9 minute read

Remember the Maine Ohio’s Spanish-American War Artifacts

Photo: Library of Congress | Overlay: Naval History and Heritage Command

Remember the Maine

OHIO’S SPANISH-AMERICAN WAR ARTIFACTS BY DAVID A. SIMMONS

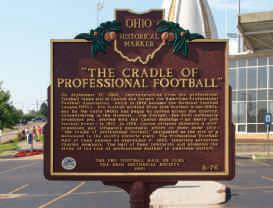

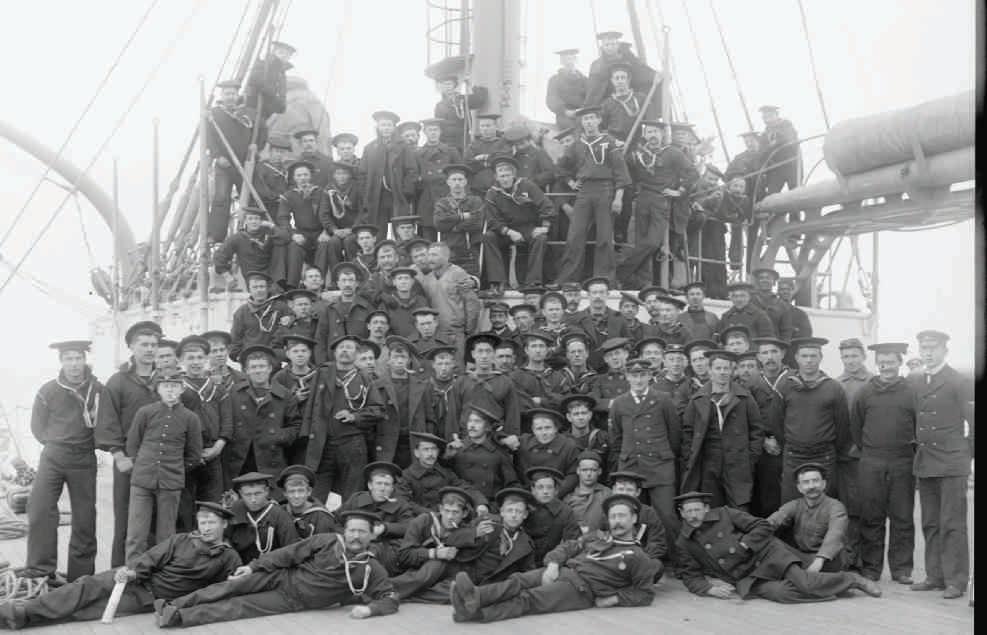

Throughout American history, battle cries have stirred numbers of ordinarily peaceful citizens toward armed conflict. When the USS Maine was commissioned in 1895, it lay at the cusp of American naval technology—a 324-foot steel battleship with four breech-loading 10-inch rifles and half a dozen lesser guns scattered about the vessel.

But innovative construction was not why “Remember the Maine” still resonates more than a century later. Instead, events leading up to the brief hostilities between Spain and the United States placed it at the center of one of American naval history’s unresolved controversies. THE MAINE AND CUBA

Throughout the late 1890s, tensions ran high between Spain’s extraordinarily repressive colonial government in Cuba and the rebel forces determined to gain independence at any cost. By early 1898, the jittery American consul general to Cuba, ex-Confederate general Fitzhugh Lee, was increasingly worried about U.S. assets on the volatile island.

President William McKinley Jr., however, leaned strongly toward pacifism—the sight of piled up corpses from the Civil War still haunted him after more than three decades. Still, in January, the pair combined efforts to order the USS Maine to Havana. Sending the battleship to Cuba involved considerable risk and had heavy overtones of provocation. So the explosion on the night of Feb. 15 that destroyed the Maine—killing 252 seamen outright while the ship was quietly moored to a harbor buoy—could have been predicted. And the reaction of many in the American public to the event was also not a surprise. The New York Journal, published by William Randolph Hearst, had long circulated stories of Spanish colonial atrocities in Cuba, and the paper immediately jumped on the wagon of those placing blame for the explosion squarely with Spain. War sentiment within the nation rose precipitously.

Cleveland Metroparks

Above: Dedicated in 1913 and moved to its present site in 1948, the Battleship Maine Memorial near the entrance to Washington Park in Newburgh Heights, Ohio, features a piece of the ship's conning tower and a porthole. Left: The Maine was powered by coal-burning steam engines. Some suggested that the placement of ammunition magazines immediately adjacent to several coal bunkers in the original design may have accidentally caused an explosion.

CAREFUL CONSIDERATION

President McKinley was more circumspect, insisting before rushing to judgment that a naval court of inquiry be held to determine whether the vessel’s destruction was from internal causes—an accident— or external ones, meaning a mine. A Naval Board of Inquiry was quickly set up and, after reviewing evidence for a month, officially blamed the Maine’s loss on a mine. Within a month, Spain and the United States were at war.

The United States was largely unprepared for the conflict. While the navy had built significant technological achievements like the Maine since the end of the Civil War, it was still relatively small, and the army was short of staffing, equipment and training. What the nation lacked in military strength, however, it tried to make up for in enthusiasm. The famous charge up San Juan Hill by Teddy Roosevelt and his Rough Riders was still a month in the future when William Cotton, a Columbus hatmaker, gave a stereopticon talk on the Maine explosion and other scenes in Cuba at a local masonic hall.

He was repeatedly interrupted by hisses and cheers depending on how well the topic reflected on America’s fortunes. The fighting in the SpanishAmerican War, including battles on land and sea, was over before the summer ended, and peace was declared prior to the New Year.

Hayes Presidential Library & Museums RETRIEVING THE REMAINS

After the war, the wreck of the Maine remained in the Havana Harbor, where nagging questions persisted over the actual cause of the explosion. Numerous European naval specialists had been quick to raise questions about the court of inquiry’s decision, suggesting that a design flaw in the placement of coal bunkers adjacent to ammunition magazines could have caused an accidental explosion. Harbor officials requested removal of the navigation hazard caused by the wreck. Furthermore, the remains of the American sailors had never been repatriated, and numerous patriotic organizations around the nation were petitioning Congress for mementos from the vessel for memorial use.

Not until 1910 did Congress authorize recovery funds. The following year, an American steel company built a cofferdam unprecedented in its scale and depth around the wreck to expose the remains for careful examination by naval experts. President William Howard Taft appointed a new five-man Naval Board of Inspection and Survey. After reviewing the physical evidence and considering all the views of those suggesting an accidental cause, the board affirmed the basic finding of the 1898 court: a mine caused the explosion. Half of the ship was intact enough to refloat, so it was towed out into the ocean nearby and sunk with full

Canton City Parks | Doug Foltz, Photographer Left: This capstan from the USS Maine is in Fremont's Rutherford B. Hayes Museum. Right: A veterans’ group orchestrated the effort to obtain a USS Maine artifact in martyred president William McKinley’s hometown of Canton, Ohio. Now located in Westbrook Veterans Memorial Park, what was the base of the vessel’s conning tower became our state’s largest fragment.

The explosion of the Maine on Feb. 15, 1898, while it lay anchored to a harbor buoy in Havana had international implications. Even after two official courts of inquiry, the precise cause remains controversial more than a century later.

military honors “appropriate to mark the end of a fighting ship.” Still, a significant amount of wreckage was left behind to redistribute to those demanding memorials. A 1912 editorial in Scientific American was quick to emphasize that since only municipalities and military associations could receive pieces—avoiding exploitation by “professional showmen”—the “dignity of the nation” would be preserved. Eventually, the War Department filled a warehouse at the Washington Navy Yard with material, where remnants could be reviewed and selected for installation around the country. So many took advantage of the opportunity that today naval historians joke that the USS Maine is the longest vessel in American history since pieces of it can literally be found from coast to coast. OHIO’S PREMIER COLLECTOR

Col. Webb C. Hayes, son of President Rutherford B. Hayes and a veteran of the headquarters staff during the 1898 Cuban invasion, prominently lobbied for Maine artifacts. He made his requests through city officials in Fremont, where the Hayes family’s estate, Spiegel Grove, was located, and through the local chapter of the Grand Army of the Republic. Col. Hayes had been among the first state commissioners appointed to erect a monument commemorating the centennial of Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry’s victory in Lake Erie over British naval forces during the War of 1812. At one time, a naval museum was planned as part of the memorial, and Hayes aggressively sought artifacts from a variety of sources, including the Maine. By 1917, the museum concept at the Perry memorial had been abandoned, and as a consequence, multiple pieces of the vessel eventually found their way into the collections of Hayes Presidential Library & Museums in Fremont.

Two elements of the ship’s deck equipage, a capstan and accompanying driveshaft, can be found today displayed in the Hayes Museum’s weapons gallery. Other smaller items, such as a piece of steel rope and several cog gears, are in storage.

The mainmast of the Maine dominated the wreckage in Havana Harbor, and American sailors were allowed to place a flag at half-mast upon it. The mast itself ended up at Arlington National Cemetery.

Demand for Maine artifacts seemed relentless, so Navy Yard artisans melted down components so mangled as to be virtually indistinguishable to create commemorative plaques. Plaques of this type were reportedly sent to Dayton, Berea and Elyria, and also ended up in the Hayes collections. CITY CLAIMS

Larger components of the Maine were placed in several Ohio cities. A Spanish-American War veterans group in Canton, President McKinley’s hometown, obtained a 25-ton fragment of the ship’s superstructure, taken from the base of the conning tower.

Originally it was placed in the city park near the McKinley National Memorial, where the assassinated president was entombed in 1907, but in recent years it was relocated to the Westbrook Veterans Memorial Park on the west side of I-77.

The War Department donated a slightly smaller Maine fragment, a 6,700-pound truncated segment of a mast and a porthole cover, to the city of Cleveland in 1912. It was mounted in a traffic triangle in Washington Park, a Cleveland Metroparks site in Newburgh Heights, in 1948. OHIO’S ODDEST MAINE ARTIFACT

Probably the oddest Maine artifact to make its way to Ohio—along with the story surrounding it—was Capt. Charles Sigsbee’s enameled-steel bathtub. Frank B. Willis, U.S. representative for the district that included Urbana, obtained the tub for his constituents in that city. When the tub was delivered and put on display on the Champaign County Courthouse lawn, the Cincinnati Enquirer published an article poking fun at the gift. Urbana clubwomen became indignant at the ridicule and demanded that the gift be returned. In its place, they insisted on a more respectably militaristic artifact, like a 10-inch shell casing. (If that was ever delivered, its whereabouts is no longer known.) E. Lincoln Groves, mayor of Findlay, also in Willis’s district, jumped at the chance to claim the unwanted Maine artifact, by then ignominiously relegated to the Urbana mayor’s chickencoop. Findlay considered itself uniquely qualified to identify “a realistic patriotic use” of the unusual relic “for the admiration of future generations.”

The crew of the Maine consisted of 355 officers and men. Some 267 of them never left Havana Harbor alive.

City newspapers solicited suggestions from local residents. Some took the question seriously, but others couldn’t resist a bit of levity. Distinguishing between the two can be hard from a century-long perspective. One doctor, for example, suggested installing the tub in the courthouse yard by christening it with champagne like a battleship! Not until late winter of 1913 did the tub arrive in Findlay, and, by then, the novelty had largely worn off. Set in a city hall corner while awaiting a permanent location, the tub was mistaken for a coal bin and piled full. That led to cries of desecration and inspired a local veterans group to raise funds for a respectable display under glass in the courthouse. In 1960, Hancock County offered the artifact to Findlay College’s new museum. But the glass case was quickly repurposed for other displays and the tub was consigned to storage. When the college museum folded in 1971, the tub finally found an honored place in the Hancock Historical Museum’s exhibits in Findlay. Today, a multitude of Maine artifacts remains to connect Buckeyes to the events leading up to the Spanish-American War. While short in duration, the war fostered an unprecedented period of military and economic ascendancy for the United States that still has implications for us today.

David A. Simmons recently retired after 44 years as a historian with the Ohio History Connection, having worked in the State Historic Preservation Office and on the staff of Timeline and Echoes Magazine.

LEARN MORE LEARN MORE

For more information on the USS Maine and its place in American history, read A Ship to Remember: The Maine and the Spanish-American War by Michael Blow and Remembering the Maine by Peggy and Harold Samuels. Find a comprehensive listing of Maine artifacts on the Spanish-American War Centennial website spanamwar.com.