16 minute read

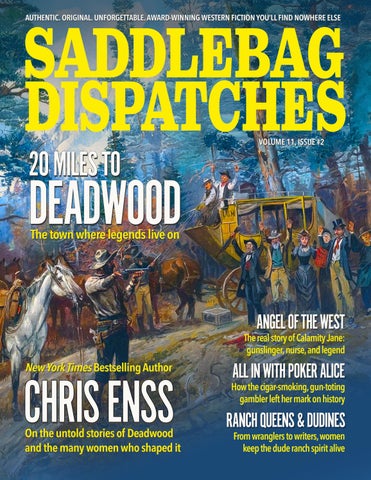

Ranchers, Dudines, Writers, & Riders

In July of 1930, newspapers around the country ran an article titled, “Ranch Bosses Mainly Women.” The unnamed reporter who wrote the story was astonished that 60% of guests at western dude ranches were women. He was even more flabbergasted to learn that 22% of dude ranches were owned by women alone.

This was not a surprise to the many wives and single girls who got up every day and kept a dude ranch going, whether they were an owner, manager, cook, wrangler, housekeeper, or the daughter of the house. The same goes for those who spent glorious vacation hours at ranches from the Rockies to the desert Southwest. For more than 140 years, dude ranches have been places for women to raise a family, run a business, have fun, find careers, and find themselves. And they still are.

Dude ranching began in the early 1880s with the Eaton brothers of Pittsburg, who had a cattle ranch near the town of Medora, North Dakota. Like their fellow ranchers, the Eatons gave food and a bed to men who came to the area to hunt buffalo, elk, and other game. The nearest hotel was in Bismarck, over one hundred miles away. Medora was a popular place and the brothers soon realized that offering free lodging was cutting into their ranching profits. So, they started to charge visitors ten dollars a week to stay at their place and had no trouble finding customers. News about the hospitality at the ranch began to spread, and men of all ages showed up at the Eatons’, including the sons of wealthy easterners who wanted their boys to either dry out or learn manly arts from real cowboys. Pretty soon Medora locals, and reporters, started calling these visitors dudes.

For more than 140 years, dude ranches have been places for women to raise a family, run a business, have fun, find careers, and find themselves.

That word started out as a northern English term meaning clothing, as in duds, but by the early 1880s, a dude was a man who wore too-fancy clothes or wasn’t quite masculine enough for tough times. These men kept taking the train to Eatons’, and by 1899, their spread was called a dude ranch. As more dude ranches opened across the West, dude stopped being an insult and instead became an affectionate term for the guests who flocked to this new buckaroo holiday.

The Eaton brothers were so successful as dude ranchers they moved their operation to Wolf, Wyo- ming in 1903. Just a few years later, they had so many women guests, they put up a ranch house just for them, which they called the “Hen House” or “The Hennery.” It was always occupied.

From the beginning women were the ticket to dude ranching’s success. Those who ran ranches with their husbands were usually called the “dude ranch wife,” but these ladies didn’t stick to a rigid definition. For the most part, men managed the wranglers, the livestock, and kept the barns in good repair. Women were responsible for guest relations, housekeeping and kitchen staff, and public relations. But not always. Frances Allan, of the Allan Ranch in Montana, once said, “The outdoors and the indoors being so closely interwoven, one could not succeed without the success of the other.”

That’s the way one dude ranch owner felt about his wife. Irma Dew was Wyoming-born and working as a librarian in Cody around 1915 when she met New Yorker Larry Larom. He and his friend Winthrop Brooks, of Brooks Brothers clothing fame, had opened the Valley Ranch about forty miles outside of town. Larry and Irma married in 1920, and it didn’t take long for him to realize that he could not run his ranch without her.

In a 1923 letter, he said that Irma put up with “noise, trouble, and worries which the average wife would not stand.” He praised Irma for how hard she worked despite being away from the pleasures and entertainments most wives enjoyed, a life that no eastern woman would be able to manage. Larry and Irma ran the Valley Ranch for over fifty years—they were dude ranch royalty.

Dude ranching also gave unique opportunities to single women. In the early 1900s, Mary Shawver left her native Chicago to take a pack trip with Tex

From the beginning, women were the ticket to dude ranching’s success—as guests, workers, and leaders.

Holm, who ran Cody’s Holm Lodge, a rustic dude ranch. She came back year after year, and then became a business partner with new owner Billy Howell in 1916.

Mary had a big heart and very big opinions. She was a dude ranch wife without a husband, running nearly every aspect of the ranch while Billy took men on multi-week pack trips. She managed the wranglers, who loved her, and when there weren’t any dudes in residence, she went on the trips herself. One winter, Mary was marooned at Holm Lodge after an unexpected snowstorm and survived for three weeks with only the occasional visit of a Yellowstone park ranger who came by to see if she was still alive. She was.

Helen Brooke Herford was raised on a Montana ranch near the Musselshell River north of Billings. The family was well-off and sent Helen to school in Boston and Germany, but her heart was in ranching. After returning from college in 1929, she and her cousin Helen Underwood Wellington opened the Swinging H dude ranch in Stillwater County.

The cousins worked alongside the hands to fix fences, halter-break colts, clean ditches, and lead trail rides and multi-day pack trips. Helen Herford felt that all women should take a dude ranch vacation, and she published stories in newspapers and magazines to lure them to the Swinging H.

In the story titled, “With Only One Woman,” she wrote about taking a group of society girls in her car on a muddy, dangerous road to visit a sheep camp. She loved it when her guests exchanged their stuffy eastern clothes for jeans and flannel shirts, and spent their days riding, visiting nearby dude ranches, fishing, and shooting with both a rifle and a camera. When it was time to go home, her dudines told her they’d had the best time of their lives.

Dudine, by the way, is the feminine form of dude. Ranchers started using the word in the first decade of the twentieth century because so many women were taking dude ranch vacations, and the term stuck. Dudette was in the running for a while, but it didn’t make the cut.

Another single dude ranch owner was Dr. Caroline McGill. She was an exhausted physician who needed a break after working at a hospital in Butte, and she spent her time off at the Buffalo Horn Creek Resort in Montana’s Gallatin Canyon starting in 1911. It became her get-away place whenever she needed a rest, and in 1936 she bought the ranch and a neighboring parcel. The two properties added up to 320 acres, so she renamed it the 320 Ranch.

When the Dude Ranchers’ Association was formed in Bozeman in 1926, all but one of the officers were men. The lone woman on the board of directors was Lillian Shaw. She and her husband Walter ran Shaw’s Camp in Montana, but when Walter died suddenly in 1925, Lillian stepped in and took over the entire operation. Other DRA directors had wives who shouldered half of their burdens, including Montanans Helen Van Cleve at the Lazy K Bar, Dora Randall at the O.T.O., Senia Croonquist at Camp Senia, Pearl Binko at Binko’s, Grace Miller from the Elkhorn Ranch, and Irma Larom from Valley Ranch in Wyoming.

Dude ranches hosted men exclusively in the 1880s, but in the early years of the twentieth century, women began to head out West, either with their husbands or on their own. Some of them were actually on the hunt for their men, like Evelyn Raue. In June of 1907, she left her husband in Philadelphia and took the train to Aldrich Lodge, a cattle operation on the Shoshone River near Cody which sometimes took in a few dudes. She was looking for her lover, G. Gordon Massey, the rich son of a railroad tycoon. He went out to Wyoming, or had possibly been sent there to stop drinking, leaving behind his wife and three children.

Instead of getting sober, Massey found others to drink with, which Evelyn heard about back in Philadelphia and which is why she tracked him down. Her arrival didn’t change his habits though, and when the owner of the ranch got rid of his liquor, Massey ran off to Cody. Evelyn jumped on a horse and rode to town, managing to get him into a carriage and back to the ranch. He apparently improved after ten days at Aldrich Lodge. His wife filed for divorce.

For some women, dude ranches were places of refuge. One was writer Mary Roberts Rinehart. She’s not very well known today, but in the early twentieth century she was a celebrated journalist and novelist. In 1915, she was resting at home in Pittsburgh after covering the carnage of World War I in Europe. That summer, Howard Eaton, the founder of Eatons’ dude ranch, asked her to join a pack trip he was organizing to go into newly-opened Glacier National Park. Artist Charles M. Russell had also signed up, and Mary agreed to go. Celebrities always brought in more business. Everyone spent a couple of days at Eatons’ before heading out and Mary fell in love with dude ranch life.

She started writing magazine articles about dude ranching, encouraging women to give them a try. In a 1927 essay titled, “Women on a Dude Ranch,” she said, “More women of all ages visit dude ranches than men. And they adapt themselves to the life more easily. They show more enthusiasm and possibly gain more benefits.”

Benefits is the right word. For many dudines, especially those who visited the West for the first time, a dude ranch offered freedom from stifling social rules, exhilaration, and experiences they would never have at home.

A Wyoming dude ranch gave young Peggy Thayer the opportunity to exhibit her wild side. Born into wealthy Philadelphia society in 1898, her father was the vice president of the Pennsylvania Railroad. In 1912, Peggy’s parents and her oldest brother Jack went on a visit to Europe, and on April 10 they boarded their ship for home: the RMS Titanic. Peggy’s mother and her brother survived the sinking, but her father did not.

From that day, she lived as if her time on earth would end just as quickly. Peggy was a fearless horsewoman, and she spent two seasons at the JY dude ranch near Jackson Hole. In 1922, she entered a local rodeo and won a horse race on a recently broken bronco that tried to buck her off before the race even started, impressing the local cowboys and scandalizing her family.

Even famed aviator Amelia Earhart found peace away from her fans at a dude ranch. In the summer of 1934, she and her husband visited the Double Dee ranch near Meeteetse, Wyoming. She loved the place and allowed local photographer Charles Belden to take photos of her having fun in her casual western clothes. She asked ranch owner Carl Dunrud to build her a cabin on the property but she vanished from the sky in 1937 and never got back to see it.

Ranch owners saw dudines fall in love with their wranglers so frequently it was practically a tradition. And when an eastern girl ended up marrying one of the ranch’s cowboys, the story made the papers. In 1931, Arizona rodeo cowboy Lawton Champie, who managed a small dude ranch in Castle Hot Springs, married Boston society girl Annie Crocker. The Boston Globe newspaper had this to say about it: “Fitchburg Heiress to Wed Broncho Buster.”

The marriage soon fell apart, which would not have been a surprise to Mary Shawver. In her memoir, Sincerely, Mary S., she wrote about girls who wanted to have a permanent vacation with their personal wrangler, and how it never worked out. One guest had a theory about why this happened— the dudines fell in love with their horses, and since they couldn’t marry a horse, they married the man who smelled like one.

Hollywood took up the topic in the classic 1939 film The Women . During this era, women could take the train for Reno, stay there for six weeks, and get a quickie divorce. Many dude ranches changed their business model to accept dudine divorcées, and this formed part of the plot of the movie. The Countess de Lave, after spending her allotted time at the Double Bar T ranch, married wrangler Buck Winston and took him back to New York. That union didn’t last, either.

One woman took the dude ranch to a whole new place. Her name was Sally Rand. She was a famous burlesque dancer, and in 1936, she debuted a new show at the Fort Worth Frontier Centennial with the intriguing name of “Sally Rand’s Nude Ranch.” It had its own building at the fair and featured a large sign in the front which, at first glance, looked like it said “Sally Rand’s Dude Ranch.” Upon closer inspection, visitors could see that the “D” was crossed out and replaced with an “N.” It cost twenty-five cents to get in, and once past the front door, viewers saw a fake western landscape filled with semi-nude girls wearing

“More women of all ages visit dude ranches than men—and they adapt to the life more easily.” —Mary Roberts Rinehart, 1927 cowboy hats, holsters, and cowboy boots. They twirled lariats, sat on the fence, played badminton, and generally just frolicked. In 1939, Sally brought her Nude Ranch to the Golden Gate International Exposition in San Francisco, where it got a bigger building and an even bigger audience. Sally later married champion bronc rider Turk Greenough.

During World War II, dude ranchers had to contend with rationed foods, wranglers who enlisted and left the ranch, and cooks who departed because they could get better pay in wartime factory jobs. Sometimes, the owner himself went to war, leaving his wife to manage the business, the guests, their children, and the fill-in wranglers. But dude ranchers are resilient, and the women triumphed by keeping in touch with each other, mostly through the “House Management Department” column in The Dude Rancher, the magazine of the Dude Ranchers’ Association. They shared recipes, advice, and horror stories.

Many dude ranch guests rolled up their sleeves and helped with chores during their stays, whether it was cleaning their own cabins or helping bring in the horses every morning. The staffing problems at dude ranches prompted some girls to write to the Dude Ranchers’ Association, offering to help out and help the war effort.

One nineteen-year-old girl from Indiana wrote, “I can ride horses and milk cows. So can my sister and brother who are eager to work on a ranch this summer. We realize the work is hard, but we feel it is our duty to help in any way we can.”

Young women were already doing this work of course, because they were dude ranch kids. Patsy Whited’s family ran the Lazy F dude ranch in Ellensburg, Washington in the late 1940s. She was the top wrangler, and she also waited tables, cooked, took care of the livestock and, in her off hours, attended college. The Dude Rancher magazine ran a profile of Patsy in a 1946 issue and encouraged young women to apply for work on dude ranches. But everyone knew that wives and daughters had been doing very non-traditional work around the ranch for decades. They were just quiet about it.

Today, more women than men are working as wranglers on dude ranches. Young women who grew up taking riding lessons and then entered equestrian programs in colleges are spending their summers working at dude ranches, sharing their expertise and love of horses with dudes and dudines.

Female wranglers were unusual enough in the postwar years that they were profiled in local papers. Norine Scruggs, a Chicago native, managed the corrals and cowhands at a resort-like dude ranch in Las Vegas called the Hotel Last Frontier. “Cowboys in southern Nevada are shaking their heads in disbelief,” said one reporter for a Utah newspaper.

As the 1970s got underway, more women began moving into wrangler jobs on dude ranches. Women dude ranchers were consulted for their expertise beyond the ranch too. In 1975, Dorothy Vale Kissinger, co-owner and manager of the Sahuaro Lake Guest Ranch in Arizona, was named to President Gerald Ford’s Commission on the Observance of International Women’s Year.

Today, more women than men are working as wranglers on dude ranches. Young women who grew up taking riding lessons and then entered equestrian programs in colleges are spending their summers working at dude ranches, sharing their expertise and love of horses with dudes and dudines. Guests go home with memories that can’t be made elsewhere, and many girls want to spend more time on horseback after their time on the ranch.

Women have found their way to dude ranches for over a century, and for myriad reasons. Some show up to ranches as guests, so they can live out their cowgirl fantasies. Others take jobs so they can ride a horse in their off-hours. And others run the ranches, because they want to share their places not only with people who want to stay, but those who need to.

Best-selling author Gene Kilgore has been writing about dude ranching for over forty years. He knows first-hand what women have done, and continue to do, for this unique American industry.

“Women,” he says, “are the glue.”

Lynn Downey is an award-winning historian, novelist, and short story writer. She has written two books about Wickenburg, Arizona: Wickenburg: Images of America, and Arizona’s Vulture Mine and Vulture City, finalist in Arizona History for the New-Mexico Arizona Book Award. Her other passion is the dude ranch, and her Journal of Arizona History article, “A House-Party on An Old Frontier Ranch: How Arizona Became the Dude Ranch Capital of the World,” was a finalist for the Spur Award in 2024. Downey’s latest book is American Dude Ranch: A Touch of the Cowboy and the Thrill of the West. Her debut novel, Dudes Rush In, set on an Arizona dude ranch, won the New Mexico-Arizona Book Award for Historical Fiction. Downey is the Past President of Women Writing the West and serves on the board of the Dude Ranch Foundation.