THE JOURNAL

of the New York State Nurses Association

VOLUME 49, NUMBER 1

n Editorial: Ordinary Essential by Anne Bové, MSN, RN-BC, CCRN, ANP; Audrey Graham-O’Gilvie, DNP, RN, ACNS-BC, CCRN-k; Meredith King-Jensen, PhD, MSN, RN; Alsacia L. Sepulveda-Pacsi, PhD, DNS, RN, FNP, CCRN, CEN; and Coreen Simmons, PhD-c, DNP, MSN, MPH, RN

n Breastfeeding Disparities Among Communities Lacking Access to Lactation Consultants During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Theory-Guided Paper by Cynthia Flynn, BA, RN, IBCLC and Audrey Graham-O’Gilvie, DNP, RN, ACNS-C, CCRN-k

n Venting the Truth About COVID-19 by Carol Lynn Esposito, EdD, JD, MS, RN-BC, NPD; Devneet Kaur Kainth, MPH, BS; and Shelly Lim, MPH, BA

n Sexual Well-Being and Screening for Risky Sexual Behaviors: A Quantitative Retrospective Study by Annemarie Rosciano, DNP, MPA, ANP-C and Barbara Brathwaite, DNP, MSN, RN, CBN

n What’s New in Healthcare Literature

n CE Activities: Breastfeeding Disparities Among Communities Lacking Access to Lactation Consultants During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Theory-Guided Paper; Venting the Truth About COVID-19; Sexual Well-Being and Screening for Risky Sexual Behaviors: A Quantitative Retrospective Study

THE JOURNAL

of the New York State

VOLUME 49, NUMBER 1

Nurses Association

n Editorial: Ordinary Essential............................................................................................................................................................ 3 by Anne Bové, MSN, RN-BC, CCRN, ANP; Audrey Graham-O’Gilvie, DNP, RN, ACNS-BC, CCRN-k; Meredith King-Jensen, PhD, MSN, RN; Alsacia L. Sepulveda-Pacsi, PhD, DNS, RN, FNP, CCRN, CEN; and Coreen Simmons, PhD-c, DNP, MSN, MPH, RN n Breastfeeding Disparities Among Communities Lacking Access to Lactation Consultants During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Theory-Guided Paper 5 by Cynthia Flynn, BA, RN, IBCLC and Audrey Graham-O’Gilvie, DNP, RN, ACNS-BC, CCRN-k n Venting the Truth About COVID-19 .......................................................................................................................................................... 11 by Carol Lynn Esposito, EdD, JD, MS, RN-BC, NPD; Devneet Kaur Kainth, MPH, BS; and Shelly Lim, MPH, BA n Sexual Well-Being and Screening for Risky Sexual Behaviors: A Quantitative Retrospective Study...................................................................................................................................................................................................... 28 by Annemarie Rosciano, DNP, MPA, ANP-C and Barbara Brathwaite, DNP, MSN, RN, CBN n What’s New in Healthcare Literature ..................................................................................................................................................... 39

n CE Activities: Breastfeeding Disparities Among Communities Lacking Access to Lactation Consultants During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Theory-Guided Paper; Venting the Truth About COVID-19; Sexual Well-Being and Screening for Risky Sexual Behaviors: A Quantitative Retrospective Study ................................................................................... 43

THE JOURNAL

of the New York State Nurses Association

n The Journal of the New York State Nurses Association Editorial Board

Anne Bové, MSN, RN-BC, CCRN, ANP

Clinical Instructor New York, NY

Audrey Graham-O’Gilvie, DNP, RN, ACNS-BC, CCRN-k

Assistant Professor Mount Saint Mary College Newburgh, NY

Meredith King-Jensen, PhD, MSN, RN

Adjunct Professor Mercy College Dobbs Ferry, NY Nurse Consultant Veterans Administration Bronx, NY

Alsacia L. Sepulveda-Pacsi, PhD, DNS, RN, FNP, CCRN, CEN Registered Nurse III New York-Presbyterian Adult Emergency Department New York, NY

Coreen Simmons, PhD-c, DNP, MSN, MPH, RN Professional Nursing Practice Coordinator Teaneck, NJ

n

Carol Lynn Esposito, EdD, JD, MS, RN-BC, NPD, Co-Managing Editor

Lucille Contreras Sollazzo, MSN, RN-BC, NPD, Co-Managing Editor

Christina Singh DeGaray, MPH, RN-BC, Editorial Assistant

The information, views, and opinions expressed in The Journal articles are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the New York State Nurses Association, its Board of Directors, or any of its employees. Neither the New York State Nurses Association, the authors, the editors, nor the publisher assumes any responsibility for any errors or omissions herein contained.

The Journal of the New York State Nurses Association is peer reviewed and published biannually by the New York State Nurses Association. ISSN# 0028-7644. Editorial and general offices located at 131 West 33rd Street, 4th Floor, New York, NY, 10001; Telephone 212-785-0157; Fax 212-785-0429; email info@nysna.org. Annual subscription: no cost for NYSNA members; $17 for nonmembers.

The Journal of the New York State Nurses Association is indexed in the Cumulative Index to Nursing, Allied Health Literature, and the International Nursing Index. It is searchable in CD-ROM and online versions of these databases available from a variety of vendors including SilverPlatter, BRS Information Services, DIALOG Services, and The National Library of Medicine’s MEDLINE system. It is available in microform from National Archive Publishing Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Journal of the New York State Nurses Association, Volume 49, Number 1 2

©2022 All Rights Reserved

The New York State Nurses Association

Ordinary Essentials

The phrases, “Never again” and “Never forget” are etched on memorials to holocaust survivors and in the hearts of those whose loved ones were murdered in communities destroyed by violent conflicts. Uttered by people outspoken against genocide and oppression, the words forewarn of atrocities that can and will perpetuate unless actively thwarted. In light of Russia’s war in Ukraine, many ask, “Why again?” and “Did we forget?”

Today, so many seek a secure place to live and thrive. Ukrainians, Afghans, Central and South American people are fleeing violent conflict in their native countries. Individuals everywhere struggle against many kinds of marginalization. Many of us take for granted precious, simple things: running water, food choices, a safe neighborhood, home, family, pets, and the comfort of mundane daily routines—but these are privileges worth fighting for.

In “Venting the Truth About COVID 19,” a history of pandemic and disease repeats itself. Outraged by soldiers dying of minor wounds, Florence Nightingale challenged “the way things were done” in the Crimean War Hospital. She used objective methods to identify hazardous infectious practices, implement hygienic change, and reduce casualties. Her approaches contributed to the modernization of health care. Interplay among government bureaucracy, egotistical leaders, pathogens, greed, and human nature fueled the pandemic. The resultant cacophony of injustices are being addressed by nursing unions, which amplify the voices of nurses demanding PPE and calling for safe health practices based on truth, for OSHA worker protection, and for sound public policy in defense of vulnerable healthcare workers.

In “Breastfeeding Disparities Among Communities Lacking Access to Lactation Consultants During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Theory-Guided Paper,” the authors recognize complex barriers encountered by mothers, particularly from economically disadvantaged Black communities. Their challenge to marshal community and hospital resources through a breastfeeding sponsorship program empowers mothers to provide the best kind of nutrition available to their baby. Here, women and caregivers are cognizant of the oppressive social forces of racism and modern isolation that can distress the fragile and emotionally charged weeks of early motherhood and child life. The article demonstrates the wisdom of ages, calling upon “a village” to boldly, gently promote the strength and well-being of the next generation.

In “Sexual Well-Being and Screening for Risky Sexual Behaviors: A Quantitative Retrospective Study,” it seems that young adults who were cultivated with certain gender norms and cultural pressures are predisposed to risk tolerance in their sexual lives. Given the ongoing HIV/AIDS epidemic, it is essential for young adults to make accurately informed decisions. Through screening and education, youth are supported by a caring, open campus health environment that challenges them to recognize and modify bodily and emotionally unsafe sexual practices.

We are struck by the hope, compassion, determination, and willingness of people who unite and stand to challenge oppression in order to retain what they hold dear. Healthcare workers support efforts to address building improved practices, equity in health care, and continued improvement in a sometimes-broken system. The articles in this issue reflect the invaluable nature of the ordinary; we applaud the efforts of those authors and readers who choose—and fight—to keep it.

Anne Bové, MSN, RN-BC, CCRN, ANP

Audrey Graham-O’Gilvie, DNP, RN, ACNS-BC, CCRN-k

Meredith King-Jensen, PhD, MSN, RN

Alsacia L. Sepulveda-Pacsi, PhD, DNS, RN, FNP, CCRN, CEN

Coreen Simmons, PhD-c, DNP, MSN, MPH, RN

n EDITORIAL

Journal of the New York State Nurses Association, Volume 49, Number 1 3

Breastfeeding Disparities Among Communities

Lacking Access to Lactation Consultants During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Theory-Guided Paper

Flynn, BA, RN, IBCLC and Audrey Graham-O’Gilvie, DNP, RN, ACNS-BC, CCRN-k

Acknowledgements

Christine Berté (MSMC School of Nursing Dean), Denise Garofalo (MSMC Librarian for Systems & Catalog Services),

Julia Flynn (MSMC Writing Center)

n Abstract

There is a significant difference in breastfeeding rates between Black and white infants, dependent upon their mother’s access to professional lactation care. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 73.7% of Black infants are ever breastfed in comparison to 86.7% of white infants (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2020a). The COVID-19 pandemic has complicated access to lactation care and illuminated the ongoing healthcare disparities in racial minority and economically marginalized populations across the United States. According to the CDC, some Black communities have higher rates of chronic diseases and also register lower breastfeeding rates. Research suggests that some chronic diseases can be mitigated by human milk consumption in infancy (Binns & Lee, 2019). In recognizing human milk’s value during infancy, the U.S. Surgeon General recommends access to international board certified lactation consultants (IBCLC) to support breastfeeding. Despite these government issued guidelines, data repeatedly demonstrates that hospitals lacking adequate lactation care in under-resourced Black communities continue to lack adequate distribution of breastfeeding information and lactation support.

A literature review was performed by the authors using the databases PubMed Central®, CINAHL, Google Scholar, and ProQuest. Sources include journal articles, books, websites, and reports (2012–2021). The authors used the topics related to general healthcare disparities, breastfeeding rates, and variances, as well as barriers to breastfeeding in impoverished communities in the United States. Access to lactation consultants during COVID-19 and lactation programs that address impoverished communities was also examined. The literature review consistently notes clear discrepancies in care. At a time when nationwide healthcare policies focus on preventative solutions to improve population wellness, this lack of equality in care in communities cannot be overlooked.

Nursing theorist Imogene King’s work on goal attainment may be applied to foster adaptation among interdisciplinary teams, IBCLC, and patients to increase breastfeeding rates among under-resourced Black communities. Guided by King’s Theory of Goal Attainment, this paper offers a proactive construction for an insidious public health dilemma. The purpose of this paper is to explore and disrupt inherent systematic healthcare inequities affecting Black communities by suggesting a new platform for lactation care. The application of theoretically-derived best practices will help to improve lifelong health outcomes, strengthen patient-provider relationships, and reduce healthcare spending across the lifespan of these currently underserved communities.

Keywords: professional lactation care, Imogene King Theory of Goal Attainment, breastfeeding sponsor, barriers to breastfeeding

Cynthia

Cynthia Flynn, BA, RN, IBCLC and Audrey Graham-O’Gilvie, DNP, RN, ACNS-BC, CCRN-k

Mount Saint Mary College Family Nurse Practitioner Program, Newburgh, New York

Journal of the New York State Nurses Association, Volume 49, Number 1 5

and

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought to light racial disparities in health care prevalent throughout the United States. Systemic discrimination, already prevalent in many racial minority communities due to limited funding and healthcare access, has only grown more prevalent during the global pandemic. For example, according to data from New York State, Blacks and Hispanics make up 22% and 29% of the New York City landscape, yet their COVID-19-related death rates are 28% and 34%, respectively (New York State Department of Health, 2021). A review of national data indicates that counties with higher proportions of African Americans also have higher numbers of COVID-19 cases and deaths (Peek et al., 2021). However, inequalities in healthcare delivery run deeper than the pandemic statistics of the past 2 years. These inequalities have been documented extensively in the Black, Latinx, and other medically underrepresented communities for more than 120 years by government and academic researchers (Levins, 2019). In the United States, Black men are more likely to be diagnosed and succumb to prostate cancer, yet they are disproportionately underrepresented in prostate cancer screenings (Alexis & Worsley, 2018). Data from the Pennsylvania Medicaid system showed that managed care organizations’ poor performance with minority populations has directly correlated with greater racial differences within communities served (Parekh et al., 2017).

Healthcare Disparities Beginning at Birth

According to the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (ODPHP) Healthy People 2020 national objectives for improving lives, a health disparity is a health difference that is closely linked with social, economic, or environmental disadvantage (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion [ODPHP], 2020). Healthcare disparities begin in infancy and impact health throughout a person’s lifespan. Breastfeeding is where this often begins. Denying an infant the basic opportunity to breastfeed, due to its racial and socioeconomic environment, is an unconscionable injustice.

When considering a range of infant feedings, nothing comes close to the multitude of benefits that human milk provides. Human breastmilk delivers the greatest number and quality of health benefits to mother and baby, which is why it is often referred to as “superfood.” For the pair, increased bonding and reduction in postpartum depression may foster healthier emotional environment early in life. Protection against infections and chronic diseases such as diabetes (type 1 and 2), obesity, and childhood and reproductive cancers also exists (American Academy of Pediatrics [AAP], 2020). Since 2012, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), in recognition of these benefits, recommends breastfeeding exclusively for newborns in the first six months of life or more. It is estimated that if 90% of people breastfed according to guidelines, the United States would save more than $13 billion in health care costs per year (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2020). Because science affirms breastfeeding as the superior choice for infant feeding, the U.S. Surgeon General created a call to action recommending access to international board certified lactation consultants (IBCLC) and breastfeeding support for every mother and baby (CDC, 2019).

Breastfeeding Data

Human milk is unequivocally regarded as the best nutrition for all infants. Yet, according to data from the CDC, a percentage of Black infants

are repeatedly missing this important early-stage development opportunity. Blacks historically have disproportionately higher rates of cancer, diabetes, and obesity than whites (CDC, 2017). Breastfeeding can help reduce these threats to health and wellness, and benefits of breastfeeding are lifelong. Convenient access to early intervention is the key to making and reaching breastfeeding goals.

In 2015, the CDC added several breastfeeding questions to their National Immunization Survey-Child (NIS-Child) to track the rates of breastfeeding among Blacks and non-Hispanic whites at birth, 3 months, and 6 months of age (Beauregard et al., 2019). The results of the NIS-Child revealed that breastfeeding initiation rates for Black infants were 16.5% lower than white infants of the same age. Furthermore, at 3 months of age, the consumption of any human milk for Black breastfeeding babies was 14.7% lower than for white babies. At 6 months, the disparity grew to 17.3% (Figure 1). The CDC reported that low-income families who receive the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) have lower breastfeeding rates (77%) compared with families who qualify, but don’t utilize WIC (82%) and those who do not qualify for WIC (92%) (CDC, 2020a).

Barriers to Breastfeeding

Generally, Black women who are in a low-income bracket, are less likely to breastfeed for several reasons, including language and cultural

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 % Initiated Breastfeeding % Any Breastfeeding at 3 Months % Any Breastfeeding at 6 Months 70% 71% 61% 45% Non-Hispanic White Non-Hispanic Black 59% 86%

Comparison of Breastfeeding Initiation and Continuation According to Race Note. Figure 1 shows the variation in breastfeeding rates of initiation and continuation between non-Hispanic white and Black people. Adapted from “Racial disparities in breastfeeding initiation and duration among U.S. infants born in 2015,” by J.

H. C. Hamner, J. Chen, W. Avila-Rodriguez, L. D. Elam-Evans, and C.

Perrine, 2019, Morbidity and Mortality Weekly

In the

6 Journal of the New York State Nurses Association, Volume 49, Number 1

Figure 1

L. Beauregard,

G.

Report, 68(34), pp. 745–748 (https://doi. org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6834a3).

public domain.

n Breastfeeding Disparities Among Communities Lacking Access to Lactation Consultants During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Theory-Guided Paper

Breastfeeding Disparities Among Communities Lacking Access to Lactation Consultants During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Theory-Guided Paper

barriers, and a lack of support at home, work, and within healthcare systems (Leruth et al., 2017). Disparities in breastfeeding knowledge and access to lactation care are also leading concerns causing these discrepancies. In fact, less than 25% of lower-income Black women receive information on breastfeeding from public health and social service venues. Hospitals that service low-income Black communities also report lower rates of breastfeeding initiation (Beauregard et al., 2019).

To further understand the impact that the healthcare industry has on breastfeeding rates, the CDC created the Maternity Practices in Infant Nutrition and Care (mPINC), a national survey for maternity wards meant to help hospital administrators celebrate existing strengths and target areas for improvement in their practices and policies that affect infant feeding. Every two years, the CDC invites hospitals to fill out the mPINC survey. In 2018 alone, 2,045 hospitals participated and were asked about early postpartum care practices; feeding practices; education and support of mothers and caregivers; staff and provider responsibilities and training; and hospital policies and procedures. Organized into six main areas of care called subdomains, policies and practices are then scored and comprise each state’s total mPINC score (CDC, 2020b).

Figure 2

In 2011, the CDC began correlating mPINC scores with U.S. Census data by ZIP codes to identify trends in maternity care and breastfeeding promotion and guidance equity. A CDC Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (Figure 2) revealed that hospitals were less likely to meet five of the 10 recommended mPINC indicators if they were in ZIP codes where the Black population was greater than the national average. The indicators included early initiation of breastfeeding (46.0% compared with 59.9%), limited use of breastfeeding supplements (13.1% compared with 25.8%), rooming-in (27.7% compared with 39.4%), limited use of pacifiers (30.5% compared with 37.9%), and post-discharge support (23.9% compared with 29.9%) (Lind et al., 2014). Survey findings revealed that the hospitals in question lacked common practices that typically promote lactation. Practices such as breastfeeding attempts in the first hour after birth, skin-to-skin contact, and avoidance of glucose water and infant formula when not medically indicated were inadequately implemented.

Often, despite the U.S. Surgeon General’s recommendations, these hospitals were not staffed with IBCLCs and/or staff training to support breastfeeding is inadequate (Beauregard et al., 2019). Research by Patel (2017) demonstrates the direct correlation between access to IBCLCs and

mPINC Scores Related to Racial Composition of Patient Populations

Served by Hospitals

Early initiation of breastfeeding: 20% of healthy, full-term, breastfed infants initiate breastfeeding within 1 hour of uncomplicated vaginal bir th.

Limited use of breastfeeding supplements: <10% of healthy, full-term, breastfed infants are supplemented with formula, glucose water or water.

Rooming-in >90% of healthy, full-term infants, regardless of feeding method, remain with their mother for at least 23 hours per day during the hospital stay.

Blacks < 12.2

Limited use of paci ers: <10% of healthy, full-term, breastfed infants are given paci ers by maternity care sta members

Blacks > 12.2 % Point Di erence

Post- discharge suppor t: hospital routinely provides three modes of post- discharge suppor t to breastfeeding mothers (physical contact, ac tive reaching out, and referrals).

Note. Figure 2 shows that as the percentage of Blacks in a population increases, the mPINC scores for the population’s ZIP code decreases. The mPINC score of a hospital is based on a 10-point survey that addresses the utilization of best practices for breastfeeding initiation and continuation. Adapted from “Racial disparities in access to maternity care practices that support breastfeeding – United States, 2011,” by J. Lind, C. Perrine, R. Li, K. Scanlon, and L. Grummer-Strawn, 2014, Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (https://www.cdc. gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6333a2.html). In the public domain.

Note. Description of the various

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70

%

60% 13% 27% 12% 12% 40% 11% 30% 30% 33%

%

ces of quantitati data used 48% 8% 8% 28% 38%

7 Journal

Volume 49, Number 1

of the New York State Nurses Association,

n

increased rates of initiation and continuation of exclusive breastfeeding in the first month of life. This data confirms that disparities in access to quality breastfeeding assistance exist in Black communities that are in a low-income bracket, which negatively affects breastfeeding rates.

COVID-19 Effects on Breastfeeding

The COVID-19 pandemic has further complicated infancy for new mothers. During a pandemic, as with natural crises like devastating hurricanes and earthquakes, the value of breastfeeding becomes clearer. In a state of uncertainty, human milk is one form of nutrition that mothers can count on. Families never need to concern themselves with finding substitutes in their local markets or worry that their water sources for preparation are contaminated or inaccessible. An Australian study (Hull et al., 2020) that examined the needs and concerns of breastfeeding mothers during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic found that mothers commonly expressed feelings of isolation, stress, and the need for professional lactation intervention. Many could not access their healthcare provider face-to-face, either because of fear of contracting COVID-19 or lack of appointments available, according to the study. Decreased access to care was common throughout the United States during the first surge of the pandemic.

Developing Solutions

Addressing the barriers to breastfeeding for Black women is one of the keys to improving care for future generations of families in America. The data describes variances in breastfeeding rates between Black and white infants in disadvantaged communities in the United States. According to a report by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) Women’s Right Project, Black women face physical, emotional, and cultural obstacles to breastfeeding, many of the constraints owing to limited financial resources. Black women’s labor participation rate of 60.2% is higher than the rate for women of all other races. Additionally, Black women are oftentimes the primary economic support for their families, with 70.7% of Black mothers as sole breadwinners and 14.7% as co-breadwinners (Echols, 2019). Many Black women experience economic pressures that motivate them to return to the workplace earlier after giving birth than women of any other race. This paper highlights critical deficiencies found in the health systems of Black communities in low income brackets and the lack of lactation consultant programs and support. To disrupt this entrenched inequality, the authors propose an anticipatory approach, guided by Imogene King’s Theory of Goal Attainment. Now, more than ever, it is of utmost importance that all families have access to equitable resources that support the mother-baby dyad in breastfeeding and that families have access to tools to help them set and reach their breastfeeding goals.

A comprehensive support structure providing ongoing, professional guidance can help to improve breastfeeding outcomes.

Existing Models

Increased access to IBCLCs is supported by Sanchez et al. (2019). This work revealed that a comprehensive support structure providing ongoing, professional guidance can help to improve breastfeeding outcomes. Additionally, when access to health care is limited and internet service is unavailable (as is more likely the case in communities in a low-income bracket), mobile clinics are often used. However, infection control and social distancing concerns in mobile clinics arose during the COVID-19 pandemic, further complicating processes and solutions.

An excellent model for care already exists in the work done by Leruth et al. (2017). In this study, healthcare providers increased breastfeeding rates in a vulnerable population by partnering with a local hospital to provide intensive one-to-one education and ongoing support. By integrating inpatient and outpatient resources in hospitals that serve Black communities in a lowincome bracket, more mothers were enabled to breastfeed. The authors suggest combining ideas from Leruth et al.’s (2017) Chicago clinic with COVID-19 pandemic adjustments taken into consideration. We also suggest an additional level of support, guided by the Theory of Goal Attainment by Imogene King as described in the text, “Nursing Theories and Nursing Practice” by Marlaine Smith (2020). King’s theory is a framework by which providers can deliver modern, ongoing and effective care and focusing on incremental progress to be made by setting and achieving goals.

Application of Nursing Theory

King’s Theory of Goal Attainment begins with the concept of capturing the essence of nursing in the form of face-to-face transactions (Smith, 2020). The theory emphasizes the value of the nurse-patient relationship in communicating, setting goals, and moving both nurse and patient together to achieve goals. When used in an interdisciplinary setting, goals are achieved by the patient when each member of the team realizes and accepts their role and function in reaching chosen goals. Each member brings a specific purpose to the group, and individualized tasks are accomplished by the teammates according to their role and expertise. Communication within the group is ongoing, fluid, patient-centered, and it includes the patient as an active participant. This process promotes adaptation of the patient and team as one.

The Nurse Practitioner Leads a Multidisciplinary Team to Address Gaps in Care

In a breastfeeding model of care, applying King’s theory would entail exchanging information on breastfeeding and assisting the client in establishing a commitment to, and an initial goal for, breastfeeding. The process would begin during pregnancy and continue through infant weaning. As the process unfolds, further, measurable goals can be set in a stepwise or gradual fashion. Each goal should be accompanied by a means to attain the goal in the form of a nursing care plan. The care plan would be implemented using lactation resources through the hospital-based breastfeeding office, which would allow providers to capture newborns at birth.

A nurse practitioner would direct the service and be responsible for assessing, diagnosing, prescribing, admitting, and referring out the most complicated breastfeeding cases. To promote fiscal responsibility, IBCLCs and certified lactation counselors (CLC) can be utilized to reiterate breastfeeding best practices and help resolve varying levels of breastfeeding

8 Journal of the New York State Nurses Association, Volume 49, Number 1

n Breastfeeding Disparities Among Communities Lacking Access to Lactation Consultants During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Theory-Guided Paper

A breastfeeding sponsor would also function as a contemporary companion who could provide an outlet during the fragile and emotionally charged weeks of early motherhood.

challenges. This proposed service would operate out of the local hospital and push into the community in the form of home health visits. These visits would provide individualized care, be socially distanced, and also adhere to standard infection control practices. Care would begin in the third trimester of a pregnancy, and pinpointed care would occur at crucial times along the breastfeeding timeline such as at birth, in the first 2 weeks at home, during growth spurts and teething, as well as during a mother’s return to work, the introduction of solid foods, and weaning. Evaluation of the plan would occur weekly in early infancy, and as breastfeeding is further established, evaluations would continue monthly for the duration of the breastfeeding relationship.

Breastfeeding Sponsorship: A Fresh Concept

There is noted success in the literature to indicate that that peer breastfeeding sponsorship could translate for use with Black mothers to increase their breastfeeding success (Kim et al., 2017). According to the report, researchers who studied an Illinois WIC office recommended providing emotional and informational support to Black women by establishing support circles that are otherwise lacking. Adding this supportive and social aspect would contribute to increasing both breastfeeding initiation and duration rates for Black women, whose cultural background may have deterred breastfeeding. Some Black women have seen breastfeeding as reverting to “slavery days” when feeding a child by breast was the only option, according to a report in Minority Nurse (Johnson, 2016). With the introduction of baby formulas in the 1800s, campaigns led many women to believe breastfeeding was a choice only for lower-income mothers.

As an aid to addressing many of these stigmas, a breastfeeding sponsor would also function as a contemporary companion who could provide an outlet during the fragile and emotionally charged weeks of early motherhood. Mirroring other successful sponsorship programs, a one-on-one peer breastfeeding sponsor can serve as a close family member or friend for those who don’t have familial support when breastfeeding. Members of the community who have personal experience with breastfeeding can act as sponsors, thereby providing new mothers a

“chain” of support that includes a breastfeeding sponsor, IBCLC or CLC, and nurse practitioner. In keeping with the essence of King’s theory, each member in such a support team will be focused on the common goal set by the patient and her care team.

Progress, any changes, as well as the achievement of goals would be communicated within the team to allow for continued development and holistic adaptation. Professional lactation care would be accessible in the home, which will keep newborns and their mothers out of hospitals and offices and away from exposure to diseases such as COVID-19. Consideration will have been made for the use of telehealth for lactation consultations and video phone calls for sponsor support during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, when telephones and internet services are available. A review of literature by Ferraz dos Santos et al. (2020) shows the use of telehealth as a viable option for providing lactation consultations when in-person care is not feasible. Illness and disease that are avoidable with breastfeeding could be reduced with improved breastfeeding outcomes from such measures.

Conclusion

Human milk, often touted as “liquid gold” for its beneficial health properties, is the simplest and purest of human infant needs. Although on the surface this superfood is available to all infants, data shows this isn’t always the case due to any number of factors. Applying an action-based approach to this public health call by fortifying Black communities that are in a low-income bracket with additional breastfeeding support and resources would prove beneficial in radically reducing breastfeeding and its related health discrepancies between various racial communities in the United States. Rather than relying on infant formula due to numerous environmental, cultural, and job-related obstacles, the measures discussed in this paper would support both the child’s and mother’s health, as well as a family’s financial wellness if resources focused on increased rates of breastfeeding to cut down on both formula and medical expenses. Subsidized lactation care would reduce the burden of disease due to increased adherence to the established breastfeeding guidelines. Healthcare dollars saved by decreased rates of illness could be reinvested in lactation care to allow for continued services. Applying the concepts developed originally by Imogene King allows caregivers to work as a team to help persons in need establish and meet their breastfeeding goals. Through continuous care, documentation, and evaluation of achieved goals, the proposed approach would succeed. Education and preventative, proactive work to address deficiencies in the current models of breastfeeding delivery to underserved Black communities would begin to provide equity in resources and results in breastfeeding goals as established by the CDC. Providing a structured lactation service that underscores humans caring for humans in peer networks and communities is the backbone of King’s work. Implementation of the proposals offered by this paper would enhance health and wellness for underserved black communities.

9 Journal of the New York State Nurses Association, Volume 49, Number 1

n

Breastfeeding Disparities Among Communities Lacking Access to Lactation Consultants During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Theory-Guided Paper

Alexis, O., & Worsley, A. (2018). An integrative review exploring Black men of African and Caribbean backgrounds, their fears of prostate cancer and their attitudes towards screening. Health Education Research, 33(2), 155–166. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyy001

American Academy of Pediatrics. (2012). Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics, 129(3), e827–e841. https://doi.org/10.1542/ peds.2011-3552

American Academy of Pediatrics. (2020). Benefits of breastfeeding. Retrieved December 1, 2020, from https://www.aap.org/en-u.s./ advocacy-and-policy/aap-health-initiatives/Breastfeeding/Pages/ Benefits-of-Breastfeeding.aspx

Beauregard, J. L., Hamner, H. C., Chen, J., Avila-Rodriguez, W., ElamEvans, L. D., & Perrine, C. G. (2019). Racial disparities in breastfeeding initiation and duration among U.S. infants born in 2015. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 68(34), 745–748. https://doi.org/10.15585/ mmwr.mm6834a3

Binns, C., & Lee, M. K. (2019). Public Health Impact of Breastfeeding. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Global Public Health. https://doi. org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190632366.013.66

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017). African American health. Retrieved December 1, 2020, from https://www.cdc.gov/ vitalsigns/aahealth/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). Breastfeeding: Why it matters. Retrieved December 1, 2020, from https://www.cdc.gov/ breastfeeding/about-breastfeeding/why-it-matters.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020a). Breastfeeding facts. Retrieved December 1, 2020, from https://www.cdc.gov/ breastfeeding/data/facts.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020b). mPINC 2018 National results report. Retrieved December 1, 2020, from https:// www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/mpinc/national-report.html

Echols, A. (2019, August 15). The challenges of breastfeeding as a black person. American Civil Liberties Union. https://www.aclu.org/blog/ womens-rights/pregnancy-and-parenting-discrimination/challengesbreastfeeding-black-person

Ferraz dos Santos, L., Borges, R., & de Azambuja, D. (2020). Telehealth and breastfeeding: An integrative review. Telemedicine and e-Health, 26(7), 837–846. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2019.0073

Healthy People. Healthy People 2020. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020

Hull, N., Kam, R., & Gribble, K. (2020). Providing breastfeeding support during the COVID-19 pandemic: Concerns of mothers who contacted the Australian Breastfeeding Association. Breastfeeding Review, 28( 3), 25–35.

Johnson, N. (2016). African American women and the stigma associated with breastfeeding. Minority Nurse. https://minoritynurse.com/africanamerican-women-and-the-stigma-associated-with-breastfeeding

Kim, J. H., Fiese, B. H., & Donovan, S. M. (2017). Breastfeeding is natural but not the cultural norm: A mixed-methods study of first-time breastfeeding, African American mothers participating in WIC. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 49 (7). https://doi. org/10.1016/j.jneb.2017.04.003

Leruth, C., Goodman, J., Bragg, B., & Gray, D. (2017). A multilevel approach to breastfeeding promotion: Using healthy start to deliver individual support and drive collective impact. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 21(S1), 4–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-017-2371-3

Levins, H. (2019). Struggling to escape poor health: 120 Years of health disparities reports. University of Pennsylvania Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics. https://ldi.upenn.edu/news/struggling-escapepoor-health-120-years-health-disparities-reports.

Lind, J., Perrine, C., Li, R., Scanlon, K., & Grummer-Strawn, L. (2014). Racial disparities in access to maternity care practices that support breastfeeding—United States, 2011. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved December 1, 2020, from https://www.cdc.gov/ mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6333a2.htm

New York State Department of Health. (2021). Workbook: Nys-covid19tracker. https://covid19tracker.health.ny.gov/views/NYS-COVID19Tracker/NYSDOHCOVID-19Tracker-Fatalities?%3Aembed=yes&%3 Atoolbar=no&%3Atabs=n%29

Parekh, N., Jarlenski, M., & Kelley, D. (2017). Prenatal and postpartum care disparities in a large Medicaid program. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 22(3), 429–437. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-017-2410-0

Patel, S. (2017). The effectiveness of lactation consultants and lactation counselors on breastfeeding outcomes. Journal of Clinical Chiropractic Pediatrics, 16, 1266.

Peek, M. E., Simons, R. A., Parker, W. F., Ansell, D. A., Rogers, S. O., & Edmonds, B. T. (2021). COVID-19 among African Americans: An action plan for mitigating disparities. American Journal of Public Health, 111(2), 286–292. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2020.305990

Sanchez, A., Farahi, N., Flower, K. B., & Page, C. P. (2019). Improved breastfeeding outcomes following an on-site support intervention in an academic family medicine center. Family Medicine, 51(10), 836–840. https://doi.org/10.22454/fammed.2019.698323

Smith, M. (2020). Nursing theories and nursing practice (5th ed.). F. A. Davis Company.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2020). Breastfeeding: Surgeon General’s call to action fact sheet. Retrieved December 1, 2020, from HHS.gov.https://www.hhs.gov/surgeongeneral/reports-and publications/breastfeeding/factsheet/index.html

n References

10 Journal of the New York State Nurses Association, Volume 49, Number 1

n Breastfeeding Disparities Among Communities Lacking Access to Lactation Consultants During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Theory-Guided Paper

Venting the Truth About COVID-19

Carol Lynn Esposito, EdD, JD, MS, RN-BC, NPD

Devneet Kaur Kainth, MPH, BS

Shelly Lim, MPH, BA

n Abstract

Corresponding to the protestations made by Florence Nightingale more than 150 years ago during the Crimean War and in her Notes on Nursing (1960) and Notes on Hospitals (1959), this study amplifies the outcries of unionized nurses who have worked on the front lines of the COVID-19 pandemic and details their observations on the administration of nursing and the responses of healthcare organizations during the pandemic. In this article and study, we highlight key events that occurred during the pandemic that illustrate non-conformity with Nightingale’s visions for healthcare reform in the areas of organizational responses, critical thinking and problem analyses, implementation of interventions and positive outcomes, detailed documentation and statistical analysis, tenacious political advocacy to reform healthcare systems, and advancement of nursing practice based on evidence. Now, and given that the 200-year anniversary of Florence Nightingale’s birth in 2020, this article compares and explores how the appalling defects of hospitals during the Crimean War resemble and personify the appalling conditions of New York hospitals during the COVID-19 pandemic.

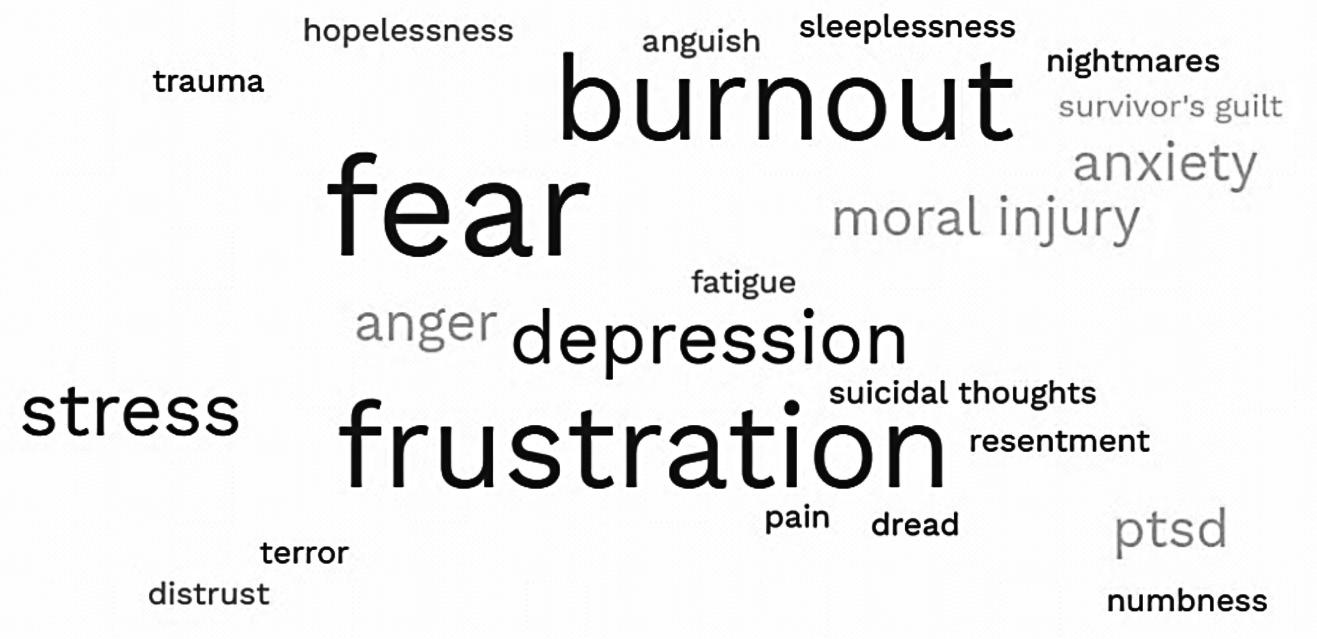

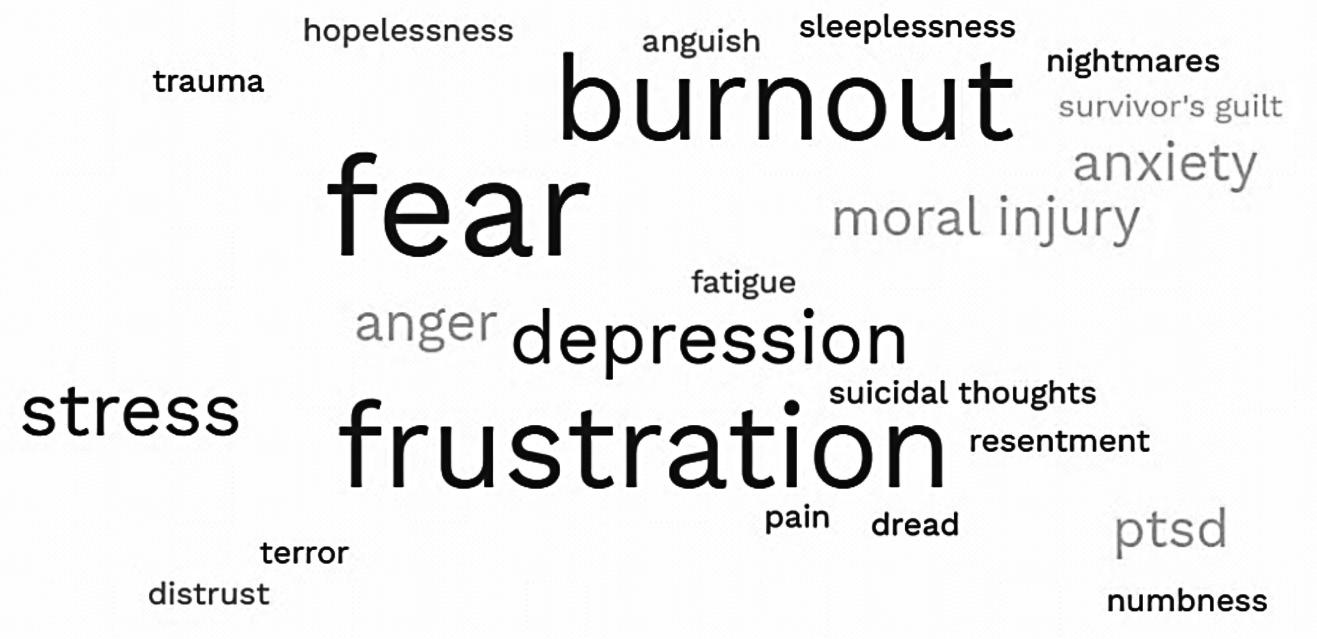

Keywords: stress, pilot study, stress-reducing intervention, work-stress impact on nurse health, contractual agreement, peer-led hospital intervention, nurse self-care

Introduction

Through her work during the Crimean War, Florence Nightingale learned the enormously important lesson that problems could be solved and high death rates brought down, even radically, when their causes were ascertained and the appropriate changes were made. Additionally, Nightingale was always conscious of the mortal risk to nurses from inferior hospital conditions and called for the incidence of deaths to be

The COVID-19 crisis unveiled many fractures in the United States healthcare system.

Carol Lynn Esposito, EdD, JD, MS, RN-BC, NPD

officially tracked, which she argued in each of the three editions of Notes on Hospitals (1959) from 1858 to 1863. In her first papers on hospitals, Nightingale identified common hospital defects, which included poor ventilation and the agglomeration of a large number of sick under the same roof (McDonald, 2020).

Background and Significance

The COVID-19 crisis unveiled many fractures in the United States healthcare system, including lack of emergency preparedness, lack of proper ventilation systems in acute care facilities, lack of personal protective equipment (PPE) for healthcare staff, lack of adequate staffing to meet the needs of the patients, cohorting of patients in inappropriate numbers and on inappropriate patient care units, distrust by healthcare staff and

Nursing Education and Practice, New York State Nurses Association, New York, New York Devneet Kaur Kainth, MPH, BS

Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University, New York, New York Shelly Lim, MPH, BA

SUNY Downstate School of Public Health, Brooklyn, New York

Journal of the New York State Nurses Association, Volume 49, Number 1 11

the public in health officials and departments, and inequities in health determinants for minority populations. New York, the epicenter of the “first wave” of cases in the United States, was a microcosm of the devastation that resulted from the failures of the healthcare system during an emergency.

March 1, 2020, marked the first confirmed case of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in New York State (NYS). In New York State, cases rose exponentially, reaching 76 cases by the first week of March, 613 cases by the second week, 10,356 cases by the third week, and 52,318 by the fourth week (Konda et al., 2020). By the end of the month, New York State accounted for roughly 5% of confirmed cases globally (McKinley, 2020); and by March 7, 2021, the number of positive cases of COVID-19 in New York State reached 1.7 million (Statista, 2021).

The first wave triggered unprecedented public fear and endangered the health and well-being of all people, but especially vulnerable populations. Controlling the spread of COVID-19 became a singular focus, as governmentmandated shutdowns were ordered to slow the spread of the new, highly infectious viral agent and severe acute respiratory syndrome. The pandemic precipitated social disruption, overwhelming and overly burdensome healthcare utilization, and economic instability. New York City streets became barren and ransacked grocery stores became the new “normal” for a time (Vannabouathong, et al., 2020).

COVID-19 displays a variety of clinical manifestations, ranging from asymptomatic presentation to critical illness with severe pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, respiratory failure, and/or multiple organ failure (Tsai et al., 2020). Most critically ill cases and fatalities occur in patients who are elderly, immunocompromised, and/or who suffer from comorbidities. Stark disparities in infection rates and fatalities have presented in minority populations such as Black and Hispanic communities in New York (University at Albany, SUNY, NYS COVID-19 Minority Health Disparities Team, 2020).

Moreover, long-term impacts of COVID-19, known as long, post-acute or chronic COVID illness, have been observed. Though the case definition of long COVID remains ambiguous, research suggests that one-third of patients experience symptoms that last 2–6 weeks post onset of disease, and 11–25% have symptoms that persist beyond 3 months (Alwan & Johnson, 2021). The medical community has also observed immense psychological burden on patients who suffer from COVID-19 and all those who have lived through this life-changing, traumatic pandemic (Kovner et al., 2021; Cullen et al., 2020).

As the pandemic marches on into its third year, health professionals have continued to work on the front lines to care for patients while they understand and mourn the fact that this deadly disease has no cure and the healthcare community is woefully unprepared to meet the needs of its patients or the safety needs of its practicing professionals.

Theoretical Underpinnings

Eight key components of Florence Nightingale’s work and directives for high-quality nursing that parallel registered professional nurses’ (RNs) interventions in patient care during a pandemic include:

l providing high-quality, compassionate patient care; l driving best practices based on advances in medicine and science; l implementing and monitoring of evidence-based health care;

l supporting high-quality health care for all; l understanding that health status is linked to environmental conditions that are now termed “social determinants of health”; l collaborating across disciplines in coordination of care; l advocating for the health and welfare of nurses and their work environment; and l practicing as a political advocate for changing health systems.

The role of the RN was created to meet the increasingly complex and evolving needs of patients and communities. This resembles the mission undertaken by Nightingale and her vision of nursing. The RN’s spheres of impact affect each facet in patient care, nursing and nursing practice, and healthcare systems and organizations, reflecting Nightingale’s work and beliefs about patient care, nursing standards, healthcare reform and advocacy, and training (Matthews at al., 2020).

Study Aims

The purpose of this article and study is to explore and compare how the appalling defects of the hospitals during the Crimean War resemble and personify the appalling conditions of New York hospitals during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In this article and study, we aim to highlight key events that occurred during the pandemic that illustrate non-conformity with Nightingale’s visions for healthcare reform in the areas of organizational responses, critical thinking and problem analyses, implementation of interventions and positive outcomes, detailed documentation and statistical analysis, tenacious political advocacy to reform healthcare systems, and advancement of nursing practice based on evidence.

Methods

Participants and Study Design

To assess the experience of unionized nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic, a mixed qualitative and quantitative research method approach was utilized. A mixed method approach is powerful because it encourages the synthesis of qualitative and quantitative data and, often, takes advantage of the strengths of both disciplines. However, it is an approach that lacks a standardized framework for data collection, integration, and analysis (Östlund et al., 2011). It was important for this article to capture the complexity and depth of nurses’ responses and experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. It was equally important to assess trends in issues related to worker health and safety among the several facilities examined in this study. As such, a mixed method approach was employed.

Quantitative Data Collection

Several sources were utilized to gather quantitative data, including U.S. Department of Labor Occupational Health and Safety Administration (OSHA) employer-generated Logs of Work-Related Injuries and Illnesses (Form 300) for private sector employees; the NYS Department of Labor Public Employee Safety and Health (PESH) Logs of Work-Related Injuries and Illnesses (Form SH-900) for public sector employees; nurses’ COVID-19 daily diaries; nurses Protest of Assignment Forms (POAs); and a Nurse 2021

Journal of the New York State Nurses Association, Volume 49, Number 1 12 n Venting the Truth About COVID-19

Venting the Truth About COVID-19

Table 1

Demographics of Facilities Selected for This Study

Private hospital locations

Bronx, NY

Staten Island, NY

Somers Point, NJ Albany, NY Brooklyn, NY Flushing, NY Olean, NY Dunkirk, NY Brooklyn, NY Poughkeepsie, NY

Public hospital locations

Elmhurst, NY Valhalla, NY Buffalo, NY Bronx, NY

Long-term care facility location Buffalo, NY

Home health agency location Bronx, NY

Health department location Buffalo, NY

Correctional facilities locations

Buffalo, NY

Various NYC locations

COVID-19 Survey. OSHA and PESH injury logs were obtained via a union demand for information from 24 various healthcare facilities throughout New York State. COVID-19 daily diaries and POA forms were obtained from RNs working in New York in union hospitals and were generated voluntarily in the usual course of business and sent to the union for analysis. The Nurse 2021 COVID-19 Survey was a 34-question SurveyMonkey® survey sent via email to 44,000 unionized RNs throughout New York State. The 44,000 unionized RNs constituted a convenience sample of study population. The survey elicited 1,170 voluntary responses.

Several facilities, shown in Table 1, were selected to be highlighted in this study. These facilities constituted a convenience sample and were chosen to showcase differences in the progression of the COVID-19 crisis in New York State, taking into account variations in geographic region, COVID-19 outbreak periods, union nurse member political and concerted actions, and facility type (public/private, small/large).

The strengths and weaknesses of each data source are presented below in Table 2

Qualitative Data Collection

A convenience sample of 20 registered professional nurses working on COVID units and six nurse representatives volunteered to be interviewed by

Nurses, supported by their unions, have been at the forefront of the fight for improvements in patient care and worker safety throughout the COVID-19 pandemic.

the authors to provide firsthand accounts and insights into their experiences during the pandemic.

Nurses who volunteered to be interviewed were contacted through emails, texts, and phone calls to schedule one-on-one qualitative interviews. The interviews were conducted from June 24 to July 26, 2021, mainly over Zoom® and phone. Each interview lasted approximately 30 minutes to 1 hour. Consent was voluntary, and after consent was obtained, interviews were recorded and transcribed using the online transcript generator Otter.ai and coded using a matrix method in Microsoft Excel. The interviews were the primary form of qualitative data collected for this study.

Data analysis was conducted using Microsoft Excel and Salesforce. Tableau Desktop was used to create a map of this article’s healthcare facilities.

Results and Discussion

The following results correspond to Nightingale’s key events, which occurred during the Crimean War and that relate to events that occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic that illustrate nonconformity with Nightingale’s vision for healthcare reform (organizational responses and failures, critical thinking and problem analyses, implementation of interventions and positive outcomes, detailed documentation and statistical analysis, tenacious political advocacy to reform healthcare systems, and advancement of nursing practice based on evidence). A discussion of the results will immediately follow the reported results.

Organizational Responses and Failures

Lessons from Florence Nightingale are just as relevant today as they were more than 150 years ago. Nurses are unremittingly faced with innumerable complex healthcare delivery systems problems. While Florence Nightingale charted a path for modern nurses to become trusted and valued members of the healthcare team who employ data and evidence daily to plan patient care, our current systems of healthcare delivery are characterized by chaos and complexity. Despite a long list of health system inefficiencies that make delivering care challenging and stressful, nurses must maintain balance and ensure safe, efficient, and high-quality patient care.

This study describes nurses’ encounters with organizational and operational failures in the healthcare system that hindered timeliness of care and eroded quality and patient safety during the COVID-19 pandemic. Organizational failures fell into several broad categories: (1) lack of equipment and supplies; (2) chaotic and ever-changing communications/guidance; (3) lack of staffing; (4) inadequate training; and (5) inadequate infection control. While Nightingale identified the need for nurses to observe, assess, understand, collect data, and plan nursing care, organizational dysfunction during the pandemic and time spent on operational failures wasted

13 Journal of the New York State Nurses Association, Volume 49, Number 1

n

Strengths and Weaknesses of Study Quantitative Data Sources

Data source Description Strengths Weaknesses

OSHA and PESH Injury and Illness Logs

COVID-19 daily diaries

Standardized logs of illnesses and injuries that occur in the workplace, reported by employers, as required by the U.S. and NYS Departments of Labor.

Nurses filled out information daily about the units they worked on, number of patients in their care, staffing ratios at their facilities, and other COVID-related issues. Since 3/25/2020 an impressive 11,196 responses have been obtained.

It facilitates comparisons among workplaces because data is collected in a standardized method.

It is a rich source of data that provides insight into daily working conditions for nurses.

It is prone to underreporting because employers decide which injuries and illnesses are work-related.

It is difficult to assess validity and reliability of data, since it is self-reported by nurses.

COVID Protest of Assignment (POA) forms

Nurses submitted COVID POAs to document unsafe assignments for reasons related to unavailable personal protective equipment (PPE), lack of training, inadequate staffing, increases in patient volume, and unsafe facility protocols.

It is a rich source of data that highlights unsafe working conditions and assignments.

Request for information (RFI)

Nurse 2021 COVID-19 Survey

A union requested for information from employers. Infection rate information from 139 facilities was obtained.

It is a survey containing 34 questions related to worker health and safety, COVID-19 infection, long COVID, workers’ comp, and mental health. The number of responses obtained was 1,252.

It is a legally enforceable request that can be mandated by National Labor Bureau.

Rich source of data that assesses impact of COVID-19 pandemic on a broad range of issues for nurses.

Limitation on the generalizability of the information due to sample size, although persistence of observations increases the credibility of the qualitative data.

It is difficult to assess validity and reliability and difficult to obtain information from employers even though required by law.

Difficult to assess validity and reliability of data since it is self-reported by nurses.

Note. Description of the various sources of quantitative data used to generate this report along with strengths and weakness of each data set.

nurses’ precious time, created moral distress, and detracted from core care responsibilities (Reinking, 2020). These categories will be discussed more fully below.

Critical Thinking and Problem Analysis

Nightingale’s statistical findings indicated that most deaths during the Crimean War were due to overcrowding, poor sanitation, and improper ventilation. Her data demonstrated the merits of quality nursing care: Survival rates increased from 50% to nearly 80% under the care of Nightingale and her nurses. Attention to rigorous infection prevention, hygiene and cleanliness, nutrition and hydration, and compassionate care were integral interventions that revolutionized nursing care practices and improved clinical outcomes (Reinking, 2020).

Fast forward over 150 years to today. Although nurses are effective at identifying core operational failures in our modern healthcare system, they’re often ill-equipped and ill-resourced to complete more in-depth, system-level problem-solving. Finding solutions to the current perplexing problems in health care would require nurses to develop, maintain, and refine their critical-thinking skills. Instead, due to the nature of the work environment, nurses are forced to create workarounds and do whatever it takes in the moment to care for their patients, use trial and error to find solutions,

and only involve others who are closest work friends in problem-solving rather than counting on previously unreliable managerial or governmental resources for solutions.

Lack of Equipment and Supplies

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE). Personal protective equipment has long been used by healthcare workers to reduce disease transmission. The SARS-CoV-2 virus has been known to be detectable and viable on plastic and stainless steel surfaces and in patient rooms for hours (Stewart et al., 2020). This suggests that gowns and gloves are necessary to protect healthcare workers. Although the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), pressured by the American Hospitals Association

Due to the nature of the work environment, nurses are forced to create workarounds and do whatever it takes in the moment to care for their patients.

Table 2

Journal of the New York State Nurses Association, Volume 49, Number 1 14

Truth About

n Venting the

COVID-19

Photo Source: Campanile & Boden, 2021. Retrieved from: https://nypost. com/2020/04/02/nurses-at-nyc-hospitalreceive-gowns-after-post-trash-bag-expose/.

and other employer groups, insisted that SARS-CoV-2 was transmitted only through contact and droplets, study after study confirmed that the virus can also be spread via airborne viral particulates (Zhang et al., 2020; Noorimotlagh et al., 2021). This means that, at a minimum, nurses and other healthcare workers should be provided with fit-tested N95 respirators (or a higher level of respiratory protection) for all patient care interactions (United States Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration, 29 CFR 1910 Subpart I).

Based on nurses’ COVID-19 pandemic daily diaries, we compiled the responses of nurses related to the status of access to PPE at their facilities. The response options included adequate, inadequate, unsure, and blank. Of the total 65 private facilities reviewed, there were only five facilities where less than 40% of its nurses indicated that there was “inadequate PPE.” Sixty private facilities and all 24 public facilities reviewed had over 40% of its nurses respond that there was “inadequate PPE” supplies available. Some nurses indicated that they went to stores to purchase their own makeshift PPE such as overalls, gowns, and respiratory protective equipment generally used in other industries, such as construction. Several nurses resorted to wearing a black plastic bag over their uniforms (See Figure 1).

Some nurses interviewed indicated that the hospitals were not prepared for the influx of patients suffering from COVID-19 and that the scene reminded them of the casualties one might see during wartime. But

the simile does an injustice to nurses. While the COVID-19 virus might be conceptualized as an invisible enemy, it does not have any “intentions” and cannot sign a truce. Moreover, viewing hospitals as war zones and nurses as heroes who fight the virus does not constitute a fair simile, since nurses are employees of hospitals paid to do their job, but not to risk their lives, and hospitals ought to ensure that their units are safe places where security is always a primary concern (Panzeri et al., 2021).

Chaotic and Ever-Changing Communication/Guidance: Airborne Protection

Surgical masks can help decrease droplet transmission of SARS-CoV-2, but some ultra-fine viral particles can still penetrate these masks (Stewart et al., 2020). Although the CDC recommends surgical masks if respirators are not available, this should not be an excuse for healthcare employers to avoid providing respirators to its employees. The CDC alternative guidance created confusion, not only for nurses, but also for the public, regarding the use and enforcement of masks. Employers took hold of this alternative guidance, perhaps as a way to save money and supplies, and this resulted in nurses indicating on surveys that they were not given maximum PPE by their employers (See Figure 2).

Let’s be clear: Under usual and customary circumstances, the CDC and OSHA recommend N95 respirators for patient contact and aerosol generating procedures. N95s, which must be certified by National Institute for Occupational Safety & Health (NIOSH), are a type of non-powered, disposable filtering face-piece respirator (FFR), designed for protection against respirable particulates (Stewart et al, 2020). N95s are labeled as such since they are able to filter out 95% of particulates that are greater than 0.3μm in size. Nevertheless, even in the face of a pandemic crisis, N95 masks were not provided to nurses in accordance with CDC and OSHA guidance.

PPE

Figure 1 Makeshift

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100% Gloves Impermeable Gown Face Shield/Goggles N95 Respirator PAPR Respirator 100% 70% 69% 7% 54%

to PPE

Figure 2 Access

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100% Yes No 42% 55% Are Staff currently required or will be required to reuse N95 respirators while caring for COVID

patients?

Note. Chart of survey responses for the accessibility of different types of personal protective equipment (PPE). Air-purifying respirators (PAPR) are the least accessible, and N95 respirators are the second to least accessible. Figure 3 N95 Reuse

-19

15 Journal of the New York State Nurses Association, Volume 49, Number 1

Answered 1,900 Skipped 106

n

Venting the Truth About COVID-19

Interviewee Statements Regarding N95 Reuse and Lack of Access to PPE

Nurse Interviewee Statements

“There is a lack of N95s at my facility.”

“My facility failed to ration N95s.”

“My facility did not fit test us for N95s and failed to provide us with gowns.”

“We were only given surgical masks during the height of the pandemic.”

“While caring for a ventilated, positive COVID patient with pneumonia, my manager gave me an unrecognizable N95 mask. It turned out to be a mask from a dental company. One of the straps snapped and whipped my face, exposing me to the virus.”

“Every day it seems like we are being given a different brand of N95 masks.”

“After struggling with three outbreaks since the start of the COVID pandemic, we are only just now being fitted in February 2021 for N95 masks.”

“Our hospital does not have a universal masking protocol.”

“Our hospital told us not to wear masks because it might make the patients anxious.”

“When I tried to wear a mask, my manager would question why I had one on. She would ask me if I was sick.”

“Even after my hospital was cited by OSHA for failure to provide N95 masks and failure to check mask seals, my employer continued to claim that they provided what they were supposed to for every RN.”

While many facilities have claimed that they provided adequate respiratory protection during COVID, it appears clear from the survey (Figure 3) and from interviewees (Table 3) that over 50% of nurses surveyed did not have N95 respirators and were forced to reuse their respirators, rather than having been provided the recommended N95 respirator for each patient interaction. Reusing N95 respirators can result in degraded performance, making them less effective at filtration what they are certified for (Bielcor, 2021).

Ultimately, as a result of a lawsuit filed by one nurses union against a large, public sector hospital, management was forced to borrow equipment from the Department of Health to fit test nurses and their coworkers for N95 respirators.

Inadequate Training

Work Related Injury and Illness Due to Inadequate Training: Escalating Workers Compensation. Healthcare employers owe a duty of care to their nurses. This means they must provide adequate training

Figure 4

Hierarchy of Controls

Elimination

S ubstitution Engineering Controls Administrative Controls

PPE

Note. Elimination and substitution considered the most effective of controls, whereas PPE is the least effective.

and resources to increase the safety of their employees and others involved in the day-to-day provisions of care to the public. If an employer fails to provide necessary training and safety resources, and an employee is injured as a result, the employer may be held liable for negligence. During a coronavirus pandemic, employers must provide training on physical distancing requirements; face coverings and sanitation; safe and healthy work practices and control measures; knowledge of the ability of asymptomatic individuals to transmit coronavirus; COVID-19 signs, symptoms and reporting procedures for the workplace; and quarantining/ isolating requirements. Failure to adequately train or provide safety resources can result in claims for workers’ compensation.

New York employers must carry workers’ compensation insurance to pay benefits to employees who are made ill or injured due to their employment. Nurses, who work in a healthcare environment where COVID-19 exposure risks are significantly higher than other workers, are more likely to have compensable COVID-19 workers’ compensation claims. However, underreporting of workers’ compensation cases in general has been widespread over the past decade on both the part of employees and employers.

One of the most common reasons for underreporting work comp claims is worker fear of retaliation by their employer and the potential to lose one’s job or be disciplined. Another reason for RN employee underreporting is related to perceptions of injuries as being “small” or “part of the job.” Employer underreporting compounds the issue due to corporate fear of increasing workers’ compensation costs or hurting their chances of winning contracts. The overall result is that employers now provide only a small percentage (about 21%) of the overall financial cost of workplace injuries and illnesses through workers’ compensation. Instead, the costs of workplace injuries are borne primarily by injured workers, their families, and taxpayersupported components of the social safety net (American Public Health Association, 2017).

Table 3

Journal of the New York State Nurses Association, Volume 49, Number 1 16 n Venting the Truth About COVID-19

In response to our nurse 2021 COVID-19 Survey, 70.17% of 352 nurses infected by COVID-19 while on the job did not file for workers’ compensation and 12.78% of those nurses who reported claims were told that their claims were denied. One tactic implemented by one nurses union in response to the severe underreporting of claims was to reach out to individual nurse members and to report an illness to the employer on their behalf.

Inadequate Infection Control

Hierarchy of Controls. It is essential that facilities provide appropriate PPE to healthcare workers, especially nurses. However, PPE is not enough. According to NIOSH, it is important to apply the hierarchy of hazard controls (Figure 4) in order to effectively prevent occupational exposures (CDC, 2015).

Figure 5

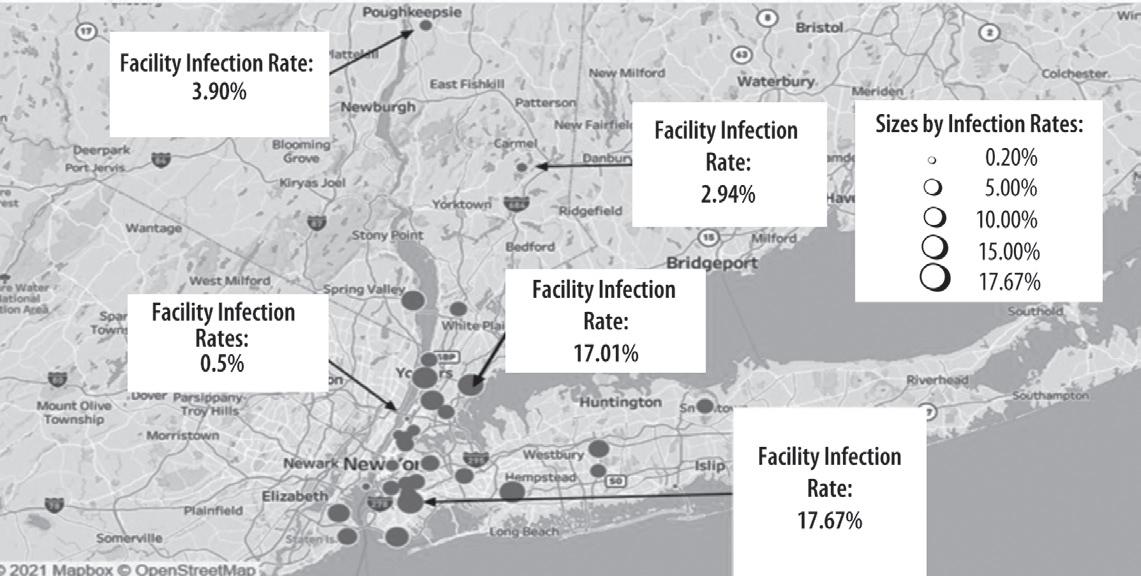

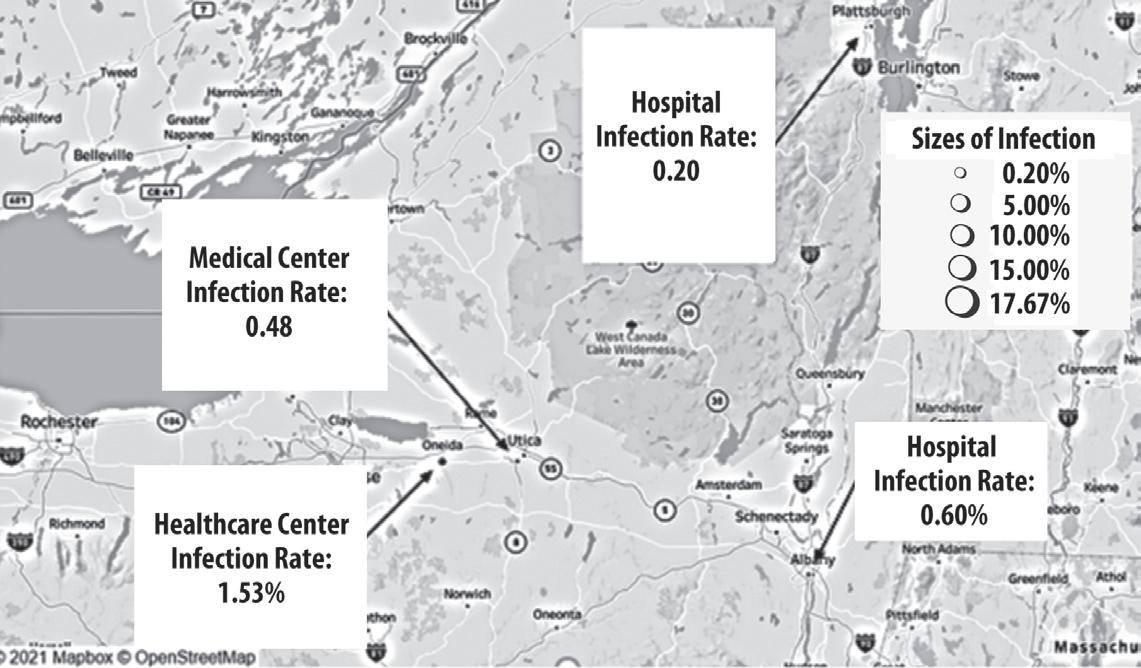

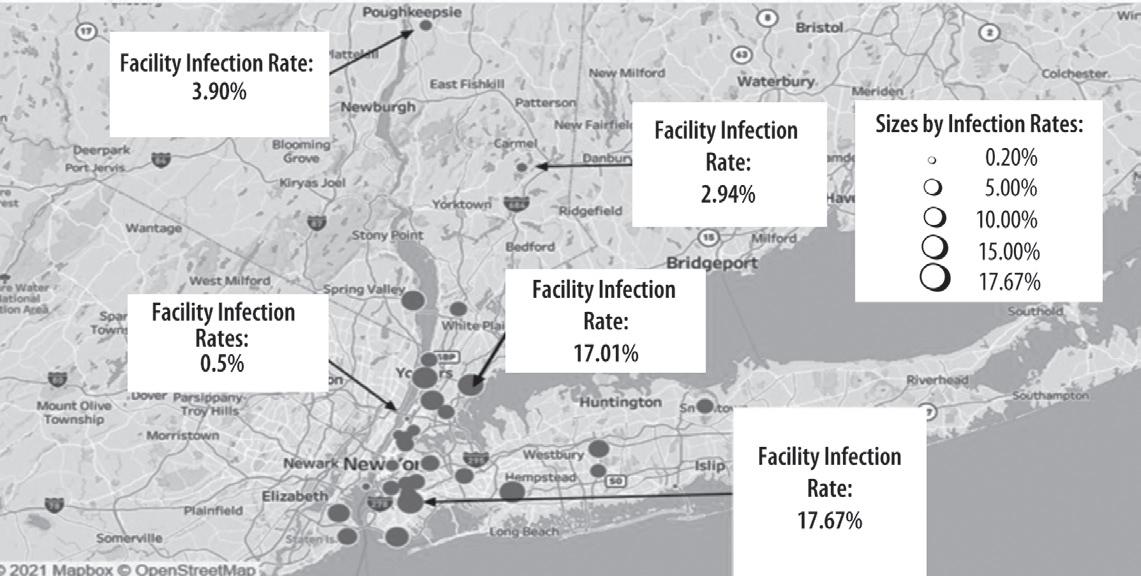

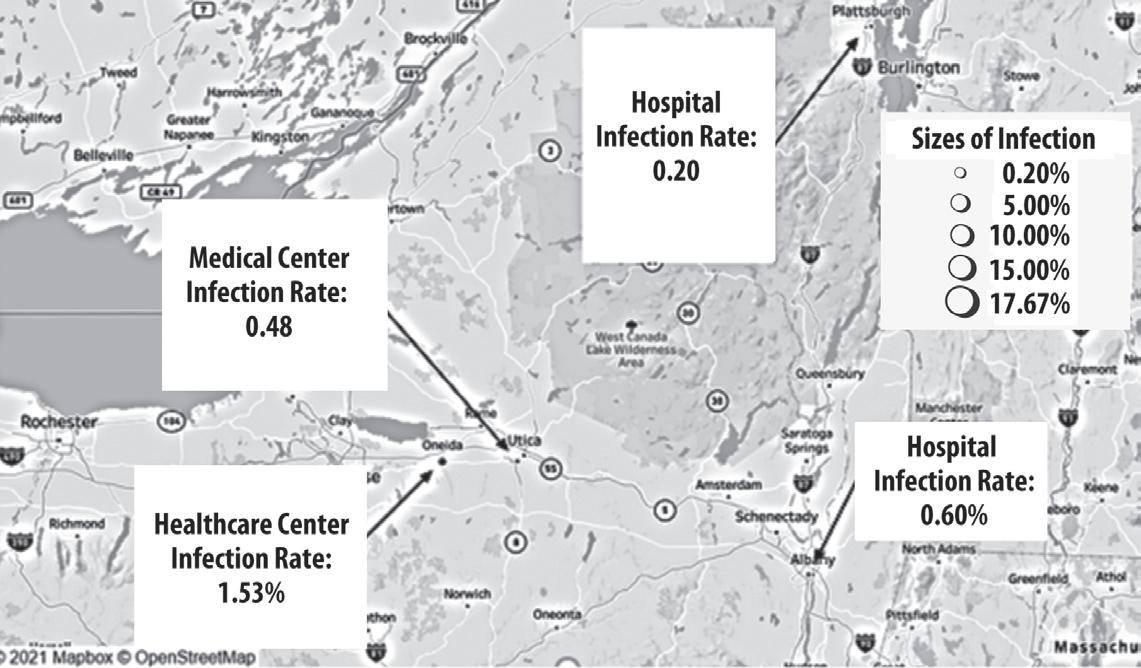

Distribution of Infection Rates of Nurses at Examined Healthcare Facilities in New York State: Top Map

Hospital Infection Rate: 0.20%

Medical Center Infection Rate: 0.48%

Healthcare Infection Rate: 1.53%

Figure 6

Sizes of Infection 0.20% 5.00% 10.00% 15.00% 17.67%

Elimination and Substitution. The Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion (Public Health Ontario) created infection prevention and control (IPAC) recommendations, starting with elimination and substitution which are considered to be the most effective in the hierarchy (Public Health Ontario, 2021). Due to the Delta variant wave, the remainder of the unvaccinated within populations, and the shortage of vaccines around the world, it will be difficult to eliminate COVID-19 entirely. However, COVID-19 vaccines are effective in preventing the disease, or at least reducing the risk of COVID-19 severity. In Figures 5 and 6 (Distribution of facilities with their associated infection rates of nurses), the facilities located in the New York State Capital Region had less infection rates than facilities in other regions of New York during the first COVID-19 wave. However, the Capital Region is currently seeing the highest rate of COVID19 cases among the general population compared to the rest of New York (New York State, 2021), likely due to the region’s lower vaccination rates. Therefore, it is important to encourage more people to get vaccinated, which can help reduce transmission and also the likelihood of infection for healthcare workers.

Engineering Control Measures. Engineering measures, such as barriers between patients and healthcare workers, can help reduce the risk of exposure. Facilities should improve ventilation by utilizing airborne infection isolation rooms (AIIR) and increasing air changes in their heating ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) systems, and improving air filtration. There should also be antechambers for changing into and out of PPE (Brosseau et al., 2021).

Hospital Infection Rate: 0.60%

Administrative Control Measures. Administrative measures include improving staffing ratios by hiring nurses or changing policies to retain current nurses. From our results, many facilities have had over two patients to one ICU nurse ratios (California’s state mandated maximum ICU ratio is 1 to 2), suggesting that there needs to be significant improvements to not only deal with the COVID-19 Delta wave, but also to prepare for the future. In addition, screening, testing, signage, and cohorting of staff and patients remain important controls (Brosseau et al., 2021), but they have been ignored by facilities. This is likely due to the incorrect assumption that, once the population is vaccinated, the pandemic will be over.

Distribution of Infection Rates of Nurses at Examined Healthcare Facilities in New York State: Bottom Map

Facility Infection Rate: 3.90%

Facility Infection Rate: 0.5%

Facility Infection Rate: 2.94%

Facility Infection Rate: 17.01%

Sizes by Infection Rates: 0.20% 5.00% 10.00% 15.00% 17.67%

Facility Infection Rate: 17.67%

Note The sizes of the points are proportional with the level of infection rates for each facility. The top of the map shows the Upstate New York region and the bottom of the map shows the Westchester/mid-Hudson Valley and Downstate regions.

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE). Although PPE should not be the only protection for healthcare workers, it is highly important that facilities maintain an adequate supply of gloves, gowns, facial and eye protection, and N95 (or higher-level) respirators. Workers should also be properly fit tested for respirators to minimize exposure. One study has described the advantages of elastomeric respirators and suggested that these are beneficial for all healthcare workers. Even half facepiece elastomeric respirators can provide respiratory protection equal to and often better than N95 respirators. Elastomerics can be safely reused multiple times and can be easily cleaned and decontaminated. Unlike N95s, elastomerics have well-established cleaning protocols. Despite being more expensive than N95s (~$20-$50), elastomeric respirators are, in the long run, less expensive than N95s (Brosseau et al., 2021). In addition, healthcare facilities should expand their use of powered airpurifying respirators (PAPRs) with hoods, as these respirators are already familiar to healthcare workers, allow the mouth to be seen by patients and staff who may be hard of hearing, and can be worn by those who cannot pass a fit test on another type of respirator (NYSNA, 2021).

17 Journal of the New York State Nurses Association, Volume 49, Number 1

About

n

Venting the Truth

COVID-19

Implementation of Interventions

Just as Nightingale experienced during the Crimean War, from PPE to staffing, nurses have struggled with various challenges throughout the pandemic. Despite their hardships, one thing remains clear: Nurses are dedicated to their work, patients, and team. They deserve the right to be treated fairly and safely and offered full protection. Nurse unions have supported their members and have helped them to raise their voices through rallies, protests, lawsuits, and more concerted actions, but more work needs to be done to win improvements for nurses.

Recommendations for Employers

Recommendation 1. Apply the hierarchy of hazard controls to improve occupational health and safety against COVID-19 for all employees in facilities.

1. Invest in engineering controls to isolate and prevent transmission of COVID-19 in workplace.

2. Enforce COVID-19 administrative controls to standardize workplace procedures.

a. Standardize and enforce procedures that comply with social distancing guidelines for triaging and cohorting patients.

b. Train nurses in evidence-based protocols for utilizing PPE, such as fit testing for N95s and donning and doffing PPE.

c. Enforce safe staffing ratios in all units.

d. Create comprehensive trainings for nursing COVID-19 patients and assess competency after trainings.

e. Limit visitation to decrease the risk of community-acquired COVID infection to enter the facility.

f. Test patients upon entry to the facility.

g. Assume patients are COVID positive until proven otherwise.

3. Invest in 90-day stockpiles of PPE, including gloves, gowns, facial and eye protection, and N95 (or higher-level) respirators.

a. Consider investment in alternative and sustainable PPE, such as elastomeric respirators and PAPRs.

b. Allow nurse representatives to view and verify 90-day stockpile.

Recommendation 2. All patient-facing staff must be provided with N95 or higher-level respirators.

1. Sufficient numbers of N95s or higher-level PPE for all staff to use as intended (single use, for each patient care session)

2. No reprocessing of N95 respirators

3. Incorporation of elastomeric respirators or elastomeric respirator programs with a sufficient supply of respirators and cartridges for key frontline staff to use during pandemic surges or other emergency situations

Recommendation 3. Create a working group of administrators, managers, and frontline nurses that meets regularly to facilitate communication and collaboration regarding unsafe working conditions and other nursing concerns. Involve nurses in decision-making meetings and processes.

Recommendation 4. Open units that were closed during the pandemic, such as psychiatric services.

Recommendation 5. Provide all employees with free, independent, and accessible mental health resources.

Recommendation 6. Prioritize the retention of experienced nurses.

1. Offer COVID-19 pay to nurses who worked throughout the pandemic.

2. Recognize achievements of experienced nurses in facilities, such as the number of years in the profession or leadership roles taken.