Rediscover safari’s romance at Satao Campcanvas comfor ts, star-f illed nights, and daily elephant parades at our waterhole.

How close did Kenya come to having its white settlers declaring their independence from Britain?

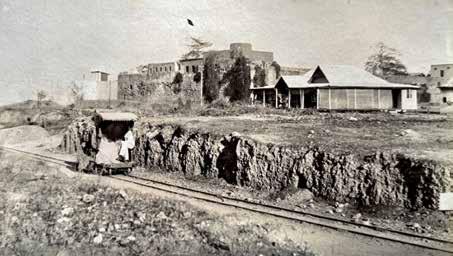

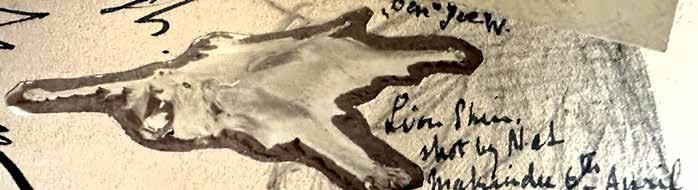

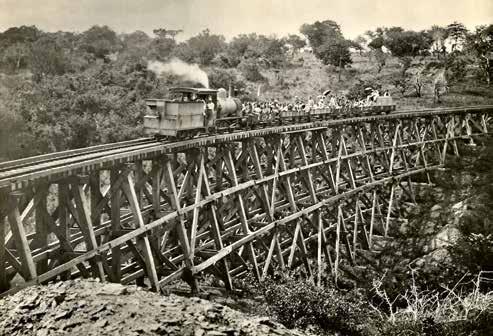

A small party takes the incompleted Uganda Railway to hunt for game near Makindu in 1899.

A teenage Scot jumps ship in Mombasa in 1907 and starts a new life in

A young family takes their home leave from Kenya in 1945 by rail, inland lakes and Nile steamer.

After the elections of 1974, popular MP JM Kariuki becomes more outspoken against President Kenyatta’s government, and his life is

The author traces her grandfather’s role in a Masonic Lodge in Nairobi, trying to understand the allure of this secretive organization.

Cover photo: In the early days of the railway in Kenya VIP guests were often given a cushioned seat on the front of the engine. We are uncertain the names of the riders in this photo. The one on the left seems to be a hunter because of the bullets on his shirt. The photo is from Sue Deverell’s collection. Her grandfather, Alfred Gerald Wright Anderson, and his business partner, Rudolf Meyer, bought the Standard Newspaper from AM Jeevanjee in August 1905 and renamed the newspaper the East African Standard. They took many photos to chronicle that era of Kenya’s history, including this photo.

This issue of Old Africa marks our first magazine where we will not be printing our magazines on paper. It’s a big change for all of us. We do hope that all our subscribers have given their emails to us so we can send an email notice that the magazine is out and to allow them to download a PDF copy. It’s also possible to read the magazine by going to our website (oldafricamagazine.com), but to be able to read it more easily and to increase the size of the font on your computer or tablet, it’s best to read the PDF copy. And, for those who really want a printed out version, it’s always possible to print off the PDF on your home computer printer or at a nearby photocopy centre.

Our letters pages are filled with messages of support from our readers about my recent surgery for cancer. I appreciate everyone’s thoughts and prayers. God is answering. My wife Kym and I came back to Kenya on August 1st for a time of rest and healing before a second round of treatment in mid-September. I have enjoyed the Naivasha sunshine! I continue to heal and I edited this magazine here in Naivasha. But by the time you read this I’ll be back in London for some radioactive iodine treatment to clear out any thyroid cancer cells that might still be lurking, and, hopefully, to have a plastic voice prosthesis placed in my neck, which will allow me to regain my voice.

by tablet!

Not having a voice can be frustrating. Especially when I pull out a small tablet to communicate to someone and they immediately assume that if I can’t speak, I also can’t hear. So they begin to mime and use gestures and whisper, or turn and talk to my wife instead of me. I write on my tablet, “Speak! I can hear. I just can’t talk!” But even that doesn’t always work. What else can I do but shrug and laugh. Thankfully, I can still have a voice through writing and editing and that allows you to read this issue number 121 of Old Africa – even if only in a digital format. God is faithful.

-Shel Arensen, Editor

P.O. Box 2338 Naivasha, Kenya 20117

www.oldafricamagazine.com

Editor: Shel Arensen 0736-896294 or 0717-636659

Design and Layout: Mike Adkins, Blake Arensen

Proofreader: Janet Adkins

Printers: English Press, Enterprise Road, Nairobi, Kenya

Old Africa magazine is published bimonthly. It publishes stories and photos from East Africa’s past. Subscriptions: Subscriptions are available. In Kenya the cost is Ksh. 3000/- for a one-year subscription (six issues) mailed to your postal address. You can pay by cheque or postal money order made out in favour of: Kifaru Educational and Editorial. Send your subscription order and payment to: Old Africa, Box 2338 Naivasha 20117 Kenya. For outside of Kenya subscriptions see our advert in this magazine. Advertising: To advertise in Old Africa, contact the editor at editorial@oldafricamagazine.com for a rate sheet or visit the website: www.oldafricamagazine.com

Contributions: Old Africa magazine welcomes articles on East Africa’s past. See our writer’s guidelines on the web at: www.oldafricamagazine.com or write to: Old Africa magazine, Box 2338, Naivasha 20117 Email

Address: editorial@oldafricamagazine.com. After reading our guidelines and editing your work, send it to us for review either by post or email. (To ensure return of your manuscript, send it with a self-addressed envelope and stamps to cover return postage)

Copyright © 2025 by Kifaru Educational and Editorial All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without prior written permission of the publisher.

Experience an Authentic Safari this Holiday Season at Porini Camps, set in exclusive wildlife locations. Non-residents traveling with residents can enjoy special resident rates for an unforgettable safari adventure.

Porini Giraffe Camp

Porini Amboseli, Porini Mara, Porini Cheetah & Porini Lion Camp

Porini Rhino Camp

Rhino River Camp (Forest Tent)

Rhino River Camp (River Tent)

Rhino River Camp (River Tent)

Porini Ol Kinyei Safari Cottages

Kes 19,500

4,000

Nairobi Tented Camp [Bed and Breakfast Rates] Kes 11,800 CAMP

Kes 26,950

Kes 21,450 Kes 26,950

Kes 18,260 Kes 19,500 Kes 23,760 Kes 26,950 Kes 37,500

Rhino River Camp (Forest Tent) Ground Package

Ground Package

*Enjoy 3 nights for the price of 2 at Porini Rhino Camp, Porini Ol Kinyei Safari Cottages, and Rhino River Camp – your 3rd night is free, with only the conservancy fee payable for that night! Only on new bookings - From NOW until 15th November

Full board accommodation I Free drinks such as mineral water, soft drinks, house wines, beer, and Gin and Tonic. I Guests will enjoy sundowners from scenic viewpoints and guided nature walks I The package also features shared day and night game drives in open 4×4 vehicles with an experienced driver-guide and spotter. I At Porini Rhino Camp, guests will have the opportunity to visit the chimpanzee sanctuary in the Ol Pejeta Conservancy I Those at Porini Amboseli Camp can experience a Maasai village visit I For guests flying in, local airstrip transfers to the camps are included.

Please note, the above rates are excluding park and conservancy fees.

W J Dawson and Fergus Dawson worked with one of the Buxtons growing wheat at Kipipiri in the 1950s. This photo shows wheat combine harvesters in the fields with Kipipiri mountain on the horizon. (Photo by Catherine Dawson)

Members of the Dawson family and guests on the lawn in front of Kipipiri House with the cypress trees and hedges. (Photo by Catherine Dawson)

So sorry to hear of your long battle with health issues. I do hope you get your voice

I want to thank you for your support over many years. You published four or five of my stories over the years. Keep going, in any way you can. We ARE the past and our lives and memories are Important.

Rhodia Mann, Nairobi

Pole Bwana. You have been through quite a journey. But I believe that Our Lord is with us always, and even though we go through times of fear and depression and hopelessness, He will hold our hands to the end. My prayers will be with you and are back in Kenya now. You and your

team at Old Africa have brought back many happy memories. My family and I were in Kenya earlier this year, where our two-year-old grandson jumped across the Equator, patted the backside of a rhino and chased ghost crabs along Watamu beach. We had a good time.

I have Amyloidosis so I am restricted to low altitude, so my desire of seeing my final days out in Nanyuki at the Cottage Hospital have been shelved. Both my folks died out there and it has been my wish to do likewise - ah well… Rory Moss, UK

Dear Editor,

Thank you for the last paper edition of Old Africa, which just popped into our mail box here in the Pacific Northwest, with your note telling of your health challenge.

Both David and I wish you a complete return to health in your beloved Kenya and want to extend thanks for all the work you have done at the magazine, sharing Old Africa stories around the world and giving so much pleasure to so many people.

I look forward to working with you on the digital edition. What a legacy you have created.

Isabel Nanton and David Partridge

Dear Editor,

When a large white envelope with Kenya stamps and Old Africa stamped on it comes through the letterbox (particularly in winter), it is a sunny moment in our lives.

Then I read your editorial and the openness about the current ordeal you are undergoing. How you ever managed to even produce this issue at this time is astonishing, and a tribute to your determination. Nothing now matters more than your health and recovery. Your readers are rooting for you, and I too send every good wish and prayers to you and your family.

Mhorag Candy, UK

Dear Editor,

I was very surprised about the very sad information about your health when I received the last printed Old Africa magazine, yesterday. It is very difficult to understand such bad health news. I wish sincerely good health and as much as possible strength to go throughout your treatment.

If you’re back in Kenya, I think your beloved surroundings in Naivasha are also helping you recover.

I am looking forward getting the digital magazine in November. Old Africa is a great magazine and will be great to read and watch these wonderful memories on my computer. Of course, I always waited patiently for the mail from Kenya with Old Africa and Kenya stamps on the letter! Thank you for all the magazines which I got from Kenya. Upone haraka. God bless you.

Heini Hirni, Switzerland

Dear Editor,

I was most distressed to read of your news in the latest edition of your great magazine. You have had a horribly long time ‘inside.’ Hang in there, and every best

wish for a more comfortable time ahead.

I fully understand the need for changes with Old Africa. When Esso curtailed operations in Africa, I formed a club of Esso alumni with African experience, and we got up to 150 members at one time. We only had an annual newsletter and an annual lunch in London. But numbers fell away for age reasons, and after 25 years we folded in 2019. But it gave some people some pleasure,

You and your team have given pleasure to so many people. To us oldies (I am 95 next week, d.v.!) these memories you revive and expand are very valuable. Thank you. I think my children will keep up an interest in whatever you produce, (they were born in Tanganyika and Kenya) but not, I fear, the grandchildren.

I would like to send a small contribution to help with Old Africa expenses, if that would not be presumptuous?

John Lindgren, UK

Dear Editor,

I admire your courage in coming out so openly with your medical condition while at the same time thanking God for answering the prayers of your many friends.

I have vivid memories of how your magazine first started in 2005 and the tremendous popularity it has gained over the years with you at the helm. This is no mean feat and I feel I speak for all your wide readership when I say you deserve our praise and congratulations.

That you wrote the editorial from your sick bed at the Royal Marsden hospital in

London is highly commendable and goes to show the stuff you are made of.

In wishing you a speedy recovery I assure you of my humble prayers and good wishes. Meanwhile, keep up your infectious spirit and many thanks for bringing back so many near- forgotten memories of our days in Kenya - the land I still love.

Since I have only recently renewed my yearly subscription, can you please accept the unexpired portion as my donation for this term. I shall continue to donate in the future considering how much pleasure Old Africa has given and continues to give me.

Mervyn Maciel, Manyatta, Sutton, Surrey

Dear Editor,

I just received your note with the latest printed Old Africa magazine. I am so sad to learn of your illness and pray that you will heal quickly and be back to your self soon. I will of course sign up for the digital version, but I have loved receiving and saving so many wonderful volumes. With heartfelt best wishes.

Patricia King/Annamaria Alfieri, New York City, USA

Dear Editor,

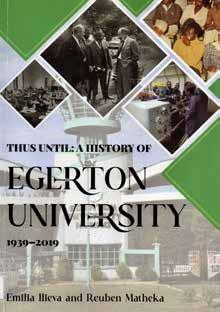

I am returning to our correspondence of 2019. I am pleased to inform you that - at long last - the history of Egerton University has been written. My colleague and I completed the manuscript at the end of 2023. After thorough review and assessment, it was accepted for publication by East African Educational Publishers, the oldest and most authoritative

publisher in East Africa and one of the best on the continent. The book has now come out of press.

We have gratefully acknowledged your assistance in the book. The inquiry that we made and which you publicised through Old Africa, was most productive.

Having read your Editorial in the latest issue of the Old Africa magazine, I wish to say how moved I was by your courage and your devotion to your work as Editor. No wonder Old Africa is the unique publication that it is and one that has played such a stimulating part in the mental and emotional life of many people associated with the past and present of East Africa. You are an incredible model of largeness of mind and spirit. Thank you.

I wish you a full recovery. Having gone through a similar experience myself, I can say that this is possible. The medical advances made in the treatment of cancer are enormous.

It has been something of a miracle that Old Africa has remained in print all this time. So it is perfectly understandable why it has to go online now. This transition need not affect the quality of the publication, nor its appeal. It is, of course, sad that there are so many Returns to Sender. But, then, how else can it be?!

Emilia

Ilieva, Egerton University

Editor’s Note: Thus Until, a History of Egerton University is reviewed by Old Africa in this issue.

Dear Editor,

I received issue 120 of Old Africa earlier today but it’s just now I have read the very touching editorial. May God restore you to full health and bless all who produce Old Africa so it can remain in circulation for many more years. I fully understand your position on the transition of Old Africa to digital format. It’s just that it’s difficult to keep track of the issues and to store them for future reference. I used to buy Parents and other magazines, but when they turned digital I forgot about them. But I will devise a way of sticking with the digital Old Africa

Reuben Matheka, Egerton University

Dear Editor,

Thanks for a great AugustSeptember magazine. I hope that you are doing better and that your health is improving slowly but surely. We pray and wish you a speedy recovery. Here in Njoro the weather is continuing to be cold with an occasional rainstorm. Place is looking nice and green.

I’ve just got back from Watamu where my family and friends gave me a great birthday party, as I turned 80 years old on 3 August. We stayed at Turtle Bay lodge, which was fabulous. We were over 30 people. Kids, grandkids and friends from far as Sweden, South Africa, Tanzania as well as Kenya. George Vrontamitis, Njoro

Dear Editor,

I am afraid the bush telegraph does not seem to get to our part of the world quickly enough as I have only just found out about your fight with this bloody

dreadful thing called cancer. I only knew about this when I collected the Old Africa magazine an hour ago and read your editorial. I was completely taken aback.

Caroline and I would like to wish you the very best and hope the operation has been a success. It must be truly upsetting for you and your family but with your faith in God, I hope your recovery will be quick and complete. You are being treated in a world class institution who I am sure are doing everything possible to get you back to so-called normalcy. Please take care of yourself and our thoughts and prayers are with your family and friends and especially yourself. Stay positive and take care. Andrew and Caroline Mules, Naivasha

Dear Editor,

Thank you for your note that came with issue 120. Fight on to be rid of the terrible cancer. We hope that goes well. You are in our thoughts and prayers.

120 issues is a fantastic achievement. You and the team have brought immense joy and pleasure to many readers, both in East Africa and across the world. You have made a written record of many historical events and stories that occurred over about a hundred years of East African history. A record to be proud of, and I suspect a record that many people in other countries on the continent wish they had too. I’ve sent you my email and I look forward to hearing from you about how to receive the digital magazine going forward. Thank you.

Hugh Back, Norwich, UK

Dear Editor,

Very tough news about your cancer diagnosis. All we can do from here is send every good wish and hope that the amazing advances in medicine over the last few years will work for you in every regard.

We have certainly enjoyed the Old Africa issues we have had, and only regret that we didn’t know about the magazine sooner.

There is one tiny story about it that might amuse you. I went to a new barber a few years ago and discovered that there were no magazines to browse as I sat and waited my turn. When I got to the chair I asked Howie, my barber, about that. His response? “Oh, my magazine guy died.” I offered to bring some and he said, “Great, I’ll cut your hair for free.”

Old Africa was a one of the set of half a dozen titles I took each time. A few visits later he told me had some new customers at the barber shop after one expressed his delight at seeing your Old Africa magazine. This man, from Kenya, had told his friends about it and two new men had come along to the barber shop just because of the opportunity to read the stories in Old Africa !

I’m sure you have my email on file for the new transmission system. It’s sad to realize that our love of hard copy, something to hold, is taking yet another hit. In this case it’s understandable, but nonetheless sad.

Dr Jerry Haigh, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada

Dear Editor,

How I love the printed copies of Old Africa magazine! I belong to the old school.

Pole sana, Shel, kwa ugonjwa. I wish you quick recovery and great health to allow you serve us for many years to come. Here’s my email. Share the access details to the Old Africa online version.

Tanui Paul, Nairobi

Dear Editor,

I have been so saddened by your news and sincerely hope that your surgery and subsequent treatment proves successful. Like most of your subscribers of my age group, I’m sure, I am disappointed that your wonderful magazine will now be digital but completely understand the need to go that route. As you must know, and have been told countless times, your publication has brought enormous pleasure and interest not only to those of us here in Kenya but also many others around the world. That said, good luck with your new digital version during the next year and if it becomes too demanding an exercise we must just simply say, “Thanks for the interest and memories we have all enjoyed up until now.”

Incidentally, there are many of us doing charitable work across Kenya – especially in education - who are struggling to keep going as the costs have skyrocketed, fundraising is becoming beyond us and we, too, are getting older. Sadly, as well we all know, in spite of what the Powers That Be say, it continues to be a case of the rich getting richer and the poor poorer, but we

have all done our best in our own small ways.

Pop Gunson, Karen, Kenya

Dear Editor, Thank you for yet another wonderful issue of Old Africa. When I saw it in the store the other day, I immediately picked up a copy and finished it in one sitting. I have been reading the magazine regularly for only two years, but I must say this was one of the most beautifully crafted issues so far.

I was saddened to read about your health challenges. I wish you strength, a full recovery, and improved health in the days ahead. It is inspiring that you continue to contribute to Old Africa during such a delicate time. I am 35 years old and have lived in Kenya for the past 8 years, and I would be deeply saddened seeing Old Africa cease publication. I would like to subscribe to the next year immediately - copying Blake here so he can kindly guide me through the process.

I understand you are considering moving to a fully online version, but one of the things I love most about Old Africa is the printed format. Reading it on paper - in the evening, or after a long day at work - offers a completely different and much more enjoyable experience than scrolling on a phone after a day in front of a screen. If you ever reconsider or decide to keep printing at least a limited number of copies, please know I am happy to support Old Africa however I can. I would gladly volunteer my time or contribute in other ways to help make it possible.

Riccardo Zennaro, Nairobi

by Karen Rothmyer

Several years ago, while editing a memoir written by Agnes Shaw, a Kenyan white settler and elected member of the Legislative Council, I interviewed her one-time Sotik neighbor Patrick Walker. Walker was well-acquainted with many farmers throughout the white highlands during the late colonial period because of his work for a property firm in Nairobi.

I asked him whether he thought there had been any serious possibility in the years before Kenya’s independence in 1963 that the white settlers, faced with the prospect of black majority rule, might have declared Kenya’s independence from Britain in much the same way as white Rhodesians did in 1965 with their UDI (Unilateral Declaration of Independence). As is clear in Shaw’s memoir, the Kenyan settlers’ anger at the British government over what they saw as its readiness to renege on earlier promises that Kenya would forever remain a “white man’s country” was at a high pitch at the time.

Walker paused to consider the question, then answered in carefully chosen words. “Amongst the farming community in the white highlands, I suspect there was much more support than anyone ever admitted,” Walker said. “I think given the opportunity they would have done so.”

Godfrey Muriuki, a retired University of Nairobi history professor, confirmed Walker’s sense of the mood among the settlers in a recent email exchange. “I lived in Mweiga among them during my school holidays in the 1950s, which afforded me the chance to interact with them,” he wrote. “I vividly recall that settlers in Kenya were definitely mooting the idea of emulating those [who later declared independence] in Southern Rhodesia.”

In the end, though, the white settlers in Kenya didn’t rebel. A review of memoirs and documents of the time reveals heated rhetoric and widely expressed loathing of Whitehall but no actual steps toward that end. (Of course such actions would have been regarded as traitorous, making it unlikely that anything explicit would have been committed to writing.)

But what is nonetheless revealing—

Shaw (second from left in the back row) along with other European elected members of LegCo in April 1952. When tensions were high over Kenya’s upcoming independence, she cautioned her constituents against a white-led rebellion against Great Britain and sided with Michael Blundell (front right in this photo) in steering Kenya to independence as an African-led country. (Photo from Kenya Kaleidoscope)

shocking, really—about such a review is the evidence it provides of the settlers’ repeated threats of rebellion throughout Kenya’s colonial history, and of how much encouragement they received. Edward Grigg, a one-time governor of Kenya and a whole-hearted supporter of the settlers, recalled the American Civil War in a Parliamentary speech in the 1940s in which he warned that if the British government didn’t show more sensitivity to the Kenya settlers’ concerns, “It is not impossible that bad handling of this problem would, in the end, produce the same consequences in Africa.”

What would have happened if Kenya’s white settlers had declared their own version of Rhodesia’s Universal Declaration of Independence—the decision to break all ties with Britain—is hard to say. It’s unlikely that the whites would have met with implacable opposition from London, backed by military force, as was the case in the American colonies in 1776. Instead, they might they have discovered, as the whites in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) did during 14 years of white rule following UDI, that the British government did not want to embark on an expensive undertaking that would be made even more

unpalatable by the need to send white troops to fight white settlers. Meanwhile, Africans in Kenya would undoubtedly have fought for a black-led version of independence, as they did in Rhodesia.

One thing is certain: if Kenya’s whites had officially broken ties with London, Kenya’s history would be even more bloody than it already is.

Throughout most of the colonial period, both the white settlers in Kenya and the home government in London assumed that the colony would eventually become selfgoverning—with whites in charge. According to Elspeth Huxley, who wrote extensively about her Kenyan childhood as well as the country’s politics, “the idea behind white settlement was to found a British colony on the South African or Australian model, which would grow until it became large and strong enough to win selfgovernment, as the Dominions have done.”

‘Dominion’ referred to complete or nearly complete internal self-government but with the English monarch still the head of state. Australia and New Zealand achieved Dominion status early in the 20th Century, made relatively easy by the fact that the vast majority of their original non-white inhabitants had been wiped out by disease. South Africa, where whites were a minority, but a substantial one at over 20 percent, achieved the same status shortly thereafter.

More analogous to Kenya was Rhodesia, which became self-governing to a significant degree in 1923. This occurred despite the fact that there were at the time only about 40,000 whites compared with roughly one million Africans. As cited by British academic Margery Perham in Race and Politics in Kenya, white proponents of self-government in Kenya used this fact to argue that there was no reason that Kenya, whose white population never got higher than about 62,000, could not do the same.

The proponents of a Dominion in Kenya also offered one promising proposal to those concerned about the small number of whites: to link up with the white settlers to the south. In 1942 Lord Francis Scott, a member of Kenya’s Legislative Council, said that “there is only one right and proper future for these territories in East Africa and that is that we should all be

joined from the Limpopo [which rises in South Africa] to the Nile in one British East Central African Dominion.”

Scott’s vision never came to fruition (although for a decade, starting in 1953, there was a federation of what are now Zambia, Zimbabwe and Malawi), but for years it retained considerable white appeal. It was, after all, to Rhodesia and South Africa that Kenya’s whites looked for models and encouragement. Many of Kenya’s early settlers came from South Africa, while Governor Grigg grew up there and Governor Robert Coryndon, his predecessor, was born there. White Kenyans took many of their cultural cues from South Africa, enforcing a colour bar that prevented Africans from entering many establishments or even being present in downtown Nairobi without a pass. The American writer John Gunther, who visited Kenya in the mid-1950s, noted in Out of Africa that “die-hards talk on occasion of ‘secession’ from the Commonwealth. They will make a Boston Tea Party, throw off the ‘yoke’ of London, and fight a white settlers revolt as George Washington did. Then will come the establishment of a straightout white supremacy

In 1942 Lord Francis Scott, who had a farm in Rongai and was a member of LegCo, pushed for a white-led British East Central African Dominion that would have stretched from “the Limpopo [which rises in South Africa] to the Nile [which has its headwaters in Uganda]. (This cartoon by Colonel CM Truman first appeared in the Tatler on 12 July 1939. It was later republished in Old Africa issue 68 (December 2016-January 2017

state, with no nonsense about it, like that in the Union of South Africa.”

The first white threat of rebellion in Kenya occurred in 1923. This was after the Devonshire Declaration was adopted, reaffirming the restriction of land grants in the white highlands to Europeans, which the settlers applauded, but also putting forward a proposal to establish a common voters’ roll for European and Indian voters, which they did not. As Grigg describes it in his memoir, “The settler community responded with a highly unorthodox threat to capture the Governor [Coryndon] and hold him prisoner till the Order was withdrawn.” He notes that the governor “had no organized force behind him other than a battalion of King’s African Rifles with English officers,” whose willingness to attack their fellow Englishmen was open to question. C S Nicholls writes in Red Strangers that Coryndon received information that the settlers had plans to take over the railway and the radio station in Mombasa, and they had enough skilled people in their ranks to run the colony’s institutions.

“Downing Street capitulated,” Grigg writes. Or, as the late Ronald Robinson, professor of Global and Imperial History at Oxford, put it in an essay, “The colonists were pointing the pistol of rebellion at the Colonial office, not for the first or last time.”

political power to Africans, CB, a top leader of the diehards who wanted whites to continue to lead Kenya, resigned his post as Speaker.

After a report in the late 1920s advocated more rights for Africans, “Once again there were serious risks of risings and secession to South Africa,” according to Robinson. He referred in a 1988 lecture to a half-dozen incidents in which the British Cabinet decided “to avoid the risk of a settler revolt at all cost” by giving in to settler demands.

In 1935 The Round Table journal, an offshoot of a movement to promote closer union between the United Kingdom and its colonies, asked a leading white settler from Kenya to give the white community’s views. Throughout the unsigned article, the tone is hostile to London’s rule. Noting that the settlers have recently formed a “Colonists’ Vigilance Committee,” the author warns that “There will be no peace in Kenya” unless the settlers are given more power, and without significant changes “it is almost certain that some major incident will occur in Kenya before long.”

Throughout the rest of the 1930s and most of the 1940s, however, first the Depression and then the Second World War produced a period during which London made no serious challenges to increasing settler power and the settlers didn’t push as hard as they had earlier on the issue of self-government. This did not this mean, however, that the settlers were softening their opposition to rising African demands. “By 1942 it was still too hazardous to override the Europeans for the sake of advancing native interests,” Prof Robinson said in a 1988 speech. Moreover, according to Robinson, by the time the war was over, England was “heavily in debt to, and dependent on, the colonies,” giving the settlers yet more leverage. “Far from the imperial dog wagging its white colonial tail, the white colonial tail was wagging the imperial dog. Such were the historical odds in favour of the colonists taking Kenya and the Rhodesias to independence under white minority rule, as calculated in a Colonial Office policy study in 1948.”

This same warning was included in a memorandum prepared for the British cabinet in 1951 by Patrick Gordon Walker, the British Foreign Secretary. As recounted in The Lion and the Springbok, Gordon Walker stated in the memo that “in the last resort the British government had no real power to control” the settler communities in Kenya and the Rhodesias, adding that “Certainly Britain’s power on the spot would be found inferior to

South Africa’s.” The authors also quote Gordon Walker as saying that if Britain allowed the impression to be given that it was committed to a policy of subordinating whites to Africans, “Rather than face that, the whites will in the end revolt.”

That this was no idle threat is indicated by Michael Blundell, one of the top white settler leaders in Kenya at the time. In his memoir So Rough a Wind, he writes that the Europeans made it clear to Whitehall that if any sweeping political charges were imposed against their wishes, these “would be resisted, even to the extent of unconstitutional action. What this action would have been, we had not worked out; but I remember telling a meeting at Naivasha that we were very determined on the issue, and, if necessary, would rebel.”

There things stood in 1952, when African freedom fighters burst upon the scene in Kenya, murdering several Europeans as well as Africans who supported the colonial regime. This led a few months later, in January of 1953, to a march of up to 2,000 white people to Government House (now State House), demanding stronger security measures. As recalled by Blundell, the whites were so angry at not being given access to the governor that they stubbed out the ends of their lighted cigarettes on the bare arms of the African askaris trying to guard the doors. “I saw in front of me a little woman dressed in brown who was, in normal times, the respected owner of an excellent shop in Nairobi,” Blundell recalled. “She was beside herself with fury and crying out in a series of unprintable words, ‘There, there, they’ve given the House over to the f….niggers, the bloody bastards.’ Unknown to me, the Sultana of Zanzibar, who was staying at Government House, had incautiously come out on to the balcony above the doors to see what was happening.”

By the following year, some of the most extreme right-wing settlers had organized the White Highlands Party, one of whose leaders was a Nairobi businessman called L E Vigar. According to D H Rawcliffe (whose book The Struggle for Kenya, published in 1954, was banned in Kenya) Vigar had openly declared that his supporters “would seize political control of the country by force of arms if the British government persisted in its aims of furthering African and Asian political

development. He stated that in the last resort he would be prepared to invite [South African Prime Minister D F] Malan to send South African troops to Kenya and hinted that Malan had already made an offer in this direction.”

The next few years saw Kenya’s white population heavily involved in the struggle against the black freedom fighters who came to be known as the Mau Mau. And when it was over (effectively, by the end of 1956), little if anything in their thinking had changed. British journalist and historian Basil Davidson wrote in Africa South magazine in 1957 that the objectives of the Europeans in Kenya remained “to shift responsibility for Kenya from Whitehall to Nairobi” and “to build into any conceivable future constitution a cast-iron guarantee that they, the Europeans, shall remain the real government of the country.”

One thing that had changed was that white Kenyans had become a battle-tested military force. Virtually every able-bodied white man in the colony became part of the army or police during the Emergency, with about 1,800 men serving in the Kenya Regiment and many more in the police and police reserves. It might be supposed that such fighters would be no match for trained British troops, but it’s worth recalling that American colonial forces were far from equal to the British Redcoats during the American Revolution either, and yet in the end they and their cause prevailed.

Another change, however, this one not in the settlers’ favor, was that the Emergency had taken a huge financial toll on the colony. Whereas the Kenyan economy had been strong coming out of WWII, historian Gerald Horne notes in Mau Mau in Harlem? that the colony had to borrow

Elspeth Huxley in 1935.

(Photo from https://www. europeansineastafrica. co.uk)

14 million pounds in one year alone from the British exchequer. Rawliffe claims in his book that “If the Mau Mau rebellion had been brought to an end within the first nine months of the emergency, it is certain that the settlers would have gone all out to obtain self-government at the earliest practical moment in order to break the restraining link with Whitehall. But Mau Mau resistance continued, necessitating further military aid from Britain and greatly increasing the colony’s financial dependence on the home country. As a result, the clamour for immediate self-government has considerably abated.”

Perhaps the most important thing lacking among the white settlers in Kenya was effective pro-independence leadership of the sort that Ian Smith provided in Rhodesia. Smith may have been stubborn and humourless, as well as a racist who said he didn’t believe in black majority rule “not in a thousand years,” but he skillfully managed Rhodesia’s economy and effectively promoted the Rhodesian cause—for example attracting fawning groups of several hundred Americans to 1978 events in New York and Los Angeles.

In Kenya, the ‘diehards’ were definitely vocal. E L Howard-Williams, a legislator and settler leader, issued a public call for a “show down” between “Kenya’s European settlers and the colonial dictatorship which rules us” in a column in the weekly Comment (cited in a 2007 unpublished master’s thesis by Pius M Nyamora), a publication described by Rawcliffe as “almost fascist in its outlook.”

But their abilities didn’t match those of Blundell, an astute farmer-turned-politician. Blundell, seeing the ways in which political opinion in Britain were changing, shifted from saying in 1957, as quoted by Davidson, that

“we are opposed to any scheme…which might go so far as to deprive Europeans of leadership and control of the Colony as a whole” to acquiescing in 1960 to major Constitutional changes demanded by British officials at a conference in London that began transferring political power to Africans.

Agnes Shaw, a Blundell supporter, recalls in her memoir that upon the Blundell group’s return to Kenya from that conference, the diehards made their feelings clear. “Poor Michael!” Shaw writes. “To the accompaniment of cries of ‘Traitor!’, thirty pieces of silver were thrown at his feet as he walked towards the airport building.” A few days later, Sir Ferdinand Cavendish-Bentinck, a top leader of the diehards, resigned his post as Speaker, which Shaw says “was hailed by the great majority of European settlers as a noble and selfless action…Like drowning men, the shocked and badly frightened settlers clung to ‘C.B.’”

But Shaw writes that she told her constituents that at that point, “to talk of armed resistance was crazy. What a handful of early settlers had done in the 1920s was not possible today.” And reluctantly, many agreed, spurred in many cases, according to Prof Muriuki, by practical concerns. “Above all, quite a number of them were well connected to the British aristocracy. A UDI would have endangered their investments,” he writes. “This would have led to serious internal divisions that might have led to an immediate scuttling of such a venture.” Those whites who could not abide the idea of being ruled by blacks began to leave the country, and those who stayed learned to accommodate to the new realities.

If Kenya had declared UDI in the late 1950s or early 1960s, facing the same conditions as Rhodesia later did, there are reasons to think it could have survived for at least some period of time. Rhodesia, after all, managed to thrive economically for 14 years despite an economic embargo, and it was a landlocked country. British military force would almost definitely not have been used: Robinson noted in his 1988 speech that Arthur Dawe of the Colonial Office had declared a decade before that it was “unthinkable” that any British government “would bring military force to bear upon a community of our own blood.” South Africa would have done what it could to assist, if Vigar

Cavendish-Bentinck (left), Tom Delamere and David Bowden meet to discuss Jockey Club business in Nairobi in independent Kenya in the mid-1960s. Tom Delamere was one of the first from the white settler community to take up Kenyan citizenship after independence. Despite CB’s earlier opposition to African-rule, he remained in Kenya until his death at the age of 92 in Nairobi. He was buried in Dorset, England. (Photo from And They’re Off!

100 Years of Racing in Kenya)

is to be believed, while America would most likely have sat on the sidelines, its fears about Communism trumping any sympathy for rising black nationalism. And white supremacists from around the world might well have flocked in as volunteers, as hundreds did in Rhodesia. But in the end, it seems clear, Kenya would

not have been able to sustain itself for long as a white-run state. The tide of history was running the other way, and black Africans were on the move throughout the continent to wrest back control of their countries. Black freedom fighters in Kenya, even if temporarily subdued, would have risen again and provided more martyrs to the cause that had already claimed thousands of lives.

Nonetheless, the allure of a white ‘promised land’ in darkest Africa still lingered. Agnes Shaw talks late in her memoir, which ends in 1964, about her regret at the passing of a “way of life of a bygone age.” In Kenya, she writes, “we had been fortunate in that we had been able to preserve this delightful way of life longer than in most places in the modern world.” Delightful, indeed, for white people, but preserved at great cost to the country’s black inhabitants, and apparently not delightful enough to risk dying for.

Karen Rothmyer lived for many years in Kenya, first in the 1960s and later in the 2000s. She is the author of Murumbi: A Legacy of Integrity and was the country’s first public editor, at The Star newspaper.

by Judith Chapman and Chris Durrant

Our grandmother, Dorothy Wynn, then just 20 years old, set sail with her brother William Charles Wynn, 4th Baron of Newborough, in his Steam Yacht Fedora from Portsmouth in southern England in November 1897. They sailed for the Far East, going down the Suez Canal and the Red Sea and then across the ocean to Burma where the siblings spent some months with their elder sister Mabel, married to an officer in the Burma Police. In January 1899 Fedora left Singapore on her journey home, sailing directly west to the coast of East Africa before going south to round the Cape of Good Hope. Both Dorothy and a young member of the ship’s 25-man crew, Henry Barnard, the son of Fedora’s Captain, Turner Barnard, about the same age as she was, kept journals of this part of the voyage. We used both journals to extract a very personal record of the journey.

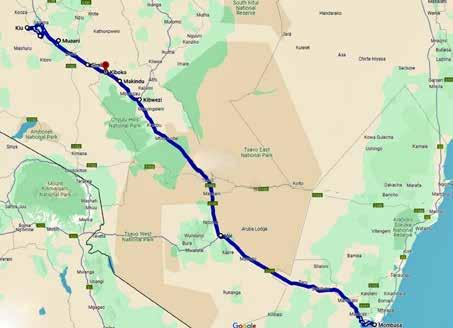

In March 1899 they docked in Mombasa, from where the railway to Uganda was under construction. The Fedora spent just over a month there, while the Wynns, Willie’s valet and the yacht’s doctor travelled about 250 miles up the railway, camping in the bush and hunting a variety of wild animals. This is a summary of this part of their adventure.

Work had begun in 1896 on the Uganda Railway, a slightly misleading title, since it did not take travellers to modern Uganda, but only to Port Florence (soon known by its original name of Kisumu) on Lake Victoria in Kenya.

Progress on the railway was quite well advanced by the time Fedora sailed into Mombasa harbour on 9 March 1899 and at that time was not far short of Nairobi, reached in May 1899. Despite the swampy nature of the land there, the railway authorities decided that it would be a

suitable place for the main administration office, given its temperate climate and reliable source of water from the Nairobi River running through the swamp.

The construction of the railway, through wild and inhospitable country, threw up huge challenges. Perhaps the major one was labour. Over 36,000 men were recruited, mostly from that part of British India which is now Pakistan. Most of these were repatriated to their homeland at the end of their contract, but a significant minority elected to remain in East Africa and sent for their families to join them.

Not all the imported workforce either made it back to India or settled in the Protectorate. The casualty rate was extremely high –deaths of the order of about six for each mile of line laid down – the main causes being sickness and accidents. There was, however, one

cause of death among those working on the railway that, although it accounted for only a tiny proportion of the whole toll, got a great deal of unwanted publicity at the time and undoubtedly spread great terror among the workers – man-eating lions! The most notorious of these were brought to a wider public by Lt-Col J H Patterson in his 1907 book The Maneaters of Tsavo. Patterson was a distinguished soldier and an engineer who arrived in the Protectorate almost exactly a year before Fedora did. He had been appointed by the Foreign Office to the staff of the Uganda Railway to use his engineering skills to help solve the considerable practical problems of laying the line. The first of these for him was the construction of a substantial bridge over the Tsavo River which Patterson describes as “a swiftlyflowing stream, always cool and always running…(with a) fringe of lofty green trees along its banks.” When he got there, the railhead had just reached the riverbank and thousands of workmen were already encamped there. He had not been there long (March 1898) before reports came in of workers taken from their tents at night by maneating lions. A reign of terror began which lasted for several months and at one stage held up work altogether for three weeks. The lions responsible, two maneless males, were cunning and determined and initially evaded all efforts to shoot or trap them. In the end Patterson himself brought them both down at considerable personal risk which included spending

several hours one night on a very flimsy platform while one of the man-eaters prowled and growled beneath him. The lions may only have actually killed about 30 people, but the terror and inconvenience caused were out of all proportion to that.

They were not, of course, the only man-eating lions around – the day after her arrival in Mombasa, Dorothy recorded: “Man-eating tiger killed within three miles by poisoned arrow by a native,” (her zoological knowledge at that stage was evidently patchy) while the next day Henry noted: “There have been two men killed close here this last week by lions, one European and one native. They say there are plenty of lions a few miles inland.”

The following day Dorothy writes: “Mr O’Hara killed by a lion. His remains brought down today.” The hapless Mr O’Hara was a road engineer who was snatched by a lion from his tent beside his sleeping wife and taken to be eaten in the adjacent bush.

The fact that Fedora’s passengers were prepared

to venture into the wilds of the East African bush in spite of these hazards says something for their courage and enterprise, although the day she recorded the killing nearby of the ‘man-eating tiger’ Dorothy did say that she had spent the whole day on board, despite it being “very hot. No breeze.” Dorothy actually records having heard lions while they were at Simba. “Heard lion roaring close by while at dinner.” In conversation many years later, her daughter Alice told one of the authors of an actual encounter Dorothy had with a lion. “Well, all she ever said was ‘oh, I was out sketching,’ I think, and I took it that they were sitting under a tree in the shade and so was the lion. She told me ‘it was very lucky he wasn’t hungry.’ So, I imagine they were sharing a bit of shade with a lion which they hadn’t realised was there. Well, they probably wouldn’t have seen it lying in the long grass.”

Patterson, in his book, also relates the tale of another man-eater who set himself up near the small station of Kima, some 50 miles short

of Nairobi, in mid-1900. As we shall see, the Fedora party had passed through Kima the previous year on their way up the railway from Makindu to Kiu. A Police Superintendent, Mr Ryall, passing through the station with two visiting European friends, decided to set a trap for the lion in the carriage in which he was travelling. The three men took it in turns to keep watch but, when the last man, Ryall, concluded that the man-eater was not going to put in an appearance and turned into his bunk, the animal, which had obviously been waiting for this, broke into the carriage and carried off Ryall. The other two men, miraculously, got away unharmed, physically at least. One, sleeping in the upper bunk, had to scramble over the lion to get to the door through which he could escape. The other, sleeping on the floor (there were only two bunks in the compartment), had the lion standing on him while it sank its fangs into poor Ryall, lying in the lower bunk, and had to remain there in terrified silence until the lion departed from the carriage through the window with his friend

in its jaws. Not long after, the killer was caught in a trap made by railway staff. Patterson writes: “He was kept on view for several days and then shot.” That railway carriage remained on display at the Nairobi Railway Station some 60 years later. When we (Chris and Judith) as children caught the overnight train to the coast for our annual holiday, great excitement, anxiety and storytelling arose from viewing it.

The Fedora had arrived at Mombasa in early March 1899 and moored, Henry tells us in his journal, “in 18 fathoms of water with two anchors and 30 fathoms of

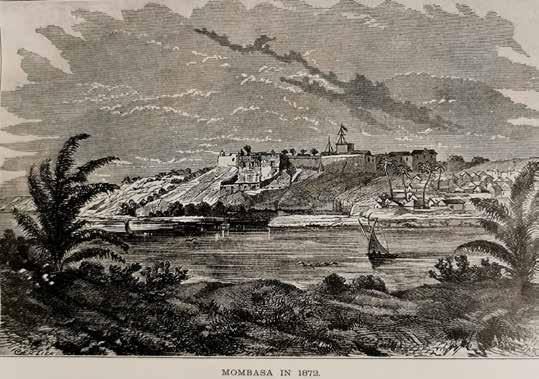

chain on each.” This was in the traditional harbour on the eastern side of the island, by the old town and under the battlements of Fort Jesus, built by the Portuguese over 300 years before. This magnificent structure, described as a masterpiece of late Renaissance military fortification, was designed at the order of the Portuguese King Felipe by the Italian architect Giovanni Cairati and exists to this day.

Dorothy’s description was hardly effusive: “Quaint ruined looking place perched on a rock. Pretty harbour.”

At the time of Fedora’s visit, Fort Jesus was being used by the British authorities as a prison, which would explain why Dorothy did not visit the Fort during her time in Mombasa. Fedora initially dropped anchor in the old port, where dhows and other sailing ships using the port would have tied up, and remained there for most of her time at Mombasa. However, this harbour was quite unsuitable for unloading the sort of large building materials needed for the construction of the railway, so a new port had

recently been constructed on the other side of the island at Kilindini. There was a natural deep-water harbour there and far fewer buildings, so much easier to access the waterfront.

This was where the railway terminus was constructed, together with a pontoon bridge to take the trains off the island. A much grander bridge, to be named the Salisbury Bridge, after Lord Salisbury, the British Prime Minister at the time, was under construction and was opened four months after Fedora left Mombasa. This bridge was renamed the Macupa Bridge before it was replaced some 30 years later by the Makupa Causeway, now spelled in the proper way. Fedora remained in the old port for most of her stay at Mombasa but moved round to Kilindini a few days before the hunting party returned to facilitate the transfer of a substantial stock of trophies as well as drawing water from the railway’s condensation

plant Henry commented: “Breconshire, merchant steamer, has been laying here for about 3 weeks discharging railway materials for the railway that is being laid by the English Government from Mombasa to Uganda. They have laid nearly 300 miles already.”

Dorothy discovered that

the main means of getting around the island, at least for the upper classes, was the gharri, a small trolley running on two-foot railway lines laid all over the island, pushed by two strapping local men. This arrangement is said to be the first railway constructed in East Africa! At least until the late 1950s, hand-carts,

simple trolleys powered by two men standing on the front and back, either side of a couple of passengers sitting in the middle, could often to be seen pumping along the main railway surprisingly quickly. They were propelled by the two men alternately pressing down a hinged shaft connected by gears to the driving wheels. They were a handy means of carrying out inspections on the line and its infrastructure. Being quite light, they could be lifted off the line by their passengers if necessary to let a train through.

The reason for Fedora’s visit to the East African mainland was very clear –hunting! The day of their arrival in Mombasa, Henry, who had to stay on the ship with the rest of the crew, noted: “company going on a shooting expedition for a week or two from this place.” The next five days were evidently spent preparing for this safari, although you would know this only from Henry’s journal. Dorothy speaks merely of the people she had met, notably a Mrs Boustead

whom she described on different occasions as “rather pretty” and “very jolly,” and some walks and excursions around the island, including travelling to Kilindini on the trolley. The men of the party would have been occupied hiring the necessary servants and equipment and presumably finding out exactly where they could go and how they could get there. Fedora and her crew naturally remained at Mombasa, and the nearly four-week safari was the only time in the whole voyage when the crew and the “company,” as Henry invariably called them, were in completely different places. For that period alone, Dorothy’s and Henry’s accounts are not describing the same events.

Early on the morning of 14 March, the Wynns (Dorothy and her brother William whom she refers to as Willie or N in her diary), Dr Jennings, and Mr Robert Morbey, Willie’s batman, took the trolley to Kilindini to board the train. According to Dorothy, they were accompanied by “Headman,

four Somalis & cook” and at the station at Mazeras, a short distance out, they “picked up 60 coolies,” though these were presumably to work on the railway and not in their personal service. They reached the small town of Voi, some 100 miles from the coast, in the early evening. Dorothy notes: “Saw lots of gazelle & two big Antelopes. Very Dusty. Pretty place in the hills.” Here they spent the night, presumably in the train, before continuing their journey early next day.

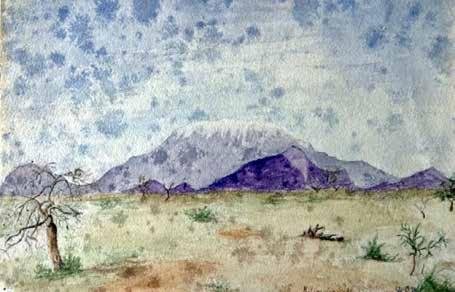

Between Voi and their next stop, Makindu, some 200 miles from Mombasa, the Wynns had their first view of the snow-covered peak of Kilimanjaro, 60 miles to their west, just within the boundary of German East Africa. On their way to Makindu, they passed through what became, 50 years later, the Tsavo National Park, today one of Kenya’s premier game reserves, and began to see many more animals in the bush. Dorothy’s knowledge of East Africa’s wild inhabitants was evidently improving, although she did record having

seen a mouse deer, which is not a creature found in East Africa. She may well have seen mouse deer in Ceylon or Burma, but on the train from Voi what she probably saw was a tiny antelope called the dik-dik which looks similar to the mouse deer. She was also intrigued by the local humans, quite different to those whom she had encountered on the coast. She recorded that they “wear rows of beads in their ears & Grass rings. Most of them half starved. All close cropped hair.” In fact, people she saw probably were halfstarved as East Africa was in the final stages of a series of natural disasters. An outbreak of rinderpest (a severe cattle disease), a smallpox epidemic, and a plague of locusts had been followed by the complete failure of the rains in 1898 which led to a serious drought. However, Dorothy mentions rain on at least three days during their safari and the record shows that 1899 saw excellent rainfall, with the heaviest as usual in March and April.

Beyond Makindu they passed through the

appropriately named station of Simba (‘simba’ is Kiswahili for ‘lion’) and, as mentioned, the siding at Kima where, a little over a year later, the unfortunate Superintendent Ryall met his end as a lion’s lunch. Finally, on 16 March, they reached Kiu where the adventure was to begin in earnest. Dorothy records: “Country very bare, no trees. Herds of antelopes, Buffalo, Zebra, Ostriches - arr Kiu 1.20 p.m. Pitched camp on hill.” Having arrived in ‘big game’ country, no time was wasted: Dorothy tells us that Willie and Dr Jennings left the next day at 6 am to hunt for game.

For the next three weeks, hardly a day went by without some wild animal being ‘bagged,’ often several species. Dorothy’s part in this was mainly as a spectator and recorder, though she did occasionally go out herself. On 27 March she says she shot two wildebeest. Her diary entry concludes: “enjoyed the day immensely. But rather tired.” Clearly her knowledge of African wild-life advanced by leaps and bounds: from

describing a man-eating lion as a tiger and a dik-dik as a mouse deer early in the journey up the railway, she progressed to being able to identify two species of gazelle (Thomson’s and Grant’s) and even differentiated between two sub-species of hartebeest antelopes (Coke’s and Jackson’s).

She also spent time sketching, on more than one occasion, the snow-clad splendour of Kilimanjaro, and the camps where they stayed at Kiu, Kiboko and Makindu. Only one of these sketches survives. It shows the intense sparseness of the scrubland due to the heat, the dry climate and the red tones of the earth. In the picture, much of the mountain, the highest in Africa at 5,899 metres (19,354 feet), was prolifically snow clad. In recent years, as a result of climate change, the ice fields and glaciers have shrunk and are predicted to disappear altogether between 2025 and 2035.

One of the things that is quite interesting about this episode is the apparent ease with which the various animals were added to the trophy list. As far as we know, neither Willie nor Dr Jennings had any big-game hunting experience. Willie would doubtless have spent many mornings since his youth blasting pheasants, partridges, and snipe out of the Welsh skies, but this is hardly the same thing as setting out into the African bush in pursuit of lions or rhinos.

The party had been joined by George Whitehouse, Chief Engineer or “head of railway” as Dorothy called him, who seems to have been a regular

William ‘Willie’ Wynn shot a lion

visitor throughout their safari, and it is likely he would have given them useful advice. However, it is still remarkable that, on that very first day, according to Dorothy, “Dr J got Thomson’s Gazelle, a lioness & rhinos two horns” and the next day, Willie got two rhinos and Dr Jennings got hartebeests. The two factors in the hunters’ favour would undoubtedly have been the massive proliferation of the game animals, and the fact that they were relatively unaccustomed to being hunted. The plains on which they roamed were not heavily populated by humans, so the most they would have had to put up with was the occasional tribesman with poisoned arrows hunting for the pot. Animals like lions, rhinos, and elephants did not fall into this category, and so would have had very little disagreeable contact with human beings until big game hunting took off in the early years of the 20th century. Dorothy does not mention elephants in her record of the safari, so presumably they did not see any. Not all the animals they did see found their way into the trophy cabinet – buffalo, impala and hyena all escaped, though not

always for want of trying. On 31 March Dorothy records that “N [Willie] went to native boma to wait for hyena by moonlight but didn’t see it.” Why he wanted to shoot a hyena, one can only speculate.

After five days in camp near Kiu, the party moved back down the line to Simba where they camped about half a mile from the station. The Wynns travelled in a railway carriage, but Dr Jennings elected to go by trolley, which gave him the opportunity of bagging another Grant’s gazelle.

They camped near Simba for about ten days. One gets the impression, reading the diaries, that the planning of the hunting expedition was somewhat ‘ad hoc’.They could do that, of course, because they did not need to consider boat departure schedules as they were providing their own transportation. Henry’s diary, a few days before the party left on the train for Kiu, told us: “Company going on a shooting expedition for a week or two from this place.” By the time they got to Simba, however, it was obviously going to be a bit longer than that, with Henry recording that he and the second mate had gone ashore and travelled

to Kilindini by tramway “to send off some ammunition to his Lordship, who wired down from Simba for them. We walked back as there was not a tram leaving at the time.” This was not the last time additional supplies were called for. Just over a week later, Henry writes: “Captain had a telegram from Dr Jennings asking him to send him some more cartridges, so the mate took them on shore to pass the customs and then sent them on to a place called Kiboko.” Leaving Simba on 30 March, they travelled further down the line to the little station at Kiboko (Kiswahili name for hippopotamus but also given to the whip or cane made from hippopotamus hide). Here, says Dorothy, they pitched camp “at 1.30 under the trees…close to swift river. Fished with pin & cotton, plenty of fish. N [Willie] & Dr J went out & got nothing. Lovely sunset & view of Kilimanjaro.”

The following day, which was Good Friday, Dr Jennings walked downstream to catch up with a Mr Ellison who was obviously encamped some way away. As he subsequently informed them, the good doctor narrowly escaped a rhino! He was

not the only person to have had a brush with death: the previous day Dorothy notes: “Coolie charged by rhino.” Presumably he also escaped.

On Easter Saturday she records that they had decided to go on to Makindu on Monday and then from there to Athi River, a reasonably substantial station another 50 miles or so closer to Nairobi. The first part of this plan was put into effect. Joined by Dr Jennings, returning just in time from his rhino-dodging exploits, they travelled the short distance down the line to Makindu where they set up their camp some miles from the station. Her diary for that date records: “Dr J went out at eleven. Shot giraffe & got lost in the dark. Had to send coolies with torches to look for him. N went out at 4 pm & shot lion first shot. Lion was after oryx.”

However, they must have decided that the time had come to end their safari for, after staying near Makindu

for six days, instead of going up the line to Athi River, they turned for the coast and made the two-day journey via Voi back to Mombasa where they arrived on the evening of 10 April. The journey from Voi was not entirely without incident. Dorothy records that “up an incline Engine couldn’t pull train, all our coolies had to get out & push it up, then a coupling broke.”

Overall, it seems to have been a thoroughly successful adventure, certainly in terms of trophies. Henry records: “List of chief animals that his Lordship shot: one Lion, two Rhinoceros, three Zebras, two Ostriches, two Waterbuck, one Coke’s hartebeest, one Jackson’s hartebeest, three Wildebeest, two Grant’s gazelle, three Thomson’s gazelle, one Dik Dik, one Fox besides several deer and small animals. Dr Jennings shot about the same amount.”

This might have been a bit harsh on the good doctor. Looking at the trophy list

recorded by Dorothy, he seems to have exceeded his Lordship both in the numbers and varieties of animals shot. Henry notes: “all the antlers, skins etc are going to be cured and send home by Boustead & Co of Mombasa,” a company presumably associated with Dorothy’s “rather pretty” and “very jolly” friend with whom she caught up again on their return to Mombasa. It seems likely that this Mrs Boustead was Ethel Marie, the wife of one of the founders of Boustead & Co, RN ‘Rex’ Boustead. If it was her, sadly, she died of consumption (tuberculosis) in Mombasa in 1905.

Looking back on this journey more than a century ago, one of the reflections has to be how very strange and challenging it must have been for Dorothy and her brother. As far as we know, they had no experience of camping at all, let alone doing so in the depths of the African bush. Although they would not

personally have had to pitch the heavy canvas, waterproof tents (servants did this for them) there would have been a strangeness to their nights under the stars in the middle of the bundu (wild African landscape). They would have had to endure difficult conditions of sleeping on camp beds placing them close to the ground, where insects like scorpions and centipedes as well as wild animals, could disrupt a night’s sleep. Water for drinking was scarce, water for washing even more so. Dorothy observed when she was back on-board Fedora that she felt “very fit after warm bath and hair wash.” Although food would have been prepared for them, they would have had quite simple meals cooked over an open fire. That fire would doubtless have burned through the night to keep the wild animals at bay, and there probably would have been a watchman on duty as well.

Dorothy’s daughter Alice told one of the authors that her mother would have always had a guide when she went out on her own and if shooting would have had a gun bearer as the guns were too heavy for her to carry. However, she would have done almost everything else herself. Alice said that she would have been dressed in “a long linen skirt…in those days it would have been around about her ankles…And a blouse of some description. Probably not up to the neck. More or less her ordinary clothes for a hot summer’s day.” Being Africa, not Britain, though, the temperatures would have been much hotter, possibly up to 30° C. Dorothy records

that when they were in Simba that it was “very hot.”

The camping life would have been in stark contrast to the relative luxury on board Fedora and the lavish lifestyle of visits on shore. In addition to the discomfort, they must have been fearful, given all the stories of railway workers being carted off by the maneating lions from the ‘safety’ of their tents. This would have only been heightened when they met Mr Whitehouse, who himself had been attacked one night when visiting Patterson in Tsavo (undoubtedly, he would have shown them the scars on his back) and had seen his sergeant dragged to his death by the marauding lion.

father visited the Mombasa Club (founded in 1897 by the Boustead brothers) on several occasions and Henry noted that they had “got a very nice club house opened last January.” Shortly after this, Henry reported that HMS Sparrow had sailed out to search for slave dhows reported in the area. She returned about a week later and would then seem to have sailed to Zanzibar at about the same time as Fedora.

While the ‘company’ was shooting wild animals, sketching landscapes and generally enjoying the completely new experience of life in the African bush, Captain Barnard, his son Henry and the rest of the crew were enjoying a more relaxing but less inspiring existence in port. Henry records that the crew was occupied with cleaning, painting and varnishing the yacht and its ancillary boats. On at least three occasions he accompanied other members of the crew when they sailed round the island in the yacht’s cutter, returning after several hours of what he described as “a nice sail.” Three British warships, Fox, Sparrow and Tartar, arrived in the harbour and the Captain and Henry went ashore to watch a cricket match between the Men of War Team and a local Mombasa side, played at the club. The locals had a big victory! Henry and his

One problem they encountered in Mombasa, which does not seem to have been an issue before, was the acquisition of fresh water. They had loaded several tons of water in Singapore, Penang, Galle and Zanzibar. Henry stated that the mate had “gone on shore [at Mombasa] to see about fresh water as it is a hard job to get it here, as it is nearly all bad. Expect we shall go round to Kilindini as the Railway works are there and they condense the salt water for all purposes.” When the company arrived at Kilindini on 10 April, Dorothy notes that Fedora was taking on water there (condensed). She also noted that Chinta’s kittens, born during their first visit to Zanzibar, had “grown very ugly.” One suspects she was not a cat person!

Fedora did not spend long in Mombasa after the return of the hunters. Once some (condensed!) water had been loaded and arrangements made for the trophies, the yacht set sail from Kilindini on the afternoon of 12 April and arrived once more in Zanzibar the next day, despite fairly slow progress as a result of the wind and a very strong current being against her.

by Jim Dawson

1907My grandfather, W J Dawson, an early Kenya settler, arrived in Mombasa in 1907.

Curious about my family history and how we ended up where we are today, I started with my grandfather, using his books and papers and a library that originated with him. This is not a formal biography; my intention is to dip into the collection to discover the Kenya that shaped my grandfather’s life, and the generations that followed.

Growing up, first in Kenya, and later South Africa, I was a voracious reader. The credit for this goes to my Irish mother. On an isolated Kinangop farm, she home-schooled us until we were ready for boarding school in Kericho. There were no children’s libraries, so when not up to mischief out on the farm, we absorbed ourselves in Ladybird books and titles by Enid Blyton and others. When that source was exhausted, we turned to my parents’ bookshelves, where I found titles like The Man-eaters of Tsavo and Elspeth Huxley’s books. Later, at my grandparents’ Njoro home, I encountered many other books about East Africa, like Joy Adamson’s Born Free and its sequels. Most of these books went with us

when we moved to South Africa. Over time the entire library became mine and I’ve added other titles. I’d never really seen the books as a collection until unpacking and shelving them all together after a recent move. I catalogued them, and there are over 100 titles, ranging from the massive East Africa (1906 - Foreign and Colonial Compiling and Publishing Co), which deserves an article to itself, to the tiny, short History of Kenya (1941), and from WFW Owen’s Narrative (1833) to Juliet Barnes’ Ghosts of Happy Valley, written almost two centuries later.

The range of books is broad, from the 19th Century explorers, through the Protectorate, then the Colony and post-colonial times. There is history, geography, biography, autobiography, and a fair representation from the romantic/ decadent school of Kenya writing, covering the period and personalities surrounding the death of Lord Erroll. The oldest volume in the collection is seminal in African history, Emile Banning’s Africa and the Brussels Geographical Conference. To these I added a collection of personal papers from my grandfather W J, as he became generally known.

WJ was a younger son in a Scottish farming

A line drawing of Mombasa and the Old Harbour from 1872. Fort Jesus appears prominently overlooking the water. (Photo taken from East Africa, 1906 - Foreign and Colonial Compiling and Publishing Co).

family, and at the age of 17 he was sent out to join an older brother on a sheep station in Australia, via South Africa. Family legend has it that when the ship docked in Mombasa, he stepped ashore and decided almost immediately that he wouldn’t be getting back on board. What drew a teenage Scot to abandon a passage to an assured future in Australia? What was British East Africa like? What was it in Mombasa that made him believe that this new entity, not yet even a colony, was his future? Among his papers is a copy of The East African Trade Journal for May 1907, which I think he must have acquired on landing, and kept for sentimental reasons, as it showed the shipping arrivals in Mombasa, for the month of April. The most likely ship he arrived on was the SS Glenelg, Glasgow-registered and operating from Glasgow to Cape Town, which arrived on 14 April 1907, according to the shipping list.

A partial clue to Mombasa’s attraction can be found in a description of an arrival in Mombasa, three years earlier, in W Robert Foran’s wonderful book, A Cuckoo in Kenya: “Everything was vividly green and sweet smelling; the air heavily laden with the aroma of the spices of the Orient; and over all rested a lethargic atmosphere of serenity…The island itself was clothed in matchless emerald-green. Here and there the curious outlines of the baobab trees vied with the feathery tops of coco-nut palms; and towering above them all were the giant, dark-green-foliaged mango trees.” It sounds irresistible. Mombasa, of course, has a long history, arguably longer than

any other Southern hemisphere city, stretching back a thousand years or more into the mists of oral tradition. Its recorded history is a study in competition between foreign powers, colonisation, and eventual freedom. Probably because of the battle between Portuguese and Arab interests, Mombasa was known as far away as England, and mentioned in Milton’s Paradise Lost, speculatively, as part of an Ethiopian empire. Mombasa was a thriving centre at a time when London was little more than a village under threat from Saxons and Vikings. Da Gama regarded it favourably, and his successors made it their East African stronghold. Later, Lieutenant Boteler in Owen’s Narratives of the Voyages to Explore the Shores of Africa, Arabia and Madagascar declared that “…there is not a more perfect harbour in the world.” Even now, the Old Town is redolent of the ages, and as Sir Charles Eliot observed, “…the entrance of the harbour should take a high rank among the views not only of Africa but of the world.”

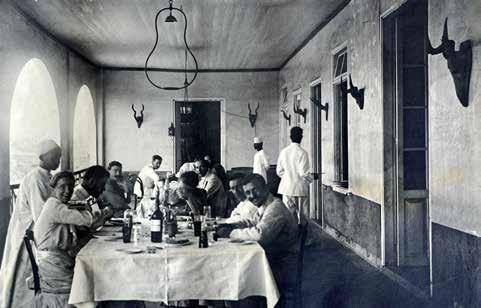

W J would have gone ashore by lighter, as no proper dock had yet been built. The young Scot would have made the trip into town on the trolley railway, a sort of man-powered tram pushed along tracks, laid at the time of the Uganda railway, “[r]attling along at a good rate” according to Meinertzhagen in his Kenya Diary. The terminus was reached by walking up a track from the rough jetty. We don’t know if W J used the Africa Hotel, the slightly better Grand Hotel, or the Cecil Hotel, but it is to be hoped that things had improved in the three

years since Foran’ s arrival. Through a booking error, Foran found himself at the Africa, the least salubrious of the three. It was described in East Africa as “…containing 12 bedrooms, dining room, a large verandah overlooking the harbour and open sea, and a bar and sitting room, and only the best brands of liquor are kept…[T]he hotel should satisfy the demands of the most exacting visitor to Mombasa.” In a perfect illustration of the gap between advertising and reality, Foran described it a little differently: “…a positive nightmare. If the dinner was execrable, the beds were infinitely worse, and the offensive odours breathed simply unprintable…I did not know there were so many and different abominable smells in the world…” His description of a nightlong battle with fleas, bedbugs, mosquitoes and moths is worthy of Jerome K Jerome, an English writer and humourist, best known for a comic travelogue, Three Men in a Boat. The Grand, too, had its problems - “a dinner of tinned salmon and corned beef…as the rain dripped steadily through the ceiling…mostly it went onto my plate…” Despite its long history, Mombasa in the early 1900s was still very much in its infancy in terms of traveller comfort.

The real centre of socialization and business networking was the Mombasa Club. It has always seemed to me that as soon as the second Brit arrived in a new territory, the first would say, once introductions were made: “I say,

Carruthers, I think we should start a club!” By 1907 the Mombasa Club was already entering its second decade with over 500 members. W J might have stayed there; no doubt he would have taken advantage of its hospitality. Here he would have heard about the interior - the good with the bad. The Uganda Railway was out of its infancy, but tales of Paterson’s man-eaters would still have been part of the currency of conversation, and the interior was far from settled. Old-timers would have relished regaling a raw young Scot with tales of death by tooth, tusk, horn and venom.

No doubt he would have been directed to the various outfitters for appropriate tropical kit, and there were plenty of suppliers. Mombasa was a thriving town of 30,000, with many outfitters, importers, exporters, agents and, even then, a tourist operation offering hunting trips to the interior. Here were warehouses filled with ivory and skins for export, and even some basic industry, in the form of cotton ginning and tanning. Mombasa was the primary town of what was to become the colony, but not for long. The year of W J’s arrival in 1907 coincided with Nairobi, fed with people and goods by the new railway, becoming the capital. The East African Standard was still published in Mombasa, so he would have turned there for information. He would have learned that items like spine pads and pith helmets were standard kit for white settlers, and

The Right Honourable Joseph Chamberlain riding in the tram in Mombasa on his visit to Kenya in December 1902. At the time he was the Secretary for the Colonies. He was on his way to South Africa and stopped in Kenya to assess the country and its newly completed railway. He also met with Charles Eliot, the Commissioner for British East Africa, to discuss settlement policies.

(Photo taken from East Africa, 1906 - Foreign and Colonial Compiling and Publishing Co).