Analog Devices’ commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) software-defined radio (SDR) system-on-module (SOM) digitizers enable customers to deploy high performance distributed sensing techniques at the tactical edge, as quickly as possible.

Editor’s Perspective

7 Making the case for MOSA By

John M. McHale III

Connecting with Mil Embedded

30 By Lisa Daigle

Subscribe to the magazine or E-letter

Live industry news | Submit new products http://submit.opensystemsmedia.com

WHITE PAPERS – Read: https://militaryembedded.com/whitepapers

WHITE PAPERS – Submit: http://submit.opensystemsmedia.com

SPECIAL REPORT: Tech for position, navigation & timing (PNT) applications

8 Beyond GPS: HORDE PNT for contested environments By Evan Alexander, Microchip Technology

12 Beyond GNSS/GPS: magnetic navigation and multisensor resilience in contested skies By Ken Devine, Sandbox AQ

14 Building a layered, aware PNT architecture for the modern battlespace By Sean Gorman, Zephr.xyz

MIL TECH TRENDS: Military power supplies

18 Power under pressure: Meeting the military’s surging energy demands By Dan Taylor, Technology Editor

22 “More-electric” aircraft and efficient power management By Sanjeev Sachan, TT Electronics

:

Open standards for embedded systems: FACE, SOSA, CMOSS, VPX, and more

26 The FACE Technical Standard: Enabling modular, open, and future-proof avionics systems By Joe Richmond-Knight, Sysgo

© 2025 OpenSystems Media

© 2025 Military Embedded Systems

To unsubscribe, email your name, address, and subscription number as it appears on the label to: subscriptions@opensysmedia.com

Position, navigation, and timing (PNT) technology continues to evolve to enable warfighters to work with GPS and in GPS-denied environments. U.S. Marine Corps Sgt. Brian Kim, an explosive ordnance disposal (EOD) technician with Task Force Koa Moana (TF KM) 20, I Marine Expeditionary Force (MEF), acquires GPS coordinates while conducting a transfer of responsibility of unexploded ordnance (UXO). U.S. Marine Corps photo by Sgt. Stephanie Cervantes.

https://www.linkedin.com/groups/1864255/

Mercury’s DRF5270 is a SOSA ™ aligned board designed to accelerate deployment and simplify RF system design. It delivers synchronized, multichannel signal processing in a rugged package.

FEATURES

Eight channel 64GSPS converters

16 GB of DDR4 SDRAM

10 GigE Interface

40 GigE Interface

Optional VITA 67.3C optical interface for gigabit serial communication

Dual 100 GigE UDP interface

Flexible system-on-module design enables migration to other form factors

Board Support Package (BSP) for software development

FPGA Design Kit (FDK) for custom IP development

mrcy.com/drf5270

24 ACCES I/O Products, Inc. – M.2 –the new, more flexible alternative to PCIe mini cards 9 ADL Embedded Solutions –Bringing scalable AI compute to the edge

AirBorn – 2300W+ VPX power module 2 Analog Devices, Inc. –Solutions for rapid deployment 3 Annapolis Micro Systems –64 GS/s direct RF is at hand!

Behlman Electronics, Inc. –No one powers the army like Behlman

Dawn VME Products –Dawn powers VPX

Elma Electronic –Leaders in modular open standards enabling the modern warfighter

embedded world

Connecting the embedded community: 10-12.3.2026, Nuremberg, Germany

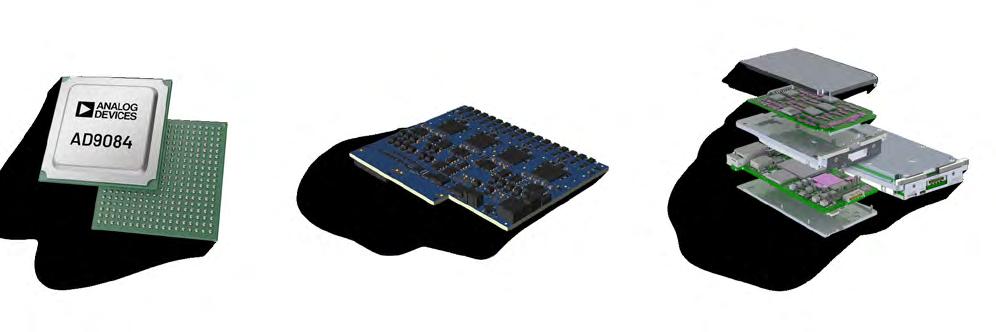

GMS – Viper: The world's most advanced battlefield cross domanin OpenVPX mission computer

International Manufacturing Services, Inc. – Passive solutions with a purpose

Mercury Systems, Inc. – Stay ahead with synchronized Direct RF

Micro-Coax, an Amphenol company –Times Microwave Systems and Micro-Coax Redefine RF Solutions 27 ODU-USA – Soldier system connectors

PICO Electronics Inc –DC-DC converters, transformers & inductors

Sealevel Systems, Inc. –Engineering Power-Efficient Hardware for AI at the Edge

Embedded Tech Trends (ETT) 2026

January 26 & 27, 2026 Savannah, GA

https://embeddedtechtrends.com

Sea-Air-Space 2026

April 19-22, 2026

National Harbor, MD

https://seaairspace.org/

AUVSI Xponential 2026

May 11-24, 2026 Detroit, MI

https://xponential.org

GROUP EDITORIAL DIRECTOR John McHale john.mchale@opensysmedia.com

ASSISTANT MANAGING EDITOR Lisa Daigle lisa.daigle@opensysmedia.com

TECHNOLOGY EDITOR – WASHINGTON BUREAU Dan Taylor dan.taylor@opensysmedia.com

CREATIVE DIRECTOR Stephanie Sweet stephanie.sweet@opensysmedia.com

WEB DEVELOPER Paul Nelson paul.nelson@opensysmedia.com

EMAIL MARKETING SPECIALIST Drew Kaufman drew.kaufman@opensysmedia.com

WEBCAST MANAGER Marvin Augustyn marvin.augustyn@opensysmedia.com

VITA EDITORIAL DIRECTOR Jerry Gipper jerry.gipper@opensysmedia.com

DIRECTOR OF SALES Tom Varcie tom.varcie@opensysmedia.com (734) 748-9660

STRATEGIC ACCOUNT MANAGER Bill Barron bill.barron@opensysmedia.com (516) 376-9838

EAST COAST SALES MANAGER Bill Baumann bill.baumann@opensysmedia.com (609) 610-5400

SOUTHERN CAL REGIONAL SALES MANAGER Len Pettek len.pettek@opensysmedia.com (805) 231-9582

DIRECTOR OF SALES ENABLEMENT Barbara Quinlan barbara.quinlan@opensysmedia.com AND PRODUCT MARKETING (480) 236-8818

INSIDE SALES Amy Russell amy.russell@opensysmedia.com

STRATEGIC ACCOUNT MANAGER Lesley Harmoning lesley.harmoning@opensysmedia.com

EUROPEAN ACCOUNT MANAGER Jill Thibert jill.thibert@opensysmedia.com

TAIWAN SALES ACCOUNT MANAGER Patty Wu patty.wu@opensysmedia.com

CHINA SALES ACCOUNT MANAGER Judy Wang judywang2000@vip.126.com

CO-PRESIDENT Patrick Hopper patrick.hopper@opensysmedia.com

CO-PRESIDENT John McHale john.mchale@opensysmedia.com

DIRECTOR OF OPERATIONS AND CUSTOMER SUCCESS Gina Peter gina.peter@opensysmedia.com

GRAPHIC DESIGNER Kaitlyn Bellerson kaitlyn.bellerson@opensysmedia.com

FINANCIAL ASSISTANT Emily Verhoeks emily.verhoeks@opensysmedia.com

SUBSCRIPTION MANAGER subscriptions@opensysmedia.com

By John M. McHale III

John.McHale@opensysmedia.com

Six years have passed since the tri-service memo was issued by the Air Force, Army, and Navy leadership mandating the use of a modular open systems approach (MOSA) in all new programs and technology refreshes. Many in the defense community were already embracing MOSA strategies and leveraging open standards, but having the three services mandate it promised faster adoption. Update: It’s happening. MOSA is already the law and now defense secretary Pete Hegseth is dictating a MOSA approach as part of his efforts to reform and speed up the defense acquisition process.

No one would argue that the defense acquisition process is anything faster than glacial, so the reforms promised by Hegseth and his team are welcome; it’s true, however, that attempts to change the mammoth bureaucracy slowing things down have been proposed before, with little change.

Many in the industry saw the roadblocks in the current infrastructure as too daunting, so new processes to test, develop, and procure technology were created outside of the bureaucracy. Rapid-acquisition offices were set up, Other Transactional Authorities (OTAs) got dusted off, the Defense Innovation Unit (DIU) and Space Development Agency (SDA) were created to leverage commercial innovation to deploy it to the field as fast as possible. Alternative processes also provide a gateway for nontraditional or smaller defense suppliers to gain entry into the defense market, as do MOSA initiatives like the Future Airborne Capability Environment, or FACE, and the Sensor Open Systems Architecture, or SOSA, Consortia.

With a memo dated November 7, 2025, Secretary Hegseth is basically saying that previous efforts have not been enough to accelerate acquisition, stating that the U.S. military acquisition process needs to assume a wartime footing and “dramatically accelerate the fielding of new technology.” Along those lines, he renamed the Defense Acquisition System (DAS) to the Warfighting Acquisition System.

Calling the current acquisition system “unacceptably slow,” Hegseth said to speed it up, the Department of Defense (DoD) will need to overcome three systemic challenges:

“(1) fragmented accountability where no single leader has the necessary authorities to lead our programs and urgently deliver results; (2) broken incentives that reward completely satisfying every requirement and specification at significant cost to ontime delivery; and (3) government procurement behaviors that disincentivize industry investment, efficient production, and growth, leading to constrained industrial capacity that cannot surge or adapt quickly.”

The memo, titled “Transforming the Defense Acquisition System into the Warfighting Acquisition System to Accelerate Fielding of Urgently Needed Capabilities to Our Warriors,” goes on to establish that Portfolio Acquisition Authorities (PAEs) will be set up to reorganize “existing Program Executive Offices” to prioritize speed.

PAEs will be tasked with maximizing “use of Modular Open System Architectures (MOSA) for development programs moving forward by obtaining delivery of critical system interfaces with government purpose rights enable modular competition and supply chain resiliency.”

The change promised by the MOSA mandate and Hegseth’s reforms remind me of the atmosphere around the so-called COTS Memo more than 30 years ago, when

then-defense secretary William Perry issued a memo mandating the use of commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) components and equipment wherever and whenever possible. He was battling the bad press of $400 hammers but also looking for a way to get commercial tech more quickly to warfighters like today’s leaders. COTS caused lots of consternation decades ago, but it’s now a common form of procurement within the defense department and will enable MOSA and acquisition reforms called for by Hegseth.

We’ve compiled a MOSA e-book to track how fast MOSA is progressing and how the military leadership is fueling its momentum, featuring articles from our team of journalists and contributions from industry leaders. Read it here: https://tinyurl.com/3974fmaw.

Speakers at the MOSA Industry & Government Summit (held in late August 2025) previewed what we are hearing today from DoD leadership.

Brig. Gen. Jason Voorheis, program executive officer for the Air Force’s fighters and advanced aircraft, told summit attendees to think of MOSA “as the single most consequential lever we can pull to ensure our future warfighters have the capabilities they need to win.”

Voorheis noted that the prototype for the Air Force Collaborative Combat Aircraft (CCA) was produced in less than 18 months from award of the contract, a pace he said would have been unthinkable under older acquisition models.

A fast pace describes many of this administration’s efforts. This defense department has shown it will move quickly whether programs are popular or not, so I expect changes to happen pretty fast.

For all our MOSA coverage, please visit www.militaryembedded.com/MOSA.

By Evan Alexander

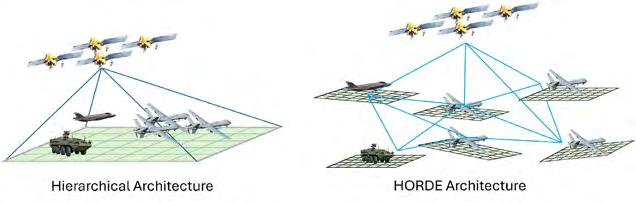

Military technology development is at an inflection point, where the surging deployment of uncrewed aerial vehicle (UAV) technology collides with the total denial of the GPS signal commonly used for position, navigation, and timing (PNT) in such platforms. These trends necessitate a transformation in the underlying PNT network architecture in military platforms. Harmonized Order of Registered and Distributed Elements (HORDE) PNT (a software tool for distributed computing) rejects the commonly deployed hierarchical PNT network architecture, opting for a decentralized approach under which PNT assets can be dispersed across a network, yet leveraged by any platform. Unlike current architectures, HORDE PNT is fundamentally designed for operation in contested environments, enabling challenging missions like coordinating a decentralized UAV swarm for coherent sensing.

In the modern theater of war, the evolution of military operations has been marked by the development of advanced technologies that require precise position, navigation, and timing (PNT). Platforms like uncrewed aerial vehicles (UAVs) enable users to leverage unprecedented capabilities in intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR), necessitating heightened levels of precision for operational coordination. In swarm operation, each platform uses GPS by continuously receiving position and time data to update relative position within the swarm. Platforms using military GPS receivers are capable of meter-level position accuracy and timing accuracy within 10 nanoseconds (1E-9)

of Coordinated Universal Time (UTC). The dependency on GPS for synchronization within and between platforms has proven to be a double-edged sword, as the concerns of GPS vulnerabilities – particularly in conflict zones – including jamming, can disrupt operations for hours or days, rendering traditional PNT systems ineffective.

GPS and the limits of hierarchical PNT architectures PNT systems have an inherent requirement for reference frame information in order to be useful. The very nature of PNT data is that it describes the relative position, motion, and time between objects. Unless a system can determine what the PNT data is relative to, PNT data is therefore meaningless. The appearance of PNT objects operating in a globally coordinated reference frame results from a PNT object aligning its local reference frame to a coordinated reference frame, such as GPS. Many PNT systems today operate in a hierarchical architecture in which GPS is at the top of the hierarchy, and downstream or adjacent systems rely on the PNT information and reference frames disseminated from GPS (UTC and WGS-84). This leader-follower architecture works well when GPS is available, but ultimately limits a platform’s ability to operate when the global reference frame is not continuously available, for example, during periods of GPS denial. (Figure 1.)

In Figure 1, the left graphic is the default method of converting PNT data to a coordinated reference frame, which simplifies the process of exchanging PNT data between systems, but levies a requirement for global coherency between PNT objects. This setup requires all PNT objects to align to the same coordinated reference frame before collaborating with one another. The right graphic is an alternative approach to enforcing global coherency. HORDE PNT is a method of sharing PNT data without enforcing the requirement to subscribe to a global reference frame like WGS-84 or UTC. GPS is extremely useful when it is available, but systems should be designed to operate whether it is present or not.

The HORDE protocol was developed to leverage harmonization as a method of synchronization and provides a mechanism for grouping systems into a decentralized horde. The harmonization process enables synchronization through the measurement of relative time and frequency offsets. All HORDE elements act as peers, with no organizational structure or hierarchy enforced for synchronization or PNT distribution. This lack of organization makes HORDE inherently resilient to disruption while still supporting the traditional method of synchronization using the distribution of coherent references as GPS does.

In this architecture, each individual network node or platform establishes and uses its own local reference frame (position, orientation, and time) independent of GPS or any other authoritative source. Nodes in a network share PNT data across the network but are only locally aware based on measurements with their neighbors. Data must be translated from a neighbor’s reference frame into the local reference frame in order to be used.

The main hurdle in implementing this model involves establishing a local reference frame for each node and then translating PNT data across the varying reference frames as data is exchanged between nodes. Methods for instantiating a local PNT reference frame using only two-way ranging measurements between platforms and the ability to translate timestamps between asynchronous platforms must be developed

to overcome this hurdle. The ability to do so enables a swarm of UAVs to cold-start without GPS, enhancing its capability as each node in the swarm discovers its neighbors and begins to share PNT data across the network and execute coordinated missions.

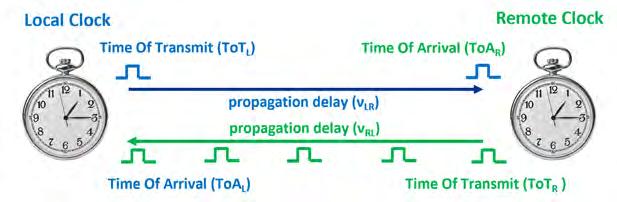

Asynchronous two-way time transfer (ATWTT) enables a system to translate data between platforms operating asynchronously, meaning their clocks are not aligned to a common reference frame and do not necessarily transfer data at the same time or rate. ATWTT works by measuring relative time offsets between local clocks and translating the time stamps into the local reference frame. PNT data then can be shared across a network and utilized by any node on the network. The HORDE protocol translation method optimally pairs PNT data and a relative time-offset measurement to maximize simultaneity. PNT data time stamp translation uses linear interpolation of the relative time-offset measurements, which are selected to maximize simultaneity. (Figure 2.)

The requirements to effectively share PNT data across a network for a swarm deployment include the accurate measurement and time stamping of the data, as well as near

instantaneous (within milliseconds) sharing of that PNT data over an RF data link. PNT and reference frame data must be time stamped with sub-100-picosecond accuracy and the data link between platforms needs to share that data in near-real-time. HORDE PNT scales to dozens of nodes but requires line-of-sight for optimal ranging accuracy in complex environments. With this architectural framework established, each node in the swarm can begin an operation, even in a completely GNSS-denied environment.

The steps to operation include:

1. Establish a local reference frame.

2. Discover the other nodes within the network.

3. Map the topology and relative positions of other nodes in the network.

4. Share PNT data across the network.

5. Cooperate on coordinate missions.

The ability to cold-start a swarm in a completely GNSS-denied environment is not suitable with the hierarchical architecture that is deployed in many military platforms today. HORDE PNT is the architectural framework required in the new age of combat where GPS is commonly unavailable and drones roam the skies. MES

Evan Alexander is a Product Manager for Microchip Technology, Government Systems Group. Evan’s team develops advanced PNT systems in support of the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD). He holds an M.S. in engineering and technology management and a B.S. in mechanical engineering from

FIRST UNIVERSAL POWER SUPPLY FOR ALL ARMY CMFF APPLICATIONS

Introducing the VPXtra® 400DW-IQI, Behlman’s first power supply with a wide range DC input that is fully compliant for all platforms in the Army CMFF program. This rugged, highly reliable switch mode 3U VPX unit meets a new standard of adaptability, and is backed by unmatched integration support from the Behlman team.

> Developed in alignment with the SOSA™ Technical Standard and VITA 62.0

> Delivers over 400 watts of DC power via two outputs

> 90% typical efficiency

> Features cutting-edge Tier 3 software

> System management integration via VITA 46.11 compatible IPMC

By Ken Devine

GPS remains one of history’s great technological feats, but its signals are vulnerable. Although the U.S. military is taking steps to deploy M-code and modernize the constellation – which could take years to decades – even a hardened GPS signal is vulnerable to the satellite itself being shot out of the sky. Warfighters and operators need to leverage resilient positioning, navigation, and timing (PNT) today, not a decade from now. The answer to this dilemma might be right under our feet in the form of magnetic navigation (magnav).

In September 2025, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen’s aircraft circled over Bulgaria for nearly an hour after losing GNSS navigation, due to suspected Russian jamming. NATO Secretary-General Mark Rutte said that the interference was part of a complex campaign by Russia against Europe; however, Bulgarian officials said they will not investigate because this kind of GPS jamming is now so common.

Such interference is no longer an anomaly. Across Eastern Europe and the Middle East, state actors increasingly use electronic warfare to deny satellite navigation, threatening flight safety and mission continuity. Other examples: In January 2025, Germany’s top military commander, Gen.

Carsten Breuer, said his plane was targeted by Russian GPS jamming attacks; in another, in April 2025, Iran launched a concerted electronic warfare (EW) campaign across the Persian Gulf and the Strait of Hormuz, targeting U.S. military aircraft and maritime operations with aggressive GPS and communications jamming.

How it works – why it’s different

Everywhere on Earth has a distinct magnetic signature – call it a geological fingerprint – that magnetic navigation (magnav) systems can use to find their position. Using highly sensitive magnetometers and sophisticated artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms, magnav systems compare the acquired signals against existing magnetic anomaly maps to determine an aircraft’s position with a high degree of accuracy –without any external signals. When paired with GPS, inertial navigation, and/or visionbased systems, magnav enables unmatched redundancy, especially where satellite signals are degraded or denied.

In modern aircraft, inertial reference units (IRUs) normally maintain positional accuracy by receiving periodic updates from GPS or GNSS systems. When GPS is jammed, IRUs drift; when spoofed, IRU updates can’t be trusted – both of which compromise mission safety and success. During such interference events, magnav can provide

positional updates to IRUs, ensuring that they maintain navigational accuracy and trustworthiness.

Key magnav attributes include:

› Unjammable and unspoofable: Cannot be disrupted by electronic warfare or hostile interference.

› All-weather: Functions regardless of clouds, precipitation, or visibility.

› Terrain-agnostic: Operates over mountains, oceans, deserts, or urban environments.

› Passive technology: Emits no signals, making it undetectable and immune to detection-based targeting.

Proving it in the air: real-world flight results

Before magnav can be entrusted to navigate aircraft, it must be thoroughly tested and meet global industry standards. In 2023, the U.S. Air Force (USAF) Air Mobility Command (AMC) completed magnav flight tests during two major operations: Exercise Golden Phoenix (May 2023) and Exercise Mobility Guardian (August 2023). A year later, AMC tested magnav’s generalizability and potential to act as a primary, real-time navigation source. For the first time, pilots used magnav to acquire their position and navigate to designated coordinates without GPS. Of the five segments flown, three reached RNP1.0 – i.e., Required Navigation Performance, accurate to within one nautical mile.

NATO has also taken a great interest in magnav, inviting several companies (including SandboxAQ) to participate in the 2025 Defence Innovation Accelerator for the North Atlantic (DIANA) cohort as part of the Sensing & Surveillance group. Other U.S.-allied governments are testing magnav systems for both aviation, maritime, and land use cases.

For example, the USAF’s tests have focused on long-haul, crewed operations but could be expanded to other airframes to provide safe, fuel-efficient navigation in degraded environments. Similarly, it could be expanded to autonomous platforms, extending their operational reach and improving their survivability and chance of operational success. Maritime operations are also a prime use-case,

supplementing GNSS to improve blue water and littoral navigation and reduce risk for ships, submarines, or uncrewed surface vehicles (USVs).

Known limitations and engineering considerations

While magnav shows promise, like any system it has certain challenges that need to be addressed. For example, magnav systems must be properly calibrated for each specific vehicle type and/or variant. The physical structure and onboard electronics of modern aircraft, ships, or other vehicles – as well as external magnetic noise from other sources – can potentially skew measurements. Designing AI algorithms specifically for denoising both local and external distortions and enhancing signal clarity can help maintain navigational accuracy. Once calibrated, magnav systems can conceivably scale across large numbers of similar vehicles.

To further validate magnav’s accuracy, Acubed (the Silicon Valley innovation center of Airbus) completed a five-month, nationwide test with SandboxAQ’s AQNav designed to mirror real-world flight conditions. Throughout 101 sorties and 44,000-plus km (27,340 miles) flown, AQNav maintained RNP 2.0 (the standard for en route travel) 100% of total flight time, RNP 1.0 (the standard for commercial airport approaches) 95% of flight time, and RNP 0.3 (the standard for commercial airport landings) 64% of the time.

Operational concepts

AQNav can be used as part of a multisensor, system-of-systems architecture including inertial, visual, celestial, and magnetic navigation. Its successful tests with both military and civilian partners indicate the technology’s readiness for additional testing across an expanded range of platforms, operational scenarios, and mission parameters for enhanced mission assurance under GPS-denied or degraded conditions.

GPS vulnerability: What government and industry must do

The U.S. government deserves credit for recognizing the GPS vulnerability challenge early and funding complementary PNT solutions. Program managers across the services are already including multi-sensor fusion in requirements and sponsoring field demonstrations – important steps that show clear commitment and leadership under significant constraints.

However, the frequency and sophistication of jamming and spoofing continue to accelerate, outpacing even well-executed programs. To close that gap, industry and government must work to scale and accelerate complementary PNT investments, building on the groundwork already laid; translate field demonstrations and sensor-fusion requirements into operational deployments faster, ensuring that forces see tangible benefits in-theater; and broaden collaboration across services, agencies, and industry, sharing lessons learned to maximize impact.

GPS is indispensable for military operations, but redundancy is needed for mission assurance. For now, magnetic navigation is not a replacement for GPS but rather a critical complement to existing systems. As technologies, weapons systems, adversarial tactics, and the threat landscape evolves, magnav systems could take more of a leading role in delivering accurate and precise navigation. By prioritizing multisensor PNT resilience now, governments and their military leaders can ensure their forces stay on course even when GPS goes dark. MES

Ken Devine is the Product Manager, Quantum Navigation at SandboxAQ. He has a background in space operations, product management, and entrepreneurship. His contributions include managing satellite assembly, integration, and test for GPS III satellites; directing cloud-based product teams; and founding a SaaS company.

Sandbox AQ https://www.sandboxaq.com/

By Sean Gorman

The wars in Ukraine and the Middle East have turned the invisible battlespace of the radio spectrum into a front-line theater. GPS interference has evolved from isolated, tactical events into a persistent component of modern electronic warfare (EW), targeting navigation systems at every altitude and across every domain. For the U.S. and its allies, this is not a hypothetical concern or a future problem. It is a real-time operational reality, one that has exposed the fragility of GPS in ways decades of modeling never could. While there is no single substitute for GPS, there is a path to make it resilient, aware, and self-healing –this is the path to assured PNT in the contested battlespace of the 2020s and beyond.

Russia’s sustained GPS-denial campaigns across Eastern Europe, widespread interference across Israel and Gaza, and Iran’s periodic spoofing operations in the Persian Gulf have shown how quickly and effectively GPS can be degraded in modern conflict. In each case, the attacks have not been static; they have evolved dynamically in response to countermeasures, forming an iterative loop between offense and defense.

In this new environment, assured position, navigation, and timing (PNT) is not just about maintaining accuracy, but about maintaining awareness. The U.S. military cannot protect what it cannot

see. Understanding, mapping, and adapting to GPS interference in contested environments has become a mission-critical capability for every service branch and every platform.

In Ukraine, GPS denial has moved beyond isolated disruptions to what is now an industrial-scale part of modern warfare. Russian forces use layered jamming systems that range from small, tactical units meant to blind drones to powerful, wideband systems that can block satellite navigation across hundreds of kilometers.

In partnership with the Separate Service of UAV of the Ukrainian Volunteer Army, Zephr conducted extensive field tests to study Russia’s GPS interference operations under active combat conditions. These tests enabled collection of real-world data on how electronic attacks manifest in the field. The team deployed Android smartphones on static sites, vehicles, and drones to collect GNSS measurements, each running Zephr’s networked GNSS technology, which turns ordinary mobile devices into a distributed, high-fidelity sensing layer. Testing took place on the front lines near Donetsk

and in other regions such as Odessa, where controlled experiments were carried out using Ukrainian jammers.

This field research shows that many GNSS interference detection and localization techniques, though well-established in academic literature, often fail under real-world battlefield conditions involving wideband jammers. Since no modulated signals are present to tune by a receiver, methods like time-difference-of-arrival (TDoA) require large, specialized networks of time-synchronized high-end correlators, operating at high data rates, which are expensive and impractical to deploy in a battlefield setting. In Ukraine, for instance, Russian systems often continuously saturate the full GPS L1/L2/ L5 frequency ranges simultaneously and with uncorrelated noise, a tactic that disrupts all nearby GPS receivers. Even outside direct combat zones, lower-grade jammers can overwhelm conventional monitoring systems because of limited sensor coverage and technical constraints. The result is low-fidelity data and large blind spots, or “areas of effect,” where GPS disruption is happening but not being mapped in real time.

The findings show that Russia’s jamming in the field is broadband, powerful, and unpredictable. In several tests, the phones detected so-called ghost satellites – signals that appeared to come from satellites below the horizon. These false signals, often mistaken for spoofing, occur when wideband or pseudo-random noise (PRN) patterned interference overwhelms standard receivers. The result is confusion rather than deception, as the receiver’s navigation becomes erratic or collapses, rather than being lured to a false position.

This distinction matters for operations. When a drone or vehicle loses GPS because of jamming, it doesn’t just drift: it can crash, lose communication, or misreport its position. Understanding how that failure happens is key to developing countermeasures that can detect interference early and preserve partial functionality.

Altitude also proved to be a critical factor. In side-by-side tests, airborne receivers lost GPS fixes completely, while ground-based phones kept intermittent locks. This finding aligns with battlefield reports that drones are more vulnerable to saturation jamming, while forces and vehicles on the ground sometimes retain enough signal to navigate. For commanders, GPS reliability can shift dramatically within a few hundred feet of altitude, which is a critical factor for unmanned and air defense operations.

Across multiple test runs, jammed receivers showed sharp fluctuations in signal strength and noise, while static receivers farther away remained stable. These telltale patterns confirm that modern jammers are highly directional and terrain-sensitive, producing interference “hot zones” that follow valleys, ridgelines, or urban structures.

The overall lesson is clear: GPS denial on today’s battlefield is dynamic and adaptive, not static or uniform. Its impact shifts with terrain, altitude, and geometry to form irregular “volumes of denial” rather than simple circular bubbles. Clear-sky assets like aircraft and drones often suffer the worst degradation, while lower or shielded platforms may still operate, albeit with degraded precision. (Figure 1.)

For military planners and engineers, that reality demands a new approach, one that is built on real-time detection, mapping, and adaptive mitigation. GPS denial is no longer just a threat to navigation; it is an evolving part of the electronic order of battle.

The next flashpoints: Asia and the Middle East

While Ukraine remains the most heavily documented environment for GPS denial, similar trends are emerging elsewhere.

In the Taiwan Strait and the broader Indo-Pacific region, Chinese forces routinely conduct gray-zone electronic warfare (EW) operations that test and map allied responses. Commercial airliners have reported intermittent navigation anomalies along key flight routes near Taiwan and the South China Sea. Firsthand reports assert that Chinese jamming is active throughout the Taiwan Strait, yet much of it remains invisible to

Figure 1 | During field testing, networked GNSS technology was installed on phones, and data was collected both in controlled jamming environments with a friendly jammer and in an adversarial environment close to the front lines on drones, in vehicles, and on foot. Image courtesy Zephr.xyz.

outage maps that rely on internationally used ADS-B data. This invisibility occurs because many of these systems employ low-angle, terrain-shielded jammers designed to evade detection from aviation and orbital sensors. The result is an incomplete operational picture of interference activity in one of the world’s most strategically sensitive air corridors.

In the Middle East, GNSS spoofing is now a routine defense tactic used to shield critical infrastructure and mislead UAVs and GNSS-guided missiles. Israeli systems often employ proactive spoofing to obscure sensitive sites, while Iranian and proxy forces use similar methods to disrupt drone navigation. The result is a battlespace where legitimate and deceptive interference frequently overlap, complicating attribution and response. In a separate analysis, emerging “push spoofing” activity was documented in Haifa, Israel, where GNSS receivers were gradually displaced offshore rather than teleported to a fixed airport location. Unlike conventional spoofing, which is designed to trigger drone no-fly restrictions by faking airport coordinates, this new technique appears intended to manipulate flight paths or guidance systems in real time, signaling an evolution in EW tactics.

Collectively, these theaters illustrate that GPS denial is no longer an episodic threat. It is a constant feature of modern warfare and a controllable variable in every commander’s electronic order of battle.

The U.S. challenge: operating blind in the spectrum Despite decades of warnings, the U.S. still lacks a fully integrated, high-resolution

system for detecting and mapping GPS interference in real time. Current detection relies primarily on a mix of satellite sensors, ADS-B reporting from aircraft, and localized ground receivers near major installations. This approach leaves enormous blind spots, particularly at low altitudes, where most tactical operations occur.

Many of the strongest jammers in Ukraine operate below the detection threshold of ADS-B-based systems because they are terrain-masked or configured for low-angle propagation. From a high-altitude sensor’s perspective, these jammers simply disappear.

Without comprehensive domain awareness, military operators face two simultaneous challenges: First, they cannot precisely characterize where and how interference occurs; and second, they cannot localize the emitters fast enough to target or avoid them.

The U.S. needs a persistent, automated means of detecting and localizing GPS jamming and spoofing that integrates space, air, and ground sensors with edge devices operating in the field.

Lessons from the field: toward a distributed detection grid

One of the most promising approaches is also one of the simplest: Use the assets already deployed in the battlespace as sensors.

Modern handhelds are equipped with GNSS receivers capable of capturing the raw observables needed to detect anomalies. When these measurements are networked and aggregated securely, or even intermittently, they can be fused to produce realtime interference maps with far greater resolution than any fixed infrastructure.

During Zephr’s testing under an Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL) program (which includes field testing in Ukraine as well as multiple U.S. military exercises), mobile devices are configured to detect and classify GNSS jamming and spoofing while estimating the area of effect for each event and geolocating emitters in the field. This testing shows how rapidly and granularly interference can be mapped when devices collaborate across a broad region and different altitude layers.

This type of distributed detection offers a scalable path forward. By treating every fielded device as a potential sensor, the military can create an adaptive mesh network for PNT situational awareness. The data doesn’t need to stream continuously; even sporadic uploads can feed central fusion engines that alert operators when anomalies exceed threshold levels.

Ultimately, this model transforms interference from an unseen hazard into an observable variable, which is the first step toward true EW domain awareness for GPS.

At the same time, the U.S. military is investing in alternative positioning, navigation, and timing (AltPNT) technologies. These range from inertial systems and signals of opportunity to terrestrial radio networks, low Earth orbit (LEO) satellite constellations, and quantum sensors. Each contributes valuable redundancy, but none is a turnkey replacement for GPS.

› Inertial navigation systems (INS): INS remains the most reliable short-term backup for GPS, particularly when tightly coupled with PNT filters. However, even advanced ring-laser and MEMS-based systems accumulate drift without external updates. Emerging “quantum” INS technologies promise dramatic drift reductions, but they still require a known starting coordinate to function, which means they cannot bootstrap absolute position without another reference.

› eLORAN: Long-range terrestrial radio systems like eLORAN offer resilience against jamming due to high signal power and low frequency, but they are

infrastructure-intensive and regionally constrained. They also provide only lateral positioning, not altitude, which limits their standalone utility for air operations.

› LEO PNT constellations: Commercial satellite providers are developing LEO constellations that can deliver faster, stronger signals and lower latency. However, because LEO satellites move rapidly, global coverage requires hundreds of spacecraft, extensive ground infrastructure, and constant handoffs. While these constellations will improve redundancy, they still rely on ground-control links and are vulnerable to electronic and kinetic attack, making them a complementary (not a replacement) layer for military PNT.

› Terrain and Visual Navigation: For aircraft and autonomous systems, terrain-referenced navigation (TRN) and vision-based systems provide valuable drift correction when GPS is degraded. However, both depend on stable, premapped environments. In rapidly changing combat zones –or in regions obscured by dust, smoke, or debris – these systems can degrade or fail altogether.

The takeaway is clear: There is no silver bullet. Every AltPNT option offers situational value, but each carries environmental, operational, or logistical constraints. Resilience will come from combining them intelligently and knowing when to trust each layer.

A layered PNT architecture recognizes that every method of determining position or time has a failure mode, and that those failures can often be compensated by cross-referencing others.

The core principle is graceful degradation: as interference increases, the system dynamically shifts its weighting among available inputs. A distributed, ground-based network of mobile receivers provides early warning of interference, creating the first layer of situational awareness. When GPS confidence drops, INS and visual systems carry

more load; when those drift, terrestrial or cooperative positioning adds correction; and when all degrade, the system communicates its uncertainty clearly to operators and higher-level networks.

For embedded systems, the challenge is less about hardware and more about software adaptability. Filters must be able to reconfigure in real time, ingest external cues such as interference maps, and adjust behavior based on context. Modern data architectures, including edge-based artificial intelligence (AI) and secure cloud synchronization, make these goals increasingly achievable even in constrained environments.

In practice, a layered approach also means fusing domain awareness with navigation itself. A warfighter’s device should not just display a coordinate; it should communicate confidence and show why that confidence has changed.

When operators can see the electromagnetic battlespace as clearly as the physical one, they can adapt tactics accordingly, choosing alternate routes, timing operations around interference cycles, or directing fires to suppress emitters.

Building true EW domain awareness

Electronic warfare domain awareness must go beyond detecting interference to transforming signal disruptions into actionable intelligence. A comprehensive architecture would integrate multiple layers of sensing and analysis:

› Space-based assets to observe large-scale jamming and track persistent interference patterns.

› Airborne platforms (manned and unmanned) to fill mid-altitude gaps and provide angular diversity.

› Ground and mobile sensors to capture localized signal degradation, spoofing patterns, terrain effects, and geolocation of emitters.

› Edge analytics on tactical devices to identify anomalies in real time, even under degraded connectivity.

› Central fusion services to combine these inputs into live maps of interference intensity, confidence, and probable source location.

Such a framework would allow commanders and engineers to understand not just where GPS is being denied, but why, how, and by whom. It would also enable faster countermeasures, from rerouting assets to retasking sensors or targeting emitters.

Developing this capability requires close collaboration between the services, research agencies like AFRL, and private industry.

Engineering for the contested spectrum

For system designers, integrating EW domain awareness and layered PNT into embedded platforms presents several practical challenges:

› Access to raw GNSS data: Many receivers abstract or discard observables needed for interference detection. Future designs must expose this data securely to onboard software layers.

› Computation at the edge: Embedded processors must run lightweight detection algorithms without compromising mission software. Efficient, hardware-agnostic implementations are key.

› Intermittent connectivity: Systems should queue and forward interference data opportunistically, maintaining function even when disconnected.

› Latency and synchronization: Shared PNT and EW data must remain time-aligned to enable triangulation and emitter attribution.

› Cybersecurity: Any distributed detection framework must be hardened against spoofed reports and hostile data injection.

Together, these challenges highlight the need for common PNT interfaces and modular architectures that can evolve with the threat environment.

The way forward

The wars of the past three years have made one fact unavoidable: GPS is no longer assured by default. Every contested environment – whether in Europe, the Pacific, or the Middle East – now features deliberate, adaptive attempts to deny or deceive satellite navigation.

The U.S. cannot afford to be reactive. We must evolve from viewing GPS as a standalone service to treating it as part of an integrated, adaptive PNT ecosystem. That ecosystem will blend global satellite signals with regional terrestrial aids, cooperative mobile sensing, open environmental corrections, and continuous EW domain awareness.

Field data from ongoing programs, including those supported by AFRL, demonstrate that evolution is achievable using existing hardware and modern software architectures. By transforming every device into both a user and a sensor of PNT, the military can build a resilient foundation for operations in any spectrum environment. MES

Sean Gorman, Ph.D. is the CEO and co-founder of Zephr.xyz, a developer of next-gen precision positioning and AI navigation agents. Gorman has a more than 20-year background as a researcher, entrepreneur, academic, and subject-matter expert in the field of geospatial data science and its national-security implications. He is the former engineering manager for Snap’s Map team, former chief strategist for ESRI’s DC Development Center, founder of Pixel8earth, GeoIQ, and Timbr.io, and held other senior positions at Maxar and iXOL. Gorman served as a subject-matter expert for the DHS Critical Infrastructure Task Force and Homeland Security Advisory Council, and holds eight patents. He is also a former research professor at George Mason University.

Zephr.xyz • https://zephr.xyz/

Military power supplies

By Dan Taylor

Military power systems are changing dramatically as defense platforms pack more capability into the same physical space. From artificial intelligence (AI)-driven threat detection and directed-energy weapons to swarms of autonomous drones and electric aircraft, today’s battlefield needs power in amounts that would have seemed improbable just a decade ago. At the same time, the battlefield itself is evolving: Military units are spreading across vast areas to avoid detection, which creates new challenges in getting energy to where it’s needed most. The question facing military power system designers is no longer just how to generate more power, but how to deliver it efficiently and rapidly to forces that are increasingly mobile and spread out.

The explosive growth of power-hungry technologies like artificial intelligence (AI) and electronic warfare (EW) systems is one major driver of the need for more power everywhere in the battlespace. Supporting both traditional platforms and new capabilities like uncrewed systems, places complex demands on military power system designers. Add to this the reality that many military platforms operate for decades, and the challenge becomes clear: Engineers must find ways to triple power output without changing the physical size of equipment, all while meeting strict military standards for efficiency, reliability, and survival in harsh conditions.

The defense industry’s response combines new technologies with entirely new approaches to power delivery. Advanced semiconductors, smart power conversion, improved battery designs, and mobile energy systems are transforming how military forces generate, store, and distribute electricity. Perhaps most significantly,

power is evolving from a fixed support function into a tactical tool that moves with the warfighter, adapts to changing conditions, and enables mission success in contested environments where every technological advantage matters.

More power, please

One clear indication of how today’s battlefield is putting a major strain on power systems is the sheer number of platforms that need power: Electric vehicles, drones, broadband connectivity, and electric vertical takeoff and landing (eVTOL) aircraft all need substantial amounts of power.

Ron Gaw, president of Aegis Power Systems (Murphy, NC), notes “today’s military platforms are beginning to mirror the increasing power demands seen in the commercial and consumer industry, though the mission is fine-tuned to support critical energy for AI target identification, tracking, and instantaneous battlefield intelligence needs.”

The problem gets worse when you consider that many military platforms weren’t designed for these power levels. Matt Renola, senior director of global business development for aerospace and defense at Vicor Corporation (Andover, Massachusetts), explains the bind engineers face: “A lot of times the form factor is not changing. The power levels have tripled, but they’re not giving us any more room to work with.”

Increased power levels creates a heatmanagement problem. “Any time you’re putting more power in the same envelope, you have to deal with heat,” Renola says.

Even highly efficient converters – those operating at 96.5% efficiency – still need to dissipate the remaining energy as heat, and it has to go somewhere.

The way military units now operate adds another layer of complexity: Units are dispersing across vast areas to avoid detection, which improves survivability but creates supply chain issues and power delivery problems.

Communication limitations make edge computing essential, which in turn drives up power requirements on individual platforms.

“One of the biggest issues we have right now is the limited amount of communication you can have between platforms,” says Scott Lee, senior director of sales and business development for defense, aerospace, and satellite solutions at Vicor. “And because of that, there’s a lot more of an effort to put the processing horsepower, particularly married to AI, on the individual platform.”

Operating in harsh or hostile environments also creates challenges for power designs. Gaw says that “while most aspects of power systems that are critical in contested environments have not changed (e.g., rugged structures and clean power), other aspects are going to take center stage at a much higher priority.”

• MIL/COTS/Industrial Models

• Regulated/Isolated/Adjustable Programmable Standard Models • New High Input Voltages to 1,200VDC • AS9100D Facility/US Manufactured

• Military Upgrades and Custom Modules

• Ultra Miniature Component Packages

• MIL-PRF-27/MIL-STD-1553

• QPL Approved Manufacturer

• Transformers - Audio/Pulse/ Power/Data-Bus

• Common Mode Chokes & Power Inductors

• Critical Applications for Space, Flight, & Communications

Chief among these priorities is efficiency. “Conversion efficiency will be one of the most critical, as this will directly impact the mission length, capability and logistical support demands,” he adds.

Better efficiency does more than extend runtime: “It will also lead to lower cooling demands in critical systems, which means the parent systems themselves will see lower weight, package volume, and energy usage,” Gaw notes.

Thermal management remains a persistent concern, especially in sealed enclosures.

"A lot of these systems are boxes – these are sealed boxes with no moving air," Renola says, adding that even with a highly efficient 1,000-watt DC-to-DC converter operating at 96.5% efficiency, “you still have got to dissipate that heat. It's got to go

Figure 1 | Vicor’s SOSA Power Supply is a commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) device designed for 3U OpenVPX systems that are aligned to the SOSA approach. It is targeted at avionics, shipboard applications, and other defense applications. Image via Vicor.

Figure 2 | The Aegis Power Systems AP31F44017K5M is an AC-DC power converter for rackmount applications with 440VAC input, 375VDC output, and 11 kW power output. It features high efficiency, smart controls, and U.S. sourcing. Image via Aegis Power Systems.

somewhere.” Vicor has worked on solutions that involve fluid cooling and new thermal design techniques. (Figure 1.)

Gaw notes that power system designers face multiple simultaneous requirements: adaptability to a wide range of input power sources; the capability to output higher voltages and lower current as enablers for lighter overall systems; packaging the power conversion product itself in increasingly smaller, more mobile, and faster assets; and providing real-time response to changing power demand and power conversion input/output telemetry. (Figure 2.)

Designers of military power supplies are leveraging wide bandgap semiconductors such as gallium nitride (GaN) and silicon carbide (SiC) to overcome these challenges, Renola says. “We see a lot of wide bandgap semiconductor use in the aerospace and defense market now. [They] offer higher power density, much higher frequency, lower conduction, and lower switching loss.”

The payoff goes beyond just performance specs. “The advances in all these technologies allow us to scale with the customer, to keep that same 25- to 30-year old airframe or whatever running with more advanced technologies,” he explains.

But it’s not just the technology itself –modularity and scalability are also becoming essential design principles.

The next wave Aegis’s Gaw highlights two particularly important developments that are impacting future designs. “Intelligent power conversion that self-reports [will provide] critical operational information securely, stealthily, and in real time to enhance warrior asset awareness, reduce combat cognitive load, and enable future system assets’ awareness capabilities,” he said. The second area to watch, he believes is “technologies that will provide high-efficiency, low-signature power transfer with increased stealthy deployment options to extend unmanned mission range and capabilities.”

For its part, energy storage is evolving rapidly. “There are new battery chemistries coming out,” Renola says. “Energy storage is also one of these areas that we’re starting to see a lot of attention paid to with lithium, lithium polymer, and different types of chemistries to allow more power to be stored and held and to be used at the appropriate time.”

Higher-voltage architectures are also on the horizon; Renola notes that he’s seeing more requests for 800-volt DC systems.

Space applications are emerging as a priority. Renola says the company is talking a lot more with customers about satellite applications: “I think over the next 25 to 30 years, that’s going to be much more important than it is today.”

Power redundancy and resilience are becoming essential as threats evolve.

“The definition of ‘battlefield’ is evolving quickly, where the first wave of an aggressor’s attacks may very well be digital

attacks on energy sources and of a scale not seen before,” Gaw says. “Power resiliency won’t be enough – redundancy will be a critical factor in ensuring all U.S. assets remain connected with full battlefield physical and digital capability intact.”

This evolution requires more than just hardened equipment.

“That doesn’t just mean rugged enclosures and electrical resilience; it means the capability to rapidly deploy power to anywhere, from any source to other more critical sources,” Gaw explains.

“It also means every asset is able to step in and contribute to the continuation of the mission, while delivering the mobility and stealth capabilities our warriors and their mission-critical assets have not seen before.” MES

AirBorn’s VPX Power Module is a VITA 62, Open VPX compliant, 6U system with models for a 270 VDC input IAW MIL-STD-704.

Auxiliary DC Output: +3.3V/60A

Peak Efficiency of 95%

Input-Output Isolation 2100VDC

Main DC Output: +12V/180A

Overvoltage, Overload, & Overtemperature Protection

Programmable Regulated Current Limit

VITA 46.11 System Management

By Sanjeev Sachan

The U.S. military is investing in several innovative “more-electric” aircraft concepts as a means of delivering platforms with enhanced efficiency, reduced weight, and lower operating costs. The more-electric concept refers to the use of electric power for an aircraft’s nonpropulsive systems, with attendant increases in the power-generation, power electronics, fault-tolerant architecture, flight-control, and conversion systems.

In early 2025, the U.S. Air Force awarded a grant to ZeroAvia to conduct a feasibility study focused on a hydrogen-

electric aircraft alongside advanced autonomous technology. ZeroAvia was tasked with analyzing the potential for developing and delivering an 8,000-pound autonomous aircraft with hydrogen-electric propulsion for reduced engine noise and low thermal signature, both of which would considerably reduce the aircraft’s detectability.

This investment was quickly followed by a U.S. Army Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) contract awarded to aerospace supplier Electra to advance the research and development of hybrid-electric power train, power, and propulsion systems. Under this contract, Electra will conduct a comprehensive series of technologymaturation and risk-reduction activities for hybrid-electric propulsion related to its EL9, a nine-passenger ultra-short takeoff and landing aircraft currently in development. The work is aimed at delivering valuable insights and test data to help the Army understand the benefits, tradeoffs, and operational procedures associated with operating hybrid-electric propulsion systems.

The two projects are illustrative of broader interest in the concept of the more electric aircraft (MEA), both in the U.S. and further afield. Much research and development effort is being spent looking at how traditional hydraulic and pneumatic systems can be replaced with electric alternatives, resulting in enhanced efficiency, reduced weight, improved stealthiness, and lower operating costs. The all-electric aircraft (AEA) for military service might be some way off, but significant progress is being made in developing hybrid-electric and fully electric options, representing an exciting period of opportunity and change.

As the efficiency and safety of modern aviation systems rely increasingly on electronic systems, the opportunities –and responsibilities – for design engi neers are expanding rapidly. The drive for efficiency and weight savings demands a bold approach to avionics, requiring systems architects to make cru cial platform-level decisions. Is it feasible to eliminate hydraulics and pneumatics from the aircraft? What about the power distribution strategy – is the supply chain mature enough to support a wholesale migration to higher voltages?

Aviation system designers must continu ally focus on efficiency optimization and maximizing power usage. Energy management is critical, demanding a total life cycle approach when developing intelligent power systems. Additionally, with safety paramount in aviation, designers must be reliability champions, insisting on step-change improvements in an electrical system’s performance over current capabilities. Perhaps most importantly, the role of the integration specialist is essential to the seamless operation of multiple complex aircraft systems.

and methodologies, with size, weight, power, and cost (SWaP-C) minimization criteria at the core. Modular architectures enable technology to be reused and scaled efficiently across different platforms, which reduces both cost and development time. Advanced intelligent energy-management systems are key enablers of efficiency, ensuring the effective harvesting and redistribution of power.

Rigorous systems-integration methodologies combine various subsystems into a cohesive whole, improving interoperability while enhancing performance, reducing costs, and improving overall functionality and safety. Future-proofing designs ensures that platforms retain flexibility as regulations and technologies evolve, while whole-life cycle thinking considers the impact of design decisions on manufacturing and operation through to end-of-life management.

Within this challenging context, aviation designers in military environments must balance visionary ambition with proven engineering design principles

Go from development to deployment with the same backplane and integrated plug-in card payload set aligned to SOSATM and CMOSS. Includes chassis management, power and rugged enclosure for EO/IR, EW, SIGINT and C5ISR applications.

The growing investment in hybrid-electric propulsion vividly illustrates many of these principles. Modular architectures, for example, enable engineers to trial hybrid powertrains on smaller aircraft before scaling up to larger platforms. These hybrid systems offer an immediate opportunity to demonstrate how scalability and practicality can coexist in real-world military applications.

Components and enablers of MEA design Fundamentally, aviation systems rely on a core set of electrical technologies for power generation, distribution, and management, as well as for powering avionics and other critical systems.

Electrical power-conversion systems are widely recognized as a cornerstone of a more electric future. These systems – as fundamental enablers of the MEA concept –

efficiently distribute and manage electrical power, converting between different forms (AC and DC) and voltage levels to meet the diverse needs of the various onboard systems. Highefficiency converters using silicon carbide (SiC), and gallium nitride (GaN) are enabling smaller, lighter, and more efficient systems that drastically reduce power losses.

Bidirectional power systems in modern aircraft unlock new approaches to energy recovery. Unlike traditional unidirectional power supplies, which only deliver power, these systems can both supply power to a load and absorb power from it, enabling the transfer of electrical energy in both directions. Bidirectional power systems are crucial for various applications, including energy storage. Excess power from motors or subsystems during low-demand phases can be fed back into batteries or other loads, for example, improving operational efficiency and directly supporting the wider trend towards electrified propulsion.

Smart sensing networks monitor various operational aspects of an aircraft in real time, enabling systems to be dynamically optimized, improving efficiency, extending component life, and reducing unplanned downtime. Smart sensors are typically used for structural health monitoring (SHM), environmental monitoring, and engine health monitoring. Sensor technologies are emerging that monitor pilot alertness to boost safety and mission performance. Sensor types include fiber optic, piezoelectric, guided wave, and current sensors, with microelectromechanical systems (MEMS) sensors increasingly used due to their miniaturization levels, reduced cost, and enhanced performance. Both wireless and wired sensor networks are deployed, depending on the specific application and location within the aircraft.

Battery integration plays a crucial role in MEA

Battery integration is key to more efficient aviation performance. Batteries play a crucial role in the MEA, beyond just engine starting and backup. At the

heart of an integrated energy-management system, they provide power for various systems and are central to peak load balancing and energy recovery; they also support propulsion in hybrid or fully electric designs. Lithium-ion batteries currently dominate due to their relatively high energy density and established manufacturing infrastructure, but solid-state batteries are seen as a promising next-generation technology, with the potential of even higher energy density and enhanced safety.

High-voltage (HV) distribution is critical, too. As the trend towards MEA drives an increase in the number of electrical components and systems, the need for interconnectivity grows. With electrical wiring harnesses currently representing anything between 1% to 3% of the aircraft’s empty weight, manufacturers are considering replacing or complementing traditional AC systems with HV DC systems. Higher voltage levels require less current for the same power transmission, leading to smaller and lighter wiring harnesses, and hence significant weight savings for next-generation military aircraft. Today’s platforms typically use 270 volts or 540 volts, but higher voltages such as 800 volts or even 1200 volts are being explored. Ultimately, distribution levels of several kilovolts will be required to support the power requirements of future platforms such as electric propulsion.

In conclusion, the U.S. military continues to fund innovative research and development projects that are pushing forward the boundaries of knowledge on more electric aircraft. The trend towards MEA is seeing an increasing electrification of key aviation systems, enabled by advances in power conversion, power distribution, battery management, and sensing technologies. The all-electric aircraft for both military and civil environments may be some years away, but the roadmap towards it is based on modularity and scalability. Market success will be based on the ability to successfully test, prove, and scale architectures through successively larger aircraft structures. MES

Sanjeev Sachan is director of engineering at TT Electronics, where he leads the power supply and magnetics engineering division across North America. With over 27 years of experience in developing complex products for aerospace and defense applications, Sanjeev brings deep expertise in power management, magnetics, distribution, control, and system integration. His team specializes in designing and manufacturing high-performance power supplies for environments ranging from ground-combat vehicles to space systems and taking on such challenges as constrained footprints, thermal management, vibration, EMI, and lightning protection.

TT Electronics https://www.ttelectronics.com/

For challenging RF/microwave signal processing power or digital signal integrity requirements: it’s IMS.

WHAT Does IMS Do?

· Over 50 years of proven success

· Both thick and thin film resistors

· More power, less heat

· High-performance attenuators, couplers, terminations

· Solutions for analog and digital designs

· Modelithics® Vendor Partner

WHY Choose IMS?

· Thick and Thin Film Resistors

· Fixed and Variable Attenuators

· Thermal Management Devices

· Power Splitters and Couplers

· High Power RF Terminations

· Custom Capabilities

Open standards for embedded systems: FACE, SOSA, CMOSS, VPX, and more

The open architecture of the Gray Eagle uncrewed aircraft system (UAS) enables easy implementation of the FACE Technical Standard across control interfaces, avionics, and datalinks, and provides the ability to integrate a customizable suite of multi-INT sensors – all of which provide standoff survivability with the stand-in capability required for multidomain operations. Photo courtesy General Atomics Aeronautical Systems, Inc. (GA-ASI).

By Joe Richmond-Knight

In recent years, the accelerating pace of technological advancement in both military and civilian aviation has revolutionized avionics systems development. At the heart of this revolution is the standard known as the Future Airborne Capability Environment, or FACE, Technical Standard. In tandem with the modular open systems approach (MOSA), the FACE standard is laying the foundation for modern, open software architectures for airborne platforms. The FACE Technical Standard is not just another industry standard – instead, it represents a major departure away from monolithic, proprietary systems toward more open, modular, and reusable software components.

The Future Airborne Capability Environment, or FACE, Technical Standard was developed to help overcome ongoing challenges in integrating vendor-specific avionics systems that are difficult to maintain, resulting in high operating costs and making interoperability between systems difficult to achieve. Since 2019, U.S. law requires all major defense acquisition programs (MDAPs) to adhere to modular open systems approach (MOSA) principles and while there is no equivalent legal requirement in Europe, embedding modular procurement logic into tenders is increasingly becoming a requirement for national procurement agencies in Germany, France, and Italy. Many NATO countries are currently investigating how their own national projects can align with the FACE Technical Standard. Taken together, it is clear that MOSA has laid the strategic groundwork for open, networked, and future-proof international systems while FACE alignment will provide the concrete, verifiable software architecture implementations for technical airborne systems.

Alongside the FACE Technical Standard, the Open Mission Systems (OMS) framework and the Universal Command and Control Interface (UCI) have become established in military software architectures, while also becoming increasingly important in civilian aviation. There is no content overlap between the three standards, meaning they have the capacity to complement, rather than compete, with each other. In practice, an airborne platform can be built to be aligned with the FACE Technical Standard while also still using OMS architectures and UCI data interfaces.

Technical architecture of the FACE approach

The technical architecture of the FACE Technical Standard organizes software into five distinct segments:

› Operating System Segment (OSS)

› Transport Services Segment (TSS)

› I/O Services Segment (IOS)

› Portable Components Segment (PCS)

› Platform-Specific Services Segment (PSS)

Each component connects to the overall system through defined interfaces. For instance, OSS is a component within the FACE Technical Standard that Sysgo PikeOS can implement and ELinOS (a guest OS) can run within a FACE-compliant system.

The FACE Technical Standard defines three OSS profiles that customize operating system APIs, programming languages and features, runtimes, frameworks, and graphics capabilities to support software components with various levels of priority:

› Security: Limits OS APIs to a minimal yet functional set, enabling assessment of high-assurance security functions that run as a single process.

› Safety: Less restrictive than Security, it allows only OS APIs with a proven safety-certification pedigree.

› General Purpose: The least restrictive, supporting OS APIs for both real-time deterministic and non-real-time, nondeterministic requirements, depending on the system or subsystem operation.

The Shared Data Model also plays a central role, as it serves as the semantic foundation for all messages.

The FACE Technical Standard also uses a variety of established standards, including:

› ARINC 653 (partitioning for safety)

› ARINC 661 (cockpit displays)

› POSIX APIs (portability)

› OpenGL (graphics interfaces)

› Ada, C++, Java (programming languages)

By integrating these standards, the FACE approach becomes an interoperable platform that offers high flexibility for system integration developers. This model strongly supports typed data structures and ensures that position data, sensor readings, or status information are interpreted consistently throughout the avionics system.

Implementing the FACE approach opens up new opportunities

Implementing the FACE Technical Standard is an investment that delivers lasting value. While it requires initial technical effort, the payoff can be substantial – especially for system providers working across multiple platforms or planning long-term software product strategies. By separating platform architecture

Open standards for embedded systems: FACE, SOSA, CMOSS, VPX, and more

from functional logic, FACE alignment unlocks true reuse and modularity, enabling proven modules to be deployed across diverse projects without costly redevelopment. Standardized interfaces streamline collaboration with partners and subcontractors, accelerating integration and reducing risk. Perhaps most importantly, FACE conformance boosts market visibility, thereby positioning manufacturers to win more business by tapping into the public registry of certified modules and responding quickly to new tender opportunities.

Alignment with the FACE Technical Standard also creates new opportunities for smaller and specialized software providers that were once shut out of large system-integration projects and unable to compete with established prime contractors. Traditionally, the complexity of integrating proprietary systems acted as a barrier, but FACE alignment removes this obstacle. By clearly separating modules from overall system responsibilities, smaller companies can concentrate on delivering welldefined software functions, have them certified, and market them independently through the FACE Registry. This approach expands market access, lowers business risk, and fosters a more competitive environment – one where quality, innovation, and interface compliance matter more than entrenched customer relationships. These dynamics are especially promising in rapidly evolving fields such as artificial intelligence (AI), sensor fusion, and real-time systems.

Bury it in a factory floor. Mount it on a drilling platform. Deploy it in the Arctic. The Relio™ R1 family of computers thrive where other hardware fails. While you're solving the big problems, Relio™ handles the basics. 24/7/365 operation. Three industal computers. One promise: Set it. Forget it. Count on it.

When failure isn't an option, forgettable is unforgettable. Sealevel Relio™ Computers.

The FACE Registry is the gateway to visibility, credibility, and new business opportunities. Acting as a publicly accessible “app store” for military software components, it enables program managers, system integrators, and developers to quickly find and compare certified Units of Conformance (UoCs). Every component listed has passed a rigorous certification process, guaranteeing seamless interoperability within the FACE architecture. For manufacturers, the Registry is more than a directory – it’s a direct channel to market. Certified UoCs and UoC packages can be showcased to the entire defense ecosystem, opening doors to new programs, platform integrations, and partnerships. With its standardized registration process, the FACE Registry turns certification into competitive advantage, making it easier than ever for high-quality solutions to stand out and win.

Making FACE aligned offerings safe and secure Modern avionics systems are becoming increasingly interconnected, and the shift toward software-defined platforms has made security a critical priority. While the FACE Technical Standard is not itself a security-certification authority, it incorporated mechanisms early on to address security-critical requirements. The FACE Technical Working Group’s Security Subcommittee plays a central role in this effort, developing recommendations, security profiles, and integration patterns that enable components with differing security needs to function together within a FACE compliant system.

A key focus is multilevel security (MLS), which ensures physical or logical separation of modules with different classification levels when integrated on a shared computing platform. The FACE approach also supports the integration of domainspecific security measures, such as data encryption and access control, without compromising overall system interoperability. When combined with standardized data models, these measures deliver security that meets the highest military standards, making the FACE Technical Standard equally applicable to critical infrastructure and civilian aviation systems. From a safety perspective, the FACE approach does not replace existing standards, but rather complements them. Developers of FACE aligned safety-critical software can benefit from the use of modular architectures, isolated testing techniques, and automated verification. (Figure 1.)

Developers and architects adopting the FACE Technical Standard have access to more than just specifications and testing procedures; they benefit from a broad set of open tools, documentation, and training resources. A key resource is The Open Group-supported BALSA reference project, a minimal yet functional example environment that demonstrates how to create a simple, fully FACE confromant application. BALSA can serve as an ideal starting point for custom development, backed by comprehensive guidelines for software vendors, integrators, and project managers, along with regularly updated training programs. Delivered by the consortium or accredited partners, these courses serve both technical teams and decision-makers, covering topics from architecture modeling and data description to transport service integration and

Figure 1 | Representatives from multiple Army directorates participated in the simulated environment during the Special User Evaluation for the Future Long-Range Assault Aircraft (FLRAA) program, held during spring 2025. The program provided developers with insights into how Army aviators plan and execute tactical missions using cutting-edge technology. Photo: Morgan Pattillo, Program Executive Office, Aviation.

middleware. This knowledge base helps projects start on the right track and avoid costly missteps.

Conformance to the FACE Technical Standard, together with MOSA, is paving the way for a new generation of open, maintainable, cost-effective, and secure avionics systems. By aligning closely with laws, technical standards, and formal certification processes, it fosters a growing ecosystem that blends innovation with robust security. For stakeholders across both military and civilian aviation, the FACE approach represents a new paradigm in system development – modular, open, and built to stand the test of time. MES