Benchmarking how we’re doing right now

Career pathways decline of the 50/50 sharemilker

Dairy sustainability and financial management into the future

Māori and dairy

Benchmarking how we’re doing right now

Career pathways decline of the 50/50 sharemilker

Dairy sustainability and financial management into the future

Māori and dairy

This month kicked o with World Milk Day on 1 June.

The Day was established by the United Nations to recognise the importance of milk as a global food, and to celebrate the dairy sector.

Each year, the bene ts of milk and dairy products are actively promoted around the world, including how dairy supports the livelihoods of one billion people.

Dairy farming has undergone rapid change in our country over the last decade, even while remaining a signi cant contributor to New Zealand’s growth and export earnings. But more change can still be expected.

The number of dairy cows nationally peaked in 2014/15 at over 5,000,000. That number has since dropped by about seven percent in 2022/23.

According to DairyNZ’s Dairy Statistics 2022/23, an annual census of New Zealand’s dairy herds, over 70 percent of New Zealand’s dairy herds were in the North Island in 2023, although only 3.5 percent were in Wairarapa.

That 3.5 percent was composed of nearly 143,000 cows in 367 herds, on 52,500 hectares. This equates to an average herd size of 390 (compared with an average national herd size of 441) and an average of 2.72 cows per hectare.

Of Wairarapa’s herds, the majority (67 percent) were based in Tararua and 18 percent in South Wairarapa.

About 10 percent of dairy farms are owned by Māori, often collectively owned and larger than New Zealand dairy farms in general. Māori dairy farms also hold more stock – with an average herd size of 755 in 2022 compared with the national average herd size of 491 in that year (dropping to 441 in 2023).

At the same time as a fall in the number of cows, however, production per cow and per hectare has steadily increased both nationally and in Wairarapa.

DairyNZ’s mid-season performance update (dated 4 January 2024) notes that production is up 20 percent nationally on last season. Wairarapa herd production statistics are higher than general averages – both per e ective hectare and per cow – on all metrics including average kgs of milkfat, kgs of protein, and kgs of milksolids.

According to the economic consultancy Infometrics, Wairarapa’s dairy payout for the 2022/23 season is estimated to have been about $176 million. For the 2023/24 season, the payout is expected to drop to about $168 million.

The 2022/23 season saw an average dairy cooperative payout of $9.26 per kg milksolids – the second highest payout on record before in ation is factored in (the fth highest when in ation is considered). The high payouts have helped farmers adjust to the impact of increased farm costs due to adverse weather conditions and rising input costs.

But the average payout for 2023/24 is forecast to be about ve percent less than the year before.

Dairying is an important contributor to Wairarapa’s economy.

Infometrics’ Annual Economic Pro le 2023 reports that primary industries overall contribute 5.7 to the nation’s GDP but 8.7 percent to Wairarapa’s GDP.

Dairying (farming and processing) accounted for 3.2 percent of the nation’s GDP to March 2023, according to Sense Partners’ September 2023 report Solid Foundations.

National gures: 52 percent of herds were run by owner-operators in 2022/23, down from 65.5 percent 10 years before. Over the same period, the proportion of herds run by sharemilkers reduced from 34 to 29 percent, while the proportion of contract milkers increased.

Wairarapa gures: Wairarapa shows slightly di erent trends to the national ones, with more herds run

by owner-operators in 2022/23 (59 percent), fewer run by shareholders (23 percent), and 18 percent by contract milkers.

Māori gures: Solid Foundations writes that Māori make up 16.5 percent of dairy farming employees/ self-employed, up from 12.7 percent in 2015.

Figures for women: a 2019 Ministry of Primary Industries factsheet about primary industries workforces writes that women make up two-thirds of the dairy industry’s workforce, encompassing both dairy farming and dairy processing. In dairy farming on its own, however, women make up just under 30 percent of the workforce.

The dairy sector is New Zealand’s biggest export earner. Dairy generated nearly $26 billion in export revenue for the year to April 2023, accounting for around one in every four export dollars earnt by New Zealand.

The 2022/23 season shows continued increases in breeding worth and production worth across dairy cow

breeds, re ecting an ongoing focus by farmers to improve herd e ciency and production.

DairyNZ Chief Executive Campbell Parker and Livestock Improvement Corporation Chief Executive David Chin wrote, in their annual census of New Zealand’s dairy herds:

“The number of cow herds tested [in 2022/23] was the highest on record, increasing by 2.8 percent from the previous season … The number of cows arti cially inseminated also increased to 3.81 million … [Both metrics show] that farmers are continuing to explore options to increase the productivity of their herds.

“Farmers can be proud of their contribution to rural communities as they continue to add critical value to New Zealand’s economy. The work of dairy farmers and the sector to explore new solutions for herd productivity is also signi cant and showcases our commitment to competitiveness on a global scale.”

Dairy farming is a shock absorber for regional economies such as Wairarapa, helping to maintain local spending, even when milk prices drop.

We are available to service all makes & models of tractors, balers, excavators etc, and supply parts for most brands. Our factory trained technicians will ensure your equipment is ready for the season ahead.

So give us a call and get your winter service booked in today.

In New Zealand, sharemilking has been the main career pathway into dairy farm ownership since the early 1900s – it’s been a way of learning skills and building valuable equity for dairy farmers to be able to transition in increments from stock ownership to farm ownership.

But the number of sharemilking contracts on o er has been declining for ten years. Current sharemilkers

are staying in their positions longer than previously, to be able to achieve enough equity to purchase farms. And many farm workers are losing their only opportunity to step up to sharemilking and then on to dairy farm ownership.

In part, this is because pro table farms have grown larger and have increased in value, whereas the value of herds has not increased at the same rate. This means the jump has got harder from one point on the career path to the next.

Another reason relates to changes in the nature of the farm owner/operator. More are now business entities rather than individuals, with ownership handed

down through business structures rather than being sold on.

In addition, average milk payouts, as well as returns on equity compared to milk payouts, have both uctuated wildly over the last ten years, making 50/50 shareholding less viable for both farm owners and sharemilkers.

Squeezed pro t margins (including because of increased debt and higher debt servicing costs) have made it necessary for some farm owners to adopt farming systems that can add resilience – especially in the years of high milk prices – by xing the cost of labour.

By way of de nition, herd owning sharemilkers are responsible for operating a farm on behalf of the farm owner. The sharemilker does not own the land. The income and expenses of the dairy business are split between the landowner and the sharemilker, as are the risks and rewards of low or high milk solids production and prices, often 50/50.

All of these factors have contributed to owner-operators choosing to employ contract milkers.

Fewer sharemilking opportunities and fewer pathways to farm ownership have resulted in fewer younger people showing an interest in dairy farming – not all can see it as a viable career opportunity.

Contractors, consultants, external systems, and sta sourced from overseas will become increasingly important if agricultural students within New Zealand are not taking up sharemilking roles.

“New Zealand’s dairy sector stands at the cusp of a transformative era, where sustainability takes centre stage in shaping its trajectory,” says Brett Woo ndin, a director with Lawson Avery, a rm of chartered accountants and business advisors.

“Long celebrated for its premium dairy products, the industry is undergoing a shift towards more eco-conscious practices and innovative solutions.”

He talks about how some dairy farmers across New Zealand are focusing today on sustainability in four key areas: environmental conservation, animal welfare, innovation, and diversi cation.

“By embracing these principles, they’re not just safeguarding the industry’s future but also setting a global example for responsible agriculture.”

We know that environmental conservation is a top priority. Farmers are implementing measures to minimise their ecological footprint. From adopting precision irrigation techniques to planting riparian bu ers along waterways, these e orts help preserve New Zealand’s natural beauty while mitigating environmental impacts.

Brett says “it is conceivable that farmers will be operating in a multi-tiered market in the future as the ‘ ght for quality’ evolves. Farmers who practice best industry practice are likely to command a higher premium that those who are resisting.”

This ‘ ght for quality’ is driven by global customers demanding to know more about how products are made which, in turn, is driven by the end consumer.

“Although it remains to be seen what the price premium could be and if the end consumers will be prepared to pay it. What cannot be disputed is that end consumers prefer environmentally friendly products,” Brett says.

Access to capital is another signi cant change likely to impact the future of farming. Banks are about to start reporting on their environmental impact, which will include in time their clients. This may further encourage capital expenditure on positive impacts to the environment.

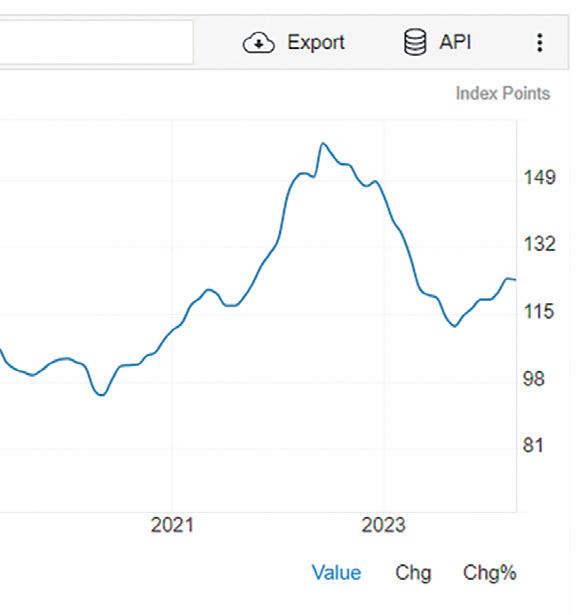

The Global Dairy Price Index fell 12.8 percent in last ten years (chart 1).

During the same period the average cost of a New Zealand dairy farm per hectare increased. For example, REINZ data shows a 56 percent increase in the sale price of Waikato dairy farms, per hectare, between 2013 to 2023 (chart 2, over page). These opposed trends cannot continue inde nitely.

CONTINUED OVER THE PAGE

On the other hand, dairy farm debt levels are far more sustainable than they were ten to fteen years ago. Brett points out that, currently, “only about six percent of loans in the sector are non-performing compared to over 20 percent in 2010” (chart 3).

Data from farm software provider Figured, one of several farm softwares

on the market, shows the average dairy farm will pay $1.73 in interest per kgm in 2024 year, compared to $0.88 in 2022. With other farm costs also increasing, the margin has been squeezed. A drop in milk price could create uneconomic reality for some farms.

Local data from Lawson Avery Ltd shows their local dairy farmer client base interest increased from $0.39 kgm in 2021 to $0.82 in 2023 – a 110 percent increase. Over the same time,

DAIRYAgriculture excluding dairy

Source: Private reporting, RBNZ bank balance sheet survey.

Note: Non-performing loans includes loans classi ed as 90+ days past due or impaired. Potentially stressed loans includes loans that banks have assigned internal credit rating grades

(Moody’s) or lower, but which are not non-performing.

average local farmer operating costs increased from $4.08 per kgm to $6.11 – a 50 percent increase.

“For farmers, knowing where they are and where they are heading is going to be essential for nancial management in the future. Financial planning is a skill farmers will need to add to their repertoire or, at least, they will need a team assisting them with that,” Brett says.

or

Challenges persist, but the future of dairy farming in New Zealand is focused on sustainability, innovation, and resilience. By embracing these principles, the industry is poised for continued success, enriching communities, preserving the environment, and delivering premium dairy products to consumers worldwide.

For farmers, knowing where they are and where they are heading is going to be essential for nancial management in the future.

Wairarapa Moana Ki Pouākani won 2024’s top Māori farming award - the Ahuwhenua Trophy – in May this year. It was recognised as delivering the best in Māori dairy farming including improved water quality and a carbon footprint that had reduced by 30 percent.

Wairarapa Moana originally owned valuable land and shing rights in the southern Wairarapa but, by the late 1800s, pressure from farmer settlers and Crown coercion ultimately forced Wairarapa Moana o its land. In 1915, it reluctantly accepted land at Mangakino (Waikato) composed of 12 farms.

Wairarapa Moana represents shareholders and descendants of the original owners of Wairarapa Moana. Wairarapa Moana ki Pouākani Incorporation was formed in 2002 and trades as Wairarapa Moana Incorporation. Large dairy farms are part of its rural portfolio.

Wairarapa Moana ki Pouākani is a strong example of Māori dairy farming excellence. “It’s about building economic

bene ts while ensuring kaitiakitanga – active guardianship and nurturing its whenua for future generations and inspiring others.”

The businesses values of Wairarapa Moana are integrity, communication, courage, knowledge, and working together. Its aims are to protect and enhance its assets, be an industry leader, grow beyond its current assets, pay dividends, and foster shareholder pride.

Māori dairy processing

The Māori-owned milk processing company Miraka relies on its kaitiakitanga business model to keep up payouts to its supplier farmers. Miraka produces over 300 million litres of milk per year and exports its products around the world. In August of last year, Miraka paid 15.4 cents a kilogram more than Fonterra for milksolids.

Miraka was established in 2010 by a small group of Māori trusts and incorporations and was founded on a te ao Māori worldview that places kaitiakitanga - the care of the land, people, and the environment - at the heart of the business. Farmers are nancially incentivised to strive for excellence in animal welfare and onfarm sustainability.

Key concerns include how to improve water quality and biodiversity on-farm, and how to minimise nitrate usage. Another issue is how to ensure farm workers are trained and invested to grow with the business.

Miraka is based on a kaitiaki-driven philosophy designed to encourage Māori farmers to reinvest back into their whenua and their herd, and to take an inter-generational approach.

Miraka is the world’s rst dairy processing company to use renewable geothermal energy and has one of the lowest global manufacturing carbon emissions footprints.