11 minute read

Calamity Jane: Angel of the Wild West

Though remembered as a pistol-wielding outlaw, Calamity Jane built another legacy—fearless caregiver, tireless nurse, and protector of the sick when no one else would answer the call.

Story by Billie Holladay Skelley, RN, MS

When Martha Jane Canary first rode into Deadwood, South Dakota in 1876, she was already known by her sobriquet, “Calamity Jane.” Her sharp-shooting, cross-dressing, alcohol-swilling, cigar-smoking, tobacco-chewing, and profanity-laced tirades had already earned her a reputation as a hard-living hellraiser. One newspaper noted that she had a penchant for cracking “all the bottles in a saloon with well-aimed bullets.” Known for being a persistent gambler, occasional prostitute, and devoted wanderer, Jane engaged in numerous drunken binges and spent much of her time consorting with miners, soldiers, and railroad workers. Within her colorful and self-indulgent lifestyle, it is often difficult to sift the fiction from the facts—especially since she often promoted much of the fiction as fact herself—but there is evidence she had somewhat of a dual personality. Her wild, wayward, and wanton lifestyle was counterbalanced by a tenderhearted and sensitive side that manifested itself in unselfish and considerate traits. Calamity Jane, the hell-raising frontierswoman, was also a compassionate and caring nurse to the ill, injured, and needy.

Born near Princeton, Missouri in 1856 (some sources indicate 1852), Jane’s family decided to move westward, likely to follow the gold rush boom. During the trip, Jane learned to ride a horse and shoot a gun—and she proved adept at both. Orphaned at a young age and possessing little formal education, she had to make her way in the rough, male-dominated West. To do this, Jane disregarded many of the conventional norms for proper female behavior and dressed frequently as a man to earn a man’s wage. Over the years, she took on numerous jobs, including being a bullwhacker, wagon driver, cook, maid, waitress, dishwasher, laundress, and dance hall girl, but despite these employments, she often remained destitute and penniless. Over time, Jane developed an amazing talent for telling tall tales, and her drinking increasingly became a problem. She was jailed on numerous occasions for intoxication and disorderly conduct, but, as Black Hills pioneer John S. McClintock noted, her “kind and sympathetic nature” continued to be revealed during “her tender ministrations to the suffering.”

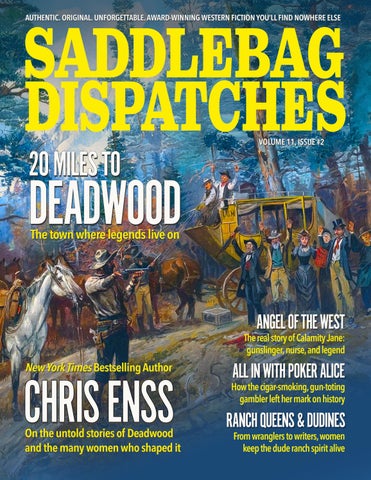

Martha “Calamity Jane” Burke Canary, better known as Calamity Jane, sports an elaborate western outfit on horseback in front of tipis and tents. One of the rowdiest and adventurous women in the Old West, this photo captures the mythical nature of her frontier persona just two years before her death in 1903. Photo by C.D. Arnold, ca. 1901.

At a young age, and likely out of necessity, Jane became skillful in treating common illnesses, removing arrows, and bandaging gunshot wounds. Although she had no formal nursing training, several early books, memoirs, and newspapers document her serving in various nursing capacities. They also note how she always seemed willing to help anyone in need.

Both Richard Dunlop in Doctors of the American Frontier (1965) and Robert Karolevitz in Doctors of the Old West (1967), reference Jane nursing patients at Fort Laramie in the 1870s. She assisted military surgeon Dr. Valentine McGillycuddy by helping with the ill and injured, and she “stayed up nights caring for the sick.” Dr. McGillycuddy recognized Jane’s nursing talents and noted that although she could be “loud and rough,” she was “kind-hearted” and “always ready to help or nurse a sick soldier or miner.”

James McLaird notes in Calamity Jane: The Woman and the Legend (2005) that in the fall of 1876, Jane reportedly nursed a miner named Jack McCarthy, who lived alone in an isolated cabin between Central City and Lead, South Dakota. McCarthy had broken his leg and was unable to care for himself, so Jane raised money, purchased supplies, and engaged a packer at Deadwood. She arrived at McCarthy’s cabin around Thanksgiving time and cared for him there until he recovered.

Several accounts indicate Jane nursed the sick during typhoid eruptions and during black diphtheria outbreaks. Jesse Brown and A. M. Willard describe in The Black Hills Trails (1924) how Jane nursed a family in Pierre afflicted with black diphtheria. She purchased food and medicine for the family and nursed them till the illness had passed.

Roberta Sollid also describes in Calamity Jane: A Study in Historical Criticism (1951) how the pioneer

Robinson family of Deadwood had six children who fell ill with black diphtheria. Jane went into their home and took charge of caring for the children.

Sollid also describes a pioneer in the Fort Pierre area, Charles Fales, who recalled how Calamity Jane nursed one of his relatives who was ill with mountain fever. Since this relative was a prim and proper lady, Jane was asked to cease smoking, swearing, and drinking—and wear a dress. She abided by these stringent conditions for weeks until the woman improved, but once she recovered, Jane headed immediately to the nearest saloon to drink.

In 1878, the Black Hills Daily Times reported that a man named Warren had been stabbed on Main Street, but he was “doing quite well under the care of Calamity Jane, who has kindly undertaken the job of nursing him.” This article went on to note that “there’s lots of humanity in Calamity, and she is deserving of much praise for the part she has taken in this particular case.”

Jane’s most famous nursing efforts occurred during the smallpox epidemic that struck Deadwood in 1878. Referred to as the “dreaded scourge” and “speckled monster,” smallpox was an extremely contagious disease with a high mortality. Those who survived the illness were often left with permanent, disfiguring scars. At the time, afflicted patients were isolated in grimy tents and crude cabins, known as pest houses, in an attempt to prevent further spread of the dreaded disease. Robert Karolevitz notes that Jane cared for these patients “when no one else would go near them.” Lewis Crawford also describes in Rekindling Camp Fires (1926) that, during this epidemic, Jane “ministered day and night among the sick and dying, with no thought of reward or of what the consequences might be to herself.” Even Stewart Holbrook, who refutes many of the tall tales surrounding Calamity Jane, gives her credit in Little Annie Oakley and Other Rugged People (1948) for working “night and day ministering to the ill and dying” during the Deadwood smallpox epidemic.

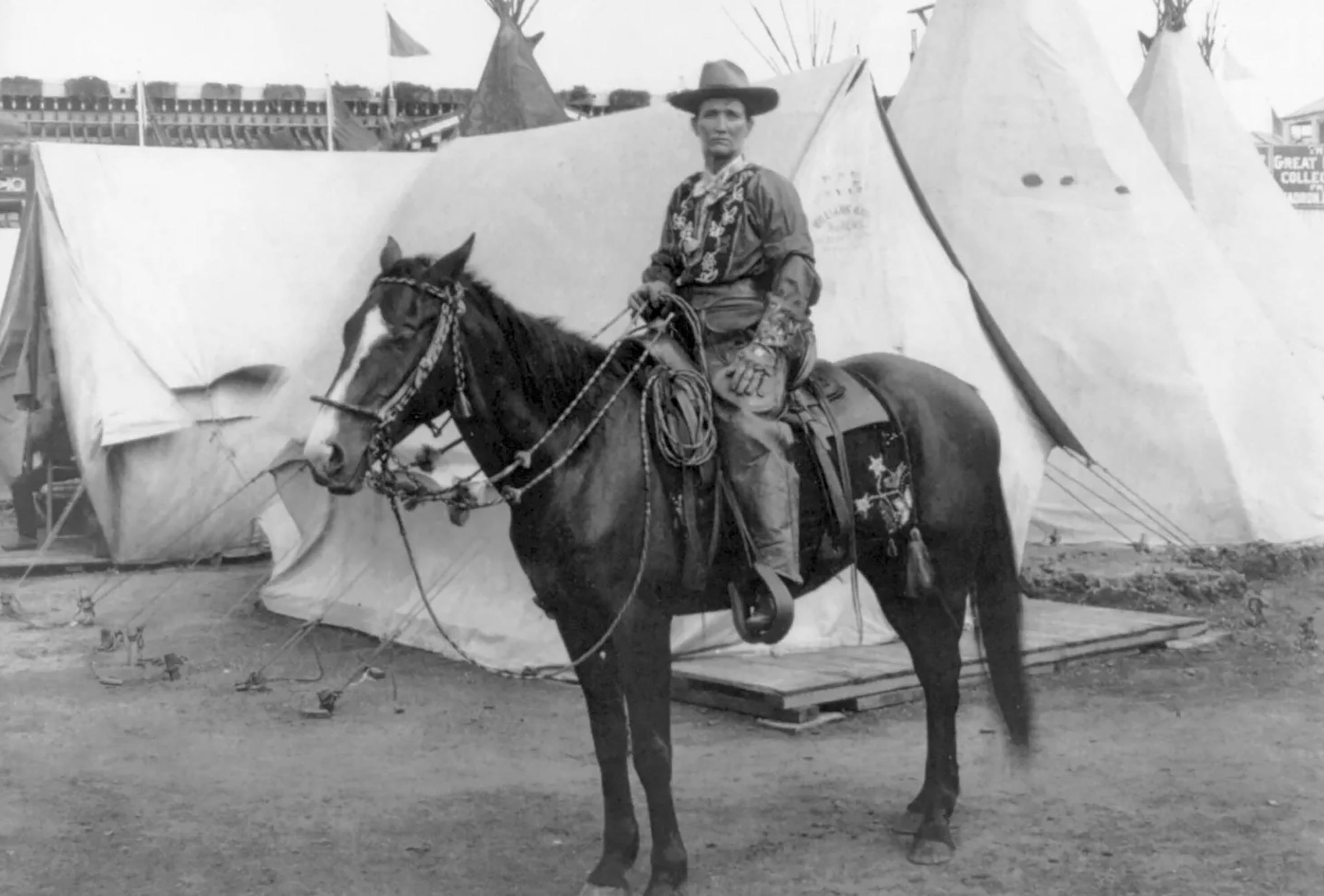

In Old Deadwood Days (1928), Estelline Bennett documents how “Jane alone took care of the smallpox patients in a crude log cabin pest house up in Spruce Gulch around behind White Rocks.” Dora DuFran (D. Dee), who knew Jane well, wrote in Low Down on Calamity Jane (1932) that during the smallpox epidemic Jane “would yell down to the placer miners in the gulch below for anything she needed, and throw down a rope by which to send supplies. They would bring what she required to the foot of the hill and she would haul them up hand over hand. Her only medicines were epsom salts and cream of tartar.” When patients died, Jane “wrapped them in a blanket and yelled to the boys to dig a hole. She carried the body to the hole and filled it up. She only knew one prayer, ‘Now I Lay Me Down to Sleep.’ This was the funeral oration she recited over the graves. But her good nursing brought five of these men out of the shadow of death, and many more later on, before the disease died out.” D. J. Herda also acknowledges in Calamity Jane (2018) that “everyone would have “Calamity Jane,” in full regala ca. 1895, during her years of employment as part of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show. died” without Jane’s care and attention.

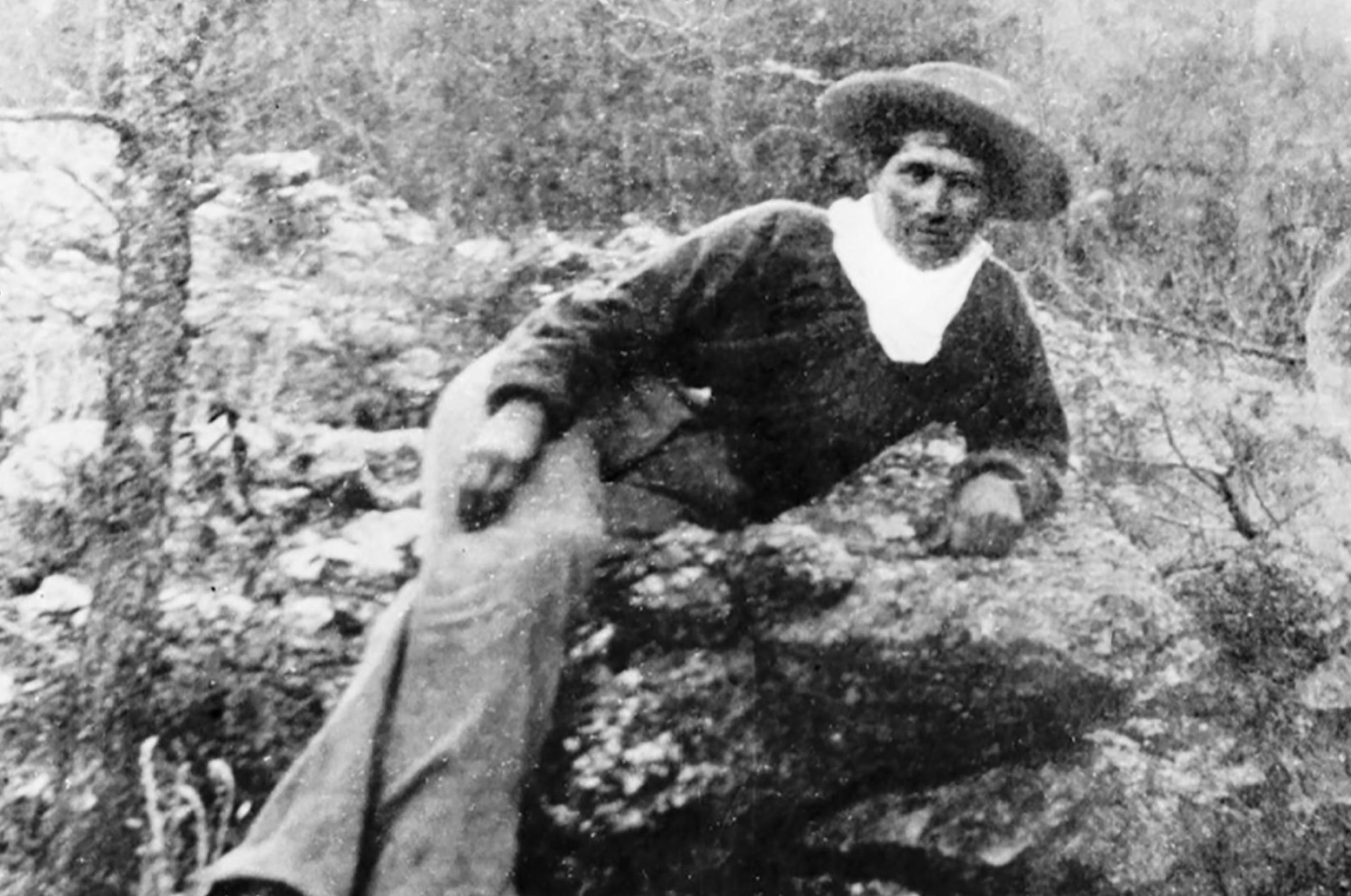

Martha Canary resting on a rock dressed in men’s clothing. Note on verso reads, “Said to have been taken in July, 1875 at Lower French Creek in the Black Hills when Calamity was 23 years old.

Beyond the epsom salts and cream of tartar, Jane’s medical supplies during the 1878 smallpox epidemic likely consisted only of herbs, sulfur, molasses, alcohol, and cool cloths for fevered brows. Without formal training or proper medications, she had to be led by compassion. A doctor did occasionally visit the Deadwood pest house, but even he believed that without Jane’s care not one of the patients would have survived.

Fortunately, Jane never contracted the disfiguring disease. Some believe she was immune because she was exposed to the disease as a child, but others attributed her survival to her “pickled” constitution.

Whatever the illness, injury, or problem afflicting people, Jane always seemed willing to help. In 1895, the Black Hills Daily Times featured an article about Jane that described how “she was one of the first to proffer her help in cases of sickness, accidents, or any distress.”

How Jane earned her nickname is a long-standing debate. Several explanations have been suggested and refuted, but it is interesting to note that many early authors attributed her sobriquet to her unselfish nursing activities during times of tribulations and calamities. Dora DuFran, for example, claimed that if anyone was sick, the message was to “send for Jane”—“where calamity was, there was Jane; and so she was christened Calamity Jane.”

Jane’s life of hard living caught up with her on August 1, 1903. She died of inflammation of the bowels—likely due to chronic alcoholism. Even though she led a rather nomadic life, Jane considered Deadwood to be her home. The lawless, rough, and tumble town had always suited her, and on her deathbed, she requested to be buried in Mount Moriah Cemetery in Deadwood beside Wild Bill Hickok. That request was honored.

Deadwood gave Jane an elaborate funeral, and during the service, the Reverend Charles B. Clark acknowledged her charitable acts by asking, “How often amid the snows of winter did this woman find her way to the lonely cabin” of a miner to help those “suffering from the diseases incident to those times?” In her obituary, the Sioux Falls Daily Argus-Leader noted the “deeds of mercy” Jane had performed “in a sick room or camp where women hardly ever ventured and ladies never.” The Spokane Press declared that “often in obscure cases of sickness, Jane was the first and only nurse,” and The Pine Bluff Daily Graphic noted that Jane “never refused to go even great distances to nurse the sick back to health.” That newspaper also confirmed that Jane would “stop abruptly even the incomparable pleasure of ‘shooting up’ a saloon full of miners bristling with guns if someone should call her to a sickbed.”

Accounts of Jane’s compassion and commitment to nursing are so abundant and persistent that today nursing schools, nursing journals, and nursing websites acknowledge and herald her contributions to the profession. The UT Health San Antonio School of Nursing, for example, lists Calamity Jane among the “Famous & Notable Nurses in History.” The Working Nurse journal describes Jane in a 2022 article as an “Angel of the Wild West” and as a “Hellion with a Heart of Gold.” The Gifted Healthcare website highlights Calamity Jane as an individual who made a major impact on the nursing profession, and in a post on the ARMStaffing website, she is included on the list of “important nurses who made the profession what it is today.”

Although much of Calamity Jane’s life was one of self-indulgence and hard-living, she also had a charitable and nurturing side to her personality. She may not have been “the ministering angel” exemplified by Florence Nightingale and Clara Barton, but she did nurse patients and advocate on their behalf. Nurse Jane’s caring and merciful deeds comforted many and saved the lives of many others.

Billie Holladay Skelley, a retired clinical nurse specialist, earned her bachelor’s and master’s degrees at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. She has written several health-related articles for both professional and lay journals, but her writing crosses different genres and has appeared in various journals, magazines, and anthologies in print and online—ranging from the American Journal of Nursing to Chicken Soup for the Soul. An award-winning author, she has written twelve books for children and teens. Her book, Ruth Law: The Queen of the Air, was selected to receive the 2021 American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AIAA) Children’s Literature Award, and her book, Bass Reeves: Legendary Lawman of the Wild West, received a 2024 Will Rogers Medallion Award and a 2024 Spur Award.