19 minute read

Rules and power

Malcolm McKinnon places New Zealand foreign policy in historical context.

There is much contemporary comment about the shift that has taken place in global affairs from rules to power. The contrast is applied here to a three-fold historical analysis of New Zealand’s foreign policy: its relations with Britain, the United States and their allies — a world of rules; its relations with rivals to Britain and the United States — a world of power; and its relations with the world of the erstwhile European empires, the British Empire most prominent among them — also a world of power. The on-going relevance of the analysis, including in respect of New Zealand’s foreign policy towards its regional neighbourhood, is considered.

In the strategic foreign policy assessment Navigating a Shifting World Te Whakatere i tētahi ao hurihuri, which it released in 2023, New Zealand’s Ministry for Foreign Affairs and Trade drew attention to a challenging global shift from ‘rules to power’.1 This essay applies this approach retrospectively to the history of New Zealand foreign policy, using a three-strand analysis rooted in that history but still relevant.

The first strand arises from the relations of a self-governing colony, later dominion, in the British Empire, later Commonwealth — a domain of rules, with power masked or tamed. The empire has long gone, but this facet of it remained in a succession of iterations, notably the mid-20th century Anglo-American alliance. Contemporary terminology ranges from the ambiguous ‘like-minded’ and the dubious ‘Anglosphere’ to the more specific ‘Five Eyes’ (the United States, Canada, United Kingdom, Australia and New Zealand) and to the ‘West’, usually including Europe and Japan.

The second strand is a by-product of Britain’s relations and conflicts with other great powers. The Cold War saw conflict reconfigured as one between the US-led Western alliance, of which Britain and New Zealand were part, and a communist bloc led by the Soviet Union and China. A contemporary contest pits the West against China and Russia.

The third strand is a by-product of the British Empire’s rule (and at one remove the rule of other empires) over non-selfgoverning territories — which included Māori Aotearoa until its autonomy was suppressed in the 1860s. Decolonisation in the mid-20th century dramatically changed this world. In its contemporary form, the strand takes in relations with an array of excolonial states across three continents and oceans, identified in the post-colonial decades as the ‘Third World’ and in the 2020s as the Global South.

In both these latter strands power is more visible, with rules occasionally masking or taming it. ‘By-product’ indicates that historically both played out at one remove from New Zealand’s immediate preoccupations.

In the rest of this essay these two strands will mostly be referred to in shorthand as relations with the second and third worlds. The terminology is unsatisfactory but so is varying it from decade to decade.

1945-2010: The Second World War is a useful starting point for closer analysis. It ended in an Allied victory over the Axis powers, indeed in ‘unconditional surrender’, in 1945. Would this allow a world of rules to replace worlds of power? The United Nations, like its ill-fated predecessor the League of Nations, was intended to accomplish that and was vigorously supported by New Zealand, which saw the United Nations as an enlarged version of British Commonwealth relations, to that end.2

Two developments

Two developments, the Cold War and decolonisation, provided sharp reminders of the existence of second and third worlds.

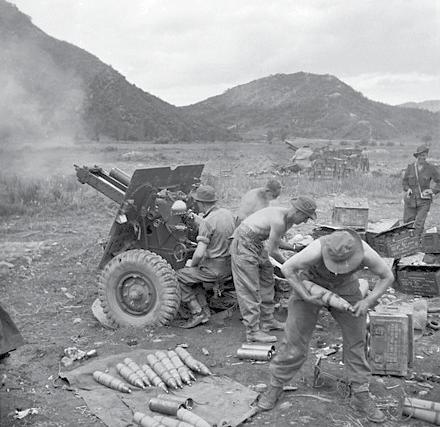

The onset of the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union shattered the ambition of a rules-based order based on a great power condominium. An ‘iron curtain’ divided Europe. Across the expanse of the Pacific, US hegemony was uncontested. But communist victory in the Chinese Civil War in 1949 ended US influence on most of the Asian mainland. US strongpoints in Japan, Okinawa and further south confronted the Soviet Union, Communist China, North Korea and North Vietnam. New Zealand engaged with this contest at one remove, its deployments in Korea and Vietnam being made alongside the forces of the United States and its allies.

For its part, decolonisation challenged the assumption of the European UN member states — Britain, France, the Netherlands, Belgium and Portugal — that they would keep their empires. The newly independent states varied in the extent to which they sought a rupture with their erstwhile rulers but were unanimous on certain issues, notably the future of Palestine and the fate of white rule in southern Africa.

New Zealand was engaged in two phases — the British Confrontation with Indonesia over Malaysia, and the challenge to white-rule in southern Africa. Indonesia retreated but survived, white rule in South Africa did not. Power had shifted from European overlords to locals.

From the 1970s to 1990: These two worlds — the communist second and the ex-colonial third — abutted more directly on New Zealand in the 1970s than before.

Third World calls for a new international economic order and for an end to white rule in southern Africa were more than matched by the impact of successive Middle East crises and consequential oil shocks, which dramatically altered the balance of economic power between the region’s main oil producer states, on the one hand, and the United States and its oil-consuming partners, on the other.

Conversely, the United States’ embrace of détente introduced a view of great power relations, not free of power but in which rules were delimited. This culminated in Europe in the Helsinki Accords of 1975 and in Asia with the US recognition of Communist China, and adoption of a one-China policy, in 1979.

Unpredictable mix

Coupled with New Zealand’s need to economically diversify in the wake of Britain’s approach and eventual entry into the European Economic Community, these developments prompted New Zealand into direct dealings with countries beyond its traditional partners in the British Commonwealth and the United States (and newer partners in Western Europe and Japan). These dealings were governed by an unpredictable mix of rules and power.

New Zealand did business with the oil rich Middle East, the Soviet Union and China, and the burgeoning capitalist econo- mies of East Asia. Such efforts gave point to then Prime Minister Robert Muldoon’s claim that ‘New Zealand’s foreign policy is trade’. As did the suppression in New Zealand of the documentary Death of a [Saudi] Princess, and the reluctance to forego trade ties with Iran and the Soviet Union in the face of crises in both countries’ relations with the United States.³

The anti-nuclear breach between the United States and New Zealand in the mid-1980s introduced New Zealand to the exercise of power in the domain — of allies and friends — where rules were the norm. But the confrontation was limited, a limitation captured neatly in the opinion polling of the time which revealed that most New Zealanders both supported the ANZUS alliance and the antinuclear policy.

The 1990s and 2000s: The 1990s transformed relations with the second and third worlds yet again.

Communist regimes collapsed in Europe. China had embarked on economic liberalisation in 1978. The two Koreas joined the United Nations in 1991 and committed to peaceful reunification.

The post-Second World War wave of decolonisation ended with the dismantling of South Africa’s apartheid regime. But equally, with oil prices falling and India and other developing states embarking on economic liberalisation, the days of radical challenges seemed over.

For New Zealand the most important transformation was regional. APEC (‘Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation’) was established, a grouping of fast-growing economies led by Japan. Over the next decade a dense mesh of rules-based economic and security ties embraced not just the United States and its long-standing partners in the region — Japan, Australia, New Zealand and South Korea — but the (mostly newly independent) countries of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and Communist China. Thus connecting parts of the West, the second and the third worlds.

Since 2010: As after the Second World War, it became evident that longstanding fracture lines in world politics had not vanished. In the 2010s and 2020s they returned, and a threestrand analysis of New Zealand foreign policy remained relevant.

New competitions

For the Third World, the notion of rules replacing power had always depended on where you stood. The United States’ rift with the Islamic Republic of Iran was never overcome and Iraq’s Saddam Hussein was overthrown by a US-led coalition in 2003. Meanwhile radical Islamist forces mobilised. Combined, both led to years of US-led or overseen governance in the region alongside on-going support for Israel.

A different Third World development was the rise of the BRICS — a highly instrumental association of four, then five countries — India, South Africa and Brazil along with China and Russia — which did not so much seek to upturn the Western-led global economic order as to gain a greater say in setting its rules.

The world of rival great powers also returned. Russia’s ‘wild East’ 1990s was prelude not to ever-closer entanglement in a Western rules-based order but to a disillusionment with it exploited by Vladimir Putin, whose leadership has spanned the 21st century to date.

Even more important for New Zealand was the economic and political trajectory of mainland China. ‘Peak Japan’ proved to be 1989, when Japan’s economy was many times the size of China’s; by 2010, in an astonishing development, the rankings had reversed. The government in Beijing had concepts of world order which differed sharply from those in the West in many specifics. It also saw itself as a legatee of the unfinished business of the Chinese Civil War, and a determined aspirant to at least regional hegemony, to which the United States still barred the way as it had in 1949.

A world at war?: Studies with titles such as America, China and the struggle for world order have been published for a decade or more. In the mid-2020s the narrative of a global US contest with China, the latter supported variously by Russia, North Korea and Iran, has become a commonplace.⁴

In regional diplomacy the talk is of the Quad, AUKUS, tripartite solidarity among the United States, South Korea and Japan, speculation on when (not if) war will break out in the Taiwan Strait and initiatives on combating Chinese manoeuvring in the China Seas and among the Pacific Islands states.⁵

Watching brief

NATO, historically a European Cold War alliance, has assumed a watching brief in the region, and at its 75th anniversary summit in July criticised China for its support of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. New Zealand is training Ukrainian soldiers in the United Kingdom, and has supported US–UK Red Sea operations against the Iran-supported Houthi in Yemen.

New Zealand has embarked on a liaison with the US Space Force, which is strongly talking up the threat of China under the hashtag ‘#FightIsOn’ and the slogan ‘the threat is real’.6 There is discussion — and controversy — about New Zealand participating in Pillar 2 of AUKUS.7

The language of New Zealand foreign policy, reflecting shifts not just from ‘rules to power’ but from ‘economy to security’ and ‘efficiency to resilience’, is also indicative.⁸ Five Eyes collaboration is increasingly prominent.⁹

The SIS has reported on foreign power interference in New Zealand domestic affairs.10 A language of friends and enemies, of espionage and undercover activities has become widespread. Critical statements about breaches of human rights abuses in putative adversaries, notably China, have become routine.

Echoes from world wars and the Cold War make familiar the notion of a liberal New Zealand aligned politically and militarily with like-minded states and at odds with predatory rivals and authoritarian rulers.11

Such rhetoric may also thrive for ‘legacy’ reasons. Sixtyfive per cent of a recent sample of New Zealanders thought the United Kingdom ‘important’ or ‘very important’ to New Zealand’s future.12 Retropolitics buttresses geopolitics.

Different analysis

As during the Cold War, such a focus on a global struggle between two blocs, one observing rules, the other exercising power, can blur thinking about other ways of engaging with the ‘second’ and ‘third’ worlds (the latter now usually referred to as the Global South).

The brittle decade, the 1970s, provides a better guide (if not much reassurance) than any other. That is because it was a decade in which the intersection of rules and power was complex, as in the 2020s.

New Zealand and the great power contest: Accepting the reality of a great power contest does not mean there is only one possible position on it. The Second World War demand for the ‘unconditional surrender’ of the enemy will always sound heroic. The most fleeting reflection suggests that even the notion of regime change is implausible and unrealistic, especially with respect to Beijing. Yet there are advocates.13

The quandary, if such it is, does not arise so acutely over New Zealand’s support for Ukraine, in part because ties with Russia have never been extensive, in part because the outcome of that conflict lies largely in the hands of the combatants and of NATO.14

In respect of China, matters are different, given its greater importance to both New Zealand and the United States. That said, there are nuances. In a recent interview, the American ambassador to China, Nicholas Burns, explained that the United

States had to ‘manage this relationship in such a way that we defend American national interests but avoid a conflict at the same time’.15 That is a commitment to détente — though the term is no longer favoured — and to setting rules of engagement.

Such restraint should suit New Zealand, which cannot benefit from the outbreak of war between China and the United States, not only because it would be economically catastrophic and immensely destructive, but because in consequence it is unlikely to advance the ethical or humanitarian objectives which many China critics focus on.

New Zealand and the Global South: Navigating a shifting world refers to a ‘diverse range of partners, across the IndoPacific, Europe, the Middle East and Latin America’. Pacific Islands countries, small island developing states and ASEAN are also instanced.

The notion of a single global contest between rules and power, rights and might does not provide guidance for New Zealand on the Israel–Hamas conflict, nor on other rivalries among regional powers in the Middle East. It does not provide guidance for dealing with the crisis in Myanmar, with democratic but powerful and assertive states such as India and Indonesia or with the wealthy absolute monarchies of the Gulf.

Different situation

Something rather different goes for the Pacific, where power favours New Zealand rather than its Pacific Islands neighbours. The challenge for New Zealand is to pursue policies where rules, for example on military activities, climate change, migrant labour and trade, bind all powers and New Zealand as much as those neighbours.16

New Zealand can use multilateral diplomacy to engage with the states in the Global South in ways which promote its own interests and values and connect with those states’ approaches to the global disposition of rules and power.

New Zealand activism on nuclear disarmament and indeed disarmament in general is shared with many such countries. Conflict resolution can also be common ground.17 So also support for debt relief. On this latter, the Third World quest for a ‘New International Economic Order’ in the 1970s and 1980s was promoted by then New Zealand Prime Min- ister Robert Muldoon. ‘To those used to… treating international relations as a zero-sum battle between democracy and authoritarianism’, wrote two observers earlier this year, ‘it can be hard to conceive that… today as in 1974, the fulcrum of geopolitics is the… struggle to right systemic inequities, between what are now typically called the global north and global south.’18

New Zealand and the West: Relations with Western states are the most rules-based of the three strands, but in a time of geopolitical competition, the pressure to conform, to ‘pay one’s dues’, is ramped up.

That said, this is the strand in which a practice of disagreement over interests and values, of ‘independence’, is long-established, most apt, most legitimate and most readily expressed. Given that New Zealand is formally allied to only one country, Australia, the opportunity to disagree, to think independently, should thrive. Norway, a NATO member, is renowned for its peace activism; surely New Zealand, neither in NATO nor any comparable alliance, can question directions which its ally and its close partners take in world affairs.

Such efforts need not or should not mean a complete break. In the post-Cold War environment, former New Zealand diplomat Bryce Harland published On our own: New Zealand in the emerging tripolar world 19 Harland’s tripolarity was the United States, Europe and Japan — a reminder of how much the world can change in a generation. But the finding endures — a small relatively isolated state can lose friends more easily than gain them, and global rules will not always compensate. A New Zealand withdrawal from say Five Eyes intelligence collaboration could mean forgoing a diplomatic asset for uncertain result.

Salient limitation

New Zealand and Pacific Asia: The limitation for New Zealand of a binary and polarised approach to world affairs is most salient in respect of its home region which, to avoid arbitrating between ‘Indo-Pacific’ and ‘Asia–Pacific’, is here labelled ‘Pacific Asia’ (the Indian Ocean may be proximate for Australia but hardly for New Zealand).

Pacific Asia is the geographic locus of the contest between the United States and China, home to close partners Australia and Japan and home to ASEAN. The three strands of New Zealand foreign policy still meet in the region.

South-east Asian countries do not wish to choose between China and the United States. Even the alignment of US allies Japan and South Korea can be qualified. Japan’s public remains divided over amending the war-renouncing Article 9 of the country’s Constitution.20 For South Korea a key variable will always be its wish to engage with China on North Korea.

Singapore Defence Minister Ng Eng Hen would have spoken for many in the region when he argued that ‘all of us should be very, very careful to avoid any physical conflict for at least this decade, if not for longer, because discovery will be very painful and will probably be life-changing.’21

No region in the world is more important to New Zealand. For New Zealand the objective is surely continued support for the ‘rules of regional order’ which were laid down in the 1990s and 2000s, even if they are under extreme stress. To keep open lines of communication with China and the United States, to maintain close relations with Australia, Japan and South Korea and to invest in relations with ASEAN and in the myriad dimensions of ASEAN centrality, including the East Asian Summit.

APEC’s annual meeting, set for 10–24 November in Lima, Peru, at which both the United States and China, as well as the nineteen other member ‘economies’, one of which is Taiwan, will be present, is another opportunity to focus on commonalities, to sustain the rules that constrain power across the many facets of regional relations.

Dr Malcolm McKinnon is on the NZIR’s Editorial Committee. He is the author, among other works, of Independence and Foreign Policy: New Zealand in the world since 1935 (Auckland University Press, 1993).

Notes

1. Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade Strategic Assessment 2023: Navigating a Shifting World, pp.6, 18–21.

2. On the British Commonwealth origins of the United Nations, see Mark Mazower, No Enchanted Palace: the End of Empire and the Origins of the United Nations (Princeton, 2013).

3. Malcolm McKinnon, Independence and Foreign Policy: New Zealand in the world since 1935 (Auckland, 1993), pp.201–4, 219–22.

4. See, eg, Andrea Kendall-Taylor and Richard Fontaine, ‘The Axis of Upheaval, How America’s Adversaries Are Uniting to Overturn the Global Order’, Foreign Affairs, May–June 2024 (www.foreignaffairs. com/china/axis-upheaval-russia-iran-north-korea-taylor-fontaine).

5. Minister of Defence, 28 Aug 2024 (www.beehive.govt.nz).

6. RNZ, Phil Pennington, 7 Aug 2024 (www.rnz.co.nz/news/natio nal/524369/nz-endorses-us-push-to-expand-weapons-makingdefence-industrial-base; 24 Jun 2034 (www.rnz.co.nz/news/po litical/520385/nz-embeds-itself-in-us-space-force-which-is-talkingup-chinese-threat).

7. See, eg, The Post, Thos Manch, 10 Sep 2024 (www.thepost.co.nz/ politics/350420442/aukus-countries-confirm-consultations-newzealand-about-co-operation).

8. MFAT 2023 Strategic Assessment, Navigating a Shifting World

9 See, eg, Newshub, 12 Dec 2023 (www.newshub.co.nz/home/poli tics/2023/12/winston-peters-seeks-closer-ties-with-five-eyes-pow er).

10. The SIS report can be found at www.nzsis.govt.nz/assets/NZSISDocuments/New-Zealands-Security-Threat-Environment-2024. pdf; see also Stuff, Paula Penfold, 23 Sep 2024 (www.stuff.co.nz/ nz-news/350423709/we-dont-feel-safe-here-new-zealand-call-ur gent-inquiry-foreign-interference).

11. www.beehive.govt.nz for speeches by the prime minister (15 Aug 2024), the minister of foreign affairs (1 May 2024) and the minister of defence (28 Aug 2024) touching on this theme.

12. Asia New Zealand Foundation (www.asianz.org.nz/our-resources/ reports/new-zealanders-perceptions-of-asia-and-asian-peoples2024).

13. See, eg, Matt Pottinger and Mike Gallagher, ‘No Substitute for Victory, America’s Competition With China Must Be Won, Not Managed’, Foreign Affairs, 10 Apr 2024 (www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/ no-substitute-victory-pottinger-gallagher).

14. See further Foreign Affairs. 13 Jul 2023: ‘Should Ukraine Negotiate With Russia? The Debate Over How to End the War’, responses to Samuel Charap’s ‘An Unwinnable War’ (www.foreignaffairs.com/re sponses/should-america-push-ukraine-negotiate-russia-end-war).

15. ‘Is America’s China Policy Too Hawkish?’, Ambassador Nicholas Burns in conversation with Ravi Agrawal, Foreign Policy, 5 Sep 2024 (foreignpolicy.com/2024/09/05/us-china-policy-taiwan-sulli van-visit/).

16. For a critique of New Zealand policy, see Grant Brookes, ‘New Zealand imperialism in the Pacific’ (iso.org.nz/2024/09/24/newzealand-imperialism-in-the-pacific-in-the-21st-century/).

17. Consider, eg, Max Harris, Thomas Nash, Nina Hall and Fairlie Chappuis, Aotearoa New Zealand and Conflict Prevention: Building a Truly Independent Foreign Policy, New Zealand Alternative, Wellington, 2018 (www.nzalternative.org/nza-aotearoa-nz-and-conflictprevention-report).

18. Michael Galant and Aude Darnal, ‘Who’s Afraid of the Global South? Revisiting two 50-year-old UN resolutions should dispel fears about a shifting economic world order’, Foreign Policy, 14 Apr 2024 (for eignpolicy.com/2024/04/14/global-south-united-nations-new-inter national-economic-order). Relatedly, see Brian Easton, ‘Trading towards a multipolar world’, Pundit, 23 Aug 2024 (www.pundit. co.nz/content/trading-towards-a-multipolar-world).

19. Bryce Harland, On our own: New Zealand in the emerging tripolar world (Institute of Policy Studies, 1992). ‘On our own’ was also invoked by Foreign Minister Brian Talboys in 1981 (McKinnon, p.222).

20. Kyodo News, 2 May 2024 (english.kyodonews.net/news/2024/ 05/9b84e18c3f04-65-feel-japan-need-not-rush-to-debate-constitu tion-revisions-poll.html).

21. ‘How Singapore Manages China–U.S. Tension’, Ng Eng Hen in conversation with Ravi Agrawal, Foreign Policy, 17 Jul 2024 (foreignpolicy.com/2024/07/18/singapore-manage-u-s-china-tensions-ngeng-hen).