10 minute read

Towards a new Chinese–Russian economic deal

Dmitry Shlapentokh

reflects on the outcome of recent discussions in Moscow.

During economic co-operation talks between Chinese and Russian officials last August, the use of barter in trade between their two countries was discussed. Traditionally seen as an attribute of primitive or under-developed societies lacking division of labour, barter represents an important step for China in the path of extricating it from the dollar-dominated world economy. As Western sanctions increase their pressure, continuing attempts to stop Chinese exports, as well as the general instability of Western capitalism, have induced the Chinese elite to search for alternatives. Barter cannot be traced and is out of control of the US financial institutions and Washington in general.

In August 2024 Chinese officials visited Russia where, among other things, they discussed economic co-operation between the two countries. The topics included increased Chinese investment in the Russian Far East, but of greatest note was discussion about the use of barter in mutual trade. This approach is important, not just for Russia but also for China because it might herald a transformation of Chinese society. Or at least it might provide an additional incentive for an already underway process — the slow departure from dollars and trade with the West as the major engine of economic development.

Barter is traditionally seen as an attribute of primitive or under-developed societies lacking division of labour. In Europe it prevailed during the early Middle Ages, when the economy was based on self-sufficiency. In these societies each segment, such as local village or peasant household, provided themselves with all that was needed for their existence. Barter also emerged in the event of economic/political breakdown at the time, when money lost its value. In all these cases, barter trade is seen as either a symbol of a peculiar disease or extraordinary situation or symbol of economic retardation.

These visions of barter are just a sign of a Western-centric and, in a way, Euclidian vision of the social/political and economic universe. In certain situations, barter could well protect the interests of the parties involved and play an important role in cementing geopolitical and economic alliances. In the case of China today, barter is an important step in the path of extricating it from the dollar-dominated world economy and, clearly, US domination. The attempt to use barter, together with crypto currencies and native yuan, will be placed in the context of the general dynamic of Chinese society in the last 40 to 50 years.

Changing relationship

Following the Deng Xiaoping reforms in the aftermath of Mao Zedong’s death in 1976, China became open to the West, particularly the United States. The country attracted considerable investments and enriched itself by trade. Western companies, including American, were lured to China by the promise of cheap, disciplined labour and ability to sell Chinese products in the West. The trademark ‘Made in China’ became ubiquitous in the United States. Some observers noted that the US companies were attracted to China by its seemingly bottomless market.

Even so, that is only a part of the story. For American companies and even more so Chinese companies, the US market also looked bottomless. And payments were drowned in US dollars, which seemed to be a stable currency with worldwide circulation. A considerable amount of them were invested in US debt, the famous Treasury bill, which had the reputation of being the most secure debt obligation, also easily sold. The reliance on foreign trade and use of the dollar as the major means of exchange sat alongside social-economic changes in post-Mao China. To be sure, the Chinese Communist Party/state maintains full control over the political/social life of society, pitilessly crushing any open revolt. The state also controls the ‘command heights of economy’, the major ‘means of production’. Still, private business was encouraged, and Deng proclaimed that to be ‘rich is glorious’. Today, the situation has undergone a visible change.

Notable shift

There have been several subterranean changes that people in Beijing have undoubtedly observed. It might be noted here that China’s millennia-long, self-centred culture prevents the people from being overwhelmed by American discourse and from accepting everything that the American elite proclaims without critical assessment. Wang Huning is a good example here. His book America against America (1991) was conceived in 1988, when he was an exchange scholar in the United States. He later became a member of the Chinese Communist Party Secretariat and Politburo Standing Committee, the highest Party body. In taking a critical view of the United States, he differed from scores of Soviet and East European intellectuals who were mesmerised by any utterance by members of the American political and intellectual elite. And the Chinese elite vision of American society has also been critical and undeceived by US propaganda.

The point here is that the US economy has been declining for the last 50 to 60 years. This is manifested not just in massive and apparently irreversible de-industrialisation, but also in rising national debt as well as persistent inflation, which is much higher than the official 2 per cent per annum. As a result, American consumers became relatively much poorer than they were a few decades ago. Stories about unaffordable healthcare and education have been circulating for a long time. Lately, observers have concluded that housing, even rented, especially in big cities, has become increasingly out of reach of the lower middle class. In fact, the problems go much deeper. And an announcement by Kamala Harris, the Democratic Party’s presidential candidate, is instructive. She stated that in the event of her election she would freeze food prices. This statement indicated that the price of this necessity has emerged as a problem not just for the poor, those who live on public assistance, but even for the lower middle class. The conclusion is clear: the United States is becoming poorer, not richer. In addition, the stock market could be a huge bubble, likely to burst for a variety of reasons. Second, the US Treasury bills and money deposited in US and indeed most Western banks are not safe. Obligations could be ignored, and money taken. And there are other signs of dramatic change.

The notion that private property was ‘sacred’ was the very foundation of capitalist society. It was made clear by none other than Karl Marx, the founder of modern socialism and, officially, the guiding light of present-day China, regardless of all Chinese specificities. And in the 19th century Marx was right. Private property was indeed sacred and political affiliation had no bearing on the rights of proprietors. An anecdote might be instructive here. It relates to the life of Alexander Herzen, the founder of Russian socialism. Escaping the wrath of Tsar Nicholas I, the harsh Russian ruler, Herzen emigrated to France, doing so without state permission. A wealthy man, he left behind a considerable estate and naturally wanted to retrieve his money. Herzen solicited the help of James de Rothschild, a member of the famous banking family. Rothschild promised to help, presumably for a fee. When he approached the tsar and asked why his client could not have his money, Nicholas responded that the reason was obvious: Herzen was a political dissident. As Herzen noted with an air of irony in his memoir, this answer quite surprised Rothschild. In his view, there were only two reasons for not giving a person his own money — failure to pay taxes or repay loans. Responding to the tsar’s answer, Rothschild suggested that ‘his majesty’ was possibly aware of his role in the European banking system and that if Herzen did not receive his money ‘his majesty’ would not be able to borrow anything from European banks. Nicholas surrendered: the money was released.

Enduring principles

These principles apparently worked through most of European history, at least in the countries which regarded themselves as capitalist. Not so today. Property is not ‘sacred’ and its position depends on the political standing of the owner. Money will be returned to ‘good’ people but not ‘bad’, and it is Washington and Brussels that decide who is ‘bad’ or ‘good’. Recently, the West ‘froze’, or practically confiscated, $300 billion of Russia’s sovereign funds. And who would vouch for the safety of the money of other ‘bad’ chaps? China clearly is one of them. Who also could vouch that Washington would never attempt to ‘solve’ debt problems through a dollar devaluation? Europe might be little better, but not dramatically. Sanctions and embargoes on Chinese goods add to all the above-mentioned problems and underpin changes in Chinese planning.

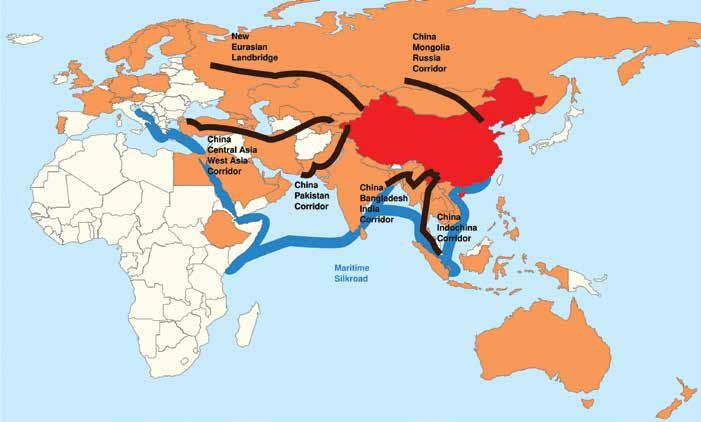

An economy oriented to just Western markets is clearly fraught with problems. In addition, the increasing number of quite wealthy individuals who benefit from market arrangements and erosion of state control over ‘means of production’ is undermining the foundations of the CCP regime. Responding to the challenge, President Xi Jinping has increased Party/state control over private business. Increasing pressure on the economy and a peculiar Stalinist reaction, in its idiosyncratic Chinese version, are also quite possible. In any case, an element of economic/industrial and technological autarky is essential. Dollardenominated US Treasury bills are also losing their dominant position, increasingly overshadowed by gold. These changes will also have implications for China’s foreign policy. The Belt and Road Initiative continues to expand with an attempt being made to connect with the European market. But increasingly, there is a search for alternatives in other markets where the dollar/euro could be, if not ditched completely, less dominant. Russia is one of the countries.

The Russo-Ukraine War finally released China from the lingering fear of Russia siding with the West. While moving closer to Moscow, mostly for geopolitical reasons, Beijing is not willing to ditch dollars completely. The process of disengagement will be as smooth as possible. For all of its problems with the United States and West in general, China does not want to end engagement, abruptly severing ties. Such a catastrophic scenario is hardly in Beijing’s interest. Consequently, many Chinese banks are not happy in dealing with Russia banks, especially in dollars, because of the threat of Western, mostly American, sanctions. This is leading some Russian observers to complain that China is not a true ally or that the pro-Western part of the Chinese elite is preventing Beijing from fully embracing Russia.

Alternatives search

Even so, as Western sanctions increase their pressure, continuing attempts to stop Chinese exports, as well as the general instability of Western capitalism, have induced the Chinese elite to search for alternatives. Beijing is increasing efforts to be less dependent on both Western markets and especially Western banking systems. And dealing with Russia could be a good option. Because its own options are quite limited, Moscow is desperate for trade with China. It would most likely prefer trade in dollars/euro, but also accepts yuan as an alternative. In fact, most Russian trade with China, where money is used, is conducted in yuan or rubles.

Bank transactions can be traced and those engaged in trade with Russia could be sanctioned. In this light, barter emerges as the most viable solution. It cannot be traced and is out of control of the US financial institutions and Washington in general. Barter is still a small fraction of China’s overall trade. Nonetheless, it might be a sign, together, of course, with other steps, of China slowly decoupling, at least partially, from the old domination of Western-oriented trade and market-oriented trends of the previous decade. It remains to be seen whether it will be the way China distances itself from the dangers that might derive from cataclysmic events in the West.

Ukrainian-born Dr Dmitry Shlapentokh is an associate professor in Indiana University South Bend’s Department of History.