13 minute read

Deadly Secrets of Winn Parish

Masked as churchgoers and civic leaders, the West-Kimbrel Gang ran one of the bloodiest outlaw operations in American history—and buried their victims in hidden wells.

Story by Anthony Wood

Part One of a Two-Part Series (Continued in December, 2025)

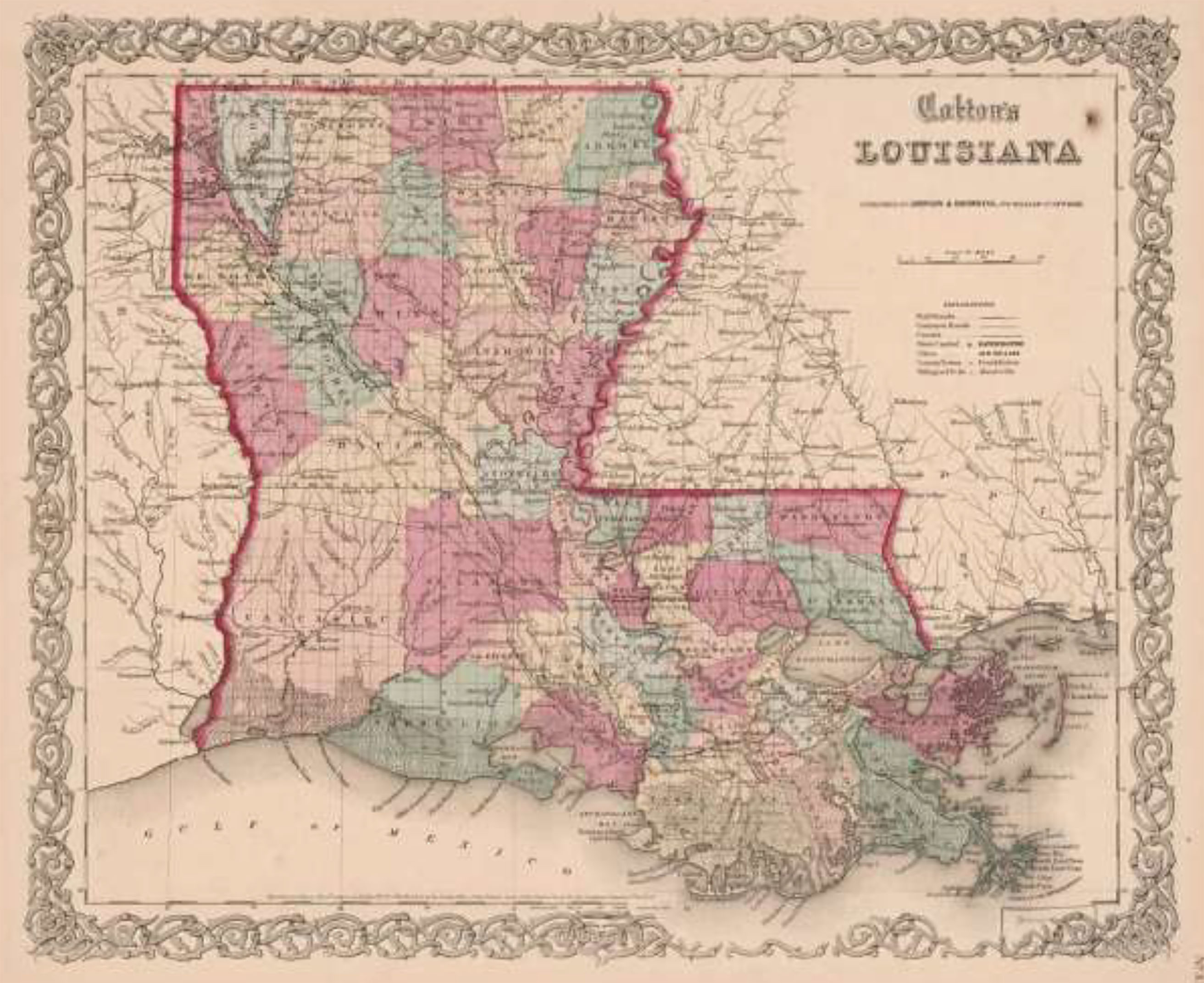

In the rolling hills of central Louisiana, a little known band of outlaws operated one of the most efficient and bloodthirsty organized crime operations of its day. Their fierce and remorseless exploits of murder and theft along a well-traveled corridor between Mississippi and Texas make the James-Younger Gang look like amateurs. These Nightriders were none other than the West-Kimbrel Gang of Winn Parish, Louisiana.

Most know the Natchez Trace to be a former Indian trail turned super highway extending from Natchez to Nashville. Heavily travelled by post riders, flatboatmen, land speculators, businessmen, and innocent settlers, the Natchez Trace was plagued by such outlaws as Samuel Mason, the Harpes, and John Murrell. Though the Natchez Trace east of the Mississippi River fell into disrepair by the 1830s, this was not true across the Mississippi River in Louisiana.

The Natchez Trace extended across the Mississippi River by ferry to Vidalia, Louisiana, where it joined the Harrisonburg Road and continued on as the El Camino Road to Nacogdoches, Texas, then finally ending in Mexico. It was along the Harrisonburg Road in the Red River Valley Neutral Strip, running through Grant and Winn Parishes, that the West-Kimbrel Gang plied their trade. The Strip possessed a reputation for lawlessness so prevalent that during, and immediately following, the Civil War, Federal troops refused to occupy the area.

These ruthless outlaw men and women, viewed as model citizens in Atlanta, Louisiana, went about their criminality without ever being seriously challenged by the law or the locals until the spring of 1870, when the West-Kimbrel Gang met its end.

The Kimbrel Clan Seeds of the West-Kimbrel Gang’s outlawry began before the Civil War with “Uncle Dan” and “Aunt Polly” Kimbrel inviting businessmen, travelers, and settlers moving west into their home for a meal and a night’s rest. This was misleading. By day, Uncle Dan and Aunt Polly enjoyed a good reputation for fine service, but by night, they murdered emigrants and robbed them of their earthly possessions.

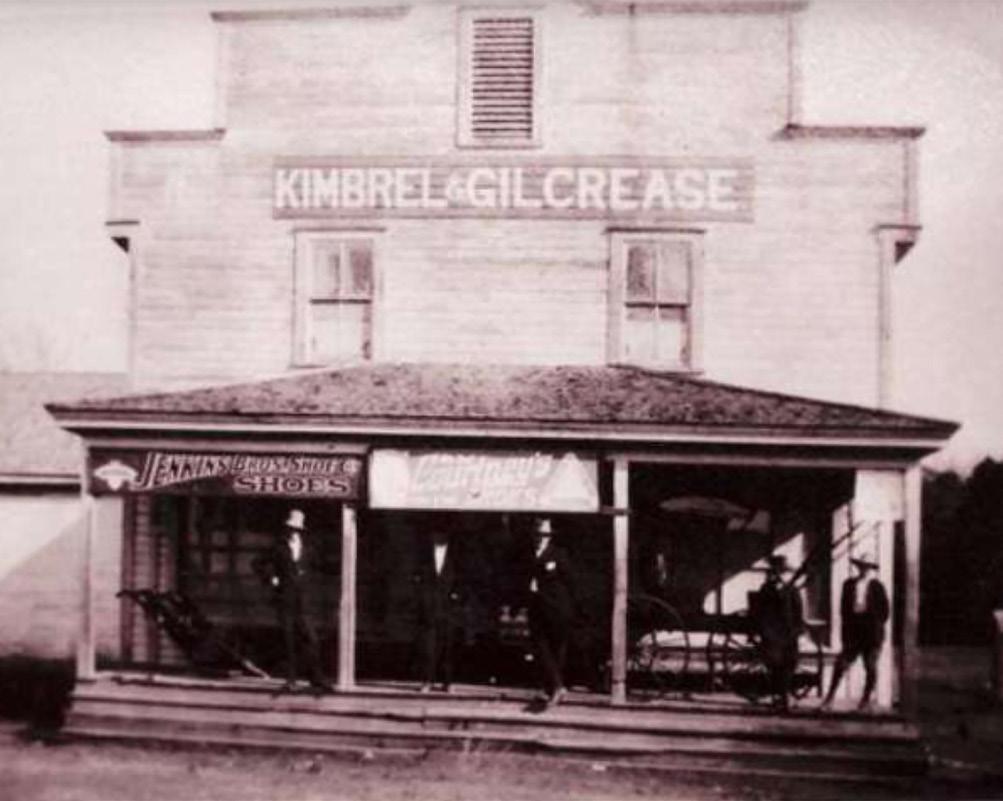

Dilson “Uncle Dan” Kimbrel, a large man of “Germanic” appearance, married Mary L. “Polly” Williams in 1833, just one month shy of her fifteenth birthday. After a short jaunt in Mississippi, the Kimbrel family moved to Louisiana around 1850 and settled in Winn Parish along the Harrisonburg Road. Operating a store, saloon, and post office in Wheeling on the Harrisonburg Road, just two miles from their farm, the Kimbrel’s were considered fine, upstanding family folk who went to church and raised six children.

Having ridden with such outlaws as the Copelands and John “Reverend Devil” Murrell in Mississippi,

Uncle Dan was known to be “as cautious as a pawnbroker and as foxy as an itinerant peddler.” After he killed “Reverend Devil” for hacking off a horse-trader’s son’s fingers and toes, Uncle Dan moved his family to Louisiana where they directed their villainous crimes so cleverly and quietly that most of his closest neighbors had little clue to the murderous thievery happening right under their noses.

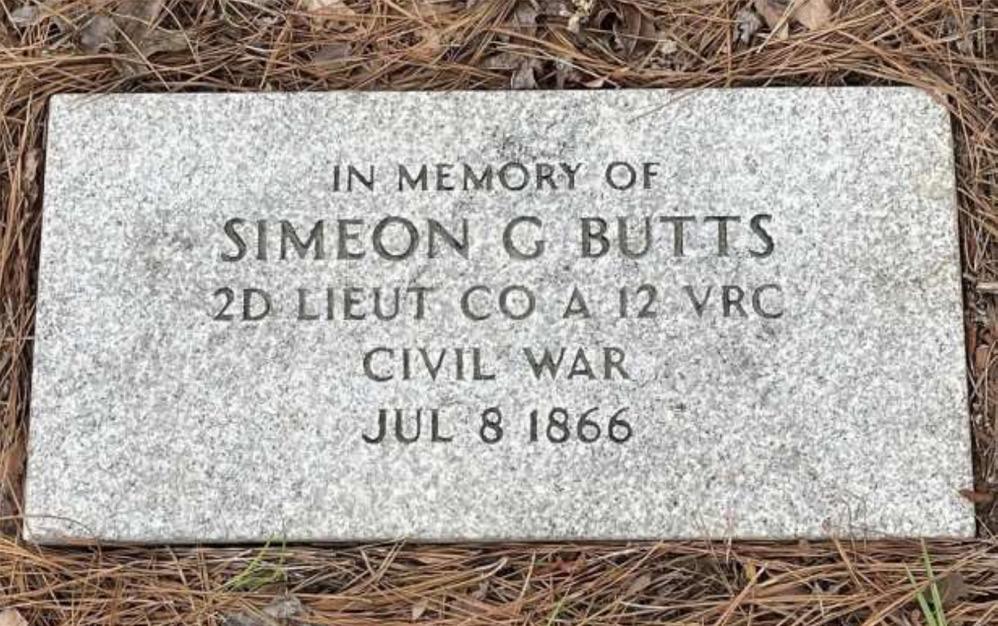

When their son, Lawson, nicknamed “Laws,” returned home after fighting with the Confederacy, he organized a band of former soldiers bent on furthering his parents’ criminal activities. Their devilment reached a new level when gang members robbed and murdered a Federal paymaster, Lieutenant Simeon G. Butts, near the Saline Mills in July, 1866.

Described as “a handsome and jovial young man,” Butts was carrying $2700 from Natchitoches to his post at the Freedmen’s Bureau in Vernon, Louisiana.

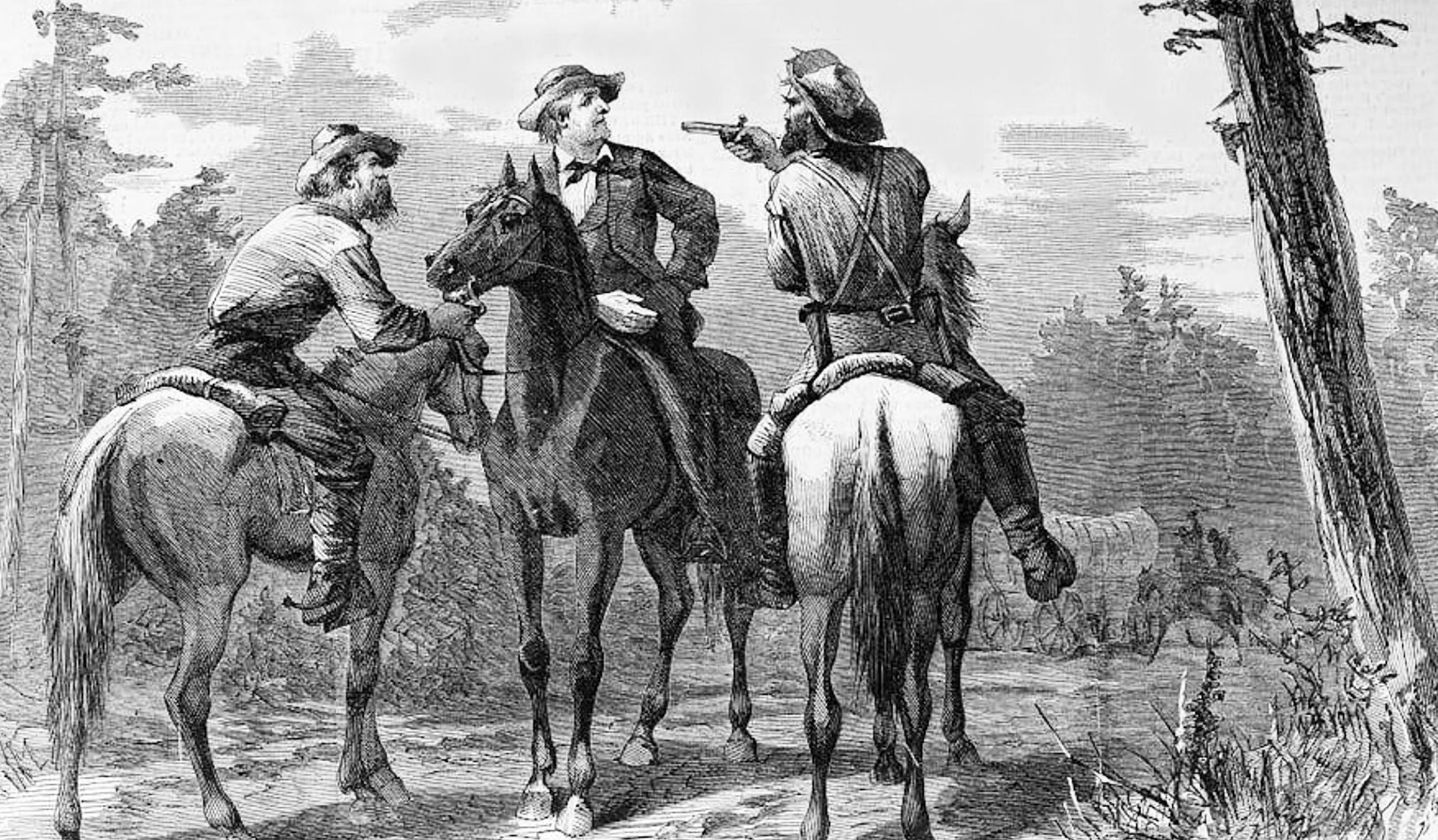

Recorded not long after the gang’s execution in the May 28, 1870 edition of The Ouachita Telegraph, three gang members overtook Butts, claiming to be searching for lost cattle. They stopped at a spring for water, and as Butts drank, a new member of the gang, John West, “deliberately shot the unsuspecting man through the head” with his Colt revolver. The outlaws stripped the body of any evidence, but a farmer found Butt’s remains and they were identified two months later. Being considered a Union soldier in an area unfriendly to the North, the place of Butts’ death became known as “Yankee Springs.”

Widow of an ex-Confederate soldier, Emiline “Aunt Em” Mitchell, who farmed next to the Kimbrel family overheard the Nightriders recounting Butts’ fate. Aunt Em offered her detailed findings by letter directly to the U.S. War Department in Washington which included names, dates, and places. She fingered the Kimbrels as being responsible for Butts’ death. Despite her efforts, and due to unfriendly sentiments of local ex-Confederate soldiers, the Federal Army refused to do anything about the atrocities being committed in Winn Parish. Lieutenant Butts’ murder marked the moment John West began to lead the Nightriders, who would go on to become the West-Kimbrel Gang.

The dollar value of the gang’s robberies would astound even the craftiest thief today. The Nightriders robbed two adventurers who had stolen $85,000 in gold ingots from a Mexican mine. Investigations made the gold useless to West and the gang because anyone caught with even the smallest portion of the treasure would have immediately incriminated themselves. The gold, worth millions in today’s dollars, has yet to be reported as found.

In another instance, a northern timber and land buyer who didn’t trust banks came to Winn Parish with $8600 in cleverly hidden gold coins. He sewed each twenty dollar gold piece into a two-inch square in a homemade quilt. A local, Frank Straughn, in whose home the traveler had made his headquarters, informed the buyer he’d spoken too loosely about the money he carried. Straughn warned that the man’s life wasn’t worth one sewed-on check in his quilt blanket, saying, “The buzzards are flying over.”

Straughn escorted the timberman fifty miles, but he had made it no more than a few miles toward home than the northern buyer had already been robbed and killed. The Nightriders had followed the two from the start. John West shot the timberman off his horse and took the horse and the gold in the blanket with no one the wiser.

Who was John West?

Elbert Weston, born in 1830, in Massachusetts, traveled to Texas with his family as a child. After abandoning his wife and child in Texas, he moved to Winn Parish, Louisiana in 1853 and changed his name to John West. Settling near Atlanta, he married Sarah Pennywell with whom he had three children. West eventually became a wealthy landowner and influential community citizen. Fair-skinned, five feet ten inches tall, and weighing around 175 pounds, West possessed the manners needed to win people over with a soft-spoken tone and a smile.

Enlisting as a Private in the 27th Louisiana Volunteer Infantry Co. K, John West was later transferred to Co. F. The author’s great-great uncle, Columbus “Lummy” Nathan Tullos, served alongside West in Co. F during the Siege of Vicksburg, Mississippi, through to its surrender and parole. West rejoined and later was captured in New Orleans and later paroled.

After the war, West rejoined his wife in Winn Parish and built a log cabin overlooking Hill Bayou five miles south of Atlanta on the Harrisonburg Road. Like many ex-Confederate soldiers, he found home to be desolate and destitute. Hatred of carpetbag rule, crippling poverty, and the presence of Yankee soldiers drove angry ex-soldiers like West to attack Yankee payroll carriers and wagon trains loaded with supplies. West found, in the Kimbrel clan, his answer for the men and tactics needed to successfully seize Yankee property. He organized a quick-moving band of marauders called Nightriders.

John West’s popularity and influence in the community grew to include his being elected Justice of the Peace of Ward Six in Winn Parish. A welcome guest in local citizen’s homes, he soon joined the First Methodist Church in Atlanta where he served as a deacon, choir leader, superintendent of Sunday school, and adult Bible class teacher. A skilled carpenter and mill- wright, West built and operated his own sawmill, and later acquired two cotton gins and a gristmill located along the Harrisonburg Road. By day, West was an influential Winn Parish leader but by night a ruthless murdering thief who led the Nightriders to become the most successful criminals in Louisiana history.

Organized Crime at Its Best... Or Worst

Between the years 1866 and 1870, the West-Kimbrel Gang wreaked havoc on those journeying west on the Harrisonburg Road. John West developed a system of passwords, signs, Chickasaw Indian tree markings, and horn bugle calls the Nightriders used to communicate their ghastly intentions. The gang could translate information about settlers, businessmen, and travelers quickly and efficiently for miles. When West blew designated bugle calls with a hunting horn, much like those used in the military, the men assembled at West’s home or other meeting spots, such as the Kimbrel’s store and saloon in Wheeling or a farm nearby. Markings notched in trees designated paths to meeting places and hideouts used by the gang.

The Nightriders knew the meaning of each call and responded swiftly. West used passwords when out on a night of banditry, such as, “The clover is blooming,” to which a Nightrider must reply, “Spring is here.” If the password, known only to the Nightriders, was not quickly given in reply, West and his men moved in for the kill.

With the Homestead Act of 1862 offering free land for a small fee with the promise to live and make improvements on a 160-acre-allotment, settlers flooded the road leading directly through the corridor used by the West-Kimbrel Gang. The number of emigrants increased exponentially when the Civil War ended which often led to thousands of wagons waiting in lines up to three miles long at the Red River ferry. This made for easy pickings for men bent on thievery and murder. So much so, they had to devise a system of disposal of both stolen goods and bodies.

When worthwhile prospects appeared on the Harrisonburg Road, West gathered the Nightriders to formulate a plan. If a lone rider, West often would waylay the traveler himself, dispose of the body, and escape with the stolen goods. If two or more people traveled together, West took a couple of men along to make quick work of the unsuspecting victims. When a wagon train approached, West summoned a number of Nightriders using his hunting horn and attacked without mercy. When caught in West’s trap, families, especially with a company of women and children, were whisked away to the Kimbrel farm. Aunt Polly Kimbrel murdered the defenseless women and children and the Nightriders killed the men. The bodies were then thrown into a nearby well.

West organized a system of what we term today as “chop shops” in a series of blacksmith establishments either owned or controlled by the gang. Meticulous in their work of dismantling and reconstituting wagons and gear by repainting, repairing, switching parts, and camouflaging stolen wagons and carts in these shops, they also outfitted a horse ranch east of the Kimbrel’s store in Wheeling to conceal stolen teams and riding stock until such time as the animals could be driven west and sold in Texas. The Nightriders refitted the stolen property so efficiently that fences could dispose of the goods, wagons, and livestock safely, quickly, and profitably.

Although the gang’s operations ran like a well-oiled machine, their exploits eventually forced them to deal with the continuous need to dispose of murder victims. As Jack Peebles in The Legend of the Nightriders wrote, “The nightriders committed so many murders… disposal of the bodies became a problem. Corpses could not be left in the open to decay because their skeletons would attract attention.”

With neither scattered shallow graves, nor the Kimbrel family cemetery, able to accommodate the growing number of murdered victims, a new plan for body disposal had to be devised. Having exhausted all possibilities, the Nightriders dug a number of wells on gang member’s farms along the Harrisonburg Road, allowing the gang to increase their hideous crimes and hide victims day or night. No record of the location of these wells was kept for obvious reasons, but in a well found in Uncle Dan’s pasture after the gang’s demise, forty skeletons were discovered. Most of these wells were never found and the victims remain where they lay to this day.

One special pit, “the prison well,” was dug not far from one of West’s cotton gins. John West forced former slave, Pad “Uncle Pad” Pennywell, to watch over this well designed to hold prisoners until tortured for information or their further usefulness determined. Uncle Pad soon realized that having witnessed many murders and other acts of outlawry, he was doomed to never go free. Developing a passive loyalty to West and the gang, Uncle Pad did whatever was required of him and lived on whatever West would give him for his work. It wasn’t until the West-Kimbrel Gang was destroyed that Uncle Pad was free to live without the fear of danger. He later became a respected citizen in Winn Parish, married, and is buried in the Corinth Cemetery.

It’s been said that the West-Kimbrel Gang was responsible for the murder and disposal of hundreds, maybe even thousands of victims during those few short years. But that’s not the worst of the horrendous atrocities committed by the Nightriders. The “worst of the worst” is yet to be told.

Arkansas Writers Hall of Fame author, Anthony Wood has won a number of awards for his work which include a Will Rogers Medallion Award in 2021 for his short story, “Not So Long in the Tooth.” Anthony serves as Managing Editor for Saddlebag Dispatches, President of White County Creative Writers, and is a member of Turner’s Battery living history group. In River Storm, the eighth action-packed volume in his historical fiction series, A Tale of Two Colors, Anthony tells the tale of the demise of the West-Kimbrel Gang. Anthony enjoys researching ancestors, roaming historical sites, camping and kayaking along the Mississippi River, and spending time with family. He and his wife, Lisa, live in Conway, Arkansas.