oregon.”

Currently, Karsten, Thompson and other Daisies are facilitating the Daisies 50th year anniversary celebration. The festivities have already begun with tailgate parties, and this May, a banquet at Shadow Hills Country Club marks the final celebration. The Daisies are also working to get recognized at each sporting event, too.

Looking to the future, the Daisies hope to continue emphasizing the importance of giving back to the community for another 50-plus years.

“I do think the world needs more people actively helping people with similar interests, for their own good and the good of the community,” says Karsten. “It’s very challenging for people to realize that human-to-human contact is really important, and giving back is really important.”

Daisies Terry Spencer, Karen Donner and Anne Smith, connect and watch the lacrosse game as it heats up. These members may not know about the world of lacrosse, but their love for sports and the University of Oregon have brought them together.

A growing grassroots effort to transform wildfire policy and our relationship with fire.

Nathan Wilson

Turner

Written by

| Photographed by Violet

and Paris Snider | Illustrated by Miles Imai

Nathan Wilson

Turner

Written by

| Photographed by Violet

and Paris Snider | Illustrated by Miles Imai

As a lifelong west coaster, Kyle Trefny grew up around wildfire. He remembers how summer smoke would consume San Francisco’s bay and filter into his high school, where fellow students coughed incessantly.

As Trefny watched friends and relatives evacuate under the threat of losing their homes, he grasped how severely wildfires impacted people’s lives.

Now 20 years old and a junior at the University of Oregon, Trefny not only remains intimately fused to wildfire but is actively working to transform how fire management operates on a national scale.

Over the past few months, Trefny has collaborated with a diverse group of young, fire-focused leaders to develop, build power around and present a vision to the United States Forest Service (USFS), the Department of Interior (DOI) and other government officials. It’s called the FireGeneration Collaborative, or FireGen for short, and their ask is simple: to provide young people, particularly those from Indigenous and other marginalized communities, with the space to influence wildfire policy-making.

“We can tangibly feel the crisis we’re facing,” says Trefny. “We’re not comfortable just letting go and waiting for our turn to come to power through the traditional system — we need solutions now.”

As of 2021, 72% of wildland firefighters are white and less than 16% of wildland firefighters are women, according to a recent U.S. Government Accountability Office report. While data on queerness in the fire workforce is not available, Trefny says that as a queer firefighter, he has experienced related challenges firsthand. In addition to firefighting being a homogenous profession, young people already have and will continue to be more exposed to the effects of climate change than older generations.

These factors motivated Trefny’s involvement in the campaign for equitable representation in wildfire policy-making, as did his experiences on the frontlines. In the summer of 2021, Trefny began firefighting with an Oregon-based wildland fire and forest restoration company after witnessing one of the worst fire seasons in American history a year earlier. In 2020, wildfires burned over 17,000 structures in the U.S., more than tripling the annual average, according to a National Interagency Coordination Center report. Yale Climate Connections estimates that the fires directly killed 43 people, and due to smoke impacts, they are estimated to have indirectly killed thousands more.

In the aftermath of 2020, Trefny says the growing risks of firefighting jobs and outdated federal labor policies set up the perfect storm: a severely understaffed fire workforce in the face of another intense season. As the Bootleg and Dixie fires ignited in Southern Oregon and Northern California, Trefny says federal agencies devoted almost all their labor force to the West Coast. But Trefny and his crew weren’t just needed on the West Coast. After extinguishing a fire in Eastern Oregon, they traveled to Montana where they remained for nearly 50 days. During that time, they realized they weren’t receiving the

support they needed to safely work on the blaze.

“We didn’t have many people in Montana,” Trefny says, “and there weren’t enough eyes on the fire.”

Short-handed and under-equipped, the firefighters found themselves in a hazardous position as weather conditions worsened and the originally small fire exploded in size. Rather than creeping across the ground, the flames jumped from treetop to treetop, forcing Trefny and his crew to take refuge in an already burned patch of trees.

Trefny says this was a systemic safety failure.

“You’re supposed to know well in advance when a crown fire is coming towards you, because that’s the most dangerous form of fire,” he says. “Instead, we had to just stay on the hill as it passed around us.”

Thankfully, Trefny and his crew emerged unscathed, but the experience stuck with him because it was a concrete example of how the Forest Service’s policies endangered lives on the ground. The Forest Service compounded this danger with other measures that limited controlled burns and managed wildfires, which would improve the health and safety of both communities and landscapes.

In May 2022, about a year later, Trefny attended the International Fire and Climate Conference in Pasadena, California. Surrounded by researchers and fire scientists, Trefny listened as Randy Moore, chief of the USFS, gave a speech about the importance of reintroducing fire to American landscapes, despite his contrasting policies.

Trefny was the first to raise his hand in the crowded room once Moore finished. With Montana in mind, Trefny asked Moore, “In regards to accumulation of risk onto today’s young people and young firefighters, how can us young people work together with you to shape policies that include our disproportionately-impacted voices?”

To Trefny’s surprise, Moore noted that the USFS has policy collaboratives around the country and could envision a policy collaborative with younger generations. “Email me,” said Moore.

In that moment, the vision for a young collective shaping fire policy commenced and has been gaining momentum since. Trefny quickly began organizing and scheduled meetings in Washington D.C. with Moore, along with 12 senate offices, where he would formally pitch FireGen in November 2022. However, Trefny knew he couldn’t represent an entire diverse generation alone — so he assembled a team.

Trefny first turned to Dr. Timothy Ingalsbee to advise his efforts. Ingalsbee is a professor in the Department of Sociology at the UO, a former wildland firefighter and the founder of a nonprofit organization called Firefighters United for Safety, Ethics & Ecology (FUSEE). Trefny

connected with Ingalsbee during his freshman year at the UO and worked with the organization for two years. Ingalsbee has escorted firefighters to D.C. several times in the past and has experience navigating those spaces of power, so leaning on Ingalsbee to guide his younger team was a no-brainer for Trefny.

Along with advising, Ingalsbee also helped Trefny build his team. At a graduation party, Ingalsbee spread the word about FireGen to Ryan Reed, a now-graduated UO student, Indigenous fire practitioner, wildland firefighter and member of the Hupa Tribe in Northern California. Reed was immediately intrigued by the idea, and with his commitment, FireGen launched at the end of summer 2022.

“I always grew up with folks who didn’t understand certain concepts of what it is to be Indigenous or what the environment meant to Indigenous peoples,” Reed says. FireGen’s purpose aligned with Reed’s personal missions.

Trefny met the remaining two members of FireGen, Alyssa Worsham and Bradley Massey, at another fire-related conference in October 2022. Worsham graduated from the University of California, Los Angeles, with a bachelor’s degree in environmental science, and is currently pursuing her master’s in environmental management at Western Colorado University. Unlike the others, Worsham is more research-oriented, currently examining prescribed fire use in designated wilderness areas.

Massey is a forestry student at Alabama A&M University and is the co-captain of the university’s wildland fire crew called the FireDawgs. Alabama A&M is the only Historically Black College or University (HBCU) with an accredited forestry program, and Massey’s presence ensures that the Southeast, a region where fire management is typically overshadowed by the West Coast, is incorporated into the group’s focus. With his decision to join FireGen, Massey rounded out Trefny’s team. Once together, the “D.C. Coalition” still had much to prepare before they traveled to the East Coast. They needed to research all the officials they were scheduled to meet with, determine the structure of FireGen and figure out what narratives would guide a successful pitch.

Leaning into their organizing abilities, the team launched the FireGen Challenge: a three-week think tank intended to answer lingering questions around FireGen and provide the D.C. coalition with tangibles, like an informational booklet and presentation, to support their pitch. Made up of the UO’s Student Fire Alliance and other fire-focused advocates, the challenge succeeded in defining FireGen and, through rigorous petitioning, amassed a body of support totaling over 2,000 people in more than two dozen states across the U.S. Right after the challenge, the group hurried to Washington D.C. for their first meeting with Moore and John Crockett, the associate deputy chief for state and private forestry, on Nov. 15, 2022.

The evening before, Trefny found himself unable to sleep, as months of work reached its culmination point.

FireGen as a generation of people. Our generation and future generations are headed into a fiery world, a pyrocene, where we are both the most-impacted stakeholders in decisions, and dependent on the sociopolitical transformation this world requires.

FireGen as generating fire.

This present era of crisis calls for a generational rejuvenation of using fire led by Indigenous people, management, and knowledge. We must heal relations with the land that sustains us while revitalizing cultural and prescribed burning.

Firegeneration = regeneration. We need regenerative economies, and a regeneration in our lifestyles, ecosystems, and relationships that makes reciprocal interconnectedness the foundation of our human and more-than-human communities.

En route to the Forest Service headquarters the following morning, Trefny soothed his nerves with a little bit of Taylor Swift. Soon enough, they were walking past Gifford Pinchot’s original desk and into the meeting room with Moore. Then FireGen began its most crucial pitch.

During the meeting, Massey says Moore and Crockett broadly stressed the importance of implementing diversity in their workforce and in their workplace. According to Trefny, Moore and Crockett also acknowledged that young people are really missing in the decision space and pledged that the D.C. coalition can continue collaborating with the Washington headquarters on meaningful representation for young people in wildfire policy-making. The group proceeded to build relationships with senators, members of the DOI, and other government officials. Everywhere they went, those in power wanted to listen, an experience that was very impactful for Reed in particular.

“Not very many people, especially in my community, have the opportunity to speak with senators or any folks of high leadership in the political realm,” Reed says. “So just being in that atmosphere was surreal.”

However, before this whole ordeal began, Reed knew that centering Indigenous perspectives in wildfire policy wouldn’t be an easy task, given the history of Indigenous burning and oppression in the United States.

“The only folks who have ever lived with fire cohesively and in an organized structure are Indigenous,” Reed says. “Since contact, fire has been eradicated. It’s been violently prohibited and separated from nature. It was viewed as a very savage, very primitive way of operation.”

The systematic oppression of fire has been incredibly damaging to Indigenous peoples because fire is often an essential cultural practice. Fire not only teaches ecosystem management, which Indigenous peoples rely on for sustainability and sustenance, but also informs Indigenous identities.

“When we sever this cultural practice of putting fire back in the landscape, then essentially, our culture is dying,” Reed says.

Along with preserving and uplifting Indigenous culture, FireGen is seeking to disrupt hegemonic narratives about wildfire. Ever since its conception in 1905, the USFS has distorted the way mainstream society thinks about fire. Through advertising campaigns like Smokey Bear, the USFS has consistently painted fire as a destructive force that must be suppressed at all costs, which enables the agency to paint burned landscapes as lifeless and justify profit-generating activities like post-fire salvage logging. Recognizing the colonialism, patriarchy, militarism and exploitative capitalism embedded in the fire suppression complex, FireGen wants to instigate ideological change, trailblazing the way to a future where society can coexist with fire.

“We need to reframe our mindset to show that fire is not the problem and recognize that we can use fire to our advantage and make both our communities and ecosystems safer,” Worsham says. Since young people and other marginalized groups don’t shy away from confronting the status quo, Tref-

July 2021:

As a result of poor federal labor policies and stretched resources, a crown fire jeopardized the safety of Trefny and fellow firefighters while on assignment in Montana.

Summer 2022:

The FireGeneration Collaborative initial team comes together, Ryan Reed, Bradley Massey, Alyssa Worsham and Kyle Trefny, with advising from Professor Tim

Ingalsbee

November 2022:

The D.C. coalition embarked towards the East Coast to discuss FireGeneration Collaborative, or “FireGen,” with gover nment officials.

ny says, it’s critical these voices are represented in decision making to initiate this restructuring.

By working to change our collective understanding of fire, FireGen is also engaging with the various equity issues in the fire world. One of the reasons that Trefny was initially drawn to wildfire was because of this intersectionality: wildfire acts as a window into many forms of structural injustice.

In order to think critically about the modern moment FireGen is addressing, along with these ongoing, structural struggles, Trefny credits Dr. Catalina de Onìs, a professor in the Clark Honors College that specializes in environmental justice and Latine/x studies. Like Ingalsbee, De Onìs was an important mentor for Trefny. FireGen broadly unites structural injustice in the fire world under one goal of intergenerational justice. It centers around the idea that present generations have a responsibility to protect the livelihoods of future generations while mitigating disproportionate impacts, Trefny says. Where De Onìs really influenced Trefny, though, is recognizing that intergenerational justice also means learning from past social movements — that all contemporary justice struggles are rooted in a long history of grassroots activism.

“I think when you’re a new organization, especially as a white person in this space, it’s important not to enter these spaces thinking I have the answers and we’re the solution,” says Trefny. “We need to have a level of humility when we’re gaining power and recognize that we have a lot to learn from.”

May 2022:

Trefny asked USFS Chief Randy Moore about young representation in wildfire policy making at the Intern ational Fire and Climate Conference in Pasadena, Californ ia.

October 2022: With the help of UO students and fire-focused community members, the group launched the FireGen Challenge to figure out how to pitch the initiative and gather support.

January 2023:

The D.C. group received a $20,000 grant from Wonder Labs to fund their initiatives, including research and listening projects that will guide future directions for FireGen.

With their trip to the East Coast months in the past, the D.C. coalition is now figuring out how to bring FireGen to fruition. Trefny says their first step is listening. The D.C. coalition recently got into contact with Wonder Labs, a social enterprise located in San Jose, California, that provides funding through the Living with Fire Design Challenge for student-led fire resilience projects. The D.C. coalition successfully applied for a $20,000 grant and is planning on conducting a research and listening project to determine barriers, opportunities and needs for fire resilience and restoration across communities of young people. This decision, to do extensive information gathering before pursuing action, will help FireGen in two ways.

First, it will allow a wider variety of young people to voice the challenges they face, how they want to be involved in the fire world and how communities should respond to the climate crisis, says Trefny. The results will provide FireGen with a breadth of potential solutions and policy initiatives before the collaborative formally begins. Second, ”by doing all this listening and forming community connections, we’re building a network that can then be leveraged to both fill and provide power behind the spaces of access FireGen seeks,” Trefny says.

Even though the D.C. coalition is months away from completing their project with Wonder Labs — and even farther from making the FireGeneration Collaborative a reality — he remains confident about their endeavors, in part because of the support from other similar organizations. Through connections with leaders in youth climate organizations like the Sunrise Movement, the D.C. coalition will incorporate the experience of other mass organizers to develop FireGen, Trefny says. Ultimately, Trefny recognizes that establishing FireGen will be a slow process, but he believes that FireGen can be part of uniting labor, social justice and environmental movements, all under the banner of fire.

“I know that young people are bold, and we’re going to help hold those spaces accountable to our best long-term interest and speak for all sorts of people who can’t be in those meetings,” Trefny says. “Our generation has shown we can do that when we’re able to have some power, so I’m really excited for what that would mean.”

de Onís, Trefny and Ingalsbee pose on the University of Oregon campus in Eugene. Trefny first met Ingalsbee through his work with Firefighters United for Safety, Ethics, & Ecology (FUSEE), and met de Onís through her work as a professor in the Clark Honors College at UO.

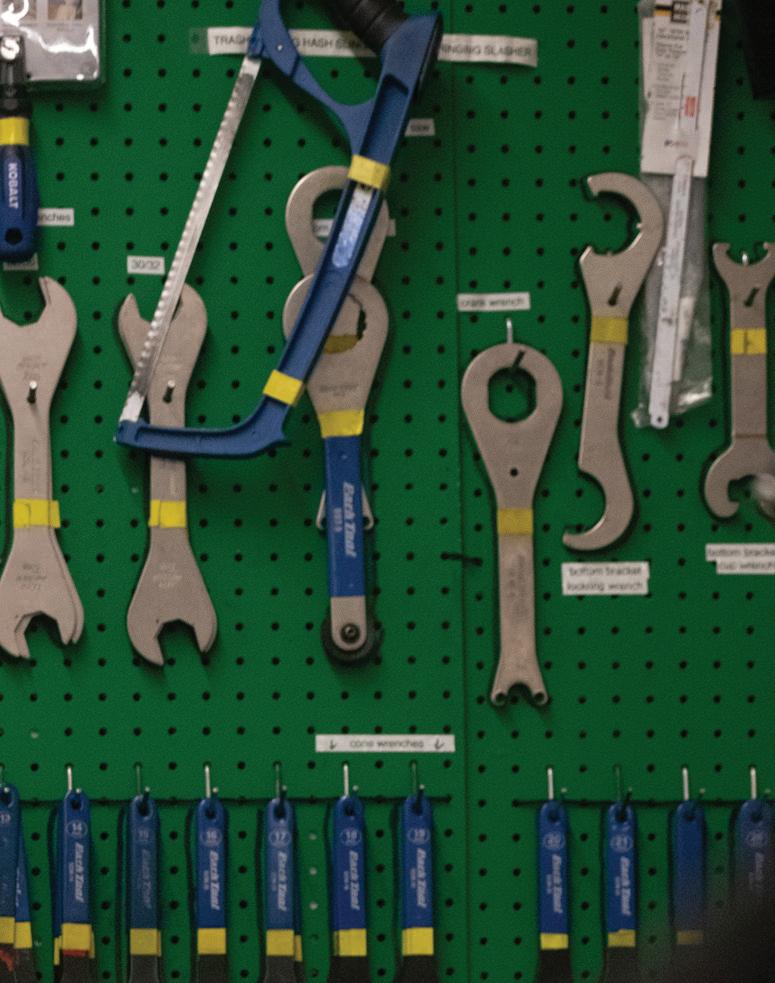

Annika Mayne, Mare McLevy and Ducky Joseph teach at the UO Outdoor Program’s Winter 2023 Femme, Trans, and Womyn Identified Folk’s (FTW) Bike School. As the outdoor world has increased its focus on accessibility, many women, gender-nonconforming and transgender students still find themselves intimidated by male-dominated bike shops and communities. FTW seeks to change that. Covering the basics of bike maintenance, from fixing flats to adjusting brakes, the course gets students confident with their abilities to fix their own bikes. FTW aims to create a warm, friendly and fun environment for those who stop by, and to make space for queer, femme and otherwise identifying individuals to build community while also building skills.

UO Bike Program’s Femme, Trans, Womyn Identifying Folk Bike School creates an inclusive space for students to learn and connect.

UO senior Annika Mayne is an avid biker with accessibility on their mind. When Mayne steps into the course to teach, they say they’re not just going to work. They’re going for their community. For Mayne, FTW provides an opportunity for queer, trans and femme students to find support and confidence in a field that’s too often exclusionary. FTW is unique, says Mayne, for teaching bike mechanics “in a way that’s queer and inviting, with other really cool queer and trans people.”

Queer, trans and femme specific spaces like FTW need to exist to make the bike world truly accessible, according to Mayne. “I am someone who loves the outdoors and am confident in my outdoor skills, and I am intimidated in masculine bike shop spaces,” Mayne says. At the shop where they worked previously, Mayne was the only employee who wasn’t male. They felt uncomfortable presenting as gender-nonconforming and gay in that space, which they describe as straight-man dominated. Anytime a woman or femme client came in, they experienced an immediate connection. “I was able to communicate mechanical knowledge in a way that wasn’t talking down,” Mayne says. This experience solidified Mayne’s dedication to making changes in the biking world, inspiring them to teach at FTW with their coworkers McLevy and Joseph (seen above).

FTW is a six-week course that the UO Outdoor and Bike Program has run every term for the last year. From 5:30 pm to 7:30 pm, a varied group of students — from undergrads to non-UO community members — come in from the cold and help each other learn to fix their bikes. It evolved out of previous iterations dating as far back as 2015, when it was just “women’s bike night.” Later, it was WTF (Women/Trans/Femme), but instructors took cues from gender equity movements within biking and renamed it to Femme/Trans/Women in order to center queer, trans, nonbinary, and gender nonconforming folks. While the course is $65, the program provides scholarships to students who need them. Accessibility is a hallmark of FTW, according to Mayne. They say that the program “very much fits into my personal philosophy of getting people outside, but doing it in a way that doesn’t just say it’s accessible.”

Many UO students rely on bikes for transportation, yet far fewer are equipped with the skills to fix and maintain them. Combine unfamiliarity with an outdoor “bro-culture” that people like Mayne are trying to change, and learning how to be self-sufficient can feel daunting. “Outdoor spaces, especially in Oregon, are often super male-dominated,” Mayne says. “That’s especially prevalent in bike mechanics.” According to a Zippia estimate, 5.4% of bicycle mechanics are women and 94.6% are men, and only 4% of bike shop employees are LGBTQ+. A report published by the Professional Bike Mechanics Association showed that an estimated two-thirds of bike shops had all-male service departments. FTW combats historical exclusion from the repair and maintenance world with their by-us-for-us model, where femme, trans, gender-diverse and otherwise identified employees instruct similarly identified students.

“The essential aspect of biking is that it’s a thing that can get you places,” Mayne says. They say that biking doesn’t have to be high-level or expensive to be worth investing time in, especially since many rely on bikes for everyday transportation. Mayne defines accessibility as giving someone a key to a space, such as biking, and letting them do whatever they please with it, rather than handing them a set of rules.

“The

amount I’ve learned at the bike program is so exponential compared to my other bike experiences,” Mayne says.

“It’s such a community environment that’s really built on teaching each other.”

“Nobody knows where the Veterans Center is,” says Becca Thomas, a University of Oregon student and employee of the Veterans Center. “I mean, it’s past the bathrooms.”

The Veterans Center is hidden down a long hallway on the bottom floor of the Erb Memorial Union on the UO campus. The room itself is modest, lined with tables to work at and hosting a coffee and snack bar, but the huge American flag hanging from the ceiling is what catches most people’s eyes. The space is small and getting there requires a map, but to veterans and dependents — parents, spouses or children of veterans — like Thomas, this place is a safe haven.

According to the Veterans Association, approximately 2.7% of students at the UO are using a G.I. Bill to pay for their education. The G.I. Bill has been providing veterans and/or their children with tuition assistance since it became a law in 1944. People who have served in the military for more than two years can qualify for tuition assistance, free college, free vocational school and counseling services.

However, figuring out how to receive these benefits is a hurdle in itself that requires sifting through lots of complex paperwork. Most veterans at the UO visit the Veterans Center to get help figuring out how their G.I. Bill can benefit them, but end up sticking around for the community.

“It sort of acts as a transition hub or decompression zone,” says Jacob Pixler, a UO student and Veterans Center assistant coordinator.

The Veterans Center not only answers G.I. Bill-related questions, but they also hold events like the Veterans Outdoor Club, connect people with mental health resources and provide a space where veterans can feel understood.

To serve in the military, one signs a contract to serve an agreed-upon number of years, which makes a majority of veterans older than the rest of the student population. James Lamping, a UO graduate student and veteran, says the age gap is the biggest reason veterans tend to feel isolated on college campuses.

“The mindset is just, ‘I don’t get these people, and I don’t understand how this place works and I don’t feel like there’s anybody on this campus that relates to me,’” Lamping says.

As a graduate student, Lamping has already gone through the experience of adjusting to a college campus post-military service. After serving in the navy for six years, Lamping decided to go back to college for forest ecology at Humboldt University. It was there that he first felt these feelings of isolation on a college campus.

“I didn’t know anyone, really, my first year,” Lamping says. “I was living in an RV park like six or seven miles away from campus, and it was just hard to meet people.”

Eventually, he started seeking out the veterans’ center on campus and discovered Humboldt’s outdoor program for veterans. The program planned hikes, mountain biking trips, kayaking, skiing and more. Lamping loved the program so much that when he came to the UO for graduate school, he decided to build a veterans’ outdoor program from the ground up. His goal is to give veterans a chance to bond through nature and to show them that being outdoors can be a fun and meditative experience rather than a difficult chore.

“It’s just kind of reframing that mindset to show them that outdoor recreation here is fun and more of a healing device than it is like an arduous task,” Lamping says.

For Lamping, finding community through the Veterans Center was how he made it through his undergraduate years. However, he recognizes that finding the center is a challenge.

“I’m hoping that things like the outdoor program will make the Veterans Center more visible,” Lamping says.

Pixler pointed to the lack of diversity in experiences and identity at the UO as part of the reason it’s difficult for veterans to find community.

“There’s a very specific path most people have taken to get here, including professors,” Pixler says.

Pixler was 22 years old when he traded his neon orange construction vest for army green. Pixler says he could try to come up with some grand and heroic reason for joining the military, but in all honesty, he was bored. He was living with his dad in West Virginia, a place he loathed, working a job he didn’t really enjoy and craved adventure.

Pixler wanted to jump out of airplanes, so he hit the ground running and headed straight for a military recruitment office. He told the recruiters that he wanted to be a paratrooper — someone that parachutes out of airplanes. The recruiters denied his request, saying he would have to be a water treatment specialist before he could become a paratrooper. Pixler now knows that was a lie to try and fill a quota. Regardless, he took the job and was deployed to Iraq soon after.

Pixler worked his way out of water treatment specialization early on in his deployment and began working more on logistics for the Special Forces unit, which meant he was coordinating movements of personnel and equipment from place to place. Pixler’s special forces unit used one of Saddam Hussein’s palaces as a place to stay and store equipment.

Outside the layers of concrete barriers that enclosed the base was Baghdad. Pixler would venture into town when given the chance to pick up bootleg DVDs, eat better food and hangout with the locals. When Pixler was deployed, he never really questioned why they were in Iraq.

“We were fighting terrorism,” Pixler says, “or whatever that meant.”

Pixler says that even among the leadership in the military, the “why” was rarely discussed.

After serving in Iraq for eight months, Pixler was relocated to Mali for a few more months and spent his final deployment in Germany for a few weeks. It wasn’t until after coming home that Pixler began trying to make sense of the “why.”

“After the war in Ukraine started, a bunch of veterans joined to go and fight with Ukraine,” Pixler says. “Some of them were asked why they went and they said it felt like a justified war. They felt like they were actually fighting for something. And I think that sort of speaks to what it felt like to be in Iraq. Like, nobody knew what they were doing, why they were there, you know?”

Katie Roles – another UO student and veteran – joined the military for a similar reason to Pixler.

“Pretty much anyone that joins the army is looking to escape from wherever they are in life,” she says.

Roles was so desperate to leave her hometown of Sacramento, California, she enlisted in the army before she graduated high school. Within a few weeks of her high school graduation, Roles was off to Georgia for training.

Role’s first deployment was in South Korea. She looks back on that time in her life fondly.

“I was single. I had no bills, no responsibilities,” Roles says. She says she just got to have fun for six months, until her money ran out, leading her to cut back a little.

Roles spent a year in South Korea meeting new people, volunteering at a local orphanage and supporting the local businesses around the base. She says for the most part, the locals had positive attitudes towards the military, but closer to Seoul, people were less enthused.

“The college students held a yearly demonstration,” Roles says. “We were always told never to leave our post and stay away from Seoul during those times.”

After returning from South Korea, Roles moved to Colorado and continued working for the military doing office work for three years. During Roles’ service in South Korea and Colorado, she injured both of her feet and had to undergo surgery. Because of these injuries, she was able to file for medical discharge, which would release her from her military contract.

When Roles discovered she was pregnant, she immediately signed the paperwork to leave the military on medical discharge. She says her decision to leave the military was solely to spend time with her son.

“I knew what it took for single parents to be in the military, and I couldn’t do that,” Roles says.

Roles’ discharge date was September 19, 2001; six months after her son was born. Now, 22 years later, her son is active duty in the military. Similar to his mother, Roles’ son joined the military straight out of college. Roles was supportive of her son’s decision to serve, but told him he had to have a plan.

“I was clueless when I joined the military,” Roles says. “I told my son if he wants to go into the military, he’s gonna pick a job that has a civilian equivalent, so he can have a job when he comes home.”

Roles is happy to guide her son through his journey in the military, but she is simultaneously learning that a lot has changed since she served. Roles is seeing through the eyes of her son that things are mostly changing for the better.

“They’re definitely more aware of the fact that when they don’t let soldiers heal from injuries, they become chronic,” Roles says.

She explained that when she was serving, it wasn’t uncommon for physical and mental health to be ignored. Now, she says the military is much better at managing their soldiers’ wellbeing.

After Roles left the military, she needed a job. She tried going to a small animal veterinary technical school, but after a year and a half of attending school, working upwards of 30 hours a week and raising her son, she was burnt out. So, she decided to wait to go back to school until her son was out of the house.

As soon as her son graduated, Roles returned to school to pursue a passion she never had the chance to do: architecture. She packed up her life, moved to Eugene and is now enrolled in the UO architecture school.

Likewise, Pixler decided he was finished with his adventure after four years of serving in the army and wanted to challenge himself by going back to school, too. He started out at community college and has since transferred to the UO as a history major with minors in philosophy and sociology.

Pixler, like many others, didn’t realize the Veterans Center existed. When he finally found it, he thought he was too late in his college career to need it. It wasn’t until he saw a job posting for an assistant coordinator position at the center that he fully immersed himself in what it has to offer.

“I was letting self-reinforcing isolation do its work, and then I saw this job and I thought about what it was like to self-isolate,” Pixler says. “That’s why I wanted that job. I wanted to find the people who were looking for other people.”

Pixler wasn’t the only one looking for other people. In fact, loneliness seems to be a string connecting each person in the Veterans Center.

Becca Thomas had no intention of getting involved with the Veterans Center when she first started college, but her experience growing up with a military dad made her long to be surrounded by people who could understand her.

“There’s a big feeling of alienation on campus, because of traditional students not really understanding,” Thomas says.

Thomas’ dad served in the military for 18 years, 10 of which he was active duty. As a dependent, Thomas wasn’t

sure if she would find a place at the center, but she says all her worries about that have subsided.

“When I was a kid, I just hated the military, because they were taking away my dad from me,” Thomas says.

Thomas still has complicated feelings towards the military, but has become increasingly passionate about helping veterans and their families get the support they need. Mostly, Thomas wants people to understand the distinction between supporting the military and veterans.

“I think for a lot of larger society, it’s really hard to separate the political issues that the military is involved with versus the people who are in the military,” Thomas says. “And as much as we can criticize why the military is doing what it’s doing, I think that it’s just as important to see the people that are really hurt by it and to support them any way you can.”

Thomas’ time spent at the Veterans Center has influenced her to go into counseling for veterans after college, where she hopes she can continue helping veterans feel accepted back into society.

Thomas and the other students found the center in their own time, but now that they’re here, it’s difficult to imagine campus without it. It’s a community that transcends age and race by being built solely upon a deep understanding of one another’s experience living in a world vastly different than that of their colleagues.

“I mean, it’s not therapy,” Thomas says, “but it’s kind of unity.”

A toy soldier wades through a sea of ducks. The Veterans Center is decorated with its own unique combination of Oregon and military paraphernalia.Birth Control

Abortion

Emergency Contraception

STD Testing & Treatment

Vasectomy

Gender Affirming Care

And More...

The current batch of Bunk+Brew seasonal employees have become fast friends. After long days on the slopes or at their other jobs, they greet each other with a beer and a debrief. “I ended up finding community that I didn’t know I needed,” says Sydney Utsey.

It’s February 25, 2023, and I’m driving east along Highway 126 to pay a short visit to Bunk+Brew Hostel in Bend, Oregon. My goal is to find out more about the elusive world of seasonal employment and collect interviews that will inform my process. As I gain elevation over Santiam Pass, snow and slush crunch under the tires of my 2012 Volkswagen Tiguan. I’m confident that my four-wheel drive will carry me safely to my destination, but that confidence wavers when I check the forecast during a pit stop.

I’ll definitely make it there, but making it back is looking more questionable by the minute. Consistent predictions of snow flurries blanket the forecast, but I decide to keep chugging along, as I’ve already come this far.

“If I get stuck, then I get stuck,” I mumble to myself as my wheels catch on another patch of slush. “I’ll just play it by ear.”

By the time I depart from the hostel, it’s Wednesday, March 1. My one night had turned into four, and my understanding of the seasonal work lifestyle – and just how quickly one can become immersed – had forever changed.

“It’s like the Hotel California,” says Ada, a Bunk+Brew employee. “You can check out, but you can never leave.”

The Bunk+Brew Historic Lucas House in downtown Bend has been acting as a landing pad for travelers and seasonal workers since its inception. The structure, built in 1910, holds the title of the first and oldest brick building in Bend. Bunk+Brew houses people from all walks of life, so there’s no shortage of stories to absorb once you step inside.

The hostel culture puts an emphasis on the “Dirtbag” lifestyle, as it’s described by each and every employee who comes through the revolving door. Dirtbag, as a term, encompasses the idea of living for the experience – even if that means getting your hands dirty in the process. It can mean jumping from seasonal job to seasonal job or sticking around somewhere long enough to plant roots, as long as each day involves adventure and unconventionality. The Bunk+Brew Dirtbags might live in a van, within the hostel walls or in a converted school bus like Colette Beckmann, general manager of the hostel. The Dirtbag ideology is loud and proud on their website and social media pages, but most importantly within conversations around their shared identity.

The Bunk+Brew campus is made up of three buildings. The main building – the Historic Lucas House – currently houses around eight seasonal employees. In the summer, this number can get up to 20. The employees live on the top floor – dubbed the Penthouse – and the hostel guests take up the bunks and private rooms on the second floor. The Annex House is the other residential building and can hold up to 16 residents. The Bathhouse is the final building on campus and holds three showers and the famous sauna that keeps people coming back for more. There’s even a beer garden in The Backyard, with their own Bunk+Brew beer truck. Other food trucks are available for guests, residents or any local who finds themselves hanging out by the firepit.

Each Bunk+Brew employee is – somewhat – seasonal. According to Beckmann, they do all of their hiring from Workaway, which is an app for seasonal workers to find employment and housing in the location of their choice. Each employee works three shifts a week to cover their rent, and is required to stay for a minimum of only three months.

“I can never see myself working in a nine to five,” says Beckmann. “A lot of us are fed up with that being the only option.”

Once Beckmann found Bunk+Brew, it always seemed to draw her back in. She originally started working at the hostel while spending the winter at Mt. Bachelor as a ski instructor. Beckmann immediately fell in love with the community, and kept it close to her heart during a year-and-a-half long stay in Baja, Mexico. She returned to Bunk+Brew as the assistant to the general manager and was running the place within a month. That was two years ago, and Beckmann has called the hostel home ever since.

“It was everything I was looking for,” she says. “I’ve met so many wonderful, amazing people.”

Beckmann has committed this era of her life to helping the nomadic find a place that feels like home among the chaos. She recently spearheaded an effort to partner with Mt. Bachelor, so some of their seasonal employees can stay in the Annex House for an affordable price. The Annex can hold up to 16 residents for only $350 a month.

“That is the cheapest lodging you’re gonna find in Oregon, let alone Bend,” says Beckmann. “If you’re paying 800 or 900 bucks in rent, why would anyone come back to work for the mountain again? It all starts with housing.”

The rising cost of living in Bend has been a hot button topic among locals and largely has to do with the travel industry and the new influx of wealthy residents. According to a study done by Construction Coverage, Bend’s fair market rent prices rose by a margin of 37.4% between 2019 and 2023, as outlined in a report by Jack Harvel of the Source Weekly. The study attributes this steep incline to the U.S. underinvesting in housing before pandemic-induced disruptions to the workforce. The average studio apartment usually costs about $1,000 a month, and a one-bedroom apartment runs around $1,184, according to Construction Coverage’s study and Harvel’s reporting.

According to Glassdoor, a ski instructor at Mt. Bachelor makes an average of $17 an hour, which is simply not enough to sustain a comfortable lifestyle within the city limits. Lift technicians, baristas and other entry-level positions endure an even lower hourly wage.

“That’s why I’m so passionate about this,” says Beckmann. “People like me should be able to live in places like this. It’s so amusing when everyone asks, ‘what’s going on with our ski towns? Why is this happening?’ It’s because no one is diverting funds – like real funds – to support the people that make or break the resort.”

The tourism industry has experienced a boom since the pandemic. In popular tourist towns such as Bend, upper-class residents are quickly flooding the city limits

and driving up the cost of living while they’re at it. For many pre-existing residents, living in Bend is slowly making less financial sense. The community around the hostel set out to solve this issue, one bunk at a time.

“All leads back to this really similar rhetoric, which is taking care of the small guys,” Beckmann says.

Ada, who chose to go by her first name due to privacy concerns, is one of the youngest Bunk+Brew employees at only 20 years old. She never expected to end up living and working at the hostel. Originally from Salt Lake City, Utah, Ada began working at the front desk of Atlantic Aviation directly after graduating high school. She stayed in Salt Lake City for work but found herself craving something different.

In the summer of 2022, Ada began working at an outdoor camp near Bend. She found the Bunk+Brew community by accident, after an Airbnb fell through the cracks. Within a night, she ended up bonding with nearly everyone there.

Ada didn’t live or work at Bunk+Brew over the summer because she spent four months camping in her car and working at a summer camp for kids. Her days

started with a coffee and a bagel and nearly always ended with a dip in the river. She spent much of her leisure time with people from the hostel, and they even helped to build her Nissan Versa into a temporary home.

“I was living purposefully,” Ada says. “It felt so good – I was just fulfilled.”

Ada’s off-the-grid summer indoctrinated her into the Dirtbag life. Each day was a new opportunity to experience the world with low stakes and low stress. The adjustment from fast-paced, everyday life caused her to shift her perspective.

“The amount of times I’ve caught myself being bored, it just means I’m literally existing,” Ada says. “A lot of people think being bored is bad. But in reality, you could just be at peace. It just

feels boring because it’s not chaotic or stimulating.”

After her seasonal summer job was over, Ada went back to Salt Lake City to live at home and work as a gymnastics instructor. She found herself bit by the travel bug and was anxious to get back to a similar lifestyle as before.

“There was no purpose for me to be there,” she says.

Ada decided to buy a van so she could travel, work seasonal jobs and live day-by-day. The van she purchased was back in Oregon, so on New Year’s Eve, she made the trek to pick up her new mobile home and drive it back to Salt Lake City. Little did she know, she wouldn’t make it back.

150 miles outside of Bend, her back tire fell off the rims on the highway. She slipped on a patch of ice, and the car rolled over into a snowbank. Luckily, she ended up not getting hurt, but she was stranded and alone with nothing but the totaled remnants of her new home. After a while, two people pulled over to help her out: a father and his daughter, who was a nurse.

“She checked me out,” Ada says. “That was the day that I believed angels existed. People are just so kind. It’s ridiculous. You don’t know how grateful I am that I ended up okay.”

They gave her a ride to Eugene and bought her a hotel room. After spending a week in the city, Ada changed her plans for good.

“I stayed in Eugene for a week and contemplated my whole life,” she says. “That’s how I ended up working here, pretty much.”

Ada returned to Bunk+Brew as an employee and quickly got a job in one of the kitchens at Mt. Bachelor. She’s been living in the Penthouse ever since, with only the amount of clothes she originally came here with. She found a way to be happy with her circumstances, despite the wrench in her original plan.

However, not everyone found the hostel in dire circumstances. Many Bunk+Brew seasonal workers are looking for a change post-grad, instead of continuing on to a typical nine to five. Sydney Utsey is a Bunk+Brew employee from Neww Jersey who attended Morgan State in Baltimore, Maryland. She studied economics during her undergrad and decided to make a change instead of continuing on to graduate school.

“I would have been stressed if I went back to school,” Utsey says. “Honestly, during my last semester of senior year, I felt like I was suffocating.”

The American Psychological Association’s Stress in America study found that adults aged 18 to 23 – Gen Z adults – suffer from significantly more stress than previous generations. Of those attending college, 87% of the participants said that their education was significantly linked to high stress. High amounts of stress are directly linked to student burnout, according to the same study.

Utsey described East Coast higher education culture as a “rat race.” As the hustle and bustle wore her thin, she made a pledge to try something new after graduation. She came to Oregon in August 2022 and committed to Bunk+Brew’s three-month minimum for employment. She fell in love with the hostel – and the idea of snowboarding – and has been there ever since.

“It’s just a difference of cultures,” Utsey says. “I become more mature in dealing with my emotions and not just

suppressing them. I’ve been more unapologetic about who I want to be, unlike before, where I would be a little nervous expressing who I am.”

Utsey, like many others, found solace in the simplicity of seasonal housing. For now, she is content with working at Bunk+Brew as well as a hotel downtown. She plans to spend her youth traveling and continuing to forge relationships along the way. Utsey says in her hometown, the status quo involves settling down early with a spouse and a career.

“Some people like that familiarity and comfortability,” Utsey says. “Personally, I’m just so curious about the world. I want to experience it all and then determine what I want to do with this existence.”

I resonated with Utsey’s reflections on student burnout. As an active UO student who was spending time at Bunk+Brew when I should have been at school, I actively questioned why I was spending so much time, money and mental energy on a degree. This is a conversation

I’ve had a million times over with my peers, and the conversation usually ends with a yearning to break our seemingly-endless routine. After getting to experience the other side, I can’t say that I didn’t want to join them.

But there’s two sides to every coin. During my fourday stay at Bunk+Brew, I spoke with many residents – off the record – about being a college student versus doing seasonal work. While everyone loved what they were doing, many people talked about how they sometimes wished they went to college and got a degree, just for the sake of security. This is not to negate the fact that many people staying there had completed a degree or were actively in school online.

Utsey’s story is just one example of Bunk+Brew employees accidentally stumbling upon a life-changing community. CJ Vermillion, a previous Bunk+Brew guest-turned-employee, actually got hired just minutes before our interview. Originally from the Washington

D.C. area, Vermillion moved to Bend two years ago to work at Mt. Bachelor. He returned to D.C. only to find that he had been bit by the travel bug and was anxious to come back.

Vermillion returned to Bend on a trip, found Bunk+Brew and fell in love with the community and lifestyle. After some time going back and forth, he decided to extend his trip indefinitely and moved into the basement the day after our conversation.

“I really immersed myself,” Vermillion says. “I just kind of became part of the hostel. I’m excited to see how everything plays out.”

Vermillion’s speedy induction is not uncommon. For most employees, it doesn’t take long to decide they want to work here and really immerse themselves in the flow of everything. Most guests-turned-employees share a few things in common. They need a change of pace, they value solitude as well as tight-knit community and they want every day to feel meaningful – and fun.

“We all have our own preferences and paths we’re gonna go on,” says Vermillion. “For me, I value experience. So I like doing this stuff right now, especially when I’m still young.”

After announcing that he got hired, Vermillion was met with excitement and warm embraces. He’s excited to start this new chapter and lean into the Dirtbag lifestyle.

One day at the Bunk+Brew can feel like five, and I found that Ada’s comparison to Hotel California wasn’t far off-base. Most guests and employees are gone throughout the day – working, riding the mountain, climbing or hanging out with friends. There is always someone on shift, which involves manning the front desk, doing dishes and changing out bunks for the next batch of guests. The nights, however, are when the hostel comes alive.

There always seems to be a deeply involved game of chess at the dining room table and a TV show on in the living room. Everyone takes turns cooking dinner, and I found that someone was happy to share their meal with me each night. Locally brewed beer is tapped, poured and shared among familiar and fresh faces, and everyone has plenty of stories to share late into the night.

On the first night I stayed at Bunk+Brew, I walked right into a pre-birthday-party gathering. After an hour, I had joined an impassioned game of hackysack, been given a celebratory fake mustache and gotten on a first-name basis with a well established group of friends. Bunk+Brew brings out the welcome wagon for whoever comes through the door.

In the wintertime, the hostel nightlife is usually pretty contained, except for a night or two a week where they invite local artists for live music. But according to Beckman, in the summertime, something is always happening.

“All summer it’s three to five days of live music, jam bands, karaoke, open mic, ukulele nights - it’s just endless here,” Beckmann says.

But on top of all the excitement, Bunk+Brew lends itself to solitude and serenity. There’s always a place to escape and someone to escape with – if one so desires. I found that each person I spoke with values internal peace above all else. That’s the thing that sets this community apart from those who revolve around hustle culture – within the Dirtbag lifestyle, time to breathe is a priority. Balance is a necessity. Adventure is what happens when that cup has already been filled.

“I’m definitely more open-minded,” says Utsey. “I’m becoming more in tune with my emotions. I’ve been able to live in my truth more and become myself more authentically.”