Commercial Aircraft Operating Leases Economic Aspects of Utility Consumption Leases that apply Maintenance Rent

1. Introduction

Economic compensation for utility consumption of major components and airframe checks of commercial aircraft play a pivotal role in operating leases. This becomes a key factor used to determine the profitability of an aircraft leasing deal. In addition, the way utility consumption is managed or accounted for plays an important role in the risk and exposure level of lessors against unforeseen circumstances, like airline defaults and bankruptcies.

In a paper from 2020, a simple introduction to the Maintenance Reserves / Maintenance Rent (MR) concept and Maintenance Rent Rate (MR Rate) is provided. 1 A further publication of 2021 provides an explanation and overview of how utility is determined and accounted for in the case of Engine Performance Restoration (Engine PR). 2 Concepts, like Mean Time Between Removals (MTBR) and Shop Visit Costs (SV Cost), are also introduced in this paper.

It is worth mentioning that compensation for utility consumption is not always carried out by way of MRs throughout the life of the lease. In certain cases, compensation for utility consumed is billed at the end of the lease, meaning no monthly payments, just one lump sum at the end of the lease, which is what is commonly referred to as an End of Lease (EOL) payment lease.

Two types of lease agreements exist - leases with MRs and leases without MRs. Leases without MRs are usually referred to as leases with EOL compensations. Whether or not to structure a lease by way of MRs or EOL compensations is a matter that involves commercial and risk considerations that are heavily negotiated between lessees (airlines) and lessors.

Finally, compensation for utility consumed is usually applied not only to Engine PR. It is usually applied to Engine LLPs Replacement, Airframe major checks 3, APU Performance Restoration and Landing Gear Overhaul, among others. These are collectively called Major Events.

This paper will attempt to illustrate how MRs work throughout the life of a lease agreement for Engine PR. For familiarization purposes, it is recommended to become accustomed to the aforementioned paper (see Footnote 2). As the principle is the same for other Major Components, those will not be discussed in this paper. In addition, this paper will not discuss the mechanics surrounding EOL compensations either.

2. MRs Mechanism for Aircraft New at Delivery

This is the typical case when aircraft are delivered from the factory.

1 Omar Zuluaga, “Aircraft Operating Leases Maintenance Reserves - Basic Concept Explanation,” n.d., https://www.slideshare.net/OmarZuluaga1/aircraft-operating-leases-maintenance-reserves-basic-conceptexplanation/.

2 Omar Zuluaga, “Aircraft Operating Leases Engine PR MRs Basic Concept Explanation,” n.d., https://www.slideshare.net/OmarZuluaga1/aircraft-operating-leases-engine-pr-mrs-basic-conceptexplanation.

3 Checks usually occurring at six, nine or twelve years and corresponding repeats depending on the aircraft type and specific task card groupings approved practices.

Copyright © 2022 Omar Zuluaga. All rights reserved. Version 2.0 / December 2022 1 | Page UK Copyright Service. Registration No: 284749168

To illustrate how MRs work, one of the highest-costing Major Events will be used: Engine PR. For this, certain notional assumptions will be made as follows:

2.1. Notional aircraft engine that lasts on wing 20,000 flight hours (MTBR) before it must be removed to restore the performance at a specialized shop. This is usually referred to as Shop Visit (SV). The time on wing of a new engine before it needs an SV is higher compared to the time on wing after each subsequent SV.4 Nonetheless, for the sake of simplicity, it will be assumed that the MTBR is the same for every SV.

2.2. The notional cost to restore the performance of that engine is $2,000,000 (SV Cost). The cost of the first and subsequent SVs are different. This is due to differences in the works scope of each SV.5 Nonetheless, for the sake of simplicity, it will be assumed that this cost is the same for every SV.

2.3. This translates into a cost per hour of $100/flight hour (2,000,000/20,000) (MR Rate).

As the lessee uses the aircraft, the Engine PR MR Fund accrual starts. Each Major Event, as described and applicable as per the lease agreement, will accrue its own individual MR Fund. For Engine PR, flight hours (FH) performed on the engine during the preceding month are usually reported to the lessor during the first ten days of the subsequent month. The lessor will then issue an invoice corresponding to the number of FH performed on the engine times by the agreed MR Rate per the lease. This invoice usually needs to be paid before the fifteenth day of the month.

As time passes the MR Fund will build up. It is depicted by the blue line in Graph 1. The timing of the SV depends on how many FH per year the engine is used. For instance, if an engine is used 2,500 FH per year, the 20,000 FH mark will be achieved in year eight. It is expected that when the engine needs to be removed due to lack of performance and sent to a specialized shop in order to have its performance restored (SV) the money built into the MR Fund, “A” in Graph 1, will be enough to cover the SV Cost.

Graph 1

4Engine Maintenance Concepts for Financiers. Shannon Ackert, September 2011 5 Ibid.

Copyright © 2022 Omar Zuluaga. All rights reserved. Version 2.0 / December 2022 2 | Page UK Copyright Service. Registration No: 284749168

At this point, certain considerations need to be mentioned:

2.4. In real cases, the notional MR Rate of $100/FH does not stay static during the eight years of this example. As per the lease agreement, it is escalated annually by inflation and adjusted by other factors like flight length derate and areas of operation, among others. Engine derating reduces the engine takeoff and climb thrust to below the rated maximum capability6. Nonetheless, it will be assumed that the MR Rate of $100/FH stays the same during the eight-year period.

2.5. The $2 million cost used to calculate the MR Rate at lease start will change over time, at least by inflation. For the sake of simplicity and illustration purposes, it will be assumed that it stays static over time.

2.6. Stipulations about the content and scope of the SV are well-defined in lease agreements. Unless the lessee complies with the level of repair required as per the lease to make a certain SV a qualifying one to access MR Funds, lessees may not get compensated by lessors for certain not qualifying SVs, usually referred to as “Repairs.”

2.7. Spent amounts are not the same as qualifying amounts eligible for reimbursement from MR Funds. Lease agreements are quite specific about exclusions, meaning those that are not covered by MRs. Usually, mark-ups, surcharges, and handling fees, among others, are excluded from spent amounts to determine qualifying amounts (MR Claim Qualifying Amount) eligible for reimbursement while airlines make claims for reimbursement from MR Funds held by lessors. For the sake of simplicity, in the example of Graph 1, it will be assumed that the SV Cost is equal to the qualifying amount.

2.8. In theory, the level of the MR Fund in year eight when the engine will have achieved 20,000 FH (“A” in Graph 1) would be two million and that would be sufficient to pay the MR Claim Qualifying Amount mentioned in point 2.7. However, in practice, the following two cases may occur:

2.8.1. The MR Fund is not sufficient to cover the MR Claim Qualifying Amount. In general, unless otherwise stated in lease agreements, lessees need to cover such “shortfall.”

2.8.2. The MR Fund is higher than the MR Claim Qualifying Amount. In general, unless stated otherwise in lease agreements, the lessor has the right to keep that money in the MR Fund and make it available to the lessee for future SVs.

Once the engine is returned from the shop and reattached to the aircraft, FH start being accrued on the engine after the SV. MRs billing will restart alongside the MR Fund accrual.

2.9. Depending on the length of the lease and usage of the engine after the first SV, the following two cases may happen:

2.9.1. The engine may have another SV during the life of the lease. In that case, the mechanics mentioned previously (points 2.4 through 2.8) will work in the same way as described.

6 Vitaly Guzhva, Sunder Raghavan, Damon J. D’Agostino, Aircraft Leasing and Financing (Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2019), 277.

Copyright © 2022 Omar Zuluaga. All rights reserved. Version 2.0 / December 2022 3 | Page UK Copyright Service. Registration No: 284749168

2.9.2. The engine may not have another SV and it may comply with contractual return conditions. In this case, it will be assumed that the MR Fund at lease end (shown as “B” in Graph 1) is sufficient to compensate for utility consumed since the last SV (for illustration purposes, 10,000 FH.) That money stays in the MR Fund held by the lessor. In addition, that money will be used to pay for the next SV on the engine while in operation by the subsequent lessee.

2.10. Usage of the engine after the last SV before the lease ends requires a good degree of planning on the lessee’s side. This is in order to comply with contractual return conditions at the lease end. In the example of Graph 1, it is assumed that the engine will still have another 10,000 FH before its next removal and that this number of FH is sufficient to meet return conditions as per the lease agreement. A premature SV at lease end may be quite detrimental for lessees in case the MR Fund at lease end is not sufficient to cover MR Claim Qualifying Amounts (typical case as described in 2.8.1).

3. MRs Mechanism for Aircraft Used at Delivery

This is the typical case when aircraft are delivered to a subsequent lessee after being used by a first lessee since new. To illustrate how MRs work, one of the highest-costing Major Events will be used: Engine PR. For this case, the same notional assumptions and stipulations made in points 2.1 through 2.7 will be applied.

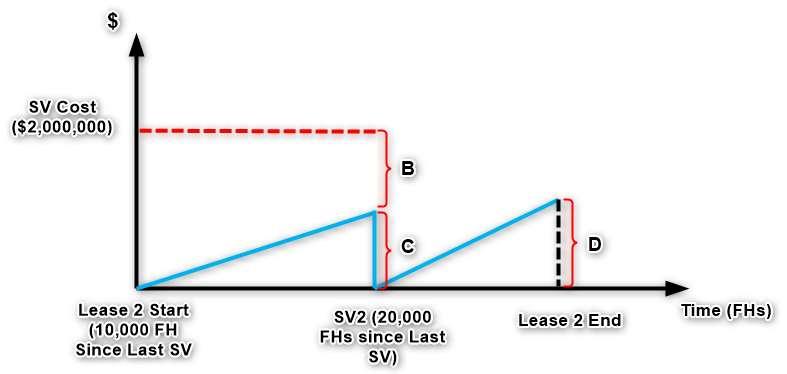

3.1. Once the aircraft is delivered and the engine starts being used, the lease 2 MR Fund accrual will start, as shown in Graph 2 and depicted by the blue line. For illustration purposes, Graph 2 shows the same engine as Graph 1 as being delivered to a subsequent lessee having 10,000 FH consumed since the last SV.

3.2. When the engine needs to be removed and sent to the shop (SV2 in Graph 2), the amount of money accrued in the MR Fund during Lease 2 (“C” in Graph 2) will most likely not be enough to cover the cost of the SV. The engine will be removed by lessee 2 once it reaches 10,000 FH of operation and the money accrued in the MR Fund of lessee 2 will be roughly half of the required MR Fund to pay the SV in full. In these instances, talk is made about a shortfall (described as “B” in Graph 2) that needs to be paid by the lessor by way of what is commonly referred to as a “lessor additional contribution” or “lessor top-up” (TopUp.)

3.3. In theory, the TopUp contribution made by a lessor towards the cost of SV2 would equate to the MR Fund left at lease end by lessee 1 (as described in point 2.9.2 above and as “B” in Graph 1.)

3.4. Lessor contributions for the previous usage are usually heavily negotiated and, in general, are a fixed amount that equates to utility consumed at delivery times the agreed MR Rate at lease start.

3.5. It is expected that amounts “B” and “C” are sufficient to cover the cost of the SV2 (MR Claim Qualifying Amount.) In general, any additional shortfalls are for the account of the lessee, unless otherwise stated in lease agreements.

3.6. At this point, the same considerations mentioned in points 2.9 and 2.10 will apply. The amount of money described as “D” in Graph 2 will serve as the TopUp for the next SV in case it is carried out by a subsequent lessee.

Copyright © 2022 Omar Zuluaga. All rights reserved. Version 2.0 / December 2022 4 | Page UK Copyright Service. Registration No: 284749168

Graph 2

4. Conclusion

MRs are a crucial part of commercial aircraft lease agreements. They allow the lessor to have the monetary equivalent of utility consumption in their accounts in case of unforeseen circumstances, like airline defaults or bankruptcies. The level of MRs and corresponding escalations of MR Rates are equally critical while negotiating lease agreements. This is in order to have the cost of SVs fully covered once SVs occur. The level of exclusions of spent amounts, in order to quantify qualifying amounts, is an equally important part of lease agreements as that determines how much money lessees will get back from MR Funds once SVs occur. Finally, dealing with shortfalls is also crucial. Negotiations of TopUps and/or additional lessor contributions play critical roles in lease agreements and their profitability. All these factors need to be well agreed upon in advance as that allows for smooth lease agreement management and a good commercial relationship between lessors and lessees.

About the Author

Omar Zuluaga is a former Vice President and Head of Technical Support at AerCap. Currently, he works as an independent advisor providing services to institutional investors, management consulting firms and corporates. He has spent seventeen years working in technical areas of the aircraft operating leasing industry. Prior to that, he worked in airline technical operations for ten years.

Omar Zuluaga holds a Bachelor of Science degree in Aviation Electronics from the Riga Civil Aviation University in Latvia (formerly RKIIGA) and a Master of Science degree in Aviation Management from Arizona State University. www.linkedin.com/in/omar-zuluaga

Copyright © 2022 Omar Zuluaga. All rights reserved. Version 2.0 / December 2022 5 | Page UK Copyright Service. Registration No: 284749168