MONDAY, DEC. 1, 2025

Prison education interns work with local nonprofit to support formerly incarcerated adults

UO students who are part of the Prison Education Program volunteer at Sponsors, Inc. to assist released convicts.

MONDAY, DEC. 1, 2025

Prison education interns work with local nonprofit to support formerly incarcerated adults

UO students who are part of the Prison Education Program volunteer at Sponsors, Inc. to assist released convicts.

By Aishiki Nag Opinion Columnist

The holiday season is right around the corner; this often means trying new recipes, baking for your loved ones and sharing a meal with your family or friends. But what often gets overlooked are the numerous farmworkers who make your recipes a reality.

Farming is labor-intensive, and the U.S. currently has 2.9 million agricultural workers to meet market demand; nonprofit Farmworker Justice estimates that 70% of current farmworkers are immigrants, of whom 40% are undocumented. Immigrants are crucial to ensuring our communities have the food we need.

Continue

The hidden work behind hosting a house show

EDITOR IN CHIEF

Tarek Anthony

PRINT MANAGING EDITOR

Ryan Ehrhart

DIGITAL MANAGING EDITOR

Ysabella Sosa

NEWS EDITOR

Reilly Norgren

INVESTIGATIONS EDITOR

Ana Narayan

A&C EDITOR

Claire Coit

SPORTS EDITOR

Jack Lazarus

OPINION EDITOR

Gracie Cox

PHOTO EDITOR

Saj Sundaram

COPY CHIEF

Olivia Ellerbruch

VIDEO EDITOR

Jake Nolan

PODCAST EDITOR

Stephanie Hensley

SOCIALS EDITOR

Ysabella Sosa

VISUALS EDITOR

Noa Schwartz

DESIGN EDITOR

Adaleah Carman

DESIGNERS

Eva Andrews

Asha Mohan

Nina Rose

PUBLISHER AND PRESIDENT

Eric Henry (X317) ehenry@dailyemerald.com

VP OPERATIONS

Kathy Carbone (X302) kcarbone@dailyemerald.com

DIRECTOR OF SALES & DIGITAL MARKETING

Shelly Rondestvedt (X303) srondestvedt@dailyemerald. com

CREATIVE & TECHNICAL

DIRECTOR

Anna Smith (X327) creative@dailyemerald.com

ACCOUNT EXECUTIVES

Torin Chevalier

Camcole Pereira

Ava Stephanian

Elliot Byrne

THE DAILY EMERALD

The Daily Emerald is published by Emerald Media Group, Inc., the independent nonprofit media company at the University of Oregon. Formerly the Oregon Daily Emerald, the news organization was founded in 1900.

Emerald Media Group 1395 University St.,#302 Eugene, Or 97403 (541)-346-5511

By Billie Corsetti News Reporter

University of Oregon students interning at the Prison Education Program volunteer three days a week at Sponsors, Inc., a nonprofit organization in Eugene that provides a variety of support services to formerly incarcerated adults in Lane County.

UO’s Prison Education Program was first established in 2016 and aims to improve educational opportunities in prison by facilitating discussion between students with diverse backgrounds and perspectives to promote shared learning and growth.

PEP gives students the opportunity to attend “Inside-Out” classes, where UO students, called “outside” students, learn alongside imprisoned adults inside the prison, or “inside” students. Inside students are incarcerated at either the Oregon State Penitentiary, the Oregon State Correctional Institution or Coffee Creek Correctional Facility.

Students can also participate in internships at the program, where they help guide classes, work with student applicants and develop other projects for incarcerated people.

PEP interns are offered the chance to support incarcerated individuals once they’ve been released by volunteering at Sponsors For 90 days, participants of Sponsors live in transitional housing units provided by the organization while program workers help them to find employment, healthcare and community resources.

“The goal is that at the end of the 90 days that people are at Sponsors, they have a care team in the broader community that can support them for years to come and they have a stable source of income and stable long-term housing,” Kelly Denmark, director of the Reentry Resource Center at Sponsors said.

Sponsors began a formal partnership with PEP in fall of 2024, with interns initially visiting the center twice a week, which has since gone up to three times a week. Interns help create workshops and presentations and work one-on-one with participants.

“I’ve always been a people person, and I

love to help people and be able to see the impact of that continued volunteering and building those relationships,” Beatrice Kahn, a PEP intern, said. “I really enjoy helping participants with one-on-one support. In the past, I’ve helped with job applications, especially creating resumes and draft cover letters.”

Interns have also been able to incorporate their own personal experiences and interests in their work. Siqi Zhao, one of two international students in PEP, works with participants at Sponsors to help reconnect them to their culture in the Eugene area.

Zhao hopes to pursue a career in immigration law and use that passion to develop resources for previously incarcerated immigrants, refugees and people of color.

“Recently, I was working on a flyer for cultural activities in Eugene… a lot of people that use this program don’t have access to their culture,” Zhao said. “I was interested in that because of my cultural background. I was born in China, but I grew up in Mexico, so I understand the struggles that immigrants, and especially re-entry individuals, have to go through every day.”

For PEP intern Rory Forsythe-Elder, having unconventional interests compared to other interns has only enhanced his work at Sponsors. Being a spatial data science and business admin major, rather than the usual political science, Forsythe-Elder has become the unspoken “tech guy.”

“A lot of (participants) haven’t been accustomed to technology in five, 10, sometimes 15 years,” Forsythe-Elder said. “So it’s been pretty cool helping them even with basic stuff, like setting up their emails and applying for jobs.”

Forsythe-Elder attributes his involvement at Sponsors to an Inside-Out class he took last fall, which motivated him to apply for a PEP internship.

“I just kind of fell in love with the program and the idea of having classes in prisons, and having half students on campus and half incarcerated individuals was novel to me,” Forsythe-Elder said. “I wanted to

apply and stay with the program, especially because you’re limited to taking one Inside-Out class in college.”

All three of the PEP interns believe that seeing students involved in these programs is important to the services provided by Sponsors.

“For people who have been released from prison, Sponsors is the first stop off,” Kahn said. “So when they see energetic, enthusiastic young people who are spending and volunteering their time to offer support, it really helps strengthen relationships between the university community, as well as the broader Eugene community.”

The mutual impact on students and participants is vital to the partnership between PEP and Sponsors, leading to increased services provided by Sponsors and giving students hands-on experience.

“I think if someone is interested in working in social services, it’s really important to have an understanding of what direct services really look like and what serving individuals with unique needs looks like,” Denmark said. “To be guided and mentored in that work through an internship can be really valuable. In turn, we also really love to see people come to us with passion and ideas. I think the combination of both allows us to give the best care for the people we serve.”

The affiliated fraternity is the subject of an early-stage investigation following a report of hazing activity.

By Elle Kubiaczyk News Reporter

The University of Oregon Police Department is currently investigating the fraternity Delta Sigma Phi for hazing allegations. It joins Kappa Kappa Gamma, a sorority, as a Greek life organization under interim suspension.

On Nov. 1, UOPD received a report in response to hazing allegations at Delta Sigma Phi, followed by a report on Nov. 2 to the Dean of Students office.

Once a report is submitted, the Dean of Students office determines if enough information is available to continue the investigation and “spend a few days corresponding with potential witnesses associated with a report,” Dianne Tanjuaquio, senior associate director of student conduct, said. Kappa Kappa Gamma, a sorority, also faces interim action. UOPD is not part of the investigation into KKG.

In both cases, the Dean of Students found there to be enough information to proceed with an investigation and issue interim action to both KKG and DSIG on Oct. 27 and Nov. 7, respectively.

In accordance with the Student Conduct Code, interim action is reserved to “address a substantial and immediate threat of harm to persons or property.” Both organizations are currently under temporary suspension from new member activities, group communication, and events and programming, as seen on the Dean of Students webpage.

According to UOPD Police Chief Jason Wade, there is no set timeline for both the police or the university’s investigations. They can range from weeks to months.

Hazing is defined by physical brutality or unreasonable risk of harm, including the consumption of substances that could affect the person’s health.

RealResponse, a private reporting service for members of greek life released in February, allows students to report hazing anonymously.

Jimmy Howard, associate vice president of student life and dean of students, attributes the increase of drink, drug tampering and hazing reports, in part, to RealResponse.

Once a report is submitted, the extent of law enforcement involvement is somewhat dependent on the wishes of the student who reported the incident. Many “may not want a criminal investigation if one is afforded to them,” Howard said.

UOPD is directly involved in the DSIG investigation due to having been specifically contacted by an affected student.

Following interim action, the Greek organization’s national headquarters is contacted, followed by an interim action appeal meeting and a formal Notice of Allegations is issued to both KKG and DSIG. KKG appealed the interim action to no avail.

A Notice of Allegations includes a description of the alleged misconduct, the specific violation of the Student Conduct Code, assignment to a case manager and a date and time for the informational meeting in which a student organization representative — oftentimes the president — can informally review the report.

At the informational meeting, a time is set for the Administrative Conference. In this meeting between the case manager and student organization representative, the student organization can formally respond to the allegations. Witnesses can be provided to the case manager ahead of the conference and are interviewed but cannot be forced to answer specific questions.

Organizations are not required to participate in the process, Howard said. “We hope that they participate and

move forward with us in a transparent and honest way.”

Proceeding an administrative conference, the case manager may conduct additional investigations or make a final decision.

UOPD conducts the investigation in a “more independent version” than the Dean of Students, Wade said.

Witnesses may be referred to Student Life after speaking with UOPD, or vice versa. Neither investigative party wants to “step on each other’s toes,” Wade said, which might ultimately harm each other’s investigations.

UOPD and the Office of the Dean of Students have varied amounts of evidence needed to charge a student organization or member with a violation.

“(UOPD has) have to have probable cause to make an arrest or charge,” Wade said.

Additionally, UOPD has to consider if there is substantial evidence to reach a conviction in court — that the suspect, beyond a reasonable doubt, committed a crime.

The Office of the Dean of Students instead reaches a conclusion on whether DSIG or KKG violated the Student Conduct Code based on a preponderance of the evidence — “it’s a lesser version of what we’re trying to do,” Wade said.

If KKG or DSIG is found to be in violation of hazing policies, an action will be issued which outlines potential consequences ranging in severity from a conduct warning, probation or suspension.

As KKG and DSIG are both affiliated student organizations, suspension means losing university recognition.

“Suspension is reserved for more serious matters, and hazing could be one of those,” Howard said.

( BELOW ) Exterior of Delta Sigma Phi on E 18th Ave. Eugene, Ore. on Nov. 26, 2025. (Adaleah Carman/Emerald)

Opinion: With the holiday season coming up, it’s important to acknowledge the contested history of labor protections for farmworkers and the struggles they continue to face.

In recent months, the Trump administration has rolled back key measures in protecting migrant workers. One of the key changes has altered the way H-2A wages are calculated, with an estimated $5 to $7 of wage reductions per hour. This would lead to an overall $2.46 billion less paid to temporary workers annually.

“This rule marks a major shift in wage-setting authority from the US Department of Agriculture to the Bureau of Labor Statistics,” Alexis Lisandro Guizar-Dias, electoral field director for Pineros y Campesinos Unidos del Noroeste, wrote in a statement. “While the department claims this will make adverse effect wage range determinations more consistent and data-driven, there is concern that using occupational employment and wage statistics data may lower wage floors in some regions, particularly where agricultural work has historically been undercounted or undervalued.”

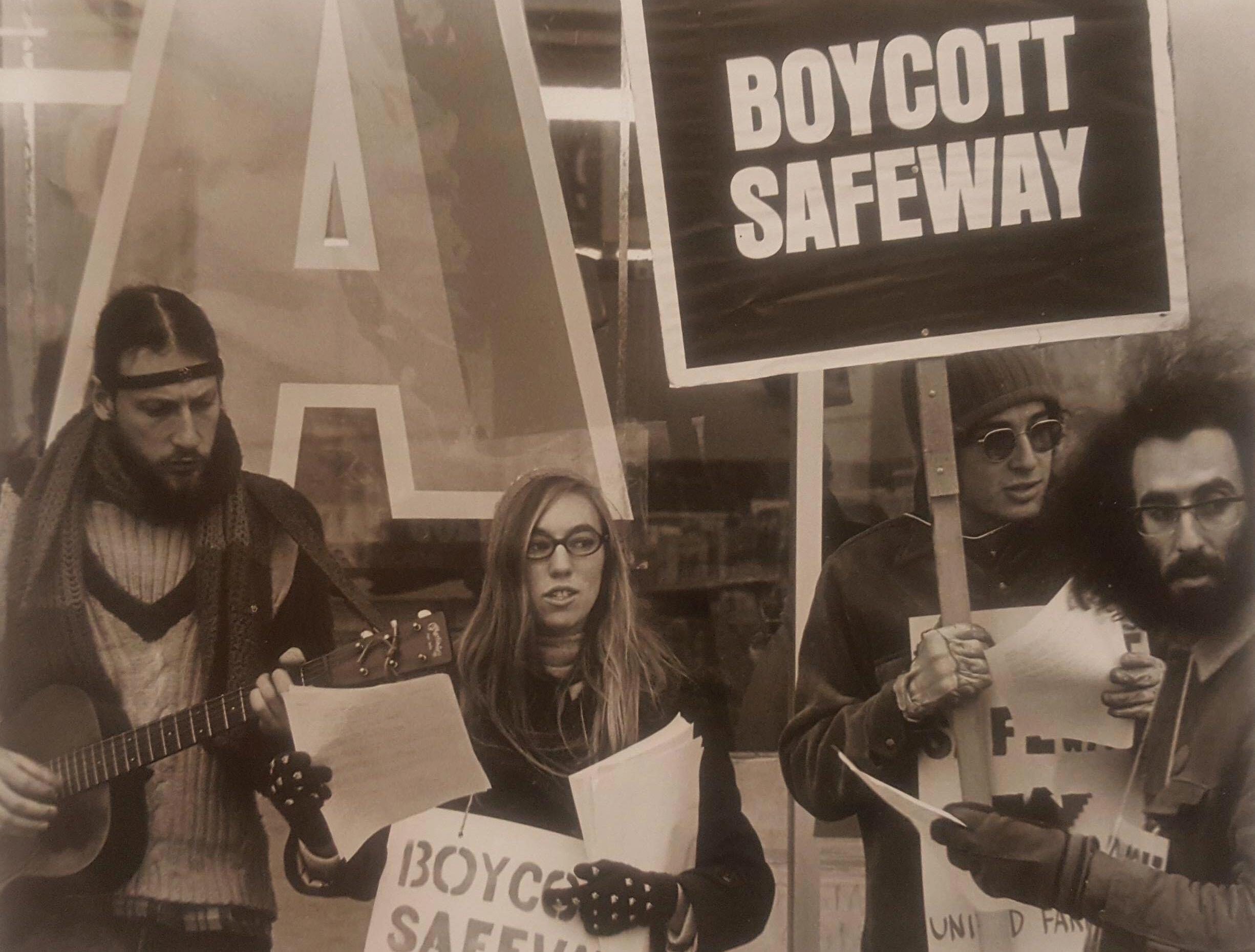

Historically, farmworkers have represented one of the least protected labor sectors, with agricultural workers specifically being left out of the National Labor Relations Act. Their initial calls for collective action and unionization started with the grape strikes in 1965, which gained popularity and led to the national movement by Cesar Chavez. They organized with local worker unions, community organizations, faith-based organizations and colleges to build support for the United Farm Workers boycott — the first and largest agricultural worker union in the U.S. Eugene, in particular, has a long history of supporting farmworker movements, with the Eugene Friends of Farm Workers emerging in 1972 to advocate for migrant labor rights. They had a large presence in our community, handing out leaflets and protesting in front of Safeway, organizing an on-campus boycott of the Erb Memorial Union food services and participating in national efforts to support the UFW.

Nancy Bray, a labor activist and member of EFFW, mentioned her past as a farmworker herself. She noted the poor living conditions, the grueling labor and the lack of labor protections for workers in general. She continues to speak out about the conditions of farmworkers currently, mentioning the impact that ICE raids are having and the recent rollbacks by the Trump administration.

“Arrests of farmworkers have increased dramatically in late October and November,” Bray said. “Thirty farmworkers were arrested in Woodburn on Oct. 30 on their way to work. Sixteen immigrants, of whom nine were farmworkers, were arrested in Salem on Nov. 11, and then here in Lane County on Nov. 5, some of those who were arrested were forest workers.”

Bray is currently organizing to raise awareness for the Windmill mushroom boycott. For the last three years, farmworkers at Windmill Farms have been fighting for union recognition in Washington due to poor working conditions, health violations and continued mistreatment. Workers have been known to face very long hours, with no set exit times, and large quotas to fulfill to retain their jobs. The farmworkers who have supported the union have faced undue adverse actions, including job termination.

In December 2024, UFW announced an official boycott against Windmill Farms until the company recognized the union. Oregon farmworker unions PCUN and the AFL-CIO are also supporting the boycott.

“You can’t just be aware; you have to actually move to action,” Bray said. “I do think a consumer boycott can be very effective, but it takes time — the more people who are aware, the better.”

Collin Heatley, a rank-and-file member of the Graduate Teaching Fellows Federation, has been working with UFW to spread the word of the Windmill Farms boycott. Heatley tried to centralize autonomous picketers in Oregon to have an organized force and reached out to many labor unions, activist organizations and faith organizations in the community. He has also worked on collecting signatures for a petition supporting the boycott.

“We all go to grocery stores, we all buy produce — how do we get those folks to not buy these mushrooms or (communicate) that there’s a boycott going on and how do we make sure they’re moved to not want to buy them?” Heatley said. “That comes from the people they trust, which are their labor unions, activist organiza-

tions or their faith-based groups.”

Especially with the holiday season coming up, a peak consumption time for mushrooms, people have a chance to make an impact and fight for dignified working conditions at Windmill Farms.

“Every worker deserves to be treated in a dignified way while they’re on the job — they deserve to be paid fairly and work in safe conditions,” Heatly said. “And we as consumers have the power to change that.”

To support farmworkers, advocates like Heatley and Bray strongly urge shoppers not to buy mushrooms from the following stores, since they are primary carriers of Windmill mushrooms: Winco, Safeway, Albertsons and Fred Meyer. They urge people to shop locally and to double-check the brands they are buying from.

Bri Garcia, UO MEChA’s financial director, attended a talk by Bray in late November. Garcia mentioned how she was drawn to the talk because of Eugene and UO’s strong history of labor organizing for farmworkers.

“My family has been in the farmworking industry for the longest time and has supported farm working causes,” Garcia said. “Years ago, they were boycotting grapes and boycotting lettuce. It’s upsetting to know this is still a problem — farmworkers should be taken care of and they provide food for everyone.”

It’s important to pay homage to the rich history of labor organizing and collective action that allowed farmworkers to fight for a more dignified workplace. This fight continues, and allows for our community to participate and show solidarity to the struggles farmworkers are facing when fighting for better work conditions — and the first action to take is not to support Windmill Farms.

is a

studying political science and global studies. She likes to cover state and national politics and international peace-building efforts. When she’s not writing for the Emerald, she likes to read, hike and travel to new places.

The sustainability dilemma at the heart of community living

Community leader and social rights activist Mo Young has been helping people all her life. Now, she wants others to do the same.

By Noa Schwartz | Ethos Writer

Mo Young’s childhood Christmases were a busy time of year. She went with her mother, father and brother David to shop for Christmas presents. The siblings carefully picked through the rows of red and green tags shaped like Christmas ornaments, each with a name printed on it. Every tag represented a child in need of a present. Once they had their tags, they took care in picking the perfect gift for a kid they had never met. It wasn’t a chore, it was a family tradition.

Since those early Christmas drives, Young has known nothing else but giving. It’s in her blood, she said. She described her mother, born in Keizer, Ore., as a “small-town white lady” with a big heart. She described her father, a Black man from Philadelphia, as a “hippie of his time,” one who spent his younger years hitchhiking across the country. The two both went to law school at the University of Oregon where they met at a local bar playing pinball.

Her father became an administrative law judge for the state while her mother became a circuit court judge. Public servants through and through, as she described.

“It was sort of drilled into my head, this is how we exist in the community,” Young said. “I was just raised that way.” She clarified that they always asked if people wanted help before stepping in. “We never assume,” she said. “Sometimes when you just talk to people, magic happens.”

All her life, Young has made magic happen. She grew up in Eugene and went to UO for her bachelor’s degrees in psychology and sociology, graduating in 2002. After a year in New York working in a wine store, she returned to Lane County where she has been ever since. She started running a program at Community Alliance of Lane County called Back to Back: Allies for

Human Dignity, centered on combating antisemitism, racism and heterosexism across the county. She also partnered to start the Stop Hate Campaign, a community led project that encourages reporting incidents of harassment or hate crimes. The program helped FBI investigators track down Jacob Laskey, a notorious white supremacist. She left the job in 2007 and became the county’s positive youth development coordinator. Although it was only for a couple months, she enjoyed her time there, and is now commemorated with a mural behind WOW Hall. After a stint in Lane County Public Health, she was hired as supervisor of the Community Partnerships Program, where she has been for four years.

As much as she loves her leadership role, she lives for working with people. She is constantly looking for opportunities to “plug into the community so that I can get that cup filled. I feel that in my bone marrow.”

Her parents weren’t her only role model. When he was in college, Young’s brother David was paired with then UO advisor Lyllye Reynolds-Parker, a local legend and force for civil rights. She was a Black community leader of Eugene. Her family helped found Ferry Street Village, a historic Black community that was demolished in 1949 in order to build what is now Alton Baker park. She spent her life fighting for racial justice and is now the namesake for UO’s Black Cultural Center. According to Young, she saved her brother’s life.

While at UO, David went through “severe and persistent mental illness.” Aunt Lyllye, as her students call her, was a light in a dark time for them both. “I have no doubt that she saved his life. She was a soft place to land for so many people that didn't have one or didn't trust the one that was supposed to be there for them.”

Over the years, their relationship grew. Young lived right down the street from Aunt Lyllye, and would regularly check in on her. She was a “blueprint” for Young, an example of how to live in an unkind world.

“She showed up until the very last day with no judgment. Ms. Lyllye was, besides a dearly beloved family member, a role model of how to exist in a world that is not gentle.”

In February 2020, Ms. Lyllye was helping Young film a video to promote COVID-19 vaccination efforts. That day, Young was finally given the chance to give back to the woman that had saved her brother.

“She told me there was a ghost in the house,” Young said. Aunt Lyllye wanted to move out of her cramped apartment with her sister, but didn’t have the money to put a down payment on a house. Later that night, Young sent her a note asking for permission to raise the money. She never assumed, she just asked. And magic happened.

After about eight months, the fundraiser had amassed over $100,000, plenty for the house she bought and moved into shortly after.

Two years later, on Aug. 22, 2024 Ms. Lyllye passed away at the age of 78. Young says that helping her buy a house toward the end of her life is still among his proudest moments, but she insists she was just a messenger of the community’s support. Without Aunt Lyllye’s connection to the hundreds of people she helped, the money could have never been raised.

“The community loves Ms. Lyllye,” she said. “She did the work. We just gave people a really tangible way to say thank you.”

Just as Ms. Lyllye was a role model for her, Young is now a mentor to young people learning to navigate their lives with kindness. In 2018, Young was awarded the Martin Luther King Jr. Connecter Award by the NAACP in Eugene, honored at their annual Freedom Fund Dinner. In 2021, the Eugene Human Rights Commission awarded her its International Human Rights Day Award. In 2022, she received the Heritage Excellence Award

from Eugene’s Historical Society. Still, she has some difficulty accepting comparison to her dear friend and mentor.

“Don’t y’all know I make mistakes all day long?” she chuckled. “This is what happens when we put people on a pedestal. We forget that we’re just human and we’re fumbling around just like everybody else.”

With leaders like Ms. Lyllye gone, it’s Mo’s turn to step up. Of course, mentorship has no instruction manual, but Young is learning as she goes. She has long conversations with her 22 year-old niece who is involved with the Trans Alliance in Lane County. She doesn’t always have answers, but she is always happy to listen.

“It's been delightful to not just tell her what to do, but to listen to where she's going and her reasoning and ask questions to help her hone in on what the right path is,” Young said.

In a time as uncertain as ours, there is no shortage of young people afraid for their future. Many of the pillars Ms. Lyllye and Young worked their whole lives to erect are now on shaky ground. Even the word “equity,” which was once in Young’s official title, is not permitted to be used in an official capacity. And yet, young people continue to fight to protect what they believe is right. Young is inspired by what she sees. She wants “people with new energy” to pursue their passions. There are many like Young who will always be drawn by a deep-rooted need to help people. It may be frightening, but bravery thrives in fear.

“All of us are scared,” she smiled. “And somehow, that makes it less scary. The lesson there is, do it scared. Isn't that the definition of courage?”

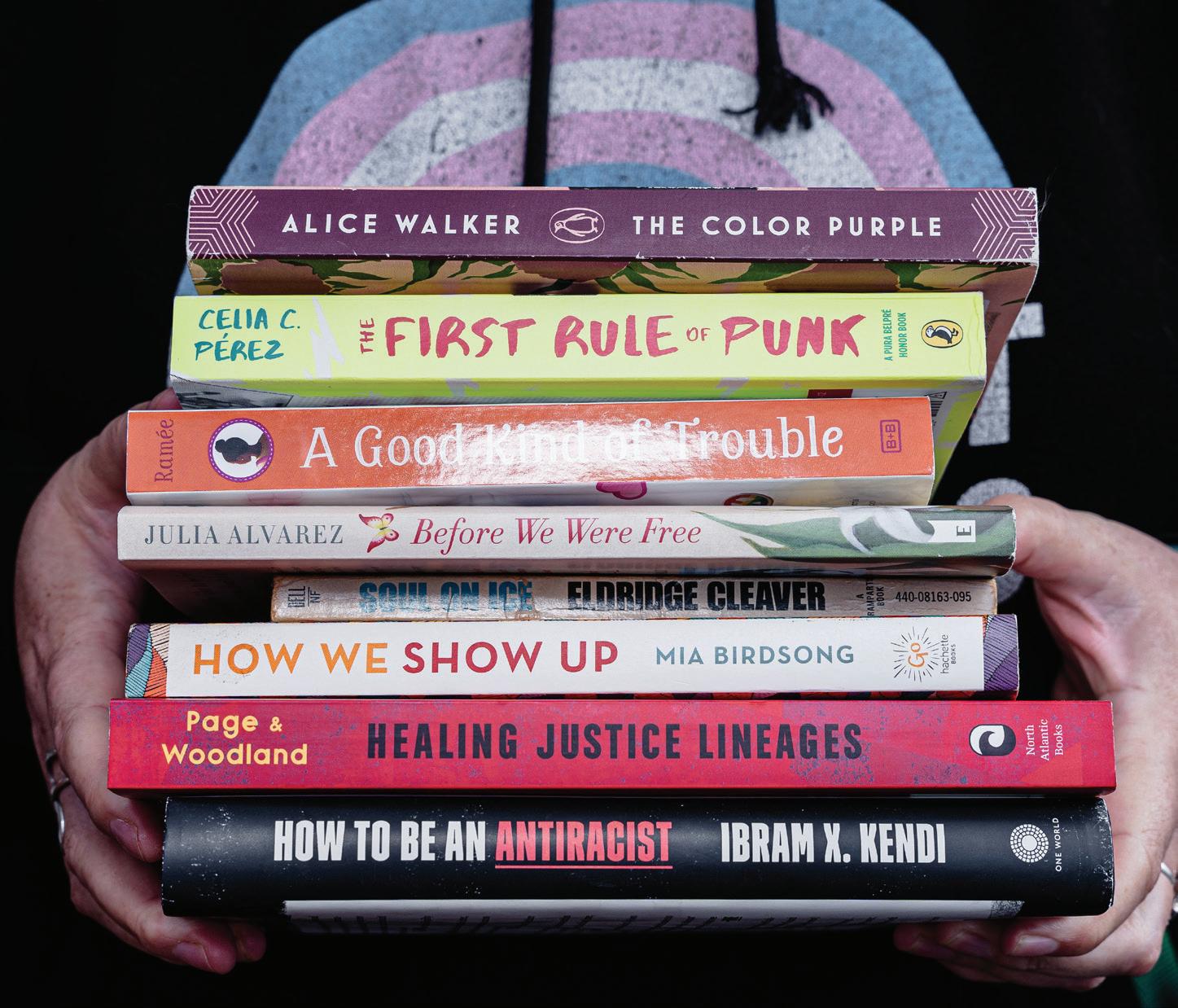

( ABOVE, LEFT ) Lifelong Eugene activist Mo Young poses for a headshot next to a Little Free Library filled with books on queer expression, carceral justice and antiracism. The library is painted with the words “Good Trouble,” a reference to civil rights activist John Lewis. (Jordan Martin/Emerald)

Meadowsong’s experiment in cooperative, ecologically-grounded living reveals how fragile shared ideals can be when labor, accountability, and emotional labor fall unevenly across a community.

Tucked into the misty foothills of Oregon’s Willamette Valley, Lost Valley Education Center sits quietly amid a landscape of towering evergreens and rolling fields. Up the hill, a small campus of modest classrooms blends into the forest, surrounded by trails where lessons in permaculture and regenerative living take root.

Down below, wooden cabins are scattered along winding paths, their moss-covered windowpanes catching the soft glow of evening light. A yurt glows warmly in the dusk, and the communal kitchen buzzes with the sounds of dinner preparation. Vans and tiny homes are scattered across the campus alongside garden plots and signs pointing to basketball courts and tree-laden river posts. Solar panels catch the afternoon sun in a field that edges into thick woods, while a nearby cob-made sauna sends gentle steam into the cool air.

This collection of spaces forms Meadowsong, a 36-year-old intentional community where homes and shared areas cluster together, bound by narrow paths and a shared purpose. Residents range from young families and recent University of Oregon graduates to long-term members, all drawn to cooperative living, shared resources and ecological ideals. But sustaining that vision over decades requires more than good intentions.

Lost Valley emphasizes ecological sustainability through conservation, permaculture and cooperative living. Its programs, from Permaculture Design Certificates to youthfocused environmental education, offer immersive experiences in harmony with nature. At dinner, potatoes are piled into a huge oven, a woman wrangles the hens and residents stroll about, catching up as the sun sets.

Lost Valley depends heavily on tuition, grants and volunteer labor. Infrastructure maintenance, land ownership and programming demand steady income and manpower. This is where idealism and pragmatism collide: the desire to offer accessible, community-centered education often conflicts with the financial and logistical realities of keeping the place running.

Financially, tuition and program fees account for over 70% of Lost Valley’s revenue. The organization uses a tiered pricing system to promote accessibility, yet it continually struggles to balance inclusivity with financial sustainability. Only 18 individuals are responsible for maintaining a compound that serves about 50 residents.

By Lily Reese | Ethos Writer

Of these 18, 12 are paid staff members earning between $12 and $20 per hour. The remaining six are unpaid interns who work 20 hours per week in exchange for room and board.

Questions about sustainability at Meadowsong depend largely on how one defines the term. Approximately 20% of the food consumed at Meadowsong is grown on-site, while the rest is purchased in bulk. Kelson Gorman, Lost Valley’s garden manager, emphasizes food sovereignty as central to true sustainability: “Ideally, you're providing for the community while also building relationships with surrounding farms. That’s the whole system's picture of what it actually takes to have true sovereignty and resilience.”

Community labor presents another challenge. Most residents work outside jobs and cannot contribute to the maintenance of shared spaces, while others take on tasks and committee roles with little coordination or oversight. As a result, much of the day-to-day work falls on the 18 staff members who keep the community running.

The community survives through a patchwork of resourcefulness and trust: salvaged lumber becomes benches, a fallen tree becomes firewood, and, on one memorable occasion, a roadkill deer was turned into meat, jerky, broth and drum skins.

There is a thin line between collaboration and exhaustion, idealism and the unrelenting demands of shared survival.

Bodhi Sellers, a recent UO graduate completing a three-month administrative internship, spoke candidly about this invisible pressure:

“There’s this common theme here where I feel we are putting the pressure on ourselves. I’ll be working on a project and my hours are up, but I feel like I need to keep going, for the community.”

For many interns, that sense of obligation is both the glue that holds the place together and the weight that makes it hard to breathe. Interns join supervised work parties, typically three hours long and four days a week, filled with tasks like gardening, repairs, controlled burns and communal upkeep. Participants are encouraged to follow their curiosities. But in a place where “free time” often translates to “more work to be done,” balance remains elusive.

Glen Carlberg, the internship coordinator and a two-year resident of Meadowsong, has watched this dynamic play out time and time again:

“Most of the interns have expressed that they don't feel like they have enough time, in any given week, to do all the things they want to do here.”

Carlberg sees the internship as more than labor, but as a social and spiritual experiment that demands humility and adaptability. “There’s a different set of skills needed to successfully integrate into any community of place,” he said. The program’s orientation week, weekly meetings and educational offerings are structured to help interns develop a clearer understanding of themselves, creating a foundation for deeper personal and professional growth. “They can form stronger, more grounded connections with others and with the more-thanhuman world in which we live.”

Even with these supports, the tension between freedom and structure persists. Some struggle to reconcile the dream of intentional living with the reality of uneven effort and emotional strain.

Former resident Erica Dallman captured this contradiction with sharp honesty.

“I participated and worked. And when some people didn't do either, it was frustrating. People would get really excited and get really involved in structures or community meetings, and then they’d get burnt out and stop.”

For all its beauty and intention, life at Meadowsong asks a simple but relentless question: how sustainable can community be when the cost is carried unevenly?

Joining Meadowsong is not as simple as moving in; it’s a gradual process meant to test both compatibility and commitment. Prospective residents go through a provisional interview, followed three months later by another conversation to assess whether they want to stay. A year after that, a final check-in asks a more

personal question: not whether someone met a community standard, but whether they lived up to their own word. As Carlberg explained, the goal is less about judgment and more about honesty: did residents show up in the way they said they would?

To support this culture of accountability, Meadowsong shared a document known as the Community Living Agreements, a living framework for how people coexist. Based on lessons learned from decades of intentional communities before them, the CLAs blend insights from self-help, spiritual and ecological traditions into a code of cooperation.

Carlberg acknowledged that people inevitably fall short of these ideals. “People are messy,” he said. “They’re going to mess up. What matters is whether they’re honest about it, whether they can say, ‘Yes, I broke an agreement, and here’s why.’”

Within community meetings, residents can raise concerns when someone’s actions violate the agreements, not as punishment, but as a chance for reflection and repair.

Conflict resolution at Meadowsong, like in many intentional communities, draws inspiration from past experiments in communal living. It borrowed tools from mediation and self-help traditions, but without the structure or credentials to support them. “It’s difficult because I believe in community structures,” Dallman said. “But no one there had psychology degrees or conflict-resolution training.”

In practice, neighbors often step into the role of mediator simply because they feel intuitively equipped, even when their good intentions accidentally escalate tensions. The process relies less on established methods and more on the community’s collective instinct or, as Dallman put it, “on vibes.”

For all its aspirations of harmony, Meadowsong reveals how difficult intentional living can be. It takes far more than good intentions to sustain a shared vision; it takes communication, accountability and willingness to confront what the community truly demands of its people.

Voices within the broader sustainability and intentional community movement have grown increasingly self-critical, sparking vital conversations about economic inequality, reliance on volunteer labor and accessibility. This introspection is not isolated to individual ecovillages like Medowsong but resonates on a global scale. The Global Ecovillage Network, an international coalition connecting ecovillages worldwide, explicitly acknowledges these systemic challenges.

In its 2023 Annual Report, GEN Europe calls for ongoing self-reflection and evolution in governance and economic models to better address issues of equity and sustainability. The network emphasizes that communities must adapt their structures to become more inclusive, recognizing that idealism alone cannot replace pragmatic reforms.

At its best, Medowsong is envisioned as a space for experimentation, a “window” into new ways of relating to each other and to the Earth, as Gorman described: “But at this moment, it is keeping this alive, to try and see a different way of us all relating to each other, as human beings to each other, and to the earth.”

Carlerg framed Lost Valley as part of a broader societal transition: “From one way of living and relating to each other, into a different way of living and relating to each other.” Still, social challenges emerged in everyday interactions.

For outsiders, Lost Valley might appear as a picturesque refuge from the outside world, a quiet enclave of ecological ideals. For those living there, it is a constant negotiation; a place where potatoes are baked, chickens are herded and conflicts must be navigated with patience, empathy, and, sometimes, blunt honesty. Its successes are measured not just in harvests or workshops, but in the resilience, reflection and learning its members cultivate along the way.

The paradox is clear: the very qualities that make Meadowsong inspiring — its openness, its commitment to shared responsibility and its willingness to experiment — are the same qualities that create tension, conflict and occasional disillusionment. These communities are less about achieving perfection and more about engaging deeply with the process of living deliberately:

“Almost every interaction is based on our individual needs. In one way, shape or form. So, if you're being intentional and transparent about those needs, you're far more likely to co-create some sort of beneficial connection.” Carlberg said.

(FAR LEFT) Bodhi Sellers, a current administrative intern at Lost Valley Education Center who graduated from the University of Oregon in 2025, poses for a photo at the facility in Dexter, Ore., on Nov. 13, 2025. Sellers has been living there for about two months.

( FAR RIGHT) Kelson Gorman, Lost Valley’s garden manager, was an intern twice before gaining fulltime residency at the facility. He poses for a photo in Dexter, Ore., on Nov. 13, 2025. Gorman has been living there since last summer.

(FAR LEFT, ABOVE) Lost Valley Education Center, located in Dexter, Ore., takes a holistic approach to sustainability education, engaging students in ecological, social and personal growth. Since 1989, Lost Valley has offered experiential learning through its community and education programs. The community provides affordable housing and access to land for ecological living, along with opportunities for community development. Inspired by sociocracy, the center seeks to create a nonprofit-driven culture.

(Alyssa Garcia/Emerald)

Food truck owner Michael Rieux secures housing for his family with his cheesesteak business.

By Owen Johnson | Ethos Writer

Michael Rieux flipped a thin-cut ribeye off the burner onto a roll as steam filled the cramped kitchen. Sweat beaded on his brow, collecting on the netting that held back his hair.

He wrapped the order in paper, turning to the counter where a young couple had been waiting outside. They looked unenthused by the look of their food, and he heard them complain to each other about the time it took to make.

Rieux worked alone, making each order in silence, one after another. Fifteen minutes after he served the couple their food, they returned. They loitered by the service door, waiting to get Rieux’s attention. He worried that they had a complaint.

Instead, they began to rave about the quality of his food. Beaming, they assured him it was well worth the wait. Rieux was relieved, but not surprised.

“That happens all the time,” Rieux said, with a smirk on his face.

Rieux and his wife, Veronica, own and operate Cheesy Phil’s. The food truck serves cheesesteaks right next to the University of

Oregon campus, inside the newly opened Annex food cart pod. However this was far from the first location.

The business is their family's primary source of income. Rieux and his family had been homeless before it opened, living in shelters around Eugene. They’d left their hometown of Fresno, Calif., in search of a safer environment for their kids after gang activity in their community became too much for them to bear.

The truck’s exterior is steel, roughly bolted around the frame of the vehicle with a modified vent on top to let out cooking steam. Rust coats the steps leading inside. The licence plate reads “FUD TRK.”

Outside, Veronica sat on a bench, waiting for her husband to return from a break and keeping one eye out for potential customers. She had a wide grin on her face that remained as she spoke. Her curly black hair was tied up in a loose ponytail.

Before they moved to Oregon, she remembered her husband telling her that God was calling him to leave California. He had been in and out of prison all his life, and hoped to break the cycle.

Rieux, 42, has a calm and purposeful energy when he speaks. His teeth have a whiteness usually reserved for toothpaste commercials or Hollywood productions. He had a calm, bemused look on his face as he scanned the park for customers. Today was slow, but orders often came in bursts.

That afternoon, he was wearing two different pairs of sunglasses. Black visors to cover his eyes, and a second pair resting on the brim of his baseball cap. He wore a black t-shirt, the same as his wife’s. There were several tattoos on his arms. An outline of California was traced across his bicep. A star marked Fresno.

After several of his prior attempts towards food business had failed, Rieux took to YouTube in search of inspiration.

One video in particular that piqued his interest was a 2012 recording of a Philadelphia restaurant called Pat’s King of Steaks. They had recorded a crowd of people lined up outside of the restaurant, waiting for a chance to order Pat’s famous cheesesteaks.

“I was like, wow. How the hell is he doing that?” Rieux said.

After seeing the video, he opened a similar food truck in California, where he began to perfect his cheese steak recipe. As he talked about his business, his voice became commanding.

“There’s going to be no other sandwich like mine,” he said. “My signature is in the preparation.”

Rieux described his first year in Oregon after moving here in February 2023 as one of the most difficult periods of his life. He and his family came to Eugene with a housing voucher, but they ran out of money after three months.

As the weather turned cold, Rieux had to do everyanything in his power to get his family to shelter. His criminal record from his time in California made it difficult for him to find a job.

Rieux scoured the city for opportunity, but came up empty-handed. While rain poured down on the streets outside, Rieux found himself stealing from stores around the city. He only took food at first, but soon turned to stealing electronics. They were the smallest objects that he could sell at a good price.

He gave whatever he could to his family. On cold nights, he would pay for his children to stay at motels to protect them from the elements. He tried to avoid stealing enough to draw suspicion.

Rieux soon fell back into the patterns that had led to his arrests in California, numbing himself with drugs and alcohol. Despite the change in his environment, his problems had followed him to Oregon. He considered leaving again, but he knew that he could not outrun his demons.

Remembering this period of his life, he grimaced. He covered part of his face in shame. “I had all of these people that relied on me, that I love,” he said.

It was the first time in Rieux’s life that he had nowhere to go at the end of the day.

Early in the morning, Rieux tows the food truck into the park. On his passenger seat, he keeps a heart-shaped pillow signed by his wife and his cardiologist. When he feels stress, he holds it to his chest to help with the pain.

Rieux doesn’t mention his health issues when he talks to his regulars.

At first, he thought his back pain had been from overexertion. He thought that his shortness of breath was due to smoking or stress. He didn’t want to risk going to the hospital. He feared the medical bill would keep their finances underwater.

Rieux knew that something was wrong. He felt it every time he took a deep breath. He tried to push through it. And for a while, he did.

When the attack came, it was sudden and crippling.

On Aug. 21, 2023, Rieux’s eldest son, Abraham, turned 10. As their family celebrated around him, Rieux collapsed. He had suffered a major heart attack.

He was transported by helicopter to Portland for a surgery to repair his aorta that lasted 12 hours.

“I don’t remember it,” Rieux said. “I just remember waking up from it.”

Following the surgery, Rieux was barely able to move, let alone walk. He took hundreds of tiny steps in physical therapy, one after another. Progress was slow, but he kept at it until he retrained his body well enough to walk again.

Rieux is not usually sentimental. Still, he keeps the pillow nearby. It reminds him to be thankful and motivates him to move forward.

“Some tragedies became our blessings,” Rieux said. “It’s just been wild for us, but God has been really good.”

Rieux knew that he had to change. He knew that the life he lived was not sustainable. In the wake of his brush with death, he decided to commit to his plans of opening a restaurant. The work he did during his recovery process would eventually lead to Cheesy Phil’s.

Veronica became his official caregiver after the surgery. The government funds she received for helping him recover allowed them to find permanent housing, and they begain saving up for a potential location for their business.

Not long after, while

parked outside of a commercial kitchen that didn’t seem to be in use. They pulled off of West 11th Ave. and began to pray. Too nervous to knock on the door, Rieux began to circle the building.

After the fourth lap, he parked beside the truck and prepared to pitch his restaurant in hopes that the owner was willing to sell or lease the vehicle. The truck belonged to Ben Maude, the former owner of Bar Perlieu. Maude had spent the last week online, looking for someone like Rieux to rent to.

“Out of the blue, he knocked on my door,” Maude said. “We started talking, and that was it.”

After their first conversation, Maude was impressed. Once he tried Rieux’s menu, he finalized the lease in early 2025.

“You could tell that he was passionate about what he does. He loves his product,” Maude said. “Not only does he have the experience and the drive, there's also a need there. He needs to succeed at it.”

On July 1, 2025, Rieux’s bank contacted him about an unclaimed account in his name that had been accruing interest for years. They issued him a check for nearly $30,000.

“I’m still having a hard time comprehending it. Until it’s in my hand, I can’t believe it,” Rieux said.

Rieux plans to use the money to reach his eventual goal, a brick- and- mortar restaurant of his own that could support his wife and children.

“The day I opened this door and sold my first sandwich, I was already thinking about where I'm gonna put something that's gonna stay,” Rieux said. “This has just been a stepping stone since I opened the door.”

Rieux believes that his faith provided him the opportunity to make his dream of owning a restaurant come true. Rieux has owned many businesses over the years, but none lasted. He lost money and he lost time, but he never lost hope.

“I have this whole business plan; this whole dream, this whole idea, this whole thing painted in my head,” Rieux said.

He described pristine white floors, silver countertops and employee dress codes. All

of the details were accounted for. A mosaic of choices he would one day make.

Rieux spent countless nights dreaming about this restaurant, at times awake, at times asleep. Cheesy Phil’s has become more than a restaurant to Rieux. It’s his future. A future where his loved ones are safe and comfortable. A future where the tribulations of past years are nothing but a distant memory.

Rieux works long hours day and night in service of this vision. There is no end in sight, but he presses forward. A thousand small steps, one after another, until he can get back on his feet. Then, another thousand before he can finally rest.

“It might be a while before I can take a step back, but… ,” he said, trailing off in thought.

He looked around at the vacant parking lot. There were no other vehicles parked there besides the two he owned. He looked beyond them, right to where the trees met the sky.

“I mean, there's nothing else to do.”

A look at how popular media is spread across dozens of platforms, and a guide on what to keep and what to cut.

By Amelia Fiore Arts & Culture Writer

In 2025, many popular films and television shows are exclusively offered through streaming platforms, with hundreds of competing platforms holding various media hostage behind paywalls. For students, it’s become exponentially harder both to keep up with what’s trending and to follow a budget.

The beginnings of television were much more modest. The first TV, the Baird Televisor, was introduced in the late 1920s, with its only payment being a one-time purchase of the device itself, with no extra fees or exclusive channels. But times changed, and a monthly subscription was introduced to maintain antenna systems. Then, in 1983, HBO was introduced, and the age of add-on channels and exclusive content was born.

Now, there are over 200 streaming platforms worldwide. Netflix, HBO Max, Hulu, Paramount+, AppleTV, Prime Video, Peacock, Tubi and Disney+, just to name a few. It’s a large leap from TV’s humble beginnings, and one has to wonder why content is spread across so many services.

The situation is very complex, considering shifting licensing cycles and companies moving content to control their own ad revenue and viewer data. Luckily, there are resources to lower costs, including bundles and deals available exclusively to students. Students can enjoy HBO Max at $5.49 a month, Hulu at $1.99 a month and 50% off any Paramount+ plan (for the first year). While not a total relief of financial burden, these plans greatly increase accessibility for students, 71% of whom, according to Inside Higher Ed, have experienced financial trouble while in school.

It’s a whirlwind of content, nonetheless. One tactic students on a budget use to navigate excessive choice is narrowing down which genres they value most and which platform(s) have the biggest or best catalogue of them.

Jackie Sandoval, a senior studying advertising and Spanish, subscribes to Net-

flix, Disney+ and Amazon’s Prime Video based on content preference.

“I like different kinds of shows, like reality and animation and romance movies,”

Sandoval said. “I feel like not a lot of platforms have romance movies; Netflix took a whole bunch off, so I have to go through Amazon Prime.”

She also occasionally purchases a platform’s subscription for the duration of its limited series, such as “Love Island” or “Dancing With The Stars.”

While choosing platforms may be based on casual preference for some, other students depend on streaming for their academic success. Izzy Jurien, a senior studying cinema, subscribes to Peacock, AMC+ and Criterion. She also utilizes Kanopy, a free-for-students streaming service that offers classic cinema, documentaries, foreign films and more.

Since Jurien’s coursework requires access to specific films, often niche in nature, Kanopy became a necessary resource before her other subscriptions. But it’s not all-encompassing, and some films were just out of reach.

“In the past, when I didn’t have access to as many streaming services as I do now, I wouldn’t be able to watch a lot of movies that were required for classes, or that I needed for research on certain projects, because they were behind a paywall,” she said.

Jurien believes media is inaccessible nowadays, which drives young people away from casual movie consumption. She said, “I think film is a very, very, very important art medium, and I feel that a lot of people have lost respect for it because of how many bad movies are released in theaters. I hate how spread out films are on different platforms because I wish people had more access to important films.”

The streaming platforms that are actually “worth it” are really just the ones that align with individual taste, finances and cinephile status. Enjoy niche foreign films? Check out Kanopy or the Criterion Channel. Prefer cheesy rom-coms? Stick with Amazon Prime or Hulu. Messy dating shows? Netflix is your best bet.

weekend plans, but what

By Everette Cogswell Arts & Culture Writer

Within the University of Oregon and Eugene community, house shows play a huge role in the music scene. Almost every weekend, you can count on there being a house show hosting local bands and artists in all different kinds of unofficial venues. However, there is a lot that goes on behind the scenes to make house shows possible which often goes unnoticed by attendees.

Junior anthropology major Miriam Reznick and art major Anika Kasten just hosted their second house show, “The Black Pearl,” their first having been at the beginning of the term. Entering the music scene as an unofficial venue was intimidating at first, but their debut show was a smashing success.

“We had kind of an in already because we knew members of pre-existing bands that were down to play at our house,” Reznick said. “So the first one, they kind of started by reaching out to the bands for us so that they knew we were trustworthy as a house.”

For their first show, they wanted to foster a welcoming and fun environment for those attending. Both Reznick and Kasten found that it paid off to be welcoming at the door and to the bands so there was an immediate sense of mutual respect.

The first step to hosting any show is, of course, finding bands and musicians who would like to play. For their first show, they hosted the bands Everything’s Found, Cosplay Jesus and Verb8im. Once that was all set up for Reznick and Kasten, it was time to move on to getting the backyard ready.

People must complete a lot of prep work before they can successfully put on a show. Reznick and Kasten had to send in measurements of the deck/stage that the bands would be performing on, as well as get rid of yard debris and cover up any holes with plywood to eliminate hazards.

“We didn’t need to have any equipment ourselves except for outlets and a house,” Reznick said.“We didn’t even have a stage. Some of them build stages, but since we have a covered porch that fits everything, we just used that.”

The ticket costs are donations that go towards the musicians and those who host the event for their efforts. Once everything was set up, all that was left for the hosts to do was to admit people into the show by accepting donations and stamping hands.

“I thought that being at the front and stamping people’s hands would make me feel left out of the action in the back of the house, but honestly that was my favorite part,” Kasten said. “Just talking to people and getting people excited to hear the music.”

There are a lot of things that go into hosting a successful house show, but the most important thing is having fun with it. For Reznick and Kasten, they felt very supported by their friends who showed up to the event to help out.

“We were just kind of goofing off and so many people we know showed up at once. It was a real visualizer of our place and how many people are there for us,” Reznick said.

Not only did it feel like they were fostering a community of people, but they also got an opportunity to network with the bands and get to know some of the aspiring musicians in the scene.

“It was also nice to talk to the bands because they were very excited to play here because they felt welcomed,” Kasten said. “They were telling us that some other places that they’ve played, they didn’t feel like the people cared.”

House shows are a great way to get connected with the Eugene and UO music scene. Reznick and Kasten plan to host more shows in the future, hoping to continue the fun and welcoming environment they’ve had in their past two shows.

in Mexico

Fan of Valorant or Stardew

Alexander Graham Bell invention

Big fusses

Party

Burns or Barbie’s lover

goer, briefly

you might need Drawing I or Surface, Space and Time for

Seehorn, portrayer of Carol in Pluribus

in

Release oneself from chains

___ Jongg, Chinese tile game 5 Checkups for noxious cars

House flipper

Small study session?

Google Maps, ex.

Long, long time

Sushi bar tuna 16 Big kahuna

Genetic messenger molecule 19 Sound system component

Hit the slopes

David is an opinion columnist for The Daily Emerald and a senior studying data science, economics and philosophy. In his writing, he enjoys finding the abstract relationships between systems and the decisions we make everyday, weaving them into a tangible story readers can easily digest.

Opinion: We once taught students how to navigate the internet. Now we must teach them how to navigate AI, and rethink the purpose of what we teach along the way.

By David Mitrovcan Morgan Opinion Columnist

When the internet became prevalent in education, we had to teach students how to conduct research in a world inundated with misinformation. We didn’t pretend the internet didn’t exist, but started teaching source evaluation, citation and skepticism to build information literacy into the core of what it meant to be educated.

We are now at the same point with AI.

“AI is already implemented in classrooms, whether professors want it or not,” Zain Saeed, a senior computer and data science major, said. Like the internet, AI is here to stay. The choice is not ours on whether we should include it or not; society has already made that choice.

I acknowledge there is real anxiety around that shift.

“I recognize what I do is a trade… I’m a technician in the knowledge economy, so I can be automated in the same way as a technician in any other economy,” Cy Abbott, a doctoral candidate in geography, said.

But I would argue this anxiety is misplaced. The COVID-19 pandemic made it painfully clear that education simply isn’t the same without an in-person learning experience. Likewise, AI will never be able to fully substitute the human work of teaching.

AI has, however, exposed how much of our pedagogy relies on the threat of a poor grade. “The main reason people want to learn was so they don’t fail the class,” Saeed told me. When material is justified only by its appearance on a test, it’s no surprise motivation collapses once AI can do that work. We must also acknowledge that some of what we’ve long taught simply isn’t essential anymore. AI made that clear, too. This moment, therefore, forces us to evaluate the purpose of assignments and make it unmistakably clear to students. Instructors must underscore the value of the work: the thinking, the practice and

Maddox Brewer Knight is an opinion columnist at The Daily Emerald. She is a third-year CHC student pursuing a double major in English and Spanish. As a lifelong Oregonian, Maddox cares deeply about confronting social issues both within UO and in the greater community to make our home region a better environment for all.

Opinion: As AI becomes more socially accepted, professors are discussing how to adapt their curricula to incorporate it. They shouldn’t.

By Maddox Brewer Knight Opinion Columnist

the struggle that makes students better communicators and clearer thinkers. That’s a shift education has dodged for years. AI now makes it unavoidable.

Oddly enough, it also gives us a way to achieve this shift.

“A unique challenge of being (at UO) is the 10-week term. It forces me to cut down course content… and one of the things that can get lost is a detailed explanation of the why,” Keaton Miller, an associate professor of economics, said.

If AI can shoulder the basic concept explanation outside of class, it frees instructors to finally spend time on the parts of learning that matter most — the whys.

If we refuse, AI will keep functioning mainly as a shortcut and our lack of instruction will be a missed learning opportunity. AI’s adoption is already universal — Forbes reports that 90% of college students use AI academically — meaning refusal of AI only results in uneven AI literacy.

Just as we once had to teach students how to read online sources critically, we now have to do the same with AI.

A BBC investigation found that AI misrepresented news events in 45% of its responses. And yet, Saeed told me, “a lot of people take what the AI says as fact.”

Beyond the classroom, the world isn’t pausing for us to figure this out.

“White-collar jobs are being reshaped with AI, and I want my students on the cutting edge,” Miller said.

The internet forced us to teach differently; AI is no different. Without change, education risks collapsing into nothing more than AI prompting. But if we redesign our teaching by clarifying purpose, restructuring assignments and showing students how to think alongside these tools, we can preserve what matters most: the ability to reason in a complicated, ever-changing world.

When I arrived at the UO, generative AI was still a new frontier. There was still novelty in choppy videos of Will Smith eating spaghetti or kaleidoscopic images of people with too many fingers.

This novelty has long worn off. AI has become inescapable. Even in college, where students supposedly learn to think for themselves, we increasingly deputize AI to do the thinking for us.

At first, my professors took a zero-tolerance approach to AI. Now, using AI to brainstorm, outline or summarize is rarely frowned at, and some professors even incorporate AI into their curricula.

Some applaud this change. This is the future, they assert — either adapt or become obsolete.

I disagree. We have no obligation to uncritically embrace technological advancements, and the vast majority of college classes have no reason to tolerate AI. We pay to learn from professors, not AI tools that we could access for free.

I am not alone in my distaste. “I think it’s an insult to academia and education as a whole,” said Larissa Vandehey, a UO history and environmental studies major. “It goes against creative thinking, problem solving, and imagination — all the things the human mind is skilled at. Incorporating AI is an affront to our gift of thinking critically and collaborating with others. We are naturally inclined to do these things, so why substitute them for a faulty program?”

The most glaring problem is the inaccuracy. Chatbots like ChatGPT are infamous for repeating inaccurate and biased information. They often pull facts from unreliable sources like Reddit or Quora, which a discerning student would never cite.

Sometimes, AI will “hallucinate,” information out of the ether — in one case, a lawyer was sanctioned for using ChatGPT to write a case brief after the AI cited a hallucinated court case as precedent. If these AI tools are not suitable for our future careers, why are they accepted in our education?

But AI use doesn’t just leave its mark on our assignments — it leaves its mark on our minds. Recent studies have suggested that when students use AI to offload most of their coursework they show diminished

learning retention and critical thinking.

AI also has a staggering environmental impact — in one case, the residents of the drought-plagued Abilene, Texas are being asked to take fewer showers as the nearby OpenAI datacenter consumes millions of gallons of water. Many students object to classes requiring AI use because they don’t want to contribute to this ecological nightmare.

“Two of the biggest reasons why AI seems to be a net-negative are its poor regulation and the environmental costs,” said Sofía Galván, a UO junior from Texas. “I’m concerned because water resources are being depleted to keep AI chatbots running.”

Furthermore, the men controlling the biggest AI companies are the same men who have shaped our hellish political landscape, including bankrolling Trump’s 2024 campaign. MetaAI and OpenAI have both been accused of unethical business practices — OpenAI whistleblower Suchir Balaji was found dead after exposing the company for copyright infringement, and his parents have insisted that it was a homicide.

AI companies are evil — but they are not a necessary evil. Unlike forking over money to Nestle because we need food to eat or to General Motors because we need cars to drive, we still have the autonomy to withhold our money from Meta and OpenAI.

Thankfully, most of the common uses for generative AI can already be easily achieved with analog methods. Struggling to draft an email? Search for free templates. Need help understanding the key themes of a text? Check SparkNotes or talk to a classmate or GE. Need a visual aid? Use a stock photo or make a free Canva account. Need to revise an essay? Swing by professors’ office hours or one of the many tutoring centers on campus.

Despite the popular insistence that those who resist AI are naive idealists, AI usage is not unavoidable. It would be unfeasible to quit using computers or cell phones, as they have become crucial for everyday tasks. AI is not yet essential, and I hope that students and professors alike will think twice about its ramifications for our community.

WEDNESDAY

Dec. 3, 2025

Oregon vs. Oregon State

With the football season coming to a close, it’s time to remember the format and rules for the postseason.

By Harry Leader Sports Writer

With Week 13 coming to a close and only one game left for the No. 6 Ducks, it's time to start thinking about the College Football Playoffs. This is the second year of the 12-team expanded playoff bracket, and The Daily Emerald is here to give you a recap of all the rules in this new playoff system.

With 12 teams eligible for the playoffs, seeding is more important than ever, with the highest-ranked conference champions no longer getting a first-round bye. Last season, the Ducks got a first-round bye after winning the Big Ten Championship, which secured their spot in the quarterfinal round at the Rose Bowl. Now with the new rule for straight seeding, the top four teams are composed of the top four ranked teams, regardless of conference championships.

One of the reasons for this rule change was that Boise State, which was ranked ninth in the final CFP ranking, got a first-round bye due to winning the Mountain West Conference. The change also gives a team like Notre Dame, an independent, the opportunity to secure a firstround bye in the future.

The highest-ranked teams that didn't win a conference championship are seeded 5-12, with the highest fourranked teams hosting playoff games on home turf. Currently, the No. 6 Oregon Ducks would host the No. 11 Miami Hurricanes at home due to their current ranking.

The rankings are chosen by the College Football Playoff committee, which is composed of former coaches, administrators and media experts who decide the rankings each week. The rankings are selected based on multiple factors, including strength of schedule, head-to-head results and performance.

While only 12 teams make the playoffs, 25 total teams are ranked leading into the day of the draw following conference championships Saturday, Dec. 6.

The final rankings will be released on Dec. 7, and first round games will take place on Dec. 19 and 20 at the home stadiums of the higher seeded teams. Quarterfinals will kick off with the Cotton Bowl Dec. 31, in Arlington Texas and the Orange Bowl, Rose Bowl, and Sugar Bowl will finish the round Jan. 1. After semifinals at the Fiesta Bowl Jan. 8 and Peach Bowl Jan. 9, the 2025 National Championship Game will be hosted at Hard Rock Stadium in Miami Jan. 19.

( LEFT ) A tear runs down the cheek of University of Oregon defensive back Sione Laulea following a 41-21 blowout loss to The Ohio State University Buckeyes in the Rose Bowl in Pasadena, Calif, on Jan. 1, 2025.

(Max Unkrich/Emerald)

Clemente’s superstar freshman year performance proved her immediate dominance in the Big Ten.

By Rachel McConaghie Sports Writer

Alanah Clemente has had a season hard to beat for her first year in college. Since arriving at Oregon, she has been dominant on the court, and the past week proved it, when she led both teams in kills for the ninth time this season. As of the Ducks’ loss to Michigan on Nov. 22, in kills alone, Clemente ranked No. 7 in the Big Ten with 378 and also led in service aces with 47 and service aces per set with 0.47. The Daily Emerald has selected her as its Oregon volleyball athlete of the season.

With two Big Ten Freshman of the Week honors, Clemente is getting national recognition for her skills on the court. Oregon went undefeated in its first three matches, where Clemente made an immediate impact in Oregon's season-opening weekend at the EVEN Hotel Bobcat invite in Bozeman, Mont.

The freshman put down 29 kills while hitting .684 over three matches, helping the Ducks sweep South Dakota, Montana State and Prairie View A&M. Clemente recorded double-digit kills in two matches that added fire off the bench.

“I mean, she’s that good,” Kersten said post-match after Oregon's first home game. “She does that every single day in the gym. The fact that she’s done it four games in a row is not an accident. She’ll be in the gym an hour before practice working on her toss and her serve… that’s who she is.”

Just two weeks ago, Clemente set her career record of 25 kills in Oregon’s five-set win against then No. 9 Purdue.

In that thrilling upset match on the road for the Ducks, Clemente led all players with a match-high 25 kills while hitting .340 and averaging 4.94 points per set against the

home Boilermakers. She added seven digs, three blocks and two aces including a key service winner down the stretch of the fifth set.

“Just coming into this, I didn't really think that I'd be a big impact, because all these girls are just so amazing,” Clemente said in her season preview. “So I wasn't really going into this thinking like, oh, 'I'm going to be this top player.' I was going into this thinking, ‘I just want to get better for future things.’”

That following Wednesday, against then No. 16 USC, Clemente came just one short of tying her career record in kills, with 24 to reach at least 20 for the third time in the last four matches.

“She’s really good, and she’s not even close to where she’s gonna be next year, and I’m so excited for it,” Kersten said post match of Clemente. “Her development and for her to have experience and for her to go through this, what a cool opportunity for her to make this splash in the Big Ten.”

On Saturday, against Michigan, Clemente put up the most kills total between the two teams with 23 on the night, including nine in the first set.

Oregon and Clemente wrapped up their regular season against Maryland on Nov. 28, and likely won’t qualify for the NCAA Tournament in their first year under Kersten. Clemente, though, looks to anchor the Ducks’ rebuild for the future.

( RIGHT ) University of Oregon Ducks Opposite hitter Alanah Clemente (7) prepares to return a spike to the University of Iowa. The University of Oregon Ducks defeated the University of Iowa Hawkeyes 3-1 at Matthew Knight Arena on Oct. 3, 2025. (Paul Leachman/Emerald)