11 minute read

Ohio Wins No Matter What— The 1920 Presidential Campaign

Ohio Wins No Matter What

OHIO AND THE 1920 PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION BY BILL EICHENBERGER

If either the Republican or Democratic candidate won the 1920 presidential election, two things would be guaranteed: the president would be from Ohio and a newspaperman.

Warren G. Harding, who’d been in politics since 1899 as a state senator, lieutenant governor and U.S. senator, owned the Marion Star from 1884 through his death in 1923. His opponent, James M. Cox, a popular three-time governor of Ohio, bought the Dayton Evening News in 1898, renaming it the Dayton Daily News a week later. (Cox is the Cox in media powerhouse Cox Communications, which was later purchased by Cox Enterprises.) The election was the only time two Ohioans—three if you count Prohibition Party candidate Aaron S. Watkins—ran against each other. Both candidates’ journeys to their respective party’s nominations were shrewd and calculated. Harding did not attend the Republican National Convention. Cox did not attend the Democratic National Convention. (It was deemed unseemly back then.) Harding won on the 10th ballot at the Republican National Convention and Cox on the 44th ballot at the Democratic National Convention.

FRONT PORCH CAMPAIGN

But as much as the two candidates had in common, their campaigns couldn’t have been more different. Harding decided to run a “front porch” campaign like his hero William McKinley, who ran in 1896 from his own front porch. People came by the thousands to Harding’s hometown, Marion, to hear him speak. Cox, on the other hand, traveled the country from coast to coast, taking his campaign “to the people,” visiting “every doubtful state.” Before it was over, Cox had been to 36 states, covered 22,000 miles and delivered 394 official speeches. Sherry Hall is the site manager at the Warren G. Harding Home and Memorial in Marion. Though Harding had stiff competition for the nomination (including two future presidents, Calvin Coolidge and Herbert Hoover), he was hardly an anonymous candidate. A POLITICAL VETERAN

“He’d been in politics for 20 years and in the U.S. Senate since 1915,” Hall says. “Adding to that, Harding was a very popular speaker, a good speaker in demand at Republican clubs throughout the country. In his papers we have dozens of letters inviting him to speaking engagements.” Cox may not be as well-known today, but in the 1910s he was influential in the Dayton area and at the national level in the Democratic Party.

Mary Kay Mabe, a professor at Sinclair Community College near Dayton, teaches a History of Ohio course and has read everything she can get her hands on about James Cox.

UNDERAPPRECIATED

“It’s really a shame he’s not better-known,” Mabe says. “Even in Dayton he’s something of a forgotten figure. He was just so private and didn’t really have anyone to promote his image after he died. But during his day, he was a champion of his community and stood shoulder to shoulder with business leaders such as inventors Charles F. Kettering and John H. Patterson.”

Harding only had one significant misstep on his way to the Republican nomination, but it was one that nearly derailed his campaign. He suffered an embarrassing drubbing in the Indiana primary, failing to secure a single delegate, and threatened to quit the race before his wife, Florence, interceded. In one version of the story, she asked her husband, “Warren Harding, what do you think you’re doing?” Then she picked up the telephone receiver and yelled “You tell (Harding campaign manager) Harry Daugherty … that we’re in this fight until hell freezes over.” HARDING REBOUNDS

Harding rebounded with a speech in Boston that would, according to Harding biographer John Dean, “resonate throughout the 1920 campaign and history.” Dean says Harding entered the Indiana primary only reluctantly and was convinced by his wife to stay in the fight. “In his speech in Boston,” Dean says, “Harding assessed what the nation needed in the next president: ‘America’s present need is not heroics, but healing; not nostrums, but normalcy; not revolution, but restoration; not agitation, but adjustment; not surgery, but serenity; not the dramatic, but the dispassionate; not experiment, but equipoise; not

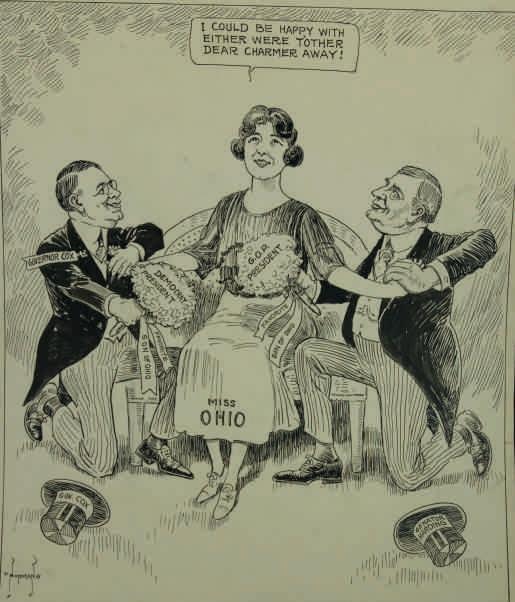

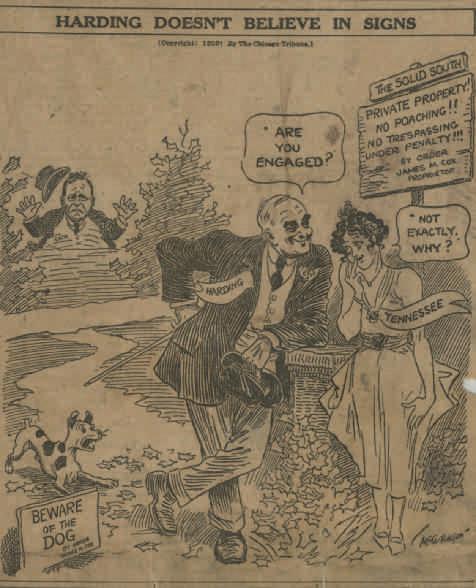

Left: A cartoon from the Chicago Tribune depicts Harding courting Tennessee in what was then considered for Democrats “the solid South.” Harding took Tennessee and became the first Republican president to win even one of the 11 states of the former Confederacy. Right: Ohio was in the catbird seat for the 1920 presidential election: no matter who won, the president would be from Ohio. In this cartoon, “Miss Ohio,” wooed by both candidates, confides, “I could be happy with either.”

submergence in internationality but sustainment in triumphant nationality.’ “It was pure Harding, who often used such wordplay in his editorials for the Marion Star. Everyone but newspaper columnist H.L. Mencken liked it.” PEACE WITH HONOR

Meanwhile, Cox was running (with his vice presidential candidate, Franklin D. Roosevelt) on the campaign poster promises of “Peace with Honor” and “Peace~Progress~Prosperity.” This made sense. For two decades, Cox had been a leading Progressive Era Democrat.

In his book, James M. Cox: Journalist and Politician, historian James E. Cebula writes that Cox’s acceptance speech at the Democratic National Convention was an effort to “broaden the base of the Democratic party.” The speech “reflected his orderly outlook toward voting blocs.” So Cox “urged ratification of the women’s suffrage amendment. He believed that the progressive nature of the Democratic platform would appeal to women’s ‘natural’ humanitarianism.”

He was more circumspect about Prohibition, Cebula contends. “Rather than alienate the drys, he ignored the question (altogether).” Mabe says Cox—often considered a ‘wet’ candidate— walked a fine line. “He told voters, ‘If Prohibition is the law, then I will uphold the law.’” But it was always going to be an uphill battle for Cox, who was in the unenviable position of needing to court then-president Woodrow Wilson’s support while distancing himself from Wilson’s proudest achievement, the very unpopular League of Nations, which had been voted down by the Senate. It didn’t help matters, either, that Socialist party candidate Eugene V. Debs and Democratic stalwart William Jennings Bryan regularly attacked Cox. (Debs eventually garnered more than 900,000 votes.) Both candidates talked on the trail about the notion of America First, which means something different today than it did in 1920, Hall says. “The phrase has been used a lot,” Hall says. “In fact, Woodrow Wilson ran on America First. But when Harding talked about America First, he did not mean America Alone. He felt strongly that America should be an example for the world, that it should help the rest of the world. He’d say, ‘We want to work with the rest of the world.’”

Gov. James M. Cox of Ohio and Franklin D. Roosevelt of New York arriving at the White House for a conference with the president in 1920.

THE ADVERTISING AGE

Perhaps not surprisingly, given that both Harding and Cox owned newspapers, the 1920 election is often said to have been the first campaign in the Advertising Age. “When Harding was told about the availability of Albert Lasker to assist his campaign, he was all for it, and gave Lasker authority to employ his skills,” Dean says. “Lasker was the head of Lord & Thomas, a Chicagobased advertising firm. As his biographer notes, Lasker introduced many of the modern political advertising techniques in 1920. Lasker used radio, newspapers, magazines, movie clips, sound recordings and billboards to sell Warren Harding to American voters.” In the end, Harding won in a landslide that 100 years later seems inevitable. Harding, who was one of the most popular presidents ever, died during his third year in office. Scandals that came to light after Harding passed—Teapot Dome and his marital infidelity— tarnished his reputation. That still irks Hall.

THE WORST PRESIDENT OF ALL TIME?

“The biggest myth about Harding is that his presidency didn’t accomplish anything,” Hall says. “He authorized

Both Cox and Harding were newspapermen, but Harding enjoyed the best press during the 1920 campaign. “Harding had a unique rapport with newsmen covering his campaign,” says Harding biographer John Dean. “It will be recalled that he built a special office behind his home for newsmen during the campaign.”

the Veterans Bureau, the precursor to the VA. He provided soldiers returning from the war retraining to help them reenter the workforce. He authorized the Bureau of the Budget and gave the country a coordinated federal budget for the first time.” John Dean concurs.

“Unquestionably the greatest myth about Harding is that he was one of America’s worst presidents, and that he was corrupt,” he says. “Most scholars I have talked with about Harding—including those who often vote in ranking presidents for national publications— know almost nothing about Harding. “When I wrote my biography of Harding (published in Times Books’ American Presidents series in 2004) for historian and the series editor Arthur Schlesinger Jr., whose father had started the first presidential ranking that made Harding one of our worst presidents, I found that he knew almost nothing about Harding.” Rather, Dean says, Harding was “one of the nation’s better presidents, reversing the racism of his predecessor, accomplishing the first great disarmament treaty, creating the Bureau of the Budget which placed the federal government on a strong fiscal footing and ushering in the Roaring Twenties.”

LEARN MORE LEARN MORE

Warren G. Harding by Marion native John Dean is a lively, well-researched and succinct biography of Ohio’s last president. In chapters such as “Young Harding,” “Editor, Publisher, and Apprentice Politician,” “The 1920 Campaign” and “Death and Disgrace,” Dean resurrects Harding’s reputation and entertains while doing it.

In 1985, historian James E. Cebula published James M. Cox: Journalist and Politician, following the Daytonian’s life from childhood through newspaper ownership, his three terms as governor and his unsuccessful presidential campaign in 1920.

Sherry Hall is the author of Warren G. Harding & the Marion Daily Star: How Newspapering Shaped a President. Rather than treat Harding’s newspapering as a footnote, Hall’s book presents Harding “as he saw himself: as a newspaperman.” Harding remains the only member of the Fourth Estate to occupy the White House.

James M. Cox’s memoir, Journey Through My Years, is a flawed-but-engaging recollection. In his Foreword, Cox explains, “yet what I saw, not what I did, is the important thing (here).”

Though 35 of the required 36 states had ratified the 19th Amendment by the end of March 1920, approval by a 36th state still remained uncertain in August, and suffragist Alice Paul wasn’t taking any chances. On Aug. 14, she exhorted both Warren G. Harding and James M. Cox to bring the amendment home. “There is every evidence that the national leaders of both political parties have up to this time put their shoulders to the wheel,” she said, adding, “the result will depend entirely upon the efforts of Governor Cox and Senator Harding and the national parties.” Four days later, Tennessee became the 36th state to ratify the 19th Amendment—by the narrowest of margins, a tie-breaking vote in the House—and women’s suffrage was, finally, at hand. Women didn’t wait around wondering what to do next. On Oct. 1, roughly 12,000 women traveled across the Midwest to Marion to meet Harding on his front porch. In its September 2018 newsletter, Friends of the Harding Home reported that the “newly enfranchised women voters, including immigrants, working women, housewives, members of trade unions, and religious, fraternal and social groups, gathered with high school girls and college students at Sen. Warren Harding’s front porch during his presidential campaign. “With the 19th Amendment ratified just six weeks before, the women now were in position to present their plank of policies to Harding. His opponent, Gov. James Cox of Ohio, was next on their list.”

Sherry Hall, the Ohio History Connection’s site manager at

Gathered for news photographers on the steps of the Statehouse, a delegation of suffragists led by Alice Paul met with Ohio governor and presidential candidate James Cox in July 1920 about Tennessee's impending vote on the 19th Amendment.

Marion’s Warren G. Harding Presidential Sites, says securing the right to vote didn’t guarantee equality or respect. “After the election, some folks said women voted for Harding because he had pretty eyes, which I find offensive. Others said that women simply voted as their husbands voted.”

But one thing is certain: 8 million more Americans voted in 1920 than had voted in 1916. And it didn’t matter why women voted for this candidate or that candidate.

“It isn’t necessarily that women’s numbers affected the outcome,” says Ohio History Connection Curator of Manuscripts Karen Robertson, “but once they were able to vote, the issues they cared about had to be considered to court their vote.

“The most commonly discussed example of this is the 1921 Sheppard-Towner Act, which provided federal funding for maternity and child care.” The women who visited Marion on Social Justice Day in 1920 carried signs saying things like “We worked. We waited. We won.” or “We are 2,000 strong for Senator and Mrs. Harding.” The Woman Citizen, a nationally recognized suffrage publication, summed up the day, writing, “One thing was settled by Mr. Harding’s speech to the women on Social Justice Day, and that is that the advent of women in politics has already borne fruit and that the things in which they are most deeply interested will have a new place in the world now that they have votes.” LEARN MORE

Read Karen Robertson’s blog post about Social Justice Day at ohiohistory.org/justice