Re-framing My Body–2:

Re-framing My Body–2: Countering Stereotyped Portrayal of Women is a project that was originally scheduled to take place between September 2021 and March 2022 online and in Kyiv, Ukraine. It was interrupted by the full-scale war started by Russia against Ukraine on February 24, 2022.

The project started off in the fall of 2021 with online lectures for women artists by Kateryna Radchenko, Hanna Wildow and Sybrig Dokter. The participants reflected artistically on their experience of looking at and analyzing how women are portrayed in media and the arts. This material was used to create a video that is now available online. Since it was impossible to continue the project as planned and run inperson workshops in Kyiv, we decided to direct our gaze to women and non-binary people who have chosen to put their lives at risk at or near the frontline.

We chose heroix engaged in various fields: soldiers and officers of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, medics, volunteers and journalists. Some of them have been working since 2014, others joined the fight after February 24, 2022. They shared their stories about their motivation, what it means to be a woman or non-binary person on the frontline, and how they deal with switching from civilian life to war and back.

We are presenting a series of interviews with them, together with photos of their lives at war.

The project is funded by the Creative Force program of the Swedish Institute and is a collaboration between Art Travel (Odesa Photo Days Festival) and Lava-Dansproduktion.

Mariia Lesniak (Ester)

25 years old

Company’s head nurse and medic in the evacuation crew. Call sign ‘Ester.’ Joined the Armed Forces of Ukraine in September 2022. In civilian life, she worked as a surgical nurse.

I knew I could work with wounded people, no matter how horrible their injuries, because I had worked as a surgical nurse in civilian life. I was never afraid of blood, and in the operating room, I learned to work in stressful and uncomfortable conditions. Working in the evacuation vehicle, however, is more difficult.

I decided to join the army in the fall to give myself time to get used to the new conditions since I cannot function normally in the heat. Just then, in August 2022, the 47th Assault Regiment (now the 47th Magura Brigade) issued a call-up for soldiers to join its ranks. Just a half hour later, I applied for an interview, and my application was approved. A week later, I had an interview and started gathering documents for the military recruiting office. This was certainly a surprise to my family and friends, and I felt they did not understand why I was doing this. But everyone tried to support me anyway. My parents are wonderful people and role models for me. They always stand by me.

The voice of conscience gave me that final push to join the Armed Forces of Ukraine. After all, I am a citizen of my country, and it is my duty to defend it. Many people think they have no place in the army because they don’t see themselves in the trenches or inside a tank. However, the armed forces offer a variety of positions, and everyone can find something for themselves. Especially if they enlist voluntarily.

My job is to do my best to get the wounded to the stabilization point alive. Sometimes we pick up a severely wounded person and stabilize them even before we get there, thanks to protocols and our ability to respond quickly. This is where I feel useful and needed. Sometimes soldiers just need to hear that everything will be okay and hold my hand. It’s not much, but it gives them the strength to keep fighting for their lives.

I can only mention that men are willing to help me. I know that in other units, women face discrimination, but my comrades are wonderful, noble people. I have never heard them say anything offensive about me. Also, we have quite a few women in our brigade, so it’s not a surprise for anyone to see a young woman in uniform. Everyday tasks such as cooking or cleaning up are done by anyone; only the hard physical work is done by men.

As part of my training, I studied the Tactical Combat Casualty Care (TCCC) protocols, trained, and bought what I thought I needed to take with me. For example, a uniform. Of the things I was provided, only T-shirts and summer field pants fit. And I was lucky with the boots because my size, 38, was available. Everything else I had to buy myself. I would like to thank the Zemliachky charity project for helping women with uniforms.

I had the same problem with plate carriers, helmets, and other gear. With my first paycheck, I ended up buying everything myself because these items are frequently not designed to fit the unique proportions of a woman’s body.

It is difficult to give advice to women who are about to be drafted or sign a contract. After all, the gear they will need depends on their future duties and responsibilities. Here are some universal tips: nowire bras, comfortable shoes, a warm sleeping bag, even in summer, and a quick-drying travel towel. I always carry skincare products and all kinds of facial masks to feel like a woman, at least sometimes.

During the warm season, we wash outdoors using sun-warmed water. It gets more difficult in winter: Sometimes we ask the locals if we can use their shower or heat water in a kettle and wash in a tub, washing our clothes there as well. In other cases, wet wipes (preferably odorless and alcohol-free baby wipes) or a dry shower help. Birth control pills help me deal with my period making it less heavy and painful. We have enough personal care products—thank God volunteers support us. You can also buy these things in any village with at least one functioning store.

You don’t really get much privacy in the army except when it’s time to freshen up. We all live together, but there are no problems with that. Of course, it takes time to get used to others and find a community of like-minded people—then it gets easier.

Now we live in a basement. It’s dark and damp, but we have done our best to be at least reasonably comfortable. Our unit was recently assigned a cook, so we now have hot food. On duty, we eat dry rations, but it’s hard to heat them up, so I usually take a couple of energy bars, some fruit, a pack of freezedried food, and water. That’s more than enough for a day and a night.

In the rare moments when we are allowed to go into the city, everything feels so unreal. Folks are just doing their thing, eating whatever they’re in the mood for, going wherever. In the army, that kind of freedom does not exist. It’s a whole process every time you want to head out into civilization. You’ve got to ask for permission, stay connected the whole time you’re out, and provide the exact time you’ll be back. I know that after the victory, I will appreciate my life and freedom much more.

That’s why I have a hard time seeing photos on social media of people partying, especially young men. In the morning, you’re helping evacuate a man with an amputated foot, and in the evening, you stumble upon a video of a guy his age sipping beer by the pool. It feels so unfair and disheartening. Our purpose here isn’t to ensure they can get drunk at clubs and belt out Russian songs at karaoke. People are being wounded and killed, and someone has to replace them. It’s strange that civilians still do not understand this nor prepare for it.

I have lost touch with most of my civilian friends: What do we even have to talk about? They travel and experience all sorts of things while I go back to my basement, peel off my armored vest at last, close my eyes, and all I see is that man with a hole in his head I could not rescue. There are times when I really want to go home, hug my mom, cuddle my cat, and forget about the army as a bad dream.

But I met my love and many luminous people here, and it feels like home. And on the day of our victory, I will be able to honestly say to myself that I did everything I could to bring it closer.

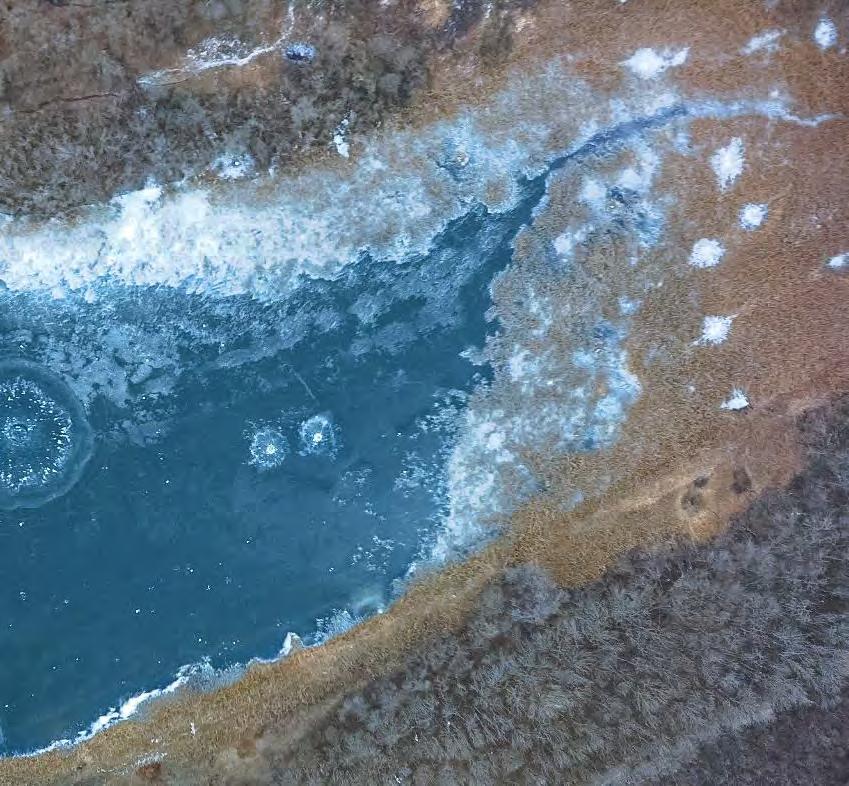

War today feels and looks very surreal. For example, my fellow soldier was picking up the body parts on the street while a civilian woman was hanging wet laundry to dry in the house next door. Or I’d sleep in the basement at night with frogs and centipedes to the sound of shelling and eat lunch in the best restaurant in the neighboring town during the day because the commandment allowed me to leave for a few hours. The guys leaving on an assault mission joke about taking pictures of their legs. In the deserted villages, nature is reclaiming its space. Everything blends together like in a kaleidoscope, and it all feels a bit surreal.

25 years old

Drone pilot, call sign ‘Deni.ʼ Has served in the Armed Forces of Ukraine since September 2, 2022. Before that, Tania was a director at a popular TV channel and played in a music band.

In civilian life, I worked at 1+1 TV channel as an on-air promo director. I was primarily involved in creating trailers and teasers for major shows such as Dancing with the Stars, The Voice of Ukraine, and Masquerade, as well as TV series. I also had a band and a solo project called MONEYPULLLATER that is currently on hold, as well as directing.

I decided to enlist in the Armed Forces of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, but did not join until early September. I used these six months to settle all professional and family matters. I knew it was a responsible decision to join the army during the war and that I would not be able to go home and solve my problems if something came up.

My colleagues have received my decision with understanding. I am still an employee of the TV channel—they did not fire me, and I can return to my job after the victory. My colleagues are fully behind me. My family also supports me, but for my mother, my decision came as a shock. I prepared her for this for a long time, and in the end, she came to terms with it.

My main motivation to join the armed forces was that I knew I could serve. In the first six months after the full-scale invasion began, I was not only dealing with my personal stuff but also volunteering. I talked to many people, and some of them were upfront with me and admitted, “I’m afraid to join the armed forces, I just can’t do it.” However, I realized that I was not afraid and that it would be wrong and dishonest if I did not enlist. First and foremost, I would have been dishonest with myself. If I could do it, I had to do it.

Actually, I did not exercise much before I was drafted. I started working out only about a month before that because sports had always been my lowest priority. My friends raised some money, and a day or two before I left, we went shopping to buy the things I would need for the first time.

Now I am in aerial reconnaissance. We fly Mavic drones, adjusting artillery fire and providing situational awareness during combat operations and evacuations. We monitor a certain direction, a certain sector in our area of responsibility. As a director, I was used to working with drones. There was some filming for the TV channel where we also did general panoramic shots, but I was not the drone operator then. I just told people what I needed to film and where I wanted the drone to fly. And now, I have learned to pilot the drone myself. My previous experience helps me: I know roughly what the picture will look like and from which angle I have to film. Sometimes you have to fly in from different angles to see if it’s the military equipment there or something else.

It was hard to get used to shelling because I couldn’t tell whether we were firing or the enemy was. There was firing from all sides, and I didn’t always know what to do, how to react, when to hide, and when it was our artillery that was working and everything was fine. But a month or two later, I could already distinguish the sounds I heard nearby.

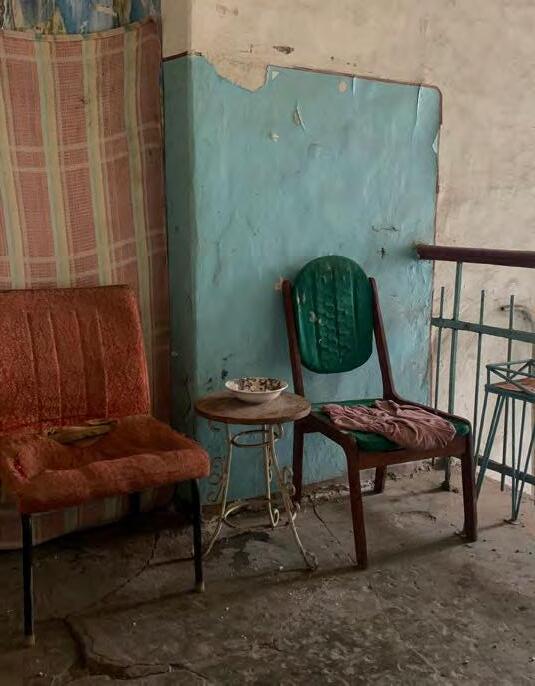

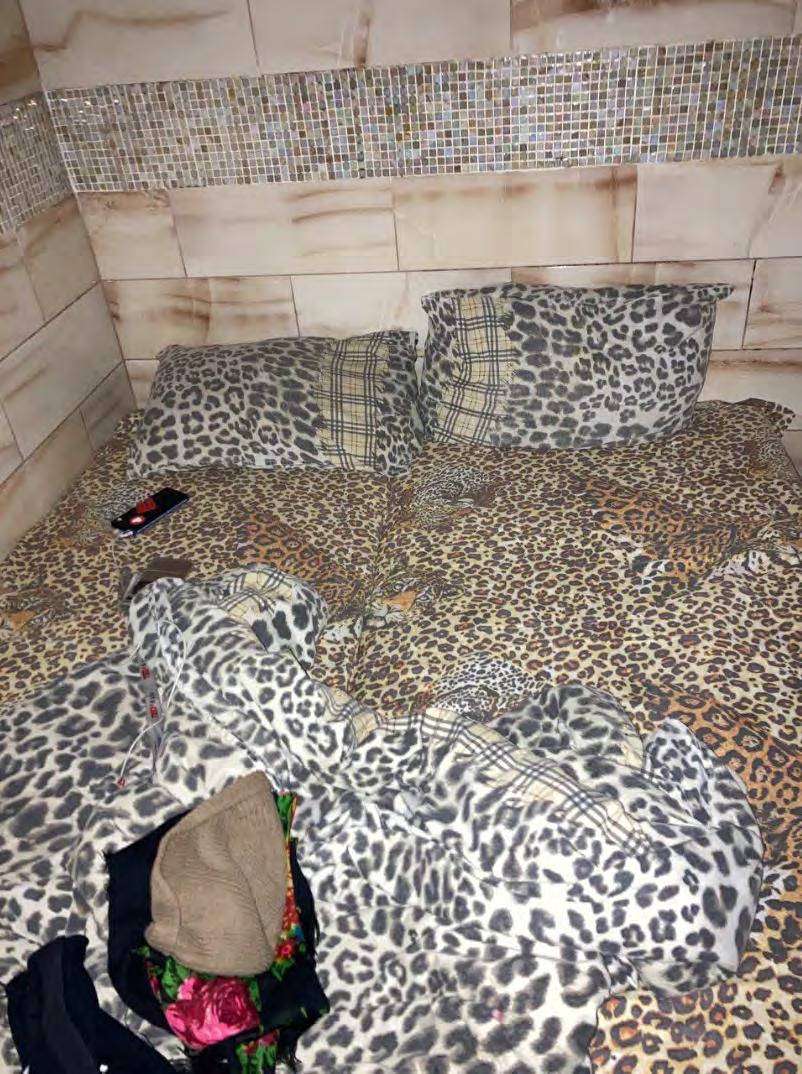

We stay in abandoned houses. The local authorities help us by showing us the houses where we can move in, or people simply point out the house that has been empty for many years and whose owners are gone. There is not always water and electricity. We take care of that ourselves. Some people sleep in a sleeping bag on a mat. But I sleep on a cot because I can catch a cold easily. We spend most of the time in the trenches at the front or deep in the forest from where we operate drones. We only come back to the house to sleep.

Usually, we all live in the same room, so there is barely any personal space. On my last rotation near Bakhmut, I had a small private room. It was so small that only one person could fit in it. And I was so lucky to get it.

The hardest thing for me is the constant desire to wash. It’s especially hard when I have my period and there’s no way to wash. You just walk around dirty and dream about the shower. You wipe yourself down with wet napkins, but half an hour later, you are dirty, sweaty, and smelly again. The first thing you do when you return to civilization is shower—two or three times a day. You really appreciate this opportunity to wash yourself.

When I have my period, I use plain sanitary pads. That’s the most hygienic option because you’re not touching anything down there, and in those conditions, you just don’t want to touch anything with your dirty hands. I would recommend women going to the front for the first time always to have pads or tampons with them. Because sometimes it happens that you don’t know where you can find yourself in an hour or a day. At any moment, you can be pulled out and sent elsewhere. Once, I didn’t have anything with me when they sent me to another location for a day, and my period started. I asked my comrades to bring me the pads, which they did, but it was an awkward situation.

As for the military uniform, I feel fairly comfortable wearing it. In civilian life, I’m used to oversized clothing, and I wear a lot of men’s clothing. So it’s very much my style, just military.

I like to capture the atmosphere at the front with my camera. Sometimes I just see something special in the most ordinary things, even in the garbage. Once, we moved into a house, and there was a bed, a chandelier, and a pillow sitting outside in the yard. It was not us who brought them outside. They were already there. As I took a picture of these things, I imagined this chandelier hanging inside. I imagined someone sleeping on that bed in that house. It was as if I could see the history of these things and the people who lived in this house and touched them. And because of the war, all these things are now abandoned, neglected, thrown away.

When I decided to enlist, the Armed Forces recruiting offices would not take me for a long time. They said, “Women are not drafted,” “There’s no need,” or “Go home.” I think it was on my third visit that I was finally offered a contract.

Even now, I face sexism when I hear all kinds of comments like, “Oh, what are you doing here? You should be cooking in the kitchen or having kids.” It’s all classic stuff. Sometimes I meet men who start mansplaining to me where I should be and what I should do. I react differently depending on how reasonable they are. If I see that they won’t understand anything I say, I just ignore them or snap back. But if it’s someone who is more or less reasonable and open to meaningful dialog, I try to explain why this attitude is wrong.

We don’t split daily tasks into ‘men’s’ and ‘women’s.’ Everyone makes sandwiches, and we all offer each other food. If someone has left a mess behind, it’s not the women who are told, ‘Please clean it up,’ but we try to figure out who has left the mess and now has to deal with it. There is equality and order when it comes to daily tasks.

Many soldiers admit that the longer they serve in the army, the more they lose touch with their civilian friends and family. Thank God my social circle has not changed. When I go back, I am always happy to see everyone, and we talk as always. Everyone has a different attitude about the fact that I’m now in the military. Some don’t know how to talk to me, others avoid asking certain questions, and if they do, they often apologize because they think they might ask something stupid. But I say, “Go ahead, it’s okay, you can’t know everything. I didn’t know much before I got there either, and I asked everybody the same questions you’re asking me now.”

The only thing that pisses me off when I go back to the civilian setting is when some random men start explaining things to me, apologizing, and making excuses for not being at the front. I don’t blame anyone, and I don’t want to hear their excuses. It’s their business and their decision. I understand their inner motivation. But, man, you must do something if it bothers you that much. I find it very uncomfortable to listen to all this.

30 years old

Photographer, documentary filmmaker, journalist. In civilian life, she has taken portrait photographs and directed documentaries. Since 2014 she has been filming the Russian-Ukrainian war.

I had no choice—to film the war or not. I do not identify as a war photographer, and I ask people not to call me one since I’m filming this war only because it is the war in my country. When the war started in 2014, it was quite logical for me to be where the history of my country was happening, especially since I had filmed the Revolution of Dignity and the annexation of Crimea. Like many other people, I was not prepared for such an experience. I’m not sure anyone can be prepared for something like that, but I arrived in Crimea days after the Russian troops invaded.

And later, when the Russian-backed separatists went into action in the Donetsk and Luhansk regions, I longed to be there. I felt that the information I received from various sources and media did not fully reflect what was happening. I applied for a job as a news editor as a precaution—so that I had a full-time job and could not just drop everything and go film the war. But in the end, I took the tactical medicine course that summer, quit, got a bulletproof vest from the Institute of Mass Information (they still provide freelancers with free vests and other protective gear), and traveled east for the first time in August 2014.

I had my last portrait photoshoot around February 19, on the eve of the fullscale invasion. My client was very anxious, full of nervous energy, and all revved up. And she said to me, “Shit. Have you thought about what you would do if a real war broke out?” And I remember exactly what I said to her, “Well, I have my camera, and I know for sure what I am going to do. I’m going to take pictures.” So on February 24, I woke up in the Donetsk region, my camera right next to my bed, and I had a very clear answer about what I was going to do and why. I will document this war for as long as I can.

I am a prep nerd. Simply because it’s a risky job. Aspiring photographers or colleagues who are rebooting their careers with the start of a new phase, the full-scale war, often text me and ask, “What would you recommend? How to get started? How to get an assignment? How do these things work in general?” People are curious about the mechanism—I wouldn’t call it ‘monetization,’ that’s a little too blunt—of how you practice this.

And I always say, “Wait a minute. What about tactical medicine, risk assessment, physical training, and small group work? What do you know about small arms? What about artillery? Did you get any training in demining?” In the summer of 2014, I took a course in tactical medicine at the recommendation of my friend, who was coordinating the Protecting Patriots initiative at the time.

I don’t remember my first visit to the positions, but I do remember the first time I saw the wounded. It was in the spring of 2015 if I remember correctly, and I was in the Pravyi Sector. One of the soldiers, Zelia, who is no longer with us, said, “Come join us, kid. Let’s go.” It was already pitch dark, and I knew there was no point in going there. It was kind of an adrenaline rush. I don’t think I have a single technically well-captured photo from that night to share with you because the camera I was using at the time just couldn’t do anything in that darkness.

Sometimes, in stressful moments, I have this freezing when I forget that I need to press a button or do anything at all. Then I need a little more time or something to snap me out of that state. It usually helps to stay in touch with colleagues: you constantly check in to ensure you and your colleagues are okay. It’s like hiking. I don’t believe in solo hiking. I think it sort of borders on suicide.

At that time, I was on a work assignment for Der Spiegel in Kostiantynivka in the Donetsk region. I learned from various sources that the invasion was anticipated sometime between February 20 and 25. It was my conscious decision to be there. I thought that the Donbas would become the main theater of war.

I woke up when my close friend Dima, a war veteran now on active duty, who was also my producer, security guard, and driver, stormed into my room yelling, “Julia, it’s started!” Seeing him all worked up, I realized that something really big must have happened. I grabbed my phone, and there were about 40 missed text messages. I remember the top message from my mum saying they were sheltering in the basement.

I pulled up the newsfeed, and everything came rushing at me all at once. Dima told me that we had to pick up Lou, our colleague from France—he and another reporter were stuck in Avdiivka without wheels. So we dashed to pick them up. And they said, “Take us to Kyiv. We have a flight to Paris.” We were zooming across the fields. All flights from Kyiv to Paris had been canceled by then.

Dima told me as he drove, “Check the news. What does it say?” So I scrolled down, refreshed the Ukrainska Pravda newsfeed every second, and just read everything that came up: “Uber is pulling out of Ukraine.” And he said, “Who gives a shit about Uber?” Then I said, “McDonald’s is pulling out of Ukraine. Boryspil Airport is closing,” and he was like, “Oh yeah, McDonald’s is big news,” and we burst out laughing.

I was so angry when various countries started to release their protest notes condemning Russian aggression in Ukraine. All this diplomatic bullshit. I have been watching this war for years—we’ve seen it all before. They have

been concerned for too long. There have been too many terrible episodes in this war, starting with 2014. There was the downing of MH17.

And as we raced along the fields in the Donetsk region, I had this urge to post something on Instagram, just speaking my own thoughts. So I took a selfie with a helmet and bulletproof vest and wrote a short post saying this was a decisive moment,

a point of no return. Look, world, it’s your fault. Silence kills. See what happens when you feed the monster. And I posted that with the hashtag #Ukraine.

And then something happened that I had never personally experienced. This post got picked up and appeared in the Recommended section in Poland and Germany, reaching four million and gathering 30k likes. People from all over the world started following me, and they all prayed for us, you know, and felt the urge to let me personally know about it. Then Russian bots flocked to this post with all their emojis and little flags. They told me that I was going to die in the war. A shitstorm started brewing. My post was quoted on Polish TV, CBC, CNN, and whatnot. All these people were quoting my humble Instagram. God help me!

Since February 24, I have been writing a lot, mostly for my Instagram. The media often buy not only my photos but also the texts that accompany them. This is not journalism, though, but a mix of opinion writing, poetry, and neurosis. I enjoy writing, but I don’t want to tailor it to the standards of journalism with their restrictions and formats. I really enjoy my freedom on Instagram.

But it’s a very personal story, and I often have to chase away the thought that so many people interact with the personal things I share. I feel like they know too much about me.

At the same time, I do understand that this borderline honesty and openness gives a face to this war and makes it personal: It’s not the news anymore but a certain young woman, Yulia, who is filming the war. And when people write to me from all over the world, “You know, I started following you on February 24, and I’m still reading your posts, and to me, you embody the war in Ukraine,” I feel like that’s the only way to really get people’s attention. After all, humans pay attention to other humans. It is difficult to follow mere headlines, numbers, and dry facts for a long time.

I don’t have any lifehacks or explanations on how I manage. I always thought my psyche was pretty flexible. Since college, I have worked like crazy. Then came the Revolution of Dignity, and I worked nonstop, too.

As for physical endurance, I have always been into sports. And that habit disciplines you and prepares you for all kinds of things. I always told myself that war was temporary. And I still live with that thought: that wars do not last forever. You sort of need to look after yourself and tune in to your own needs so you don’t burn out before the war is over.

Sometimes I have to stay on the position for a while. I believe that it takes time to make a documentary. To really capture the reality, the war, its essence, and form, you have to experience it. Out there, you are just doing what everyone else is doing. I have experience hiking, and I know for a fact that it’s going to be uncomfortable, so survival mode kicks in. You need to make sure you have water and food. You need to be as self-sufficient as possible and not pester other people or say anything like, “Oh, you have this warm sleeping bag. And I forgot to bring mine. Oh, you have this and that...”.

First, you act like a guest and inquire about the rules of the game: what is where, which shelter is the biggest, what do we have to do in case of an attack, an air raid, or other crap. You inquire about the safety rules for yourself and the crew. They show you everything, and you must take it from there.

But, of course, I can always get a return ticket: I haven’t signed a contract with the Ukrainian armed forces, and no one can force me to stay. If my crew or I decide it’s too dangerous, we can leave anytime.

Sexism does exist in the army. But I myself am not part of the army—I am someone who interacts with it and covers its work. At the Institute of Journalism, we had a professor whose name I can’t recall now. He told us, “Girls, you should never go to war. You’ll get raped on your very first day.” I was so angry when he said that. After 2014, I often remembered his comment. I’ve never had anything hardcore happen to me, but that doesn’t mean it couldn’t have happened to someone else.

Since 2014, many people have asked me, “What are you doing here? I wouldn’t let my daughter come here. You’d better stay at home. What does your husband say?” This happened not only in the war zone but also during the revolution. I am not the only one who has faced this kind of attitude. After all these years, I don’t have the energy to react to it emotionally. It’s not that I take sexism for granted—I just don’t waste my energy on it.

The number of women who joined the Armed Forces of Ukraine and the volunteer units, the Invisible Battalion advocacy project, professional women working as press officers—all these are changes I have witnessed.

Of course, my loved ones are very concerned about me, but they never questioned my decision and career choice. In the first years since 2014, I told my parents about my travels only after I returned from them. I just had that approach. Now I also tell them as little as possible about where I traveled and how risky it was. I don’t think they need to know that.

I always tell my partners right from the get-go that this is my crazy job, that I’m committed to it, and that I’m not interested in their opinion about what I should do. The ones who embrace this dynamic end up being my longterm partners, while those who can’t quite handle it tend to be part of more casual or short-term connections.

In the early years of the war, I had this strange feeling that it had been going on too long. I always say upfront that I love my life in Kyiv and like sleeping in my own bed. I know that there is the rear, and there’s the front. I must switch to other things and get positive emotions to recharge. I love hugging people who are not involved in war in any way, and they don’t trigger any reactions in me. Of course, there are things that irritate me and that I find inappropriate. Like Russian music blaring from the windows of luxury cars speeding through Kyiv. And I will always call people out on that and argue with them if they don’t understand it.

Once when I was photographing Yurko Prokhasko for Die Zeit, he and I went to the Field of Mars in Lviv, where the military are buried. He had this fancy red backpack of a Ukrainian brand. He turned to me as we approached the cemetery, this row of graves, and asked, “Isn’t this backpack too bright?” And we talked about what is too much during the war and where is the line beyond which one becomes too cheerful, too bright, too fancy. It seems to me that each of us has a different limit. And it doesn’t depend on how far or close you are to war or how much you have donated or given away. It’s highly individual.

But I have no problem going back. There’s always some kind of middle ground like Dnipro or Zaporizhzhia, where you can get a Coconut Flat White and still feel like you’re close to the combat zone. And then, after that transit city, you find yourself in the rear. I keep returning to Kyiv. I live here. It’s my home for now.

At the end of April, we visited one of the units in Bakhmut. A guy from the sniper team wearing a balaclava was sitting at his post with a rifle, and I took his portrait. And then he said, “Let me take your picture, too.” I stood right in front of him, and he took a picture of me.

When I returned to Kyiv and pulled up those photos, he looked like a person who was 200% poised and calm and kind of doing what he was supposed to do. He fit so well in the context. In all the surrealism of this war, he looked like he was an integral part of the big picture, while in my portrait, I looked like a scared sparrow. I looked so much like a civilian there, so much like a misfit in this image of Bakhmut, that this diptych became a tremendous revelation for me.

During this trip, just a few hours later, I went up the stairs above the snipers’ position and through the apartments in that half-destroyed building. I stumbled upon a door with those little notches parents often make to mark their children’s height on specific dates. My parents used to do that for me and my older brother, writing our names—’Julia’ and ‘Sasha’—next to the notches. I saw the same name, ‘Julia,’ on that door frame next to the notches. That just blew my mind. I knew that this girl lived there, that she was this tall, that she grew up like this, and that her room looked like this now. When I find myself in the cities, buildings, and apartments that were damaged during the war, it always takes me out of reality. At first, I would think, “Well, it got hit by a missile, and now it’s all fucked up.” But then I’d notice an element of the décor that would speak to me or resemble something in my life, and I’d be crushed because I’d feel like I had broken into someone’s home, someone’s life, someone’s room, someone’s bed.

This is a kind of reflection on what the war is. This is exactly the way it invades private life. It’s a very sticky, depressing feeling. I’ve thought a lot about where this girl, Julia, might be today, how big she’s grown, and what her life is like now.

Aerial reconnaissance officer. Call sign ‘Kafa.’ They joined the Armed Forces of Ukraine in the sixth month of the fullscale invasion. In civilian life, they studied at the Institute of Biology and Medicine of the Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv, engaged in political activism, and worked as a freelance journalist. In the first months after the invasion, they lived in Berlin.

When the full-scale war broke out, I realized that was my cue. I was born in Crimea, so I knew from my own experience what the ‘peace’ that Russia brings means. I began to prepare for service in the armed forces, completed special training, and enlisted. My motivation was simple: ‘Who else but me?’ I am a young, healthy, and physically fit person. I realized I had to reclaim what the occupiers had taken from me and millions of my fellow citizens.

As I prepared for military service, I read a lot, quit smoking and drinking alcohol, started running and building my endurance, and did some weight training. Back in Ukraine, I took courses in aerial reconnaissance and later joined the armed forces as a drone pilot.

Of course, everyone is worried about me. At first, my parents were really frightened that I might be killed, but now they have kind of gotten used to it and don’t seem so nervous anymore. My wife, partners, and friends who stayed abroad are very supportive. That gives me the strength not to give up.

Many people, civilians and military alike, who did not know me well or lacked willpower, told me, “Don’t go there. You don’t need it. Stay in Germany. Have children” or “Go and help sort the humanitarian aid.” I have been doing that since the first day of the invasion. It is important and hard work. But I wanted to do more.

In the army, everything depends on your team, on where you are, and on the upbringing of the men who serve with you. On my team, there was zero tolerance for disrespect or sexism. Now that there has been some staff restructuring, things are different. Often men make it clear, verbally or otherwise, that they know better. Sometimes that’s true, sometimes it’s not. After all, not all of them can even read the instructions on a first aid kit in English.

Sometimes you face certain expectations as far as daily tasks are concerned. Then I ask these people if their mother still mends their socks for them. That usually solves the problem (just kidding). It really depends on how they ask. I don’t consider myself a woman or a man, so I don’t shy away from any kind of work. I can clean the drain, fix a toilet tank, or fit a door. But not everyone can do that, and the guys are often surprised.

And then, men often try to feed me chocolate (and nothing else). I ask them if they want me to get diabetes or if this is just a tradition here. I lost 10 kilos during my time in the east, so maybe they are just trying to support me in this way? I don’t know.

Personal space is almost nonexistent here. Depending on where you are, your daily life can be different. We can stay in an open field—or in ‘luxurious’ conditions. You get used to all kinds of things. I’m a rather unpretentious person. I just need the warm sun, that’s all. If possible, I sleep at night; if not, I don’t. Very simple.

The same goes for personal care: if there is a will, there is a way. I knew what I was getting into. It’s very simple: You pour some peroxide on your blood-stained underwear, wash it in a bucket, and that’s it. It looks like people who have experience with monthly bleeding have a much easier time enduring all the hardships. Pain tolerance is much higher. Here, no one cares about your PMS or menstruation, just like in a normal job. It doesn’t matter if it hurts— everyone is running, and so are you (or driving... you get the idea).

The food is just normal. After I was admitted to the hospital, the doctors told me to take more collagen and vitamins, and there were only apples available, so I had to stop playing it fancy and just eat what they gave me. It’s a funny thing: I’m a bit neuroatypical and can’t eat certain foods because of their texture. For example, I can’t eat pickles. But they’re always served for lunch, and I’m always upset, the same thing every day. This is the kind of samsara I experience.

As for the uniform, it is not very comfortable, but my sisters-in-arms say that it’s actually much better now. I’m petite and tall, so I just took it in a little here and there, and that’s it. I do wear non-compliant boots, though. Talans (compliant military boots of the Armed Forces of Ukraine—ed.) are just not my thing.

There were so many things that it’s difficult to single out just one. The experience of successful operations, the attacks from which my comrades came out alive, the time spent with my brothers and sisters in arms, the meals we shared. How we would rest, and I’d read something aloud (a fairy tale or a poem that I would sometimes translate on the go), and how we’d enjoy incredible landscapes and events together. How we’d go outside to smoke, and the night would be filled with gunfire, but you wouldn’t care. Then you would tell a childhood memory or a dream or something about your life before the war—a life that many of us will never return to.

The mortality and the poetry, the joy and the sorrow, the pleasure and the grief that you can share with another person like you is the greatest happiness and the greatest treasure. I have had the chance to work with incredible people, real professionals who taught me a lot and showed me how to handle the equipment— and myself—in a critical situation. And how to handle the war that must be won at all costs.

26 years old

Press officer of the Armed Forces of Ukraine. Call sign ‘Athena.’

Serves in the Armed Forces since February 25, 2022. In civilian life, she worked as a journalist and PR manager.

In civilian life, I have worked as a PR manager and press officer for a member of Parliament. Before that, I was a journalist and copywriter covering economics, social life, and business. I also worked in PR for various organizations: a school, an architecture firm, and media.

On February 24, 2022, when the full-scale invasion began, I went to the military recruiting office, and the next day, I was able to enlist and received my military card. It was a spontaneous decision, without any backstory or training. The main motivation was to survive. At that time, it seemed that I had more chances if I was among people with weapons.

In the first days, nobody really did anything—there was just chaos. There were no special drills. But gradually, military service became systematic. Shooting drills and additional medical training began. On July 1, I went to the front, and on December 27, I returned, having stayed there for six months.

Now I am in Kyiv, but I’m still on active duty. In Ukraine, you can not just leave if you have been drafted. Therefore, everyone who has been drafted is on active duty. I used to work as a press officer, and now I’m in charge of communications for the Ukrainian Ground Forces.

My immediate family accepted my decision, but everyone, let’s say, outside my family, was against it. The first thing the military commissar said to me was, “Why did you come here, girl? You’d better go and cook for us.” Overall, I have been haunted by gender stereotypes throughout my service in the Armed Forces of Ukraine.

I’ve struggled the most with non-acceptance from the ‘real’ military, especially from the older officers who always said, “Girl, why did you come here?” Usually, you are judged by those who do not know you. Those who have known you for a long time treat you well, it’s all good.

At the front, there was an attempt within our unit to silently divide daily tasks along gender lines, but I firmly advocated for a fair distribution of responsibilities. I never cooked for or cleaned up after everyone. I said right away that it would not work for me. At first, the men did not want to do their part, but eventually, they did it all: they took out the trash, they vacuumed, they cleaned.

Here’s a story. I lived in a building with several officers. I am a junior sergeant, and I had a separate room. In the morning, I got up, made myself a coffee, asked if anyone else wanted coffee, and made it for them too. Then I asked my comrade Romchyk to wash the dishes, and

he said, “What do you mean? You want me, an officer, to wash the dishes?” I yelled at him, told him to shut the fuck up, and he not only washed the dishes but took out the trash. It’s not like he hired me to do it, right, I was not his mother or his sister, and I was in no way obligated to clean up after him. This sounds pretty brutal, but the guy changed his ways and started cleaning up his mess.

Unfortunately, some men are just too spoiled: their mother or wife has always cleaned up after them, done everything for them, and cooked for the whole family, so these men don’t feel like doing anything themselves. And they need to be disciplined. If a woman does all the chores by herself and says, ‘It’s okay, I’ll help, I’ll cook,’ and then takes on some more, she’s sure to get pushed around. You have to set your boundaries.

One of the biggest problems is the cut and size of military uniforms, which are tailored to men. For example, there is no size that fits my height, so all the pants are cut too high for me. I only got one uniform, and it wore out over time, so I had to buy another one just to have a change of clothes, especially during deployments. All of these uniforms are too big, and I either have to take them in or belt them up, which is pretty uncomfortable.

It’s still tough for me. It’s not fun, to be honest. But I made the decision, and I had to adjust to it. It’s really difficult to create a kind of sliding scale and say it was hard up until that moment, and then it became easy. It’s just hard in general, but you can get used to anything, and that’s a good thing.

When it comes to living conditions on the front line, it’s probably hardest when you’re being deployed and have to pee outdoors, which is very uncomfortable. For men, it’s much easier, but for women, it’s a problem. I never lived in the trenches. I only stayed in the woods during exercises, but even then, I slept in a car or a tent.

Otherwise, we always lived in the headquarters, and the conditions were quite alright. For example, in the basement of a large enterprise—we brought beds there from elsewhere. People would just roll out a sleeping bag or a mat or a mat and a sleeping bag and sleep there. Almost all the buildings where I stayed had a toilet—basically a hole in the ground—and a shower. Sometimes the shower was outside, and I had to walk to it. It was certainly ‘fun’ when I was the only woman in the HQ and would walk back across the yard with wet hair or had to take all my clothes with me to change so no one saw me half-naked.

As for periods, I just take a larger supply of hygiene products. I use sanitary napkins and have had no problems with them. Of course, women must buy them themselves because, just like in civilian life, our employer will not buy hygiene products for us. If we’re being deployed, we just have to take everything with us. I always keep a threemonth supply.

I haven’t had have any problems with food. The food I got was fine, and I could always buy something else if I wanted.

You get used to everything, but not having privacy takes its toll on you. There is no way to spend the whole day alone because there’s always someone in the same building, and you are always working with others. It’s tough. It’s like you’ve been in a summer camp for months, and you don’t get to go home.

At first, it felt strange to go back from the front to the military service in the city in the rear because everyone looked so happy, which was surprising. It also took a while to get used to missile attacks because it’s usually artillery shelling at the front, and you learn which shells make which sounds and you know what is going on. It felt more familiar to me than, for example, Shahed drones or missile strikes.

And then there was something else—clothes. At first, I just wore baggy clothes, just like in the Army, not to draw too much attention to my appearance. But then I found some better-fitting clothes I used to wear to the office. However, I still don’t go to bars or parties. I lead a more private life because I’m no longer really interested in those things.

29 years old

Aerial reconnaissance officer. Call sign ‘Mavka.’

Has been fighting in the war since September 2022. Before the full-scale invasion, she worked as an SMM manager and librarian.

My husband went immediately to the military recruiting office on February 24. I stayed behind with my two dogs and the grab backpack, which I had packed in advance. I spent one night with the dogs in the subway. But then I realized that fear was not an option. I wanted to do something. There was no way to know what would happen next. We felt like it was almost over, but we kept fighting with the last of our strength. And if you think these are your last days, you don’t want to live in fear and die as a victim. You want to act and do your best to change the situation at least a little bit, to fight until your last breath. That’s why I immediately started to volunteer, involving all my friends who stayed in Kyiv, and not only them. These were very active, intense months.

This went on until May. I volunteered without stopping, from dawn until dusk and again until dawn. One of my fellow volunteers went to Chernihiv when heavy fighting was still going on to deliver the humanitarian aid we had collected and evacuate people. At that moment, the volunteers’ convoy was hit by a missile, and everyone was killed. It was the first death of someone I knew personally, and I was not prepared for it. I knew that the soldiers were in danger and could die, and I prepared myself mentally for it. But I was not prepared to lose one of the volunteers who had been with me since the first days of the invasion and with whom we had been through so much. It was a very painful death for me, the first since February 24, and it affected my actions going forward. Immediately after it happened, I felt that I really wanted to personally avenge his death.

I started thinking about how I could enlist in the army. I searched for training courses, but there weren’t many available back then. My first training started at the end of May, and it was just basic tactics: how to

hold and use a weapon and how to maneuver in small groups. Then I signed up for a private aerial reconnaissance course and also took a course in tactical medicine. I attended everything I could find while I was still a civilian. I signed up for all these trainings, not realizing that it would result in a three-year contract. I told myself that there was a war going on in my country, so I had to be able to do everything. But it looks like, subconsciously, I already decided that I was going to join the military.

I began my military career as a member of a volunteer unit in September 2022. I was there until February, participating in combat operations in the Luhansk region and later in Bakhmut. After that, I waited quite a long time until I could finally sign a contract with the Armed Forces of Ukraine.

It’s been hard for my parents to accept my decision. They are very worried, but they are also proud of me. If they had had the opportunity to keep me away, they probably would have used it. But I am very grateful to them for supporting my decision and not trying to stop me in any way.

And my husband and I are adults, and we know that no one can forbid anyone anything. How could I not let him go to the recruiting office on February 24? Each person makes their own conscious decisions for themselves. It was hard for him to accept my decision, but about six months later, I also heard him say that he was proud of me, and it was such a weight off my mind. I know it’s not easy for him when he and I go on combat missions; of course, he’s worried. But I was just as worried when I had no way to contact him during the Kharkiv offensive. We are worried about each other, naturally, but we know why we are here and what we are fighting for. We really want to return to our civilian lives that we had before the war and loved so much.

I still remember my first visit to the military recruiting office. They invited me into the room and told me, “This one, this one, and this one are single. Choose the one you like better.” The message was that a woman in her right mind could not go to the recruiting office to sign a contract—something must be wrong with her. And if a woman was going to the army, she was certainly hunting for a husband. It was very uncomfortable for me. I thought, okay, I’d been mentally preparing for something like this, anyway. The next time I went to the recruiting office, it didn’t happen, though, because there was a female commander, and she wouldn’t let anything like that happen.

In general, I meet very few women on the front lines. However, in the volunteer unit, I had sisters-in-arms, even two. They were also in aerial reconnaissance. One of them was killed last year. And so her name was added to the list of people for whom I must seek revenge. It was an extremely challenging time for me. I never imagined that one day I would have to carry a coffin. It was a very strange feeling to see this young woman’s parents and realize that they were looking at me as if I were their daughter. Because Vlada was the same age as me. I knew that any of us could have been in her place.

Of course, in the army, you face prejudice everywhere when you first get there. They look at you as some kind of dead wood that they don’t know what to do with. They think you are the weakest and know nothing about military affairs. Every time you join a new team, you have to prove yourself and be not just equal but better than everyone else so that you are perceived as equal. This is not easy, but possible.

There was this terribly unpleasant situation: before we went to the UK for training immediately after the contract was signed, we spent some time in Ukraine waiting to be deployed. We were only five women out of 200 people, and one day all five of us were summoned by the command. So we went and saw that everybody had arrived: the platoon leaders, the company commander, and some other officers. And they started mansplaining to us how we should position our legs; about the anatomy of our bodies; that we would be deported from Britain if we got pregnant; and how we should deal with our hormones. And other things like that... We just stood there and got mud thrown at us. I was not the only one in the room who was married. So I realized we had to listen to all that just because of our gender.

Later, during the exercises, I was appointed squad leader. I was supposed to be responsible for 15 soldiers. When they first saw me and learned that this ‘girl’ would be their squad leader (what’s more, I had dreadlocks at the time), they burst out laughing and said they wanted to transfer to another squad. How could it be that I was chosen out of 200 people to be a squad leader, and they, so unlucky, happened to be assigned to my squad? But just a week later, they realized it was not a problem. We even became close friends. Moreover, we even became the best squad. And they kept saying they really wanted me to be their commander in the future.

I know that in the army, too many men think that women go there looking for men. You have to keep setting boundaries and showing your true motivation. You have to set yourself up from the get-go so that you are not perceived as a ‘girl’ because you hear that word, ‘girl’, all the time. That is, there are no ‘women’ in the army. You have to constantly assert yourself and prove yourself as a warrior, showing your strength and character. Sometimes you even have to bare your teeth too much, because otherwise you will be seen as a ‘girl.’

The military uniform is another story. You are given two pairs of men’s underwear. Obviously, they don’t fit you, so you just pass them on to your husband. I have wide hips but a narrow waist, and the pants (men’s cut, of course) don’t fit me very well but are still more or less fine, while the jacket is huge. And when I asked the woman who gave me the uniform if I could keep the pants but get a smaller jacket, she looked at me like I was a fool and said, “Girl, it’s not an army surplus store for you.” And I said, “Okay, okay. Sorry for a stupid question.” I walked away without saying another word because I realized I would have to take care of these things myself, too. It was clear that I could not wear this uniform—it had to be fitted.

In Ukraine, however, there are wonderful volunteer initiatives that make women’s uniforms, and they are a great help. They make really high-quality uniforms that don’t fit like a sack, and you can sit and walk comfortably wearing them. I understand that some steps are already being taken to ensure that that is the case at the level of the Armed Forces, and even some samples have already been approved. So I really hope that this uniform will be offered by the Army this year or maybe the next one.

It took about three months before I finally decided to join the military. I had to fully take in all the things that could happen to me: that I could die, that I could become disabled, that I could get a different level of disability. I had to figure out what my next steps should be if something happened to me. I tried to run through as many scenarios as possible about what could happen to me and whether I was prepared for it. I studied psychology, and this one book, The Armored Mind by Kostiantyn Ulianov, helped me a lot. I learned what would happen to me in war and what feelings would come up so they wouldn’t scare me or catch me off guard once I was there.

So I can’t say that anything seemed super difficult when I arrived. On the contrary, I always prepare for the worst, so what happens doesn’t seem so bad to me. I always have my small backpack with me with everything I need, so I will survive being left in the middle of nowhere for a week. I have everything in there to be self-sufficient.

I can’t say it’s unbearable, or I’m uncomfortable and wish I could go home. I’ve never felt that way before. But at the same time, for example, I always bring some candy bars for myself and my comrades because I know it wouldn’t occur to them and they would just sit there hungry, and that makes them feel good. In the winter, I always had this water heater bundle with me. So if we had a break or the weather was bad, and we couldn’t fly the drones, we could make tea to warm up a little bit. And I did that not only for myself but also for my fellows. It made our lives a little easier and more comfortable. And it didn’t take much effort.

As for personal care, again, I always have everything with me. I have not lived in a trench for as long as a week. My job is such that I could go there for a day and then return to relatively comfortable conditions: That could be a destroyed house or something else where I could at least get some water from a bottle and take a dry shower. A dry shower was a big help. We were in Bakhmut, and there was no water there, not even drinking water. It’s good when small solutions like this are available to make your life better.

My diet is a bit special: since I don’t eat meat, the dry rations of the Ukrainian armed forces don’t work for me. Again, it’s a matter of being self-sufficient. I always have a small bag of food with me. I eat freeze-dried foods that take up little space, and also some bars, nuts, and the like. Even when we go on assignments, I take everything with me. So I always have enough food for a week, and if it’s longer than that, I can always come up with something. Every Animal, a nonprofit organization, helps me out occasionally. They send vegetarian dry rations to the military, and that really makes a difference.

Other armies around the world provide vegetarian meals. And there are quite a large number of vegetarians among our military as well. Not very many, of course, but there is a certain percentage of these people. And since they are risking their lives to join the army, it would be nice if the government could at least support them with vegetarian food. But as long as that’s not the case, you must find temporary solutions. You just have to take care of yourself.

I remember one day in February when I was still in Bakhmut in the morning and already in Dnipro in the evening. There I met my husband. We decided to go to a restaurant to eat something. And I felt so bad when we went there because the music was blaring everywhere, there were many young people on the street, both men and women, and all the restaurants were so crowded that we couldn’t even find a free table. Everyone was drinking and partying, and the music was so loud that, at some point, I felt so uncomfortable and hurt that I really wanted to go back. It was as if I had arrived in another country where there was no war at all. And that was just Dnipro. I realize that there’s even more of this in Kyiv. In such moments I feel very bad, and it takes a while to get used to it.

On the other hand, I understand that the war has been going on for years, and people have to live their lives. But sometimes I think it’s all too much. Too much fun, too much of this…. Many people don’t feel the pain anymore. I don’t know, maybe not everyone has lost someone in this war, so they don’t feel that pain. Someone will do that work for them.

Volunteer and director of the BON charitable foundation. When the war broke out in 2014, Oresta was living in Paris but decided to return to Ukraine and volunteer. She is particularly involved in providing supplies to the military on the front lines.

When Russia began its aggression against Ukraine in 2014, I was 24 years old. At that time, I had already lived in Paris for six years, studying and working as a model. When the Revolution of Dignity began, I was on vacation in Kyiv. The beating of the students was the trigger for me. That’s when I started to get involved socially and as a volunteer.

Why did I find this important? I lost my father at an early age, and my mother struggled a lot. I remember everyone who helped us back then very well, whether with advice or donations of clothes. So the situation that many families are in now after they’ve lost their homes or where children have lost their fathers is all too familiar to me. Perhaps that is the reason behind my strong empathy.

I learned that I was a ‘volunteer’ in eastern Ukraine in July 2014: that’s what I was called at a checkpoint when my team and I were delivering relief supplies to the Aidar Battalion. In fact, we did not even realize it was a real war at that point. After being told for the first time that I was a volunteer, I decided that the right thing to do was to start a charity.

So in 2015, the BON charitable foundation was launched. It runs peacebuilding charity programs and cares for civilians. The charity has offices in the United States and Lithuania. And the BON NGO, where I currently invest my best efforts, provides assistance to the Armed Forces of Ukraine.

We would go to the front as soon as the relief supplies were collected. Sometimes the logistics would get disrupted, and we’d have to go twice a month. Not only did we deliver relief supplies, but we also took the time to talk to soldiers in person and ask them about their needs—the cell phone connection with them was often unstable.

During ATO, just as today, I tried not to distract the soldiers with my presence because it was a big responsibility. We tried to limit ourselves to one day on the front lines and visit several positions in one go. So, I visited different sectors on each trip. I was not affiliated with any particular units.

I systematically helped the Armed Forces until 2016. Now I am looking forward to the moment when ‘2016’ is here again, and the military will not need anything because they will be so well-equipped that I won’t even have access to them.

Until February 2022, volunteering was my hobby, and I worked full-time in business.

I started preparing for the invasion as early as November 2021. However, I had not planned to expand the activities of the foundation so much—we could not foresee the scale of the aggression and the areas of work. In the fall, we began fortifying dugouts and delivering sand and generators. I thought I was ready. But no one, not a single country in the world, would have been prepared for such terror. And the front line happened to be in my homeland, in Kyiv. We started to set up a headquarters.

I travel to the front often—usually two or even three times a month. The length of the trips depends on the intensity of the shelling. Although I had planned it differently, my first trip in 2014 lasted three days because I simply could not go back. I recently returned from the Donbas, and this time, I was able to do everything I had planned because the guys were a bit less preoccupied in those few days— there was a lull in the fighting. We were able to hold all meetings and settle all matters within two days and three nights. At the moment, I am coordinating the units, analyzing the needs of the neighboring positions, and deciding how we can optimize the exchange of useful but not strategic information.

Maintaining composure and relative safety is what I can and must provide for myself. Staying completely calm and keeping my loved ones updated. However, keeping them guessing is often helpful, too. No one tries to talk me out of going to the war zone because they don’t even know I am going there. I always try to go there alone unless I need to give a ride to a soldier. That guarantees my safety, and I don’t have to rely on anyone. I know where I’m going, the units have been informed about my visit, I have certain tasks, and they expect me.

My boyfriend is a foreigner, and he knows very well what is going on and even comes to visit me, although this is not his war. He comes to Ukraine so that I don’t have to struggle with making it to Europe when it’s not really necessary. Going to the east of Ukraine, to the front, is much easier for me than going to Europe.

It all depends on where you are. In some places, you can leave for a neighboring town in due time to return in the morning, continue working until evening, and then go back to civilization. Elsewhere, you have to spend the night in a dugout. I can’t say it differs that much from the conditions in which the residents of Kyiv found themselves: Sometimes, we, too, had to sleep a few nights in damp basements. Last year, I set up an underground room in our foundation’s office for volunteers to work and spend the night with their families and pets. Once, during the heavy shelling last fall, we spent four nights in a row there without going out.

Sometimes you get stuck in a dugout for three days without water, but even that only happens when the shelling is so heavy you literally can’t lift your head. I’m not an adrenaline junkie and don’t like getting into those situations, but it happens. I have to say, though, that in these nine years of war, our guys have learned how to arrange fairly comfortable conditions underground. They have a lot of know-how. Of course, I’m not talking about the guys on the very front line who are forced to lie in ambush or mobile units like those in Bakhmut who don’t have time to even sleep, let alone wash.

There are no problems with food in the military. Everything is fine. That’s why I like to visit the guys so much. They always offer me some delicious treats.

There must be some sexist attitudes out there, not just on the front lines but across the country. However, I have a tight social circle, so I have not faced it. I don’t think the people I work with would ever think about something like that.

Many people assume that it is a personal interest that has driven me to volunteer for so many years. But it’s not—no one in my family serves in the army, and I’ve never had a fling on the front lines. I just believe in what I’m doing and feel that I can offer my professional support today and be useful in that way.

23 years old

Commander of an FVP strike drones unit. Call sign ‘Tsunami.’ Joined the Armed Forces of Ukraine in April 2022. Before the full-scale war, she worked in marketing.

I graduated with a bachelor’s degree in logistics just before the full-scale invasion. Before joining the army, I worked in marketing and did data verification.

As soon as the invasion began, I considered joining the army, but I took my time thinking about it so it wasn’t an impulsive decision. I started looking for opportunities where I could be useful and do no harm. And then, on April 20, I enlisted.

What was my motivation? Over the past year and a half, I have asked myself this over and over again and received different answers. Anger, patriotism, the desire to win— that’s for sure. Maybe I was also trying to prove to myself that I could do it. And then, I did not really have a career at the time, and I didn’t like my job. So I decided that if I didn’t know what I wanted to do, at least I could do something useful.

I did not know much about weapons or combat tactics, so I thought a more administrative job would be better for me. Right about that time, I met a military officer looking for an assistant, to put it in civilian terms. He needed someone to prepare reports, file inquiries, and systematize certain procedures. And I had a degree in logistics and experience working with data.

Later, my commander began to assemble a separate unit focused on aerial photography and photo and video reconnaissance: quadcopters, drones, and other technical equipment for reconnaissance, such as aeroscopes, electronic intelligence, and so on. That’s how I ended up leading the FPV kamikaze drone division. We worked with these drones for about six months, destroying the enemy. As the commander, I undertook tasks, received and identified targets, monitored the handover line, and established processes.

All the knowledge I have acquired in my civilian life has proved useful: the ability to quickly figure out how to work with this or that device, communication skills (sometimes you do have to stand your ground), and physical and mental resilience. I used to work as a switchboard operator for a private security firm, usually 24 hours on, 72 hours off, and this experience also proved useful because in war, there is no fixed work schedule.

If I start talking about sexism now, our conversation will go on forever. I am confronted with it every single day as long as I wear the uniform or use certain military attributes like a military truck. For example, I’m driving a green pickup truck and wearing civilian clothes during exercises. So I am ‘a soldier’s wife,’ ‘a volunteer driver,’ ‘a general’s granddaughter’—anyone but a military officer.

I often get insulting questions like, “Why did you come here? To entertain men / to please their eyes / to find a husband?” Sometimes the men say, “All right, you can go now, we can handle it on our own.” And then, I wonder if I should take advantage of this opportunity. On the one hand, sure, I can leave, but on the other hand, I’m so sick and tired of these jokes. But maybe I should actually take the opportunity to rest a little bit. Sometimes I do just that.

Or the men would come and say, “You go to the commander, Ania. He will listen to you and do what you say.” And I know I’d better go because it’s better that way for the whole unit. Some think that women should never show their anger and curse. Others can not help but ask, “And when will you have children? It must be hard for you to wear this plate carrier, right? How are you going to hold the weapon? Women are not made for it. What, you can drive a car?” In the army, a woman behind the wheel triggers even more surprise than in civilian life. So I ask them:

“Does your wife drive a car?”

“She does.”

“Stick shift?”

“Yes.”

“Then why can’t I do it? I’m just like her.”

“You bet.”

I mean, sometimes they act like sexists without realizing it because they never thought about it—or never thought about pretty much anything. I can give you so many examples like that. I could write a book about it someday.

However, I serve in a great unit, and our commander is not sexist. He asks a lot of both women and men, and he has never humiliated us or given us separate tasks. I face sexism only outside of my unit when we have to work with other people. One time when we returned to the rear, a guy came up to me and said something like, “Ha, girl, ta-ta-ta.” And I was standing there with full ammo, unloading my assault rifle. When he saw that, he said, “Oh!” and walked away. He was surprised.

I am direct, assertive, and snappy, so I usually get my way. Sometimes I just cite the facts or the law. For example, are you saying that a young woman can not smoke? “The law of Ukraine does not forbid it, and I’m 18,” I say. Or they ask, “Why did you join the army?” After a whole year of explaining the same thing to everyone, I just say, “It’s not forbidden by the law of Ukraine.” And that’s it.

However, I do not feel equal in a team of men. Sometimes I feel sad that I lack physical strength and endurance, and that the menstrual cycle impacts my energy level. And it’s very nice when men understand that this does not affect my professional duties, though, and respect that. But the overwhelming majority just say, “Then why did you come here?”

I think we have excellent conditions considering the war. We do not live on the line of contact because we have a lot of equipment that needs to be recharged. It is best if we have access to electricity. Of course, sometimes we use power generators. But fuel is money, and you do not get much of it.

When you first arrive in the sector, finding more or less comfortable accommodation can be difficult. Sometimes you sleep in the car, in the street, or in the basement. We look for houses: in the first line, usually in the second, sometimes even in the third, depending on the area, because in some areas, a distance of 100 meters from the contact line means one thing, in others, something completely different. The houses are also very different, it depends on what you can find. It can even be a shed of some sort. I remember we slept in a leaky firehouse outside of Izyum the first few days. I slept in a sleeping bag on a mat on the floor, and it was so cold.

Situations vary, but people adapt to everything and accumulate tons of things over time when they get a chance. Of course, not everyone gets it. I have seen some people live with just one bag while others drive around with a whole van full of stuff. Recently, we have been sleeping in sleeping bags on the cots. You can not always set up your daily life to be super comfortable, but with time it is possible.

Sometimes we are lucky enough to find more or less decent conditions, with access to water and electricity, where you don’t have to hook up wires to utility poles. Recently in the Donbas, we even bought a boiler and a washing machine, which was absolutely wonderful. No luxury, but quite comfortable. We even had electricity. So living conditions have been pretty good lately. I can’t complain.

Whether you have privacy depends on the situation. Sometimes you

can find a small room and live there alone. But sometimes you live in a huge room of 100 square meters, all sleeping together on the floor, and at night someone hugs you, and you just snap back and tell them to stop. That’s what happened to me.

The worst thing about daily life is that you can’t wash for a long time. Your whole body itches, and your morale sinks to the bottom. Wet wipes are the most precious thing I have. Sometimes I tell my girls, “Let’s go ‘wet wipes shower’.” Once, we arrived at the infantry post, and the men said, “We’re celebrating our 70th day without a shower.” That’s when I realized that my life was not so bad.

When it comes to feminine hygiene during periods, I usually wear sanitary pads because they are the easiest to change. If it’s more or less warm outside (by ‘more or less warm,’ I mean April through October), you can heat up some water. I call this ‘tactical washing’—when you wash the parts of the body that need it more than, say, your back.

I recommend that women who have just joined the army should stock up on wet wipes, preferably baby wipes. They should not be shy in front of men but be open about their needs and menstruation, so the men know there can be different situations. You can just say, “I’m stepping around the corner to freshen up. Could you please make sure no one is coming?”

Sometimes you worry that you do not have a space to do that. You have to create that space. At first, I was a bit embarrassed. Now I am surrounded by quite a few women who can help me with that, but I hardly saw any women for four months.

I have a lot of underwear and socks—I can’t even count how

many there are, but they take up quite a bit of space in my bag. I have a big bag of clean things and another big bag of dirty things. When I have time, I wash and dry everything, and then I do it again and again. However, if I don’t get the chance, I just throw them away and order new underwear. Sometimes it’s easier to go to the Nova Poshta store, pick up a package of new undies, and throw away the dirty ones than to wash them. I’ve done that many times. Fortunately, I have no dietary restrictions. I eat all kinds of things and anything I like. The army would usually supply cereal, eggs, some meat, sometimes maybe vegetables, I’m not sure. When we worked in the Bakhmut area, we could make a run to the grocery store. The Donbas is used to war, after all; the people there have gotten used to it and live their lives. The prices? Of course, there’s been some price gouging, and sometimes more than ‘some,’ but we can still afford it. I have a mini-cooker and a hot plate. If there is no electricity, we can use a gas cylinder. Often they send us dry rations, foreign or Ukrainian-made, which are also quite good. Taking them with you when you go on missions is especially convenient.

There were also gas stations where we could eat out. Of course, these were closer to the rear or even in the rear. In the area of Izyum, of course, there was no such thing. There were no signs of civilization, maybe a village store—that was it. In the Donbas, it was easier because people there had gotten used to living during the war. I think that’s the reason. Restaurants were open, some canteens, stores, and even wax studios. So I could go for hair removal almost every month for the last year and a half. The commander let me go.

Physically, I find it easy to maintain that communication. Someone would say, “You tweet so much.” And I would respond, “Okay, I’ve got a Starlink in the trenches, so what?” I’m sitting there listening to the sounds of explosions, I can’t get out of the dugout, so what should I do? Should I post nothing and just suffer? No. I’d rather text my mum, post on Twitter, read something, or watch a video on TikTok.

Emotionally, I have stopped communicating with several of my girlfriends simply because I just can’t take their problems seriously but, at the same time, don’t want to belittle them. So it’s easier for me not to keep in touch with them. My parents are fully supportive. They are wonderful. I don’t talk to some of my relatives, though; I feel uncomfortable. It’s just that I’ve been in situations where you realize that your life is not merely the only one—it’s your last. And I don’t want to waste it with feelings I don’t like and communication I don’t need or want anymore.

When I’m in the cities in the rear, sometimes I feel like I’m eating in a restaurant for the last time. I feel like I just have to eat, even though I’m already full. I’m overindulging, that’s the right word for it. I have a normal attitude toward people who go on with their lives but still find time to contribute to the war effort: volunteer, donate money, or do charity work, especially for orphans, refugees, and wounded people who need help. The war will go on for a long time. And I’m afraid we haven’t even seen half of it yet.

20 years old

War correspondent, fixer, producer. Before and at the beginning of the full-scale invasion, she worked as a photo correspondent for Suspilne Odesa.

I was born in Bessarabia. My grandmother from Makiivka was the daughter of a miner who was also a photographer. Throughout my childhood, we traveled to the Donetsk region: Donetsk, Makiivka, Luhansk. Donetsk region was where I made my most cherished childhood memories. Grandma was also into photography. When I was a little girl, she would always bring a Kodak camera with her. When the war broke out in 2014, my family told me in the summer, “We can’t go to the Donetsk region.” And they started explaining to me what was going on. I was only twelve years old. That was one of those moments when you are still a child, but an awareness rises in you. At that moment, I realized that in the place where I had made my most cherished childhood memories, the war had broken out.

When I was about sixteen and started photography, I realized I wanted to be a journalist. Two years later, I enrolled in the journalism department, and then I felt that I wanted to develop in this field and become a war correspondent. Somehow it was just deep inside me, it was all growing in me, with me. And maybe each of my trips there, to the Donetsk region, to the front line, shows my desire to give back so that one day I can return there, to the place of my most cherished memories. It’s like something that was snatched away, that you forgot, that you lost, and that you seemingly can reclaim, but at a very high price. Sometimes I feel sad, but I keep working, and I know that as long as it’s in me and I have that motivation, I should keep going.

When the full-scale invasion began, I was a photojournalist for Suspilne Odesa. I worked mainly in the Odesa region, filming the sites of missile attacks. I traveled around all the time, and I knew what to expect. But when I wanted to join a group

traveling to the Mykolaiv and Kherson regions, the editor said I had to get written permission from my parents. But at that time, I was already nineteen years old. So I realized that each of us should go our own way.

Then, quite by chance, I found a job as a fixer and started traveling to the front line with foreign journalists as a fixer and producer.