11 minute read

Regina McLemore: Tribal Journeys

Two Sticks’ fight for survival ends at Deadwood’s gallows

The fact that the Lakota Sioux chief, Cha Nopa Uhah, better known as Two Sticks, lived to reach his 70s was something of a miracle. Born sometime in the 1820s in the Badlands, he experienced the joy of living free on the plains, the despair of fighting for the survival of his tribe, and the deadly consequences of defying the United States government. According to Lakota tradition, he received his name because of his habit of walking with two staves, and he is regarded as a great chief because his vision saved his people.

The story is told that one year the hunters could find nothing to hunt. The Lakota people seemed doomed to starve to death until Two Sticks shared his idea to lead his people northward, through snow and ice, to a place where the buffalo had not been decimated. The people ate well and thrived for a time, thanks to their chief.

But Two Sticks was not always a Peace Chief. Sometimes he donned the garb of the War Chief, as related by author T.D. Griffith in Outlaw Tales of South Dakota. A close friend of Sitting Bull, Two Sticks joined him and Crazy Horse in the slaughter of General Custer and company in 1876. Their victory was short-lived as the

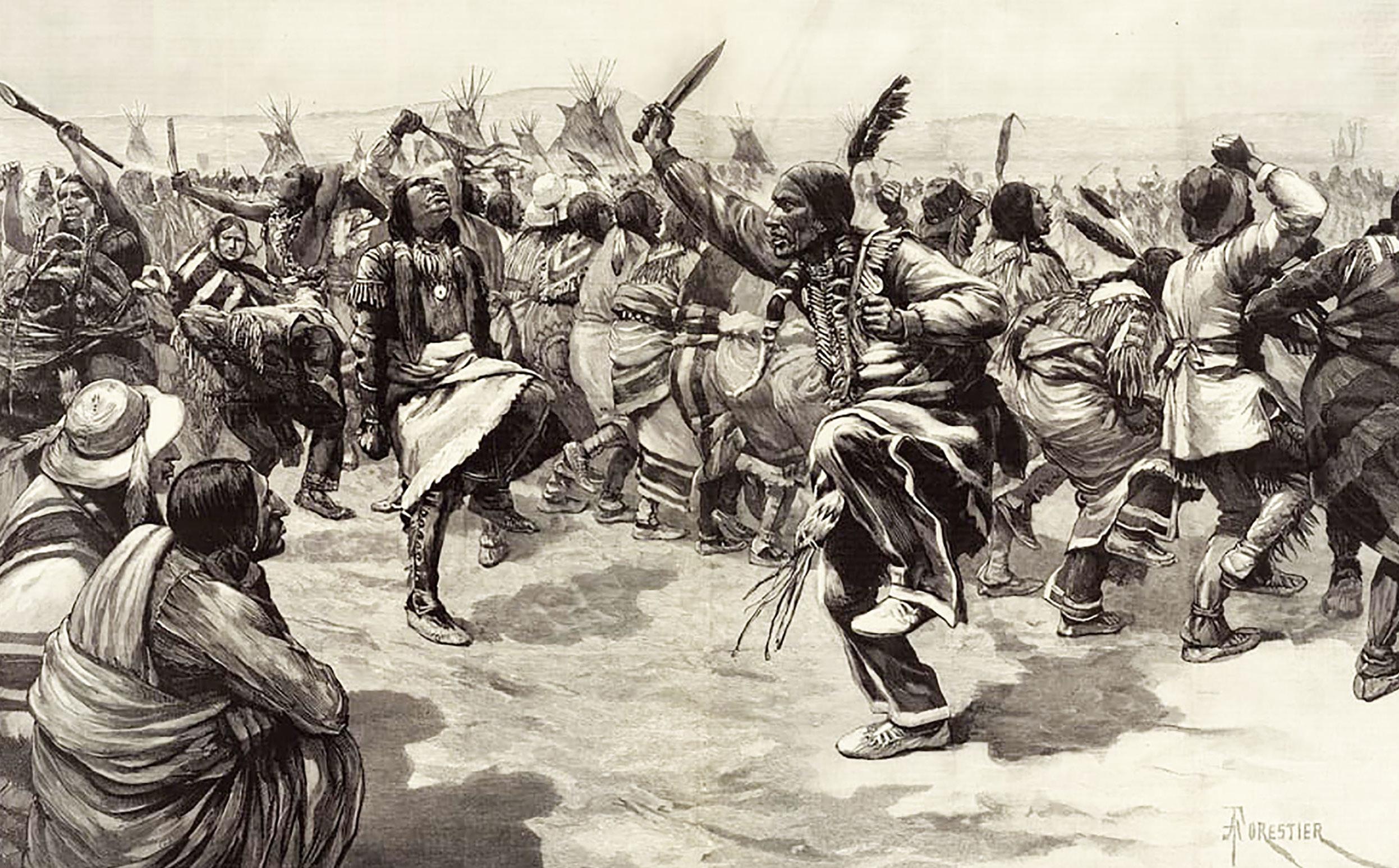

United States retaliated by sending more soldiers to attack Indian villages and forced the Indians to move to reservations. Meanwhile, Native Americans found hope in participating in “Ghost Dances,” in the belief their efforts would bring back the buffalo and their way of life and banish the whites from their lands. Two Sticks was an ardent participant in the Ghost Dance movement.

In an effort to squash what they perceived as a rebellion in December 1890, soldiers shot down hundreds of unarmed Lakota elders, women, children, and warriors at the Wounded Knee Massacre. Two Sticks escaped the tragedy.

He vowed to never go to a reservation, and he and a few companions, including his two sons, First Eagle and Uses a Fight, a nephew, Kills the Two, and three more men, No Waters, Hollow Wood, and Whiteface Horses, roamed throughout South Dakota, stealing cattle and raiding ranches. The Black Hills Daily Times described them as “Uncompapas” in a February 11, 1893 article, a derogatory term that implied they were sneaky. The newspaper went on to say they were “still nomadic and had remained as uncivilized as they were a quarter of a century earlier.”

Earlier in February, Two Sticks and his band targeted the Humphrey Cattle Ranch, located on the White River, a day’s ride from the Pine Ridge Agency. The ranch was especially important to the government, providing meat for the agency. During the same time frame, Two Sticks and his men encountered some Humphrey hands and visitors and killed four of them—R. Royce, John Bennett, sixteen-yearold William Kelly, and thirteen year-old Charles Bacon. Griffith wrote they completed their vengeful acts by shooting thirty cows and three horses.

Different newspapers related different accounts of what happened at the Humphrey Ranch. On January 6, 1895, the Syracuse-Herald Journal claimed that the act of ghost dancing led to the deaths of the four white men. Some reports say Two Sticks and his followers, immediately before the killings, engaged in ghost dancing until they were weak, exhausted, and in a delusional state. They then visited the ranch house and asked if they could stay for a while and warm up. Two other visitors, young William Kelly and Charles Bacon, were present, having asked if they could spend the night. As Two Sticks and his men turned to leave, they opened fire, killing the two ranch hands and the two young visitors.

The February 5, 1893, edition of the Los Angeles Times offered two versions of what happened at the ranch. In one, it was reported that drunken cowboys caused the trouble. A number of these cowboys, who were hands at the Humphrey Ranch, mistreated Two Sticks and drove him away by shooting at him. Later that night, Two Sticks returned with his followers and fired on the cowboy camp, killing three and mortally wounding one.

In the second version, the four men, herders for the ranch, caught Two Sticks and his men killing a steer. They said they were going to report the act to the Indian agent, but the Indians grew angry and threatened them with violence if they did. Several hours later, Two Sticks’ band carried out the threats by killing them in their cabin.

Sometime, during this period of time, word was sent about the raid and the murders to Captain George L. Brown, the Indian agent at Pine Ridge. Brown quickly telegraphed the soldiers at Fort Meade, near present-day Sturgis, and the Eleventh Infantry captain sent six tribal police officers to capture Two Sticks and his followers.

The captain underestimated Two Sticks, and the skirmish ended badly for the police officers. After a short exchange of gunfire, five of the officers were dead, and the sixth was wounded. Two Sticks and his men escaped unharmed.

In retaliation, Brown immediately sent tribal policeman Joe Bush with twenty-five native policemen under his command. They learned that Two Sticks was hiding in the camp of Chief Young Man Afraid of His Horses. While there, he had reportedly said that the killings were the idea of his young followers who said the Great Spirit told them to kill the Whites for exterminating the buffalo and for stealing from the Indians.

Two Sticks and his band refused to surrender to Joe Bush and fired upon him and his men. After the bloody battle was over, First Eagle was mortally wounded, and Two Sticks, Kills the Two, and White Face Horses were seriously wounded. Some of the other Indians present wanted to kill the tribal police, but Young Man Afraid of His Horses stopped them by ordering his followers to surround the tribal officers. He finally convinced all present that harming the officers would lead to all their deaths. Two Sticks and his surviving followers were taken into custody.

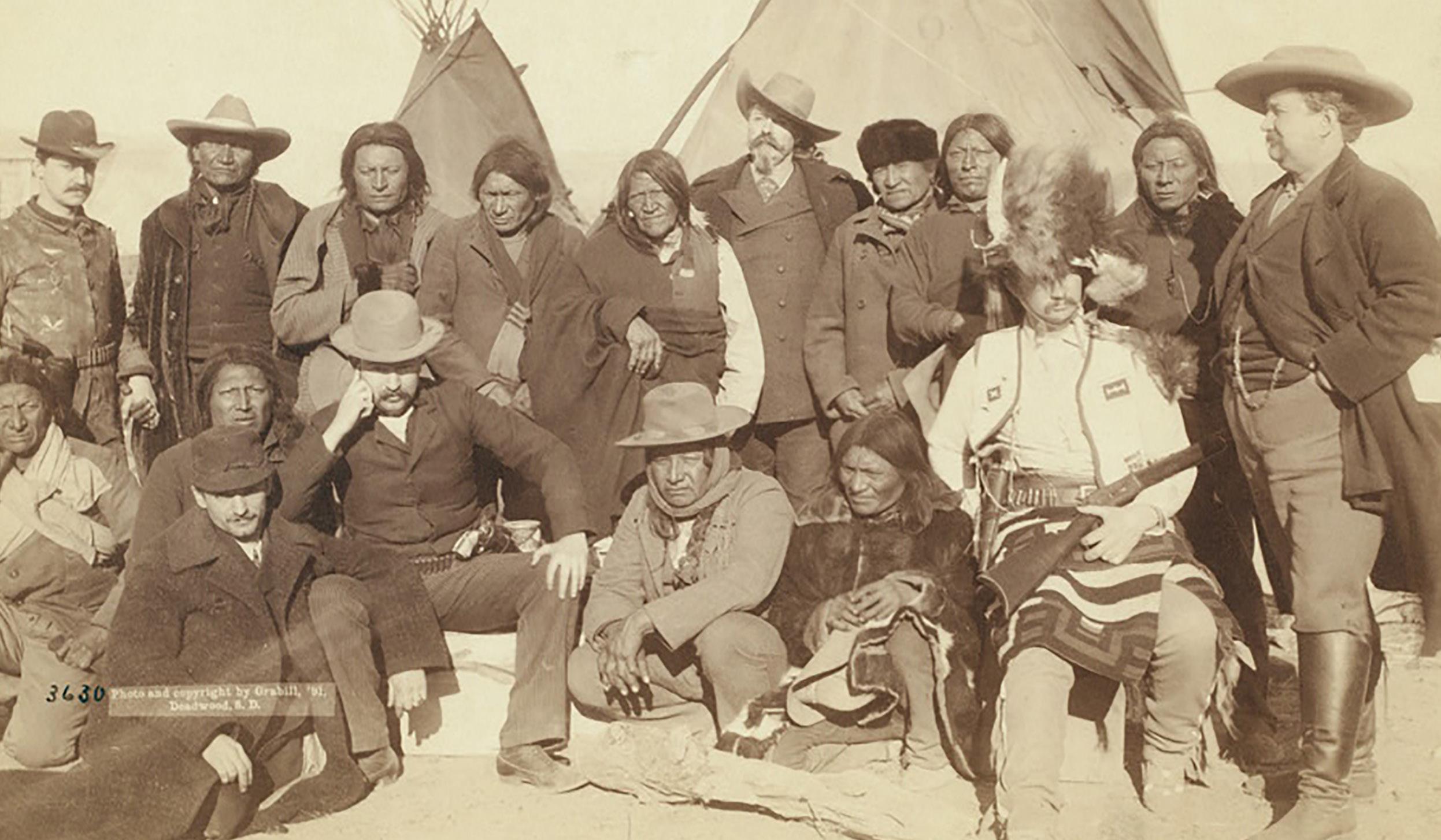

Fearing more violence, Captain Brown invited more than fifty chiefs to Pine Ridge on February 6, 1893, to discuss the situation. At the end of the two-hour meeting, most chiefs agreed that Two Sticks was a troublemaker, and they wanted no part in his rebellion.

Due to the severity of their wounds, reservation officials agreed to hold Two Sticks and White Face Horses until they were well enough to travel to Deadwood for trial. The men refused to allow white doctors to examine them, and their conditions worsened. Whiteface Horses, who was wounded in his lower legs, had one leg amputated but succumbed to gangrene. Two Sticks recovered to face trial.

After standing trial on the charges of instigating and conspiring to commit murder and resisting arrest, Hollow Wood, No Waters, and Kills the Two were sentenced to five years in jail. Hollow Wood and No Waters died in jail, but Kills the Two served out his term.

As the leader, Two Sticks faced a more severe penalty. He was sentenced to death by hanging.

The April 11, 1893, Black Hills Daily Times reported Two Stick’s statement. “My friend and I have not much to say for my part. I had nothing to do with the killing of the white men. My son that was killed by the Indian police was the cause of all of the trouble. I cannot lie, my boy that is dead killed three of the white men and Whiteface Horses killed the other one. My boy (Uses a Fight) that is in jail at Deadwood did not have a gun. He had a bow and arrows. He is only eighteen-years-old and is a coward. My son that is dead had a rifle. Whiteface Horses had a Winchester. The reason we killed them (was) white men did not treat us right. My son said that he wanted to die and be hung.”

Around Christmas in 1894, preparations were made for the execution. Admission tickets had been issued for December 28. The tickets read: “You are invited to attend the legal execution of Cha Nopa Uhah, at Lawrence County Jail, in Deadwood, S.D., December 28, 1894, at 10 o’clock A.M.” The day of the hanging arrived, and by 10:15, two hundred people were crowded into the courtyard where the gallows stood.

That morning Two Sticks had eaten his last meal of grilled steak, bread, and two cups of strong coffee. After he finished, he was told by Father Florentine Digmann and his attorney, W.L. McLaughlin, that President Cleveland had refused to pardon him for his crimes, and only the promise of everlasting life awaited him. When U.S. Marshal Peemiller asked him if there was any reason the sentence should not be carried out, Two Sticks stated his case again. “My heart is not bad. I did not kill the cowboys. The Indian boys killed them. I have killed many Indians, but never killed a white man. I never pulled a gun on a white man… The white men are going to kill me for something I haven’t done… The white men will find out sometime that I am innocent and then they will be sorry they killed me. The Great Father will be sorry too, and he will be ashamed. My people will be ashamed too… My heart knows I am not guilty and I am happy. I am not afraid to die. I was taught that if I raised my hands to God and told a lie that God would kill me that day. I never told a lie in my life.”

Two Sticks grasped the priest’s hands and told him he was a good man. He made similar remarks to his attorney and the marshal.

Next, he sang his death song and reportedly met with his wife, a Chinese woman called China Mary. He told her, “I’m going to die and go to heaven.”

She is said to have replied, “You go to heaven. I’ll go to China.”

Two Sticks grabbed a leather strap from a nearby chair, slipped it around his neck, handed one end to an Indian in an adjacent cell and jerked violently against it. Eventually he calmed down and listened to Digmann’s command to cease his struggles. Claiming he was only trying to die by the hands of his own people, he quietened.

Marshals tied his hands behind his back, and the walk to the gallows began. He was escorted from the jail to the courtyard where the gallows stood.

Two Sticks was led up the steps to the platform. During his last moments at the gallows, he bowed as a clergyman prayed a short prayer and then he raised his head toward heaven and sang his death song once more. Someone placed a noose around his neck and pulled a black hood over his head. In a few minutes, his body was dangling at the end of a long, strong rope. After surviving seventy-one years of hunts, raids, and many historic changes, Chief Two Sticks of the Lakota Sioux left a strange, new world behind.

On December 29, 1894, the Black Hills Daily Times described Two Sticks in a headline as “A Good Indian,” a reference to the callous saying, “The only good Indian is a dead Indian.”

His body was placed in a pine box and buried outside the Mt. Moriah Cemetery in an unmarked grave because Deadwood citizens didn’t allow Indians to be buried in their graveyard.

On January 5, 1885, Deadwood’s Black Hills Weekly Times told how Two Sticks distributed his last possession. He sent his blue cloth leggings and a photograph to his wife and gave the red handkerchief he wore around his head to his attorney, W.L. McLaughlin. He gave his white felt hat to Sheriff Reimer and his pipe to the warden of the jail, Alex Bertrand.

Tim Giago in his article, “The Execution of Lakota Chief Two Sticks”, July 6, 2009, for Native News offers more information. His pipe was later displayed in the Adams Museum in Deadwood until his descendants won their fight to get it returned to his family. On December 9, 1998, the museum repatriated his pipe to his great grandson, Richard Swallow, Sr. and the Oglala Lakota Tribe in compliance with the Native American Graves Protection Act of 1990. They have always believed Two Sticks when he said… “I am not guilty”…, and they believe the United States hanged an innocent man.

Regina McLemore is a Will Rogers Medallion Award-winning author and retired educator of Cherokee heritage. Her great, great grandmother, Susie Christie Clay, survived the Trail of Tears in 1839. Regina’s Young Adult Trilogy, Cherokee Passages, is a fictional retelling of her family’s history from the Trail of Tears down through the modern day.