Bridging the Gap: Frontier Technologies and the Diffusion Dilemma

This document provides a summary of the TIP event “Bridging the Gap: Frontier Technologies and the Diffusion Dilemma,” which took place on 18 June 2025 at the OECD headquarters in Paris. It opens with an introduction that provides the context and objectives of the event, followed by a section highlighting the key takeaways from the discussions, focusing on frontier technologies (FTs), diffusion challenges, and their policy implications. The next section outlines implications for the OECD’s TIP policy agenda A comprehensive summary of the event sessions is then provided, covering strategic decision-making in advancing FTs, technology diffusion, regional capabilities and investment strategies, interactive policy practice sessions, and complementarities and trade-offs in the STI policy mix.

SUMMARY

Introduction to the event

On 18 June 2025, the OECD Working Party on Innovation and Technology Policy (TIP) organised the event “Bridging the gap: Frontier technologies and the diffusion dilemma” at the OECD headquarters in Paris

The event explored how science, technology, and innovation (STI) systems can strike a balance between fostering cutting-edge technological advancements and ensuring their inclusive and broad-based diffusion. Through a mix of panel discussions, interactive sessions, and poster presentations, participants explored key trade-offs faced by policymakers (e.g. promoting excellence vs fostering inclusion) and learned from concrete country-level experiences and policy examples (e.g. strategic initiatives in the field of green hydrogen and renewable energies). Discussions also revolved around issues of economic complexity, regional capabilities, and the role of institutions in sustaining both innovation leadership and broad-based technology diffusion.

The event gathered 115 participants from 32 countries from across the OECD. Attendees comprised of country delegates and experts from ministries in charge of research and innovation and national innovation agencies, such as Sweden’s Vinnova, the Austrian Federal Ministry of Women, Science and Research and the UK’s Department for Science, Innovation and Technology; project managers in charge of frontier technology policy initiatives, for instance from Korea’s Innopolis, Germany’s Fraunhofer Institution for Energy Infrastructures and Geotechnologies and the UK’s Digital Catapult and Offshore Renewable Energy Catapult, as well as innovation experts from different universities, research centres and thank tanks, such as the University of London, the Centre for European Policy Studies, the Royal Swedish Academy of Engineering Sciences, the VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland and the SGH Warsaw School of Economics Representatives from Business at OECD (BIAC) and the Trade Union Advisory Committee to the OECD (TUAC) also participated.

In a context of geopolitical volatility and accelerating technological change, governments are grappling with how to best allocate limited public resources to support leadership in frontier technologies (FTs) like quantum computing, AI, renewable energy, and advanced manufacturing. This push for innovation comes as societies continue to face unresolved challenges from past industrial transitions, such as uneven deindustrialisation and digital divides. As demands on STI systems grow, policymakers must balance advancing technological frontiers with addressing issues of inclusion, productivity, and equitable growth. Key dilemmas arise around whether to concentrate resources in regions and sectors with existing strengths or distribute support more widely to foster broader participation and long-term resilience.

The event builds on the OECD TIP event that took place in December 2024, which focused on exploring challenges in the context of green FTs. Participants discussed how competitiveness and cooperation shape technology choices, noting that scale, private investment, and demand-side factors are critical to success. The event highlighted trade-offs between concentrating efforts for faster breakthroughs and promoting broader industrial and regional participation to ensure diffusion and sustainability. Through discussions of cluster policies, cross-border cooperation, and balanced policy mixes, the event identified actionable strategies to support both excellence and inclusiveness in STI systems navigating FT development

OECD-TIP EVENT – PARIS, 18 JUNE 2025

Key issues from the event

This section introduces some of the most interesting and pressing questions that were raised throughout the June 2025 TIP event, such as how to take into consideration current and future capacities when designing strategic technology policies, how to leverage localised capacities for national technology objectives, or how to balance diffusion and development in STI policy portfolios in a context of strategic technology imperatives These issues are important elements of the international and national STI policy communities in the years ahead.

1. Tailoring frontier technology (FT) strategies to national strengths and contexts

For most countries, deciding which technologies to support is seen as a strategic imperative that defines their future relevance and prosperity. A central reflection that emerged from the event concerned how countries should best balance their existing capacities with the strategic ambition needed to achieve meaningful progress in FTs. Participants discussed to what extent national STI strategies should build on current competencies – like skilled engineering talent or existing regional infrastructure – and when it is necessary to reach beyond, either by investing substantially more at home or by forging deeper international partnerships.

This issue is especially salient for smaller (and emerging) economies or those with specific pockets of expertise. For example, a country may possess outstanding engineers and academic research in an emerging field such as quantum, but face limitations in internalising or attracting the capital required to scale innovations or sustain late-stage technology development. In such contexts, policymakers grapple with whether to focus support on a narrow set of feasible sectors, to prioritise international collaboration for access to markets and resources, or – if the ambition is to move into new domains entirely – to acknowledge the external dependencies this will entail over the long term.

The issue of FTs also potentially requires moving out of “comfort zones”. Korea’s investment in the semiconductor sector in the 1980s exemplifies a high-risk, high-return “moonshot” that moved beyond the country’s existing capabilities. With limited experience, infrastructure, and ecosystem readiness, the government nonetheless committed to sustained public funding, institutional coordination, and long-term capability-building. This initial leap helped establish core capacities in advanced electronics, creating a foundation that later enabled more structured and aligned approaches. Today, initiatives such as Innopolis, led by the Korean Innovation Foundation, reflect this evolution by fostering collaboration between research and industry and aligning national priorities with regional capabilities to promote the adoption of FTs Moreover, local strengths – whether natural, such as Sweden’s renewable resources, or the those that are the result of policy decisions, such Korea’s evolving semiconductor and research ecosystems – offer starting points, but global competition and rapid technological change mean that even strong initial positions require sustained investment, coordinated governance, and often cross-border co-operation to remain relevant and beneficial to the domestic economy. Material availability and capital needs add an additional layer of complexity: some industries demand resources that can only be secured through international agreements or supply chains, even as nations seek to capture as much value as possible within their own ecosystems.

In light of these dynamics, the question that faces STI policymakers is not only “Where are our strengths?” but also “How far, and with whom, can we realistically travel in a given technology area, and how should strategic ambition be calibrated in relation to both domestic capacities and the inescapable realities of global technological interdependence?” These policy dilemmas, highlighted throughout the event, are likely to shape national and international STI strategies for years to come.

SUMMARY OF DISCUSSIONS

2. Balancing flexibility with policy stability for FT development

In rapidly changing sectors, policy frameworks must strike a balance: remaining flexible and responsive yet providing enough certainty and coherence to guide investments and reduce transition risks, even when contentious decisions – like the phaseout of combustion engines – are on the table. Embedding flexibility and a culture of learning is particularly vital for general-purpose technologies, such as artificial intelligence or quantum computing, whose economic and societal impacts unfold unpredictably over time. Finland’s early investment in classical computing, while not commercially transformative at the time, built foundational skills and infrastructure that ultimately underpinned its leadership in ICT.

At the same time, sustained commitment and policy stability are essential for mobilising private investment and enabling the infrastructure required for widespread technology diffusion. Where policy signals are inconsistent – such as uncertainty regarding the future of electric vehicles – manufacturers and suppliers may hesitate to invest, inhibiting the large-scale transitions needed for societal benefit.

However, an important policy and strategic challenge remains: public investment is finite, and efforts to “cover all bases” by spreading resources thinly across too many fronts often dilute impact. Strategic policy must balance ambition with realism, focusing support on sectors or domains where national strengths and the plausible scale of investment can genuinely move the needle, both domestically and internationally. This requires robust, forward-looking assessments that weigh internal capabilities and the external competitive landscape, and must be grounded in dialogue with industry and research rather than purely technocratic decision-making

3. A strong foundation of transferable skills reduces vulnerability when navigating unpredictable FTs

Since the long-term success of specific technologies is unclear, policy support should not only advance technological frontiers but also focus FT support on investing broadly in capacities and capabilities relevant for the future. Strengthening the general supply of high-quality engineers, scientists, and problem-solvers ensures flexibility: even if, for instance, it is not hydrogen but batteries – or neither – that power the next generation of vehicles, or a computing revolution comes from an unexpected source, the workforce remains prepared to seize new opportunities. The same applies to a wider set of research infrastructures.

Finland’s experience illustrates this approach. The decline of Nokia’s mobile phone business in the 2010s disrupted jobs and the economy, but the skills, engineering expertise, and innovation infrastructure developed during Nokia’s rise allowed Finland to pivot into new domains like quantum technologies, AI, and green innovation.

4. Leveraging regional ecosystems to drive national FT strategies

Regional innovation ecosystems can be instrumental in advancing FT ambitions at a national level, as research and engineering capacities for pushing technological boundaries may be found outside traditional innovation hubs or recognised clusters of excellence. Harnessing these regional strengths is not merely about fostering geographic or social inclusion, under the right conditions, it can be critical to technological success; see, for example, the June 2025 decision by the United Kingdom to allocate GBP 750 million in funding for a supercomputer at Edinburgh University (which while not being a lagging region nevertheless represents a national-level strategic choice to develop supercomputing capacities outside the South East of England)

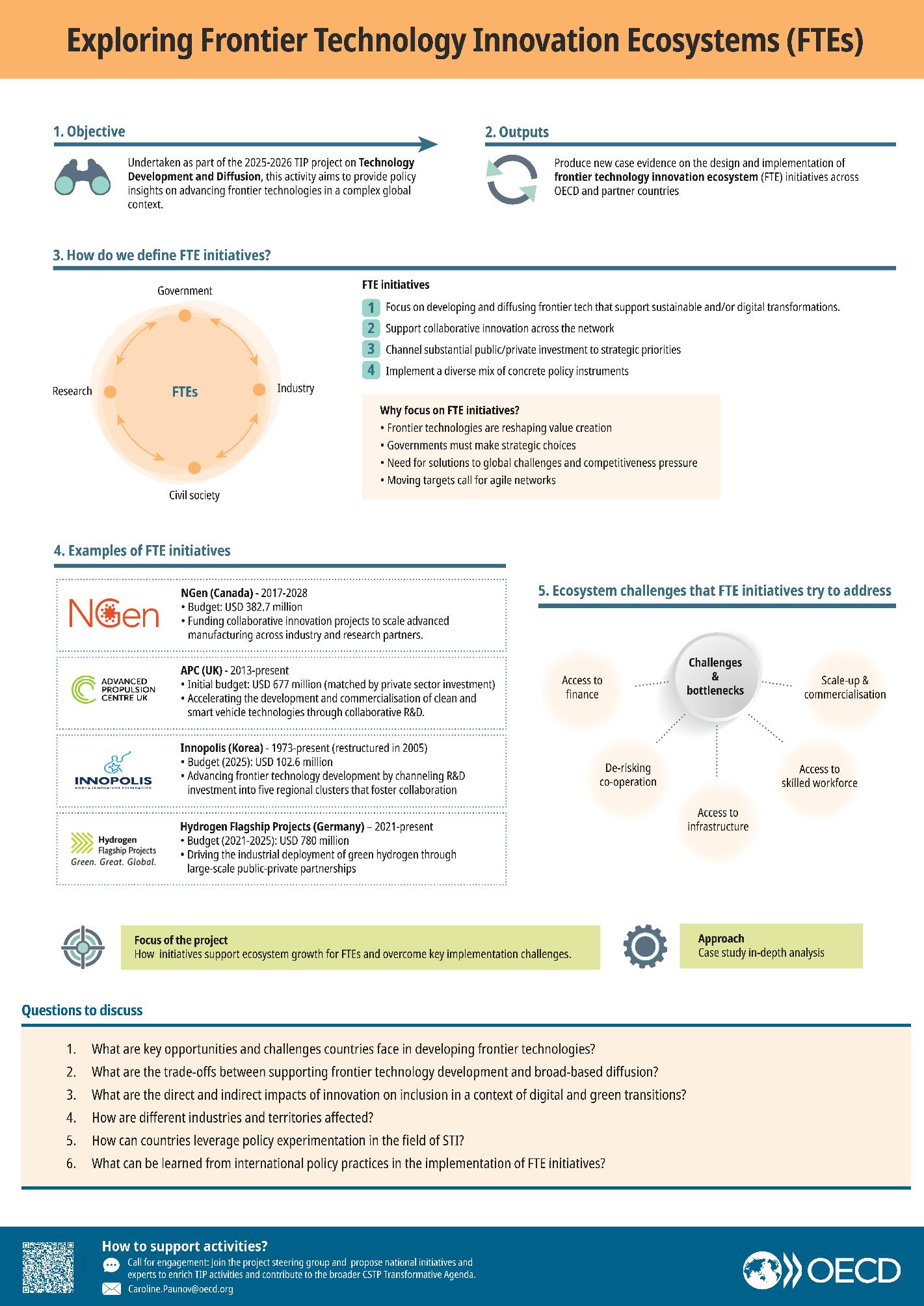

Frontier technologies ecosystem initiatives – FTE initiatives – focus on FTs that drive sustainable and digital transformation, align with strategic priorities backed by significant public and private investment, mobilise co-creation through collaborative policies, and implement a comprehensive mix of concrete policy instruments from R&D funding to demand-side tools – as pushing the frontier requires a collective effort

EVENT – PARIS, 18 JUNE 2025

involving government, research and industry. Regional clusters that bring together leading institutions and a qualified workforce are often effective breeding grounds for pushing the technology frontier.

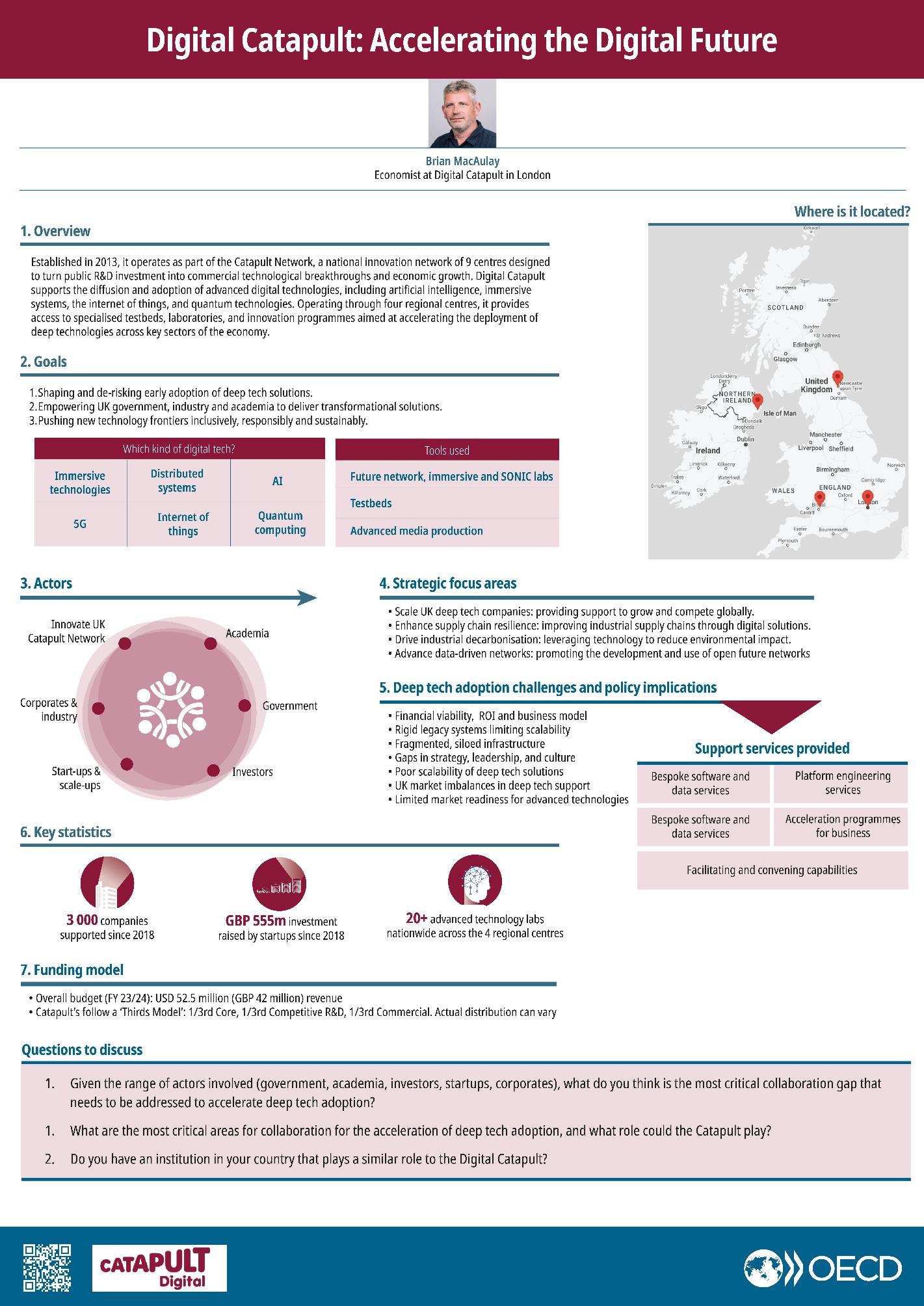

An example of an FTE initiative that fosters coordination between different regional stakeholders is the UK’s Catapult network. Each of the nine Catapult centres focuses on a key technology area - such as digital technologies and offshore renewable energy – and acts as a hub that connects industry, start-ups and scale-ups, academia, investors and government. The centres provide translational research support with place-based interventions Catapults aim to do so by i) providing dedicated physical and digital spaces where collaborative applied research and technology demonstration activities take place, ii) offering access to cutting-edge equipment and expertise, iii) supporting skills development through the provision of training programmes and workforce foresight activities to uncover current and future industry needs, and iv) helping bridge the gap between early-stage research and market-ready solutions by de-risking innovation, offering testbeds and acting as neutral convenors between academia, business and government

Another FTE initiative is Innopolis in Korea, that supports collaboration between research institutions and industry on FT development and diffusion in five regional clusters. To give an example, the Daedeok cluster focuses on levering research and industry capacities in the regions to further support the biotechnology and semiconductor sectors, including by looking to support the formation of spin-offs and public-private research partnerships.

5. Navigating regional, national, and transnational policy ambitions and realities for FT development

One of the hardest challenges in shaping FT strategies is reconciling multiple, often competing, layers of political and economic realities, each evolving in parallel and interacting dynamically.

At the trans-national and international levels, countries acknowledge both competitive pressures and opportunities for partnership, especially in strategic technologies where national ambitions must be measured against the large scale of global investment and competitiveness.

At the national level, the focus shifts to leveraging collective capacities of the STI system, which involves difficult choices on where to allocate finite resources spatially and technologically and the implications for those sectors and technologies left out.

At the subnational level, bottom-up aspirations for regional development and diffusion need to be balanced with national priorities and capacity. This requires a critical understanding of how regional initiatives can strengthen national objectives while still promoting inclusion.

Successful FT development consequently depends on the interplay and alignment of these regional, national, and international forces Trust building and co-operation at the regional level; clear strategy and coordination nationally; and leveraging international partnerships and agreements to access resources and markets. Persistent fragmentation – be it geographic, institutional, or policy-driven – remains one of the greatest obstacles to realising strategic visions in practice.

The road to achieving such coordination is difficult, as illustrated by the challenges faced by the EU in the field of AI Pierre-Alexandre Ballard highlighted during an OECD-TIP moonshot webinar “Leading the AI revolution: global dynamics & Europe's path to leadership’’ – based on the report “Forge ahead or fall behind: Why we need a United Europe of AI” and EU-ESIR group report “A European model for artificial intelligence” He argued that Europe lags behind in the field of AI due to insufficient connectivity between these hubs and a failure to mobilize coordinated investment, policy instruments, and strategic linkages across Europe. These constraints, he argued, were too substantive for the available talent or technological capability – many European innovation hubs demonstrate scientific excellence – to affect Europe’s possibilities for leadership.

SUMMARY OF DISCUSSIONS

6. Reconciling FT development and diffusion

Strategic investments in FT development and policies that foster widespread diffusion need not be seen as mutually exclusive or in opposition. While resource allocation for advanced R&D and demonstration projects may, at times, be concentrated to deliver breakthroughs, these investments only realise their full societal and economic value if accompanied by robust diffusion and adoption measures.

A recurring theme is that innovations emerging from a select group of leading firms or world-class research centres can remain fragile or isolated without broader market and societal uptake. Without effective diffusion – through enabling infrastructure, targeted incentives, skills development, and regulatory frameworks – early technological advances risk stalling, limiting their impact to just a small set of actors or sectors while bottlenecks in market growth and feedback loops persist.

International experience from sectors like clean energy shows the importance of complementing initial strategic investments with policies to accelerate broad diffusion. The impact of pioneering work in solar and wind, or the integration of artificial intelligence, has scaled when public policy has emphasised not just innovation at the frontier but also support for adoption and adaptation across the wider economy. Thus, the returns to breakthrough investment are maximised where there is a continuous and coordinated focus on both the development of new technologies and their integration into diverse regional, sectoral, and societal contexts.

Next steps for the activities of the OECD Working Party for Innovation and Technology Policy

Reflections on these issues will continue to inform TIP’s activities in 2025-26 on technology diffusion and development. The event highlighted the diverse challenges involved in supporting FT development, with diffusion playing often an important complementary role. It provided a structured space for dialogue among policymakers, researchers, and experts, helping countries learn from each other’s experiences in areas such as innovation governance, emerging technologies, and research systems.

These key themes will inform TIP’s activities in 2025-26 on technology diffusion and development. This will include work aimed at exploring frontier technology innovation ecosystems (FTEs) and policies supporting them (see more details in

OECD-TIP EVENT – PARIS, 18 JUNE 2025

). Related events planned for 2025 are outlined next. The latest information about TIP activities can be found on the TIP’s webpage.

A joint follow-up event of the Committee for Scientific and Technology Policy (CSTP) and the TIP on “Pushing Boundaries: Experimenting with Policy for Frontier Tech” will be held on 1 December 2025, back-to-back with the TIP meeting of 2-3 December 2025 Additional discussions will be organised as pat of the TIP’s moonshot webinar series.

Relevant OECD-TIP links on ongoing activities are the following:

• TIP website: https://oe.cd/tipone

• TIP “Technology development and diffusion” Project activities for 2025-26 – TIP brochure

• CSTP-TIP December 2025 event – latest agenda

• Moonshot webinar series – event website

SUMMARY OF DISCUSSIONS

OECD-TIP EVENT – PARIS, 18 JUNE 2025

Detailed summary

Introductory remarks

The Chair of TIP, Tiago Santos Pereira, opened the event and introduced the central question guiding the discussions: how to strike the right balance between pursuing technological leadership in strategic frontier technologies (FTs) and supporting broad-based innovation across firms, sectors, and regions. He emphasised that this question is relevant for all OECD countries, as several large-scale initiatives in areas such as quantum technologies, artificial intelligence (AI), advanced batteries, and green technologies are currently reshaping innovation landscapes

The Chair highlighted Portugal’s strategic decision to focus on wind energy and other renewable technologies as an example of national prioritisation. He also emphasised the relevance of the event to the TIP’s focus on ensuring innovation is inclusive, and its complementarity with the TIP event “Competitiveness and Co-operation Imperatives of Green Innovation”, held in December 2024

Jerry Sheehan, Director for Science, Technology and Innovation at the OECD, welcomed delegates and participants, underlining the importance of bringing together a diversity of perspectives to address the complex challenges associated with FT development and their diffusion. He stressed that leadership in these technologies had become a strategic imperative in a rapidly changing geopolitical environment and amid intensifying global competition. The event, he noted, provided a timely opportunity to draw lessons from real world examples and national experiences.

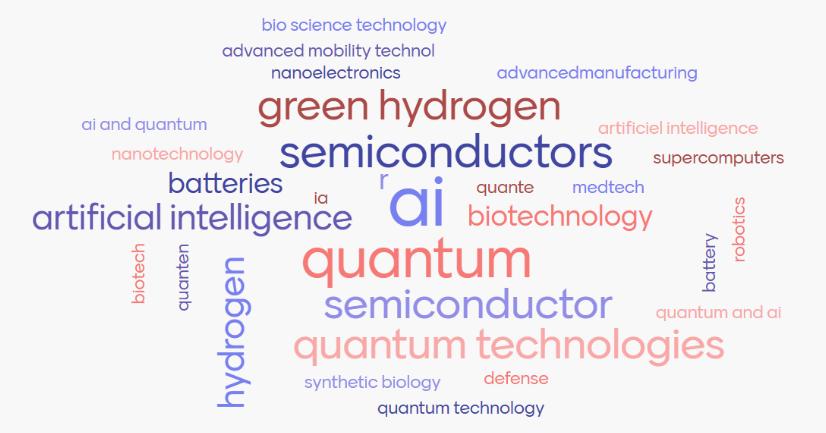

Caroline Paunov, Head of the OECD-TIP Secretariat, provided an overview of the event agenda and context. She then invited participants to respond to a quick online poll to identify priority technologies in their national STI agendas. The most frequently cited were artificial intelligence (AI), semiconductors, quantum technologies, green hydrogen and batteries. In a second poll, delegates were asked whether current STI policies were too focused on the technological frontier at the expense of focusing on diffusion. A majority agreed with that statement.

Figure 1. “What are the key technologies that your country is prioritizing?”

Word cloud of poll responses

SUMMARY OF DISCUSSIONS

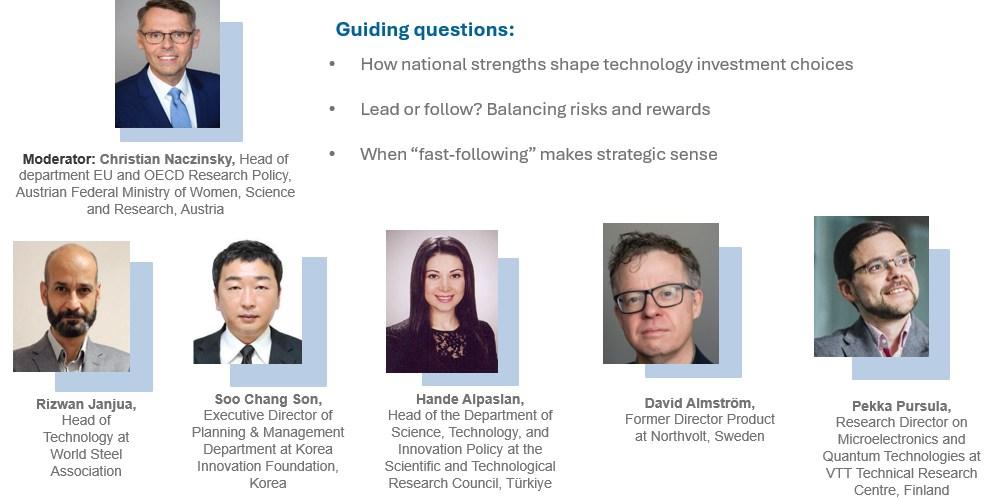

Session 1. Strategic choices in advancing frontier technologies

The first session, which was moderated by Christian Naczinsky, Head of the Department of EU and OECD Research Policy of the Austrian Federal Ministry of Women, Science and Research, explored the strategic decisions necessary to advance FTs and the conditions under which different policy approaches are most effective (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Speakers and guiding questions for session 1

Hande Alpaslan, Director of STI Policies, Scientific and Technological Research Council of Türkiye and Co-Chair of the OECD-TIP, emphasised that policymakers should be strategic, dynamic and selective when investing in FTs and pointed to the following critical dimensions for policy:

• Align investments with national capabilities and advantages – including economic competencies, scientific infrastructure, human capital, and the industrial base.

• Evaluate market opportunities in a shifting international context – and continuously reassess national capabilities and comparative advantages as conditions evolve.

• Prioritise technologies through inclusive, well-governed processes – involving entrepreneurial discovery, strong stakeholder collaboration, and continuous monitoring of emerging opportunities.

• Adopt effective fast-follower strategies – supported by strong absorptive capacity: a skilled workforce, institutions connected to global knowledge flows, and firms able to adopt advanced technologies.

Soo Chang Son, Executive Director of Planning and Management at the Korea Innovation Foundation, presented Innopolis. This government-led FTE initiative leverages public investment in R&D to drive technological advancement and commercialisation. Operating through five major clusters across the country, Innopolis brings together local universities, public research institutes, and technology-based companies The initiative seeks to align top-down national priorities, such as national security, with bottomup regional capabilities, thereby fostering the local adoption of FTs Instruments used include R&D subsidies, venture capital, policy support, and tax incentives to mitigate the uncertainties surrounding emerging technologies More information is provided in Figure (shown below) on the initiative

OECD-TIP EVENT – PARIS, 18 JUNE 2025

Rizwan Janjua, Head of Technology at the World Steel Association, highlighted the unique challenges the steel industry faces in its decarbonisation journey. He noted that while the industry played an important role in the global economy, with 1.8 billion tons of steel consumed globally each year including manufacturers, thin profit margins provided the industry with only limited funds for investments According to Mr. Janjua, successful technology development to green the sector critically requires access to green energy as well as customers willing to pay for greener solutions. He pointed to hydrogen-based decarbonisation as an interesting avenue for the steel sector but pointed out an important constraint: the vast amounts of renewable energy required The absence of viable solutions at present, he concluded, requires further public R&D aimed at greening the sector.

David Almström, formerly of Northvolt, a Swedish company founded in 2016 with the purpose of developing the world’s greenest lithium-ion batteries for electric vehicles and energy storage and that declared bankruptcy in November 2024, provided a private sector experience on the battery sector in Sweden Citing China’s widespread adoption of electric vehicles as an example, Mr. Almström highlighted the importance of public sector involvement in building markets for green technologies According to him, effective technology development and diffusion require not only financial investment, but also cultivating strong innovation ecosystems. An illustrative case is the emergence of a green energy cluster in northern Sweden, where multiple companies are co-locating and collaborating - a process that, he noted, could be actively supported by policy makers. Mr. Almström further underscored the importance of learning from failure. Drawing on the case of Northvolt, he observed that as green technologies are significantly more expensive than existing alternatives, they are unlikely to succeed unless consumer behaviour changes and further efforts aimed at reducing the price difference are undertaken

Pekka Pursula, Research Director at the VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland, provided insights from the quantum technology innovation ecosystem in Finland. He described the sector as being primarily driven by startups and highlighted the importance of ecosystems that bring together universities, research infrastructure, and companies willing to take the lead in advancing the field Mr. Pursula stressed that STI policies should lay the foundation for these ecosystems. Moreover, he emphasised that while public funding played a critical role, attracting private investment was also essential to sustaining progress. He noted that early-stage quantum ventures often face long development cycles and high capital requirements, making blended financing models particularly important. He argued that public policy should not only de-risk initial R&D but also support mechanisms such as co-investment schemes and public procurement to incentivise private sector participation

Reflecting on Finland’s experience with classical computing - which ultimately failed commercially but helped catalyse the country’s ICT sector- he argued that failures can still yield valuable know-how and long-term strategic benefits.

After the statements of the speakers, Christian Naczinsky reminded participants that STI decisions cannot be made in isolation from broader policy considerations such as industrial policy. He emphasised the need to situate STI within an integrated policy landscape, acknowledging its cross-cutting nature.

In the discussion, a few other important issues were raised, including:

Agile future orientation – consistent long-term goals, but flexible and agile enough to adjust to changing conditions

Procurement barriers – STI and procurement communities working in silos, with weak foresight in traditional structures that require policy attention.

Limited inclusiveness – insufficient attention to equity and broad participation in innovation.

Strategic foresight – identifying key niche areas effectively for strategic investments is an important element

SUMMARY OF DISCUSSIONS

Session 2 Technology diffusion and frontier development

Moderated by Nannan Lundin, Swedish delegate to the OECD-TIP and representative of Sweden’s Innovation Agency (Vinnova), session 2 took a practical look at country-specific initiatives designed to advance FTs. The session aimed to explore what trade-offs countries encounter in practice and how different policy approaches attempt to reconcile the tension between technological development and diffusion (Figure 3)

Figure 3. Speakers and guiding questions for session 2

Brian MacAulay, Principal Economist at Digital Catapult in the UK, explained that there are currently nine Catapult Centres that were created to tackle a longstanding challenge in the UK: despite excelling in research and idea generation, the country struggles to scale and commercialise innovations effectively. The mission of the Digital Catapult, established in 2013, is to accelerate the practical application of digital technologies, particularly deep tech. The organisation focuses on addressing both supply (e.g. limited SME access to advanced infrastructure and R&D facilities) and demand-side market challenges (e.g. low industry adoption of emerging technologies due to risk aversion or lack of digital maturity). He also acknowledged that the UK tech market is highly imbalanced due to the dominance of large global players, which can distort opportunity distribution.

To address these challenges, Digital Catapult provides targeted support through digital experimentation, consultancy, and broader innovation services. Its experimentation facilities, such as 5G testbeds and immersive labs, allow SMEs to test and refine their technologies in collaborative environments Consultancy services offer strategic guidance on business models, market entry, and technical deployment, while broader support includes partnership building, funding access, ecosystem development, and skills training Mr. MacAulay stressed the importance of evolving these services in line with rapid technological advancements to remain relevant and impactful. More details about Digital Catapult were provided during the poster session that took place later that day (see Figure ).

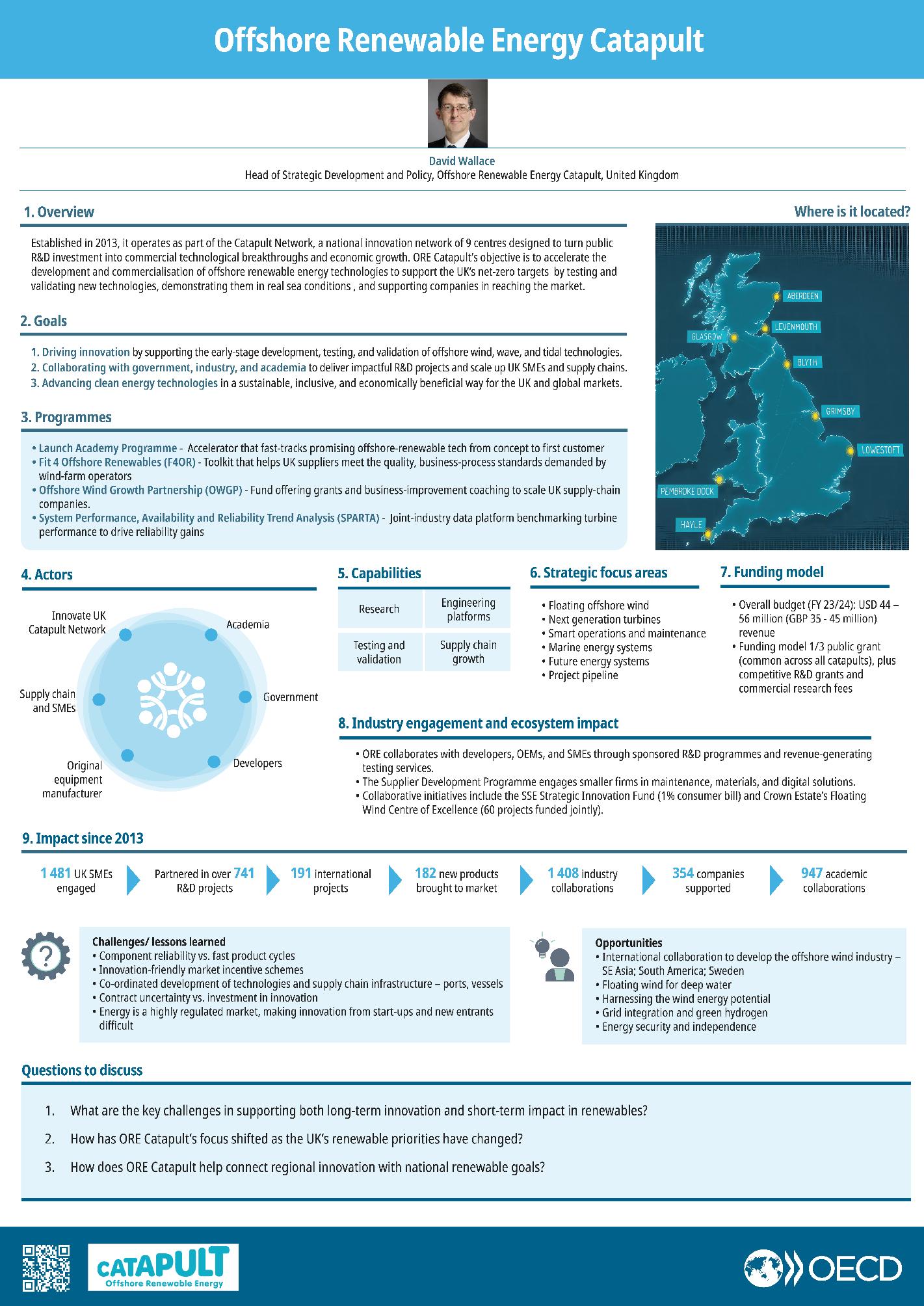

David Wallace, Head of Strategic Development at the Offshore Renewable Energy Catapult (ORE) in the UK, presented the ORE Catapult, which was established in 2013 to consolidate and advance efforts in offshore, tidal and wave energy which were identified as major contributors to the UK’s energy supply at the time. According to him, a key challenge that ORE sector faces is capability-building particularly in

OECD-TIP EVENT – PARIS, 18 JUNE 2025

advancing technologies such as floating wind platforms and next-generation tidal turbines, which require specialised infrastructure, skilled engineering, and coordinated supply chains Mr Wallace highlighted the long-term work needed to transform promising energy technologies into a stable, competitive national industry. In-depth insights on the ORE Catapult were provided during the poster session of that took place during the TIP meeting the day after (see poster in Figure 4)

Mario Ragwitz, Director of the Fraunhofer Institute for Energy Infrastructures and Geothermal Systems in Germany, focused on the German experience with hydrogen technology, which gained significant momentum after Germany announced its goal to become carbon neutral by 2045. For Germany, he explained, replacing fossil fuels became a national imperative, and hydrogen emerged as a promising yet highly uncertain option. According to him, challenges were manifold: it remained unclear in which sectors hydrogen would be most effective; costs were high; and the supply-demand-infrastructure puzzle presented complex coordination problems. Prof. Ragwitz emphasised that the scale and complexity of the hydrogen transition requires both long-term commitment and the ability to adapt over time. Germany’s approach combined strong state commitment with delegated problem-solving: the flagship projects were launched through an open call, and consortia were empowered to form organically based on expertise and shared goals. This generated over 200 proposals and ultimately led to the formation of three coordinated Hydrogen Flagship Projects: H2Giga (focused on scaling up the industrial production of electrolysers), H2Mare (focused on offshore hydrogen production using wind energy), and TransHyDE (focused on hydrogen transport and storage infrastructure)

Prof. Ragwitz explained that the government deliberately encouraged competition among different hydrogen production technologies, including alkaline electrolysers, proton exchange membrane (PEM) electrolysers, and high-temperature electrolysers, avoiding early “picking winners”. This approach was intended to promote innovation without prematurely selecting a single preferred solution. In the current phase, the programme is increasingly focused on supporting the most promising technologies to scale and enter the market more broadly, with the goal of achieving substantial cost reductions. He also underlined the importance of a long-term strategic perspective, noting that the development of such complex infrastructure typically requires sustained commitment over many years. While the programme has a tenyear design horizon, future phases of funding are still subject to political decisions. Major challenges include maintaining collaboration, ensuring continuity, and enabling a smooth transition from public support to market-driven deployment. In-depth insights on the Hydrogen Flagship Projects initiative were provided during the poster session that took place during the TIP meeting the day after (see poster in Figure 5)

Daniela Murhammer-Sas, Policy Officer at Austria’s Ministry for Innovation, Mobility and Infrastructure, presented the AI for Green initiative. Launched in 2021, this Austrian initiative links AI technologies with key green transition projects in several areas, including energy, mobility, and the circular economy. She explained that these sectors aligned with Austria’s technological strengths and the policy priorities of the federal government. Since the initiative’s inception, nearly EUR 26 million in public funding has supported 46 cooperative projects, each running in partnership between research institutions and industry, with special attention given to including SMEs. According to her, the dual objective is to advance AI technology while simultaneously contributing to environmental goals. Ms. Murhammer-Sas acknowledged the substantial effort required to facilitate matchmaking between research and industry, and one of the main challenges identified was fostering mutual understanding and communication between the AI and green communities.

Sylvia Schwaag Serger, President of the Royal Swedish Academy of Engineering Sciences (IVA), concluded the panel with reflections on the four case studies. She identified a recurring dilemma: the need to balance speed and stamina. According to her, while geopolitical and economic pressures call for rapid action, technological leadership also demands long-term perseverance. Prof. Schwaag Serger noted a visible trend of policy convergence, with countries focusing on the same set of FTs. While this may appear as policy mimicking, she argued it is both understandable and not inherently negative. Another point she

SUMMARY OF DISCUSSIONS

raised was the risk of capture, where large incumbents dominate the policy agenda. She mentioned that although it was important not to pick winners prematurely, governments must also know their innovation ecosystems well. This includes identifying where key capabilities were located, for example in national research institutes, university spin-offs or regional industrial clusters, and aligning policy instruments to support them effectively. She also emphasised that large firms and start-ups were vital to the successful diffusion of general-purpose technologies (GPTs).

Prof. Schwaag Serger also stressed that enabling the diffusion of GPTs was a cross-sectoral challenge, emphasising that it extended beyond STI ministries and touched on issues such as skills development, innovation ecosystems, and access to capital. Successfully spreading these technologies, she argued, requires aligned action across these systems.

The discussion highlighted several key policy issues and questions, these regarded the challenge of bridging strategy and execution, articulating diffusion with national and local returns in the context of an international innovation ecosystem and the specific need for government to enable innovation by providing for framework conditions, including infrastructure, competition & collaboration as well as the funding ecosystem. Providing for these conditions in turn requires engaging with all STI actors.

OECD-TIP EVENT – PARIS, 18 JUNE 2025

SUMMARY OF DISCUSSIONS

Figure 4. Poster of the UK Offshore Renewable Energy Catapult

5. Poster Germany Hydrogen Flagship Projects

OECD-TIP EVENT – PARIS, 18 JUNE 2025

Figure

Session 3. Regional capabilities and strategic technology investments

Pierre-Alexandre Balland, Economist and Chief Data Scientist of the Centre for European Policy Studies and visiting professor of the Growth Lab at Harvard University, delivered a keynote on regional capabilities and strategic technology investment, moderated by Tiago Santos Pereira, Director of the Centre for Social studies of the University of Coimbra and Chair of the OECD TIP Working Party (Figure 6)

Figure 6. Moderator and speaker of session 3

Mr. Balland addressed the question of which technologies and industries should countries prioritise to shape their economic, social, and environmental futures by proposing two key concepts to support decision-taking as which tech priorities to set: i) economic complexity, which reflects the potential economic impact and value of a technology, and ii) relatedness density, which indicates how likely a country is to develop a new technology based on its existing capabilities i.e. opportunities for diversification. By combining complexity and relatedness, he proposed a typology of strategic choices (see Figure 7): moonshots (high risk, high return), incremental growth (low risk, low return), strategic investment (high risk, low return), and optimal investment (low risk, high return).

SUMMARY OF DISCUSSIONS

Figure 7. Smart investment graph

Reflecting on empirical analyses on these factors, he stressed the concentrated and “spiky” nature of innovation ecosystems, with capabilities and resources often clustered in a limited number of locations and actors.

Taking the concrete case of the EU, Mr. Balland argued for the importance of better leveraging complementarities, especially given the fragmentation of innovation efforts across the EU compared to the United States. Policy decisions about where to locate technological investments, he argued, must consider in more detail regional ecosystems; macro-level indicators may hide the fact that certain cities or areas lack the necessary capacity. Those regional dynamics, in turn, need to be articulated in a cohesive EUlevel strategy whereby complementarities are leveraged.

The following items were raised in the discussion that followed:

i) On concepts & frameworks

• Questions about terminology (e.g. “relatedness”) and the appropriate unit of geographical analysis in strategic investment.

• Clearly defining what is meant by “prioritising” technologies, since this can serve different purposes.

• Developing frameworks for evaluating technological priorities, grounded in current capabilities and strategic foresight.

ii) On technology investment & prioritisation

• Risks of misaligned investments between cities or regions, especially when political choices override preparedness.

• The need for prioritisation to reflect regional expertise and existing research capacities, with caution against overly broad lists lacking sufficient funding.

• Effective prioritisation requires alignment between ambition, local ecosystems, and long-term investment planning.

• The question of whether new technology leadership requires also disregarding at times local capacities, as illustrated by the successful example of some of Korea’s past bold industrial policies

OECD-TIP EVENT – PARIS, 18 JUNE 2025

iii) On strategic & policy perspectives

• Recognition that technology evolves constantly, with different approaches reflecting different goals (e.g. EU focus on products/markets vs. US emphasis on research and innovation).

• The need to also consider national security dimensions alongside economic impact in technology assessments.

• Challenges to moonshot frameworks, given limited financial and political feasibility in many countries.

• Concerns about declining feasibility of international complementarities in a fragmented geopolitical landscape, as governments increasingly pursue national strategies.

• Prioritisation shaped by geopolitical uncertainty and concentrated technological capabilities.

Session 4. Brainstorming and interactive policy practice discussions

Session 4, introduced by the Head of Secretariat of TIP Caroline Paunov, was an interactive session aimed at brainstorming and discussing policy practices (Figure 8). Delegates engaged in small group discussions on the impacts of FT developments on national innovation ecosystems. The session featured poster presentations from two initiatives - the United Kingdom’s Digital Catapult and Korea’s Innopolis regional innovation hubs - and a brainstorming session on national FT development plans.

Figure 8. Topics and speakers of session 4

Brian McAulay presented the UK’s Digital Catapult (see poster in Figure 9), expanding the details presented during panel Session 1 Now in its third round of funding, Digital Catapult supports the diffusion and adoption of advanced digital technologies, including AI, immersive systems, the internet of things, and quantum technologies. Operating through a network of interconnected labs and testbeds across the UK, Digital Catapult supports pre-commercial product development of startups and larger firms that lack internal R&D capacity. The programme also manages a small investment fund to support promising ventures to strengthen the UK innovation ecosystem. He also emphasised in exchanges that the Catapult does not own IP, strives to keep procedures lean to maximise engagement (e.g. via expression of interest forms), works mainly within the UK, and focuses on ecosystem development rather than on generating profit directly

SUMMARY OF DISCUSSIONS

9. Poster on the UK’s Digital Catapult

OECD-TIP EVENT – PARIS, 18 JUNE 2025

Figure

SUMMARY OF DISCUSSIONS

Figure 10. Poster on Innopolis, Korea

Korea’s Innopolis initiative, led by the Korea Innovation Foundation under the Ministry of Science, was presented by Soo Chang Son (see poster in Figure 10) Innopolis aims to foster regional innovation hubs that support technology commercialisation. He emphasised this was done with a flexible, “no one-size-fitsall” approach to best align national priorities with regional industrial needs. Key features are fostering collaboration between academia and industry by acting as a “translator” and matchmaker, investing time (rather than money) into building trust and connections. Instruments used include R&D grants for startups and SMEs and joint university-industry R&D programmes. To ensure private sector engagement, industry co-funding is used to access funding support.

Session 5. Complementarities and trade-offs in the STI policy mix

Session 5, moderated by Tiago Santos Pereira, Director at the Centre for Social Studies, University of Coimbra and Chair of the OECD TIP, focused on the complementarities and trade-offs between technology development and diffusion in STI policy mixes (Figure 11). Experts addressed how to design more coherent frameworks that align frontier innovation with inclusive technological diffusion, considering context-specific capabilities, governance models, and policy instruments.

Figure 11. Speakers of session 5

Muthu de Silva, Professor at Birkbeck-University of London, raised two major issues in her intervention. She argued that current funding FT strategies overwhelmingly favoured R&D over diffusion, leading to insufficient diffusion and negative impacts on FT ecosystem development. Greater support to foster diffusion is needed as regards strategic engagement with users and firms to foster wider diffusion

She also argued that there was often a lack of coordination between R&D funding portfolios which causes a disconnect between high-level strategic mission statements and real project impacts with major project fragmentations

Better alignment of the portfolio may be supported by creating roles such as champions, mission directors, or ambassadors as done in the context of some UKRI projects. These roles integrate projects, identify complementarities, and reduce the burden on individual projects to deliver impact in isolation. This approach acknowledges that technologies do not operate in silos and supports diffusion targets and mission delivery by fostering coordination across projects and aligning them with strategic ambitions.

OECD-TIP EVENT – PARIS, 18 JUNE 2025

Marzenna Weresa, Professor at the SGH Warsaw School of Economics and Chairperson at the Committee of Economic Sciences at the Polish Academy of Science, stressed the need for adaptive governance strategies that promote ecosystem building, inclusive education, and collaborative structures She argued that whether a country should prioritise technology development or diffusion depended on its stage of development, resource availability and technological capabilities. She also identified relational capital – the ability of different actors to collaborate – as a bottleneck for countries seeking to develop frontier technologies.

Prof. Weresa illustrated her points with examples of regions that have successfully combined development and diffusion strategies: the Silesia region in Poland, specialising in the ICT and AI sectors; and the Piedmont region in Italy, with its strong innovation clusters She underscored the importance of support tailored to individual firms, such as Poland’s Innovation Coach programme targeting SMEs and start-ups. Successful strategies, she argued, also involve smart specialisation in niche areas, investment in education and talent (reskilling, addressing skills gaps, and preparing students for future challenges), and adaptive governance models that embrace cross-government coordination, learning from failure, and continuous adaptation

Florence Benoit, Economist and Policy Analyst at the Directorate-General for Research and Innovation at the European Commission, referred to the Draghi report’s emphasis on FTs as critical for resilience and competitiveness. While Europe has seen a decline in its share of complex technologies, she argued that it remained strong in green innovation. She stressed that the EU’s STI policy approach treats diffusion as a foundational pillar of the innovation system, not as a secondary priority, and that efforts were under way to enable more agile policy experimentation and alignment of regulatory frameworks with technological needs.

Osorio Coelho, Director of Innovation Programmes at the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation (MCTI) in Brazil, shared insights from the National Fund for Technology and Innovation and the "New Industry Brazil" programme – a major federal industry policy launched in January 2024 and structured around 6 missions, each aimed at transforming a different sector of the Brazilian industry and designed jointly with stakeholders. The current policy mix in Brazil, he explained, aims at supporting both frontier innovation and broad-based technology, as illustrated by the example of the National Sustainable Aviation Fuel Programme

Mr Coelho explained that a major challenge was ensuring that strategic goals were translated into programmatic action, and highlighted the need for institutional coordination across ministries and agencies to avoid policy fragmentation He described Brazil’s approach to development and diffusion as modular, with different instruments used to match the maturity level of each technology or sector – ranging from subsidies for early-stage R&D, to more complex instruments like procurement tools and subsidies for diffusion. This modular approach reflects how balance is not static but is actively governed through responsive and coordinated action

Other items raised ruing the discussion regard the merits of centralised versus decentralised systems for monitoring and foresight, the benefits and challenges of following a portfolio approach or having large vertical programmes to support frontier technology development, the need for new tools and institutional innovation to support actors and build critical mass, and the importance of investments in the educational base to support more inclusive innovation systems in the future.

SUMMARY OF DISCUSSIONS

Closing remarks

In the closing session, Tiago Santos Pereira and Caroline Paunov raised the following key items as regards the central topics and challenges of the workshop “Bridging the gap: Frontier technologies and the diffusion dilemma”:

• Speed and adaptability: The pace of FT development and adoption varies, requiring responsive policymaking and governance that can adapt to rapid technological change while aligning differing visions and levels. This ties directly to the workshop’s core theme of balancing cutting-edge advancement with broad-based diffusion.

• Diffusion as central to innovation: Diffusion is not secondary but fundamental, demanding clarity in definition, long-term commitment, and mechanisms to strengthen coordination and interconnection across innovation actors. This addresses the policy trade-offs between promoting technological excellence and ensuring inclusive uptake.

• Strategic investment and prioritisation: Effective STI policies must recognise that not all countries can lead in all domains; strategic choices should be grounded in national contexts, comparative advantages, and carefully designed financial/policy incentives. This links back to discussions on regional capabilities and economic complexity, illustrating the importance of context-sensitive approaches.

• Innovation ecosystems and evidence: Building ecosystems responsive to business needs requires strong institutions, robust evidence, and governance frameworks that balance central guidance with decentralised action (“centralised decentralisation”). This reinforces the workshop’s emphasis on the role of institutions in sustaining both innovation leadership and widespread technology diffusion.

OECD-TIP EVENT – PARIS, 18 JUNE 2025

Annex. Event agenda

9h00-9h30: Welcome coffee

9h30-9h45: Welcome and introduction

The Chair of the TIP Working Party and the OECD Secretariat welcomed participants and introduced the aims of the event.

• Tiago Santos Pereira, Director of the Centre for Social Studies of the University of Coimbra and Chair of the OECD TIP Working Party, Portugal

• Jerry Sheehan, Director of the OECD Directorate for Science, Technology, and Innovation

• Caroline Paunov, Head of Secretariat of the OECD TIP Working Party Presentation available here.

9h45-10h45: Session 1. Strategic choices in advancing frontier technologies

This session examined how factors such as market size, resource availability, industrial capacity, and regional development priorities influence a country’s decision to invest in and support frontier technologies. Participants discussed why governments opt to attempt to lead in these technologies or adopt a more cautious, “wait-and-see” approach, exploring the roles of risk tolerance, opportunity costs, and strategic objectives in shaping STI policies.

Questions addressed by the speakers:

• What criteria should policymakers use to decide whether to invest in frontier technologies, especially when multiple countries may be racing toward the same goal? Can everyone realistically “win”?

• How do security considerations, risk tolerance, and opportunity costs interact when choosing specific technology priorities for national STI policies?

• Under what conditions might a “fast-follower” approach be a viable alternative for countries and regions that lack the resources or capacity to lead at the global frontier?

Moderator:

• Christian Naczinsky, Head of department EU and OECD Research Policy, Austrian Federal Ministry of Women, Science and Research, Austria

Speakers:

• Rizwan Janjua, Head of Technology at World Steel Association

• Soo Chang Son, Executive Director of Planning & Management Department, Korean Innovation Foundation, Korea

• Hande Alpaslan, Head of the Department of Science, Technology, and Innovation Policy at the Scientific and Technological Research Council, Türkiye

• David Almström, Former Director Product at Northvolt, Sweden (virtual)

• Pekka Pursula, Research Director on Microelectronics and Quantum Technologies at VTT Technical Research Centre, Finland

10h45-11h15 Coffee break

SUMMARY OF DISCUSSIONS

11h15-12h15: Session 2. Diffusion and frontier technology development

In this session, participants explored practical policy experiences around directing resources towards highrisk, frontier breakthroughs, or in concentrating limited resources in pre-existing sources of excellence, versus an approach that privileges technology diffusion in the economy more broadly. In each case, participants emphasised how, and whether, there are socio-economic or political trade-offs or positive spillovers between concentrating support in excellence versus more broad-based STI support.

Questions addressed by the speakers:

• What is the role of diffusion for advancing competitiveness in key frontier technologies?

• What policy initiatives have worked best for ensuring diffusion of those technologies?

• What lessons can be taken from experiences in concentrating resources on high-risk breakthroughs as regards concentrating resources in centres of excellence and diffusion dynamics?

• In what ways can targeted interventions in centres of excellence generate positive spillovers for the wider economy, and under what circumstances might they risk widening innovation gaps?

Moderator:

• Nannan Lundin, Chief Analyst at the Strategic Intelligence, Sweden’s Innovation Agency (Vinnova), Sweden

Speakers:

• Brian MacAulay, Principal Economist, Digital Catapult, and David Wallace, Head of Strategic Development and Policy, Offshore Renewable Energy Catapult, United Kingdom

• Daniela Murhammer-Sas, Policy Officer at the Federal Ministry Innovation, Mobility and Infrastructure, Austria

• Sylvia Schwaag Serger, President of the Royal Swedish Academy of Engineering Sciences (IVA), Sweden

• Mario Ragwitz, Director of the Fraunhofer Institution for Energy Infrastructures and Geothermal Systems IEG, Germany

12h15-13h45: Lunch break

13h45-14h30: Session 3. Regional capabilities and strategic technology investments

In a time of rapid technological transformation, regions stand at a critical juncture – facing both unprecedented opportunities and complex challenges in shaping their economic futures. This session explored how regions can harness the concepts of relatedness and knowledge complexity to craft forwardlooking development strategies and make well-informed investment decisions. The discussion focused on identifying realistic pathways for diversification into high-potential, strategically important technologies and sectors, helping regions position themselves for long-term, resilient growth.

Moderator:

• Tiago Santos Pereira, Director of the Centre for Social Studies of the University of Coimbra and Chair of the OECD TIP Working Party, Portugal

Speaker:

• Pierre-Alexandre Balland, Economist and Chief Data Scientist of the Centre for European Policy Studies and Visiting Professor of the Growth Lab at Harvard University, France Presentation available here.

OECD-TIP EVENT – PARIS, 18 JUNE 2025

14h30-15h30: Session 4.

Brainstorming and interactive policy practice discussions

During this interactive session participants brainstormed in small groups on the impacts of frontier technology developments for innovation policy and heard from initiatives working at the forefront of this space. Delegates also gained insights from two innovation ecosystem initiatives aimed at developing and diffusing frontier technologies, sharing firsthand experiences of what worked, what didn’t, and why. Open small group discussions with representatives from these initiatives touched on the diverse aspects of these initiatives, including funding mechanisms and cross-sectoral partnerships.

Interactive items:

• Brainstorming on Frontier Technology Development Plans and Their Impacts on National Innovation Ecosystems

• United Kingdom's Digital Catapult with Brian MacAulay, Principal Economist, Digital Catapult, United Kingdom

• Innopolis: Korea’s Regional Innovation Hubs for Technology Commercialisation with Soo Chang Son, Executive Director of Planning and Management Department, Korean Innovation Foundation, and Myeong-Jong Noh, Deputy Director of Critical and Emerging Department at STI Office, Ministry of Science and ICT(MSIT), Korea

15h30-16h00: Coffee break

16h00-17h00: Session 5. Complementarities and trade-offs between technology development and diffusion in the STI policy mix

The final session reflected on whether, at the level of STI policymaking and the institutions that are responsible for supporting STI ecosystems, the policy mix does – or should – prioritise diffusion over development. The session was an opportunity to reflect on the messages of earlier discussions, and to explore whether the strategic political visions for STI that are articulated by governments reflects the actual focus of STI support.

Questions addressed by the speakers:

• Does the policy mix at national or regional levels explicitly prioritise diffusion over development? If so, in which contexts or sectors?

• How can the strategic visions articulated by governments be aligned with on-the-ground STI support, ensuring that high level goals translate into practical action?

• In adapting to fast-changing technologies and markets, what role do institutions and governance structures play in maintaining a healthy balance between pushing the frontier and enabling broadbased technological uptake?

Moderator:

• Tiago Santos Pereira, Director of the Centre for Social Studies of the University of Coimbra and Chair of the OECD TIP Working Party, Portugal

Speakers:

• Muthu de Silva, Professor in Innovation and Entrepreneurship, Birkbeck, University of London

• Marzenna Weresa, Professor of Economics at the SGH Warsaw School of Economics and Chairperson at the Committee of Economic Sciences, Polish Academy of Sciences, Poland

• Florence Benoit, Economist and Policy Analyst at the Directorate-General for Research and Innovation (DG RTD), European Commission

SUMMARY OF DISCUSSIONS

BRIDGING THE GAP: FRONTIER TECHNOLOGIES AND THE DIFFUSION DILEMMA 29

• Osorio Coelho Guimaraes, Director of Innovation Programs (DEPIN) at MCTI and Acting Secretary of the Secretariat of Technological Development and Innovation (SETEC), Brazil (virtual)

17h00-17h15: Wrap-up and closing of the event

The Chair, Tiago Santos Pereira, and the Head of Secretariat of the TIP Working Party, Caroline Paunov, summarised insights and conclude the event.

OECD-TIP EVENT – PARIS, 18 JUNE 2025