THE WHY BEHIND EDUCATION REFORMS

Cognitive-affective learning

Equity at the heart of every school

Rural principalship

Cognitive-affective learning

Equity at the heart of every school

Rural principalship

The great principals are remembered for what they leave behind.

A Shade Systems canopy isn’t just shelter.

it’s a legacy of care and protection.

Request your obligation-free proposal now

EDITOr

Liz Hawes Executive Officer

PO Box 25380 Wellington 6146 Ph: 04 471 2338

Email: Liz.Hawes@nzpf.ac.nz

mAGAZINE prOOF-rEADEr

Helen Kinsey-Wightman

EDITOrIAL bOArD

Leanne Otene, NZPF President Geoff Lovegrove, Retired Principal, Feilding

Liz Hawes, Editor

ADVErTISING

For all advertising enquiries contact: Cervin Ltd

PO Box 68450, Victoria St West, Auckland 1142 Ph: 09 360 8700 or Fax: 09 360 8701

NOTE

The articles in New Zealand Principal do not necessarily reflect the policy of the New Zealand Principals’ Federation. Readers are welcome to use or reprint material if proper acknowledgement is made.

SUbSCrIpTION

Distributed free to all schools in New Zealand. For individual subscribers, send $40 per year to:

New Zealand Principals’ Federation National Office, PO Box 25380, Wellington 6146

New Zealand Principal is published by Cervin Ltd on behalf of the New Zealand Principals’ Federation and is issued four times annually. For all enquiries regarding editorial contributions, please contact the editor.

Emalene

Lee

Dr

Pat

Professor

Helen

ISSN 0112-403X (Print) ISSN 1179-4372 (Online)

PHOTOS FOR THE MAGAZINE:

If you have any photos showing ‘New Zealand Schools at Work’, particularly any good shots of pupils, teachers or leadership staff, they would be welcome.

The appropriate permission is required before we can print any photos.

TECHNICAL DETAILS:

Good-quality original photos can be scanned, and digital photos must be of sufficient resolution for high-quality publishing. (Images should be at least 120 mm (wide) at 300 dpi). Please contact Cervin Ltd for further details. Phone: 09 360 8700 or email: education@cervin.co.nz

Liz Hawes EDITOR

THERE’S A STRONG THEME running through this issue of NZ Principal magazine. It is that politicians create a crisis of educational failure to justify introducing a standardised curriculum with rigorous testing. That is what Education Minister Hon Erica Stanford is engaged in right now. Stanford is motivated to see New Zealand in the top ten of the OECD countries for Literacy and Maths. Both she and the Minister of Finance, Hon Nicola Willis see improved education results as the most important factor in improving future productivity in New Zealand. They are not the first Government Ministers to pair economic prosperity with educational outcomes.

It’s not that high numbers of New Zealand’s young people are failing. They are mostly doing quite well – although there is a growing group who are not doing so well. They sit at the bottom where Māori and Pacific Island ākonga are over-represented. We quite rightly should be concerned about these students. They are there because of inequities in the system, lack of high quality, timely learning support, and socioeconomic factors such as food, clothing and housing insecurity. These factors create transience and non-attendance. These students are also the young people who live in poverty, where mental health and related issues such as drug addiction and violence also thrive. They are our most vulnerable young people.

But rather than focus on the needs of these young people at the bottom, politicians always go for the standardised curriculum for all. If we think this behaviour is peculiar to the current coalition government – it is not. We had all of this from the 2008 Minister of Education Hon Hekia Parata and her national standards and many times before that, including in 1949 from the Minister of Education, Hon R.M. Algie. In 1965 the Minister of Education, Hon Arthur Kinsella, requested that NZCER develop standardised assessments for core subjects, and in1978 from the Hon Prime Minister Robert Muldoon, who similarly wanted to lift achievement. Whilst in opposition, Hon Lockwood Smith advocated a ‘back-to-basics’ approach with achievement benchmarks for each year level in English, Mathematics and Science, and on the national party’s return to government in 1990, the Minister of Education Hon Nick Smith, advanced the reforms, but paused them in 1996 due to feedback from schools regarding teacher workload and the scale and pace of change. In 2000 it was Education Minister Hon Trevor Mallard calling for high standards, weekly tests and regular reporting to parents –see Kim Hailwood’s, ‘Understanding the why behind education reforms – Contemporary reforms – mandating a one-size-fits-all to curriculum’ (p. 5) for a comprehensive account of what sits behind such educational reform.

Right now, Aotearoa is having a ‘PISA Shock’ moment. According to Kim Hailwood, many countries before us have

experienced similar ‘PISA shocks’ which almost always lead to curriculum reform. Tellingly, most OECD member countries are clustered in a central cohort so even minor variations can result in large shifts in rankings – a PISA shock – leading us to think that our ākonga are slipping drastically when they have hardly dropped at all. Add to this the sampling errors associated with PISA assessments, and rankings start to look a great deal less reliable, especially if countries are using OECD assessments to form their education policies.

Professor John O’Neill also addresses standardisation in his column (p. 31), arguing that standardisation will not achieve equity, which Minister Stanford notes is another of her goals. He too talks about how discussions dominated by standards are almost always economic, but we cannot reduce economic inequities by forcing the same curriculum and standards on all children.

He opposes the idea that our vulnerable ākonga will be saved by the science of learning and its accompanying structured literacy and mathematics. O’Neill says that if these young people are to climb the learning ladder at all, they are far more likely to do so through those random teachable moments. Further, he notes fostering curiosity about the natural and social worlds and developing critical thinking and life ethics are equally as critical as literacy and mathematics.

President Leanne Otene adds to the debate in her own column (p. 3) by asking ‘What is the purpose of Education?’ She adopts a definition of student success which extends beyond measuring reading, writing and mathematics to include, in equal measure, the broader competencies of developing well-rounded individuals who can collaborate, communicate effectively, show empathy and think critically. She adds that in Aotearoa New Zealand this also means fostering in our tamariki a strong sense of identity, culture and language while embracing te Tiriti o Waitangi.

Although not alone in a global sense, we have a long history of linking educational achievement with economic success, which makes OECD assessment programmes an attractive option for governments from both sides of our political divide. The OECD’s PISA TIMMS and PIRLS tests have become an obsession we cannot shake, and as each new set of rankings are rolled out, unless we have (almost accidentally) moved up the ladder, our government of the day will have another new standardised approach to curriculum, ready to roll. It should be no surprise that we had ‘Back to Basics’ with Lockwood Smith in the late 1980s and ‘Doing the Basics Brilliantly’ nearly 40 years later. They’re the same thing with a slightly different approach. As Lily Tomlin once said, ‘Maybe if people (or politicians) started to listen (to practitioners), history would stop repeating itself.’

Leanne Otene NATIONAL PRESIDENT, NEW ZEALAND PRINCIPALS’ FEDERATION

I RECENTLY HAD THE privilege of attending a UNESCO Principals’ Seminar in Shanghai. Much of our mahi was about ‘defining student success’. Repeatedly, we heard that success is not defined by reading, writing and mathematics assessment data, and nor does such data define the quality of a teacher.

Andreas Schleicher, Director for Education and Skills at the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), said that education must go beyond measuring academic success and place equal value on developing broader competencies. Real and authentic education, we learned, goes beyond literacy and numeracy; it’s about nurturing well-rounded individuals who can collaborate, think critically, communicate effectively, and show empathy. In the context of Aotearoa New Zealand, it also means fostering a strong sense of identity, culture, and language, while embracing the articles of Te Tiriti o Waitangi. This includes recognising and valuing the rights, knowledge, and perspectives of Māori as tangata whenua, and ensuring our learners understand and respect the cultural foundations that make up our society. By weaving these values into education, we prepare students not only for academic success but also for contributing meaningfully to a diverse, inclusive, and respectful nation. These skills form the bedrock of a healthy, functioning society, and are just as important as academic achievement.

significant shifts in the New Zealand Curriculum: Structured Literacy and Structured Maths. Curriculum changes can potentially lift learning outcomes for individual students, but good intentions alone won’t guarantee success. As I’ve observed these changes roll out, I see a real risk of implementation loss.

NZCER’s 2024 primary principals’ survey revealed 71 per cent believe the pace of curriculum change is too fast. That’s no small warning. From Southland to Northland we’re hearing the same message: ‘We want to incorporate the new curriculum approaches into our schools, but we don’t have the time, available PLD or support to ensure success.’ Providing teachers with free workbooks and imported programs is not a substitute.

EDUCATION must go beyond measuring academic success and place EQUAL VALUE on developing BROADER COMPETENCIES

Implementation loss shows up in multiple ways. Teachers lose confidence to adapt. Professional learning becomes a tick-box. Leaders are not offering deliberate guidance, because they have been left out of the PLD loop. Principals are being asked to manage multiple shifts without the time or structural support to lead them effectively. Many are working late into the night, piecing together plans while managing compliance, staffing, and community expectations. That’s not sustainable.

I believe this is the lens through which we should ask more meaningful questions: How are we defining success for our tamariki in Aotearoa New Zealand? Are our teachers confident and inspired? Are our students engaged, curious, and supported in their social and emotional growth alongside their academic growth? Are schools properly resourced with the tools and given the time to be successful? Until we begin to define success in ways that encompass the full purpose of education, we risk reducing it to some arbitrary number and losing sight of the individuals at its core.

The other topic on the UNESCO agenda was ‘Implementation Loss’. This term relates to change management and refers to the gradual erosion of policy potential caused by rushed rollouts, inconsistent support, and overwhelming system demands. Implementation loss is a very real challenge, particularly for large-scale changes. It occurs when the effectiveness and impact of a policy or initiative diminishes as it moves from theory to practice, often due to the way it is executed.

Here in Aotearoa New Zealand, we are implementing two

Most concerning of all is that our vulnerable students – our Tier 3 learners – are unsupported. These are the tamariki already at risk of disengagement and underachievement. These are the tamariki who make up our long and thickening tail of underachievement, creating the unacceptable inequity gap between our highest and lowest achievers. Ignoring Tier 3 support needs will widen the equity gap, not close it.

NZPF consistently states that while 15–20 per cent of students have additional learning needs, a tiny fraction of schools feel sufficiently resourced to meet them. The money promised in the budget to support structured literacy and maths is welcome but much more is needed to address our high levels of neurodiversity. Teachers need time to practice curriculum changes, reflect, get feedback, and refine, but the workload is crushing. Principals say that while their teams are eager, they simply don’t have the hours in a week to address both Structured Literacy and Structured Maths at once. The risk is both subjects will be compromised. The Minister’s message to ‘just get started’ doesn’t reflect the reality – especially when community expectations have been raised and reinforced by Ministry officials.

continued on p.4

We still have choices. It is not too late to slow down. The system is not beyond repair and slowing down might be the very thing that saves it. We could take a staged approach – consolidate Structured Literacy in Years 0–3 before expanding further, while delaying Structured Maths until literacy is fully embedded. This isn’t giving up; it’s doing things well, in the right order, and with respect for the professionals charged with delivering it.

We need to redesign our support model. Deep, embedded PLD with coaching and mentoring, release time for collaboration, and structured communities of practice are what schools are asking for. They don’t need more urgency – they need more time and trust.

None of this is a call to abandon change. It is a call to do it better. Because if we continue at the current pace, we risk losing the very people we rely on to make this change work. We’ll see burnout instead of buy-in, and compliance instead of creativity.

Implementation loss is not inevitable. But it is real. We are at the tipping point right now. We can keep pushing forward and risk losing both momentum and morale – or we can pause, listen, and lead with wisdom. Slowing down now might just be the smartest, most courageous move we can make.

Our clients choose us for many reasons – but a few that come up regularly are;

1) Our people – we work with you and come to your site. We partner you with a school accounting professional.

2) Our flexibility – any software you choose – xero, MYOB or our free software – and our reports are school specific – not some business model that is not fit for purpose.

3) Reduce risk of fraud and misappropriation (and time spent at the school) by using our creditor payment service.

4) Peace of mind – everything is done correctly and on time – so you have more time to spend focusing on Education. Come and find out why over 800 of your colleagues use Education Services Limited – and have real peace of mind.

Contemporary reforms – mandating a one-size-fits-all to curriculum

Kim Hailwood NZPF RESEARCHER

If we can implement structured literacy being taught in every school in the next couple of years, I will retire a very happy politician because that is monumental. We will be the first country in the world, as far as I’m aware, that has done that. And it is going to be game-changing.

Hon. Erica Stanford, Minister of Education (NZ Herald, 3 May 2024)

IN AN ARTICLE PUBLISHED in The Australian newspaper on 24April 2024, the Executive Director of The New Zealand Initiative, a pro-free-market think tank, remarked, ‘In New Zealand, one of the most exciting education reforms in the world is quietly getting underway. Erica Stanford, the country’s new Education Minister, is on a mission to overhaul the education system from top to bottom – and she is leaving no stone unturned’.

Formed in November 2023, the current National-led government asserts that education is pivotal in facilitating equitable opportunities for all citizens. The Minister of Finance, Nicola Willis, reinforced this perspective during the 2024 Budget announcement, declaring, ‘Education is the great liberator, the great equaliser, and the most enduring gift we can bestow on our children’. In her Budget 2025 address, she further articulated a direct connection between educational outcomes and national economic performance, affirming, ‘To my mind, improving the results we get from our education system is the single most important thing we can do to improve the future productivity of New Zealand’.

Minister Stanford states that the prevailing decentralised schooling model places an undue burden on individual schools. She observes that the highly flexible and devolved system, where ‘school communities make varied decisions about how students are taught and assessed’, often leaves educators lacking the specialised expertise necessary for curriculum development, assessment design, and effective pedagogy. The Minister main-

tains that ‘Until we fix our curriculum, our pedagogy and assessment, we will not lift our achievement and we will not see the closing of the equity gap’1.

The Government’s restructuring of the national education system is underpinned by a core philosophy comprising three interrelated pillars: ambition, achievement, and outcomes. This philosophical framework has been operationalised through the establishment of six key educational priorities, outlined below. These priorities constitute the overarching structure guiding policy development, resource allocation, and teaching methods within the system.

In April 2024, the Minister of Education submitted a paper to the Cabinet Social Outcomes Committee, detailing her educational priorities for the forthcoming three years. This document references the work of American educator and academic Professor E. D. Hirsch Jr., who attributes ‘the systematic failure to teach all children the knowledge they need in order to understand what the next grade has to offer’ as the chief cause of ‘avoidable injustice in our schools.’2

E. D. Hirsch, through his influential works Cultural literacy: What every American needs to know and Why knowledge matters: Rescuing our children from failed educational theories, presents two core arguments. First, Hirsch contends that the acquisition of a shared body of societal knowledge, referred to as ‘communal knowledge’, is essential for improving the life opportunities of individuals. Recognising that not all learners have access to this foundational knowledge within their home environments, he stresses the importance of teaching it within schools. Second, Hirsch advocates for a highly structured and sequential educational approach, wherein students systematically develop their knowledge base over time. This, he argues, requires a return to fundamental educational principles, implemented through a rigorous core curriculum.

Hirsch’s concept of a knowledge-rich curriculum has attracted

1 Clearer curriculm Establishing a knowledge-rich curriculum grounded in the science of learning.

2 Better approach to literacy and numeracy Implementing evidence-based instruction in early literacy and mathematics.

3 Smarter assessment and reporting Implementing consistent modes of monitoring student progress and achievement.

4 Improved teacher training Developing the workforce of the future, including leadership development pathways

5 Stronger learning support Targeting effective learning support interventions for students with additional needs.

6 Greater use of data Using data and evidence to drive consistent improvement in achievement.

continued on p.6

considerable critique, particularly with respect to its potential to disadvantage students from diverse backgrounds and to constrain creativity. A central concern relates to the apparent Eurocentric bias of Hirsch’s list of ‘core knowledge’, despite claims of its universal applicability. This observation raises important questions regarding the criteria by which ‘essential’ knowledge is determined and the cultural perspectives that are therefore prioritised, presenting the risk of marginalising or excluding alternative cultural viewpoints and knowledge systems. Additionally, some academics suggest that Hirsch’s framework does not sufficiently acknowledge the inherent complexities of literacy and learning, nor does it adequately consider the profound social and cultural factors that shape an individual’s engagement with knowledge.

The Ministerial Advisory Group (MAG) for Education, chaired by Dr Michael Johnston (a cognitive psychologist and Senior Fellow for Education at The New Zealand Initiative), commenced its work by developing recommendations concerning curriculum design and teaching approaches in early-years literacy and mathematics. With the explicit support of the Minister of Education, MAG’s remit was subsequently expanded to encompass the integration of ‘science of learning’ principles, ‘structured instruction’, and a ‘knowledge-rich curriculum’ across all primary and secondary education levels.

Dr Johnston, drawing upon established principles from the science of learning, presented a core educational doctrine that shaped many of MAG’s recommendations. This approach stresses the critical need to methodically embed essential knowledge into students’ long-term memory before introducing more advanced ideas. Dr Johnston further emphasised the need for a curriculum that is carefully sequenced, content-rich, and selective in coverage. As he observed, ‘teachers cannot teach everything, the curriculum must therefore be selective. It must ensure that truly foundational knowledge is emphasised.’ 3

The Minister of Education advocates for a consistent, onesize-fits-all approach to education. She asserts that a thorough understanding of the science of learning, particularly the cognitive processes involved in knowledge acquisition and reading, is paramount for achieving educational equity. The Minister maintains that, as ‘the human brain learns to read the same’, regardless of an individual’s background, leveraging the science of learning is the most crucial action for advancing equitable outcomes.4

Minister Stanford stresses that, while fostering cultural responsiveness and ensuring a welcoming school environment are important for promoting student inclusion, these measures are insufficient if the ‘brain science part’ of learning is not

2025 – Schools are:

addressed. She maintains that, without a firm grounding in the science of how students acquire knowledge, particularly reading skills, students are unlikely to achieve essential competencies, regardless of how inclusive the school environment may be.

Looking back briefly

Many would gladly see the so-called ‘three R’s’ restored to their rightful place in our curriculum. And, on this point, I must say that I am wholeheartedly with them.

(R. M. Algie, National Minister of Education, 1949)

We have given insufficient attention in recent times to basics in education, and that neglect shows up through the secondary system on to tertiary education and on into adult life, wherever that may lead.

(Prime Minister Robert Muldoon, 1978)

This Government is going to make a difference. We want high standards, not low standards. We want tests that occur week by week and are reported to parents regularly, rather than the four-year approaches taken by the previous government.

(Labour Education Minister Trevor Mallard, 2000)

Amid widespread public unease over a perceived decline in educational standards following World War II, the Minister of Education, Philip Skoglund, convened an independent Commission on Education. This commission was tasked with conducting a thorough review of the national education system. The Commission, established in February 1960 under the chairmanship of Sir George Currie and comprising 11 members, undertook a comprehensive investigation into the contentious issue of ‘modern educational methods’. The Commissioners concluded that there was no longer a place within New Zealand primary schools for educators who rejected the ‘cardinal ideas of variation in ability and attainment’ and who ‘narrowed all achievements to success in the three R’s’ by intentionally preventing students from advancing through the education system ‘until they had reached each year some fixed level or standard of attainment’.5

In response to persistent concerns regarding declining standards in primary education, the Commissioners recommended that the New Zealand Council for Educational Research (NZCER) be tasked with the development and implementation of national standardised assessments. These assessments, referred to as ‘checkpoints of attainment’, were to be administered at five-year intervals in core subjects, thereby allowing for robust and valid

Required to implement structured approaches to teaching reading and writing, pānui and tuhituhi in Years 0–3.

Required to use the updated English and Te Reo Rangatira (Years 0–6), and the updated mathematics and statistics and Pāngarau (Years 0–8) curriculum content.

Encouraged to adjust their assessment, aromatawai, and reporting to reflect how students and ākonga are progressing against the new Years 0 to 6 English and Te Reo Rangatira and Years 0 to 8 maths and Pāngarau curricula.

Required to report to whānau | families about how ākonga | students are progressing against the new Years 0 to 6 English and Te Reo Rangatira, and Years 0 to 8 maths and Pāngarau curricula.

Encouraged to implement 20- and 40-week phonics checks or Hihira Weteoro for Year 1 students and share phonics data with the Ministry of Education.

comparisons of student achievement at specific points in the primary curriculum (namely, Standards 1, 4, and Form 2). It was emphasised that these ‘checkpoints’ should serve as a supplement to, rather than a replacement for, teacher assessments, given that teachers possess unique professional insight into the factors influencing student performance and ability.

Following the publication of the Currie Commission’s report in 1962, the Minister of Education, Arthur Kinsella, formally requested in 1965 that NZCER develop standardised group assessments to measure attainment in core school subjects. These assessments were to align with New Zealand syllabuses and be applicable across all levels of education. Four years later, NZCER released the initial series of standardised tests, which were subsequently distributed to all primary schools nationwide.

In 1978, the Department of Education published a report entitled Educational Standards in State Schools, which provided a comprehensive evaluation of educational standards within state-funded schools across the country. The report, formally submitted to the Minister of Education, sought to address widespread anxiety about an apparent decline in educational standards, particularly in relation to basic literacy and numeracy skills. Prompted by apprehensions about the education system’s capacity to adequately prepare students for further training and employment, the report underscored the necessity for a renewed focus on the teaching of fundamental skills essential for success in both higher education and the workforce.

Throughout the 1980s, significant administrative reforms were implemented within the schooling system as a principal strategy for improvement. Central to this approach were the recommendations of the Picot Report and the subsequent

Tomorrow’s Schools initiative. Concurrently, an ‘outcomes-based’ curriculum emerged, outlining national learning outcomes for students while affording schools greater autonomy in determining instructional approaches. However, the initial draft of this curriculum was set aside due to extensive educational and governmental restructuring that occurred in 1989 and 1990.

While in opposition, the National Party sought to address the Tomorrow’s Schools initiative by placing particular emphasis on curriculum reform. Dr Lockwood Smith, the Party’s spokesperson for education, advocated for a ‘back-to-basics’ approach, recommending the establishment of achievement benchmarks for students at each year level in what he identified as the three ‘core competencies’: English, mathematics, and science6. After the National Party’s return to government in October 1990, Minister Smith implemented a series of substantive reforms, most notably initiating the development of a national curriculum framework.

In May 1991, a draft document encompassing seven key learning areas was formally presented by the Minister at a curriculum conference convened by the Post-Primary Teachers’ Association. Due to ongoing concerns and feedback from schools regarding the implementation of the revised curriculum, the scheduled timeline for completing these reforms was paused in June 1996. This decision was taken to specifically address issues related to teacher workload, as well as the scale and pace of systemic change within schools. Over the following eight years, a period notably longer than the originally proposed two-year timeframe, educators progressively received all seven core curriculum documents for Years 1 to 13.

weave + tui

Harnessing wool’s natural strengths for better learning spaces.

Sourced from New Zealand farms, our wool carpet tiles support local manufacturing and rural communities. Wool is a renewable, natural fibre with deep roots in Aotearoa’s heritage making it a smart and meaningful choice for modern spaces.

Wool fibres have built-in stain resistance, ideal for high-traffic commercial environments. They help maintain a cleaner, more professional look over time, reducing the need for harsh chemical treatments.

Tiles can be individually replaced if damaged, unlike broadloom carpet. This saves time and money on repairs while keeping your floors looking fresh and consistent across large areas.

Wool absorbs sound naturally, reducing noise and echo in busy environments. This supports focus, creativity, and well-being, key for productive workplaces and learning spaces.

Declare ® Red List Free certification means our wool tiles are free from harmful VOCs, supporting healthier air and safer, more breathable interiors.

We’re introducing vibrant, uplifting colours designed for education settings and dynamic workplaces. These new shades bring personality and energy to commercial interiors, perfect for spaces that inspire.

For more information and free samples, contact: varo.pasupati@godfreyhirst.co.nz or visit ghcommercial.com + fern + feather

Upon assuming office in 2008, following nine years in opposition, the National Government introduced a 10-point education plan. Prime Minister John Key described this initiative, focused on improving children’s literacy and numeracy, as a ‘crusade’. Central to this policy was the mandatory, systematic assessment of all primary and intermediate students against established national standards in literacy and numeracy. The Government’s stated objective was to provide parents with clear, accessible (‘plain English’) information about their child’s academic performance. This approach was designed to empower parents by giving them a stronger voice and more choice in educational matters concerning their children. The overarching goal was to guarantee equitable opportunities for success to every child and to enable meaningful, consistent comparisons of achievement among schools.

Following the re-election of the National Government in 2011, which was widely interpreted as an endorsement of its economic and social policies, including those related to education, a more assertive market-liberal agenda was adopted. In 2012, the Government mandated that all primary and intermediate schools report student achievement data against established national standards to the Ministry of Education. This directive required schools to submit information detailing the proportions of students assessed by teachers as performing ‘above’ or ‘below’ the defined benchmarks.

A significant controversy emerged when a senior political reporter from a major newspaper group submitted an Official Information Act request to all schools, seeking their respective data in advance of the Ministry of Education’s scheduled official release later that year. Subsequently, Fairfax Media launched an interactive ‘School Report’ feature on its website, presenting aggregated national standards data alongside relevant contextual information for all participating schools. The lead political correspondent issued a formal statement explaining the rationale for publishing this information, while acknowledging the data’s incomplete and potentially problematic nature.

PISA results show an urgent need to teach the basics.

A structured approach to learning is the way to go.

Minister of Education Media Release (5 December 2023)

The most recent Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) report, released on 5 December 2023, reveals a continued decline in academic performance. Average scores in mathematics, reading, and science have decreased in comparison to previous years, thereby extending a downward trend that has been evident since 2009. In particular, mathematics scores fell by 15 points, while scores in reading and science each declined by approximately four to five points. Despite these reductions, Aotearoa New Zealand’s results remain above the OECD average in all three subject areas.

Responding to the 2022 PISA results, Minister Erica Stanford, in the Government’s official media release entitled ‘PISA results show urgent need to teach the basics’, described the declines in reading, writing, and mathematics as both disappointing and unsurprising, remarking ‘we have been using incorrect methods for the past 30 years’7. The Minister further emphasised that the PISA results underscored persistent deficiencies in the schooling system’s ability to deliver satisfactory learning outcomes for students.

The OECD’s PISA initiative systematically evaluates the proficiency of 15-year-old students in reading, mathematics, and science, as well as their readiness for adult life and future employment. The primary objective is to assess the ability of students to apply their knowledge and to draw connections between educational outcomes and national schooling systems. During the 2022 assessment cycle, PISA evaluated approximately 690,000 students across 81 OECD member and partner economies, including 37 OECD countries. Participation from Aotearoa New Zealand comprised nearly 4,700 students, drawn from 169 English-medium schools during Term 3, 2022.

During the 2022 assessment cycle, 18 countries and economies achieved results above the OECD average across mathematics, reading, and science. Mathematics proficiency among OECD nations experienced an unprecedented decline of 15 points from 2018 to 2022, representing the largest decrease on record. Reading scores similarly declined by 10 points, a reduction twice as substantial as any previously observed. In contrast, science performance remained relatively stable over the same period. Analysis over the preceding decade indicates consistent downward trends in both reading and science, whereas mathematics achievement had remained largely stable from 2003 until the onset of the recent decline in 2018. Of particular note, Colombia, Macao (China), Peru, and Qatar have demonstrated consistent improvement across all three core subjects since their respective initial participation in PISA.

First published in 2001, PISA results have been widely recognised as the international ‘gold standard’ for assessing educational quality, serving as a definitive measure for the overall effectiveness of school systems worldwide. A 2012 OECD report affirms PISA’s considerable influence, stating, ‘PISA has become accepted as a reliable instrument for benchmarking student performance worldwide, and PISA results have had an influence on policy reform in the majority of participating countries/economies’.8

The triennial publication of PISA results in early December consistently draws significant attention to the average score rankings of participating countries. With every new set of data, there is a predictable pattern of governmental concern, enhanced media scrutiny, and increased public calls for greater accountability in relation to perceived shortcomings within national education systems. A Google search combining ‘PISA’ with terms such as ‘crisis’, ‘failure’, or ‘decline’ yields numerous international examples of these associations. For instance:

■ PISA tests: the crisis of basic learning (5 December 2023, La Nación)

■ Finland’s PISA results continue to decline, sparking concern (Helsinki Times, 6 December 2023)

■ Dutch kids’ reading, maths, and science skills are declining (NL Times, 5 December 2023)

■ The cost of failing to make the learning crisis a national priority is high (UNICEF, 7 December 2023).

The term ‘PISA-shock’ was initially coined in Germany following the first PISA assessment, which revealed that the nation’s highly-regarded education system was, in fact, performing at an average level. This unexpected finding had a profound effect, prompting substantial educational reforms throughout the country. In response to similar ‘PISA-shocks’, other countries, including Norway, Denmark, Sweden, and Japan, have likewise implemented new curricula. Additionally, a number of nations have introduced new national standards and

mandatory national testing systems as a direct consequence of their respective PISA outcomes.

Although the causal relationships between school practices and student performance in PISA are complex and sometimes unclear, PISA remains unique in positioning itself as a singular international assessment programme designed to inform governmental policy and advocate for best practices in education. Despite the limitations of the data in establishing definitive causality, PISA exerts considerable influence within policy discourse, largely due to its strategic engagement with international media. This strategic focus increases public awareness of national educational outcomes and places substantial pressure on governments to adopt policies aligned with PISA’s recommendations. As a result, PISA has evolved into an influential component of political debate, functioning not merely as an impartial repository of evidence but increasingly as a catalyst that actively shapes educational policy decisions and, at times, amplifies ideological debates.

An analysis of mean PISA scores reveals that most OECD member countries are clustered within a central cohort, displaying only minor differences in their average performance levels. This situation may be aptly compared to a cycling peloton, in which the aerodynamic benefits of group riding result in most competitors achieving closely aligned finishing times. Consequently, even relatively minor variations in a nation’s aggregate score can lead to shifts of 10 to 20 positions within the national rankings. Furthermore, a notable degree of uncertainty is inherent in the published PISA scores. This uncertainty arises in part from sampling errors associated with the measurement process, as well as supplementary ambiguities arising from the methodologies used to calculate the reported results.

In May 2014, The Guardian, a prominent British newspaper, published an open letter addressed to the PISA Director. This correspondence, endorsed by over 100 education researchers and educators from around the world, highlighted significant concerns regarding the increasingly negative impact of PISA on global education policies. The signatories specifically criticised PISA for encouraging an excessive dependence on standardised testing, which, in their view, has led to an undue narrowing of curricula with an overt focus on measurable outcomes. Such an approach, they argued, has resulted in the marginalisation of other important educational objectives, particularly those relating to the fundamental purpose and broader nature of education. This tendency is attributed to the OECD’s emphasis on economic development and its prioritisation of preparing students primarily for the workforce.

Commercial interests are notably advanced through the pursuit of higher test scores. The Educational Testing Service (ETS), a prominent assessment and measurement organisation based in the United States, serves as one of the principal contractors for PISA. In 2024, ETS was appointed as the international digital delivery platform provider for the OECD’s PISA-based Test for Schools (PBTS) digital assessment, with contractual responsibilities extending through to 2029. This role entails ETS designing, developing, and maintaining an international digital delivery platform for the PBTS.

Our government will ensure that we have a knowledge-rich curriculum, robust measures of student progress, and structured literacy in every primary classroom. Minister of Education Media Release (5 December 2023)

Dr Michael Johnston, Senior Fellow for Education at The New Zealand Initiative and a member of the Ministry of Education’s Curriculum Coherence Group, which advises on the development of knowledge-rich curricula, has voiced strong criticism about the current state of education in New Zealand. In his newsletters dated 31 January and 19 June 2025, Dr Johnston asserted that the education system has been in continuous decline over the past two decades. He principally attributes this deterioration to the introduction of the Ministry of Education’s 2007 curriculum, describing it as ‘largely devoid of substantive knowledge’ and identifying it as a significant factor in what he terms a ‘death spiral’ within the state-run education system. Despite these criticisms, Dr Johnston expressed cautious optimism concerning the Minister of Education’s commitment to systemic reform, observing that the Minister supports a more active and direct role for the state in overseeing educational improvement.

The Minister of Education has described the current curriculum as ‘vague, inconsistent, unclear, and waffly’9. Consequently, the transition towards structured learning forms part of broader efforts to reform the curriculum. According to the Cabinet Paper dated 9 December 2024, the initiative to establish a knowledge-rich curriculum, grounded in the principles of the science of learning, is proceeding according to schedule and has received favourable responses from both the education sector and subject-matter experts.

The science of learning employs a rigorous scientific method to investigate the biological, cognitive, and psychological mechanisms underlying the learning process. It draws upon insights from multiple disciplines, including education, psychology, neuroscience, cognitive science, and computer science, to provide a comprehensive understanding of how individuals reason, perceive, behave, and respond within educational contexts.

Nevertheless, education, at its core, is a humanistic discipline that does not readily conform to a purely scientific model. Teaching and learning are inherently shaped by human interpretation and are subject to considerable variation across individuals and contexts. This intrinsic complexity makes it difficult to fully reduce education to a ‘science of learning’. Rather, education necessitates informed and subjective judgements about learning, based on a broad array of criteria. It also requires the skilled management of human behaviour among different age groups, each experiencing rapid and substantial emotional, intellectual, psychological, and physical development.

A knowledge-rich curriculum involves the deliberate and systematic transmission of knowledge, defined as a specific set of facts. This is achieved through the implementation of carefully structured, sequential units of study, where each learning stage builds on the foundations established by prior instruction. In this pedagogical approach, the teacher’s role is to guide learners through stages of intellectual development to support the progressive integration and expansion of their knowledge. Given that the acquisition of knowledge is regarded as the central objective, it must occupy a primary place within curriculum design, supported by teaching methods aimed at promoting thorough engagement with academic content.

An illustrative example can be found in classrooms examining the Pacific region, where the primary aim may extend beyond the mere acquisition of explicit knowledge. For instance, students

continued on p.12

might engage in preparing Samoan pani popo (coconut buns), comparing both traditional and contemporary preparation techniques. In such cases, it is often the collaborative and experiential process of making these buns that is the most impactful and engaging aspect, rather than the memorisation of specific factual information about Pacific nations. Such instances raise a fundamental question: What is the principal aim of our education system? Should the emphasis be placed on the retention of facts and the development of a substantive knowledge base, or is it more appropriate to prioritise outcomes that are broader, less quantifiable, and inherently more adaptable and responsive to diverse educational needs?

Education systems around the world, particularly in highperforming countries such as Finland and Singapore, emphasise not only the acquisition of substantive content knowledge but also the ability to apply this knowledge in innovative and critical ways. For example, Finnish schools adhere to a national core curriculum while permitting local institutions to develop their own detailed curricular frameworks. This approach is designed to promote holistic student development, foster the cultivation of critical thinking skills, and accommodate individual differences in learning, rather than relying solely on rote memorisation and standardised testing.

A core principle underpinning the science of learning asserts that education and curriculum design should provide all students, including those from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds, with equal access to disciplinary knowledge. This approach supports the development of a comprehensive and systematic understanding of specialised knowledge that extends beyond practical skills or personal know-how. The provision of such equitable access is regarded as a matter of ‘distributional justice’, underscoring the necessity for every learner to receive a common set of recognised knowledge and the opportunity to contribute to its further development during their education.

Dr Johnston highlights the critical role of knowledge in securing academic success, referencing educational sociologist Michael F. D. Young’s concept of ‘powerful knowledge’. Young defines powerful knowledge as ‘superior knowledge’ spanning diverse fields. He maintains that equitable access to such knowledge should be regarded as a fundamental entitlement for all students, regardless of their perceived academic ability. According to Young, powerful knowledge is inherently linked to social justice, as it forms the basis for a fair and inclusive allocation of educational opportunities. While curricula centred on powerful knowledge are often found in exclusive, fee-paying schools in England, for example, Young advocates for their universal implementation across all educational settings, not solely within privileged institutions.

The science of learning offers valuable insights into the processes through which students acquire knowledge; nevertheless, it is not a definitive or static discipline. As with all scientific fields, its principles are provisional, informed by the best available evidence, and open to refinement as new research emerges. Yet, the term ‘science of learning’ is often used to imply a singular, unequivocal approach to improving teaching practice. In reality, the delivery of effective and equitable education depends on a robust profession, one that is not only guided by evidence-based practices but is also fundamentally grounded in the expertise of educators and a thorough understanding of individual student needs.

In an upcoming publication, Dr Johnston and colleagues note, ‘Ideally, future learners will confidently say: ‘I use the internet,

but I don’t have to look everything up, because I’ve learned and remembered what matters’. Such deep, resilient knowledge will be essential in navigating a world of endless information – and protecting our minds from cognitive decline amid constant technological distractions.’10 The rapid advancement of knowledge, particularly in the context of artificial intelligence (AI), underscores the necessity of moving beyond a narrowly prescriptive curriculum. As new technologies reshape the ways in which information is accessed and processed, it becomes increasingly important for educators to equip students with the critical skills necessary to engage with, evaluate and apply this ever-growing body of knowledge.

Notable educational scholars, such as Yong Zhao and Pasi Sahlberg, contend that a rigidly prescriptive curriculum, which focuses predominantly on rote memorisation of static facts, is insufficient for preparing students to meet the challenges of a complex, modern world. Zhao’s research highlights the importance of an education system that fosters diverse talents and creativity.11 Sahlberg, on the other hand, cites the effectiveness of Finnish educational reforms, which achieve a balance between substantive knowledge acquisition and the cultivation of critical thinking and creativity. 12 Developing such skills requires pedagogical practices that differ markedly from those approaches that are primarily concerned with the transmission and memorisation of factual information content, as emphasised by the science of learning.

1 Newsroom (Laura Walters), 20 March 2024: Education minister vows to close yawning equity gap.

2 Hirsch Jr, E. D. (1999). The schools we need and why we don’t have them. Anchor Books. (p. 33).

3 The New Zealand Initiative (27 June 2024). Insights Newsletter, 23: Towards a knowledge-rich curriculum.

4 Newsroom (Laura Walters), 20 March 2024: Education minister vows to close yawning equity gap.

5 Commission on Education in New Zealand (1962, July). Report of the Commission on Education in New Zealand (The Currie Commission), pp. 27–28.

6 New Zealand Herald, report, ‘Back to basics says National Party’, 8 July 1989.

7 Newstalk ZB (Mike Hosking Breakfast), 6 December 2023.

8 Breakspear, S. (2012). The policy impact of PISA: An exploration of the normative effects of international benchmarking in school system performance. OECD Education Working Papers, 71.

9 New Zealand Herald,·3 May 2024: Education Minister Erica Stanford can ‘retire happy’ if structured learning takes off in NZ schools.

10 Oakley, B., Johnston, M., Chen, K. Z., Jung, E., & Sejnowski, T. (2025). ‘The memory paradox: why our brains need knowledge in an age of AI.’ In The future of artificial intelligence: economics, society, risks and global policy (Springer Nature, forthcoming).

11 Zhao, Y. (2012). World class learners: Educating creative and entrepreneurial students. Corwin Press.

12 Sahlberg, P. (2011). Finnish lessons: What can the world learn from educational change in Finland? Teachers College Press.

The only 5-Star rated Playground Surfacing in New Zealand

SAFE:

Cushionfall® playground mulch is specially treated so it’s free from nails and splinters. Many cheaper or imported products aren’t nail-free or splinter-free.

LONG-LASTING: tests have proven that Cushionfall® playground mulch actually becomes more effective over time. After 5 years it will be in better condition than ever!

QUICK-DRAINING: the children can start playing as soon as it stops raining.

WIND-PROOF:

Cushionfall® playground wood chips are shaped in such a way so that they’re not disturbed or blown around by the wind.

COLOURFUL: available in 8 non-toxic, UV-resistant colours, Cushionfall® playground mulch makes playtime fun!

Emalene Cull and Mary-Anne Murphy

THE MODERN CLASSROOM IS more than a site for delivering content—it is a relational space where the brain, body, and heart come together in the service of learning. As educators, we’re learning – through both research and reflection – that the most powerful teaching happens when we hold thinking and feeling side by side. In these classrooms, young people are not only acquiring knowledge, but developing the emotional tools and relationships that help them apply it meaningfully in their lives.

At St Joseph’s Catholic School in Paeroa, this integration of head and heart is not just a philosophy – it’s embedded into practice. Over the past two years, the school has taken a considered and community-led approach to Social and Emotional Learning (SEL). The result is a school culture where students learn to understand their emotions, relate respectfully to others, and build the cognitive flexibility and confidence to thrive.

Their Cognitive-Affective Learning (CAL) framework illuminates that deep learning happens when cognitive and emotional systems work in harmony. When teachers recognise the impact of emotion on attention, memory, and motivation, and intentionally create emotionally safe and culturally responsive environments, learning is not only possible – it flourishes (Immordino-Yang, 2016; Cognitive-Affective Learning, 2025).

Instead of a quick fix, St Joseph’s took a thoughtful, researchinformed approach. They drew on neuroscience to understand how stress affects learning. They grounded their decisions in local culture and their values. And they worked alongside EI specialists to co-construct a developmental, culturally anchored approach that put relationships at the centre.

This starting point reflects a foundational insight from the CAL model: the conditions for learning are as important as the curriculum itself. When students feel they belong, are known, and are emotionally regulated, their brains are better able to process, retain, and transfer learning (DarlingHammond et al., 2019).

St Joseph’s journey blends what we know from neuroscience, emotional intelligence, trauma-informed practices, and high-impact teaching into a cohesive model of whole-child education – where relationships, routines, and rigorous learning experiences intersect.

Listening first: Where the journey began

Two years ago, the school asked: what do our tamariki really need to thrive? Through deep consultation with students, whānau, staff, and parish, a clear theme emerged – our children needed support with emotions, stress, and social challenges (Education Gazette, 2025).

Interweaving head and heart: Teaching SEL through a learning lens

Rather than placing SEL in a separate box, St Joseph’s teachers deliberately teach emotional and relational skills in tandem with cognitive ones. Each stage of their SEL programme is developmentally aligned, reflecting both the brain’s readiness and the emotional demands of that age group.

Years 0–2: Foundations for regulation and belonging

In the first few years of learning (Years 0–2), children build essential skills in literacy and numeracy. During this time, they also start to understand and name their emotions, learning basic strategies for self-awareness. Teachers use tools like visuals, storytelling, and structured routines to help children connect emotions to language and behaviours. This creates consistency and comfort, which are crucial for young children as they begin to form their sense of identity and safety.

When children can regulate their emotions and feel a strong sense of belonging, they’re more able to focus on learning. Emotional stability makes it easier for them to listen, follow instructions, take turns, and engage in learning activities. Emotional regulation isn’t a distraction from academic progress –it actually helps it. A calm, connected child is better able to focus on important tasks like decoding words, recognising symbols,

and developing oral language skills. In this way, emotional regulation supports learning, rather than competing with it.

By consistently modeling and practicing emotional and academic skills, teachers help children not only develop emotional literacy, but also reduce cognitive overload. This allows them to focus more effectively on core learning tasks (Centre for Education Statistics and Evaluation, 2017). These early experiences don’t just teach specific skills – they also build the foundation for later learning, helping children develop the ability to self-regulate, pay attention, and cultivate a joyful curiosity about the world around them.

Years 3–5: Building readiness for deep learning In the middle years, students develop a more detailed understanding of how their brains work – particularly in relation to stress and regulation. They learn about the roles of the amygdala and prefrontal cortex and explore practical strategies to calm their nervous system and regain focus when emotions feel overwhelming.

These insights don’t sit in isolation – they create the foundation for learning. Students who can manage their emotions are more receptive to teaching. Their attention lasts longer. They are more able to participate in group learning and respond to feedback. In other words, emotional readiness becomes cognitive readiness

This foundational self-regulation supports the effectiveness of highimpact teaching strategies: clear modelling, guided practice, targeted feedback, and metacognitive reflection. When students can name what’s going on internally, they are far better equipped to take risks in learning, persist through challenge, and engage deeply with content (DarlingHammond et al., 2019; CESE, 2017).

Years 6–8: Navigating pressure and strengthening connection For senior students, the focus shifts toward the relational and emotional complexity that emerges in early adolescence. Students explore anxiety, identity, and the social pressures that can shape behaviour –particularly in peer relationships. The learning is real, relevant, and personal.

safe with one another, their learning – and their wellbeing – are strengthened (Immordino-Yang, 2016).

Peer mentoring and student-led initiatives at this level also give learners the opportunity to practise leadership in meaningful, emotionally attuned ways – deepening their sense of purpose and reinforcing their emotional competence in action.

Senior students develop deeper tools for managing pressure, anxiety, and conflict. They use techniques like journaling, box breathing, and peer support roles to strengthen self-management and contribute positively to others.

They begin leading playground relationships and mentoring younger peers – giving their learning relevance, responsibility, and emotional resonance. This reinforces what CAL describes as purposeful learning anchored in aronga (direction), where students know not just how to act, but why it matters.

The real magic of the CAL approach is the how of teaching. Across the school, teachers use consistent routines and explicit instruction to guide students from surface understanding to deep application.

Through practices like journaling, role play, structured discussion, and leadership roles, students learn how to stand steady in their values, set healthy boundaries, and support others with empathy. They begin to understand how anxiety might show up in themselves or their peers, and what relational tools they can draw on – whether that’s breathing, honest dialogue, or simply stepping back.

This stage is not just about managing stress; it’s about cultivating social wisdom. The relational focus mirrors what the science of learning and the CAL framework both emphasise: learning is a deeply social act. When students feel connected, trusted, and

Emotion check-ins, shared vocabulary, co-constructed strategies, and predictable classroom rituals help students feel safe and engaged. This structure is particularly vital for learners with trauma histories, whose brains seek consistency to reduce threat and enable reasoning (Perry & Szalavitz, 2006).

Through the CAL lens, we see how cognitive rigour and affective connection are not opposites – they amplify one another. Students are encouraged to think about thinking, to connect learning across subjects and emotions, and to see their own role in the learning process.

Whānau and community: Extending the learning loop

True to the CAL principle of whanaungatanga, St Joseph’s extended the learning journey into the home. Whānau were brought into the conversation early, helping identify needs, shape goals, and practise strategies at home.

This two-way partnership has led to increased emotional dialogue at home, consistency in expectations, and stronger school-home connections. It highlights that powerful learning isn’t confined to classrooms – it flows through relationships, language, and daily interactions.

Anchoring in identity: Spirit, culture, and character

St Joseph’s SEL programme is infused with the school’s special character. Emotional development is not presented as a separate curriculum – it is part of living with faith, humility, and love. Students are reminded that their worth is not in their performance, but in their relationships.

continued on p.16

Quality professional lighting and great pricing.

Truss, Clamps, Fresnels, Parcans, profiles and lenses . . .

Challenger 1000 Portable PA system with stand and wireless microphone For sports, Assembly, Jump Jam and performances

Best sounding portable PA in New Zealand. Fully featured, top quality and easy to use. Includes a weather cover for outdoor use.

Built-in trolley and powerful rechargeable batteries so you can take it anywhere.

$2749 – 20% SALE $2199+gst for the wireless PA system

By aligning emotional intelligence with Catholic values, and teaching it through structured, evidence-informed practice, the school brings depth and authenticity to learning. This reflects CAL’s call to honour learner identity – spiritual, cultural, emotional, and cognitive – as inseparable dimensions of success.

The results: Learning that lasts

Since implementing their programme, the school has seen measurable shifts: students more confident in naming and managing their emotions, greater empathy in social interactions, and improved focus and participation in learning.

These aren’t just signs of a wellbeing programme – they’re signs of a learning culture built on trust, agency, and connection. Students know they belong. They know how their brain works. They know how to learn.

Principal Emalene Cull reflects ‘Tamariki are learning that emotions are not something to fear – they are something to understand. They feel heard, valued, and empowered to navigate life with confidence, empathy and strength’ (Education Gazette, 2025, p. 26).

Final reflections: Learning that feels, connects and grows St Joseph’s offers a powerful reminder that emotional and academic development are not separate agendas. When we integrate them, using the best of what we know about how the brain learns and how humans connect, we foster learners who are not just capable – but deeply equipped.

This is the heart of their Cognitive-Affective Learning framework: an integration of thought and emotion, culture and intellect, connection and challenge – interlaced to create a dynamic, unified approach.

Archer, A. L., & Hughes, C. A. (2011). Explicit instruction: Effective and efficient teaching. Guilford Press.

Centre for Education Statistics and Evaluation. (2017). Cognitive load theory: Research that teachers really need to understand. https:// www.cese.nsw.gov.au

Chafouleas, S. M., Johnson, A. H., Overstreet, S., & Santos, N. M. (2016). Toward a blueprint for trauma-informed service delivery in schools. School Mental Health, 8(1), 144–162.

Cognitive-Affective Learning. (2025). Cognitive-Affective Learning: A Thriving Mind in a Connected Heart [White paper].

Darling-Hammond, L., Flook, L., Cook-Harvey, C., Barron, B., & Osher, D. (2019). Implications for educational practice of the science of learning and development. Applied Developmental Science, 24(2), 97–130.

Education Gazette. (2025, May 26). Weaving emotional intelligence into everyday learning. https://gazette.education.govt.nz

Immordino-Yang, M. H. (2016). Emotions, learning, and the brain: Exploring the educational implications of affective neuroscience W.W. Norton.

Immordino-Yang, M. H., & Damasio, A. (2007). We feel, therefore we learn: The relevance of affective and social neuroscience to education. Mind, Brain, and Education, 1(1), 3–10. Perry, B. D., & Szalavitz, M. (2006). The boy who was raised as a dog. Basic Books. Victorian Department of Education. (2020). High impact teaching strategies: Excellence in teaching and learning. https:// www.education.vic.gov.

Lee Elliot Major OBE PROFESSOR OF SOCIAL MOBILITY, UNIVERSITY OF EXETER

This article was first published in the ICP Magazine – the magazine of the International Confederation of Principals (ICP) and is republished with permission.

IN BRITAIN, I’M OFTEN introduced as the binman turned professor. It’s a story that surprises people, particularly in the country known for its rigid class system. But I share itwherever I speak with school and teacher leaders – because it speaks to a truth that sadly, applies to all societies across our world: too many children are still held back by the circumstances into which they were born. I grew up in a part of West London in the shadows of Heathrow Airport, a place known for its youth offenders’ prison. I left home at 15 with very little to my name. A teacher encouraged me to go back to school. A friend’s family took me in. My mum, who worked for the local council, helped me get holiday jobs – cleaning streets, collecting bins, washing dishes. During evenings I worked as an attendant in a petrol station. That was my classroom, too. I learned resilience, humility, how to get on with people and how to survive when there’s no safety net to fall back on. And I learned that talent lives everywhere in many different forms – in every neighbourhood, in every accent, in every child.

Too often, equity is treated as an optional extra – when in reality, it should be the central purpose of education. We can’t keep holding teachers solely responsible for solving the deep inequalities outside their classrooms. We need an approach that doesn’t allow so many children to leave school feeling like failures.

Equity is about giving every child the support they need to thrive – not just the same resources or the same expectations. It’s about recognising that not all children start from the same place. Some need more. Crucially, equity is a mindset. It’s a belief that all children – whatever their background – have potential, and it’s our job as educators to remove the barriers in their way.

It’s taken me a while to realise that my BACKGROUND isn’t something to be hidden – it’s a STRENGTH. It’s what fuels my MISSION to work with teachers . . .

When I was awarded an OBE at Buckingham Palace from HRH the Queen for my work in education, I felt proud. Yet your history never truly leaves you. I still imagined a ghost from my past was going to tap me on the shoulder and say, ‘Lee, you don’t deserve to be here, go back to where you come from!’ It’s taken me a while to realise that my background isn’t something to be hidden – it’s a strength. It’s what fuels my mission to work with teachers across the world: to help level the playing field of education so that no child is defined by their postcode or their parents’ income.

Across the world, millions of children are being quietly left behind – not because they lack ambition, but because they face cultural and material barriers the system was never designed to help them overcome. A working-class boy from a London estate who doesn’t know the unwritten middleclass rules of the classroom. A girl from a poor village walking miles to school carrying her text books in Nairobi, or a teenager in Manila who spends her evenings looking after her siblings while classmates get help from private tutors. These children don’t lack ambition –they lack opportunity. These children don’t need to be fixed. The system does.

The equity approach encourages us to look at children not through a lens of deficit – what they lack – but through a lens of potential – what they could become, if only we remove the obstacles in their way.

In my talks and workshops with teacher leaders across the UK and internationally, I share four levers that can drive more equitable practice in schools: language, pedagogy, curriculum, and partnerships.

These are not just ideas – they are tools for change.

Strengths-based language

The language we use matters. The words that we speak transmit our values and reveal our inner assumptions.

When we label children as ‘disadvantaged pupils,’ we risk defining them by what they lack. Instead, I encourage schools to use terms like ‘children from under-resourced backgrounds’ or ‘pupils facing extra barriers to learning.’ That way, we focus on the systematic inequities they face – not the child.

Avoid terms like ‘hard-to-reach families.’ Ask instead: how can we be easier to reach? Talk about parent and community partnerships not engagement.

Unconscious bias is a universal trait all humans have. Research shows that teachers often – without meaning to – give less detailed feedback, less eye contact, and fewer opportunities to children from lower-income homes, or children less like them.

continued on p.18

In every classroom meanwhile there are ‘hidden learners’ doing what so many pupils are good at doing: pretending to listen!

We can all make classroom practice genuinely more inclusive. It starts with reflective practice: watching each other teach, talking about hidden learners, and creating space for every child to be seen and supported.

Curriculum for all talents

Academic results are essential, particularly basic literacy and numeracy – but it’s not the whole picture of human life.

We must also value creativity, kindness, leadership, and resilience. The best schools I visit around the world celebrate all forms of human talent – not just those measured by grades. Arts and sports have inherent education value in themselves.

What we teach should reflect the children we teach. They should see themselves – and others – in the stories, texts, and topics we explore. Shakespeare belongs in every classroom, but so do local voices, contemporary artists, and unsung heroes from every culture.

What we teach should reflect the children we teach.

Nurturing relationships

Equity starts with mutually respectful relationships. That means partnerships with families and communities – not transactional interactions that treat parents and pupils as numbers not people.

One in five schools in England now run food banks. But those spaces can do more than provide food – they can be places where trust is built, where families feel welcome, and where schools become the heart of the community.

We should value time spent with parents as much as time spent on education statistics. The best insights don’t always come from spreadsheets – they come from real conversations in safe spaces.

Equity scorecard: A practical tool

To support schools in taking action, we’ve developed the Equity Scorecard – a simple self – evaluation tool that helps schools assess how well they are supporting children facing extra barriers. It’s already being used in secondary schools across the UK, with versions for primary and post-16 settings in development. What’s powerful is how willingly schools have embraced it – not because they were told to, but because they want to do better. Because they believe in what equity stands for. My dream is simple: a school system where background never dictates destiny. Where every child – whatever their starting point – has the chance to discover their talents, fulfil their potential, and choose their own path in life. That’s not just a hope. With an equity mindset, it’s a promise we can make real.

Lee Elliot Major is Professor of Social Mobility atthe University of Exeter

Elliot Major, L., & Briant, E. (2023). Equity ineducation: Levelling the playing field of learning – a practical guide for teachers. John CattEducational.

Brooks, B., Sim, A., & Elliot Major, L (2024) TheEquity Scorecard, A new approach to assessingeducation equity in schools, SouthWest SocialMobility Commission.

Equity changed my life. And it can change the lives of millions more. As a school leader, you hold the power to reshape what’s possible for every child who walks through your gates.

"Leadership isn’t one-size-fits-all but data and analysis can help us tailor the journey."

Authors: Dr Natalia Xie, Tim White Education Workforce | Ministry of Education

Email: TePou.OhumahiMatauranga@education.govt.nz

Around 428* first-time primary principals were appointed in 2022-2024

45% of them followed the sequential pathway 40% had no middle management experience 10% had no senior leadership experience 5% had no middle nor senior experience

Career progression 3 milestones

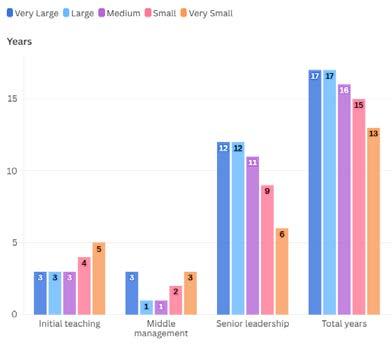

New milestone pattern “4-2-10” years

“Step-Up” strategy, early stages “Opportunity-First” strategy, principalship

Twice Urban large school principals had 12 years in senior roles twice that of rural small school principals

2-4 yrs

Māori medium principal had 24 years less senior experience

20%

direct internal promotion rate for first-time principalship on average

42% direct internal promotion rate for first-time principalship in Māori Medium schools

* Some inconsistent records e.g., negative teaching years were excluded.

Foreword

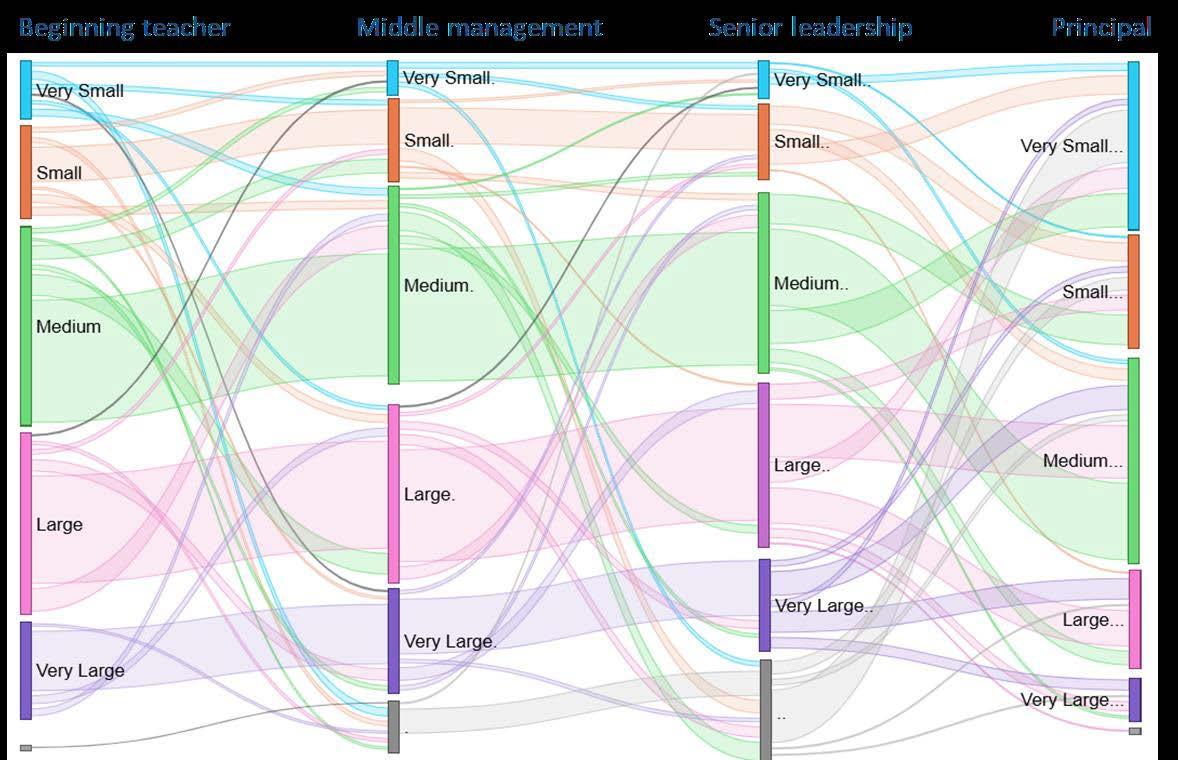

• For the first time, this analysis maps the complex journey of New Zealand’s primary school principals from beginning teachers to middle management, senior leadership, and ultimately, their first principalship. Drawing on ten years of career data, with a focus on the most recent three years (2022 –2024), we highlight emerging trends that challenge traditional assumptions about leadership development.

• This work is indicative, not a precise prediction. It offers a high-level view of career pathways while recognising each journey is unique.

Methodology discussion

• We acknowledge that some very small schools may not have formal middle or senior leadership roles. To address this, we developed a predictive model using unit allowances and rankings based on school size.

• This is our initial attempt to map aspiring principals' career pathways. We recognise there is room for improvement, given the education workforce’s dynamic and complex nature.

Figure 1. Beyond the traditional pathway: mapping the journey to first -time principalship (2022–2024)

The leadership pipeline: a complex, non-linear reality

• Over 2022-2024, approximately 428 *new first-time primary principals were appointed.

• Fewer than half (45%) followed the conventional sequential pathway: beginning teacher → middle management → senior leadership → principal.

• The majority (55%) took unconventional routes: 40% skipped middle management, 10% skipped senior leadership, and 5% had neither prior to appointment.

Figure 2. Career patterns change significantly over time

New “4-2-10” tenure pattern is emerging

• From 2022–2024, a new career trajectory emerged: 4 years in initial teaching, 2 years in middle management, and 10 years in senior leadership before becoming principal.

• This contrasts with the “2 –1–7” pattern observed from 2015–2017, reflecting a longer preparation phase for leadership roles.

Figure 3. School size significantly influences the aspiring principal career patterns

Senior leadership experience remains critical—but unevenly distributed

• Despite the variety of paths, senior leadership is the longest and most important stage, averaging 10 years.

• Principals in large urban schools' average 12 years in senior leadership double that of small rural schools (6 years).

* Some inconsistent records e.g., negative teaching years were excluded.

“Step-Up” strategy “Opportunity-First” strategy

Two Distinct Career Strategies Emerge

• “Step-Up” strategy in early stages: The majority (80%) stay in similar settings (urban/rural, school size) as they progress to middle management and senior leadership roles.

• “Opportunity-First” strategy for principalship: At the point of principal appointment, 50-70% senior leaders prioritise the principalship opportunity and shift context, even if it means moving to a rural area or a smaller school. For example, over 70% of newly appointed rural principals came from more urban contexts

* Direct internal promotion is the appointment of an educator who was working at the same school at the time of their promotion to first -time principal.

Direct internal promotions is on the rise

• Larger schools are more likely to appoint internal candidates, while smaller schools tend to recruit externally.

• Rural schools show the lowest internal promotion rates, possibly because they prefer external candidates or have fewer internal staff with senior leadership experience to draw from.

• Māori medium schools have higher internal promotion rates than English medium schools reflecting a strong preference for cultural continuity and alignment with the school’s Kaupapa (principles).

Looking for a more secure and manageable way to control access, South Otago High School replaced its old key system with eCLIQ from ASSA ABLOY. Installed in just one day, the new system gives staff full control over 70 keys and the doors they open.

South Otago High School has been part of the Balclutha community since 1926. It’s the largest school in the region, with 530 students, six teaching blocks, and 17 hectares of playing fields and courts, serving families from across South Otago’s rural and small-town areas.

Challenge and pain points for the School