51 minute read

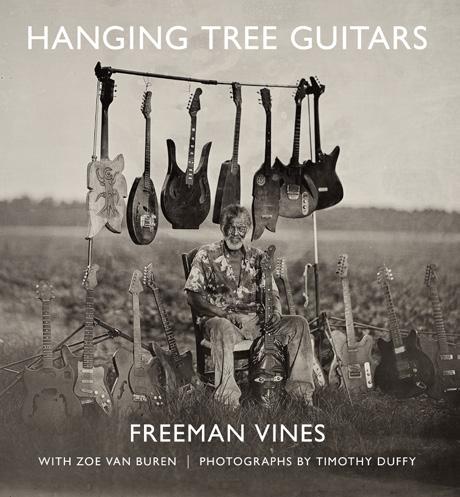

COOKING WITH

HOME __ PLATE

Written by Jennifer Kornegay / Photography by Lena Seaborn

Advertisement

Spode Maritime Rose, a great deal found at an estate sale, adorns May’s dining room table used with antique American pattern glass goblets and an antique celery vase. The candelabra was a birthday gift from her husband.

MOST MORNINGS, I DRINK MY COFFEE FROM A PLAIN WHITE MUG, BUT EVERY NOW AND THEN, I CHANGE THINGS UP. I REACH UP TO A TOP SHELF IN A GLASSFRONT CABINET AND GRAB A SPECIAL TEA CUP AND ITS MATCHING SAUCER.

It is shallow and wide; its slim handle is delicate, a ceramic representation of a plant’s twisting vine rendered in olive green. The vine continues in a band around the cup’s exterior, sprouting leaves in a fresher green that, on one side of the cup, flank a Pepto-pink flower bud and on the other, surround a fully open blossom in the same pleasant pink shade. I only have four of these Desert Rose cups. Not because I have broken the rest (although I am a klutz of great renown), but because I — in a rather uncharacteristic show of selflessness — agreed to share these simple but meaningful heirlooms. There were eight in the set my grandmother, my mama’s mama, had; the other four went to my cousin. I don’t often use them — their lack of depth leads to splashes and splatters when my Keurig is spitting out its stream of piping-hot coffee. But when I do, memories of my grandmother flow clear and vivid. I can’t even catch a glimpse of my small Desert Rose collection without thinking of her. It’s the same for many who hold onto silver or china, be it quite ordinary or ornate, common ceramic or precious porcelain. The value is usually tied not to actual monetary worth but something less quantifiable. These items are a tangible way to connect to another time, another place, another person, be it a loved one or the unknown craftsperson who fashioned a thing of beauty that’s also functional. For the close to 48,000 people in the Facebook group Beautiful Table Settings, collecting and displaying china, silver, glassware and other eating and drinking accoutrements, as well as general table décor, is a bridge that connects them with others who share their fascination. This virtual gathering place brings together women and men of all ages, races and backgrounds from around the United States. They post photos of their tables, long and short, round and rectangular, all outfitted with the works: tablecloths, embroidered napkins, serving platters, full place settings of china and silver, crystal wine and water glasses, tea cups and saucers, place cards, candelabras and elaborate centerpieces. Not all the settings are fancy. Sometimes they’re casual, comprised of rustic pottery and printed paper napkins. Sometimes they’re whimsical. Sometimes they’re focused on a holiday or anchored by a single color, assembled with items in varying shades of the same hue. Often they’re mixes of fine and everyday pieces, allowing each table setter to show off their own styling tastes and skills. Once each new photo is up, the group gets really busy. They comment and compliment, discuss, express envy, ask and answer questions and offer tips and advice on all kinds of things, like how to use rarer items. (One member recently revealed that a lead crystal cracker tray makes a perfect holder for a hot curling iron.) There’s a little bragging, a lot of praising and plenty feedback fishing, a la, “Which plates do y’all like better with my new linen napkins? The dainty pink floral or plain white with a platinum ring?” queries. Sometimes they share detailed behind-the-settings stories, outlining the provenance of every item or telling the tale of their great aunt’s cut-glass gravy boat. But mostly, they have fun, as May Ridolphi Eason, who founded the group 17 months ago, explains.

Camaraderie & Community

“It’s a really active group, and it’s just enjoyable, so enjoyable, to have this sense of community with so many people who like what I like,” she says. “And we learn so much from each other too. There is so much to discover about all of the different patterns and pieces and time periods and materials.” She’s chatting while giving an informal tour of her quite formal home in Wetumpka, Alabama, where every available flat space holds something beautiful (and breakable). It’s like a museum, yet obviously lived in too. Tables and sidebars are topped with glittering punch bowls, cake stands, goblets, vases and more, all Early American Pattern Glass. (These Victorian-era pressed glass pieces are what first drew May into table settings.) China cabinets are filled to max capacity with plates and tea cups, some rimmed in gold, some festooned with rainbow-hued flowers and showy birds, others embellished with classic scenes rendered in timeless blue and white. She deems her china and glassware works of art as she speaks about makers and patterns with such deep knowledge, it to brings to mind a museum again, with May the careful curator, a walking, talking encyclopedia. “Having these things and setting these tables is just a way to bring more beauty to my life,” she says. Her collection is one of a kind, but she’s not alone. In just a few years, Beautiful Table Settings has pulled up a seat at its big virtual table for more than 40,000 like-minded people, including Jim Gatling, a BTS member in Arkansas and a

Top left: Breakfast in bed made special mixing patterns with a dinner in Lowestoft Bouquet by Royal Doulton, salad in Floradora by Royal Doulton, bowl, coffee and egg cups are Cuckoo by Minton. Top right: The author’s treasured Desert Rose cup and saucer sit in front of a photo of her grandparents. Bottom: Jim Gatling’s parent’s wedding china, Lowestoft Bouquet by Royal Doulton, bought in 1947. Monogrammed sterling silver gravy ladle was his grandmother’s. The pattern is Stradivari by Wallace.

self-described “non-joiner.” “I don’t usually get into groups and things, but someone told me I might like this, and so I checked it out,” he says. The recently retired art teacher was already using table settings to fill a void in his life. “I was missing the creativity after 41 years of teaching art in school, and putting the settings together lets me play with color and texture and make decisions about how they interact,” he says. Each different setting is an expression of his take on beauty, and BTS is like a gallery. He posts photos to the group almost every day. “The group lets me share my creations with a huge audience,” he says. May is also always engaged with BTS; she changes the settings on her long dining room table and smaller kitchen table daily, pulling from more than 100 china patterns (not all are full sets), her massive collection of glassware and her more modest collections of sterling and silver plate. For her, it’s pure entertainment. “I mix and match patterns and items; it’s just what strikes me as lovely, and it’s really like playing,” she says. “When I’m done, I love looking at them.” Joan McLendon Budd, who lives in Seale, Alabama, is another of BTS’ admins and grew up with an interest in pretty plates, saucers and more, but was on the verge of giving away her multiple silver and china sets. “I was the typical Southern gal, loving my mother’s and grandmother’s china, but I was about to get rid of it all,” she says. “My kids didn’t seem to want it, and so I thought it was time to just let go.” The fulltime lawyer and spare-time thrifter and vintage-store shopper shudders to think how close she came to emptying her silver chest and china cabinet. “Thank goodness this group came along,” she says. “It made me stop and think, ‘Not only am I not giving this all up. I’m getting more!’ I have had so much fun with it.” FOR MANY, THE VALUE OF CHINA OR SILVER IS May and other admins like Joan ensure TIED NOT TO ACTUAL MONETARY WORTH BUT the fun never stops by keeping BTS a A TANGIBLE WAY TO CONNECT TO ANOTHER controversy- and conflict-free zone. “We TIME, ANOTHER PLACE, OR ANOTHER PERSON. don’t allow discussion of politics, religion or current events,” May says. “BTS is a happy place.” She and BTS admins also enforce the golden rule. “Our members are expected to treat others with respect,” May says. “If you can’t say something nice about a post or in your own posts, don’t say anything at all.” All members have to ask to join and are only admitted after an administrator looks over their profile. Once in, it’s not hard to get put right back out. One snarky comment can do it, and May believes it’s this and the other guidelines that have kept the group going and growing. May also keeps the conversations going with theme days to drive and inspire posts. Each week there’s a day for selling, a day for giving pieces away, a day for ISO (in search of) posts. “That’s Wednesday Wants day,” May says. Other days have other topics, like specific colors or patterns that begin with a certain letter. It works. On any given day, BTS averages between 100 to more than 200 posts, with countless comments on each. Sometimes it’s a photo with a simple “what do you think” question to get others’ thoughts and perspectives in the comments. Jim writes mini-memoirs with many of his posts. A good part of his table setting collection is comprised of pieces inherited from his grandmother and his mother, and he often tells stories about these heirlooms and how they were used when he was growing up. “I have my grandmother’s sterling water goblets, and I remember my mother buying them for her one at a time for holiday presents through the years, until she got all 12,” he says. These posts and others like them tighten the bonds group members have formed, ties that have, in many cases, led to deep friendships. “I’ve gotten to know several people very well and made good friends,” Jim says. “There’s one I now talk to every morning.” May echoed Jim. “I’ve actually met a few people right here in Wetumpka that I didn’t know before BTS and gained them as friends,” she says. And as much as May knows, she’s aware there’s always more to discover. “The research into the history of these things is one part that first hooked me,” she says, “so, I love diving in and finding new facts, and in the group, we share information and tips. For me, that aspect is another major benefit of BTS.”

To Use or Not to Use

While education and entertainment motivate May, the museum description becomes even more apt when she admits her pieces don’t see routine use. “I don’t’ cook, and I don’t daily use the pieces from my table setting collections,” she says. Jim is just the opposite. “I’m like, ‘Why not use it every week?’” he says. “I have so many fond memories associated with many of these things — the china, sterling and crystal that were in my family — so I want to share those memories and let others make their own memories around these pieces.” Joan feels the same. “It’s so incredible to have the pieces that are tied to my family. I think that is such a lasting Southern tradition, where we pass down china and silver through multiple generations,” she says. “And we connect with our ancestors in that way. I mean, my daddy was born in 1895, and I have his mother’s china. He sat and ate off those plates, so it is more than just a dish to me. Someone loved it and took care of it and entrusted it to me, so that is special. I have my mother’s Blue Ridge Pottery, and it was a set she bought for her own mother. I can get real emotional any time I set the table with that.” In addition to china, Jim also inherited more than a thousand of his mother’s recipes. “I now cook for my son, daughter-in-law and two grandkids at least once a week, and before COVID, I’d have 10 to15 people a week for a dinner.” These occasions always include a fresh table setting, which are anticipated as much as the menu. “I like to do something different every time, and I love to mix my patterns,” he says. “I like a traditional table, but I put some flair with too.”

On the Hunt

An unspoken BTS motto seems to be, “If you’ve got it, flaunt it.” But you do have to have it first. While a good many BTS members have inherited pieces, they’re routinely adding to their collections. And sometimes, the search is as thrilling as the eventual acquisition, display and use. “I completely shop at flea markets, antique stores and consignment stores,” says Jim. “I don’t do a lot online because I like the hunt; I like to look in person. That’s as special and fun as actually finding and buying it.” Shopping around often results in big bargains, which is even more exciting for collectors like Jim. “I won’t pay a lot for the things I buy, so I’m always looking for the good stuff at low prices,” he says. “It’s such a jolt when that happens.” Joan is simpatico with Jim when it comes to deals. “My passions are thrifting and shopping antique malls looking for discounted vintage,” she says. “And it’s so fun to find that really neat piece that I can pair with some of my finer inherited things.” She recently procured some pieces decorated with goats. “A lot of times, the things I buy correspond to a memory,” she says. “I had a pet goat named Baby Doll when I was in preschool, so there’s the root of the goat dishes!” Members also source from North Carolina company, Replacements, Ltd. As the world’s largest seller of china, crystal and silverware, including multiple discontinued and hard-to-find patterns, it’s a go-to for filling in and fleshing out sets.

A Dying Art

When Joan joined in November 2019, the group was just about to hit 2,000 members. With 43.9 thousand and counting as of late December 2020, BTS is expanding at an explosive rate. Yet, its pool of potential members may actually be shrinking. Over the last five years, multiple news outlets have reported that fewer and fewer young people are interested in owning fine china, sliver and crystal, much less collecting multiple patterns. Many brides don’t even consider registering for it, and folks inheriting these items from grandparents or parents are boxing it up and giving it to Goodwill. Perhaps some see china and the like as pompous, outdated emblems of another era. Others may think it’s nice but believe it’s all too expensive and would rather put their money elsewhere. But, as May explained, for her and most BTS members, the hobby is not haughty. “I have some fine things, but I often mix a $1 thrift-store find — and there are amazing deals out there — with a $100 piece,” she says. Joan agreed. “It has nothing to do with status, because you can find a lot of it at good prices now,” she says. Like May, Joan deems her pieces “art” and just like any art, she knows that admiration is subjective. “To me, china is usable art, and beauty is in the eye of the beholder, but I also have an appreciation of the process, the making, the craftsmanship of it all,” she says. To reverse fine china’s downward trend, Joan is taking a proactive approach, at least at home. “I’m now using all of my things again,” she says. “I recently did a big dinner for my son and pulled it all out and set the table. I told him, ‘Look at all this. This is a legacy; this was your grandmother’s, your great grandmothers. When I’m gone, if you don’t take this, use it and love it, I will haunt you for the rest of your life.” Spooky warnings aside, Joan has noticed a shift in BTS’ makeup that gives her hope. “Initially, the group was mostly, we’ll call them, ‘mature people.’ But now the way the page has grown, there are clearly younger people getting interested in this and starting to appreciate this. I see a renaissance of appreciation,” she says. “And I think that was part of May’s vision when she started this, to bring joy back to setting a table and show people there can be beauty in whatever you do.” May always points people to the personal side of collecting as well. “It’s really all about what you like to look at, what makes you smile,” she says. “I encourage people to discover what you like and then focus on that; don’t be swayed by what someone else tells you is beautiful or valuable. Your collection should be a reflection of you.” But the principal purpose of BTS is actually much broader than sharing photos of table settings and is similar to most other Facebook groups, as well as book, garden and all manner of clubs and societies. “It’s a lot about making friends,” May says, and Jim agrees. “That’s the thing I want most to say about this, how nice, giving and thoughtful all the BTS people are,” he says. “The people are truly the best thing about it.”

Top right: For her son’s birthday dinner, Joan set the table with simple gold banded plates that belonged to her paternal grandmother. Marked Victoria Austria, the set was a wedding gift from her grandmother’s parents in the late 19th century. The sterling is Joan of Arc, by International Silver, a gift from Joan’s paternal Aunt Rosa when she was 3. The pink glasses are from her paternal grandmother’s lemonade set. Top right: May’s loves to mix patterns. Here she starts with her wedding china dinner, Carlyle by Royal Doulton and salads she found at various places. The top plate is part of a dessert set. Bottom left: Assorted sterling and silver-plated serving utensils, salt and pepper, and trays from Jim Gatling’s collection. In the bottom box is a place setting of Chantilly by Gorham. Introduced in 1895 by the Gorham Manufacturing Company, it is their flagship silver pattern. Bottom right: The goat china is a recent purchase by Joan. “I had a pet goat named Baby Doll when I was in preschool, so there’s the root of the goat dishes!”

Heroes Found

“HISTORY FORGOT

THE LIFE-SAVING SERVICE THAT BIRTHED THE U.S. COAST GUARD. JAMES CHARLET IS CHANGING THAT.“

James Charlet and his wife, Linda Molloy, stand in the center of the Sanderling Resort Lifesaving Station Restaurant on the Outer Banks of North Carolina, addressing a crowd of 40 diners. The two are dressed as characters from the late-19th century. Charlet sports a big salt-and-pepper beard and the gold-buttoned, navy-blue dress uniform of a U.S. Life-Saving Service station keeper. Molloy plays his wife, wearing gloves, a long black skirt, white collared blouse and matching sunhat—all tastefully adorned with Victorian frills. “Go to any town or city in America and ask people if they’ve heard of the U.S. Life-Saving Service, and maybe one in a hundred will say yes,” says Charlet, 74. Yet the government agency, which was founded in 1871 and morphed into the Coast Guard in 1915, rescued more than 177,000 sailors and civilians from coastal shipwrecks. Servicemen did it using little more than cork flotation devices, ropes and oar-driven wooden boats. Crews of about eight men were assigned to lifesaving stations, which were mostly located on isolated coastal shores and managed by a ‘keeper.’ Known as the “Graveyard of the Atlantic,” the Outer Banks was notoriously dangerous for mariners. Accordingly, the area was home to seven stations in 1874 and 29 by 1915. During that time its USLSS crewmen saw more action than any other U.S. location. “These men were constantly regaled as heroes in the nation’s top magazines and newspapers,” Charlet tells the audience. “People all across the country were inspired by their daring acts of bravery. But today, that history is almost totally forgotten.” Charlet has spent much of the past 20 years trying to change that. The Sanderling event celebrated the quest’s crowning achievement: Globe Pequot’s March 2020 publication of his new book, Shipwrecks of the Outer Banks, Dramatic Rescues and Fantastic Wrecks in the Graveyard of the Atlantic. Charlet and Molloy, who work together at the Chicamacomico Life-Saving Station Historic Site on Hatteras Island, told theatrical stories about wrecks and USLSS rescues. Executive Chef Brian Riddle provided a four-course dinner of fine-dining takes on seasonal, period-correct dishes and beverages enjoyed by crews. Originally built in 1874, and later designated a National Historic Landmark, the resort’s renovated station-turned-restaurant was the perfect venue.

Left: Standing in the center of the Sanderling Resort Lifesaving Station Restaurant on the Outer Banks of North Carolina, Charlet sports a big salt-and-pepper beard and the gold-buttoned, navy-blue dress uniform of a U.S. Life- Saving Service sta and later designated a National Historic Landmark, the resort’s station-turned-restaurant hosted the venue. Top Right: The Keeper’s Table meal featured Braised Duck and Root Vegetables, Mushroom-Walnut “Ketchup” and Sorghum Mush.

“[Charlet and Molloy] transported the audience back in time and held them spellbound with tales of real-life heroes,” said Sanderling Resort program coordinator, Ashley Vaught, who attended the dinner. It was so successful she’s partnering with the couple to do more in 2021. “Their ability to make history come alive and shed light on the lives and deeds of these astonishing men is informative and wonderfully entertaining.” Charlet’s book has struck a similar nerve with readers. It’s become one of Globe Pequot’s current best-sellers and has been made available at major retailers throughout the U.S. and in more than a dozen countries worldwide.

How did a guy that was born and raised in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, become one of the world’s top experts on a vanished government agency and related Outer Banks shipwrecks? “I guess it started as a kid living by the Mississippi River,” says Charlet. As a boy he was fascinated by large boats, particularly restored 19th century steamboats. Trips to New Orleans stirred his imagination with sights of old warships, schooners and sailboats. Charlet also enjoyed stories and was drawn to tales about historic figures. However, children’s history books mostly offered trivia. Where were the personal details? He reimagined characters with pen and paper to fill in gaps. Early writings ranged from retellings of the Crucifixion to the secret lives of river pirates. Charlet’s family moved to New Jersey when he was 14. “That was a pretty huge culture shock,” he says. He focused on making it through high school and into college. Matriculating to Duke University introduced him to North Carolina and the life of the mind. “I fell in love with the humanities and wanted to learn about everything,” says Charlet with a laugh. He majored in political science because the program brought flexibility to study religion, history, literature, poetry, philosophy, sociology and more. After graduation, a family member helped Charlet get a job teaching eighth-grade American history in Baton Rouge. The work revived his interest in storytelling—and frustration with status quo approaches to the subject. Focusing on timelines, numbers and reductive causes and causalities put kids to sleep. But reworking historical events and social movements into dramatic narratives centered around high-stakes human experiences? “That got their attention,” says Charlet. “And it was more fun than lecturing and scribbling dates across a chalkboard.” Charlet started missing the North Carolina mountains after a few years and found a teaching post near Raleigh. By then he’d married his first wife and had a young son. The family moved in 1976 and stayed for 17 happy years. Though they took coastal vacations, Charlet didn’t step foot on the Outer Banks until 1992.

rts a big salt-and-pepper beard and the gold-buttoned, navy-blue dress uniform of a U.S. Life- Saving Service station keeper addressing a crowd of 40 diners. Center Left: Executive Chef Brian Riddle provided a four-course dinner of fine-dining takes on seasonal, period-correct dishes. Center Right: Built in 1874, The Keeper’s Table meal featured Braised Duck and Root Vegetables, Mushroom-Walnut “Ketchup” and Sorghum Mush. Bottom Right: To complete the meal was a Spiced Fig Pudding with Hand Whipped Rum Cream and Powdered Milk-Peanut Candies.

“On a whim, I applied for an administrative position in Ocracoke,” says Charlet. His son was entering college; cancer had just taken his wife. He desperately needed a change. The give-or-take 600-person island village is the southernmost inhabited area on the OBX and accessible only by boat. An interview gave Charlet an excuse to visit. Getting there meant following Highway 12 through most of the mile-wide, 175-mile-long chain of barrier islands. Traveling into rural southern communities like Rodanthe, Avon and Hatteras, Charlet was amazed by what he saw. “It was sparsely populated, peaceful, and incredibly beautiful,” says Charlet. While the job didn’t pan out, the landscape called to him. In 1993, he sold his house and secured lodging and seasonal work in Hatteras. “Looking back, it sounds so reckless,” says Charlet. But it didn’t feel that way at the time. “It felt like the first step in moving forward with my life.” The next two years were mostly spent grieving and working odd jobs to survive. Still, Charlet’s scholarly curiosity was helping him find community. An interest in the Wright Brothers, for instance, led him to join the First Flight Society and Friends of the Outer Banks History Center. He quickly won a reputation. North Carolina State Historical Sites Chief Curator, Martha Jackson, says Charlet does nothing halfway. “His passion for history is superlative and inspiring.” And it’s augmented by an endearing sense of humor, kindness and charm. Charlet was soon offered a job at Roanoke Island Festival Park developing living-history programming for its replica 16th century English settlement. He accepted—and dove into the area’s maritime history. He learned more about the passage from Europe to the Americas, including the dangers of the coastal Carolina seas. Research revealed more than 3,000 known shipwrecks have occurred along the OBX, with an estimated 600 occurring near Hatteras alone. Surrounding stories offered a wellspring of intrigue. For instance, barrier islands like Hatteras were located about 30 miles from the mainland and had no paved roads until the mid-20th century. Villages were isolated, clannish, and had about 100-200 residents each. Groups known as ‘wreckers’ once used lanterns to trick wayward ships into running ashore at night. The boats were pilfered for supplies, building materials and valuables. Later, German submarines and mines sank more than 100 freighters and tankers during World War I. “You start reading about this stuff and there are so many incredible stories, it gets addictive,” says Charlet. He volunteered at local mariners’ museums to learn more. One was the Chicamacomico Life-Saving Historic Site, which features a restored 19th century USLSS station. “You hear ‘life-saving’ and you think lifeguards, lighthouses, that sort of thing. Well,

this was something altogether different.” The five-building station was established near the remote village of Rodanthe in 1874. It contained the area’s only oceanside structures and was manned by a ‘keeper’ and eight men. They underwent rigorous training and daily exercises. The complex had a large, two-story cedar shake ‘keep’ with a watchtower, from which crewmen kept a 24-hour vigil. When danger struck, they sounded an alarm and took to the water in a large dinghy. The station’s most famous rescue involved the August 1918 wreck of the British tanker, Mirlo. Charlet used old captain’s logs, news articles, reports, correspondence and interviews to reconstruct what happened. The vessel was transporting 6,679 tons of petroleum products from New Orleans to Norfolk, Virginia, when it struck a German mine in a narrow shipping channel 7 miles off the coast. Surfman Leroy Midgett saw a huge plume of water erupt into the late afternoon sky before the deafening roar shook the station. He leapt into action, alerting the keeper and mobilizing the crew. They dragged their newly motorized wooden surfboat over the dunes and onto the beach using a wheeled cart. There’d been a storm the night before and the waves were so rough it took 30 minutes to launch. They were racing toward the wreck when a second explosion tore the ship in half. Thirty-two of the 51-man crew piled into two bowside lifeboats. The rest were trapped on the stern. As the first boat rowed for shore, fouled rigging overturned the second. Crewmen were clinging to its hull when the Mirlo’s fuel tanks detonated, turning the ocean into a fiery inferno. All but six were killed in the blast. The USLSS crew watched in horror as the wreck disappeared behind a wall of black smoke. Still, they continued. Reaching the first lifeboat, they learned the second was trapped within the flames. Keeper John Midgett circumnavigated the blaze, discovered a break and steered inside. The heat singed the crews’ facial hair, blistered the boat’s paint. They spotted the overturned boat amid the smoke and sped toward it. They swept away burning water with oars as sailors emerged from under the hull. Dragging them onboard, the crew fled for their lives. Bursting through the flames, Midgett learned of the additional 19 missing crewmen. Consulting survivors, he thought they may have escaped using a small lifeboat near the captain’s quarters. But their combined weight would have almost certainly rendered them close to capsizing and unable to row. Midgett steered into the current. He found the boat floating 9 miles south and towed it back. By 9 p.m., he and his crew had delivered 42 of the 52 British sailors safely onto the beach. Remarkably, the heroic tale wasn’t anomalous. “Once I’d pieced together the Mirlo story, I thought, ‘Wow, I bet there are more of these,’” says Charlet. Researching neighboring stations validated the hunch. On one side, a serviceman had singlehandedly saved 12 men from a wrecked barkentine. The only all African American crew in the USLSS had served on the other—and executed dozens of rescues. “It didn’t take long to realize these stories were virtually inexhaustible,” says Charlet. Charlet was hooked. He started spending free-time tracking down information about obscure OBX wrecks and related USLSS rescues. He compiled findings into narratives and shared them with groups like the National Maritime Historical Society. They were well received and led to public presentations and articles in regional periodicals. “People really responded to these stories, and I was one of them,” says Linda Molloy. She met Charlet at a Chicamacomico Historic Site event in the early 2000s. His presentation about the USLSS inspired her to volunteer and the two began dating soon thereafter. A few years later, they were hired by the onsite museum. Brainstorming ideas to boost attendance and enhance visitor experiences inspired them to develop historical personas. Molloy was a seamstress and former actor. She made costumes and worked with Charlet to hone living-history presentations centered around turn-ofthe-century rescues and village life. Jackson, the North Carolina historical sites curator, calls the results “fantastic.” Visitor feedback was unanimous: Molloy and Charlet were an extraordinary hit.

Charlet’s book came out of a chance encounter: An author with ties to Globe Pequot read one of his stories and suggested he pitch writing about the USLSS. “The Coast Guard is the only branch of the U.S. military where the primary focus is saving lives,” says Charlet. Exploring its largely forgotten origins had national appeal. The adventurous and almost unbelievable reality of Outer Banks USLSS servicemen was like a positive version of the Wild West. “Their deeds were heroic, in the truest sense of the word.” Charlet emailed the publisher, submitting past articles as potential chapters. They loved the material and signed a deal in 2018. “It was all pretty surreal,” says Charlet, laughing. The project let him fully indulge his obsession. “I got to spend about eighteen months totally immersed. It was great fun.” And the book reads accordingly. On one hand, it’s filled with dozens of suspenseful tales about rescues. On the other, it offers a fascinating portrait of 19th and early-20th century life on what is today one of the East Coast’s top tourist areas. For his part, Charlet is thrilled the book has found a large audience. But his delight isn’t about personal acclaim. “I’m happy to help restore this amazing chapter of history,” says Charlet. In an era that celebrates actors, athletes, YouTube stars and billionaires as heroes, “it’s important for people to understand what real heroism looked like.” To be sure, Charlet’s book showcases some dazzling examples.

keeperjames.com sanderling-resort.com chicamacomico.org

I PHOTOGRAPH ALL ASPECTS OF THE SOUTH, NOT JUST PRETTY OLD MANSIONS. FROM COUNTRY STORES TO TENANT HOUSES TO DOWNTOWN STREETSCAPES, FARMING AND OLD BARNS, ODD SIGNS AND RUSTY EQUIPMENT. I WILL STOP AND SNAP PICTURES OF THE CRAZIEST THINGS.

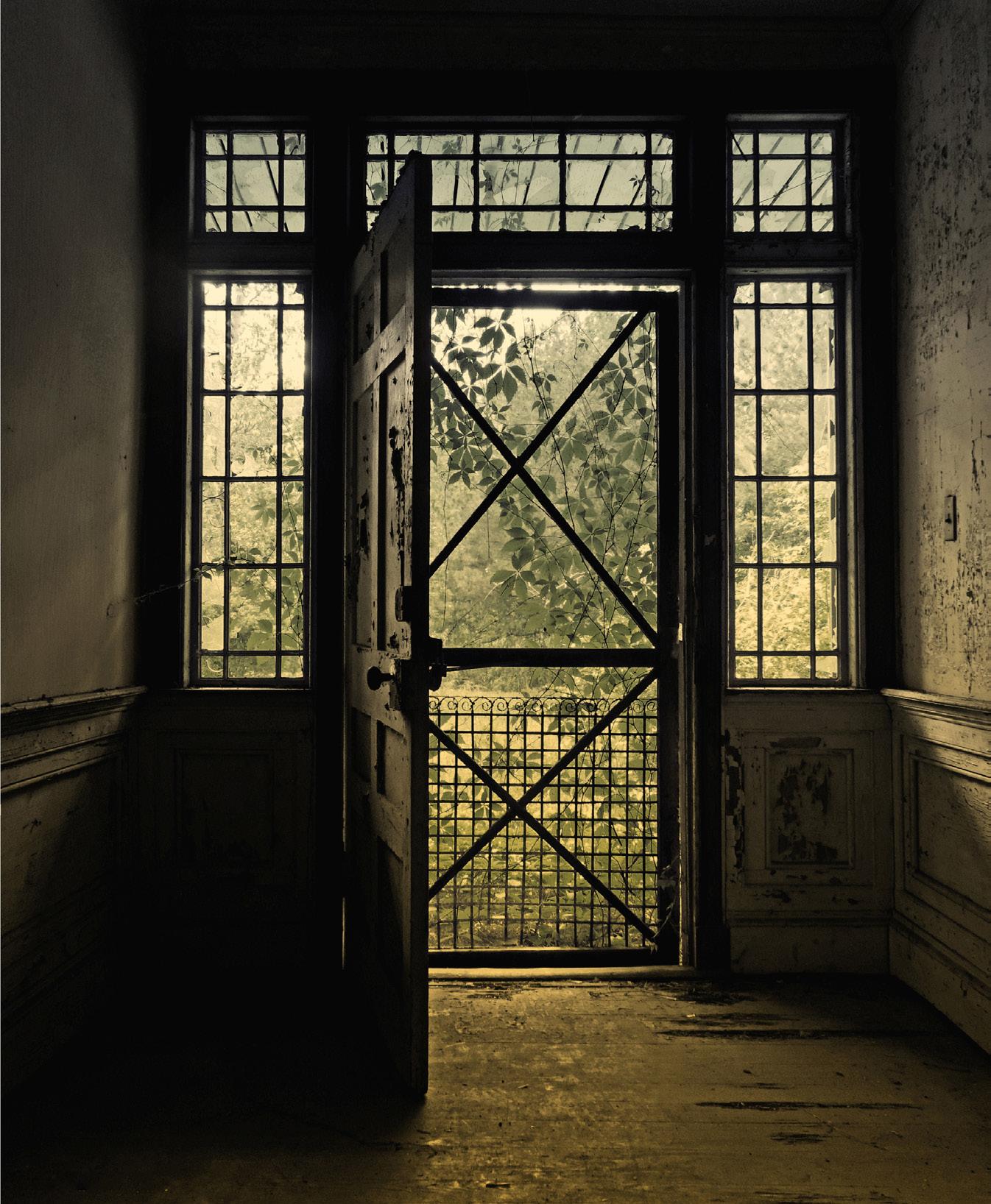

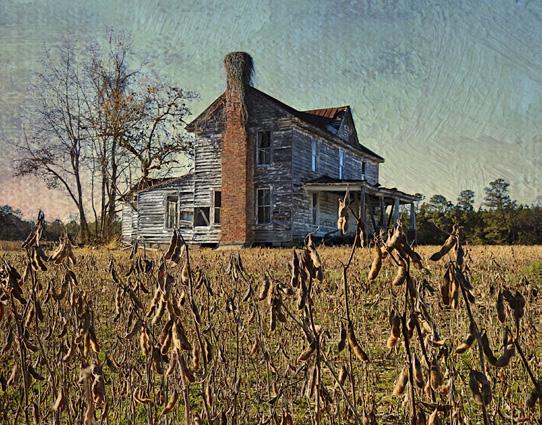

Photographing the landscape of Southern heritage has become both a passion and addiction for Watson Brown. Brown’s photographic journey began ten years ago after his retirement as a City Planner in North Carolina. “I just became bored to death. I had only basic camera skills and no formal training at all, but I taught myself, especially my unusual editing techniques.” Brown found that he was happiest when he could hit the road and discover the real people and treasures of North Carolina. The journey was also a much needed outlet from the tedious job of restoring his inherited family homeplace built in 1854. With six acres of grass to cut in the hot and humid Southern summer Brown needed some sort of significant diversion to relax before it “did him in.” Traveling the backroads of North Carolina and documenting the region in an artistic way, he found the memories of another time could launch a second career of sorts. Brown had finally found his passion in life, and found that other people loved what they saw, too. “People wanted to buy my photos, too. It became a totally win/win situation.” You can follow Brown on Instagram @planterboy or on Facebook at Watson Brown’s Backroad Photography. His images are displayed on both sites and are available for purchase. Contact him at planterboy@

embarqmail.com

Top: Abandoned House and Soybeans, Bertie County, NC Center: Eddie and the Cruisers, Pitt County, NC Bottom: Old Primitive Baptist Church, Tranter’s Creek, Beaufort County, NC Opposite: Old Farm House and Cotton Field, Near Erwin, Harnett County, NC

PEOPLE OFTEN TELL ME THAT I AM THE PHOTOGRAPHER OF SOUTHERN MEMORIES. “ “

Spreading Word

“I KNEW I COULD MAKE ALL THIS NOURISHING FOOD, BUT THAT WOULDN’T DO A THING IF I COULDN’T GET IT INTO PEOPLE’S MOUTHS, SO I HAD TO MEET MY CUSTOMERS IN THE MIDDLE. “

We’ve all heard the adage, “You are what you eat,” often brandished as a reprimand to shame us into a heathier diet. But Mee McCormick is preaching a different message: “Change your plate, change your fate.” She believes there’s no single “right” way to eat well, that quality, nutrient-rich ingredients are essential, and delicious and good-for-you can coexist. She’s not just proselytizing this, she’s practicing it at Pinewood Kitchen & Mercantile, the business she runs with her husband and rancher Lee in Nunnelly, Tennessee, about 45 minutes southwest of Nashville. Steering clear of admonishment, Mee’s “plate/fate” motto is an encouraging and affirming statement. But in any conversation about food and health, Mee also poses a question: “What are you doing with your wellness?” Her answer to this query is found at Pinewood, an edible empire that includes an organic farm and cattle ranch; a general store; two cookbooks; a restaurant that serves Southern standards full of wholesome farm freshness and free of GMOs, pesticides and additives; a line of microbiome soups; a canning facility for making the soups, plus jams, pickles and other products; and a gluten-free bakery. The foundation of this expanding food-based business is Mee’s passion to teach others why and how to harness the healing powers of food blended with her desire to provide flavorful favorites to be safely enjoyed by those with severe food allergies or restrictions, aspirations rooted in her own experiences. “I know when I was a kid, had there been a place like Pinewood Kitchen, where my mom and I could have gotten fed well, our lives would have been different,” she says. “I feel an urgent need to share what I’ve learned with others.” And her lessons aren’t focused solely on food. “Kindness is key to health too. Everything we do here is mindful and kind,” she says. Today, she is living out this mission, right in her tiny community and all over the country, delivering and shipping Pinewood products and spreading her eating and cooking philosophy with her cookbooks. But her work is not exclusively altruistic; it began as an effort to heal herself, from mindsets planted in her childhood and the illness that debilitated her as an adult. Mee grew up poor, and not just food insecure, but fearful of food. “I’m from the northern Appalachian Mountains. I grew up hungry as a child, and my mother had a digestive disease, so she was really unable to eat a lot of the time,” she says. “I grew up watching that, watching her suffer in relation to food, so there was always this weird energy around food for us.” When Mee was 25, sickness hit her too. “I started having severe digestive issues, and by age 30, I was married with kids, and I weighed 89 pounds,” she says. She married into the family that founded the Winn Dixie grocery store chain and lived with Lee and their children on part of the family’s Pinewood Farm. “I had access to all this fresh food, and I was too sick to eat anything.” Doctors found a large ulceration in her intestines that, due to its position, could not be removed. As she wrestled with this new and frightening hurdle, an internal voice put her on an alternate path. “I heard, ‘What’s in it?’ and I took that to mean, ‘What’s in your food?’ I wasn’t eating much, but food was the only thing touching my intestines. I came to believe it was the problem.” The solution? Eat differently. It sounds simple, but for Mee, it would require throwing off her old ideas about food and gaining some new knowledge. “I was so intimidated by cooking, and that goes back to hunger and poverty and my mom’s illness,” she says. She started working with a macrobiotic cooking counselor and discovered how better gut health could change her life. She also turned to friend Dr. Joan Borysenko, a leader in the wellness world who Mee had come to know through

Left: Pinewood Kitchen’s menu changes often to reflect the farm’s harvests and features multiple gluten-free, vegetarian and vegan options. Right: My Pinewood Kitchen cookbook fetures 130+ recipes.

Recovery Ranch, a treatment center her husband started at the farm to help those battling addiction and depression. “Joan is who told me, ‘You need to change your food,’” Mee says. “And she gave me the information to do it. I went from cooking from cans and heating up frozen items to fermenting my own foods.” She admits her initial cooking attempts may have been packed with health benefits, but they weren’t particularly appetizing. “It was kinda just mush,” she says. “But within months, I was able to eat without suffering, and my food got better. I gradually cooked my way into wellness.” That was 12 years ago, and since then, Mee has been diagnosed with Celiac (most likely the cause of the ulceration) in addition to a severe dairy allergy. And yet, today, she’s living a full, whole life, enjoying the wellness she once only dreamt of. “When you’re dealing with these things, the pain isn’t the worst part — and I still suffer some — the worst part is not being present in your life and missing so many things,” she says. “Once I learned what a change in my food could do, I had to help others learn it too.” When she was feeling her worst, Mee prayed for relief and made a promise. “I told God I’d use my health to serve others, so that’s what I’m doing,” she says. She began by making some changes at Pinewood Farm. They were already raising good beef and pork but weren’t growing any fruits or vegetables, so Mee added 10 acres for produce, adhering to the holistic and integrated principles of biodynamic agriculture. Then she added beehives. Then logs in the woods to cultivate mushrooms. Then orchards for peaches, pears and apples. Then hoop houses and chickens. And finally, the farm switched its pork to pasture-wood raised and its beef to all grass-fed, using the same biodynamic techniques from the produce plot on its vast pastures. “We’ve built a whole world out here,” Mee says. She also sharpened her budding kitchen skills, enrolling in a culinary program to learn classic techniques, which she then tweaked to fit her own and a wide range of dietary needs. To deliver on her pledge to inspire others with her insights, she put out a cookbook and was doing cooking segments on “Today in Nashville.” Then, in 2015, her husband bought an old 1920s-era general store that sat at the corner of their land. “I really didn’t think it was a good idea at first,” she says, “but, then we decided to turn it into a restaurant supplied by the farm.” Mee was determined to feed her community using the bounty of food harvested from the farm, but during menu planning, she quickly discovered a dilemma. “I knew I could make all this nourishing food, but that wouldn’t do a thing if I couldn’t get it into people’s mouths,” she says, “so I had to meet my customers in the middle.” Down South, the thought that we can eat healthy and still tuck into the comfort-food dishes we’ve grown up on is, to many, pure fantasy. But Mee is proving it’s not. “I had to listen to what the community wanted; they wanted fried chicken, so I had to make the best fried chicken for their bodies,” she says. Blending outstanding nutrition and delicious flavors became her quest, a mission that’s perhaps most evident in her microbiome soups, with varieties like creamy sweet potato-lentil and zesty tomato, all containing a miso paste that packs a probiotic punch to support improved gut health. “Soups are a great way to get everything you need in one place,” she says. “They’re easy to digest, easy for folks to just heat up and eat.” They’re easy to ship too and are selling fast, alongside Pinewood jams and pickles. While Mee is committed to spreading her good food news, she’s not pushy. “If we are going to get society to change the way they eat, we have to bring them to the table with what they know, and then graciously share what we know to encourage the change,” she says. Mee’s table is long and open to all; the restaurant feeds

everyone, whether they’re in a position to pay or not. Often, Mee barters. “Two boys in the area raise chickens, and I’ll trade them meal cards to come eat for eggs,” she says. She does the same with a couple who grow plump backyard tomatoes. “They come in every weekend to eat Sunday dinner at the restaurant,” she says. Mee’s table is also welcoming for folks who often feel ostracized at restaurants. People with food allergies and other food-related diseases like hers can grab a seat, pick what looks appetizing and dig in with no worries; Pinewood Kitchen’s menu (which changes often to reflect the farm’s harvests) features multiple gluten-free, vegetarian and vegan options, and every dish can be made gluten-free, soy-free,

nut-free, dairy-free, vegan, paleo or keto. “Those who don’t suffer from these things really probably don’t understand how valuable that is,” Mee says. Mee’s heart is in the work she’s doing in her small rural community, but it’s not confined to it. She’s mailing her cakes, pickles, jams, soups and more all over the country, and Pinewood Kitchen draws diners from many miles away. When COVID hit, Mee was concerned about its impacts, yet her unease wasn’t as much about no longer serving her growing group of customers as it was her employees. “I have

Above: Married into the family that founded the Winn Dixie grocery store chain, Mee lives on part of the family’s Pinewood Farm. Today, all of the beef they raise on the farm is now grass-fed. Opposite: Produce plots adhere to holistic and integrated principles of biodynamic agriculture.

“THEY WERE ALREADY RAISING “ GOOD BEEF AND PORK BUT NOT GROWING FRUITS OR VEGETABLES, SO MEE ADDED 10 ACRES FOR PRODUCE.

about 100 people who completely rely on my business,” she says, “so I thought, ‘No. My people can’t go broke; I’ve got to get inventive.’” Mee needed to keep folks working on the farm, in the restaurant and in the canning kitchen. People all around her needed access to food, with shortages at grocery stores and fears about shopping inside. Her idea for Pinewood’s farm boxes met both. The boxes are filled with not just Pinewood produce, but baked goods, honey, canned items and Pinewood meats too, all neatly packaged and delivered straight to people’s doors in the surrounding areas, including Nashville and Franklin. “We call it farm-to-porch, and every box has little card in it that expresses what Pinewood is and the kindness that drives us,” Mee says. “In these dark days, I can’t believe my tiny country kitchen has become a beacon of light.” The boxes were an instant hit, pushing Pinewood’s sales up 600 percent during the height of the pandemic. The success means Mee will likely keep offering the boxes, even when COVID is behind us, and their popularity has expanded Pinewood’s overall footprint, motivating Mee to build a bigger commercial canning kitchen and a gluten-free bakery while she figures out how to ship the boxes across the country. “Sales have now increased 800 percent,” she says. “Keeping up with just the canning alone right now is insanity. Yesterday, I was watching orders come in and thinking ‘Hot dang! We sold another jar!’” Mee doesn’t hide her excitement when outlining the explosive growth of her business, but humility peeks through the girlish glee too. “I’m still a country gal at heart, and I once thought I’d have to go to a big place to do big things. But now, I know that’s not true,” she says. “We grow the best food and present the best food in this area right here at Pinewood, and we’re helping people with this food. That’s the best thing I can do with my wellness, pass it on.”

Top: Mee’s table is long and open to all; the restaurant feeds everyone, whether they’re in a position to pay or not. Center left: No one can tell that this chocolate mousse is made with avocados. It’s a great way to use up older avocados. Center right: Mee uses leftover beans, grains, and vegetables, to whip up Buddha Bowls that are great to have on hand for a meal on the go. Bottom: Mee sharpened her kitchen skills by enrolling in a culinary program to learn classic techniques, which she then tweaked to fit a wide range of dietary needs. Opposite: Today, Mee is living a full, whole life, enjoying the wellness she once only dreamt of.

CHAPTER 4

SOUTHERN SNAPSHOTS

Even the businesses are getting in on the House Float mania, Home Malone provides locally made artwork and decorations .

ALONG THE ROAD

Krewe of House Floats

NEW ORLEANS, LOUISIANA

Written and Photographed by Deborah Burst

If you have never been to Carnival in New Orleans, then you have not been formally introduced. It begins on January 6, Twelfth Night, with nearly two months of pageantry where an endless theater of creative souls flaunt their laissez-faire attitude parading on rolling stages of floats. It’s a telling portrait of a complex city fiercely devoted to its traditions, a mystical hamlet that casts a spell on all who enter, forever tied to the city’s fabled fantasies. But this year, an evil curse has invaded the city of New Orleans, a vile virus determined to devour their famed celebration. The powers that be declared the most dreadful mandate; there would be no parades, no floats, no bands, and no people. But nothing can steal the magic of New Orleans and her masked marauders; their inedible spirit has survived the carnage of floods and hurricanes, and they will rise again. Many locals refer to Carnival as Mardi Gras as it’s more than one day. There are eighty parades, close to sixty marching krewes, and an untold number of marching bands. An economic engine fueled by those who watch and those who ride. And suddenly it comes to a halt consumed by the ravages of a pandemic. So begins a story about guts and glory, loyalists from across the globe coming together determined to create their own 2021 carnival season. Imagine a new parade, a new krewe uniting the masses, no matter their race, locale, or political persuasion--a krewe by the people and for the people, the Krewe of House Floats. Let’s peddle back to November 2020, a time when most are working on their Thanksgiving menu, while many in New Orleans and beyond are generally knee-deep in glitter and papier-mâché. Megan Boudreaux, a resident of Algiers Point across the river from downtown New Orleans, was on Twitter sharing fond memories of carving carnival creations with visions of crafting giant fabric flowers. After a couple of tweet conversations, the wheels began to turn, and minutes later, an epiphany. Megan declared in a tweet, “It’s decided. We’re doing this. Turn your house into a float and throw all the beads from your attic at your neighbors walking by.” Megan is the Admiral of the float fleet with forty sub-krewe captains and maintains a tight krewe. “I am not sure there was one moment when I realized how big this idea really was,” confessed Megan. “It was a frenzied first month just trying to build everything from scratch, but thankfully many generous and talented folks stepped up to volunteer their time and skills.” The volunteers and sub-krewes dedicate their time and energy with tight deadlines from structuring the organization and consulting with city officials to developing a Krewe of House Floats map for the public to use to view the decorated homes. Social media posts light up with thousands of members sharing their crafty creations. People from all over the country and beyond, came together eager to break the pandemic boredom. Those outside the Greater New Orleans area, known as the Krewe of House Floats expats, do more than scrolling through the posts. Many belong to New Orleans parade krewes and marching groups. Jillian Whalen from Brevard, North Carolina, inside the Blue Ridge Parkway, witnessed her first New Orleans parades fifteen years ago and has been hooked ever since joining parade krewes and marching groups. “There is nothing like meeting new friends sitting on St. Charles Above: An avid part of the New Orleans Mardi Gras scene, Jill Whalen added her Blue Ridge Mountain critters Avenue waiting for a to her North Carolina House Float party Top: Don’t miss parade. Sharing food, the Tiki house float on Bermuda St. on Algiers Point, a historic hamlet that holds 140 house floats in a ten to drinks, and stories with thirteen block area decorated with the theme, “Staycation perfect strangers,” said Paradise.” Bottom left: Part of the Old Metairie Krewe, Edward Cox (L) and Vatican Lokey (R) make most Jillian with enthusiasm, of their designs from scratch in an effort to reduce waste. adding she wanted to Bottom right: Maria Dunn checks in from Sugar Land, Texas with her handmade Blue Dog posters installed craft a Mardi Gras float across her backyard patio.

that reflected her neck of the woods. “So we decided to have some local critters in Mardi Gras gear celebrating one of the overlooks along the Blue Ridge Parkway.” Many turned to everyday material in decorating their house and yard, while others reached out to those suffering from little to no business. Now artists, craft stores, and float builders work day and night trying to keep up with the orders. The pandemic has created a new normal, a mix of old and new traditions where many believe will continue for years to come. One of the premier float builders is Crescent City Artists. Owners Rene and Inez Pierre believe the porch floats are here to stay. “It’s a one of a kind masterpiece; many label our work as folk art,” noted Inez, adding they are dedicated in supporting age-old traditions and building new ones. “Keeping our history alive is a must, and porch floats is just the beginning.” Then there’s the royal couple of Carnival, Grand Marshal Marty Graw, aka Edward Cox, and Professor Carl Nivale, aka Vatican Lokey, known for their esteemed knowledge of Carnival history, along with the season’s revelry and artistry. Edward owns Simply Stunning Designs, where he designs theater sets, costumes, props, and more, but that all came to a halt with the onset of Covid-19. “We were five days away from opening a New Orleans premier and preproduction for five other major musicals, all completely shut down,” explained Edward noting it was just dribs and drabs, but now a feeding frenzy with Carnival artwork commissions. “We just earned three house floats in one day while working on a house float installation.” Imagine a city dedicated to the greatest show on Earth, and then it’s gone, canceled, an entire industry shut down. From doom and gloom came a glimmer of hope and a miracle was born. Could it be a fairy tale come true? Why not? After all, this is New Orleans. Her people reach across the globe, a force eternally tied to this storied city. Together they have found the answer to a world of woe, a creative camaraderie that knows no boundary. Check out the Krewe of House Floats Facebook group with 10,000 followers and a map detailing the decorated homes.

kreweofhousefloats.org

This page top: Meghan Davis has crafted a scene straight from Alice in Wonderland in Algiers with cards so real they look like they may leap in the air at any moment. This page center: Inez Rene Crescent City Artists owner Rene and Inez Pierre normally build floats, but now they are crafting porch floats where the homeowner buys the float façade seen here on Carrollton Avenue in New Orleans. This page bottom: Valerie Landry has one of the most envious homes on the property of the lauded New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival. It may be canceled but the Fest lives on, as the majority of decorations were hand made. Opposite: Another popular Algiers Point house float is the Lego Float complete with Lego krewe members throwing beads to the Lego family on the ground.

lay of the land

lay of the landWHAT DOES THE SOUTH MEAN TO YOU? OUR READERS SHARE PHOTOS OF THEIR SOUTH.

SHOW US YOUR SOUTH

Top: Photo submitted by Jefferson Ross, following the tracks, Marshall, NC Bottom left: Photo submitted by Mary Thomas Boyd, Rough Hornsnail at Weiss Lake, Cherokee County, AL Bottom center: Photo submitted by Leah Poole, blue crabs, Liberty County, GA Bottom right: Photo submitted by Patricia Blake, a few more minutes of playtime on the beach at sunset at Topsail Hill Preserve State Park, South Walton, FL Right: Photo submitted by Jenny Lawsky, Sam’s duck, Nashville, TN

SHOW US YOUR SOUTH