11 minute read

II. What waste management model to support policy?

The purpose of identifying the levers that enable a shift towards waste valorisation is to give waste management actors an overview of opportunities. Clearly, each situation is different, each territory has its own specificities, and it would be pointless to seek to systematically apply the same levers across the board. Three main models emerge, all in fact implemented in parallel in each of the cities, but with different objectives and applied to different populations and waste types.

1. A centralised, unified and linear model

Advertisement

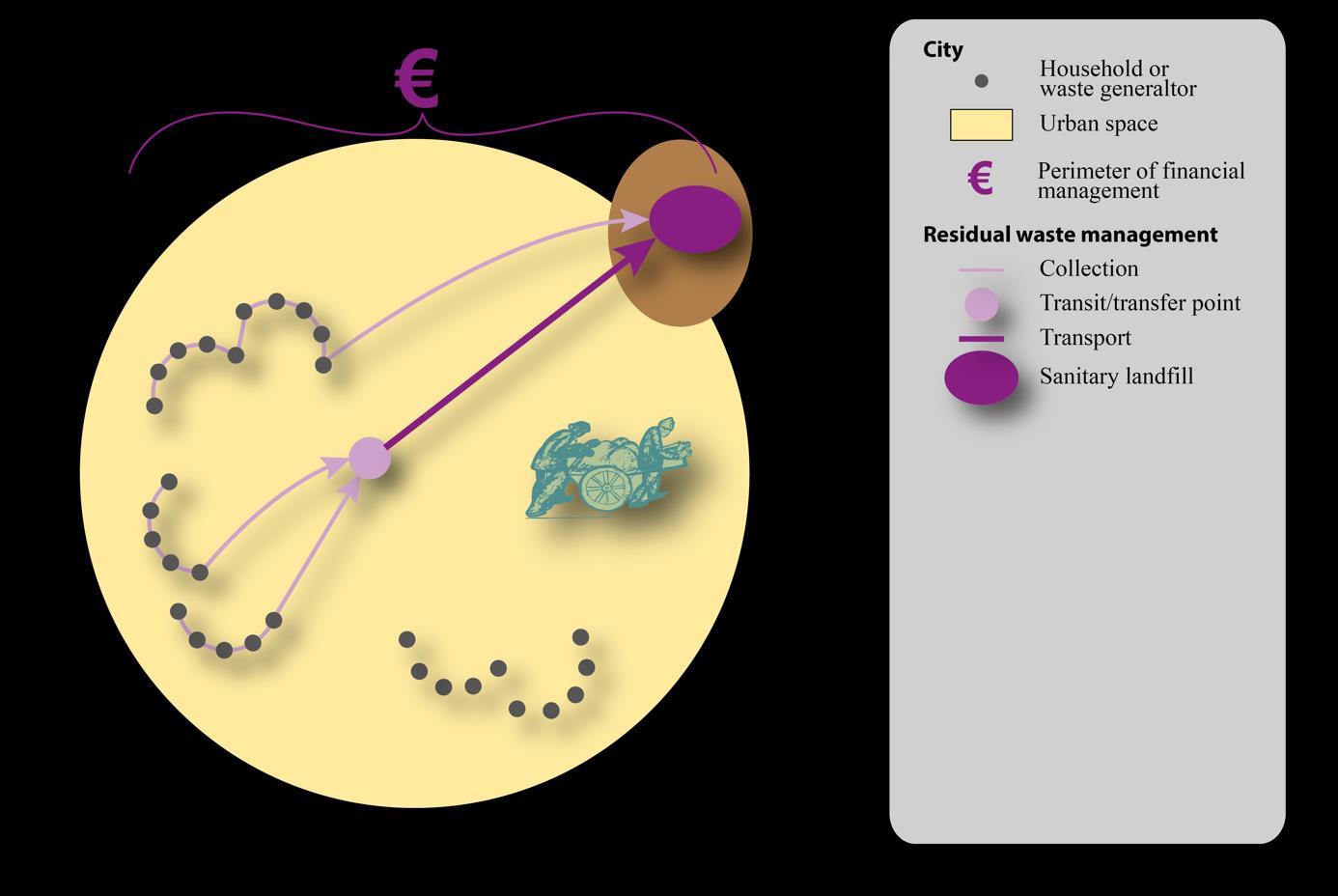

The first model foregrounded by the cities studied is at the same time centralised, unified and linear. It adopts the same goals as those generally set by global North countries with a focus on public health objectives. It aims to remove waste from the urban space to prevent health risks for residents and, as far as possible, also control the disposal of this waste to reduce its environmental impacts.

A model that mimics global North practices

The actors implementing this model aim for waste management that is: - Centralised in the hands of a single actor at the metropolitan scale in order to compensate for inadequate management of the urban area in most of the cases studied. This helps to gradually strengthen the municipalities. If no metropolitan authority exists (the case in four of the six cities), the state and its ministries take direct responsibility for management. This thrust for centralisation sometimes seem to reflect a wish to prevent the empowerment of potential political competitors at the local level. - Unified, meaning that the same municipal public service is provided to all citizens. This corresponds to a vision of theoretical equality, offering the same door-to-door service to all. - Linear, as the main objective remains to limit health risks and thus move waste away from the city. All waste streams converge towards a single sink – a (more or less controlled) disposal site – to avoid dispersing waste to sites not directly controlled by the central actor.

Figure 25.

Centralised, unified and linear waste management model

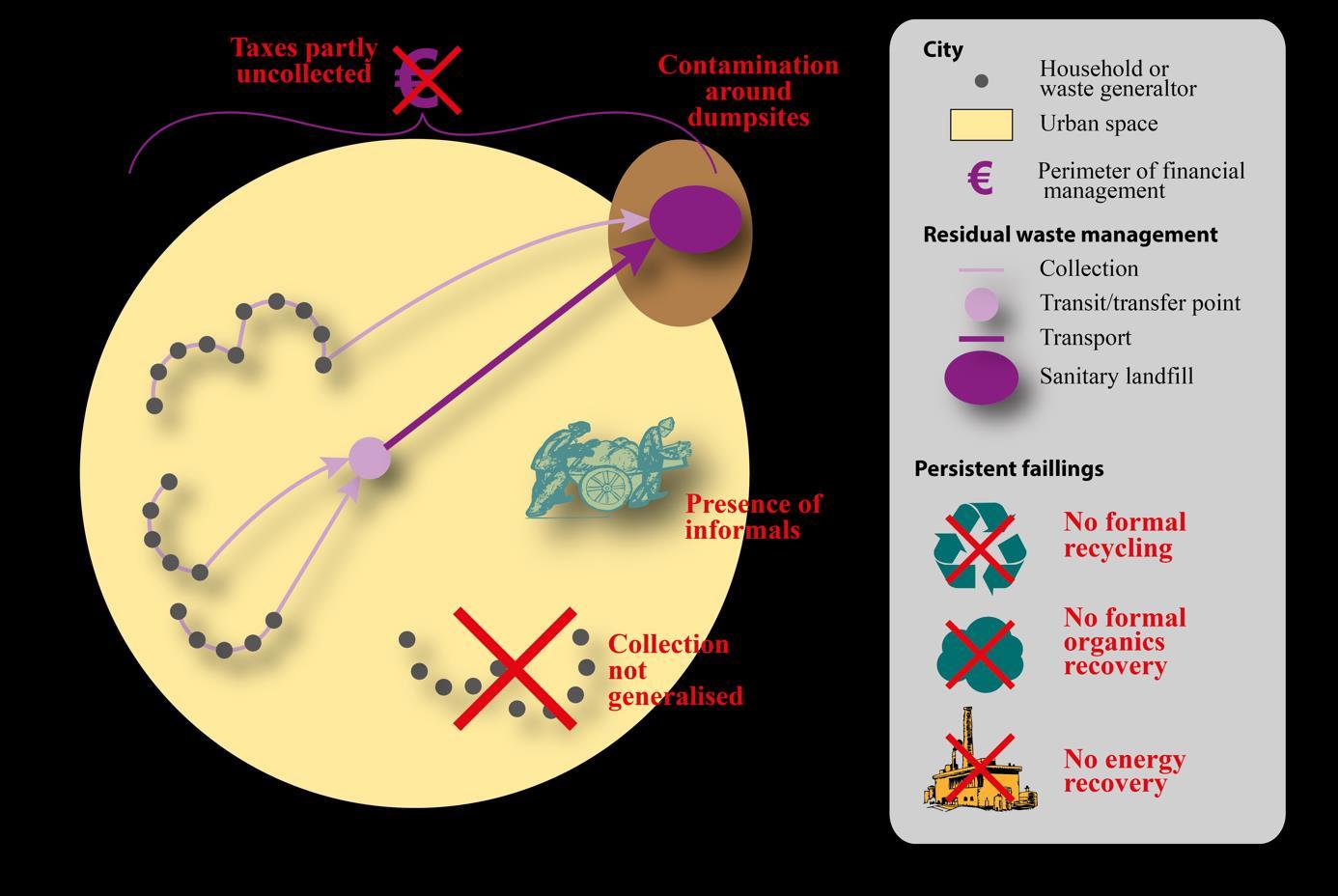

A model not fully operational in the global South cities

Although this model long served as the international benchmark to be universally replicated, today various limitations to its application have been observed. - The impossibility of implementing citywide door-to-door collection creates a socio-spatial segregation of service access. While city-centre and affluent districts are able to benefit from this service, this is not the case for the poorest peri-urban settlements (no accessibility, inability to pay, illegal housing, etc.). - The absence of generalised waste recovery and recycling is one of the features of this model. Since the foremost objective is health, it precludes any possibility of recycling or composting in order to prevent waste stocks from being dispersed to inadequately controlled sinks. It is better to landfill all waste rather than allow individuals to handle it given that it is a source of risk. - The persistent presence of informal actors. Despite a relentless struggle against informals, it seems impossible to dislodge them, not only because they compensate for the shortcomings of the municipal service, but also because of the influx of vulnerable populations seeking a source of income. - The fourth limit is the impossibility of collecting the taxes intended to finance the service. Unable to pay or dissatisfied with the poor service quality, users massively opt out of paying, which exacerbates the dysfunctioning of an already under-financed service. The local authorities’ general budget or the state budget then has to make up the shortfall.

- Lastly, this model is greatly limited by the very serious problems of controlling landfill sites and thus curbing pollution in the vicinity. Only the richest cities are on the way to achieving this (Lima, Bogotá, Surabaya), and only partially.

Figure 26.

Dysfunctions of the centralised, unified and linear model

The second existing model has advantages and disadvantages that are diametrically opposed to the previous model.

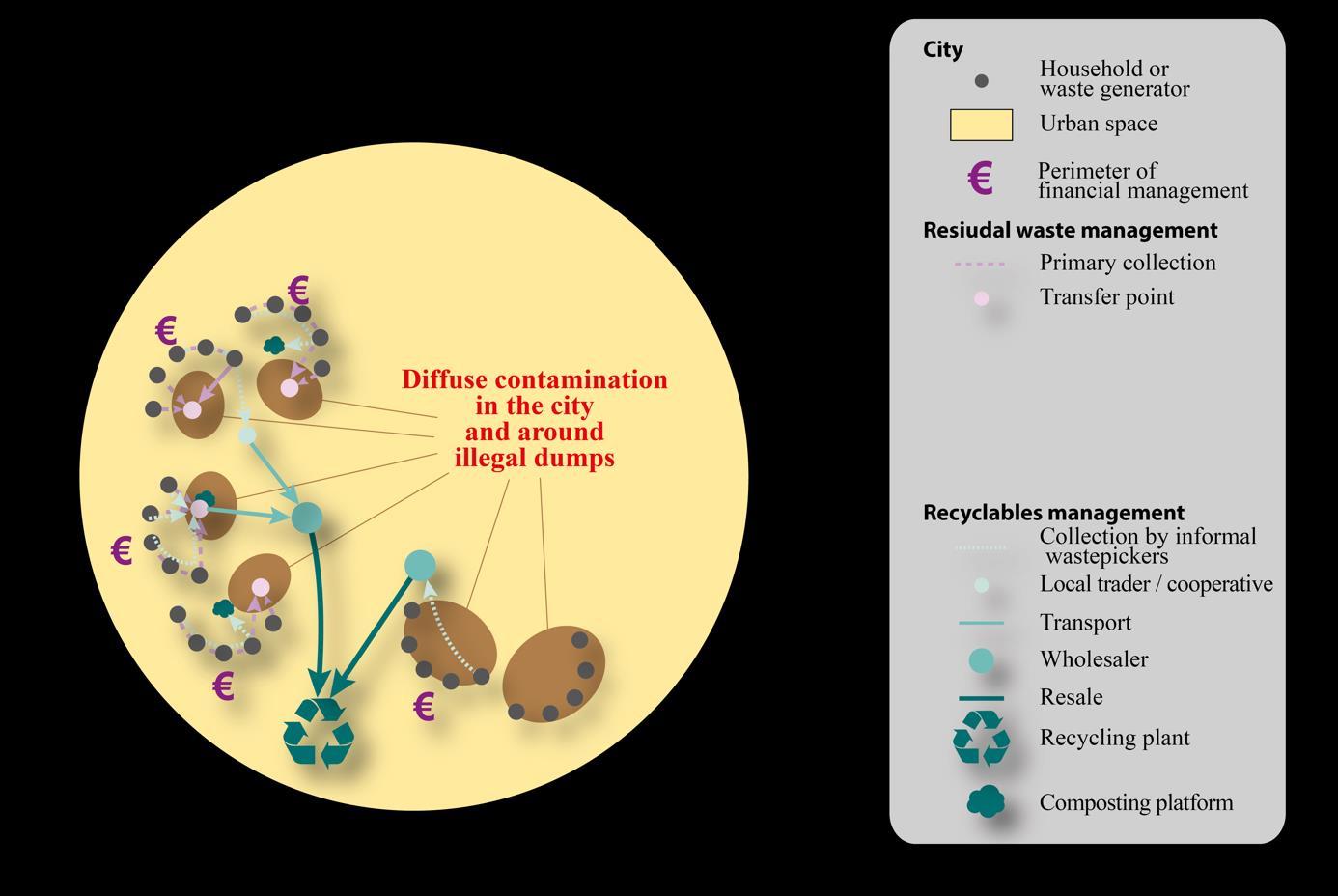

A model linked to the deficiencies of municipal management

As it stands, the centralised model seems difficult to apply to global South cities since their social and economic structure does not fit the requirements. In the absence of a centralised model, another model emerges by default, spontaneously, in order to ensure a minimal waste removal service for residents. This involves primary collection by the residents themselves (when they deposit their rubbish at the end of the street) or by informal primary collectors paid directly by the residents. The primary collectors then dump the rubbish on the roadside, at spontaneous transfer points or in the natural environment (ravines, rivers, fields, ditches, etc.). Although unorganised, these practices can be qualified as “self-management” since they are a form of spontaneous management that differs from a situation in which there is no waste management at all.

This model is diversified since each neighbourhood sets up its own method of primary collection in line with its specific financial, technical, territorial, social and cultural characteristics. The diversity of management methods stems from the fact that informal actors work extensively on recovering recyclable waste. Residents also sometimes source-separate in order to save themselves the cost of primary collection and make a little money by selling their waste to informal recovery actors. These diverse options give rise to an intense activity involving the re-use of objects, out of necessity, which also prevents the generation of large amounts of waste. However, the local impacts on health are often negative. Finally, the model is often insalubrious as it produces a diffuse contamination of the territory in each locality where waste remains uncollected: in homes and all the illegal dumpsites along the roadside and waterways.

Figure 27. The informal, diversified and insalubrious waste management model

In practice: an informal semi-integrated model

This model is actually more complex given that it rarely exists alone. It is generally found alongside the centralised, unified and linear model. The points where the waste from primary collection is dumped are habitually located on main roads. The municipality then attempts to provide a more or less regular service to collect this loose roadside waste and transport it to disposal sites that are more or less controlled. The informal model is only implemented as the sole solution in the poorest neighbourhoods of the reference cities. In these localities, contamination of the natural environment is very high and the first to be adversely affected by this model are the residents themselves.

Some advantages not to be disregarded

In all the cities, this informal model is described as a situation to be avoided and as the reason why it is urgent to intervene in waste management. Although it is crucial to change the model, it is also important not to reject all of its characteristics. In global North cities, which operated on a similar model until World War II, mistakes were made that later had to be rectified at great cost. This model does indeed offer some advantages: - First of all, it allows for a high level of waste recycling, whereas the centralised model includes no waste recovery activities. Informal actors constitute a workforce that has considerable know-how on recognising the different types of material (even if their usual freedom of action is difficult to reconcile with fixed employment in a sorting centre). It will take Europe years to re-train waste workers in modern sorting centres now that this practice has disappeared. - Residents also continue their habit of source-sorting at home. They do this out of necessity, but do not yet feel disgust at materials that can be sold on, composted in their backyard or fed to animals. - The practice of re-use is also widespread. When the centralised model arrives in a neighbourhood, residents enjoy the luxury of being able to discard objects more easily (linked to mass consumption). Yet, today European policies are trying to encourage re-use in order to reduce waste. - Lastly, the daily need to remove waste out of a neighbourhood (primary collection or direct action by residents) forces the inhabitants to collaborate and organise a minimal degree of community action. The cleanliness of a neighbourhood thus necessarily implies a high level of sociability. This is shown by the examples of Antananarivo and Surabaya.

3. A participatory, composite and circular model

The third, emerging, model deploys some of the innovations highlighted throughout this report. It attempts to maintain the objectives of public health and service improvements found in the centralised model, while also recognising the aspects that are difficult or impossible to implement locally. It thus seeks to rely on the advantages of the informal model to build a hybrid solution (or “mixed modernities”, cf. Chapter 1) that is more adapted to global South countries. In fact, each territory has to invent its own model – one which is not systematically or globally replicable.

A model under construction based on empirical innovations

This model thus encompasses all of the innovations identified as levers for developing waste valorisation and management. And as such, it has hybrid characteristics: - It is participatory in that the population takes an active part in managing waste, with a collective objective and not out of necessity. Residents sort some of their waste at home and/or in community sorting centres, remove the waste themselves to outside the neighbourhood, or collectively manage a primary collection service by delegating these tasks to primary collectors or wastepickers. This is the case of the Indonesian waste banks, the Malagasy RF2 system and Peru’s formalised wastepickers. They can also participate in exchanges with the public actors. Coordinated at metropolitan level, these exchanges may take place with the

neighbourhood’s municipality or district authorities. This means that there is also a (partly) decentralised aspect. - It is composite insofar as waste management no longer involves one single model common to all city residents or all types of waste, but is instead tailored to micro-local contexts, as well as to the types of material discarded. This diversity means that a primary or secondary collection service can be proposed to suit a neighbourhood’s means and practices. It implies trusting a multitude of stakeholders to collect waste, sort it and recover it (e.g., a private firm for RHW collection, a formalised wastepicker organisation for recyclables and a community for compostables). - It is circular because, contrary to the first model, the stated objective is clearly to move towards a high rate of waste recovery. The local authorities that implement the innovations described above always do so in order to recover the maximum quantity of waste, taking account not only environmental, but also social and economic issues. This circularity could be broadened to a model that aims to avoid increasing waste generation by maintaining and encouraging relevant practices (re-use, returnable packaging, repair, etc., which are widely developed in the informal model).

Figure 28. The participatory, composite and circular waste management model

Multi-scale complementarity and evolution over time

Like the previous models, what is observed in reality is a blending of the participatory model and the other models. Sorting and recovery systems complement a municipal service that, in

all cases, lacks the capacities to meet the requirements for generalised collection and recovery. This complementarity emerges at multiple levels. While there is considerable coordination at metropolitan-scale, the neighbourhood scale always seems to be pivotal. It is the long-standing sociability in Surabaya that enables the roll-out of sorting and composting innovations. It is neighbourhood solidarity in Antananarivo and Delhi that helps primary collection to function a minima. It is the relationship of trust between the residents and primary collectors (Lomé) or wastepickers (Lima and Bogotá) that facilitates local intervention. Moreover, this local sociability is expressed in different ways within the neighbourhoods in the same city, whether they are central or peri-urban, rich or poor, horizontal or vertical. The role of metropolitan coordination is to ensure that this multi-faceted dimension does not ultimately lock poor neighbourhoods into below-standard solutions and thus increase socio-spatial segregation. An important question here is the timeline for moving from one model to another. Are centralised and informal models set to shift to the participatory model or coexist within the same city? Is the participatory model destined to evolve towards a more integrated system with greater control by public actors as is the case in global North countries? Or on the contrary, are global North countries – where an increasingly composite aspect is visible (multiplication of sub-sectors and actors) – going to slide towards a more participatory and technically decentralised model, notably due to budget constraints? This model also radically challenges the logics implemented in the global North countries by proposing “post-network” and “post-policy” solutions (Coutard, Rutherford & Florentin, 2014). This no longer signifies offering a unified and homogenous service to all of a city’s inhabitants, but shifting the limit of the public service in order to provide waste management adapted to local constraints.

4. Applying the models to the reference cities

The three models (choremes) presented above are clearly theoretical. In practice, they are present to varying degrees in all six reference cities: - While no city as a whole matches the “centralised, unified and linear” model, the district of Surco (Lima) – which takes what happens in global North cities as its example –has the closest fit. We could also add some districts in Delhi. - The second “informal, diversified and insalubrious” model mainly concerns the cities’ poorest neighbourhoods. It is in Antananarivo that it seems most widespread because the municipality has by far the lowest level of financial resources to manage its waste. - Finally, the “participatory, composite and circular” model is emerging in several cities, particularly Bogotá, Lima and Lomé. It is in Surabaya that the broadest diversity of technical and organisational innovations are proposed.