MADAME DE POMPADOUR THE ERA OF

The Festival, The Era of Madame de Pompadour, is under the patronage of Mr. Laurent Bili, Ambassador of France to the United States.

The Era of Madame de Pompadour: text, illustrations, cover

Copyright ©️ 2023 by Opera Lafayette

All rights reserved. No reproduction, copying, distribution or redistribution, in full or in part of the text or images is permitted without written permission from Opera Lafayette.

Best efforts have been made by Opera Lafayette and the contributors to this manuscript to ensure the accuracy of the content disclosed herein, however, Opera Lafayette does not represent this scholarly effort to be wholly error-free.

ISBN: 979-8-88955-174-4

Library of Congress Control Number: 2023903856

Published 2023

Opera Lafayette

921 Pennsylvania Avenue SE

Washington, DC 20002

www.operalafayette.org

Cover: Maurice Quentin de La Tour, Portrait en pied de la marquise de Pompadour. https://commons.wikimedia. org/wiki/File:Maurice_Quentin_de_La_Tour_-_ Marquise_de_Pompadour_-_WGA12359.jpg. Wikimedia Commons.

This publication is made possible by a grant from The National Endowment for the Humanities.

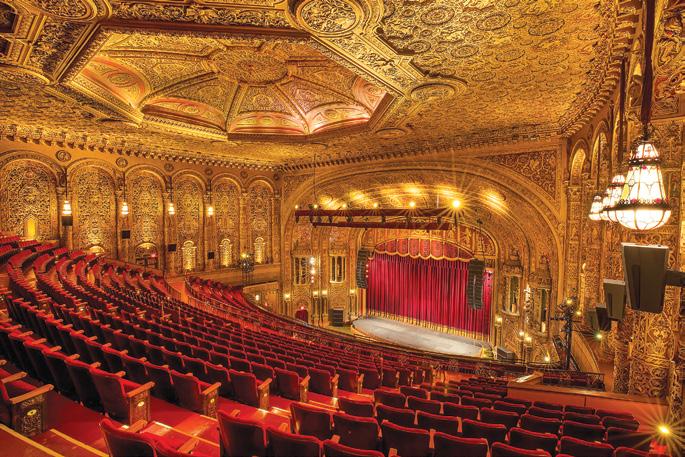

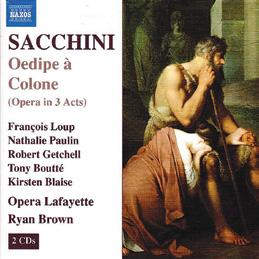

The Era of Madame de Pompadour marks the second of three festivals Opera Lafayette presents exploring various facets of eighteenth-century music in France. Following last year’s Era of Marie-Antoinette, Rediscovered and preceding next season’s Era of Madame de Maintenon, The Era of Madame de Pompadour sits in the middle of the century and is usually associated with both the rococo style and the intellectual battles over the merits of French and Italian music. Digging a little deeper, we find that the rococo and the French/Italian-inspired querelle des bouffons were also battlegrounds where deeply ingrained socio-political outlooks clashed and resulted in new forms of expression and access. As Callum Blackmore’s essay makes clear, at the center of this changing social and artistic landscape was the remarkable Jeanne-Antoinette Poisson, a bourgeois woman who became Louis XV’s maîtresse-en-titre and confidante, Madame de Pompadour.

In the Salons of Versailles, a program created by Opera Lafayette Artistic Associate and concertmaster Jacob Ashworth and featuring soprano Emmanuelle de Negri, demonstrates the variety of music championed in the private spaces at court in the salons of Madame de Pompadour and Dauphine Marie-Josèphe de Saxe. Callum Blackmore describes how these salons represented different tastes and factions at Versailles, coexisting in a delicate balance. He argues that Madame de Pompadour, though a lightning rod for criticism, was a force for progressive eighteenth-century taste as well as artistic and social change.

Pergolesi! is a program that highlights the vitality of Italian music in the era of Madame de Pompadour and the contrast of secular and religious music. Julia Doe’s program note explores how the French adopted the more accessible Italian style as their own, including the French version of Pergolesi’s La serva padrona (La servante maîtresse), and incorporated the style into their own opéras comiques, in sharp contrast to the conservative tragédies lyriques thought to represent the French monarchy and its traditional glory. Director Nick Olcott’s rhymed English translation of the dialogue brings the immediacy of Pergolesi’s comedy to the fore, as it might have done for the French public when translated into the vernacular in the eighteenth century. Very differently, the popularity

of Pergolesi’s Stabat mater reminds us that religious devotion continued to have a hold on the eighteenth-century soul and society. The program is conducted by, and under the guest musical direction of, Patrick Dupré Quigley.

The premieres of two one-act opéras-ballets by de La Garde and Rameau are a major event for Opera Lafayette. The premiere of Rameau’s Io is historic and the modern rediscovery and premiere of de La Garde’s Léandre et Héro a rare opportunity to witness a beautiful and significant work which Madame de Pompadour herself performed. The plot of de La Garde’s work offers a metaphor for the relation of Pompadour to Louis XV, played out through spectacle. An essay by Mathias Auclair, head of music at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, describes its importance and how Opera Lafayette assisted the BnF in acquiring the manuscript.

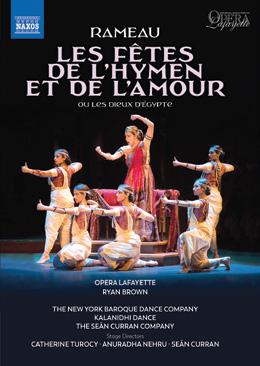

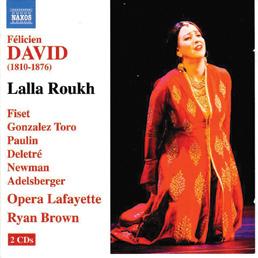

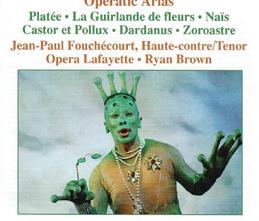

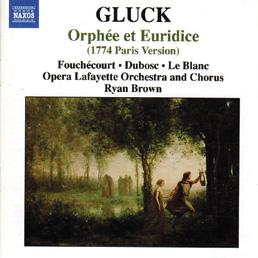

Rameau’s Io, left unfinished in the composer’s lifetime, has been completed with music from Platée under the direction of Sylvie Bouissou, editor of the Rameau Opera Omnia, who describes in her essay how she came to understand Io as the precursor to the composer’s better known comédie ballet. The satirical nature of this opera and Opera Lafayette’s viewing of Machine Dazzle’s recent exhibit at the Museum of Art and Design, “Queer Maximalism,” inspired us to ask this major American artist to costume our premiere. Moreover, as Machine Dazzle’s work struck Opera Lafayette as an example of the modern rococo, we commissioned an essay by art historians Mark Ledbury and Melissa Hyde comparing eighteenth-century rococo art with the contemporary works it has inspired. Our performances are danced by the New York Baroque Dance Company and the Sean Curran Company, conducted by Avi Stein, and directed by Nick Olcott, with sets created by Caples Jefferson Architects, Adam Thompson, scenic project designer.

It is Opera Lafayette’s hope that this festival dedicated to The Era of Madame de Pompadour not only moves and entertains you but also demonstrates the period’s fascinating fluidity of style and suggests how its art and social implications may resonate today. We thank the many artists, scholars, and patrons who contributed to this effort.

Ryan Brown Artistic Director, Opera Lafayette

For many years after her death, Madame de Pompadour, royal mistress to Louis XV, was remembered as something of a national disgrace (Fig. 1). Historians of the nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries frequently blamed Madame de Pompadour for the political failings of Louis XV’s reign – his mismanagement of the French economy, his disastrous warmongering, and the overall corruption of his court. Madame de Pompadour, these scholars argued, seduced the monarch into a “terrible crisis, political, social, and financial, which only ended in the Revolution.”1 Such negative assessments of Madame de Pompadour’s political influence long tarnished her reputation as a patron of the arts. The artistic activities of the royal mistress were viewed as symptoms or by-products of Louis XV’s financial and moral improprieties. The works that she commissioned and championed, in turn, were assumed to “reflect the spirit of dissipation and immorality” which she allegedly promulgated through her outspoken presence at Versailles.2

More recent accounts of Madame de Pompadour’s influence, however, have increasingly challenged these unflattering appraisals of her artistic projects. Modern historians acknowledge the extraordinary complexities of Madame de Pompadour’s political and artistic experiences. In fact, this much maligned figure left us a rich, complex, occasionally contradictory (but invariably enthralling) artistic legacy – one that shaped the aesthetic landscape of court and capital for decades after her death. This is especially true of the royal mistress’s musical activities: Madame de Pompadour emerged as a quiet radical at a moment when the very foundations of French opera were in flux. From her glamorous private theater in the halls of Versailles, to her involvement in the Parisian “opera wars,” to her pioneering patronage of Rameau, Madame de Pompadour – controversial in her own time and today – came to transform musical life in eighteenth-century France.

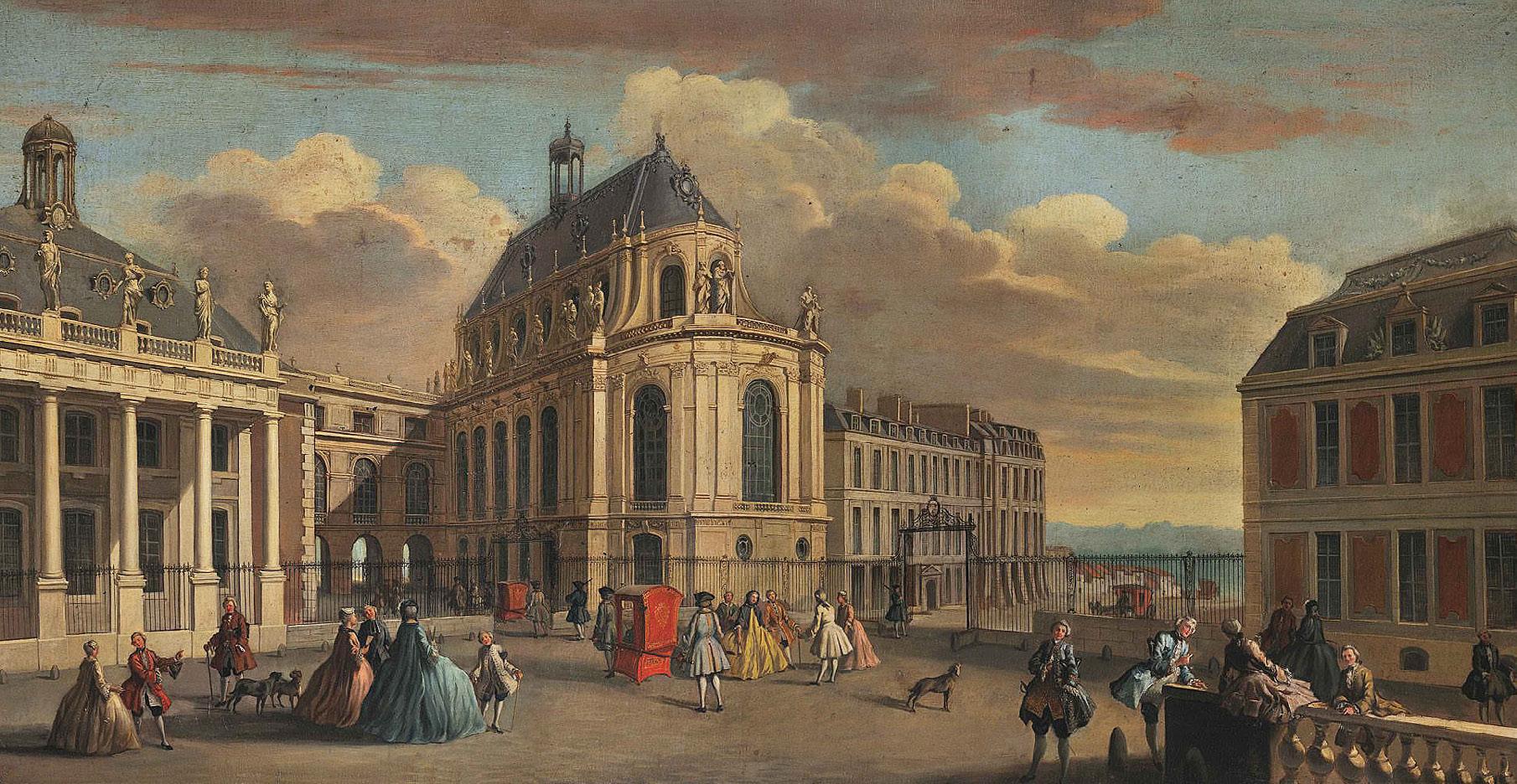

Madame de Pompadour was born Jeanne-Antoinette Poisson, into a wealthy, upwardly mobile bourgeois class. (Her family and their friends consisted largely of financiers, bankers, and bureaucrats.) The young Madame Poisson, however, spent much of her early life being groomed for a position in high society. Her legal guardian, the tax farmer Charles François Paul Le Normant de Tournehem (Fig. 2), ensured that she received an education worthy of any aristocrat, including extensive instruction in voice, keyboard, and guitar. Madame Poisson’s top-notch musical upbringing not only endowed the budding socialite with a lifelong passion for the art form, but also provided her with a crucial cultural tool. Throughout her Parisian adolescence, she had the opportunity to observe the great salonnières of her day. She saw how these talented women wielded their musical abilities to entertain, network, and enhance their social and intellectual profiles. Indeed, when Jeanne-Antoinette Poisson married the financier, Charles Guillaume Le Normant d’Étiolles, she set up a private theater – a so-called théâtre de société – “as beautiful as the Paris Opéra” in the couple’s luxurious home. There, she further honed her musical talents, singing “with complete gaiety and all possible taste,” and performing small operatic entertainments with and for her esteemed guests.3 It was in this musical salon that the young mondaine – now known as Madame d’Étiolles – met the numerous Enlightenment luminaries that she would later patronize, including Montesquieu, Crébillon, and (her personal favorite) Voltaire. Madame de Pompadour’s experience in the Parisian salons would prove critical during her time at Versailles (Fig. 3).

When Madame de Pompadour was appointed Louis XV’s maîtresse-en-titre in 1745, she found herself at a distinct disadvantage. The official mistresses of Louis XIV had all been of noble birth; Madame de Pompadour’s bourgeois background, by contrast, elicited intense skepticism among the cut-throat and hierarchically minded courtly

aristocracy. Worse still, she was connected – by birth, by adoption, and by marriage –to some of the most despised bourgeois financiers in the kingdom. And so, from the moment Madame de Pompadour arrived at court, powerful members of the nobility began plotting her demise. Humiliating rumors swirled around her: that she was diseased, financially corrupt, and prone to sexual perversion. As part of this smear campaign, noblemen infamously wrote derogatory songs to discredit her. Known as “poissonades” (after the royal mistress’s unfortunate maiden name), these libellous works branded the royal mistress as a “grisette,” a “leech,” a “stupid filly,” and a “menial harlot.”4

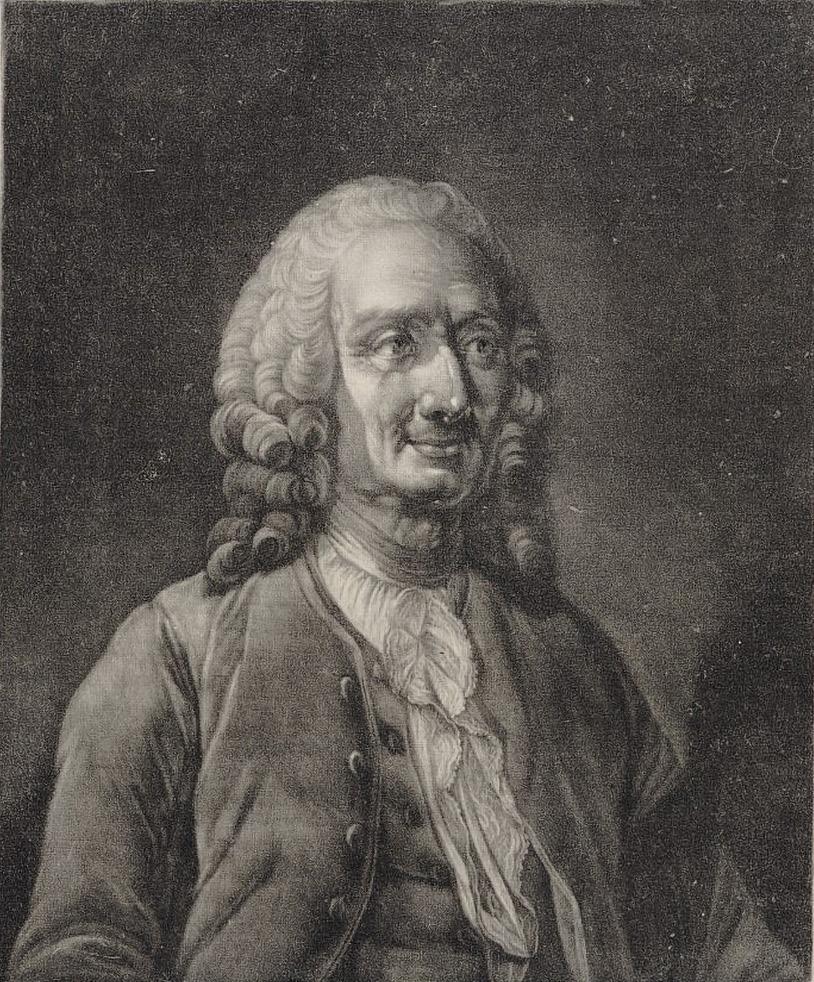

The precarity of Madame de Pompadour’s position derived not merely from courtly intrigue but from the very nature of her role: as maîtresse-entire her entire existence depended on retaining the favor of Louis XV. The king could be a tricky customer. Easily bored and difficult to please, Louis XV was notorious for his morose, dispassionate manner (Fig. 4)

He resented his monarchical duties, preferring instead the rugged solitude of the hunt or the intimacy of the boudoir. Madame de Pompadour did her best to please this lugubrious ruler, but she found her duties as maîtresse-en-tire extraordinarily taxing. Bouts of whooping cough and tuberculosis had left her chronically disabled, and it became increasingly difficult to satisfy the king’s insatiable libido. She began to fear that the king would leave her for a younger, more virile woman, ejecting her from her courtly charge in the process. In letters to friends, she complained constantly of exhaustion, anxiety, and inadequacy. “It was a mistake coming to court,” she wrote in 1747, just two years after arriving at Versailles. By 1749 her assessment was even more dire: “The life I lead is terrible.”5 Thoroughly burnt out and fearing her days at Versailles were numbered, Madame de Pompadour hatched a plan to secure a long-term position. She hoped to forge a platonic relationship with the king, becoming indispensable as a confidante, advisor, entertainer, and administrator. As the royal mistress herself described: I saw that the king’s great illness was the boredom which continually stalked him, and that consequently the surest means of fixing his heart would be that which would make him best pass the time. […] Since I arrived at court, the king was heard saying several times: “How time flies!”6

Madame de Pompadour’s approach, in sum, was to keep the king occupied, making herself valuable by staving off the tedium of royal life. The royal mistress’s rise to power and prominence was an unsteady one. Ultimately, however, her musical education gave her the tools she needed to succeed at court and to win over the terminally bored monarch.

1747 marked a watershed moment for Madame de Pompadour: just two years after arriving at Versailles, she took a major step in cementing her relationship with the king and her position at court. As she transitioned from mistress to entertainer, Madame de Pompadour turned to the same strategies that had worked so well in her husband’s Parisian salon. Namely, she set up a private theater in the king’s personal apartments in Versailles – the Théâtre des Petits Cabinets – where she presented operatic entertainments for the king and a small coterie of friends and nobles. The Théâtre des Petits Cabinets generally performed on winter evenings after the king had been hunting, with the entertainment followed by feasting and drinking. Between 1747 and 1753, this enterprise succeeded (according to one courtier) in “shaking the king’s shyness” and “forming his good taste for pleasure and for le monde,” such that the once morose monarch became “very amiable” and “perfectly intelligent.”7

The Théâtre des Petits Cabinets was a hybrid troupe. The singers were not professional performers, but aristocratic amateurs – often granted leading roles in exchange for political favor. The dancers and orchestra, for their part, comprised a mix of talented courtiers and artists “borrowed” from the public theaters of the French capital. From the Paris Opéra, Madame de Pompadour engaged François Rebel and François Francoeur. These long-standing entrepreneurs of the Parisian stage were employed as ad-hoc music directors for the Théâtre des Petits Cabinets, playing violin in the orchestra as well as writing operas for the troupe. Pierre Jélyotte, the Opéra’s superstar haute-contre, was similarly called to action, serving as the royal mistress’s singing teacher, playing cello in the orchestra, and composing new works. From the Comédie-Italienne, Madame de Pompadour hired the choreographer Jean-Baptiste-François Dehesse and the librettist Charles-Simon Favart, who collaborated on several pantomimes for the private theater. But it was Madame de Pompadour herself who wielded ultimate power within the company: the maîtresse-en-titre acted simultaneously as patron, impresario, and leading lady, managing the troupe and taking a leading part in almost every opera it produced. The Théâtre des Petits Cabinets performed a mix of “classic” operas – works by Jean-Baptiste Lully, André Campra, Jean-Joseph Mouret, and André Destouches – and new commissions from some of the most esteemed musicians of the mid-eighteenth century. The company’s production values rivalled those of the Opéra (Fig. 5).

Madame de Pompadour called upon many of her favorite artists, including the royal engraver, Charles-Nicolas Cochin, and her preferred painter, François Boucher, to work on the scenography. Indeed, Madame de Pompadour’s greatest skill seems to have been as a collaborator – in bringing together a talented mix of creative forces to achieve her theatrical visions. Such established figures as Voltaire, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Jean-Philippe

Rameau, and Jean-Joseph Cassanéa de Mondonville found a mouthpiece in the Théâtre des Petits Cabinets. So, too, did up-and-coming talents. The baritone, guitarist, and composer Pierre de La Garde, for instance, was almost a complete unknown when he entered Madame de Pompadour’s orbit in 1748. The royal mistress ultimately commissioned three works from de La Garde for her theater (including his 1750 Léandre et Héro); in addition, she secured him a position as singing teacher to the king’s daughters – a busy and prestigious post within the royal household.8

At the Théâtre des Petits Cabinets, Madame de Pompadour formulated an operatic aesthetic that was perfectly tailored to entertaining Louis XV and his retinue (Fig. 6). Indeed, a ticket to these spectacles was soon one of the most coveted invitations at Versailles. The duc de Luynes, for instance, recalled a scramble among the noblesse

to obtain entrance to these private soirées: “The maréchal de Noailles had insisted on being present at the little show; he was refused; the prince de Conti was also refused; the comte de Noailles had requested the same grace with extreme force without obtaining it, […] he had to go to Paris to try to calm his pain.”9 The aesthetic of the Théâtre des Petits Cabinets was also, notably, one that portrayed the royal mistress in a uniformly flattering light, showcasing her vocal talents while optimistically allegorizing aspects of her relationship with the monarch. De La Garde’s Léandre et Héro serves as an apt example. The opera follows the star-crossed lovers Héro (originated by Madame de Pompadour herself) and Léandre, whose marriage has been forbidden by their parents. After a series of brutal tribulations (including a violent tempest, a terrible maritime accident, and Héro’s attempted suicide), the god Neptune brings the young sweethearts together, giving his blessing to their union. It is easy to see why the story of an off-limits relationship, legitimized through divine intervention, would appeal to the royal mistress. By commissioning and performing Léandre et Héro, Madame de Pompadour implied that her bond with the king – though derided by hostile courtiers – was ultimately consecrated by God. The opera’s final scene features a chorus of sea gods celebrating Madame de Pompadour’s Héro. They sing: “Triumph, happy lovers! Receive, from your ardor, the just recompense to crown your faithfulness!” – in effect, a hymn of exalted praise for the royal mistress and her machinations at court.

If de La Garde’s opera provided theatrical justification for Madame de Pompadour’s presence at Versailles, it also highlighted her artistic abilities. The work provides ample opportunity for diegetic, solo singing, centering the royal mistress both musically and dramatically. Madame de Pompadour’s star turn comes in the opera’s second scene: a dejected Héro describes her suffering to an onlooking bird, “voiced” by a flute in the orchestra. (Madame de Pompadour kept a flock of pigeons at Versailles, which she proudly showed to other nobles: she would likely have appreciated this avian theme.) This ornithological duet was a bespoke product; in other words, it was explicitly matched to the talents of an amateur soprano like the royal mistress, showing off the beauty of her voice without leading to over-exertion. The aria features a relatively simple, stepwise tune over a supportive orchestral accompaniment, with the highly ornamental flute ritornello providing a sense of melodic interest. This unpretentious number is typical of much of the music composed for the Théâtre des Petits Cabinets; it stands in contrast to the grandly declamatory dramatic style adopted by earlier generations of French court composers and would soon come to influence music heard beyond the confines of Versailles.

Madame de Pompadour’s private musical agenda would exert a decisive impact on public musical aesthetics in eighteenth-century France. One important component of this chain of influence was the royal mistress’s relationship with Jean-Philippe Rameau (Fig. 7)

Madame de Pompadour likely knew the composer from her young adulthood in Parisian high society. During his rise to operatic fame, Rameau found patronage in the salons of the tax farmer Alexandre Le Riche de La Pouplinière, whose wife was a long-time rival of Madame de Pompadour and for whom, Sylvie Bouissou suggests, the composer wrote his long-lost opera, Io . Rameau experienced his most successful years during Madame de Pompadour’s first decade at court, emerging as one of the royal mistress’s greatest musical assets. Discussing the endless task of cheering up the king, she remarked that “Rameau aided me greatly in my designs. The king had a taste for gay airs, and this musician excelled in this genre.”10

At Madame de Pompadour’s request, the Opéra in Paris soon commissioned a series of works from the composer which reflected her own aesthetic goals – most of which were first presented before the king, either at Versailles or at Fontainebleau. Madame de Pompadour held a strong influence at the Opéra because she employed so many of its musicians on a part-time basis at her private theater (including, as we have noted, its primo uomo, Jélyotte, and its two directors, Rebel and Francoeur). The marquis d’Argenson, who hated Rameau and Madame de Pompadour in equal measure, was only slightly exaggerating the royal mistress’s sway when he declared that: “The Marquise de Pompadour, who is in charge of the entertainment, has just decided that we will only have Rameau’s music at the Opéra for the next two years, notwithstanding the public’s discontent with this. […] Goodbye to good taste and to good French music!”11

Madame de Pompadour would also play an important role in the famed querelle des bouffons (or “war of the comic actors”) in the early 1750s, a Parisian pamphlet war centered on the relative merits of French and Italian opera. This heated debate transformed the musical and intellectual landscape of Enlightenment Paris, helping to popularize the so-called “galant” style in France and bringing the writings of Rameau, Rousseau, and the Encyclopédistes into the public spotlight. During the querelle, the royal mistress emerged as an outspoken but flexible supporter of the traditional French camp. She frequently pronounced against Italian-style music (“When the Italians […] produce harmonious effects, they lose their footing, and they produce nothing but noise”),12 and she praised Mondonville and Rameau as bastions of the national aesthetic. And yet, for all that she loved the music of Rameau, Madame de Pompadour resented his outright dismissal of Italian composers. (She noted with regret that “even the most beautiful aria by Pergolesi […] makes him grimace with impatience.”)13 Indeed, as the royal mistress was publicly partisan toward the conservative (i.e., harmonically and structurally complex) French sound, her own private patronage had foreshadowed the innovations of the “natural” and tuneful Italian school. The royal mistress gave the premiere of the full version of Rousseau’s Italian-inspired Le devin du village with her troupe in 1753. The directness of melodic expression in such “modern,” Italianate repertoire may even have been associated with the limitations of Madame de Pompadour’s voice. Put another way, the accommodations made for the royal mistress’s amateur capabilities and bouts of chronic illness had led to a simplification of style at the Théâtre des Petits Cabinets; this eminently “singable” aesthetic then found resonance in the imported, bouffons repertoire that soon took the rest of France by storm.

Madame de Pompadour’s musical projects tapered off toward the end of her life. Louis XV, cash-strapped after the War of Austrian Succession, pulled much of the funding from the Théâtre des Petits Cabinets in the early 1750s. Thereafter, Madame de Pompadour moved her troupe to her private chateau at Bellevue, restricting its audience and performance schedule. The death of her daughter, Alexandrine, in 1754 marked the definitive conclusion of Madame de Pompadour’s public musical activities. From this point on, the royal mistress became increasingly religious, and she found solace at her countryside retreats, where she could meditate, take in the fresh air, and entertain Louis XV in rustic tranquility. After her 1764 death, though, Madame de Pompadour’s theatrical legacy lived on. As we have traced, she had championed a new, more melodious style of high Baroque music that prefigured the so-called “Classical” style, leaving an indelible mark on the history of musical aesthetics. Madame de Pompadour had served as patron to some of the most important musical and literary figures of her time: Rameau, Mondonville, and even Voltaire would not have had such illustrious operatic careers without the maîtresse-en-titre’s support. Perhaps most importantly, Madame de

Pompadour’s reign represented a flashpoint in the history of French musical patronage. The Théâtre des Petits Cabinets signaled a move towards bourgeois musical patronage – and particularly bourgeois women’s patronage – that presaged the salon culture of the Industrial Revolution, where the wives of industrialists and bankers drove new forms of musical innovation. For although Madame de Pompadour spent much of her life in royal chateaux, her radicalism derived from the immense cultural power that she accrued as a bourgeois woman within a system that was actively hostile towards her. Madame de Pompadour wielded a bourgeois musical education, paid for by a burgeoning finance industry, into unprecedented musical influence, transforming the French operatic landscape for generations to come.

1. Jean Delaire, “Romances of the Throne: Madame de Pompadour,” Womanhood: The Magazine of Woman’s Progress and Interests, Political, Legal, Social, and Intellectual, and of Health and Beauty Culture 8, no. 46 (September 1902): 238.

2. “Art under La Pompadour,” The Gentlewoman and Modern Life 47, no. 1212 (September 27, 1913): 9.

3. Letter from Madame du Deffant to Président Hénault, quoted in Edmond de Goncourt and Jules de Goncourt, Madame de Pompadour (Paris: Charpentier, 1878), 12. (All English translations of quotes are by the author unless otherwise specified.)

4. Louis François Armand du Plessis, duc de Richelieu, Mémoires du Maréchal duc de Richelieu, vol. 8 (Paris: Buisson, 1793), 163; “Poissonade” quoted in David Mynders Smythe, Madame de Pompadour: Mistress of France (New York: W. Funk, 1953), 194; “Poissonade” quoted in Robert Darnton, Poetry and the Police: Communication Networks in Eighteenth-Century Paris (Harvard University Press, 2012), 186; “Poissonade” in Jean-Frédéric Phélypeaux Maurepas and Pierre Clairambault, Recueil Clairambault-Maurepas: chansonnier historique du XVIIIe siècle, vol. 7 (Paris: Emile Raunié, 1884), 136.

5. Letter from Madame de Pompadour to the comtesse de Noailles in François Barbé-Marbois, ed., Lettres de Madame la marquise de Pompadour: depuis 1746 jusqu’à 1752, inclusivement, vol. 1 (Troyes: Cahiers Bleus, 1985), 39; Letter from Madame de Pompadour to the comtesse de Lutzelbourg in Cécile Berly, ed., Lettres de Madame de Pompadour (Paris: Place des éditeurs, 2014), 132.

6. Jeanne-Antoinette Poisson, marquise de Pompadour, Mémoires de madame la marquise de Pompadour, vol. 1 (Liège, 1766), 326–27.

7. Emmanuel, duc de Croÿ, Journal inédit du duc de Croÿ, 1718–1784 (Paris: E. Flammarion, 1906), 91.

8. Pierre Laujon, “Spectacles des Petits Cabinets de Louis XV,” in Oeuvres choisies de Pierre Laujon, vol. 1 (Paris: L. Collin, 1811), 71–90.

9. Charles Philippe d’Albert, duc de Luynes, Mémoires du duc de Luynes sur la cour de Louis XV (1735–1758), ed. Eudoxe Soulié and L. Dussieux, vol. 8 (Paris: Firmin, 1860), 87.

10. Jeanne-Antoinette Poisson, marquise de Pompadour, Mémoires de madame la marquise de Pompadour, vol. 2 (Liège, 1766), 104.

11. René-Louis de Voyer Argenson, Journal et mémoires du marquis d’Argenson, 5: 344.

12. Jeanne-Antoinette Poisson, marquise de Pompadour, Mémoires de madame la marquise de Pompadour, vol. 1 (Paris: Mame et Delaunay-Vallee, 1830), 413.

13. Ibid., 412.

Libretto by Pierre Laujon

Intermission Io (c. 1745) Jean-Philippe Rameau

Cochin, Décoration des la salle de spectacle Versailles 1745, colorized. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cochin_D%C3%A9coration_des_la_ salle_de_spectacle_Versailles_1745_colorized.jpg. Wikimedia Commons.

Opéra-ballet: de La Garde’s Léandre et Héro & Rameau’s Io

Avi Stein, Musical Direction, Conductor, & Harpsichord

Nick Olcott, Stage Direction & Title Translation

Seán Curran, Choreography, Léandre et Héro & Io

Catherine Turocy, Choreography, Léandre et Héro

Caples Jefferson Architects, Scenic Design

Adam Thompson, Scenic Project Design

Machine Dazzle, Costume Design, Io

Jules Peiperl, Assistant Costume Design, Io

Christopher Brusberg, Lighting Design

Serafim Smigelskiy, Continuo Cello

Léandre et Héro costumes courtesy of The New York Baroque Dance Company, designed by Marie Anne Chiment

Jean-Philippe Rameau Io Critical edition by Thomas Soury, edited for the Rameau Opera Omnia under the direction of Sylvie Bouissou with music from the original version of Platée. Used by arrangement with European American Music Distributors Company, agent for Société Jean-Philippe Rameau/Baerenreiter Verlag.

Léandre et Hero edition prepared by Ryan Brown, Jonathan Woody, Avi Stein, with assistance from Rebecca Harris-Warrick, for Opera Lafayette

Overture from Clérambault’s Léandre et Héro and de La Garde’s La Toilette de Venus

Sylvie Bouissou & Mathias Auclair, Pre-Concert Lecture

Opera Lafayette

Artists (Léandre et Héro)

Léandre Maxime Melnik

Héro Emmanuelle de Negri

Neptune Douglas Williams

Water Spirits Seán Curran Company

Inhabitants of Sestos, Tritons New York Baroque Dance Company

Inhabitants of Sestos, Sailors, Divinités de la Mer Opera Lafayette Chorus

Artists (Io)

Mercure Patrick Kilbride

Jupiter Douglas Williams

Io Emmanuelle de Negri

Apollon Maxime Melnik

La Folie Gwendoline Blondeel

Storm, Grâces, Plaisirs et Jeux Seán Curran Company

Grâces, Plaisirs et Jeux Opera Lafayette Chorus

Production Staff

Rachel Dane Stage Manager

Sarah Greenberg Assistant Stage Manager

Nancy Jo Snider Orchestra Personnel Manager

Jonathan Woody Artistic Associate, Chorus Contractor

Leslie Nero Music Librarian

Todd Mion Technical Direction

Andrew Sauvageau Supertitles

Seán Curran Company

Jack Blackmon - Evan Copeland - Abigail Curran

Gabriella Flanders - Jacoby Pruitt - Ryan Redmond

New York Baroque Dance Company

Carly Fox - Meggi Sweeney Smith - Brynt Beitman

Patrick Pride - Matthew Ting - Jacoby Pruitt

Opéra-ballet: de La Garde’s Léandre et Héro & Rameau’s Io

Dessus: Shabnam Abedi, Aani Bourassa, Olivia Greene, Marie Marquis, Margot Rood†

Haute-Contre: Oliver Mercer†, Richard Pittsinger, Naomi Steele

Taille: David Evans, Derrick Miller, Joseph Regan

Basse: Joseph Baker, Mark Duer, Edmund Milly†, Gilbert Spencer

Violin 1

Jacob Ashworth* Concertmaster

June Huang

Theresa Salomon

Jude Ziliak

Gesa Kordes

Violin 2

Keats Diefenbach*

Natalie Kress

Jeremy Rhizor

C. Anne Loud

Viola

Kyle Miller*

Isaiah Chapman

Cello

Serafim Smigelskiy*

NJ Snider

David Bakamjian

Oliver Weston

Bass

John Stajduhar*

Flute

Charles Brink*

Immanuel Davis

Oboe

Margaret Owens*

Caroline Giassi

Bassoon

Anna Marsh*

Ben Matus

Harpsichord

Avi Stein*

†Cover Artist

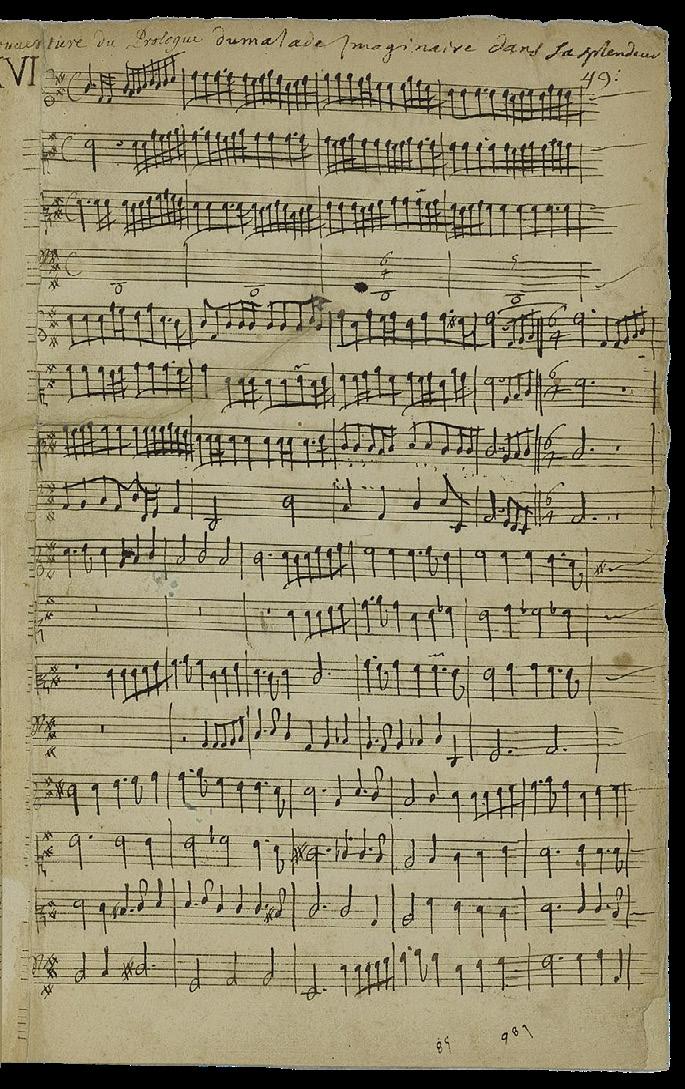

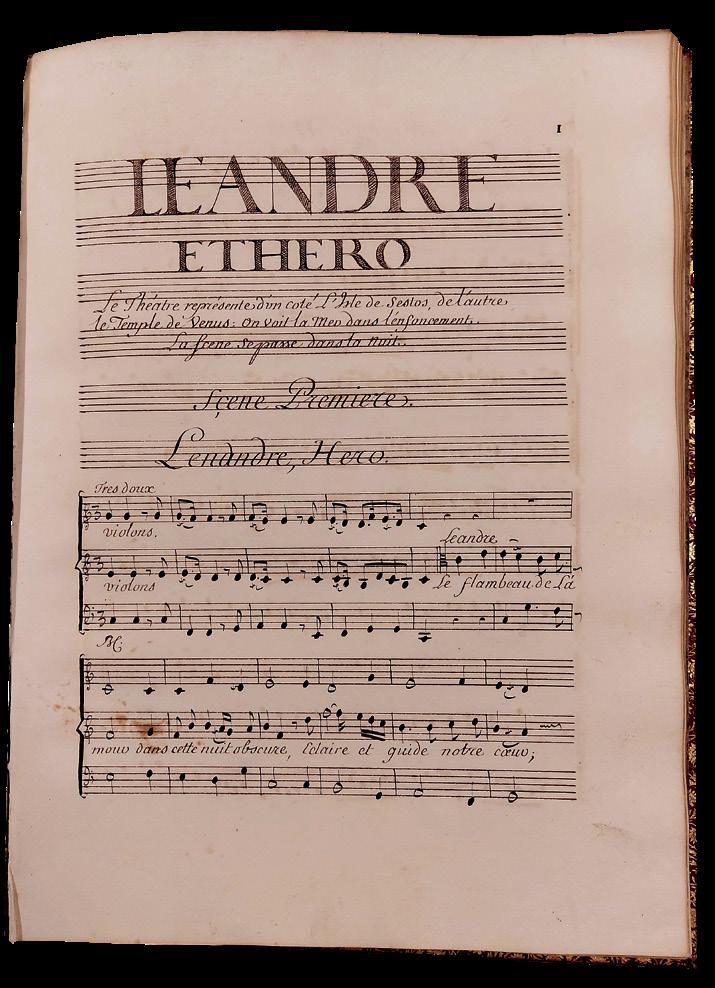

In the spring of 2021, a spectacular, unpublished source documenting the activities of the Théâtre des Petits Cabinets—the theater at Versailles outfitted by King Louis XV for Madame de Pompadour—appeared on the Parisian market. This was a manuscript score containing two opéras-ballets by the librettist Pierre Laujon and the composer Pierre de La Garde: La toilette de Vénus and Léandre et Héro. On 25 February 1750, these works had been presented by the favorite before the king, alongside an earlier collaboration from the same authors, Æglé (repackaged as Les amusements du soir, ou La musique). Together, the grouping formed a trilogy entitled La journée galante. The music of La toilette de Vénus and Léandre et Héro was long believed to be lost; these opéras-ballets were known only from their librettos and from a few rare mentions in the memoirs of French courtiers like the duc de Luynes. Thanks to the support of Opera Lafayette, however, the Bibliothèque nationale de France (National Library of France, hereafter BnF) was able to acquire this remarkable manuscript, which will serve as the basis for the company’s production of Léandre et Héro this spring in Washington, DC, and New York. The occasion offers an opportunity to review the history of the BnF music department, its acquisitions policy, and the performance partnership that has enabled the rediscovery of this important operatic work.

The special attention paid to musical patrimony by the Bibliothèque du Roi, or French royal library—of which the BnF is a direct descendant—dates back to the early eighteenth century. (It should be noted that the “official” Bibliothèque du Roi was distinct from the personal collections of the Bourbon monarch and the Crown princes, which were dispersed at the time of the Revolution.) The royal library acquired the works of the composer and music theorist Sébastien de Brossard (1655–1730) in 1726, and the autograph manuscripts of the composer Marc-Antoine Charpentier (1643–1704)

the following year, underscoring its emerging institutional emphasis on the art form (Fig. 1).

Indeed, from this period onward, the library deliberately cultivated its musical holdings, consisting of both manuscript and printed materials. (Relevant materials from the Middle Ages were placed in the purview of the manuscripts department, where they remain to this day.) Expansion through legal deposit, as well as through acquisitions and gifts, led to the drafting of the first specialized inventory for music in 1753. Compiled by the Abbot Martin, the catalogue contained just over 1,100 entries. A highpoint of the late ancien régime was the bequest of the autograph scores of Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778), donated in 1781 by the executor of the composer and philosophe’s estate. During the French Revolution, these music collections continued to grow, through the confiscation of personal libraries from aristocratic émigrés and members of the royal family, as well as through further donations. One major contribution from the latter category were the holdings of the Concert Spirituel—eighteenth-century Europe’s preeminent institution for public, orchestral concerts—which were ceded to the BnF in 1794 by the last of that organization’s directors. A catalogue drawn up by Paul-Louis Roualle de Boisgelou in 1803 reflected the accelerating development of these musical riches, listing some 4,000 items, in total. A provision for the legal deposit of music printed in France—outlined in legislation dating from 1714 and subsequently reaffirmed in 1810 and 1814—facilitated significant further expansions with the addition of two to four thousand new titles each year.

The beginning of the nineteenth century was marked by a profound change in the status of autograph musical manuscripts. During the pre-revolutionary period, materials representing intermediate stages of the compositional process (drafts, sketches, working scores, tidied-up scores, autograph copies, and the like) were not seen as hugely valuable, and were preserved only in rare cases. The final autograph manuscript might be saved by the author—as, for example, with Marc-Antoine Charpentier—only when the work in question was not ultimately destined for publication. During the Romantic

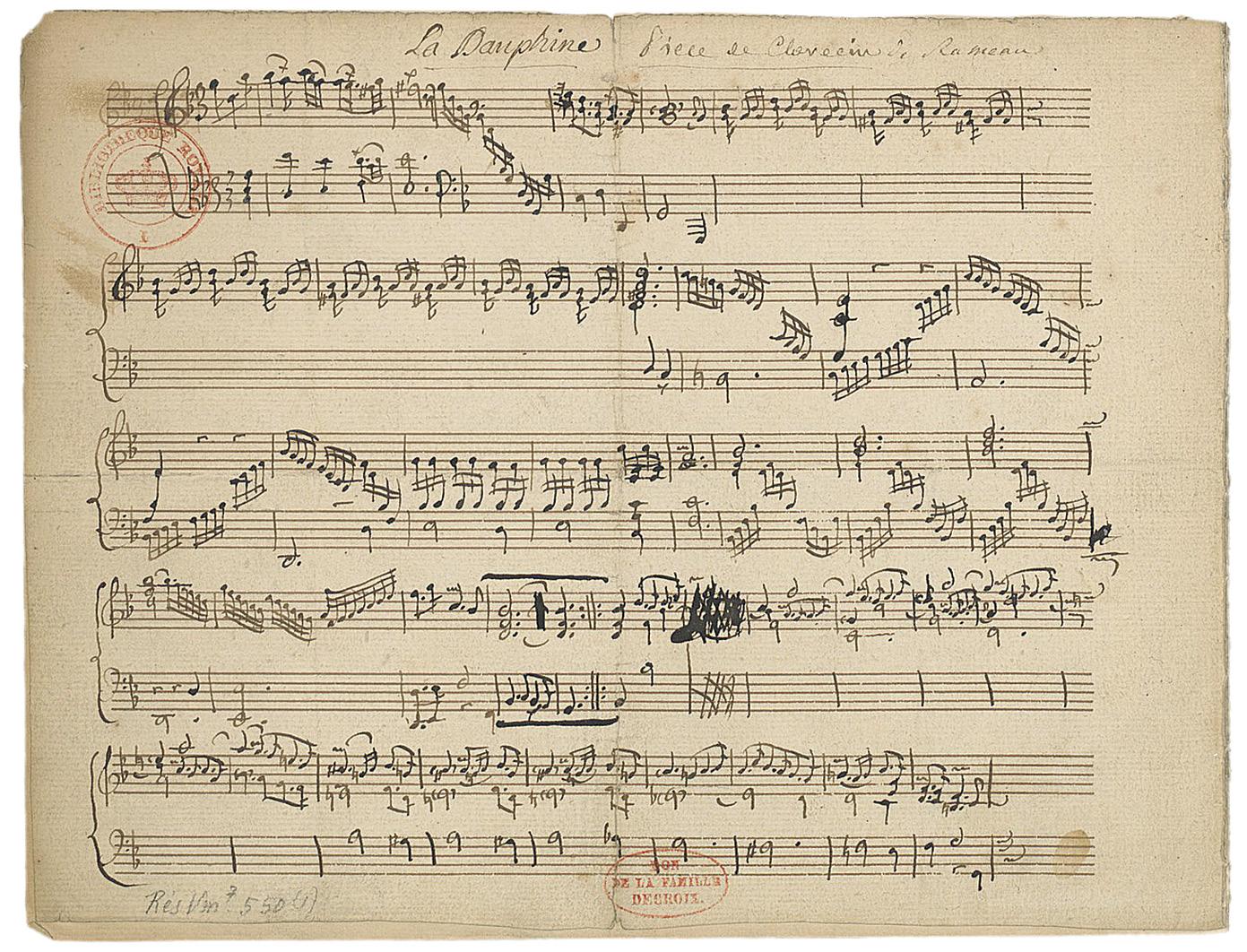

era, however, an emerging appreciation for the composer as creative artist bestowed an increasingly sacred dimension to these “utilitarian” sorts of documents. (The development of critical editions also helped to establish autograph sources as important objects of scholarly study.) In this domain, France moved more slowly than did Prussia, which began to consolidate the scattered manuscripts of the great Germanic masters from the 1820s. In these years, the BnF had not yet articulated or implemented an official policy for the acquisition of autograph musical manuscripts—materials which remained inexpensive before American libraries began to intervene in the European market in the early twentieth century. The BnF nonetheless received some notable donations, including the important autograph manuscripts of Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683–1764), collected by Jacques-Joseph-Marie Decroix (1746–1826) and ceded by his heirs in 1843 (Fig. 2). In 1875, a reorganization of the BnF led to the grouping together of printed music with manuscripts. In 1897, when Leopold Delisle wrote his introduction to the Catalogue général des livres imprimés de la Bibliothèque nationale (General Catalogue of Printed Works in the National Library), the music collections consisted of 30,169 documents, including 1,421 “reserve” (or highly precious) documents; these holdings also included “a series of about 3,800 boxes containing approximately 190,000 sorted but not catalogued items.”

The printed catalogue of early music collections drawn up by Jules Écorcheville does little to soften the severe observations made by musicologists regarding the state of Parisian musical libraries in the immediate post-war period. These figures underscored “the deplorable conditions that affected both elementary and meticulous researches, the dispersion of holdings in locations throughout the city, outdated functional practices, gaps in relevant collections, etc.” They therefore called for a merger between the BnF and two other major libraries in the French capital: those of the Paris Conservatoire and the Paris Opéra. The goal was to construct “a serious inventory and a practical catalogue” of the combined holdings of these three institutions, and to make the best use of the credit granted to them.

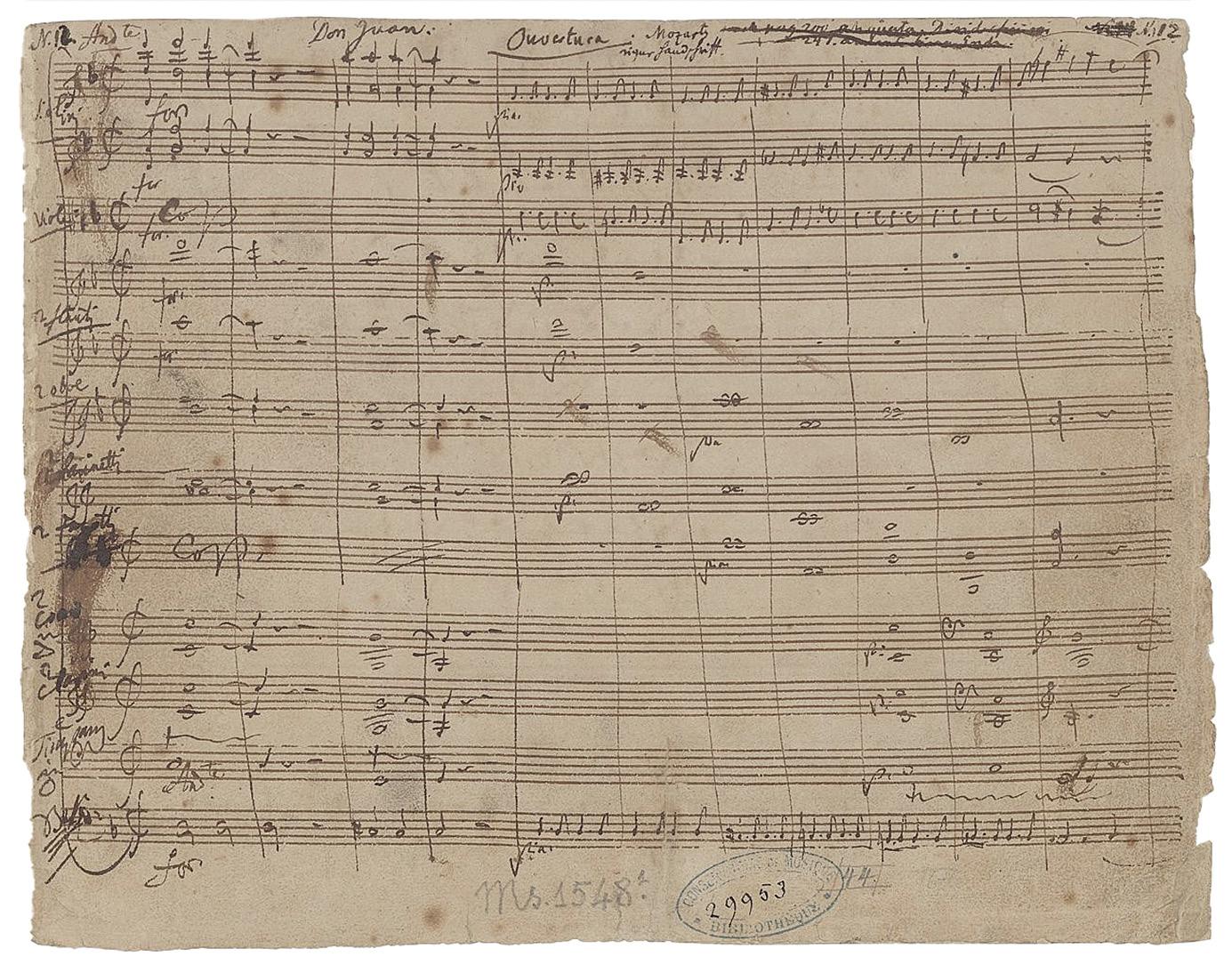

The Paris Conservatoire, founded in 1795, had long held the city’s most important music library, based upon the expanse of its precious collections. The nucleus of these collections was formed from revolutionary-era confiscations, as well as state allocations following the fall of the July Monarchy. These holdings were further developed in the second half of the nineteenth century, first through a bequest of the manuscripts of Hector Berlioz (1803–1869), and then through the initiatives of Jean-Baptiste Weckerlin, the conservatory’s director between 1876 and 1909. Weckerlin spearheaded an acquisitions

policy that paid little heed to expense. His legacy was crowned by the donation of two remarkable treasures: the autograph of Beethoven’s Appassionata sonata, from the pianist René Baillot (1813–1889); and that of Mozart’s Don Giovanni, from the singer Pauline Viardot (1821–1910) (Fig. 3). In 1912, the institution’s preeminence was consolidated with another major acquisition: a bequest from the Opéra’s archivist, Charles Malherbe (1853–1911). This was one of the world’s most significant private collections of musical manuscripts, including 40 manuscripts of Mozart, 90 of Beethoven, 20 of Haydn, 30 of Mendelssohn, 50 of R. Schumann, 50 of Schubert, among many other riches.

Established in 1866, the library of the Paris Opéra is younger than that of the Conservatoire. But it is a multi-functional institution, also operating as an archive and museum. It holds a wide variety of resources related to music: scores, drawings, prints, photographs, architectural plans, correspondence, posters, programs, tickets, paintings, sculptures, objects, etc. These documents derive mainly from the Opéra itself, which entrusted its historical collections to the library in 1866, and continues to transfer materials produced within the framework of its staging activities when they no longer have direct usefulness for performance. The musical manuscripts in the company’s collections were often drawn up by copyists, but some bear annotations from associated composers. Since the beginning of the eighteenth century, composers have also occasionally left their scores to the theater, including full works as well as fragments (particularly adaptations made for the Parisian stage). Representative artists include both Rameau and Gluck (1714–1787).

The Conservatoire and Opéra libraries were initially directed by personalities coming from the world of performance—figures who lacked extensive technical knowledge relating to conservation. These institutions, in other words, were able to amass significant collections without being able to fully organize and maintain them. In response to complaints from music researchers, the French State decided to place these disparate musical resources into a single location, with centralized management: when the music department of the BnF was created in 1942, the holdings of the conservatory and the Opéra were incorporated therein. These consolidated collections now constitute one of the largest music libraries in the entire world.

The BnF Music Department is tasked with collecting, preserving, communicating, and promoting the French musical heritage. In the past eighty years it has developed a wide-ranging acquisitions policy, limited neither by chronology (although concentrated on works beyond the Middle Ages), nor document type (including prints, manuscripts, scores, drawings, engravings, photographs, paintings, sculptures…), nor stylistic barriers: it extends to a large variety of music (art music, film music, jazz, pop music…). It is also not confined to the works of French composers, extending instead to any production linked to France. This is evidenced, for example, by the 1986 acquisition of the sketches and autograph manuscript of Stravinsky’s Le sacre du printemps (The Rite of Spring), created in Paris in 1913.

Since the founding of the BnF Music Department, many autographs from renowned composers have entered its collections, often through donations. BnF holdings include manuscripts from such notable artists as: Emmanuel Chabrier (acquired 1946), César Franck (1946–1947), Ernest Chausson (1947), Erik Satie (1948), Albert Roussel (1954), Charles Koechlin (1967), Arthur Honegger (1973–1976), Gabriel Fauré (1978), Lili and Nadia Boulanger (bequest, 1980), Igor Markevitch (1985), Pierre Boulez (1987), Henri Sauguet (donation, 1991 and acquisition, 2018), Francis Poulenc (donation, 1997), André Caplet (acquisition, 2000), André Jolivet (donation, 2002), Alfred Bruneau (donation, 2013), Olivier Messiaen (2016), Philippe Gaubert (2017), Antoine Duhamel (2017), Léo Ferré (2017), and Charles Gounod (acquisition, 2021). To the extent possible, sets of manuscripts are preferred. Nevertheless, acquisitions are more often made, by chance, from the sales of isolated works: Claude Debussy’s Le martyre de Saint Sébastien in 1961; Maurice Ravel’s Boléro in 1992; the piano-vocal score of Hector Berlioz’s Les Troyens, César Franck’s Variations symphoniques, and Charles Gounod’s Gallia, all in 2016; Pierre Boulez’s Notations in 2017; Henri Dutilleux’s Métaboles and Olivier Messiaen’s L’Ascension in 2018; Jules Massenet’s Marie-Magdelaine in 2022, etc. These acquisitions have taken their place within the substantial corpus already present in the library’s collections.

The BnF is also keenly interested in expanding its holdings of manuscripts from contemporary composers. Thus, as early as 1945, Richard Strauss (1864–1949) donated to the BnF the autograph manuscript of one of his symphonic masterpieces, the Alpine Symphony. In 1951, Messiaen (1908–1992) granted those of such important works as Île de feu 1, Île de feu 2, Mode de valeurs et d’intensités, and Neumes rythmiques. Henri Dutilleux offered that of Timbres, espace, mouvement ou La nuit étoilée in 1984 and Iannis Xenakis that of the Jonchaies, in 1985. In 2005, the manuscript of Pascal Dusapin’s

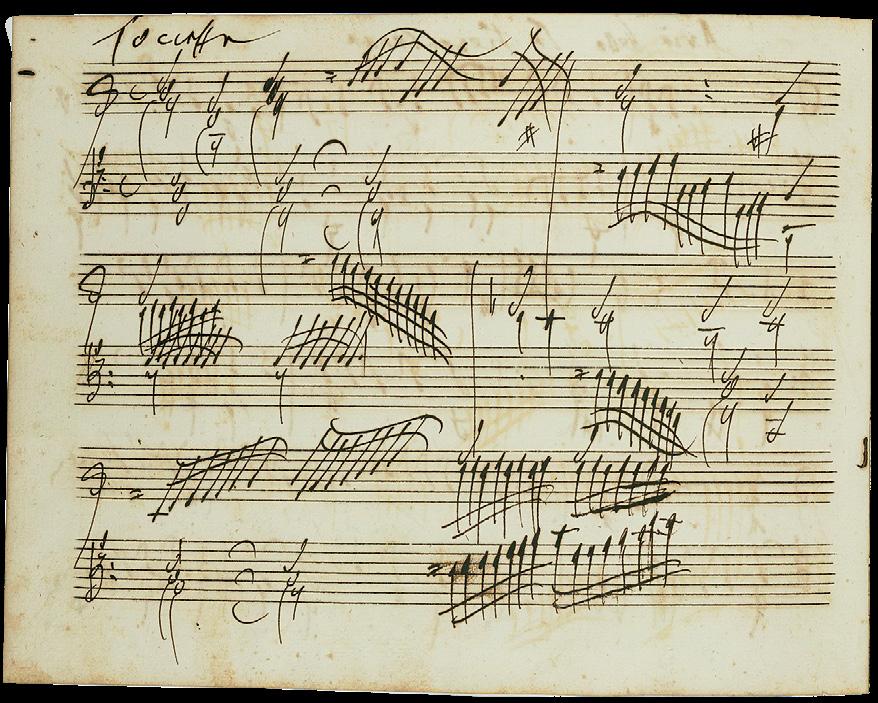

opera, Roméo et Juliette, entered through a donation. In recent years, several composers have shown extreme generosity by donating important proportions of their output, or even the entirety thereof. This group includes: Jorge Arriagada (born in 1943), Michel Decoust (born in 1936), Hugues Dufourt (born in 1943), Bechara El-Khoury (born in 1957), Philippe Fénelon (born in 1952), François-Bernard Mâche (born in 1935), Michèle Reverdy (born in 1943), and Gabriel Yared (born in 1949). Finally, the BnF has taken care to enrich its holdings by consolidating the work of major music collectors. The first acquired collection, from 1978, was that of the musicologist Geneviève Thibault de Chambure, brought in to supplement the library’s national holdings in the domain of early music. These holdings were already very rich, consisting of, among other jewels, the Brossard collection and the Charpentier manuscripts (mentioned above); the Philidor collection (works copied at the request of King Louis XIV under the direction of André Danican Philidor, seized at the Revolution); the holdings of the pre-revolutionary Menus Plaisirs; the collection of the Marquis de La Salle, confiscated at the Revolution; the Borghèse collection, comprised of madrigals from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and acquired around 1892; the Toulouse-Philidor collection, compiled under the direction of André Danican Philidor for one of the sons of Louis XIV, Louis-Alexandre de Bourbon, comte de Toulouse, and acquired partially in 1978. Of final note is the Chambure collection, which entered the BnF via donation, and brings together some 600 scores, including 120 manuscripts. The latter group includes: a manuscript by the chansonnier Nivelle de la Chaussée containing the only poem by François Villon to have been set to music; a notebook that Girolamo Frescobaldi used for compositional sketches from 1607 to 1637 (the oldest autograph manuscript preserved at the BnF) (Fig. 4); as well as precious collections of cantatas and Italian opera arias from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, some richly decorated, and lute and guitar tablatures of French, Italian, and German origin.

The volume containing the orchestral score of La toilette de Vénus and Léandre et Héro was the BnF music department’s most important early-music acquisition in a decade. The last purchase of similar significance was that of Jean-Philippe Rameau’s annotated copy of his Traité de l’harmonie, a foundational work of Enlightenment music theory, in 2012. The unpublished musical manuscript of Laujon and de La Garde, long thought to be lost, reappeared in May 2021: it was advertised in a catalogue announcing the sale of the theatrical collections of the comte Emmanuel d’André, the CEO of a mail order company and a prominent personality in the French world of music and the arts.

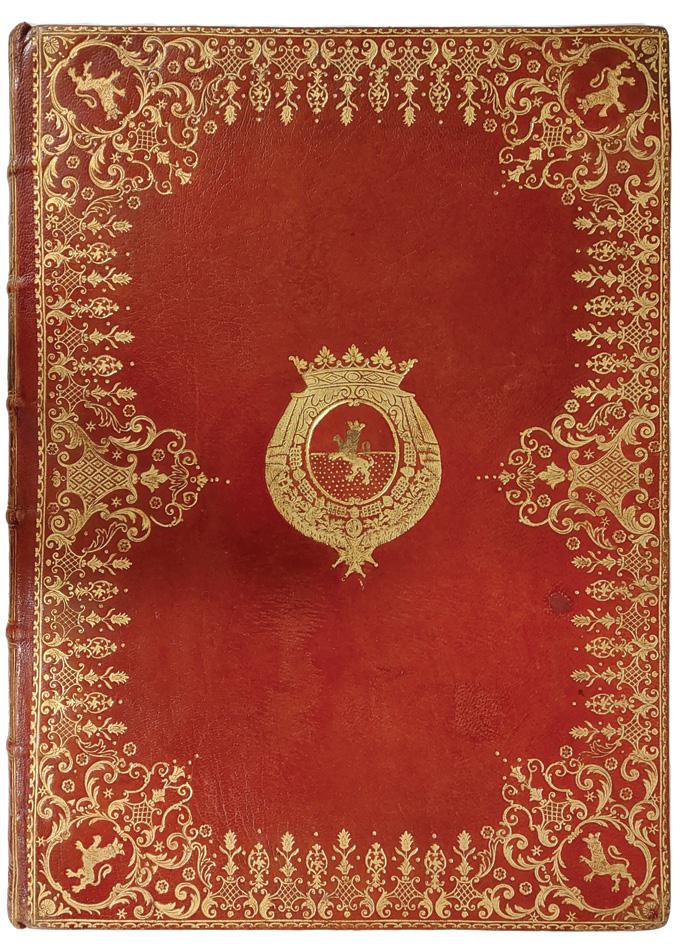

Presented in a magnificent Morocco binding with gilded inlay and attributed to King Louis XV’s bookbinder, AntoineMichel Padeloup, the manuscript originally belonged to Louis-César de La Baume Le Blanc, duc de La Vallière. (La Vallière’s coat of arms can be found on the front of the binding (Fig. 5).) The nobleman was the director of the Théatre des Petits Cabinets. He systematically commissioned copies of the musical works performed on Madame de Pompadour’s stage, as revealed in the catalogue of his personal library, drawn up at the time of his death in 1784. (The manuscript of La toilette de Vénus and Léandre et Héro appears within that inventory, listed as item 3527.) From La Vallière, the document passed to René de Brassac de Béarn (1862–1919), as evidenced by an ex-libris emblazoned inside the volume, and from a subsequent catalogue of sale. In 1933 the manuscript was purchased by the English book collector John Roland Abbey, who owned it until 1967. Its next appearance was more than a half-century later, on the occasion of the dispersal of d’André’s collection in 2021.

I have established friendly relations with Opera Lafayette board member Nizam Kettaneh, a result of his regular research sojourns in Paris in the music reading rooms of the BnF. Knowing Kettaneh’s taste for the rare repertoires of the pre-revolutionary period, I related the BnF’s desire to acquire this manuscript, while making no secret of

the budget scarcity in which my department found itself at the time. (Before its sale, the score was valuated between 20,000 to 25,000 euros.) Kettaneh immediately agreed to support our purchase of the document. In return, we granted a year-long period of exclusive performing rights to Opera Lafayette, allowing the company to present the modern premiere of Léandre et Héro in Washington, DC, and New York. Kettaneh helped to raise 25,000 Euros, thanks to his own generosity and that of Ishtar Kettaneh Méjanès, Jean-Bernard Wurm, and Albert Attié. Fortunately, the bids at auction did not exceed the ceiling that we had set for ourselves. The manuscript was obtained for 26,000 euros; other potential buyers may have been drawn more to its splendid binding than to the musical treasures this binding contains.

The plot of Léandre et Héro is drawn from Greek mythology, as popularized in two poems of Ovid’s Heroides. The opéra-ballet of Laujon and de La Garde was conceived as the third and last entrée (act) of La journée galante, and it is probably for this reason that it does not begin with an overture. The stage depicts the city of Sestos on one side (the libretto erroneously denotes “the island of Sestos”), a temple of Venus on the other, and the sea in the background (Fig. 6).

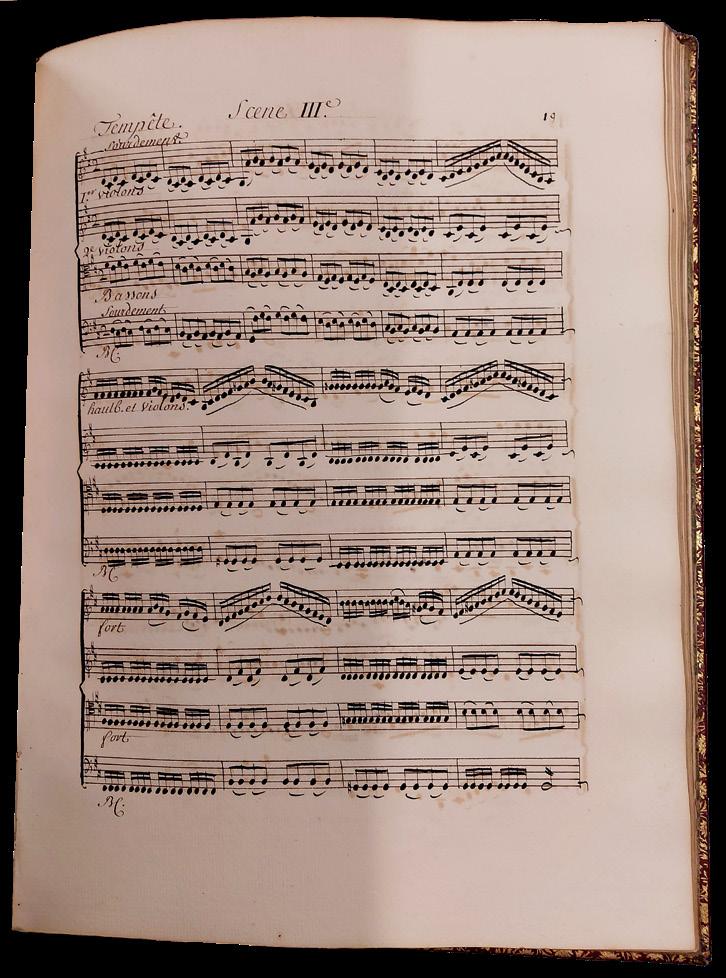

At the outset, it is night: Leander (performed by the vicomte de Rohan at the Versailles premiere) and Hero (initially performed by Madame de Pompadour) exchange loving words, while describing the animosity of their parents, who oppose their union. Because of the love that animates her, Hero has been chosen as a priestess of Venus. Dawn breaks and the lovers must part. Leander throws himself into the sea and is carried away by the waves. In the second scene, Hero is alone onstage and laments. She envies the fate of the birds, whose song is imitated by a flute solo. A chorus of priestesses invites her to celebrate Love at daybreak, but she has no desire to do so. The beginning of the third scene is marked by a solemn orchestral introduction, followed by the arrival of the inhabitants of Sestos, who praise Venus and Love with their songs. The celebration, punctuated by two minuets, is interrupted by a storm (Fig. 7). The memoirs of the duc de Luynes relate that this number seemed long at the time of its premiere; it also posed technical difficulties for the stagehands and the small orchestra of Madame de Pompadour’s theater.

The storm is rendered by the full orchestral forces in rushing scales and chords (thirds and fifths repeated at a rapid pace). It continues through the following three scenes: a chorus of sailors struggling against the raging sea sings its terror (fourth scene); Leander is engulfed by the waters (fifth scene); Hero, consumed by grief, throws herself into the sea (sixth scene). Neptune (played at Versailles by the marquis de La Salle) then puts an end to the storm and welcomes the lovers in his palace (seventh scene). Leander is led

there by the Tritons, and Hero by the Nereids, to the accompaniment of the divinities of the Sea. The lovers rejoice in their meeting and sing praises to Neptune, who unites them in immortality. The chorus then celebrates the triumph of Love. The eighth and final scene ends with a contredanse.

Léandre et Héro did not enjoy the same renown as the other extracts of Laujon and de La Garde’s operatic trilogy. It received neither the artistic acclaim of Æglé, which was revived at the Paris Opéra over ninety times between 1751 and 1777, nor the political success of La toilette de Vénus, which seemed to have been favored by Madame de Pompadour. The royal mistress commissioned from François Boucher two paintings inspired by this latter work: The Toilette of Venus, now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and The Bath of Venus, now at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. Let us hope that Léandre et Héro will find new life as a result of Opera Lafayette’s revival, and that we will one day be able to hear La journée galante in its entirety, as it first held the stage at Versailles over 270 years ago.

On the history of the département de la Musique and its collections:

1. Mathias Auclair, “De la section Musique à la création du département,” in Histoire de la Bibliothèque nationale de France, ed. Bruno Blasselle and Gennaro Toscano (Paris: Bibliothèque nationale de France, 2022), 378–384.

2. Mathias Auclair (ed.), Trésors de la musique classique: partitions manuscrites, XVIIe-XXIe siècle (Paris: Textuel, BnF éditions, 2018).

3. François Lesure, “The Music department of the Bibliothèque nationale,” Notes 35 (1978): 251–268.

4. Catherine Massip, “La musique à la Bibliothèque nationale de France. 1: Les sources écrites,” Fontes artis musicae 47, no. 2–3 (2000): 104–130.

5. Catherine Massip, Le livre de musique (Paris: Bibliothèque nationale de France, 2007).

On the Théâtre des Petits Cabinets:

6. Émile Campardon, Madame de Pompadour et la cour de Louis XV au milieu du XVIIIe siècle. Ouvrage suivi du catalogue des tableaux originaux, des dessins et miniatures vendus après la mort de Mme de Pompadour, du catalogue des objets d’art et de curiosités du Mis de Marigny, et de documents entièrement inédits sur le théâtre des petits cabinets… (Paris: Plon, 1867).

7. Adolphe Jullien, Histoire du théâtre de Mme de Pompadour, dit théâtre des Petits Cabinets..., (Paris: J. Baur, 1874).

8. Louis Dussieux and Eudore Soulié (eds.), Mémoires du duc de Luynes sur la Cour de Louis XV (1735–1758), 17 vols. (Paris: Firmin-Didot frères, 1860-1865).

Opéra-ballet: de La Garde’s Léandre et Héro & Rameau’s Io

On the manuscript of La toilette de Vénus and Léandre et Héro:

9. The manuscript of La toilette de Vénus and Léandre et Héro is held in the music department of the Bibliothèque nationale de France under the call number: RES VMA MS-3028. It is mentioned and described in the catalogues below:

10. Catalogue des livres de la bibliothèque de feu M. le duc de La Vallière [Texte imprimé]. Première partie, contenant les manuscrits, les premières éditions, les livres imprimés... dont la vente se fera dans les premiers jours du mois de décembre 1783, 4 vols. including 1 supplement (Paris: G. De Bure, 1783). The sale took place on 12 January 1784. See Volume 2, page 480, n°3527.

11. Catalogue de la bibliothèque de M. le comte René de Béarn... Vente à Paris, hôtel des commissairespriseurs, 24–26 juin et 15–18 novembre 1920, 25–26 avril 1921 et 19–21 juin 1923, 4 vols. (Paris: L. Gougy, 1920–1923). See Volume 3, page 33, n°77.

12. Catalogue of the celebrated library of Major J. R. Abbey. The third portion: [auction, 19 – 21 June 1967] London, Sotheby’s (London: Sotheby’s, 1967). See n°1968.

13. Bibliothèque théâtrale du comte Emmanuel d’André: livres et manuscrits: vente, Paris, 11 juin 2021 (Paris: Binoche et Giquello, 2021). See pages 20–21, n°22.

Like Nélée et Myrthis and Zéphire, Io belongs to Rameau’s catalog of unperformed, undated works—works for which the librettist, the circumstances of composition, and the intended venue remain unknown. To additionally classify Io as “unfinished,” though, would make it the only such case in the composer’s entire lyric output. I shall therefore set forth another argument. While several of Rameau’s scores are regrettably lost—Samson, Linus, Lisis et Délie, and all of the opéras comiques—we have confirmation that these works were completed at some point in their history. In the only surviving musical manuscript of Io, the central scenes of action are intact. An exposition presents the main characters (Io, Jupiter, Apollo, and Mercury); obstacles are developed and subsequently resolved (the two deities, Jupiter and Apollo, compete for the affections of the titular nymph, with Jupiter emerging triumphant). Two key elements, however, are missing from this source, namely: the overture (or at least an introductory ritornello) and the remainder of a “divertissement” that is launched in scene 6 (with the Entry of the Graces, the Pleasures and the Games in disguise) and interrupted in scene 7 (with the arrival of Folly). In French Baroque opera, a “divertissement” was a musical sequence placed at the end of each act, “suspending” the dramatic action through a series of dances, airs, and concerted ensembles that were linked directly or indirectly to the primary action. In actes de ballet like Io, the “divertissement” tended to be joyous, festive, and conclusive in character.

Might Io have been shorn of its divertissement after its completion so that this material could be reused elsewhere? Such a procedure was not uncommon in Rameau’s output. On numerous occasions the composer excised music from one work to be placed into another; this was a particularly desirable strategy if the original work had not been performed or had little chance of being revived. If Io’s divertissement was indeed “recycled,” its ultimate destination may have been a much better-known opera: Platée. To confirm the relationship between Io and Platée, I will demonstrate the similarities between the two pieces on the levels of both text and music, placing an emphasis on parallels in the role of Folly. I will then consider the potential associations between Io, the Marquise de Pompadour, and Rameau’s social circle. To conclude the essay, I will present our editorial proposal to “finish” Io within the framework of Rameau’s Opera omnia (complete works edition).1

In the librettos: “Assist me”

Like the other works by Rameau that went unstaged, the libretto of Io has not been preserved. This state of affairs is unsurprising: because librettos served to present the text of an opera, as well as the cast of singers and dancers in a particular production, they were only printed when an opera was actually performed. The preparation of a dramatic text always preceded the composition of corresponding music, for the former had to pass through the filter of Crown censorship. Given this context, it would have been uncharacteristic for Rameau to have set Io to music if the libretto had not been completed and then approved by him.

The intrigue of Io’s plot derives from the comic trope of deities in disguise. Jupiter (appearing as Hylas) and Apollo (appearing as Philemon) cast off their divine status, each setting out to seduce the eponymous nymph. Mercury arrives to inform Jupiter that his jealous wife, Juno, suspects him of a new infidelity; Jupiter, however, remains resolute in his plan of seduction. Mercury next informs Jupiter of Apollo’s own intentions for Io. To test the nymph’s preferences, Jupiter invites her to declare her love for his rival. The resulting misunderstanding tilts the tenor of the action toward the comic. At this juncture, a hopeful Apollo presents himself to Io. A rapid exchange between the three protagonists follows: the nymph is cornered into choosing between the two gods. She discovers with amazement that Hylas is none other than Jupiter himself. Impervious to the threats of the righteous queen, the illegitimate couple rejoices. Meanwhile Apollo, crestfallen by his defeat, abandons his pursuit. Folly then steals Apollo’s lyre and indulges her “delirium.” She animates a divertissement to celebrate the union of Jupiter and his beloved nymph:

Io, sc. vii (From the manuscript: F Pn Vm2. 311) FOLLY

Happy inhabitants of this pleasurable grove, I come to augment your amusement.

I arrive from Parnassus, at this moment in uproar: Apollo has been overwhelmed by this outrage, He deserts his empire and leaves it to plundering.

As a host of lofty spirits

Fights over ancient manuscripts,

I—one hundred times luckier—have stolen the god’s lyre, And indulging in my delirium,

I wish to try it out with you at this moment. Assist me…

The manuscript of Io ends here.

The character of Jupiter forms a through-line between Io and Platée. In the latter work, however, the god is undisguised, and he only pretends to seduce Platée, the batrachian marsh-nymph of the opera’s title. Platée is naive, like her predecessor. But in contrast to Io, she is ungainly, nymphomaniac, and ridiculous. The general action is as follows: Jupiter descends on a cloud, with the intention of redirecting his wife’s jealousy through means of feigned attraction. The plan is successful: when Juno becomes aware of Platée’s ugliness, she understands that her husband has set up the deception. Folly enters at the end of Platée’s second act, just as Jupiter has convinced the gullible marsh-nymph that he loves her and wishes to wed. After announcing that she has stolen Apollo’s lyre, Folly presents a series of breathtaking airs, concluding with a “stroke of genius.”

Turning to Momus and his retinue, she asks for “assistance,” just as she did in the parallel moment in Io:

Platée, II, sc. v MOMUS

What do I see? Oh Heavens!

FOLLY

It is me, it is Folly Who has just stolen Apollo’s lyre.

[…]

I want to conclude With a stroke of genius. Assist me, I feel I can reach A masterpiece of harmony.

The points of similarity between the librettos of Io and Platée are enlightening. As we have observed, the characters of Folly and Juno appear in both works; these figures are found nowhere else in Rameau’s output. What is more, essential dramaturgical elements are shared between the two plots. Common threads include Jupiter’s seduction of a naïve nymph, Juno’s famed jealousy, and the sudden appearance of Folly, who steals Apollo’s lyre to enliven the “divertissement” and indulge in her “delirium.”

It seems plausible, then, that the divertissement originally written for Io was recycled in Platée, perhaps after the aborted production of the former. (A similar chain of events played out with Lysis et Délie. Although a copyist’s bill confirms that the pastorale was completed, it was removed from the program a few days before its scheduled premiere.)

Rameau may well have excised the relevant materials from the score of Io, and then integrated and adapted them into the second act of Platée. For the composer, there would have been nothing unusual about this behavior: in fact, pages corresponding to the overtures are missing from the autographs of La naissance d’Osiris, Le retour d’Astrée, Les surprises de l’amour, Daphnis et Églé, and Zéphire. While these musical extracts have not been found in any of the composer’s other manuscripts, this does not preclude their transfer elsewhere, given that only eight autographs in Rameau’s entire opus have been preserved. While today we consider scores in the composer’s hand to be fixed and “sacred,” this was decidedly not the case in the eighteenth century. Rameau himself would cut pieces out of his manuscripts when he needed paper to make pasted-over corrections in other works.

If the autograph manuscript of Platée had survived, the pages of Io’s divertissement might well have been found there. Unfortunately, however, the autograph of Platée is no longer extant. Making matters worse, the score made for the opera’s Versailles premiere was only partially preserved, thwarting a faithful reconstruction. (This production took place on March 31, 1745, celebrating the marriage of the Dauphin to Maria Theresa of Spain.) Another piece of evidence, though, confirms that the divertissement of Io was suppressed very early on in the history of its manuscript. When Rameau’s eldest son, Claude-François, put his father’s papers in order after his death, he came into contact with Jacques-Joseph-Marie Decroix, a great collector of the composer’s works. Claude-François sent Decroix several autographs to be used to produce backup copies of Rameau’s oeuvre. Among them, the younger Rameau wrote, was “an acte de ballet entitled Io without divertissement.” The situation was so unusual, in other words, that Claude-François felt compelled to point out the anomaly.2

The possible links between Io and Platée do not stop here. While Rameau had long held plans to set Jacques Autreau’s Platée to music, the project struggled to get off the ground. The delay might be attributed to the bitterness Rameau felt after the failure of Dardanus in 1739, or to the quarrels that still raged between the composer’s supporters and those of Lully (this despite the success of Les fêtes d’Hébé). It is also possible that Rameau was only moderately satisfied with Autreau’s text. To avoid any conflicts of interest, the composer had made the habit, after the creation of Les Indes galantes in 1735, of buying the rights to the librettos he set to music: Mr. Rameau, who during the author’s [Autreau’s] lifetime had purchased the manuscript of this work [Platée], was unhappy with the way it was organized, and has borrowed a foreign hand to make various changes.

[…] They are numerous; some concern the distribution and arrangement of the dramatic scenes, others the dialogue.3

It was Adrien-Joseph Valois d’Orville, a regular writer for the fairground theater and one accustomed to collaborative work, whom Rameau solicited to bring lightness and humor to Autreau’s original text. According to the marquis d’Argenson, Alexandre Le Riche de La Pouplinière—Rameau’s employer from about 1735 onward4—also contributed to the text:

M. de La Pouplinière, tax collector, played a substantial role in the composition of the verses of Platée; he was the friend of Autreau.5

Rameau had always been drawn to the wit of the fair. His collaboration with Alexis Piron on several opéras comiques attests to this fact. (These comic works include L’endriague, L’enrôlement d’Arlequin, Le pucelage ou La rose, and La Robe de dissension, all dating between 1723 and 1726. Rameau was far from skeptical of this festive and audacious environment. Indeed, he accepted an invitation from Jean Monnet, director of the fairground Opéra-Comique, to conduct the troupe’s orchestra in L’ambigu de la folie, ou Le ballet des dindons, Favart’s parody of Les Indes galantes, which was then on the boards at the Opéra.6 The titles and the characters of the acts were only slightly modified—Le bon Turc, Les Incas, Les sauvages, La fête persane. The exception here was the prologue, which featured Folly and a sanctimonious churchgoer:

Les Indes galantes was then being performed at the Opéra. Mr. Favart, who had been kind enough to work for my theater as supervisor of the plays and their rehearsals, made a parody of the opera which had the greatest of success. Here the young ladies Puvigné and Lani, alongside Mr. Noverre, distinguished themselves in a pas de trois in the act of the Flowers, taking the names of Rose, Zephyr and Borea. These three subjects were directed by Mlle Sallé, MM. Dupré et Lani; the orchestra by Mr. Rameau; the decorations and costumes by Mr. Boucher.7

Rameau lacked neither playfulness nor humor. He had a certain detachment from the social conventions of his time. Toward the end of his career, he would return to this light-hearted register: first in 1758 with Le procureur dupé sans le savoir, and then in 1760 with the madcap comedy Les Paladins—a work that utterly baffled the conservative audience of the Paris Opéra.

Where did the idea for the character of Folly come from? From Valois d’Orville? From Rameau, enticed by Favart’s idea? From La Pouplinière? Whatever the inspiration, the idea clearly unleashed the composer’s inventiveness, culminating in the exceptional

musical “show” in Platée. Here, Rameau displays a breathtaking talent; the composer puts himself on stage both to defend his theories on the power of music over text and to thumb his nose at detractors who maintained that he was “crazy,” even if highly gifted. As Voltaire put it: He is crazy; but I still maintain that one must take pity on talented people. For the author who created the act of the Incas [Les Indes galantes], it is permissible to be wild.8

Given these analogies between the texts of Io and Platée, it seems plausible that they were written by the same author. There arises one last complication, though, since Platée’s libretto had multiple contributors: Autreau, who wrote the original version that lacked the character of Folly; Valois d’Orville, who adapted Autreau’s text into a ballet bouffon; and also La Pouplinière, a friend of Autreau’s and a devotee of the fairground theater.

All of these scenarios are plausible without one taking precedence over the other. What is certain, however, is that the text of Io preceded that of Platée.

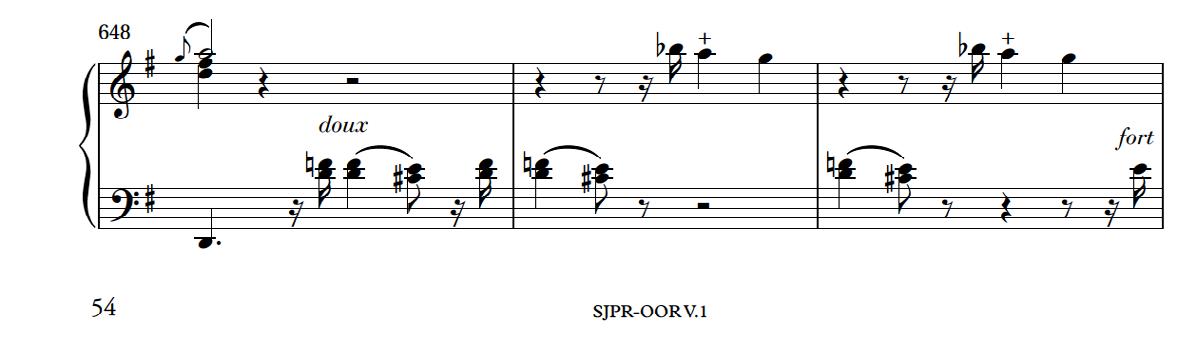

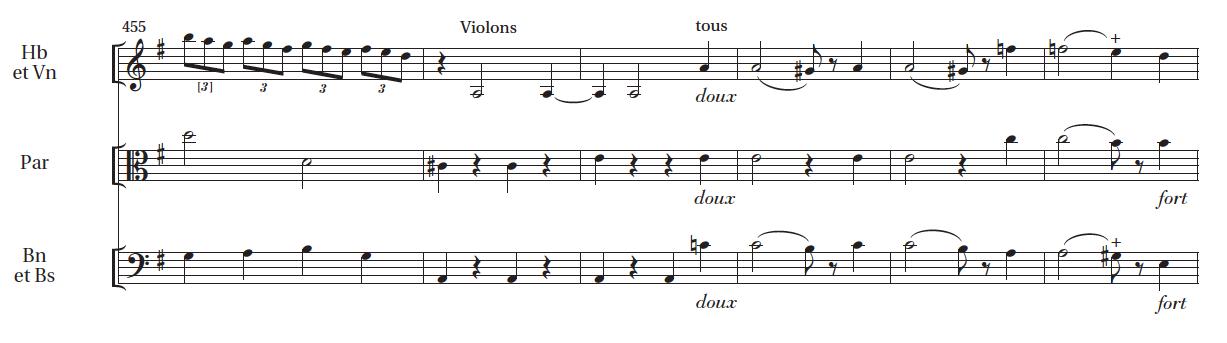

In addition to these links of characters and plot, there are numerous musical connections between Io and Platée. For instance, the musical storm in Io—conjured by Jupiter to impress the nymph—prefigures the much more developed tempest at the end of Platée. Other similarities are even more convincing, though at the same time more puzzling, for they are found in the only substantial choreographic music extant in Io (the Entrée pantomime des Grâces, des Plaisirs et des Jeux déguisés, which introduces the missing divertissement of scene 6). It turns out that several musical features of this Entrée pantomime were further developed in two extracts from Platée: the Air pour les Fous gais (Air for the happy madmen) and the ariette of Folly, “Aux langueurs d’Apollon, Daphné se refusa” (“To the passion of Apollo, Daphne refused to give herself”). First, the harmony and melodic line of the opening measures of Io’s Entrée pantomime reappear at the beginning of the Air pour les Fous gais, in measures 444–45 of Platée (Fig. 1a-b). Moreover, the modulating bars 624–25 and 648–50 of Io (Fig. 2a) are reused in measures 457–60 and 483–86 of Platée (Fig. 2b).

Opéra-ballet: de La Garde’s Léandre et Héro & Rameau’s Io

Finally, cadential formulas deriving from the Entrée pantomime of Io (Fig. 2a, mm. 627–29) are repeated twice in the well-known ariette from Platée, “Aux langueurs d’Apollon, Daphné se refusa” (Fig. 3).

If one accepts that the divertissement of Io inspired that of Platée, the composition of the former must have taken place before the court premiere of the latter (i.e. March 31, 1745). As we have also established, it was common for large sequences of music to be recycled from unperformed or infrequently performed works. For example, the Entrée pantomime from Io, discussed in the previous section, was entirely reused in 1751 in La guirlande, under the new title Pantomime pour les Berges et Bergères, Pâtres et Pastourelles.

Along similar lines, the duet between Io and Apollo, “Jupiter lance la foudre” (sc. 4), can also be found in the first version of the prologue of Les fêtes de Polymnie. Rameau reworked the music and the text, entrusting the duet to the characters of Mnemosyne and the Chief of Arts, before later excising the passage. (The latter work seems to have been intended for a court celebration of Louis XV’s victory at Fontenoy–a battle which had taken place on May 11, 1745. In the end Le temple de la Gloire fulfilled this function, staged at Versailles in November of 1745; Les fêtes de Polymnie was then presented at the Opéra, premiering on October 12 of that same year.) These chronological links between Io and multiple works dating from 1745 (Platée in March and Les fêtes de Polymnie in October) and from 1751 (La guirlande) would seem to confirm the anteriority of Io.

We should underscore that there is a possible association between the Marquise de Pompadour and the conception of Rameau’s ballet. Around the time that Io was written, Pompadour was still Jeanne-Antoinette Poisson. (She had been ennobled through her 1741 marriage to Le Normant d’Étiolles.) The young woman’s charm and beauty–linked to her taste for the arts, as well her talents as an actress, singer, and equestrian–facilitated her spectacular rise within the Parisian social scene. On July 18, 1742, President Hénault wrote to his friend Madame Du Deffand: [Pompadour] knows music perfectly, she sings with every possible gaiety and taste, is familiar with a hundred songs, and acts in plays at Étiolles, on a stage as beautiful as that of the Opéra, with impressive machinery and scenic effects.9

Pompadour’s ambition, of course, was to become the mistress of Louis XV. Invited to a masked ball at Versailles on February 25, 1745, she quickly aroused the interest of the monarch. Numerous courtiers in attendance commented on the event–taking note of this delightful noblewoman for whom the king openly expressed his desire. Might these rumors have provided a wordsmith within Rameau’s circle with the idea for Io–someone like La Pouplinière, with whom Rameau would soon collaborate on the libretto of Platée? Might the composer have produced a short ballet, with just a handful of characters, for the private theater of his employer? (The workforce of the latter theater, certainly, echoed the reduced number of players required for Io.) Is it for this reason that a set of parts for Io has survived–justifying through their very existence that a performance was once planned? In the absence of certainty, we must content ourselves with such suggestive, but ultimately unanswerable, questions.

As we have established, Rameau’s three one-act ballets—Nélée et Myrthis, Zéphire, and Io—remained unpublished in the composer’s lifetime. In the first two cases an autograph manuscript was preserved; for Io, by contrast, we have only the belated copy of the score and parts that belonged to Decroix (the famed Rameau collector). In the second volume of the Recueil de ballets en un acte mis en musique par Rameau (Collection of ballets in one act set to music by Rameau), Decroix specifies that the works contained therein, including Io, were “collected and copied from the original scores of the Author,” which he had received from Rameau’s son in July of 1777. The manuscript of Io that Decroix had copied must, then, date from 1777 or before.10 As for the other musical sources–a grouping that lacks the parts for Io, Mercury, and Folly–were these commissioned specifically by Decroix and, if so, why?11 At first glance, it seems unlikely that these documents stemmed from a planned staging at the private theater of La Pouplinière, for the two violin parts are notated in a different clef than that typically used in Rameau’s time. And yet, the name of a certain “Mr. Le Petit” is inscribed on the vocal part corresponding to the role of Apollo, which implies that this particular source was intended for performance. Le Petit was employed by the Paris Opéra between 1756 and 1764, serving as an understudy to the haute contre soloists. He could plausibly have been approached, in the early days of his career, to perform this role for La Pouplinière. (Le Petit participated, notably, in the production of Rameau’s Les Paladins in 1760, doubling his friend Lombard in the role of Atys; he would later work for the lyric theaters of Bordeaux [1772–73] and Brussels [1776].)

It is with these questions, these doubts, but also these convictions, that the editors of Rameau’s Opera Omnia have decided to complete Io by incorporating within it musical elements that have passed down to us via the original version of Platée. (Thomas Soury is charged with preparing the critical edition for the work.) This ambitious and impactful initiative allows us to put forward a finalized version of Io—and thereby, after nearly three centuries, to grant the composition a form of rebirth. In 1750, Rameau wrote: Art will always remain in narrow limits, so long as it lacks accredited protectors (Démonstration du principe de l’harmonie, p. 94; CTW, t. 3, p. 213).

Thanks to the programming of Opera Lafayette, Rameau’s broader vision for Io has at long last been realized.

Opéra-ballet: de La Garde’s Léandre et Héro & Rameau’s Io

1. Jean-Philippe Rameau, Io, ed. Thomas Soury, OOR V.1, under the general direction of Sylvie Bouissou.

2. Sylvie Bouissou and Denis Herlin, Jean-Philippe Rameau, Catalogue thématique, Musique instrumentale; Musique vocale religieuse et profane (Paris: Bibliothèque nationale de France and CNRS Éditions, 2007), 1: 33–34.

3. Rémond de Sainte Albine, “Observations de M. Remond de Sainte Albine sur le ballet, intitulé Platée,” Mercure de France, March 1749, 191.

4. Sylvie Bouissou, Rameau, musicien des Lumières (Paris: Fayard, 2014), 283–285.

5. René Louis de Voyer de Paulmy, marquis d’Argenson, Notices sur les œuvres de théâtre, ed. H. Lagrave, Studies on Voltaire and the Eighteenth Century (1966), 42: 99.

6. Charles-Simon Favart, L’ambigu de la folie, ou Le ballet des dindons (F Pn ms. fr. 9325, f. 413).

7. Mémoires de Monnet, ed. H. d’Alméras (Paris, Louis- Michaud, s.d.), 85–86. The editor is incorrect in suggesting that this pertains to the 1751 revival of Les Indes galantes.

8. Voltaire, Correspondance, ed. Theodore Besterman (Paris: Gallimard, 1977), letter no 1854, 913.

9. Correspondance complète de la marquise Du Deffand (Paris: Plon, 1865), 1: 70.

10. The manuscript of Io from the Decroix collection is currently held at the Bibliothèque nationale de France, with the call number: F-Pn, Vm2. 316.

11. The parts of Io are held at the Bibliothèque nationale de France, with the call number: F-Pn Vm2. 324.

“Nothing quite prepared me for the sheer joy of seeing Machine’s work in person; it’s imaginative, extravagant, and thoroughly American in the way he uses ordinary objects to extraordinary effect.”

– Ryan Brown, Artistic Director, Opera Lafayette

“Machine’s costumes are just going to blow the world apart.”

– Nick Olcott, Stage Director–Machine Dazzle, on costumes for Rameau’s Io

“Oh, there she is, I just gave her the cutest little face… It’ll be fun! There’s classical reference, but it’s just done in a modern way with some unexpected things.”© Gregory Kramer Machine Dazzle © Little Fang © Geoff Winningham Photos above are of past Machine Dazzle works

Opéra-ballet: de La Garde’s Léandre et Héro & Rameau’s Io

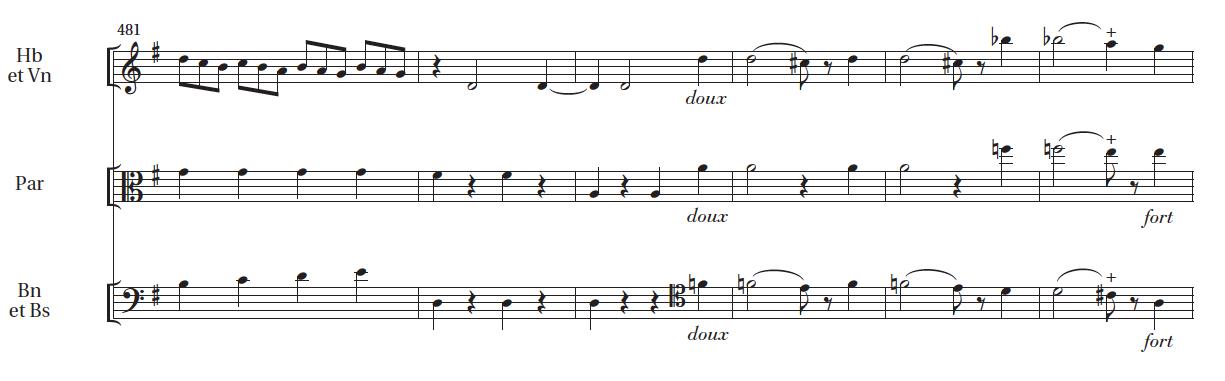

Why does the Rococo echo so strongly across music, design, and art today?1 And how might we better understand the continuing excitement, innovation, and impact of this visual and musical mode? These are questions for all of us who take a serious interest in the reverberations of the past and the present, the echoes, transformations, and continuations of genres and modes across historical space and time, and they are particularly appropriate on the occasion of Opera Lafayette’s ambitious twenty-first-century reconstruction and revival of the musical and visual culture of the French Rococo and the circle of Pompadour.