16 minute read

Charting closer ties

Christopher Luxon proposes a more ambitious approach to broadening the India–New Zealand relationship.

The Raisina Dialogue is a forum that provides a moment every year for thought-leaders from across the world to focus their collective minds on the contemporary strategic challenges being navigated in the Indian Ocean. Under the direction of Dr Jaishankar and Samir Saran over the past ten years, it has grown into a hugely influential forum, attracting six former heads of government and ministers from over 30 countries in 2025. A keynote speaker, Christopher Luxon stressed the longstanding links between India and New Zealand and espoused a vision for closer contact in future to meet growing economic and security challenges.

It is more than 200 years since Indians and New Zealanders first began living side-by-side. At the beginning of the 19th century — well before we became a nation — Indian sailors jumped ship in New Zealand, with some meeting locals and marrying into our indigenous Māori tribes. A few years later, Māori traders began travelling to Kolkata to sell tree trunks used in sailing ships. An exchange that echoes down the ages.

Just as they were 200 years ago, Kiwi–Indians today are fully integrated into our multicultural society. New Zealanders of Indian heritage comprise 11 per cent of the people living in Auckland, our biggest city. I have brought with me to New Delhi a selection of Kiwi–Indian community leaders: members of Parliament, captains of industry, professional cricketers and even an online influencer who has revolutionised investment for women the world over. In short, a selection of Kiwi–Indians who get up every single morning to make New Zealand a better place to live. And our trade has diversified considerably from wood thanks to the increased sophistication of your economy. India today is a critical source of pharmaceuticals and machinery for us. While we are a great tourism and education destination for you.

India has become an ever more significant feature of our society. And yet, while there has been much that has developed and changed, there has been something missing at the core of our relationship. With a country as consequential as India, we need rich political interaction, engaged militaries, strong economic architecture and connections that support a diaspora that bridges between our two great nations.

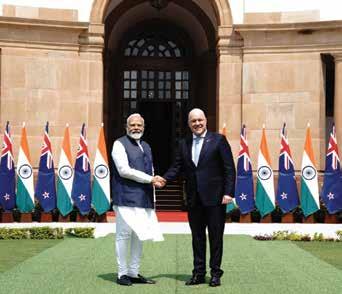

Prime Minister Narendra Modi and I met on 17 March and charted out the future of our two countries’ relationship — a future that builds from where we have been. One that is wholly more ambitious about what we will do together in the future.

l We agreed to our defence forces building greater strategic trust with one another, while deploying together and training together more.

l We want our scientists collaborating on global challenges like climate change and on commercial opportunities like space.

l We are supporting our businesses to improve air links and build primary sector co-operation. l We will facilitate students, young professionals and tourists to move between our countries. l And we have instructed our trade negotiators to get on and negotiate a free trade agreement between our two great nations.

A comprehensive agenda to underpin a comprehensive relationship. As we look to the future, the opportunity for both our governments is to sustain that momentum. Not only to follow through on the commitments we have made to one another. But to proactively build on that platform, by exploring new opportunities and creating new architecture. To ensure that we are creating strategic trust and commercial connection between two countries at the bookends of our wide Indo-Pacific region.

Biggest opportunities

There are many reasons to be excited about our region. I want to single out the two biggest opportunities. First, India and New Zealand are fortunate enough to live in the world’s most economically dynamic region. The Indo-Pacific region will represent two-thirds of global economic growth over the coming years. By 2030, it will be home to two-thirds of the world’s middle-class consumers.

And India itself lies at the heart of this exciting economic future. It is easy to focus on the troubles the world faces, but it is worth reflecting for a moment on what economic development at this scale means at a human level. Here in India, you have gone from only the very few in rural areas having a water or power connection to almost everyone. It means people with better health and education outcomes. And that creates hope and optimism about the future for individuals and their families. Replicated across literally hundreds of millions of people, that process of development generates dynamic economies. Growth that offers massive opportunities for every country in the Indo-Pacific region, and families and individuals within them.

The second big opportunity is technological change. We are on the cusp of a transformation of our economies and societies in a way that we can barely now imagine. I am talking about artificial intelligence, which is within reach of achieving the cognitive powers of a human being. But I am also thinking of a range of other technologies — quantum, biotech, advanced manufacturing — that are going to have profound impacts on our economies. It has felt like this technological transformation has been long-heralded, but never quite arrived. Well, it seems to me that a series of innovations — the always online world, big data, powerful computing, machine learning — are cumulating in ways that are going to tip over into a dislocation that is new and altogether different.

The game is about to change. We are on the cusp of an explosion in the application of artificial intelligence, a technology that will have an impact across the whole economy, not just in one or two sectors. A technology that will transform the way we work, study and entertain ourselves. A technology that will force governments to think in entirely different ways about how they deliver public services and secure their nations. Certainly, this presents risks that will need to be managed. For example, militaries are already using AI, which means the international community is going to need to develop new norms about how this is done in a way that ensures compliance with the rules of war and ensures human responsibility in conflict.

But my message is that, while we need to manage change, we cannot allow ourselves to be paralysed by the risks. For those who believe they can out-compete through this period of technological dislocation, the opportunities are there. The citizens, the companies and the countries that embrace the coming change will be the ones that reap the dividends.

Geo-strategic risks

Yet there is also no doubt that there are fundamental trend lines in the Indo-Pacific region that present geo-strategic risks to growth and prosperity. These have longterm drivers that are not going away, and have been amplified by recent events. Past assumptions — that underpinned the previous generation’s geopolitical calculations — are being upended.

A fortnight ago, the Singaporean foreign minister, Vivian Balakrishnan, put this change eloquently when he said: ‘the world is now shifting from unipolarity to multipolarity, from free trade to protectionism, from multilateralism to unilateralism, from globalisation to hyper-nationalism, from openness to xenophobia, from optimism to anxiety’. This is a global change, not isolated to one region. Certainly, though, we live today in an Indo-Pacific region navigating contest and rivalry, with a period of strategic uncertainty. I would highlight three big shifts that make for challenging times ahead.

First, we are seeing rules giving way to power: Previously, we could count on countries respecting the UN Charter, the law of the sea and world trade rules. That sadly cannot be assumed in an age of sharper competition. Instead, we risk dangerous miscalculation at flashpoints. These range from the militarisation of disputed reefs to dangerous air movements; from land border incursions to breakout nuclear capabilities. Of course, it is not just flashpoints, but a slow shift in Indo-Pacific realities that change calculations. Recent demonstrations of naval force near New Zealand’s maritime surrounds, for example, sent a signal that alarmed many of my fellow citizens.

Second, we are witnessing a shift from economics to security: After the Cold War, the dominant paradigm in relations between Indo-Pacific countries was a sustained effort to raise material living standards by tending to our economies. Make no mistake, ‘bread and butter’ issues still loom very large, and are a priority for governments all around the region. Indeed, economic growth is my government’s highest priority.

Military build-ups

But across the Indo-Pacific region, we also see governments dedicating increased attention and resource to military modernisation. Military build-ups reflect a need to prepare against uncertainty and insecurity. Some military build-ups, however, are underway without the reassurance that transparency brings. National security demands are expanding. Governments need to protect their people and assets against foreign interference, cyber-attacks and terrorism. In the last few months, a new threat has emerged, with damage to critical infrastructure, like sub-sea cables. You cannot have prosperity without security, not least when the tools of commerce themselves require protection.

The third geo-economic shift is from efficiency to resilience: Where previously, Indo-Pacific economies saw ever deeper interdependence as a dynamo for growth, that can no longer be assumed in an age of decoupling. On-shoring, protectionism and trade wars are displacing best price, open markets and integrated supply chains. And so we find ourselves in a world that is growing more difficult and more complex, especially for smaller states. However, we must engage with the world as it is, not as we wish it to be. So, like most countries across the region, New Zealand’s strategic policy is being shaped by our assessment of these trends. We have agency to shape the Indo-Pacific that we want, but we must do so with energy and with urgency.

As New Zealand looks to protect and advance our interests in the Indo-Pacific region, we can only do so alongside partners. Partners like India that have a significant role to play in the Indo-Pacific. In an increasingly multipolar world, India’s size and geo-strategic heft gives you autonomy. At the same time, your democratic partners in the Indo-Pacific offer you a force multiplier for our convergent interests. For at a time when democracy is in decline with less than half the world’s adults electing their leaders, it is an inspiration that 650 million Indians turned out to vote last year in the largest election in history. Your national election is a triumph of logistics and a triumph of legitimacy. An election that means your leaders serve their people, rather than your people serving their leaders.

Now, I do not advocate arbitrary divisions between democracies and autocracies. And just because we are democracies, we will not always see eye-to-eye. Nonetheless, there is truth in the fact that our democratic governance means we share a belief in the freedom to choose, giving everyone a voice and respect for the rules. Our interests increasingly converge around seeing these three ideas as an aligned set of organising principles for our Indo-Pacific region.

Sovereignty respect

First, we want to live in an Indo-Pacific region where countries are free to choose their own path free from interference. A region where no one country comes to dominate. It is a sign of the times that I stand here defending respect for sovereignty. Yet, New Zealand’s approach is increasingly shaped around that objective. On 15 March, I joined a call led by Prime Minister Keir Starmer focused on what more those contributing to Ukraine’s defence can do to support a just and lasting peace. To help a country whose sovereignty and territorial integrity has been so flagrantly attacked.

In my home region, our fellow Pacific neighbours are navigating geo-strategic dynamics that are their sharpest in nearly 80 years. In a deeply contested world, Pacific partners are being asked to make choices that may undermine their national sovereignty. They risk falling into over-indebtedness, they must make choices about dual-use infrastructure and they face pres- sure to enter new security arrangements.

New Zealand invests in working alongside Pacific countries to boost their capacity to make independent choices free from interference. Yet, size alone cannot inoculate a country from these dynamics. Building strong and diversified relationships is the key to mitigating the risks of dependence on a few. That is why my government is investing in our key relationships, from traditional partners to thickening and deepening our relationships across South-east Asia, and in a serious way with India, too.

And we have a responsibility to invest in our own security as a down-payment on our future ability to choose our own path. That is why New Zealand will be scaling up and doing more to support our own defence. We plan to better resource and equip the New Zealand Defence Force to ensure we can continue to defend our interests, whether in our near region, in our alliance with Australia or in support of collective security efforts with partners like India. Alongside this investment in capability, we are making tangible contributions across the Indo-Pacific region. When I was in Japan last year, I saw first-hand the work our aviators do to detect and deter North Korea’s sanctions-busting activities.

The Royal New Zealand Navy is leading Combined Task Force 150 responsible for multinational activities to protect trade routes and counter smuggling, piracy and terrorism in the Indian Ocean and Gulf of Aden. We are fortunate indeed that India has agreed to take up the deputy command. Underlining these naval connections, one of our frigates, HMNZS Te Kaha, visited Mumbai in March. As we seek an Indo-Pacific region in which countries are free to choose their own path, I am determined New Zealand plays its role—whether through our work with Pacific Islands partners, our relationships in the Indo-Pacific region or through our defence efforts.

Second principle

A second principle both India and New Zealand subscribe to is the criticality of Indo-Pacific regional institutions, even as these evolve. Regional architecture scaffolds our region’s security and its prosperity. ASEAN continues to promote regional peace and economic development. Through its convening power and its centrality, it also provides a place for the region’s players to come together to discuss strategic issues.

ASEAN sits at the centre of the East Asia Summit, which for twenty years now has enabled political dialogue across the region, a forum that builds understanding, reduces the risk of miscalculation and contributes to strategic trust. Yet, the IndoPacific architecture is not static as it adapts to new realities. Mini-lateral groupings are important new pieces of the puzzle.

The Quad has emerged as an important vehicle promoting an open, stable and prosperous Indo-Pacific region. India’s contribution to that evolution has of course been vital. While New Zealand has no pretensions to Quad membership, we stand ready to work with you to advance Quad initiatives. We ourselves are strengthening our work with Japan and the Republic of Korea, as well as Australia. Last year, I convened the Indo-Pacific Four to discuss Ukraine and North Korea. And with serious headwinds buffeting the global trade system, New Zealand is seriously invested in Indo-Pacific trade and economic integration groupings. From the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement on Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), the gold standard of free trade agreements internationally, to the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), perhaps the world’s most inclusive. And we welcome India’s engage- ment in the regional economic architecture, with our work together in the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF), important in an era in which we seek to build one another’s resilience.

Subrahmanyam Jaishankar

The third Indo-Pacific principle we align around is a region in which respect for the rules is foundational. Globally, rules are being undermined: whether those around territorial integrity, freedom of navigation or laws of war. Yet, these are the very rules that preserve an Indo-Pacific order that is not ‘might is right’ alone. And, as I have stated above, there is no prosperity without security. The rules that underpin our security also allow our businesses to operate with certainty. Those rules deliver daily in meaningful ways for our people. For example, one in four jobs in New Zealand rely on exports and our exporting businesses being able to depend on the predictability that those rules deliver. And in a miracle that is only possible thanks to globally-accepted aviation standards, 120,000 flights carry 12 million passengers and operate safely between their destinations every day.

These rules shape the character of our region. We remain committed to this rules-based system, even while acknowledging its shortcomings. It is a truism that the world of 2025 is vastly different from that of 1945, and yet global institutions sadly have been slow to adapt. We are not talking about ‘starting over’ by remaking the global order. Instead, I tend to agree with Dr Jaishankar when he says we want an order in which change is evolutionary — at a pace that is comfortable and steady. That is why New Zealand supports reforming global governance frameworks to better reflect today’s realities. Rather than casting them aside, they should give greater voice to the developing world and under-represented regions. Countries like India — that play such a central role in the global community — should have a seat at the table. We have, therefore, long supported India having a permanent seat on a reformed UN Security Council.

Stark picture

The geo-strategic picture I have painted is stark. Rules are giving way to power; economics to security; and efficiency to resilience. The tectonic shifts unfolding highlight that we — working alongside partners and friends — must navigate disruption, uncertainty and sharpening pressure on our national interests. Yet, we will not be overwhelmed by complexity and challenge. We must go forward with confidence.

We live at the heart of the world’s most exciting and dynamic region — the Indo-Pacific. We live in an era of technological transformation that offers outsized opportunities. We are countries with solid underlying democratic institutions, which will underpin our societies’ future success. India and New Zealand have extraordinarily talented people. Both our countries have a clear plan that reflects and reinforces the connections between our security and prosperity. We cannot afford to be thrown by the rapid pace of change — we must grapple with shifting realities and capitalise on these for all our peoples’ benefit. We will create and seize opportunities. Invest in our capabilities. This is our region. Its future will be shaped by the choices we make — together.

Rt Hon Christopher Luxon MP is the prime minister of New Zealand. This article is the edited text of part of an address he gave at the opening of the Raisina Dialogue 2025: Kālachakria — People, Peace and Planet in New Delhi on 17 March.