COMMODORE Simon Currin

VICE COMMODORES Daria Blackwell

Phil Heaton

REAR COMMODORES Zdenka Griswold

Fiona Jones

REGIONAL REAR COMMODORES

GREAT BRITAIN Carol Dutton

IRELAND Alex Blackwell

NW EUROPE Hans Hansell

NE USA & ATLANTIC CANADA Janet Garnier & Henry DiPietro

SE USA Greta Gustavson & Gary Naigle

W COAST NORTH AMERICA Liza Copeland

CALIFORNIA, MEXICO & HAWAII Rick Whiting

NE AUSTRALIA John Hembrow

SE AUSTRALIA Scot Wheelhouse

NEW ZEALAND & SW PACIFIC Viki Moore

SOUTH AFRICA John Franklin

ROVING REAR COMMODORES Nicky & Reg Barker, Steve Brown, Guy Chester, Thierry Courvoisier, Andrew Curtain, Bill Heaton & Grace Arnison, Lars & Susanne Hellman, Alistair Hill, Stuart & Anne Letton, Pam MacBrayne & Denis Moonan, Simon Phillips, Sarah & Phil Tadd, Rhys Walters, Sue & Andy Warman

PAST COMMODORES

Editorial 3

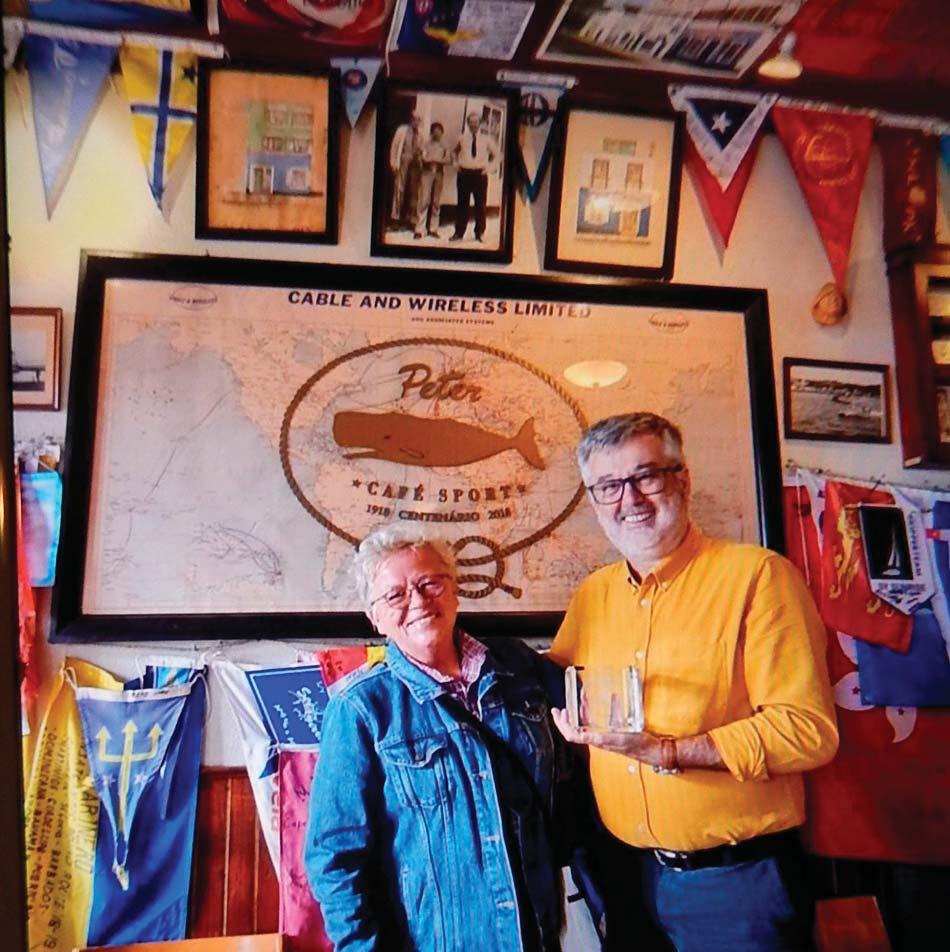

Sailing Around the World Alone, Part 2 4

The Middle Way up the Atlantic 20

Dustin Reynolds

Patrick Marshall

Capsize! 33 Anthea Cornell Stock

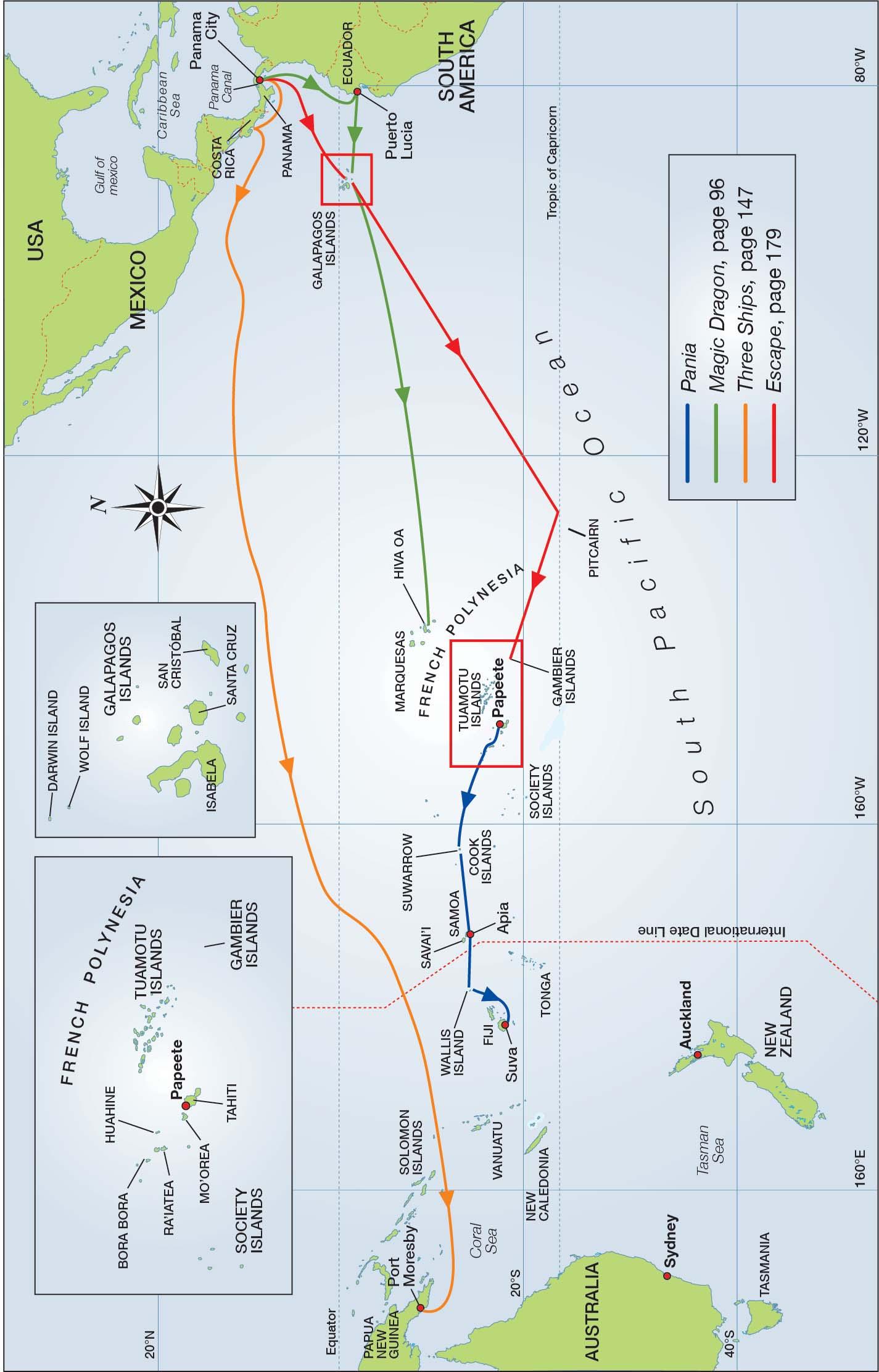

Sailing Pania ~ Island Hopping...

Lambert

Blauwasserbriefs 52 Susanne Huber-Curphey

Why Japan? 67 Peter and Ginger Niemann

Contrasting Passages 79 Rev Bob Shepton

Book Reviews 89 Heavy Weather Sailing, Well it Seemed Like a Good Idea, First Aid at Sea, Norway, Principles of Yacht Design, Quirky History, Stress-Free Engine Maintenance, Superyacht Captain

Frances Griffiths, Sara Hough, Adrian & Clare Richards

Tom & Vicky Jackson

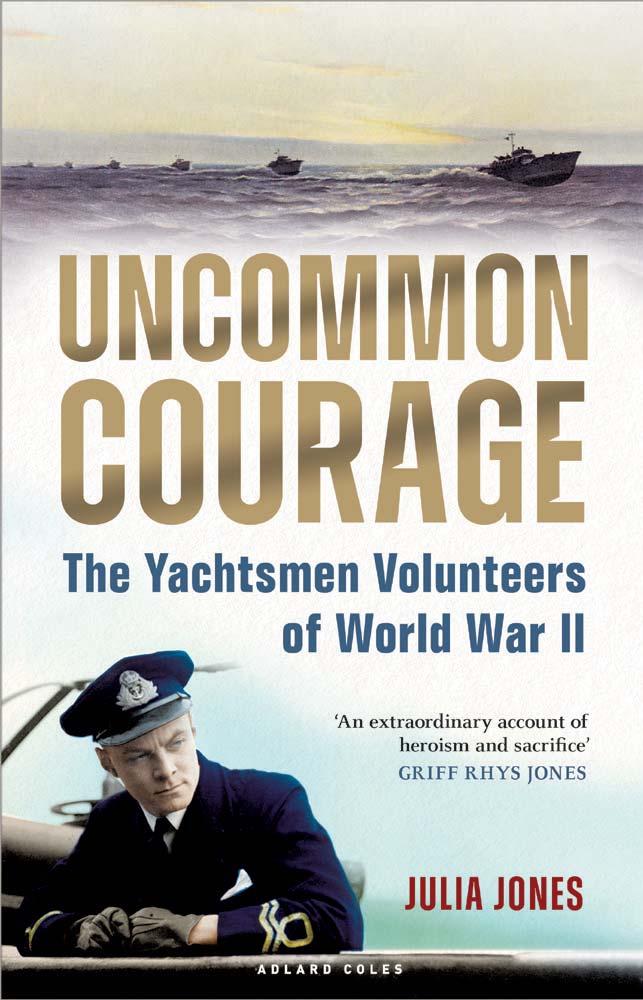

Yacht Design, The Complete Ocean Skipper, Louise Adventure, Uncommon Courage, Germany and Denmark

The information in this publication is not to be used for navigation. It is largely anecdotal, while the views expressed are those of the individual contributors and are not necessarily shared or endorsed by the OCC or its members. The material in this journal may be inaccurate or out-of-date – you rely upon it at your own risk.

I often wonder what on earth to write in my Editorial, but this time there are several things I’d like to say. The first, of course, is to thank everyone who’s contributed an article to this issue, particularly those who write excellent English despite it not being their first language. In his Commodore’s e-mail for November Simon reports that members dialled in to the recent GC meeting from Ireland, the UK, USA, Canada and Mexico, with apologies recieved from mid-Pacific, rural South Africa and Norway. Are we the most global club for our size in the world?

Thinking of our global reach and responsibilities, an article in a recent Flying Fish mentioned concealing fresh produce when entering one country from another (with which it shares a long land border), despite this being prohibited by local law. Such practices are not endorsed by the OCC, and members are expected to follow the guidance set out by the Club’s Governance Committee at www.oceancruisingclub.org/About-theOCC. This states: ‘OCC Members are cruisers who comply with international, national and local laws and regulations; respect communities, their customs, the environment and other people including other Members; demonstrate honesty, fairness and courtesy; and are responsible and accountable for their actions’.

Closer to home, many members will be aware that past Club Secretary Anthea Cornell Stock died in late September. Her obituary starts on page 215. Separately, on page 33, read her own account of being aboard a capsized catamaran back in 2001. Anthea joined the Flying Fish proof-reading team six years ago and demonstrated an eagle-eye for both typos and grammatical errors, as well as occasionally throwing light on people and events from decades ago. I shall miss her. While it would be impossible to replace Anthea, her loss still leaves a gap in my proof-reading team. Proofs can be sent out and returned either as PDFs, hard-copy or a combination of the two, so it would be good to hear from members outside the UK. E-mail me on flyingfish@oceancruisingclub.org if you’re interested.

There are some stunning photos in this issue and many arrived just as you see them. Others, however, required considerable work. Flying Fish doesn’t ‘do’ sloping horizons, so please try to hold your camera/phone level as you press the button. While horizons can usually be levelled in PhotoShop, it takes time and often involves cropping off part of the photo. I know how difficult it is hold things level if you’re grabbing a quick pic on a violently moving boat, but when all is calm and peaceful please do make that extra effort! Similarly, while fish-eye and other ‘distorting’ lenses can add interest to photos, they’re best avoided for general use. If using one at sea, try to keep the horizon near the centre of the photo. We all know that the earth is round, but not that round!

One last thing ... the DEADLINE for submissions to Flying Fish 2023/1 is Wednesday 1st February. While I can often cut a bit of slack it can’t be guaranteed, so get those submissions to me early if possible. Many thanks!

(New members should either visit thesinglehandedsailor.com/ or read Dustin’s backstory in Flying Fish 2022/1 (online at oceancruisingclub.org/Flying-Fish-Archive) to learn how he came to be in Indonesia with very limited funds and a boat beset by more than the usual number of problems.

Following his return home in December 2021, Dustin was awarded the Barton Cup for his circumnavigation.)

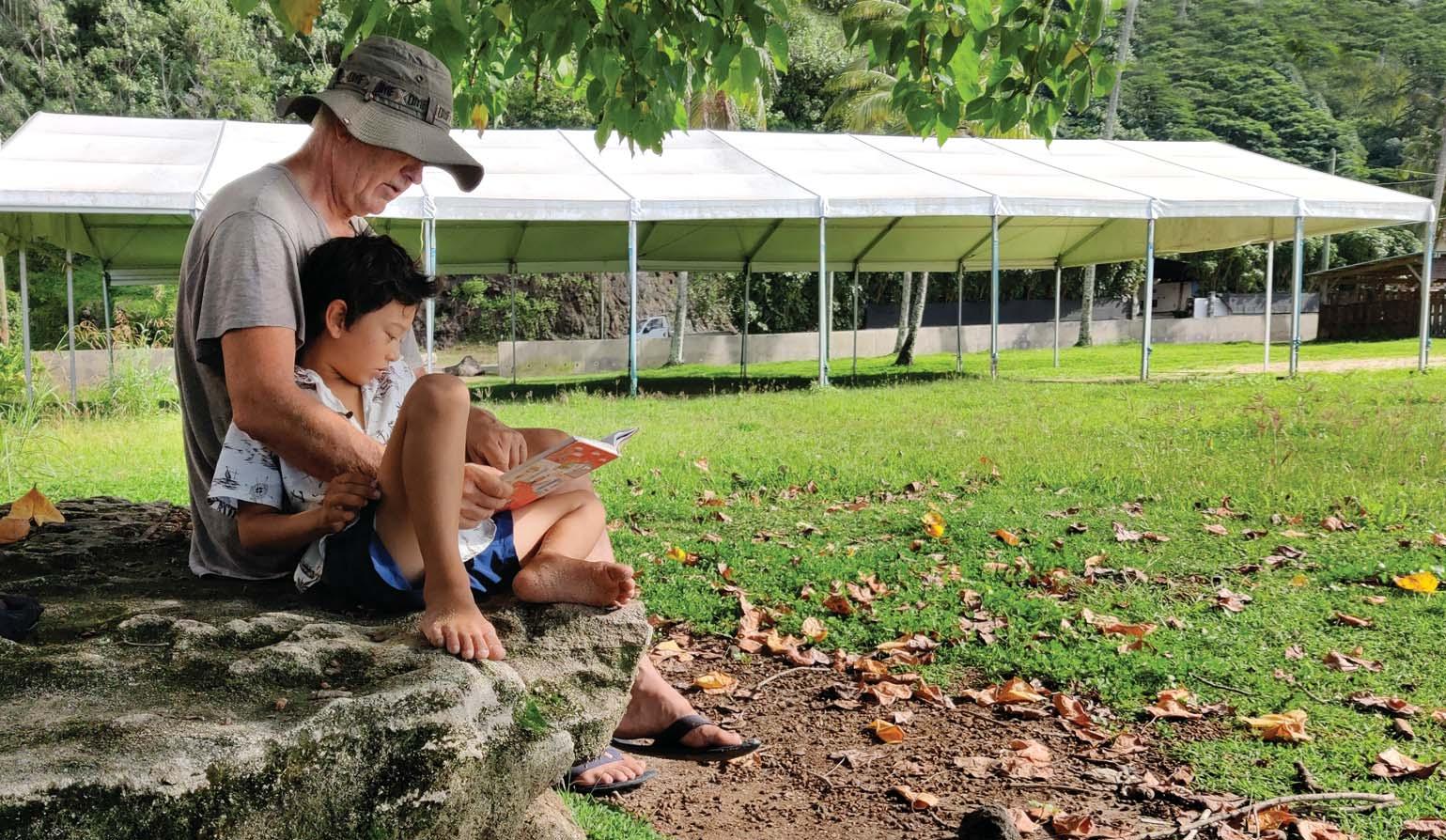

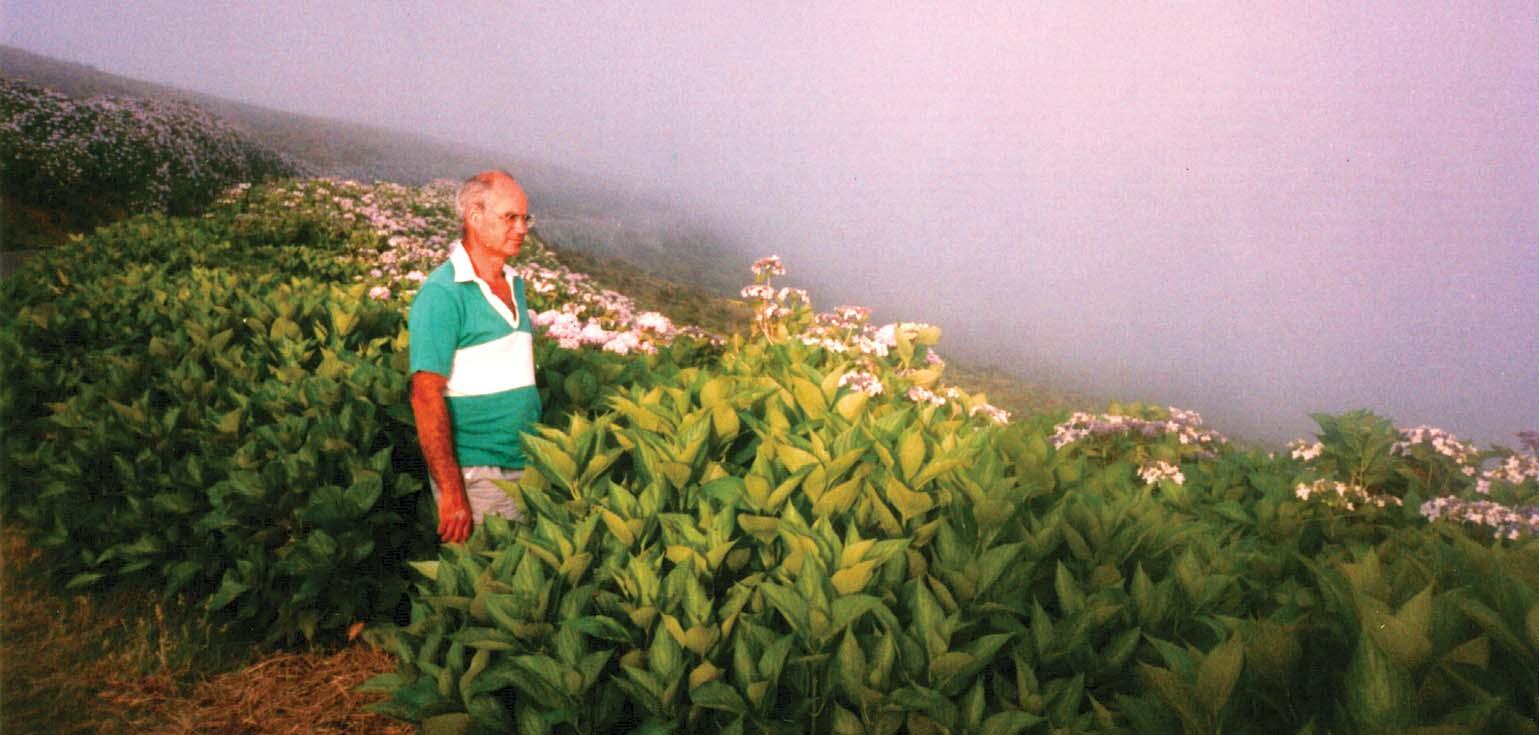

After ten months of boat failures in Indonesia, my most difficult passage in recent memory and with Rudis on the hard, I just wanted a break. I wanted to spend time with my dad and Jamie. I really wanted to spend some time not working on the boat. The GoFundMe page was an immediate success though, so it was time to start getting Rudis ready for the Indian Ocean. I started researching how to get a new engine and rigging and get them installed in Thailand. Dez at Krabi Boat Lagoon was helping me with this, then told me bluntly, “Even if you put $20,000 into this boat it will still be a $10,000 boat. There’s a boat right next to yours that is in great shape and the owner is keen to sell”.

I had never considered changing boats, but Jamie and I decided to take a look at Tiama, a Bristol 35.5. Though only six inches longer than Rudis she was newer, wider, taller, nicer and even had a door for the heads – I was instantly in love. The only problem was that she was too expensive. Dez said the owner might part with her for $35,000, which was much less than he’d paid for her just a year previously. My GoFundMe was doing well, but not that well. Tiama seemed just out of reach but I decided to contact the owner anyway.

I e-mailed Neil, who owned Tiama, telling him that I loved the boat, sharing a link to my crowdfunding page and offering a down payment/payment plan. He responded quickly that he was not interested in offers significantly below the asking price, but he would be at the marina the following day if I wanted to meet. We ate lunch, talking about the boat and about my goal of being the first double amputee to sail around the world alone. Neil told me he was busy and didn’t

have time to maintain and enjoy a cruising boat. The only way he would consider a low offer would be if there were a fast and simple transfer of ownership.

It took a few days to assess how much I could offer in a short time-frame. My crowdfunding had slowed down and was at about $12,000 dollars, but I found someone who wanted to buy Rudis for $5000 dollars. I wrote to Neil saying that I could come up with $20,000 by the end of the following month. I wrote that I didn’t need a sea trial and knew the boat was worth far more, but that was everything I had. Neil wrote back that I seemed sincere and he thought Tiama would be a good boat for me, but he needed to think about it. After a few really long days he wrote back that if I could come up with the $20,000 the boat was mine. I was ecstatic but stressed since I was still short.

Over the next month crowdfunding money continued to come in, but the person who wanted to buy Rudis kept failing to pay me when he said he would. As my deadline was approaching and I was about $5000 short, I reached out to a few friends for a loan and my friend Greg came through. He told me to write up a contract to pay him back and to make sure it did not affect our friendship. I was just able to keep my side of the deal and Neil kept his. While all this was happening Jamie caught dengue fever and had a rough recovery. By the time she got better, and after another trip to the hospital, we were both low on money. We were not ready to say goodbye, but she had to get back to work and I had a new boat that I needed to get ready to cruise, so we said our goodbyes and Jamie flew back to Hawaii.

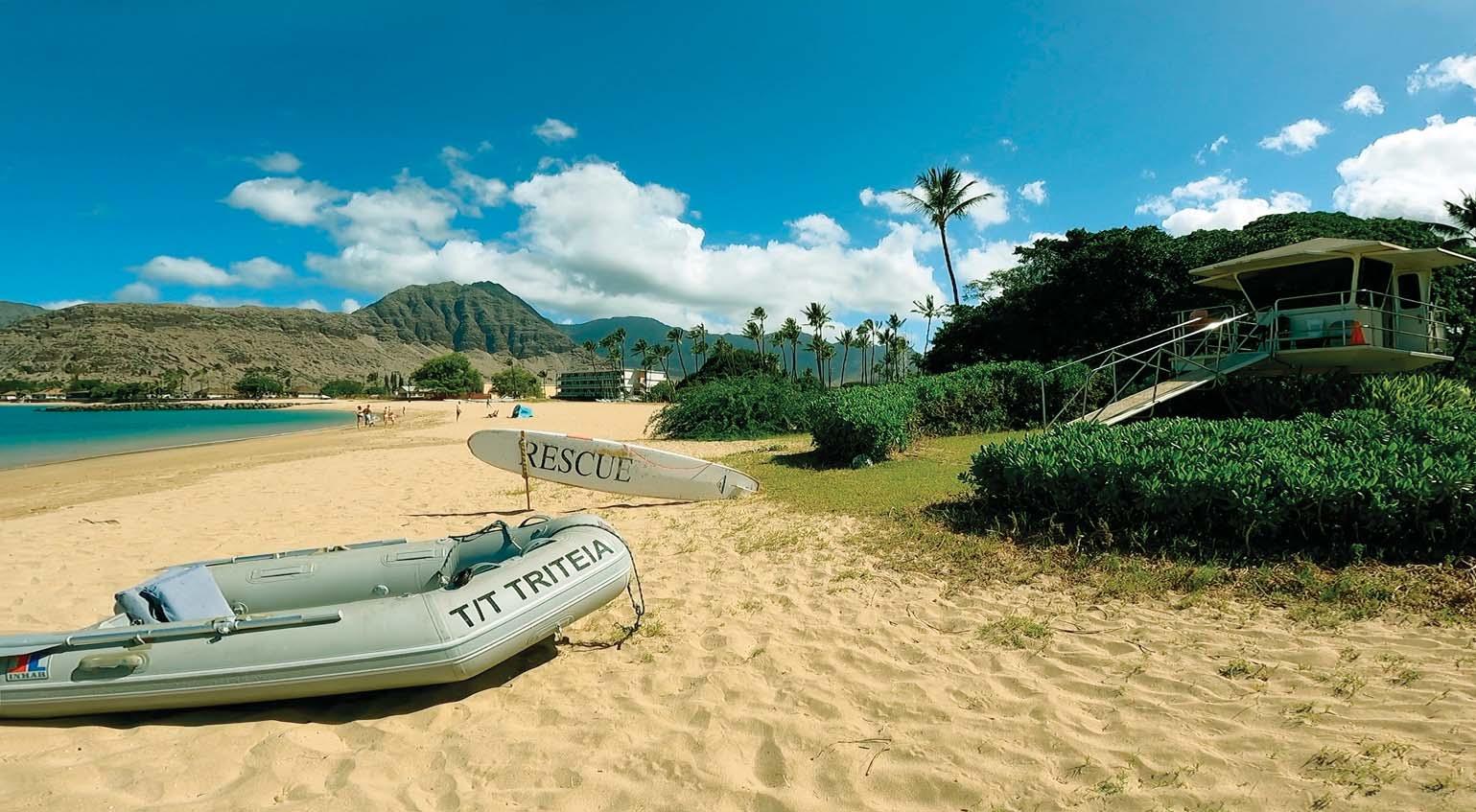

I took the windlass and watermaker off Rudis and installed them on Tiama. I also wanted to add solar panels, dinghy davits and new batteries. I decided to go back to Hawaii, take a short-term job and do a yacht delivery from Hawaii to California. It was my first time back home in almost three years and nice catching up with friends and family, but strangely I felt a little out of place. I had set off to sail around the world and only made it about one-third of the way. I was homesick before going back to Hawaii, but within two months I’d saved enough money to do all the work I’d planned on doing and was ready to get back to the boat. Just before I flew to O‘ahu for my yacht delivery I got a phone call from the coast guard telling me that the EPIRB on Rudis had been triggered. I called the new owner and asked if everything was okay and he informed me that he

Jamie, Rudis and mehad sunk the boat in shallow water near the Koh Jum fishing village. I was angry and sad he had sunk her – she had been my partner for 2½ years and one-third of my trip around the world. She deserved better.

A few days later the guys doing the salvage job called me and said they didn’t know what to do. “Dustin, there are pornographic magazines washing up on all the beaches! The Muslims on the island are really pissed! How many are there?” I told him there were about a thousand – “Sorry, they’re going to be floating up for a long time!”. When I’d bought Rudis I’d asked the previous owner what the best things to trade were. He’d responded quickly with ‘alcohol, cigarettes and porn mags’. I mentioned this to my roommate, so for Christmas that year I received an eBay lot of 1000 porn magazines. The problem was that I wasn’t confident enough to ask people if they wanted to trade for porn and only once I was asked, so by the time I got to Thailand and was moving my personal items from Rudis to Tiama I still had about 995 on board. I asked the new owner if he wanted them and he said ‘sure’, which ultimately led to their fate on the beaches of Koh Jum.

By the time I returned to Tiama the Thai monsoon season was in full effect. It was hot, humid and impossible to weld dinghy davits in the rain. My planned one-week haul-out turned into two really uncomfortable months, though I was able to use the time to go through the boat and learn about everything on board. Eventually the davits were finished and I was able to launch my new boat and start sailing around. Tiama was nice, fast and comfortable. Truly a night-and-day difference from Rudis.

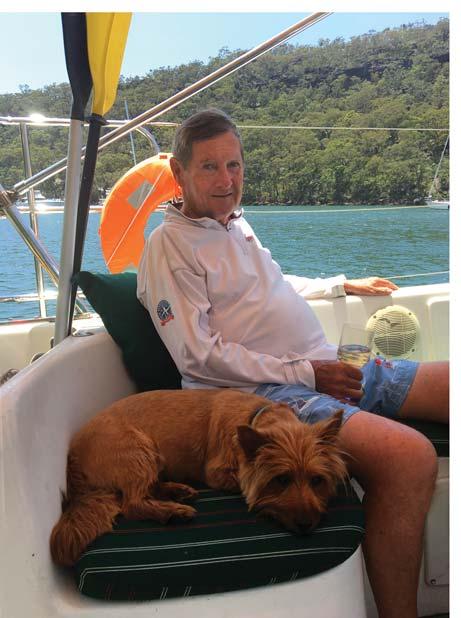

I had one more holiday season in Thailand to spend with my dad before starting my Indian Ocean crossing. We did a roundtrip to Langkawi, Malaysia then sailed back to Krabi for Christmas with his wife and friends. Then I went up to Patong for New Year. New Year in Patong is a special thing – every beach hotel has its own fireworks display and what seems like millions of lanterns lift off the beach. I spent the New Year with my good friend Harry and we started to plan to buddy-boat across the Indian Ocean.

Our first stop was at the Andaman Islands. The Andamans have a very strict and expensive check-in procedure – they’re only about 450 miles from Phuket but are clearly a different country and culture. Seven officials came on board and required a total of 72 pages of paperwork. Despite the expense and time-consuming check-in the Andamans are well worth the 30-day maximum visit. Harry and his crew on Moyo buddy-boated with me, and my friend Fran also came to visit. We spent most of the 30 days on uninhabited islands, spearfishing by day and playing games and drinking at night. It was amazing, but the 30 days passed quickly and soon it was time to go to Sri Lanka.

The passage to Sri Lanka was the first time Tiama and I got into a bit of rough water. It was a mostly easy passage until the wind picked up to 30 knots on the nose. Harry arrived in Galle just before the wind turned, but I spent two days tacking upwind which Tiama did pretty well. Sri Lanka was one of my favourite countries to visit but my least favourite place for having a boat. The check-in process was expensive, the harbour was rough and dirty and corrupt military officials would shake me down for ‘duty’ (bribes) on anything I bought. On the positive side, the wildlife and country were amazing. I rented a scooter for three months and just explored.

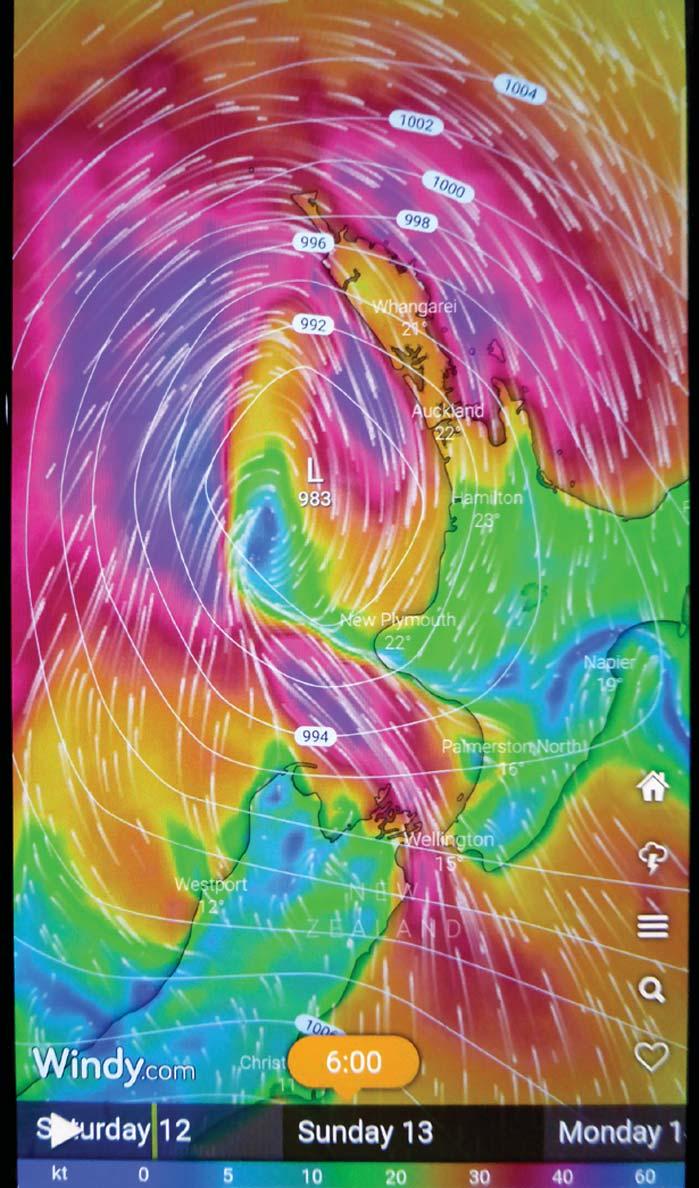

An elephant crosses the path in Sri LankaThe most difficult thing about visiting countries with limited time to stay is picking a weather window to leave. Just as the Moyo crew and I were running out of time on our permits, a hurricane was forming off India – it was far north of us but the normally northeast winds turned southwest. It looked as though we would bash for about five days, cross the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), then get a downwind run in the southeast trades the rest of the way to the Chagos Islands. Sadly the storm pushed the ITCZ too far south and we had 1000 miles of beating into 15–40 knot winds. I just took whichever tack gave me the best VMG and bashed into the southwest winds. It took me 12 days in Tiama and Harry 14 in Moyo, a catamaran.

Chagos is another special place for cruisers. You can only get a permit for 28 days but there are few places with such a minimal touch from humans. Boobies escort you into the anchorage, where you drop your hook into the crystal-clear lagoon. There were 22 boats there when I arrived and Alan from Kiwi Dream swung by in his dinghy with cold beers. The last time I’d seen Alan had been six months previously in Thailand and I knew the people on 20 of the 22 boats there. A few I’d not seen since the Pacific, two years earlier. It was an amazing reunion of world cruisers. During the 30 days I spent there we had evening sundowners, pot lucks and adventures in large and small groups. With the exception of a few boats we all sailed to Madagascar next and continued the trans-Indian Ocean flotilla.

The passage to Madagascar was a rough and fast broad reach. Tiama and I covered the 1650 miles in ten days, by far my fastest passage to date. There are two ways to round Cap d’Ambre at Madagascar’s northern tip, the trickiest bit of water I have ever had to contend with. You either pass close enough to stay inside the breaking waves formed by the opposing current or go a hundred miles to the north. I chose the one-foot-onshore, one-foot-on-the-boat route. The waves off the cape commonly reach over 15m and I had 35 knot winds and 16m waves forecast on my weather report. I tried to slow Tiama down so we would round it in daylight but the wind and current wouldn’t let me. There was no moon, but Mars and Venus lit the way. Rounding the cape I could hear the waves breaking to starboard and smell smoke from the nearby villages to

With a black lemur and giant tortoise in Madagascar

port. The waves continued to get louder until suddenly it was flat calm.

I motored for about an hour until the breeze picked up and then sailed to the nearest nicelooking anchorage. I quickly launched the dinghy and went for a walk ashore hoping to get some fresh food. It had been over two months since my last grocery store in Sri Lanka and I had eaten pasta and red sauce for the previous three days. The villagers were less than welcoming, which was the first and only time this happened in my entire circumnavigation. Usually people were quite curious and excited to meet the solo sailor who was missing an arm and leg, but here all I got were anxious looks. It took a while to find anyone who spoke English, but when I did he told me there was a horrible human trafficking problem in Madagascar. He said that men used to come promising money and education for female children, but once the villagers got wise to that and realised they never came back, they would just take them in the night. So to the locals a white person on a boat is a possible slaver ... in 2018, a white person on a boat off Africa is a possible slaver!!! He told me not to take photos but to simply introduce myself and, surprisingly, the locals warmed to me. I’ll never forget that these people not only didn’t show me anger based on very understandable prejudice but that they were willing to share their fresh food with me. If only we could all be so graceful in the face of extreme oppression.

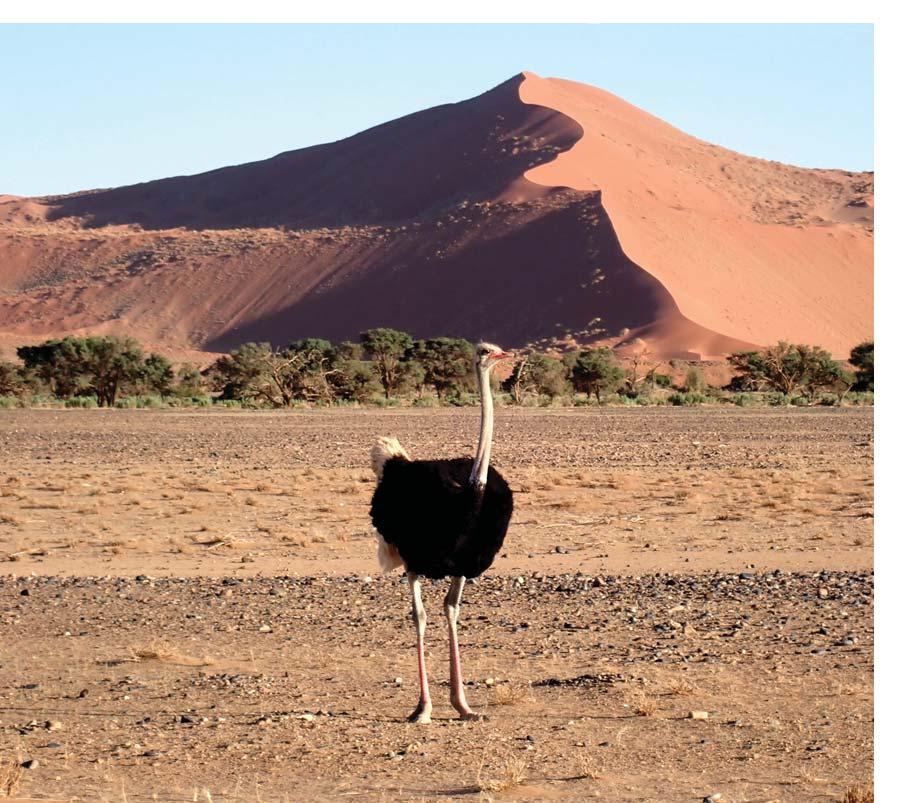

Madagascar, Mozambique and South Africa were amazing, terrifying, loving, violent, beautiful, peaceful and my home for a year. I’ve always

On the 10th anniversary of my motorcycle crash we held a party on Bazaruto island off Mozambique

thought books, poems and songs written about Africa must have exaggerated a bit. I was wrong. As a visitor I was grossly uneducated on all the politics, racism and generational strife, so will not weigh in on any of these. What I can say is that every passage was tricky with limited weather windows and horrific consequences if you got it wrong, though weather router Des Cason* makes this all much easier. Despite the tension between the Africans and Afrikaners, both are very welcoming to Englishspeaking visitors. I even gained 10 kilos from African braais (wood or charcoal-fuelled barbecues). This was also the first place people started to recognise me from media bits. Every marina in Africa sponsored my stay, including two months at the Zululand Yacht Club in Richards Bay while I joined a friend’s boat and sailed to Antarctica.

When I returned from Antarctica I was informed that I would be the recipient of the OCC’s Seamanship Award for 2018. I was still not a big part of the yachting community at this time and was surprised by the news. Having started my circumnavigation in the Pacific I always seemed to be the least experienced sailor in the anchorage and was surprised to receive an award from a club that only accepts sailors who have done an ocean passage. The OCC put together a presentation ceremony at Cape Town’s Royal Cape Yacht Club –I just needed to sail about 1000 miles around the Cape of Good Hope to make it to my party. With Des’s weather routing help I made it with a few days to spare. As someone

* See Flying Fish 2019/1, page 15.

A mahi mahi I caught off South Africa

Leaving Mozambique

Leaving Mozambique

Receiving the 2018 Seamanship Award at the Royal Cape Yacht Club

who is uncomfortable with compliments and scared of public speaking, an award ceremony in my honour where I was expected to give a speech was far more intimidating than any ocean passage. It was my first time as the centre of attention in a room full of sailors, something which still intimidates me. The evening went off without a hitch, though, and I made friends I still talk to today.

There were two remote places left in my path home – St Helena and Ascension Island – both of which I was looking forward to, though I was sad to leave South Africa. Just before leaving I read about an indigenous beetle only found in St Helena, but there is a different excitement level about beetles than there is about lemurs, rhinos, elephants, lions, hippos and African braais.

I did the 1700 mile passage to St Helena with full sails wing-and-wing, without reefing once in 11 days. This was the first passage I’d completed without reefing or closing my hatches! For the second time, Alan on Kiwi Dream met me with cold beers as I sailed into the anchorage. I hadn’t seen him since Madagascar, and we shared stories about

Ascension Island

Ascension Island

our travels since we’d last shared an anchorage seven months earlier. There were eight yachts in the anchorage and I recognised all of them. The check-in process was quick and easy and afterwards I swung by the nearest bar to meet the locals. St Helena and Ascension are the only places I’ve ever visited where I could buy a drink in a bar for a single coin – it was a coin worth GB £2 / US $3, but it felt like the wild west.

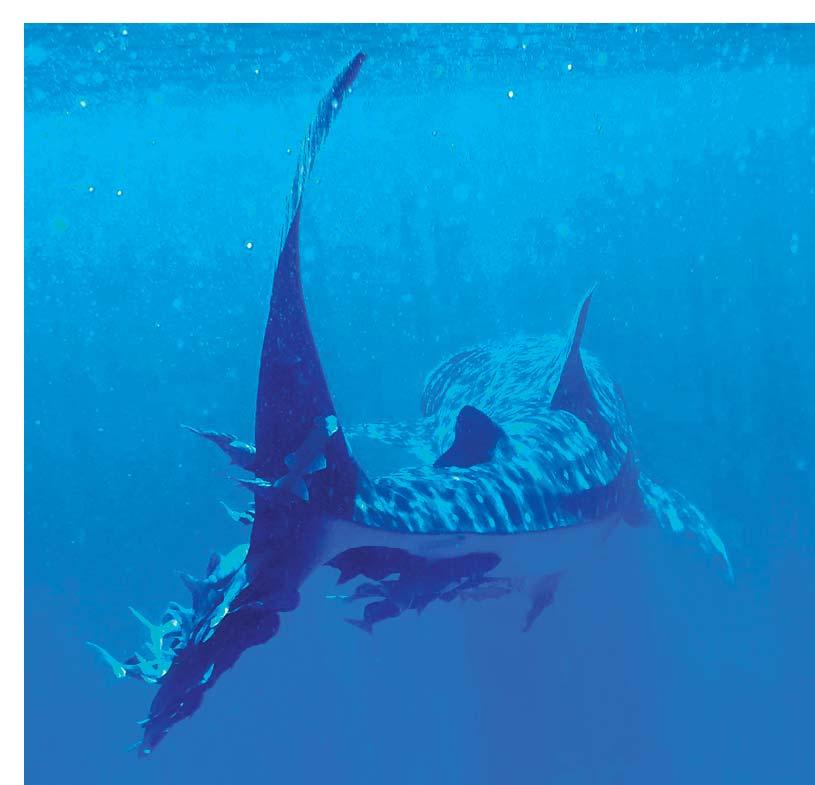

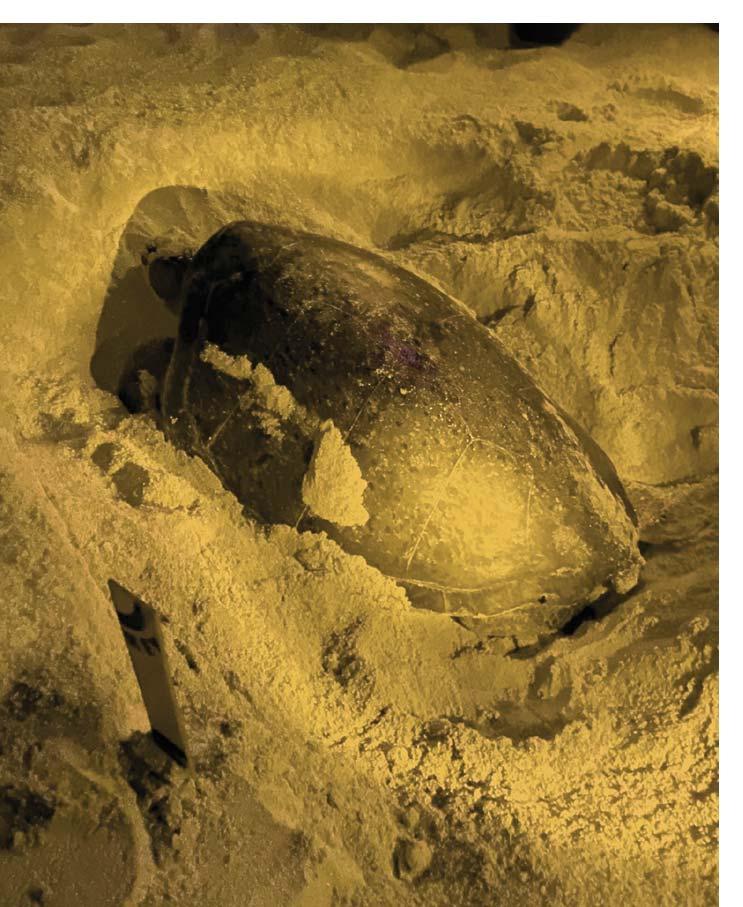

The diving in St Helena and Ascension was amazing and the few cruisers there were all up for daily adventures. There were whale sharks and devil rays to swim with and tons of fish and lobsters for dinner. On Ascension there was even a nightly show at sunset when the baby turtles would leave their nests and head for the ocean. It was May 2019 and I’d planned to avoid the majority of the Caribbean hurricane season by staying a few months each in St Helena and Ascension, but ended up staying just a few weeks as my batteries were going bad and the dinghy davits needed repair if they were going to stay on the boat.

Max and Tanya in Alalilia left Ascension for Brazil at the same time as I left for Grenada. Four days into the passage they messaged me on my Garmin inReach from their satellite phone – they had hit a whale and lost their rudder. They were about 150 miles upwind of me, so I altered course to intercept. I asked them to send a position report with each message so I could judge their drift. It took about 36 hours to reach them and of course it was near midnight by the time I saw their masthead light swaying in the Atlantic swell. We had formulated a plan for me to give them my series drogue so they could steer their boat by drag. The tricky part was passing the drogue to a swaying boat without steering at night. The drogue was stored in a dry bag, to which I tied a line to throw to Max. I figured that as soon as I saw that he’d grabbed the line I could toss the bag into the water and he could haul it in. It went off without a hitch on the second attempt. Max and Tanya got it to work and continued to Brazil while I changed course back to Grenada.

Most of the world cruisers with whom I’d shared the Indian Ocean made short stops in the Caribbean before continuing to the Pacific or across to the Mediterranean. However, Fabio and Lisa on Amandala were still around to celebrate my arrival to Grenada and Fabio made a lasagne. It just happened to be 16th June, five years to the day since I’d sailed away from Hawaii. I made a few new friends in the Caribbean but it was a bit different. I was fatigued from five years of sailing alone and constantly meeting new people. Most of the Caribbean boats had come down from Florida or possibly across from the Mediterranean and suddenly I was usually the most experienced cruiser at the yacht clubs instead of the beginner who taught himself to sail from YouTube.

Thankfully I met Thom Darcy on Fathom, another solo sailor who had just completed his circumnavigation. I had heard of him from mutual friends but had never shared an anchorage with him. It was fun swapping world travel stories and hearing from him how it felt to complete a solo circumnavigation. One night, after a few of Thom’s Ti punches (rum, sugar and fresh lime) I lost my prosthetic leg overboard while putting my dinghy on the davits. I grabbed a light and my swim leg to have a look but couldn’t find it, so figured it had sunk and I could just dive for it in the morning. But after an extensive search the next day it was nowhere to be found – it must have floated away. After a few Instagram and online lost-and-found posts it was clear it was gone for good. Thankfully several companies offered to sponsor a new prosthetic – I just needed to fly to San Francisco. I said goodbye to Thom in Antigua. He was leaving for the Azores and I was off to the USVI to catch a flight to San Francisco. It was February 2020 and I was hoping for a two-week trip to get my leg fitted before heading to Panama in May to cross into the Pacific. Covid had other plans.

By the time I got back to Tiama in March the world was shutting down. Andy Tyska from Bristol Marine had contacted me a few months earlier and offered to sponsor a haul-out if I brought Tiama up to Rhode Island – Tiama had been built and launched in Bristol in 1983. I had declined his generous offer since it was a bit out of the way and I was almost home, but in May 2020 Panama was closed along with pretty much everywhere else in the Caribbean and the hurricane season was coming fast. I reached out to Andy and asked if his offer was still good and he said yes. The 1500 mile passage to Rhode Island took me two weeks, mostly because I had to avoid tropical storm Arthur which hit Bermuda. I took a big detour west of the island to avoid the storm and got 40 knots of wind and some rough seas.

Even after two weeks at sea it was not clear if I was supposed to quarantine on arrival in Rhode Island. I dinghied ashore in Newport, and though the streets were almost empty it looked like an Irish bar was open. It turned out that the bar itself was closed but I could sit at a table with plexiglass dividers around it. It was the loneliest I ever felt in my entire trip – after two weeks alone at sea I was finally around people again but in my own little fishbowl. I ate my dinner and went back aboard to have my celebratory Scotch after an ocean passage.

The sail to Bristol next day was pretty cool. It was fun bringing Tiama back to where she had been built after her lap around the world. The Bristol crew were amazing and eager to help. I left to do two yacht deliveries to pay for parts, and by the time I got back Tiama was hauled out with fresh paint on the bottom. In the two months she was there she got her cabin sole refinished, new rigging, new electronics including radar and AIS, bottom paint, brightwork on deck and engine service. She was ready for another lap.

I cruised New England for a while, stopping in Provincetown, Martha’s Vineyard and Long Island before continuing into New York City. It was amazing sailing to all these places I’d only seen on TV and I spent my first night in New York anchored right next to Lady Liberty with a bottle of champagne. It was October 2020 and the city was starting to open up, and I met some friends who were happy to show me around. It

New York City

Leaving

New York City

Leaving

was nice seeing New York without tourists and to walk into all the famous museums without queuing. My six week stay was sponsored by One°15 Brooklyn Marina – I would never have been able to afford it otherwise. But November and the cold weather came fast and it was time to head south.

The weather windows south were short, rough and cold. I stopped briefly in North Carolina en route to the Bahamas to wait out a cold front and for good weather for my arrival, only to discover that the entrances through the reefs in the Abacos look a lot trickier than they are. Inside the reef was my first time sailing in 2m of water on purpose, which took some getting used to. When I dropped anchor off Manjack Cay on Great Abaco, Tim on Tardis dinghied over and gave me two fresh lobsters. We became instant friends and spent every day spearfishing and every night feasting. It is amazing to me that an inhabited area so close to Florida has so much sea life. There was clearer water and more lobsters and sharks in the Bahamas than anywhere else I’d seen.

The Covid restrictions in Cuba and Haiti were really strict so I just sailed by en route to San Andrés and Panama – a huge bummer as I’ve always dreamed of going to Cuba. Bocas del Toro in Panama was my first stop since Newport where there were a lot of cruising boats. Most had been there through the worst parts of the lockdown and had stories to tell. Cruising around Bocas was beautiful with tons of jungle wildlife. It really has

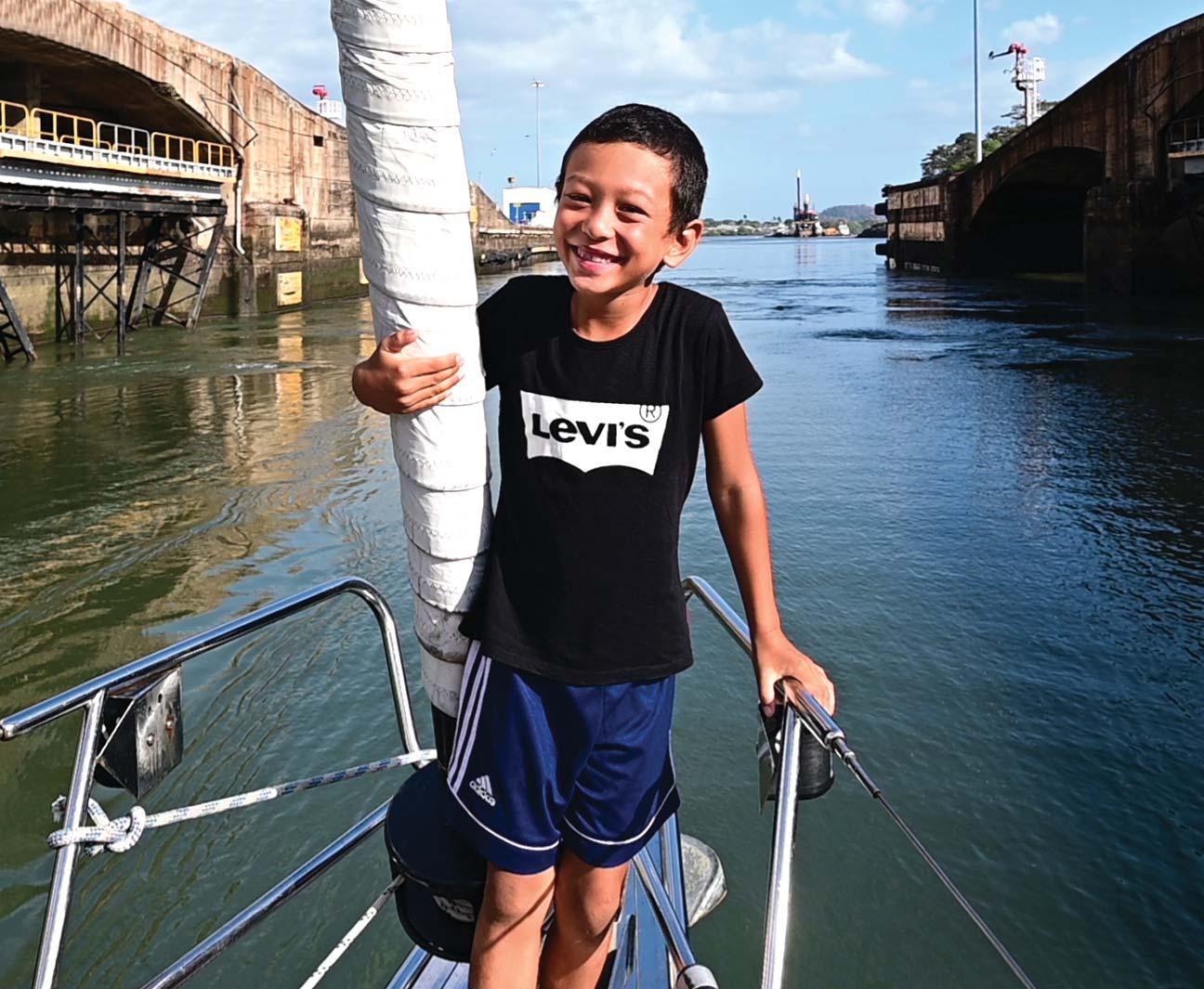

My Panama Canal crew

everything for cruisers, including great restaurants and bars, fresh produce delivered right to the boat and secluded anchorages just a short sail away. I could have stayed longer but the canal and the Pacific were so close.

I booked my canal transit for just after my birthday in May and four friends from Hawaii flew out to be my line handlers. It is the only part of my circumnavigation where I needed crew and it was special to spend it with friends. They were all extremely capable boat people and fun to have on board, despite the cramped conditions with five people on a 35ft boat. We laughed, drank, danced and planned my arrival home. As the locks opened and we entered the Pacific Ocean it felt as if I was already there. The idea that I could raise anchor at anytime and sail home was crazy after seven years away. There were just the Galapagos, the Marquesas and 5000 miles of Pacific Ocean to go.

The Galapagos and Marquesas were amazing and reminded me why I wanted to do this in the first place. The wildlife, island communities, salty world cruisers and Pacific Ocean were a breath of fresh air after two years in the Atlantic. I made new friends, enjoyed local food and customs, fished and dived as I waited for the Northern Pacific hurricanes to pass by. Then there was a total lunar eclipse on the night I left the Marquesas for my 1950 mile passage home. I daydreamed of rounding the rough seas of Hawaii’s South Point and sailing home up the calm leeward waters. It was whale season and I imagined being escorted in by breaching humpbacks and spinner dolphins. I was excited I’d soon see all my friends that I hadn’t seen in years.

As I approached the big island I could smell the dirt and plants before I could see it. I could feel the waves bouncing back off the island. I could almost taste the champagne ... and then a low pressure system hit and delivered the worst Leaving

weather I’ve ever seen around Hawaii. The last 61 miles took 24 hours of bashing into 30 knot winds through dense fog. There could have been whales around, but I wouldn’t have seen one unless it had landed on deck. I’d been told this was coming and had considered diverting to Hilo on the northeast coast, but a bunch of friends had flown out to see me finish my trip so I figured I could deal with one day of bad weather.

... as well as a traditional lei

As I approached Kona the fog started to lift and I caught my first glimpse of home. I’d been no more than 10 miles offshore for the previous 22 hours but hadn’t been able to see the island through the fog. I saw friends on a local sailboat taking pictures and drones flying overhead as I entered the marina I had left 7½ years before. Most of my friends that had been on the dock when I left were there when I arrived, but this time I was showered with champagne and covered in leis. I’d hoped I would have something profound to say after my long journey, but all I could think of in my state of exhaustion was, “That was easy!”.

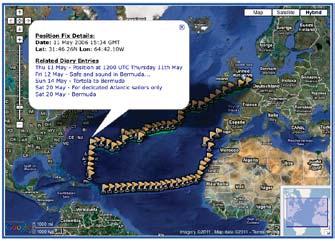

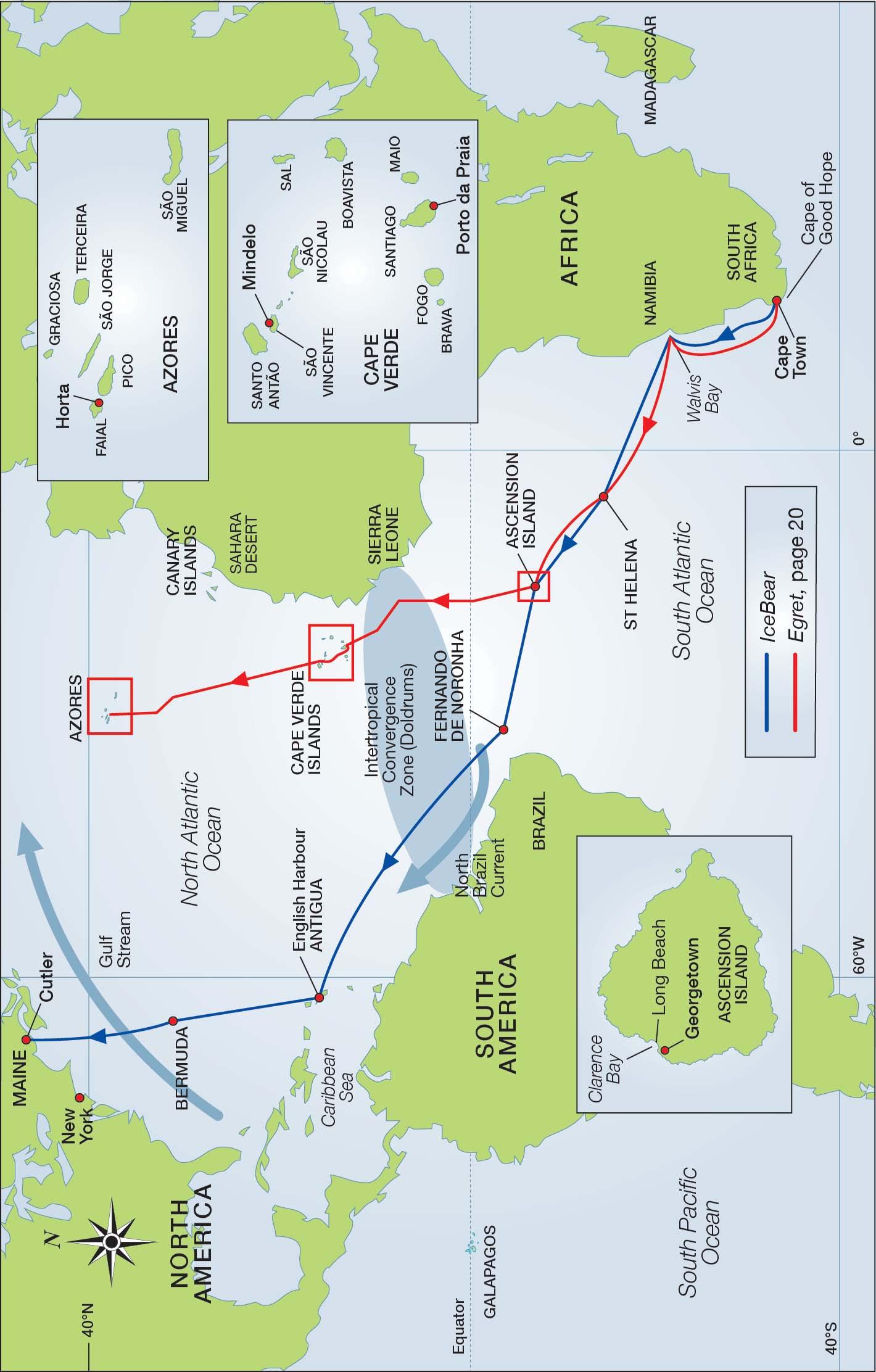

(Egret is a Sweden Yachts 390 which Patrick and Amanda have owned since 2007. Between 2011 and 2015 they circumnavigated via the Panama Canal and the Cape of Good Hope, completing the last 1650 miles of their outward Atlantic crossing steering by drogue after the loss of their rudder (see A Directional Challenge, Flying Fish 2012/2).

Over the past few years they have cruised the Biscay coast, the Irish Sea, the west coast of Scotland and onwards to Norway. Egret was laid up ashore on the east coast of Sweden in the autumn of 2020 where, due to Sweden’s strict Covid rules concerning travel from non-EU countries, she remained until the summer of 2022 when Patrick and Amanda were finally able to bring her home.

Much of the passage below can be followed on the chartlet on page 106.)

Looking towards Long Beach from where Egret was anchored in Clarence Bay, Amanda and I watched the ocean swell steepening before turning into combers which tumbled onto the yellow sand with a burst of spray. We were about 500m off and could feel a disconcerting amount of surge as the waves came past, but any further out would have been too deep to anchor. At dusk we could just make out, through the binoculars, some adult green turtles hauling themselves up the beach to lay eggs and, if we shone a torch on the water after dark, then as likely as not a baby turtle would paddle towards us, setting out on its hazardous journey to Brazil.

We’d been at Ascension Island about

five days, but the heavy northerly swell was making landing by dinghy at Georgetown’s small quay somewhat precarious, not to say wet! We’d managed to see the sights around the town, do our essential maintenance work and provisioning, and book a car for later in the week to explore the hinterland, but the forecast was for the swell to worsen and, after a horrible night with down-drafts throwing the boat first one way then the other, snatching the anchor chain violently, we decided we should move on immediately.

It was late April 2015 and we were aiming to reach England by the end of the summer, the culmination of a four-year circumnavigation. From Cape Town, our plan had always been simply to head for the Azores – if this had been good enough for the Hiscocks aboard Wanderer III in 1955 and Wanderer IV in 1975, it would do for us! We were a bit surprised to learn that hardly any other boats were going our way. Most were heading for the Caribbean, but we felt that a second visit might be something of an anti-climax after all we’d seen on the other side of the world, and we’d still have a west-to-east crossing of the North Atlantic to tackle, seldom a straightforward passage. We had enjoyed stop-overs in Namibia and St Helena, but were ruling out Brazil due to a recent spate of nasty attacks on yachts. Our final call on this leg would be the Cape Verde islands, which would put us in a good position to tackle the northeast trades thereafter.

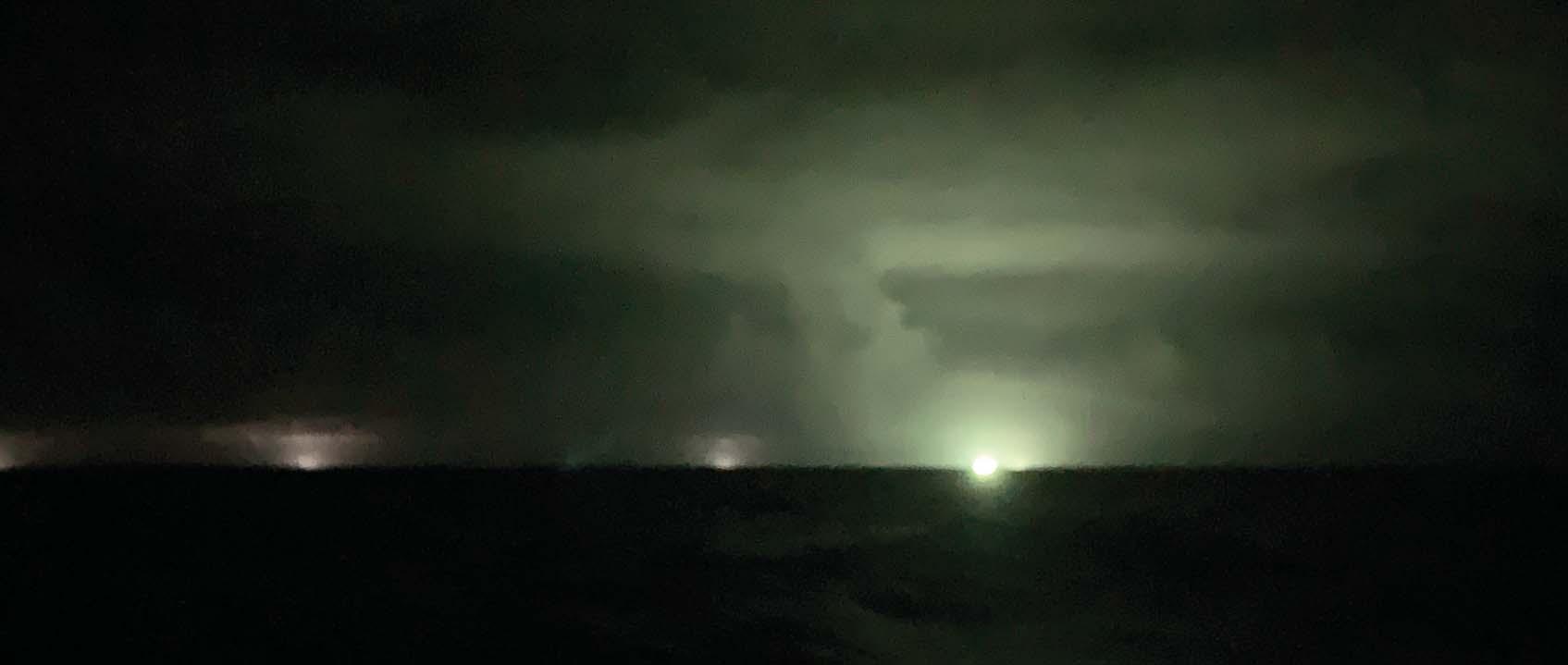

The first few days were pleasant enough with winds of between 10 and 20 knots on the quarter, allowing us to fly the cruising chute at times. Then on day five we noticed a tall column of cumulus cloud developing to the east, followed by a separate band of dark cloud. We put three reefs in the mainsail and furled the genoa just in time before

a squall engulfed us, though the gusts only reached 27 knots and were fairly short-lived, and we were back under full sail within three hours. Showers passed over regularly from early the following morning and the wind gradually backed to the northeast, easing to around 6 knots. We spent much of the day dodging the severest rain clouds, with reasonable success. We were now well and truly within the doldrums.

We crossed the Equator just before sunset, taking us into the northern hemisphere for the first time in nearly two years. We shared a celebratory tot of rum-and-lime and a slice of cake with King Neptune. Pilot books advise where to cross, depending on the time of year, so as to minimise the width of calms in the Intertropical Convergence Zone. With our usual scepticism we compromised, weighing up this advice against the latest weather information and the effect the offset would have on distance to sail. We initially aimed to cross at 22°W, revising it in the light of later forecasts to 20°W.

In the doldrums close to the Equator, hoping to dodge squalls

In the doldrums close to the Equator, hoping to dodge squalls

A few days later we entered an area of cross-currents in excess of 2 knots combined with popply seas. We were passing over a seamount with a summit 2400m below us, rising from 4500m, which I hadn’t expected to have such influence at sea level. The weather over the next three days was a bit of a mixture – at times we enjoyed pleasant sailing in 8 to 12 knots of wind, mainly from the easterly sector, but we also endured long periods motoring across a gently undulating sea with hardly a breath. There were spells of steady rain and we had to remain diligent in case of squalls, but only three had much strength in them, with gusts of up to 30 knots. From time to time at night we saw flashes of lightning in the far distance, but thankfully none came close.

We passed through rafts of curly, yellow-brown sargassum seaweed which caught on the rudder, the blade of the Aries self-steering gear and our fishing line. When the boat started to slow, we cleared the weed by putting the engine into astern for a couple of minutes. We began seeing Portuguese men o’ war wafting past, capsizing in our wake to expose their venomous tentacles. The doldrums proved to be about 400 miles wide and took around four days to cross, half of that under engine.

The new trade winds arrived on day ten, but instead of northeasterlies we had to contend with northerlies. At first the sailing conditions were lovely – in fact it was a pleasant change to be sailing to windward in a gentle breeze after all that time rolling downwind. Over the next week, however, we had stronger spells when we set the staysail instead of the genoa, as well as several periods with scarcely any wind at all. It was getting hazier and, from about 9°N, red Saharan dust was showing up on light coloured surfaces such as the sprayhood. It was also getting chillier, needing a sweater on deck at night and a sheet to sleep under.

We saw more and more ships, including three big French fishing vessels which kept reappearing over the course of three days. We called one up on the VHF when it set off our AIS alarm – the captain laughed, and assured us there would be no collision. They don’t realise how intimidating their ships look from the deck of a small yacht. Another ship reported that some equipment had collapsed, leaving floating debris –great, that’s all we needed! We certainly didn’t want a repeat of the damaging collision that had removed our rudder during our outward voyage from Cape Verde to St Lucia four years earlier.

We are used to hearing chatter on VHF Channel 16, usually fisherman having no respect for the rules. For two nights running I heard a series of rather sinister, one-sided conversations. A man was giving instructions in heavily accented English for some indecipherable operation, and at one point I heard what sounded like pistol shots, shouting and a scream! Perhaps it was just my tired yet vivid imagination playing tricks, or else a radio play intruding onto the airwaves. We were 400 miles off the coast of Sierra Leone, which one would expect to be safe from piracy, but I turned off the transponder function of our AIS set just in case.

We had originally intended going directly to Mindelo, but were running low on diesel so decided to call first at Porto da Praia on Santiago, 150 miles closer. On the morning of the seventeenth day we had our first sighting of land at only eight miles away. The breeze initially faded but, seeing wind on the water ahead, we hurriedly pulled in three reefs before hitting the acceleration zone of high winds blowing off the hills. After a short encounter with strong gusts and choppy seas we gained the shelter of the harbour at midday, and anchored under the ramparts of the picturesque old city. We had logged 1620 miles.

Hardly had we got the anchor down when a boat appeared from the docks on the east side of the bay and came alongside. George told us that he ‘looked after’ all the cruisers who visited Praia and would give us a lift ashore, where the immigration officer was supposedly waiting for us. Always a bit wary of pushy boat boys, we told him that we weren’t quite ready and would come ashore in our own dinghy. Friends had advised anchoring in the northwest corner of the bay, beaching our dinghy between two old concrete jetties, where fishing boats were hauled out for

The waterfront at Praia, Santiago. We landed our dinghy between the two piers to visit the maritime police in their blue building amongst the trees

repair. As we approached two lads ran down, waded out and cheerfully pulled our dinghy above the tideline almost before we could get out. They looked surprised and happy with the few escudos we gave them in return. They indicated that they would look after our boat and pointed out the office of the maritime police on the other side of the fence.

The officer cleared our yacht into the country with the minimum of questions and paperwork, pleased that we were revisiting after seeing the Cape Verdean stamps already in our passports. He advised us that it might be unsafe to walk to the immigration office in the port so we should take a taxi. George was looking out for us, though a bit put out that we had landed our dinghy away from his patch, but he earned himself a tip by leading us to the immigration office and afterwards hailing another taxi to take us into the town.

The walled city of Praia, the capital of Cape Verde, is located dramatically on high ground above cliffs at the head of the bay. Factories nestle in the valleys on either side and concrete tenement blocks, painted in white, blues and yellows, rise in tiers one behind the other on the hillsides. The seaward edge of the city is dominated by an old fort which, by the rousing call of a bugle at regular times each day, we presumed to be still in use. The attractive 18th and 19th century buildings were mostly in good order and even the bland modern façades were painted either in cheerful colours or with artistic murals. The guide book had been rather off-putting, so we reckoned there must have been big improvements in recent years. There was an air of prosperity, the busy streets were noticeably clean and litter free and the inhabitants well dressed. We felt welcome in the centre and perfectly safe walking between it and the boatyard.*

The harbour was calm in the prevailing northeasterly wind and one would expect the breakwater to provide good protection except from the southern quadrant. A few other yachts were anchored near the docks, all French and apparently semi-permanent. We took our dinghy there to buy diesel from the service station, where George beckoned

* Sadly Praia has gone downhill since Patrick and Amanda’s visit in 2015. While the city is still safe and well kept, the anchorage can no longer be recommended. In the past three years a number of yachts have been boarded and ransacked at night while their crews slept, culminating in a case when the crew woke up, only to be attacked by the knife-wielding intruders. See page 411 of the current (7th) edition of Atlantic Islands for more details.

us to tie up against a derelict fishing boat and insisted on helping with the cans. He also guided us in buying fruit and vegetables from the street market. To be fair, he did work quite hard and was useful in that he spoke reasonable English.

Sadly we only had time to stay two days before setting off after lunch for Mindelo. Once through the race off the headland we sailed through the night, with the sheets just eased, up the east coast of the island. That morning, punching into steep head seas whilst reflecting on our wonderful cruising adventures, the following lines sprang to mind (with apologies to John Masefield and Cargoes):

Graceful British sailing yacht coming from Ascension, Butting through the Tropics under gloomy grey skies, With a cargo of memories, Souvenirs, friendships, Experience, and learning from the words of the wise.

During the afternoon the wind and waves increased further and it continued blustery and rough into the next night, with seas breaking over the deck. From around dawn, as we fell under the lee of São Vicente, conditions eased rapidly. We first sighted the saw-toothed outline of mountains through the dust-laden atmosphere when 8 miles off, and continued across a flat sea under the high volcanic cliffs, soaking up the morning sun. We headed into the bay of Porto Grande and anchored off Mindelo – quite a moment for us, having just crossed the outward track of our voyage. We celebrated our 3½ year, 34,700 mile circumnavigation with an excellent bottle of South African Villiera Tradition Brut Rosé from Egret’s cellar.

Celebrating our circumnavigation in Mindelo

Mindelo seemed more colourful, less run down and cleaner than we remembered. There were fewer derelict ships, and the remains of one of the last was in the throes of being dismantled by a team of divers. The water was surprisingly clear and from time to time a turtle would pop its head up for a breath of air. The harbour frontage looked particularly attractive, with brightly painted buildings behind the fishing boats pulled up on the beach. It could be that our senses had changed after travelling around the world, but we felt encouraged that this African country seemed to be achieving such improvements to its standard of living.

There were only two other boats at anchor and – out of season in mid May – the marina was less than one tenth full, very different from the final few months of each year when the harbour is usually packed with yachts preparing to cross the Atlantic. The wind howled out of the valleys and got stronger day by day so, fed up with being wrenched about by the gusts, we moved to the marina. We still surged and rolled, but at least it felt safer and we could get ashore and carry out our jobs more easily. The Welsh yacht Sula arrived towards the end of our stay and it was a pleasure to spend a convivial evening with Pippa and Dee, last having met up in Simon’s Town, South Africa.

The marina was largely empty

We were eager to leave for the Azores but the excessive winds, with too much north in them, kept us waiting. Our plan for the 1400 mile upwind leg was to start conservatively with the sails snugged down, accepting that we might be set slightly west of the rhumb line – weather-routing charts showed the trade winds having more east in them at higher latitudes, which would lift our course later on. Eventually we would run into the horse latitudes, where anything might happen but with a good chance of favourable westerly winds.

At last the forecast began to improve. We paid our dues to the maritime police and cleared immigration before the weekend, spent Saturday morning buying fruit, vegetables and beef at the market, delicious bread from the bakery, provisions at the much-improved supermarkets and finally we topped up with diesel. On Sunday we moved back out to the anchorage and prepared for sea.

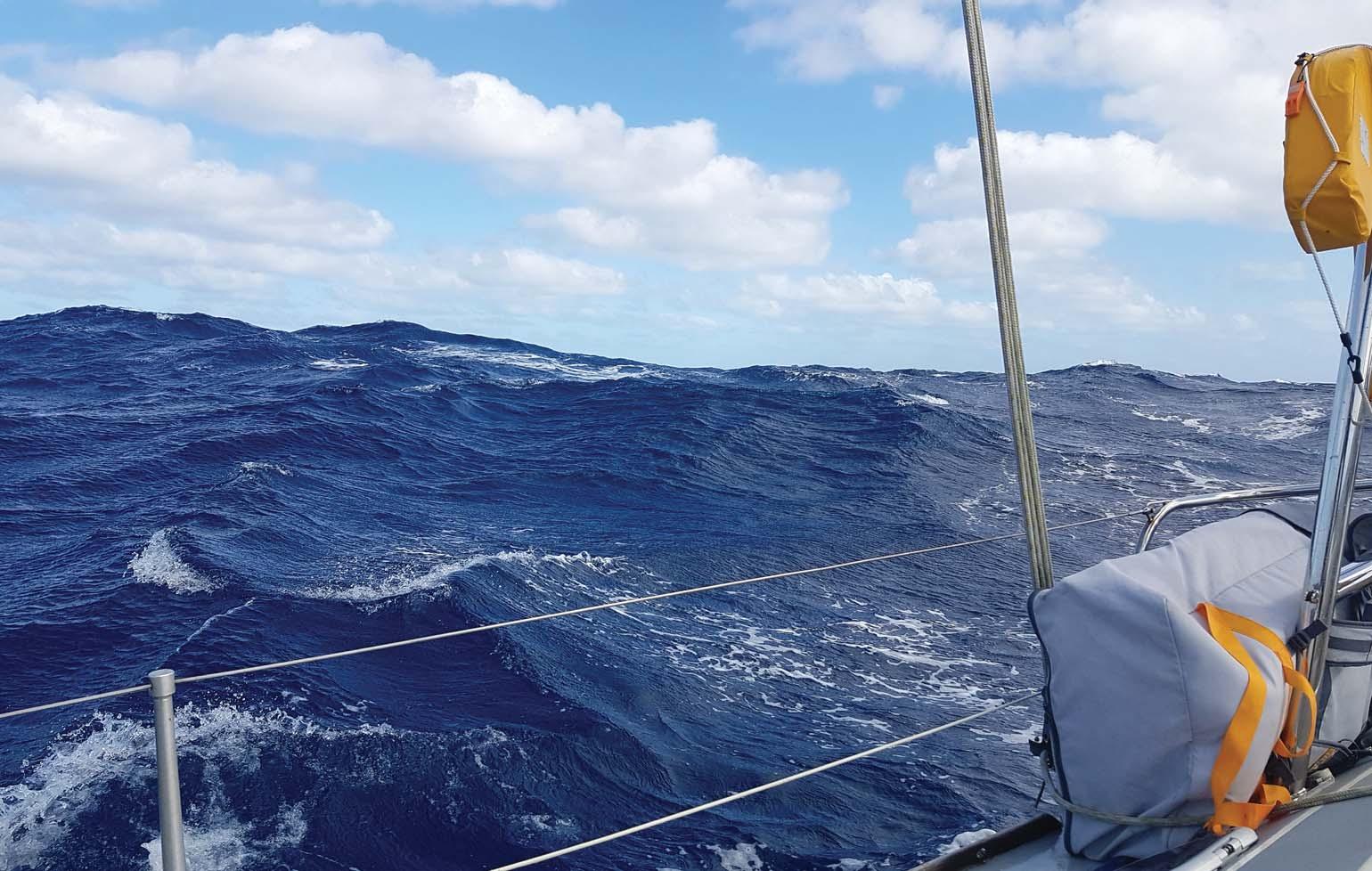

We winched up the anchor at dawn, hoisted the mainsail with three reefs, set the staysail and headed down harbour. We had to hold back for some shipping movements, including dodging the same French fishing boat that had caused us anxious moments on our way up to the islands. The next challenge was to escape the winds that accelerate through the seven-mile-wide channel between São Vicente and Santo Antão. We were soon enduring a bucking-bronco ride, motor-sailing against 20 to 30 knots of wind, a 1 knot current and a very steep chop. By midday, after three long tacks, we were finally clear of the islands’ influence and sailing in easier winds and seas. We shook out a reef and settled down for the long beat up the North Atlantic.

Egret made her way relentlessly, steered effortlessly by Papa Duggan*, her Aries self-steering gear. The plus points of sailing upwind rather than down are the steadier course, the higher output of the Airbreeze generator (which avoided needing to stream the towed generator), and an end to the annoying clonking from side to side of stuff in the lockers and drawers. Jealousy would overcome me sometimes and I would take over the wheel from Papa Duggan for a couple of hours – is there anything more satisfying than working a well-found yacht to windward in a stiff breeze?

It was three days before we were clear of the Saharan dust cloud – a relief to be able to breathe pure air, scan the distant horizon and see the moon and stars twinkling brightly in the night sky. With the crossing of 23°N on day five we sailed out of the tropics for the final time. The weather over the following week was mixed, with some gloriously clear, sunny days, others with the typical puffy white clouds of the trade winds and just a couple with rain. The wind strength was generally between 10 and 20 knots, with only one occasion when it reached 25 as we passed through a front. Even the direction of the trade winds behaved, shifting slightly from time to time but trending from 040° when we set out to 075° at about latitude 30°N.

We knew that Sula would be following in our wake, but most yachts departing Mindelo were heading to the Mediterranean via the Canaries, carrying extra fuel in anticipation of hours of painful upwind motoring. We were in SSB radio contact with several yachts that had left South Africa ahead of us, bound for Europe via the Caribbean. With the hurricane season approaching they too had set off for

the Azores, some encountering severe gales. Olaf, with his wife and three children aboard the Swedish yacht Miss My, had met gusts of over 50 knots in a terrible thunderstorm. They later spotted a dismasted, abandoned yacht. Jan, on the German yacht Voyager, told us that they had sustained damage and were returning to Martinique. After reaching land, we learnt that a catamaran had capsized in the same area with tragic consequences.

Six days out, we sighted a large sperm whale running parallel to us on our port side, blowing regularly. Then over to starboard we saw another adult with a youngster which kept leaping clear of the water like an exuberant child. We were relieved that they didn’t get any closer, and slowly left them astern. Several pods of dolphins came past, including one of around two hundred strung out in a long line. We were seeing more and more Portuguese men o’ war as we headed north, but they tended to be smaller than the ones we’d seen earlier. Towards the end of the leg we were surprised to see a juvenile loggerhead turtle swimming past.

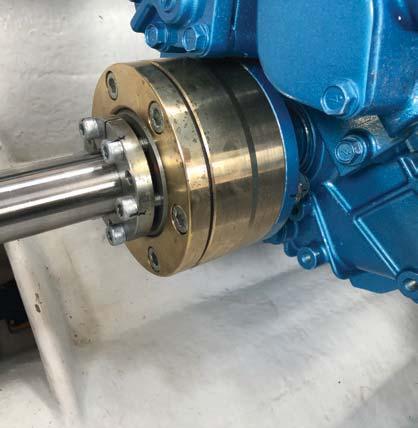

We had been monitoring a deep depression which was racing across the Atlantic with the centre forecast to pass just north of the Azores. On day ten, a change in the weather brought rain and fluky winds, eventually settling from the north. We made the best of it by remaining on starboard tack, heading northwest to pass behind the depression and so avoid the strongest winds. It was much chillier now, needing sweaters and oilskins on deck and a sleeping bag on our bunk. Next day the wind backed to the northwest so at last we could tack, something of a relief after so long heeling the other way. The breeze promptly died to less than 6 knots so we turned the engine on, but annoyingly it had developed a bad oil leak from behind the water pump. I rigged up a plastic cup to collect the drips, but had to stop the engine every three or four hours and return the contents to the sump, a tiresome, messy job. The wind gradually boxed the compass, eventually filling in at about 15 knots from the southwest, and after 30 hours of continuous motoring we were able to shut down the engine and enjoy the wonderful feeling of sailing with the wind abaft the beam.

We were expecting a front associated with the depression to pass over and, sure enough, the wind increased during the early hours of day fourteen, briefly up to 27 knots, accompanied by rain and a veer to the west. A lovely sunny day with a gentle breeze followed, but in the evening the wind died completely. We resorted to the engine and motored on through the night across an ever flattening sea. In the grey, pre-dawn light the islands of Faial and Pico appeared, like a pair of cymbals face down on a silk cloth. The excitement was building – we still experience the same frisson as we approach a new island after a long passage, even after visiting ninety of them! We berthed alongside the reception dock in Horta amidst an exuberant throng of yachts from myriad nations. It was June 2015 and we were back in Europe, just 1500 miles from home.

Egret second from the wall in Horta, flying her OCC burgee

Faial and Pico just visible in the dawn calm

Faial and Pico just visible in the dawn calm

“Join us today, we need all hands on deck if we are to have a living, thriving ocean for future generations to enjoy.”

- Liz Clark, sailor, surfer, and environmentalist

(Following the sad death in September of past OCC Club Secretary Anthea Cornell Stock – see page 215 – her account of probably her most dramatic sailing experience came to light. Although originally sent to a friend, permission has been given to reproduce it here.)

In June 2001 the OCC held a rally in the Azores, ending in Horta. I had to get the summer mailing out before leaving home, so didn’t have time to sail down and consequently joined the ‘air contingent’. The rally was a great success – well-attended and much-enjoyed, with boats converging from several directions. The Azores, and the Azoreans, remain delightfully unspoilt.

Not having to be home to a deadline, I was pleased to be invited to sail back on a member’s 46ft boat. Or, to be more accurate, I was beguiled by the idea of a sail back, though not so keen on doing it in a catamaran, which this was. I’ve never liked multihulls and never cruised in one. However, both boat and owner Mike – and the other five crew members – were colourful and enticing, so with just a twinge of concern I ditched my return air ticket and went aboard Dazzler. I was pleased to see that she had an escape hatch in each hull, and even more pleased that one was in my cabin in the port hull.

On Tuesday morning, 36 hours into the passage, the weather was light and we’d eaten a large and excellent brunch on the huge open bridge deck (I called it the ballroom). There were two people on watch, full main, spinnaker and small staysail were set and I was in my cabin writing. We seemed to be scorching along. I went into the chart room where the boat speed screen read 17 knots. Plenty fast enough, I thought, though maybe not for a catamaran – what do I know? I commented on it out loud and the owner, resting on the chart room bunk, eyes closed, snuggled into his pillow: “That’ll move us along nicely”.

Our hull lifted. Should it do that? It settled, then lifted again, throwing the owner out of his windward bunk and across the chartroom. I wedged myself, then became like a hamster in its wheel as the hull reared up and the whole yacht, like a giant panjandrum*, its not-quite-rigid frame creaking with the abnormal stresses, went oh so slowly, it seemed, into a half-pitchpole, half-roll, objects falling and clattering all around.

The helmsman had been steering on the windward wheel, on our hull, and as we got to the point of no return I was looking out of our hatch. I heard a voice say “Oh Mike – I’m so sorry”, and saw a figure, mercifully not attached to a lifeline, go into free fall and post itself feet first (luck rather than judgement, I think) through the hatch – at that point under water – of the other hull. The roll completed itself. The silence was eerie. A small, rhythmic lifting of the boat on the light swell. Then Mike’s voice, with perfect timing: “Oh, bugger!”

Mike and I were the only two in our hull. The other three who’d been off watch were in the starboard hull, along with the ex-helm. Peter, the other watchkeeper had, it turned out, been thrown clear of the boat, but easily swam back. Having checked that

all was well in the other hull he then joined us via our emergency hatch. Whatever else had been submerged or lost, the EPIRB was right in front of me. We set it off – or rather, we hoped we’d set it off. Its light was certainly flashing but you never know!

Unlike ours, the forecabin of the other hull had a watertight bulkhead when its door was shut (which it was) so that hull was floating higher in the water than ours. The four in there were moving around quite easily and able to recover one or two of their possessions. We were about waist deep in water, so set about finding a place each to lie as comfortably as possible out of the water and wait. Mike was on what would normally have been the underside of a shelf while Peter and I lay each side of the engine on what had been the underside of the cabin sole. It was oily, quite cramped (particularly for Peter, who was over 6 feet tall), and acid was dripping from the battery.

We talked about anything and everything – our homes, working careers, early life, family and friends, sailing experiences. A previous capsize (yes, it had happened to Mike and Peter before) and rescue. On that occasion they’d had to take to the liferaft as the yacht was sinking. We hoped that Dazzler, which was of polystyrene sandwich construction, would be unsinkable. Breakable though, if we were rammed by something large. We weren’t keeping a lookout and wouldn’t have been able to take avoiding action even if we’d seen something approaching on a collision course, while the VHF, fixed to the chart room bulkhead, was submerged well below the waterline. It was afternoon, there was quite a bit of ambient light and, I hoped, of air – I still haven’t worked out how long we’d have taken to use up the oxygen in our air pocket. The swell lifted us every few seconds, compressing the air in our ears and making the mast, mounted on giant ball bearings for feathering but now under tension, clank monotonously.

The water was at arm’s length below us. Various familiar objects floated into view –a sandal, my blister pack of blood pressure medication, my handbag (too far below to rescue) and the liferaft in its heavy PVC zip bag. We decided we’d better try to attach it to some part of the boat even though it was unlikely to go anywhere. I spent some time – I don’t know how long – biting through a tangle of light line (we had no knife between us) to separate off a usable length. I decided later that the liferaft was not just useless but positively dangerous. It was too big to push out through the escape hatch and too buoyant to drag down under water and out through the main hatch, and if it had inflated in the confined space we were in it would probably have trapped us.

Happily the EPIRB had done its job and a reconnaissance aircraft made a first pass at dusk, flying low. It made three or four passes in all, by which time several of us were on the upturned bridge deck, waving. We heard afterwards that they’d been calling us on VHF, but of course we weren’t receiving. Later we learned that two or three OCC yachts in the area had heard the plane calling us and ‘nearly been blasted out of the water by the strength of the signal’.

Our rescue ship was a 10,000 ton Blue Star Line freighter which happened to be in the area waiting for instructions. It was now dark. We stood on the rough bridge deck (normally the underside) and watched as she manoeuvred into position to windward of us, her raked bow towering over us and searchlights shining on us. She put rope ladders and nets over the side and fired rope-ends to us to tie round ourselves. We all made it aboard one way or another, but with few possessions apart from what we stood up in. I was wearing shorts and had bare feet. Also, though I had a life jacket on I had no lifeline, so had had to kneel on the rough bridge deck to hang on to the permanently-

rigged line while the yacht surged in the swell and we awaited transfer to the ship. When I finally got aboard my knees and insteps were heavily grazed and bleeding from the rough bridge deck – but these were minor injuries, all things considered.

The crew fed us and found us a cabin each (en suite!) and we were allowed to use the officers’ laundry/drying room, so by the time we reached Terceira – back in the Azores! – we were at least reasonably clean and well-rested. We were taken ashore in a local pilot boat complete with local TV interviewer and cameraman, who made much of my grazes! Two of us were taken straight to out-patients at the local hospital, and a hotel was organised for us all. The Portuguese were very kind and efficient, though we weren’t exactly the best-dressed and groomed hotel guests!

It took us a couple of days to organise emergency money and book flights home but Dazzler, the capsized yacht, is still drifting somewhere in the Atlantic, in one or several pieces.

The chart will tell what the North Atlantic looks like. But what the chart will not tell you is the strength and fury of that ocean, its moods, its violence, its gentle balm, its treachery: what man can do with it, and what it can do with men.

As is often the case with a grand expedition, the original idea is sparked by something that captures our attention and takes root deep within our imagination. Hours of contemplation and dreaming create plans seemingly beyond our fingertips until we take a single step in the right direction. That was certainly the case for me. The longest passages I had sailed were a couple of weeks exploring the Outer Hebrides and the Norwegian fjords. I had never stepped aboard a boat outside of Europe or crossed an ocean. During Covid lockdown, however, I read an inspiring book by Liz Clarke entitled Swell*. A young lady with a flair for travelling, she acquired a boat and set sail around the world. Passing down the American coastline and across the Pacific Ocean, she made it to Tahiti. Her description of her experiences made me eager to find a way to reach the same destinations.

As a 20-year-old, just beginning my third year of training to become a doctor, I have ambitions of being an expedition medic, travelling to all corners of the world and having wild adventures. Due to a placement beginning in autumn 2022 my holidays were about to become very limited so I wanted to make the most of my final long summer and do a worthwhile sailing trip. My dreams came true when I found a boat sailing from French Polynesia to Fiji over the summer which needed crew. With help from the OCC’s Youth Sponsorship Programme I booked my flights.

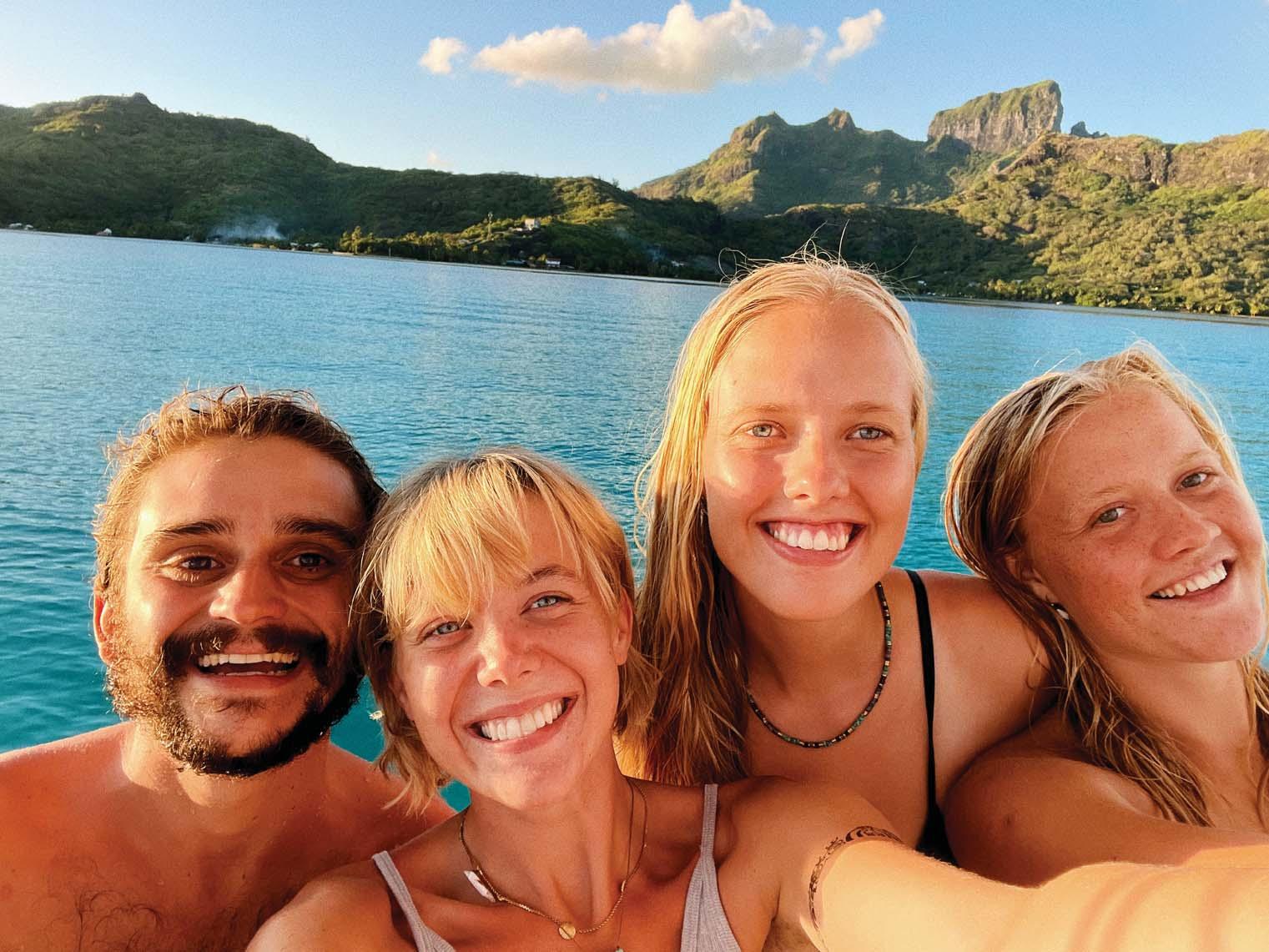

Pania is an Omega 56 – a GRP cutter-rigged sloop with a dagger keel, based on a Baltic 54 hull – and we were an international crew. Her owners are Jelle and Skye, a Danish/ New Zealand couple with their 3-year-old son Abel, and the rest of the crew consisted

* Illustrated edition published by Patagonia in 2018 and available in both hard cover and for Kindle. ISBN 978-1-9383-4054-3

Pania’s crew in Mo’orea

of Claire (from the USA), Alberto (from Spain), Lina (from Denmark) and me (from England). This rich cultural variety created a vibrant, dynamic atmosphere in the boat – new flavours were expressed in the cuisine, typical traditions brought to the table and stories from people’s backgrounds shared as we melded into a new family onboard.

During the first couple of weeks we sailed round the islands of French Polynesia, starting in Tahiti where we stocked up on food supplies and bottled gas to last us for the next month. Arriving in time for ‘Tahiti National Day’ we became immersed in the festive cultural traditions, watching traditional dances which showed off the graceful but powerful nature of the dancers. Competitions were held in which local men ran races while balancing bananas on bamboo poles, straining their lean bodies round an assault course while an old man cheerfully led the way on his bright yellow motorbike, tooting honks of encouragement and hyping up the crowd.

Sailing was delayed by a couple of days when the meteorological service issued warnings of strong winds and swell, and we found out later that extensive damage occurred throughout French Polynesia due to coastal flooding. Global warming and rising sea levels are evidently having a large impact on these islands and it was eye-opening to see the damage first hand. When the swell had died down we made the short passage across to Mo’orea. I sat on the bowsprit with my eyes peeled, keeping a lookout

Pania in Papeete, Tahiti

Cook’s Bay, Mo’orea

Pania in Papeete, Tahiti

Cook’s Bay, Mo’orea

for bommies* and whales. Despite there being recent sightings of large numbers of humpback whales passing through the warm waters of Polynesia for mating season, the only wild creatures visible were the rest of the crew.

Mo’orea is very rugged with jagged volcanic mountains. We anchored in Cook’s Bay and explored the heart of the island, climbing narrow paths winding up the steep slopes and leading to stunning viewpoints. Bamboo forests, pineapple fields and trees bursting with exotic fruit of all kinds lay before us. The translucent, turquoise bays beyond were sheltered by the reefs, shielding the island from the surrounding deep blue Pacific Ocean.

After a couple of days we made the overnight crossing to Huahine, just over 100 miles away. Far more remote, the island has managed to retain the alluring authenticity of early Polynesia and is an immense tropical jungle, with vanilla plantations, coconut trees and watermelon fields. The vibe was chilled and family-oriented. During our time there the swell was strong and the waves fairly epic. In Swell Liz Clarke describes surfing in this part of the world, and I’d been longing to do the same. I swam out to meet the local experts and an older Polynesian man took me under his wing. He lent me his board and gave me small shoves every time a large enough wave came along. I had a smile of glee as I caught my first one, but the sight of the sharp coral reef passing barely beneath the board made me nervous and I came crashing down, scraping my skin. He patiently tutored me for a couple of hours on the ways of the water, and gave me advice on the most effective way to catch the lip of a wave and plunge down its face in an attempt to catch a barrel ride. I gradually improved. Drinking a beer, we leant against his truck watching the sunset. He reminded me of Big Z from the film Surf’s Up as he casually revealed a lifetime of surfing experience, reminiscing about international events in which he’d competed when he was younger. When we sailed

* A bombora – often abbreviated to bommie – is an Australian term for an outcrop of coral reef higher than the surrounding reef platform which may be partially exposed at low tide, and also for an area of large sea waves breaking over a shoal some distance offshore. Thank you, Wikipedia!

on towards a new anchorage he lent me the board for the next week to practise. In the end I spent more time surfing by holding a line trailing from the dinghy rather than on the waves, but very enjoyable nonetheless!

In Ra’iatea we were able to hitch lifts to the key historic sites such as the Marae Taputapuatea*. Once considered the central temple and religious centre of Eastern Polynesia, it holds significant testimony to traditional Polynesian culture. We anchored in the Te Ava Mo’a channel (the sacred channel) located in front of the marae. It is said to be the home of Tumura’ifenua, the mythical giant octopus that supposedly spreads its tentacles to all of the archipelagos of the Polynesian triangle.

When we visited smaller islands only accessible by boat we used a stern-line tied to palm trees in conjunction with a bow anchor. We hung up hammocks, built fires on the beach and collected crabs for dinner. Occasionally we would meet interesting local people living remotely. One old man owned a shack on the beach. Paddling up to Pania in his kayak one morning we were invited for breakfast, and the following day we found him busily building a fire. He set the men to work cutting open coconuts and

A morning of traditional craft

grating them ready to make coconut bread. Meanwhile we women were led to his shack, where he had a wide assortment of beads and shells. As a professional costume and jewellery maker, his nimble hands were used to stringing together delicate combinations and creating elaborate pieces of artwork. We worked by his side all morning attempting to replicate his designs, while he kept reinforcing the idea that mana (energy) ran through us all.

* A marae, malaʻ e, me ʻ ae or malae is a communal or sacred place that serves religious and social purposes in Polynesian societies.

Our final destination in French Polynesia was Bora Bora. Making our way through the outer reef into the shelter of the lagoon was challenging due to the rapid current that flows out through the narrow channel. You have to enter the lagoon only through passages indicated by triangular navigation marks and, as is typical in this region, the water depth changes

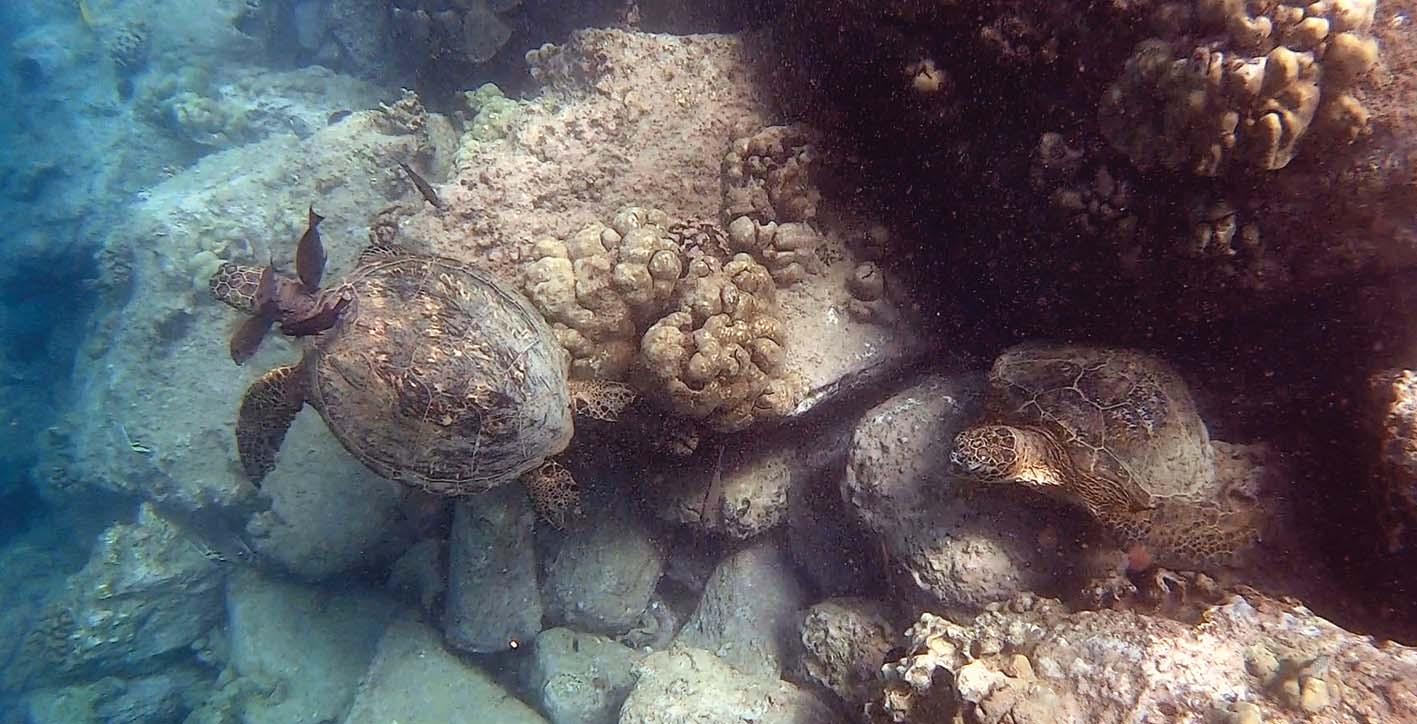

almost instantaneously. We passed a boat that had become trapped on the reef and been abandoned by its crew, but fortunately we made it through safely and the panoramic views beyond made it well worth the struggle. During our stay we descended into the translucent depths with our SCUBA tanks, gaping in awe at the magnificent manta rays and turtles that circled us or squirming nervously as sharks approached within close proximity.

After a month of island-hopping we began the ocean crossing from Bora Bora to Samoa. Raising the mainsail and unfurling the genoa we raced across the still lagoon water, through the pass and onto the open ocean, anticipating an exciting passage. Day by day the crew started working more effectively as a team and became slicker at their tasks – sheeting in the sails more quickly, helming more precisely and keeping a sharp lookout for other boats or unfavourable weather systems

Anchored at Raiatea with a line ashore

The crew in Bora Bora

Anchored at Raiatea with a line ashore

The crew in Bora Bora

on the radar. For the first four days we averaged 5 ∙ 5 knots on a run with the genoa fully out, occasionally aided by the engine and mainsail. The halyards were cleated off at the mast and, unlike in some boats, the lines did not lead back to the cockpit. I enjoyed scrambling along the leeward side of the boat to the mast, dangling my full weight on the halyard to haul up the sail and then finishing it off on the winch. Clipping onto a shroud in the middle of the night, I could watch the bow plunging through the waves in the moonlight with a blanket of stars illuminating the water. I was always amazed to look up into the starry night, then down into the depths of the ocean, and realise that I was just a speck in this vast universe.

On passage everyone found their routines. Each day began with a high pitched, enthusiastic cry, “Hey Dude, do you want to help me build a hydroelectric engine?”. Having grown up mainly on board, Abel knew the boat inside out and was always trying to break into the tool box, undoing and fixing screws, or stringing together phrases he had picked up from previous incidents. “Papa, the macerator broke. We must do some serious engineering to repair the electrical cabling!”.

The rest of the day would flow into one, with people alternating between reading, being on the helm, giving a massage or doing a craft project such as crocheting, wood carving, painting etc. Bucket showers took place on the transom. A couple of times when there was no wind we furled the genoa and I jumped off the bow and swam to the stern, but that quickly stopped when I saw the size of the shark bite out of a fish on the end of the line. I didn’t fancy being caught in the jaws of that beast! The daily Rummikub* competition was played with a repercussion in the mix – washing up duty for a week, bilge-scrubbing, fridge maintenance, and so on. At the end of the day we would all sit on the bow, hot chocolate in hand, watching the sun go down. I particularly enjoyed perching on the bowsprit playing the guitar. Night watches were exquisitely quiet. Not a sound could be heard other than the gentle clanking of the

after a while heard a loud sound. Pania has a spade rudder and, on checking the boat, the owner found that the welds on the stainless top bearing of the rudder stock had failed. This allowed excess movement and caused the cable steering to fail by coming off the quadrant and getting caught and kinked in the blocks.

He immediately hove to to limit the rudder’s movement and called an emergency meeting of the crew. He explained that we were in danger of sinking if the hull became damaged, and though he would attempt to strap the rudder down using cable ties, in the meantime we needed to start working on Plan B – taking to the liferaft. The straps and cable ties were insufficient to keep the rudder in place securely against the force of the waves while they remained so large, so we decided it was safest to drift until they subsided.

Sorting through the medical kits in preparation for taking to the liferaft

Watching the large swells approaching

boat and the occasional “you still awake?” from one’s watch partner. I relished the idea of being the only person awake for miles around!

For the first few days the conditions were calm. A couple of squalls passed over but we mainly had fair weather conditions. On the fifth day, however, the wind progressively picked up until it was howling at 35 knots –in Polynesia a maramu or strong southeast wind. The waves reached 6m and the boat was under a lot of strain. During the night I kept getting tossed out of my bunk and desperately clawed at anything I could cling onto to keep myself from falling head first onto the cabin floor. We reefed the main and rolled in the genoa, but

For the next few hours we worked together to think through the Life of Pi scenario, packing important documents, food supplies and warm clothing into dry bags. Abel came up to me lugging a large box of Lego and, with a solemn face, declared, “Abi, I’ve packed the Lego up, ready for the lifeboat!”. If we’d had to abandon the boat those Lego pieces might have been the best thing we’d packed, at least for keeping our minds occupied! As the resident medical student I was responsible for going through our medical supplies – it’s not often you have to imagine yourself bobbing on the ocean 500 miles from the nearest land, and I had to make quick decisions about what would be vital when exposed to the elements.

We remained hove-to for the next 36 hours riding out the heavy weather, drifting in a westerly direction towards the Cook Islands. A Pan-Pan was broadcast and we were tracked by the New Zealand and American coastguards, but after the winds died back down to 15 knots we were able to sail the last few miles to Suwarrow using the emergency tiller. We sailed in through the pass in the early morning and I peered out of my porthole

Safely anchored at Suwarrow

Safely anchored at Suwarrow

to see a golden beach fringed by palm trees. We spent a couple of days of bliss anchored in the shelter of the island but, due to Covid restrictions, were not allowed ashore. I spent the majority of my time at the top of the mast, sitting in a dream-like state looking out over the island. An Australian couple we had met previously tied up alongside hoping to aid us with the welding using their generator, as a fuse in our inverter had blown earlier in the trip. We had a celebratory meal to commemorate reaching land safely, popping open the champagne and creating as much of a banquet as a bunch of tins can achieve. Accompanied by a bottle of rum we chatted away well into the night, hearing tale after tale of the Australians’ exciting adventures. A very merry evening!

It took us five days to sail from Suwarrow to Apia Marina, Samoa, crossing the International Date Line en route. We’d been longing to reach Samoa and be able to have our feet on solid ground again. Customs came out to meet us and escorted us to their pontoon, and after a thorough search of the entire boat we were granted permission to stay. We spent the following days visiting the To Sua Ocean Trench, cave pools, large waterfalls and the giant clams. Our tour guide was an energetic Samoan taxi driver who chattered and chuckled the whole time. With the wind racing through the

The spectacular fire dance at Samoa

The spectacular fire dance at Samoa

To Sua Ocean Trench, Samoa, 30m deep and only accessible via a long ladder

open windows and the music turned up high, she flew along the island roads joyfully chanting, “I drive, you party. I drive, you party!”, hands barely on the steering wheel. Partying and dancing must feature prominently in Samoan culture as on another evening we watched a most spectacular fire dance, standing transfixed as the fire sticks were spun increasingly rapidly and the music became more intense and passionate. Were these magical dancers even human?

Waking at 4am one morning we were able to visit the Old Apia Market. I enjoyed chatting with the local fishermen and hearing about their lives and we bought freshly-caught crayfish and crabs. A delicious barbecue took shape as we watched the sunset. We also visited the Robert Louis Stevenson Museum. Having fallen into disrepair the building, once his home, has now been renovated and houses paintings, furniture and memorabilia from his time. We were given a tour by a young Samoan lady and heard tales of his travels across the Pacific and his final years on the island. We were impressed to realise that, over 100 years earlier, the writer had done

Samoa fish market

Samoa fish market

exactly the same passage as we had, but lacking our navigation systems, radar and ability to contact the coastguard if anything went wrong. The bookshelves in his study contain copies of his most famous books in both English and Samoan, translated to make his works accessible to local people. The Samoans fondly nicknamed him ‘Tusitala’, or Teller of Tales.

On the evening of the fifth day we untied our lines and set off on a broad reach for the hazy horizon. We rolled out the genoa and fully raised the main after passing north of Savai‘i. Over the next couple of days the winds were light and we made barely 3∙5 knots over the ground. We replaced the genoa with the gennaker (a cross between a genoa and a spinnaker) and alternated sailing dead downwind with sailing on a broad reach. The

The Robert Louis Stevenson Museum, Samoa

Jelle and Alberto with a mahi mahi

The Robert Louis Stevenson Museum, Samoa

Jelle and Alberto with a mahi mahi

owner set a course via Wallis Island, a small atoll north of the direct course to Fiji, to optimise the time sailing on a broad reach. We had much better luck with our fishing lines and caught a couple of tuna that we gutted and cut into steaks. Then, on the last day, we caught a mahi mahi. It was more than a metre long and a glorious combination of vibrant colours. Our bellies were fit to burst that night!

After two months aboard Pania we reached our last stop – Fiji. We sailed upwind for the final few miles and I took the helm, enjoying feeling the power of the boat as we cut through the water. Small atolls started building on the horizon as we approached Fiji. We reached Vuda Marina in the evening and were welcomed by a whole cluster of marina staff who gathered together and sang the boat home. We had reached our final destination!