6 minute read

World’s Most Modern Superhighway— The 1955 Ohio Turnpike

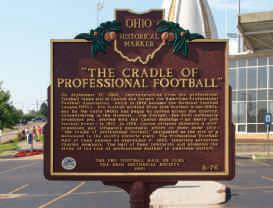

A Chevrolet pick-up truck approaches a toll booth on the Ohio Turnpike. The patrol car on the left is a Dodge Coronet, which was powered by a 354-cubic inch Hemi engine boasting 340 horsepower.

Courtesy of Ohio Turnpike Commission World’s Most Modern Superhighway THE OHIO TURNPIKE BY ERIN ESMONT

It was a frigid March weekend in 1965 when Harlan Adkins first stepped inside an Ohio Turnpike toll booth. The small structure had no heat, and he was freezing.

He thought that picking up shifts as a toll booth operator would be a good way to supplement his wages as a machine operator at the General Metals Powder Co. He had a young family to support. After two shifts in the toll booth, he went home and told his wife, Belva, he didn’t think it was the job for him. Give it another try, she suggested. “I went back on Sunday and, well, I’ve been back there ever since,” he said during a phone interview in July, shortly after resuming shifts curtailed by the pandemic. EXIT 193

Adkins, 84, of Ravenna, collects payments from motorists passing through Exit 193 at Ravenna and holds the distinction of being the Ohio Turnpike’s longest-serving employee. His longevity is just a decade shy of the turnpike itself, which marks 65 years of operation this October. The observance arrives in the midst of a 100-year pandemic that brought dramatic drops in traffic and tolls in the spring. Traffic patterns crept back up to just below normal as summer approached. Full-time employees kept their jobs and alternated work weeks; part-time employees like Adkins worked less or not at all, per usual in winter.

When Adkins returned to his toll booth in late June, masks, gloves and Plexiglas became standard issue. Executive Director Ferzan Ahmed put a premium on worker and customer safety, shuttering service plazas during the worst weeks. Many—but not all—reopened by summer with reduced hours.

THE MODERN TOLL ROAD

In 1940, Pennsylvania led the nation in designing and building a modern toll road. Ohio transportation officials and business leaders saw the economic potential.

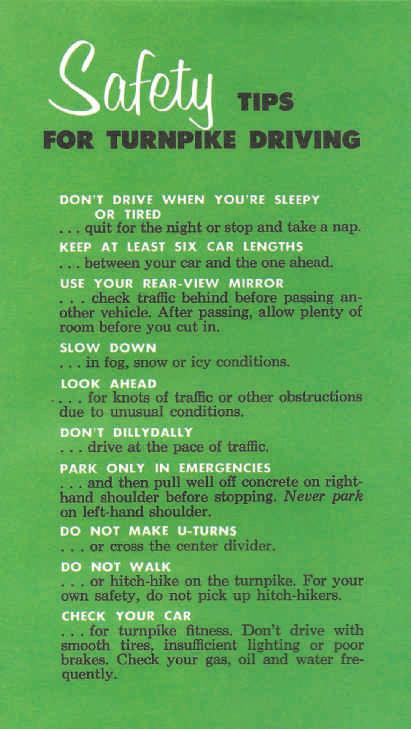

They envisioned an east-west corridor in the northern part of the state that would link to Pennsylvania’s and connect to Indiana. Truckers could move food and goods at top speeds on uncongested roadways. And not a moment too soon. The postwar boom sped up consumer car-buying, and the shift to suburban living made owning one essential. It wasn’t long before existing roads were clogged with stop-and-go traffic. The Ohio General Assembly created the Ohio Turnpike Commission in 1949 to build a turnpike with the latest safety features—center divisions, ample shoulder widths, sensible grades, long sight distances and multiple lanes in each direction— financed by revenue bonds.

MOVING THE EARTH

It took vision and grit—and enormous earth-moving equipment—to claw at tons of dirt and rock and push it into something resembling a roadway. Giant cranes hoisted iron and steel girders hundreds of feet in the air to span rivers and valleys. The turnpike opened in two sections on different dates. The first became operational on Dec. 1, 1954, a 22-mile section connecting to the Pennsylvania Turnpike—a first between two major toll routes. When the rest was completed on Oct. 1, 1955, it capped a mammoth construction project that at its peak employed more than 10,000 workers powering 2,300 bulldozers, graders, loaders and other roadbuilding equipment, according to Brian Newbacher, the turnpike’s public information officer. For maximum dramatic effect, and to meet a tight deadline, the turnpike opening happened at 12:01 a.m., under a full harvest moon, one newspaper noted, as reporters and photographers captured the action.

Throngs of people gathered to hear Gov. Frank Lausche’s remarks accompanied by the Bryan High School band and choir, while cars, bumper to bumper, waited to ease down the road behind a state patrol car. A deliveryman from Chicago got stuck trying to cross the center strip and had to wait 90 minutes for a tow truck. His truck bed was full of furniture destined for the service plazas. Mrs. Nina Johnson, an Angola, Indiana, housewife, was first in line, arriving early to be the first paying customer, according to the Toledo Blade.

BEAUTIFUL, SAFE, COMFORTABLE

On the eve of the official opening, The Cleveland Press reported: “It’s a beautiful road, a safe road and a comfortable road, and it is important economically to hundreds of thousands of citizens. It was built without politics, without graft and with no variation from strict principle.”

FINISHED IN 38 MONTHS

The turnpike was finished on time and $8 million under budget, the newspaper reported. At first, getting everyone on the same page wasn’t easy—idea to inception was fraught with political maneuvering, legal bickering and Ohio Supreme Court rulings. “There were fights between suppliers, fights between whole industries. There was a terrible row about service plazas,” The Cleveland Press reported.

One man—James W. Shocknessy—was credited with having the sharp focus and discipline needed to finish the 241-mile turnpike in a remarkable 38 months. He served as the turnpike’s first chair, wielding considerable authority, as detailed in The Cleveland Press in 1955:

To commemorate his efforts, the turnpike officially bears his name. Toll booth operator Harlan Adkins wasn’t at the opening ceremony, but says his father-in-law, state trooper Robert Jones, was. A BRIDGE TOO FAR

Adkins told of a memorable encounter Jones had with a nervous, first-time turnpike driver. An older woman had second thoughts as her car approached the enormous twin two-lane bridge over the Cuyahoga River Valley. It spanned 2,650 feet and reached 175 feet above the valley floor.

She chickened out and refused to drive over it, Adkins recalled, so his father-in-law got into the driver’s seat of her car and drove her to the other side. (He walked back across the bridge, which has since been demolished and replaced, Adkins says.) From his toll booth perch, Adkins has witnessed many changes: When he started, there were no lunch breaks, and bathroom breaks on the midnight shift meant posting a sign on the booth – “Be back in 5 minutes.”

There were only 17 gates along the entire turnpike; now there are 31. Service plazas then featured sit-down restaurants, many operated by Howard Johnson’s, a popular chain of the era, advertised as the “Host of the Highways.” Now, mostly fast-food establishments and 7-Elevens serve on-the-go eaters. The expansion of the turnpike from two lanes to three was a massive and tricky multi-year undertaking, Ahmed says, that involved widening 160 miles of roads and bridges while traffic still flowed. Adkins remembers when toll booth operators wore two different uniforms—one in summer and one in winter—topped with a police-officer-style cap. (Today, they wear black pants and gray shirts.) When women started working there, they wore skirts until pants became an acceptable option. Soon toll booths featured heating and air conditioning that made seasonal changes bearable. The advent of the E-Z Pass in 2009 meant Adkins conversed with fewer motorists, but a large number of drivers still slow down to pay and say hello. Adkins expects to be in the toll booth this fall, but he’s thinking seriously about retiring in December. He tried to retire once before, but staring at four walls didn’t suit him.