Supporting Students to Think Creatively What Education Policy Can Do

PISA tests the skills and knowledge of 15-year-old students around the world in reading, mathematics and science because they are foundational to a student’s ongoing education. Since 2000, PISA has involved more than 90 countries and economies and around 3 million students worldwide.

PISA also collects valuable information on student attitudes and motivations, and since its 2012 cycle, formally assesses important ‘21st century skills’ such as problem solving (2012), collaborative problem solving (2015), and global competence (2018).

For the first time, in its 2022 cycle, PISA will assess creative thinking in over 60 participating countries and economies. To find out more about innovation in PISA, visit our innovation webpage at www.oecd.org/pisa/innovation

There is a growing consensus globally on the importance of fostering creativity and creative thinking through education. This publication explores how education systems are integrating creative thinking in formal education, the type of initiatives they are putting in place and the main challenges they encounter. It builds on qualitative information collected through an online questionnaire, which was directed to PISA 2022-participating jurisdictions and obtained completed responses from 90 jurisdictions, including national and subnational jurisdictions from OECD and partner countries and economies, between October and December 2022.

The PISA 2022 System-Level Questionnaire on Creative Thinking asked jurisdictions about their inclusion and prioritisation of creative thinking in different areas of education policy, including curricula, assessment, teacher training and learning environments. Education systems were asked about the role of creative thinking in formal education goals, its presence in education programmes and partnerships, and within teacher and school support mechanisms at the system level. This report is part of a wider effort by the OECD to encourage an international discussion on the importance of creative thinking in education, and to encourage positive changes in education policies and pedagogies around the world.

This report is the product of a collaborative effort between the countries participating in PISA and the OECD Secretariat, under the guidance of Andreas Schleicher, Director for Education and Skills, and Yuri Belfali, Head of the Early Childhood and Schools Division. The report was prepared by Marc Fuster, with the support of Marta Cignetti, Natalie Foster and Mario Piacentini, and with the external support of Sarah Grillo (consultant) and Bill Lucas (University of Winchester). Della Shin designed it and laid it out, and Stephen Flynn, Sophie Limoges and Cassandra Morley provided communications support. The authors would like to thank Fonzy Nils for the creative illustrations, and the LEGO Foundation for their generous support to the project.

Creative thinking is increasingly seen as a key competency that young people need for the future, and virtually all education systems formally recognise the role that schools and teachers can play in supporting its development.

Most PISA 2022-participating jurisdictions consider creative thinking a cross-curricular competency, although references to creativity in curricula are more common in the arts and language subjects, followed by technology, science and mathematics.

Thinking creatively – including in school – is critical for several reasons: creative thinking is a major currency in the job market, it supports individuals’ well-being and helps them reflect upon and interpret information in novel and meaningful ways. Pedagogies that engage with students’ creative thinking increase their motivation for learning, promoting cognitive activation, deeper, transferable learning.

All the same, several challenges exist for the systematic integration of creative thinking into everyday educational practices.

Policymakers from over half the jurisdictions responding to the questionnaire flagged overcrowded curricula and insufficient teaching time, a lack of assessment focus on creativity, and a lack of teacher training or pedagogical resources as challenges.

Teachers can play a central role in fostering students’ creativity by using pedagogies that, balancing structure and freedom, encourage students to explore, generate and reflect upon ideas. But changing curricula alone is not enough for practitioners to recognise, promote, and reward their students’ creativity effectively and consistently. Translating new curricular goals into related educational practices requires both enablers and incentives.

One key enabler is teacher education and training, which can provide clear frameworks of what creative thinking is and how it can be taught and assessed across subjects.

System-level guidelines or requirements governing initial teacher education and training referred to developing students’ creativity in less than 70% of PISA 2022-participating jurisdictions with data available. References to assessment were even rarer (present in less than 50% of jurisdictions).

Additional system-level enablers include the provision of teaching materials, teacher professional development and targeted funding for creative projects and programmes in schools and for equipment and infrastructure. Promoting the collaboration of schools and teachers with creative practitioners in other sectors can also be key. Partnerships and networks mobilise knowledge, trust and leadership, and can support innovation to take root and scale.

Support in the form of teaching resources and professional development for teachers was more common than support for crosssectoral partnerships.

Together with enablers, teachers need incentives when seeking to reflect on, experiment with and gradually evolve their practice. As signposts of what students should learn and be able to do, systemlevel assessment and evaluation frameworks have a strong influence on teaching and learning. A focus on creative thinking in assessment can promote shared understanding about what it is and the type of outcomes to be expected of students across disciplines and education levels. Contrarily, assessments that omit creative thinking, for instance, by adopting a strong orientation towards the reproduction of pre-defined knowledge as opposed to original thought and different forms of expression, can act as disincentives to creativity education.

In 2022, only 24% of PISA-participating jurisdictions had formal system-level guidelines (e.g. learning progressions, rubrics) or evaluations on creative thinking in place in their education system.

Figure 1 [1/3] Integrating creative thinking in education: How do jurisdictions compare?

A Do guidelines for initial teacher training for secondary education reference…

B Does your jurisdiction provide the following support mechanisms to teachers and schools to help foster students’ creativity?

C Share of school subjects that reference creative thinking in secondary education curricula

D Does your jurisdiction have system-level guidelines or evaluations to assess students’ creativity?

Flemish Community (Belgium)

(Belgium)

French-speaking cantons (Switzerland)

German-speaking cantons (Switzerland)

German-speaking Community (Belgium)

A Do guidelines for initial teacher training for secondary education reference…

B Does your jurisdiction provide the following support mechanisms to teachers and schools to help foster students’ creativity?

C Share of school subjects that reference creative thinking in secondary education curricula

D Does your jurisdiction have system-level guidelines or evaluations to assess students’ creativity?

(Canada)

/ 11

A Do guidelines for initial teacher training for secondary education reference…

B Does your jurisdiction provide the following support mechanisms to teachers and schools to help foster students’ creativity?

C Share of school subjects that reference creative thinking in secondary education curricula

D Does your jurisdiction have system-level guidelines or evaluations to assess students’ creativity?

Notes: OECD countries are shown in bold black. Regions of OECD countries are shown in black italics. Partner countries and economies are shown in bold blue.

Jurisdictions are ranked in alphabetical order.

Source: OECD, PISA 2022 System-Level Questionnaire on Creative Thinking.

PISA 2022-participating jurisdictions that responded to the system-level survey on policies fostering creative thinking in education, October-December 2022

Alberta (Canada)

Australian Capital Territory (Australia)

Austria

British Columbia (Canada)

Chile

Colombia

Costa Rica

Czech Republic

Denmark

England (United Kingdom)

Estonia

Faroe Islands (Denmark)

Finland

Flemish Community (Belgium)

France

French Community (Belgium)

French-speaking cantons (Switzerland)

German-speaking cantons (Switzerland)

German-speaking Community (Belgium)

Germany

Greece

Hungary

Iceland

Ireland

Israel

Italy

Japan

Korea

Latvia

Lithuania

Manitoba (Canada)

Mexico

Netherlands

New Brunswick (Canada)

New South Wales (Australia)

New Zealand

Newfoundland and Labrador (Canada)

Northern Ireland (United Kingdom)

Northern Territory (Australia)

Norway

Nova Scotia (Canada)

Ontario (Canada)

Poland

Portugal

Prince Edward Island (Canada)

Quebec (Canada)

Queensland (Australia)

Saskatchewan (Canada)

Scotland (United Kingdom)

Slovak Republic

Slovenia

Spain

Sweden

Tasmania (Australia)

Türkiye

Wales (United Kingdom)

Albania

Baku (Azerbaijan)

Brazil

Brunei Darussalam

Bulgaria

Cambodia

Croatia

Dominican Republic

El Salvador

Hong Kong (China)

Indonesia

Jamaica

Jordan

Kazakhstan

Macao (China)

Malaysia

Mongolia

Montenegro

North Macedonia

Palestinian Authority

Panama

Paraguay

Peru

Philippines

Qatar

Romania

Serbia

Singapore

Chinese Taipei

Thailand

Ukraine

Uruguay

Uzbekistan

Viet Nam

What are we talking about, why should we care and how do we go about it?

Integrating creativity in education: What are we talking about, why should we care and how do we go about it?

The literature broadly understands creativity as “the interaction among aptitude, process and environment, by which an individual or group produces a perceptible product that is both novel and useful as defined within a social context” (Plucker, Beghetto and Dow, 2004, p. 90[1]). Several theories of creativity acknowledge the importance and interaction of relevant knowledge and skills, divergent and convergent thinking processes, task motivation, and a rewarding environment for supporting creative engagement with a given task (Amabile, 1983[2]; Amabile and Pratt, 2016[3]; Lucas, Claxton and Spencer, 2013[4]; Lucas, 2016[5]; Sternberg and Lubart, 1991[6]; Sternberg and Lubart, 1995[7]; Sternberg, 2006[8]).

The literature on creativity generally distinguishes between ‘big C’ creativity and ‘little c’ creativity (Craft, 2001[9]; Kaufman and Beghetto, 2009[10]). ‘Big C’ creativity refers to intellectual or technological breakthroughs or artistic or literacy masterpieces, requiring significant expertise, dedication, and recognition from society that the product has value. Conversely, all people are capable of demonstrating ‘little c’ creativity by engaging in creative thinking. This type of everyday creativity might include arranging photos in an unusual way, combining leftovers to make a tasty meal, or finding a solution to a complex scheduling problem at work. Overall, the literature agrees that ‘little c’ creativity can be developed through practice and honed through education (Kaufman and Beghetto, 2009[10]).

While intrinsically related to the broader construct of creativity, creative thinking refers to the cognitive processes required to engage in creative work. Creative thinking is a malleable individual capacity that can be developed through practice and does not place an emphasis on how wider society values the resulting output (OECD, 2022[11]).

PISA defines creative thinking as “the competence to engage productively in the generation, evaluation, and improvement of ideas that can result in original and effective solutions, advances in knowledge, and impactful expressions of imagination”.

This definition focuses on the cognitive processes and outcomes associated with ‘little c’ creativity in everyday contexts. It reflects the types of creative thinking that 15-year-old students can reasonably demonstrate, and underlines that students need to learn how to engage productively in generating ideas, reflecting upon ideas by valuing their relevance and novelty, and iterating upon ideas until they reach a satisfactory outcome.

A fundamental role of education is to equip students with the competences they need to succeed in life and society. Being able to think creatively is a critical competence that young people need to develop – including in school – for several reasons:

• Creative thinking helps prepare young people to adapt to a rapidly changing world that demands flexible workers (WEF, 2023[12]). Children today will be employed in jobs that do not yet exist, using new technologies to solve novel problems and emerging challenges. Developing creative thinking will help prepare young people to adapt, undertake work that cannot easily be replicated by machines, and address increasingly complex challenges with innovative solutions.

• Creative thinking supports learning by helping students to interpret experiences and information in novel and personally meaningful ways, even in the context of formal learning goals (Beghetto and Kaufman, 2007[13]; Beghetto and Plucker, 2006[14]). Pedagogies that engage with students’ creative thinking increase their motivation and interest in learning, promoting cognitive activation, deeper, transferable learning.

• Creative thinking has a positive impact on the well-being of young (and older) people (Acar et al., 2020[15]; Csikszentmihalyi, 1996[16]). It helps students to discover and develop their potential. Schools play an important role in students’ development beyond preparing them for success in the labour market. Schools must also help young people to discover and develop their talents, including their creative talents (Lucas and Spencer, 2017[17]).

• Creative thinking is important in a range of subjects, from languages and the arts to the STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) disciplines. Creative thinking helps students to be imaginative, develop original ideas, think outside the box, and solve problems.

Formal curricula indicate what education decision-makers, and society more widely, value. Curricular reform is hence often the first step to take when pursuing new goals for the education system (Gouëdard et al., 2020[18]; Fadel, 2021[19]; Lucas and Venckutė, 2020[20]; Wyse and Ferrari, 2014[21]). Integrating creative thinking in formal curricula indicates that this is not only a highly desirable competency but also a teachable one and that all students can develop it. Curricular integration can signal that creative thinking can be nurtured in all curricular areas, and that it is a robust and visible enough concept to be assessed.

Learning environments which are conducive to creative thinking create a culture in which there is time for students to explore and generate ideas, to engage in challenging, authentic tasks, and to play and collaborate within safe environments where “failure” is reframed as learning (Cremin and Chappell, 2019[22]; Vincent-Lancrin et al., 2019[23]). A powerful force for change is provided by teachers modelling the kinds of behaviours conducive to fostering creative thinking. Practitioners and schools need support to design and sustain such environments, including to professional learning and collaboration opportunities and to relevant pedagogical, regulatory and financial tools, such as teaching materials, autonomy and funding (Davies et al., 2013[24]). Specifically they need a clear understanding of creative thinking so that they can embed it across the curriculum and an understanding of the kinds of pedagogies which will be most effective (Lucas and Spencer, 2021[25]).

There are at least three reasons why assessing creative thinking matters. First, assessment functions as a mark of status. We treasure what we measure and measuring creative thinking is hence a clear indication of its value. Second, assessment is a means of building common understanding. Creative thinking is gaining momentum in education, but it often means different things to different people. Assessing it implies defining it, and so forging a common understanding. Thirdly, assessment is a tool that drives improvement. It can help us better understand what educational approaches work and for whom. It is key to facilitate reflection upon existing policies and practices and to inform changes as needed (Lucas, 2022[26]; Lucas, Claxton and Spencer, 2013[4]).

Successful policy reform requires both political will and robust evidence to inform good decision-making. There is less evidence on how to support creative thinking than in more well-researched areas such as, for example, the teaching of science or mathematics. However, new models of contemporary curriculum provide guidance on how creative thinking can be embedded in several disciplines and supported through cross-disciplinary activities (Vincent-Lancrin et al., 2019[23]; Lucas, 2022[26]). These frameworks are stimulating new research on what works across the different areas on which systems need to focus –curriculum design, pedagogy, assessment, leadership.

Policies are not designed and implemented in a vacuum. The success of reforms requires coherence of intents among education stakeholders, allocation of sufficient time to enable changes in institutions and practices, and recognition of the diversity of needs across local contexts. A whole of system approach works to align policies, roles and actions across the system, considering the resources needed to implement policy changes and the contextual factors and incentives that facilitate or hinder their implementation (Burns and Köster, 2016[27]; LEGO Foundation, 2022[28]).

A key element of successful governance is ensuring that stakeholders have sufficient capacity to assume their roles and deliver on their responsibilities. Stakeholders, notably school leaders and practitioners, need adequate knowledge of policy goals, the autonomy and willingness to adapt to changes, and the appropriate tools to make it happen. Open dialogue and communication in defining such goals and processes reinforces legitimacy and ownership. Explicit efforts to build capacity, such as targeted resources and access to relevant professional development, are also necessary. Capacity building efforts must remain responsive to the diversity of needs and experiences of local contexts (Burns, Köster and Fuster, 2016[29]).

Most education stakeholders agree that creative thinking is a key competency for life and work in contemporary societies. From this perspective, much attention is shifting to curricula. Integrating creative thinking in curricula recognises that creativity is not a competency restricted to a talented few, but one that can be taught and learnt, and that all learners can develop. Curricula and standards provide the reference framework for what students should learn and teachers teach in a system, and their reform is commonly the first step to adapt education to evolving social demands (OECD, 2020[30]).

Nonetheless, successful curricular reform requires careful attention to implementation. Successful reform builds on empowering educators and school leaders to take ownership of the new goals and move them forwards, and intentional, coherent policy efforts are needed to build capacity towards this end. Capacity is necessary for teachers to develop a shared understanding of what creative thinking is and how to teach it; and at the level of institutions and larger systems, which define the conditions for educators to effectively experiment, collaborate and gradually innovate their practice (Gouëdard et al., 2020[18]).

• Creative thinking, or related terms (e.g. creativity, innovation), are increasingly present in curricula internationally, although its integration varies across domains. Creative thinking is most referenced in relation to arts and language subjects (about 90% of jurisdictions’ curricula for both primary and secondary education), followed by technology, science and mathematics, which include references to creative thinking in the curricula of about 80% of jurisdictions.

• Asked about the main challenges facing the integration of creative thinking in education, policymakers across PISA 2022-participating jurisdictions flagged an overcrowded curriculum/lack of teaching time (53% of jurisdictions), a lack of assessment focus on creativity (52%) and a lack of teacher training or pedagogical resources (51%) as the main obstacles.

• References to creative thinking in curricula rarely come together with system-level guidelines (e.g. learning progressions, rubrics) or evaluations signalling what creative thinking is and how it is learnt. Only few jurisdictions report having such instruments in place (24%) or being currently in the process of developing them (10%).

• Results from the PISA questionnaire show that teacher qualifications and training requirements refer to students’ creativity in less than 70% of jurisdictions where such requirements exist. References to assessing students’ creativity are even rarer, and only present in less than half of jurisdictions with data available.

• Many jurisdictions seek to build teachers’ and schools’ capacity to foster the creativity of their students. Most commonly, means of support include the provision of teaching materials and professional development opportunities for teachers (between 64% and 69% of jurisdictions). Other support mechanisms include funding for creativity-related projects (54%) and for equipment and infrastructure (45%). Despite existing evidence on their positive contribution to teachers’ professional learning, support for cross-sectoral collaboration and practitioner research is less commonly available. Only 42% and 39% of jurisdictions, respectively, offer such type of support.

Most PISA-participating jurisdictions have formal curricula or learning standards that govern the education system. In some jurisdictions, curricula are articulated in a single, integrated document (56% jurisdictions for primary and 48% for secondary education), while in others, there are separate disciplinary curricula or standards documents (38% and 45% jurisdictions for primary and secondary education respectively) or other forms of curricular organisation (in 6% and 7% of jurisdictions respectively). In jurisdictions where curricula or standards are integrated in a single document (48 for primary education and 40 for secondary education), they contain references to creative thinking or associated terms (e.g., creativity, innovation) in all but one of the jurisdictions surveyed.

Experts agree that creative thinking can emerge and be taught in all school subjects (OECD, 2022[11]) and that some habits of mind and cognitive processes support people’s ability to think creatively in different domains (Treffinger et al., 2002[31]). However, creative thought and products draw upon domain-specific knowledge and skills, and students may benefit from practicing it in the context of specific curricular areas (VincentLancrin et al., 2019[23]). In this sense, if the job of teachers is to design opportunities to integrate creative thinking into the discipline(s) they teach, the job of curriculum designers may consist of clearly mapping the opportunities to embed creative thinking across curricular areas, a process that Lucas and Spencer (2017[17]) describe as ‘split-screen thinking’. In this metaphor, they imagine two screens: one has the knowledge and skills that appear on a conventional syllabus, the other has creative habits and skills. With these two “screens”, curriculum designers must identify opportunities to interweave creative thinking across learning areas.

To understand how education jurisdictions integrate creative thinking in curricula, PISA asked jurisdictions with a single, integrated curriculum or standards document to indicate if creativity is referenced as 1) a priority cross-cutting theme or competency; 2) within the umbrella of 21st century skills/competencies, and/or 3) in specific disciplines. As shown in Figure 2, most jurisdictions indicated that the first is true (65% in primary education curricula and 70% in secondary education), and so that creativity is explicitly recognised in its own as a goal for all disciplines. A lower percentage of jurisdictions reported that creative thinking is referenced in specific disciplinary contexts (58% for primary education curricula and 53% for secondary education). Lastly, creativity is referenced more generally as part of a larger set of transversal competencies, such as critical thinking or socio-emotional skills in 35% and 45% of jurisdictions.

Fostering creative thinking through education: Drivers, barriers and indicators of progress

or

by

Albania

Austria

Baku (Azerbaijan)

Brazil

Bulgaria

Cambodia

Chile

Colombia

Czech Republic

Denmark

Dominican Republic

England (United Kingdom)

Estonia

Finland

French Community (Belgium)

French-speaking cantons (Switzerland)

German-speaking cantons (Switzerland)

Hungary

Iceland

Indonesia

Ireland

Italy

Japan

Kazakhstan

Korea

Latvia

Lithuania

Malaysia

Mexico

Mongolia

Netherlands

New Zealand

Northern Ireland (United Kingdom)

Norway

References to creativity in single, integrated curricula or standards, by type and level of education, 2022

Palestinian Authority

Paraguay

Peru

Philippines

Poland

Portugal

Qatar

Queensland (Australia)

Scotland (United Kingdom)

Spain

Sweden

Thailand

Ukraine

Uruguay

Uzbekistan

Viet Nam

Wales (United Kingdom)

Notes: For each subject, the share of cases in which they reference creative thinking is based on the number of jurisdictions that reported the subject containing reference to creative thinking or related terms, over the number of valid responses for the subject (see N reported in brackets). Survey responses that indicated that it was not possible to establish whether the subject made reference to creative thinking were counted as missing responses and thus not included in the valid response count.

In the Figure, ‘primary education’ refers to ISCED level 1, and ‘secondary education’ to ISCED levels 2 and 3. In some jurisdictions, the curricula or standards documents for primary (ISCED level 1) and lower secondary education (ISCED level 2) are integrated. In these cases, ‘primary education’ refers to both primary and lower secondary education (ISCED levels 1 and 2) and ‘secondary education’ refers to upper secondary education (ISCED level 3).

Source: OECD, PISA 2022 System-Level Questionnaire on Creative Thinking.

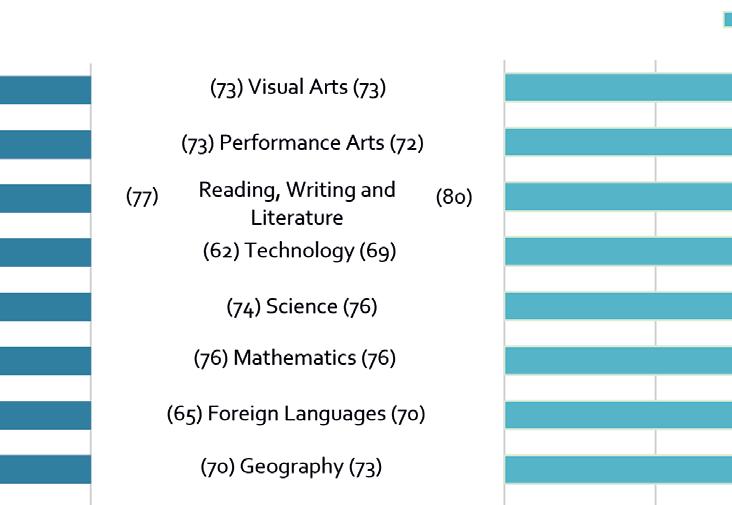

Analysing whether references to creative thinking or similar terms exist for each particular subject or curricular domain is one way to observe the degree to which creativity is effectively understood as a cross-curricular theme or competency. To this end, PISA asked participating jurisdictions in the survey which of the following subject areas, if present in the curricula or learning standards of their education system, explicitly refers to creativity or related terms: 1) reading, writing, and literature (native or national language); 2) modern foreign

languages; 3) mathematics; 4) sciences (biology, chemistry, physics); 5) history 6) geography; 7) visual arts (studio arts, design); 8) performance arts (dance, music, drama); 9) technology and computer science/ICT; 10) physical education; and 11) citizenship.

Survey results (Figure 3) show that references to creative thinking in primary education curricula are most common in the domains of visual arts (93% of jurisdictions), performance arts (92%), and reading, writing and literature in the native language (86%). In secondary education, creative thinking is also more commonly referenced with regards to the visual and performance arts (90% and 88% of jurisdictions respectively) as well as technology (88%) and reading, writing and literature in the native language (86%). In contrast, references to creative thinking in primary education curricula are less common in the domains of physical education (60% of jurisdictions), history (59%) and citizenship (56%). Similar patterns are observed in secondary education, with references to creative thinking in history, citizenship and physical education in 64%, 62% and 58% of jurisdictions’ curricula respectively.

Different “everyday” forms of creative work are possible across subjects. Students’ capacity to think creatively may manifest itself as students explore issues and create new knowledge (in a group), as they engage in finding multiple solutions to different kinds of problems, and as they express their imagination for example through design, writing or digital creations (OECD, 2022[11]). Previous comparative research had found that the notion of creativity as self-expression was most common in education, with curricula narrowly defining creative school-related work as pertaining specifically to arts subjects (Patston et al., 2021[32]; Wyse and Ferrari, 2014[21]). In their analysis of education curricula in the European Union and the United Kingdom, Wyse and Ferrari also flagged a lack of attention to creativity in the subject group of languages, even though creative thinking plays an important role in the writing process (Wyse and Ferrari, 2014[21]). The results of the PISA survey only partially align with these findings, suggesting that progress in integrating creative thinking across curricula has been made.

Percentage of jurisdictions where the following domains/school subjects refer to creativity in system-level curricula or learning standards, by level of education, 2022

Notes: For each subject, the percentages in the bar chart is based on the number of jurisdictions that reported the subject containing reference to creative thinking or related terms, over the number of valid responses for the subject (see N reported in brackets). Survey responses that indicated that it was not possible to establish whether the subject made reference to creative thinking were counted as missing responses and thus not included in the valid response count.

In the Figure, ‘primary education’ refers to ISCED level 1, and ‘secondary education’ to ISCED levels 2 and 3. In some jurisdictions, the curricula or standards documents for primary (ISCED level 1) and lower secondary education (ISCED level 2) are integrated. In these cases, ‘primary education’ refers to both primary and lower secondary education (ISCED levels 1 and 2) and ‘secondary education’ refers to upper secondary education (ISCED level 3).

Source: OECD, PISA 2022 System-Level Questionnaire on Creative Thinking.

Having recognised the importance of fostering students’ creativity in the goals for the education system, the natural progression is for educators to incorporate teaching practices that support learners in appropriate ways. Teaching professionals can support their students’ creative thinking, but doing so entails intentionality from educators who use pedagogies which, balancing structure and freedom, encourage students to explore, generate and reflect upon ideas (Cremin and Chappell, 2019[22]; Vincent-Lancrin et al., 2019[23]).

Research has underlined that embedding creativity in curricula alone is not enough for practitioners to support students’ creative thinking. Different factors may stand in the way of achieving the intended curriculum, including: a lack of clarity on what creative thinking is, how it is taught and learnt across disciplines and the type of outcomes to be expected of students as they progress in their learning; a hostile environment for educators to reflect on, experiment and progressively adapt their teaching; and the absence of adequate incentives for students and teachers to engage in creative thinking practices (Vincent-Lancrin et al., 2019[23]; Davies et al., 2014[33]; Lucas, 2022[26]; Cachia et al., 2010[34])

In traditional curricular areas, learning progressions describe how students move through different stages in their learning. Concrete exemplars of expected learning along with specific criteria to assess performance, such as scoring rubrics, may also be available (OECD, 2013[35]). In such areas, teachers and other assessment designers tend to be aware of the knowledge and skills expected of students and the typical learning trajectories they follow to acquire them, but what is true for mathematics or reading may not be so common for creative thinking.

Previous comparative analyses already have indicated that creativity is finding its way into curricula, but it does so differently in different jurisdictions. In some cases, the case for creativity is articulated in detail, providing rationale for its importance and guidelines to teach and assess it. In others, creativity is introduced as a general principle, and only referenced superficially, with little attention to progressions and teaching guidelines (Patston et al. (2021[32]); Care et al. (2018[36]); Taylor et al. (2020[37])). Vagueness about the concrete nature and expected outcomes of creative thinking translates into unclear priorities for educators. While teachers value creativity as an important goal, common understanding on what it means, what key features define it and how it develops in learners is lacking (Mullet et al., 2016[38]). Clarity on learning outcomes and progressions is nonetheless particularly relevant for teaching complex competencies that, like creative thinking, can manifest validity in multiple ways and are defined by both thought processes and behaviours (Foster and Piacentini, 2023[39]).

Teachers’ beliefs about the nature of creative thinking and its outcomes can support or hinder its development in students. Teacher beliefs relate to their conceptions about the nature of creativity, including its definition (i.e. aspects of originality but also appropriateness), distribution (i.e. whether all learners can develop it), malleability (i.e. the extent to which it can be taught and learnt), and domain specificity (i.e. whether it can be exercised in all subjects); and about who creative individuals are, including learners (i.e. the outcomes to be expected of them, across different groups of students), and teachers themselves (i.e. the knowledge, skills and attitudes creative teachers have) (Bereczki and Kárpáti, 2018[40]).

Box 1 Creating a common language to teach and assess creative thinking

The OECD Centre for Educational Research and Innovation (CERI) carried out the project “Fostering and Assessing Creativity and Critical Thinking in Education”, which aimed to develop a shared professional language on creativity and critical thinking in primary and secondary education and facilitate its teaching, learning and formative assessment across 11 education systems: Brazil, France, Hungary, India, the Netherlands, the Russian Federation, the Slovak Republic, Spain, Thailand, the United Kingdom (Wales) and the United States. The project is continuing with a focus on teacher education and higher education.

As part of this project, a series of rubrics on creativity were developed and field trialled. The rubrics were incrementally developed during the project and improved based on teachers’ and project co-ordinators’ feedback following the field trial. Conceptual rubrics were designed to clarify “what counts” or “what sub-skills should be developed” in relation to creativity, guide the design of lesson plans and help practitioners be more intentional and consistent in their teaching of creative skills. Research-informed sub-skills were included in domain-general and domain-specific rubrics, under the broader, easy-to remember skills: inquiring, imagining, doing and reflecting.

The project also developed assessment rubrics, which teachers and students can use for formative or summative purposes. The rubrics articulate four levels of progression or proficiency in the acquisition of creative skills, ranging from cases where students exhibit little effort to exercise creativity (Level 1) to those where students show a high level of creativity and technical mastery (Level 4). They focus on both creative products and processes: ”Product” refers to a visible, final work (e.g. the response to a problem, an essay, an artefact of a performance) and “Process” to the learning and production steps observed by the teachers or documented by the students, which may not be entirely visible in the final product.

Additionally, a set of design criteria for lesson plans and over 100 peer-reviewed examples of lesson plans with a focus on nurturing creativity and critical thinking in different subjects was also developed by experts and teachers participating in the project. These examples aim to inspire teachers by illustrating the kind of approaches and tasks that allow students to develop their creative and critical thinking while acquiring the content and procedural knowledge across different domains of the curriculum. Both the lesson plans and rubrics are publicly available as open educational resources.

Note: The rubrics as well as a number of interdisciplinary and discipline-specific lesson plans developed by this project are available at https://www.oecd.org/education/fostering-students-creativity-and-critical-thinking62212c37-en.htm and www.oecdcericct.com

Source: Vincent-Lancrin et al. (2019[23]), Fostering Students’ Creativity and Critical Thinking: What it Means in School, https://doi.org/10.1787/62212c37-en

Previous studies on the integration of creativity in education have highlighted that while certain pedagogical practices can support students to think creatively, these are not commonly practiced by teachers and students in schools (e.g. Cachia et al. (2010[34])). Innovating teaching and learning is fundamentally a problem-solving exercise. Teachers identify a need (e.g. fostering students creative thinking) and mobilise knowledge to implement changes accordingly. In this process, the knowledge they mobilise is sometimes explicit, resulting from study during formal education and training and as part of their daily practice, and often tacit, fruit of their own experience, reflection and exchange with colleagues (Révai and Guerriero, 2017[41]; Paniagua and Istance, 2018[42]). Professional learning and innovation thus go hand in hand. They benefit from access to pre-service and in-service training, especially when its provision affords opportunities for experiential, hands-on and collaborative learning. They are more broadly supported by a working culture providing safe spaces for teachers to try out and develop new pedagogical approaches collaboratively, and the extent to which this is promoted systematically by school leaders and regulatory frameworks (OECD, 2019[43]; OECD, 2019[44]; OECD, 2013[35]).

As expectations of schooling rise, the emphasis on advanced competencies like creative thinking coexist with ambitions to maintain or even increase the breadth of curricular content covered. This results in scarce time for teachers to engage in both collaborative reflection on and experimentation with creativity-supportive pedagogies. Processes of joint planning and collegiate exchange among educators can be further challenged by school structures that, for the most part, remain organised by strong disciplinary divisions (e.g. syllabuses, timetables, teaching departments), and more generally by an extended view of teaching as an individual, siloed practice (OECD, 2019[43]).

The physical space of learning environments can also have an impact on the capacity of educators to promote creativity. On the one hand, some forms of creative work may demand special equipment and modernised facilities. Engaging students in the construction of artefacts requires specific tools – whether these are physical objects produced in technology and arts activities, or videos, websites and blogs in the context of language or history, for example. On the other hand, the design of physical spaces influences the relations and practices that are possible within them. The physicality of “the classroom” can facilitate or hinder the capacity to combine different types of tasks during instruction, including play, manual work or study, and the use of different grouping strategies, with students working individually or in groups and teachers engaging in team teaching (OECD, 2013[45]). This has particular relevance for the use of instructional strategies incorporating more freedom for students to explore and make choices, which often entail students and teachers engaging in longer, complex tasks involving different forms of doing and making and requiring more flexible and open spaces (Davies et al., 2013[24]).

As signposts of what students should learn and be able to do, student assessments highlight the knowledge and competencies that society values and, in so doing, can have an enabling or constraining effect on teaching and learning practices. The effects are likely to be larger when assessments carry high stakes for students, like at the end of upper secondary education, when examinations have a strong influence over future educational and employment trajectories (OECD, 2013[35]).

Student assessments can have a constraining effect on creativity education if they omit creative thinking in their evaluation criteria – for instance, when they have a strong orientation towards the reproduction of pre-defined knowledge as opposed to original thought and acceptance of difference forms of expression. Student assessments can also disincentivise some aspects of creative thinking when they focus on some subjects at the expense of others (e.g. testing mathematics but not visual arts), and therefore neglect the types

of creative work more commonly associated with specific domains of knowledge. Assessments that positively contribute to creative thinking are capable of generating evidence on how students deal with complex situations and iterate towards solutions, which demands the use of multiple, open-ended assessment tasks (e.g. projects, presentations) and tools (e.g. rubrics, portfolios) for teachers and other assessment designers to be able to document a wide range of student performances (Vincent-Lancrin et al., 2019[23]; Beghetto, 2020[46]; Lucas, 2022[47]; Foster and Piacentini, 2023[39]).

The ways in which schools are evaluated have similar enabling and constraining effects on the adoption of innovative pedagogies. This concerns not only the criteria used by external evaluators, but also the extent to which schools consider creative thinking an important learning outcome in their self-evaluations. Additionally, it relates to the views and concerns of other, increasingly vocal stakeholders, such as families and the media. The views of stakeholders on what good education is do not always align, which generates competing demands for educators (Burns, Köster and Fuster, 2016[29]).

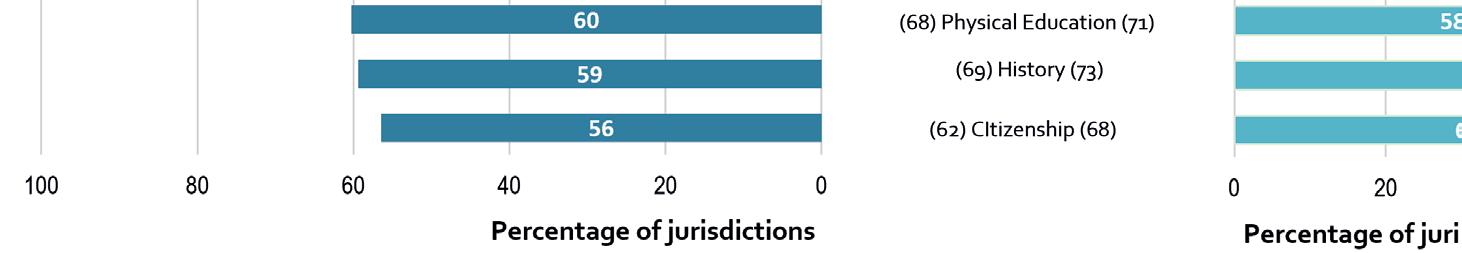

To shed light on the specific barriers facing the systematic integration of creative thinking in schools and classrooms, PISA asked policymakers which of the following issues, if any, challenge the capacity of their jurisdiction to develop students’ creativity: 1) overcrowded curriculum (lack of teaching time); 2) focus on preparing students for high stakes examinations; 3) lack of training or pedagogic resources for educators on developing students’ creativity; 4) lack of appropriate facilities, equipment and/or materials in schools; 5) lack of assessment focus on creativity; 6) lack of system-level guidelines, standards, or learning progressions on developing creativity; 7) unclear evidence supporting the integration of creativity in education; 8) lack of political will or high-level strategy focused on developing creativity in education; 9) general financial constraints; or 10) other.

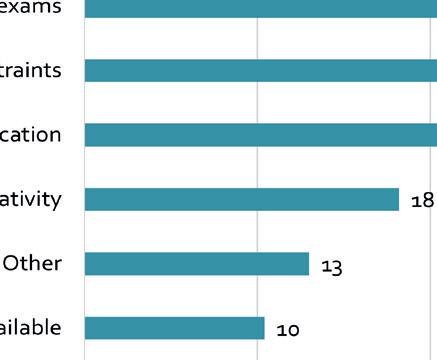

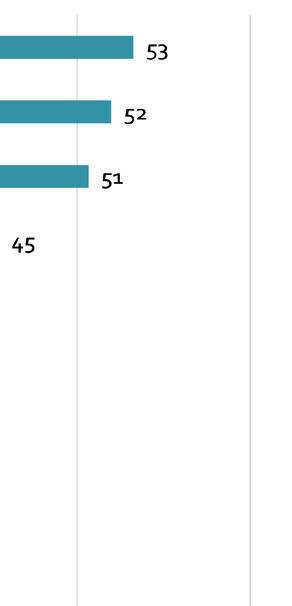

Figure 4 shows that policymakers in over 50% of jurisdictions are concerned with overcrowded curricula (53% of jurisdictions), a lack of assessment focus on creativity (52%), and a lack of teacher training or pedagogical resources (51%). Additionally, policymakers identify a lack of appropriate facilities, equipment and/or materials as challenging in 45% of jurisdictions, while in 32% of jurisdictions a reference is made to financial constraints more generally. Insufficient system-level guidelines, standards or learning progressions on developing creativity (43%) and a focus on preparing students for high stakes examinations (38%) are seen as problematic in about 4 in 10 jurisdictions. To a lesser extent, jurisdictions reported unclear evidence supporting the integration of creativity in education (26%) and a lack of political will or a high-level strategy focused on developing creativity (18%) as challenging.

Percentage of jurisdictions reporting the following challenges to integrate creative thinking in their education system, 2022

Note: For each type of perceived challenge, the reported share is based on the number of jurisdictions that selected that challenge as a response, over the total number of valid responses received on this question (N=77). Cases in which no response options were selected (i.e., ‘None / Not applicable’ was not selected, either) were treated as missing data and thus not counted as valid responses.

Source: OECD, PISA 2022 System-Level Questionnaire on Creative Thinking.

Clear definitions and concrete illustrations of the content and performances that students are expected to master are an important source of intelligence supporting education practitioners. Building on research-based learning progressions, system-level assessments can also constitute a reference point for educators to identify key aspects to focus on during instruction, and act as an important source of feedback informing teachers’ formative decisions based on insights on their students’ progress. The PISA 2022 System-Level Questionnaire inquired jurisdictions on whether formal guidelines (e.g. learning progressions, rubrics) or evaluations are provided in their education systems to facilitate a common understanding on what creative thinking is and expected student outcomes. Responses to the questionnaire show that only 24% of respondents reported the provision of such instruments at the level of the system, in contrast with a 66% of jurisdictions reporting their absence (Figure 5); 10% of respondents indicated that such tools are currently being developed in their jurisdiction.

Fostering creative thinking through education: Drivers, barriers and indicators of progress

Existence of system-level formal guidelines (e.g., learning progressions, rubrics) or evaluations of creativity, 2022

Are there any formal guidelines (e.g. learning progressions, rubrics) or evaluations used in your jurisdiction to assess students’ creativity?

Yes No Currently in development Missing information

Albania

Alberta (Canada)

Australian Capital Territory (Australia)

Austria

Baku (Azerbaijan)

Brazil

British Columbia (Canada)

Brunei Darussalam

Bulgaria

Cambodia

Chile

Colombia

Costa Rica

Croatia

Czech Republic

Denmark

Dominican Republic

El Salvador

England (United Kingdom)

Estonia

Faroe Islands (Denmark)

Finland

Flemish Community (Belgium)

France

French Community (Belgium)

French-speaking cantons (Switzerland)

German-speaking cantons (Switzerland)

German-speaking Community (Belgium)

Germany

Greece

Hong Kong (China)

Hungary

Iceland

Indonesia

Ireland

Israel

Italy

Jamaica

Japan

Jordan

Kazakhstan

Korea

Latvia

Lithuania

Macao (China)

Malaysia

Manitoba (Canada)

Mexico

Mongolia

Montenegro

Netherlands

New Brunswick (Canada)

New South Wales (Australia)

New Zealand

Newfoundland and Labrador (Canada)

North Macedonia

Northern Ireland (United Kingdom)

Northern Territory (Australia)

Norway

Nova Scotia (Canada)

Ontario (Canada)

Palestinian Authority

Panama

Paraguay

Peru

Philippines

Poland

Portugal

Prince Edward Island (Canada)

Qatar

Quebec (Canada)

Queensland (Australia)

Romania

Saskatchewan (Canada)

Scotland (United Kingdom)

Serbia

Singapore

Slovak Republic

Slovenia

Spain

Sweden

Chinese Taipei

Tasmania (Australia)

Thailand

Türkiye

Ukraine

Uruguay

Uzbekistan

Viet Nam

Wales (United Kingdom)

Notes: OECD countries are shown in bold black. Regions of OECD countries are shown in black italics. Partner countries and economies are shown in bold blue.

Jurisdictions are ranked in alphabetical order.

Source: OECD, PISA 2022 System-Level Questionnaire on Creative Thinking.

Pursuing the development of deep learning and high-order socio-cognitive competencies requires teachers with expert professional repertoires. Teacher education and training are an important means of knowledge and skill acquisition for professionals, contributing positively to their sense of preparedness for teaching, including the teaching of cross-curricular skills (OECD, 2019[43]). Hence, at the system level, a key question is whether qualification frameworks and professional standards incorporate the idea that nurturing students’ creativity is a constituent element of good teaching practice.

It must be noted that promoting learners’ creative thinking through teaching, which has been called teaching for creativity, and teaching creatively encompass different ideas. While the latter emphasises the creativity of teachers in their practice generally, the former refers to the use of teaching practices that explicitly cultivate the creativity of students (NACCCE, 1999[48]). The two are nonetheless connected in the sense that teaching for creativity depends on teachers orchestrating learning activities creatively (Paniagua and Istance, 2018[42]), but they should be understood separately and equally promoted.

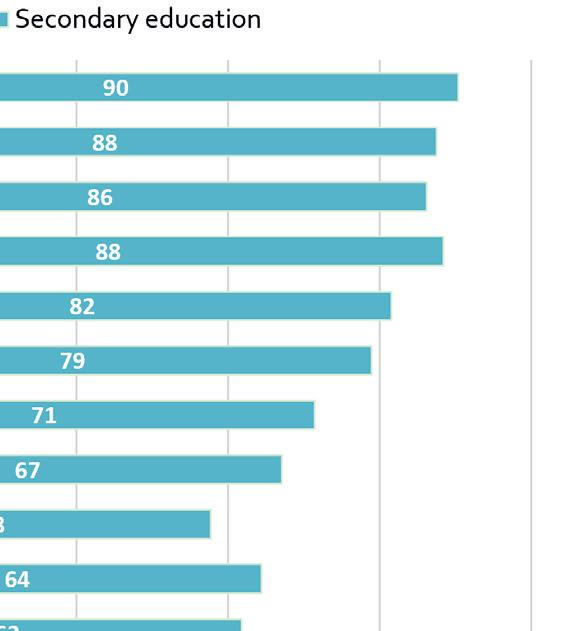

PISA asked participating jurisdictions whether system-level guidelines or requirements governing teacher formal education and training exist in their contexts, and whether they explicitly refer to 1) developing students’ cross-curricular/interdisciplinary skills, 2) developing students’ creativity specifically, and 3) teaching creatively or creative pedagogy more generally. As shown in Figure 6, guidelines/requirements for primary education teachers included general references to developing students’ cross-curricular/interdisciplinary skills in most jurisdictions (80%). To a lesser extent, they included references to developing students’ creativity specifically (68% of jurisdictions) and to teaching creatively or creative pedagogy (64%). Similar patterns were observed in requirements for secondary education teachers: 74% of jurisdictions reported the inclusion of references to teaching cross-curricular/interdisciplinary skills, 61% to developing students’ creativity and 61% on teaching creatively or creative pedagogy.

Clear guidance on assessment, especially when the use of complex tools is warranted, can help practitioners in designing creativity-supportive learning activities and proposing relevant evaluation criteria. In this sense, policymakers can promote the use of evaluation results to leverage the formative power of assessment. Different areas may be targeted towards this end, notably the development of practitioners’ capacity to assess against student learning objectives and the improvement of their knowledge and skills for formative assessment with a focus on creative thinking.

PISA asked policymakers whether teacher qualification and training requirements in their jurisdiction explicitly refer to assessing students’ creativity. As shown in Figure 7, among jurisdictions reporting the existence of such qualifications and training requirements and with data available, only 44% reported explicit references to assessing students’ creativity for practitioners in primary education and 40% for those teaching in secondary education.

Fostering creative thinking through education: Drivers, barriers and indicators of progress

Figure

Existence of system-level formal guidelines or requirements related to the content of initial teacher training referring to creativity, by type and level of education, 2022

Yes No

Not applicable

Missing information

Are any of the following elements explicitly referred to in your jurisdiction’s formal guidelines or requirements related to the contents of initial teacher training for…

Primary Education

Developing students' cross-curricular/ interdisciplinary skills in general

Developing students' creativity

Teaching creatively (creative pedagogy)

Albania

Austria

Brazil

Brunei Darussalam

Cambodia

Chile

Colombia

Croatia

Czech Republic

Denmark

Dominican Republic

El Salvador

England (United Kingdom)

Estonia

Faroe Islands (Denmark)

Finland

Flemish Community (Belgium)

France

French Community (Belgium)

German-speaking Community (Belgium)

Germany

Greece

Hungary

Iceland

Indonesia

Ireland

Israel

Italy

Jamaica

Japan

Jordan

Kazakhstan

Korea

Latvia

Macao (China)

Malaysia

Manitoba (Canada)

Secondary Education

Developing students' cross-curricular/ interdisciplinary skills in general

Developing students' creativity

Teaching creatively (creative pedagogy)

Figure 6 [2/2] Preparing teachers to teach for creativity

Existence of system-level formal guidelines or requirements related to the content of initial teacher training referring to creativity, by type and level of education, 2022

Are any of the following elements explicitly referred to in your jurisdiction’s formal guidelines or requirements related to the contents of initial teacher training for…

Primary Education

Developing students' cross-curricular/ interdisciplinary skills in general

Developing students' creativity

Teaching creatively (creative pedagogy)

Mexico

Mongolia

Montenegro

Netherlands

New Brunswick (Canada)

New South Wales (Australia)

New Zealand

Newfoundland and Labrador (Canada)

North Macedonia

Northern Ireland (United Kingdom)

Norway

Nova Scotia (Canada)

Ontario (Canada)

Palestinian Authority

Paraguay

Peru

Philippines

Poland

Portugal

Qatar

Quebec (Canada)

Romania

Scotland (United Kingdom)

Singapore

Spain

Chinese Taipei

Thailand

Türkiye

Ukraine

Uruguay

Viet Nam

Wales (United Kingdom)

Secondary Education

Developing students' cross-curricular/ interdisciplinary skills in general

Developing students' creativity

Teaching creatively (creative pedagogy)

Notes: OECD countries are shown in bold black. Regions of OECD countries are shown in black italics. Partner countries and economies are shown in bold blue.The table includes information on jurisdictions that reported the existence of guidelines/requirements for initial teacher training for primary and/or secondary education levels. Jurisdictions that reported that such guidelines do not exist or for which it is unclear whether such guidelines exist for both primary and secondary education levels, have been omitted from the table. Jurisdictions are ranked in alphabetical order.

Source: OECD, PISA 2022 System-Level Questionnaire on Creative Thinking.

Fostering creative thinking through education: Drivers, barriers and indicators of progress

Existence of system-level formal guidelines or requirements related to the content of initial teacher training referring to the assessment of students’ creativity, by level of education, 2022

Yes

Albania

Austria

Brazil

Brunei Darussalam

Cambodia

Chile

Colombia

Croatia

Czech Republic

Denmark

Dominican Republic

England (United Kingdom)

Estonia

Faroe Islands (Denmark)

Finland

Flemish Community (Belgium)

France

French Community (Belgium)

Germany

Greece

Hungary

Iceland

Indonesia

Israel

Italy

Jamaica

Japan

Jordan

Kazakhstan

Korea

Latvia

Macao (China)

Malaysia

Not

Primary Education Secondary Education

Manitoba (Canada)

Mexico

Mongolia

Netherlands

New Brunswick (Canada)

New South Wales (Australia)

New Zealand

Newfoundland and Labrador (Canada)

North Macedonia

Northern Ireland (United Kingdom)

Norway

Nova Scotia (Canada)

Ontario (Canada)

Palestinian Authority

Paraguay

Peru

Philippines

Poland

Portugal

Qatar

Quebec (Canada)

Romania

Scotland (United Kingdom)

Singapore

Spain

Chinese Taipei

Thailand

Türkiye

Ukraine

Uruguay

Viet Nam

Wales (United Kingdom)

Notes: OECD countries are shown in bold black. Regions of OECD countries are shown in black italics. Partner countries and economies are shown in bold blue.

The table indicates which jurisdictions reported that there are references to the assessment of creativity in the system-level guidelines or requirements for initial teacher training for primary and/or secondary education levels. Jurisdictions that reported that such guidelines/requirements do not exist or for which it is unclear whether such guidelines exist for both primary and secondary education levels, have been omitted from the table. Jurisdictions are ranked in alphabetical order.

Source: OECD, PISA 2022 System-Level Questionnaire on Creative Thinking.

Box 2 Has teacher education and training to teach for creativity evolved over time?

In 2018, the OECD’s Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) asked teachers about the content included in their formal education or training, providing insight on the inclusion of teaching cross-curricular skills (e.g. creativity, critical thinking and problem solving) in their preparation. Results show that teacher education and training for about 70% of teachers on average across TALIS 2018-participating jurisdictions included the teaching of cross-curricular skills, with provision ranging from over 90% in Chile, South Africa, United Arabs Emirates and Viet Nam to less than 50% in Austria, Czech Republic, France and Slovenia.

TALIS 2018 also offers a perspective on the evolution of teachers’ formal training and education content by comparing the reports of teachers who completed their formal education and training in the five years previous to the survey with those of the whole teacher population. Results show an increase in the percentage of teachers who reported the inclusion of teaching cross-curricular skills in their education and training in all jurisdictions with data available except for Denmark, where the percentage fell by 1%. In contrast, the largest variation was found in Czech Republic and France, with an increase in teacher reports of over 20%, followed by similar growth in Austria, the Flemish Community of Belgium and Spain (17%).

Results based on reports of lower secondary teachers, by year of education and training completion, 2018

Note: Jurisdictions are ranked in descending order of the percentage of lower secondary teachers for whom the teaching of cross-curricular skills was included in their formal education or training.

Source: TALIS 2018 database, Table I.4.13, https://www.oecd.org/education/talis/talis2018tables.htm

Continuous learning beyond initial education and training contributes to building teachers’ know-how and confidence to teach for creativity. Teacher training can help elicit teachers’ prior conceptions of creativity, provide concrete frameworks of creative thinking across domains and a clear picture of the outcomes to be expected of students, and address typical misconceptions, such as views of creative thinking as a competency related only to the arts and confusions between ‘teaching for creativity’ and ‘teaching creatively’. Additionally, the provision of teaching guidelines and examples, such as rubrics and lesson plans, can act as a source of inspiration for teachers seeking for new models to adapt and incorporate in their practice (Vincent-Lancrin et al., 2019[23]).

To understand how different jurisdictions seek to build capacity for educators and schools to teach for creativity, PISA asked policymakers whether the following support mechanisms are available in their jurisdictions:

1) professional development for teachers on developing students’ creativity; 2) professional development for teachers on creative pedagogy; 3) teaching resources on creative pedagogies or lesson plans (e.g. online portals); 4) funding/scholarship for teachers to participate in creativity-related activities or research; 5) funding to run creative programmes or projects; 6) funding for creative materials, equipment and/or facilities (e.g. art studios, makerspaces, performance spaces); and 7) organised visits to/from creative practitioners (e.g. designers, poets, performers, engineers).

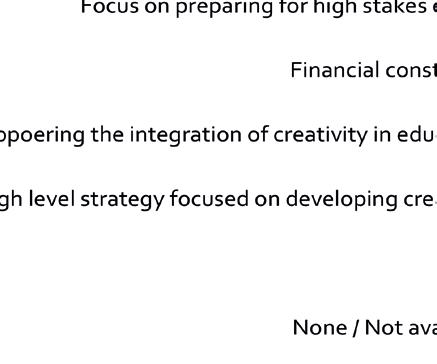

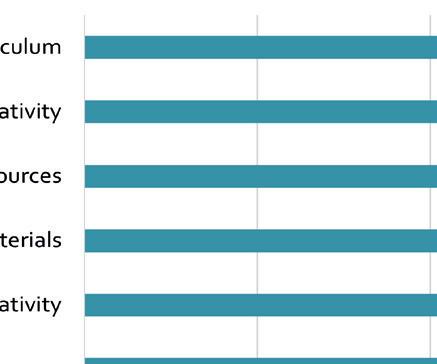

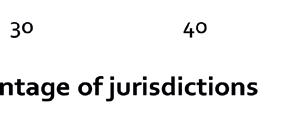

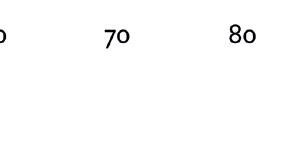

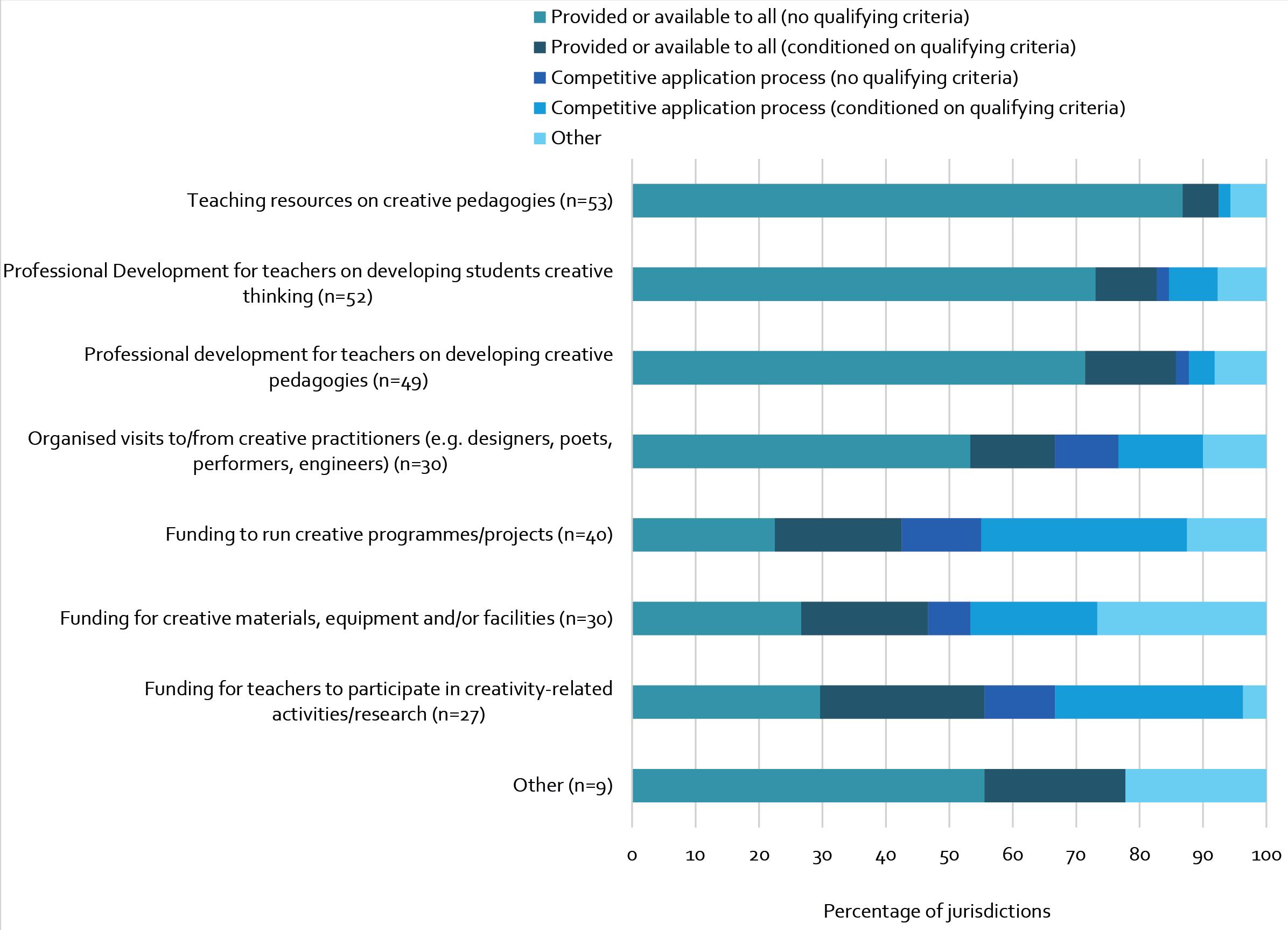

Survey responses (Figure 9) show that 69% of jurisdictions responding to this question in the survey provided teachers with teaching resources, and 67% and 64% of jurisdictions offered professional development opportunities for teachers on developing students creative thinking and developing creative pedagogies, respectively. A lower number of policymakers flagged system-level mechanisms to promote the collaboration between school staff and creative practitioners outside education (42%) and the availability of funding for creativity-related activities/research (39%), despite the role that action research and cross-sectoral collaboration can play in supporting knowledge creation and mobilisation (Davies et al., 2014[33]; Révai, 2020[49]). System-level supports in some jurisdictions also included the provision of funding for creative programmes or projects (54% of jurisdictions), such as curricular and extracurricular courses supporting creativity, and funding for creative materials, equipment or facilities (45%), like art studios and makerspaces. Other forms of support were reported in 13% of jurisdiction. Policymakers in about 1 in 10 jurisdictions responded that no support is available (12%).

PISA also asked jurisdictions about the conditions with which support for schools and teachers is made available to their target beneficiaries. For each of the support mechanisms covered in Figure 9, the PISA questionnaire asked policymakers if they were 1) provided or available to all with no qualifying criteria; 2) provided or available to all conditioned on qualifying criteria; 3) available through a competitive application process with no qualifying criteria; 4) available through a competitive application process conditioned on qualifying criteria; or 5) other.

System-level

Professional development opportunities are mostly offered to all teachers, while funding for projects and infrastructure is more commonly targeted and/or competitive

Percentage of jurisdictions reporting the availability of the following system-level support mechanisms for schools and teachers to promote creative thinking, 2022

Note: For each support type, the percentage is based on the number of jurisdictions that indicated providing that support type, over the total number of valid responses received on this question (N=84). Cases in which no response options were selected (i.e. no response including ‘No Support Available’ was selected) were not counted as valid responses.

Source: OECD, PISA 2022 System-Level Questionnaire on Creative Thinking.

Survey results (Figure 10) show that many jurisdictions make teaching resources (87% of jurisdictions) and professional development for developing students’ creative thinking (73%) and creative pedagogies (71%) available for all teachers and schools with no conditionality. Arguably, an open offer with no conditionality is a policy decision seeking to promote access and encourage participation, although it must be noted that low engagement is seldomly linked to a lack of prerequisites. Results from TALIS 2018 pointed to other, more significant barriers, including time conflicts between training and work schedules, a lack of incentives for participation, training being too expensive or not relevant, difficulties to conciliate training with family responsibilities and a lack of employer support (OECD, 2019[43]).

In contrast, provision of funding for participation in creativity-related activities and research (30%), materials, equipment and/or facilities (27%), and creative programmes or projects (23%) is commonly more restricted. In such cases, education authorities may seek to optimise limited resources and maximise impact – for instance by requiring beneficiaries to present a project plan and demonstrate their technical capacity to implement it, or by defining co-financing rules to incentivise the commitment of participants to the success of their initiatives. There is greater diversity in the way jurisdictions promote cross-sectoral collaboration through organised visits. Such form of support is available to all with no qualifying criteria in about half of the jurisdictions responding to this question in the survey (53%).

Scope of provision and degree of conditionality of system-level supports for schools and teachers, 2022

Note: For each type of support, the bar chart shows the relative frequency of each of four conditions to access. The number of valid responses for each support in shown in parenthesis. Cases in which the support type was indicated but no information was provided on conditions of access were not considered as valid responses.

Source: OECD, PISA 2022 System-Level Questionnaire on Creative Thinking.

Integrating creativity in education: What are we talking about, why should we care and how do we go about it?

Considering the challenges to integrating creative thinking in school systems previously discussed, this section identifies key pointers to develop comprehensive policies supporting the implementation of creativity-conducive curricula. These pointers have been identified by grouping existing practices that were reported by jurisdictions participating in the PISA 2022 System-Level Questionnaire on Creative Thinking

The incorporation of creative thinking in curricula internationally illustrates the efforts of education jurisdictions to adapt schooling to changing social demands. However, introducing changes in curricula, arduous as it may be, risks failing to generate the intended outcomes if learning goals are not clear. Setting the basis for creative thinking to be promoted consistently and effectively across schools and for all students requires generating a shared understanding on the nature of creative thinking among curriculum developers and educators. Defining curricular terms with precision and providing clear guidance and examples can facilitate the development of creativity-supportive teaching and learning in practice.

Several jurisdictions have developed guiding materials and examples to help teachers understand the types of outcomes that ought to be expected of students and the learning trajectories they typically follow to reaching them. In Canada, for instance, the province of Alberta provides teachers with competency progressions and descriptors of learning outcomes across grades, ages and achievement levels for ‘creativity and innovation’ on its new LearnAlberta platform. In Ontario, similar orientations are offered in the system-level guidelines on assessment, evaluation and reporting for schools. Manitoba is also in the process of developing such guidelines.

In Finland, assessment criteria within the National Core Curriculum for Basic Education are linked to the transversal competence goals, and subject-specific assessment criteria contain references to the assessment of creativity and creative thinking where applicable. The guidelines in the National Core Curriculum offer a baseline orientation for further curricular development locally. Similarly, in Japan, where creativity is particularly emphasised in the context of technology-related subjects, national assessment guidelines refer to creativity and include exemplars for its evaluation for “Art and Handicraft” in elementary schools and for “Art” and “Technology and Home Economics” in middle schools. In Scotland (United Kingdom), teaching and assessment approaches and expected outcomes for creative thinking are provided through the Curriculum for Excellence Benchmarks

Insufficient time for students to engage in the practice of creative thinking and for educators to collaboratively develop new pedagogical approaches and educational resources can be the result of curriculum overload, occurring when new content is added to the curriculum without proper consideration of the content already existing. Education jurisdictions internationally are adopting different strategies in response to this challenge. For instance, some jurisdictions have focused on determining essential content when defining the “exit profile” of students leaving compulsory education or by identifying the “big ideas” curricula should cover to avoid an excessive number of subjects or topics and provide clear priorities for curricular development locally (see OECD (2020[50]) for a detailed discussion and examples).

A complimentary strategy to optimise instruction time and content coverage emphasises connections across knowledge domains (i.e. interdisciplinarity). In interdisciplinary learning, the content and skills that learners practice are defined by the questions or themes that they work on rather than by a strict separation of disciplines or subjects. Greater interdisciplinarity allows for the articulation of pedagogy around more contextualised,

authentic problems, providing opportunities for less fragmented and more meaningful learning experiences for students while increasing educators’ professional learning and accountability through collaborative planning and joint teaching (OECD, 2013[45]).

Several examples of integrative approaches were reported in the PISA questionnaire, notably in relation to the benefits of engaging students in manual work and self-expression. Active creation is a form of learning because people develop knowledge by tinkering and making and by experimenting with tangible tools, such as in play. Similarly, activities based on the primacy of self-expression and aesthetics foster student motivation, and personal experiences can be leveraged to foster the development of academic knowledge beyond arts subjects (Paniagua and Istance, 2018[42]).

The Ministry of Education and Research in Norway, recognising the link between creation and expression and the promotion of learning in all subjects, published the strategy “Creative joy, commitment and a desire to explore: Practical and aesthetic content in kindergarten, school and teacher training” in 2019 (Skaperglede, engasjement og utforskertrang: Praktisk og estetisk innhold i barnehage, skole og lærerutdanning). The goals of the strategy included reducing the scope of curricular subjects to facilitate deeper learning, strengthening the practical and aesthetic aspects in the curriculum, and developing new assessment guidelines to support teacher practice. Following the publication of the strategy, a new national curriculum was introduced in 2020, which incorporates accompanying resources for teaching and learning in the practical-aesthetic subjects. Along similar lines, the “Political Agreement about Strengthened Practical Expertise” (2018) in Denmark stressed that pupils should have more opportunities to develop imaginative and creative skills in primary and lower secondary school and to be able to translate methods and theories to concrete products. Among other aspects, selective practical/musical subjects have been made compulsory and must be completed with an exam. A focus on practical learning is also visible in Singapore. The Applied Learning Programme emphasises application of thinking skills and the integration of knowledge across subject disciplines. It provides opportunities for students to develop creative thinking as they generate relatively novel and appropriate ideas or products in authentic settings across society and industry. Similarly, the Learning for Life Programme provides opportunities for students to creatively design activities and programmes for the benefit of their communities.

Examples from other jurisdictions have a specific focus on the link between STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) and aesthetic education – the so-called STEAM approach, where the “A” stands for the arts. In Ireland, various initiatives targeting design, creativity and innovation are underway. For instance, “Science Blast” is an initiative in partnership with a range of organisations that aims to encourage students to think, create, design, explore and learn new skills by asking entire primary school classrooms to investigate a question they are curious about and present their findings to a STEM judge, (móltóir), who provides them with constructive feedback.’ In Korea, STEAM education is a project led by the Korea Foundation for the Advancement of Science and Creativity, a quasi-governmental organisation in charge of science and ICT, and it aims at fostering creative technical talents in elementary and middle schools. The project involves a focus on teacher training, support to research initiatives and to the development and operation of STEAM school and out-of-school programmes. Studies of the programme have found positive effects in terms of both teacher professional development and student learning outcomes, but also a number of challenges for teachers, including insufficient time to implement it, higher workloads, and a lack of administrative and financial support (Kang, 2019[51]; Park et al., 2016[52]).

Successful integration of learning content through interdisciplinarity can indeed be hard to achieve. Students may experience difficulties in integrating key ideas and methods when working across disciplines, and teachers may lack familiarity with the content and standards of the subjects that they do not commonly teach. Additionally, organisational aspects must be considered, such as school arrangements articulated around strong disciplinary divisions (e.g. timetables), and the professional isolation that many teachers experience in their daily practice. Importantly, educators need access to actionable models that guide them

in the orchestration of interdisciplinary teaching and learning activities (Shernoff et al., 2017[53]). Further support may be provided by emerging technologies that, like generative artificial intelligence, hold increasing potential to aid lesson planning and instruction (Mollick and Mollick, 2022[54]).

As visible in the results of the PISA 2022 questionnaire, policymakers can support schools and teachers to reflect on and experiment with new practices in different ways. One type of system-level support includes the provision of training and teaching resources for educators to teach for creativity. In Scotland (United Kingdom), for instance, Education Scotland has provided teachers with a National Improvement Hub. The Hub includes several learning resources, articles, impact reports, self-evaluation tools and exemplars of practice for improving teaching and learning, some of which relate to creativity and creative thinking. For instance, practitioners are given access to a “Creativity Toolbox” (2018), which contains 13 short films on creative approaches to support planning and improvement, and to the “Planning for and Evaluating Creativity ZIP file” (2017), which contains several open access resources, such as the “Creative Learning Survey for Pupils”, the “Creative Teaching & Learning Graphic Equaliser”, and a “Creativity Evaluation Checklist” and “Creativity Planning Checklist”. The Creativity Portal, developed in partnership between Education Scotland and Creative Scotland, offers additional support in the form of “a one-stop shop to help teachers, community learning leaders, and educators find high quality creative partnerships, case studies of good practice, the latest creativity research, online teaching resources, local creative learning contacts”. Other examples of support in the form of teaching guidelines and materials across PISA 2022-participating jurisdictions include the Moodle platform developed in the Republic of North Macedonia in 2018, which comprises four courses on developing critical thinking, creative problem solving and programming skills, and the Handbook of Creativity: Development and Practice in Teaching and Learning (2011), in Malaysia, a reference point for educators to plan teaching and learning activities.