‘The first impression was, to say the least, striking. He was a tall, well-built man with a stern countenance; in contrast to the somewhat tattered gown and mortar-board to which we were used he wore a stiff and perfect gown, black velvet coat and waistcoat, and well-groomed, striped trousers.’

An Old Millhillian recalls his first impression of John McClure in 1891

A Portrait of McClure

4 Sir John M c Clure

John McClure, his wife Mary and their three children (in order of age) Kathleen, Keith and Lilian

Letter from the Chair, Old Millhillians Club

It feels entirely appropriate in this centenary year that the Old Millhillians Club should commission and publish this tribute to Sir John David McClure, The Maker of Mill Hill. The Club was primarily responsible for providing the funding for McClure’s salary during the initial years of his tenure. Old Millhillians dominated the Court of Governors for most of his 31 years as Head. Old Millhillians shouldered the administrative and financial burdens of running the School, allowing him to devote his time to the educational and pastoral needs of the pupils. Wealthy Old Millhillians such as Herbert Marnham and Lord Winterstoke, inspired by McClure’s vision, helped finance the significant building programme that transformed and enlarged the estate so that it was able to accommodate 300 pupils, most of whom were boarders. With Arthur James Rooker Roberts, a man also of great vision, he made Belmont a reality.

Much has been written about McClure. His daughter, Kathleen Ousey, who married an Old Millhillian, wrote a special tribute ‘McClure of Mill Hill’. Other sources we have used include Roddy Braithwaite’s ‘History of Mill Hill, Strikingly Alive’, Gowen Bewsher’s ‘Nobis, the Story of the Old Millhillians Club’ and Norman Brett-James ‘History of Mill Hill 1807-1923’. The Club’s challenge in publishing this tribute has been to find an original approach to a well-documented story.

What we have set out to do is paint a holistic picture of McClure as portrayed by his interests and relationships. We didn’t want a single view of the great man but a range of perspectives, so we have cajoled specialist contributing authors to do the work: Kevin Kyle, current Director of Music at Mill Hill, has written on McClure and Music; former Chaplain the Reverend Dr Richard Warden on McClure and Religion; former Headmaster William Winfield and current Head Jane Sanchez on McClure as Leader, Head and Educationalist, and Ed Holland (McClure

2017-21) who is currently on the Officer Training programme at Sandhurst, has written on the impact of the Great War. John Hellinikakis (School 1976/ Murray 1977-81), Chair of the Old Millhillians Relations Committee, writes on McClure’s close and enduring relations with the Old Millhillian community, and I pored over 31 years of minutes of meetings of the Court of Governors! Clare Lewis (Ridgeway 1977-79) has worked as editorial consultant on the project, and Laura Turner has provided picture research assistance and vital administrative back-up. Thanks too to David Palmer for his design insights and patience.

The final bonus was discovering what we think is new (to us in any event) material. McClure contributed to the ‘Cambridge Essays in Education’, first published in 1917, edited by Arthur Christopher Benson and republished in 2015 by Creative Media Partners, Scholar’s Choice Edition. This work was selected by scholars ‘as being culturally important, and part of the knowledge base of civilisation as we know it’. We reproduce McClure’s chapter ‘Preparation for Practical Life’ in full as an Appendix.

This supplement has been a one-time opportunity for us all to take an in depth look at McClure’s talents, style, values and, above all, legacy. Each author, quite independently, has drawn uncannily similar conclusions about McClure as a person, and has found in McClure’s Mill Hill his relevance to and impact on the School we know and respect today. My thanks to all contributors for their endeavours and commitment.

His Life, Times and Legacy 5

Peter Wakeham (Burton Bank 1960-64) Chair of the Old Millhillians Club

Sir John McClure, Headmaster of Mill Hill School 1891-1922: .................................................................... page 7

An introduction by former Headmaster William Winfield

Life and Times: an historical timeline of Mill Hill School and McClure 1807-1971................................................ page 13

The Old Millhillians Club and McClure by Chair of the Old Millhillians Relations Committee, .......................... page 21 John Hellinikakis (School 1976/ Murray 1977-81)

The Court of Governors and McClure by Chair of the Old Millhillians Club, ................................................... page 27 Peter Wakeham (Burton Bank 1960-64)

Religion and McClure by former Mill Hill School Chaplain, the Reverend Dr Richard Warden ..................... page 43

Music and McClure by Mill Hill School Director of Music, Kevin Kyle............................................................... page 55

The War Years by Officer Cadet in Intermediate Term, Edward Holland (McClure 2017-21) ............................ page 65

Sports and McClure: a photographic album and sporting reminiscences from daughter Kathleen Ousey’s book ‘McClure of Mill Hill’ ............................................................................................. page 79

Education:

Walking the footsteps of a giant: William Winfield reflects on his Headmastership, McClure and Mill Hill School; A Living Legacy: current Head of Mill Hill School, Jane Sanchez shares her passion for Mill Hill School and the inspiration she finds in Sir John McClure ................................................................................................. page 83

Appendicies:

Appendix I: 1907 Centenary Appeal by John McClure.............................................................................. page 101

Appendix II: Essay on Education by John McClure....................................................................................page 105

6 Sir John M c Clure

Contents

Sir John McClure

Headmaster of Mill Hill School 1891-1922

His Life, Times and Legacy 7 An introduction to the historical context of M c Clure’s appointment and his 31-year headship

by former Headmaster (1995-2007) William Winfield

A portrait of John McClure painted by Fred Yates, was commissioned in 1912 by the Old Millhillians Club to celebrate his 21st year of Headmastership. The painting hangs on the walls of the School’s main dining room

Sir John McClure

Headmaster of Mill Hill School 1891-1922

NEWLY-APPOINTED HEADS TEND TO FACE ONE OF TWO CHALLENGES: SOMETIMES OUTGOING INCUMBENTS HAVE STEERED THEIR CRAFT WITH GREAT MASTERY BUT THE FUEL HAS BEGUN TO RUN OUT AND THE DIMINISHING BOW WAVE SUGGESTS THAT THERE IS LITTLE FORWARD MOMENTUM – SOME STOKING OF THE BOILER IS NEEDED. ALTERNATIVELY, AN UNFORESEEN STORM HAS FORCED THE SHIP ONTO THE ROCKS AND THE GOVERNORS HAVE TO PLACE ALL THEIR TRUST IN THE NEW APPOINTEE REPAIRING THE DAMAGE. IT WAS THIS LATTER KIND OF EXTREME CRISIS THAT JOHN Mc CLURE FACED WHEN HE ARRIVED AT MILL HILL IN 1891.

The second half of the 19th century was not an auspicious time for Mill Hill. A rapid turnover of four headmaster-clerics failed to keep the ship afloat between 1852 and 1868. It was difficult to recruit boys from a diminishing congregation of Protestant dissenters. Numbers had fallen steadily since Thomas Priestley (1834-52) had retired as Headmaster.

When only three boys arrived for the new school year in September 1868, the decision was taken to close the School. New capital was raised however and Mill Hill re-opened a year later with 34 entrants. The New Foundation introduced a crucial change: henceforth the School ‘shall be open to the sons of parents professing other religious tenets’. This relaxation of the Founders’ prime desire to educate sons of Congregationalists offered recruitment opportunities which the new Headmaster, Dr Weymouth (1869-86), happily exploited. Numbers rose to a peak of 70 in 1880, but then fell steadily again to just 15.

The most famous of Mill Hill’s teachers, James Murray (1873-1884 including his time as a lexicographer working in the Sciptorium) had been a crucial and ambitious player in Weymouth’s team.

When Murray left for Oxford to pursue his edit of a new English Dictionary (ultimately published in 1928 as ‘The Oxford English Dictionary’), Weymouth, now 64, collapsed under the strain and was quickly replaced by Charles Vince (1886-91), a Cambridge don who had briefly taught boys at Repton. That experience was to prove sadly insufficient and within five years the ship was again drifting dangerously off-course.

Vince’s disappointing tenure had the Governors wondering whether Mill Hill was viable and, if so, who precisely would be the man to convert the poisoned chalice into a precious vase offering a burgeoning school an undreamt-of golden era where young men would be instructed in the Faith and the Word and inspired to achieve outstanding academic success and sporting glory. The word ‘rollercoaster’ was too modern to appear in the Murray (Oxford) dictionary. Chambers however provides a helpful definition of the word’s figurative sense: ‘a series of unexpected changes of fortune or emotional swings’. ‘Rollercoaster’ neatly summarises the constant tension and excitement which have characterised much of Mill Hill’s history. The late-Victorian era was no exception, but McClure was destined to flatten those ‘Russian mountains’.

In making their new appointment, the Treasurer Thomas Urquhart Scrutton (School 1840-42) and other Governors of 1891 decided in extremis to throw caution to the wind. From the outset they made clear to everyone that the School would close ‘in the event of the utter falsification of their hopes’. Their choice of new Headmaster was bold. John David McClure was just 31 years old. He was born in Wigan, home of mills and coal mines, but also of a strong Nonconformist community which profoundly influenced his upbringing. His mother was from Kirkcudbrightshire and the McClure line went back to the Isle of Skye, suggesting Presbyterian roots. McClure spoke later of there being an element of Puritanism in his religious belief. He graduated with a London University BA in Intermediate Arts while holding an early teaching position at Hinckley Grammar School.

In 1882 he won a scholarship to Trinity College, Cambridge, where he read Mathematics. Here much of his intellectual strength was honed. He was one who had ‘a strong reverence for fact’ and ‘laid more stress on reasoning than on style’.

8

Sir John M c Clure

A view of the portico from Top Field on Foundation Day 1910

He was also highly active in the Nonconformist Union where he was regularly invited to give papers covering topics as diverse as Church Music and Recreation for the Working Classes.

After Cambridge, McClure hesitated over career direction, then headed for the Inner Temple. To be called to the Bar however required an income of at least £150 pa. He did not have it. What was more, he was now married, so needed urgently to find financial stability. Postponing his ambition to become a barrister he took on examining and lecturing for the University of London; he had only recently been appointed Professor of Astronomy at Queen’s College when Mill Hill called. Of his intellectual depth and breadth there was little doubt. But lurking in the minds of the Governors must have been that grave concern that ‘their man’ had no experience of teaching beyond those four years at Hinckley Grammar. Nonetheless the reports from Cambridge suggested that here was someone highly talented academically whose nonconformist credentials were beyond doubt. He arrived at Mill Hill in September 1891, eager to meet the fresh challenge, but also understanding that he was very much ‘on trial’.

The Governors’ courage was fully vindicated. In the end, McClure stayed for 31 years. He fulfilled his first challenge effortlessly. He was exceptionally able in recruiting new boys, increasing the numbers fivefold to well above 300 by the time of the Great War. As a result, the School needed a constant supply of new buildings to provide the necessary domestic and academic facilities. Of these the major ones were the new boarding houses Collinson and Ridgeway, but he was also the inspiration for the building of the new Chapel (the old chapel being converted into the Large), the Marnham Block, the Winterstoke Library, the Fives Courts, the Music School and, lastly, the Gate of Honour. He extended and improved the grounds, upgrading many of the fields for sport. He actively promoted the opening of Belmont in 1912 as the Mill Hill Junior School.

The centennial celebration of 1907, including the notable presence of the Prime Minister Sir Henry CampbellBannerman as guest of honour at Foundation Day, marked the transformation of what had been a struggling minor school into a highachieving and nationally-recognised Public School.

His Life, Times and Legacy 9

Sir James Murray, teacher Mill Hill School 1873-1884, was a key player under Weymouth’s headmastership

Thomas Priestley was Headmaster from 1834-42; pupil numbers fell steadily after his retirement

Dr Weymouth, Headmaster Mill Hill School 1869-86, conducted a successful but short-lived pupil recruitment campaign

Sir John McClure

Headmaster of Mill Hill School 1891-1922

Mill Hill was now able to hold up its head with the best. Forget Thring of Uppingham or Arnold of Rugby; this was the golden era of McClure of Mill Hill!

The more McClure extended his influence over the School, the easier the job seemed; he looked frequently for alternative challenges. He had kept on his original Cambridge and London University links for a few years in case Mill Hill did not work out; he returned frequently now as a guest lecturer. Although he insisted on continuing to teach his specialism, Mathematics, until late in his tenure, he became ever keener to develop his musical interests. At the time few schools recognised Music as an important part of the curriculum although the choral tradition had always been strong in public schools. McClure made music a key feature of boys’ education and contributed by example. As well as encouraging regular Chapel music, he conducted ‘The Messiah’ every Christmas – the Mill Hill Magazine dutifully reported that the Headmaster’s conducting was ‘perfect’. He also contributed by playing the double bass and became an enthusiastic composer. His style was more akin to that of Sir Arthur Sullivan (of Gilbert & Sullivan fame) than to such late-19th century choral composers as Elgar, Parry or Stanford. He encouraged boys to play in a newly-formed School orchestra for which he wrote a number of pieces,

starting in 1896 with a humorous overture ‘The Coster’s Saturday Night’. This was just the beginning. Twelve years later he was awarded an extra-mural Music Doctorate from Trinity College, London.

As the running of the School became more familiar, he devoted increasing amounts of time to outside interests. Prime among these was his work for Congregationalism. He was regularly invited to preach, became President of the Congregational Historical Society and eventually in 1919 Chairman of the Congregational Union. He also established what has since become the United Reformed Church in Mill Hill Broadway. His rising reputation as an educationalist brought him to top positions in national organisations, including the Headmasters’ Association and the Headmasters’ Conference. From the beginning he struck up a close rapport with the Old Millhillians. His speeches at the Annual Dinner were much anticipated and never failed to impress and inspire. He also had a family: a wife and three children. Of his intellectual ability to contribute at a parochial and national level there is no doubt. But where did he find the time and energy? His was indeed a life of peerless dedication to the service of others. Small wonder that in 1913 he was awarded a knighthood in recognition of his services to education. Henceforth he was Sir John.

Mill Hill School Pupil Population 1891 – 1922

10 Sir John M c Clure

Borders Da y Belmont 1922 Ja n 1921 Sept 1921 May 1920 1919 1918 1917 1916 1915 1914 1913 1912 1911 1910 190 9 190 8 190 7 190 6 190 5 190 4 190 3 190 2 1901 Sept 1901 May 1901 Ja n 1900 Sep 1900 May 1900 J an 1899 Sept 1898 Sept 1898 May 1897 Sept 1897 May 1897 J an 1896 Sept 1896 Ja n 1895 Sept 1895 Ja n 1894 Ja n 1893 Sept 1893 Ja n 1891 Pr e McClur e 360 300 240 180 120 60 365 364 362 342 314 301 291 281 279 27 4 241 238 240 259 256 255 258 241 235 218 203 205 199 206 205 205 196 194 196 189 186 173 171 161 160 168 171 160 117 99 79 61

His Life, Times and Legacy 11

Mill Hill School photograph with Headmaster John McClure sitting amidst approximately 120 pupils in about 1894-95

Mill Hill School photograph with Headmaster John McClure sitting amidst approximately 220 pupils in about 1904-1905 showing the growing population of the school

Mill Hill School photograph with Headmaster John McClure sitting amidst approximately 95 pupils in about 1893: three years into his tenure McClure had doubled pupil numbers

School House Evolution

12 Sir John M c Clure

2006 1907 1825

Life and Times

An historical timeline of M c Clure and Mill Hill School 1807-1971

His Life, Times and Legacy 13

1808

22nd December: first public performance of Beethoven’s Opus 68 Symphony No. 6 Pastoral

1807

Mill Hill School is co-founded as a Grammar School for British Protestant Dissenters by Samuel Favell and Rev John Pye Smith.

1869 - 1886

Thomas Priestley

1834 October to

1852 December Thomas Priestley is Headmaster.

1860

Dr Richard Francis Weymouth is Head: MHS is ‘re-founded’. ‘The School shall be open to the sons of parents professing other religious tenets.’

1873

June: first edition of Mill Hill School Magazine. Henry Tucker, Master, suggested a formation of a society to keep former boys together and unite in support for the School. Gladstone commended it when he distributed prizes on Foundation Day 1879.

First Fives Courts built. Organ replaces harmonium in School chapel.

1874

Swimming bath built.

First Gymnasium built open to the air at the side of the playground.

1874

9th February: John David McClure was born in Wigan eldest son of John and Elizabeth (nèe Hyslop) McClure.

Educated at Holly Mount College, Bury, Lancashire.

14 Sir John M c Clure

1807-1874

Life and Times

Samuel Favell

Dr Richard Weymouth

Holly Mount College

Rev. John Pye Smith

John David McClure

School & Times

1875

First House Burton Bank in Burtonhole Lane.

1876-77

Matriculated at London Unversity Entrance Exhibition to Owens College Manchester.

1877-78

Assistant Master Holly Mount College.

Life and Times 1875-1887

1878

15 Old Millhillians meet at Freemasons Tavern, London. Old Millhillians Club, Rugby Club and Cricket Club are formerly founded.

1878-82

Master, Hinckley Grammar School.

1878

Gained a BA in Intermediate Arts from London University.

1879

2nd October: first Annual Dinner of Old Millhillians Club.

1882

Won Goldsmith’s Scholarship to Trinity College, Cambridge to read Mathematics.

Member of the Nonconformist Union at Cambridge Union presenting papers on church music and recreation for the working classes.

As Member of the Cambridge Undergraduate Preachers’ Society, McClure regularly preached in local Free Churches of Cambridge.

1885-90

Appointed Cambridge University Extension Lecturer.

1886

Graduated LLB Cambridge. Awarded Walker Prizeman at Trinity.

1887

17th December, 1887

Admitted at the Inner Temple.

His Life, Times and Legacy 15

Burton Bank

Annual Dinner Menu 1879

Hinkley Grammar School 1877

1888

Graduated M.A. Cambridge.

Appointed Professor of Astronomy at Queen’s College, London.

Life and Times 1888-1898

1889

15th July 1889: Married to Mary Johnston at St Mary Church, in the Parish of Lewisham.

July/August 1889: Honeymoon in USA; returning to settle in Ladywell near Lewisham.

1894

School becomes centre for Oxbridge examinations for the first time.

1890

17th May 1890: Birth in Lewisham of Kathleen Mary Johnstone McClure, Author of ‘McClure of Mill Hill’.

November 17th, 1890 Called to the Bar.

1891

John McClure appointed Headmaster of Mill Hill School, aged 31.

1892

21st March 1892: Birth in Hendon of Keith Alister Johnstone McClure

1894

19th February 1894: Birth in Mill Hill of Lilian Christine Johnstone McClure.

1895

Mill Hill Chapel Devotional Services Book published.

1896

School Orchestra founded.

The newly established school orchestra played McClure’s overture ‘The Coster’s Saturday Night’.

11th September 1896: Death of Thomas Urquhart Scrutton, Treasurer of Mill Hill School 1863-1896

1898

The New Chapel consecrated on Foundation Day.

The Large opened.

Much needed levelling of Top Field is undertaken.

16 Sir John M c Clure

1898 The New Chapel

1898 The Large

Acceptance letter

Wedding certificate

Mr & Mrs J McClure John David McClure

School & Times

1899-1902

11th October 189931st May 1902: The Boer Wars.

Life and Times 1899-1906

1901

22nd January 1901: Death of Queen Victoria.

22nd July 1901: Taff Vale decision by House of Lords that Trade Unions were liable for loss of company profit as a result of strike action. Widely believed to be the spur for the formation and growth of the Labour Party.

1900

Tuck Shop opens.

1900

McClure becomes member of the Senate of London University.

1901

Resigned from Senate.

1902

A staggering five Oxbridge Scholarships awarded.

1902

Elected to Council of Mansfield College, Oxford.

1903 Scriptorium No. 2 and Collinson House open. Collinson was the first ‘Out-House’.

1903

Graduated music degree, London.

President of British Chautauqua, an adult education and social movement in USA.

1904

College, Oxford

Joint Hon Secretary Incorporated Association of Headmasters.

1905 Gymnasium No 2 opens.

Foundation of the Rifle Club.

1905/6: Classroom block opens, named after Herbert Marnham, a major Old Millhillian benefactor. Herbert Marnham

1906 Elected to Corporation of Trinity College of Music.

His Life, Times and Legacy 17

Tuck Shop

Mansfield

Gymnasium No.2

Collinson House

Marnham classroom

The Marnham Block

Queen Victoria, aged 80

Buller’s Final Crossing of the Tugela, February 1900

1907

Prime Minister, Sir Henry CampbellBannerman is guest of honour at centenary Foundation Day. Marking the transformation of a minor public school into a nationallyrecognised Public School.

Life and Times 1907-1913

1910

6 May 1910: Death of Edward VII; George V reign commences.

1908

Mussons, the School shop purchased and renovated to become ‘The Grove’.

Two new Eton Fives Courts built.

1909

Priestley and Weymouth formed.

1909

1907

Chairman of Congregational Hymnal Committee.

Graduated D Mus London.

Parks

1910 Purchase of Parks field.

1911 Officers Training Corps (CCF from1948) formed.

Ridgeway opens.

1911-12 Land acquired for ultimate use for ‘Fishing Net’, Buckland Pool and Car Park.

1910

Elected to Committee of Incorporated Association of Headmasters

Belmont Music School

1912 With McClure’s backing, Belmont opens as Junior School.

Portrait painted to commemorate his twenty-first year as Headmaster.

Music School opens.

1912

Formation of Teachers Registration Council.

McClure celebrates 21 years as Headmaster.

1913 MHS came 2nd in the ‘Schools of the Empire Competition’.

1913

3 June 1913: McClure is knighted – the first ‘Incorporated Association of Headmasters’ Headmaster to be honoured.

18 Sir John M c Clure

John David McClure

School & Times

Five Courts

Edward VII

Sir Henry CampbellBannerman MP and second Liberal PM as Guest of Honour for First Centenary Foundation Day.

Life and Times 1914-1971

1914-18

28 July 1914 - 11 November 1918: The Great War.

By the war’s end a total of 1,118 pupils, OMs and masters had served in the forces. A total of 1,919 awards were given for service and valour. Trench digging, route marches, military lecture and physical training become part of the school day.

1923

April 1923: McClure Memorial edition of the Mill Hill School Magazine – the only one of its kind in the School’s history.

1924

New science block opened by Prince of Wales.

18th October 1924: Cecil Goyder made the first twoway radio communication between Britain and New Zealand from the Mill Hill School Science School

Winterstoke House opens.

1971

1920 Gate of Honour was inaugurated by General Lord Horne.

1914-15

President of the Incorporated Association of Headmasters.

1914

August: President of Mill Hill War Service Association

November: Chairman of the Education Sub Committee, Professional Classes War Relief Council.

1916 Publication of ‘Congregational History’.

1918

Vice Chairman of the Corporation of Trinity College of Music.

1919

At the invitation of George V, Sir John attends a Thanksgiving Service for the deliverance of the First World War held at St Paul’s Cathedral. A commemorative mural hangs in the Royal Exchange.

McClure chairs the committee behind the new Congregational Church Hymnal.

Treasurer of the Incorporated Association of Headmasters

1920

May 1920: As Chairman of the Congregational Union he delivers an address on the importance of public worship.

Chairman of the Corporation of Trinity College of Music.

Received the Freedom of the City of Wigan.

1922

McClure day boy house was opened.

18th February 1922: John McClure dies at MHS aged 62.

His Life, Times and Legacy 19

The Officer Training Corps on Camp

Dedication of Mill Hill’s War Memorial

Mural in The Royal Exchange City of London

Gate of Honour

A Portrait of McClure

‘He seemed to me an enormously impressive presence, with full academicals clothing his large dignified figure... The new Head was of course very much on his trial in our eyes. Not many failings could have escaped our vigilance, but beyond finding a few tricks of expression to make matter of jesting, we failed to discover any serious delinquencies, even by the schoolboy’s exacting standard.’

20 Sir John M c Clure

A boy recalls his first impressions of John McClure in 1891

Sir John McClure and the Old Millhillians Club

If it hadn’t been for the Old Millhillians, Mill Hill School may well have closed in 1891. John Hellinikakis (School 1976/Murray 1977-81) reveals the role the Old Millhillians played in putting the young and inexperienced John M c Clure up for the role and therefore securing the School’s future

His Life, Times and Legacy 21

Sir John McClure and the Old Millhillians Club

SIR JOHN Mc CLURE WAS APPROACHED TO BECOME HEADMASTER OF MILL HILL IN APRIL 1891 BY TWO OLD MILLHILLIANS FROM A SUB-COMMITTEE OF THE MILL HILL SCHOOL COURT OF GOVERNORS. THIS SUBCOMMITTEE WAS CHARGED BY THE COURT OF GOVERNORS TO FIND A HEADMASTER TO TURN AROUND THE SCHOOL’S FORTUNES. BUT WHAT MOTIVATED OLD MILLHILLIANS TO APPROACH Mc CLURE TO LEAD THE SCHOOL? M c CLURE WAS WITHOUT DOUBT A LARGER THAN LIFE CHARACTER, CHARISMATIC AND LEARNED. HOWEVER, AT THE TIME OF HIS APPOINTMENT HE WAS THE RELATIVELY YOUNG AGE OF 31 AND LACKED A TRACK RECORD OF ACHIEVEMENT AT A SENIOR POSITION IN A STRUCTURED EDUCATIONAL ESTABLISHMENT.

In a letter, featured in ‘McClure of Mill Hill’, a tribute biography written by his daughter, Kathleen Ousey, McClure writes that he was approached for the appointment of Headmaster by two Old Millhillians friends, Ernest Hampden Cook (187477) and Thomas Arnold Herbert (1878-81), whom he met while studying for a Masters at Trinity College, Cambridge, 1882-86. His relationship with these two Old Millhillians was to prove invaluable: a combination of sheer numbers of Old Millhillians on the Court of Governors and their continuous financial support meant Old Millhillians had effective control of the School and these friends were able to gain support for him across the Court. The offer to McClure of this prestigious headmastership, with hardly an explanation, dramatically changed his circumstances from being an irregular earner without a clear future elevating him to a prominent position with a regular income.

the School, on the point of closure as pupil numbers had fallen to an unviable level – a mere 61 pupils, needed a similarly dramatic turnaround in fortune.

After the comparative failure of McClure’s predecessor, Charles Vince (Headmaster 1886 - 1891) to increase pupil numbers, the Old Millhillians and Court were determined to revive the School’s fortunes. McClure knew that he was taking on a risk and might fail. Nevertheless, the Old Millhillians had rallied, found their man, and were determined to succeed.

However, having found a Headmaster, there was one further problem to contend with. Since the School was not a viable concern, it did not have the funds to secure McClure’s employment. In one of his last acts as Treasurer of the School/Court of Governors, Thomas Urquhart Scrutton (School 1840-42) wrote to the sub-committee tasked with finding a new Headmaster that additional funds needed to be raised or McClure could not be confirmed. A confidential letter was then circulated with an ambitious target of raising £2,500. The response from Old Millhillians was almost immediate and positive enabling McClure to be confirmed within days.

22 Sir John M c Clure

Extract of letter to his uncle, John Hyslop, in New York

Old Millhillians

Once McClure’s position was confirmed by letter on 11 July 1891, Thomas Scrutton instructed McClure that his task was to improve the School’s fortunes by concentrating on the educational and pastoral needs of the boys while ‘providing the connecting link binding the Old Boys together’. He was specifically not required to concern himself with the administrative and financial aspects of the job which were to be shouldered by Old Millhillians: shortly after his appointment had been made, several Governors retired and the Old Millhillians Club nominated more Old Millhillians to the Court with the specific aim of strengthening practical support for what was considered a risky appointment, even if they and McClure shared the same vision for the School.

Other prominent Old Millhillians, who supported and had close personal relationships with McClure, were Herbert Marnham (School 1874-80), who was another old Cambridge friend of over ten years, and E H Mayo Gunn (School 1870-76) who in turn secured the interest of another eminent Old Millhillian,

His Life, Times and Legacy 23

William Henry Wills, later Lord Winterstoke, (School 1842-47), provided substantial financial backing for the expansion of the Mill Hill estate

Thomas Urquhart Scrutton Shipowner and Chairman of Lloyds was Treasurer of Mill Hill School 1863-95 and secured the necessary funds to employ McClure

Herbert Marnham (School 1874-80) Stockbroker and local politician, contributed £10,000 to the 1907 Appeal to build The Marnham Block

Sir John McClure and the Old Millhillians Club

William Wills (later Lord Winterstoke) (School 184247). In 1897, after the death of Scrutton (Treasurer of the School for 33 years between 1863 and 1896), Gunn took over the role and under his encouragement Marnham, Lord Winterstoke, Richard (Dickie) Buckland (School 1878-84), and Albert Spicer (189599), became huge financial benefactors to the School.

This financial support from old millhillians, who dominated the court of governors, heralded the commencement in 1905 of a major estate expansion programme starting with the new chapel and other important buildings still standing today: the Marnham Block, Winterstoke Library, the McClure Music school and close to McClure’s heart, the Cricket Pavilion.

A further measure of support McClure enjoyed from this group of old boys is encapsulated in an anecdote from a conversation between McClure and another newly appointed headmaster, also a friend. The new Headmaster complained that as a Master, he had only his Headmaster to report to, but now as a Headmaster, himself, he had 12 tyrants to answer to. McClure replied that he had 18 Governors and a Secretary to report to. The surprised friend said, ‘and you are alive to tell the tale?’ To which McClure replied, ‘Yes, because I have 19 friends and 19 coadjutors1.’

As instructed by Scrutton, McClure made efforts to maintain constant communication with Old Millhillians far and wide. Not only did he regularly attend the London annual dinners, where he gave 26 informative speeches during his tenure, he often attended the Northern, the Scottish, and the West of England functions, all held in Spring. Out a total of nine Cambridge dinners held in 14 years, he attended six. If staying at The Lion pub in Cambridge, he would often invite Old Boys to breakfast – occasions that were described as great fun. Indeed, as a result of the enthusiasm created by McClure’s new appointment, not only were new provincial dinners instituted including one in Leeds, but a Guarantee Fund was established to help insulate the School from an expected financial crisis.

By 1902, McClure was pleased to report at the Old Millhillians Club Annual Dinner that the school had achieved five University Scholarships, far higher than the share of peer schools.

One of the greatest shows of affection by the Old Millhillians for McClure was in 1912, when he celebrated his 21st year of Headmastership at an Old Millhillians Club dinner that followed celebrations at the School. The dinner was attended by many Old Millhillians from across the country, who made speeches in praise of McClure. When McClure rose to speak, in what the attending newspaper reporters termed: ‘Indescribable enthusiasm,’ the attendees chanted, ‘McClure is Mill Hill and Mill Hill is McClure!’

But if McClure’s successful tenure was built on the foundations of the support of rich, committed, and mature Old Millhillians already in service to the Club and School as Governors, he created a whole new generation of Old Millhillian supporters from the pupils during his time as Headmaster.

24 Sir John M c Clure

1 A coadjutor bishop main role is to assist the diocesan bishop in the administration of the diocese

The First Old Millhillians Club Annual Dinner was held in 1897. McClure regularly attended the London events where he gave 26 informative speeches as well as attending the Northern, Scottish and West of England functions

McClure was a complex character; a man of his time, but progressive; a polymath with multiple interests in mathematics, music, theology, and education. Pupils were a little in awe in his presence and he was not averse to a little sarcasm, but his most endearing traits, and why many pupils were so fond of him, were his paternal instinct, generosity, and kindness.

He took an interest in all his pupils during their time at Mill Hill and continued to do so when they left. Of the many letters between Old Millhillians and himself, which appear in his daughter’s biography, there is a particularly poignant example where he commiserates with an Old Millhillian, whose daughter has died. Obvious from the many letters is that old boys continued to communicate with McClure long after they left the School, often concerning very personal matters.

In another letter, McClure thanks an Old Millhillian for the gift of a cheque and acknowledges what the donor suspects, that McClure cannot accept it for himself, but he adds that there is a pupil of meagre resources, who has need of clothes for whom these funds will be useful. This letter not only exemplifies the esteem that McClure is held by an Old Millhillian, but also his attention to the needs to those within his charge.

Sadly, in his third decade at Mill Hill, the war broke out and McClure came to the terrible realisation that almost every Old Millhillian, who had fallen or was wounded during the conflict had been one of his pupils and he could name them all. McClure’s war is covered in another chapter The War Years 1914-1918 (see page 95), but it is apparent that McClure’s correspondence with old boys hit a whole new level of intensity, whether it was supporting a pupil’s decision to go to war, reassure an Old Millhillian or parent, or to commiserate for a loss of a son, husband, or brother.

The Old Millhillians Club took a risk that McClure was the man to turn around the fortunes of the School and they supported him unquestionably. Fortunately, McClure rose to that challenge and set the School on a trajectory, from which Mill Hill has never looked back.

Old Millhillians Club and M c Clure Memorabilia

This commemorative badge was awarded by the Old Millhillians Club to Annie Pearse Lady Resident or Matron of School House from 18991926 in celebration of her 21st anniversary at the School. Arguably, Annie was the first female Honorary Member of the Old Millhillians Club. Aside from being held with esteem and affection by Old Millhillians she was also a muchappreciated stalwart of the McClures so much so she accompanied Sir John’s widow to his funeral in 1922. Upon her retirement the Club presented her with a jewelled watch. She bequeathed the badge to Mary, Lady McClure, whose family in turn repatriated it to the Club. Each year the badge is presented to the incoming Vice President at the Old Millhillians Club Annual Dinner.

His Life, Times and Legacy 25

A handwritten note – assumed to be in the handwriting of the McClure’s daughter Kathleen (Ousey) – explaining the history of the badge

A Portrait of McClure

‘His reports to the Governors were never prolix and always informing, and he would often listen to a discussion for some time before giving his verdict. His eyes would blend vigilance and amusement, and then he would sum up the discussion with a clarity of judgement which illuminated the whole situation.’

A report from a Governor of the time

26 Sir John M c Clure

The Court of Governors and McClure

Peter Wakeham (Burton Bank 1960-64), Chair of the Old Millhillians Club, has trawled 31 years of copperplate Court of Governors’ committee meeting ledgers to understand how the financial and administrative support they provided allowed M c Clure and the School to flourish

His Life, Times and Legacy

Mill Hill School Court of Governors’ ledgers that record the minutes of their monthly meetings in beautiful handwritten copperplate

The Court of Governors and McClure

I n S I r John Mc c lure’S era , the c ourt M et Monthly – More frequently than the current c ourt of G overnor S . the aG enda

I te MS dIS cu SS ed were recorded I n

G reat deta I l , typ Ically I n the Mo S t eleG ant, G ra MM at Ically perfect copperplate handwr I t I nG. the MI nute S probably took lonG er to wr I te than the M eet I nG took I t S elf!

The minutes also suggest that the Court was more engaged with operational matters than would be the case today. The Business Committee and Finance Committee in particular appear to be heavily involved in the management and reporting on day to day commercial matters. Sir John was left to ‘run the School’.

On 31st January 1922, the Governors met as usual at the Baptist Church House in Mill Hill.

The meeting opened at 4.45pm. The Right Honourable Sir Albert Spicer, Bart was in the Chair. His co-Governors at the meeting were Dr H Morley Fletcher, Messrs R W B Buckland, A W Pickard – Cambridge MA, F A Wright MA, T A Herbert KC, N Micklem KC, H Marnham, G W Knox, E S Curwen and F L Lapthorn.

Sir John and the Clerk attended and Dr H J W Martin was also in attendance.

The agenda was a full one but the items involved nothing atypical: the Headmaster’s Report; the Treasurer’s Statement; the Report of the Business Committee; the Report of the Medical Officer on School Meals; Board of Education negotiations on Belmont pensions; presentation of a silver salver and cheque to Dr Martin for long and honourable services to the School; discussion on the Board of Education’s views on the issue of notices to Local Education Authorities regarding the offer of places under the School Teachers’ Superannuation rules; report from the consulting Dentist on dental decay among pupils.

The Clerk was instructed to circulate a list of dates for the meetings of the Court in 1922. It was resolved to follow the same procedure as to days as in 1921, but to alter the hour of meeting to 4.30pm, and to provide tea at that hour.

Eighteen days later, Sir John McClure passed away, six days before the next meeting of the Court.

There is no hint in the January 1922 Court minutes of any health issues regarding McClure. It is ironic that the great man’s final Court meeting was so spectacularly normal, although, had one known it was his finale, there was still much to applaud in his Headmaster’s Report:

The Mill Hill pupil population was 282 compared to 61 when he was appointed. Boarders were 260 vs 42. There were a further 83 pupils at Belmont.

Oxbridge entrances were successful and Mill Hill had obtained its first ever mathematics scholarship at Hertford, Oxford, another at Corpus, and a Classics scholarship at Queens, Cambridge.

Two additional School Entrance Scholarships were recommended for approval.

Captain G J V Weigall, former Cambridge Cricket Blue and Kent CC XI and sports journalist for The Times, was to be appointed to take charge of cricket at the School.

The revision of the Service Book for the Chapel had been completed and was ready for printing.

Issues to be resolved had a familiar ring to them. Boarding accommodation was insufficient and the issue was referred to the Business Committee. Influenza was rife and Sir John recommended inoculation in a letter to parents:

Plus ça change!

Sir John McClure’s relationship with the Court of Governors evolved over a period of 30 years.

28 Sir John M c Clure

His Life, Times and Legacy 29

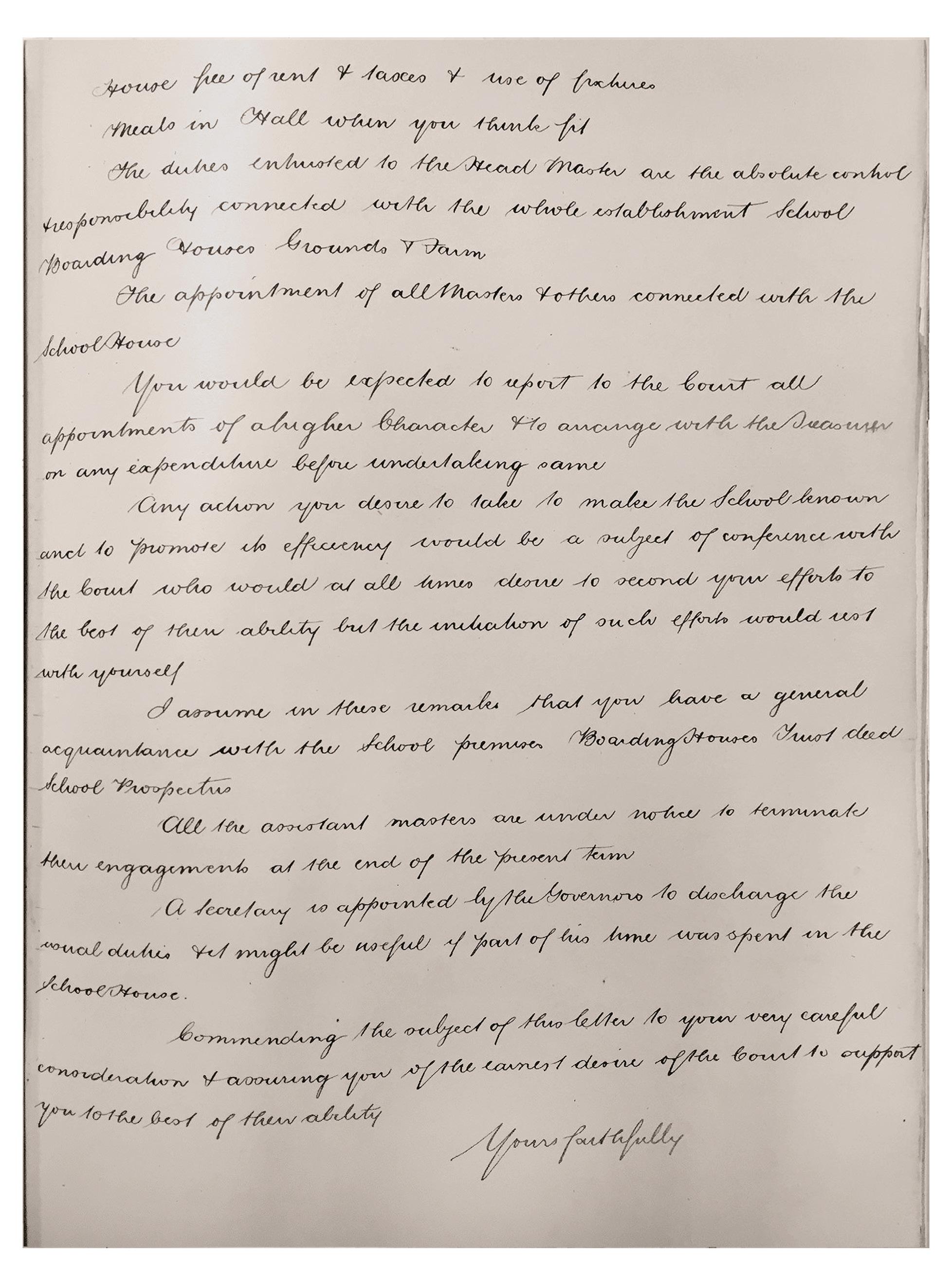

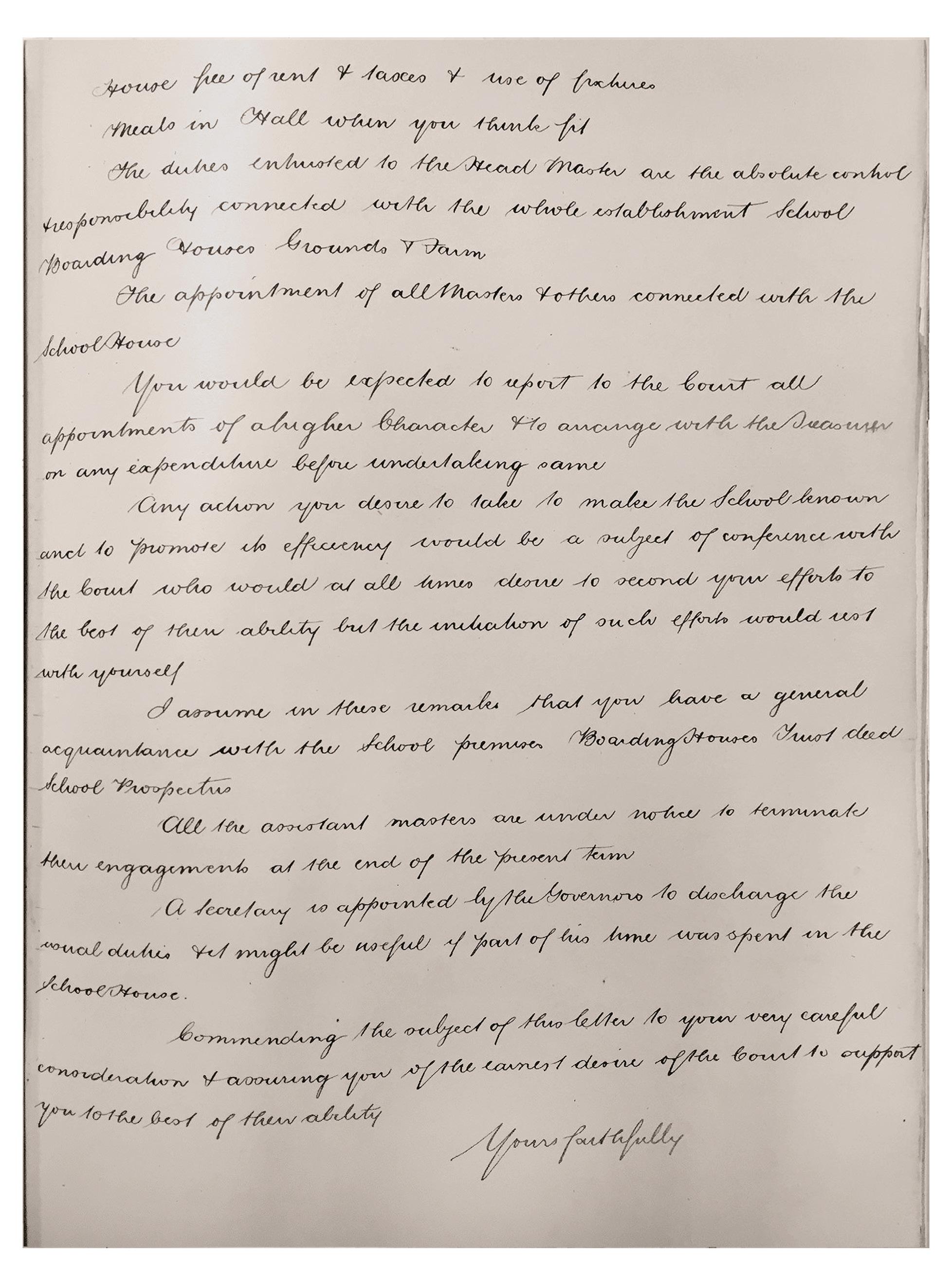

A three page letter, above and overleaf, was sent to John McClure in 1891 offering him the job of Headmaster of Mill Hill, it is signed by Thomas Scrutton, Treasurer of the Court of Governors

The Court of Governors and McClure

30 Sir John M c Clure

His Life, Times and Legacy 31

The Court of Governors and McClure

He inherited a financially fragile School with an indifferent reputation. By the time of his death, Mill Hill had been transformed and much of what he achieved remains as one of the cornerstones of the School’s value system and real estate.

1891-1895

gaining Court confidence

It is hard to imagine what was on McClure’s mind when he met for a ‘conversation’ with Governors on 9th June 1891, having failed to attend the original meeting scheduled for the day before. He would have been aware that Charles Vince, the Headmaster since 1886 had resigned on 4th June 1891, the School having been placed in the hands of the Committee of Governors for over six months since 13 November 1890.

Mill Hill School was in serious financial difficulties. The Court was recruiting a new Headmaster. Mr Paton of Rugby, Mr Green of The Leys and Mr Jessop, senior maths master at Reading had all turned down the opportunity. McClure had no track record as a Headmaster or as a turn-around specialist. Yet on 24 April 1891, at a Life Governors meeting called by Special Notice from the Court of Governors, the Life Governors (all Old Millhillians) had presented a report recommending that Mr J D McClure be appointed as Headmaster, as explained in the chapter ‘McClure and the Old Millhillians Club’ (See page 22).

A Guarantee Fund was to be set up, comprising £700 from members of the Court, £500 from the Old Millhillians Club and further promises of £165 per annum for three years and 20 guineas for two years. McClure accepted the offer to become Headmaster on 11th July 1891.

The governors set him his initial task which was to strengthen the teaching staff. In the first meeting, on the 23 September 1891, he reported on new appointments. In December, he reported on the establishment of a Tuck Shop following complaints from pupils of prices at the local shop.

It takes time to re-build a school’s reputation.

Initial progress was slow and the school’s finances remained fragile, with losses to the tune of £2,000 per annum and no increase in pupil numbers.

Capital expenditure (CapEx) was restricted, including postponement of the renovation of the gymnasium floor. In April 1892, a £5,000 loan secured against (the original) Burton Bank and the Sanitorium was borrowed at 5% from Mr Enoch Taylor.

In 1893, came the first real indicators of improvement. In January 1893, McClure reported a better revenue per pupil mix – 79 boys at the School of which 42 were boarders vs 37 in the prior term. By May, there were 95 and a further 4 entered in June. Entries at that time did not have the Autumn Term peak that Mill Hill sees today.

In July 1893, McClure published a new Prospectus which no longer referred to day pupils. The Court gave McClure discretion to admit day pupils, but the strategic direction was clear: Mill Hill was to be primarily a boys’ boarding school – and so it remained for a large part of the 20th century.

By September, there were 119 pupils at the School. The Treasurer, Mr Buckland, proposed that four hot baths be fixed at the Swimming Pool – at a maximum cost of £50. Things were looking up, so much so that in July 1894, McClure proposed raising the school fees for boys aged under 11. The Court postponed a decision on this – several times. Pupil number growth was the preferred driver of revenue growth – and it was successful. By January 1895, the pupil population was 160.

1895-1911 The Wills era

William Henry Wills (School 1842-47), later 1st Baron Winterstoke, was a member of the wealthy Wills family and worked for the family tobacco firm from an early age. In 1858 he went into partnership with two of his cousins to take over WD and HO Wills which later became the Imperial Tobacco Company and is today Imperial Brands plc. He was a Governor and subsequently Chairman of the Court.

By 1895, McClure clearly had the confidence of the Court and Sir William. He had doubled pupil numbers in four years while patiently accepting the financial constraints he had inherited. Moreover, he had also found the time to compile a Book of Services for use in the chapel. But the time had now come to invest in fixing the estate which had so long been neglected.

32 Sir John M c Clure

His Life, Times and Legacy 33

McClure’s handwritten letter to Thomas Scrutton accepting the role of Headmaster of Mill Hill School in 1891

The Court of Governors and McClure

The Court approved a number of CapEx projects in quick succession; a project to provide heating in the chapel along with a budget of £20 for repairing the organ; an extension to the kitchen and construction of a new pantry; a hot water system for School House.

At the 19 November 1895 Court meeting, the Governors congratulated McClure on his election to the Headmaster’s Conference and approved a budget of £100 for advertisements to promote the School.

At the 21 January 1896 Court meeting there was much to celebrate. Pupil numbers were up to 168 and the School had made a surplus of £850.

Sir William offered to lend a sum to build a new dwelling house for the McClure family. A Special Committee of the Court resolved to meet with a local landlord to discuss the possibility of leasing a new building and to meet with Sir William regarding the possibility of him contributing to the construction of a new chapel – the one we all know and admire today.

At the meeting of 30 March 1896, Sir William Henry Wills was elected as the first Chairman of the Court and so began a period of unprecedented expansion of the school estate.

A Finance Committee and Buildings Committee were established to review a number of important projects for repair, to maintain the estate and outline plans for a dwelling house for McClure and the new School chapel. Sir William agreed to lend up to £4,000 at 5% over seven years so that the School could meet sundry creditors and pay off a few small loans on the Balance Sheet. By April, plans for the new chapel were approved and a tender process was initiated. In June, Sir William advised the Court that he had purchased land adjacent to the School and offered to present a piece of it to provide a dwelling house for McClure.

Compared to the relative calmness of his first four years as Headmaster, McClure’s feet never seemed to touch the ground during the Wills era. The pace of change was rapid by any standards.

July 1896: Tender for new chapel approved at maximum cost of £4,200. McClure confirms £3,000 donations already committed. Sir William offers a further £500.

October 1896: chapel stone laid by Sir William

November 1896: Sir William purchases a cricket field for lease back to the School.

July 1897: Sir William pays for heating of chapel and swimming bath.

February 1899: McClure is elected to the Parliamentary Committee of the Headmasters Association.

June 1899: Sir William offers to donate £1,000 to enable Chemical Laboratories to be built and Music Rooms to be upgraded.

February 1900: approval for new Tuck Shop (completed September 1900).

October 1900: new Boarding House proposed; new library building completed.

December 1900: new laboratories completed; fit-out of library completed.

But rapid expansion came at a cost. In November 1900, Sir William declined to advance any more to the School and recommended that existing debts be reduced. Despite a pupil population in excess of 200, the Finance Committee decided to freeze 1901 CapEx and undertook a detailed review of the School’s cost structure, including the sale of cows on the School farm to Friern Barnet Dairy Farm! The pressures to contain costs lasted until April 1902.

Rapid expansion also took a toll on McClure personally: in October 1901 he resigned as Headmaster of Mill Hill on grounds of ill health.

Uncharacteristically, he handled his resignation in a very clumsy way. He made his intentions known to staff before advising the Governors – for which he was reprimanded and subsequently highly apologetic. Unsurprisingly the Court intervened and succeeded in persuading him to change his mind. At a special

34 Sir John M c Clure

Court Meeting on 5 November 1901, the Court accepted his withdrawal of his resignation.

In April 1902, the Court set up a Special Committee to consider and report on a Scheme of Enlargement of the School. In July, the Committee recommended building a new boarding house to accommodate 40 pupils. In October, the Court sanctioned the purchase of two plots of land to give significant additional frontage to the School.

At the Court Meeting of 25 March 1903, the principles of the House system were laid in a report from the Treasurer. Finance was as much a factor as the boarding environment. A school of 300 boys was envisioned – 100 in School House (reduced from 123) and the remaining 200 accommodated in houses each designed to take about 40 boys. The question arose as to whether the houses should be Hostels or Boarding Houses. In the former, the Housemaster received a fixed salary and his duties were magisterial. He had nothing to do with the boarding of the boys and got no profit from it. A Matron was in charge of all domestic arrangements and the fees were paid to the Treasurer. The Boarding House system was more entrepreneurial, whereby the masters undertook the risk of building and furnishing the houses at their own expense. Tuition fees were paid to the Treasurer and Boarding Fees to the Housemaster. This business model evolved whereby ‘the Governors owned the house and rented it to the master, who would pay the tuition fees and earn a profit out of fees charged to parents’. Food for thought!

The Governors decided to run the two systems concurrently and, following input from other Headmasters (including Rugby, Charterhouse, Repton and Marlborough), drew up a set of rules for a Boarding House system. The Headmaster was to have absolute discretion as to which House a boy was allocated, and School House was the priority to fill. No switching between houses was permitted.

The Housemaster was responsible to the Headmaster for the regulation and good management of the house. Collinson House was the first new house in 1903 Mr Hallifax was offered the tenancy at £400 per annum with a guarantee of 40 boys at a boarding fee the same as School House – 22 guineas per term – and hence an income of about £2,700 per annum (£334,000 in 2021 money).

His Life, Times and Legacy 35

Rapid Expansion took place in the 'Wills" era adding numerous new buildings and facilities to Mill Hill School many of which are still in use today.

1890s John McClure and his family move into St Bees the Headmasters’ new house

1903: the Scriptorium opened and is still in use today

1903: Collinson House opened accommodating 40 new boarders

1902: the Tuck Shop opened after complaints of high costs at the local shop

The Court of Governors and McClure

Expansion of the School estate continued with the opening ceremony of the Murray Scriptorium taking place on 17 December 1903. In March 1904, the Sub Committee of the Finance Committee submitted a scheme for a special appeal in connection with the centenary of the School in 1907. The appeal would fund a plan to enlarge the School to accommodate 300 boys, creating essentially the fabric of the Quad that was still in place in the 1960s. New additions included: the Large for assemblies; 15 classrooms; heating for new buildings; School House and a swimming bath. The plan was approved at a meeting of the Court on 22 February 1905.

The 1906 spring holiday was a busy one for McClure. He took his leisure time to prepare three significant papers for the Court. In anticipation of legislation that would require all schools to be inspected, McClure formally proposed that Mill Hill should aim to be inspected by the Joint Board of the Oxford and Cambridge universities. He further proposed that exams should be undertaken in July instead of December and that the system of School Certificates should replace current examinations. His third paper proposed a system of annual salary reviews for masters. The Finance Committee considered in depth and approved this proposal finally in February 1908, with the proviso that it was a matter of School policy but not a contractual commitment to the teaching staff.

In 1906, the Governors adopted a rule that no boy would be admitted as a pupil of Mill Hill School unless he was vaccinated against small pox. In July 1906, McClure and the Court received what is a now a familiar letter from a prospective parent, Oswald Earp. In the letter he stated that he would not send his boys to Mill Hill since he considered compulsory vaccination to be ‘a violation of elementary human rights’ and a totally unproven and even dangerous medical intervention. Plus ça change.

The 1907 Centenary celebrations went ahead as planned and Mill Hill was honoured by the Prime Minister, Sir Henry Campbell Bannerman, attending the event and giving the prizes.

In October 1907, a Sub Committee was set up to consider the future constitution of the Court recommended that it was desirable that the Court

of Governors include ‘personas of experience of other schools or persons of special educational eminence provided that the full predominance of Old Millhillians remains assured’.

The expansion of the School estate remained on track. Sir William made a gift to the School of £10,000 which facilitated the building of the Winterstoke Library. However, in January 1908, the Court rejected as undesirable a proposal to lease Bittacy House as a Junior preparatory school – presumably as a result of concerns that Mill Hill pupil numbers would be cannibalised by a focused prep school. This concern was subsequently proved unfounded when this idea returned a few years later in the guise of Belmont.

There was a change of pace in 1909: at the 31 March Court meeting, the Governors decided to reduce the unsecured loans of Lord Winterstoke. CapEx was confined to urgent priorities. However, in April the following year,

Lord Winterstoke offered to sell a plot of his land for a new House to accommodate 45 pupils. The transaction completed a month later and in December 1910 Lord Winterstoke loaned £10,000 at 3% secured against Collinson to build the new House.

36 Sir John M c Clure

1907: Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman MP and second Liberal as Guest of Honour for First Centenary Foundation Day

On 29th January 1911, Lord Winterstoke died, aged 80, without heirs, leaving £2.5 million – the equivalent today of close to £310 million. The Court of Governors are said to have assumed that his will would include a clause writing off his loans and mortgages with regard to the School. However, that was not to be: the executors of the Lord Winterstoke’s estate recommended to the Court the institution of a sinking fund under which all the mortgages – approximately £40,000 (£4.9 million in 2021 money) – could be paid off over 30 years. If that proposal was approved by the Court, the Winterstoke estate would agree to lend a further £3,000 to fund the purchase of two fields in Hammers Lane opposite the West Grove Estate – ten acres of land adjoining the School.

On 1 February 1912, the Court approved the sinking fund, acknowledging that, for at least another 10 years, CapEx would be strictly limited and there was to be ‘great economy in the general management’.

Meanwhile the Court approved a proposal from the Old Millhillians Club to present a portrait of McClure and build a Music School to celebrate his 21 years as Headmaster.

For this £3,000 needed to be raised, most of which had already been committed and donated by Old Millhillians.

In June 2012, arrangements were concluded between the Court and Rooker Roberts regarding the establishment of Belmont. Rooker Roberts drove a hard bargain. Belmont was to be licenced for 10 and ultimately 30 pupils. All boys entering Mill Hill under the age of 13 had to be sent to Belmont until they reached the age of 13. Belmont would be regarded as one of the School houses with equivalent regulations and privileges and paying same fees, for as long as Rooker Roberts remained a master at Mill Hill School.

The pace of change again took its toll on McClure’s health. In November 1912, the Court unanimously agreed to ‘grant Dr J D McClure prolonged leave of absence in accordance with the recommendations of the Medical Officers’. Dr Arthur S Way was appointed as temporary Headmaster to hold the fort for two terms.

His Life, Times and Legacy 37

1912: Belmont opened and was treated as one of the School’s houses

1911: Ridgeway House opened to accommodate a rising number of boarders

1907: Marnham Block classroom interior

1907: the Marnham Block, as celebrated on a Wills cigarette card, opened to provide new classrooms

The Court of Governors and McClure 1913

On 16 July 1913, the Court of Governors met at 6pm in Common Room 12 of the House of Commons. In the Chair was Sir Albert Spicer, Bart MP. The Chairman moved and the Vice Chairman seconded: ‘that the Court of Governors Offers its hearty congratulations to the Headmaster upon the honour recently conferred upon him by His Majesty, and desire to express its contuniued appreciation of the services tendered by Sir John McClure to Mill Hill School and to the education throughout the country’.

This was carried unanimously.

Sir John McClure was to be one of only six Headmasters of Headmaster Conference schools to be knighted. At the 2 October 1913 meeting of the Court, the Governors reiterated their congratulations to Sir John personally and welcomed him back from his sabbatical.

The Great War years 1914-18

What is striking about the business of the Court during World War I is the normality of the agenda. Sir John continued to report on matters in a similar vein to pre-war meetings remaining sharply focused on maintaining the pupil population at pre-war levels, School and University entrance scholarships, teaching staff remuneration and the implementation of a Masters Retirement Fund. He always commented on the health of the School in his report and from time to time there was a report on dental hygiene and the percentage of pupils with tooth decay.

In fact, the size of the pupil population was remarkably unaffected by the war, despite pupils being forced to leave school prematurely due to call up for military duties. Nevertheless, McClure expressed his concern to the Court that pupils were leaving ‘earlier than desirable for their selfdevelopment’ and that he was appointing less able and mature prefects and monitors.

In October 2015, three Belgian boys entered the school following a request from the War Refugees Committee. The Court then

authorised Sir John to admit a maximum of 10 sons of Belgian refugees as day boys, free of charges, provided they had access to acceptable guardians.

The number of pupils actually grew in the latter war years and there were a record number of entries in Spring 1919.

Maintaining the quality of teaching staff became an ever-increasing challenge as masters were called up for the forces and difficult to replace. In February 1916, all masters holding commissions in the Officers Training Corps (OTC) were asked to sign a document whereby they accepted liability to serve in any place outside the United Kingdom.

Sir John reported to the Court that the War Office made repeated demands to the Headmaster’s Conference that only those officers should be spared whose goings ‘would impair the efficiency of the school both military and scholastic’.

Subsequently McClure was authorised by the Court to appeal for the total exemption of Housemasters who were of military age. For the most part, this appeal only delayed the inevitable call-up.

In 1916, the Court requested that the names of the fallen Old Millhillians serving with Colours be added to the report with details of any distinctions gained. These names were not recorded in the Court minutes but comprehensive records were kept, as current pupils will know from the Gate of Honour and the reading out by incumbent Heads during the Remembrance Day Service in chapel of the names of the fallen – just as Sir John did during Sunday chapel services at that time.

The 15 June meeting minutes refer to the death in battle of R A Lloyd, Scholar of Peterhouse College, Cambridge, holder of one of the Wills scholarships but perhaps surprisingly, there is little hint in the minutes of the emotional trauma that the Headmaster must have suffered as he learned of the deaths in battle of former pupils he had

38 Sir John M c Clure

known and taught. Scholarships to the school and to universities remained an important focus for Governors and the Headmaster.

McClure saw fit to initiate discussion with the Court on the future of the curriculum. Greek was compulsory for entrance into Oxford and Cambridge at this time but ‘Modern’ subjects –Chemistry, Physics, Biology and Botany – were increasingly important in newly created local Secondary schools and Germany was already sowing the seeds of its now formidable apprentice system through Vocational and Technical schools. McClure saw the need to place more emphasis on ‘the Modern Side’ but was equally concerned that such pupils ‘failed to show an intelligent interest in History, Literature and the great Ethical and Cultural questions’.

As with all matters affecting education, he took the emerging importance of Science very seriously. He instigated in 1916, and subsequently in 1919, various options for the creation of what we now refer to as the Crick Building (aka the Science Block). He sought and got Court approval in October 1918 for him to join the League for the Promotion of Science in Education.

McClure routinely reported to the Court on the health of the School and the occasional incidences of rubella, measles, chicken pox and even one case of small pox, which was traced to a source in Finchley. In mid-July 1918, there was an outbreak of what turned out to be Spanish Flu that affected over half the School – 145 pupils in total. Isolation measures were put in place and ‘healthy’ boys sent home. Exams were abandoned. A subsequent wave returned in February 1919 – familiar territory!!

War ended on the 11 November 1918 and the Court met on 27 November. The Agenda was business as usual. The 1919 pupil numbers, including a record 45 at Belmont, were 314. On 7 November 1919, the Governors received the following report from the Inspector of the Board of Education:

‘Dr Cookson, the Chief Inspector, stated that the work that Sir John McClure had done – not only at Mill Hill but for education as a whole was very well known. The Governors were to be congratulated on possessing a

His Life, Times and Legacy 39

The Winterstoke Library interior

1907: the Winterstoke Library adjacent to the Scriptorium added to the Quad

1920: the Gate of Honour was opened by Lord Horne on the 30th October

1913: the Music School opens and is dedicated to McClure with a plaque

The Court of Governors and McClure

Head so eminent in his profession, a man of such wide culture, and of so genial a character, with all of his physical and intellectual activities still unimpaired’

Post war years 1918-1922

1920 was a busy year. In addition to the routine agenda items, there was considerable time spent on dealing with policy initiatives affecting the future development of the School. The nomination of Representative Governors was approved. Pupils on scholarships were not to exceed 5% of the roll. Day pupils should not exceed 20% of the roll. The Old Millhillians Club made representations to the Court via Sir John regarding the appointment of a curator for the Winterstoke Library and for profits from the Tuck Shop to be used for improving sports facilities at the School. The Club recommended investment in athletics, the appointment of a Games Master and increased salaries for the athletics and cricket coaches and the Groundsman. Sir Ernest Shackleton visited the school in June and gave a short lecture on his Antarctic Expedition.

The War Memorial Fund finally totalled £19,421 and the Gate of Honour was opened by Lord Horne on 30th October 1920.

The King had been asked but the Court was advised by Lord Bryce that the King could not accept an invitation of this kind. The inauguration ceremonies were both religious and military in character.

The challenges of recruiting high-calibre teaching staff persisted in 1921. Four sons of Old Millhillians killed in the war were granted scholarships funded by the Old Millhillians Club Scholarship Fund – set up in 1915 for this purpose – and topped up by the War Memorial Fund. Lord Sumner presented the prizes and gave an address at Foundation Day. Sir Albert Spicer resigned as Chair of the Court in July 1921, a position he had ‘occupied with conspicuous success’ since the death of Lord Winterstoke. His reason was disarmingly candid – ‘deafness’. He was no longer able to keep track of Court discussions. Nathaniel Micklem was elected to replace Sir Albert as Chair of the Court. In September 1921, a Salaries Committee was established to confer with a deputation of Assistant Masters who made recommendations on behalf of the staff for what one

might term a coherent salary structure that took into account; degree and other qualifications; experience and style of work to be performed.

The Court referred the report to the Committee which returned in October with comprehensive recommendations including an increase in masters’ salaries. There are no minutes recording McClure’s response to the deputation or to the report or to the final recommendations. N G Brett James, Housemaster Ridgeway, represented the staff in follow-on communications with the Clerk. He raised the point that Army experience should be taken in to account along with extra duties such as athletics or military.

In October 1921, McClure advised the Court of the sad news of the death of Edward Cunningham, a Burton Bank Monitor, from hypertrophy of the heart. The Coroner held the inquest in the school sanitorium, at which the boy’s father was present.

Sir John McClure was Headmaster of Mill Hill for over 30 years, a tenure far longer than any Head would expect to last today, or indeed in the past 215 years – as the chart opposite shows. There are good reasons why Mill Hill has Houses today named Priestley, Weymouth as well as McClure.

The continuity and stability implied by this length of time on the job almost certainly explains McClure’s enduring impact on the fabric and values of Mill Hill School.

He is often referred to as the ‘Maker of Mill Hill’ and for good reasons. He rescued the school from financial disaster, transformed the estate, and increased the boarding pupil population by 600%.

He could never have achieved what he did without the strong support from the Court of Governors and, as noted elsewhere in this publication, the Old Millhillian community. That support was forthcoming over so many years because McClure delivered on his promises, adored the school and was worshipped by pupil and parent alike. His relationship with the Court was pivotal.

40 Sir John M c Clure

Heads of Mill Hill School Years' of Tenure

His Life, Times and Legacy 41

NAME YEARS Sir John David McClure 31 T homas Priestley 18 Richard Fran cis W eymo uth 17 Ma urice Leon ard Ja cks 15 Alastair Carew Graham 13 W illiam Winfield 12 Dominic Lu ckett 8 Philip Smith 8 Michael Hart 7 Ro y Moore 7 John Seldon Whale 7 Ma urice Phillips 7 John Humphreys 6 Charles Arthur Vin ce 5 Jane San chez 4+ Alan Fraser Elliot 4 George Don ald Bartlet 4 Eu an Archibald Ma cAlpine 3 Arthur Rooker Roberts 3 W illiam Flavel 3 H. L. Berry 3 John Atkinson 3 F ran ces Kin g 2 T homas Kin gston Derry 2 Robert Cullen 2 James Corrie 2 W illiam Allan Phimester 1 Ma urice Leon ard Ja cks 1 Philip Chapman Barker 1 George Samuel Evans 1

A Portrait of McClure

‘He was easy of access, essentially human, and possessed of a very kind heart. His purse was often opened to help boys whose parents were not well-off. The boys were proud of their Headmaster: listening with pleasure to his witty conversation, admiring his remarkable memory and valuing the many striking sermons in which he appealed to them to lead a manly life‘.

The verdict of a Governor of the time

42 Sir John M c Clure

Religion

Former School ChaplAin, the Reverend DR Richard Warden reflects on how Mc Clure’s Nonconformist Christian faith and principles guided his approach to education and the development of the school and the pupils’ moral and spiritual compass

Religion

A calling to Mill Hill

On leaving Cambridge, as a young man with a deep Christian faith, McClure had at least one offer to become a Pastor within the Congregational Church, the Nonconformist denomination of which he was a lifelong member. However, he decided his vocation was to education and as a layman in the church, rather than as an ordained minister.

When he was offered the position of Headmaster of Mill Hill in 1891, he understood it as a calling by God, partly because he had not formally aplied for the position, but rather it had been offered to him.

As he said in his Mill Hill centenary speech: ‘I felt that I had received what used to be known as “a call from the Lord” not, like some calls from the Lord, to a larger salary, but to larger service; to greater emoluments, but to greater responsibility.’

Mill Hill was the perfect fit for him, having been founded 84 years earlier in 1807 by a union of three Nonconformist denominations – Congregational, Presbyterian and Baptist – originally as the Protestant Dissenters Grammar School. Although an accurate description, he later explained his dislike of the negative connotation associated with dissent, preferring the more positive aspects of Nonconformism, not least that it was unique among the country’s boarding schools in being non-denominational and ‘devoted to freedom in theology and religion.’

Following one memorable Old Millhillians Annual Dinner in 1912 after 21 years of Headship, he said:

Vision of education

McClure’s Christian faith was at the heart of his vision of true education and, ‘the development of moral and spiritual power was... something to be much thought about and much prayed about.’

The School did not have a Chaplain at that time, but as Headmaster he carried out many of the Chapel roles now associated with chaplaincy, as well as offering spiritual and pastoral care to boys and their families. He also presided at many Old Millhillians’ weddings and any subsequent baptisms, and sadly at too many funerals. In many ways, we might say that the School became his Congregation. Indeed, in his final speech at the end of his year as Chairman to the Congregational Union he said as much: ‘I too, though not a minister in the stricter sense, have a “cure of souls’; so I speak to my fellow-ministers as a brother and a friend.’

Academic achievement was a priority, but for McClure, the development of moral and spiritual power in the boys was an even higher priority as he expressed in his first speech to parents following his appointment. ‘To see a boy morally and spiritually strong, full of reverence for all that was really great and good, and loved by his fellows on account of these things, was to realise what true education meant and was of infinitely greater importance than prizewinning, prizes being after all, but the whips by which boys are goaded to activity.’

PrinciplEs of Nonconformism

Few would detract from that conclusion either during his lifetime, or when reflecting on his contribution to Mill Hill 100 years later.

To understand Mill Hill, and the origins of McClure’s Nonconformist Christian faith, we must briefly go back to 1662. At this pivotal time in British church history, Protestant dissenters rejected Parliament’s 1662 Act of Uniformity that required clergy to give unconditional assent to use only the services found in the Church of England’s Book of Common Prayer, together with a requirement to take an Oath of Canonical Obedience to the Church of England Bishops. In that year, over 2,000 clergy refused to ‘conform’ to this Act, an act of ‘dissent’ which led to them losing their livings. This exodus of clergy came to be known as ‘The Great Ejection’ and signalled the birth of the Nonconformist Christian denominations.

44 Sir John M c Clure

‘I think I may truthfully say without any boasting that I have tried always to live up to the ideals of our first founders, and to carry out, both in letter and in spirit, the wide and Christian spirit in which they laid the foundations of Mill Hill.’

The Chapel

It is fitting that Sir John McClure’s ashes and later those of his wife Lady Mary McClure are laid to rest in the School Chapel, as he was largely responsible for its existence. In his early days as Head, he described himself as being ‘brazen’in his ambition for a new Chapel to be built, which was to be the third in the School’s history. This was to replace the second Chapel which we now know as The Large, because it was too cold and too small to accommodate the School’s growing numbers. He set up a Chapel Fund for this vision to be realised and it was opened on Foundation Day 1898. For 24 years in this beloved Chapel he led School worship, prayed, preached, played music and sang, and those of us who follow him are forever grateful that his ambition became a reality. He would be delighted that ‘his’ Chapel is still at the very heart of the Mill Hill pupil experience.

His final resting place in the Chapel walls near the Head’s stall lies under the Isaac window, which was dedicated to him on Old Boys’ Day in 1922. Overhead, above the window there is a mosaic of angels, together with McClure’s initials and the dates of his tenure at Mill Hill. On the outside of the Chapel, the place is memorialised with a large stone tablet inscribed in Latin which includes the words;

‘In loving memory of John David McClure M.A.; LL.D.; D.Mus... the beloved Headmaster of this School upon whose interest he lavished his every purpose, endeavour and physical power, until he raised it from a humble position to greater prominence.’

As a mark of respect, it became a long-standing school tradition that when boys passed this place on their way to Chapel every day, they removed their hands from their pockets and kept a respectful silence.

45

The Issac window was dedicated to McClure on Old Boy’s Day in 1922. His ashes are buried beneath it

New Chapel architectural drawing of the proposed interior

The ‘new’ Chapel was was entirely McClure’s inspiration and he described himself as ‘brazen’ in his ambition for it to be built

In 1912, McClure was invited to give a speech commemorating the 250th anniversary of this event. Apparently, his words caused some controversy, but they give us an insight into his broad and generous understanding of Christian faith. To the consternation of some, he refused to condemn the existence of the established Church of England. Rather he sought to find ways of building bridges of reconciliation, making a plea to ‘bury bitterness and recrimination.’

The Commitment to Religious Freedom and the Absence of Conformity