KEVIN MORAN is a children’s author and primary-school teacher from Castlebar, County Mayo. He was runner-up in the Staróg Prize for children’s ction in 2023. He wrote his rst book, ‘Ghost Invaders’, when he was six. It remains buried in an attic, unpublished. When not writing, he can often be found on the beach near his home in Dublin, being walked by his surprisingly strong golden retriever.

First published 2025 by e O’Brien Press Ltd, 12 Terenure Road East, Rathgar, Dublin 6, D06 HD27, Ireland.

Tel: +353 1 4923333; Fax: +353 1 4922777

E-mail: books@obrien.ie; website: obrien.ie

e O’Brien Press is a member of Publishing Ireland.

ISBN: 978-1-78849-526-4

Text © Kevin Moran 2025

e moral rights of the author have been asserted.

Editing, design and layout © e O’Brien Press 2025

Cover illustration by Tomislav Tikulin

Cover and text design by Emma Byrne

Illustration on p. 267 by Emma Byrne

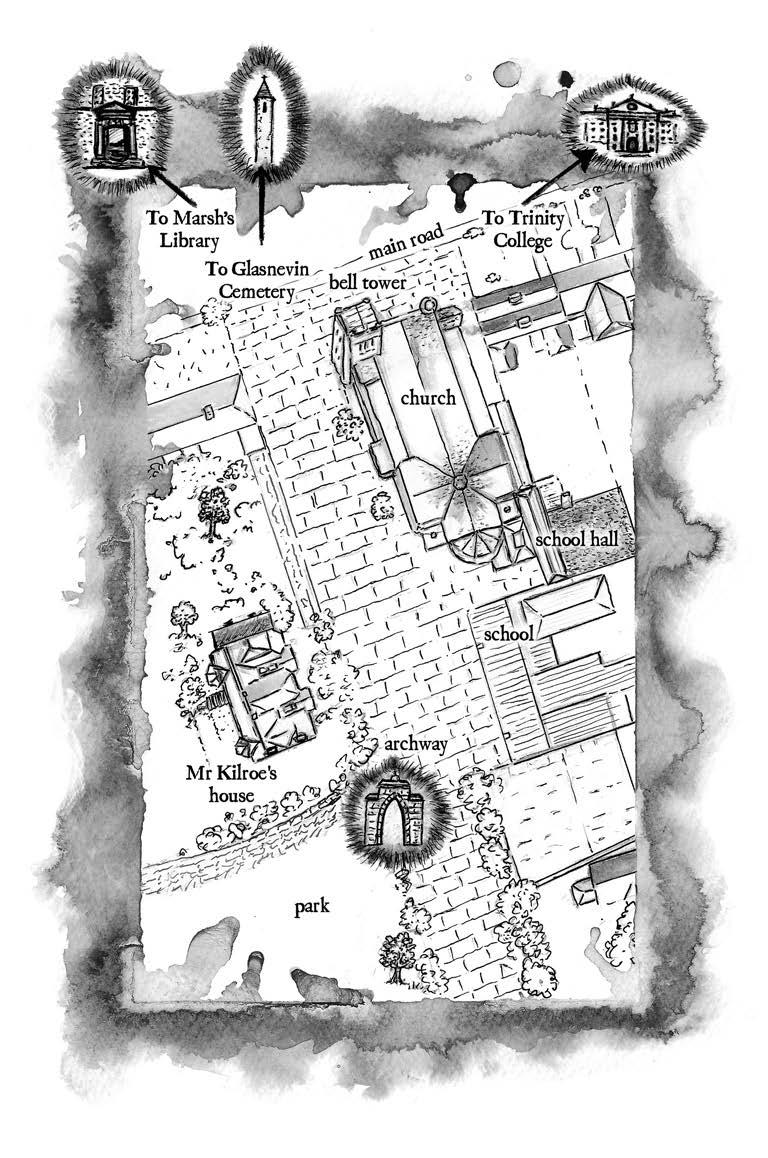

Map by Bex Sheridan

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including for text and data mining, training arti cial intelligence systems, photocopying, recording or in any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

All the characters in this book are ctitious. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

29 28 27 26 25

Printed and bound by Nørhaven Paperback A/S, Denmark.

e paper in this book is produced using pulp from managed forests.

The O’Brien Press received nancial assistance from the Arts Council to publish this title

‘I only lit a small re.’

As he said the words, Jack winced. In the school’s long history of terrible excuses, it was surely in the top ve. Conan, Yash and Jerry – his fellow inmates at lunchtime detention, sitting with him in a circle of chairs in their empty classroom – glared at him. He tried again.

‘Look, how was I supposed to know a few balled-up pieces of paper in the toilet bin would cause that much smoke?’

Yash rubbed his split lip and rolled his eyes. ‘You didn’t know re causes smoke?’

A sudden rage bubbled beneath Jack’s skin and a hundred nasty comments fought to be rst from his mouth. But the look on Yash’s face – part smug, part disgusted – left Jack speechless

with fury and he clamped his mouth shut. Besides, Jack was in enough trouble. e re was one thing, but the punches thrown as they all scrambled to escape the smoke- lled toilet were worse. Even if some of them were accidental.

‘A fire, Jack,’ said Conan, pressing an ice pack to the back of his head. His doe eyes were wide with shock. ‘Even for you, that’s bad.’

‘Relax,’ said Jack, dabbing at blood on his lip. ‘No one died.’

‘I could ask the caretaker if I can build a re escape beside the urinals,’ murmured Jerry. His broad shoulders were hunched over as he focused on a watch he had balanced on his knee, taking it apart with a tiny screwdriver. ‘In case it happens again.’

Yash stared at him like he was unwell. ‘Or Jack could stop lighting res.’

Jerry shrugged and pulled open the watch face. ‘Or that.’

Jack hu ed and slid from his seat. A vast grey sky was framed by windows that stretched to the classroom’s ceiling. He rested his chin on the windowsill, watching as rain pelted the brittle panes, a thousand tiny ngers hammering to be let in. A stone’s throw from the classroom window, across a pathway of rainslicked cobbles, a row of red-brick Georgian houses were nestled together, shielded by a high stone wall and the claw-like branches of bare trees. In the wall, a Gothic stone arch led to a tiny, nowwaterlogged park. It was a quiet spot in the middle of a bustling city, like their school existed in its own little time warp.

Behind him, Conan and Yash began to panic and tried to place blame. is was all new to them, he supposed: the sweaty palms, the knots in your stomach as you waited for your teacher to storm in and bite your head o . For Jack, the drama was all a bit much.

e barely-a- re he’d lit was just a distraction. A very, very good distraction. Not that he could admit that now. He was about to whip around and tell them to shut it when a ash of movement caught his eye.

A tall, gangly gure made its way across the cobbles outside the classroom window: Mr Kilroe was less a man and more like a gnarled tree draped in a dark suit. Wrinkles like crevices ran across his face and square black sunglasses concealed his eyes. Grey wisps of hair billowed across his head like rolling fog.

‘Jack, I think you should sit down,’ came Conan’s trembling voice. ‘We need to get our story straight.’

Jack kept his eyes on the old man. ‘You were caught ghting in the bathroom, Conan, not burying a body in the woods.’

Mr Kilroe had lived across from the school for as long as Jack could remember. He’d never seen him speak to anyone or crack a smile. He watched now as the old man stopped in front of the stone archway. He rested on his cane, as oblivious to the rain as a corpse is to the sun. His thin lips moved quickly, as though he was speaking into the empty space inside the archway, and Jack wondered if he should call someone to help – Mr Kilroe had clearly lost his mind. en the old man lifted his right arm, st

clenched, and traced the line of the archway. His long, wrinkled neck craned back and he gazed up at the arch as if waiting for something. Suddenly, Mr Kilroe gave a roar of pain and unclenched his st. Jack glimpsed what seemed to be tiny shards of yellow stone fall from the old man’s hand and a trail of blood from where they had pierced his skin.

‘Jack, please sit down,’ said Conan again. ‘Ms Murphy and Mrs Lynch are just in the corridor …’

But before Jack could turn, a gash of lightning lit up the grey October sky and Ms Murphy’s re ection appeared in the window.

She stood in the doorway, arms folded across a black tracksuit top and lips pursed. She meant business.

‘Nice entrance, Miss,’ said Jack, turning from the window. Ms Murphy frowned. ‘I didn’t plan the lightning, Jack.’ She crossed to her desk and jabbed a nger at where the other boys sat in a circle. ‘Sit.’

Jack threw his head back and groaned before slouching in a chair next to his fellow inmates in their bottle-green uniforms. Conan shu ed nervously on his chair, his legs bobbing up and down as he chewed on a thumbnail, saliva glinting o his braces. He stared at Jack with dopey eyes from behind a shock of wild, blond hair, as though pleading with him to tell the truth, as if he could send the message telepathically.

Which, knowing Conan, he probably thought was possible.

Ms Murphy leaned against her desk and shook her head. ‘I

don’t even know where to begin with the four of you.’

‘We all know who started it, Miss,’ said Yash, rolling his split lip between his ngers. Jack’s rage boiled up at the sound of that voice. ‘I’m not sure why we have to waste our lunch break just because Jack is a perennial screw-up.’

ere it was. Jack shot to his feet and the chair skittered back. Jerry reached out a shovel-like hand and planted him down again.

‘Don’t make it worse,’ said Jerry. Although he was big enough to pass as a teacher, his voice came out as soft as silk.

‘Jack, that’s enough,’ intoned Ms Murphy, raising her hand. ‘And need I remind you that the re isn’t the only reason you’re all in here?’

She blew a strand of blonde hair from her eyes and glared at each of them in turn, Jerry with his slowly swelling eye, Conan with an ice pack to his head and Jack and Yash with their split lips.

‘Now I’ve no way of knowing exactly who decided to start the world’s worst barbecue in the school toilets,’ continued Ms Murphy, and her eyes lingered on Jack, much to his o ence. (He’d done it, of course, but still.) ‘Nor do I know why Jericho, who’s only ever been in trouble for leaving school to rescue a bird, has got a panda eye. Or why four boys who never so much as glance at one another in class were thrashing around on the ground like a bunch of wild dogs. So let me ask you: have you got anything to say?’

Her words echoed around the classroom.

It was Conan who broke the silence.

‘“Like a bunch of wild dogs”,’ he said, with a nervous machinegun giggle. ‘You love a good metaphor, Miss.’

‘Actually,’ said Yash in his annoyingly prim teacher voice, ‘that last one was a simile.’

Jack let out an exaggerated groan. ‘Oh my God, if you don’t shut up, I’ll set myself on re.’

Conan’s face lit up with that same goofy smile Jack had known all his life. It occurred to him that Conan thought Jack was defending him. He could smile back, of course. Even a slight grin would be a bit of a peace o ering. e edges of his lips even began to twitch. But in the end, he went with an always-reliable eyeroll.

Besides, he’d lit the re for Conan. What more could he do for him in one day? e whole point of the re had been to get people out of the toilets. But in the scramble to escape, elbows hit jaws, shirts were pulled, legs were buckled. By that point, it didn’t really matter who’d started the actual ght. Jack bit his split lip and winced. One of the few good deeds he’d ever done and he couldn’t tell anyone. Still, it had worked. Everyone was ne. Well, apart from the odd bruise or cut.

‘Are we going to be expelled, Miss?’ asked Jerry in the mildly curious tone of someone asking what time dinner would be. He didn’t even look up from where he was resealing the back of the watch with his miniature screwdriver.

Ms Murphy exhaled and glanced at the clock. ‘ at’s not my

call, Jericho. But I wish I could make you understand that this is not how friends are supposed to act.’

Jack clicked his tongue. ‘We’re not friends, though, are we?’

He ignored Conan’s hurt-puppy look. It was true. ey didn’t speak to each other in class or outside school. As far as Jack was concerned, Yash was a nerdy rich boy, Jerry was a large suitcase with nothing in it, and he’d been trying to shake Conan o for years.

ey were classmates, stuck together because of two things: age and geography.

Pellets of rain continued to batter the windows, hard as hail. Jack doubted the panes would last long against the storm brewing outside. He’d broken those windows twice. Once with a football (accidental) and once with a rock (intentional). e Perp – or Our Lady of Perpetual Su ering, to give the school its full name – had been old back when Jack’s granddad was a pupil. Now, it was ancient. He’d heard Yash say it had been built in the 1800s, because of course Yash liked to say that sort of thing. Paint peeled o the walls, exposed pipes clattered and choked when the heat came on and, in one extreme case, a mushroom had grown through the oorboards beside a sink. So Jack put his hope in a gust of wind toppling the whole thing down: no school, no detention.

‘Look,’ said Ms Murphy. ‘No one expects you boys to be the best of pals. But being classmates is like … being on a team. You

look out for each other no matter what, even if you don’t always see eye to eye.’

She rounded her paper-strewn desk and pulled open the top drawer, shing out a little gold disc attached to a red ribbon.

‘See this? It’s my All-Ireland schools football medal from when I was your age. I had some great friends on that team. And some girls I wanted to avoid entirely. Some were arrogant, some were vain, some were just plain boring.’

‘Great lesson, Miss,’ said Jack, attempting a smile.

She glowered. ere was a line, he understood. On one side of it, she found him funny. On the other, he drove her nuts. But he could never quite be sure where that line was.

Being his sports coach as well as his teacher gave her an extra air of authority. Jack also thought it meant she understood him a little better than most.

‘But none of that mattered,’ she continued. ‘We worked together and looked out for one another. We made each other better.’

She passed the medal to Conan, who cradled it like an ancient artefact and looked genuinely inspired by the whole spiel. As the medal was passed around, Jack took another glance through the window. His spine straightened. Mr Kilroe was still there, lashed with rain and staring directly at him through his black sunglasses. Had the old man died on his feet? But no, Jack could see a sickly white hand clenching the cane for support. He imagined that hand feeling like ice.

Something cold was pressed into Jack’s palm. He jolted.

‘Relax,’ said Jerry.

Jack reddened and looked down to see Ms Murphy’s medal. Embossed onto it was an image of two girls reaching for a ball in mid-air.

And then he spotted the date on the medal.

‘Miss!’ said Jack, trying to claw back some con dence the only way he knew how. ‘ is is from, like, ten years before we were born! I never knew you were that old.’

Conan almost leapt from his chair. ‘You can’t call a teacher old!’

‘You can’t call a woman old,’ added Jerry.

‘You shouldn’t call anyone old!’ groaned Ms Murphy, with an exasperated shake of her head. ‘And I’m thirty-three, for God’s sake.’

Jack allowed himself a smile, only because he knew he’d stayed on the right side of the line and that, deep down, Ms Murphy appreciated the joke. He handed the medal back to her and chanced a glance through the window once more. Mr Kilroe stood in the same spot, silent and staring and bu eted by the wind. Ms Murphy followed Jack’s gaze. When she saw the old man, she smiled weakly and waved.

‘What’s wrong with him?’ said Jack, unnerved by Mr Kilroe’s stare.

Ms Murphy inhaled sharply and paused, as if trying to think of the right way to respond. ‘Nothing’s wrong with him, Jack.

He’s just … old.’ en, seeing the look on his face, she added, ‘Actually old, not born-in-the-nineteen-nineties old.’

Conan’s eyes stretched wide. ‘I heard he killed someone.’

Yash tutted. ‘ ere’s no evidence of that.’

‘He’ll be after us next,’ continued Conan in a scared whisper. ‘ at’s if my parents don’t kill me when they hear about this.’

‘Conan, I don’t have the patience to listen to one of your doomsday scenarios today,’ said Ms Murphy with a sigh. ‘It’s detention, not the end of the world.’ She planted her hands on her knees and stood up dramatically. ‘ ere’s ten minutes of lunchtime left, so I’m o to nish a presumably very cold bowl of soup. You boys can sit here and think about what you’ve done.’ She crossed to the door and swung it open with force. ‘And if at all possible, nd a way to be in the same room together without killing each other.’

As her runners squeaked away down the corridor, Jack looked once more out the window. Sheets of rain swept sideways across the cobbles. As he squinted, trying to make out the old man’s shape, a blinding fork of light hit the cobbles and scorched the spot where he’d stood. A chair rattled, Conan’s probably. But Jack kept watching a moment more to con rm it: the old man was gone.