12 minute read

BY SOUTHERN HANDS

Q&A

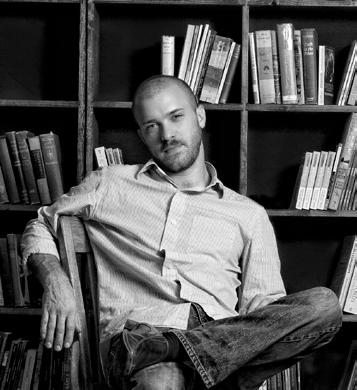

AUTHOR : FREEMAN VINES North Carolina native searches for the Mystical Tone

Advertisement

Written by J. M. McSpadden / Photography by Timothy Duffy

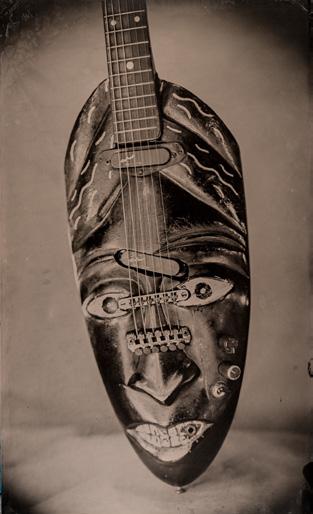

In September 2021, Bitter Southerner, in conjunction with the Music Maker Relief Foundation released a stunning book entitled Hanging Tree Guitars. It is the collaboration of luthier Freeman Vines with narrative by Zoe Van Buren and gorgeous tintype photography by Timothy Duffy. Duffy is the founder of the Music Maker Relief Foundation and has worked with Vines since 2015. Freeman Vines lives in Fountain, North Carolina, not far from the plantation his family once sharecropped. According to Vines, he has been making guitars for fifty years. Part visual artist, part spiritual philosopher, the book is Vines look at life and his encounters with racism. He approaches a piece of wood in a manner befitting a druid. Vines says that wood has a personality, and that personality informs each piece he creates. The title comes from a specific piece of wood that was delivered to Vines, wood from a tree that had been used to lynch a black man, Oliver Moore, in 1930.

Q : When did you first take up playing

guitar?

A : It’s been quite a while. Used to, when I lived on the plantation over there, I used to have to tote the… there was a bad white man over there. At least they said he was bad. But someone told me he was a nice guy. He toted his shotgun and his fishin’ pole all the time. I had no idea that during the hard times he wasn’t the only one hunting and fishin’ over there. I thought he was a bully cause every time I saw him…well, anyway, on to the important stuff. I was out there toting it for him and stuff and he had an old Martin guitar down there in the cabin. One day he went there and got it and he said, “I want you to meet Mr. Martin.” I was looking around and looking around and he had an old Martin’s guitar. He wouldn’t let me play it then, but later on he showed me how to play Wildwood Flower. And that was the beginning of the guitar. Q : When you started to learn the guitar who were your influences? A : Wasn’t no influence around cause there wasn’t but one road into the plantation and one road out and one car on the road with about fifteen or twenty people that sharecropped down there. Nobody knowed the way out except up to the general store or over to (the store at) Snow Hill. Q : So, you have lived in North Carolina

all of your life?

A : Yep. I done a little bippin’ and boppin’, but you know how it is, I’d always get broke and have to come back. Q : I lived in Wilmington, North Carolina

twice, the first time from 1969 -1979. There was a lot of racial strife there in those days.

A : I know, that’s why I got the hell outta there. I went down there riding with some folks. To get some herrings. This is in the days of the Saturday Night fish fry. We went to get some cheap herrings offa the boats. Q : Many people think of art as something

to entertain us. When I look at what you do with wood, I believe your art challenges us.

A : Right. Well, you have to sit there and look at the guitar to see what it’s saying. Cause the wood itself already has that personality, that it makes me do things. Cause see, a lot of them are, cause of losing my eyesight, were done with about 1/3 of my vision. People come down there and ask me how do you cut the guitar out and assemble it. I say ‘Simple. When I run into a problem I make a tool to compensate for what I can’t do.’ I did the same thing when I restored cars. They stole all my tool designs and made them some purty tools, and painted them and stuff, but my old raggedy-looking ones did the

same thing. Q : When did you first start making guitars? A : Way back…God almighty, when that ice storm struck down here. It’s been at least 49 or 50 years ago. Q : Were you working for a guitar maker or for yourself? A : I’d never heard tell of a guitar maker. Didn’t even know what a guitar was unless it was a beat up old Stella, that people would throw away and you’d get it and try to mess with it. I fooled with trying to electrify the guitars. Q : In the book you talk about searching for a tone. A tone that you heard that

has haunted you. Where did you hear this tone?

A : What happened was, I had a little place I’d bought, a half of a truck that I made me a shop in there. I stepped out one evening and what happened was… you ever bumped your elbow and that funny feeling you get in your arm? What they call ‘hitting the funny bone?’ Well, that happened to the whole body. I couldn’t move, I couldn’t talk, and I couldn’t see at that time. It controlled the whole body. It’s hard to describe, but it left a tone in my head for quite a while there, and it bothered me real bad. I thought about going to a psychiatrist. It (the tone) kept getting lower and lower, after a while it left. But I ain’t ever heard that sound before, it was so John Brown pleasin’ and felt so good till if that’s what death is like I might die, I don’t know. Q : Can you still hear that tone? A : Never heard it no more. Here is where it messed me up, see. You probably think B.B. King is a big guitarist. Or maybe Jimi Hendrix. Don’t mean nothing to me. The onliest man that impressed me playing the instrument is a blind man named Doc Watson. I don’t know how he do it, must be a spiritual thing with him. He dead now. If he make a lick, the other strings compliment that lick. He don’t have to hold that one string and use pedals and stuff. You can sit right there and mellow out on his music. Here’s how that (tone) ruined me. I used to be listening to Hendrix, and Zeppelin, and I’d be happier than a mule eating briers. But after that I started listening to it, and what each string was doing, and the effects coming in, and it just didn’t sound good. Until I heard that dude named Doc Watson. Q : The tone is gone. Do you think you will ever find it? A : If a man find that tone, and have the right instrument, he could control…I don’t want to say he could control people. But he could make music no one could compare him with. I got a lot of unusual instruments that I made, but they don’t have that tone. Q : You said that the wood has character. Does the wood reveal itself to you? A : You don’t want to mess with the wood until you communicate with it, spiritually and mentally. Which they called me a nut, but I don’t care. A whole lot of stuff came out of that hanging tree, which scared me. Tim (Duffy) got what he called the conclusive evidence that it was the wood. He even associated with a woman that her grandfather was one of the ones that did the hanging. It be something wrong with that wood. If you ever get the chance to mess with it you’d say that that old dude told the truth. Nothing made out of that wood was beautiful.

Learn more at hangingtreeguitars.com You can also find the full length version of this interview at villagenightowl.buzzsprout.com

Left: Freeman’s Bodies, tin-type Right: Death Mask, tin-type

LISTEN UP

HARD WORKING MAN

ANDREW ALLI: RESPECTING TRADITION

Written by Joseph McSpadden

For Richmond-based blues harp player Andrew Alli, the blues is about more than feeling bad. He didn’t come to the blues directly, but a chance encounter with a busking musician lit a fire in Alli that he had to feed. Alli grew up in a home surrounded by music. “I have always been a music lover. I grew up around my family, always playing music in the home. Motown, soul and gospel records. I’ve really been moved by all types of music. That opened me up to those genres. None of my family members were musicians, as far as instruments were concerned. My family loved to sing and dance and it was always around me.” While he didn’t pick up the harmonica until college, the air around Alli was saturated with songs. One of four children, Alli has three sisters, the family was close. “We were very creative little kids. We would make up songs and dances. We kept ourselves busy, even writing little jingles as a kid. Looking back, I didn’t realize how that influenced me and how I look at music even today.” Despite being surrounded by those musical styles, Photograph by Bob Hakins he was never exposed to the blues. That changed when he got to college. He was inspired by seeing a busker playing harmonica on the street one day. The young Alli was motivated to get his own harmonica that same afternoon. “I thought, I could be a musician as well. That day changed the way I thought about myself. I saw myself as a real musician.” The acquisition of his first real instrument launched Alli on a journey to learn how to play it, and to listen to artists who were considered masters of the mouth harp. He delved into the history of the instrument and discovered that blues and harmonica go hand-in-hand. “Once I started getting into those blues records, it was over. I heard those sounds and knew this is all I want to play.” Pursuing the blues became his focus and he wanted to learn everything he could. “Of all the big harp legends, Big Walter Horton really spoke to me. His tone, and his acoustic playing, all of that made him a big early influence.” He began to absorb everything he could, searching out old recordings. Washington, DC’s own Phil Wiggins became another huge inspiration. He loved hearing the different styles and approaches to the instrument. “I hate to say I have a favorite, but Big Walter really influenced me with his style and the way he played acoustic blues harp.” In 2020 Alli released his first album, Hard Working Man. The recording clearly shows that Alli not only has the chops, but also that he respects the tradition of blues harp playing. The record sounds very much like many of the Chicago blues albums of the forties and fifties, not only in his playing but in the band arrangements and in his vocal style. “I love how that era got influenced by…these really sort of jazzy guitar approaches and groove. It is the pinnacle of the blues sound that I like. It all came together in that mix of jazz and blues and jump and swing. It was tone and groove-centric.” For listeners who cherish those moments in music, it is inspiring to find an artist that can walk the line between old and new without losing the integrity and respect for the past. Case-in-point; of the twelve tracks on Alli’s debut, nine are originals. The three covers are songs by George Smith, Big Walter, and Little Walter. Alli’s compositions sit comfortably alongside the classics and fit seamlessly with songs from the golden era of Chicago blues. Blues Blast Magazine commented that “Alli’s debut, Hard Working Man, is a fully realized artistic statement of the blues.” His tenor voice and his vocal phrasing mirror the style and warmth of Little Walter without swerving into imitation. Writing new blues can be challenging in 2021. Honesty and authenticity can be elusive. There are a lot of players who can toss off a technically perfect lick, but the record also has to have that feel, that sense that the artist means business and isn’t just showing off. Fortunately, Alli, and his bag of original songs is the real deal. “The songwriting has been a bit of an evolution. I want to stay true to the music and also give something of my own to it as well.” Like most of his peers in the music business, Alli found 2020 to be a tough year. Gigs were cancelled, opportunities put on hold. “It’s tough. I’ve done a few online things but it feels kind of weird. I think, especially with the blues, that the artist feeds off the energy of the audience in a live setting. It feels weird to finish a song and there is just silence. It’s hard to feed off of that. I’ve been woodshedding this last year, trying to develop my sound a little more.” But the shutdown can in some ways lead to inspiration. “I’ve been writing more. I have a whole bunch of new unfinished songs. I’m making progress, putting some finishing touches on stuff. I’m hoping to get some recording done, new stuff in 2021.” Alli intends to return to Bristol, Virginia and Bigtone Studio for his sophomore effort. He enjoyed making the debut record there so much that he can’t wait to get back. “I really like the sound they are getting. It’s all analog recording. That warm, authentic, organic sound.” Alli doesn’t have one approach for songwriting. “It could be the groove, like if I had a lick or something. Just sort of build the song around this groove. Another time it might be the lyrics, an experience I had. I wouldn’t say I have one way. I try to be open to different ways to tell a story.” “A lot of people say the harmonica is like an extension of your voice, and I agree. You’re not going to find two harp players that sound alike. It’s nice to mold that sound to make it something special to you.”

andrewallirva.com buzzsprout.com/737303